Placial-Discursive Topologies of Violence: Volunteered Geographic Information and the Reproduction of Violent Places in Recife, Brazil

Abstract

1. Introduction and Related Work

1.1. Geographies of Unsafety and Traditional Spatial Criminology

1.2. Placing (Un)safety

1.3. VGI and Placing (Un)safety in the Landscape

2. Study Setup

2.1. Empirical Context

2.2. Methodology

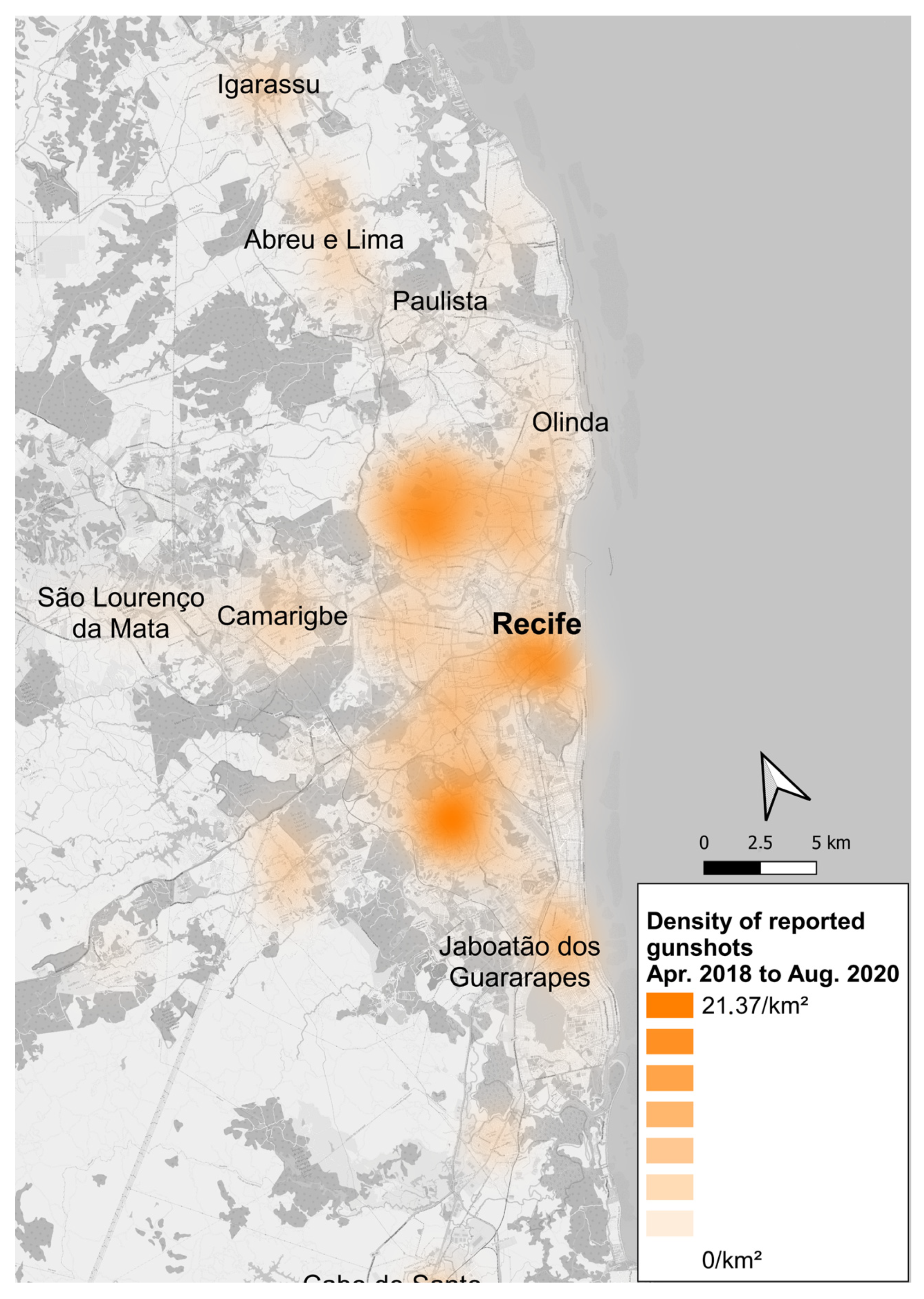

2.2.1. VGI Mapping

2.2.2. Semi-Structured Interviews

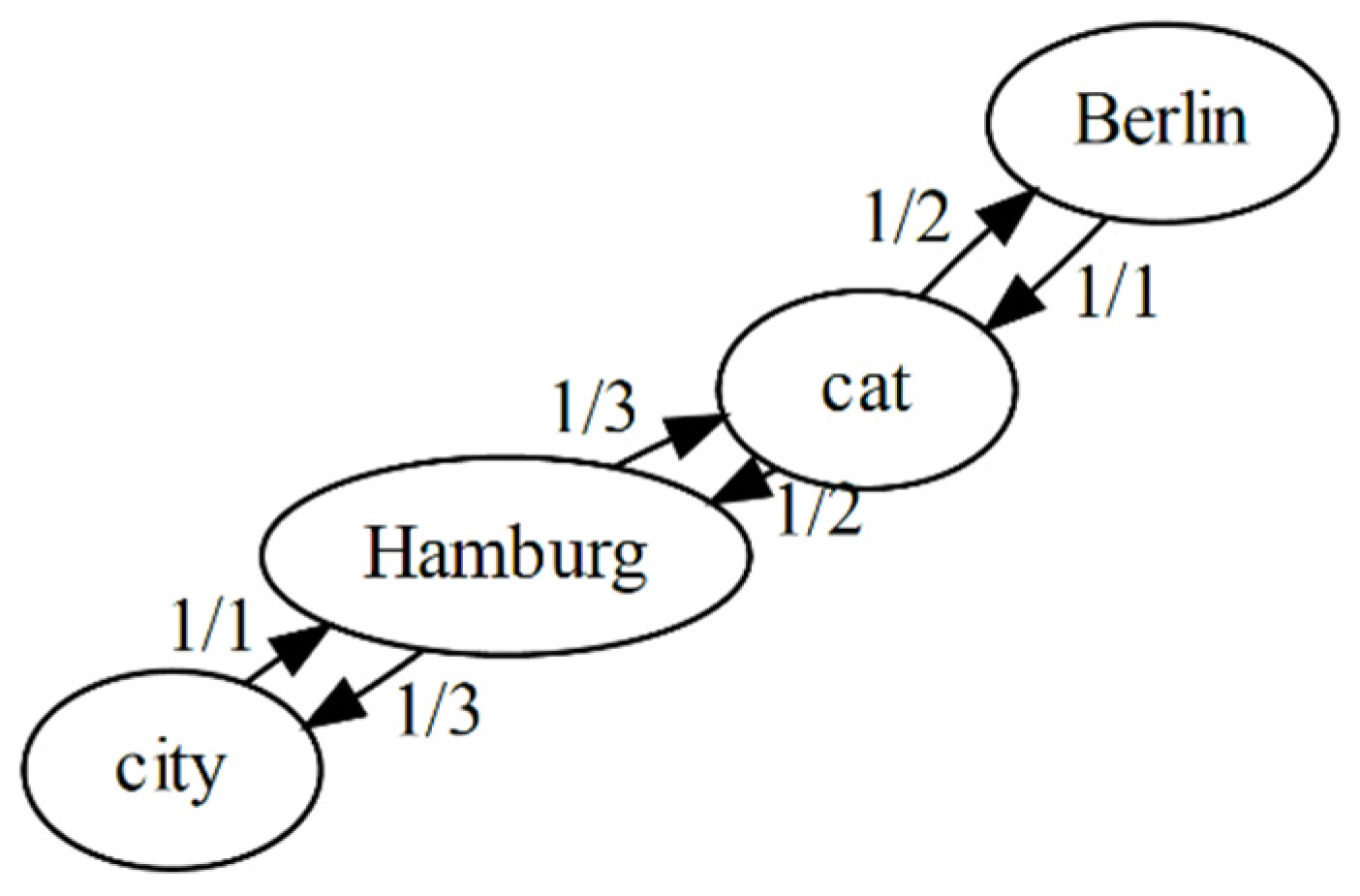

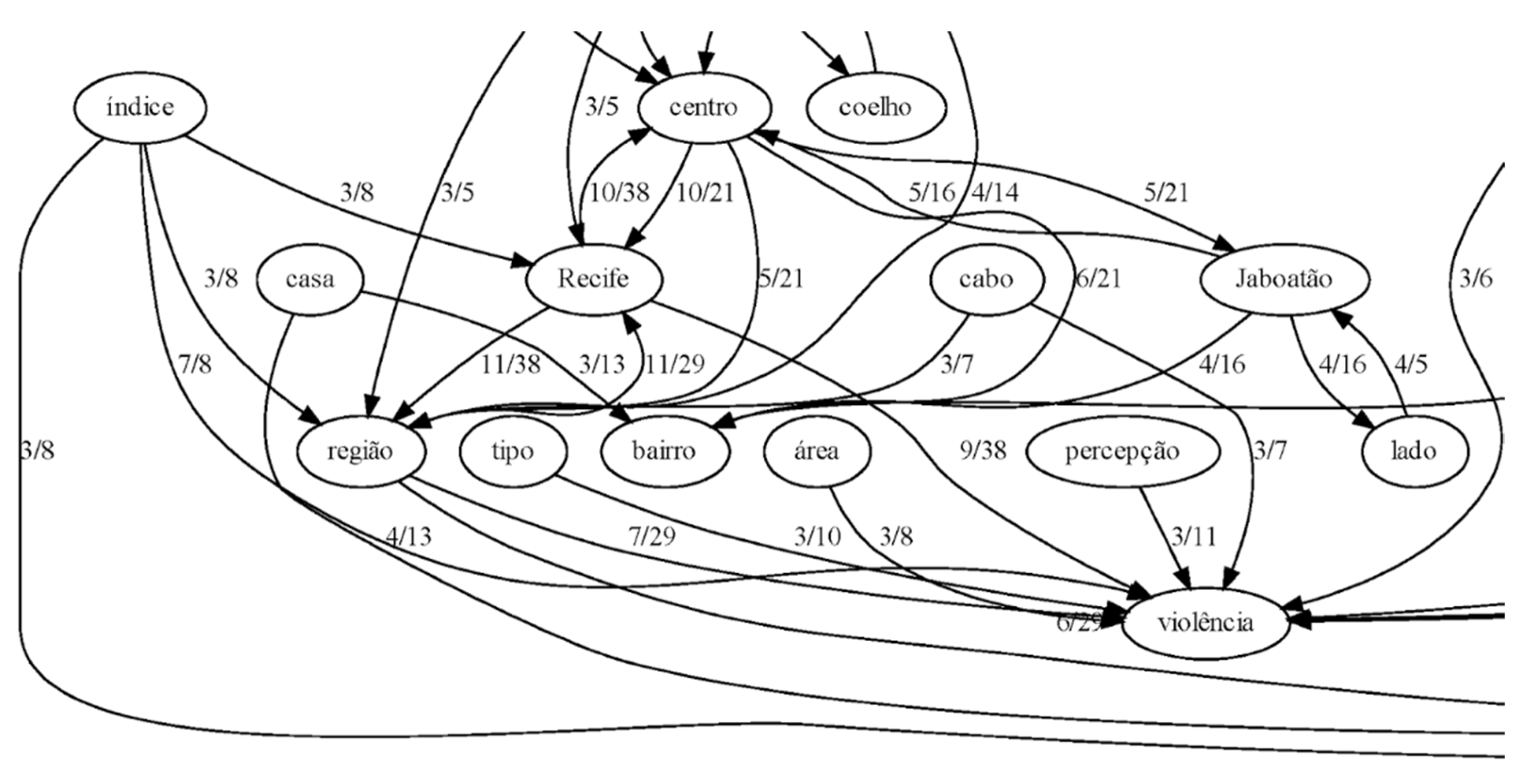

2.2.3. Semi-Automated Text Analysis

2.2.4. Synthesis

3. Results and Interpretation

3.1. Mobility

Int.: Are you afraid of taking public transportation?Participant n. 6: Who isn’t?! Yes, I am. Here it is normal to be afraid of public transportation. But there isn’t just one fear; there are many! We know what happens there, but we need to take it. We cannot just refuse to take it. There isn’t another option. So, safety in public transportation does not exist here, either because of violence or the issues inherent to the transportation system.

Participant n. 4: I was living in the metropolitan area before in a city close to Recife. I was living in Camaragibe. I had two horrible experiences with robbery. Those experiences traumatized me. So, I decided to live close to my work. I did that to avoid using public busses.Participant n. 1: [...] There was always the fear of being robbed. I was so afraid of it that my mother saved money and bought me a car. We did that to reduce the risks. Especially because I had to do the medical training and I had to circulate among different community health facilities over the city. And those facilities are located in [unsafe neighbourhoods]. Being a woman taking the bus alone in those communities is just too dangerous. With a car, it will be safer.

Participant 5: Actually I feel fear. You know, we do not feel safe at all! So, you take a bus here at the BR (Federal Road), as I do everyday. So, I see two or three men entering the bus in the BR and they do “o rapa” (rob everyone at once [i.e., an armed holdup]). So, that is exactly our fear. We take the bus everyday but we do not know what is going to happen. We do not know if we will come back home safe and alive.

Participant 6: […] we see on television robberies taking place on the bus. You see it several times. So, you feel unsafe on the bus. So, you have to stay vigilant, pay attention to what people are doing and look for a strategic place to sit because you may have to be ready to get off of the bus immediately.Participant n. 3: In my perception, violent acts increased in Recife and the Metropolitan area. I follow the news on television and I see that. Violence is for sure growing.

3.2. Sources of “Everyday VGI”

Interviewer: How did you know that those places are dangerous and violent?Participant n. 2: I find out through social networks, friends, colleagues [...] TV news and social media.

Participant n. 6:[...] Cardinot TV show is extremely famous here. Everybody watches his program at lunchtime to see all the violent cases that happened during the day.Participant n. 1:[...] Cadinot is a very famous reporter here regarding community journalism. Cardinot shows the violence in the communities here in Recife and Metropolitan areas. He also has an Instagram account with the news [...].

Participant n. 4:[...] Actually, I try to filter all the information I get before reposting it. Not everyone does what I do, but I really try to repost things that are important [...]. I only repost things on WhatsApp that I know are important to my contacts.

3.3. Perception of Dangerous Areas

Officer n. 1:Cabo (Cabo de Santo Agostinho) and Ipojuca. On the other side of Recife, there are Itamaracá, Itapissuma, and Paulista. Paulista, in my opinion, is the city with higher rates of violence. These are a kind of small city in the metropolitan area. Jaboatão dos Gauararapes is a big city close to Recife with high rates of criminality in specific neighbourhoods.Officer n. 4:In my opinion Boa Viagem is the most violent neighbourhood in Recife [...] there are many favelas there. I think Boa Viagem is very violent because of the property crimes like robbery and car theft, and also homicide. According to my experience working in the city centre, I would also say that Santo Amaro and Coque are also very violent.

Participant n. 2:I think the south area of Recife [is more violent]. There are many communities inside of this area. Being inside buses and the metro is also dangerous. In the city centre of Recife, for example, there is a neighbourhood called Santo Amaro. There are many robberies taking place close to the entrance of the metro station. The streets there are strange and full of homeless people. Of course, the probability of risk is higher there.

Participant n. 2:The map is true. It is reporting reality because it is exactly those areas that we see in the news.Officer n. 3:I think Jaboatão should be more red. There are missing data in this map [...]. However, this area in Cabo (de Santo Agostinho) is really violent. As I told you before, the city centre of Cabo (de Santo Agostinho), Cohab, and Charnequinha are really violent. So, the red spot there is correct. Recife is also correct but still missing some data in the Nova Descoberta neighbourhood.

3.4. Narratives Binding the Spatial Perception of Danger

Participant n. 3: I feel a bit more safe in places with large movements of people such as the beach sidewalk, for example. Of course it will depend on time [of day] and if the police forces are there. Jaqueira Park, for example, there is always police there during the day. So, I feel safe there.

Participant n. 5:Unfortunately, we have violence everywhere. There is a lot of criminality, violence against women, violence against children, violence when they kidnap people, in robbery, homicide, everything! [...] I know that violence is everywhere: here in Jaboatão (dos Guararapes) and Recife we see everyday violent acts in the afternoon news. [...] there is no public investment in safety.

Officer n. 1: So, the majority of violent crimes are related to the drug trade in both the south and the north part of the metropolitan area. There is a ‘facção’ there that initially was created in the municipality of Ipojuca called “trem bala” and now runs the drug trade there. Before this facçcão, the drug trade was decentralized, but now this facção manages the drug trade in the region of Cabo de Santo Agostinho and Ipojuca.

4. Discussion

- (a)

- From VGI maps to social media: Beside technical solutions providing the opportunity to report individual observations of violence like gun shootings, mediated social media channels revealed to have much more impact on day-to-day communications than map artefacts.

- (b)

- The update problem: One reason for the advantage of simple social media solutions is that map artefacts have one important conceptual limitation: As maps are aggregate artefacts derived from different information sources, tracking a dynamically developing topic like violence leads to visualisations that usually rely on outdated, incomplete or even conflicting information. Rendering maps on a daily basis will overcome the update problem only at the cost of sparse data not suitable for aggregation at all.

- (c)

- From containers to mobility: Reflecting the update problem on its cognitive end, even for human agents generalising observations of violence on the level of dangerous regions remains too vague for decision-making. As we were able to obtain from the example of public transportation, dangerous spaces can be shifters even themselves.

- (d)

- Background framing: Depending on the professional group, different indicators (like signs of drug trade) were monitored closely by individuals to obtain additional information on where to go and where not to go.

5. Reflection and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bryant, K. Chicago School of Criminology. In The Encyclopedia of Theoretical Criminology; Miller, J., Ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2014; pp. 1–3. ISBN 978-1-118-517-390. [Google Scholar]

- Matlovicova, K. Theoretical Framework of the Intra-Urban Criminality Research: Main Approaches in the Criminological Thought. Folia Geogr. 2014, 2, 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Zahnow, R.; Wickes, R. Violence and Aggression in Socially Disorganized Neighborhoods. In The Wiley Handbook of Violence and Aggression; Sturmey, P., Ed.; Wiley Blackwell: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1–12. ISBN 978-1-119-05755-0. [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson, B. Digitize and Punish: Racial Criminalization in the Digital Age; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-1-5179-0923-9. [Google Scholar]

- Garland, D. The Culture of Control: Crime and Social Order in Contemporary Society; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-022-628-384-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, S. The Spectacle of the ‘Other’. In Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices, 2nd ed.; Hall, S., Evans, J., Nixon, S., Eds.; SAGE: London, UK, 2013; pp. 215–287. ISBN 978-184-920-547-4. [Google Scholar]

- Eck, J.; Weisburd, D. Crime Places in Crime Theory. In Crime and Place; Eck, J., Weisburd, D., Eds.; Criminal Justice Press: Monsey, NY, USA, 1995; pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Weisburd, D. The Law of Crime Concentration and the Criminology of Place. Criminology 2015, 53, 133–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisburd, D.; Wire, S. Crime Hot Spots. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice; Pontell, H., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-019-026-407-9. [Google Scholar]

- Brantingham, P.; Brantingham, P. Criminality of place: Crime generators and crime attractors. Eur. J. Crim. Policy Res. 1995, 3, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisburd, D.; Groff, E.; Yang, S.-M.; Telep, C. Criminology of Place. In Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice; Bruinsma, G., Weisburd, D., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 848–857. ISBN 978-1-4614-5689-6. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, R.H.; Kitchen, A.T. Planning For Crime Prevention: A Transatlantic Perspective; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-041-524-136-6. [Google Scholar]

- Brantingham, P.J.; Brantingham, P.L.; Song, J.; Spicer, V. Crime Hot Spots, Crime Corridors and the Journey to Crime: An Expanded Theoretical Model of the Generation of Crime Concentrations. In Geographies of Behavioural Health, Crime, and Disorder; Lersch, K., Chakraborty, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2020; pp. 61–86. ISBN 978-3-030-33467-3. [Google Scholar]

- Schatzki, T. The Site of the Social: A Philosophical Account of the Constitution of Social Life and Change; Penn State University Press: University Park, PA, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-0-271-02292-5. [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell, T. Place: A Short Introduction; Blackwell Pub.: Malden, MA, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-1405-10671-9. [Google Scholar]

- Kremer, D. Rekonstruktion von Orten als Sozialem Phänomen: Geoinformatische Analyse Semantisch Annotierter Verhaltensdaten; UBP: Bamberg, Germany, 2018; ISBN 978-3-86309-579-6. [Google Scholar]

- Werlen, B. Sozialgeographie Alltäglicher Regionalisierungen: Band 2: Globalisierung, Region und Regionalisierung; Franz Steiner Verlag: Stuttgart, Germany, 1997; ISBN 351-506-607-1. [Google Scholar]

- Schlottmann, A. RaumSprache: Ost-West-Differenzen in der Berichterstattung zur Deutschen Einheit. Eine Sozialgeographische Theorie; Franz Steiner Verlag: Stuttgart, Germany, 2005; ISBN 978-3-515-08700-1. [Google Scholar]

- Weichhart, P.; Weixlbaumer, N. Lebensqualität und Stadtteilsbewußtsein in Lehen: Ein stigmatisiertes Salzburger Stadtviertel im Urteil seiner Bewohner. In Beiträge zur Geographie von Salzburg, Zum 25-jährigen Bestehen des Institutes für Geographie der Universität Salzburg und zum 21. Deutschen Schulgeographentag in Salzburg; Riedl, H., Ed.; Selbstverl. d. Inst. für Geographie d. Univ. Salzburg: Salzburg, AT, USA, 1988; pp. 230–271. [Google Scholar]

- Felgenhauer, T. Geographie als Argument: Eine Untersuchung regionalisierender Begründungspraxis am Beispiel “Mitteldeutschland; Franz Steiner Verlag: Stuttgart, Germany, 2007; ISBN 978-3-515-09078-0. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, S.; Freksa, C. Approaching the notion of place by contrast. J. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2012, 31–50. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/p8xja78h (accessed on 18 November 2021).

- Richter, D.; Winter, S.; Richter, K.-F.; Stirling, L. How People Describe Their Place: Identifying Predominant Types of Place Descriptions. In GEOCROWD ’12, Proceedings of the 1st ACM SIGSPATIAL International Workshop on Crowdsourced and Volunteered Geographic Information, Redondo Beach, CA, USA, 6 November 2012; Goodchild, M., Pfoser, D., Sui, D., Eds.; Goodchild, M., Pfoser, D., Sui, D., Eds.; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, D.; Vasardani, M.; Stirling, L.; Richter, K.-F.; Winter, S. Zooming In–Zooming Out Hierarchies in Place Descriptions. In Progress in Location-Based Services; Krisp, J., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2013; pp. 339–355. [Google Scholar]

- Belina, B.; Kreissl, R.; Kretschmann, A.; Ostermeier, L. (Eds.) Kritische Kriminologie und Sicherheit, Staat und Gouvernementalität: 10. Beiheft Kriminologisches Journal; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Belina, B. Kriminalität und Raum: Zur Kritik der Kriminalgeographie und zur Produktion des Raums. Krim. J. 2000, 32, 129–147. [Google Scholar]

- Belina, B. Der Alltag der Anderen: Racial Profiling in Deutschland. In Sicherer Alltag? Politiken und Mechanismen der Sicherheitskonstruktion im Alltag; Dollinger, B., Schmidt-Semisch, H., Eds.; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2016; pp. 123–146. [Google Scholar]

- Kutschinske, K.; Meier, V. “…sich diesen Raum zu nehmen und sich freizulaufen…”: Angst-Räume als Ausdruck von Geschlechterkonstruktion. Geogr. Helv. 2000, 55, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wucherpfennig, C.; Fleischmann, K. Feministische Geographien und geographische Geschlechterforschung im deutschsprachigen Raum. ACME 2008, 7, 350–376. [Google Scholar]

- Glasze, G.; Pütz, R.; Rolfes, M. Die Verräumlichung von (Un-)Sicherheit, Kriminalität und Sicherheitspolitiken: Herausforderungen einer Kritischen Kriminalgeographie. In Diskurs-Stadt-Kriminalität: Städtische (Un-)Sicherheiten aus der Perspektive von Stadtforschung und Kritischer Kriminalgeographie; Glasze, G., Pütz, R., Rolfes, M., Eds.; Transcript: Bielefeld, Germany, 2015; pp. 13–104. ISBN 978-3-8394-0408-9. [Google Scholar]

- Redepenning, M.; Neef, H.; Gomes, E. Verflüssigende (Un-) Sicherheiten: Über Räumlichkeiten des Strassenhandels am Beispiel Brasiliens. Geogr. Helv. 2010, 65, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Newburn, T.; Stanko, E. (Eds.) Just Boys Doing Business? Men, Masculinities and Crime; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-1-136-14396-0. [Google Scholar]

- Siriaraya, P.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Kawai, Y.; Mittal, M.; Jeszenszky, P.; Jatowt, A. Witnessing Crime through Tweets: A Crime Investigation Tool Based on Social Media. In 27th ACM SIGSPATIAL International Conference on Advances in Geographic Information Systems, Proceedings of the ACM SIGSPATIAL GIS 2019, Chicago, IL, USA, 5–8 November 2019; Banei-Kashani, F., Trajcevski, G., Güting, R.H., Kulik, L., Newsam, S., Eds.; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 568–571. [Google Scholar]

- Prieto Curiel, R.; Cresci, S.; Muntean, C.I.; Bishop, S.R. Crime and its fear in social media. Palgrave Commun. 2020, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodchild, M.F. Citizens as sensors: The world of volunteered geography. GeoJournal 2007, 69, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, B.B.; Rinner, C. A Qualitative Framework for Evaluating Participation on the Geoweb. J. Urban Reg. Inf. Syst. Assoc. 2013, 25, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Skarlatidou, A.; Haklay, M. (Eds.) Geographic Citizen Science Design: No One Left Behind; UCL Press: London, UK, 2021; ISBN 978-1-78735-612-2. [Google Scholar]

- Bonney, R.; Phillips, T.B.; Ballard, H.L.; Enck, J.W. Can citizen science enhance public understanding of science? Public Underst. Sci. 2015, 25, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trojan, J.; Schade, S.; Lemmens, R.; Frantál, B. Citizen science as a new approach in Geography and beyond: Review and reflections. Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2019, 27, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwood, S.; Goodchild, M.F.; Sui, D.Z. Researching Volunteered Geographic Information: Spatial Data, Geographic Research, and New Social Practice. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2012, 102, 571–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tversky, B. Cognitive Maps, Cognitive Collages, and Spatial Mental Models. In Spatial Information Theory. A Theoretical Basis for GIS, Proceedings of the European Conference (COSIT’93), Marciana Marina, IT, 19–22 September 1993; Frank, A., Campari, I., Eds.; Frank, A., Campari, I., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1993; pp. 14–24. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Global Study on Homicide: Executive Summary, Vienna, AT. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/3fv8mrw9 (accessed on 18 November 2021).

- Cerqueira, D.; Bueno, S.; Palmieri Alves, P.; de Lima, R.S.; da Silva Enid, R.A.; Ferreira, H.; Pimentel, A.; Barros, B.; Marques, D.; Pacheco, D.; et al. Atlas da Violência 2020. Available online: http://repositorio.ipea.gov.br/handle/11058/10129 (accessed on 5 July 2022).

- Madensen, T.; Eck, J. Crime Places and Place Management. In The Oxford Handbook of Criminological Theory; Cullen, F., Wilcox, P., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 555–578. ISBN 978-0-19-974723-8. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, B.B.; Moura de Souza, C.; Pedroso, E.; Lai, R.S.; Hunter, P.; Tam, J.; Cave, I.; Swanlund, D.; Barbosa, K.G. Towards a Situated Spatial Epidemiology of Violence: A Placially-Informed Geospatial Analysis of Homicide in Alagoas, Brazil. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, K.G.; Walker, B.B.; Da Vieira Silva, A.; Procópio Gonzaga, G.L.; Maio de Brum, E.H.; Ribeiro, M.C. Spatial-temporal patterns of homicide in socioeconomically deprived settings: Violence in Alagoas, Brazil, 2006–2015. Glob. Health Action 2021, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, K.G.; Walker, B.B.; Schuurman, N.; Cavalcanti, S.D.; Ferreira, E.; Ferreira, R.C. Epidemiological and spatial characteristics of interpersonal physical violence in a Brazilian city: A comparative study of violent injury hotspots in familial versus non-familial settings, 2012-2014. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0208304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daudelin, J.; Ratton, J. Illegal Markets, Violence, and Inequality: Evidence from a Brazilian Metropolis; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Germany, 2018; ISBN 978-3-319-76248-7. [Google Scholar]

- Moura de Souza, C. Youth and Violence in Brazil: An ethnographic study on youth street violence related to drugs and social order in Brazil’s violent city of Maceió. In Understanding Retaliation, Mediation and Punishment: Collected Results; Sureau, T., Auge, Y., Eds.; Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology: Halle/Saale, Germany, 2019; pp. 151–157. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/21.11116/0000-0006-4685-5 (accessed on 18 November 2021).

- Cerqueira, D.; Ferreira, H.; Bueno, S.; Palmieri Alves, P.; de Lima, R.S.; Marques, D.; da Silva, F.A.G.; Lunelli, I.C.; Rodrigues, R.I.; de Oliveira Accioly Lins, G.; et al. Atlas da Violência 2021, São Paulo, BR. 2021. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/f73ur6ha (accessed on 19 November 2021).

- Fogo Cruzado. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/2p8w43re (accessed on 7 December 2021).

- Dammann, F.; Dzudzek, I.; Glasze, G.; Mattissek, A.; Schirmel, H. Verfahren der lexikometrisch-computerlinguistischen Analyse von Textkorpora. In Handbuch Diskurs und Raum; Glasze, G., Mattissek, A., Eds.; Transcript Verlag: Bielefeld, Germany, 2021; pp. 313–344. ISBN 978-3-8394-3218-1. [Google Scholar]

- Fayyad, U.; Piatetsky-Shapiro, G.; Smyth, P. From Data Mining to Knowledge Discovery in Databases. AI Mag. 1996, 17, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurafsky, D.; Martin, J.H. Speech and Language Processing: An Introduction to Natural Language Processing, Computational Linguistics, and Speech Recognition; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2021; Available online: https://tinyurl.com/4z3bu4x8 (accessed on 18 November 2021).

- Cao, N.; Cui, W. Introduction to Text Visualization; Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2016; ISBN 978-94-6239-186-4. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Tao, Y.; Lin, H. Semantic word cloud generation based on word embeddings. Proceedings of 2016 IEEE Pacific Visualization Symposium (PacificVis), Taipeh, TW, USA, 19–22 April 2016; Hansen, C., Viola, I., Yuan, X., Eds.; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 239–240, ISBN 978-1-5090-1451-4. [Google Scholar]

- Haarmann, B. Ontology on demand: Vollautomatische Ontologieerstellung aus deutschen Texten mithilfe moderner Textmining-Prozesse; epubli: Berlin, Germany, 2014; ISBN 978-3-8442-9684-6. [Google Scholar]

- Janowicz, K.; Gao, S.; McKenzie, G.; Hu, Y.; Bhaduri, B. GeoAI: Spatially explicit artificial intelligence techniques for geographic knowledge discovery and beyond. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2020, 34, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubenhofer, N. Muster aus korpuslinguistischer Sicht. In Handbuch Satz, Äußerung, Schema; Dürscheid, C., Schneider, J.G., Eds.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2015; pp. 485–502. ISBN 978-3-11-029603-7. [Google Scholar]

- Farhadloo, M.; Rolland, E. Multi-Class Sentiment Analysis with Clustering and Score Representation. In ICDMW 2013, Proceedings of IEEE 13th International Conference on Data Mining Workshops, Dallas, TX, USA, 7–10 December 2013; Ding, W., Washio, T., Xiong, H., Karypis, G., Thuraisingham, B., Cook, D., Wu, X., Eds.; IEEE: Los Alamitos, CA, USA, 2013; pp. 904–912. ISBN 978-1-4799-3142-2. [Google Scholar]

- Hipp, J.; Güntzer, U.; Nakhaeizadeh, G. Algorithms for association rule mining—A general survey and comparison. SIGKDD Explor. 2000, 2, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cresswell, T. On the move: Mobility in the Modern Western World; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-415-95255-2. [Google Scholar]

- Haklay, M. Neogeography and the Delusion of Democratisation. Environ. Plan. A 2013, 45, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, L.; Lally, N. For geographical imagination systems. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2021, 111, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, R. Transgressions: Reflecting on critical GIS and digital geographies. Digit. Geogr. Soc. 2021, 2, 100011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moura de Souza, C.; Kremer, D.; Walker, B.B. Placial-Discursive Topologies of Violence: Volunteered Geographic Information and the Reproduction of Violent Places in Recife, Brazil. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 500. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi11100500

Moura de Souza C, Kremer D, Walker BB. Placial-Discursive Topologies of Violence: Volunteered Geographic Information and the Reproduction of Violent Places in Recife, Brazil. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 2022; 11(10):500. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi11100500

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoura de Souza, Cléssio, Dominik Kremer, and Blake Byron Walker. 2022. "Placial-Discursive Topologies of Violence: Volunteered Geographic Information and the Reproduction of Violent Places in Recife, Brazil" ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 11, no. 10: 500. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi11100500

APA StyleMoura de Souza, C., Kremer, D., & Walker, B. B. (2022). Placial-Discursive Topologies of Violence: Volunteered Geographic Information and the Reproduction of Violent Places in Recife, Brazil. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 11(10), 500. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi11100500