To this end, this section is dedicated to quantitatively and qualitatively evaluating the impact and benefits of said reconfiguration capability. Specifically, the effect of redundancy, enabled by the geometric reconfiguration of the parameter R, will be analyzed on two fundamental aspects of the robot’s performance: first, the extent and shape of the reachable workspace volume, and second, the potential improvement in kinematic performance indices, such as velocity manipulability, throughout said space. To do this, the results obtained for the Delta robot operating with its active reconfiguration capability (where R is variable and its value is selected using the index for each point in the workspace) will be contrasted with its non-reconfigurable counterpart. The latter is considered a particular case of the reconfigurable robot where the parameter R is kept fixed at , a value representative of the original design or a standard non-reconfigurable configuration. This evaluation is fundamental to validate the hypothesis that reconfigurability not only expands the operational capabilities of the Delta robot but also allows for a significant optimization of its kinematic behavior.

6.1. Maximum Reachable Volume

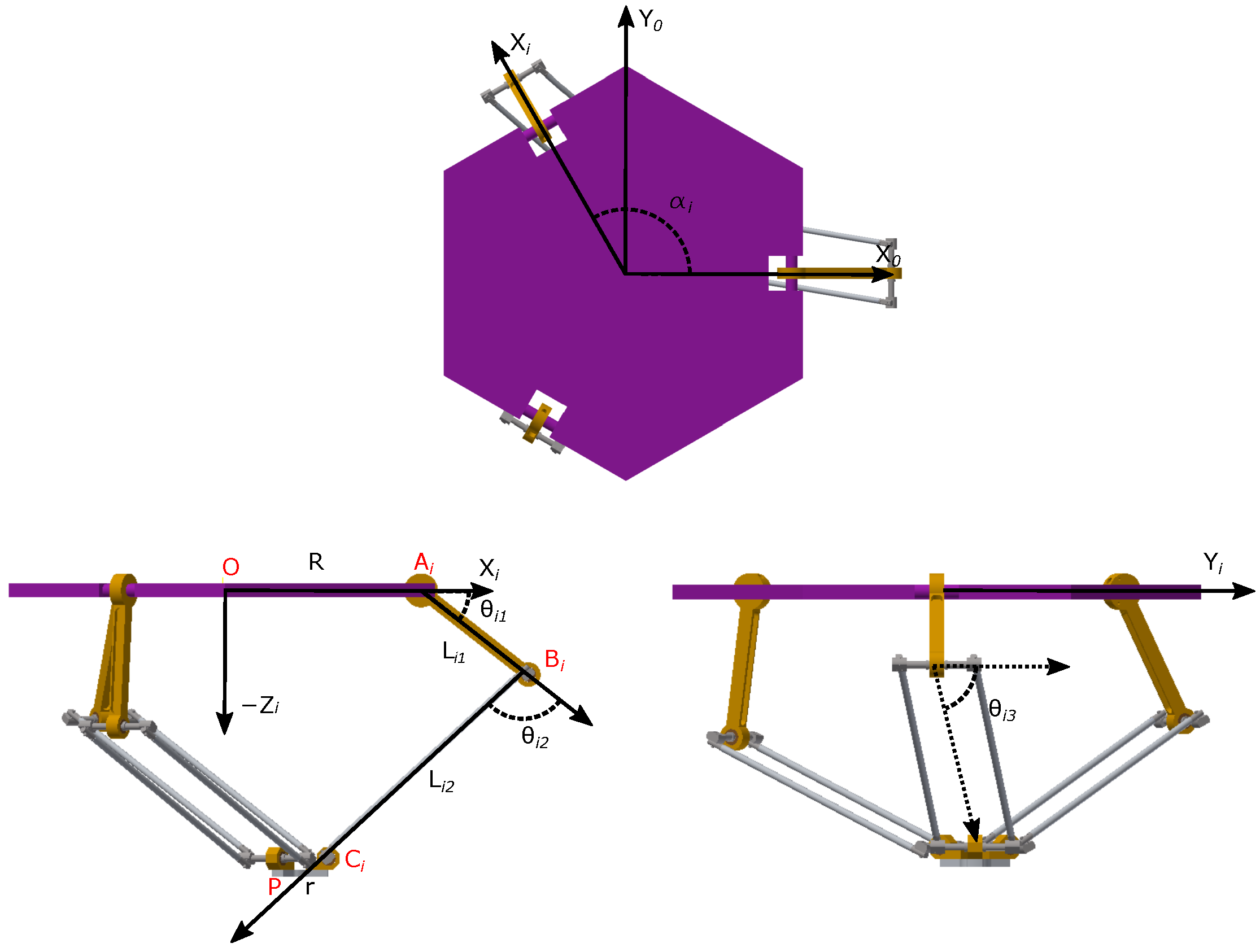

To quantify the reachable workspace of the reconfigurable Delta robot, a numerical discretization approach was employed. The search space is bounded by an enclosing prism defined by the Cartesian coordinates m and m. This volume was discretized into a high-resolution grid of points, corresponding to a spatial resolution of 0.002 m between adjacent positions. This resolution was selected based on a convergence analysis to ensure that the resulting volume measurements are numerically stable and independent of the grid density, while maintaining an efficient computational cost for the optimization process. The workspace volume is determined by evaluating the ratio between the number of points that satisfy the inverse kinematic constraints and the total number of points within the bounding prism and multiplying this ratio by the total volume of the prism.

The application of this methodology reveals a significant expansion of the operational range due to the reconfiguration capability. The workspace volume for the standard configuration (with fixed R) was measured at 0.075 m3, whereas the reconfigurable Delta robot achieved a volume of 0.137 m3. These results represent a 82% increase in the reachable workspace.

Figure 7a shows the workspace of the reconfigurable robot, while

Figure 7b shows the case without reconfiguration. In these images, we can observe the shapes of the volumes and how the reconfigurable robot gains volume in all directions; in particular, a significant gain is observed in the upper part of the workspace.

6.2. Performance Comparison

To analyze the impact of geometric reconfiguration on the robot’s kinematic behavior, a comparative study is presented between the reconfigurable Delta robot (RDR) and its non-reconfigurable counterpart (ODR). The ODR serves as a baseline with a fixed base radius of , while the RDR adapts its geometry at each point to maximize the singularity-sensitive index .

The performance evaluation is conducted using the same grid-based discretization applied for the workspace volume estimation, consisting of points. For every reachable coordinate within this grid, the inverse geometric problem is solved. In the case of the RDR, this involves a systematic search for the optimal reconfiguration parameter R by sampling the range [0.138, 0.495] m with a high-resolution step of 0.001 m. At each configuration, Jacobian-based performance indices—such as velocity manipulability, minimum singular values, and the condition number—are computed and recorded. This methodology allows for a comprehensive mapping of kinematic dexterity across the entire workspace, providing a robust statistical basis for comparing the operational safety and mobility of both robot architecture.

Figure 8 shows heatmaps representing the distribution of the velocity manipulability index,

, over different

planes (cross-sections of the workspace at different

z heights). The subfigures in the left column (a, b, c) correspond to the reconfigurable Delta robot, where for each point

, the value of

R that maximizes the

index has been selected. The subfigures in the right column (d, e, f) illustrate the behavior for the robot with a fixed

. In these maps, warmer colors (tending to red/yellow on the provided color scale) indicate higher values of

(greater ability to transmit velocities), while colder colors (tending to dark blue) represent lower values.

Analyzing the planes at a height of

(comparing

Figure 8a, reconfigurable, with

Figure 8d, non-reconfigurable), it is observed that the reconfigurable robot not only covers a larger cross-sectional area but also presents extensive regions with high and more homogeneous values of

. For

(

Figure 8b,e), the advantage of the reconfigurable robot in terms of area with good manipulability remains clear; the ability to adjust R allows it to maintain superior performance. Even in lower regions such as

(

Figure 8f, non-reconfigurable), where the robot with a fixed

R may have a very restricted operating space or significantly degraded manipulability, the reconfigurable robot (whose operability at this depth is inferred to be superior due to the general expansion of the workspace shown in

Figure 7a) can select an R that allows it to operate with better performance.

In general,

Figure 8 demonstrates that reconfigurability not only expands the geometrically reachable workspace but, when combined with the

optimization criterion, allows the robot to operate with an improved or more consistently maintained velocity manipulability

across a larger portion of this volume. The global quantitative data presented in

Table 6 for

(where RDR is Reconfigurable Delta Robot and ODR is Original/Non-Reconfigurable Delta Robot with

) support these observations. While the mean value of

may be similar between both configurations (0.6380 for RDR vs. 0.7036 for ODR), the minimum value of

: for the RDR, it is 0.0635, while for the ODR with

, it is merely 0.0006. This indicates that the reconfigurable robot, thanks to the optimization of

R using

, much more effectively avoids configurations of very low velocity manipulability. Additionally, the maximum value of

reached by the RDR (1.1538) is marginally higher than that of the ODR (1.1375), suggesting a higher kinematic performance ceiling. Regarding the force performance, the mean value of

is marginally lower (1.7976) for RDR vs. 1.82.31 for ODR), the minimum value of

is 0.8666 for the RDR, while for the ODR, it is 0.8790. However, the maximum value of

is 15.7337 for the RDR, while for the ODR is 1748.7 which is a very high value indicating an ill-conditioned configuration. This indicates that the reconfigurable robot, thanks to the optimization of

R using

, much more effectively avoids ill-conditioned configurations.

When velocity performance is prioritized by setting

, the results in

Table 7 indicate that the minimum, maximum, and mean values of

are higher for the RDR robot than for the ODR robot, while force performance remains satisfactory. Conversely, setting

, which favors force performance at the expense of velocity, yields superior force performance for the RDR robot compared to the ODR robot, while maintaining acceptable velocity performance, as shown in

Table 8. These findings demonstrate that the proposed index can be tuned to emphasize either velocity or force performance according to design requirements.

The proposed index exhibits smooth and continuous variation across the workspace, as shown in the heat maps, indicating a continuous sensitivity relationship between the index and the parameters. Minor modeling errors or assembly tolerances would therefore induce only limited changes in the index value, consistent with the numerical robustness of Jacobian-based measures away from singular boundaries. While a formal sensitivity analysis could be addressed in future work, the observed behavior provides qualitative evidence of stability under small perturbations.

Based on the data shown in the tables and figures presented in this section, a substantial improvement can be observed in both the workspace volume and the performance indices for the reconfigurable robot when compared to a standard fixed configuration. The distribution of the velocity manipulability index values is also more favorable. Regarding the feasibility of the reconfiguration mechanism used in this work, it was previously demonstrated in [

10], where the design of the mechanism was presented, and in [

23] where several controls were proposed and subsequently validated through experimental testing. Taking these facts into account, it can be concluded that geometric reconfiguration, managed through the

optimization criterion, is effective in improving both the reach and the kinematic characteristics of the Delta robot.