1. Introduction

Origin–Destination (OD) flow prediction forms a cornerstone of intelligent transportation research, aiming to uncover the spatiotemporal dynamics of urban mobility between different origin–destination pairs. By leveraging historical records and multi-source contextual data, OD prediction elucidates the distribution and evolution of travel demand, offering valuable insights for traffic management, resource allocation, and urban planning. With the increasing complexity of modern transportation systems, travel behaviors have become highly nonlinear, multi-scale, and temporally dynamic. Accurately modeling such intricate spatiotemporal patterns under data uncertainty and noise remains a central challenge to achieving reliable traffic forecasting. Notably, while diffusion models have demonstrated remarkable modeling potential across domains such as image generation [

1,

2,

3,

4], text synthesis [

5,

6,

7], speech processing [

8,

9], and video production [

10,

11,

12,

13], their application to spatiotemporal forecasting in traffic scenarios remains constrained. Specifically, existing approaches often struggle to simultaneously capture multi-scale traffic dynamics and complex spatial semantic dependencies, thereby limiting both prediction accuracy and model generalization capabilities.

At their core, diffusion models learn to reconstruct realistic data by progressively denoising random noise, effectively simulating the reverse diffusion process that maps noise to the underlying data distribution. Initially introduced in image generation, diffusion frameworks such as Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models(DDPM) [

14] and Stochastic Differential Equation-based (SDE-based) models [

15] have since evolved to handle multimodal data with improved theoretical consistency and flexibility. In time series modeling, TimeGrad [

16] enhances predictive capability through time-dependent diffusion structures, while ScoreGrad [

17] improves generative stability by refining score function estimation.

Diffusion-based approaches have also shown growing potential in complex temporal and multivariate domains. The Conditional Score-based Diffusion Imputation (CSDI) model [

18] incorporates conditional information to guide the denoising process, achieving high precision in imputation and generation tasks. The Discrete Spatial-Temporal Diffusion (DSPD) and Continuous Spatial-Temporal Diffusion (CSPD) frameworks [

19] further integrate spatiotemporal dependencies, enabling joint modeling across traffic, meteorological, and other multimodal systems. More recently, TimeDiff [

20] and TSDiff [

21] have introduced contextual conditioning to better characterize irregular temporal intervals and abrupt pattern changes, pushing the boundaries of diffusion modeling for complex, real-world temporal dynamics.

Although diffusion models have demonstrated remarkable generative capability in time-series modeling, two fundamental limitations remain.

First, the utilization of spatial semantic features is insufficient. Current research primarily focuses on modeling temporal dependencies or topological correlations. For example, ScoreGrad and TimeGrad improve predictive stability by introducing time-dependent diffusion processes, yet they largely rely on the numerical evolution of sequences while lacking explicit incorporation of urban semantic priors. In real-world transportation systems, however, different urban regions exhibit strong functional heterogeneity, where the spatial distribution of Points of Interest (POIs) implicitly reflects travel purposes and human activity patterns. Neglecting such semantic information prevents models from distinguishing regions that are structurally similar but functionally distinct. For instance, the OD flow dynamics between commercial and residential areas may appear similar at the data level but are driven by fundamentally different mechanisms. Consequently, purely temporal diffusion models tend to produce unrealistic flow correlations in such cases, thereby restricting their generalization capability in complex urban settings.

Second, the ability to model spatiotemporal interactions remains limited. Some extensions, such as CSDI and TSDiff, incorporate conditional information into the diffusion process to enhance temporal dependency modeling or contextual representation. Nevertheless, these methods usually employ static embedding fusion, making it difficult to dynamically capture interactions among spatiotemporal features during the denoising phase. For traffic flow tasks characterized by both periodic and sudden fluctuations, static conditioning cannot reflect temporal variations in semantic importance, resulting in coarse-grained denoising and delayed feature response. This limitation becomes particularly apparent during traffic surges, disruptions, or demand bursts in POI-dense areas. Therefore, there is an urgent need for a generative prediction framework capable of adaptively integrating multi-source semantic information and capturing fine-grained spatiotemporal correlations throughout the diffusion process.

To address these challenges, we propose a Cross-Attention Diffusion Model for short-term OD flow prediction. Built upon the generative diffusion framework, Cross-Attention Diffusion Model (CADM) introduces semantic conditioning by incorporating POI embeddings into the noise modeling process, enabling external knowledge–guided generation control. Specifically, the model takes noisy OD features and the diffusion time step t as primary inputs, while using POI embedding vectors as spatial semantic conditions. On this basis, a Cross-Attention Module is designed to achieve bidirectional fusion between semantic and spatiotemporal representations. In this mechanism, OD spatiotemporal features serve as queries (Q), and POI embeddings act as keys (K) and values (V). Through attention-based weighting, the model dynamically captures semantic relevance, allowing it to focus on semantically related regions at each diffusion step and thereby perform semantically guided noise prediction.

This design addresses two critical gaps in existing diffusion-based traffic forecasting. First, in terms of novelty, while conventional diffusion models treat spatial regions uniformly during denoising, CADM explicitly distinguishes functionally heterogeneous areas through POI-guided cross-attention, enabling the model to adaptively prioritize semantically relevant regions at each diffusion step. Unlike static semantic fusion approaches, the proposed mechanism dynamically modulates attention weights throughout the reverse process, allowing semantic guidance to evolve stage-by-stage in response to noise reduction. Second, regarding practical importance, this semantic-aware generation framework enhances both interpretability and spatial consistency—particularly in multifunctional urban zones where purely data-driven models often produce semantically inconsistent flows. By grounding traffic generation in urban functional context, CADM offers a more explainable and controllable forecasting tool for real-time traffic management and dynamic transportation planning.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 introduces the data preparation pipeline and presents the overall architecture of CADM, including the temporal encoding module, U-Net denoising network, cross-attention semantic fusion mechanism, and conditional diffusion generation process.

Section 3 reports comprehensive experimental results on real-world urban datasets, comparing CADM against 13 baseline methods and conducting ablation studies to validate the contribution of each component. Finally,

Section 4 discusses the findings, identifies current limitations, and outlines promising directions for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Preparation

In this study, a multi-source spatiotemporal dataset is constructed from real-world urban mobility data, where regional Origin–Destination flows and semantic representations of Points of Interest are utilized as key inputs for short-term traffic flow forecasting.

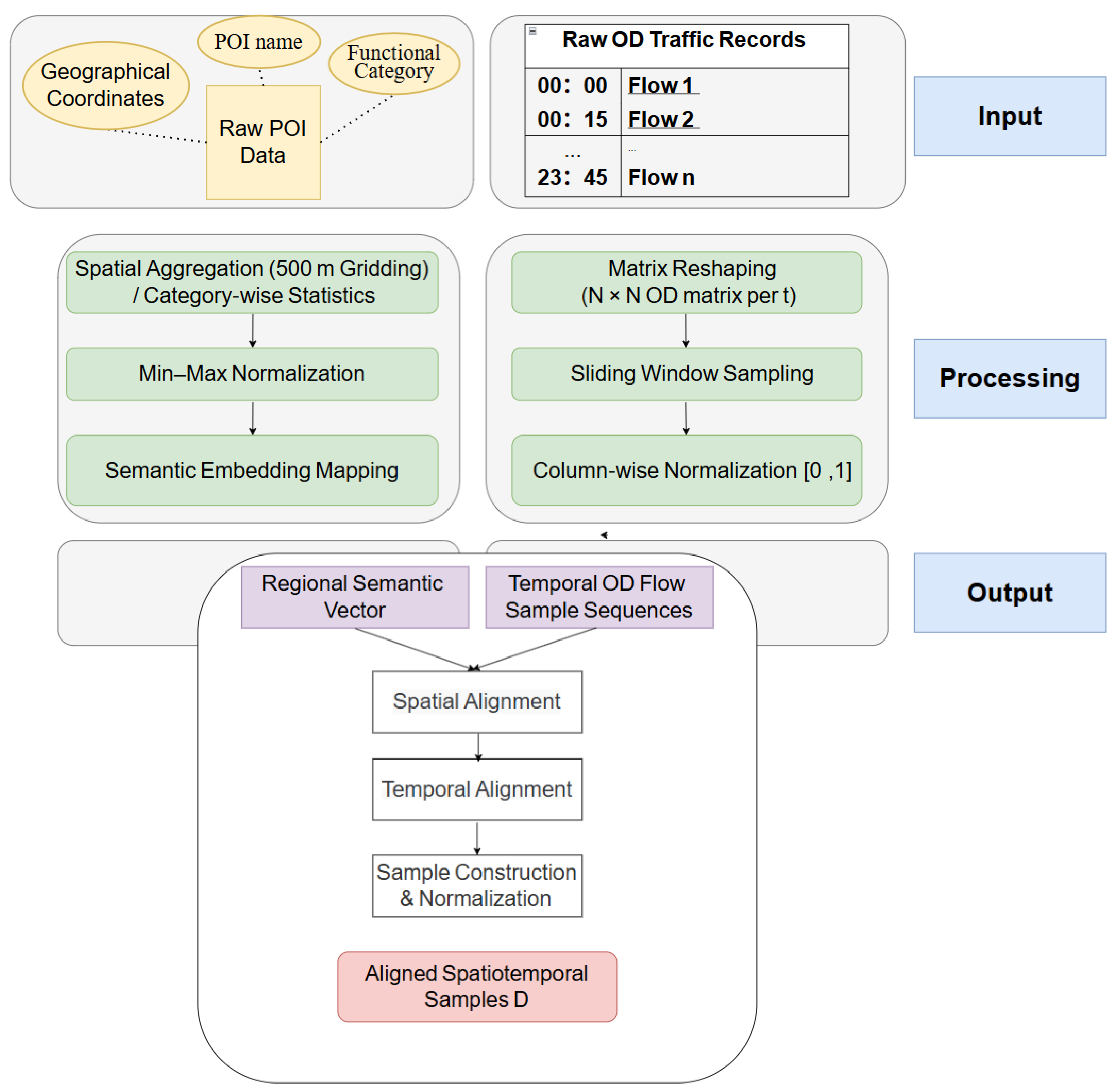

The data processing pipeline comprises three main stages—POI feature extraction, OD matrix construction, and multi-source sample generation—as depicted in

Figure 1.

2.1.1. POI Data and Semantic Feature Construction

The Point of Interest data utilized in this study are obtained from AMap’s internal geographic information database, which provides high spatial accuracy and rich semantic attributes. The dataset covers a broad spectrum of urban functional categories, including dining, commercial, educational, office, recreational, medical, and transportation hub facilities. Due to privacy protection regulations and data licensing requirements, the POI data are used exclusively for academic research and are not publicly distributed or shared. The original POI records include essential metadata such as unique identifiers, names, functional categories, geographic coordinates, and administrative divisions. A representative example is shown in

Table 1.

Each record contains static attributes including the longitude and latitude coordinates (location), functional category (type), and administrative division code (adcode) of the POI, which facilitate multi-level spatial aggregation and semantic analysis. To construct semantic feature vectors corresponding to traffic stations, this study utilizes POI data from Beijing. We designate the geographic center of each station as an aggregation unit and establish a spatial statistical radius of 500 m. Within each unit, the quantity of POIs across different functional categories is tallied to derive the functional distribution characteristics of the area:

Formally, represents the number of POIs belonging to the k-th functional category within the i-th station area, where k denotes the total number of POI categories.

All POI features are first normalized using min–max scaling to mitigate magnitude inconsistencies across categories and subsequently projected into a low-dimensional representation space via a semantic embedding layer. This process establishes a mapping from raw point-of-interest data to regional semantic embeddings, enabling the model to effectively discern urban functional heterogeneity and spatial semantic dependencies in the following stages, thereby reinforcing the interpretability and robustness of short-term traffic forecasting.

2.1.2. OD Data and Flow Matrix Construction

The Origin-Destination flow data utilized in this study is also derived from the internal geographic information database of Amap. This dataset records the travel intensity between spatial grids in Beijing within discrete time slices over the past year, incorporating environmental context such as holiday indicators and traffic control statuses. Following aggregation and cleaning, the data is structured into a flow matrix in a time-series format with a temporal resolution of 15 min.

Specifically, each row in the matrix represents a time slot t (e.g., 1 January 2024 00:00–00:15), and each column corresponds to an ordered OD pair (

,

), indicating the outbound flow from origin grid

to destination grid

.The matrix element

(

,

) signifies the traffic flow volume between the paired grids within the given time interval. A representative example is shown in

Table 2.

In this formulation, each “origin–destination grid pair” explicitly represents the indices of departure and arrival regions. The temporal dimension extends across the entire observation horizon, forming a multidimensional spatiotemporal series that integrates a fixed spatial layout with continuous temporal dynamics.

For each time interval t, the traffic flows are represented by an N × N OD matrix

, where N denotes the total number of spatial grids. This matrix characterizes the overall spatial distribution of mobility flows and inter-regional interactions, with missing entries replaced by zeros. To capture temporal dependencies, a sliding window framework is adopted to construct time-series samples: 12 consecutive intervals (approximately 3 h) are used as historical inputs, and the subsequent 4 intervals (around 1 h) are used for prediction. Formally, the temporal window is defined as

, and the sample construction process is illustrated as follows:

Here, denotes the temporal dependency feature set fed into the model, and represents the subsequent four time steps used as prediction targets.

To ensure numerical stability and comparability across OD pairs, all flow values are normalized to the [0, 1] interval. The processed dataset is then partitioned into training, validation, and testing subsets following a consistent ratio, providing standardized input for subsequent spatiotemporal modeling.

2.1.3. Data Alignment and Sample Generation

After deriving the POI-based semantic representations and constructing the OD flow matrices, multi-source data are aligned across spatial and temporal dimensions to guarantee feature synchronization for model training. The aligned data are then organized into spatiotemporal sample sets that can be directly fed into the predictive framework.

This study employs a unified grid-based spatial framework as the common reference system, ensuring that POI features and OD flows share identical spatial indexing structures. Specifically, each origin and destination grid within the OD matrix is associated with unique POI feature vectors and , respectively.

All POI feature embeddings are projected into a shared semantic space to capture latent similarities and inter-regional interactions among urban functional zones, thereby complementing the spatial semantics underlying OD flows.

The OD flow series is uniformly sampled at 15 min intervals. To guarantee temporal synchronization among multi-source datasets, all records are aligned along a unified time axis and resampled when necessary. Missing or irregular entries are smoothed or interpolated to ensure structural completeness. After alignment, each time slice yields a paired input consisting of the flow matrix and its corresponding set of semantic vectors {}.

A sliding-window framework is employed to construct training samples. Each sample comprises 12 historical OD flow matrices and their associated POI semantic representations, used to predict the subsequent 4 time steps of flows:

Here, captures short-term temporal dependencies, while encodes spatial semantic conditions.

All features are normalized via the min–max approach to eliminate scale inconsistencies. The final dataset is partitioned into training, validation, and testing sets with a ratio of 8:1:1, yielding the aligned multi-source spatiotemporal samples:

Through this layered spatial–temporal alignment and sample construction process, the dataset effectively preserves the dynamic continuity of OD flows and the spatial diversity of POI semantics, providing a rigorous empirical foundation for forecasting urban mobility under complex environmental conditions.

2.2. Overall Framework of CADM

To enable high-precision forecasting of short-term urban traffic dynamics, this study proposes a Cross-Attention Diffusion Model—a multi-source spatiotemporal framework grounded in the diffusion-based generative paradigm.

Within the Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Model framework, CADM jointly models the dynamic temporal dependencies of OD flows and the spatial heterogeneity embedded in POI semantic representations. By leveraging a structured noise-to-data reconstruction process—encompassing noise injection, denoising, and matrix reconstruction—the model synthesizes future traffic flow distributions. An overview of the framework is provided in

Figure 2.

2.2.1. Model Inputs and Outputs

At each diffusion timestep, CADM integrates heterogeneous spatiotemporal signals through three complementary sources:

Noisy OD Matrix (): Obtained by injecting Gaussian noise into historical OD flows during the forward diffusion process, capturing the uncertainty of the current mobility state.

POI Semantic Embedding (

): Drawn from the multi-dimensional semantic representation introduced in

Section 2.1.1, providing spatial-functional priors for diffusion learning.

Temporal Embedding (): Generated by a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) to encode the diffusion-step index into a continuous latent manifold, enriching temporal awareness of the model.

The model outputs a predicted noise field that approximates the actual noise ϵ. During inference, the reverse diffusion process progressively denoises to reconstruct the clean OD matrix , representing the predicted traffic flows for forthcoming time slots.

2.2.2. Model Architecture and Computational Flow

The computation pipeline of CADM comprises five core modules:

Input Encoding: Fuse , and into unified latent representations serving as model inputs.

Temporal Embedding: Inject timestep semantics through nonlinear MLP transformations.

U-Net Denoising Network: Leverage multi-scale convolutions and residual connections to extract hierarchical OD spatiotemporal features.

Cross-Attention Fusion: Utilize OD features as queries (Q) and POI embeddings as keys (K) and values (V) to enable self-adaptive alignment between semantic and flow domains.

Noise Prediction and Reconstruction: Predict the noise and iteratively reconstruct through reverse diffusion.

Formally, the forward pass can be expressed as:

where

is the parameterized denoising network and

represents the generative process implementing reverse diffusion.

2.3. Temporal Step Encoding and U-Net Denoising Network

This section elaborates on the core denoising module of the proposed CADM framework, whose objective is to accurately estimate the latent noise

and reconstruct the probabilistic distribution of traffic flow features, conditioned on the noisy OD matrix

and POI embeddings

. The denoising backbone consists of two tightly coupled components:a temporal-embedding block that explicitly encodes diffusion-step information to preserve temporal coherence across iterations, and a U-Net-based denoising network capable of multi-scale convolutional processing and spatial reconstruction. Through their joint operation, CADM achieves consistent denoising capability across diffusion stages while preserving fine-grained structural realism in the reconstructed traffic flows. The overall network architecture is illustrated in

Figure 3.

2.3.1. Overall Design Philosophy

Within the diffusion generation framework, each diffusion and reverse-sampling step corresponds to the noise intensity and re-weighting stage during the forward and backward processes. The explicit modeling of such temporal information allows the network to perceive the magnitude and stage sensitivity of noise across diffusion timesteps, thereby enhancing denoising adaptability. To achieve this, CADM introduces a temporal embedding module based on a multi-layer perceptron. This module maps discrete timesteps into continuous high-dimensional representations, providing the model with sequential temporal awareness throughout the diffusion process.

Specifically, given the timestep

, the fixed sinusoidal function is used to generate periodic positional mappings so that each diffusion step can be continuously represented as

Here,

denotes the frequency component used to capture the periodic variation in diffusion time. The resulting temporal encoding γ(t) is transformed by two fully connected layers to obtain a smooth nonlinear representation:

where ϕ(.) is the ReLU activation. This block projects the discrete timestep into a visible semantic transition space, enabling the network to learn continuous representations from fixed indices and thus making the diffusion phase controllable and temporally coherent. The encoded

is forwarded to the feature pathway through residual layers for progressive propagation, allowing different diffusion stages to adaptively express varying noise states and achieve smooth transitions across reverse diffusion steps.

2.3.2. Hierarchical U-Net Architecture

After obtaining the temporal embedding, CADM employs an improved U-Net architecture to reconstruct multi-scale features of the noisy OD matrix. Unlike standard image U-Nets, this framework is tailored for the OD matrix and introduces lightweight regional processing and attention mechanisms to enhance stability and model convergence.

The encoder is composed of three one-dimensional convolutional layers (Conv1D × 3), each followed by batch normalization (BN) and ReLU activation to capture inter-layer spatiotemporal variations:

Here, a Conv1D architecture is adopted instead of the traditional Conv2D. This design choice is predicated on the organizational structure of the model’s input features: during the diffusion phase, the OD matrices are encoded and flattened into sequences of regional travel vectors. Conv1D is employed to extract feature representations along the temporal and semantic channel dimensions, while spatial dependencies are subsequently captured via the Cross-Attention Semantic Fusion (CASF) mechanism.

The adoption of Conv1D offers two primary advantages. First, it significantly reduces parameter count and computational complexity while maintaining temporal consistency, thereby preventing the interference caused by noise propagation during the diffusion inversion process that often accompanies the dimensional expansion in Conv2D. Second, since the primary role of the U-Net at this stage is multi-scale feature reconstruction and decoding rather than direct modeling of spatial neighborhoods, Conv1D processes high-dimensional sequential signals more efficiently, providing a more stable feature flow for conditional diffusion generation.

Shallow convolutions extract short-term spatiotemporal dependencies, while deeper residual blocks further compress and abstract high-level representations. To enhance hierarchical learning, a residual block (ResBlock × 2) is applied as follows:

This design maintains information flow along short connections, accelerates gradient propagation, and strengthens multi-level feature transmission. The encoded representation thus carries comprehensive high-level features for subsequent reconstruction.

In the decoding stage, transposed convolution (Transposed Conv1D) layers are used for upsampling and feature restoration. Each decoder stage symmetrically corresponds to its matching encoder layer through skip connections to preserve spatial detail and ensure feature complementarity. Finally, a Conv1D layer outputs the denoised result , representing the predicted noise field aligned with the OD dimensions. Through the cooperation of temporal embedding and hierarchical U-Net structure, CADM achieves consistent denoising capability across different diffusion steps while maintaining structural smoothness and reconstruction fidelity.

2.3.3. Skip-Connection Mechanism

To mitigate information loss during downsampling, CADM integrates skip connections between symmetric encoder and decoder layers.

Among them, represents the output of the encoder layer, while refers to the feature map of the decoder layer. The concatenation operation ensures that the positional information from lower layers and the semantic features from higher layers are fully fused during the decoding stage, enabling the network to reconstruct the OD matrix with both fine-grained integrity and global consistency.

In addition, the skip-connection structure provides a direct path for gradient propagation, significantly alleviating the instability issues that frequently occur during the training of deep networks.

2.4. Cross-Attention Semantic Fusion Module

To enhance the model’s capacity for urban semantic interpretation and spatial-structural perception during the generative process, CADM introduces a Cross-Attention Semantic Fusion mechanism into the bottleneck layer of the U-Net backbone. This mechanism incorporates external POI feature embeddings to realize dynamic alignment and interactive learning between heterogeneous modal features, thereby establishing an explicit correspondence between flow dynamics and geographic semantic information. Within the diffusion generation framework, relying solely on the spatiotemporal characteristics of the OD flow matrix often fails to sufficiently represent regional functional features and behavioral semantic associations. On this basis, CASF introduces a learnable attention-weighting mechanism that enables the model to adaptively extract, from the structured POI embeddings, those features most semantically relevant to the current traffic state, thereby achieving complementary fusion between external semantic constraints and internal dynamic modeling.

In this mechanism, the query matrix Q is defined as the OD feature representation

output by the U-Net bottleneck, which characterizes spatiotemporal dependencies and traffic dynamics among regions. The key (K) and value (V) matrices are constructed from the POI embeddings

, that is, Q =

, K = V =

. This feature-pairing strategy maintains the continuity of OD dynamic features while introducing static environmental semantic constraints, allowing the model to capture the dual structural relationships of “traffic behavioral patterns” and “spatial functional semantics” within the feature space. The cross-attention operation follows the standard Scaled Dot-Product Attention formulation, and its computation is expressed as:

Here, d represents the scaling factor of the feature dimension, which is used to suppress excessively large dot-product results and mitigate gradient instability. The similarity matrix Q measures the correlation strength between traffic features and POI semantics, and after softmax normalization, forms the attention-weight matrix A. By performing the weighted aggregation AV of POI semantic features, the fused features are obtained. This process essentially realizes the semantic modulation of traffic features across different regions, allowing the model to emphasize pattern correlations among functionally similar or spatially adjacent areas during generation, thereby improving semantic consistency and spatial interpretability.

CASF is embedded in the bottleneck layer of the U-Net architecture with clear design motivation and theoretical basis. At this stage, the OD features , after multiple convolution and downsampling operations, already possess strong global abstraction capability but have not yet entered the upsampling reconstruction phase; therefore, this serves as the optimal position for semantic injection. By introducing the cross-attention mechanism at this layer, the fused feature information can propagate upward along the decoding path, guiding semantic restoration in higher-level structures, while maintaining structural consistency with the lower-level features in the encoding path. The final generated representation simultaneously carries both high-level semantics and low-level spatial details, achieving a balance between local precision and global coherence during reconstruction, thus resolving the semantic discontinuities that may occur when relying solely on convolutional features.

From a mechanistic perspective, the primary objective of designing the Cross-Attention Semantic Fusion mechanism is to enhance the semantic perception and spatial modeling capabilities of CADM. On the one hand, the model leverages attention weights to identify semantic coupling relationships between regions characterized by similar functions, comparable land use, or related activity types, ensuring that the generated OD distributions adhere to the spatial logic inherent in the urban functional layout. On the other hand, the global weighting property of the attention mechanism imposes directional constraints on the diffusion denoising process, ensuring that the generated traffic feature distributions exhibit not only improved numerical stability but also greater fidelity in their spatial structure. Furthermore, CASF possesses high parallelism, allowing it to operate synchronously with the U-Net backbone convolutions; this design achieves semantic alignment and information reinforcement without significantly increasing the parameter count or computational overhead.

2.5. Conditional Diffusion Generation and Reconstruction

After the temporal-step encoding and semantic-fusion mechanisms jointly establish the multi-source representation space, CADMs and reconstructs the latent distribution of the noise-added OD matrix through a conditional diffusion generation process. This stage consists of two phases: the training phase and the inference phase. The former aims to learn a reverse noise-estimation function capable of reconstructing the latent true distribution from the noisy samples, while the latter performs step-by-step denoising inversion from random noise based on the learned parameters, ultimately generating a high-fidelity OD distribution.

This study adopts the Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Model framework as the theoretical foundation for diffusion modeling (

Figure 4). The core principle of this framework involves modeling the forward diffusion and reverse denoising processes of data via Markov chains. During the training phase, the diffusion process can be viewed as a continuous Markov chain that progressively injects Gaussian noise into the data over discrete time steps.

Starting from the original sample

, a sequence of latent variables {

is generated, where the forward diffusion process can be expressed as

where

represents Gaussian noise, and

denotes the cumulative product of noise coefficients across time steps. This process describes how sample features are gradually perturbed by noise at each time step, leading the sample distribution to transition smoothly toward an isotropic Gaussian distribution. To regulate the intensity of noise injection, this study employs a linear β schedule, where the noise level β

t increases linearly within the interval [0.0001, 0.02]. This specific scheduling strategy is selected because it strikes an effective balance between stationarity and abruptness in traffic flow data, thereby preventing early information loss caused by excessive noise accumulation. The core of model training lies in learning the reverse reconstruction process—specifically, parameterizing the conditional distribution of the backward denoising steps through a neural network

(

,t,

) so as to recover a clean sample from its noisy state. The reverse diffusion step can be expressed as:

where

is the variance of the sample noise, and

. The network learns the noise estimation function

to approximate the true posterior distribution p(

,

,

), thereby realizing conditional and stable denoising generation.

The training objective of the model is to minimize the mean-square error between the predicted noise and the true noise, ensuring precise learning of detailed variations at each diffusion step. The loss function is defined as

where t is uniformly sampled across time steps,

is the true Gaussian noise, and

=

(

, t,

) is the model-predicted noise. This objective seeks to minimize the expected error between predicted and true noise, guiding the network to learn a robust conditional denoising mapping associated with POI semantics, thereby enhancing its ability to reconstruct regionally and temporally variant features from noisy conditions.

During the inference phase, the model begins by sampling from a standard Gaussian distribution, and then iteratively performs the reverse diffusion process to progressively generate . In each step, the model sequentially removes noise from the latent representation while integrating semantic constraints, thereby achieving layer-by-layer conditional denoising reconstruction. As time steps decrease, the denoised samples gradually evolve into the structurally coherent OD matrices. In the early stages, the model focuses on restoring coarse spatiotemporal patterns of regional mobility and traffic intensity; in the later stages, it converges toward geometry-aware local refinement, capturing relational consistency among semantically or spatially correlated regions.

In summary, CADM leverages time-step diffusion modeling to conceptualize noise injection as dynamic perturbations to traffic system states and reconstructs spatiotemporal structure through reverse denoising. To integrate multi-source information, the model employs cross-modal attention to project POI semantics and OD flow dynamics into a unified representation space, enabling collaborative enhancement that strengthens semantic adaptability and spatial consistency across functionally heterogeneous regions. Architecturally, CADM adopts a U-Net-based symmetric generation network with cross-layer attention mappings at multiple scales, jointly modeling global trends and local details. This design preserves diffusion reversibility while providing flexibility to incorporate multi-source spatiotemporal features and generalize across diverse scenarios. Consequently, CADM integrates semantic, temporal, and spatial information within a unified probabilistic generative framework, establishing a stable, controllable, and structurally adaptive traffic flow generation system. The following section presents comprehensive experimental evaluations on real-world urban datasets to validate the model’s effectiveness and generalization capability in spatiotemporal forecasting.

3. Experimental Evaluation and Ablation Study

3.1. Datasets

In this study, a high-precision multi-source spatiotemporal dataset was constructed based on the internal geographic information database of Amap (Gaode Map) to verify the effectiveness of the proposed Cross-Attention Diffusion Model in short-term urban OD traffic flow prediction tasks. The dataset covers the core functional areas and major road grids of Beijing, with a spatial resolution of 500 m as the basic unit, resulting in N spatial regions. At each time step, a corresponding N × N OD flow matrix is generated. The observation period spans from January to June 2024, with a temporal resolution of 15 min, forming more than 15,000 continuous time slices, which comprehensively reflect the dynamic evolution characteristics of urban traffic. In addition to traffic flow data, multiple environmental factors closely related to travel behavior are also collected, including temperature, precipitation, holiday indicators, and traffic control information, to support modeling and generation under multi-source conditions.

Compared with commonly used public traffic datasets (such as PEMS-Bay), the internal Amap dataset employed in this study exhibits higher complexity and realism in both spatial resolution and semantic dimensionality, enabling a more detailed characterization of multi-scale dynamics in complex urban mobility. The POI (Point of Interest) data encompass typical functional categories such as dining, commerce, office, and transportation hubs. For each spatial grid, the semantic distribution is obtained by counting the number of POIs across different categories. To ensure feature stability and comparability in scale, all POI features are normalized using the min–max method and further mapped into a low-dimensional continuous space through a semantic embedding layer, forming structured regional semantic vectors. This allows the model to simultaneously perceive variations in urban functional roles and latent travel patterns during the generation process.

For temporal modeling, all OD flow matrices are column-wise normalized and organized into sequential samples via a sliding-window mechanism, in which the observations of 12 consecutive time steps (approximately 3 h) are used as input to predict the flow variation in the subsequent 4 time steps (approximately 1 h). Normalization is performed based on the statistical range of the training set to ensure numerical consistency between the training and inference phases. This dataset possesses high representativeness in terms of temporal coverage, spatial granularity, and multi-source semantic characteristics, providing sufficient and reliable support for the conditional diffusion learning of the CADM, and establishing a solid data foundation for subsequent experimental analysis.

3.2. Evaluation Metrics

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the CADM on short-term OD traffic flow prediction tasks, this study adopts multiple quantitative evaluation metrics to assess both the accuracy of point predictions and the consistency between predicted and empirical distributions. Specifically, three common error measures are employed—Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE)—to quantify the bias and robustness of model predictions from different perspectives. They are defined as follows:

where

is the observed ground truth,

is the model prediction, and n is the total number of samples. MAE reflects the average prediction deviation, while RMSE is more sensitive to large errors, effectively capturing the impact of extreme values. MAPE, in turn, measures relative errors, enabling intuitive cross-scale comparisons of model accuracy across heterogeneous regions. Together, these three indicators provide a multidimensional evaluation of both overall prediction accuracy and stability. In addition, to evaluate the probabilistic accuracy of the generative model, this study introduces the Continuous Ranked Probability Score (CRPS) as a comprehensive distributional metric. CRPS assesses how well the predicted distribution F aligns with the empirical observation Y, and is defined as:

where

denotes the cumulative distribution function of the i-th sample prediction, and

is an indicator function. This metric computes the integral distance between the predicted and empirical cumulative distributions. A smaller CRPS value indicates a closer agreement between the two distributions; thus, the lower the CRPS, the better the generative model’s ability to align its predictive distribution with reality, resulting in predictions that are statistically more trustworthy and interpretable.

3.3. Implementation Details

To comprehensively verify the performance of the proposed Cross-Attention Diffusion Model for short-term OD traffic flow prediction, a series of comparative experiments were conducted on the aforementioned multi-source spatiotemporal dataset. All experiments were implemented in Python 3.8, using the PyTorch 2.0 framework, and executed on a server equipped with an NVIDIA RTX 4080 GPU (16 GB memory).

The dataset was partitioned chronologically into 80% for training, 10% for validation, and 10% for testing. All input features (including OD flow matrices and POI embeddings) were normalized using the min–max method based on the statistical range of the training set, ensuring consistent scaling across different data splits.

The model was trained for 50 epochs with a batch size of 32. The Adam optimizer was employed with an initial learning rate of 1 × and a weight decay of 1 × . A cosine annealing scheduler was used to dynamically adjust the learning rate during training. The diffusion process was set to T = 100 steps, and the noise level was linearly increased within the range [0.0001, 0.02] following a linear schedule, which helps prevent numerical instability near t = N.

To prevent overfitting, a dropout rate of 0.2 was applied within the feature layers, and an early-stopping mechanism was incorporated. Training was terminated early if the validation RMSE did not improve over 10 consecutive epochs. RMSE was chosen as the stopping criterion because its squared-error structure is more sensitive to large deviations, allowing it to guide the optimization of deterministic prediction performance more effectively.

Since diffusion models are inherently stochastic, the same input may produce slight variations across different generations. To mitigate randomness and enhance robustness, each input sample was independently generated 10 times, and the mean prediction was reported as the final result. A fixed random seed was applied in all experiments to ensure reproducibility. This overall training and inference procedure achieves an effective balance among stability, accuracy, and computational efficiency.

Implemented on an NVIDIA 4080 GPU with 16 GB of VRAM, CADM requires approximately 25 min per training epoch. Complete training to convergence—typically 50 epochs with early stopping—takes roughly 21 h. The relatively high training cost of CADM primarily stems from the additional computational overhead associated with multi-step noise estimation during the diffusion process and cross-attention calculations. The model comprises 18.7 million parameters, with peak VRAM usage reaching 12.8 GB during training. In the inference phase, the prediction latency for a single sample (predicting 4 future time steps from 12 input time steps) is approximately 1.8 s. The memory requirement during inference is 6.5 GB, which is allocated mainly for storing intermediate diffusion states and attention weight matrices.

3.4. Baselines

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the proposed Cross-Attention Diffusion Model in short-term OD traffic flow prediction, a total of 13 representative traffic forecasting models were selected for systematic comparison. The baselines include:

Among these, (1) and (2) are traditional statistical learning models; (3)–(5) and (12)–(13) represent deep learning models for time-series forecasting; and (6)–(11) are spatiotemporal graph neural network (GNN) models. Except for STGIN, which is implemented on the TensorFlow platform, all other baselines are built under the PyTorch 2.0 framework.

To ensure fairness in comparison, all baseline models followed the same data preprocessing and partitioning protocol as CADM. All methods except traditional baselines applied the same min-max normalization scheme. For models incorporating spatial topology (Baselines (6)–(10)), traffic-environmental features were embedded as multi-channel node attributes to enhance spatiotemporal representation, whereas STGIN, with its built-in adaptive embedding structure, required no additional feature-channel integration.

Hyperparameter configurations were initialized based on the settings reported in the original papers and official implementations, and further optimized via grid search. Each model was trained for up to 100 epochs with a batch size of 32, using an early-stopping condition that halted training if the validation RMSE did not improve for 10 consecutive epochs. This consistent experimental design ensures methodological rigor and reproducibility across all baselines.

All experiments were conducted under the same hardware environment as CADM. By covering a comprehensive range of baseline paradigms—from traditional statistical methods and sequence models to advanced graph-based spatiotemporal architectures—this comparative framework provides a thorough evaluation of CADM’s performance advantages and applicability across different methodological categories.

3.5. Results

The proposed CADM was compared with a variety of mainstream traffic-prediction approaches across forecasting horizons ranging from 15 min to 60 min.

Table 3 presents the detailed quantitative results, where the best performance at each prediction step is underlined.

From an overall perspective, conventional statistical models (e.g., HA and SVR) exhibit significantly higher errors on all metrics than other model categories, indicating that their linear assumptions fail to capture the complex nonlinear dynamics of traffic evolution. Early time-series models such as GRU and LSTM achieve moderate accuracy in short-term prediction, whereas more recent spatiotemporal graph neural networks (TGCN, STGCN, DCRNN, GWN, etc.) and Transformer-based architectures (STGIN, iTransformer, TimeMixer) demonstrate superior precision and stability, attributed to their stronger ability to capture inter-node spatial dependencies and intricate temporal behaviors.

Across different prediction horizons, CADM performs remarkably well in short-term forecasts (15 min and 30 min), achieving RMSE, MAE, and MAPE close to the best baseline results, thereby reflecting its strong capability for short-range prediction. However, as the forecasting horizon extends (45 min and 60 min), its performance drops more noticeably, with errors increasing at a faster rate, and the advantage gradually diminishes relative to certain graph-based neural models.

This performance shift suggests that CADM is highly adept at capturing short-term traffic dynamics and generating smooth, stable predictions. Nevertheless, at longer temporal scales, the diffusion-based generation process becomes more susceptible to accumulated errors and external uncertainties, leading to a gradual decline in accuracy. This degradation in performance is primarily attributed to error accumulation inherent in the diffusion generation process. During the multi-step reverse denoising phase of conditional diffusion, an increase in predicted time steps predisposes the generated distribution to diverge from the ground truth, thereby causing errors to amplify progressively. Furthermore, the evolution of traffic flow over extended time windows is typically subject to non-stationary factors—such as sudden incidents and complex travel decision-making—which render short-term learnable dynamic patterns increasingly ineffective for long-term prediction. In contrast, deeper structural models such as STGIN and TimeMixer maintain relatively high predictive stability for long-term forecasts, benefiting from their multi-level attention mechanisms that enhance modeling of long-range temporal dependencies.

In summary, while CADM exhibits a distinct advantage in short-term OD prediction, it encounters performance attenuation during medium- to long-term forecasting. Future improvements should be directed towards bolstering the model’s capacity for sustained modeling of long-range dependencies. Specifically, the perception of complex spatiotemporal evolutionary dynamics could be enhanced by incorporating two categories of information—dynamic semantic labels and spatial context relationships—atop the existing POI features.

Firstly, in addition to static POI information, time-sensitive dynamic labels can be introduced. For instance, ‘heat index’ features derived from travel demand, visitation frequency, or real-time crowd intensity statistics could be integrated to characterize the fluctuating activity levels of regional functions across different time intervals. Such dynamic semantic information would facilitate the capture of non-stationary temporal features, such as holiday effects and diurnal travel variations, thereby mitigating the limitations associated with static semantic features in long-term forecasting.

Secondly, spatial contextual associations between POIs can be explicitly incorporated into semantic modeling. By constructing activity correlation graphs between adjacent grids or functionally similar regions (e.g., leveraging spatial adjacency or semantic similarity matrices), the model can be empowered to capture latent semantic coupling and functional interdependence between regions. For example, commercial districts and surrounding dining areas often exhibit strong mobility synergy during peak hours; integrating such spatial dependencies into semantic encoding contributes to enhancing the model’s spatial generalization capabilities.

3.6. Ablation Study

To systematically evaluate the contribution of POI semantic features to the CADM framework, this study designed a comprehensive set of ablation experiments. These experiments verify the effectiveness of each component by progressively removing, perturbing, or simplifying the POI inputs and their associated fusion mechanisms. The experimental configurations are detailed as follows:

CADM: The complete model, integrating OD flow features, POI semantic embeddings, and the cross-attention fusion mechanism.

CADM without POI: The POI input is completely removed, causing the cross-attention module to degenerate into an identity mapping.

CADM with Random POI: Randomized POI vectors are employed to disrupt spatial semantic consistency while maintaining feature dimensionality.

CADM with Static POI: Regional features are replaced with a global average POI vector to eliminate spatial heterogeneity.

CADM without Cross-Attention: POI embeddings are retained, but the cross-attention module is replaced by a simple feature concatenation operation.

All experimental configurations were evaluated under identical conditions, including training hyperparameters, dataset partitioning schemes, and evaluation metrics. To ensure statistical robustness, a fixed random seed was used for each experiment, which was repeated three times; the average results are reported. The experimental results are presented in

Table 4.

This ablation study systematically validates the critical contributions of POI semantic features and the cross-attention fusion mechanism to the performance of the CADM. First, POI semantic features exert a significant influence on overall model performance; upon the removal of POI semantic features, the evaluation metrics for short-term prediction (15 min) exhibited an increase of 15–20%, while metrics for long-term prediction (60 min) increased by 5–15%, indicating that POI semantics play a more pronounced role in modeling short-term traffic dynamics, whereas temporal dependencies gradually assume dominance in long-term prediction. Second, the consistency of spatial semantics is another factor influencing performance; the ablation experiments involving Random POI verified the model’s reliance on authentic POI-OD spatial semantic mappings in real-world scenarios. Notably, the performance of Random POI was marginally superior to the complete removal of POI, suggesting that the model can learn partial information from feature dimensions, but this learning gain is significantly lower than the structural knowledge derived from authentic semantics. Meanwhile, the Static POI configuration consistently underperformed the complete model across all time steps but outperformed Random POI, indicating that while static POI data can provide statistical information, it lacks the capability to express regional functional heterogeneity, such as distinguishing the travel characteristic differences between functional zones like commercial centers and residential areas. Finally, the experimental results regarding Cross-Attention demonstrate that the prediction performance of the model utilizing the cross-attention mechanism is superior to that of the static feature concatenation approach.

In conclusion, the model requires authentic spatial semantic correspondence and dynamic interactions between regional functions to support accurate prediction; furthermore, the results clarify that short-term prediction relies more heavily on spatial semantics, while long-term prediction depends more on temporal dynamic modeling, providing compelling support for the proposed future direction of introducing dynamic POI features (such as real-time crowd heat) into this model.

3.7. Attention Pattern Visualization

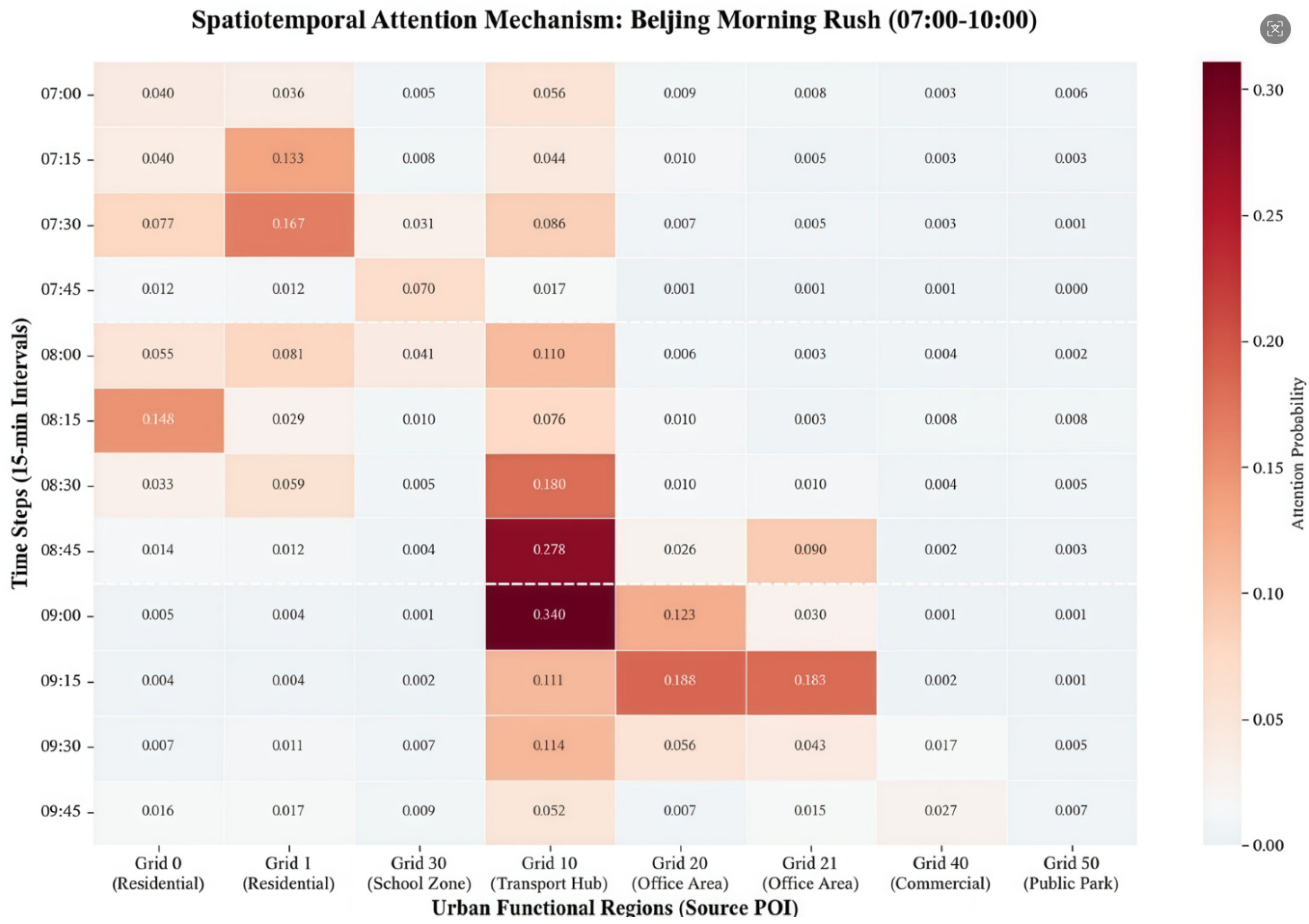

To validate the interpretability of the POI-guided cross-attention mechanism,

Figure 5 visualizes the learned spatiotemporal attention patterns during Beijing’s morning rush hour (07:00–10:00). The heatmap reveals three key characteristics of the model’s semantic awareness.

First, attention allocation exhibits clear functional asymmetry. During early morning (07:00–07:30), residential grids (Grid 0, Grid 1) receive elevated attention weights, capturing outflow patterns as commuters depart. During peak hours (08:30–09:15), attention shifts toward transportation hubs (Grid 10) and office districts (Grid 20, Grid 21), with probabilities reaching 0.18–0.34, reflecting adaptive focus on high-demand destinations. Second, attention evolution demonstrates progressive semantic refinement. Early denoising stages prioritize coarse spatial alignment between functionally complementary regions (e.g., residential-to-hub connections), while later stages concentrate on fine-grained local flows within functionally similar zones. Third, the heatmap confirms semantic coherence. Functionally related regions (e.g., residential and office areas during morning commutes) exhibit synchronized attention peaks, while dissimilar regions (e.g., residential areas and public parks) maintain consistently low weights. This validates the model’s capacity to distinguish semantically distinct mobility patterns and capture functional coupling encoded in POI semantics.

These patterns substantiate that CADM’s cross-attention mechanism provides interpretable, semantically coherent modulation of spatiotemporal reconstruction, enhancing both model transparency and applicability for urban traffic management.