Mitigation of Gastric Damage Using Cinnamomum cassia Extract: Network Pharmacological Analysis of Active Compounds and Protection Effects in Rats

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

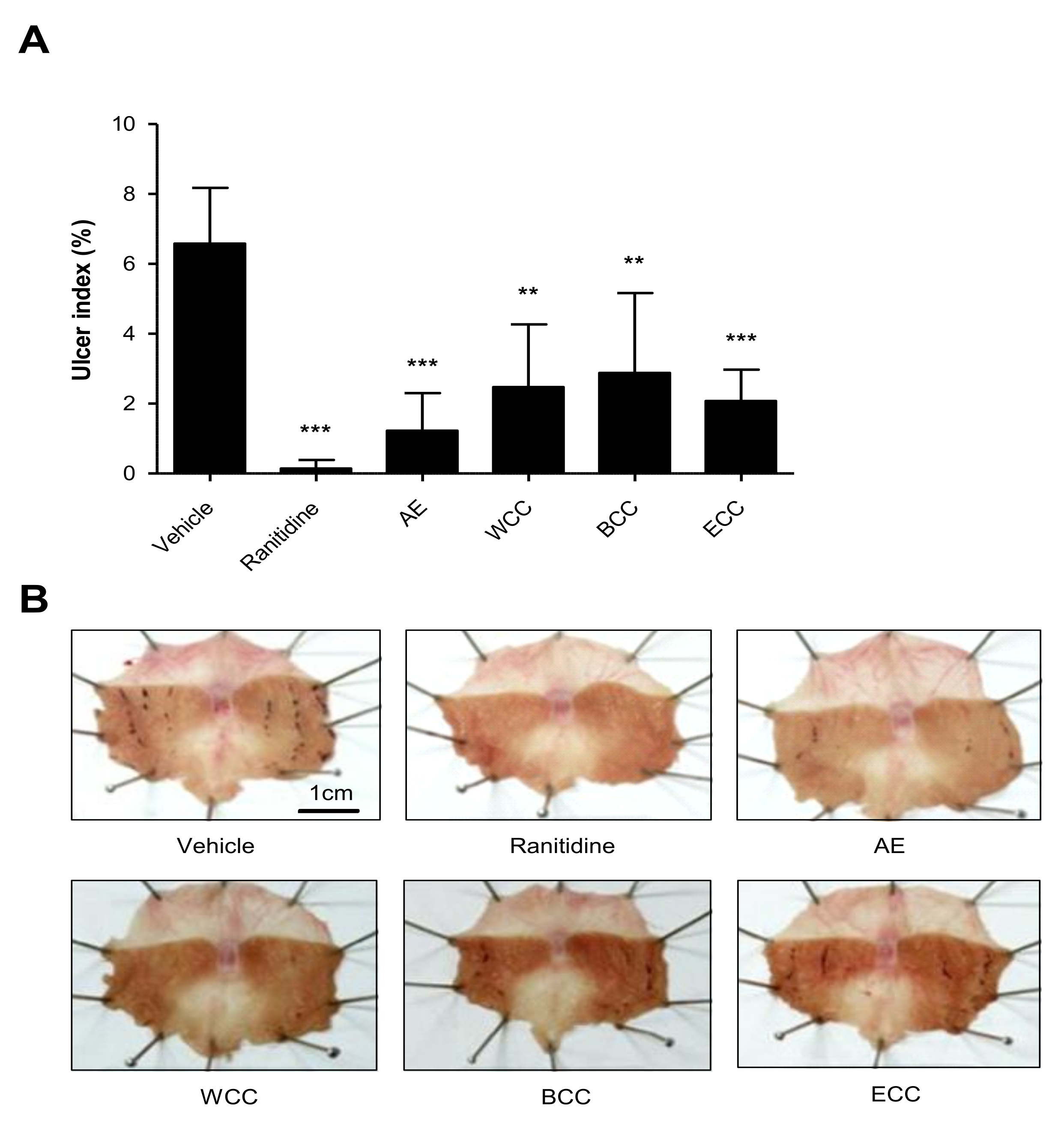

2.1. Effect of C. cassia Extracts on Indomethacin Induced Gastric Ulcers

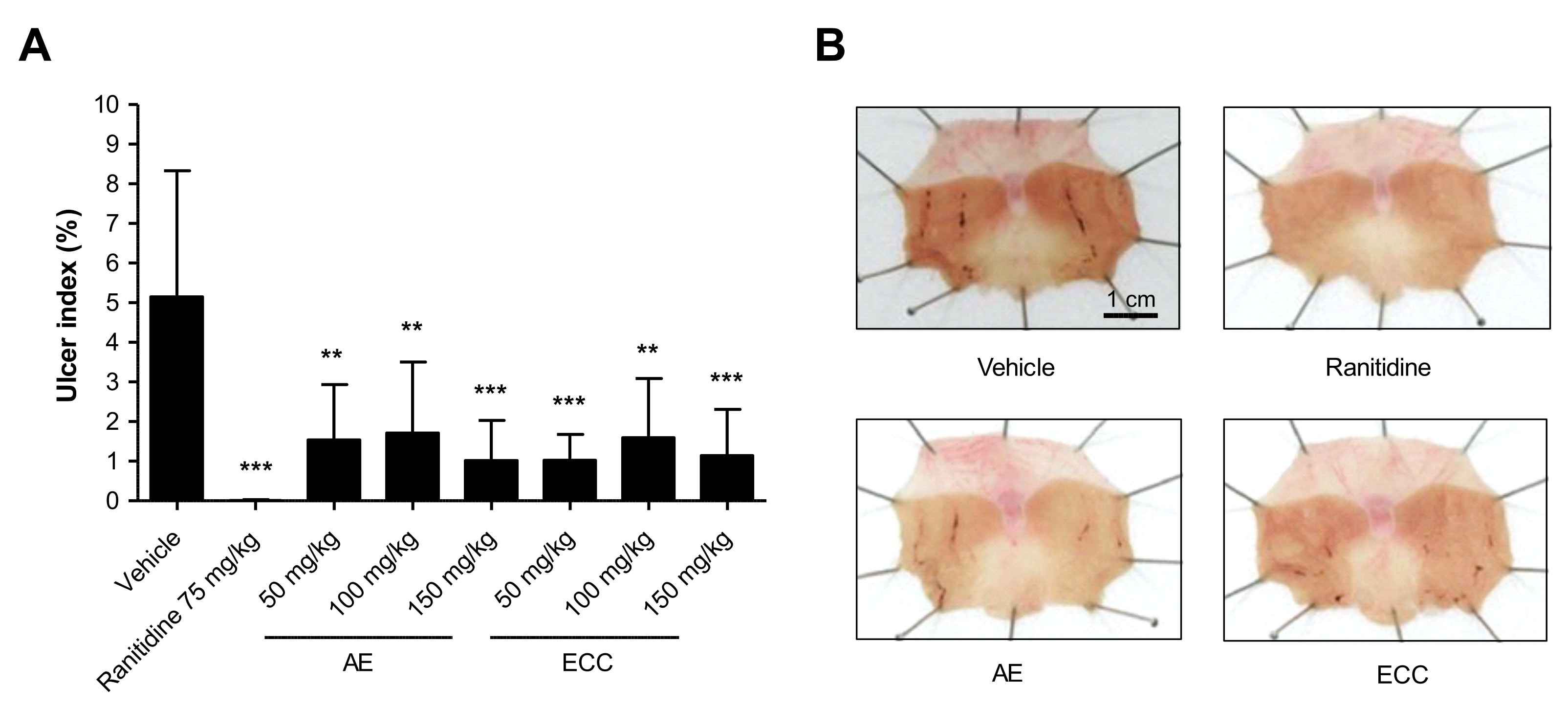

2.2. Effect of C. cassia Extracts on Gastric Mucosa Injury Using EtOH

2.3. Effect of C. cassia Extracts on HCl-EtOH-Induced Changes in Volume, pH, and Total Acidity

2.4. Network Pharmacology Analysis

2.4.1. Drug-Likeness (DL) and Oral Bioavailability (OB) Screening of Chemical Components

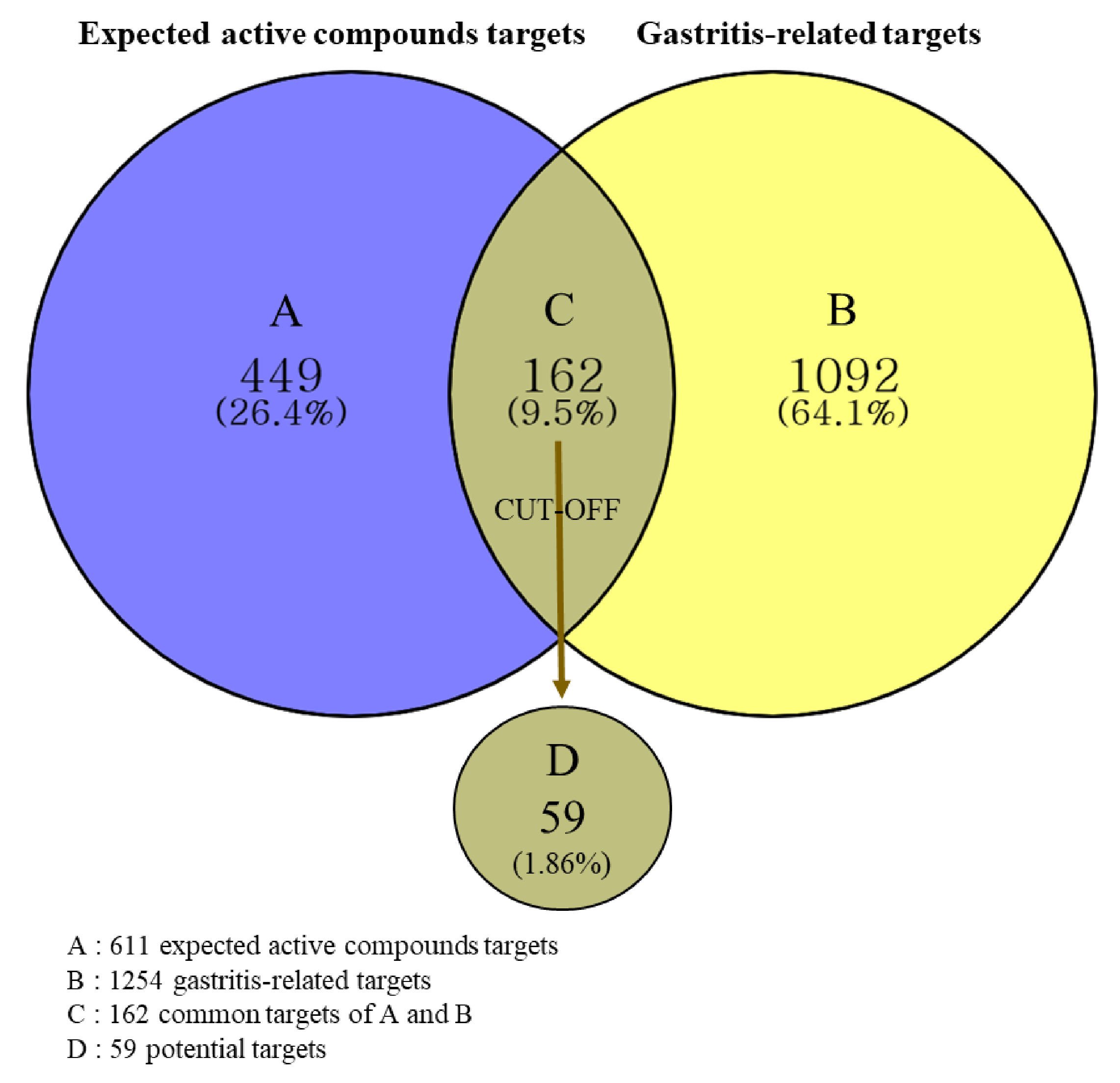

2.4.2. Prediction of Targets and Identification of Potential Targets

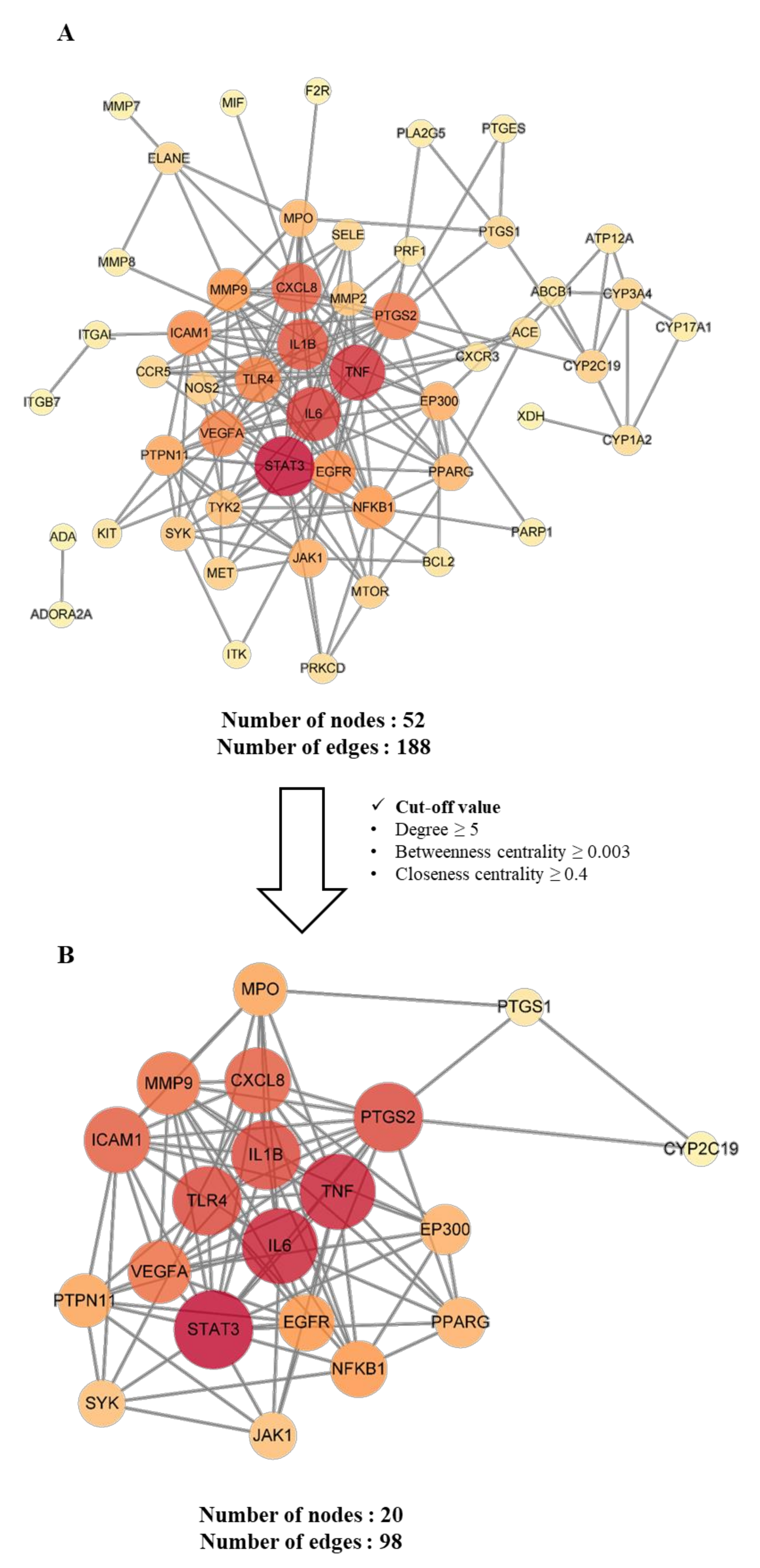

2.4.3. Construction and Analysis of Protein–Protein Interaction (PPI) Networks of Potential and Key Targets

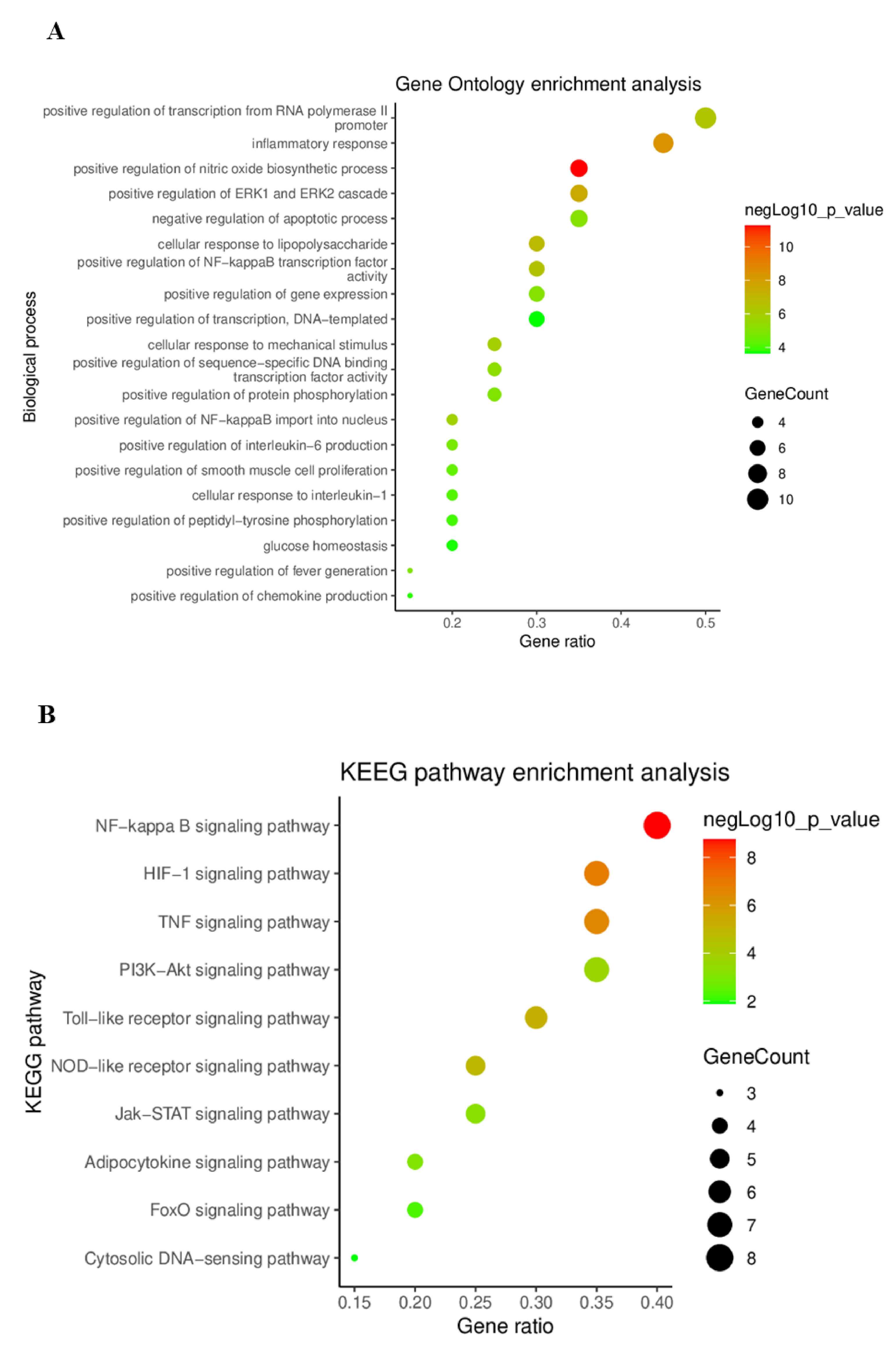

2.4.4. Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia Genes and Genomes (KEGG) Pathway Enrichment Analysis

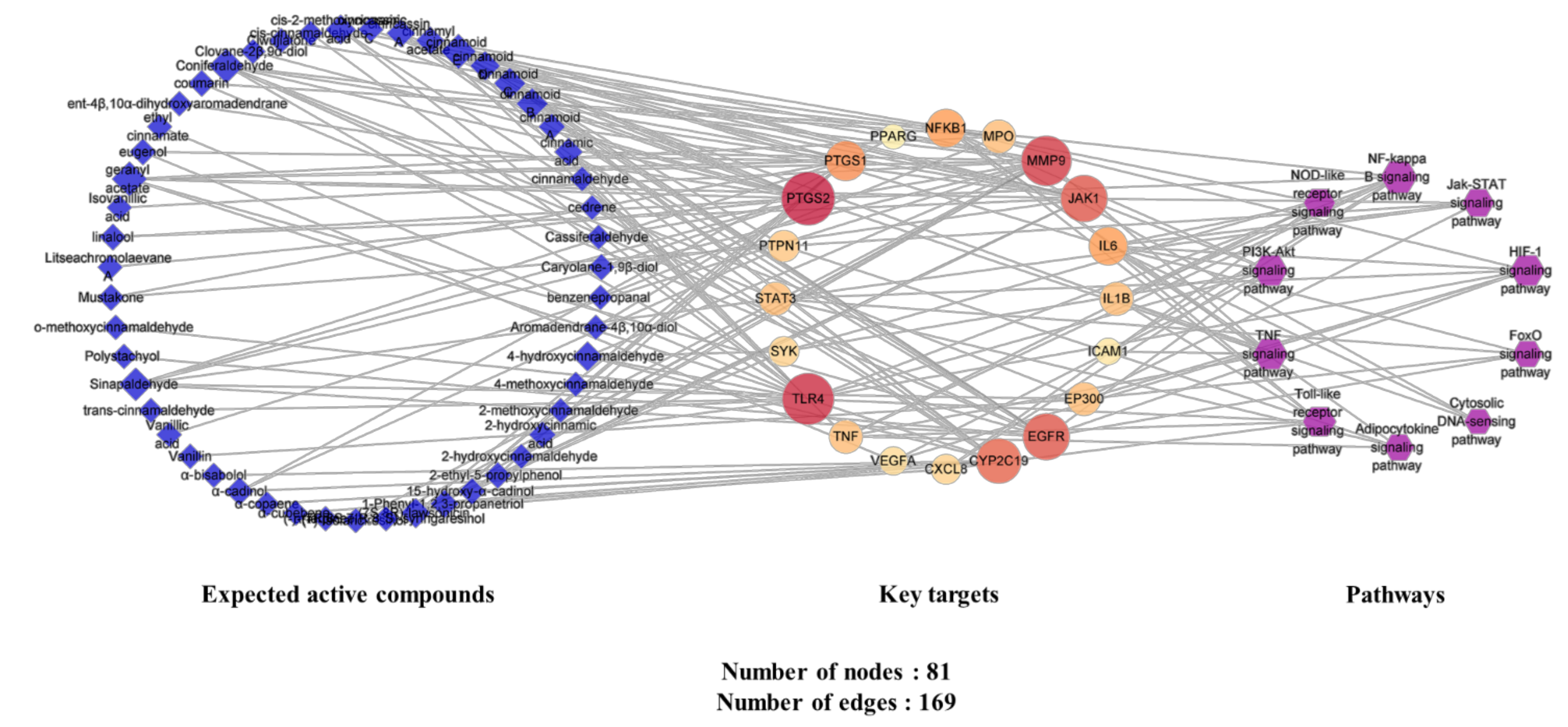

2.4.5. Analysis of Expected Active Compounds–Key Targets–Pathway (C-T-P) Network

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material and Chemicals

4.2. Experimental Animals and Their Management

4.2.1. Animal Experiment Design

4.2.2. Determination of Stomach Injury

4.2.3. Evaluation of Gastric Acid Secretion Inhibition

4.3. Network Pharmacology Analysis

4.3.1. Collecting and Screening of Chemical Components of C. cassia

4.3.2. Acquisition of Expected Active Compounds Targets and Disease Related Targets

4.3.3. Acquisition of Potential Targets

4.3.4. Construction and Analysis of the Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Network

4.3.5. Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) Pathway Enrichment Analysis

4.3.6. Construction and Analysis of Expected Active Compounds-Key Targets-Pathways (C-T-P) Network

4.4. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Graham, D.; Agrawal, N.; Roth, S. Prevention of NSAID-induced gastric ulcer with misoprostol: Multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 1988, 332, 1277–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satyanarayana, M. Capsaicin and gastric ulcers. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2006, 46, 275–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veldhuyzen van Zanten, S.; Sherman, P. Helicobacter pylori infection as a cause of gastritis, duodenal ulcer, gastric cancer and nonulcer dyspepsia: A systematic overview. CMAJ 1994, 150, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schubert, T.T.; Schubert, A.B.; Ma, C.K. Symptoms, gastritis, and Helicobacter pylori in patients referred for endoscopy. Gastrointest. Endosc. 1992, 38, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McColl, K.; El-Omar, E.; Gillen, D. Interactions between H. pylori infection, gastric acid secretion and anti-secretory therapy. Br. Med. Bull. 1998, 54, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Takeuchi, K.; Kajimura, M.; Kodaira, M.; Lin, S.; Hanai, H.; Kaneko, E. Up-regulation of H2 receptor and adenylate cyclase in rabbit parietal cells during prolonged treatment with H2-receptor antagonists. Dig. Dis. Sci. 1999, 44, 1703–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, R.J.; Girardi, L.S.; Turney, E.A. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori eradication and reduced duodenal and gastric ulcer recurrence: A review. Gastroenterology 1996, 110, 1244–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleyman, H.; Cadirci, E.; Albayrak, A.; Polat, B.; Halici, Z.; Koc, F.; Hacimuftuoglu, A.; Bayir, Y. Comparative study on the gastroprotective potential of some antidepressants in indomethacin-induced ulcer in rats. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2009, 180, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.; Lee, J.; Kim, M.; Shin, M.-R.; Shin, S.; Seo, B.; Kwon, O.; Roh, S.-S. Protective effects of a Lycium chinense ethanol extract through anti-oxidative stress on acute gastric lesion mice. Kor. J. Herbol. 2015, 30, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullarton, G.; McLauchlan, G.; Macdonald, A.; Crean, G.; McColl, K. Rebound nocturnal hypersecretion after four weeks treatment with an H2 receptor antagonist. Gut 1989, 30, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, S.W.; Oh, T.Y.; Kim, Y.S.; Sim, H.; Park, S.J.; Jang, E.J.; Park, J.S.; Baik, H.W.; Hahm, K.B. Artemisia asiatica extracts protect against ethanol-induced injury in gastric mucosa of rats. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2008, 23, 976–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.-J.; Kim, S.Y.; Han, J.; Lim, Y.-I.; Park, K.-Y. Inhibitory effects of cabbage juice and cabbage-mixed juice on the growth of AGS human gastric cancer cells and on HCl-ethanol induced gastritis in rats. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2013, 42, 682–689. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Fan, L.; Fan, S.; Wang, J.; Luo, T.; Tang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Yu, L. Cinnamomum cassia Presl: A review of its traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacology and toxicology. Molecules 2019, 24, 3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, J.H.; Park, D.H.; Lee, S.; Seo, H.J.; Park, S.J.; Jung, K.; Kim, S.-Y.; Kang, K.S. Potential and beneficial effects of Cinnamomum cassia on gastritis and safety: Literature review and analysis of standard extract. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2021, 64, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tankam, J.M.; Sawada, Y.; Ito, M. Regular ingestion of cinnamomi cortex pulveratus offers gastroprotective activity in mice. J. Nat. Med. 2013, 67, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zaidi, S.F.; Muhammad, J.S.; Shahryar, S.; Usmanghani, K.; Gilani, A.-H.; Jafri, W.; Sugiyama, T. Anti-inflammatory and cytoprotective effects of selected Pakistani medicinal plants in Helicobacter pylori-infected gastric epithelial cells. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 141, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Zheng, Y.; Wen, F.; Huang, W.; Chen, X.; Ruan, S.; Gu, S.; Hu, Y.; Teng, Y.; Shu, P. Study of the active ingredients and mechanism of Sparganii rhizoma in gastric cancer based on HPLC-Q-TOF–MS/MS and network pharmacology. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, A.; Wang, W.; Xia, Y.; Niu, X. A network pharmacology approach to explore the mechanisms of artemisiae scopariae herba for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2021, 2021, e6614039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golbeck, J. Introduction to Social Media Investigation: A Hands-On Approach; Syngress: Rockland, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, D.; Shneiderman, B.; Smith, M.A. Analyzing Social Media Networks with NodeXL, 2nd edition: Insights from a Connected World; Morgan Kaufmann: Burlington, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Metcalf, L.; Casey, W. Cybersecurity and Applied Mathematics; Syngress: Rockland, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rincon, M. Interleukin-6: From an inflammatory marker to a target for inflammatory diseases. Trends Immunol. 2012, 33, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Cooper, D.K.; Wang, H.; Chen, P.; He, C.; Cai, Z.; Mou, L.; Luan, S.; Gao, H. Potential pathological role of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-17) in xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation 2019, 26, e12502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, K.; Torres, R. Role of interleukin-1β during pain and inflammation. Brain Res. Rev. 2009, 60, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ha, H.; Debnath, B.; Neamati, N. Role of the CXCL8-CXCR1/2 axis in cancer and inflammatory diseases. Theranostics 2017, 7, 1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.; Pereira, J.; Delabio, R.; Smith, M.; Payão, S.; Carneiro, L.; Barbosa, M.; Rasmussen, L. Increased expression of interleukin-6 gene in gastritis and gastric cancer. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2021, 54, e10687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.-Y.; Wen, L.-S.; Geng, Y.-H.; Huang, J.-B.; Liu, J.-F.; Shen, D.-Y.; Meng, J.-R. Association between IL-1B gene polymorphisms and Helicobacter pylori infection: A meta-analysis. Microb. Pathog. 2019, 137, 103769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusters, J.G.; Van Vliet, A.H.; Kuipers, E.J. Pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2006, 19, 449–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, S.A.; Oh, J.; Choi, S.R.; Lee, C.H.; Lee, B.-H.; Lee, M.-N.; Hossain, M.A.; Kim, J.-H.; Lee, S.; Cho, J.Y. Anti-Gastritis and Anti-Lung Injury Effects of Pine Tree Ethanol Extract Targeting Both NF-kB and AP-1 Pathways. Molecules 2021, 26, 6275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raish, M.; Ahmad, A.; Ansari, M.A.; Alkharfy, K.M.; Aljenoobi, F.I.; Jan, B.L.; Al-Mohizea, A.M.; Khan, A.; Ali, N. Momordica charantia polysaccharides ameliorate oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis in ethanol-induced gastritis in mucosa through NF-kB signaling pathway inhibition. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 111, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossen, M.J.; Chou, J.-Y.; Li, S.-M.; Fu, X.-Q.; Yin, C.; Guo, H.; Amin, A.; Chou, G.-X.; Yu, Z.-L. An ethanol extract of the rhizome of Atractylodes chinensis exerts anti-gastritis activities and inhibits Akt/NF-κB signaling. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 228, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Lee, S.; Yang, W.S.; Jang, H.-J.; Lee, Y.J.; Kim, T.W.; Kim, S.Y.; Lee, J.; Cho, J.Y. The ability of an ethanol extract of Cinnamomum cassia to inhibit Src and spleen tyrosine kinase activity contributes to its anti-inflammatory action. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 139, 566–573. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, H.; Jeon, H.; Ock, J.; Hong, S.H.; Han, Y.-M.; Kwon, B.-M.; Lee, W.-H.; Lee, M.-S.; Suk, K. 2′-Hydroxycinnamaldehyde targets low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1 to inhibit lipopolysaccharide-induced microglial activation. J. Neuroimmunol. 2011, 230, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Yang, P.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Dong, X.; Wu, Z.; Xu, Y.; Chen, Y. trans-Cinnamaldehyde inhibits microglial activation and improves neuronal survival against neuroinflammation in BV2 microglial cells with lipopolysaccharide stimulation. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2017, 2017, 4730878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Chang, K.M.; Kim, G.H. Composition and anti-inflammatory activities of Zanthoxylum schinifolium essential oil: Suppression of inducible nitric oxide synthase, cyclooxygenase-2, cytokines and cellular adhesion. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2009, 89, 1762–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.M.; Heo, D.R.; Kim, Y.-A.; Lee, J.; Kim, N.S.; Bang, O.-S. Coniferaldehyde inhibits LPS-induced apoptosis through the PKC α/β II/Nrf-2/HO-1 dependent pathway in RAW264. 7 macrophage cells. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2016, 48, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baek, S.-H.; Park, T.; Kang, M.-G.; Park, D. Anti-inflammatory activity and ROS regulation effect of sinapaldehyde in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages. Molecules 2020, 25, 4089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Shao, J.; Zhao, C.; Shen, J.; Dong, Z.; Liu, W.; Zhao, M.; Fan, J. Chemical constituents from Viburnum fordiae Hance and their anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2018, 41, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, D.; Pontes, C.; Guinó, E.; Navarro, M.; Osorio, A.; Canzian, F.; Moreno, V. Polymorphisms in prostaglandin synthase 2/cyclooxygenase 2 (PTGS2/COX2) and risk of colorectal cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2004, 91, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Molteni, M.; Gemma, S.; Rossetti, C. The role of toll-like receptor 4 in infectious and noninfectious inflammation. Mediators Inflamm. 2016, 2016, e6978936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, L.; Jiang, C.; Pan, K.; Deng, J.; Wan, C. MMP9 protects against LPS-induced inflammation in osteoblasts. Innate Immun. 2020, 26, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rompaey, L.; Galien, R.; van der Aar, E.M.; Clement-Lacroix, P.; Nelles, L.; Smets, B.; Lepescheux, L.; Christophe, T.; Conrath, K.; Vandeghinste, N. Preclinical characterization of GLPG0634, a selective inhibitor of JAK1, for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. J. Immunol. 2013, 191, 3568–3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Huang, Z.; Huang, W.; Chen, X.; Shan, P.; Zhong, P.; Khan, Z.; Wang, J.; Fang, Q.; Liang, G. Inhibition of epidermal growth factor receptor attenuates atherosclerosis via decreasing inflammation and oxidative stress. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- El Rouby, N.; Lima, J.J.; Johnson, J.A. Proton pump inhibitors: From CYP2C19 pharmacogenetics to precision medicine. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2018, 14, 447–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannoodee, S.; Nasuruddin, D.N. Acute Inflammatory Response; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Li, J.; Meng, Y.; Cao, M.; Wang, J. Treatment effects of jinlingzi powder and its extractive components on gastric ulcer induced by acetic acid in rats. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2019, 2019, 7365841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Green, G.A. Understanding NSAIDs: From aspirin to COX-2. Clin. Cornerstone 2001, 3, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, J.L. Prostaglandins, NSAIDs, and gastric mucosal protection: Why doesn’t the stomach digest itself? Physiol. Rev. 2008, 88, 1547–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risser, A.; Donovan, D.; Heintzman, J.; Page, T. NSAID prescribing precautions. Am. Fam. Phys. 2009, 80, 1371–1378. [Google Scholar]

- Odabasoglu, F.; Cakir, A.; Suleyman, H.; Aslan, A.; Bayir, Y.; Halici, M.; Kazaz, C. Gastroprotective and antioxidant effects of usnic acid on indomethacin-induced gastric ulcer in rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2006, 103, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swarnakar, S.; Ganguly, K.; Kundu, P.; Banerjee, A.; Maity, P.; Sharma, A.V. Curcumin regulates expression and activity of matrix metalloproteinases 9 and 2 during prevention and healing of indomethacin-induced gastric ulcer. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 9409–9415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- AbdelAziz, E.Y.; Tadros, M.G.; Menze, E.T. The effect of metformin on indomethacin-induced gastric ulcer: Involvement of nitric oxide/Rho kinase pathway. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 892, 173812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlRashdi, A.S.; Salama, S.M.; Alkiyumi, S.S.; Abdulla, M.A.; Hadi, A.H.A.; Abdelwahab, S.I.; Taha, M.M.; Hussiani, J.; Asykin, N. Mechanisms of gastroprotective effects of ethanolic leaf extract of Jasminum sambac against HCl/ethanol-induced gastric mucosal injury in rats. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2012, 2012, 786426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, Y.-S.; Lee, J.H.; Song, J.; Kim, H. Gastroprotective Effects of Inulae Flos on HCl/Ethanol-Induced Gastric Ulcers in Rats. Molecules 2020, 25, 5623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jainu, M.; Devi, C.S.S. Antiulcerogenic and ulcer healing effects of Solanum nigrum (L.) on experimental ulcer models: Possible mechanism for the inhibition of acid formation. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2006, 104, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, Y.; Fujii, Y.; Homma, M. Gastric acid stimulating action of cysteamine in the rat. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1976, 36, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandan, R.; Rekha, R.D.; Saravanan, N.; Devaki, T. Protective effects of Picrorrhiza kurroa against HCl/ethanol-induced ulceration in rats. Fitoterapia 1999, 70, 498–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.H.; Hur, S.K.; Oh, O.-J.; Kim, S.S.; Nam, K.A.; Lee, S.K. Evaluation of natural products on inhibition of inducible cyclooxygenase (COX-2) and nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in cultured mouse macrophage cells. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2002, 83, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schink, A.; Naumoska, K.; Kitanovski, Z.; Kampf, C.J.; Fröhlich-Nowoisky, J.; Thines, E.; Pöschl, U.; Schuppan, D.; Lucas, K. Anti-inflammatory effects of cinnamon extract and identification of active compounds influencing the TLR2 and TLR4 signaling pathways. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 5950–5964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- He, S.; Jiang, Y.; Tu, P.-F. Three new compounds from Cinnamomum cassia. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2016, 18, 134–140. [Google Scholar]

- Sipponen, P.; Maaroos, H.-I. Chronic gastritis. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 50, 657–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Katz, P.O. Lessons learned from intragastric pH monitoring. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2001, 33, 107–113. [Google Scholar]

- Ozeki, T.; Mizuno, S.; Ohuchi, H.; Iwaki, K.; Watanabe, S.; Ueda, H.; Kawahara, H.; Masuda, H.; Sanefugi, H. The effects of prostaglandin E1 on the pepsin activities in gastric mucosa and juice. Br. J. Exp. Pathol. 1987, 68, 521. [Google Scholar]

- Guldvog, I.; Berstad, A. Opposite Effects of H2-Receptors on Parietal Cells and Chief Cells. Eur. Surg. Res. 1984, 16, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, H.I.; Dodds, W.J.; Gee, S.; Montgomery, C.; Zboralske, F.F. Role of acid and pepsin in acute experimental esophagitis. Gastroenterology 1969, 56, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMeester, T.R.; Wernly, J.A.; Bryant, G.H.; Little, A.G.; Skinner, D.B. Clinical and in vitro analysis of determinants of gastroesophageal competence: A study of the principles of antireflux surgery. Am. J. Surg. 1979, 137, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, R.H. Importance of pH control in the management of GERD. Arch. Intern. Med. 1999, 159, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissADME: A free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bickerton, G.R.; Paolini, G.V.; Besnard, J.; Muresan, S.; Hopkins, A.L. Quantifying the chemical beauty of drugs. Nat. Chem. 2012, 4, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gfeller, D.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. Shaping the interaction landscape of bioactive molecules. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 3073–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelzer, G.; Rosen, N.; Plaschkes, I.; Zimmerman, S.; Twik, M.; Fishilevich, S.; Stein, T.I.; Nudel, R.; Lieder, I.; Mazor, Y. The GeneCards suite: From gene data mining to disease genome sequence analyses. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2016, 54, 1.30.31–1.30.33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveros, J.; Venny. An interactive tool for comparing lists with Venn’s diagrams. BioinfoGP CNB-CSIC. 2007. Available online: https://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/index.html (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- Piñero, J.; Ramírez-Anguita, J.M.; Saüch-Pitarch, J.; Ronzano, F.; Centeno, E.; Sanz, F.; Furlong, L.I. The DisGeNET knowledge platform for disease genomics: 2019 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D845–D855. [Google Scholar]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Gable, A.L.; Nastou, K.C.; Lyon, D.; Kirsch, R.; Pyysalo, S.; Doncheva, N.T.; Legeay, M.; Fang, T.; Bork, P. The STRING database in 2021: Customizable protein–protein networks, and functional characterization of user-uploaded gene/measurement sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D605–D612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, D.W.; Sherman, B.T.; Lempicki, R.A. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 2009, 4, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Drug | Treatment | Dose (p.o.) | Ulcer Index (%) | Inhibition (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCl-EtOH | Vehicle | - | 8.44 ± 3.84 | - |

| Ranitidine | 75 mg/kg | 7.11 ± 4.23 | 15.78 | |

| WCC | 150 mg/kg | 6.91 ± 4.59 | 18.09 | |

| ECC | 150 mg/kg | 4.69 ± 3.39 | 44.46 | |

| EtOH | Vehicle | - | 12.75 ± 4.65 | - |

| Ranitidine | 75 mg/kg | 20.15 ± 11.26 | −58.32 | |

| WCC | 150 mg/kg | 9.21 ± 8.58 | 27.74 | |

| ECC | 150 mg/kg | 8.95 ± 5.74 | 29.74 |

| Treatment | Gastric Juice Volume (mL) | pH | Total Acidity (mEq/4 h) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle | 0.6 ± 0.4 | 2.1 ± 0.8 | 0.040 ± 0.041 |

| Control | 3.5 ± 0.7 | 3.7 ± 1.0 | 0.112 ± 0.055 |

| Lansoprazole | 3.4 ± 0.7 | 6.2 ± 1.0 ** | 0.030 ± 0.018 ** |

| WCC | 2.8 ± 0.7 | 2.9 ± 0.9 | 0.101 ± 0.024 |

| ECC | 2.7 ± 0.6 * | 3.6 ± 0.5 | 0.099 ± 0.028 |

| No. | Uniprot ID | Gene | Relevance Score | Targets | Protein Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Q09472 | EP300 | 23.750 | E1A-binding protein p300 | - |

| 2 | P01584 | IL1B | 18.992 | interleukin 1 beta | - |

| 3 | P01375 | TNF | 12.518 | tumor necrosis factor | Signaling |

| 4 | P10145 | CXCL8 | 11.503 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 8 | Signaling |

| 5 | P05231 | IL6 | 10.297 | interleukin 6 | - |

| 6 | P35354 | PTGS2 | 9.818 | prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 | Enzyme |

| 7 | O00206 | TLR4 | 8.350 | toll-like receptor 4 | - |

| 8 | P35228 | NOS2 | 7.650 | nitric oxide synthase 2 | - |

| 9 | P33261 | CYP2C19 | 7.234 | cytochrome P450 family 2 subfamily C member 19 | - |

| 10 | P14174 | MIF | 6.687 | macrophage migration inhibitory factor | - |

| 11 | P43405 | SYK | 6.451 | spleen-associated tyrosine kinase | Kinase |

| 12 | P19838 | NFKB1 | 6.449 | nuclear factor kappa B subunit 1 | Transcription factor |

| 13 | P54707 | ATP12A | 6.033 | ATPase H+/K+ transporting non-gastric alpha2 subunit | Transporter |

| 14 | P23219 | PTGS1 | 5.667 | prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 1 | Enzyme |

| 15 | P40763 | STAT3 | 5.485 | signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 | Nucleic acid binding |

| 16 | O14684 | PTGES | 4.898 | prostaglandin E synthase | - |

| 17 | P05091 | ALDH2 | 4.614 | aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 family member | Enzyme |

| 18 | P08581 | MET | 3.626 | MET proto-oncogene, receptor tyrosine kinase | Kinase |

| 19 | Q05655 | PRKCD | 3.378 | protein kinase C delta | Kinase |

| 20 | P05164 | MPO | 3.197 | myeloperoxidase | Enzyme |

| 21 | P23458 | JAK1 | 3.146 | Janus kinase 1 | Kinase |

| 22 | P00533 | EGFR | 2.978 | epidermal growth factor receptor | Kinase |

| 23 | P08183 | ABCB1 | 2.735 | ATP binding cassette subfamily B member 1 | Transporter |

| 24 | P14780 | MMP9 | 2.670 | matrix metallopeptidase 9 | Enzyme |

| 25 | P10415 | BCL2 | 2.352 | BCL2 apoptosis regulator | Signaling |

| 26 | P08253 | MMP2 | 2.344 | matrix metallopeptidase 2 | Enzyme |

| 27 | P39877 | PLA2G5 | 2.251 | phospholipase A2 group V | Enzyme |

| 28 | Q06124 | PTPN11 | 1.951 | protein tyrosine phosphatase non-receptor type 11 | - |

| 29 | Q9UBK2 | PPARG | 1.897 | PPARG coactivator 1 alpha | Transcription factor |

| 30 | P15692 | VEGFA | 1.827 | vascular endothelial growth factor A | Signaling |

| 31 | P21980 | TGM2 | 1.812 | transglutaminase 2 | Enzyme |

| 32 | P12821 | ACE | 1.704 | angiotensin I-converting enzyme | Enzyme |

| 33 | Q8NER1 | TRPV1 | 1.702 | transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1 | Ion channel |

| 34 | P09237 | MMP7 | 1.669 | matrix metallopeptidase 7 | Enzyme |

| 35 | Q16236 | NFE2L2 | 1.543 | nuclear factor, erythroid 2-like 2 | Enzyme |

| 36 | P05362 | ICAM1 | 1.526 | intercellular adhesion molecule 1 | - |

| 37 | P09874 | PARP1 | 1.324 | poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 | - |

| 38 | P47989 | XDH | 1.295 | xanthine dehydrogenase | Enzyme |

| 39 | P51681 | CCR5 | 1.266 | C-C motif chemokine receptor 5 (gene/pseudogene) | G-protein-coupled receptor |

| 40 | P49682 | CXCR3 | 1.266 | C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 3 | G-protein-coupled receptor |

| 41 | P00813 | ADA | 1.263 | adenosine deaminase | Enzyme |

| 42 | P16581 | SELE | 1.240 | selectin E | - |

| 43 | P20701 | ITGAL | 1.181 | integrin subunit alpha L | - |

| 44 | P25116 | F2R | 1.181 | coagulation factor II thrombin receptor | G-protein-coupled receptor |

| 45 | P26010 | ITGB7 | 1.179 | integrin subunit beta 7 | Receptor |

| 46 | P08684 | CYP3A4 | 1.164 | cytochrome P450 family 3 subfamily A member 4 | Enzyme |

| 47 | P10721 | KIT | 1.157 | KIT proto-oncogene, receptor tyrosine kinase | Kinase |

| 48 | P22894 | MMP8 | 1.131 | matrix metallopeptidase 8 | Enzyme |

| 49 | P51679 | CCR4 | 1.131 | C-C motif chemokine receptor 4 | G-protein-coupled receptor |

| 50 | P15056 | BRAF | 1.103 | B-Raf proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase | Kinase |

| 51 | P08246 | ELANE | 1.103 | elastase, neutrophil-expressed | Enzyme |

| 52 | P29597 | TYK2 | 1.081 | tyrosine kinase 2 | Kinase |

| 53 | Q08881 | ITK | 1.074 | IL2-inducible T cell kinase | Kinase |

| 54 | P41180 | CASR | 1.074 | calcium-sensing receptor | G-protein-coupled receptor |

| 55 | P05093 | CYP17A1 | 1.074 | cytochrome P450 family 17 subfamily A member 1 | - |

| 56 | P05177 | CYP1A2 | 1.074 | cytochrome P450 family 1 subfamily A member 2 | Enzyme |

| 57 | P14222 | PRF1 | 1.074 | perforin 1 | - |

| 58 | P29274 | ADORA2A | 1.070 | adenosine A2a receptor | G-protein-coupled receptor |

| 59 | P42345 | MTOR | 1.042 | mechanistic target of rapamycin kinase | Kinase |

| No. | Uniprot ID | Gene | Relevance Score | Degree | Betweenness Centrality | Closeness Centrality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | P40763 | STAT3 | 5.485 | 16 | 0.079 | 0.864 |

| 2 | P05231 | IL6 | 10.297 | 15 | 0.057 | 0.826 |

| 3 | P01375 | TNF | 12.503 | 15 | 0.058 | 0.826 |

| 4 | P01584 | IL1B | 18.992 | 13 | 0.026 | 0.760 |

| 5 | O00206 | TLR4 | 8.350 | 13 | 0.041 | 0.760 |

| 6 | P35354 | PTGS2 | 4.898 | 13 | 0.166 | 0.760 |

| 7 | P10145 | CXCL8 | 11.503 | 12 | 0.019 | 0.731 |

| 8 | P05362 | ICAM1 | 1.526 | 12 | 0.031 | 0.731 |

| 9 | P14780 | MMP9 | 2.670 | 11 | 0.007 | 0.704 |

| 10 | P15692 | VEGFA | 1.827 | 11 | 0.020 | 0.704 |

| 11 | P19838 | NFKB1 | 6.449 | 9 | 0.015 | 0.613 |

| 12 | P00533 | EGFR | 2.978 | 9 | 0.012 | 0.655 |

| 13 | P05164 | MPO | 3.197 | 8 | 0.031 | 0.633 |

| 14 | Q06124 | PTPN11 | 1.951 | 8 | 0.009 | 0.594 |

| 15 | Q09472 | EP300 | 23.750 | 7 | 0.003 | 0.576 |

| 16 | P37231 | PPARG | 1.897 | 7 | 0.006 | 0.613 |

| 17 | P23458 | JAK1 | 3.146 | 6 | 0.004 | 0.559 |

| 18 | P43405 | SYK | 6.451 | 6 | 0.006 | 0.559 |

| 19 | P23219 | PTGS1 | 5.667 | 3 | 0.007 | 0.475 |

| 20 | P33261 | CYP2C19 | 7.234 | 2 | 0.000 | 0.463 |

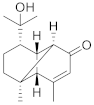

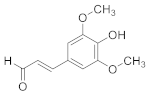

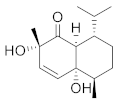

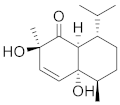

| Compound Name | Structure | Formula | Degree |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geranyl acetate |  | C12H20O2 | 7 |

| Coniferaldehyde |  | C10H10O3 | 7 |

| Cinnamoid E |  | C15H22O2 | 7 |

| Sinapaldehyde |  | C11H12O4 | 6 |

| Cinnamoid C |  | C15H24O3 | 5 |

| Cinnamoid B |  | C15H24O3 | 5 |

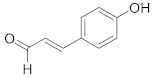

| 4-Hydroxycinnamaldehyde |  | C9H8O2 | 4 |

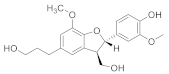

| (7S,8R)-Lawsonicin |  | C20H24O6 | 4 |

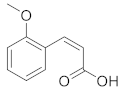

| cis-2-Methoxycinnamic acid |  | C10H10O3 | 4 |

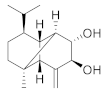

| Cinnamoid D |  | C15H24O2 | 4 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, J.H.; Kwak, H.J.; Shin, D.; Seo, H.J.; Park, S.J.; Hong, B.-H.; Shin, M.-S.; Kim, S.H.; Kang, K.S. Mitigation of Gastric Damage Using Cinnamomum cassia Extract: Network Pharmacological Analysis of Active Compounds and Protection Effects in Rats. Plants 2022, 11, 716. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11060716

Lee JH, Kwak HJ, Shin D, Seo HJ, Park SJ, Hong B-H, Shin M-S, Kim SH, Kang KS. Mitigation of Gastric Damage Using Cinnamomum cassia Extract: Network Pharmacological Analysis of Active Compounds and Protection Effects in Rats. Plants. 2022; 11(6):716. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11060716

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Ji Hwan, Hee Jae Kwak, Dongchul Shin, Hye Jin Seo, Shin Jung Park, Bo-Hee Hong, Myoung-Sook Shin, Seung Hyun Kim, and Ki Sung Kang. 2022. "Mitigation of Gastric Damage Using Cinnamomum cassia Extract: Network Pharmacological Analysis of Active Compounds and Protection Effects in Rats" Plants 11, no. 6: 716. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11060716

APA StyleLee, J. H., Kwak, H. J., Shin, D., Seo, H. J., Park, S. J., Hong, B.-H., Shin, M.-S., Kim, S. H., & Kang, K. S. (2022). Mitigation of Gastric Damage Using Cinnamomum cassia Extract: Network Pharmacological Analysis of Active Compounds and Protection Effects in Rats. Plants, 11(6), 716. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11060716