Schema Retrieval for Korean Geographic Knowledge Base Question Answering Using Few-Shot Prompting

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We develop a language model based schema retrieval model for GeoKBQA: the proposed model addresses the limitations of traditional rule-based methods by dynamically inferring relationships between queries and schema items, demonstrating strong generalization capabilities.

- We create a prompt for few-shot prompting-based schema retrieval: using the Spatial Knowledge Reasoning Engine (SKRE) dataset, we developed optimal prompts tailored to the dense schema retrieval of Korean geographic questions.

- We adapt few-shot prompting techniques for dense schema retrieval: this study leverages few-shot prompting to handle complex, multi-hop, and entity-less queries, providing a robust alternative to fine-tuning-based methods.

2. Related Works

2.1. Schema Retrieval of KBQA

2.1.1. BERT Fine-Tuning-Based Schema Retrieval

2.1.2. GPT Few-Shot Prompting-Based Schema Retrieval

2.2. Schema Retrieval of GeoKBQA

2.3. Dataset for Schema Retrieval in Korean GeoKBQA

3. Methodology

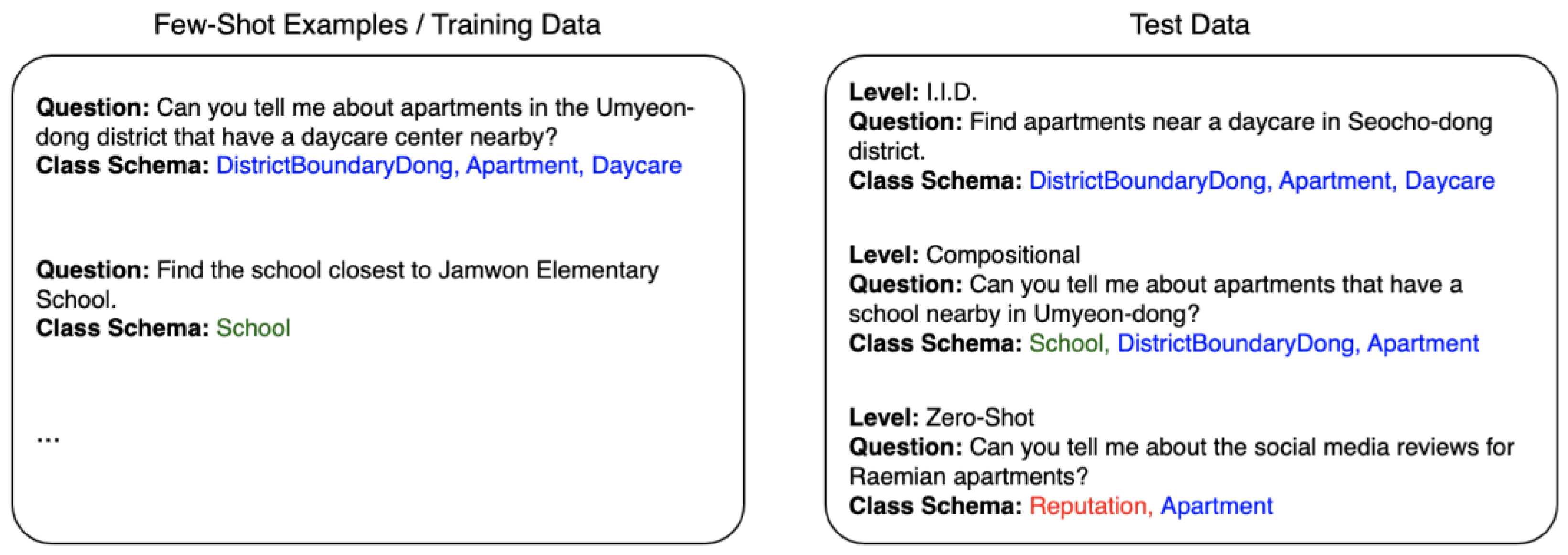

3.1. Dataset Construction and Generalization Levels

- I.I.D. generalization: This level assesses the model’s ability to handle queries that align with the schema items and question structures seen in the few-shot examples or training data. For example, as you can see in the left side of Figure 2, there is a training data point that asks “Can you tell me about apartments in the Umyeon-dong district that have a daycare center nearby?” and employs class schema items “apartment”, “DistrictBoundaryDong”, and “daycare”. A corresponding I.I.D. level test data point could be “Find apartments near a daycare in Seocho-dong district”, which uses a similar question structure and identical schema combination.

- Compositional generalization: This level evaluates the model’s ability to process new combinations of schema items encountered during training. For instance, the training data in Figure 2 include queries like “Can you tell me about apartments in the Umyeon-dong district that have a daycare center nearby?”, which has the corresponding class schema items “apartment”, “DistrictBoundaryDong”, “daycare”, and “Find the school closest to Jamwon Elementary School”, and the schema item “school”. A compositional test query might combine these schema items in a new way, asking “Can you tell me about apartments that have a school nearby in Umyeon-dong?” This requires the use of “apartment”, “school”, and “DistrictBoundaryDong”.

- Zero-shot generalization: This level measures the model’s ability to handle schema items it has never encountered during training. For example, if the training data contain no mention of the class schema “reputation”, a zero-shot level query like “Can you tell me about the social media reviews for Raemian apartments?” evaluates the model’s ability to infer and retrieve this unseen schema item alongside the item of apartment.

3.2. Schema Retrieval Models

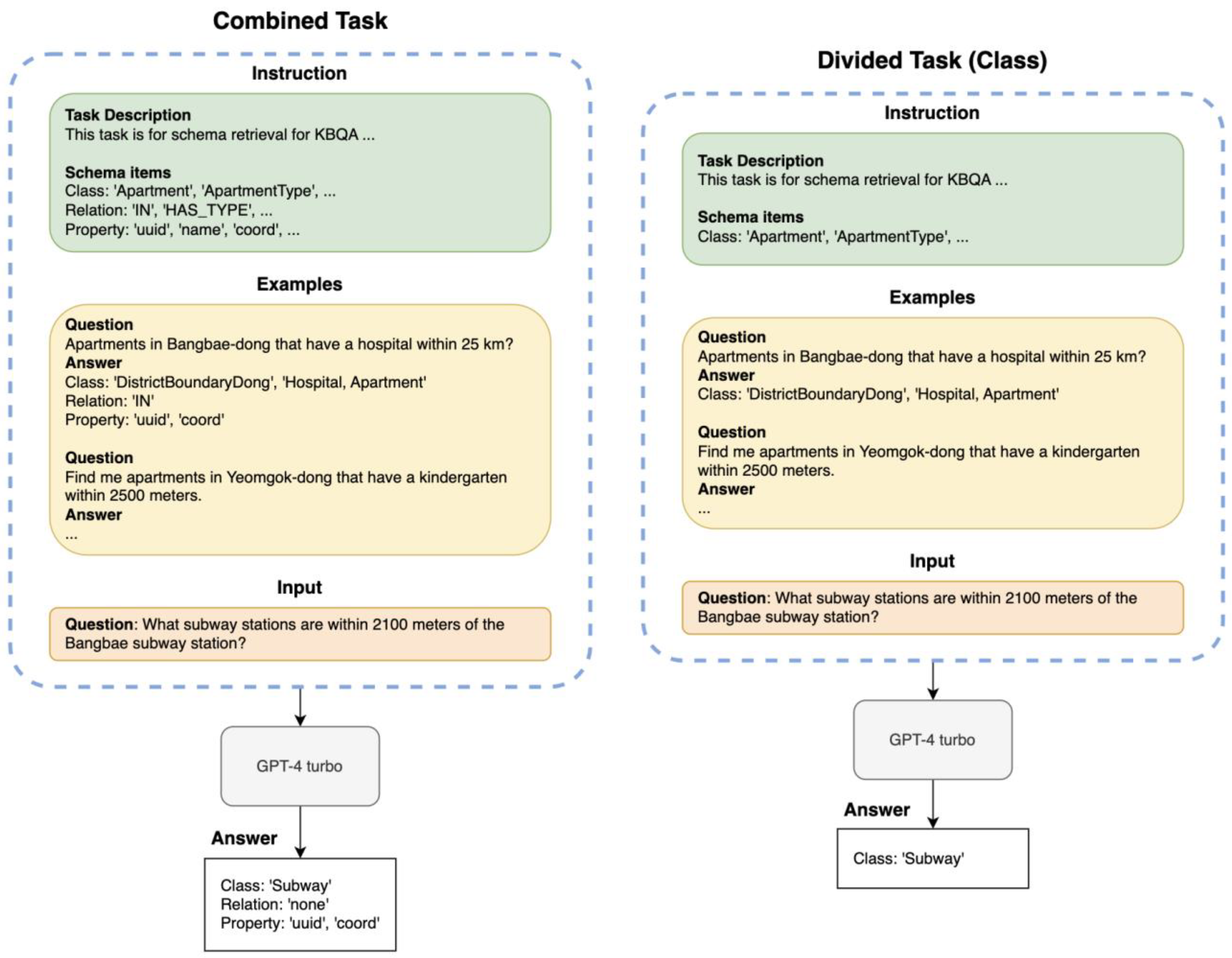

3.2.1. GPT Few-Shot Prompting-Based Model

- Processing Methods

- 2.

- Number of Few-Shot Examples

- 3.

- Instructions

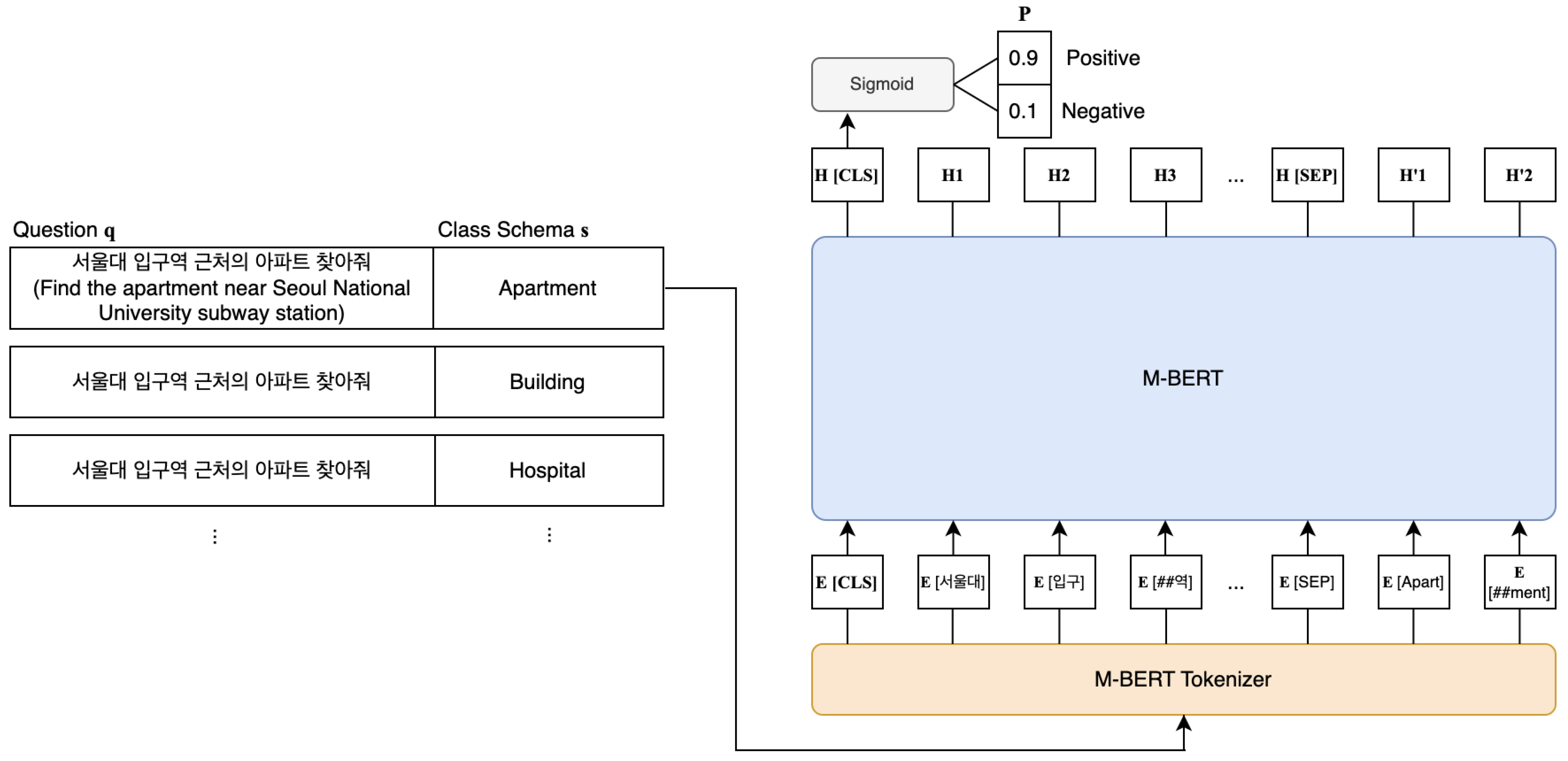

3.2.2. BERT Fine-Tuning-Based Model

4. Experimental Setup

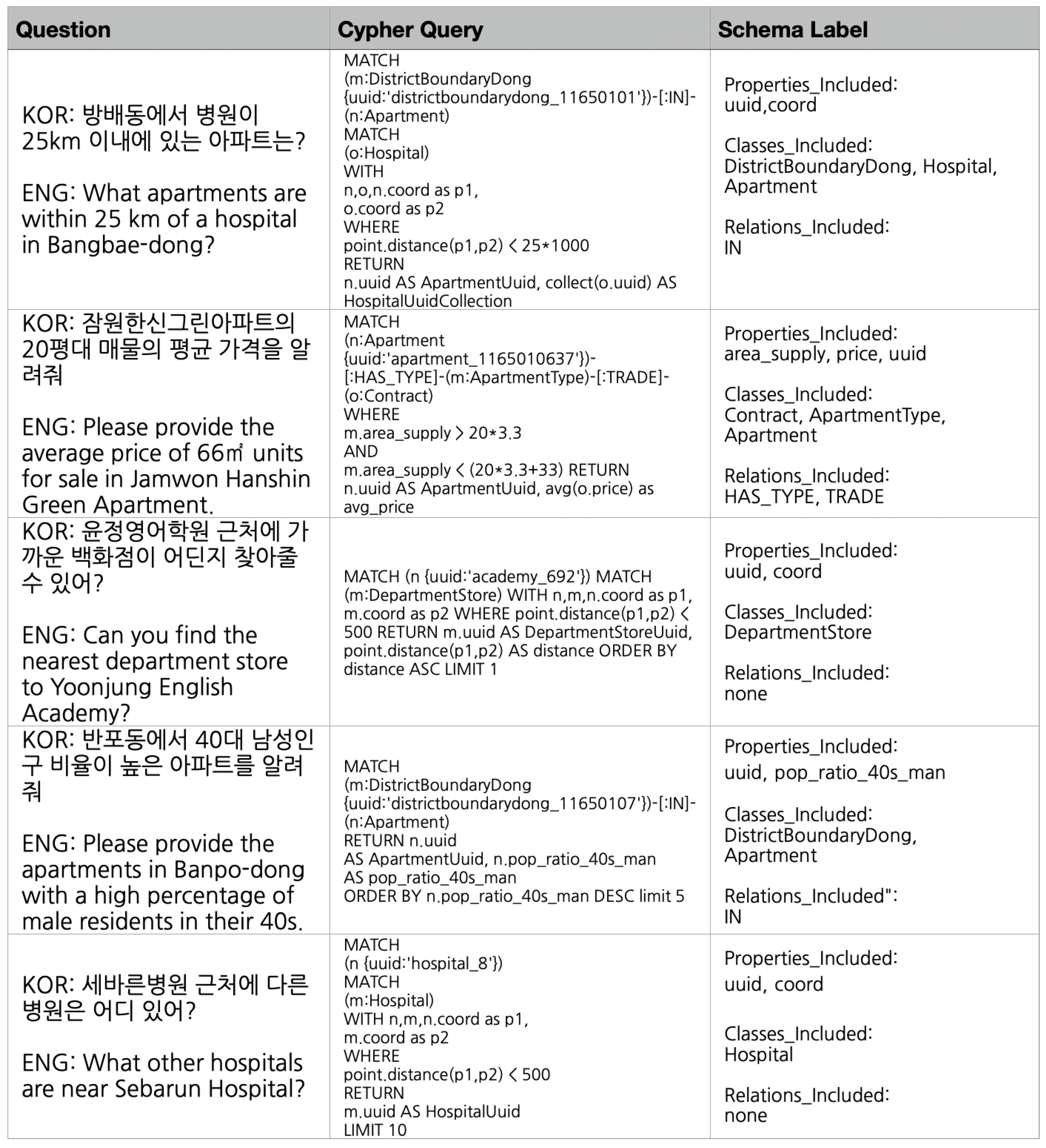

4.1. Dataset

4.2. Implementation Details

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

- Match (x {uuid:‘sub_123′})-[:NEARBY]->(y:Hospital);

- Match (x: Subway {name: ‘Seoul National University’})-[:NEARBY]->(y:Hospital).

5. Results

5.1. Dataset Construction Results

5.2. Prompt Searching Results for GPT Few-Shot Prompting-Based Model

- Processing Methods

- 2.

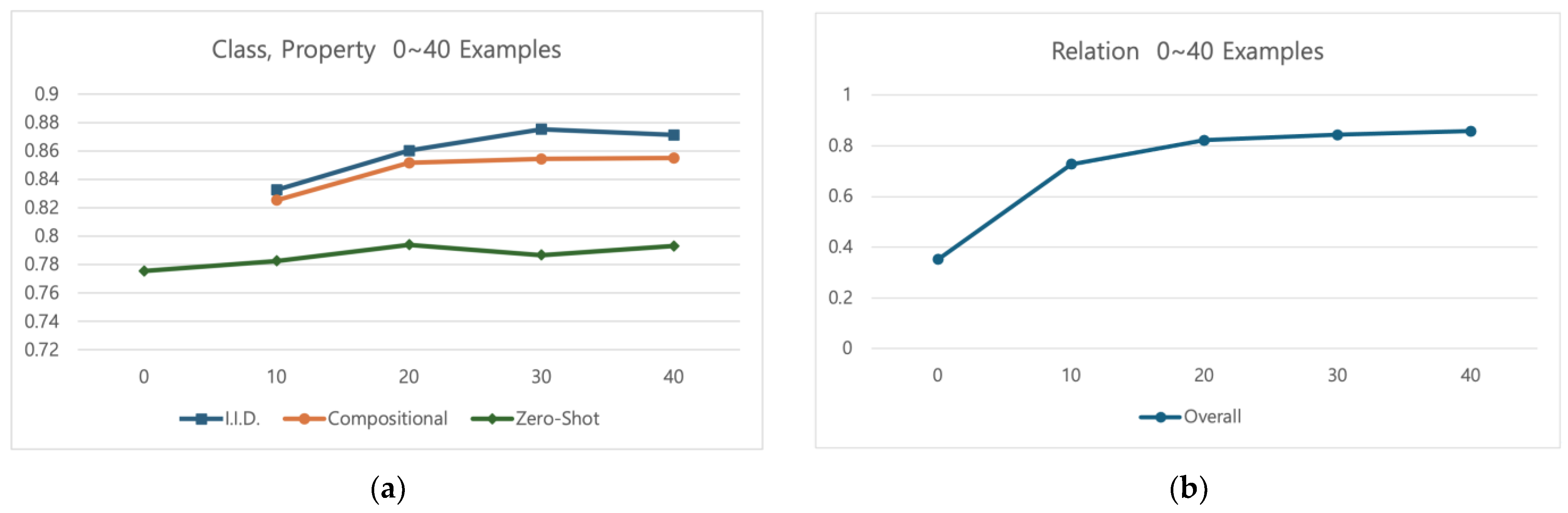

- Number of Few-Shot Examples

- 3.

- Instructions

5.3. Comparison Results for GPT Few-Shot Prompting and BERT Fine-Tuning-Based Models

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Level | Ins. | Hit@1 | Hit@2 | Hit@3 | Hit@4 | Hit@5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I.I.D. | 1 | 0.5110 | 0.9246 | 0.9286 | 0.9567 | 0.9567 |

| 2 | 0.6101 | 0.9571 | 0.9594 | 0.9661 | 0.9684 | |

| 3 | 0.4352 | 0.9864 | 0.9872 | 0.9934 | 0.9986 | |

| Comp. | 1 | 0.8751 | 0.9165 | 0.9506 | 0.9567 | 0.9865 |

| 2 | 0.5687 | 0.9473 | 0.9583 | 0.9583 | 0.9583 | |

| 3 | 0.6071 | 0.9286 | 0.9765 | 0.9867 | 0.9898 | |

| Zero-shot | 1 | 0.4352 | 0.8778 | 0.8792 | 0.8912 | 0.9054 |

| 2 | 0.6901 | 0.9125 | 0.9166 | 0.9264 | 0.9354 | |

| 3 | 0.6836 | 0.9036 | 0.9534 | 0.9567 | 0.9864 |

| Level | Ins. | Hit@1 | Hit@2 | Hit@3 | Hit@4 | Hit@5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I.I.D. | 1 | 0.4962 | 0.9350 | 0.9350 | 0.9358 | 0.9358 |

| 2 | 0.5966 | 0.9855 | 0.9954 | 0.9954 | 0.9954 | |

| 3 | 0.5612 | 0.9855 | 0.9855 | 0.9962 | 0.9984 | |

| Comp. | 1 | 0.3799 | 0.8781 | 0.8855 | 0.8861 | 0.8872 |

| 2 | 0.5364 | 0.9848 | 0.9848 | 0.9891 | 0.9891 | |

| 3 | 0.4248 | 0.9935 | 0.9950 | 0.9950 | 0.9972 | |

| Zero-shot | 1 | 0.5124 | 0.8465 | 0.8470 | 0.8481 | 0.8961 |

| 2 | 0.6145 | 0.8943 | 0.8943 | 0.9002 | 0.9013 | |

| 3 | 0.6185 | 0.9101 | 0.9205 | 0.9315 | 0.9555 |

References

- Brown, T.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.D.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A. Language Models Are Few-Shot Learners. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 1877–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, A.; Jain, S.K. A Survey on Question Answering Systems with Classification. J. King Saud. Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2016, 28, 345–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Kase, S.; Vanni, M.; Sadler, B.; Liang, P.; Yan, X.; Su, Y. Beyond IID: Three Levels of Generalization for Question Answering on Knowledge Bases. In Proceedings of the The Web Conference, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 19–23 April 2021; pp. 3477–3488. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Liu, Q.; Yu, Z.; Lin, C.-Y.; Lou, J.-G.; Jiang, F. ReTraCk: A Flexible and Efficient Framework for Knowledge Base Question Answering. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing: System Demonstrations, Online, 1–6 August 2021; pp. 325–336. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, X.; Yavuz, S.; Hashimoto, K.; Zhou, Y.; Xiong, C. RNG-KBQA: Generation Augmented Iterative Ranking for Knowledge Base Question Answering. In Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), Dublin, Ireland, 22–27 May 2022; Association for Computational Linguistics: Dublin, Ireland, 2022; pp. 6032–6043. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, Y.; Yu, Z.; Li, Y.; Karlsson, B.; Ma, T.; Qu, Y.; Lin, C.Y. TIARA: Multi-Grained Retrieval for Robust Question Answering over Large Knowledge Base. In Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 7–11 December 2022; Association for Computational Linguistics: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2022; pp. 8108–8121. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Jang, H.; Yu, K. Geographic Knowledge Base Question Answering over OpenStreetMap. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2024, 13, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T. Developing a Transformer-Based Natural Language Entity Linking Model to Improve the Performance of GeoKBQA. Master’s Thesis, Seoul National University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2023; pp. 1–96. [Google Scholar]

- Bollacker, K.; Evans, C.; Paritosh, P.; Sturge, T.; Taylor, J. Freebase: A Collaboratively Created Graph Database for Structuring Human Knowledge. In Proceedings of the 2008 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data (SIGMOD’08), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 9–12 June 2008; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 1247–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrandečić, D.; Krötzsch, M. Wikidata: A Free Collaborative Knowledgebase. Commun. ACM 2014, 57, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Ma, X.; Zhuang, A.; Gu, Y.; Su, Y.; Chen, W. Few-Shot In-Context Learning on Knowledge Base Question Answering. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), Toronto, ON, Canada, 9–14 July 2023; Association for Computational Linguistics: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2023; pp. 6966–6980. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, G.; Bao, J.; Zhao, W. Interactive-KBQA: Multi-Turn Interactions for Knowledge Base Question Answering with Large Language Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.15131. [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski, T.; Choi, E.; Artzi, Y.; Zettlemoyer, L. Scaling Semantic Parsers with On-the-Fly Ontology Matching. In Proceedings of the 2013 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Seattle, WA, USA, 18–21 October 2013; Association for Computational Linguistics: Seattle, WA, USA, 2013; pp. 1545–1556. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.-W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; Association for Computational Linguistics: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2019; pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, L.; McDonell, K. Prompt Programming for Large Language Models: Beyond the Few-Shot Paradigm. In Proceedings of the Extended Abstracts of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI EA’21), New York, NY, USA, 2–7 June 2021; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2021. Article 314. pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Mai, G.; Janowicz, K.; Zhu, R.; Cai, L.; Lao, N. Geographic Question Answering: Challenges, Uniqueness, Classification, and Future Directions. AGILE GISci. Ser. 2021, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punjani, D.; Singh, K.; Both, A.; Koubarakis, M.; Angelidis, I.; Bereta, K.; Beris, T.; Bilidas, D.; Ioannidis, T.; Karalis, N.; et al. Template-Based Question Answering over Linked Geospatial Data. In Proceedings of the 12th Workshop on Geographic Information Retrieval (GIR’18), New York, NY, USA, 6 November 2018; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2018. Article 7. pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Hamzei, E.; Tomko, M.; Winter, S. Translating Place-Related Questions to GeoSPARQL Queries. In Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2022, Lyon, France, 25–29 April 2022; pp. 902–911. [Google Scholar]

- Kefalidis, S.-A.; Punjani, D.; Tsalapati, E.; Plas, K.; Pollali, M.; Mitsios, M.; Tsokanaridou, M.; Koubarakis, M.; Maret, P. Benchmarking Geospatial Question Answering Engines Using the Dataset GeoQuestions1089. In Proceedings of the Semantic Web—ISWC 2023: 22nd International Semantic Web Conference, Athens, Greece, 6–10 November 2023; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 266–284. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J.; Cao, S.; Hou, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, H. TransferNet: An Effective and Transparent Framework for Multi-Hop Question Answering over Relation Graph. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Online and Punta Cana, Dominican Republic, 7–11 November 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics: Online and Punta Cana, Dominican Republic, 2021; pp. 4149–4158. [Google Scholar]

- Yih, W.T.; Richardson, M.; Meek, C.; Chang, M.W.; Suh, J. The Value of Semantic Parse Labeling for Knowledge Base Question Answering. In Proceedings of the 54th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Berlin, Germany, 7–12 August 2016; Association for Computational Linguistics: Berlin, Germany, 2016; Volume 2, pp. 201–206. [Google Scholar]

- Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; McGrew, B. GPT-4 Technical Report. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.08774. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS’17), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 6000–6010. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.; Petroni, F.; Josifoski, M.; Riedel, S.; Zettlemoyer, L. Scalable Zero-Shot Entity Linking with Dense Entity Retrieval. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP 2020), Online, 16–20 November 2020; Association for Computational Linguistics: Online, 2020; pp. 6397–6407. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, J.; Shinzato, K. Cross-Encoder Data Annotation for Bi-Encoder Based Product Matching. In Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing: Industry Track, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 7–11 December 2022; Association for Computational Linguistics: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2022; pp. 161–168. [Google Scholar]

- Han, W.; Jiang, Y.; Ng, H.T.; Tu, K. A Survey of Unsupervised Dependency Parsing. In Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Barcelona, Spain, 8–13 December 2022; International Committee on Computational Linguistics: Online and Barcelona, Spain, 2020; pp. 2522–2533. [Google Scholar]

- Talmor, A.; Berant, J. The Web as a Knowledge Base for Answering Complex Questions. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, New Orleans, LA, USA, 1–6 June 2018; Association for Computational Linguistics: New Orleans, LA, USA, 2018; Volume 1, pp. 641–651. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Wallace, E.; Feng, S.; Klein, D.; Singh, S. Calibrate Before Use: Improving Few-Shot Performance of Language Models. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Online, 18–24 July 2021; pp. 12697–12706. [Google Scholar]

- Min, S.; Lyu, X.; Holtzman, A.; Artetxe, M.; Lewis, M.; Hajishirzi, H.; Zettlemoyer, L. Rethinking the Role of Demonstrations: What Makes In-Context Learning Work? In Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 7–11 December 2022; Association for Computational Linguistics: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2022; pp. 11048–11064. [Google Scholar]

- Shrawgi, H.; Rath, P.; Singhal, T.; Dandapat, S. Uncovering Stereotypes in Large Language Models: A Task Complexity-Based Approach. In Proceedings of the 18th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), St. Julian’s, Malta, 7–22 March 2024; Association for Computational Linguistics: St. Julian’s, Malta, 2024; pp. 1841–1857. [Google Scholar]

- Sheetrit, E.; Brief, M.; Mishaeli, M.; Elisha, O. ReMatch: Retrieval Enhanced Schema Matching with LLMs. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.01567. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, L.; Wu, J.; Jiang, X.; Almeida, D.; Wainwright, C.; Mishkin, P.; Zhang, C.; Agarwal, S.; Slama, K.; Ray, A. Training Language Models to Follow Instructions with Human Feedback. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 27730–27744. [Google Scholar]

- Zamfirescu-Pereira, J.D.; Wong, R.Y.; Hartmann, B.; Yang, Q. Why Johnny Can’t Prompt: How Non-AI Experts Try (and Fail) to Design LLM Prompts. In Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI’23), Hamburg, Germany, 23–28 April 2023; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2023. Article 437. pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bsharat, S.M.; Myrzakhan, A.; Shen, Z. Principled Instructions Are All You Need for Questioning LLaMA-1/2, GPT-3.5/4. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.16171. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Xu, W.; Lan, Y.; Hu, Z.; Lan, Y.; Lee, R.K.-W.; Lim, E.-P. Plan-and-Solve Prompting: Improving Zero-Shot Chain-of-Thought Reasoning by Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), Toronto, ON, Canada, 9–14 July 2023; Association for Computational Linguistics: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2023; pp. 2609–2634. [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande, A.; Murahari, V.; Rajpurohit, T.; Kalyan, A.; Narasimhan, K. Toxicity in ChatGPT: Analyzing Persona-Assigned Language Models. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2023, Singapore, 6–10 December 2023; Association for Computational Linguistics: Singapore, 2023; pp. 1236–1270. [Google Scholar]

- White, J.; Fu, Q.; Hays, S.; Sandborn, M.; Olea, C.; Gilbert, H.; Elnashar, A.; Spencer-Smith, J.; Schmidt, D.C. A Prompt Pattern Catalog to Enhance Prompt Engineering with ChatGPT. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.11382. [Google Scholar]

- Pires, T.; Schlinger, E.; Garrette, D. How Multilingual Is Multilingual BERT? In Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Florence, Italy, 28 July–2 August 2019; Association for Computational Linguistics: Florence, Italy, 2019; pp. 4996–5001. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Jang, H.; Baik, Y.; Park, S.; Shin, H. KR-BERT: A Small-Scale Korean-Specific Language Model. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2008.03979. [Google Scholar]

- Mikolov, T.; Sutskever, I.; Chen, K.; Corrado, G.; Dean, J. Distributed Representations of Words and Phrases and Their Compositionality. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems—Volume 2, Lake Tahoe, NV, USA, 5–8 December 2013; Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2013; Volume 2, pp. 3111–3119. [Google Scholar]

| Instruction 1 |

| This task is schema retrieval for Korean GeoKBQA. Given total schema items and question, you must find the five best matching items with the question. Note: Do not include any explanations or apologies in your responses. And if there is no correct match, return ‘none’. |

| Instruction 2 |

| For the Korean geographic KBQA schema retrieval task, examine the provided list of schema items and a corresponding question. Your objective is to identify the five schema items that directly correspond to the given question. If none of the schema items match, respond with ‘none’. Always return exactly five results, whether they are less relevant. Please keep your response concise and limit it to the matching schema item only; avoid providing any additional explanations or apologies. Furthermore, verify the completion of the task and if any errors are identified, restart the task from the beginning. |

| Instruction 3 |

| For the Korean geographic KBQA schema retrieval task, examine the provided list of schema items and a corresponding question. Act as an expert information specialist specialized in the geographical KBQA domain to ensure consistency and relevance in your responses. 1. Assessment Carefully assess each schema item to determine its relevance to the provided query. 2. Selection Identify the schema item that most accurately corresponds to the query. If no appropriate schema item exists, your response should be ‘none’. 3. Response Formation Respond solely with the name of the most relevant schema item or ‘none’ if a suitable match is absent. 4. Result Presentation Provide a list of five different schema items, prioritizing relevance. If fewer than five directly relevant items are found, include less relevant items to complete the list of five. Remember: Avoid including any additional explanations or commentary in your response. If any errors are detected during the process, reassess the information and repeat the assessment if necessary. |

| Method | hit@1 | hit@2 | hit@3 | hit@4 | hit@5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combined | 0.4111 | 0.6502 | 0.7500 | 0.7623 | 0.8750 |

| Divided | 0.5954 | 0.9293 | 0.9311 | 0.9611 | 0.9725 |

| Schema | Level | 0 Examples | 10 Examples | 20 Examples | 30 Examples | 40 Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avg. of Class and Property | I.I.D. | N/A | 0.8325 | 0.8602 | 0.8752 | 0.8711 |

| Comp. | N/A | 0.8252 | 0.8515 | 0.8542 | 0.8550 | |

| Zero-shot | 0.7754 | 0.7824 | 0.7938 | 0.7865 | 0.7930 | |

| Relation | N/A | 0.3521 | 0.7278 | 0.8215 | 0.8431 | 0.8575 |

| Level | Instruction No. | Hit@2~5 Avg. |

|---|---|---|

| I.I.D. | 1 | 0.9417 |

| 2 | 0.9628 | |

| 3 | 0.9914 | |

| Comp. | 1 | 0.9526 |

| 2 | 0.9556 | |

| 3 | 0.9704 | |

| Zero-shot | 1 | 0.8884 |

| 2 | 0.9227 | |

| 3 | 0.9500 |

| Level | Instruction No. | Hit@2~5 Avg. |

|---|---|---|

| I.I.D. | 1 | 0.9354 |

| 2 | 0.9929 | |

| 3 | 0.9914 | |

| Comp. | 1 | 0.8842 |

| 2 | 0.9870 | |

| 3 | 0.9952 | |

| Zero-shot | 1 | 0.8594 |

| 2 | 0.8975 | |

| 3 | 0.9294 |

| Level | Instruction No. | Hit@1 | Hit@2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| N/A | 1 | 0.6263 | 0.8293 |

| 2 | 0.7565 | 0.8943 | |

| 3 | 0.8780 | 0.9063 |

| Schema | Level | Model | Hit@1 | Hit@2 | Hit@3 | Hit@4 | Hit@5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class | I.I.D. | FS | 0.4352 | 0.9864 | 0.9872 | 0.9934 | 0.9986 |

| FT | 0.5768 | 0.9946 | 0.9957 | 0.9961 | 0.9961 | ||

| Comp. | FS | 0.6071 | 0.9286 | 0.9765 | 0.9867 | 0.9898 | |

| FT | 0.6964 | 0.9964 | 0.9964 | 0.9982 | 0.9982 | ||

| Zero-shot | FS | 0.6836 | 0.9036 | 0.9534 | 0.9567 | 0.9864 | |

| FT | 0.5892 | 0.7985 | 0.7985 | 0.7985 | 0.8078 | ||

| Property | I.I.D. | FS | 0.5612 | 0.9855 | 0.9855 | 0.9962 | 0.9984 |

| FT | 0.8671 | 0.9976 | 0.9981 | 0.9995 | 0.9995 | ||

| Comp. | FS | 0.4248 | 0.9935 | 0.9950 | 0.9950 | 0.9972 | |

| FT | 0.4099 | 0.9864 | 0.9891 | 0.9968 | 0.9985 | ||

| Zero-shot | FS | 0.6185 | 0.9101 | 0.9205 | 0.9315 | 0.9555 | |

| FT | 0.5661 | 0.8455 | 0.8485 | 0.8594 | 0.8684 | ||

| Relation | N/A | FS | 0.8780 | 0.9063 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| FT | 0.9782 | 0.9863 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, S.; Yu, K. Schema Retrieval for Korean Geographic Knowledge Base Question Answering Using Few-Shot Prompting. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2024, 13, 453. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi13120453

Lee S, Yu K. Schema Retrieval for Korean Geographic Knowledge Base Question Answering Using Few-Shot Prompting. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 2024; 13(12):453. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi13120453

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Seokyong, and Kiyun Yu. 2024. "Schema Retrieval for Korean Geographic Knowledge Base Question Answering Using Few-Shot Prompting" ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 13, no. 12: 453. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi13120453

APA StyleLee, S., & Yu, K. (2024). Schema Retrieval for Korean Geographic Knowledge Base Question Answering Using Few-Shot Prompting. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 13(12), 453. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi13120453