Abstract

Gunshot detection technology (GDT) has been increasingly adopted by law enforcement agencies to tackle the problem of underreporting of crime via 911 calls for service, which undoubtedly affects the quality of crime mapping and spatial analysis. This article investigates the spatial and temporal patterns of gun violence by comparing data collected from GDT and 911 calls in Louisville, Kentucky. We applied hot spot mapping, near repeat diagnosis, and spatial regression approaches to the analysis of gunshot incidents and their associated neighborhood characteristics. We observed significant discrepancies between GDT data and 911 calls for service, which indicate possible underreporting of firearm discharge in 911 call data. The near repeat analysis suggests an increased risk of gunshots in nearby locations following an initial event. Results of spatial regression models validate the hypothesis of spatial dependence in frequencies of gunshot incidents and crime underreporting across neighborhoods in the study area, both of which are positively associated with proportions of African American residents, who are less likely to report a gunshot. This article adds to a growing body of research on GDT and its benefits for law enforcement activity. Findings from this research not only provide new insights into the spatiotemporal aspects of gun violence in urban areas but also shed light on the issue of underreporting of gun violence.

1. Introduction

The United States is experiencing a decades-long epidemic of gun violence dating back to the 1970s [1]. In recent years, more than 30,000 people die each year from gun violence, with approximately one-third attributed to homicide and two-thirds to suicide, and nearly 70,000 more are non-fatally injured [2,3,4]. The risk of this violence is disproportionately distributed among different demographic groups and across geographic entities at different levels. For example, firearm homicide is the leading cause of death for African American men aged 15–34 with a homicide rate up to 20 times higher than white males, and is the second leading cause of death for African American women aged 15–24 [1]. Geographically, the mortality rate incurred by gun violence varies by state from as low as 3.4/100,000 in Massachusetts to 23.3/100,000 in Alaska [3]. At the local level, scholars have long observed that criminal incidents, especially violent crime, are highly concentrated in disadvantaged inner-city neighborhoods, which are disproportionately resided by minority and low-income residents [5,6,7].

Despite the clear indications of a nationwide crisis of gun violence, research is limited on the subject due in part to limited funding at the federal level since the 1990s [8]. Even when researchers are able to investigate this problem, incident-level data on gun violence are incomplete as it only reflects cases reported to law enforcement from 911 calls for service. In many areas of the country, gun violence is subject to chronic underreporting, especially in dilapidated urban neighborhoods, to the extent that nearly 90% of incidents are never reported, further hindering the reliability and accuracy of spatial analysis and mapping of crime that relies on police-recorded data on gun violence [9]. In two major American cities for example, as few as 12% of gunfire incidents are actually reported to police [9]. In addition to underreporting, 911 calls for service reporting gun violence are subject to the problem of low accuracy because callers oftentimes have limited knowledge about the exact location of a gunshot incident [10]. New technologies such as gunshot detection technology (GDT), however, provide more comprehensive and accurate locational information on gunshot incidents, providing new insights into the spatiotemporal aspects of gun violence in urban areas. This article seeks to investigate the spatial and temporal patterns of gun violence and the underreporting problem of firearm discharge by comparing newly released data collected from GDT and 911 calls for service in Louisville Metro, Kentucky.

1.1. Gunshot Detection Technology

Gunshot detection technology (GDT) is an application of acoustic detection and triangulation to detect and locate sound generated by the muzzle blast of firearm discharge using a network of acoustic sensors installed over an area [11]. Since introduced in the early 1990s, a growing proportion of local law enforcement agencies, especially large police departments, across the U.S. have adopted or planned to implement GDT as a strategy to address urban gun violence [10,11,12]. The Louisville Metro Police Department (LMPD) in Louisville, KY is one such agency that implemented a GDT system provided by the California-based company ShotSpotter in June of 2017. The impact of GDT on actual law enforcement effectiveness is not thoroughly understood yet, but some research suggests that GDT can significantly improve police dispatch and response time [13]. Under a problem-oriented policing framework, GDT presumably helps accurately identify firearm discharge hotspots, thus contributing to the analysis of gunfire problems and enhancing police response efforts [14].

The accuracy and sensitivity of GDT to detect actual gunfire has been shown to vary spatially and temporally, with better performance at nighttime and with increased density of sensors [15]. Sensitivity also varies based on the type of firearm discharged, i.e. better performance with larger caliber weapons [11]. Early field tests for civilian versions of this technology indicated that discharges from shotguns, handguns and rifles were detected 90%, 85% and 63% of the time respectively, and identified the location within an average margin of error of 41 feet [14]. Similarly, field-testing in an urban environment for one manufacturer revealed 83% and 76% detection for handguns and rifles respectively [16]. False positives, or detected events that are not actually the result of a firearm discharge, and false negatives, actual firearm discharge not detected, are key considerations when interpreting and utilizing this type of data. Heavily noisy environments, such as real-world urban settings, have been shown to affect GDT effectiveness where up to 9% of actual gunfire is not detected and approximately 25% of non-gunfire events with a similar acoustic signature, i.e. balloon popping and hand clapping, were falsely identified as gunfire [17]. This evidence supports the observation that GDT systems appear to perform better during the overnight hours when other environmental background noise is lower. Nevertheless, manufacturers are constantly improving their technology and detection algorithms, and GDT has the potential to improve monitoring of urban firearm discharge over traditional methods, thus benefiting law enforcement activity and criminological analysis.

1.2. Spatial Clustering of Gun Violence

Studies to date of gun violence in urban areas show a high degree of spatial clustering, particularly in micro places over time [5,18]. These micro places, such as addresses, facilities, or street segments represent only a small proportion of all places in a specific urban community, but account for most of the criminal activity in urban areas [7,19,20]. Weisburd [7] describes the uneven geographic distribution of crime as the “law of crime concentration at place.” For example, based on data collected for nearly three decades, Braga, Papachristos and Hureau [5] observe epidemic levels of spatial concentration and temporal persistence of gun violence in Boston—over 50% of all gunshot incidents occurred in less than 3% of the city’s street segments and blocks. Larsen, Lane, Jennings-Bey, Haygood-El, Brundage and Rubinstein [6] identify similar levels of spatiotemporal concentration of gun violence in the city of Syracuse, New York and find that the intensity of gun violence is positively correlated with neighborhood sociodemographic factors including segregation and poverty. The clustering nature of gun violence across space and over time provides opportunities for hot spots mapping and prediction of future crime [21].

When evaluating spatiotemporal clustering in more detail, the notion of near-repeat victimization provides a useful way to refine pattern identification for crime phenomena. While the use of near-repeat analysis is well tried in relation to burglary, its application to gun violence is less common [22,23,24,25]. The near-repeat theory suggests that when an originating event occurs, like unlawful firearm discharge, the risk of a subsequent event nearby increases for a short period of time thereafter [26,27]. For example, studies from two major American cities revealed that the risk of near-repeat incidents of gun violence increase by 33–35% within one city block for 2 weeks following the originating incident [22,26]. Other research echoes this finding of increased near-repeat incidents within a city block, and further describes a day/night variance with limited risk of near-repeat during the day and significant increase during nighttime hours [28]. The latest research identifies evidence of spatial and temporal repeat of gun-related violent crime based on GDT recorded data [29]. Research has also shown evidence of near-repeat phenomenon for armed robbery—increased risk within three city blocks and 1 week of the initiating event, and it is possible to link known long-term hotspots to patterns of increased near-repeat events [30].

Social disorganization theory in the literature of environmental criminology offers a valuable theoretical framework for explaining spatially the patterns of crime. This theory suggests that social and environmental factors including socioeconomic deprivation, family disruption, residential mobility, and ethnic heterogeneity all contribute to the geographical concentration of crime in urban areas [31,32,33]. Guided by social disorganization theory, Larsen, Lane, Jennings-Bey, Haygood-El, Brundage and Rubinstein [6] find gun violence is spatially correlated with higher rates of poverty and segregation in Syracuse, New York. Moreover, the lack of informal social control (or cohesion) and collective efficacy may exacerbate the violent level of poverty-stricken neighborhoods and explain the chronic underreporting issue of gun violence in American cities [34]. In light of the fact that crime-ridden neighborhoods are often highly segregated and disproportionately dominated by African Americans, research has documented remarkable racial disparities in citizen confidence in police, namely that black residents are half as likely to have a positive view of local police and are about 24% less likely to report crime [35,36]. Furthermore, issues of desensitization by frequent exposure may also affect residents’ behavior and the likelihood of reporting crime [37,38]. This can be explained by the broken window theory that posits residents’ lack of care and participation in crime prevention endeavors can aggravate criminal behavior and violence [39].

2. Data and Methods

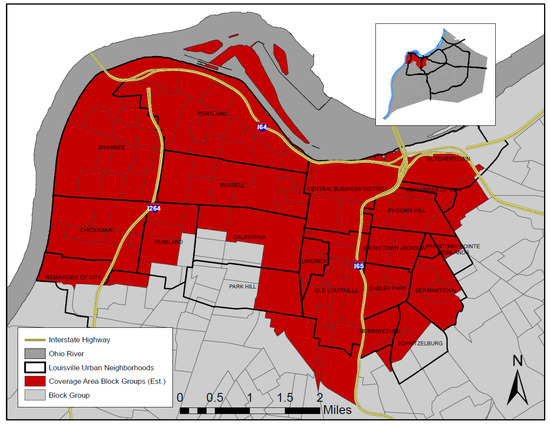

The GDT implemented by LMPD is integrated into the computer-aided dispatch system where gunshots detected by the GDT system will generate a dispatch call. The data for this article were obtained through an open records request to LMPD for dispatch data for June 2017 through September 2017 including dispatch codes 1044-GDT events and 1040-911 calls for service reporting gunshots in the area. Locational information such as latitude and longitude coordinates for GDT incidents and street addresses for each call for service in the above data set allowed us to map and analyze the spatial patterns of gunshots in the study area. The precise coverage area of the GDT system was not released for this study by LMPD, but has been estimated based on the distribution of recorded GDT events. According to published information from the GDT manufacturer, 200–250 m is the maximum effective range of any single sensor [40]. Therefore, the estimated study area includes 82 block groups that intersect a 250m radius of any recorded GDT event located in 21 neighborhoods in West Louisville (Figure 1). The census block group shapefile was acquired from the U.S. Census Bureau along with census variables collected by the American Community Survey (ACS) 2012–2016 5-year estimates. Jefferson County streets and neighborhoods shapefiles were obtained from Louisville/Jefferson County Information Consortium (LOJIC). All data sets were projected into NAD 1983 State Plane for Kentucky North (FIPS 1601 Feet) for ease of spatial analysis.

Figure 1.

Study area: Estimated coverage area for gunshot detection system in Louisville, KY based on recorded GDT events, June–September, 2017, which includes 82 block groups and portions of 20 urban neighborhoods in West Louisville.

The conceptual framework for this investigation consists of a four-stage analysis including hotspot analysis, near repeat diagnosis, temporal association, and regression analysis of the correlates of gunshots. Hotspot analysis helps reveal statistically significant hot and cold spots of gun violence across space. Near repeat analysis enables us to identify spatial and temporal repentance of criminal incidents. To date, near repeat analysis of gun violence has largely relied on the use of police-reported data, and this article is one of the first known attempts to apply it to GDT data [29]. Further, analyzing GDT data relative to calls for service should highlight areas where gun violence is chronically underreported, a widespread problem (especially in low-income neighborhoods) plaguing crime analysis [41]. Temporal association comparison of a GDT event and calls for service identify unreported events and patterns of underreporting. Finally, a spatial regression analysis allows us to better understand the correlates of gunshots and possible explanations for underreporting of gun violence.

Following geocoding of the two types of data on gunshots, GDT events were separated from calls for service into distinct shapefiles for subsequent spatial analysis. Optimized hotspot analysis using the Getis-Ord Gi* statistic, an extension of ArcGIS 10.5, was employed to identify statistically significant hotspots of GDT events and calls for service. This extension offers a form of grid cell mapping and uses surface estimation to display ‘hot’ and ‘cold’ spots of activity relative to the global average for a study area [42]. Gunshot incidents were then aggregated to fishnet grids with a spatial resolution of 900 ft. bounded by the estimated GDT coverage area. In contrast to the coverage area delineated by census block groups, a revised study area was identified by mapping a 250 m buffer around each detected gunshot event and merging every buffer into a single polygon. Two-hundred-and-fifty meters was used to refine the coverage area based on technical data from the manufacturer of the GDT system that indicates 250 m is the maximum range for accurate detection by the sensors. GDT events were also aggregated by land use type in the refined study area. To measure the relative concentration of GDT events by land use type, location quotients were calculated for each category of land use. Location quotients were calculated using the total count of GDT events for each land use category and the total area in square feet provided in the parcel shapefile. Time series analysis was used to describe the time of day trends in detected GDT events in relation to the volume of calls for service. Moreover, by comparing the disparities in temporal distribution between GDT data and 911 calls, we extracted GDT events that did not have an associated call for service recorded within a reasonable period from adjacent areas. These events represent areas where firearm discharge is frequently underreported. Unreported events were defined as a detected GDT event without a call for service recorded in the following hour and within a 1-kilometer radius.

Near-repeat analysis was carried out using the Near Repeat Calculator, version 1.3 [43]. Within the tool, two temporal bandwidths were tested: 1 day with seven bands and 7 days with three bands. Both models used a spatial bandwidth of 400 feet and three bands. Statistical significance level was set at p = 0.05 and a Manhattan distance setting selected. The near repeat analysis allows us to diagnose if the observed numbers of gunshots in each spatiotemporal bandwidth were statistically higher than a random distribution after an initial incident occurred [26].

We first performed ordinary least squares (OLS) regression to explore possible explanatory variables for the spatial clustering of GDT recorded gunshots and patterns of chronic underreporting in two sets of models. The dependent variables for each regression model were calculated by aggregating all GDT events and all underreported GDT events in each block group, of which 82 reside in the study area. Social disorganization and broken window theories steered the selection of independent variables including the percent of single parent-headed households with children, percent of properties listed as vacant, percent of population over 25 years with no high school diploma, percent of households in poverty, percent of black population, percent of housing units that are renter occupied, and percent of female-headed households. The percent of population identifying as black is included in consideration of documented racial disparities in police confidence and elevated tensions between black communities and police across the country after the Ferguson shooting incident in 2014 [44,45]. Additional variables included males aged 15–25, median age and percent of households with children.

Based on the results of OLS regression, we applied a spatial lag model to address the issue of spatial autocorrelation that often exists among geographically referenced data and plagues the authenticity of OLS regression analysis. In particular, the alternative spatial lag model was conducted by including spatially lagged values of the dependent variable as an additional independent variable in regression analysis. Specifically, a queen-based contiguity criterion was used to determine the neighbors surrounding each block group and calculate the spatially lagged values of the dependent variable for each observation. We used GeoDa, open source software widely used for spatial statistical analysis, to create spatial weights and perform spatial regression models, which employ maximum likelihood estimations, not OLS [46].

3. Results

3.1. Spatial and Temporal Patterns of Gunshots

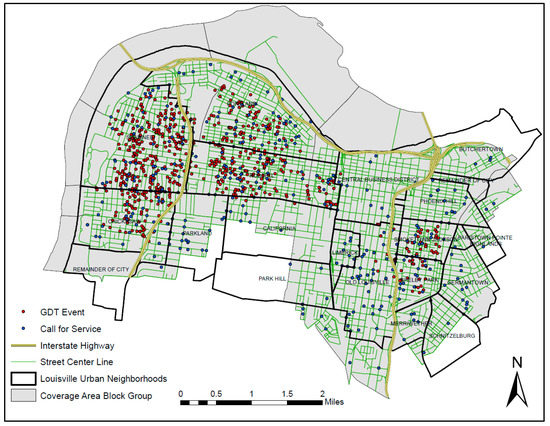

The LMPD dispatch data contained 729 GDT events and 387 calls for service for gunshots fired in the study area. Of the 729 GDT events recorded, only 85 events had a corresponding call for service within a 1-hour window of the GDT event. The average distance from a GDT event to the nearest call for service was 402 feet, which corresponds to the approximate length of a typical city block. The overall distribution of GDT events and calls for service shows a generally higher concentration across the Western portion of the study area (Figure 2). This area primarily includes four urban neighborhoods including Chickasaw, Shawnee, Portland, and Russell. Many recorded calls for service appeared in areas where GDT events were not detected, which may illustrate the functional boundary of the GDT detection area.

Figure 2.

Distribution of GDT events and calls for service for shots fired in the study area.

With regard to land use and the distribution of GDT events, single family and multi-family properties experienced 71% of all events (Table 1). Vacant, public semi-public, right-of-way, and commercial land accounted for 26% of events and industrial and parklands accounted for only 3% of events. Among all land use types, single family, multi-family, and vacant properties have location quotient values larger than 1 (in bold), which means they had much higher frequencies of gunshots than other types of land use in the study area.

Table 1.

Sum and distribution of GDT events by land use type including location quotients.

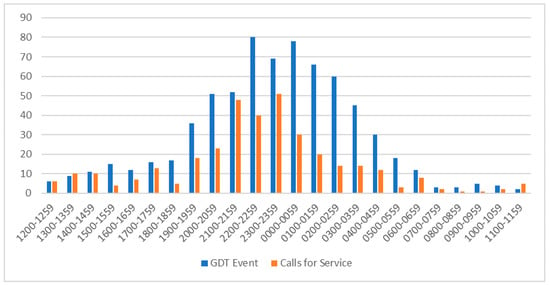

The temporal trend GDT events vs. calls for service by hour of the day increase first from noon to midnight and then decrease from midnight to daybreak with the 10 pm and midnight hours experiencing the highest frequencies (Figure 3). Furthermore, the peak hours for GDT events display a relatively low ratio of calls for service indicating that the rate of underreporting varied by time of day as well, with less underreporting during daylight hours and peak underreporting between midnight and 6:00am.

Figure 3.

GDT events and calls for service by hour of the day, starting at noon.

Police dispositions for all GDT events were recorded in the dispatch data (Table 2). Eighty-one percent of all events were documented as either unfounded or cleared without taking a report. Police were only able to take a witness report 12% of the time and only two arrests were recorded for dispatched events.

Table 2.

Disposition for all GDT events and calls for service in Louisville, KY.

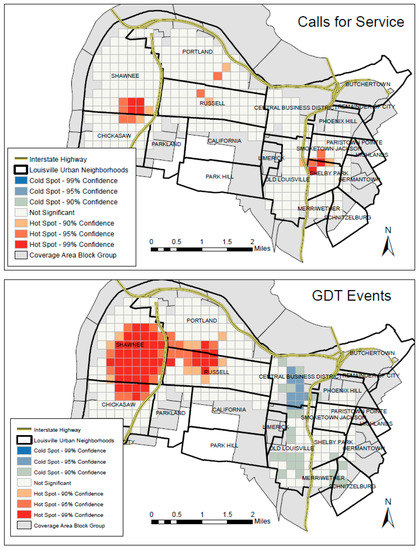

3.2. Hotspot Analysis

Calls for service display concentrated hotspots in the Smoketown neighborhood of central Louisville and at the border of the Chickasaw and Shawnee neighborhoods of West Louisville (Figure 4). Hotspots for GDT events are more widespread across west Louisville with a single cold spot in the Central Business District. In comparison to the hot spots derived from calls for service, it is remarkable that GDT-generated hot spots were more spatially extensive in the West End of the study area, which is notoriously known for high levels of segregation, poverty and violent crime. The noticeable discrepancies between GDT data and calls for service in magnitude and spatial coverage suggest possible underreporting of firearm discharge in 911 call for service data, especially in disadvantaged inner city neighborhoods.

Figure 4.

Hotspot analysis of calls for service vs. GDT events in Louisville, KY.

While it was not possible with this dataset to relate a specific GDT event to a call for service, the association is estimated by linking any call for service that was received within1 hour of a detected event within a 250 m search radius. As noted in the previous section, only 85 GDT events were found to have an associated call for service, leaving 644 events estimated to be unreported.

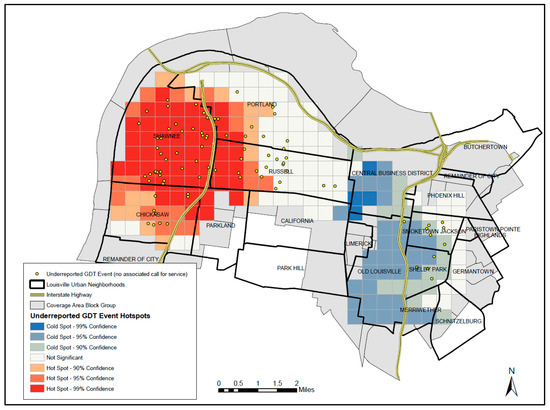

These GDT events identified that fall outside the call radius were isolated for further hotspot and regression analysis. To determine the statistical significance of these clusters, results from optimized hot spot analysis are depicted in Figure 5. The hot spots of underreported GDT events were heavily concentrated in the Shawnee neighborhood and the western edge of the Russell neighborhood in West Louisville.

Figure 5.

Hot spot analysis for underreported GDT events.

3.3. Near Repeat Analysis

Results of the near repeat analysis using 1-week and 1-day temporal intervals and a 400-ft spatial bandwidth suggest that the near repeat phenomenon exists within 800 feet or roughly two city blocks (Table 3). Numbers marked in bold indicate statistically higher frequencies of near-repeat gunshots in geographical and temporal proximity following the occurrence of an initial event. Under the weeklong temporal bandwidth, the statistically significant near repeats are limited to 1 week and 800 feet. Using the 1-day band, the significant near repeats are further refined to only exist for 2 days within one city block and 1 day for two blocks.

Table 3.

Observed gunshots over mean expected frequencies using spatiotemporal bandwidths.

3.4. Regression Analysis

Summary statistics for GDT events demonstrate a mean of 8.9 detected gunshots across block groups in the study period with a standard deviation of 10.19 (Table 4). The number of underreported events is lower with a mean of 3.9 and a standard deviation of 5.10. Summary statistics for the independent variables suggest generally higher rates of renter-occupied and single-parent households as well as low income with a mean median income close to the poverty level.

Table 4.

Summary statistics for the dependent and independent variables in regression analysis (n = 82).

Regression results for all GDT events suggest that the percent of vacant housing and percent blacks were both positively correlated with the total number of gunshot events across block groups (Table 5). Other independent variables show insignificant regression coefficients. A diagnosis of Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values for all the independent variables indicates no violation of multicollinearity. About 34% of the variation in total GDT gunshots across block groups (the dependent variable) was explained by the OLS regression model. The Global Moran’s I value was significant, however, this indicates spatial autocorrelation among OLS model residuals that warrants a spatial regression model to be performed.

Table 5.

Results of OLS and spatial regression models for all GDT events (n = 82).

The results of the spatial lag model show improved model performance indicated by a larger R-squared and smaller AIC values but only percent blacks remains significant (Table 5). The inclusion of a spatially-lagged dependent variable (i.e., spatial lag term) shows a statistically significant and positive regression coefficient indicating the spatially-dependent nature of GDT incidents. While the model performance has improved, the significant Likelihood Ratio Test is still significant, indicating that the spatial effects were not completely removed.

Regression results for underreported GDT events suggest that the percent blacks is positively correlated with unreported gunshot events across block groups (Table 6). Likewise, the vacant property shows a positive regression coefficient and is nearly significant (i.e., p-value = 0.054). The OLS model explains over 25% of the variation of underreported gunshots. The significant Global Moran’s I value indicates the existence of spatial autocorrelation among OLS residuals that needs to be addressed.

Table 6.

Results of OLS and spatial regression analysis for underreported events (n = 82).

The results of the spatial lag model show an improvement in model performance indicated by a smaller AIC index, and percent black remains the only significant variable. The spatially-lagged dependent variable (i.e., spatial lag term) shows a significant positive coefficient indicating the existence of spatial autocorrelation among block groups regarding the measure of unreported GDT incidents.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

This article analyzes the spatiotemporal patterns of firearm discharge using both GDT-recorded data and 911 calls for service in the northwest portion of Louisville, KY. This analysis reveals clear hotspots of gunshot events and more importantly, underreported events. The results suggest that over the study area, only a small proportion of GDT-recorded events (i.e., 12% of 729) were matched by 911 calls to police reporting gunshots. The remarkable discrepancies between GDT data and calls for service in magnitude and spatial coverage suggest possible underreporting of firearm discharge in 911 calls for service data. This observation is consistent with Carr and Doleac [9] that state similar quantities of gunshots were reported to police by 911 calls for service. This finding partially demonstrates the advantage of GDT over conventional 911 calls, in that it can generate immediate and relatively precise reports of firearm discharge even when witnesses fail to report. This particular study has identified concentrated areas of under-reporting for gunshots in the Shawnee neighborhood and the western edge of the Russell neighborhood in West Louisville. Reasons for under-reporting are likely varied, but may include elements of desensitization, lack of trust in police or fatalism. Desensitization could arise when residents become accustomed to frequent gunfire. In addition, residents may not trust that law enforcement is there to help or even able to protect citizens. In relation, fatalism is the idea that a person cannot change their situation or outcome, essentially resigning to their situation or surroundings.

Regression results validate the prevalence of spatial dependence among nearby block groups and reveal that percent black is the major factor that is positively related to GDT events and underreporting of gunshots. This observation reinforces other research that suggests racial disparities exist for gun violence and in population confidence and trust in police [35,36,47]. The disposition of GDT dispatches also speaks to the issue of underreporting when police were only able to take a report at the scene 12% of the time when responding to a GDT event. Disparities in confidence and trust in police are not as simple as racial divisions alone. Future research should seek to unpack the nuance of subpopulations and their confidence in law enforcement.

This type of analysis may be particularly beneficial to law enforcement agencies under the scope of tactical crime analysis and short-term or immediate response strategies. The primary pattern identified here is a hot spot of underreporting of firearm discharge, but this observation may also mirror the underreporting of crime in general, an issue known as the crime funnel [48]. Again, future research may benefit from the evaluation of all types of crimes that occur in and around these hot spots. Police strategies that address this phenomenon could include directed patrols and field contacts in the short term. Under a long-term strategy, community policing should be considered as a specific strategy to address the problem of underreporting. Police will need to build trust in the community if they wish to gain improved rates of calls and reports for service.

The near repeat component of this study suggests that a 1–2 block radius around an initiating incident will experience an increased risk in the first week, particularly in the 1–2 days following an incident. This is relatively consistent with other urban near repeat studies of gun violence and for other types of crime, such as armed robbery [22,26,28,30] and burglaries [27,49,50]. Moreover, findings on the near repeat nature of gun violence based on GDT data, an improved measure that may potentially reduce the problem of underreporting of criminal incidents, have implications for helping law enforcement agencies predict and prevent future crime.

One limitation of GDT data in general is the lack of confirmation that all GDT-recorded urban firearm discharge is unlawful. In the case of this dataset, 81% of all GDT events were cleared with no report or recorded as unfounded by responding officers, and only two arrests (<1%) were made that were directly attributable to GDT recorded information. If those cleared or unreported GDT records were truly false positives, it may result in the waste of police resources when responding to those false alerts [12]. In addition, high rates of false alarms may trigger iatrogenic effects of police on tracking gun violence alarms generated by GDT. However, one cannot entirely repudiate the value of the GDT system in consideration of the inherently low clearance or arrest rate for violent crime. Nevertheless, on a larger scale, the data collected by GDT appears to complement classical 911 calls for service and provides a more representative depiction of the spatial patterns of gunshot violence in America’s urban areas like Louisville. Therefore, while it is important to push providers to constantly improve the accuracy and quality of GDT or other similar systems, we call for more research to incorporate GDT data into the spatiotemporal analysis and mapping of gunshots that has traditionally relied on police-recorded 911 calls.

Additionally, future research analyzing GDT data in comparison to calls for service should address other potential issues such as duplicate calls reporting a single shooting event in a community or multiple GDT alarms being generated from a single shooting event with several firearm discharges, which inevitably biases the measurement and analysis of gun violence in urban communities. The methods we have used to estimate the degree of underreporting of gunshots by matching GDT alerts with calls for service can be improved by verifying and removing the abovementioned duplicate events, resulting from either calls for service or the GDT system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.R.; Methodology, W.R. and C.H.Z.; Software, W.R.; Validation, W.R. and C.H.Z.; Formal Analysis, W.R.; Investigation, W.R. and C.H.Z.; Resources, W.R.; Data Curation, W.R.; Writing-Original Draft Preparation, W.R.; Writing-Review & Editing, W.R. and C.H.Z.; Visualization, W.R.; Supervision, W.R. and C.H.Z.; Project Administration, W.R. and C.H.Z.; Funding Acquisition, W.R. and C.H.Z.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We thank Louisville Metro Police Department (LMPD) for providing data on gunshot incidents and thank the three anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions that dramatically helped improve the quality of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wintemute, G.J. The epidemiology of firearm violence in the twenty-first century United States. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2015, 36, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauchner, H.; Rivara, F.P.; Bonow, R.O.; Bressler, N.M.; Disis, M.L. (Nora); Heckers, S.; Piccirillo, J.F.; Redberg, R.F.; Rhee, J.S.; Robinson, J.K.; et al. Death by gun violence—A public health crisis. JAMA Intern. Med. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDC. Firearm Mortality by State. Available online: www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/sosmap/firearm_mortality/firearm.html (accessed on 24 April 2018).

- Fowler, K.A.; Dahlberg, L.L.; Haileyesus, T.; Annest, J.L. Firearm injuries in the United States. Prev. Med. 2015, 79, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braga, A.A.; Papachristos, A.V.; Hureau, D.M. The concentration and stability of gun violence at micro places in Boston, 1980–2008. J. Quant. Criminol. 2010, 26, 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, D.A.; Lane, S.; Jennings-Bey, T.; Haygood-El, A.; Brundage, K.; Rubinstein, R.A. Spatio-temporal patterns of gun violence in Syracuse, New York 2009–2015. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0173001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weisburd, D. The law of crime concentration and the criminology of place. Criminology 2015, 53, 133–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hills-Evans, K.; Mitton, J.; Sacks, C.A. Stop posturing and start problem solving: A call for research to prevent gun violence. AMA J Ethics 2018, 20, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Carr, J.; Doleac, J.L. The geography, incidence, and underreporting of gun violence: New evidence using ShotSpotter data. SSRN Electron. J. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, D.S.; La Vigne, N.G.; Goff, M.; Thompson, P.S. Lessons Learned Implementing Gunshot Detection Technology: Results of a Process Evaluation in Three Major Cities. Justice Eval. J. 2018, 1, 109–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazerolle, L.G.; National Institute of Justice. Random Gunfire Problems and Gunshot Detection Systems; U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice: Washington, DC, USA, 1999; p. 7.

- Ratcliffe, J.H.; Lattanzio, M.; Kikuchi, G.; Thomas, K. A partially randomized field experiment on the effect of an acoustic gunshot detection system on police incident reports. J. Exp. Criminol. 2019, 15, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.-S.; Librett, M.; Collins, T.J. An empirical evaluation: Gunshot detection system and its effectiveness on police practices. Police Pract. Res. 2014, 15, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, C.; Green Mazerolle, L.; Rogan, D.; Frank, J. Technological approaches to controlling random gunfire: Results of a gunshot detection system field test. Polic. Int. J. 2002, 25, 345–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvin-Erickson, Y.; La Vigne, N.; Levine, N.; Tiry, E.; Bieler, S. What does Gunshot Detection Technology tell us about gun violence? Appl. Geogr. 2017, 86, 262–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litch, M.; Shaw, S. Implementing the SECURES urban gunshot detection technology for law enforcement crime intervention strategies. In Proceedings of the Sensors, and Command, Control, Communications, and Intelligence (C3I) Technologies for Homeland Security and Homeland Defense III, Baltimore, MD, USA, 20–22 April 2015; pp. 484–493. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, I.; Apolinario, J. Gunshot detection in noisy environments. In Proceeding of the 7th International Telecommunications Symposium, Manaus, Brazil, September 2010; Available online: http://www.ime.eb.br/~apolin/papers/ITS2010Izabela.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2019).

- Loeffler, C.; Flaxman, S. Is gun violence contagious? A spatiotemporal test. J. Quant. Criminol. 2018, 34, 999–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenbeek, W.; Weisburd, D. Where the action is in crime? an examination of variability of crime across different spatial units in the hague, 2001–2009. J. Quant. Criminol. 2016, 32, 449–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andresen, M.A.; Curman, A.S.; Linning, S.J. The trajectories of crime at places: Understanding the patterns of disaggregated crime types. J. Quant. Criminol. 2017, 33, 427–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohler, G. Marked point process hotspot maps for homicide and gun crime prediction in Chicago. Int. J. Forecast. 2014, 30, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, W.; Wu, L.; Ye, X. Patterns of near-repeat gun assaults in Houston. J. Res. Crime Delinq. 2012, 49, 186–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturup, J.; Rostami, A.; Gerell, M.; Sandholm, A. Near-repeat shootings in contemporary Sweden 2011 to 2015. Secur. J. 2018, 31, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyant, B.R.; Taylor, R.B.; Ratcliffe, J.H.; Wood, J. Deterrence, firearm arrests, and subsequent shootings: A micro-level spatio-temporal analysis. Justice Q. 2012, 29, 524–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturup, J.; Gerell, M.; Rostami, A. Explosive violence: A near-repeat study of hand grenade detonations and shootings in urban Sweden. Eur. J. Criminol. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratcliffe, J.H.; Rengert, G.F. Near-repeat patterns in Philadelphia shootings. Secur. J. 2008, 21, 58–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsley, M.; Homel, R.; Chaseling, J. Infectious burglaries. A test of the near repeat hypothesis. Br. J. Criminol. 2003, 43, 615–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyinam, C. Investigating the applicability of the near-repeat spatio-temporal phenomenon to shot(s) fired incidents: A city level analysis. Crime Mapp. Anal. News. 2016, Fall 2016, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Mazeika, D.M.; Uriarte, L. The near repeats of gun violence using acoustic triangulation data. Secur. J. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haberman, C.P.; Ratcliffe, J.H. The predictive policing challenges of near repeat armed street robberies. Polic. J. Policy Pract. 2012, 6, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Paez, A.; Liu, D. Persistance of crime hot spots: An ordered probit analysis. Geogr. Anal. 2017, 2017, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, R.J.; Groves, W.B. Community structure and crime: Testing social disorganization theory. Am. J. Sociol. 1989, 94, 774–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, C.R.; Mckay, H.D. Juvenile Delinquency and Urban Areas: A Study of Rates of Delinquencies in Relation to Differential Characteristics of Local Communities in American Cities; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1942. [Google Scholar]

- Bursik, R.J., Jr. The informal control of crime through neighborhood networks. Sociol. Focus 1999, 32, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekins, E. Policing in America: Understanding Public Attitudes Toward the Police. Results from a National Survey; CATO Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Morin, R.; Stepler, R. The Racial Confidence Gap in Police Performance; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mrug, S.; Madan, A.; Cook, E.W., 3rd; Wright, R.A. Emotional and physiological desensitization to real-life and movie violence. J. Youth Adolesc. 2015, 44, 1092–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tella, R.; Freira, L.; Gálvez, R.; Schargrodsky, E.; Shalom, D.; Sigman, M. Crime and violence: Desensitization in victims to watching criminal events. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.Q.; Kelling, G.L. The police and neighborhood safety: Broken windows. Atl. Mon. 1982, 127, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- SST Inc. ShotSpotter Whitepaper: Gunshot Detection Technology; SST Inc.: Rowley, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tita, G.E.; Petras, T.L.; Greenbaum, R.T. Crime and residential choice: A neighborhood level analysis of the impact of crime on housing prices. J. Quant. Criminol. 2006, 22, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Association of Crime Analysis. Identifying High Crime Areas (White Paper 2013-02); International Association of Crime Analysis: Overland Park, KS, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe, J. Near Repeat Calculator (Version 1.3); Temple University and the National Institute of Justice: Philidelphia, PA, USA; Washington, DC, USA, 2009.

- Derickson, K.D. Urban geography II: Urban geography in the Age of Ferguson. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2016, 41, 230–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyrooz, D.C.; Decker, S.H.; Wolfe, S.E.; Shjarback, J.A. Was there a Ferguson Effect on crime rates in large U.S. cities? J. Crim. Justice 2016, 46, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselin, L.; Syabri, I.; Kho, Y. GeoDa: An introduction to spatial data analysis. Geogr. Anal. 2006, 38, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beard, J.H.; Morrison, C.N.; Jacoby, S.F.; Dong, B.; Smith, R.; Sims, C.A.; Wiebe, D.J. Quantifying disparities in urban firearm violence by race and place in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: A cartographic study. Am. J. Public Health 2017, 107, 371–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, B.; Paynich, R. Fundamentals of Crime Mapping; Jones & Bartlett Publishers: Burlington, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chainey, S.P.; da Silva, B.F.A. Examining the extent of repeat and near repeat victimisation of domestic burglaries in Belo Horizonte, Brazil. Crime Sci. 2016, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagovsky, A.; Johnson, S.D. When does near repeat burglary victimization occur? Aust. N. Z. J. Criminol. 2007, 40, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).