Kinematic Analysis and Workspace Evaluation of a New Five-Axis 3D Printer Based on Hybrid Technologies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

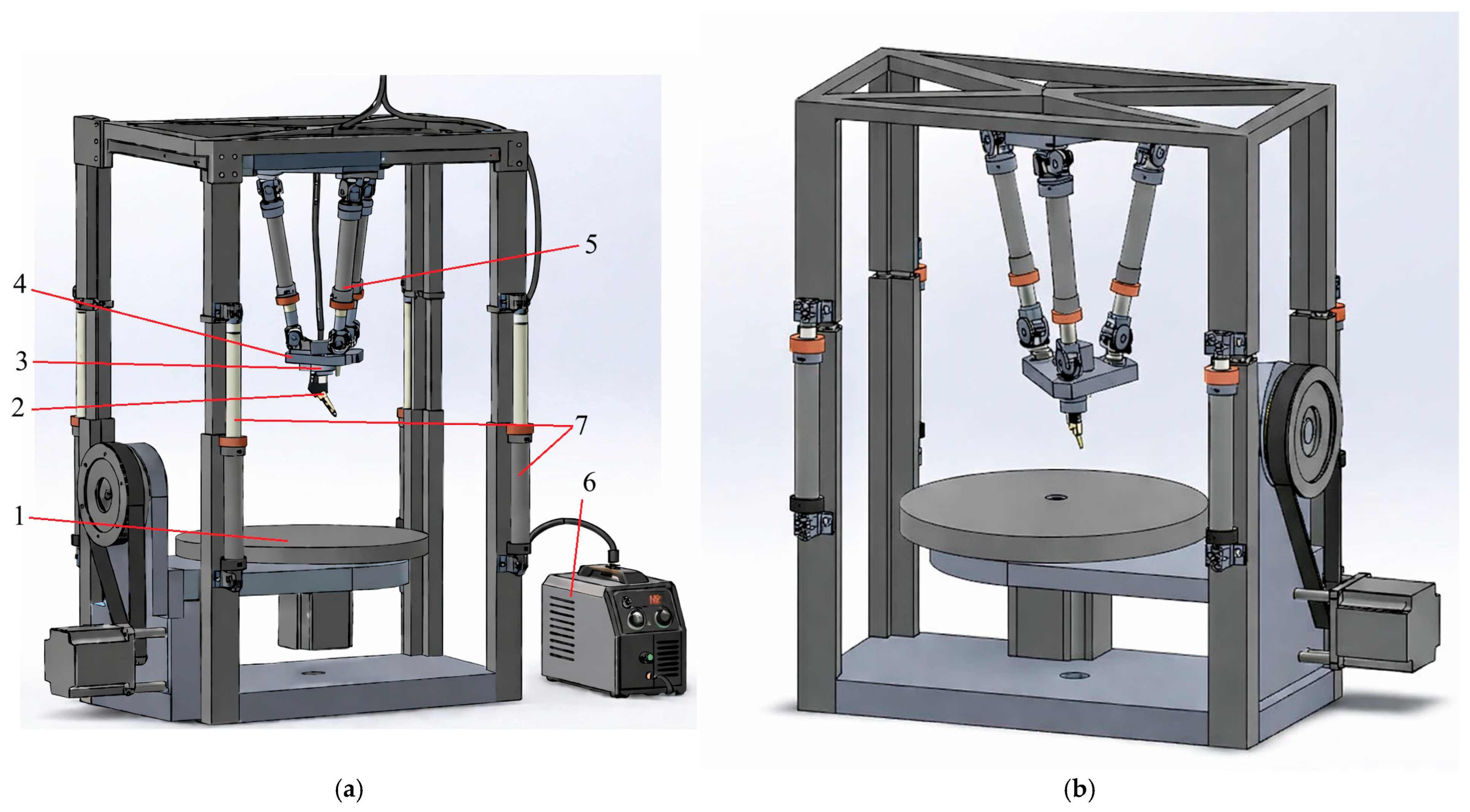

2.1. Geometry and Mobility

2.2. Inverse Kinematics Problem

- (1)

- (2)

- (3)

- (4)

2.3. Direct Kinematics Problem

2.4. Jacobian Matrices and Velocity Analysis

2.5. Singular Configurations

3. Results and Discussion

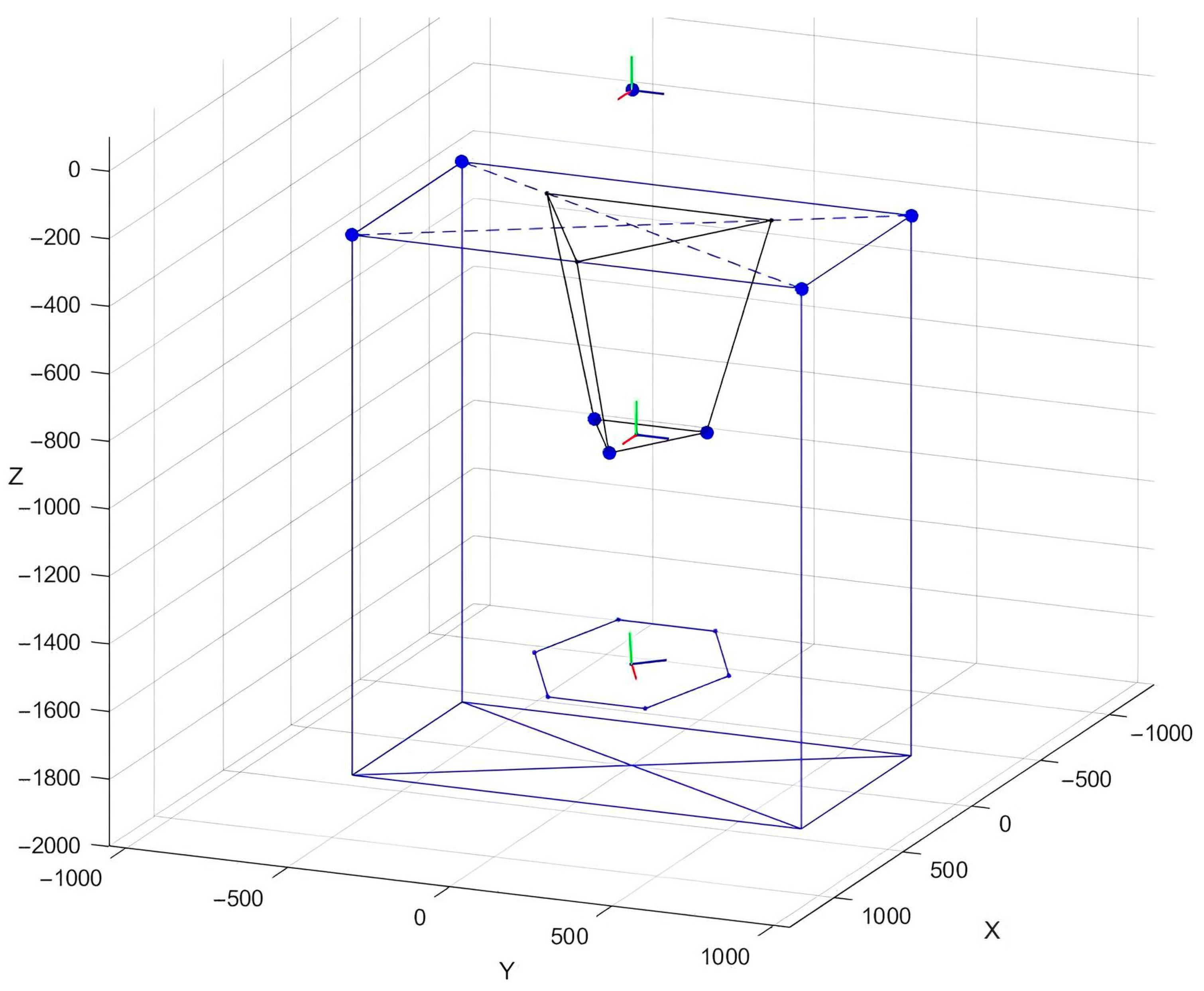

3.1. Numerical Results of Solving the Inverse and Direct Kinematics Problems

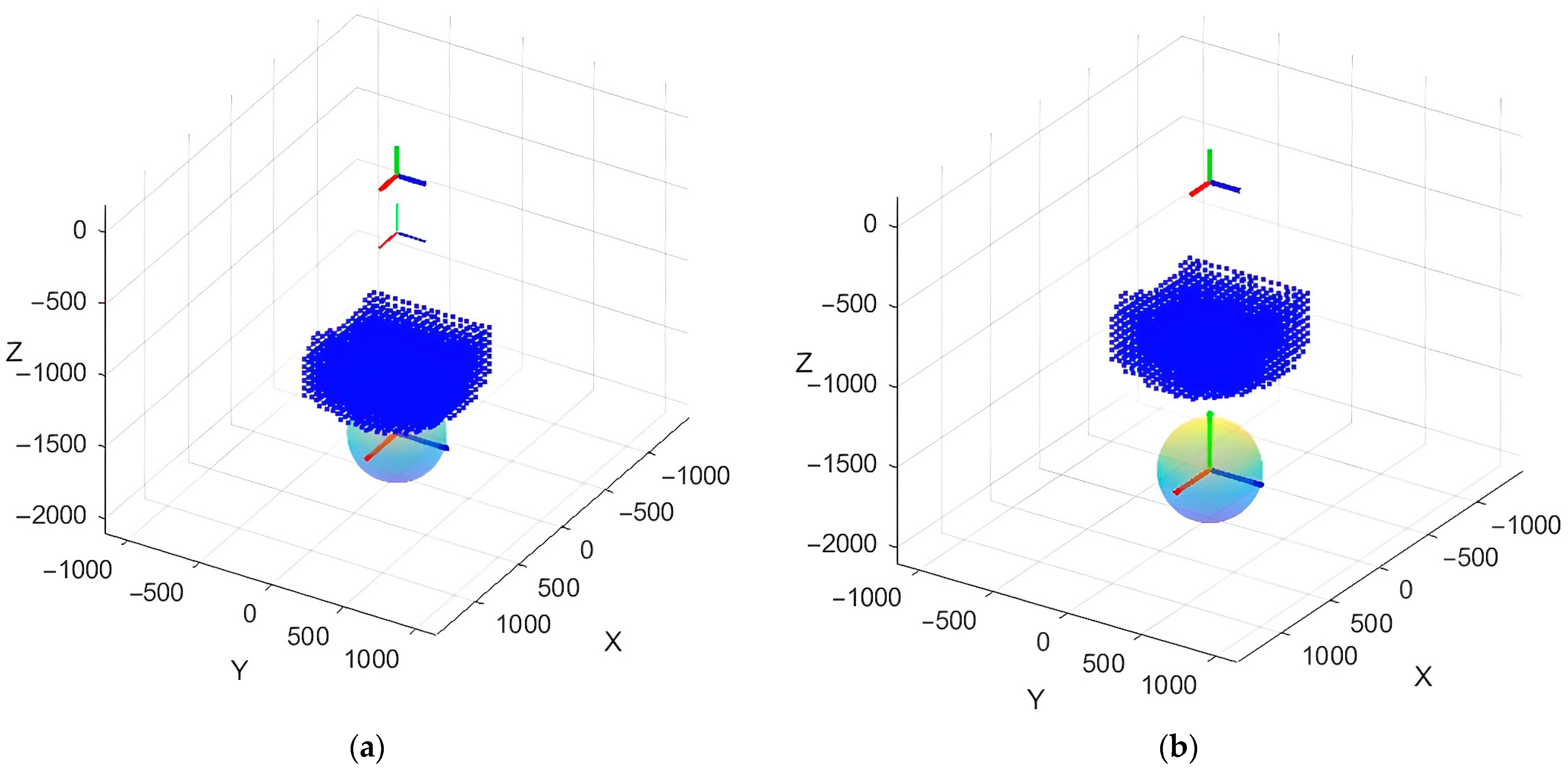

3.2. Workspace of the Multifunctional Mobile 3D Printer for Metal Printing

3.3. Numerical Examples of Solving the Inverse and Direct Velocity Problems

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shah, A.; Aliyev, R.; Zeidler, H.; Krinke, S. A Review of the Recent Developments and Challenges in Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing (WAAM) Process. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2023, 7, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alami, A.H.; Olabi, A.G.; Alashkar, A.; Alasad, S.; Aljaghoub, H.; Rezk, H.; Abdelkareem, M.A. Additive Manufacturing in the Aerospace and Automotive Industries: Recent Trends and Role in Achieving Sustainable Development Goals. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2023, 14, 102516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, M.; El Hassan, A.; Hussein, M.; Zaneldin, E.; Al-Marzouqi, A.H.; Ahmed, W. Characteristics of antenna fabricated using additive manufacturing technology and the potential applications. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renderos, M.; Girot, F.; Lamikiz, A.; Torregaray, A.; Saintier, N. Ni-Based Powder Reconditioning and Reuse for LMD Process. Phys. Procedia 2016, 83, 769–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, W.E. Metal Additive Manufacturing: A Review. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2014, 23, 1917–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, B.S.I.; Rosen, D. Additive Manufacturing Technologies, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Çam, G. Prospects of Producing Aluminum Parts by Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing (WAAM). Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 62, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahidin, M.R.; Yusof, F.; Rashid, S.H.A.; Mansor, S.; Raja, S.; Jamaludin, M.F.; Manurung, Y.H.; Adenan, M.S.; Hussein, N.I.S. Research Challenges, Quality Control and Monitoring Strategy for Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 24, 2769–2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, M.; Hai, K.; Khan, M.; Shekha, A.; Pervaiz, S.; Ali, S.M.; Abdul-Latif, O.; Salman, M. Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing (WAAM): Reviewing Technology, Mechanical Properties, Applications and Challenges. In Proceedings of the ASME International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition, Virtual, Online, 16–19 November 2020; ASME: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2020; Volume 84485, p. V02AT02A042. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, F. 3D Printing with Metals. Comput. Control Eng. J. 1998, 9, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glashier, T.; Kromanis, R.; Buchanan, C. Temperature-Based Measurement Interpretation of the MX3D Bridge. Eng. Struct. 2024, 305, 116736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, A.R.; Pagone, E.; Martina, F.; Priarone, P.C.; Settineri, L. Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing of Ti-6Al-4V Components: Effects of Deposition Rate on Cradle-to-Gate Economic and Environmental Performance. Procedia CIRP 2023, 116, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martina, F. What Happens When You Take the Powder out of AM? Charting the Rise of Wire-Based DED with WAAM3D. Metal AM 2022, 8, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Dharmendra, C.; Amirkhiz, B.S.; Lloyd, A.; Ram, G.J.; Mohammadi, M. Wire-Arc Additive Manufactured Nickel Aluminum Bronze with Enhanced Mechanical Properties Using Heat-Treatment Cycles. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 36, 101510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, H.; Correia, J.A.; Veljkovic, M.; Zhang, Y.; Berto, F.; de Jesus, A.M. Probabilistic Strain-Fatigue Life Performance Based on Stochastic Analysis of Structural and WAAM-Stainless Steels. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2021, 127, 105495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, R.C.; Kokare, S.; Oliveira, J.P.; Matias, J.C.; Godina, R. Life Cycle Assessment of Metal Products: A Comparison Between Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing and CNC Milling. Adv. Ind. Manuf. Eng. 2023, 6, 100117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pragana, J.P.M.; Sampaio, R.F.; Bragança, I.M.F.; Silva, C.M.A.; Martins, P.A.F. Hybrid Metal Additive Manufacturing: A state–of–the-art review. Adv. Ind. Manuf. Eng. 2021, 2, 100032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, B.; Richhariya, V.; Silva, M.; Vaz, A.; Lopes, S.F.; Carvalho, Ó. A review of hybrid manufacturing: Integrating subtractive and additive manufacturing. Materials 2025, 18, 4249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebbe, N.P.; Fernandes, F.; Sousa, V.F.; Silva, F.J. Hybrid manufacturing processes used in the production of complex parts: A comprehensive review. Metals 2022, 12, 1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, L.; Feldhausen, T.; Saleeby, K.S.; Saldana, C.; Kurfess, T.R. Prediction of Thermal Conditions of DED with FEA Metal Additive Simulation. In Proceedings of the ASME 2021 16th International Manufacturing Science and Engineering Conference, Virtual, Online, 21–25 June 2021; p. V001T01A022. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Huang, J.; Zheng, Y.; Hou, S.; Xu, S.; Ma, Y.; Li, L. Challenges in Topology Optimization for Hybrid Additive–Subtractive Manufacturing: A Review. Comput.-Aided Des. 2023, 161, 103531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, R.; Chen, X.; Sparks, T.; Liou, F. Industrial robot trajectory stiffness mapping for hybrid manufacturing process. Int. J. Robot. Autom. Technol. 2016, 3, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunaj, P.; Dolata, M.; Powałka, B.; Pawełko, P.; Berczyński, S. Design of an ultra-light portable machine tool. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 43837–43844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Nagaraja, K.M.; Zhang, R.; Malik, A.; Lu, H.; Li, W. Integrating Robotic Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing and Machining: Hybrid WAAM Machining. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 129, 3247–3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neugebauer, R. (Ed.) Parallelkinematische Maschinen: Entwurf, Konstruktion, Anwendung; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Merlet, J.P. Parallel Robots; Chapter 3; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2000; pp. 48–62. [Google Scholar]

- Baigunchekov, Z.Z.; Kaiyrov, R.A. Direct Kinematics of a 3-PRRS Type Parallel Manipulator. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Robot. Res. 2020, 9, 967–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.J.; Wang, J.S. Parallel Kinematics: Type, Kinematics, and Optimal Design; Chapters 1 and 2; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 3–77. [Google Scholar]

- McAree, P.R.; Selig, J.M. Constrained Robot Dynamics II: Parallel Machines. J. Robot. Syst. 1999, 16, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, M.; Zhang, D.; Liu, X.J.; Xie, Z. A review of parallel kinematic machine tools: Design, modeling, and applications. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2024, 196, 104118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, F.; Lizarralde, N.; Lizarralde, F. Coordinated motion control of a Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing robotic system for multi-directional building parts. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.14858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Wang, P.; Hou, Z.; Hu, B.; Sui, C.; Han, J. Kinetostatic analysis of a novel 6-DoF 3UPS parallel manipulator with multi-fingers. Mech. Mach. Theory 2014, 78, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadi, B.N.R.; Vakilzadeh, M. Natural frequency analysis of a planar parallel mechanism with task space redundancy for high-precision milling. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2025, 47, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Zhang, D.; Tian, C. An approach for modeling and performance analysis of three-leg landing gear mechanisms based on the virtual equivalent parallel mechanism. Mech. Mach. Theory 2022, 169, 104617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, M.; Herrero, S.; Altuzarra, O.; Ceccarelli, M. Kinematic analysis and multi-objective optimization of a 3-UPR parallel mechanism for a robotic leg. Mech. Mach. Theory 2018, 120, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassani, A.; Khalilpour, S.A.; Bataleblu, A.; Taghirad, H.D. Full Dynamic Model of 3-UPU Translational Parallel Manipulator for Model-Based Control Schemes. Robotica 2022, 40, 2815–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, L.W.; Joshi, S. Kinematics and optimization of a spatial 3-UPU parallel manipulator. J. Mech. Des. 2000, 122, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petro, P.; Shi, X.; Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Yin, B.; Zhou, H.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, B.; Wang, Z. Enhancing Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing for Maritime Applications: Overcoming Operational Challenges in Marine and Offshore Environments. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautio, S.; Valtonen, I. Supporting Military Maintenance and Repair with Additive Manufacturing. J. Mil. Stud. 2022, 11, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, S.; Wirtz, A.; Becker, J.; Aurich, J.C.; Brecher, C. Connected, Digitalized Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing: Utilizing Data in the Internet of Production to Enable Industrie 4.0. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 20771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, L.-W. Kinematics of a Three-DoF Platform with Three Extensible Limbs. In Recent Advances in Robot Kinematics; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1996; pp. 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, K.S.; Gonzales, R.C.; Lee, C.S.G. Robotics: Control, Sensing, Vision, and Intelligence; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1987; p. 580. [Google Scholar]

- Raspall, F.; Araya, S.; Pazols, M.; Valenzuela, E.; Castillo, M.; Benavides, P. Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing for Widespread Architectural Application: A Review Informed by Large-Scale Prototypes. Buildings 2025, 15, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DIN 808: Universal Joints with Needle or Friction Bearings, Technical Specification (PDF). Available online: https://www.elesa-ganter.com/siteassets/PDF/EN/DIN%20808.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Huang, K.H.; Menon, N.; Jamieson, C.D.; Basak, A. Probabilistic Knowledge Transfer of Melt Pool Properties Between Wire- and Powder-Based Laser-Directed Energy Deposition. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 138, 315–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Radius A | 400 | mm | |

| Radius B | 200 | mm | |

| Initial X coordinate | 100 | mm | |

| Initial Y coordinate | 100 | mm | |

| Initial Z coordinate | −1000 | mm | |

| Angle 1 | 0 | ° | |

| Angle 2 | 120 | ° | |

| Angle 3 | 240 | ° | |

| Offset | d | −400 | mm |

| Rotation angle Y | 10 | ° | |

| Rotation angle Z | 30 | ° | |

| Length 1 actuator | 600 | mm | |

| Length 2 actuator | 600 | mm | |

| Length 3 actuator | 600 | mm | |

| X coordinate of point K | 0 | mm | |

| Y coordinate of point K | 0 | mm | |

| Z coordinate of point K | −1700 | mm | |

| Parameter | 300 | mm |

| (mm) | (mm) | (mm) | (mm/s) | (mm/s) | (mm/s) | (mm/s) | (mm/s) | (mm/s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 300 | 300 | −1000 | 0 | 0 | −50 | 88.4652 | 81.9479 | 69.5644 |

| 2 | 300 | 300 | −1000 | −50 | −50 | −50 | 58.9768 | 45.9731 | 18.9444 |

| 3 | 300 | 300 | −1000 | 50 | 50 | 50 | −58.9768 | −45.9731 | −18.9444 |

| 4 | −300 | 300 | −1000 | 50 | 50 | 50 | −83.6660 | −98.6919 | −58.6662 |

| 5 | −300 | 300 | −1000 | −50 | 50 | 50 | −23.9046 | −67.6861 | −33.3462 |

| 6 | −300 | 300 | −1000 | 50 | 0 | 0 | −29.8807 | −15.5029 | −12.6600 |

| 7 | −300 | 300 | −1000 | 0 | 50 | 0 | 17.9284 | 9.8284 | 29.9539 |

| 8 | −300 | −300 | −1000 | −50 | −50 | −50 | 119.5229 | 118.5741 | 118.3488 |

| 9 | −300 | −300 | −1000 | +50 | +50 | −50 | 23.9046 | 33.3462 | 67.6861 |

| 10 | −300 | −300 | −1000 | −50 | −50 | +50 | −23.9046 | −33.3462 | −67.6861 |

| 11 | 0 | 0 | −1000 | 0 | 0 | −50 | 94.8683 | 94.8683 | 94.8683 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mustafa, A.; Kaiyrov, R.; Nugman, Y.; Sagyntay, M.; Albanbay, N.; Zhauyt, A.; Turgunov, Z.; Dyussebayev, I.; Lei, Y. Kinematic Analysis and Workspace Evaluation of a New Five-Axis 3D Printer Based on Hybrid Technologies. Robotics 2026, 15, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics15010016

Mustafa A, Kaiyrov R, Nugman Y, Sagyntay M, Albanbay N, Zhauyt A, Turgunov Z, Dyussebayev I, Lei Y. Kinematic Analysis and Workspace Evaluation of a New Five-Axis 3D Printer Based on Hybrid Technologies. Robotics. 2026; 15(1):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics15010016

Chicago/Turabian StyleMustafa, Azamat, Rustem Kaiyrov, Yerik Nugman, Mukhagali Sagyntay, Nurtay Albanbay, Algazy Zhauyt, Zharkynbek Turgunov, Ilyas Dyussebayev, and Yang Lei. 2026. "Kinematic Analysis and Workspace Evaluation of a New Five-Axis 3D Printer Based on Hybrid Technologies" Robotics 15, no. 1: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics15010016

APA StyleMustafa, A., Kaiyrov, R., Nugman, Y., Sagyntay, M., Albanbay, N., Zhauyt, A., Turgunov, Z., Dyussebayev, I., & Lei, Y. (2026). Kinematic Analysis and Workspace Evaluation of a New Five-Axis 3D Printer Based on Hybrid Technologies. Robotics, 15(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics15010016