Exploring the Relationship Between the Built Environment and Spatiotemporal Heterogeneity of Urban Traffic Congestion During Tourism Peaks: A Case Study of Harbin, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

- (1)

- Research progress on traffic congestion

- (2)

- Relationship between the built environment and traffic congestion

- (3)

- Spatial heterogeneity modeling methods

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Data Resources

3.3. Grid-Based Partitioning of the Study Area

3.4. Dependent and Explanatory Variables

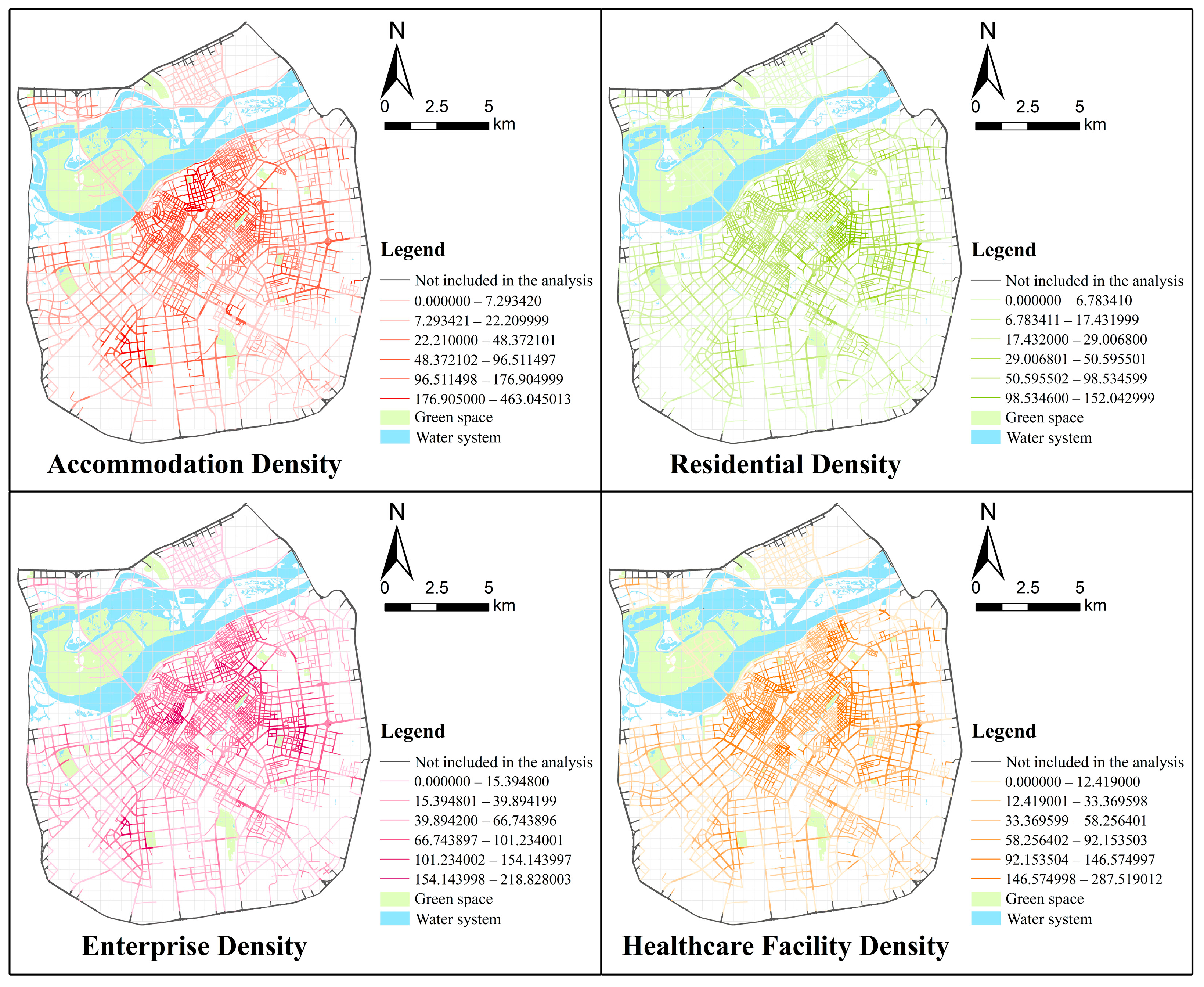

3.5. Definition and Quantification of Variables

3.6. Regression Models

4. Results and Analyses

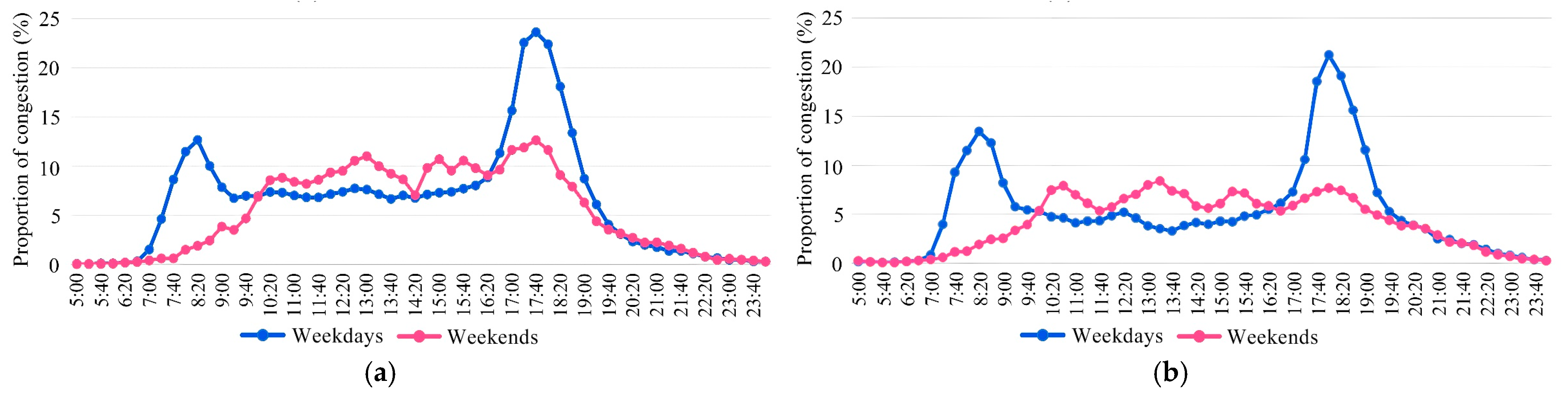

4.1. Temporal Variation in Traffic Congestion

4.2. Spatial Variation in Traffic Congestion

4.3. Modeling Results

4.3.1. Temporal Variations in the Impact of the Built Environment on Traffic Congestion

4.3.2. Spatial Variation in the Impact of the Built Environment on Traffic Congestion

5. Discussion and Policy Implications

5.1. Urban Roads

5.2. Land Use

5.3. Tourism-Related Factors

5.4. Daily Life-Related Factors

5.5. Parking and Transportation Facilities

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MGWR | Multiscale Geographically Weighted Regression |

| OLS | Ordinary Least Squares |

| GWR | Geographically Weighted Regression |

| W-AM | Weekday Morning Peak |

| W-PM | Weekday Evening Peak |

| W-OFF | Weekday Off-Peak |

| H-PK | Holiday Peak/Weekend Peak |

References

- Afrin, T.; Yodo, N. A Survey of Road Traffic Congestion Measures towards a Sustainable and Resilient Transportation System. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saenz-de-Miera, O.; Rossello, J. The responsibility of tourism in traffic congestion and hyper-congestion: A case study from Mallorca, Spain. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 466–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bursa, B.; Mailer, M.; Axhausen, K.W. Travel behavior on vacation: Transport mode choice of tourists at destinations. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2022, 166, 234–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Z.K.; Ou, Y.F.; Chen, S.Z.; Wang, T. Land use impacts on traffic congestion patterns: A tale of a northwestern Chinese city. Land 2022, 11, 2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.Y.; Guan, H.Z.; Han, Y.; Li, W.Y. A study of tourists’ holiday rush-hour avoidance travel behavior considering psychographic segmentation. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Chen, S.; Niu, S.; Ma, Y.; Tang, K. Investigating the impacts of built environment on traffic states incorporating spatial heterogeneity. J. Transp. Geogr. 2020, 83, 102663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, T.; Hong, Y.; Thompson, M.M.; Liu, J.; Hun, X.; Wu, L. How does parking availability interplay with the land use and affect traffic congestion in urban areas? The case study of Xi’an, China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 57, 102126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, A. The law of peak-hour expressway congestion. Traffic Q. 1962, 16, 393–409. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, S.M. Examination of indicators of congestion level. Transp. Res. Rec. 1992, 1360, 150–157. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, P.; Hu, H. Geographical patterns of traffic congestion in growing megacities: Big data analytics from Beijing. Cities 2019, 92, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priambodo, B.; Ahmad, A.; Kadir, R.A. Predicting Traffic Flow Propagation Based on Congestion at Neighbouring Roads Using Hidden Markov Model. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 85933–85946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, G.F.; Cheng, Y.; Ran, B. Urban arterial traffic status detection using cellular data without cellphone GPS information. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2020, 114, 446–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D.; Kim, I.; Zheng, N. Does built environment have impact on traffic congestion?—A bootstrap mediation analysis on a case study of Melbourne. Transp. Res. A Policy Pract. 2024, 190, 104297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Jia, P.; Feng, T.; Li, H.; Kuang, H. Spatiotemporal analysis of built environment restrained traffic carbon emissions and policy implications. Transp. Res. D Transp. Environ. 2023, 121, 103839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Li, L.; Wu, B. Reasons and countermeasures of traffic congestion under urban land redevelopment. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 96, 2164–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, F.; Xiao, Y.; Gao, S. Urban land uses and traffic ‘source-sink areas’: Evidence from GPS-enabled taxi data in Shanghai. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2012, 106, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Phuoc, D.Q.; Young, W.; Currie, G.; De Gruyter, C. Traffic congestion relief associated with public transport: State-of-the-art. Public Transp. 2020, 12, 455–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Lu, X. Quantifying the impact of built environment on traffic congestion: A nonlinear analysis and optimization strategy for sustainable urban planning. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 122, 106249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlton, M.; Brunsdon, C.; Fotheringham, A. Geographically weighted regression-modelling spatial non-stationarity. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. D Stat. 1998, 47, 431–443. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart Fotheringham, A.S.; Chris Brunsdon, C.; Martin Charlton, M. Geographically weighted regression. In The SAGE Handbook of Spatial Analysis; Stewart Fotheringham, A.S., Peter, A., Rogerson, P.A., Eds.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2009; pp. 243–254. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, W.; Wang, S.; Cheng, Z.; Wei, L.; Huang, W. Exploring the effect of built environment on spatiotemporal evolution of traffic congestion using a novel GTWR model: A case study of Hefei, China. Transp. Lett. 2024, 17, 869–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotheringham, A.S.; Yang, W.; Kang, W. Multiscale Geographically Weighted Regression (MGWR). Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2017, 107, 1247–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, W.; Oshan, T.M. Scale and correlation in multiscale geographically weighted regression (MGWR). J. Geogr. Syst. 2025, 27, 399–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, R.; Wu, Z.; Tong, Z.; Qin, S.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, Y. How the built environment promotes public transportation in Wuhan: A multiscale geographically weighted regression analysis. Travel Behav. Soc. 2022, 29, 186–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Zhu, S.; Chen, X.; Liang, J.; Zheng, R. A multi-scale geographically weighted regression approach to understanding community-built environment determinants of cardiovascular disease: Evidence from Nanning, China. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Lai, Y.; Tu, W.; Wu, Y. Exploring the relationship between built environment and spatiotemporal heterogeneity of dockless bike-sharing usage: A case study of Shenzhen, China. Cities 2024, 155, 105504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Wu, X.; Ji, S.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Y. Spatial effects of factors influencing on-street parking duration in newly built-up areas: A case study in Xi’an, China. Cities 2024, 152, 105250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Chen, S.; Li, T.; Niu, S.; Tang, K. Exploring spatial variation of the bus stop influence zone with multi-source data: A case study in Zhenjiang, China. J. Transp. Geogr. 2019, 76, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutsinger, J.; Galster, G.; Wolman, H.; Hanson, R.; Towns, D. Verifying the multi-dimensional nature of metropolitan land use: Advancing the understanding and measurement of sprawl. J. Urban Aff. 2005, 27, 235–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, L.M.; Viegas, J.M.; Silva, E.A. A traffic analysis zone definition: A new methodology and algorithm. Transportation 2009, 36, 581–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomons, E.M.; Pont, M.B. Urban traffic noise and the relation to urban density, form, and traffic elasticity. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2012, 108, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Jia, P.; Feng, T.; Li, H.; Kuang, H.; Zhang, J. Uncovering the spatiotemporal impacts of built environment on traffic carbon emissions using multi-source big data. Land Use Policy 2023, 129, 106621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Z.; Ng, S.T.; Yu, G.; Zhang, X.; Ou, Y. The effect of the built environment on spatial-temporal pattern of traffic congestion in a satellite city in emerging economies. Dev. Built Environ. 2023, 14, 100173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B.; Ma, Y. Correlation Study between Spatial Distribution of Tourism Elements and Transportation Accessibility in Historic Districts of Guangzhou City. Econ. Geogr. 2024, 44, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Ukkusuri, S.V. Spatial variation of the urban taxi ridership using GPS data. Appl. Geogr. 2015, 59, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakayaphun, T.; Hayashi, Y.; Vichiensan, V.; Takeshita, H. Identifying Impacts of School-Escorted Trips on Traffic Congestion and the Countermeasures in Bangkok: An Agent-Based Simulation Approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Li, F.; Aimaitikali, W. Exploring the Effects of Built Environment on Traffic Microcirculation Performance Using XGBoost Model. J. Adv. Transp. 2025, 2025, 8821071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Zhang, L. Spatial Coupling Coordination Evaluation of Mixed Land Use and Urban Vitality in Major Cities in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022, 19, 15586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Liao, Y.; Wang, D.; Zou, Y. Relationship between urban tourism traffic and tourism land use: A case study of Xiamen Island. J. Transp. Land Use 2021, 14, 761–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castrillon, F.; Laval, J. Impact of buses on the macroscopic fundamental diagram of homogeneous arterial corridors. Transp. B: Transp. Dyn. 2018, 6, 286–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johari, M.; Keyvan-Ekbatani, M.; Ngoduy, D. Impacts of bus stop location and berth number on urban network traffic performance. IET Intell. Transp. Syst. 2020, 14, 1546–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Urban road features | Road density | Density of road networks within each grid cell |

| Intersection density | Density of road intersections within each grid cell | |

| Land use features | Land use mix | Shannon entropy index within each grid cell |

| Tourism-related factors | Catering | Mean value of kernel density raster cells for POIs such as Chinese restaurants, fast food, hotpot, bakeries, specialty restaurants, cold drinks, international cuisine, cafés, teahouses, dessert shops, etc., within each grid cell |

| Cultural and recreational | Mean value of kernel density raster cells for POIs such as libraries, museums, science and technology centers, art galleries, planetariums, cultural centers, theaters, and amusement parks within each grid cell | |

| Accommodation | Mean value of kernel density raster cells for POIs such as hotels and hostels within each grid cell | |

| Tourist attraction | Mean value of kernel density raster cells for POIs such as attractions, parks, zoos, botanical gardens, aquariums, temples, city squares, memorials, churches, etc., within each grid cell | |

| Tourism-related retail | Mean value of kernel density raster cells for POIs such as duty-free stores, shopping streets, specialty markets, department stores, and malls within each grid cell | |

| Daily life-related factors | Residence | Mean value of kernel density raster cells for POIs such as residential complexes and mixed-use buildings within each grid cell |

| Education | Mean value of kernel density raster cells for POIs such as schools, research institutes, and driving schools within each grid cell | |

| Healthcare | Mean value of kernel density raster cells for POIs such as hospitals, clinics, and pharmacies within each grid cell | |

| Daily retail | Mean value of kernel density raster cells for POIs such as department stores, electronics stores, home furnishing markets, stationery shops, pet markets, supermarkets, convenience stores, and marketplaces within each grid cell | |

| Enterprises | Mean value of kernel density raster cells for POIs such as industrial parks, companies, factories, and agricultural enterprises within each grid cell | |

| Parking and transportation facilities | Parking facilities | Density of parking facilities within each grid cell |

| Public transit stations | Density of bus and subway stations within each grid cell | |

| Bus route density | Density of bus routes within each grid cell |

| W-AM | W-OFF | |||||

| AICc | Adj R2 | Moran’s I (Residuals) | AICc | Adj R2 | Moran’s I (Residuals) | |

| OLS | 2181.804 | 0.188 | 0.475658 (0.00) * | 1931.002 | 0.402 | 0.414445 (0.00) * |

| GWR | 1969.471 | 0.508 | 0.193620 (0.07) | 1645.127 | 0.649 | 0.191340 (0.06) |

| MGWR | 1622.269 | 0.666 | 0.094464 (0.12) | 1389.102 | 0.744 | 0.093356 (0.12) |

| W-PM | H-PK | |||||

| AICc | Adj R2 | Moran’s I (residuals) | AICc | Adj R2 | Moran’s I (residuals) | |

| OLS | 1874.552 | 0.442 | 0.41912 (0.00) * | 1845.067 | 0.461 | 0.374854 (0.00) * |

| GWR | 1606.649 | 0.698 | 0.189743 (0.08) | 1504.035 | 0.727 | 0.157528 (0.10) |

| MGWR | 1286.554 | 0.785 | 0.121773 (0.14) | 1266.302 | 0.798 | 0.087753 (0.19) |

| Independent Variable | W-AM | W-OFF | W-PM | H-PK | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BW | Mean | EP | BW | Mean | EP | BW | Mean | EP | BW | Mean | EP | |

| Intercept | 44 | −0.060 | 62.90 | 44 | −0.038 | 55.35 | 44 | 0.031 | 69.83 | 44 | 0.025 | 46.72 |

| Road density | 782 | 0.107 | 64.48 | 820 | −0.087 | 66.30 | 52 | 0.076 | 38.20 | 46 | −0.086 | 31.75 |

| Intersection density | 818 | −0.117 | 100.00 | 44 | −0.139 | 23.72 | 252 | −0.210 | 80.66 | 344 | −0.171 | 91.73 |

| Land use mix index | 44 | 0.114 | 13.14 | 820 | −0.003 | 0.00 | 44 | 0.143 | 29.56 | 44 | −0.051 | 21.29 |

| Catering | 820 | 0.151 | 100.00 | 812 | 0.222 | 100.00 | 811 | 0.164 | 100.00 | 820 | 0.102 | 100.00 |

| Cultural and recreational | 455 | −0.009 | 0.00 | 820 | −0.120 | 100.00 | 820 | −0.034 | 0.00 | 820 | −0.065 | 100.00 |

| Accommodations | 820 | −0.187 | 100 | 547 | −0.089 | 45.86 | 820 | 0.026 | 0.00 | 364 | 0.113 | 54.62 |

| Tourist attractions | 820 | 0.008 | 0.00 | 445 | 0.162 | 93.67 | 470 | 0.108 | 82.85 | 440 | 0.150 | 96.23 |

| Tourism-related retail | 820 | 0.009 | 0.00 | 816 | −0.135 | 100.00 | 820 | −0.065 | 63.38 | 63 | 0.010 | 40.63 |

| Residence | 820 | 0.046 | 0.00 | 820 | −0.011 | 0.00 | 820 | −0.001 | 0.00 | 820 | −0.037 | 0.00 |

| Education | 820 | −0.012 | 0.00 | 816 | 0.091 | 100.00 | 183 | 0.091 | 28.83 | 181 | 0.097 | 55.23 |

| Healthcare | 818 | −0.077 | 0.00 | 820 | −0.163 | 100.00 | 820 | −0.109 | 100.00 | 820 | −0.131 | 100.00 |

| Daily retail | 83 | −0.087 | 13.02 | 820 | 0.059 | 0.00 | 820 | 0.049 | 0.00 | 820 | 0.057 | 0.00 |

| Enterprises | 820 | 0.049 | 0.00 | 820 | 0.085 | 0.00 | 820 | 0.035 | 0.00 | 820 | −0.013 | 0.00 |

| Parking facilities | 820 | 0.001 | 0.00 | 185 | 0.083 | 52.68 | 820 | −0.004 | 0.00 | 330 | 0.115 | 63.38 |

| Public transport stations | 820 | −0.062 | 12.65 | 820 | −0.046 | 0.00 | 612 | −0.083 | 67.39 | 820 | −0.061 | 60.46 |

| Bus route density | 44 | 0.266 | 36.62 | 44 | 0.448 | 52.07 | 46 | 0.437 | 68.49 | 44 | 0.528 | 75.06 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cui, R.; Zhang, J. Exploring the Relationship Between the Built Environment and Spatiotemporal Heterogeneity of Urban Traffic Congestion During Tourism Peaks: A Case Study of Harbin, China. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 470. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14120470

Cui R, Zhang J. Exploring the Relationship Between the Built Environment and Spatiotemporal Heterogeneity of Urban Traffic Congestion During Tourism Peaks: A Case Study of Harbin, China. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 2025; 14(12):470. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14120470

Chicago/Turabian StyleCui, Renyue, and Jun Zhang. 2025. "Exploring the Relationship Between the Built Environment and Spatiotemporal Heterogeneity of Urban Traffic Congestion During Tourism Peaks: A Case Study of Harbin, China" ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 14, no. 12: 470. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14120470

APA StyleCui, R., & Zhang, J. (2025). Exploring the Relationship Between the Built Environment and Spatiotemporal Heterogeneity of Urban Traffic Congestion During Tourism Peaks: A Case Study of Harbin, China. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 14(12), 470. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14120470