Abstract

People share data in different ways. Many of them contribute on a voluntary basis, while others are unaware of their contribution. They have differing intentions, collaborate in different ways, and they contribute data about differing aspects. Shared Data Sources have been explored individually in the literature, in particular OpenStreetMap and Twitter, and some types of Shared Data Sources have widely been studied, such as Volunteered Geographic Information (VGI), Ambient Geographic Information (AGI), and Public Participation Geographic Information Systems (PPGIS). A thorough and systematic discussion of Shared Data Sources in their entirety is, however, still missing. For the purpose of establishing such a discussion, we introduce in this article a schema consisting of a number of dimensions for characterizing socially produced, maintained, and used ‘Shared Data Sources,’ as well as corresponding visualization techniques. Both the schema and the visualization techniques allow for a common characterization in order to set individual data sources into context and to identify clusters of Shared Data Sources with common characteristics. Among others, this makes possible choosing suitable Shared Data Sources for a given task and gaining an understanding of how to interpret them by drawing parallels between several Shared Data Sources.

1. Introduction

Data are increasingly produced, maintained, and used by heterogeneous groups of people, across cultures, country borders, differing levels of education, and so forth, which leads to a diversity of characteristics [1]. Among others, data are often stored in a loose format or even different formats within one dataset; people often have diverse motivations to contribute and use data; and the data are maintained with differing intensity. Further, such differences lead to a different degree of organization and collaboration among the contributors and users of a dataset. These factors pose major challenges to the interpretation and use of such data. Instead of well-defined ontologies, the data often need to be interpreted on-the-fly and while considering the context of its genesis. The geographical domain challenges the interpretation of data in a particular way because geographical data is often of intercultural and global nature.

Data (and corresponding projects) that are the result of a social process have been termed in different ways, among them ‘User-Generated Data’ and ‘User-Created Content’ [2]. These and other terms are often context dependent and refer thus only to a subset of such data sources. They possess a connotation and do thus not communicate the class of such datasets in its uttermost generality. The term ‘User-Generated Data’ refers, e.g., to the creation process of the data rather than also to their use. This is why we coin the term ‘Shared Data Sources’ (SDS) as a more generic umbrella term without such a connotation. We define: A dataset or project is called a ‘Shared Data Source’ if its production, maintenance, and use are predominantly social processes.

The reason behind the introduction and choice of the term ‘SDS’ is manifold. First, the term ‘SDS’ puts emphasis on the fact that the data are the result of a creation and maintenance process and are used in some social context. A ‘source’ refers to the process from which the data derives and by that also to its use—the creation process usually has the aim of producing data for a certain use, and the future use is the reason for why the data is created. In comparison, most of the terms used to identify a subset of SDSs refer to either information or data, such as Volunteered Geographic Information, while only some refer to a process [3]. The term ‘SDS’ contains reference to both the data and the process. Secondly, the introduction of the term ‘SDS’ is meant to highlight that all three aspects (data creation, maintenance, and use) need to predominantly be of social nature. Data created in a social process but used only by a single company is not an SDS, and data created by a small number of people is neither as long as the social interaction between these people does not strongly influence and shape the resulting data. The social nature of SDSs is, in fact, determining because mere technical aspects become less important whenever the data is shaped by a social process [4].

In addition to the term ‘Shared Data Source’, we coin the term ‘Geographical Shared Data Source’ (GSDS) for referring to an SDS in the geographical domain. At first hand, one might question why this term should be introduced because the restriction to a specific domain does not seem to be vital. In fact, many factors that relate to the heterogeneity of the social process, among them the cultural, social, and educational background of the involved people, are acknowledged to be significant to geography. When an SDS is about geographical content on a global scale1, its creation, maintenance, and use are thus often particularly subject to social influence. This is why we use GSDSs as examples in the following.

This article focusses on the methodological challenge of making sense of SDSs, both individually by setting an SDS in the context of others and by more holistically examining a larger number of SDSs in their entirety. Thereby, the following research questions are addressed:

- RQ1

- Which ‘dimensions’ can be used to characterize an SDS?The social nature of SDSs imposes structural complexity to both the data and the entire projects. There exist hence a multitude of dimensions, which can be used to characterize an SDS. Which of these dimensions are important and how can they be grouped by their role in the process of creating, maintaining, and using the data? Further, how can one evaluate the importance of a certain dimension for characterizing an SDS?

- RQ2

- How to characterize an SDS in the context of other SDSs? And how to characterize the change of an SDS over time?A characterization of an SDS relative to other ones is particularly efficient because differences and similarities become apparent. Again, the dimensions discussed in RQ1 can be utilized for such a comparison. Which methods exist to measure distances between SDSs? How to investigate similarities and differences between SDSs by visualizations? And how to trace changes of an SDS over time, i.e., the evolution of an SDS?

- RQ3

- How to choose suitable prototypes for grouping SDSs by their characteristics? And how to assess existing prototypes?Shared Data Sources are commonly classified into different types2, among them, Volunteered Geographic Information (VGI; Goodchild [8]), Ambient Geographic Information (AGI; [9]), and Public Participation Geographic Information Systems (PPGIS; [10]). Such typification creates obstacles: the types are fuzzy to some degree, they overlap, and the typification is often ambiguous. As a result, the definitions of these types evolve over time and even different definitions coexist. How can we identify groups of SDSs that share common characteristics? How to evaluate and visualize their fuzziness? And how to make sense of SDSs evolving over time in terms of prototypes?

It should be noted that these questions are of mere methodological nature. In this article, we propose conceptual means for characterizing ‘(Geographical) Shared Data Sources’. The proposed dimensions and the discussed prototypes (VGI, PGI3, and AGI) serve only as examples, and additional dimensions and prototypes can easily be integrated into the proposed framework. It is the aim of the article to discuss the methodological chances and issues of how to make sense of SDSs in their mutual context by utilizing the proposed framework. Thereby, we introduce new lenses for the interpretation of the data incorporating their genesis and characteristics, which allows for a more fine-grained typification of SDSs. The practical usefulness of the approach is demonstrated by setting GSDSs mutually into context and by discussing existing prototypes in terms of GSDSs.

The article is structured as follows. After a literature review, we establish the notions of the prototypes VGI, PGI, and AGI as well as of SDSs and GSDSs (Section 2). Further, we argue why a conceptual framework for setting SDSs mutually into context is needed (Section 3). It suggests itself to conceptualize SDSs by their characteristics in such a framework. These characteristics can formally be represented by several dimensions, which describe different aspects of an SDS (Section 4). Visualizations and statistical analysis can take advantage of these dimensions when analysing SDSs. We have described a large number of SDSs from the geographical domain, which can be set in context relative to the prototypes. As a result, the entirety of the described GSDSs, and not only individual ones, can be examined both visually and statistically. The utilized methods of visualization are by no means the only ones. We describe in detail why they are suitable and which aspects they focus on (Section 5). Finally, the findings of our analysis are discussed. In particular, we show that the introduced dimensions are compatible to a high degree with both a (common) thematic categorization of the SDSs as well as with the prototypes of VGI, PGI, and AGI, which is why the dimensions can serve as a reference frame for characterizing SDSs. This demonstrates the usefulness of the proposed methodological means (Section 6).

3. The Need for a Conceptual Framework

Understanding the characteristics of an SDS, potentially also of a GSDS, is an important task when making sense and use of data. How could we otherwise know how to interpret the data, and how could we estimate the quality and the fitness for a certain purpose? In this section, we argue that the characteristics of an individual SDS becomes apparent when it is set into the context of other SDSs. Thereby, we discuss how to compare the characteristics of different SDSs in a conceptual space and why it is important to characterize a set of SDSs as a whole.

3.1. Relative Characterization of Individual Data Sources

The interpretation and use of data presumes an understanding of how to ground the data, i.e., of how to make sense of the data in terms of the real world and make it thus usable as information [31]. To establish such a grounding, it is important to explore the representation in respect to many aspects. The resulting characterization of the data provides manifold information, e.g., about the motivation behind the collection of the data, the potentially very heterogeneous collection process, the varied consumption of the data, and so forth. Also, such a characterization can contain information about the quality of the data and, as SDSs are the result of a social creation process, data quality often depends and can be characterized based on these social processes [1,4]. Data quality is actually able to demonstrate the complexity of such aspects. It can, e.g., be assessed by a comparison to reference data, which is considered as being of superior quality [32,33]. Instead of such a comparison to another dataset, data can also be assessed intrinsically by examining whether patterns and laws typical to a certain type of data also apply to the assessed SDS [32,34]. As an example, the number of contributors or the number of edits of a certain feature can provide insights into its quality. Likewise, a saturation of the length of a road network may indicate that the representation of the network is near to complete [34,35,36,37]. These different ways of assessing the data for its quality are, however, not universal. The way people contribute depends strongly on the individual SDS, which is why the preceding examples do not apply in general but only to certain examples of SDSs. A characterization of SDSs by their underlying social principles and mechanisms as well as other aspects is needed to make sense of data quality in particular and ground the data in general.

The classification of SDSs by their underlying principles is very useful for examining an individual SDS. When setting the individual SDS into the context of other SDSs, similarities and differences can easily be recognized. Thereby, similarities among the underlying principles of different SDSs might suggest that the ways of how to make sense of and use the data are similar as well. For instance, data quality measures incorporating the lineage of the data, such as the saturation of the length of a road network, apply to a number of VGI data sources while the heterogeneity of AGI might hinder a meaningful interpretation in many cases. The classification of SDSs by underlying principles thus allows to understand how to make sense of an SDS in manifold ways.

3.2. Characterization of the Set of Shared Data Sources

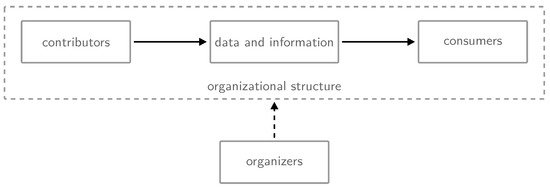

Shared Data Sources are manifold and multifaceted, which creates the need to characterize them by many different dimensions. The factors named before—the contributors, the consumers, the organizational structure, and so forth—can be used to characterize an SDS. Each of these factors, in turn, can be described by several dimensions. These dimensions characterize in detail how such SDSs mutually relate. As a result, each SDS can be placed in a conceptual space [38] that is spanned by the aforementioned dimensions.

Heterogeneity is a characteristic inherent to many SDSs. In some cases, it might even make sense to examine different parts of a data source independently although these parts belong to one project only—an SDS can be the result of several coexisting mechanisms that generate the data. Accordingly, an SDS usually occupies a region rather than a single point only in the conceptual space. Such regions often have a fuzzy boundary and potentially overlap with those of other SDSs.

The examination of the conceptual space of SDSs reveals not only characteristics of individual SDSs but, potentially, also characteristics of prototypes of SDSs. As an example, the size or shape of regions as well as their fuzziness might correlate to where the region of an SDS is located in the conceptual space. Moreover, some SDSs might cluster while others are evenly distributed in a region of the conceptual space. Instead of relating several SDSs in the conceptual space, also the change of an SDS over time can be traced, thereby relating the corresponding regions of the data source at different points in time. Such considerations may eventually lead to prototypes of SDSs as well as to prototypes of how SDSs can evolve.

6. Results

In the previous section, we discussed methods to visualize and statistically analyse a set of SDSs. Here, we report about the findings, i.e., what the visualizations and analyses can provide to the general understanding of SDSs, and of GSDSs in particular. In a first step, we discuss how the dimensions are related in case of GSDSs (Section 6.1). In a second step, the clustering of SDSs by their similarity to the prototypes is compared to the previously discussed categories (Section 6.2). Throughout the section, we maintain both a methodological focus as well as a focus on the entirety of GSDSs instead of individual ones. These results are both of independent interest as well as allow for an evaluation of the discussed framework.

6.1. Correlations Between the Dimensions

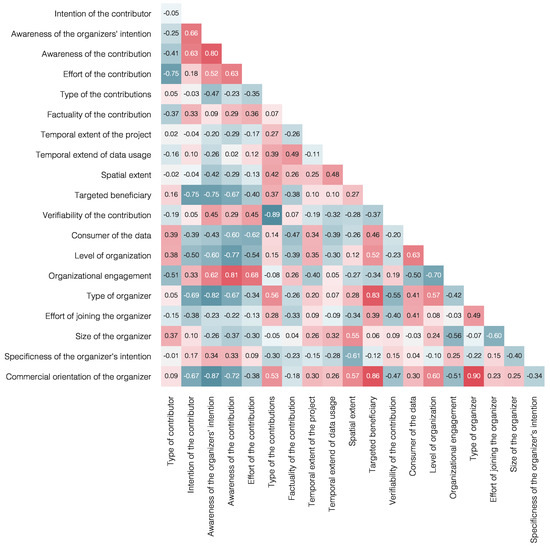

We have examined how the dimensions relate in case of the examined GSDSs. The correlation matrix of all dimensions mainly shows correlation coefficients of low to medium strength with only some pairs exhibiting a strong correlation (Figure 6). The Commercial orientation of the organizer is, e.g., negatively correlated both with the Intention of the contributor and the Awareness of the organizers’ intention—when someone contributes to an SDS with a commercial orientation, e.g., to typical AGI data sources like Twitter, the contributor often contributes without the intention of sharing the data for broader and more detailed analysis. Also, such contributors are often not aware of the intention of the organizer. This is in contrast to SDSs with a non-commercial orientation, to which volunteers often contribute knowingly, being aware for which purpose the data is collected. While providing a good overview over all correlations, the correlation matrix does not provide information about how exactly the dimensions relate for different SDSs.

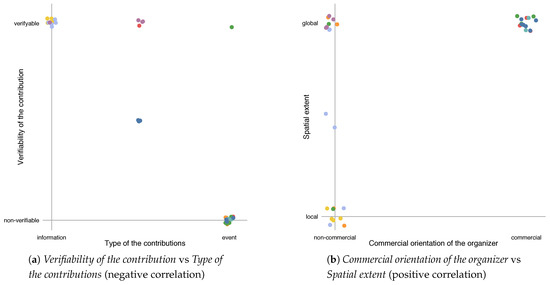

A more detailed comparison of the dimensions for individual GSDSs can be achieved by a scatter plot. In Figure 7, we display two strongly correlated pairs of dimensions. The Type of the contributions is negatively correlated to the Verifiability of the contribution (Figure 7a). General information is verifiable in case of the considered SDSs, information about events is less so. As events happen at some point in time and are, at least in parts, intangible thereafter, information about an event is hard to verify. The Commercial orientation of the organizer and the Spatial extent of an SDS are positively correlated (Figure 7b). Shared Data Sources with a commercial orientation are, in case of the examined GSDS, of global nature. A possible explanation might be that commercial companies aim to expand their projects to a global extent for maximizing their benefit. In contrast, SDSs with a non-profit orientation are, in parts, of local nature. Despite the fact that both pairs of dimensions depicted in Figure 7 expose a correlation—this fact can be seen in Figure 6—the scatter plots provide a better understanding of how they are related.

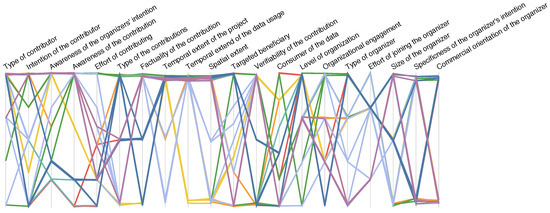

Similar specificities of the dimensions can be uncovered by using parallel coordinates. As can be seen in Figure 3, the values representing the characteristics of the GSDSs are not equally distributed for many dimensions. This applies, e.g., to the Temporal extent of the project and the Temporal extent of the data usage—most GSDSs are temporally unbounded and so is the use of the data collected in the project. The Awareness of the contribution is ‘polarizing’—there are only very few GSDSs for which the contributor is only to some degree aware of his or her contribution. Also, the positive and negative correlations that can be found in the correlation matrix are apparent in the parallel coordinates plot. However, in contrast to the correlation matrix, a dimension (represented by an axis) can only be compared to the ‘neighbouring’ ones in the plot, which is why the axes need to be reordered. Such a reordering is possible when the plot is interactively displayed.

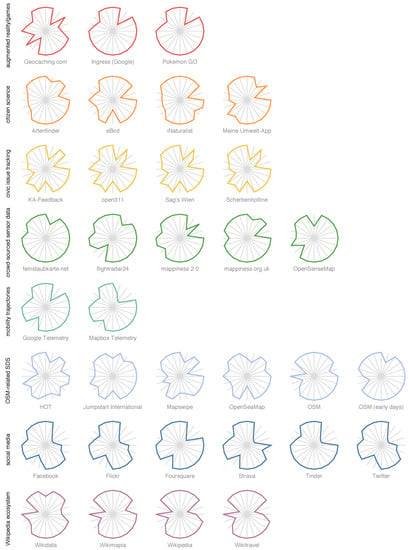

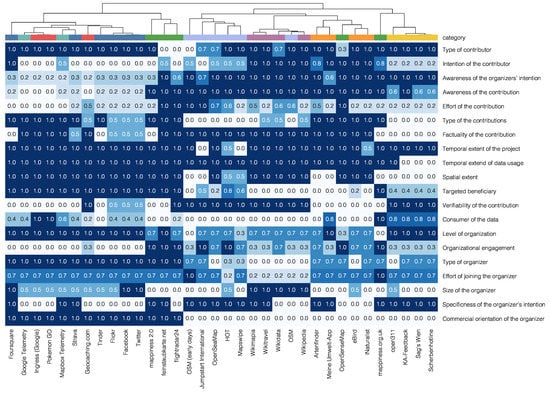

While we have so far considered correlations between the dimensions for all categories of GSDSs, additional significant correlations can occur within a single category. As an example, it becomes visible in Figure 5 that social media data sources expose very similar characteristics judged by the dimensions. This even applies to other categories. In addition, correlations among the dimensions can be found beyond the thematic categories, e.g., between crowd-sourced sensor data and mobility trajectories. The previously discussed figures could be restricted to SDSs from only one category as well. When examining SDSs by category, one gains not only information about the correlations within a category but also about how meaningful the categories are. In the next section, the prototypes and the categories are evaluated.

6.2. Clustering by Prototypes and Clustering into Categories

We have selected three prototypes—VGI, PGI, and AGI—which can be used for setting the GSDSs into context. In addition, we have grouped the GSDSs into thematic categories, which are broadly used and widely accepted. The techniques presented in Section 5 can aid in evaluating both the prototypes and the categories with respect to how well they can be explained in terms of the dimensions. In addition, it can be concluded how compatible the prototypes and the categories are—do the categories make sense in the context provided by the prototypes? And finally, one can use the discussed techniques for clustering SDSs into meaningful categories of differing granularity. In this section, we discuss the corresponding results.

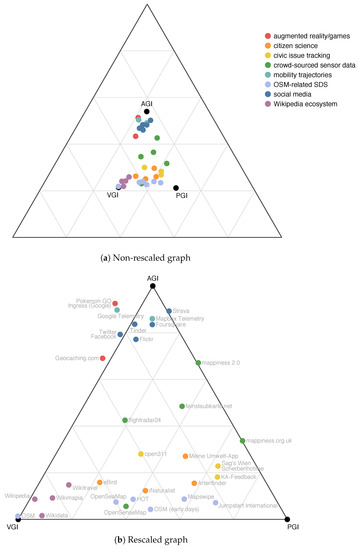

The spider charts in Figure 5 show that each thematic category contains GSDSs of similar characteristics, as has been discussed earlier. This demonstrates that the categories make sense in terms of the dimensions. In addition, differences between GSDSs within a category can easily be recognized and potential subcategories can be identified, e.g., in case of crowd-sourced sensor data. The spider charts can even be used to assign a new GSDS to one of these categories, because the differences between the categories are apparent for the most part. Also GSDSs are grouped thematically into categories in the trilinear graph, despite the fact that the dimensions are projected to two-dimensional space and much information is thus lost (Figure 2). As becomes apparent by the horizontal structure, the GSDSs of a thematic category can easily be recognized as being similar or dissimilar to the AGI prototype, while it is harder to distinguish between the VGI and the PGI prototype. While spider charts offer a more fine-grained representation in respect to the dimensions, the trilinear graph allows for easily tracing how an SDS develops over time. For instance, the graph reflects that OSM has changed from an SDS that shared about equal similarity to the VGI and PGI prototype (while exposing little similarity to the AGI prototype) to an SDS that is very similar to the VGI prototype—OSM was, in the first months, organized by a very restricted number of people, who focussed on their own interests, but changed then its organizational structure to become a major community-based project.

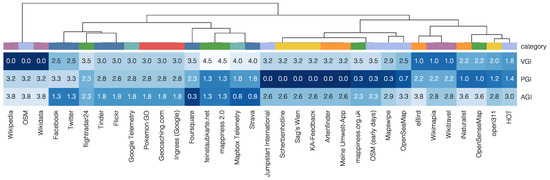

The statistical approach of hierarchical clustering allows for both a fine-grained as well as an automatized thematic grouping of the SDSs. In particular, the clustering based on the dimensions is, by and large, in accordance with the thematic categories (Figure 8). Only some SDSs fall into different groups such as OSM and OpenSenseMap. The categories mobility trajectories, social media, and augmented reality/games cannot be separated but form a distinct group. Within this group, the clustering and the thematic categories do not coincide. Figure 8 also demonstrates, like the other figures before, that the thematic categories make sense and are, to a high degree, compatible with the characterization by the dimensions.

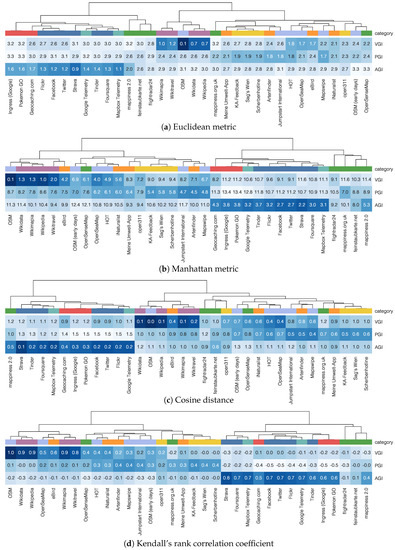

Figure 9 and corresponding considerations can reveal whether the similarity to the prototypes can be used for grouping the GSDSs in a meaningful way. We discussed before that the similarity between an SDS and a prototype can be measured in different ways, each of them having its own advantages and shortcomings. The four distance measures used in Figure 9 lead though to similar results for the considered GSDSs. Indeed, the distances between the SDSs and the prototypes are, by and large, independent of the used distance measure when considering the fact that they need to be rescaled before being compared. There exist, however, minor differences. The cosine distance and the Manhattan metric, e.g., indicate more clearly that Artenfinder, Mapswipe, and similar SDSs are similar to the PGI prototype. In contrast, Kendall’s rank correlation coefficient shows generally less similarity to the PGI prototype than other distance measures. As a result of these differences between the distance measures, the clustering depicted by the dendrogram differs slightly too. This similarity becomes more visible when the SDSs are horizontally reordered while maintaining the clusters. The Manhattan metric seems to produce best results in respect to how the categories are grouped together.

The statistical clustering demonstrates that the prototypes and the categories are reasonable in terms of their relation to the characteristics of the SDSs. In case of all four distance measures, four major clusters can be identified (Figure 9): one cluster of AGI-related and one cluster of VGI-related SDSs, as well as two further clusters. The two latter ones are less distinctive but expose most similarity to the PGI prototype, besides some similarity to the VGI prototype. In particular, the SDSs related to civic-issue tracking and crowed-sourced sensor data show a tendency towards the PGI prototype, which is mainly due to the dimensions describing the organizer, as can be seen in Figure 10. The categories of the SDSs can be reconstructed only by the similarity of the SDSs to the prototypes without making use of the categorization itself. The SDSs classified as crowed-sourced sensor data are grouped in case of some distance measures while being spread over several clusters in case of other ones. Also, the category of OSM-related SDSs spread over several clusters. This finding seems to be reasonable—OSM-related SDSs are, in fact, of very different nature—but demonstrates the limitations of the compatibility between the prototypes and the categories.

7. Conclusions

This article aims to provide a lens on new and collaborative forms of geographical data sources. We have introduced and coined the notions of ‘Shared Data Sources’ (SDS), ‘Geographical Shared Data Sources’ (GSDS), and ‘Participatory Geographic Information’ (PGI). Thereby, we have discussed the need for a conceptual framework for describing SDSs, which derives from incorporating dimensions to characterize different types of SDSs. A number of dimensions for conceptualizing SDSs have been introduced, among them dimensions related to the contributors, the data and information, consumers, the organizational structure, and the organizers. Finally, we have introduced tools and instruments to examine SDSs in their entirety, leading to different lenses through which we can learn about and make sense of such data sources.

The provided tools—visualizations and statistical analysis—allow for an examination of a set of SDSs in its entirety but an examination of differences and similarities within VGI, PGI, AGI, and similar prototypes would be of interest for future research. Categories of SDSs similar to AGI can easily be distinguished from those dissimilar to AGI. It seems, though, to be much harder to distinguish between VGI and PGI-related SDSs in the same way. Future research might focus on how SDSs can be distinguished better in terms of these prototypes and what hinders us from doing so at the moment. In particular, it may be discussed why the categories, prototypes, and characteristics discussed in this article are compatible and which limitations exist for this compatibility.

A number of dimensions have been introduced to characterize SDSs. Given some desired characteristics, can these dimensions be used to construct new forms of SDSs? For instance, can we derive from the desired characteristics of which nature the social process creating, maintaining, and using the data should be? If not, which characteristics contradict and hinder us from such a construction? The reasons behind these contradictions may even provide clues about further correlations and characteristics of SDSs. Also, one may ask which parts of the conceptual space remain yet ‘unused’ and would thus give rise to new types of SDSs.

When analysing SDSs and making sense of them in their entirety, data about the SDSs are needed, in particular, data about the contributions and the resulting data, about the consumers of the data, and about the roles of the organizers. The data used in this article have been collected by ourselves, which poses limitations to their interpretation and creates biases. Future research might explore how these limitations and biases can be characterized and how they can be avoided. In particular, the views of organizers, contributors, and users could be incorporated, which would create different biases. Also, it would be interesting to examine how such biases influence the resulting analysis. Such research would ideally build upon the methodology of the social sciences, requiring very different perspectives than the one used in this article.

Some SDSs are too heterogeneous to be described in a meaningful way, or too broad to be properly demarcated from one another. Among these examples is the Internet, which is very diverse and heterogeneous in its nature. Another example are Linked Open Data, which form, by definition, a web of statements. These statements are created by various people and organizations, and they share common vocabularies. These common vocabularies and semantics make possible to mutually relate the statements, leading (more or less) to only one big and heterogeneous data source. Future research might explore how such heterogeneous and broad SDSs can be conceptualized and incorporated into the analysis.

The discussed characterizations allow for making sense of SDSs. Further research might discuss structural differences between GSDSs in the geographical domain and SDSs in general. Also, the characterization by the ‘Triangle of Shared Data Sources’ allows for an examination of the temporal development of an individual SDS. Having examined several such trajectories, one might conclude how types and prototypes like VGI, PGI, and AGI evolve over time and, in addition, how our categorization into categories such as augmented reality/games, citizen science, civic issue tracking, crowd-sourced sensor data, and social media reacts to this temporal evolution. Finally, such understanding might render possible to trace or even predict the future development of SDSs, or a prototype like VGI or AGI.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Franz-Benjamin Mocnik; methodology, Franz-Benjamin Mocnik and Christina Ludwig; software, Franz-Benjamin Mocnik and Christina Ludwig; validation, Franz-Benjamin Mocnik, Christina Ludwig, A. Yair Grinberger, Clemens Jacobs, Carolin Klonner, and Martin Raifer; formal analysis, Franz-Benjamin Mocnik and Christina Ludwig; investigation, Franz-Benjamin Mocnik and Christina Ludwig; resources, Martin Raifer; data curation, Clemens Jacobs, Carolin Klonner, and A. Yair Grinberger; writing—original draft preparation, Franz-Benjamin Mocnik and Christina Ludwig; writing—review and editing, Franz-Benjamin Mocnik and Christina Ludwig; visualization, Franz-Benjamin Mocnik and Christina Ludwig; supervision, Franz-Benjamin Mocnik; project administration, Franz-Benjamin Mocnik.

Funding

Franz-Benjamin Mocnik has been funded by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft as part of the project A framework for measuring the fitness for purpose of OpenStreetMap data based on intrinsic quality indicators (FA 1189/3-1); Christina Ludwig and Martin Raifer, by the Klaus Tschira Stiftung; Carolin Klonner, by the Heidelberg Academy of Sciences and Humanities; and A. Yair Grinberger, by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation. The publication has financially been supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft within the funding programme Open Access Publishing, by the Baden-Württemberg Ministry of Science, Research and the Arts, and by Heidelberg University.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude for the valuable comments received by Alexander Zipf.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SDS | Shared Data Source |

| GSDS | Geographical Shared Data Source |

| VGI | Volunteered Geographic Information |

| AGI | Ambient Geographic Information |

| PGI | Participatory Geographic Information |

References

- Mocnik, F.-B.; Zipf, A.; Raifer, M. The OpenStreetMap folksonomy and its evolution. Geo-Spatial Inf. Sci. 2017, 20, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Participative Web: User-Created Content. 2007. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/sti/38393115.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2019).

- See, L.; Mooney, P.; Foody, G.M.; Bastin, L.; Comber, A.; Estima, J.; Fritz, S.; Kerle, N.; Jiang, B.; Laakso, M.; et al. Crowdsourcing, citizen science or volunteered geographic information? The current state of crowdsourced geographic information. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2016, 5, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwood, S.; Goodchild, M.F.; Sui, D.Z. Researching volunteered geographic information: Spatial data, geographic research, and new social practice. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2012, 102, 571–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocnik, F.-B. The polynomial volume law of complex networks in the context of local and global optimization. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mocnik, F.-B.; Frank, A.U. Modelling spatial structures. In Proceedings of the 12th Conference on Spatial Information Theory (COSIT), Santa Fe, NM, USA, 12–16 October 2015; pp. 44–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocnik, F.-B. A Scale-Invariant Spatial Graph Model. Ph.D. Thesis, Vienna University of Technology, Vienna, Austria, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Goodchild, M.F. Citizens as sensors: The world of volunteered geography. GeoJournal 2007, 69, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanidis, A.; Crooks, A.; Radzikowski, J. Harvesting ambient geospatial information from social media feeds. GeoJournal 2013, 78, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beard, K.; Egenhofer, M.J.; Lopez, X.; Onsrud, H.; Schroeder, P. Public participation GIS, Workshop. Available online: http://www.commoncoordinates.com/ppgis/ppgishom.html (accessed on 10 October 2018).

- Harvey, F. To volunteer or to contribute locational information? Towards truth in labeling for crowdsourced geographic information. In Crowdsourcing Geographic Knowledge: Volunteered Geographic Information (VGI) in Theory and Practice; Sui, D.Z., Elwood, S., Goodchild, M.F., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- Saxton, G.D.; Oh, O.; Kishore, R. Rules of crowdsourcing: Models, issues, and systems of control. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2013, 30, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyratos, S.; Lutz, M.; Pantisano, F. Characteristics of citizen-contributed geographic information. In Proceedings of the 17th AGILE Conference on Geographic Information Science, Castellón, Spain, 3–6 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Comber, A.; Schade, S.; See, L.; Mooney, P.; Foody, G.M. Semantic analysis of citizen sensing, crowdsourcing and VGI. In Proceedings of the 17th AGILE Conference on Geographic Information Science, Castellón, Spain, 3–6 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bishr, M.; Kuhn, W. Geospatial information bottom-up: A matter of trust and semantics. In Proceedings of the 10th AGILE Conference on Geographic Information Science, Aalborg, Denmark, 8–11 May 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heipke, C. Crowdsourcing geospatial data. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2010, 65, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLyser, D.; Sui, D.Z. Crossing the qualitative-quantitative divide II: Inventive approaches to big data, mobile methods, and rhythmanalysis. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2012, 37, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLyser, D.; Sui, D.Z. Crossing the qualitative-quantitative chasm III: Enduring methods, open geography, participatory research, and the fourth paradigm. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2014, 38, 294–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodchild, M.F.; Li, L. Assuring the quality of volunteered geographic information. Spat. Stat. 2012, 1, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordogna, G.; Frigerio, L.; Kliment, T.; Brivio, P.A.; Hossard, L.; Manfron, G.; Sterlacchini, S. “Contextualized VGI” creation and management to cope with uncertainty and imprecision. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2016, 5, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, D.Z.; DeLyser, D. Crossing the qualitative-quantitative chasm I: Hybrid geographies, the spatial turn, and volunteered geographic information (VGI). Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2012, 36, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, J.; Estrin, D.; Hansen, M.; Ramanathan, N.; Reddy, S.; Srivastava, M.B. Participatory sensing. In Proceedings of the 1st Workshop on World-Sensor-Web: Mobile Device Centric Sensory Networks and Applications (WSW), Boulder, CO, USA, 31 October 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Quesnot, T. L’involution géographique: Des données géosociales aux algorithmes. Netw. Commun. Stud. 2016, 30, 281–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieber, R. Public participation geographic information systems: A literature review and framework. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2006, 96, 491–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, C.C.; Hilchey, K.G. A review of citizen science and community-based environmental monitoring: Issues and opportunities. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2011, 176, 273–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haklay, M. Citizen science and volunteered geographic information: Overview and typology of participation. In Crowdsourcing Geographic Knowledge: Volunteered Geographic Information (VGI) in Theory and Practice; Sui, D.Z., Elwood, S., Goodchild, M.F., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 105–122. [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins, A.; Newman, G.; Stevenson, R.D.; Crowston, K. Mechanisms for data quality and validation in citizen science. In Proceedings of the 7th IEEE International Conference on e-Science Workshops, Stockholm, Sweden, 5–8 December 2011; pp. 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggins, A.; Crowston, K. From conservation to crowdsourcing: A typology of citizen science. In Proceedings of the 44th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Kauai, HI, USA, 4–7 January 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggins, A.; Crowston, K. Goals and tasks: Two typologies of citizen science projects. In Proceedings of the 45th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Maui, HI, USA, 4–7 January 2012; pp. 3426–3435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Kyttä, M. Key issues and research priorities for public participation GIS (PPGIS): A synthesis based on empirical research. Appl. Geogr. 2014, 46, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheider, S. Grounding Geographic Information in Perceptual Operations; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mocnik, F.-B.; Mobasheri, A.; Griesbaum, L.; Eckle, M.; Jacobs, C.; Klonner, C. A grounding-based ontology of data quality measures. J. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2018, 16, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haklay, M. How good is volunteered geographical information? A comparative study of OpenStreetMap and Ordnance Survey datasets. Environ. Plan. B 2010, 37, 682–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, C.; Neis, P.; Zipf, A. A comprehensive framework for intrinsic OpenStreetMap quality analysis. Trans. GIS 2014, 18, 877–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neis, P.; Zielstra, D.; Zipf, A. The street network evolution of crowdsourced maps: OpenStreetMap in Germany 2007–2011. Future Internet 2012, 4, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehrl, K.; Gröchenig, S. A framework for data-centric analysis of mapping activity in the context of volunteered geographic information. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2016, 5, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrington-Leigh, C.; Millard-Ball, A. The world’s user-generated road map is more than 80% complete. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gärdenfors, P. Conceptual Spaces. The Geometry of Thought; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mooney, P.; Corcoran, P. How social is OpenStreetMap? In Proceedings of the 15th AGILE Conference on Geographic Information Science, Avignon, France, 24–27 April 2012; pp. 282–287. [Google Scholar]

- Trant, J. Studying social tagging and folksonomy: A review and framework. J. Digit. Inf. 2009, 10, 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bégin, D.; Devillers, R.; Roche, S. Assessing volunteered geographic information (VGI) quality based on contributors’ mapping behaviours. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2013, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogliaroni, P.; D’Antonio, F.; Clementini, E. Data trustworthiness and user reputation as indicators of VGI quality. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2018, 21, 213–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keßler, C.; de Groot, R.T.A. Trust as a proxy measure for the quality of volunteered geographic information in the case of OpenStreetMap. In Proceedings of the 16th AGILE Conference on Geographic Information Science, Leuven, Belgium, 14–17 May 2013; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R.L. Information Graphics. A Comprehensive Illustrated Reference; Management Graphics: Atlanta, GA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Wegman, E.J. Hyperdimensional data analysis using parallel coordinates. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1990, 85, 664–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croux, C.; Dehon, C. Influence functions of the Spearman and Kendall correlation measures. Stat. Methods Appl. 2010, 19, 497–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokal, R.R.; Michener, C.D. A statistical method for evaluating systematic relationships. Univ. Kans. Sci. Bull. 1958, 38, 1409–1438. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Restricting geographical data to smaller areas does not provide the same possibilities of analysis because geospatial datasets expose particular characteristics at different scales [5,6,7]. As a result, it is in many cases a necessity that geographical datasets are of global nature. |

| 2 | A set of SDSs with similar characteristics could be named a category. As these sets, however, overlap, we refer to them as types. |

| 3 | Participatory Geographic Information (PGI) is a variant of PPGIS, which will be introduced later. |

| 4 | Please note that the prototypes VGI and AGI are named in the same way as the types described before. In the reminder of this article, we use these terms to solely refer to the prototypes if not stated differently. |

| 5 | Our notion of ‘PGI’ should not be confused with the one used by Spyratos et al. [13], which refers to ‘Professional Geographic Information’. |

| 6 | Kendall’s rank correlation coefficient is in many cases also referred to as ‘Kendall’s tau coefficient,’ or ‘Kendall’s tau’ in short. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).