Beyond the Sex Doll: Post-Human Companionship and the Rise of the ‘Allodoll’

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

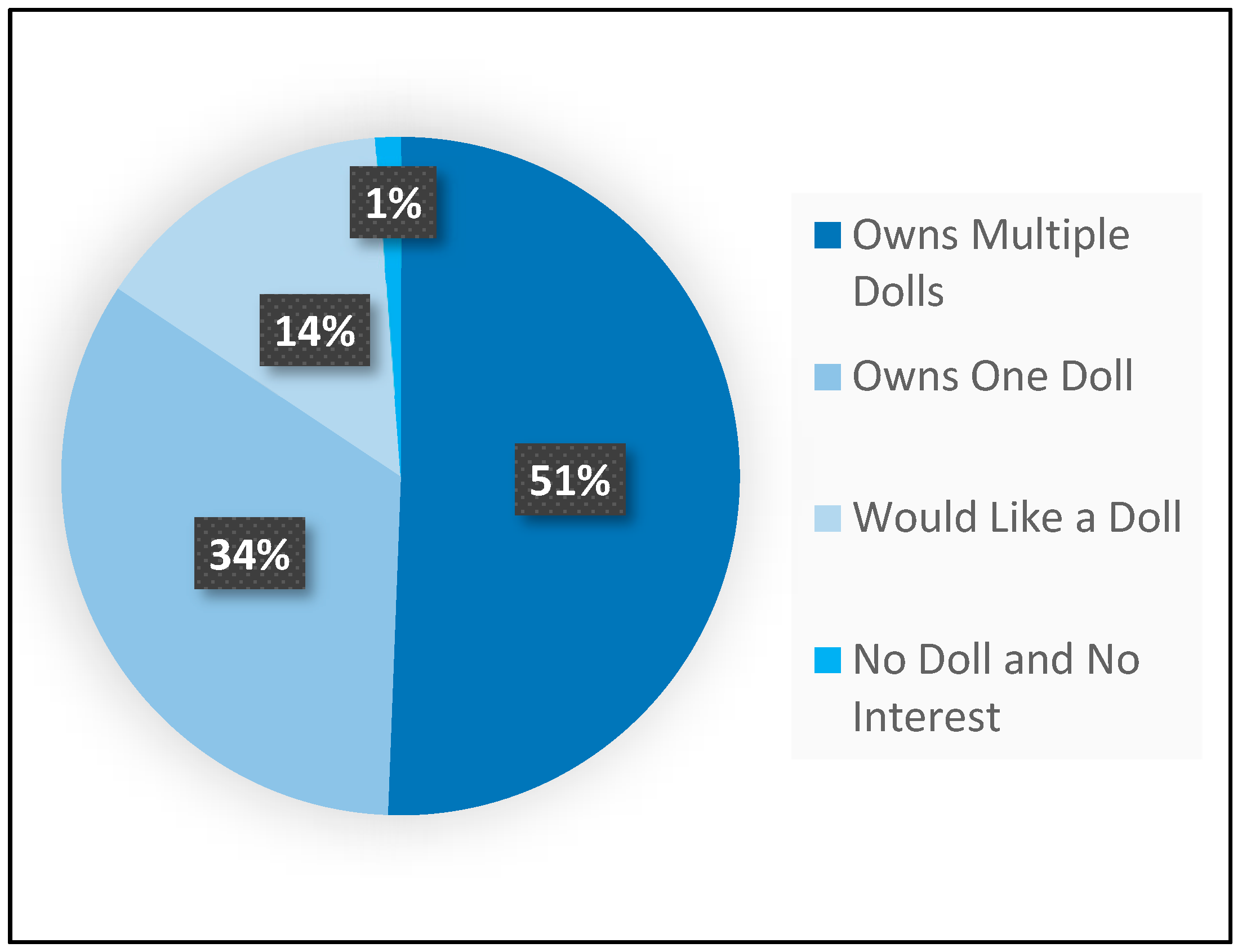

3.1. Quantitative

3.2. Qualitative Results

3.2.1. Sex

“We make love a few times a week at night, in bed. Just like any normal couple does.”

“As far as intimacy goes, nothing out of the ordinary here. Fairly traditional. Nothing outrageously kinky …”

“Prefer their realism instead of a fleshlight or other masturbation type device, or my hand.”

“It is there, always, every day, every hour, every minute. Available.”

“You always have a safe outlet for sexual energy, and a compliant partner for kinks/fetishes that may be too much for living partners.”

3.2.2. Better Alternative to Real Relationships

“In real life women have fewer redeeming qualities. Relationships with dolls are superior.”

“While I enjoy the company of women, I don’t feel like putting in the time and effort that is required to make a relationship work. As such, I have purchased a doll in order to fulfil my sexual needs as well as to be a companion until I find someone worth my time.”

“They give me all the things a biological female won’t, and without any of the risks associated with women.”

“No STD, or babies. Sex on demand, freedom of desire. No one’s feelings, or anus gets hurt. Not having to deal with neurosis, or self-esteem issues. No divorce, and losing half your shit every 10 years. Most of them are hotter than I could hope to entertain at my age.”

“It’s a known. She won’t rob me blind. She won’t give me some horrible STD. She is non-judgmental. She isn’t going to go nuts if the house is a mess/not perfect. If I fart she won’t freak out. She is never jealous. She is not mean. She would never make fun of me. She won’t tell me who I can’t have as a friend.”

“No luck with women (I’m easy on the eyes, great personality, just seem to get caught up in the wrong type).”

“A partner that can be ignored for as long as wanted without feeling bad.”

“You essentially get this ageless perfect girl who will love you unconditionally and never be too busy for you.”

“You can have the ‘girl’ of your dreams.”

3.2.3. Mental Health and Therapeutic Benefits

“Physical human contact has always given me a lot of anxiety, but now just the thought of it makes me feel like I’m going to have a panic attack. I felt lonely and very depressed, but did not want the burden of a relationship. And then I began to believe there was a third option in-between together and alone. My doll is […] a safe where I lock away the parts of me that are too vulnerable for the real world.”

“I live with mental illness—bipolar disorder. I decided to see if this doll might help me create the true life I always wanted. She has done that for me and so much more.”

3.2.4. Hobby and Art Form (Photography)

“I have five [dolls] and another on order. One, my first, I view as a synthetic partner, and the others have joined us mostly to be photographic models and brighten up my home.”

“I like to pose, dress, and take pictures of her.”

“I have always loved dolls of all shapes, sizes, and materials. I collect porcelain dolls, ball-jointed dolls, Blythe and other children’s dolls, and lifelike love dolls.”

“They are great for photography, practicing make-up, and testing outfits.”

3.2.5. Interaction with Dolls

“Besides the obvious (sexual penis to vagina intercourse), we spend a lot of time kissing (“making out”), I give her massages, perform oral sex on her, I groom her (cleaning her skin, fixing and combing her hair).”

“Cuddling and lying in bed together is a favourite. I also enjoy hugging, kissing, and exploring her body.”

3.2.6. Emotional Intimacy and Communication

“A typical conversation when arriving home would be me getting into bed, waking her up, and her telling me that she missed me and she loves me. She’ll ask me to cuddle with her and tell her about my day. Sometimes she’ll ask me to help her change, or to brush/braid/play with her hair. I then ask her what she dreamed about while I was gone, and she tells me. Sometimes she has beautiful dreams, and sometimes she has terrible nightmares. But she always knows she’ll be okay, because I’ll be there when she wakes up.”

3.2.7. Robotic Dolls

“I think this prospect is exciting and the way forward, I wish this was something available to Sarah right now, sometimes I wish she could talk to me, in fact she already has in my dreams more than once!”

“YES!! The ultimate in realism would be the doll’s movement, reaction, and warmth during sex and cuddling.”

“Yes, as long as they had an extremely basic AI that only gave them the ability to move on their own and have very limited conversations. I think it would be very unethical to give a doll more awareness than that. For my doll to be able to grip back when I hold her hand or run her fingers through my hair I think would be amazing, though. However, if you offered me a robotic doll in exchange for my current doll, I would say no immediately because she means too much to me.”

“Only if it were not fully AI. If it could respond around certain parameters that I had control over programming, sure. But if we move towards conscious AI and free will in robots, then that defeats the purpose. I want my doll to live according to my fantasy. Selfish I know. If the doll develops a will, then there needs to be consent, and we’re back to relationships with real women.”

4. Discussion

“We cuddle on the couch and watch TV together. We sleep next to each other. I write her love letters and read them to her. We pose together for pictures. I talk to her like I would a lover, sharing experiences and thoughts and sweet nothings”.

Allodoll: A humanoid doll, typically of substantial realism, used as a means of replacing, or substituting, a necessary or desired social relationship. Allodolls may or may not offer sexual functionality, but crucially they must serve at least one significant, non-sexual, purpose for their owner. They can be infantile or adult in appearance, and may be static, or incorporate robotic technologies, speech functionality, or animation. Allodolls facilitate a fabricated kinship, fantasy partnership, or other form of parasocial relationship.

4.1. Doll Owners’ Views on Robotic Dolls

4.2. Future Applications: The Rise of the Allodoll

“Two years ago I began to feel lonely. My synthetic ladies certainly help in this regard as they have a strong presence so I basically feel like someone is here with me.”

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Krizia, P. The Synthetic Hyper Femme: On Sex Dolls, Fembots, and the Futures of Sex; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing: San Diego, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- SiliconWives.Com. The 2018 Sex Doll Buyer’s Guide. Available online: https://www.siliconwives.com/blogs/news/2017-sex-doll-buyers-guide (accessed on 6 May 2018).

- Real Love Sex Dolls. TPE Sex Dolls. Available online: https://reallovesexdolls.com/tpe-sex-dolls/ (accessed on 11 May 2018).

- Finest Sex Dolls. Finest Sex Dolls: About. Available online: https://esexdolls.com/pages/about-us-silicone-sex-dolls (accessed on 6 May 2018).

- My Silicone Love Doll. Extra Sex Doll Heads. Available online: https://www.mysiliconelovedoll.com/product-category/accessories/extra-sex-doll-heads/ (accessed on 4 May 2018).

- Valverde, S.H. The Modern Sex Doll-Owner: A Descriptive Analysis; Cal Poly State University: San Luis Obispo, CA, USA, 2012; Available online: http://digitalcommons.calpoly.edu/theses/849 (accessed on 28 May 2018).

- Furnham, A.; Reeves, E. The Relative Influence of Facial Neoteny and Waist-to-Hip Ratio on Judgements of Female Attractiveness and Fecundity. Psychol. Health Med. 2006, 11, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naini, F.B. Facial Aesthetics: Concepts and Clinical Diagnosis; Wiley Blackwell Publishing: Chichester, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, D. Universal Allure of the Hourglass Figure: An Evolutionary Theory of Female Physical Attractiveness. Clin. Plast. Surg. 2006, 33, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson, I. The Future of Sex Report: The Rise of the Robosexuals. Available online: http://graphics.bondara.com/Future_sex_report.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2018).

- Levy, D. Love & Sex with Robots; Duckworth Publishers: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Realbotix. Realbotix Software. Available online: https://realbotix.com (accessed on 3 June 2018).

- Inquirer.Net. ‘Call Me Baby’: Talking Sex Dolls Fill a Void in China. Available online: http://technology.inquirer.net/72107/call-baby-talking-sex-dolls-fill-void-china (accessed on 8 May 2018).

- Nast, H.J. Into the arms of dolls: Japan’s declining fertility rates, the 1990s financial crisis and the (maternal) comforts of the posthuman. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2016, 6, 758–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, K. Campaign against Sex Robots. Available online: https://campaignagainstsexrobots.org/about/ (accessed on 9 May 2018).

- Ehrenkranz, M. What Our Violent Obsession with Sex Robots Reveals about Us. MIC, 2016. Available online: https://mic.com/articles/162206/westworld-rape-violence-abuse-sexism-sex-robots-consent-what-it-says-about-us#.JuXeKB3p5 (accessed on 9 June 2018).

- Darling, K. Kate Darling: Mistress of Machines. Available online: http://www.katedarling.org (accessed on 7 May 2018).

- Cox-George, C.; Bewley, S.I. Sex Robot: The Health Implications of the Sex Industry. BMJ Sex Reprod. Health 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, A. The Sex Doll: A History; McFarland & Company: Jefferson, NC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Knox, D.; Huff, S.; Chang, I.J. Sex Dolls—Creepy or Healthy?: Attitudes of Undergraduates. J. Posit. Sex. 2017, 3, 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Giles, D.C. Parasocial Interaction: A Review of the Literature and a Model for Future Research. Media Psychol. 2002, 4, 279–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miah, A. A Critical History of Posthumanism. In Medical Enhancement and Posthumanity; Gordijn, B., Chadwick, R., Eds.; Springer: Basingstoke, UK, 2008; pp. 71–94. [Google Scholar]

- Haraway, D.J. A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology and Socialist Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century; University of Michigan: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Downey, G.L.; Dumit, J.; Williams, S. Cyborg Anthropology. J. Soc. Cult. Anthr. 1995, 10, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, B. Fields of Post-Human Kinship. In European Kinship in the Age of Biotechnology, 1st ed.; Edwards, J., Salazar, C., Eds.; Berghan Books: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 162–179. [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester, D.; Furman, W. The Development of Companionship and Intimacy. Child Dev. 1987, 58, 1103–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.; Abney, K.; Bekey, G.A.; Arkin, R.C. Robot Ethics: The Ethical and Social Implications of Robotics; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schneer, J.A.; Reitman, F. Effects of Alternate Family Structures on Managerial Career Paths. Acad. Manag. J. 2017, 36, 830–843. [Google Scholar]

- Parreñas, R.S. Mothering from a Distance: Emotions, Gender and Intergenerational Relations in Filipino Transnational Families. Fem. Stud. 2001, 27, 361–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, J.D. Economy, Family, and Remarriage: Theory of Remarriage and Application to Preindustrial England. J. Fam. Issues 1980, 1, 479–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duck, S. Personal Relations 4: Dissolving Personal Relationships; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg, R.M. The Plight of Transnational Latina Mothers: Mothering from a Distance. Migr. Health 2010, 2, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Riggs, D.W.; Peel, E. Critical Kinship Studies: An Introduction to the Field; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Stock, M.J. British Robot Helping Autistic Children with Their Social Skills. Science News, 2017. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-britain-autism-robots-idUSKBN1721QL (accessed on 10 June 2018).

- Walker, R. Hyperreality Hobbying. New York: The New York Times Magazine. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2005/02/20/magazine/hyperreality-hobbying.html (accessed on 9 May 2018).

- White, M. Babies Who Touch You: Reborn Dolls, Artistis, and the Emotive Display of Bodies on eBay. In Political Emotions: New Agendas in Communication; Staiger, J., Cvetkovich, A., Reynolds, A., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pike, K.L. Language in Relation to a Unified Theory of the Structure of Human Behaviour; Summer Institute of Linguistics: Dallas, TX, USA, 1954; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bentley, G.R.; Mace, R. (Eds.) Substitute Parents: Biological and Social Perspectives on Alloparenting in Human Societies; Berghan: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Riedman, M.L. The Evolution of Alloparental Care and Adoption in Mammals and Birds. Q. Rev. Boil. 1982, 57, 405–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GOV.UK. PM Commits to Government-Wide Drive to Tackle Loneliness. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/pm-commits-to-government-wide-drive-to-tackle-loneliness (accessed on 29 April 2018).

- PARO. PARO Therapeutic Robot. Available online: http://www.parorobots.com/ (accessed on 10 May 2018).

- Intuition Robotics. Elli.Q: Keeping Older Adults Active and Engaged. Available online: https://elliq.com (accessed on 6 May 2018).

- Harlow, H.F. The Nature of Love. Am. Psychol. 1958, 13, 673–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, M.L.; Syrdal, D.S.; Dautenhahn, K.; Boekhorst, R.T.; Koay, K.L. Avoiding the Uncanny Valley: Robot Appearance, Personality and Consistency of Behaviour in an Attention-Seeking Home Scenario for a Robot Companion. Auton. Robot. 2008, 24, 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt-Lunstad, J.; Smith, T.B.; Layton, J.B. Social Relationships and Mortality Risk: A MetaAnalytic Review. J. PLoS Med. 2010, 7, e1000316. [Google Scholar]

- Lefever, S.; Dai, M.; Matthíasdóttir, A. Online data collection in academic research: Advantages and limitations. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2006, 38, 574–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Variable | Number of Participants | Percentage of Participants |

|---|---|---|

| Gender of Participants | ||

| Male | 75 | 90.4 |

| Female | 3 | 3.6 |

| Gender Fluid | 2 | 2.4 |

| Trans-Man (Transgender Male) | 1 | 1.2 |

| Trans-Woman (Transgender Female) | 1 | 1.2 |

| Other | 1 | 1.2 |

| TOTAL | 83 | 100 |

| Sexual Orientation | ||

| Heterosexual | 73 | 88 |

| Bisexual | 6 | 7.2 |

| Asexual | 1 | 1.2 |

| Other | 3 | 3.6 |

| TOTAL | 83 | 100 |

| Age | ||

| 17 or Under | 0 | 0 |

| 18–29 | 11 | 13.3 |

| 30–44 | 23 | 27.7 |

| 45–59 | 38 | 45.8 |

| 60–74 | 10 | 12 |

| 75+ | 1 | 1.2 |

| TOTAL | 83 | 100 |

| Relationship Status | ||

| Single | 37 | 44.6 |

| Married or Domestic Partnership | 19 | 22.9 |

| Divorced | 11 | 13.3 |

| In a Relationship | 8 | 9.6 |

| Widowed | 2 | 2.4 |

| Separated | 2 | 2.4 |

| Other | 4 | 4.8 |

| TOTAL | 83 | 100 |

| Location of Participants | ||

| North America | 58 | 70 |

| Europe | 20 | 24 |

| Asia | 1 | 1.2 |

| Australasia | 1 | 1.2 |

| Other (Multiple) | 3 | 3.6 |

| TOTAL | 83 | 100 |

| Area of Residence | ||

| City | 44 | 53.7 |

| Town | 24 | 29.3 |

| Rural | 10 | 12.2 |

| Village | 2 | 2.4 |

| Countryside | 2 | 2.4 |

| TOTAL | 82 | 100 |

| Living Arrangements | ||

| Alone | 41 | 49.4 |

| Partner/Spouse | 21 | 25.3 |

| Children | 9 | 10.8 |

| Parents | 7 | 8.4 |

| House/Flat Share | 4 | 4.8 |

| Friends | 2 | 2.4 |

| Other | 8 | 9.6 |

| Highest Education Level | ||

| Up to GCSE */Equivalent | 12 | 14.5 |

| Apprenticeship/Practical Skills | 3 | 3.6 |

| A-Levels †/Equivalent | 3 | 3.6 |

| Further Education | 21 | 25.3 |

| Higher Education i.e., University | 25 | 30.1 |

| Postgraduate i.e., Masters | 14 | 16.9 |

| Other | 5 | 6 |

| TOTAL | 83 | 100 |

| Employment Status | ||

| Employed | 41 | 49.4 |

| Retired | 16 | 19.3 |

| Self-Employed | 14 | 16.9 |

| A Student | 3 | 3.6 |

| Unemployed, Looking for Work | 3 | 3.6 |

| Unable to Work | 3 | 3.6 |

| Part-time Employed | 1 | 1.2 |

| Military | 1 | 1.2 |

| Homemaker | 1 | 1.2 |

| TOTAL | 83 | 100 |

| Income Bracket | ||

| Under 15k | 16 | 19.8 |

| 15–29k | 17 | 21 |

| 30–44k | 6 | 7.4 |

| 45–59k | 9 | 11.1 |

| 60–99k | 15 | 18.5 |

| 100k+ | 9 | 11.1 |

| Prefer Not to Say | 9 | 11.1 |

| TOTAL | 81 | 100 |

| Doll Community Variable | Number of Participants | Percentage of Participants |

|---|---|---|

| Time Using Forums | ||

| 0–1 Months | 7 | 8.5 |

| 2–5 Months | 15 | 18.3 |

| 6 Months–1 Year | 13 | 15.9 |

| 2–5 Years | 30 | 36.6 |

| More Than 5 Years | 15 | 18.3 |

| Not a Member of an Online Group | 2 | 2.4 |

| TOTAL | 82 | 100 |

| Reasons for Forum Use | ||

| Doll Maintenance | 57 | 68.7 |

| Sharing Photographs | 49 | 59 |

| Meeting Other Doll Owners | 45 | 54.2 |

| Wanting to Buy a Doll | 37 | 44.6 |

| Friendship | 31 | 37.3 |

| Wanting to Sell a Doll | 3 | 3.6 |

| Other | 19 | 22.9 |

| Doll Description Variable | Number of Participants | Percentage of Participants |

|---|---|---|

| How Doll Owners View Their Dolls | ||

| Woman | 57 | 69.5 |

| Other | 10 | 12.2 |

| I Don’t Have a Doll | 7 | 8.54 |

| Girl | 6 | 7.32 |

| Man | 1 | 1.22 |

| Not Human | 1 | 1.22 |

| TOTAL | 82 | 100 |

| Core Relationship Elements | ||

| Sexual | 64 | 77.1 |

| Companionship | 47 | 56.6 |

| Loving | 39 | 47 |

| Emotional | 36 | 43.4 |

| Friendship | 25 | 30.1 |

| Kink/Fetish | 14 | 16.9 |

| Other | 14 | 16.9 |

| I Don’t Have a Doll | 11 | 13.3 |

| General Family | 7 | 8.4 |

| I Am Their Parent | 1 | 1.2 |

| How Doll Owners Refer to Their Dolls | ||

| Lover | 35 | 43.8 |

| Companion | 34 | 42.5 |

| Toy | 25 | 31.3 |

| Girl/Boyfriend | 17 | 21.3 |

| Friend | 16 | 20 |

| Other | 13 | 16.3 |

| Wife/Husband | 12 | 15 |

| Prostitute | 3 | 3.8 |

| Child | 2 | 2.5 |

| What Attracts Owners to Their Doll | ||

| Realism | 62 | 75.6 |

| Body Type | 57 | 69.5 |

| Good Quality | 41 | 50 |

| Wanting Companionship | 36 | 43.9 |

| Low Cost | 24 | 29.3 |

| Sexual Performance | 20 | 24.4 |

| Customisability | 18 | 22 |

| Other | 13 | 15.9 |

| Lack of Realism | 4 | 4.9 |

| Noise | 1 | 1.2 |

| Question Posed | Major Themes | Minor Themes | Mentions | n = | Proportion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Why Do You Have a Doll? (Owners with one or more dolls) | Companionship | To Dress Her Up | Care | 60 | 72% |

| For Sex | For Role Play | Work | |||

| Difficulties with Real Relationships | Preferred to a Relationship | Alternative to Child Abuse | |||

| To Aid Masturbation Mental Health | For Home Decoration | Collector/Hobbyist Multifunctional | |||

| Photography | Extension of the Self | ||||

| Why Do You Want a Doll? (Those without a doll, but would like one) | Companionship | Curiosity | 10 | 12% | |

| Difficulties with Real Relationships | Selfish with Alone Time | ||||

| For Sex | Clear Conscience | ||||

| Describe Your Relationship with Your Doll? | Companionship | Love | Activity Partner | 48 | 58% |

| Masturbation/Sex Aid | Platonic | One-Sided | |||

| Romantic | Caregiving | Affectionate | |||

| Physically Close | Supportive | Collecting/Hobby | |||

| Sexual Partners | Therapeutic | Better Than a Real One | |||

| Styling/Modelling | Photography | ||||

| How Are You Intimate with Your Doll? | Sexually | Conversation | Undressing | 47 | 57% |

| Cuddling | Emotionally | Admire Her | |||

| Kissing | Sexually Satisfying Her | Explore Her Body | |||

| Physically Close | Mutual Masturbation | ||||

| Joint Activities | |||||

| Affectionate | |||||

| How Do You Communicate with Your Doll? | Talk to Her | Only During Sex | Using an App | 51 | 61% |

| Through Imagination Physically | Like with a Toy/Pet | In Dreams With Anger | |||

| No Communication | Through Music | ||||

| What Do You Imagine Your Doll Might Say? | General Speech “I Feel Well Treated” | Positive Responses | Mimics Owner Thoughts | 38 | 46% |

| Positive Thoughts of Owner | Speaks Like a Human | Comments on Clothing | |||

| She Doesn’t Speak | Full Conversation | ||||

| Complains | Misses Owner | ||||

| Prefers Silence | |||||

| What Are the Pros of Doll Ownership? | Have the Woman of Your Dreams | Aesthetically Pleasing | Can Explore Fetishes | 62 | 75% |

| Simpler Than Real Relationship | Less Issues than Bio Women | Can Replace Humans | |||

| Sexual Satisfaction | Supportive | ||||

| Improves Mental State | Companionship | ||||

| Owner Always in Control | Sleeping Partner | ||||

| What Are the Cons of Doll Ownership? | Maintenance and Upkeep | Expensive | High Standards | 62 | 75% |

| Not Socially Acceptable | Cold to Touch | No Children | |||

| Can’t Respond | Heavy | Stops You Dating | |||

| Has to Be a Secret | Hard to Store | ||||

| Requires Imagination | |||||

| Unreliable Vendors | |||||

| What Do You Think About Robotic Dolls? | Concerns (Ethics and Costs) | My Doll is Enough | Betters Social Skills | n = 72 | 87% |

| Better Motor and Language Skills | Better Sexual Abilities | Would Need to Consent | |||

| Intrigued/Excited More Realistic | Able to Replace Humans | Personal Safety Risks | |||

| Not Interested | Able to Complete Chores | Could Stop Dating Don’t Want AI |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Langcaster-James, M.; Bentley, G.R. Beyond the Sex Doll: Post-Human Companionship and the Rise of the ‘Allodoll’. Robotics 2018, 7, 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics7040062

Langcaster-James M, Bentley GR. Beyond the Sex Doll: Post-Human Companionship and the Rise of the ‘Allodoll’. Robotics. 2018; 7(4):62. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics7040062

Chicago/Turabian StyleLangcaster-James, Mitchell, and Gillian R Bentley. 2018. "Beyond the Sex Doll: Post-Human Companionship and the Rise of the ‘Allodoll’" Robotics 7, no. 4: 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics7040062

APA StyleLangcaster-James, M., & Bentley, G. R. (2018). Beyond the Sex Doll: Post-Human Companionship and the Rise of the ‘Allodoll’. Robotics, 7(4), 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics7040062