Indigenous-Amazonian Traditional Medicine’s Usage of the Tobacco Plant: A Transdisciplinary Ethnopsychological Mixed-Methods Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Treatment Description and Setting

2.2. Participant

2.3. Pre-Treatment Diagnostic Scales

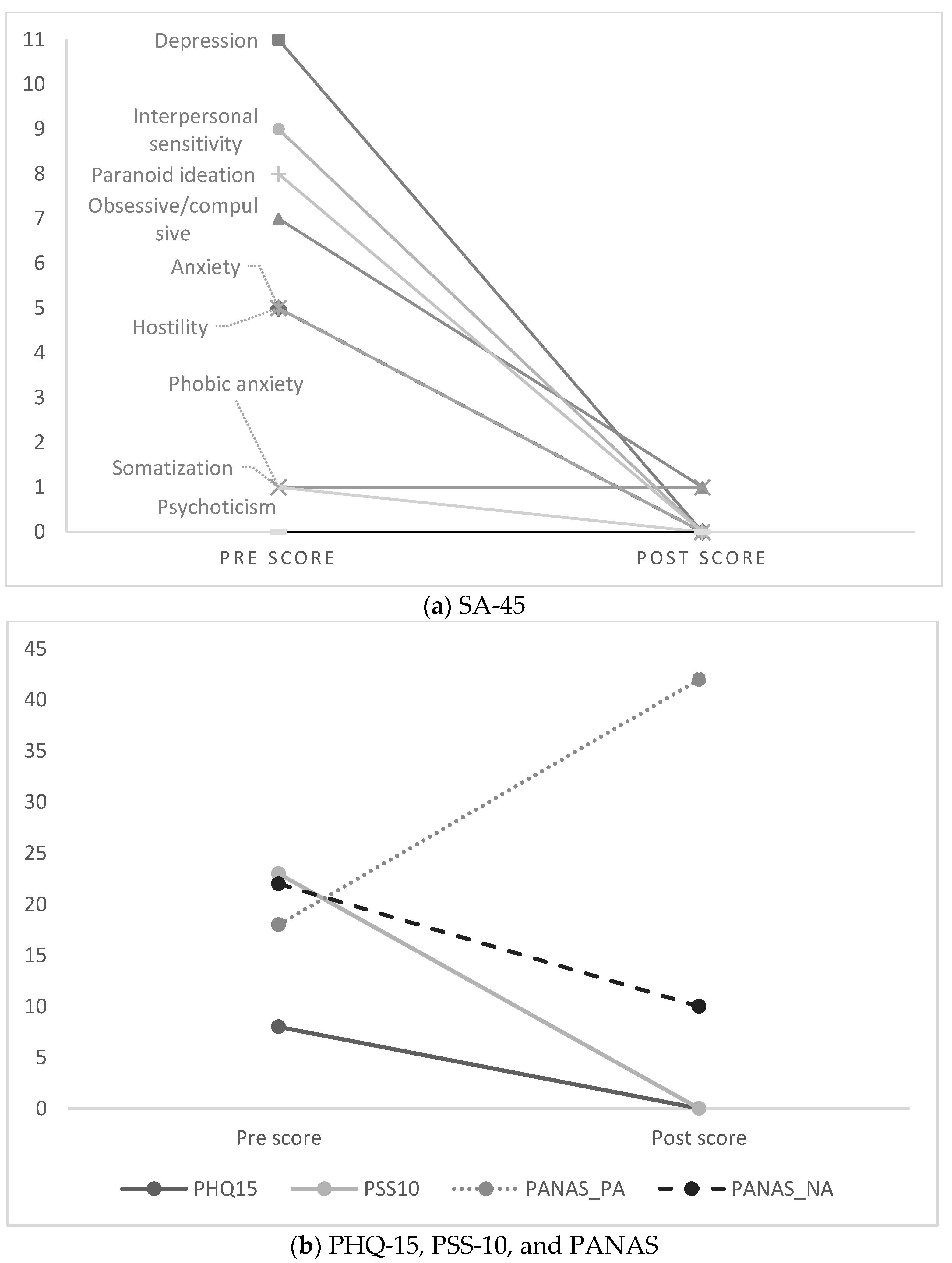

2.4. Comparison of Pre- and Post-Treatment Scores (Descriptivie)

2.5. Experience during the Treatment: Ecological Momentary Assessment

2.6. Patient Perspective at Post-Treatment

3. Discussion

4. Methods

4.1. Design and Procedure

4.2. Measures

4.3. Data Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Reitsma, M.B.; Kendrick, P.J.; Ababneh, E.; Abbafati, C.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abdoli, A.; Abedi, A.; Abhilash, E.S.; Abila, D.B.; Aboyans, V.; et al. Spatial, temporal, and demographic patterns in prevalence of smoking tobacco use and attributable disease burden in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2021, 397, 2337–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Soelch, C. Neuroadaptive changes associated with smoking: Structural and functional neural changes in nicotine dependence. Brain Sci. 2013, 3, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowing, L.R.; Ali, R.L.; Allsop, S.; Marsden, J.; Turf, E.E.; West, R.; Witton, J. Global statistics on addictive behaviours: 2014 status report. Addiction 2015, 110, 904–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2017: Monitoring Tobacco Use and Prevention Policies; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Forouzanfar, M.H.; Alexander, L.; Anderson, H.R.; Bachman, V.F.; Biryukov, S.; Brauer, M.; Burnett, R.; Casey, D.; Coates, M.M.; Cohen, A.; et al. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks in 188 countries, 1990–2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015, 386, 2287–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyuela-Caycedo, A.; Kawa, N.C. The Master Plant: Tobacco in Lowland South America; Chapter 1; Russell, A., Rahman, E., Eds.; Bloomsbury: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 27–44. [Google Scholar]

- Wilbert, J. Tobacco and Shamanism in South America; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, A.; Rahman, E. The Master Plant: Tobacco in Lowland South America; Bloomsbury: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jauregui, X.; Clavo, Z.M.; Jovel, E.M.; Pardo-de-Santayana, M. “Plantas con madre”: Plants that teach and guide in the shamanic initiation process in the East-Central Peruvian Amazon. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 134, 739–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbira-Freedman, F. Tobacco and shamanic agency in the Upper Amazon: Historical and contemporary perspectives. In The Master Plant: Tobacco in Lowland South America; Russell, A., Rahman, E., Eds.; Bloomsbury: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 63–86. [Google Scholar]

- Lagrou, E. Sorcery and Shamanism in Cashinahua Discourse and Praxis, Purus River, Brazil. In Darkness and Secrecy: The Anthropology of Assault Sorcery and Witchcraft in Amazonia; Neil, L.W., Robin, W., Eds.; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2004; pp. 244–271. [Google Scholar]

- Barbira-Freedman, F. Shamanic plants and gender in the healing forest. In Plants, Health and Healing: On the Interface of Ethnobotany and Medical Anthropology; Hsu, E., Harris, S., Eds.; Berghahn Books: Oxford, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Janiger, O.; de Rios, M.D. Suggestive Hallucinogenic Properties of Tobacco. Med. Anthropol. Newsl. 1973, 4, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepard, G.H. Psychoactive plants and ethnopsychiatric medicines of the Matsigenka. J. Psychoact. Drugs 1998, 30, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luziatelli, G.; Sørensen, M.; Theilade, I.; Mølgaard, P. Asháninka medicinal plants: A case study from the native community of Bajo Quimiriki, Junín, Peru. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2010, 6, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E.; Semo, L.; Morales, M.; Noza, Z.; Nuñez, H.; Cayuba, A.; Noza, M.; Humaday, N.; Vaya, J.; Van Damme, P. Ethnomedicinal practices and medicinal plant knowledge of the Yuracarés and Trinitarios from Indigenous Territory and National Park Isiboro-Sécure, Bolivian Amazon. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 133, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, G. The one intoxicated by tobacco: Matsigenka shamanism. In Portals of Power: Shamanism in South America; Langdon, E.J.M., Baer, G., Eds.; University of New Mexico Press: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Duke, D.; Wohlgemuth, E.; Adams, K.R.; Armstrong-Ingram, A.; Rice, S.K.; Young, D.C. Earliest evidence for human use of tobacco in the Pleistocene Americas. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 6, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, M.; Brownstein, K.J.; Pantoja Díaz, L.; Ancona Aragón, I.; Hutson, S.; Kidder, B.; Tushingham, S.; Gang, D.R. Metabolomics-based analysis of miniature flask contents identifies tobacco mixture use among the ancient Maya. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverría, J.; Niemeyer, H.M. Nicotine in the hair of mummies from San Pedro de Atacama (Northern Chile). J. Archaeol. Sci. 2013, 40, 3561–3568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nater, L. Colonial Tobacco. Key Commodity of the Spanish Empire, 1500–1800. In From Silver to Cocaine; Topik, S., Marichal, C., Frank, Z., Eds.; Latin American Commodity Chains and the Building of the World Economy, 1500–2000; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2006; pp. 93–117. [Google Scholar]

- Charlton, A. Medicinal uses of tobacco in history. J. R. Soc. Med. 2004, 97, 292–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keefe, A.M.; Pollay, R.W. Deadly targeting of women in promoting cigarettes. J. Am. Med. Women’s Assoc. 1972 1996, 51, 67–69. [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen, L. Comprehensive tobacco marketing restrictions: Promotion, packaging, price and place. Tob. Control. 2012, 21, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovato, C.; Watts, A.; Stead, L.F. Impact of tobacco advertising and promotion on increasing adolescent smoking behaviours. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011, 10, Cd003439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, A.; Wainwright, M.; Mamudu, H. A chilling example? Uruguay, Philip Morris international, and WHO’s framework convention on tobacco control. Med. Anthropol. Q. 2015, 29, 256–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, T.; Agaku, I.T.; Arrazola, R.A.; Marynak, K.L.; Neff, L.J.; Rolle, I.T.; King, B.A. Exposure to advertisements and electronic cigarette use among US middle and high school students. Pediatrics 2016, 137, e20154155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, M.V.; Mejia, R.; Kaplan, C.P.; Perez-Stable, E.J. Smoking behavior and use of tobacco industry sponsored websites among medical students and young physicians in Argentina. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014, 16, e35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Traditional Medicine Strategy 2014–2023; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- Falci, L.; Shi, Z.; Greenlee, H. Multiple chronic conditions and use of complementary and alternative medicine among US adults: Results from the 2012 National Health Interview Survey. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2016, 13, E61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molassiotis, A.; Fernadez-Ortega, P.; Pud, D.; Ozden, G.; Scott, J.A.; Panteli, V.; Margulies, A.; Browall, M.; Magri, M.; Selvekerova, S.; et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in cancer patients: A European survey. Ann. Oncol. 2005, 16, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlier, P.; Coppens, Y.; Malaurie, J.; Brun, L.; Kepanga, M.; Hoang-Opermann, V.; Correa Calfin, J.A.; Nuku, G.; Ushiga, M.; Schor, X.E.; et al. A new definition of health? An open letter of autochthonous peoples and medical anthropologists to the WHO. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2017, 37, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Global Report on Traditional and Complementary Medicine 2019; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Kohn, R.; Saxena, S.; Levav, I.; Saraceno, B. The treatment gap in mental health care. Bull. World Health Organ. 2004, 82, 858–866. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso, J.; Liu, Z.; Evans-Lacko, S.; Sadikova, E.; Sampson, N.; Chatterji, S.; Abdulmalik, J.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S.; Al-Hamzawi, A.; Andrade, L.H.; et al. Treatment gap for anxiety disorders is global: Results of the World Mental Health Surveys in 21 countries. Depress. Anxiety 2018, 35, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, R.; Ali, A.A.; Puac-Polanco, V.; Figueroa, C.; López-Soto, V.; Morgan, K.; Saldivia, S.; Vicente, B. Mental health in the Americas: An overview of the treatment gap. Rev. Panam. De Salud Publica Pan Am. J. Public Health 2018, 42, e165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, V.; Xiao, S.; Chen, H.; Hanna, F.; Jotheeswaran, A.T.; Luo, D.; Parikh, R.; Sharma, E.; Usmani, S.; Yu, Y.; et al. The magnitude of and health system responses to the mental health treatment gap in adults in India and China. Lancet 2016, 388, 3074–3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans-Lacko, S.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S.; Al-Hamzawi, A.; Alonso, J.; Benjet, C.; Bruffaerts, R.; Chiu, W.T.; Florescu, S.; de Girolamo, G.; Gureje, O.; et al. Socio-economic variations in the mental health treatment gap for people with anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders: Results from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) surveys. Psychol. Med. 2017, 48, 1560–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gureje, O.; Nortje, G.; Makanjuola, V.; Oladeji, B.; Seedat, S.; Jenkins, R. The role of global traditional and complementary systems of medicine in treating mental health problems. Lancet Psychiatry 2015, 2, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schenberg, E.E.; de Castro Comis, M.A.; Chaves, B.R.; da Silveira, D.X. Treating drug dependence with the aid of ibogaine: A retrospective study. J. Psychopharmacol. 2014, 28, 993–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, W.; Shi, J.; Liu, Y.; Ling, W.; Kosten, T.R. Traditional medicine in the treatment of drug addiction. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abus. 2009, 35, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, P.; Robson, P.; Jerzy Cubala, W.; Vasile, D.; Dugald Morrison, P.; Barron, R.; Taylor, A.; Wright, S. Cannabidiol (CBD) as an Adjunctive Therapy in Schizophrenia: A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. Am. J. Psychiatry 2018, 175, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feeney, K.; Labate, B.C.; Hudson, J.H. Bubbling with controversy: Legal challenges for ceremonial ayahuasca circles in the United States. In Plant Medicines, Healing and Psychedelic Science: Cultural Perspectives; Labate, B.C., Cavnar, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 87–111. [Google Scholar]

- Hamill, J.; Hallak, J.; Dursun, S.M.; Baker, G. Ayahuasca: Psychological and physiologic effects, pharmacology and potential uses in addiction and mental illness. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2018, 16, 108–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyzar, E.J.; Nichols, C.D.; Gainetdinov, R.R.; Nichols, D.E.; Kalueff, A.V. Psychedelic Drugs in Biomedicine. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2017, 38, 992–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nichols, D.; Johnson, M.; Nichols, C. Psychedelics as Medicines: An Emerging New Paradigm. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 101, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, A.N.; Meshkat, S.; Benitah, K.; Lipsitz, O.; Gill, H.; Lui, L.M.W.; Teopiz, K.M.; McIntyre, R.S.; Rosenblat, J.D. Registered clinical studies investigating psychedelic drugs for psychiatric disorders. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 139, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, E.; Moore, R.A.; Fogarty, A.E.; Finn, D.P.; Finnerup, N.B.; Gilron, I.; Haroutounian, S.; Krane, E.; Rice, A.S.C.; Rowbotham, M.; et al. Cannabinoids, cannabis, and cannabis-based medicine for pain management: A systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Pain Rep. 2021, 162, S45–S66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carhart-Harris, R.; Giribaldi, B.; Watts, R.; Baker-Jones, M.; Murphy-Beiner, A.; Murphy, R.; Martell, J.; Blemings, A.; Erritzoe, D.; Nutt, D.J. Trial of Psilocybin versus Escitalopram for Depression. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1402–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palhano-Fontes, F.; Barreto, D.; Onias, H.; Andrade, K.C.; Novaes, M.M.; Pessoa, J.A.; Mota-Rolim, S.A.; Osório, F.L.; Sanches, R.; dos Santos, R.G.; et al. Rapid antidepressant effects of the psychedelic ayahuasca in treatment-resistant depression: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Psychol. Med. 2018, 49, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio Fde, L.; Sanches, R.F.; Macedo, L.R.; Santos, R.G.; Maia-de-Oliveira, J.P.; Wichert-Ana, L.; Araujo, D.B.; Riba, J.; Crippa, J.A.; Hallak, J.E. Antidepressant effects of a single dose of ayahuasca in patients with recurrent depression: A preliminary report. Rev. Bras. De Psiquiatr. 2015, 37, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coe, M.A.; McKenna, D.J. The therapeutic potential of ayahuasca. In Evidence-Based Herbal and Nutritional Treatments for Anxiety in Psychiatric Disorders; Camfield, D., McIntyre, E., Sarris, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 123–137. [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos, R.G.; Osório, F.L.; Crippa, J.A.S.; Hallak, J.E.C. Antidepressive and anxiolytic effects of ayahuasca: A systematic literature review of animal and human studies. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2016, 38, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, P.C.R.; Tófoli, L.F.; Bogenschutz, M.P.; Hoy, R.; Berro, L.F.; Marinho, E.A.V.; Areco, K.N.; Winkelman, M.J. Assessment of alcohol and tobacco use disorders among religious users of ayahuasca. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, A.A.; dos Santos, R.G.; Osório, F.L.; Sanches, R.F.; Crippa, J.A.S.; Hallak, J.E.C. Effects of ayahuasca and its alkaloids on drug dependence: A systematic literature review of quantitative studies in animals and humans. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2016, 48, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jovel, E.M.; Cabanillas, J.; Towers, G.H. An ethnobotanical study of the traditional medicine of the Mestizo people of Suni Mirano, Loreto, Peru. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1996, 53, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanz-Biset, J.; Campos-de-la-Cruz, J.; Epiquien-Rivera, M.A.; Cañigueral, S. A first survey on the medicinal plants of the Chazuta valley (Peruvian Amazon). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009, 122, 333–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luna, L.E. Vegetalismo Shamanism among the Mestizo Population of the Peruvian Amazon; Almqvist & Wiksell International: Stockholm, Sweden, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Beyer, S.V. Singing to the Plants: A Guide to Mestizo Shamanism in the Upper Amazon; University of New Mexico Press: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Berlowitz, I. Traditional Amazonian Medicine Adapted to Treat Substance Use Disorder. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Fribourg, Fribourg, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, G.; Lucas, P.; Capler, N.R.; Tupper, K.W.; Martin, G. Ayahuasca-assisted therapy for addiction: Results from a preliminary observational study in Canada. Curr. Drug Abus. Rev. 2013, 6, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renelli, M.; Fletcher, J.; Tupper, K.W.; Files, N.; Loizaga-Velder, A.; Lafrance, A. An exploratory study of experiences with conventional eating disorder treatment and ceremonial ayahuasca for the healing of eating disorders. Eat. Weight. Disord. Stud. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2018, 25, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labate, B.C.; Cavnar, C. The Therapeutic Use of Ayahuasca; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, L.S.; Rossi, G.N.; Rocha, J.M.; Osório, F.L.; Bouso, J.C.; Hallak, J.E.C.; dos Santos, R.G. Effects of ayahuasca and its alkaloids on substance use disorders: An updated (2016–2020) systematic review of preclinical and human studies. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2021, 272, 541–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeifman, R.J.; Singhal, N.; Dos Santos, R.G.; Sanches, R.F.; de Lima Osório, F.; Hallak, J.E.C.; Weissman, C.R. Rapid and sustained decreases in suicidality following a single dose of ayahuasca among individuals with recurrent major depressive disorder: Results from an open-label trial. Psychopharmacology 2021, 238, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffell, S.G.D.; Netzband, N.; Tsang, W.; Davies, M.; Butler, M.; Rucker, J.J.H.; Tófoli, L.F.; Dempster, E.L.; Young, A.H.; Morgan, C.J.A. Ceremonial Ayahuasca in Amazonian Retreats—Mental Health and Epigenetic Outcomes From a Six-Month Naturalistic Study. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, D.; Cantillo, J.; Perez, I.; Carvalho, M.; Aronovich, A.; Farre, M.; Feilding, A.; Obiols, J.E.; Bouso, J.C. The Shipibo Ceremonial Use of Ayahuasca to Promote Well-Being: An Observational Study. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 623923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, G.N.; Dias, I.C.d.S.; Baker, G.; Bouso Saiz, J.C.; Dursun, S.M.; Hallak, J.E.C.; Dos Santos, R.G. Ayahuasca, a potentially rapid acting antidepressant: Focus on safety and tolerability. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2022, 21, 789–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKenna, D.J. Clinical investigations of the therapeutic potential of ayahuasca: Rationale and regulatory challenges. Pharmacol. Ther. 2004, 102, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotiou, E. Shamanic Tourism in the Peruvian Lowlands: Critical and Ethical Considerations. J. Lat. Am. Caribb. Anthropol. 2020, 25, 374–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotiou, E. The globalization of ayahuasca shamanism and the erasure of indigenous shamanism. Anthropol. Conscious. 2016, 27, 151–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlowitz, I.; Walt, H.; Ghasarian, C.; O’Shaughnessy, D.M.; Mabit, J.; Rush, B.; Martin-Soelch, C. Who Turns to Amazonian Medicine for Treatment of Substance Use Disorder? Patient Characteristics at the Takiwasi Addiction Treatment Center. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2020, 81, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berlowitz, I.; Walt, H.; Ghasarian, C.; Mendive, F.; Martin-Soelch, C. Short-Term Treatment Effects of a Substance Use Disorder Therapy Involving Traditional Amazonian Medicine. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2019, 51, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labate, B.C.; Jungaberle, H. The Internationalization of Ayahuasca; Lit Verlag: Zurich, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Labate, B.C.; Cavnar, C. The Expanding World Ayahuasca Diaspora: Appropriation, Integration and Legislation; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Berlowitz, I.; García Torres, E.G.; Walt, H.; Wolf, U.; Maake, C.; Martin-Soelch, C. “Tobacco Is the Chief Medicinal Plant in My Work”: Therapeutic Uses of Tobacco in Peruvian Amazonian Medicine Exemplified by the Work of a Maestro Tabaquero. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 594591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuel-Navarrete, D.; Buzinde, C.N.; Swanson, T. Fostering horizontal knowledge co-production with Indigenous people by leveraging researchers’ transdisciplinary intentions. Ecol. Soc. 2021, 26, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, J.H. Transdisciplinarity: A Review of Its Origins, Development, and Current Issues. J. Res. Pract. 2015, 11, R1. [Google Scholar]

- Jahn, T.; Bergmann, M.; Keil, F. Transdisciplinarity: Between mainstreaming and marginalization. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 79, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharrock, D. Smoky Boundaries, Permeable Selves: Exploring the Self in Relationship with the Amazonian Jungle Tobacco, Mapacho. Anthropol. Forum 2018, 28, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, F.; Abdullah; Ubaid, Z.; Shahzadi, I.; Ahmed, I.; Waheed, M.T.; Poczai, P.; Mirza, B. Plastid genomics of Nicotiana (Solanaceae): Insights into molecular evolution, positive selection and the origin of the maternal genome of Aztec tobacco (Nicotiana rustica). PeerJ 2020, 8, e9552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.K.; Collings, P.R.; Diaz, J.L. On the Use of Tagetes lucida and Nicotiana rustica as a Huichol Smoking Mixture: The Aztec “Yahutli” with Suggestive Hallucinogenic Effects. Econ. Bot. 1977, 31, 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Loughmiller-Cardinal, J.; Eppich, K. Breath and Smoke: Tobacco Use Among the Maya; University of New Mexico Press: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, S.D.; Halvorson, K.S.; Myers, L.; Colla, S.R. Insect visitation and pollination of a culturally significant plant, Hopi tobacco (Nicotiana rustica). iScience 2022, 25, 105613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armijos, C.; Cota, I.; González, S. Traditional medicine applied by the Saraguro yachakkuna: A preliminary approach to the use of sacred and psychoactive plant species in the southern region of Ecuador. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2014, 10, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- French, L.A. Psychoactive agents and Native American spirituality: Past and present. Contemp. Justice Rev. 2008, 11, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valadeau, C.; Castillo, J.A.; Sauvain, M.; Lores, A.F.; Bourdy, G. The rainbow hurts my skin: Medicinal concepts and plants uses among the Yanesha (Amuesha), an Amazonian Peruvian ethnic group. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 127, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlowitz, I.; O’Shaughnessy, D.M.; Heinrich, M.; Wolf, U.; Maake, C.; Martin-Soelch, C. Teacher plants—Indigenous Peruvian-Amazonian dietary practices as a method for using psychoactives. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 286, 114910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanz-Biset, J.; Cañigueral, S. Plant use in the medicinal practices known as “strict diets” in Chazuta valley (Peruvian Amazon). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 137, 271–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Biset, J.; Cañigueral, S. Plants as medicinal stressors, the case of depurative practices in Chazuta valley (Peruvian Amazonia). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 145, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotiou, E.; Gearin, A.K. Purging and the body in the therapeutic use of ayahuasca. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 239, 112532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bustos, S. The Healing Power of the Icaros: A Phenomenological Study of Ayahuasca Experiences; California Institute of Integral Studies: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Luna, L.E. The healing practices of a peruvian shaman. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1984, 11, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callicott, C. Interspecies communication in the Western Amazon: Music as a form of conversation between plants and people. Eur. J. Ecopsychology 2013, 4, 32–43. [Google Scholar]

- De Feo, V. The ritual use of Brugmansia species in traditional Andean medicine in Northern Peru. Econ. Bot. 2004, 58, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyna Pinedo, V.; Carbajal, M.F.; Carbajal, J.R. Estudio etnomedicinal de las Mesas con San Pedro. Verificación de casos de curación. Cult. Drog. 2009, 14, 79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Davison, M.L.; Bershadsky, B.; Bieber, J.; Silversmith, D.; Maruish, M.E.; Kane, R.L. Development of a Brief, Multidimensional, Self-Report Instrument for Treatment Outcomes Assessment in Psychiatric Settings: Preliminary Findings. Assessment 1997, 4, 259–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruish, M.E.; Bershadsky, B.; Goldstein, L. Reliability and Validity of the SA-45: Further Evidence from a Primary Care Setting. Assessment 1998, 5, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.; Janicki-Deverts, D. Who’s Stressed? Distributions of Psychological Stress in the United States in Probability Samples from 1983, 2006, and 2009. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 42, 1320–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W. The PHQ-15: Validity of a New Measure for Evaluating the Severity of Somatic Symptoms. Psychosom. Med. 2002, 64, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiffman, S.; Stone, A.A.; Hufford, M.R. Ecological Momentary Assessment. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 4, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trull, T.J.; Ebner-Priemer, U. Ambulatory assessment. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 9, 151–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, G.A.; Guyot, D.; Tarroux, E.; Comte, M.; Salgues, S. Feeling Oneself Requires Embodiment: Insights From the Relationship Between Own-Body Transformations, Schizotypal Personality Traits, and Spontaneous Bodily Sensations. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 578237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peill, J.M.; Trinci, K.E.; Kettner, H.; Mertens, L.J.; Roseman, L.; Timmermann, C.; Rosas, F.E.; Lyons, T.; Carhart-Harris, R.L. Validation of the Psychological Insight Scale: A new scale to assess psychological insight following a psychedelic experience. J. Psychopharmacol. 2022, 36, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luna, L.E. The concept of plants as teachers among four mestizo shamans of Iquitos, northeastern Peru. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1984, 11, 135–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shepard, G.H.; Daly, L. Sensory ecologies, plant-persons, and multinatural landscapes in Amazonia. Botany 2022, 100, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viveiros de Castro, E. Cosmological Deixis and Amerindian Perspectivism. J. R. Anthropol. Inst. 1998, 4, 469–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peluso, D.M. That which I dream is true: Dream narratives in an Amazonian community. Dreaming 2004, 14, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiger, O.; de Rios, M.D. Nicotiana an Hallucinogen? Econ. Bot. 1976, 30, 295–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotkin, M.J.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Constable, I. Psychotomimetic use of tobacco in Surinam and French Guiana. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1980, 2, 295–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlowitz, I.; Egger, K.; Cumming, P. Monoamine Oxidase Inhibition by Plant-Derived β-Carbolines; Implications for the Psychopharmacology of Tobacco and Ayahuasca. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 886408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKenna, D.J.; Towers, G.H.; Abbott, F. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors in South American hallucinogenic plants: Tryptamine and beta-carboline constituents of ayahuasca. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1984, 10, 195–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales-García, J.A.; de la Fuente Revenga, M.; Alonso-Gil, S.; Rodríguez-Franco, M.I.; Feilding, A.; Perez-Castillo, A.; Riba, J. The alkaloids of Banisteriopsis caapi, the plant source of the Amazonian hallucinogen Ayahuasca, stimulate adult neurogenesis in vitro. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riba, J.; Valle, M.; Urbano, G.; Yritia, M.; Morte, A.; Barbanoj, M.J. Human pharmacology of ayahuasca: Subjective and cardiovascular effects, monoamine metabolite excretion, and pharmacokinetics. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2003, 306, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraz, C.A.A.; de Oliveira Júnior, R.G.; Picot, L.; da Silva Almeida, J.R.G.; Nunes, X.P. Pre-clinical investigations of β-carboline alkaloids as antidepressant agents: A systematic review. Fitoterapia 2019, 137, 104196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzin, D.; Mansouri, N. Antidepressant-like effect of harmane and other β-carbolines in the mouse forced swim test. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006, 16, 324–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- dos Santos, R.G.; Hallak, J.E.C. Effects of the Natural β-Carboline Alkaloid Harmine, a Main Constituent of Ayahuasca, in Memory and in the Hippocampus: A Systematic Literature Review of Preclinical Studies. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2017, 49, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, E.D.; Conners, C.K.; Silva, D.; Hinton, S.C.; Meck, W.H.; March, J.; Rose, J.E. Transdermal nicotine effects on attention. Psychopharmacology 1998, 140, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, G.; Sofuoglu, M. Cognitive Effects of Nicotine: Recent Progress. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2018, 16, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dev, L. Plant knowledges: Indigenous approaches and interspecies listening toward decolonizing ayahuasca research. In Plant Medicines, Healing and Psychedelic Science: Cultural Perspectives; Labate, B.C., Cavnar, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 185–204. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, L.; Shepard, G., Jr. Magic darts and messenger molecules: Toward a phytoethnography of indigenous Amazonia. Anthropol. Today 2019, 35, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuijpers, P.; Reijnders, M.; Huibers, M.J.H. The role of common factors in psychotherapy outcomes. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol 2019, 15, 207–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartogsohn, I. Constructing drug effects: A history of set and setting. Drug Sci. Policy Law 2017, 3, 2050324516683325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shaughnessy, D.M.; Berlowitz, I. Amazonian Medicine and the Psychedelic Revival: Considering the “Dieta”. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 639124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinjamury, S.P.; Vinjamury, M.; Sucharitakul, S.; Ziegler, I. Panchakarma: Ayurvedic Detoxification and Allied Therapies—Is There Any Evidence? In Evidence-Based Practice in Complementary and Alternative Medicine: Perspectives, Protocols, Problems and Potential in Ayurveda; Rastogi, S., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 113–137. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, M.E. Prevention Programs:Wat Thamkrabok: A Buddhist Drug Rehabilitation Program in Thailand. Subst. Use Misuse 1997, 32, 435–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchings, A. A survey and analysis of traditional medicinal plants as used by the Zulu; Xhosa and Sotho. Bothalia 1989, 19, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandon, T.H.; Vidrine, J.I.; Litvin, E.B. Relapse and relapse prevention. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2007, 3, 257–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, R. Tobacco smoking: Health impact, prevalence, correlates and interventions. Psychol. Health 2017, 32, 1018–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger-Gonzalez, M.; Stauffacher, M.; Zinsstag, J.; Edwards, P.; Krutli, P. Transdisciplinary research on cancer-healing systems between biomedicine and the Maya of Guatemala: A tool for reciprocal reflexivity in a multi-epistemological setting. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, C.; Bhattacharyya, S. Cannabidiol as a potential treatment for psychosis. Ther. Adv. Psychopharmacol. 2019, 9, 2045125319881916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crippa, J.A.; Guimarães, F.S.; Campos, A.C.; Zuardi, A.W. Translational Investigation of the Therapeutic Potential of Cannabidiol (CBD): Toward a New Age. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, T.; Gold, J.A. A review of emerging therapeutic potential of psychedelic drugs in the treatment of psychiatric illnesses. J. Neurol. Sci. 2020, 411, 116715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiff, C.M.; Richman, E.E.; Nemeroff, C.B.; Carpenter, L.L.; Widge, A.S.; Rodriguez, C.I.; Kalin, N.H.; McDonald, W.M. Psychedelics and Psychedelic-Assisted Psychotherapy. Am. J. Psychiatry 2020, 177, 391–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas, A.S.; Luís, Â.; Barroso, M.; Gallardo, E.; Pereira, L. Psilocybin as a New Approach to Treat Depression and Anxiety in the Context of Life-Threatening Diseases—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Clinical Trials. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redvers, N.; Blondin, B.s. Traditional Indigenous medicine in North America: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulkin, C.D.L. People of Substance: An Ethnography of Morality in the Colombian Amazon; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2012; Volume 40. [Google Scholar]

- Londoño Sulkin, C.D.J.E. Paths of Speech: Symbols, Sociality and Subjectivity among the Muinane of the Colombian Amazon. Ethnologies 2003, 25, 173–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, F.M.; Schoevers, R.A.; aan het Rot, M. Experience sampling and ecological momentary assessment studies in psychopharmacology: A systematic review. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015, 25, 1853–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomko, R.L.; Gray, K.M.; Oppenheimer, S.R.; Wahlquist, A.E.; McClure, E.A. Using REDCap for ambulatory assessment: Implementation in a clinical trial for smoking cessation to augment in-person data collection. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abus. 2019, 45, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess-Hull, A.; Epstein, D.H. Ambulatory Assessment Methods to Examine Momentary State-Based Predictors of Opioid Use Behaviors. Curr. Addict. Rep. 2021, 8, 122–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heavey, C.L.; Hurlburt, R.T.; Lefforge, N.L. Descriptive Experience Sampling: A Method for Exploring Momentary Inner Experience. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2010, 7, 345–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackrill, T. Solicited diary studies of psychotherapy in qualitative research–pros and cons. Eur. J. Psychother. Couns. 2008, 10, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, N.; Davis, A.; Rafaeli, E. Diary methods: Capturing life as it is lived. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2003, 54, 579–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiele, C.; Laireiter, A.-R.; Baumann, U. Diaries in clinical psychology and psychotherapy: A selective review. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2002, 9, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trull, T.J.; Ebner-Priemer, U.W. Ambulatory assessment in psychopathology research: A review of recommended reporting guidelines and current practices. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2020, 129, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In The Social Psychology of Health The Claremont Symposium on Applied Social Psychology; Sage Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1988; pp. 31–67. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse; Beltz Verlag: Weinheim, Germany; Basel, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

| Visit 1 | Visit 2 | Visit 3 | Visit 4 | Visit 5 | Visit 6 | Visit 7: | Corte (Day 8) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The healer explains the procedure; to drink water after the remedy, to then shower; that it may feel strong at first, but later relaxed. He explains that there will be many thoughts arising, some good ones, others bad, and recommends not to engage with negative thoughts so they can simply leave. The healer serves the remedy using traditional ritual, which includes icaros * (Amazonian chants) and blowing of tobacco (soplar). The p. drinks the remedy, drinks water, and a few minutes later vomits. Thereafter the healer leaves. | Brief conversation, then he serves the p. the tobacco remedy. She drinks water and vomits relatively soon. The healer departs. | The p. describes her feelings in relation to aspects of her life, including her illness. The healer listens closely and offers a few reflections. He serves her the tobacco, waits for her to vomit, and then leaves. | Brief conversation. The healer serves the remedy and waits. The p. exhibits unease as vomiting does not ensue promptly and effects seem to intensify. The healer instructs the p. to drink water and focus on her breathing. After a while she vomits. The healer tells her to shower and thereafter rest. He leaves. | Brief conversation. The healer tells the p. that yesterday there had been good work. He serves a very small quantity (very small sip) for her to drink, and then pours some of the liquid into her hand to take via the nostrils #. The p. vomits and then the healer leaves. | The healer explains the p. that the day before when taking the tobacco via the nostrils, she had expelled a lot of phlegm, which was very good, since that phlegm had impacted her mental state. He gives her a small dose of the tobacco remedy to drink and tells her to try to keep the liquid in today without vomiting. | The healer serves the p. an inter-mediate dose, waits for her to vomit, and leaves. | The healer performs a brief prayer and ritual to close the dietary retreat. The patient is served an abundant meal and is recommended to rest thereafter. |

| Pre-Treatment | Post-Treatment | |

|---|---|---|

| SA-45 | ||

| Global Severity Index | 47 | 2 |

| - Anxiety | 5 | 0 |

| - Depression | 11 | 0 |

| - Obsessive/Compulsive | 7 | 1 |

| - Phobic Anxiety | 1 | 1 |

| - Hostility | 5 | 0 |

| - Interpersonal Sensitivity | 9 | 0 |

| - Paranoid Ideation | 8 | 0 |

| - Somatization | 1 | 0 |

| - Psychoticism | 0 | 0 |

| PHQ-15 | ||

| Overall somatic symptoms | 8 | 0 |

| - Stomach pain | 0 | 0 |

| - Back pain | 2 | 0 |

| - Pain in arms, legs, or joints (knees, hips, etc.) | 1 | 0 |

| - Menstrual cramps, problems with period | 0 | 0 |

| - Headaches | 0 | 0 |

| - Chest pain | 0 | 0 |

| - Dizziness | 1 | 0 |

| - Fainting spells | 0 | 0 |

| - Feeling heart pound or race | 1 | 0 |

| - Shortness of breath | 0 | 0 |

| - Constipation, loose bowels, or diarrhea | 0 | 0 |

| - Nausea, gas, or indigestion | 0 | 0 |

| - Feeling tired or having low energy | 2 | 0 |

| - Trouble sleeping | 1 | 0 |

| PSS-10 | ||

| Overall psychological stress | 23 | 0 |

| PANAS - Positive affect | 18 | 42 |

| - Negative affect | 22 | 10 |

| Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 5 | Day 6 | Day 7 | Corte (Day 8) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This morning got up at… | - | 6:00 | 6:00 | 5:45 | 5:30 | 7:00 | 05:45 | 06:00 | |

| Morning: Experiences of the Preceding Night | Yesterday went to bed at… | - | 20:45 | 20:30 | 20:45 | 20:30 | 20:00 | 20:00 | 21:00 |

| Fell asleep after… | - | a long time | a long time | a bit | a bit | a long time | a bit | a bit | |

| Awoke during the night at… | - | 3:30 | 3:30 | 3:30 | 2–3 | 00–3 | 00:00 | 00:00 | |

| Sleep quality (0-very bad, 6-very good) | - | 2 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 4 | |

| Dreams, Instructions, important insights, healing experiences during night | - | I can’t remember the dreams well; many animals were searching for me; a horse, a reptile. |

| I remember dreaming but can’t recall them. |

|

| Dreams with themes of self-care and putting my needs first; to take joy in providing for myself and my needs– as if I am giving myself Christmas gifts. |

| |

| Healer’s Visit | Did the visit feel supportive/help understand something? (See Table 1 for observer descriptions of the visits) | Yes, he has such a gentle, nurturing energy, I felt glad to be in his presence. It helped me understand the numerous ways in which I’m limiting myself, problematic patterns. Clear and new ways of being emerged. | Yes, his words were sparse but brought me to tears. I felt seen. I understand surrendering to my path more fully, with less tension. | Yes | Yes, he can peer into the soul. Made me reflect on the process of spiritual awakening—how to seek God instead of the self. | Yes | Yes supportive, understandings still unclear | Yes | |

| Immediate Effects after Drinking Tobacco | Unusual body sensations | - | - | Heat | Electricity surging through my whole body. Agonizing nausea, heat, dizziness. | Tingling, nausea. | Imperceptible after drinking a spoonful or so. Mild effects within 1–2 h. | Stomach churning. | |

| Vomiting | 3 bouts | 3 episodes | 2 | 2 | 1 | No | 2 | ||

| Changes in attention or thought processes | Yes. My thoughts were remarkably clear and complete. Complex progressions of insight with grounded and sustained attention. I noticed how novel this felt because I have ADHD and struggle with sustaining attention and thought, especially complex problem solving. | Yes. Attuned, alert, clear-headed. | Yes. I am so still and clear. Solutions and understandings are completely available, no uncertainty. | Yes. My mind again cleared. This time it gave me a break from all the processing. I had no thoughts to tease through, just mental openness. I spent my day creating art for the first time in many years. | No. Very small dose today, effects were gentle. | Yes. Calm quiet thinking. | Yes. Calm and direct thoughts, almost instructional, peaking around bedtime. | ||

| Changes in emotions | Yes, immediately emotional, in intense waves; relief, gratitude, grief, joy came zipping out of me. I knew the purge would relieve me of sufferings. I thought and felt the sense of ‘Finally’; I was so grounded and clear-headed. Released shame and grief that I have been repeatedly punishing myself with. | Yes. Calm, assured, certain, complete. | Yes. I have written 10 pages of deeply emotional insights. I feel whole. | Yes. I was fearful before. The medicine took it away; even the fear of dying. | - | Yes | Yes. A great flattening of intense emotions, either depressive or manic—just grounded peace. | ||

| Visual effects | Sort of. I was slipping into an in-between half dream state and felt like I was being given a story or receiving storytelling that was spiritually important, but I can’t remember what it was. | - | - | Yes. A moving set of circles with beams shooting at a cross; a snake skeleton. | - | - | - | ||

| Before Going to Sleep: Experiences from the Afternoon/Evening | Insights | About relationships, work, spirituality, shamanic healing, ways of being, connection. I had directions repeatedly and took many notes. Things to investigate further. Ideas outside of myself. | About how to love my family and receive love. How presence is the key to joy. | About my patterns—all over. Family, work, how I exist with the world, my self-limiting beliefs. | About my difficulty with surrender and trust. My fear of dying. Spent all day reflecting on trusting the medicine and having patience as it works on me. | A focus on my control tendencies, impatience, as if the medicine worked differently by taking a day off. | That my highest and greatest good is only available if I heal my spirit and mind first. | About what to do in my life to course-correct, like an actual laundry list. So straightforward and clear, and in order of priority. | |

| Healing experience | Many things feel spontaneously clear…maybe resolved. | My nervous system and mind feel perfectly still. The healing felt very grounded and physical. | Full body presence, peace, calm. | My patience and self-compassion are growing. | I do believe healing was happening, but without feeling the tobacco much, it was a different type. | I am stronger daily; I do not feel sick. | I acknowledged my tendency to run, to seek novelty, to fluctuate across highs and lows, to overexert control. Honestly the first time I have had real insight about this. | ||

| Experience of being taught something | I journaled 3 intense pages of instructions to and for myself. I learned some gospel. | Action through nonaction is the path to my highest good. | Innumerable—one after another. Clearly realized how I am mirror with others—what frustrates me with them are my unhealed spots. | I was taught about my eagerness to please and be validated by others. Noticing so many subtleties of my behavior. | - | I felt a deep “settling in”, a fuller awe. | What developed over the day became a clear personal philosophy, I wrote it down like my life’s work, connecting dots. It seemed like I was getting the building blocks for my business (future) or eventual book chapters. | ||

| Spiritual/energy-related/transcendence experiences | I am too unfamiliar with this medicine to try to explain yet. Energetic but not completely ethereal like ayahuasca. Grounded energy. | I see the last six months crystal clear—the things that caused me great distress are perfectly ordained. |

| 100,000 volts of electricity; like an energetic near-death experience. | - | Not rocket-ship spiritual…but a continued awakening. | Insight coming one after another, after dark, I could hardly put my pen down. | ||

| Changes in Physiological Functions Today | Appetite | Diminished, bites of food only | Diminished | Even less | Normal | Normal | Diminished | Normal | |

| Body temperature | Adequately warm | Adequately warm | Adequately warm | Adequately warm | Adequately warm | Adequately warm | Adequately warm | ||

| Breathing | Normal | Slower and calmer | Normal | Normal, only for 5 min after the medicine rapid | Normal | Normal | Normal | ||

| Micturition | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | ||

| Digestion | Diarrhea, felt like part of the purging | Diarrhea | Slight diarrhea | Normal | Diarrhea | Normal | Normal |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Berlowitz, I.; García Torres, E.; Maake, C.; Wolf, U.; Martin-Soelch, C. Indigenous-Amazonian Traditional Medicine’s Usage of the Tobacco Plant: A Transdisciplinary Ethnopsychological Mixed-Methods Case Study. Plants 2023, 12, 346. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12020346

Berlowitz I, García Torres E, Maake C, Wolf U, Martin-Soelch C. Indigenous-Amazonian Traditional Medicine’s Usage of the Tobacco Plant: A Transdisciplinary Ethnopsychological Mixed-Methods Case Study. Plants. 2023; 12(2):346. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12020346

Chicago/Turabian StyleBerlowitz, Ilana, Ernesto García Torres, Caroline Maake, Ursula Wolf, and Chantal Martin-Soelch. 2023. "Indigenous-Amazonian Traditional Medicine’s Usage of the Tobacco Plant: A Transdisciplinary Ethnopsychological Mixed-Methods Case Study" Plants 12, no. 2: 346. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12020346

APA StyleBerlowitz, I., García Torres, E., Maake, C., Wolf, U., & Martin-Soelch, C. (2023). Indigenous-Amazonian Traditional Medicine’s Usage of the Tobacco Plant: A Transdisciplinary Ethnopsychological Mixed-Methods Case Study. Plants, 12(2), 346. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12020346