Extended Operational Space Kinematics, Dynamics, and Control of Redundant Non-Serial Compound Robotic Manipulators

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background on Redundant Non-Serial Compound Manipulator Modeling and Control

2.1. Methods Adapted from Redundant Serial Manipulators

2.2. Constrained Operational Space Dynamics

2.3. Redundant Parallel Manipulators

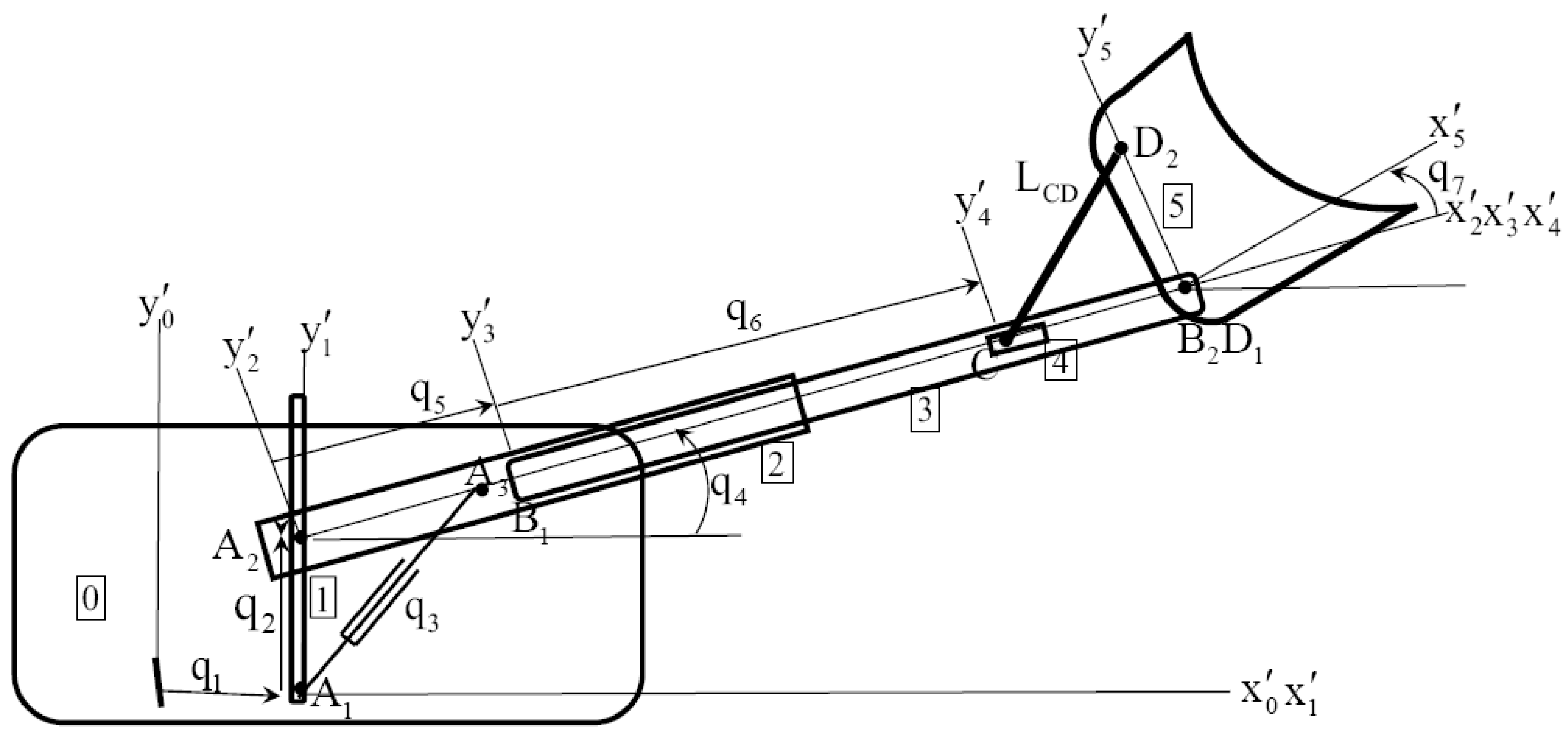

3. A Redundant Non-Serial Compound Material Loader Manipulator

- (1)

- bodies 0, 1, and 2, and slider that define the length of actuator , which is not contained in a joint;

- (2)

- bodies 3, 4, and 5 that define the fixed length of bar are written in algebraic form as follows:

4. Redundant Compound Manipulator Kinematics, Dynamics, and Control

4.1. Basics of Compound Redundant Manipulator Kinematics

4.1.1. Manipulator Configuration Space

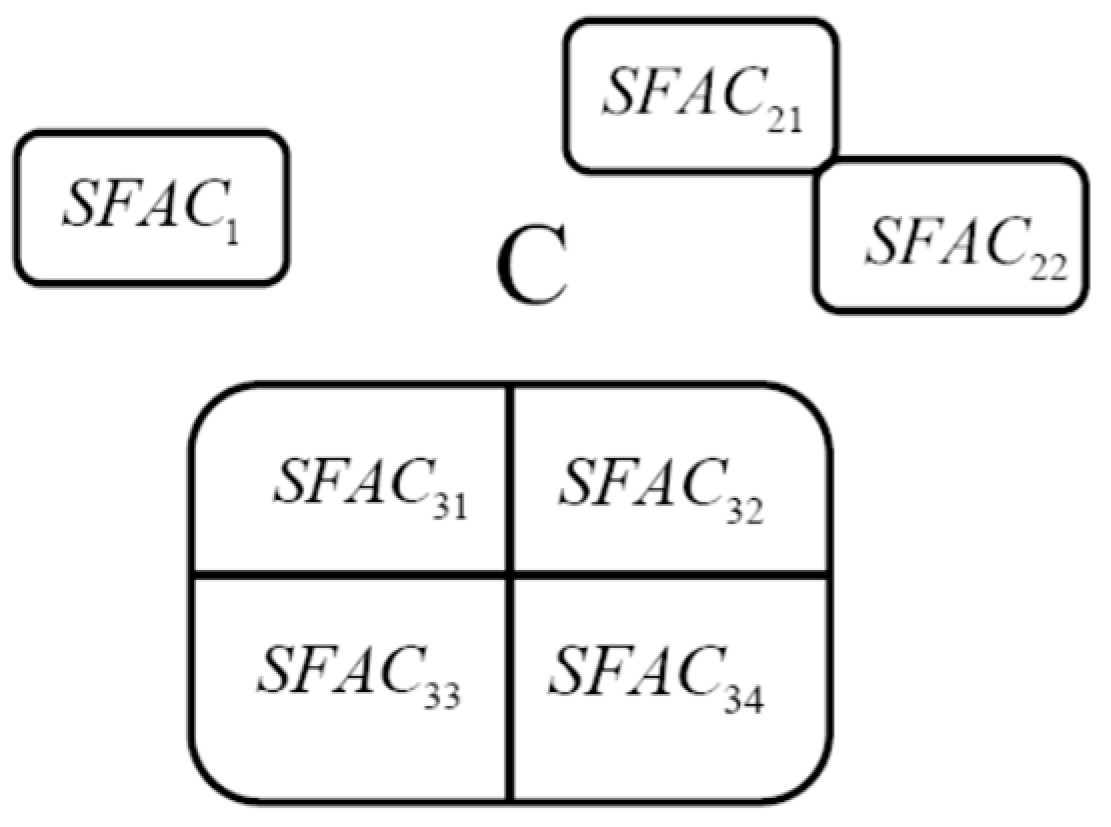

4.1.2. Assembly Components

4.1.3. Forward and Inverse Kinematics

4.1.4. Singularity-Free Assembly Components

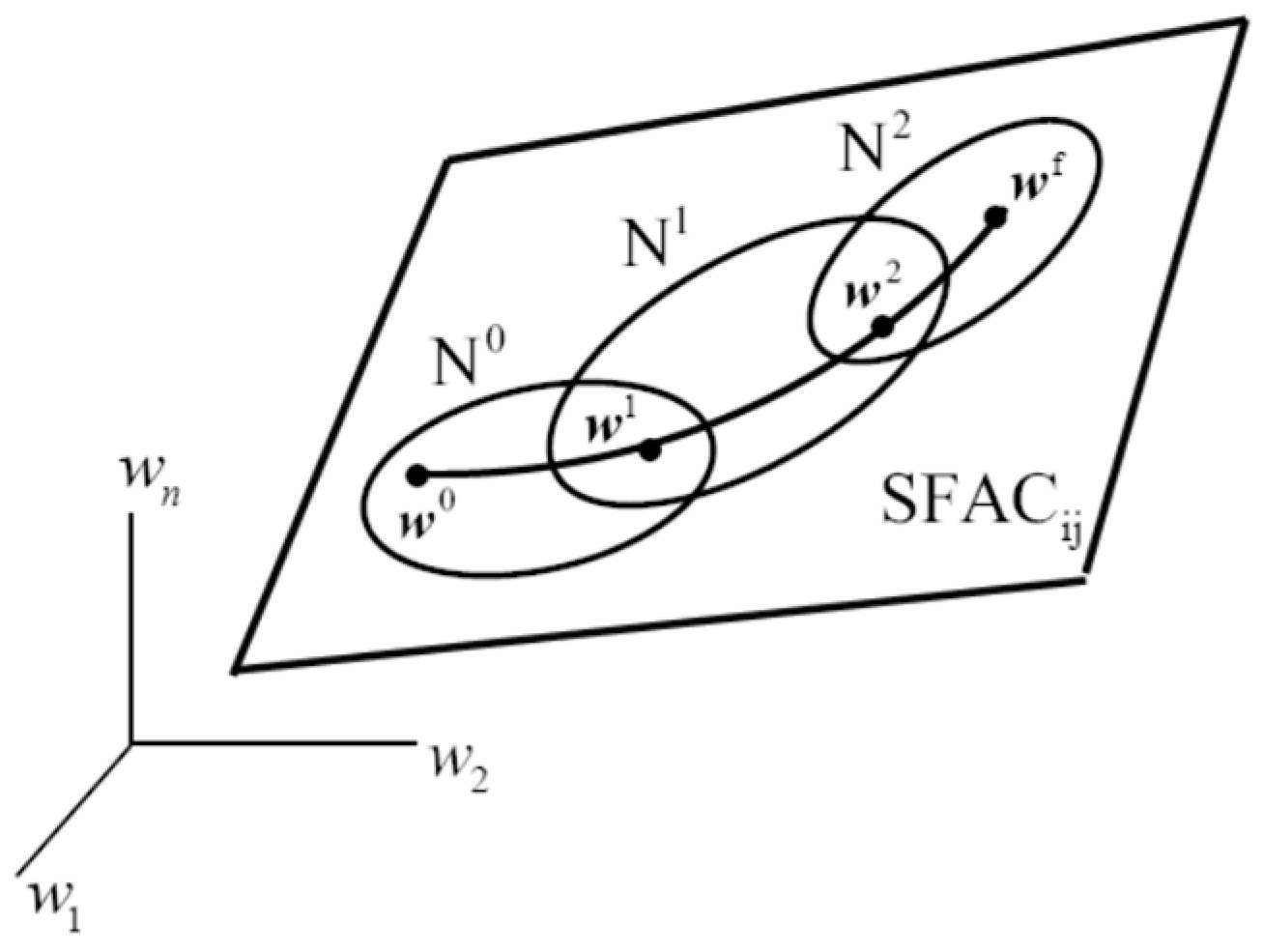

4.1.5. Numerical Construction of a Multi-Valued Inverse Kinematic Mapping

4.2. Compound Manipulator Dynamics

4.2.1. Input Space ODE of Dynamics

4.2.2. Operational Space Velocity and Acceleration Kinematics

4.2.3. Operational Space ODE of Dynamics

4.2.4. Computation of and

5. Material Loader Dynamics and Control

5.1. Material Loader Input and Operational Space Dynamics

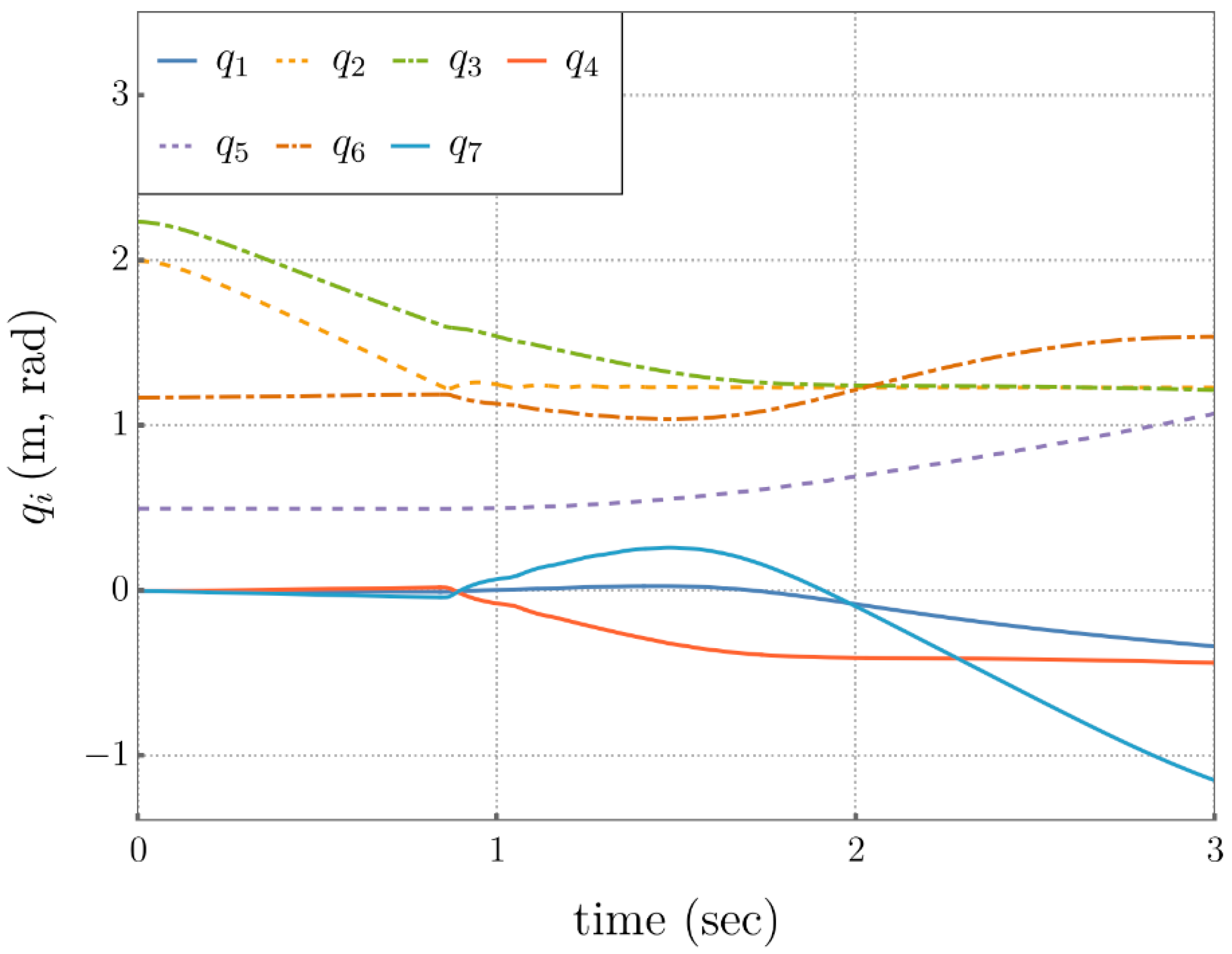

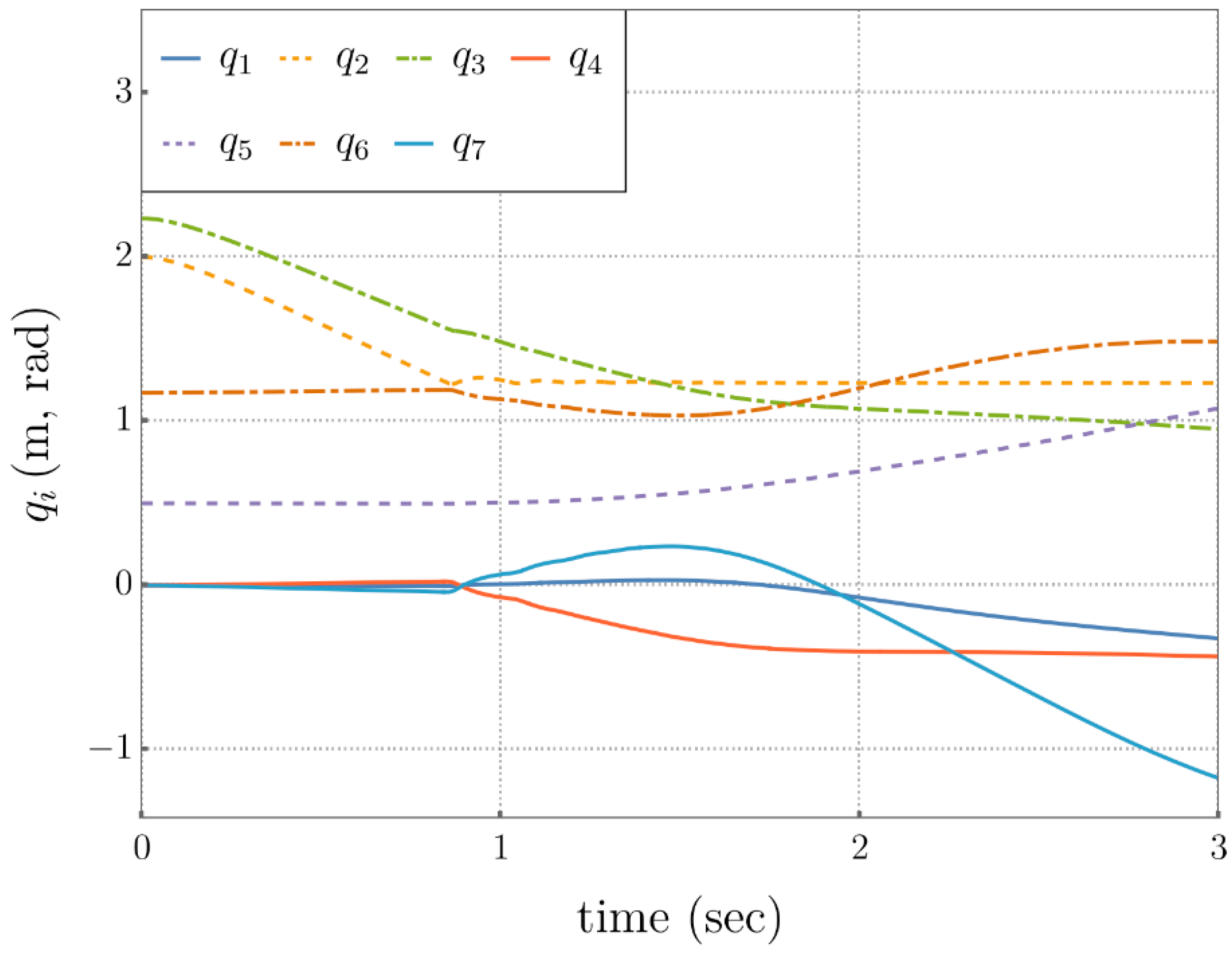

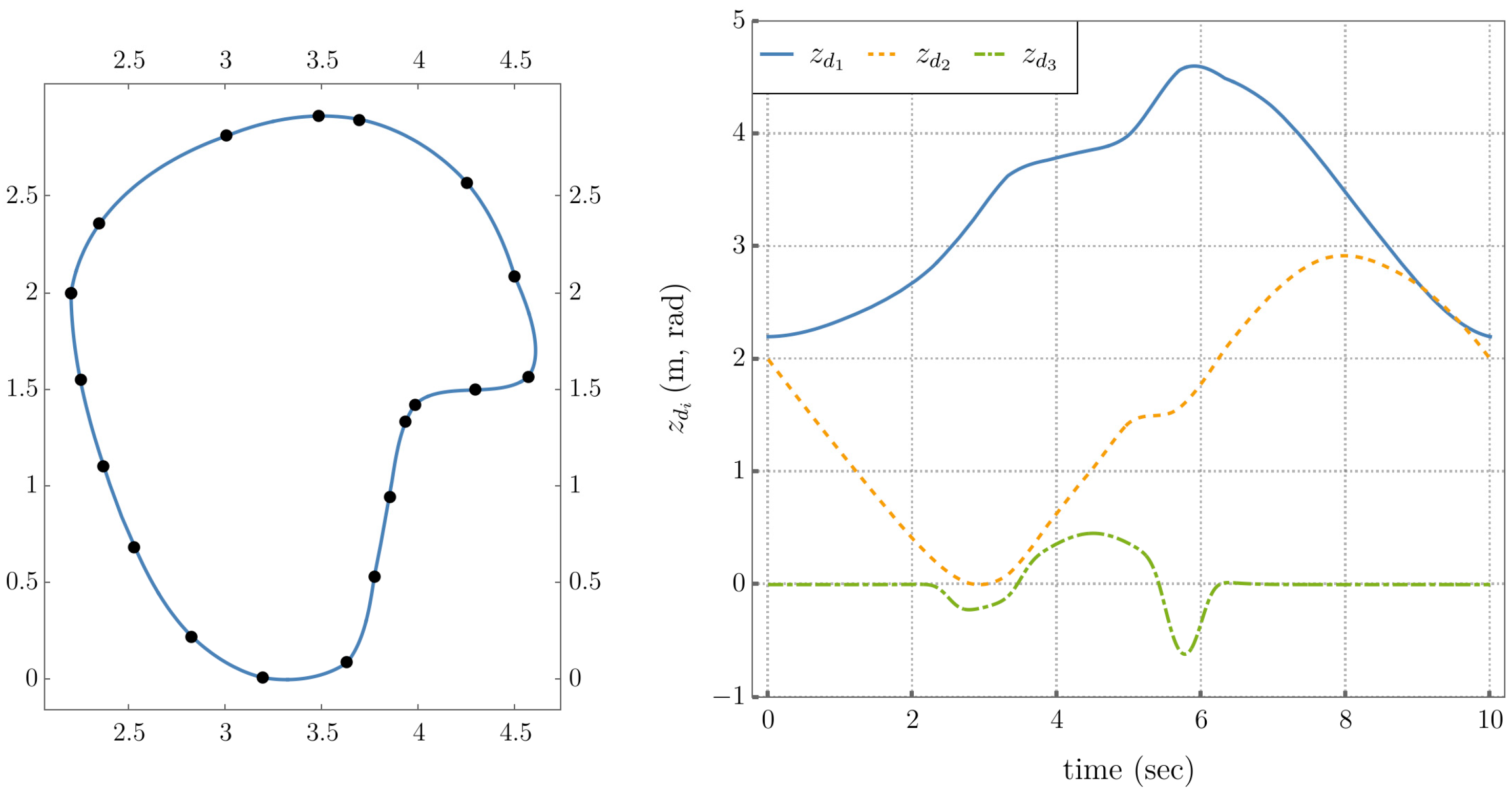

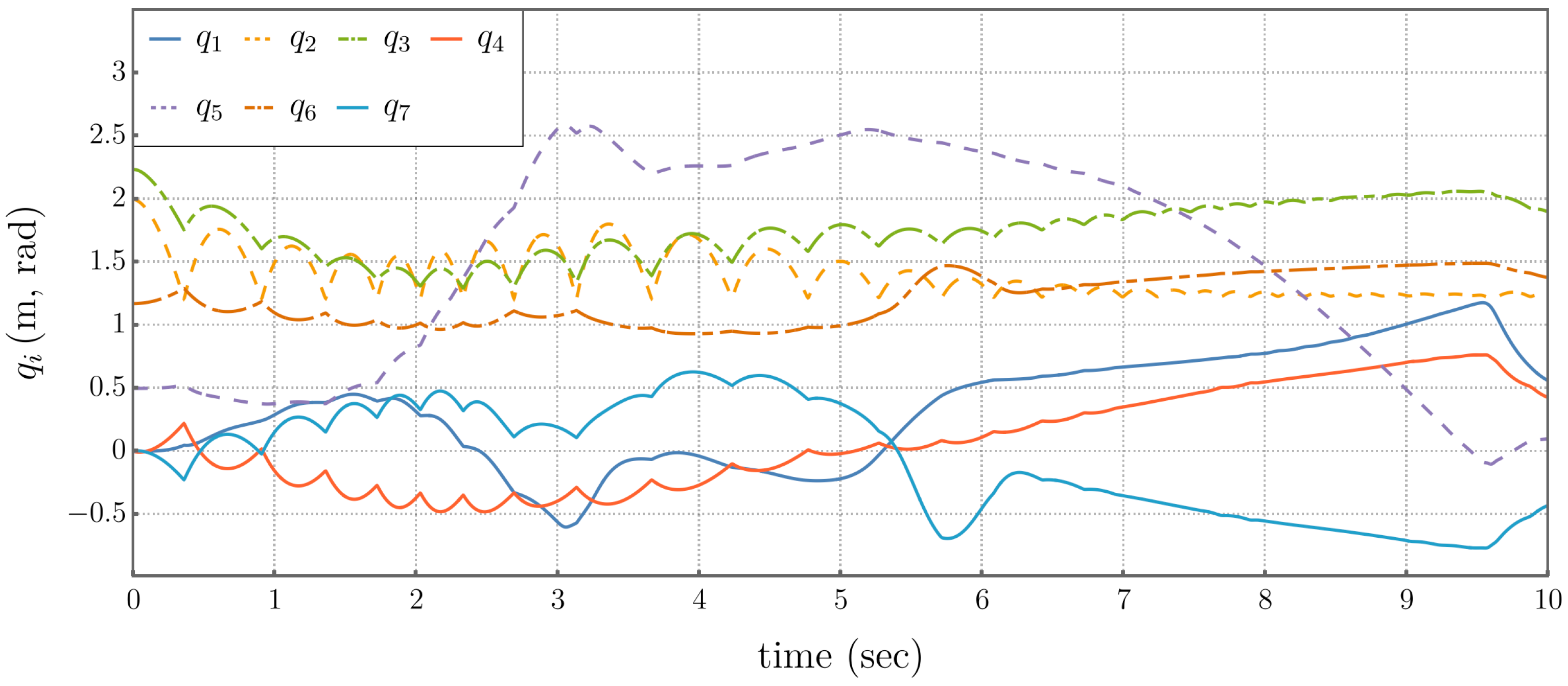

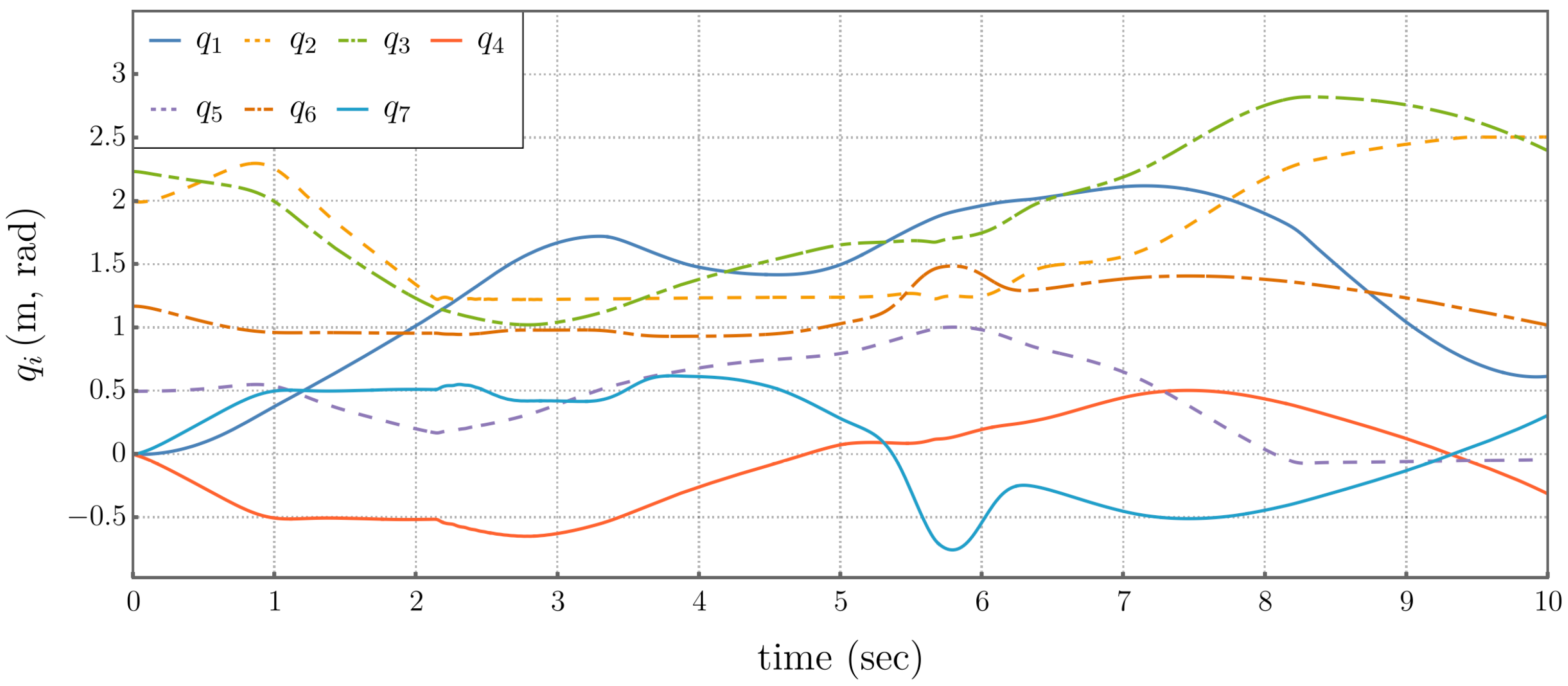

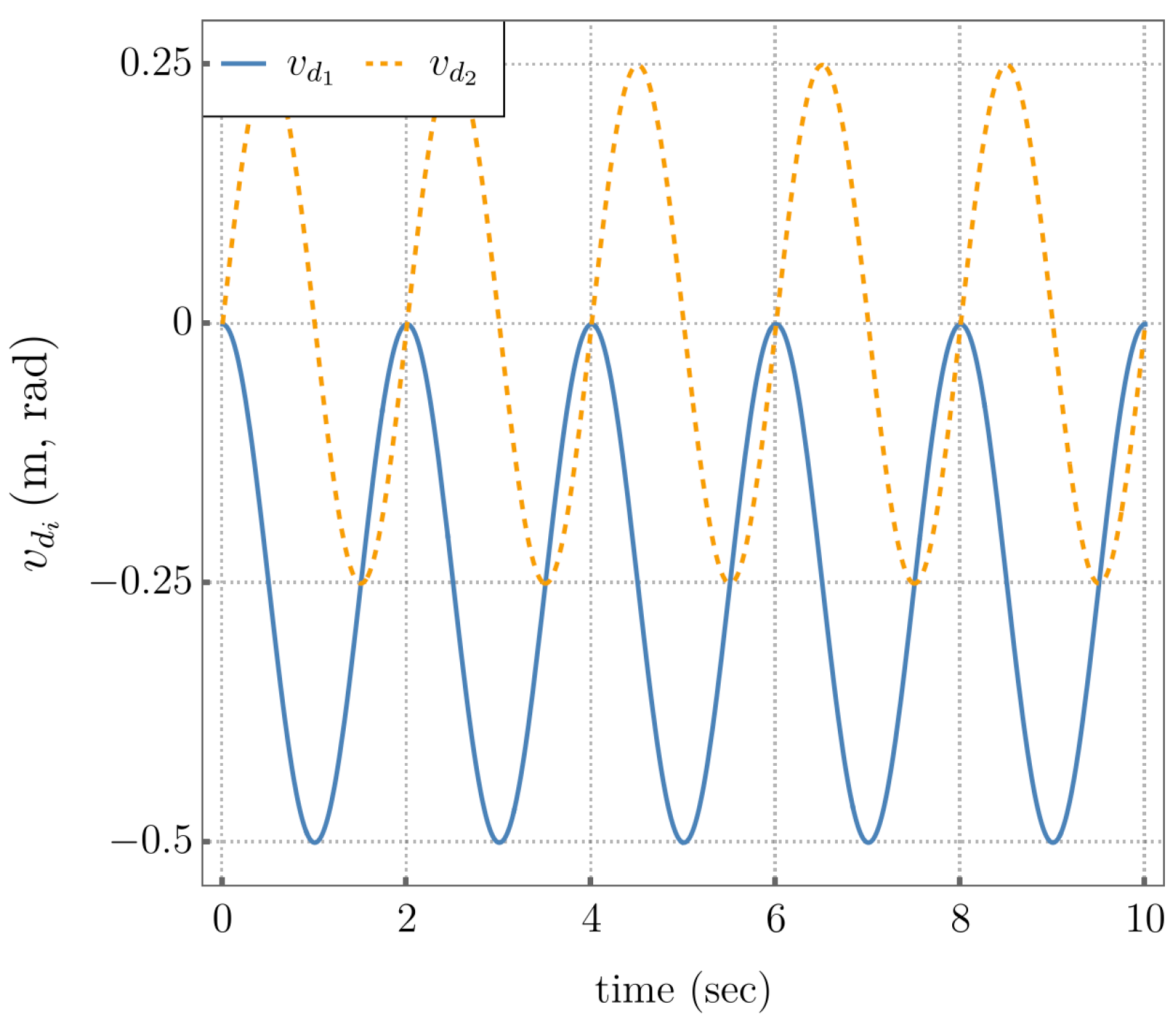

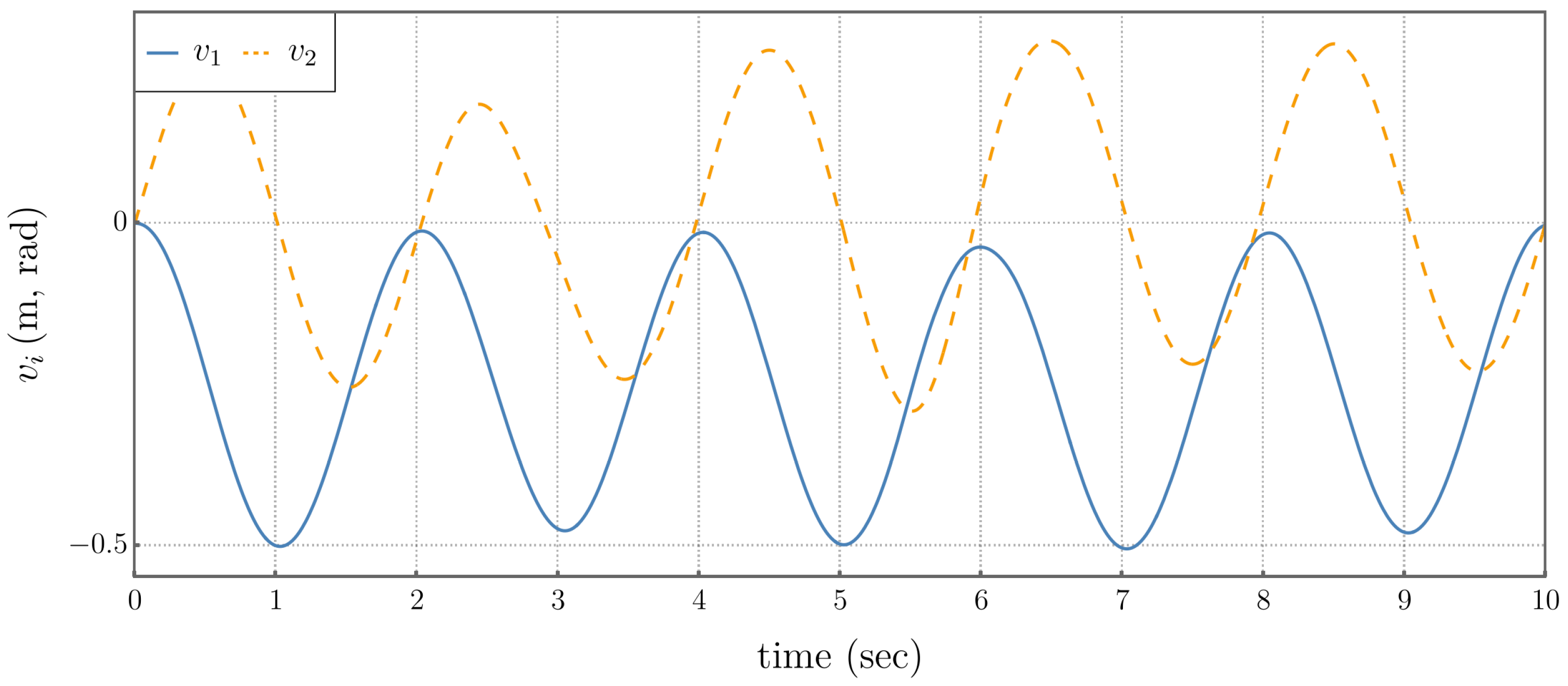

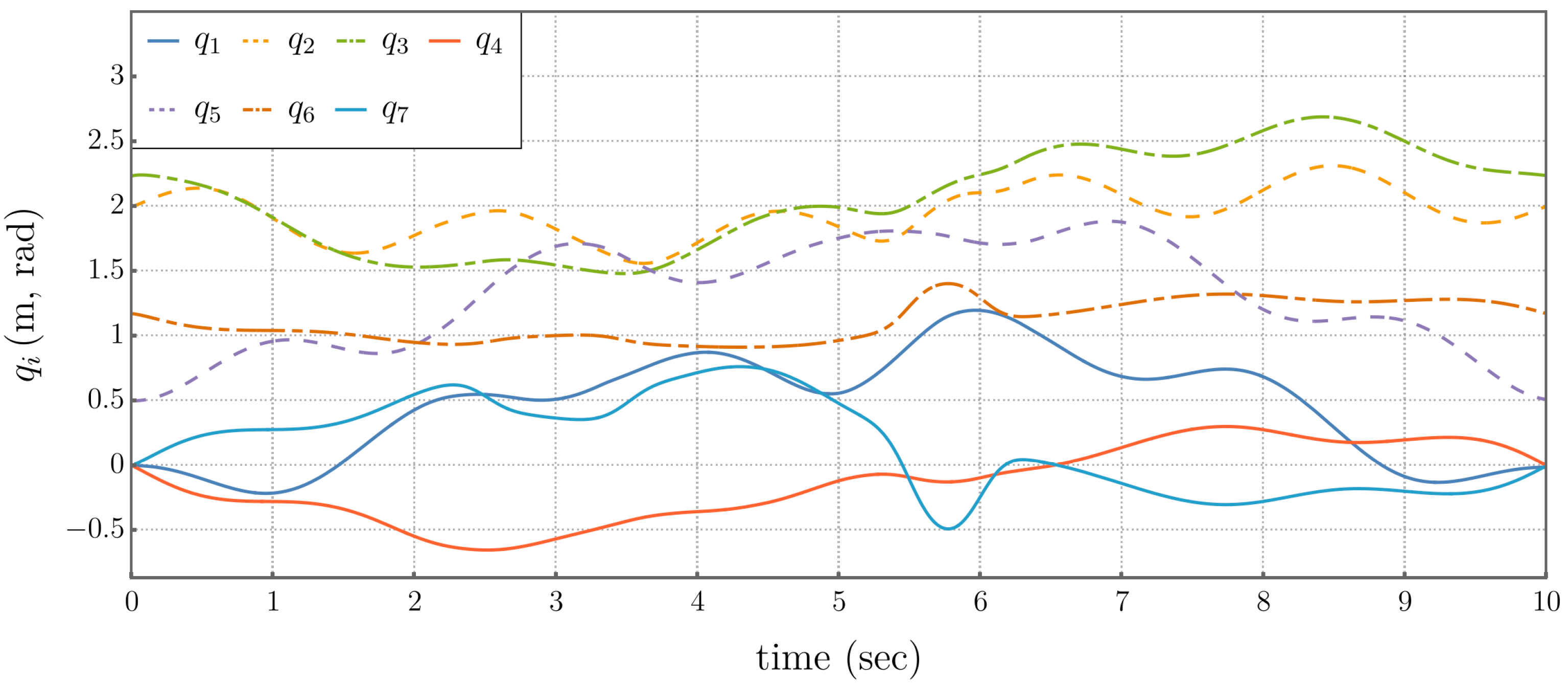

5.2. Tracking Task Trajectory with Kinetic Energy Minimization and Joint Limit Avoidance

5.2.1. Traditional Operational Space Control

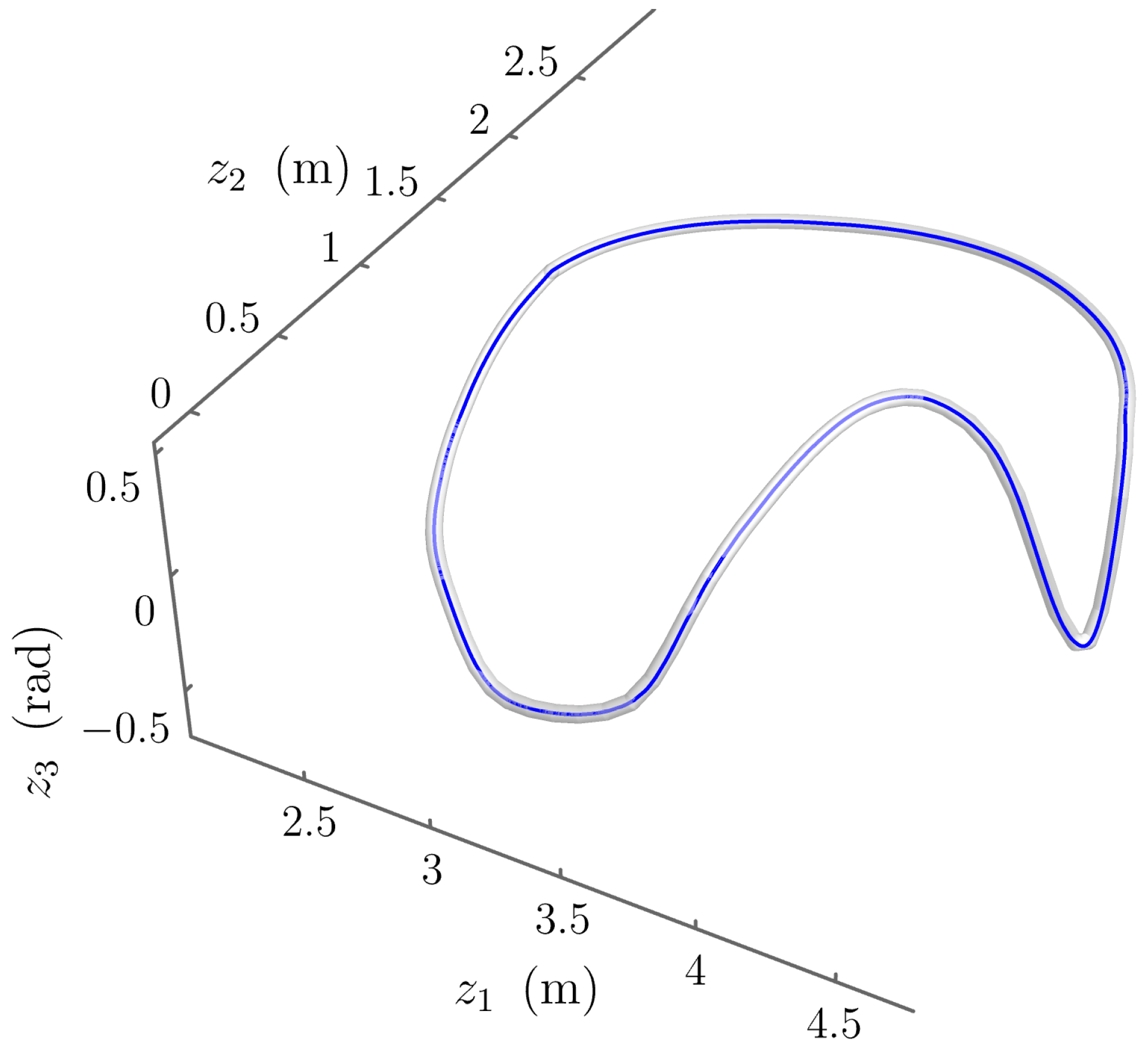

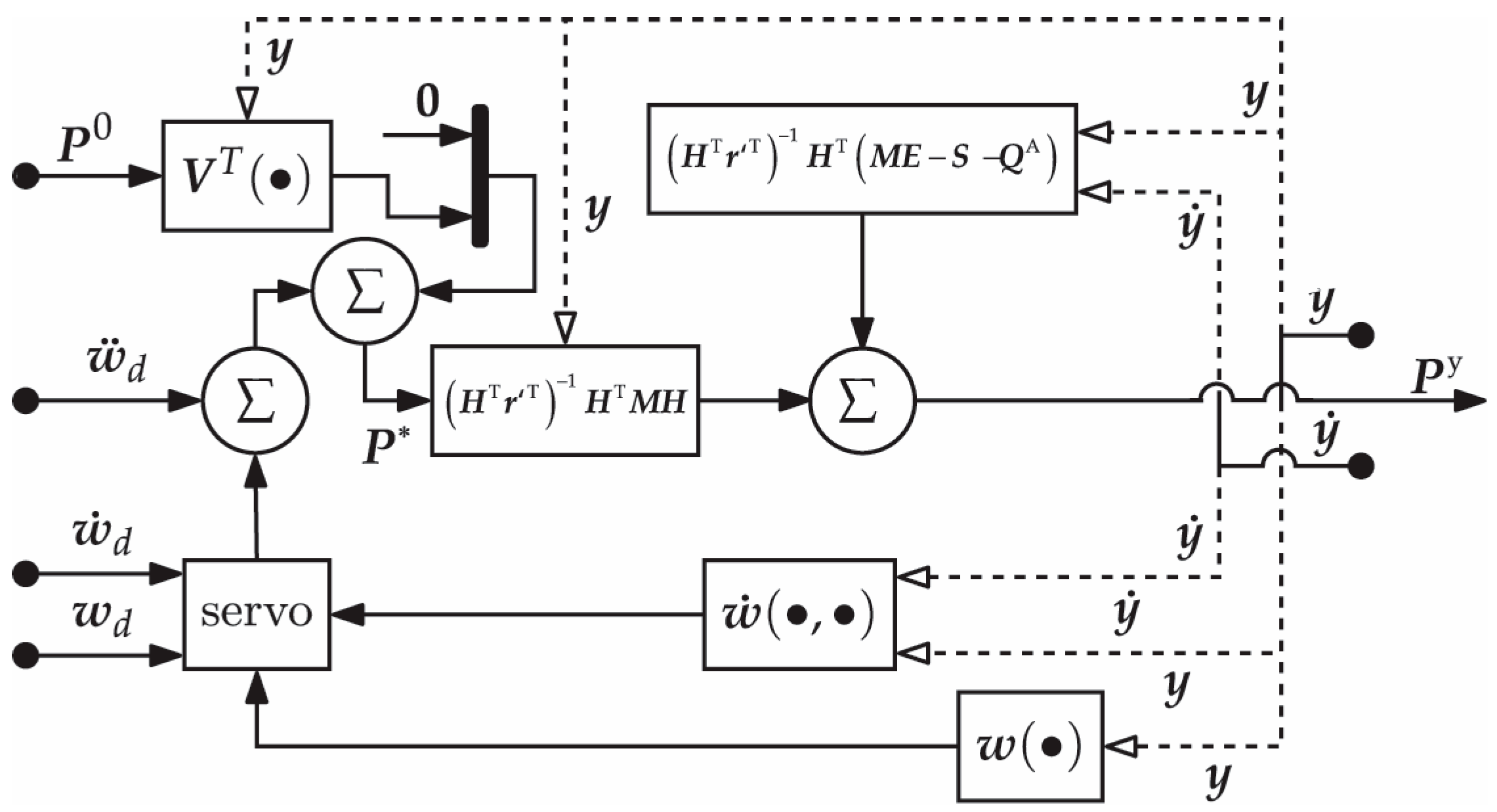

5.2.2. Extended Operational Space Control

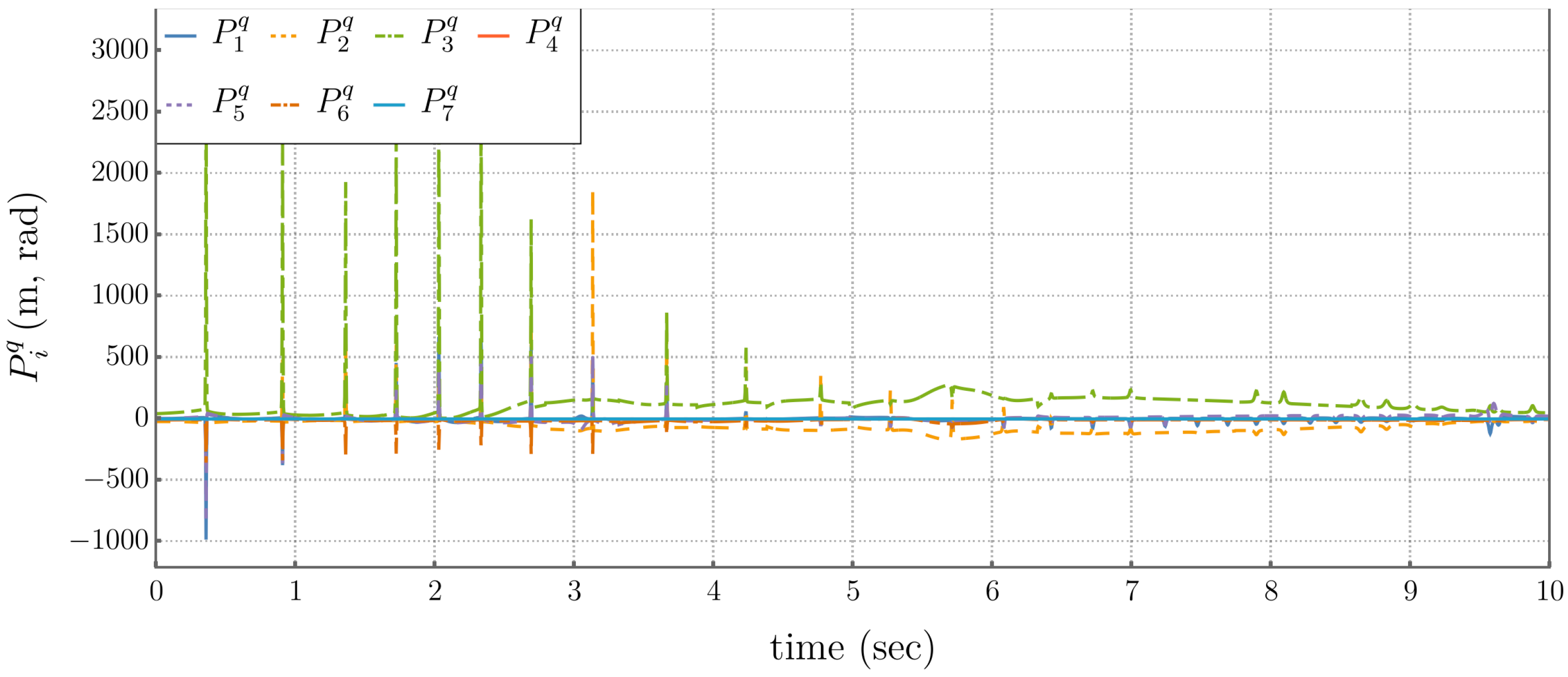

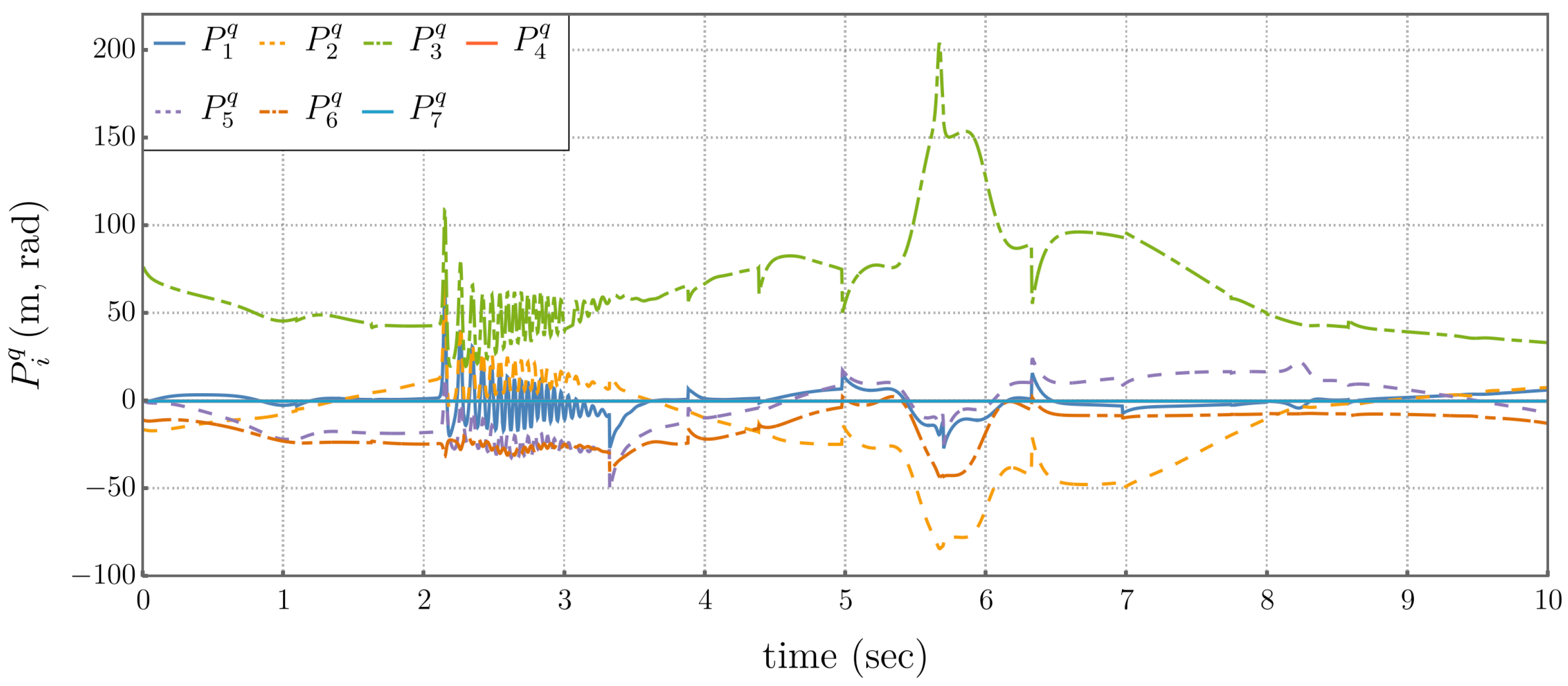

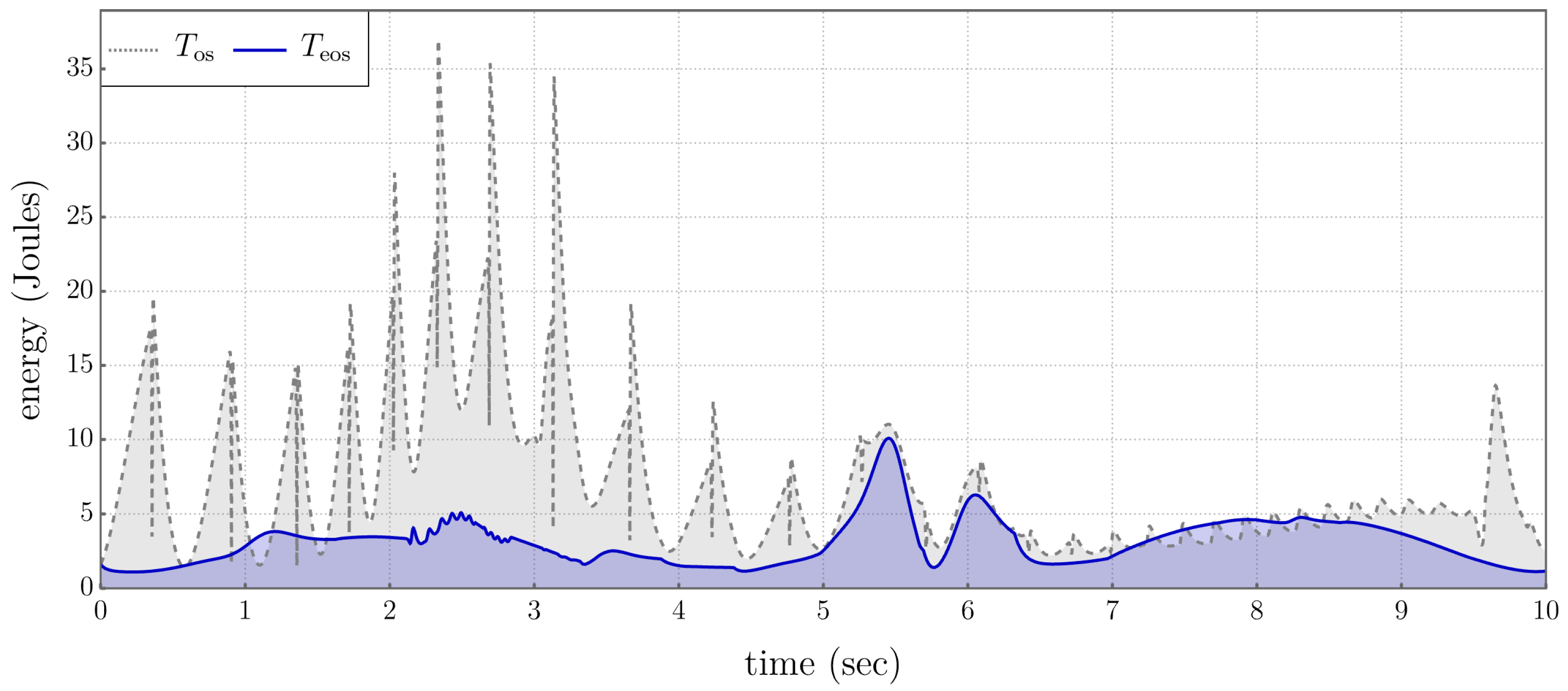

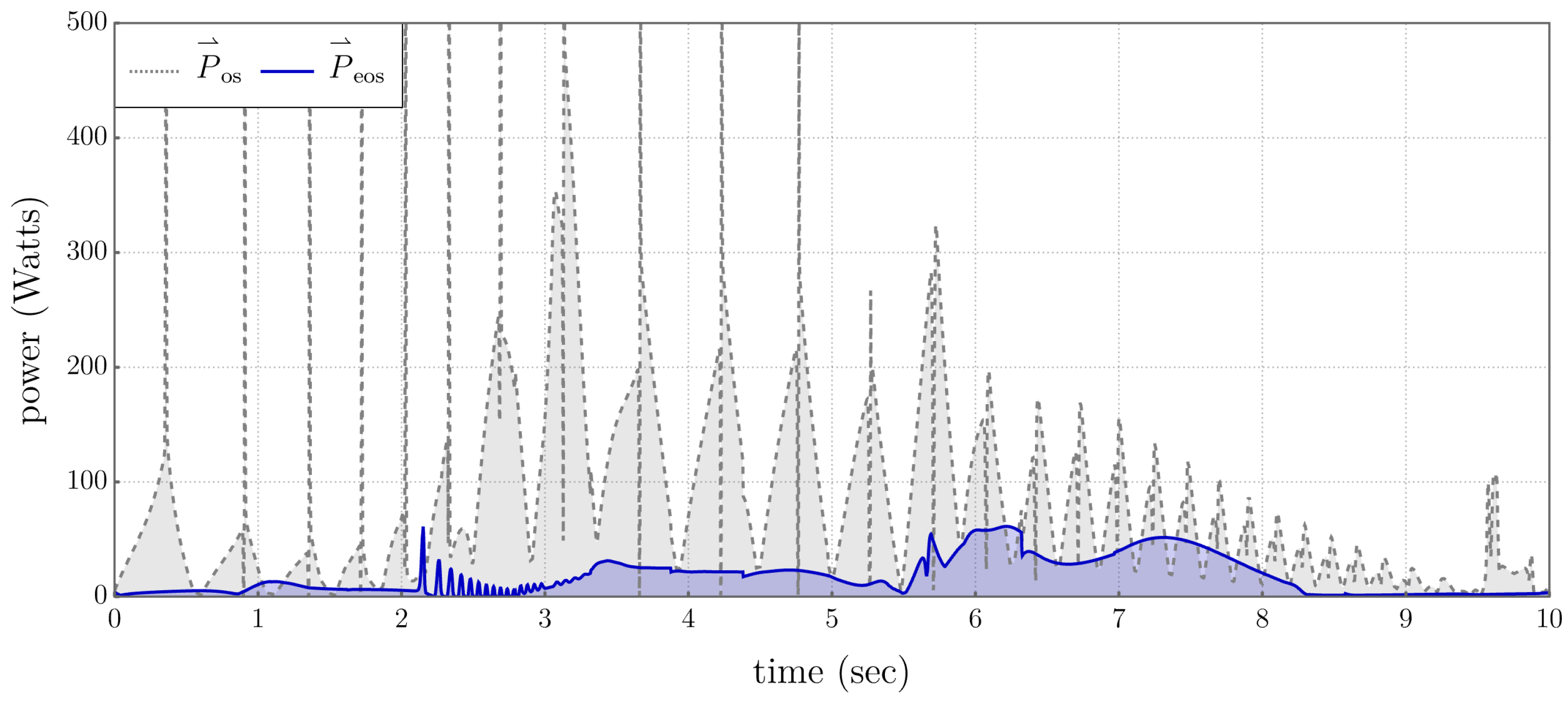

5.3. Comparison of Performance Metrics

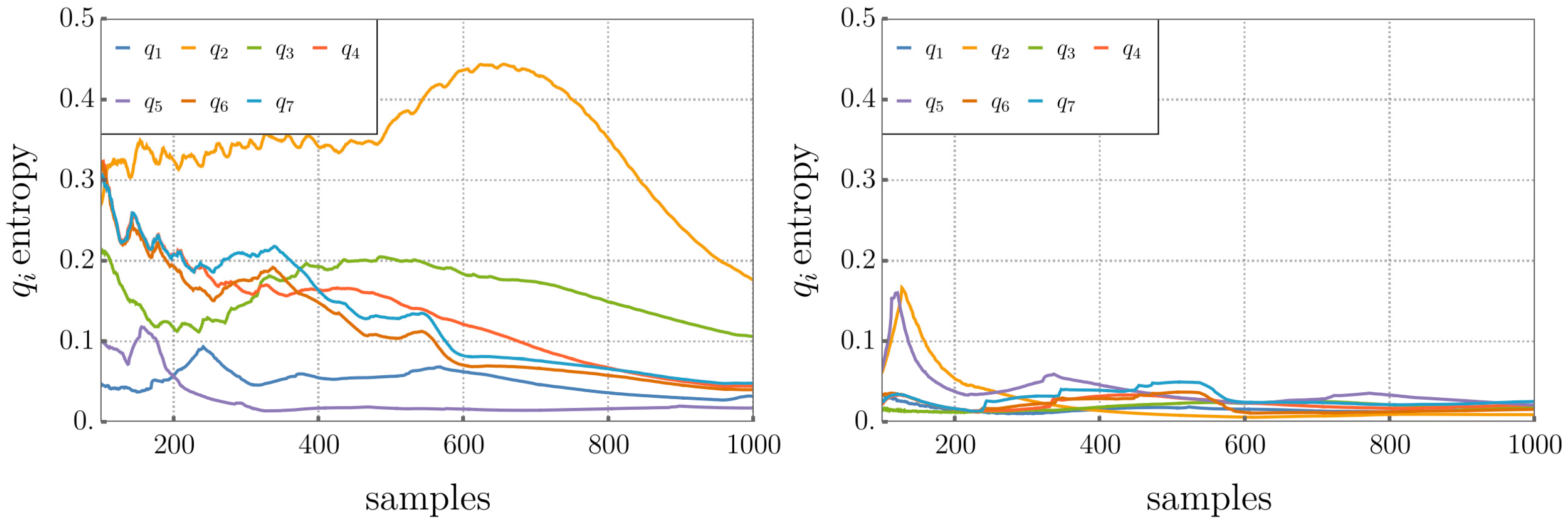

5.4. Self-Motion Coordinate Tracking

6. Summary and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Burdick, J.W. On the Inverse Kinematics of Redundant Manipulators: Characterization of the Self-Motion Manifolds. In Proceedings of the 1989 International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Scottsdale, AZ, USA, 14–19 May 1989; pp. 264–270. [Google Scholar]

- Chiaverini, S.; Oriolo, G.; Maciejewski, A.A. Redundant Robots. In Springer Handbook of Robotics, 2nd ed.; Siciliano, B., Khatib, O., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Khatib, O. A Unified Approach for Motion and Force Control of Robot Manipulators: The Operational Space Formulation. IEEE J. Robot. Autom. 1987, RA-3, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatib, O. The Operational Space Framework. JSME Int. J. 1993, 36, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zergeroglu, E.; Dawson, D.D.; Walker, I.W.; Setlur, P. Nonlinear Tracking Control of Kinematically Redundant Robot Manipulators. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2004, 9, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Zhao, J.; Huang, B. Motion planning algorithms of redundant manipulators based on self-motion manifolds. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2010, 1, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haug, E.J. Manipulator Kinematics and Dynamics on Differentiable Manifolds: Part II Dynamics. J. Comp. Nonlinear Dyn. 2022, 17, 021003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haug, E.J. Redundant Non-Serial Compound Manipulator Kinematics and Dynamics. Mech. Mach. Theory 2024, 200, 105717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haug, E.J.; De Sapio, V.; Peidro, A. Extended Operational Space Kinematics, Dynamics, and Control of Redundant Serial Manipulators. Robotics 2024, 13, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitney, D.E. Resolved Motion Rate Control of Manipulators and Human Prostheses. IEEE Trans. Man-Mach. Syst. 1969, 10, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strang, G. Liner Algebra and Its Applications, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Gosselin, C.; Schreiber, L.-T. Kinematically Redundant Spatial Parallel Mechanisms for Singularity Avoidance and Large Orientational Workspace. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2016, 32, 286–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosselin, C.; Schreiber, L.-T. Redundancy in Parallel Mechanisms: A Review. Appl. Mech. Rev. 2018, 70, 010802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drucker, S.; Seifried, R. Trajectory-tracking control from a multibody system dynamics perspective. Multibody Sys. Dyn. 2023, 38, 341–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, H. Classical Mechanics, 2nd ed.; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, A. Operational Space Inertia for Closed-Chain Robotic Systems. J. Comput. Nonlinear Dyn. 2014, 9, 021015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghian, H.; Keshmiri, M.; Villani, L.; Siciliano, B. Priority Oriented Adaptive Control of Kinematically Redundant Manipulators. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Saint Paul, MN, USA, 14–18 May 2012; pp. 293–298. [Google Scholar]

- De Sapio, V.; Khatib, O.; Delp, S. Task-level approaches for the control of constrained multibody systems. Multibody Sys. Dyn. 2006, 16, 73–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teschl, G. Ordinary Differential Equations and Dynamical Systems; American Math Society: Providence, RI, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Haug, E.J. Computer-Aided Kinematics and Dynamics of Mechanical Systems: Modern Methods; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2026. [Google Scholar]

- Conconi, M.; Carricato, M. A new assessment of singularities of parallel kinematic chains. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2009, 25, 757–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sapio, V.; Park, J. Multitask constrained motion control using a mass- weighted orthogonal decomposition. J. Appl. Mech. 2010, 7, 041004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luces, M.; Mills, J.K.; Benhabib, B. A Review of Redundant Parallel Kinematic Manipulators. J. Intel. Robot. Sys. 2017, 86, 175–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.M. Introduction to Smooth Manifolds, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson, B. Introduction to Topology; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Robbin, J.W.; Salamon, D.A. Introduction to Differential Geometry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Corwin, L.J.; Szczarba, R.H. Multivariable Calculus; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, K.E. An Introduction to Numerical Analysis, 2nd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Haug, E.J. A Cyclic Differentiable Manifold Representation of Redundant Manipulator Kinematics. J. Mech. Robot. 2024, 16, 061005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamir, T.; Yomdin, Y. Repeatability of Redundant Manipulators: Mathematical Solution of the Problem. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 1988, 33, 1004–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, A.; Oriolo, G. Nonholonomic Behavior in Redundant Robots Under Kinematic Control. IEEE Trans. on Robot. Autom 1997, 13, 776–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgarte, J. Stabilization of constraints and integrals of motion in dynamical systems. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 1972, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sapio, V. Advanced Analytical Dynamics: Theory and Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pars, L.A. A Treatise on Analytical Dynamics; Ox Bow Press: Woodbridge, CT, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Bonal, A.; Marshak, A. Approximate Entropy and Sample Entropy: A Comprehensive Tutorial. Entropy 2019, 21, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadamus, A.; Białoszewski, D.; Błażkiewicz, M.; Kowalska, A.J.; Urbaniak, E.; Wydra, K.T.; Wiaderna, K.; Boratyński, R.; Kobza, A.; Marczyński, W. Assessment of the Effectiveness of Rehabilitation after Total Knee Replacement Surgery Using Sample Entropy and Classical Measures of Body Balance. Entropy 2021, 23, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Haug, E.J.; De Sapio, V. Extended Operational Space Kinematics, Dynamics, and Control of Redundant Non-Serial Compound Robotic Manipulators. Robotics 2026, 15, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics15020034

Haug EJ, De Sapio V. Extended Operational Space Kinematics, Dynamics, and Control of Redundant Non-Serial Compound Robotic Manipulators. Robotics. 2026; 15(2):34. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics15020034

Chicago/Turabian StyleHaug, Edward J., and Vincent De Sapio. 2026. "Extended Operational Space Kinematics, Dynamics, and Control of Redundant Non-Serial Compound Robotic Manipulators" Robotics 15, no. 2: 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics15020034

APA StyleHaug, E. J., & De Sapio, V. (2026). Extended Operational Space Kinematics, Dynamics, and Control of Redundant Non-Serial Compound Robotic Manipulators. Robotics, 15(2), 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics15020034