Development and Experimental Evaluation of the Athena Parallel Robot for Minimally Invasive Pancreatic Surgery †

Abstract

1. Introduction

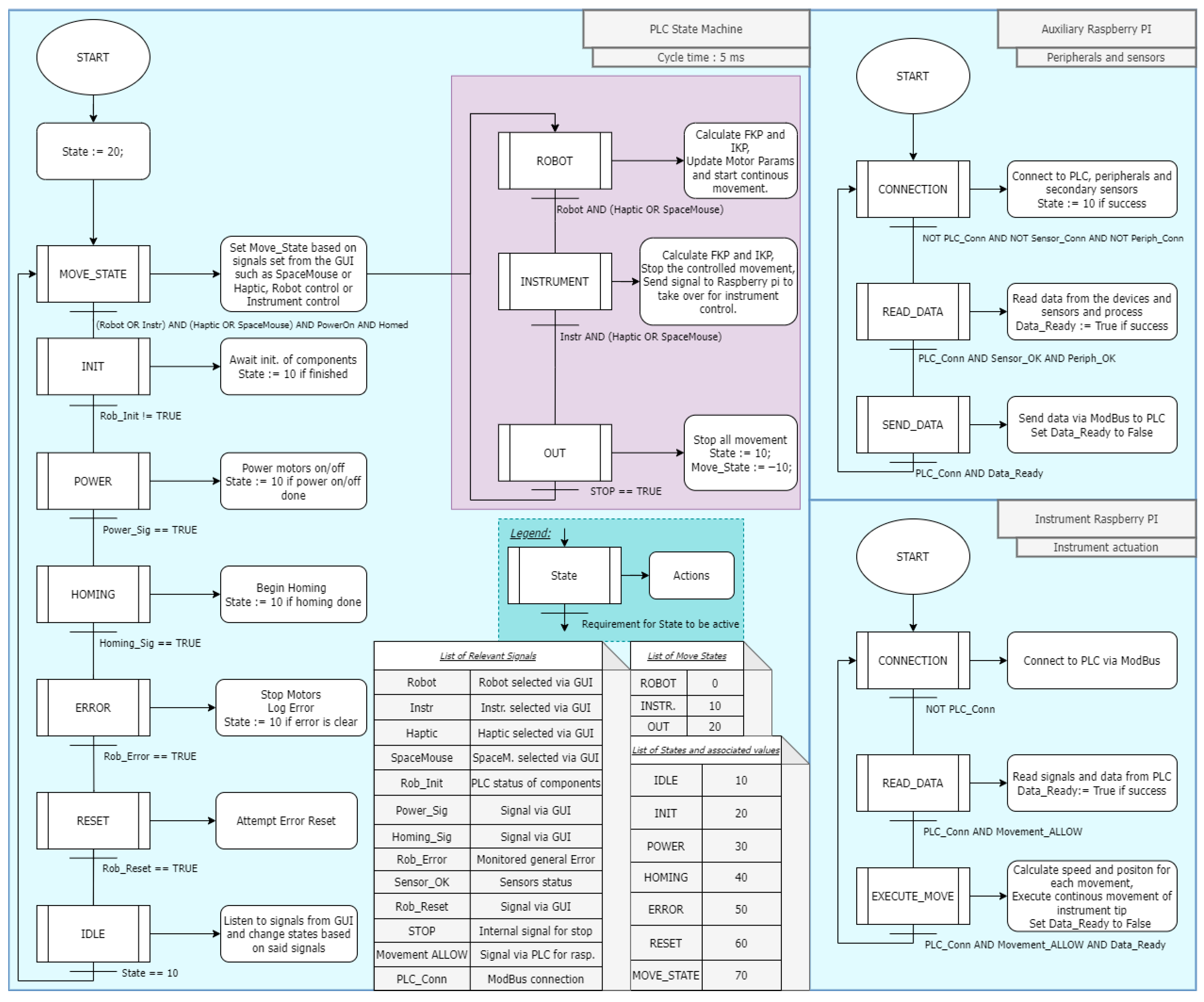

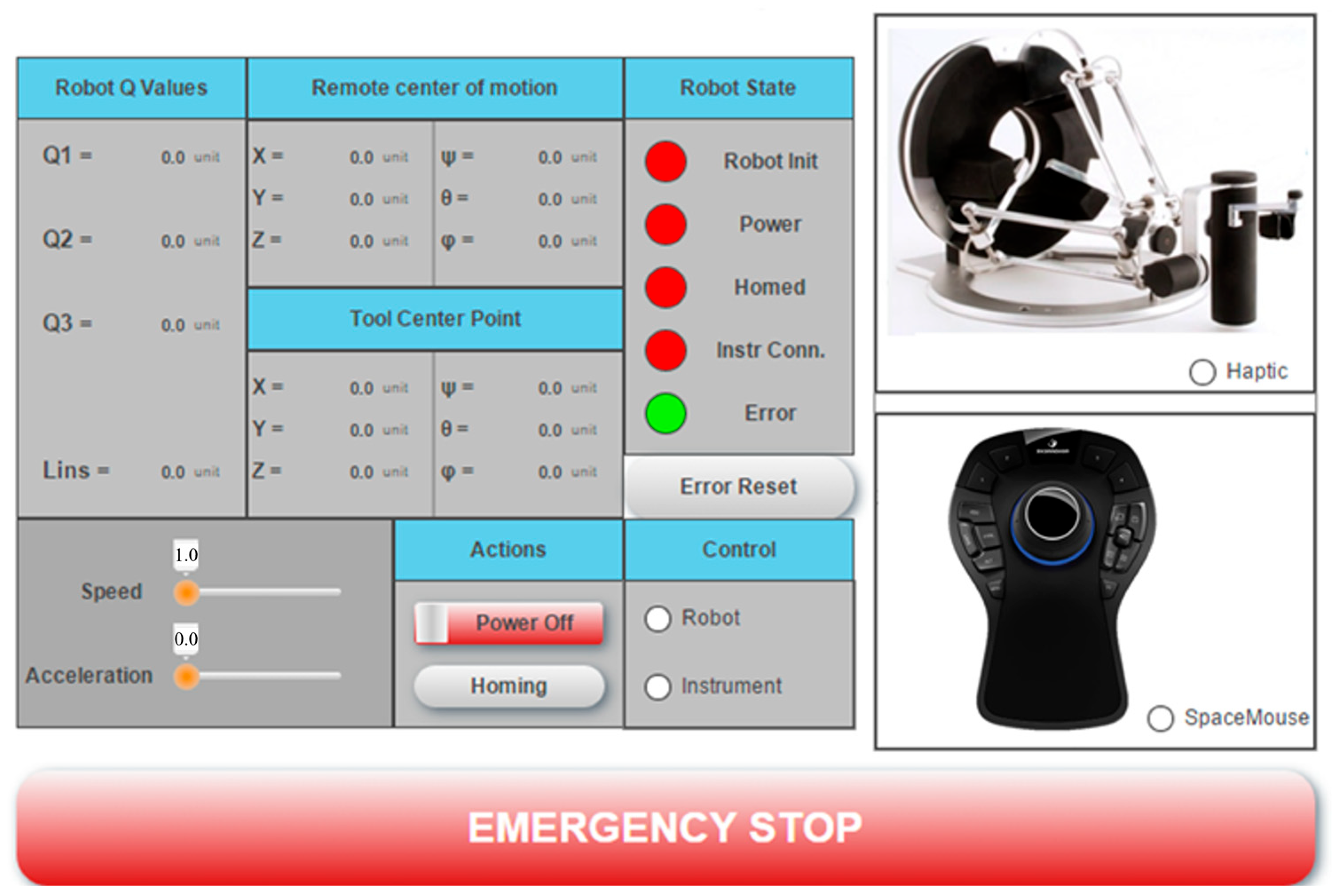

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Model of the Athena Parallel Robot

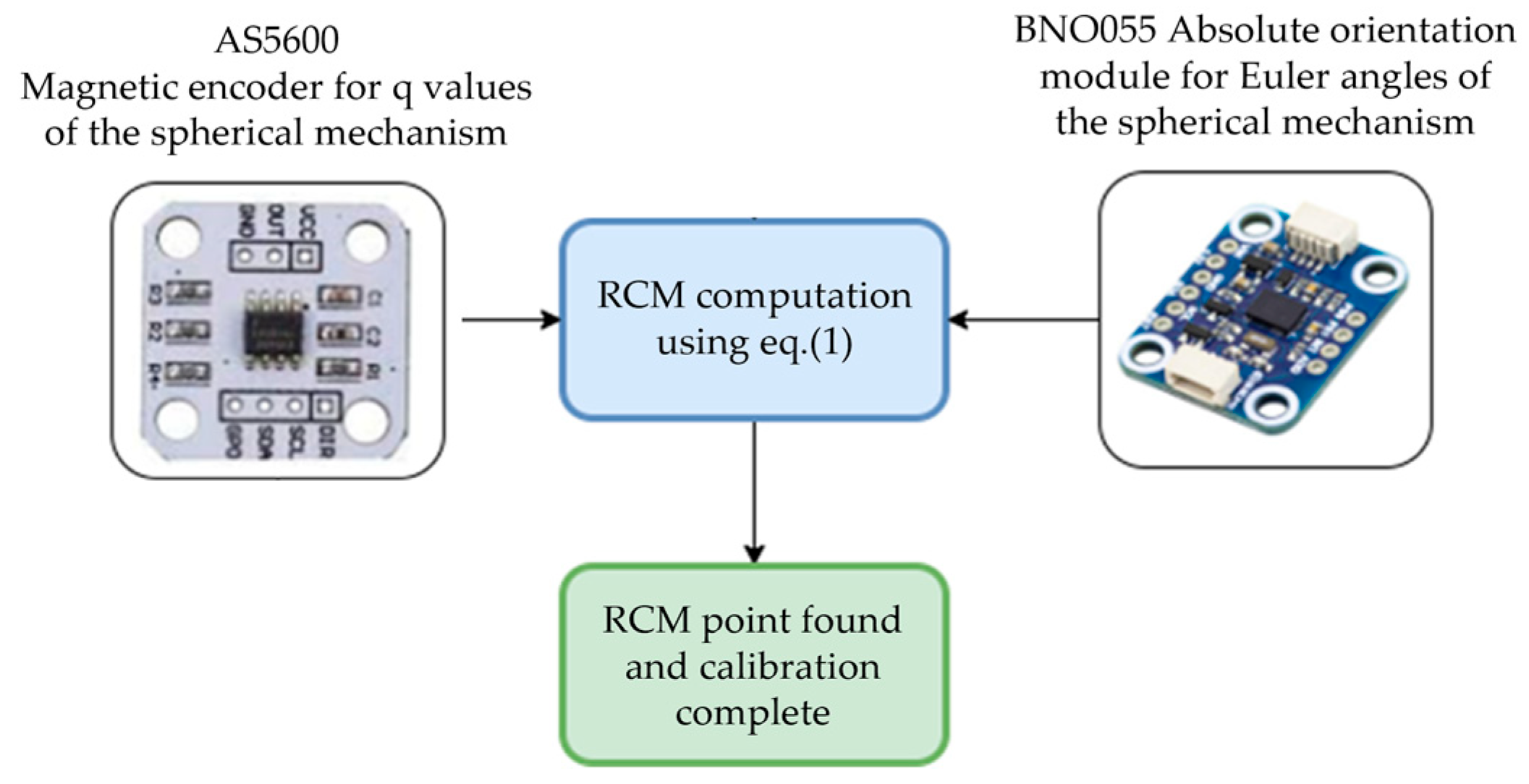

2.2. Calibration Procedure Performed on the Experimental Model

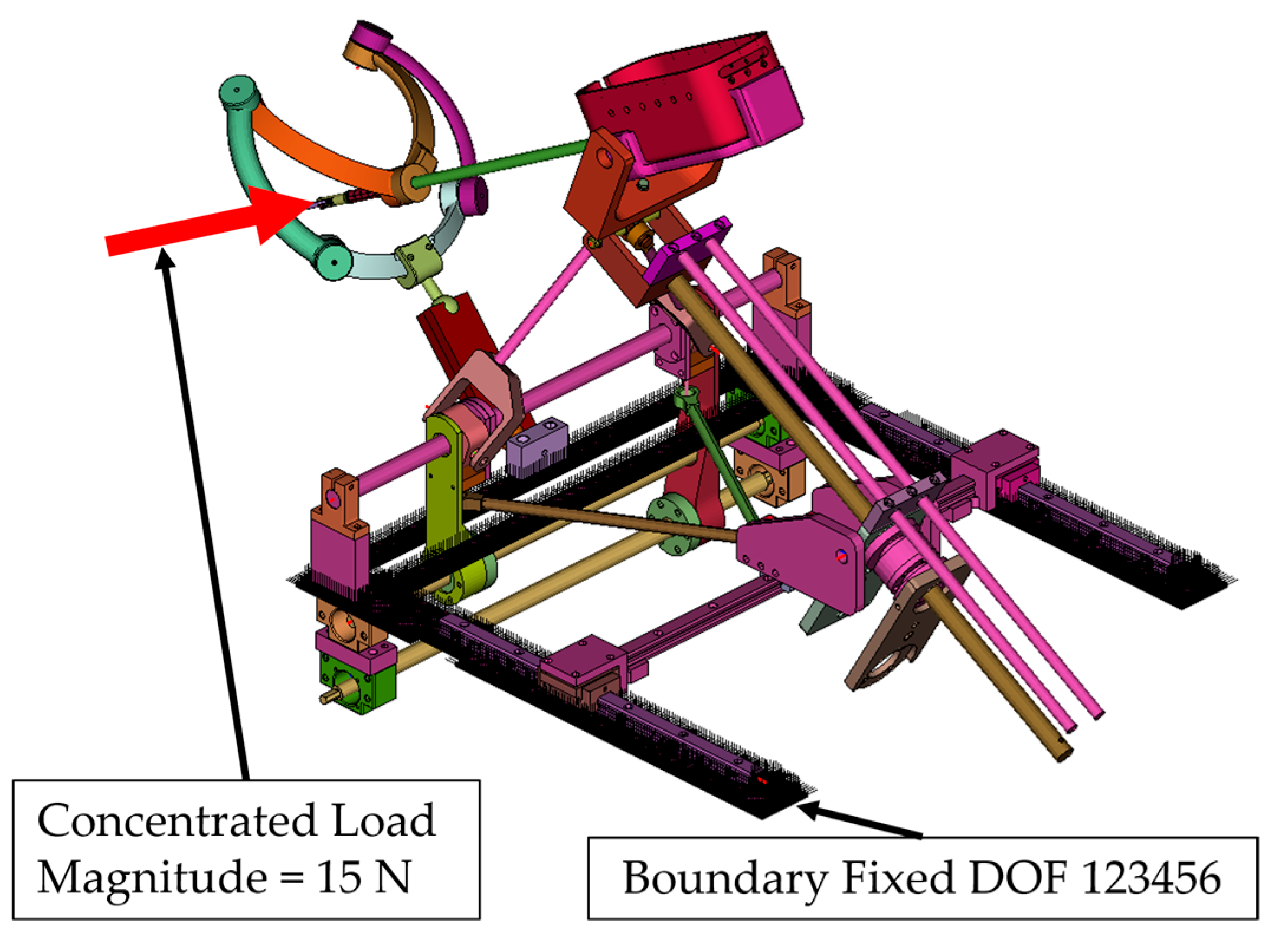

2.3. Stiffness Analysis of the Athena Parallel Robot

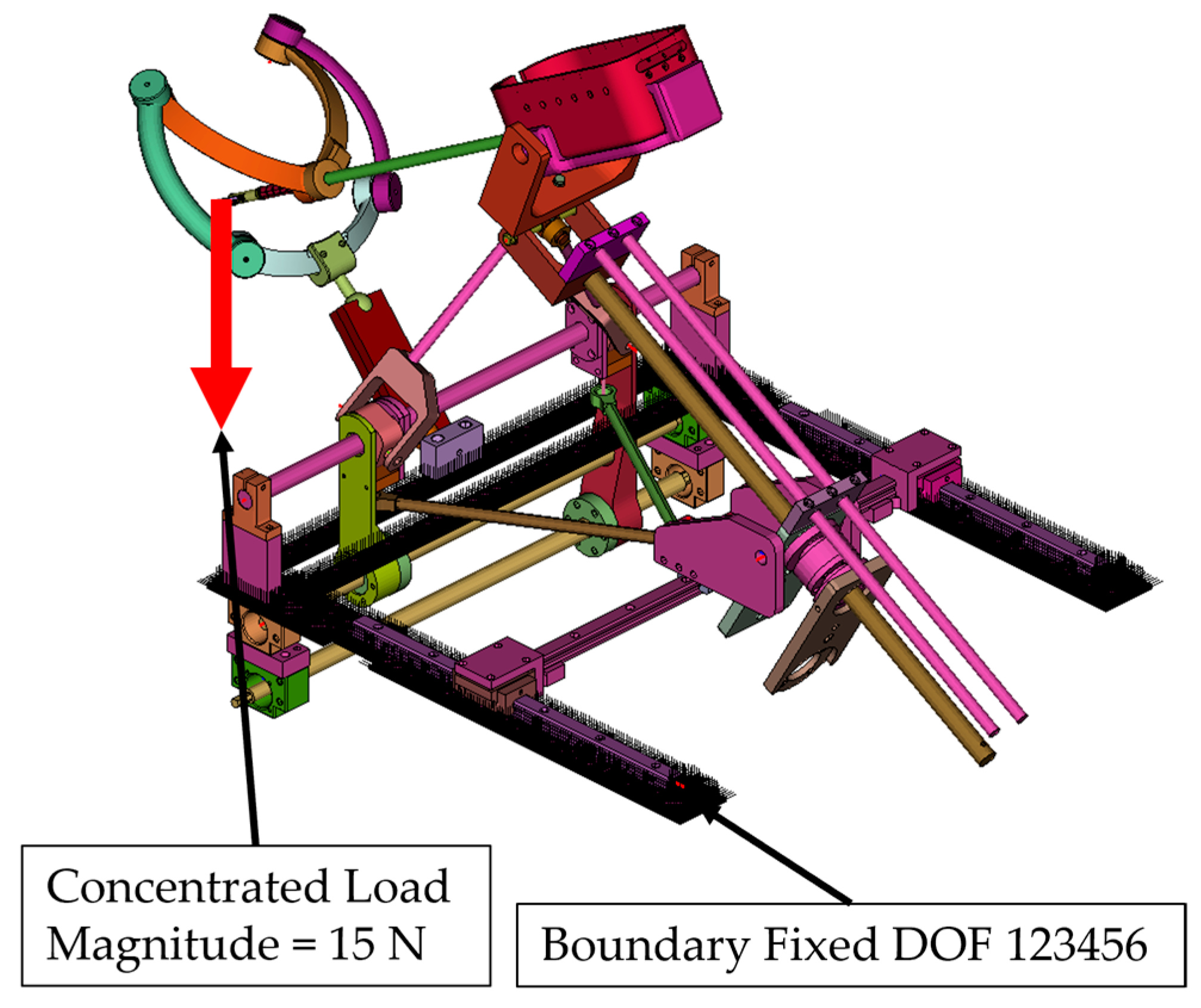

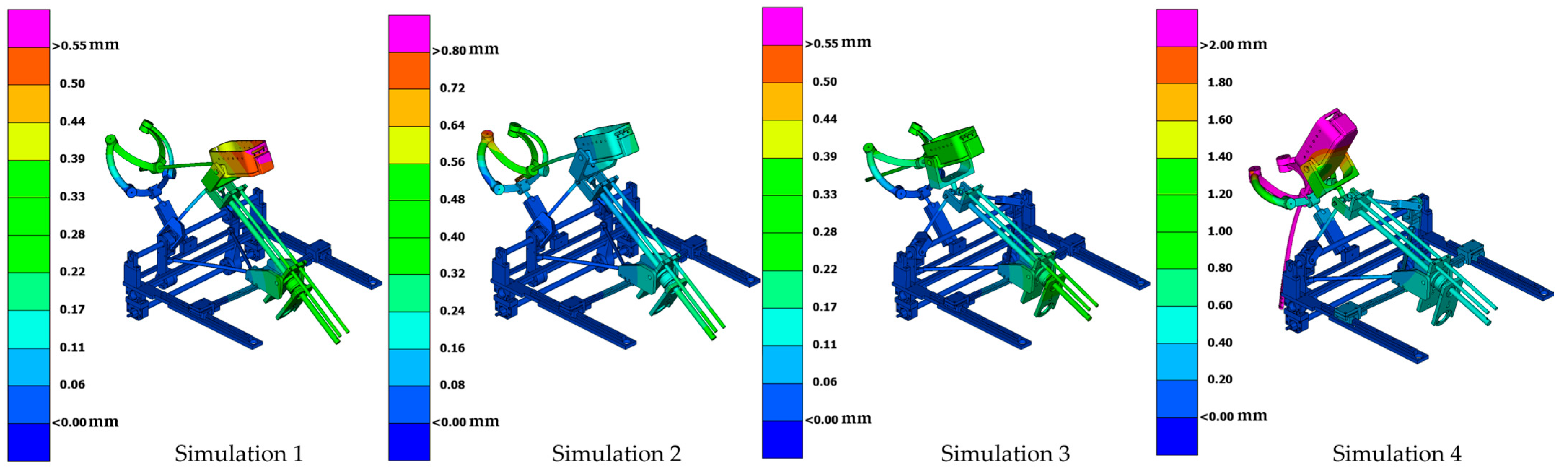

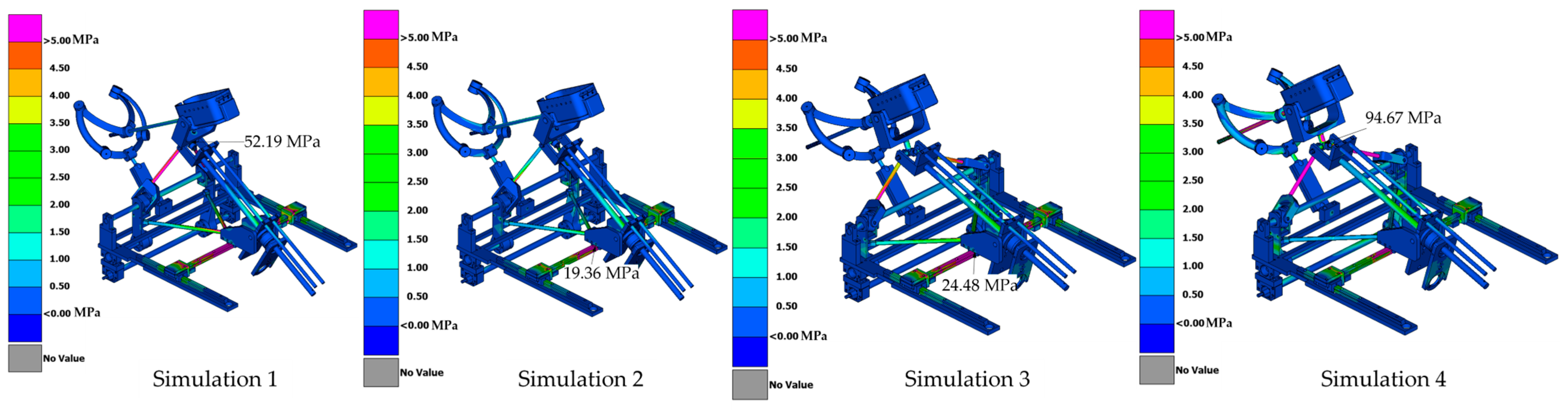

- Simulation 1: Robot in the home position, with a load of 15 N applied along the instrument axis (Figure 8).

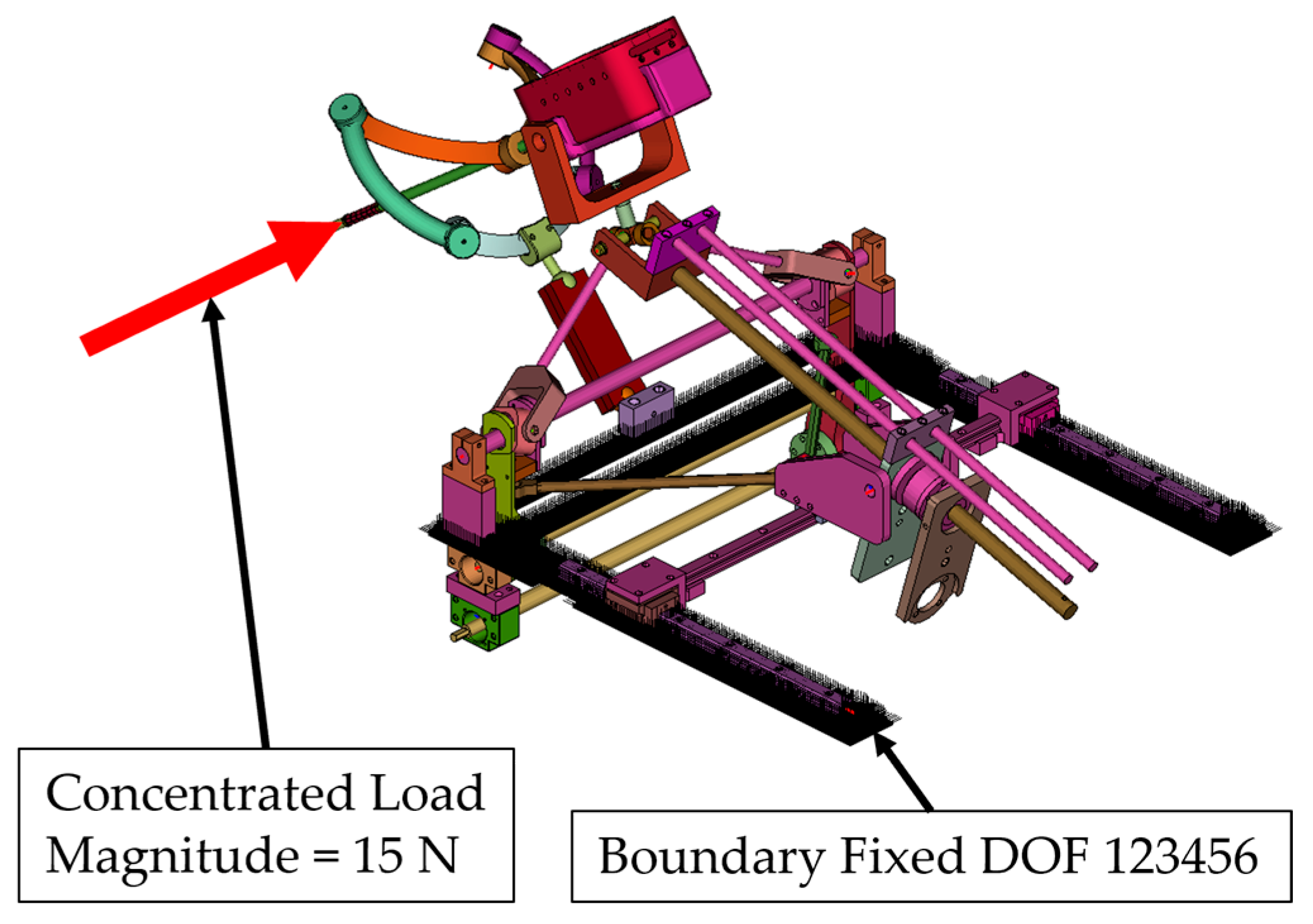

- Simulation 2: Robot in the home position, with a load of 15 N applied along the global Z axis (gravity direction) (Figure 9).

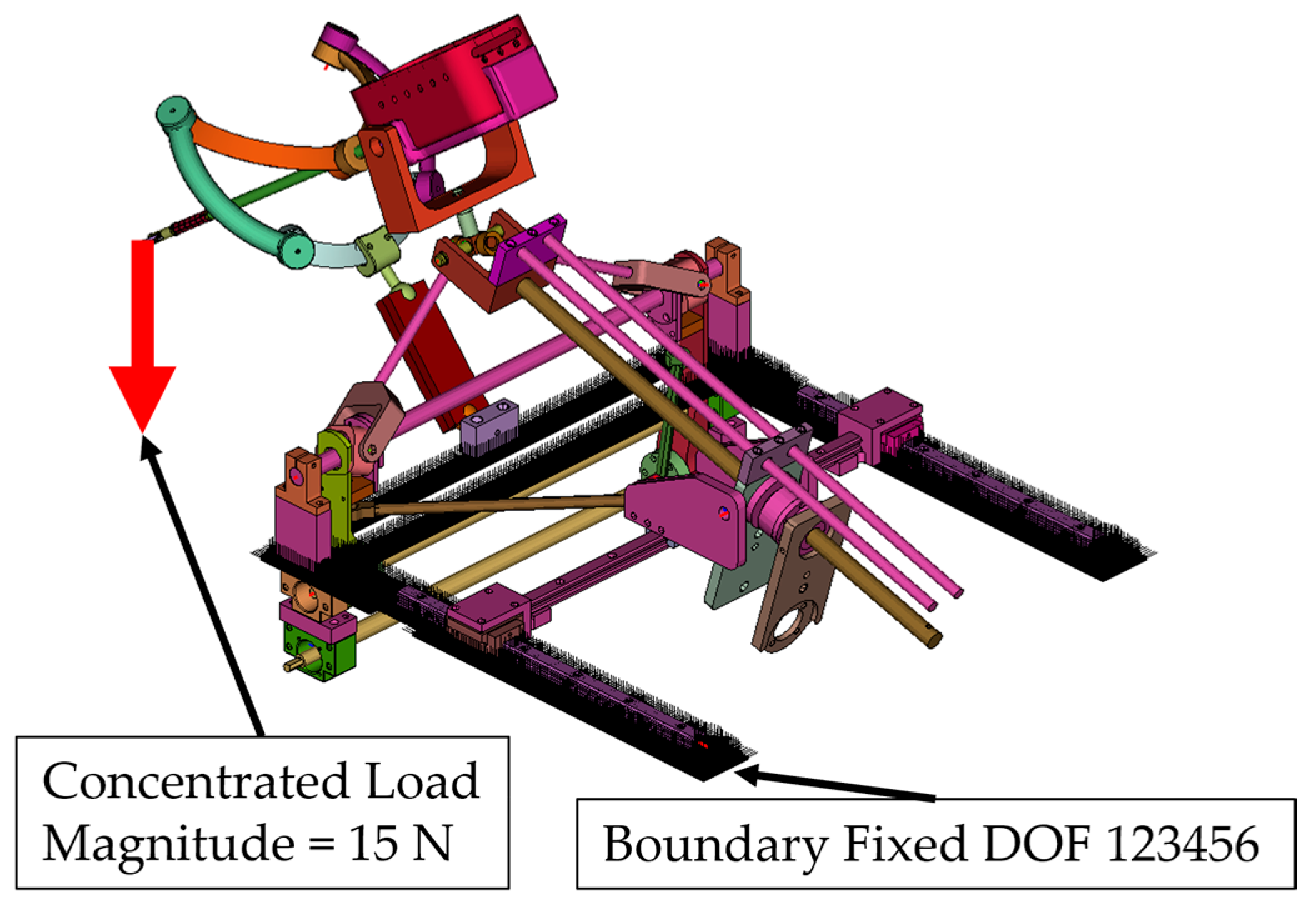

- Simulation 3: Robot in the maximum inserted position, with a load of 15 N applied along the instrument axis (Figure 10).

- Simulation 4: Robot in the maximum inserted position, with a load of 15 N applied along the global Z axis (gravity direction) (Figure 11).

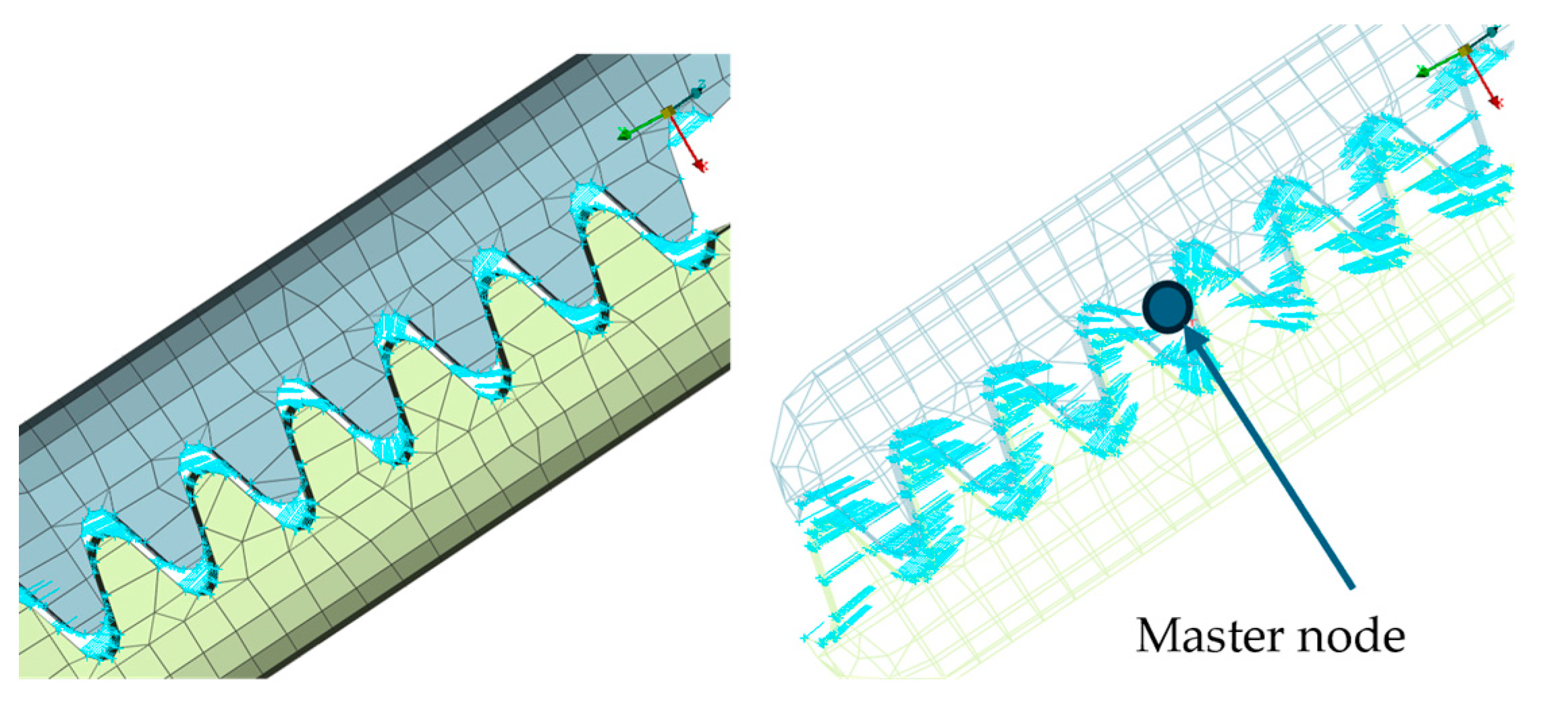

- All relevant structural components of the robot were meshed using 3D continuum elements.

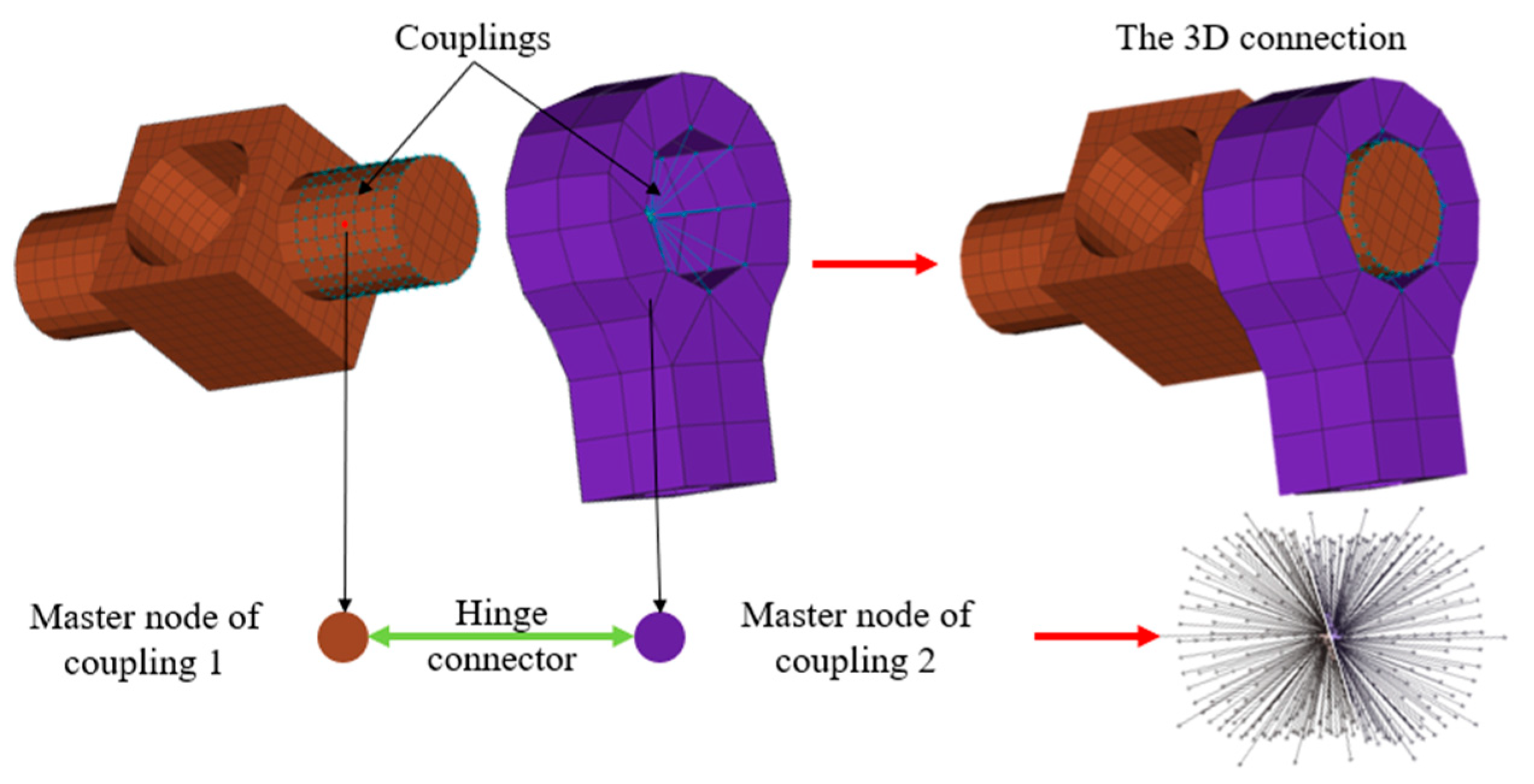

- Passive joints were modeled using joints and connector elements (hinge, translational, and cylindrical) (Figure 12).

- Realistic frictional behavior was defined for all connector elements.

- The mass of auxiliary components not explicitly modeled (e.g., motors) was introduced via mass elements.

- Active joints were locked using kinematic joints to obtain a statically determined configuration.

- A gravitational acceleration of 9.8 m/s2 was applied to the entire model.

- A concentrated force of 15 N was applied to the master node of the coupling at the instrument tip (Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11):

- –

- Along the local instrument Z axis in Simulation 1 and Simulation 3.

- –

- Along the global Z axis in Simulation 2 and Simulation 4.

- To prevent buckling and preserve realistic load transmission, steel material properties were assigned to the instrument shaft.

- A static nonlinear analysis step was used.

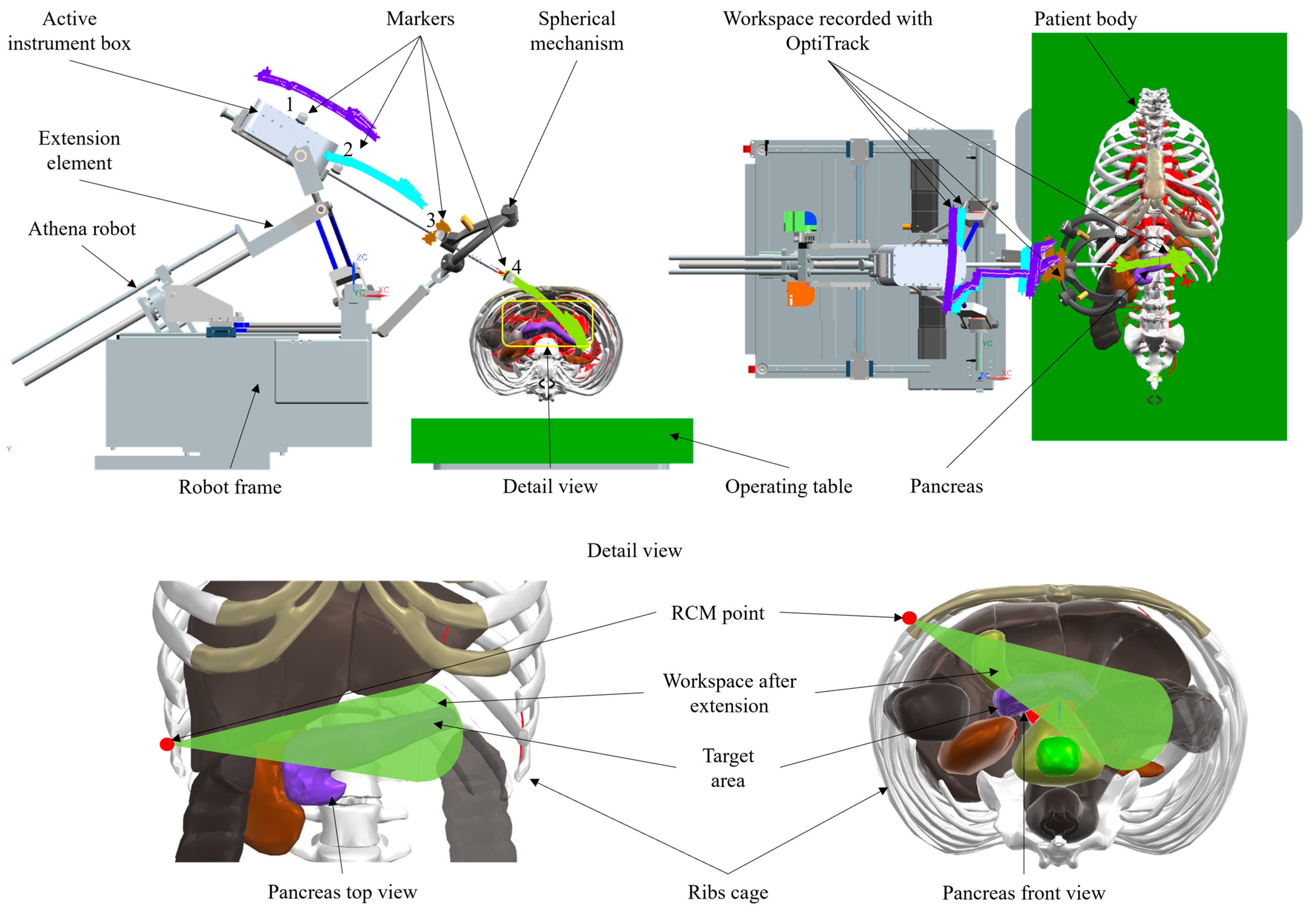

2.4. Robot Workspace Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Stiffness Analysis Results for the Athena Parallel Robot

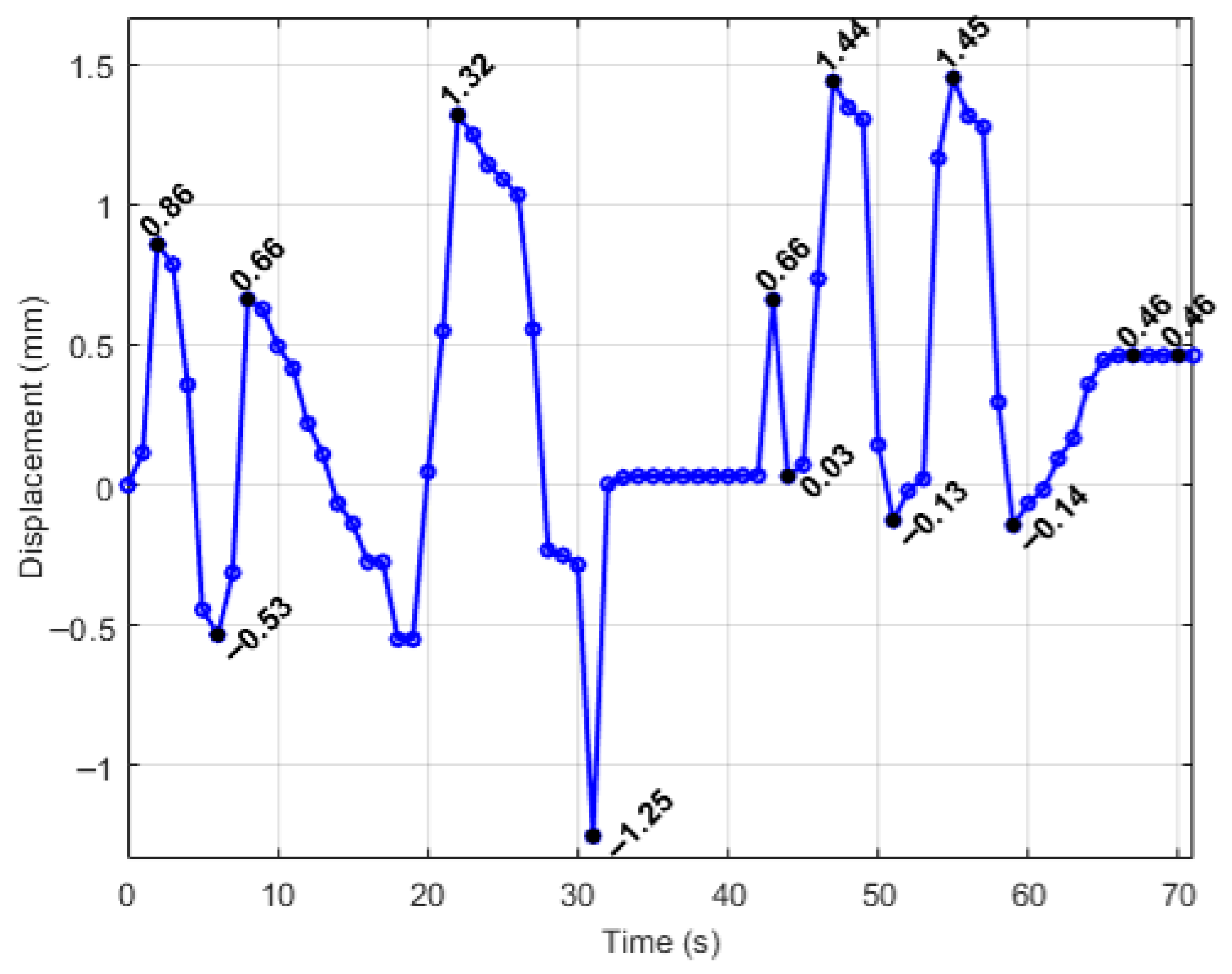

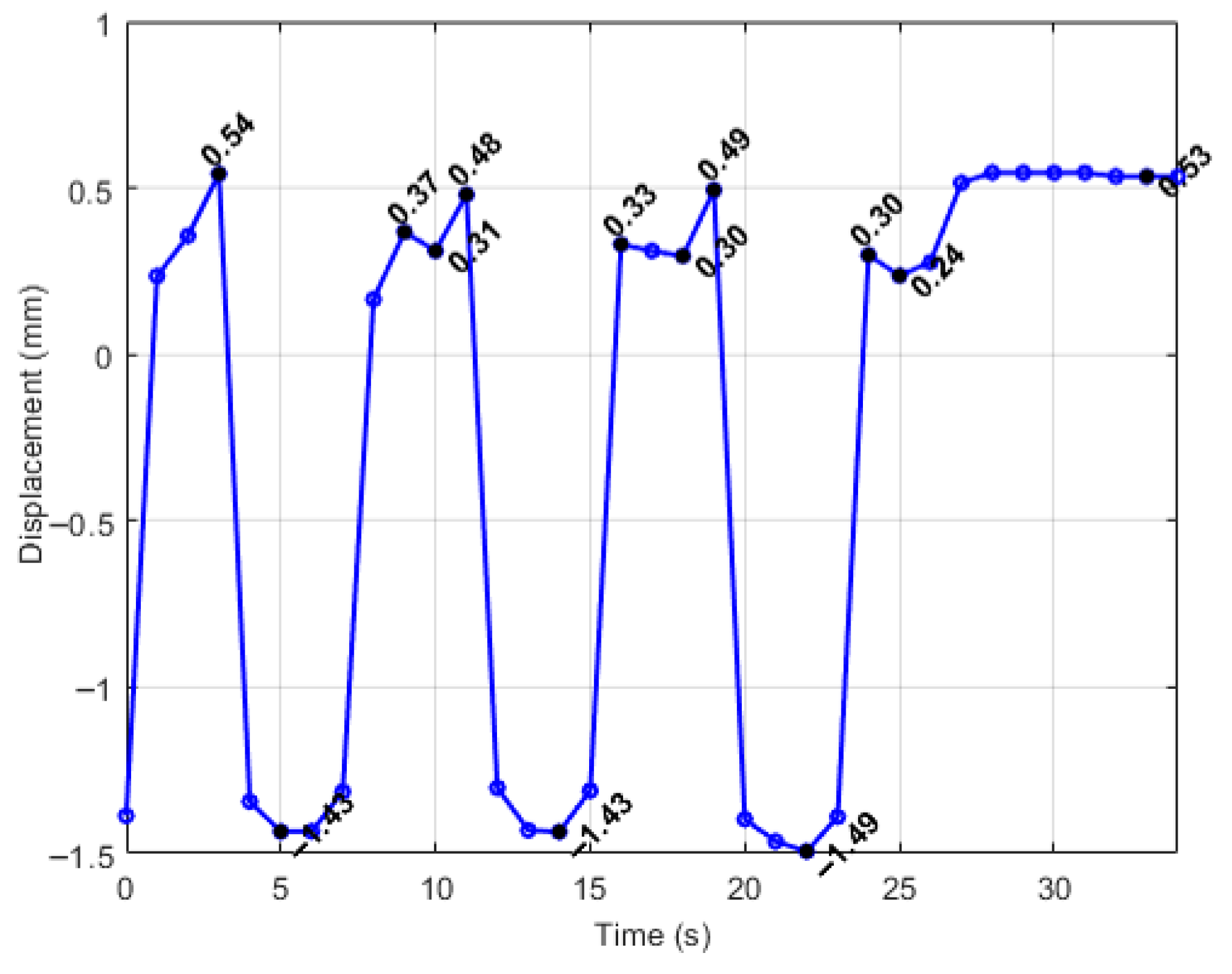

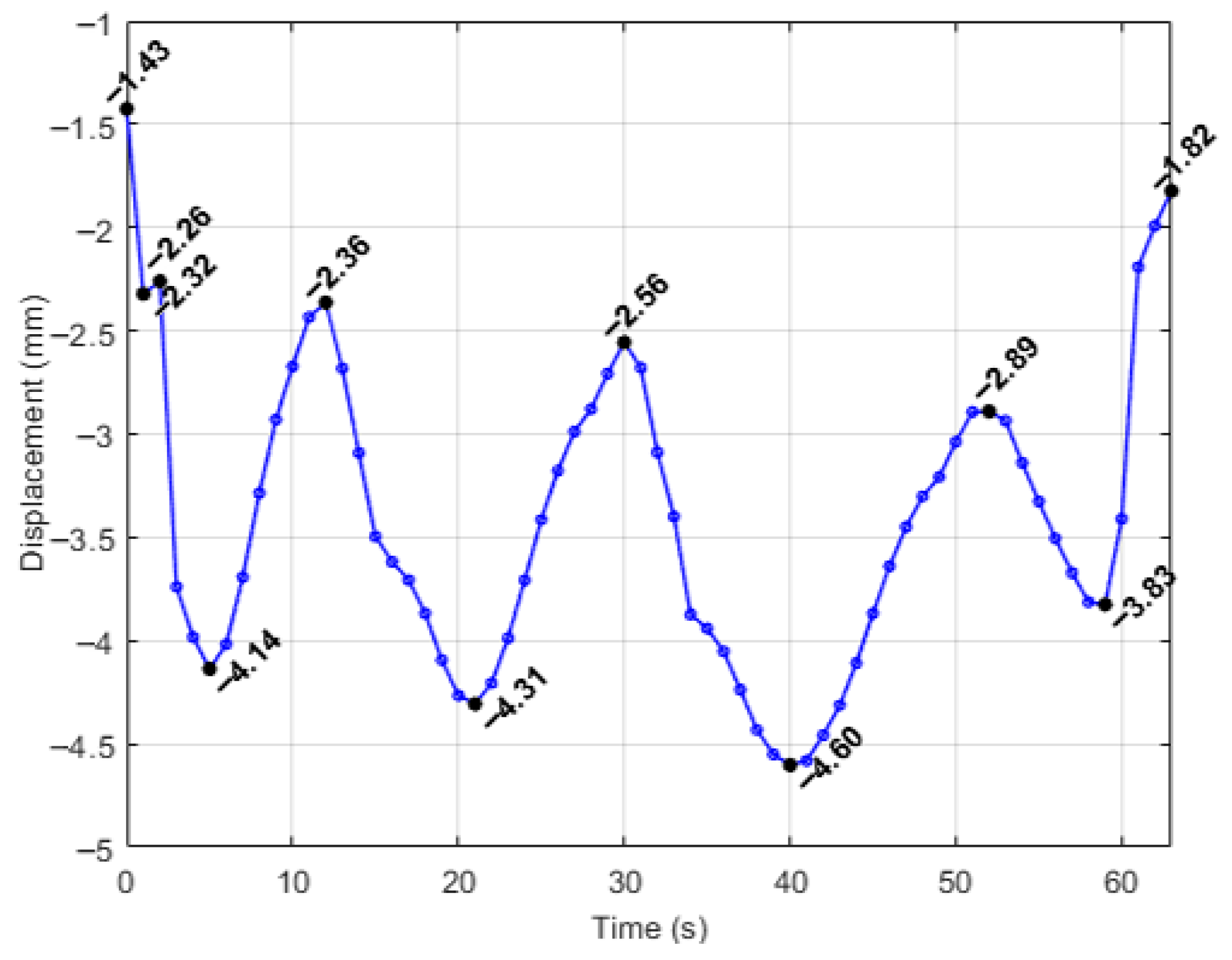

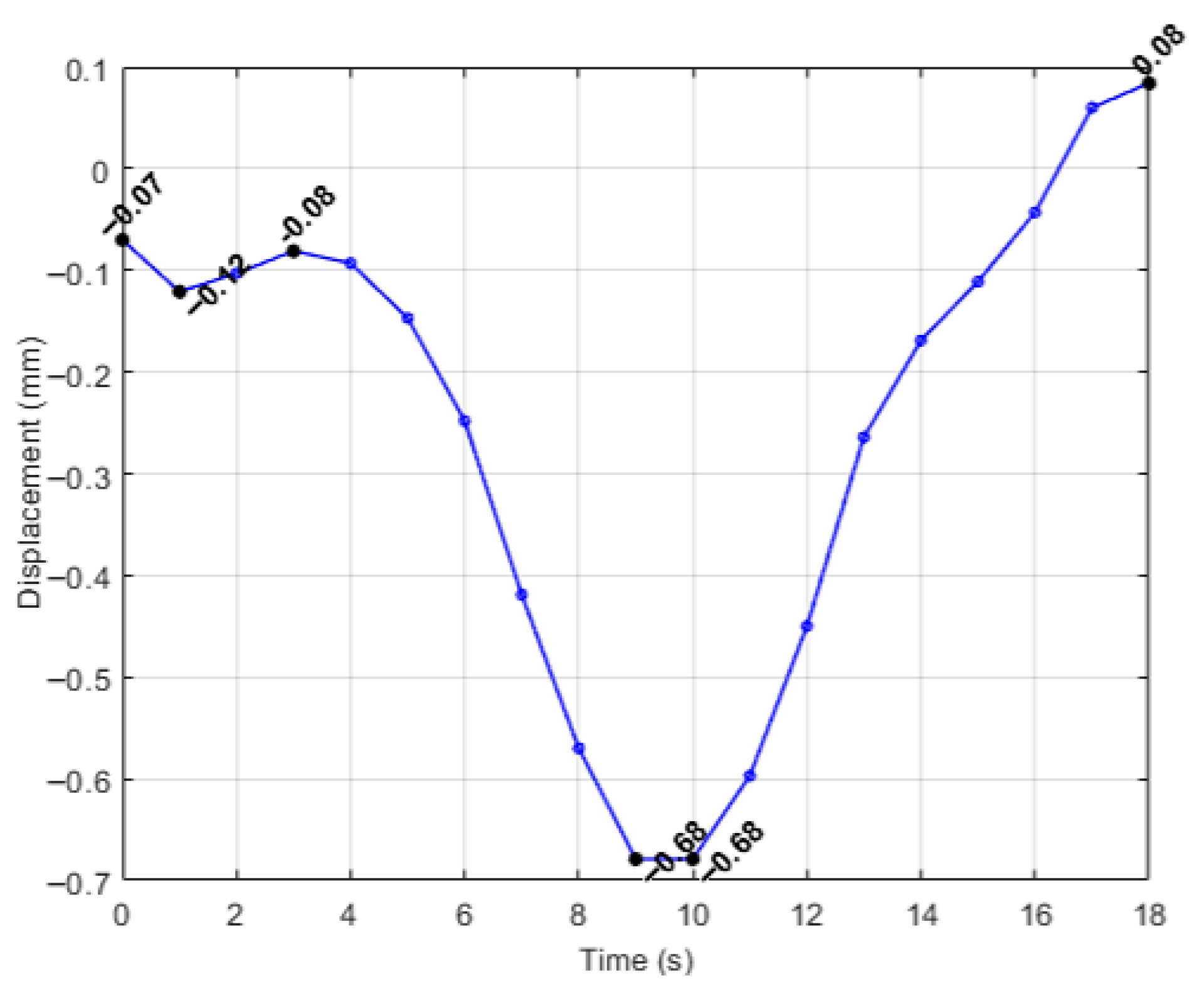

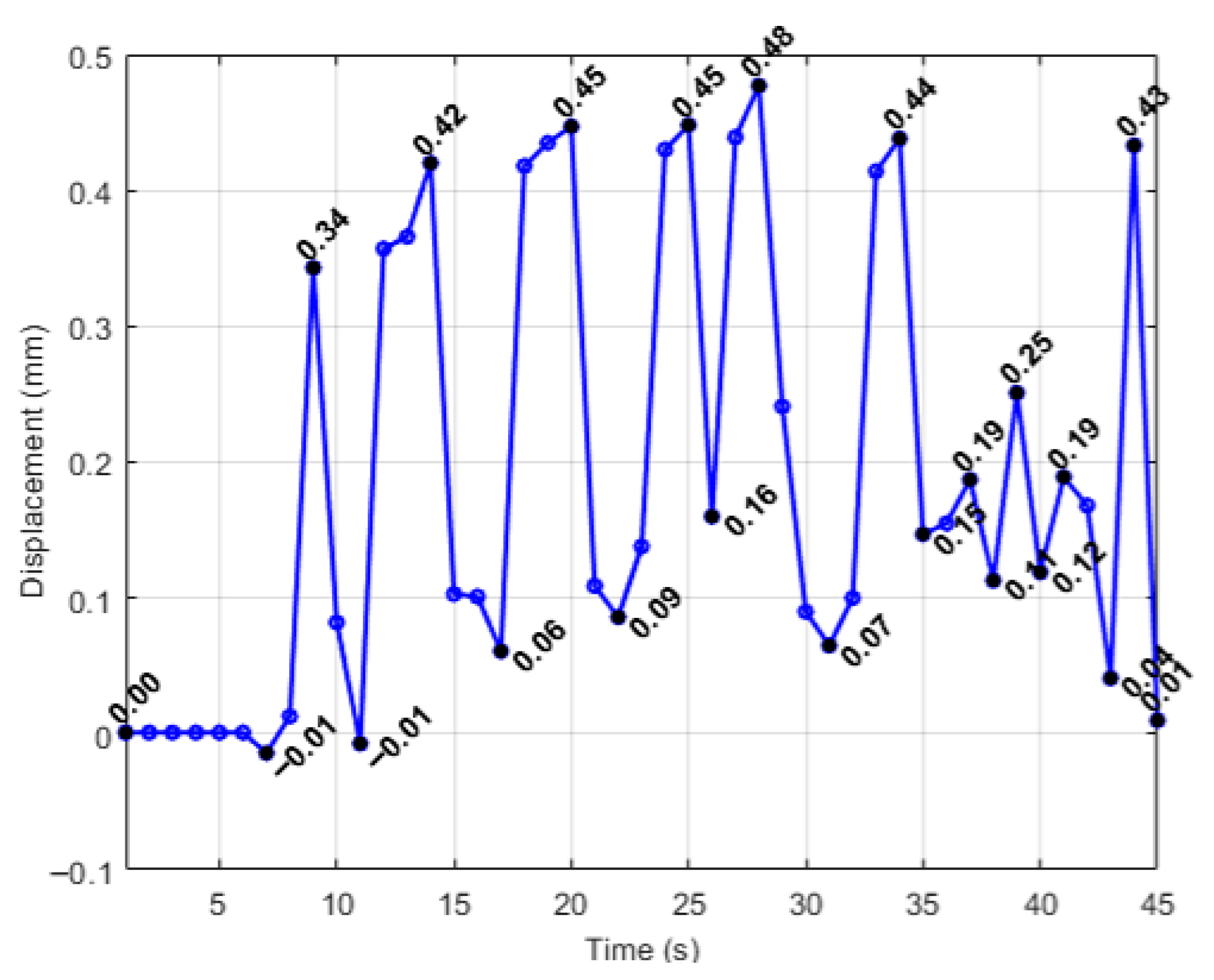

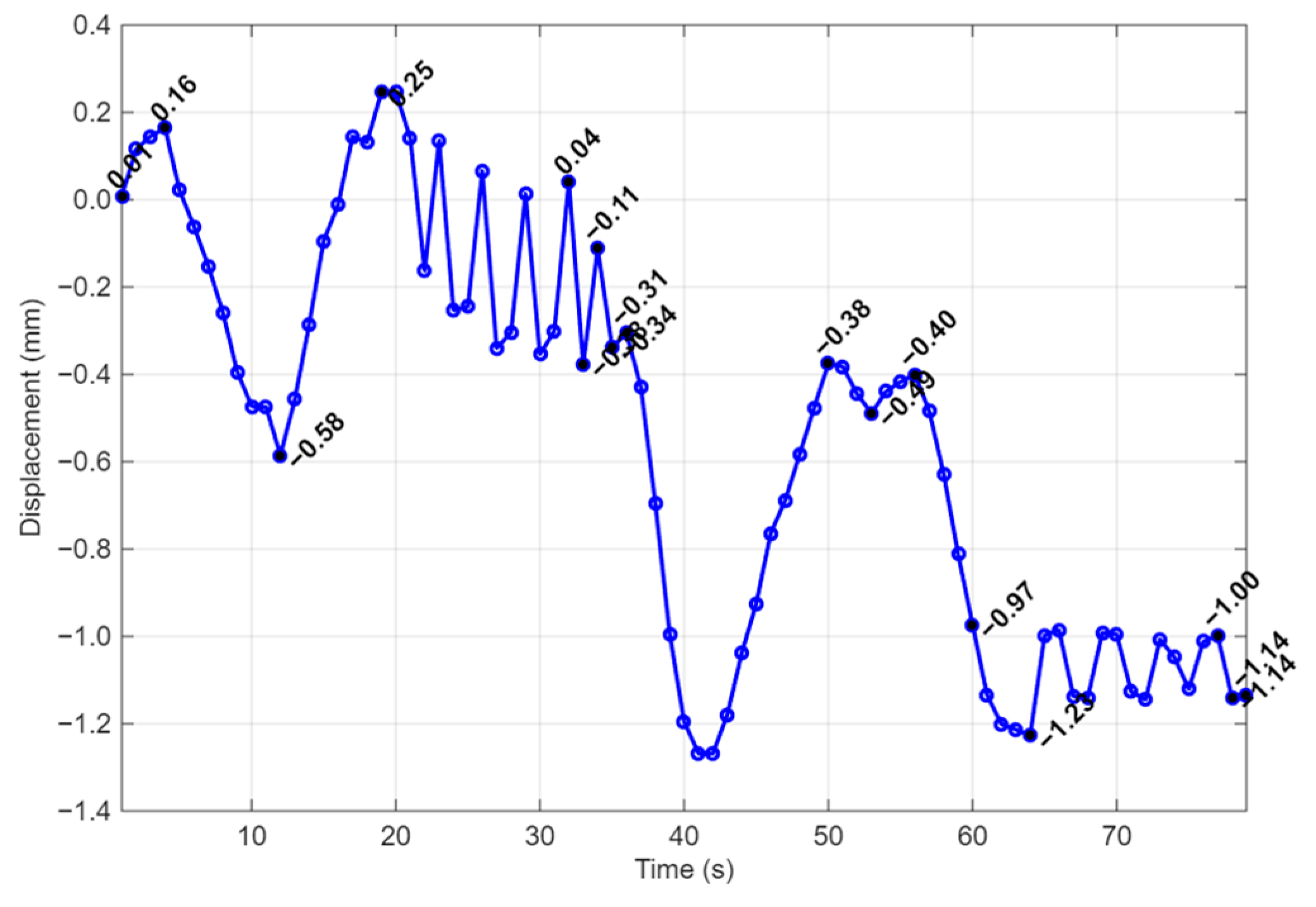

3.2. Workspace Mapping Results for the Athena Parallel Robot

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

- Vaida, C., Gherman, B., Tucan, P., Birlescu, I., Chablat, D., Pisla, D.: Parallel Robotic System for MIS of the Pancreas, Patent Pending A00522/11.09.2024.

- Pisla, D., Chablat, D., Birlescu, I., Vaida, C., Pusca, A., Tucan, P., Ghermna, B. AUTOMATIC INSTRUMENT FOR ROBOT-ASSISTED MINIMALLY INVASIVE SURGERY. Romania, Patent number: RO138293A0. 2024, pp.15.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3D | Three-Dimensional |

| WP | Whipple Procedure |

| PPWP | Pylorus-Preserving Whipple Procedure |

| DP | Distal Pancreatectomy |

| TP | Total Pancreatectomy |

| OS | Overall Survival |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| RDP | Robot-Assisted Distal Pancreatectomy |

| RPD | Robot-Assisted Pancreatoduodenectomies |

| RCM | Remote Center Of Motion |

| CAD | Computer-Aided Design |

| DOF | Degrees of Freedom |

| I2C | Inter-Integrated Circuit |

| USB | Universal Serial Bus |

| B&R | Bernecker & Rainer |

| PLC | Programmable Logic Controller |

| DC | Direct Current |

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Unit |

| INIT | Initialization |

| GUI | Graphical User Interface |

References

- Ansari, D.; Tingstedt, B.; Andersson, B.; Holmquist, F.; Sturesson, C.; Williamsson, C.; Sasor, A.; Borg, D.; Bauden, M.; Andersson, R. Pancreatic Cancer: Yesterday, Today & Tomorrow. Future Oncol. 2016, 12, 1929–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizrahi, J.D.; Surana, R.; Valle, J.W.; Shroff, R.T. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet 2020, 395, 2008–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, W.; Chawla, A.; O’Reilly, E.M. Pancreatic cancer: A review. JAMA 2021, 326, 851–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connor, A.A.; Gallinger, S. Pancreatic cancer evolution and heterogeneity: Integrating omics and clinical data. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2022, 22, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logarajah, S.I.; Jackson, T.; Darwish, M.; Nagatomo, K.; Cho, E.; Osman, H.; Jeyarajah, D.R. Whipple pancreatoduo-denectomy: A technical illustration. Surg. Open Sci. 2022, 7, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symeonidis, D.; Zacharoulis, D.; Kissa, L.; Samara, A.A.; Petsa, E.; Tepetes, K. From classic whipple to pylorus preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy and ultimately to pylorus resecting-stomach preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy: A review. Chirurgia 2023, 118, 335–347. [Google Scholar]

- Cawich, S.O.; Cabral, R.; Douglas, J.; Thomas, D.A.; Mohammed, F.Z.; Naraynsingh, V.; Pearce, N.W. Whipple’s procedure for pancreatic cancer: Training and the hospital environment are more important than volume alone. Surg. Pract. Sci. 2023, 14, 100211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pastena, M.; van Bodegraven, E.A.; Mungroop, T.H.; Vissers, F.L.; Jones, L.R.; Marchegiani, G.; Balduzzi, A.; Klompmaker, S.; Paiella, S.; Tavakoli Rad, S.; et al. Distal pancre-atectomy fistula risk score (D-FRS): Development and international validation. Ann. Surg. 2023, 277, e1099–e1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, D.; Garbarino, G.M.; Ishikawa, Y.; Honda, G.; Jang, J.Y.; Kang, C.M.; Maekawa, A.; Murase, Y.; Nagakawa, Y.; Nishino, H.; et al. Surgical approaches for minimally invasive distal pancreatectomy: A systematic review. J. Hepato-Biliary-Pancreat. Sci. 2022, 29, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzano, G.; Zerbi, A.; Aleotti, F.; Capretti, G.; Melzi, R.; Pecorelli, N.; Mercalli, A.; Nano, R.; Magistretti, P.; Gavazzi, F.; et al. Total Pancreatectomy with Islet Autotrans-plantation as an Alternative to High-risk Pancreatojejunostomy After Pancreaticoduodenectomy: A Prospective Ran-domized Trial. Ann. Surg. 2023, 277, 894–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaouch, M.A.; Leon, P.; Cassese, G.; Aguilhon, C.; Khayat, S.; Panaro, F. Total pancreatectomy with intraportal islet autotransplantation for pancreatic malignancies: A literature overview. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2022, 22, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrucciani, N.; Nigri, G.; Giannini, G.; Sborlini, E.; Antolino, L.; de’Angelis, N.; Gavriilidis, P.; Valente, R.; Lainas, P.; Dagher, I.; et al. Total pancreatectomy for pancreatic carcinoma: When, why, and what are the outcomes? Results of a systematic review. Pancreas 2020, 49, 175–180. [Google Scholar]

- Karim, S.A.M.; Abdulla, K.S.; Abdulkarim, Q.H.; Rahim, F.H. The outcomes and complications of pancreaticoduo-denectomy (Whipple procedure): Cross sectional study. Int. J. Surg. 2018, 52, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGuigan, A.; Kelly, P.; Turkington, R.C.; Jones, C.; Coleman, H.G.; McCain, R.S. Pancreatic cancer: A review of clinical diagnosis, epidemiology, treatment and outcomes. World J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 24, 4846–4861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puckett, Y.; Garfield, K. Pancreatic Cancer. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nortunen, M.; Meriläinen, S.; Ylimartimo, A.; Peroja, P.; Karjula, H.; Niemelä, J.; Saarela, A.; Huhta, H. Evolution of pancreatic surgery over time and effects of centralization-a single-center retrospective cohort study. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2023, 14, 366–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nießen, A.; Hackert, T. State-of-the-art surgery for pancreatic cancer. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2022, 407, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrell, A.L.G.; Morrell-Junior, A.C.; Morrell, A.G.; Mendes, J.M.F.; Tustumi, F.; De-Oliveira-E-Silva, L.G.; Morrell, A. The history of robotic surgery and its evolution: When illusion becomes reality. Rev. Colégio Bras. Cir. 2021, 48, e20202798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molle, F.; Savastano, M.C.; Giannuzzi, F.; Fossataro, C.; Brando, D.; Molle, A.; Rebecchi, M.T.; Falsini, B.; Mattei, R.; Mirisola, G.; et al. 3D Da Vinci robotic surgery: Is it a risk to the surgeon’s eye health? J. Robot. Surg. 2023, 17, 1995–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisla, D.; Birlescu, I.; Crisan, N.; Pusca, A.; Andras, I.; Tucan, P.; Radu, C.; Gherman, B.; Vaida, C. Singularity Analysis and Geometric Optimization of a 6-DOF Parallel Robot for SILS. Machines 2022, 10, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melvin, W.S.; Needleman, B.J.; Krause, K.R.; Ellison, E.C. Robotic resection of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor. J. Laparoendosc. Adv. Surg. Tech. A 2003, 13, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giulianotti, P.C.; Coratti, A.; Angelini, M.; Sbrana, F.; Cecconi, S.; Balestracci, T.; Caravaglios, G. Robotics in general surgery: Personal experience in a large community hospital. Arch. Surg. 2003, 138, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damoli, I.; Butturini, G.; Ramera, M.; Paiella, S.; Marchegiani, G.; Bassi, C. Minimally invasive pancreatic surgery—A review. Wideochir. Inne Tech. Maloinwazyjne 2015, 10, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolbeinsson, H.M.; Chandana, S.; Wright, G.P.; Chung, M. Pancreatic Cancer: A Review of Current Treatment and Novel Therapies. J. Investig. Surg. 2022, 36, 2129884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Xu, L.; Liu, S.; Li, J.; Xia, J.; Qin, X.; Li, Y.; Gao, T.; Tang, X. The state-of-the-art and perspectives of laser ablation for tumor treatment. Cyborg Bionic Syst. 2024, 5, 0062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Guo, S.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, Z.; Xu, Y. A robotic teleoperation system enhanced by augmented reality for natural human–robot interaction. Cyborg Bionic Syst. 2024, 5, 0098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucan, P.; Vaida, C.; Horvath, D.; Caprariu, A.; Burz, A.; Gherman, B.; Iakab, S.; Pisla, D. Design and Experimental Setup of a Robotic Medical Instrument for Brachytherapy in Non-Resectable Liver Tumors. Cancers 2022, 14, 5841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, X.; Chu, G.; Feng, W.; Ding, X.; Yin, X.; Zhang, L.; Lv, W.; Ma, L.; Sun, L.; et al. Application of Improved Robot-assisted Laparoscopic Telesurgery with 5G Technology in Urology. Eur. Urol. 2023, 83, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaida, C.; Pisla, D.; Plitea, N.; Gherman, B.; Gyurka, B.; Stancel, E.; Hesselbach, J.; Raatz, A.; Vlad, L.; Graur, F. Development of a control system for a parallel robot used in minimally invasive surgery. In International Conference on Advancements of Medicine and Health Care through Technology; Vlad, S., Ciupa, R.V., Nicu, A.I., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisla, D.; Gherman, B.; Plitea, N.; Gyurka, B.; Vaida, C.; Vlad, L.; Graur, F.; Radu, C.; Suciu, M.; Szilaghi, A.; et al. Parasurg hybrid parallel robot for minimally invasive surgery. Chirurgia 2011, 106, 619–625. [Google Scholar]

- Haidegger, T.; Speidel, S.; Stoyanov, D.; Satava, R.M. Robot-assisted minimally invasive surgery—Surgical robotics in the data age. In Proceedings of the IEEE; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; Volume 110, pp. 835–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisla, D.; Pusca, A.; Caprariu, A.; Pisla, A.; Gherman, B.; Vaida, C.; Chablat, D. Design analysis of an innovative parallel robot for minimally invasive pancreatic surgery. In International Workshop on Medical and Service Robots; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 466–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldridge, B.; Gruben, K.; LaRose, D.; Funda, J.; Gomory, S.; Karidis, J.; McVicker, J.; Taylor, R.; Anderson, J. A remote center of motion robotic arm for computer assisted surgery. Robotica 1996, 14, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisla, D.; Birlescu, I.; Vaida, C.; Tucan, P.; Pisla, A.; Gherman, B.; Crisan, N.; Plitea, N. Algebraic modeling of kinematics and singularities for a prostate biopsy parallel robot. Proc. Rom. Acad. Ser. A 2018, 19, 489–497. [Google Scholar]

- Siemens PLM Software. Available online: https://plm.sw.siemens.com/en-US/nx/cad-online/ (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Pisla, D.; Pusca, A.; Gherman, B.; Pisla, A.; Birlescu, I.; Tucan, P.; Vaida, C.; Chablat, D. Modeling and Simulation of a Novel Parallel Robotic System for Minimally Invasive Pancreatic Surgery. J. Mech. Robot. 2025, 18, 024501. [Google Scholar]

- Saini, S.; Orlando, M.F.; Pathak, P.M. Intelligent control of a master-slave based robotic surgical system. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2022, 105, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rus, G.; Andras, I.; Vaida, C.; Crisan, N.; Gherman, B.; Radu, C.; Tucan, P.; Iakab, S.; Hajjar, N.A.; Pisla, D. Artificial Intelligence-Based Hazard Detection in Robotic-Assisted Single-Incision Oncologic Surgery. Cancers 2023, 15, 3387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, R.; Walsh, K.; O’Cearbhaill, E.; McMahon, C.J. Three-Dimensional Printed Cardiac Models Demonstrating Extensive Cardiac Calcification Assist in Preprocedural Planning. World J. Pediatr. Congenit. Heart Surg. 2025, 16, 543–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusca, A.; Covaciu, F.; Burz, A.; Horsia, A.; Mougenot, P.; Pisla, A.; Nagy, J.; Pop, N.; Zima, I.; Chablat, D.; et al. Development of an innovative parallel robot used in laparoscopic pancreatic surgery. In Proceedings of the 14th IFToMM International Symposium on Science of Mechanisms and Machines, Brasov, Romania, 23–25 October 2025; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Herbuś, K.; Ociepka, P. Verification of operation of the actuator control system using the integration the B&R Automation Studio software with a virtual model of the actuator system. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2017; Volume 227, p. 012056. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, C.R.; Stylopoulos, N.; Jackson, P.G.; Howe, R.D. The benefit of force feedback in surgery: Examination of blunt dissection. Presence Teleoperators Virtual Environ. 2007, 16, 252–262. [Google Scholar]

- Ameler, T.; Warzecha, M.; Hes, D.; Fromke, J.; Schmitz-Stolbrink, A.; Friedrich, C.M.; Blohme, K.; Brandt, L.; Brungel, R.; Hensel, A.; et al. A Comparative Evaluation of SteamVR Tracking and the OptiTrack System for Medical Device Tracking. In Proceedings of the Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, Berlin, Germany, 23–27 July 2019; pp. 1465–1470. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, J.M.; Pitt, B.; Kuntz, A.; Granna, J.; Kavoussi, N.L.; Nimmagadda, N.; Barth, E.J.; Herrell, S.D.; Webster, R.J., III. Comparing the accuracy of the da Vinci Xi and da Vinci Si for image guidance and automation. Int. J. Med. Robot. Comput. Assist. Surg. 2020, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwartowitz, D.M.; Herrell, S.D.; Galloway, R.L. Toward image-guided robotic surgery: Determining intrinsic accuracy of the da Vinci robot. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2006, 1, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepolina, F.; Razzoli, R.P. An introductory review of robotically assisted surgical systems. Int. J. Med. Robot. Comput. Assist. Surg. 2022, 18, e2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yin, Y.; Zhou, H.; Fan, Y.; Yang, Y.; Gao, Q.; Li, P.; Gao, G.; Li, J. Recent advances in electrospinning techniques for precise medicine. Cyborg Bionic Syst. 2024, 5, 0101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmatz, F.; Beuß, F.; Sender, J.; Flügge, W. Use of human-robot collaboration to enhance process monitoring of mechanical joining. Procedia Manuf. 2020, 52, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al, G.A.; Martinez-Hernandez, U. Multimodal barometric and inertial measurement unit-based tactile sensor for robot control. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 23, 1962–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Simulation | Displacement of the Master Node [mm] | Applied Force on the Master Node [N] | Calculated Stiffness (F/u) [N/mm] | Maximum von Mises Stress [MPa] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation 1 | 0.27 | 15 | 55.56 | 52.19 |

| Simulation 2 | 0.51 | 15 | 29.41 | 19.36 |

| Simulation 3 | 0.25 | 15 | 60 | 24.48 |

| Simulation 4 | 3.11 | 15 | 4.82 | 67.67 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pusca, A.; Ciocan, R.; Gherman, B.; Ciocan, A.; Caprariu, A.; Al Hajjar, N.; Vaida, C.; Pisla, A.; Radu, C.; Cailean, A.; et al. Development and Experimental Evaluation of the Athena Parallel Robot for Minimally Invasive Pancreatic Surgery. Robotics 2026, 15, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics15020033

Pusca A, Ciocan R, Gherman B, Ciocan A, Caprariu A, Al Hajjar N, Vaida C, Pisla A, Radu C, Cailean A, et al. Development and Experimental Evaluation of the Athena Parallel Robot for Minimally Invasive Pancreatic Surgery. Robotics. 2026; 15(2):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics15020033

Chicago/Turabian StylePusca, Alexandru, Razvan Ciocan, Bogdan Gherman, Andra Ciocan, Andrei Caprariu, Nadim Al Hajjar, Calin Vaida, Adrian Pisla, Corina Radu, Andrei Cailean, and et al. 2026. "Development and Experimental Evaluation of the Athena Parallel Robot for Minimally Invasive Pancreatic Surgery" Robotics 15, no. 2: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics15020033

APA StylePusca, A., Ciocan, R., Gherman, B., Ciocan, A., Caprariu, A., Al Hajjar, N., Vaida, C., Pisla, A., Radu, C., Cailean, A., Tucan, P., Chablat, D., & Pisla, D. (2026). Development and Experimental Evaluation of the Athena Parallel Robot for Minimally Invasive Pancreatic Surgery. Robotics, 15(2), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics15020033