Abstract

We introduce the pose-graph topological integrity, an approach designed to assess the correctness of pose graphs in simultaneous localization and mapping. Traditional methods assessed map quality according to the optimality criteria based on pose graphs, which often rely on heuristically defined edge information matrices. These methods cannot capture the inconsistencies between the constructed map and the actual environment. In contrast, the proposed approach utilizes heat kernel signatures to directly quantify topological inconsistencies between the pose graph and support graph derived from free-space constraints. This enables a multi-scale and per-vertex evaluation of topological integrity. The experiments on real-world datasets demonstrate that the proposed metric can detect topological errors and distinguish between serious ones and harmless ones.

1. Introduction

In simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM), evaluating the correctness of the map that represents the robot’s explored space is important. As the robot moves, the keyframes are inserted as nodes in pose graphs, and the relative poses between the keyframes are added as edges. Because error accumulation is unavoidable, pose-graph optimization (PGO) is applied to refine the trajectories and generate globally consistent maps [1,2]. However, the quality of the resulting map fundamentally depends on the structural correctness of the underlying pose graph. This facilitates the need for a quantitative evaluation of pose-graph correctness.

Traditional methods for assessing map quality have focused on covariance-based optimality criteria. Major criteria use measures such as D-opt, E-opt, and T-opt, which are derived from the Fisher information matrix (FIM) [3,4]. While these methods quantify the uncertainty of pose graphs, they often rely on heuristically determined covariance settings and accurate calibrated sensor parameters which are often hard to obtain. Moreover, an uncertainty assessment does not indicate whether a pose graph accurately reflects the true topological structure of an environment, which is a key factor in ensuring map correctness. To be specific, covariance-based uncertainty criteria only depend on local linearized measurement models and their assumed noise statistics. They summarize how precisely the relative motions between poses are estimated, but they do not encode whether the resulting general map has accurate global connectivity. In practice, topologically incorrect maps can appear “well constrained” when incorrect loop closures are assigned over-confident covariances. This mismatch motivates the need for a dedicated topology-oriented metric that can directly evaluate the consistency between the map representation and the true environment.

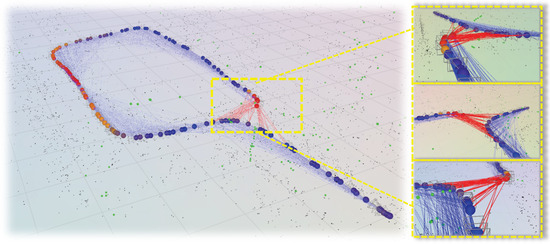

Although ensuring topological correctness is crucial, it is a fragile practice, as error accumulation and improper data association may introduce flaws into the map’s topology. For instance, unexpected trajectory collisions due to drifts and false or absent loop closures may ultimately change the topology of the explored space. Figure 1 shows an example where a loop closure is missed. This makes it particularly important for active SLAM and multiagent SLAM, where agents must build a consistent and accurate map for the explored space [5,6,7]. However, existing methods that measure map topology tend to be implicit and indirect. For example, frameworks such as TopoMap [8] and neural topological [9] SLAM construct new topological graphs on top of the SLAM output (e.g., convex voxel clusters), and their representations depend on system-specific processing, thresholding, or training. As a result, they do not provide a simple quantitative score that can be applied directly to an arbitrary pose graph and compared across different systems or datasets. Moreover, these approaches focus on constructing or exploiting auxiliary topological structures rather than explicitly verifying whether the original pose graph produced by SLAM is topologically consistent with the true connectivity of the explored free space.

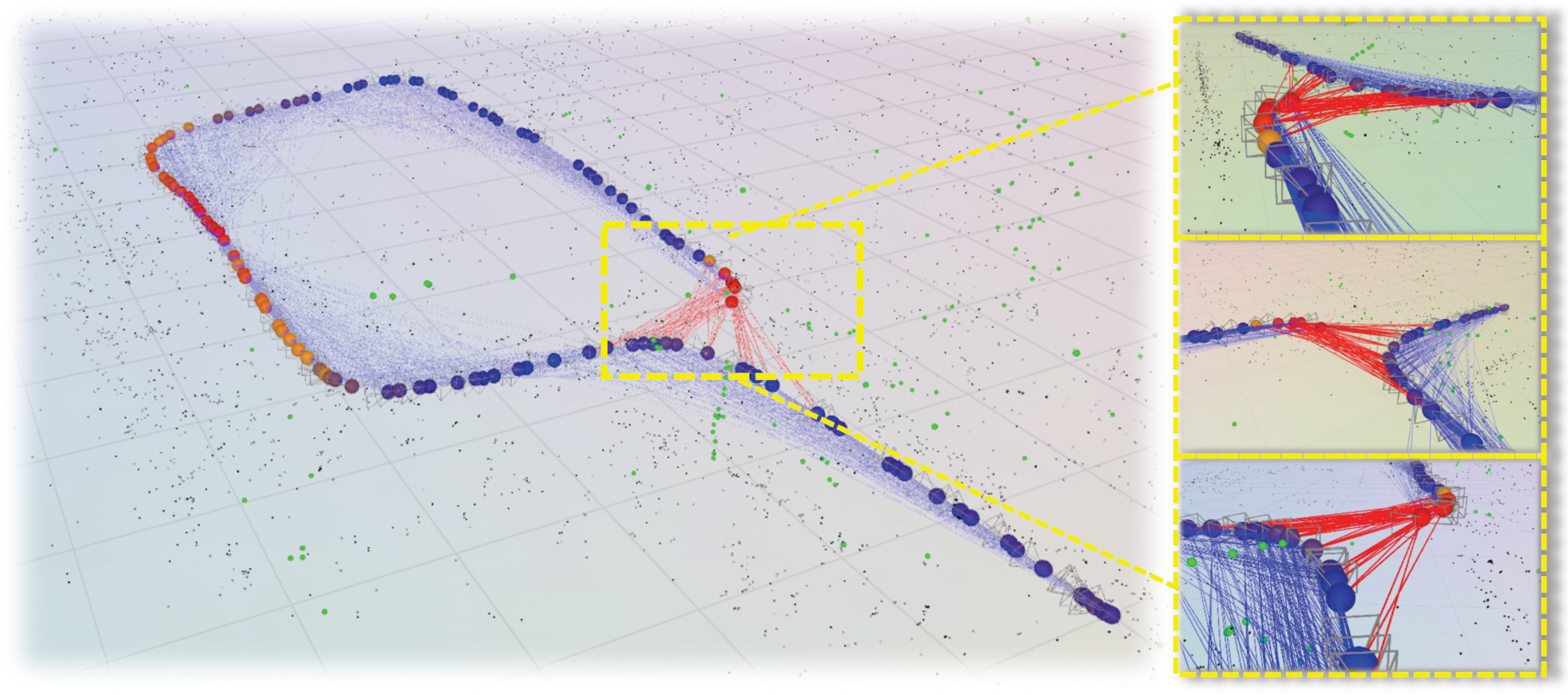

Figure 1.

Topological failure example in SLAM pose graph. Blue edges show the pose-graph connections; red edges indicate the additional constraints required to restore consistency; node colors indicate the proposed PGTI score, where brighter colors exhibit larger inconsistencies. PGTI evaluates how well the pose graph represents the true spatial topology. Yellow dotted frames are zoomed-in views of the target areas.

To address these challenges, we propose a measurement framework, termed pose-graph topological integrity (PGTI). Leveraging the relation between error propagation in pose-graph optimization and heat diffusion, PGTI employs heat kernel signature (HKS) [10] to capture topological structure. We introduce a support graph combining the free-space constraints with the original pose graph to represent the topology of the observed space. The PGTI then directly compares the topological features extracted from the pose graph with those from the support graph. By introducing this novel topological perspective, PGTI consequently manages to overcome the limitations of covariance-based methods.

The choice of HKS is not arbitrary. Once the PGO problem is linearized, the Gauss–Newton iterations propagate residual errors along the pose graph according to the graph Laplacian, which is the generator of a heat diffusion process. In this view, injecting a perturbation at a vertex and observing how it spreads over time is equivalent to studying how estimation errors propagate throughout the pose graph. The HKS provides a compact multi-scale summary of this diffusion behavior at each vertex. By comparing the HKS on the original pose graph and on the free-space support graph, PGTI directly checks whether the pose graph is an accurate topological proxy of the explored free space rather than relying on indirect scalar indices of uncertainty.

Our contributions are summarized as follows:

- We introduce PGTI, a multi-scale measure that helps assess the correctness of pose graphs, which provides both graph-level and per-vertex measurements.

- We propose a simple map topology representation combining the pose graph with the free-space constraints.

- We establish and exploit a theoretical connection between error propagation in pose graphs and heat diffusion on graphs to derive a heat-kernel-based topological integrity metric.

In the experiment section, we demonstrate that the proposed metric is more responsive and practical in comparison with existing methods.

2. Related Works

2.1. Pose Graphs and Map Structure

Pose graphs provide a topological representation of the environment, where nodes represent the robot poses and edges encode the relative transformations between them. These graphs are incrementally constructed as new data are incorporated. However, inevitable error accumulation may lead to problems such as scale drifts [11]. The PGO is proposed to refine the trajectory and maintain global consistency [1,12,13].

Nonetheless, ensuring the correctness of a pose graph is difficult. While loop-closure detection and PGO can mitigate drift, they cannot guarantee that the topology of the pose graph accurately reflects the topology of the explored space. Unexpected trajectory collisions and incorrect data associations may distort the graph structure, leading to inaccurate or misleading optimization results [14,15,16,17]. This highlights the need for evaluation methods that assess map correctness from a topological perspective.

2.2. Covariance-Based Map Optimality in SLAM

Traditionally, map quality in SLAM is assessed using covariance-based uncertainty analysis. Classical approaches estimate uncertainty through covariance ellipsoids [18,19] by applying optimality criteria from the theory of optimal experimental design (TOED) [5,20,21]. These methods evaluate map accuracy by analyzing the eigenvalues of the FIM using criteria such as D-, T-, and E-optimality.

While covariance-based methods have been successfully demonstrated in many scenarios, they face significant challenges in practical, large-scale applications. For instance, the eigenvalue decomposition of large covariance matrices is computationally expensive. To overcome this issue, recent studies have explored graph-based optimality criteria that approximate covariance-based metrics using the topology of the pose graph [22], establishing a mathematical connection between the FIM and the graph Laplacian. This enables faster and more scalable computations. Thanks to this acceleration, many SLAM algorithms have fully exploited these benefits [23,24,25].

In addition, they do not fundamentally resolve another limitation of covariance-based methods, which is the process of covariance estimation. In many practical systems, this process is heuristic-based rather than rigorously derived or calibrated. For example, the information matrices (inverse of covariance) are often set as (scaled) identity matrices for simplicity in practical visual SLAM systems [26,27]. While this is reasonable and convenient for optimization, it implies that the resulting uncertainties do not reflect the true statistics of the estimation problem, which undermines the reliability of the uncertainty analysis.

2.3. Map Topology in Graph-Based SLAM and Navigation

Pose graphs in SLAM inherently encode some topological constraints, and there are many recent works demonstrating that graph topology is a powerful proxy for uncertainty and decision making. Chen et al. [28] study anchor selection for pose graphs to reformulate SLAM optimizations as a cardinality-constrained submodular maximization problem with efficient greedy algorithms and performance guarantees. Kitanov and Indelman [29] propose topological belief space planning, which uses a lightweight topological signature of the future-factor graph to rank candidate actions for active SLAM. Recent surveys on vision-based navigation and perception review a broad range of SLAM strategies that handle topological information in the form of pose graphs [30].

A core challenge is that a pose graph primarily captures the connectivity of a robot’s trajectory and measurements, rather than the connectivity of the surrounding free space. As a result, even when the estimated trajectory appears locally consistent, the pose graph can still be topologically inconsistent with the actual environment in a global sense. For example, noise in the sensor data and accumulated error may lead to inaccuracies in mapping, which further influence pose-graph connections [31]. Perceptual aliasing is another common issue that causes erroneous loop closures, damaging graph topology [14,32]. Therefore, assessing a map topologically becomes important [33].

There also exist several methods that explicitly exploit map topology using graph-theoretic formulations. Vallvé et al. [34] address how to preserve key topological edges after sparsification, and Mu et al. [35] introduced a topological feature graph to balance exploration and loop closure based on entropy metrics. Moreover, several mapping frameworks have been introduced to enhance the topology. Topomap transforms sparse visual features into a 3D topological map of convex free-space clusters for efficient path planning [8]. PRISM-TopoMap performs online topological mapping by building a graph of locally aligned locations using multimodal place recognition and scan matching without relying on a global metric map [36]. NavTopo leverages such topological maps within a full navigation pipeline, combining graph-based high-level planning with local metric planning to achieve memory-efficient navigation in large environments [37]. Some neural mapping procedures, which combine SLAM output, topological structures, and deep reinforcement learning techniques, have also been proposed [9,38,39]. Visual Graph Memory (VGM) introduces an unsupervised graph-structured memory, where nodes store image embeddings and edges encode reachability, and a graph-convolutional policy reads from this memory to act without explicit metric poses [40]. More recently, Zhao et al. [41] propose a SLAM-free framework that constructs a semantic–probabilistic topological map from purely visual inputs, based on advances in vision–language models (VLMs), and combines hierarchical vision–language perception with coarse-to-fine semantic planning.

Although these methods explicitly incorporate topological structure, they focus on constructing or exploiting new topological representations for navigation and exploration. Their topological representations rely on system-specific heuristics, thresholds, or training objectives. In addition, they do not explicitly and directly verify whether the underlying SLAM pose graph is topologically consistent with the true free-space connectivity of the environment, which is what we address in this work.

In this work, we build upon these insights and introduce PGTI. Unlike previous methods, PGTI uses a direct topology representation and enables explicit comparison between the pose-graph structure and the actual topology of the explored space. This provides a more robust and generalizable framework for map-correctness evaluation.

3. Notations and Preliminaries

In this section, we provide some related notations and preliminary information to facilitate the subsequent discussion.

3.1. Notations for Map Representation

A pose graph is denoted as , where and are sets of vertices and edges. Typically, each vertex corresponds to the i-th keyframe in the map, and stands for the edge connecting and . Each edge is weighted with an information matrix . represents the number of vertices, and is the number of edges in the pose graph. In addition, each vertex has neighboring landmarks represented as , which includes all landmarks connected with and all other vertices connected with .

The pose of each vertex is represented as , and each edge is related to a relative measurement between vertices and , denoted as . The parameters , , and are typically represented as elements of Lie groups such as , , and .

The notations used in map representations and PGO derivations are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Main notation and symbols for map representation and pose-graph optimization.

3.2. Formulation of PGO

Given the notations, we are now able to obtain a formal definition of PGO. We formulate PGO as follows:

where represents the logarithm map, and denotes the vectorization of the corresponding Lie algebra element.

3.3. Brief Introduction of HKS

The HKS is a descriptor that captures the intrinsic topological properties of a graph by modeling the heat diffusion over its structure [10]. Given a graph with a graph Laplacian , the heat diffusion inside is calculated as follows:

where represents the temperature distribution at time t. The heat kernel is then given by . Given that is the eigen system of (denoted as for simplicity), the scaled HKS at vertex is defined as [10]

where are logarithmically spaced time steps, and is the scaled version of , defined as

According to [10], the smaller steps highlight more local features, while the larger steps reflect features associated with the broader topological structure.

Generally speaking, the HKS provides a compact multi-scale descriptor of how pose-graph errors, viewed as diffusing heat, propagate over time from each vertex in our context.

4. Heat Diffusion and PGO

In this section, we establish a relation between the heat diffusion process on the graphs and the error propagation during PGO. The points we are aiming to derive are that (1) PGO is a relative consensus problem on nonlinear spaces, and (2) a relative consensus problem is equivalent to a heat diffusion process with external forcing terms.

4.1. Relative Consensus Problem and PGO

A consensus problem models how a group of agents (vertices) agree with the local interactions [42]. Given a graph , where each vertex holds a state , let the weight for edge be ; the consensus of can be described as

We extend this definition to make the difference between connected agents match a predefined value . We call this general form the relative consensus problem. This leads to the following definition:

Equation (6) can be interpreted as a linear approximation of the PGO problem under the assumption of negligible rotational components. In practice, the rotations in the PGO could not be sufficiently small, thus requiring the extension of Equation (6) to nonlinear spaces. PGO can, thus, be expressed as a generalized relative consensus problem in nonlinear spaces:

where denotes the geodesic distance on a certain manifold .

4.2. Consensus Problem as a Heat Diffusion Process

The update for in the standard consensus problem Equation (5) is . By stacking these into the matrix form, we can obtain , where is the Laplacian matrix. This result aligns with Equation (2), which draws an equivalence between the standard consensus problem and the heat diffusion process on graphs.

For the relative consensus problem, we rewrite the problem using an incidence matrix , where each row corresponds to an edge. For edge , the corresponding row of has a value at column i, at column j, and zeros elsewhere (we henceforth omit edge weights for simplicity). Then, the stacked differences can be written as . Then, we define the objective function as

By applying the gradient descent, we obtain

One may easily verify that is the graph Laplacian. Therefore, Equation (9) matches the heat diffusion with the external forcing term, as . here is the constant forcing term. Thus, solving relative consensus is equivalent to solving the steady-state heat diffusion equation with a constant forcing term.

4.3. PGO: Relative Consensus on Nonlinear Spaces

To solve the PGO problem in Equation (1), we need to linearize the problem first. We define small increments and in Lie algebra with Jacobians . We denote the Lie group increment operator as ⊕ and the adjoint matrix of the Lie group pose as . Then, after applying and , in Equation (1) can be expressed as

After applying the Campbell–Baker–Hausdorff formula, as discussed at (A.20)–(A.27) in [2], we obtain the Jacobians and , as follows:

where is the right Jacobian operator.

Then, the overall Jacobian for takes the form , where appears at the i-th block-wise column, at the j-th and elsewhere. By stacking all , we obtain the overall Jacobian matrix as , where d is the dimension of the Lie algebra. This is also a widely developed result; refer to [1,2] for more details. Finally, we calculate the gradient of linearized and obtain

which is an iterative form of the Gauss–Newton step. One may easily verify that is a block-wise Laplacian matrix using the results given by Equation (11). This result extends the findings of Placed et al. [22]: the Hessian not only shares structural similarities with the Laplacian but also exactly takes the form of the Laplacian.

In summary, the consistency between Equations (9) and (12) confirms that each iterative update also corresponds to a relative consensus problem on the tangent plane. In other words, the error residuals in the PGO propagate in each iteration in a manner that is identical to the heat diffusion across the pose graph, no matter how gradient vector varies. This result holds true as long as the Jacobians satisfy , as shown in Equation (11), which will yield a Hessian with Laplacian properties.

5. Pose-Graph Topological Integrity

We introduce the PGTI to assess how accurately a pose graph reflects the spatial topology of the environment. A pose graph’s structure defines the routes along which estimation errors propagate; if the graph is a good topological proxy for the environment, these propagation patterns should agree with the actual connectivity of the explored free-space. PGTI, thus, quantifies the mismatch between the error propagation behaviors of the two. It comprises two parts: a per-vertex inconsistency score vector ; an overall integrity metric , defined as the largest entry of . This section presents the formal definitions and computation of . The notations used in HKS and PGTI representations are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Notation for heat kernel signatures (HKSs) and the PGTI metric.

5.1. Construction of Support Graphs

To represent the actual explored space, we introduce two support graphs: the free-space graph and the merged graph . The illustrations of the support graphs are shown in Figure 1.

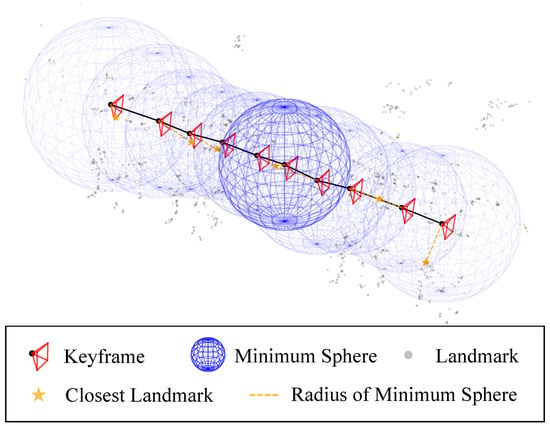

Free-Space Graph: To approximate the explored space topology, we first introduce a free-space graph . Given an unweighted pose graph , we define . A minimum sphere is defined for each vertex as centering at and with radius

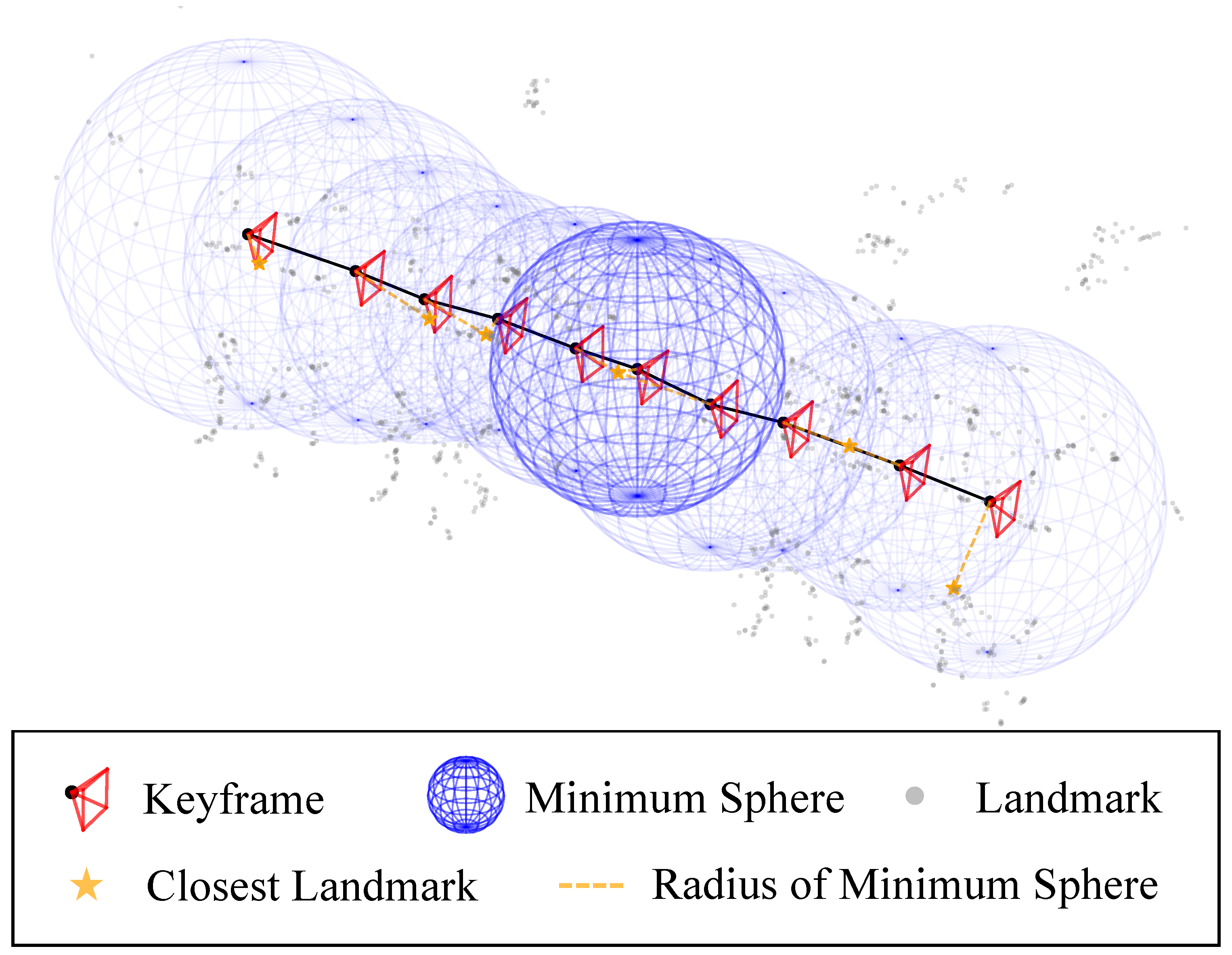

which makes it a minimal guaranteed approximation of the vertex-wise free-space. Figure 2 shows the concept of the minimum spheres. The edges in are determined based on free-space connectivity, which means an edge is added to if the spheres centered at and intersect.

Figure 2.

Concept of the minimum sphere: In maps generated by pose-graph-based SLAM systems, the sphere is defined as the smallest sphere that encapsulates the keyframe center, whose radius is determined by the closest distances to its neighboring landmarks.

Merged Graph: The original is usually much denser than and contains many small pseudo loops, which is caused by the heuristic generation of and makes a one-to-one topological comparison between and almost impossible. Thus, the merged graph is introduced to combine the underlying trajectory topology and fix local disconnections. It is defined as

Finally, we suggest the use of as our final map topology representation.

Topological Motivation: according to the persistent homology theory in Topological Data Analysis [43], global connectivity is recovered by growing -balls around samples and joining any pair whose balls overlap, forming a Čech/Vietoris–Rips complex. Because equals the distance to the nearest obstacle, each ball is the largest region that is guaranteed obstacle-free, which provides physical meanings for the -balls. Edges are, therefore, added exactly at the first topologically valid scale, giving the minimum local approximation of free-space without over-connecting wide open areas.

Alternative methods for generating support graphs may involve using convex voxel clusters [8] or topological graphs [44]. However, these methods construct graphs by introducing new vertices, which complicates direct comparison with the original graph. Moreover, since they require additional processing and system-specific parameter tuning, our approach of using minimum spheres is considered more convenient as it avoids such dependencies. As a result, our approach is simple, general, and can be applied in an arbitrary system that is composed by pose graph and landmarks.

5.2. Inconsistency Score Vector

Unlike traditional optimality criteria such as E-opt, which provide a single scalar measure of overall uncertainty, PGTI offers a per-vertex topological evaluation of the pose graph. We gather these evaluations to form the score vector :

The topological difference at each vertex is computed based on the comparison of the HKS descriptors of in and . Let and be the Laplacian matrices of and , respectively. Their eigen decompositions are

The scaled HKS descriptors for vertex were computed using Equation (3). We denote the scaled HKS for as and for as . We selected the time grid as and , where is the second-smallest eigenvalue, and is the largest one. Finally, we define the relative topological feature distortion by normalizing the HKS difference:

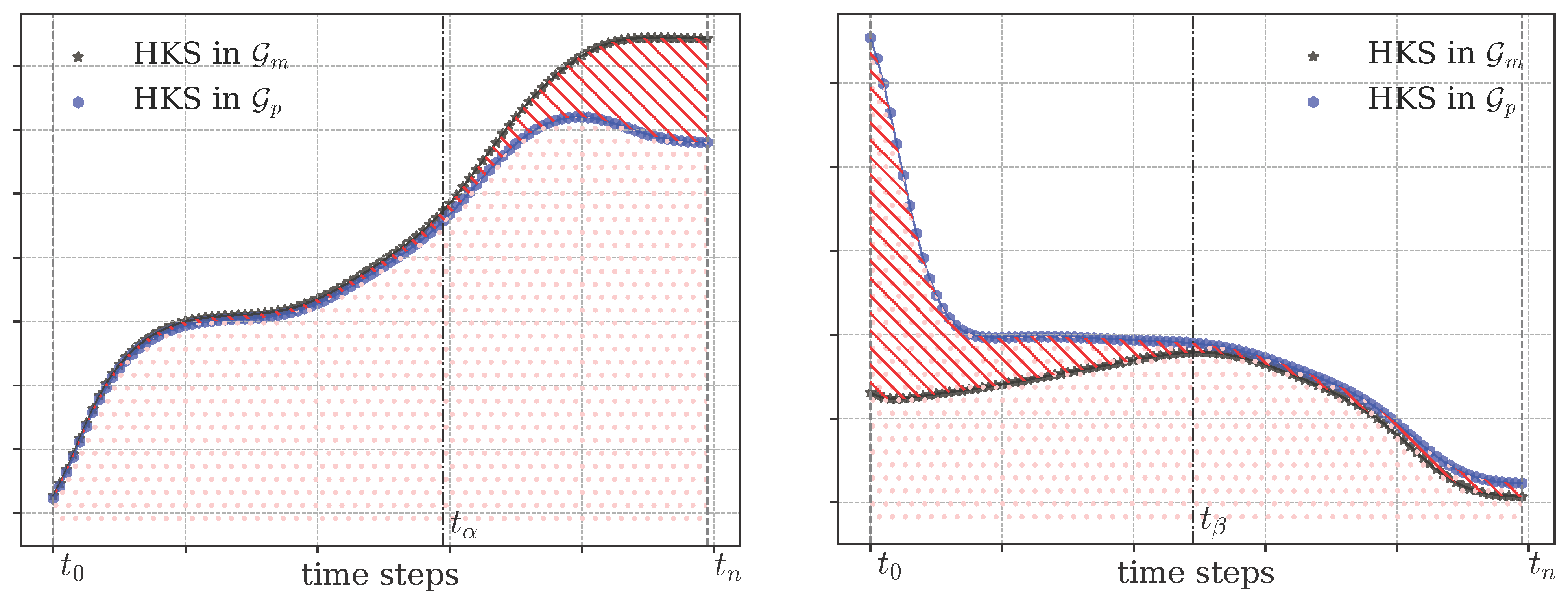

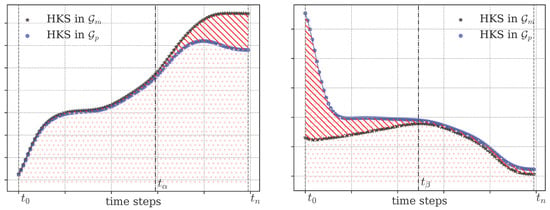

where p is usually set as 1 or 2. Figure 3 displays two typical pairs of HKS in and . When the norm is applied in Equation (17), the resulting measure corresponds to the ratio of the red-slashed area to the pink-dotted area highlighted in Figure 3. A larger value indicates larger relative behavioral change in error propagation between the graph and space, suggesting larger inconsistencies at .

Figure 3.

Visualization of the scaled HKS. The pink-dotted area indicates the overall HKS magnitude in , while the red-slashed area represents the difference between the two signatures. (Left) The two signatures diverge over the interval , indicating that the vertices differ at a relatively large scale. (Right) The two signatures mainly differ over the interval , indicating that the vertices exhibit local topological differences.

From the diffusion viewpoint in Section 4, the scaled HKS at a vertex describes how a unit perturbation injected at that vertex would spread across the graph over time. Consequently, the numerator of Equation (17) measures the change in this diffusion behavior when moving from the pose graph to the merged support graph , while the denominator provides normalization with respect to the original pose-graph diffusion. Each score , therefore, has a clear physical meaning: it quantifies the relative distortion of error (or heat) propagation at vertex induced by inconsistencies between the pose-graph topology and the free-space topology.

5.3. Overall Integrity Metric

The PGTI also provides a general measure that evaluates the difference between the graph and the actual space. The integrity metric, denoted as , is defined as

We take the maximum , not the mean, to select the worst location. Averaging would blur this worst-case information and artificially lower the score as the map grows. This metric can be interpreted, as at least one vertex in the pose graph suffers from a topological inconsistency, which can be quantified and measured through .

5.4. Discussion on Motivation

In fact, consensus on a pose graph reveals the following two views:

- Least square view: Solving the normal equation gives an incremental pose update that minimizes the linearized PGO objective at each step.

- Heat diffusion view: Integrating in a time parameter t yields the same solution at , which exposes topology through HKS. Moreover, applying steady-state condition to the diffusion equation with external force exactly yields , which again confirms the equivalence.

The proposed PGTI metric leverages this second view, not to exactly solve the PGO but to analyze and probe the graph. Evaluating the HKS is equivalent to examining how errors are transmitted throughout the graph. Though the term in Equation (12) varies in each iteration, how the error is propagated remains unchanged.

To be more specific, according to the second view, the Laplacian is not just a matrix parameter in the normal equations, but the generator of a diffusion process, which means that perturbations injected at one vertex spread along the edges like heat. This observation is the main motivation for building PGTI based on heat diffusion. By characterizing how such perturbations propagate across time and space via HKS, we can directly determine whether “error” would diffuse in the same way on the pose graph and on the merged graph. Topological inconsistencies then correspond to locations where these diffusion patterns disagree. This yields a physically interpretable and multi-scale notion of map integrity that goes beyond scalar optimality indices based on individual eigenvalues of the Laplacian.

In this sense, PGTI can be interpreted as a normalized measure of how much the underlying graph topology alters the steady-state diffusion of estimation errors: large values indicate vertices where the error/heat propagation pattern on the pose graph deviates strongly from that on the free-space support graph.

6. Experimental Results

We evaluate the effectiveness of PGTI through a series of experiments. The key advantages of PGTI are its interpretability and multi-scale capability which can help locate topological inconsistency and identify the corresponding types. In this section, we compare PGTI with the optimality criteria and discuss its multi-scale performance by providing case studies across multiple real-world datasets. Additionally, time complexity is also covered.

6.1. Experimental Setting

We conducted experiments on 3D pose graphs with landmarks generated on various scenes in the datasets, including KITTI Odometry Dataset [45] (3D, outdoor urban driving); Campus Dataset (3D, self-collected panoramic data). Keyframes and landmarks were extracted with a SLAM pipeline to form the initial pose-graph structures. Then, we construct the merged graph using free-space connectivity, as introduced in Section 5. All experiments were conducted on a machine equipped with an Apple M4 Pro 14-core CPU. We provide the codes and scripts to reproduce the results here (https://github.com/shxxie/PGTI, accessed on 13 December 2025.).

Unless otherwise stated, all experiments used the same set of parameters. The construction of the support graph and merged graph strictly follows the definitions in Section 5.1 and does not introduce additional thresholds. For the HKS, we follow the standard construction and use 100 logarithmically spaced time steps between

where and are the second-smallest and largest eigenvalues of the corresponding Laplacian (Section 5.2). We use the norm by setting in Equation (17). All other steps of PGTI are, therefore, parameter-free and fully determined by the input pose graph, the landmarks, and the chosen HKS time grid.

6.2. Comparison Between Metrics

Since PGTI measures differences between two graphs, it cannot be directly compared to the standard optimality criteria. To enable a qualitative comparison, we compute the four optimality criteria for both and following the method in [22]. The difference for each criterion, such as , is defined as , where and are the E-opt values of and , respectively. Similarly, we calculate , , and . We also report the average of , denoted as , to show the necessity of taking the maximum value of HKS differences.

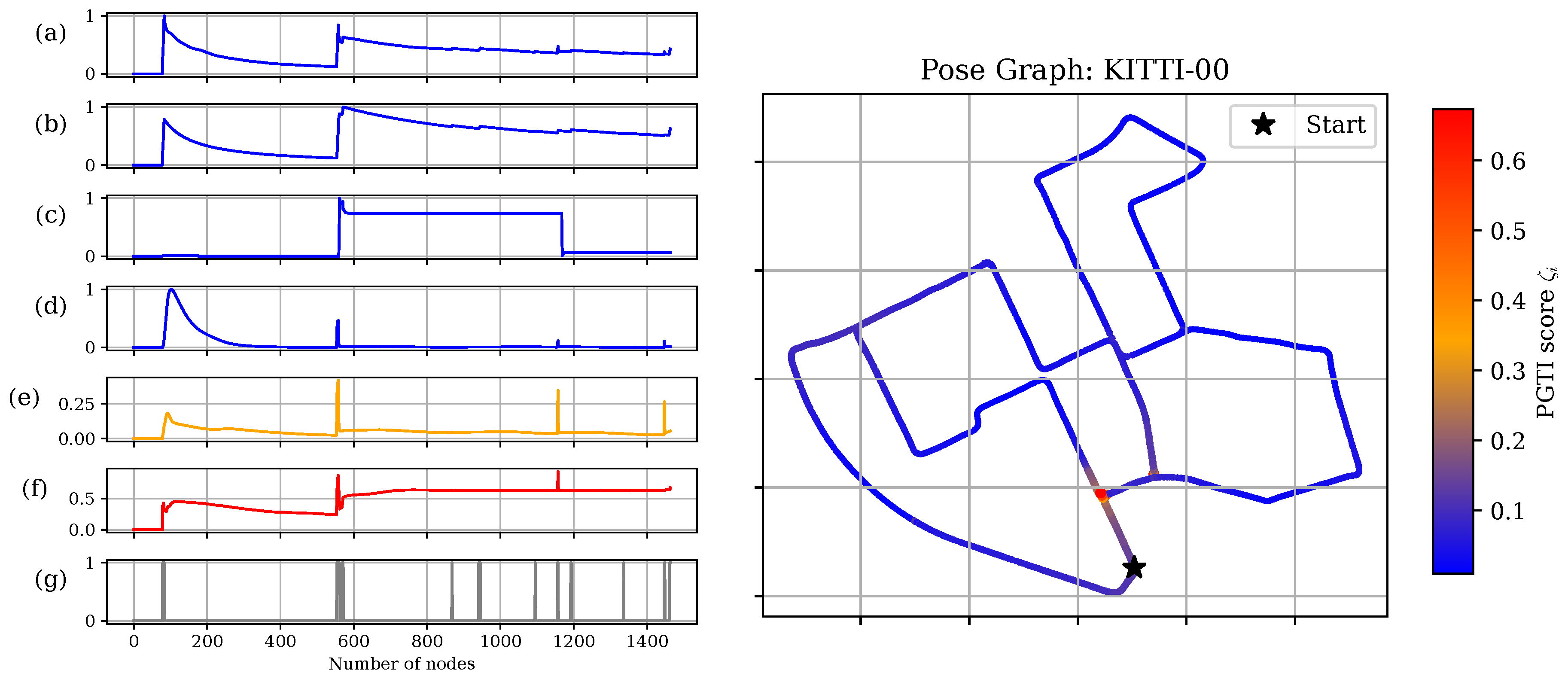

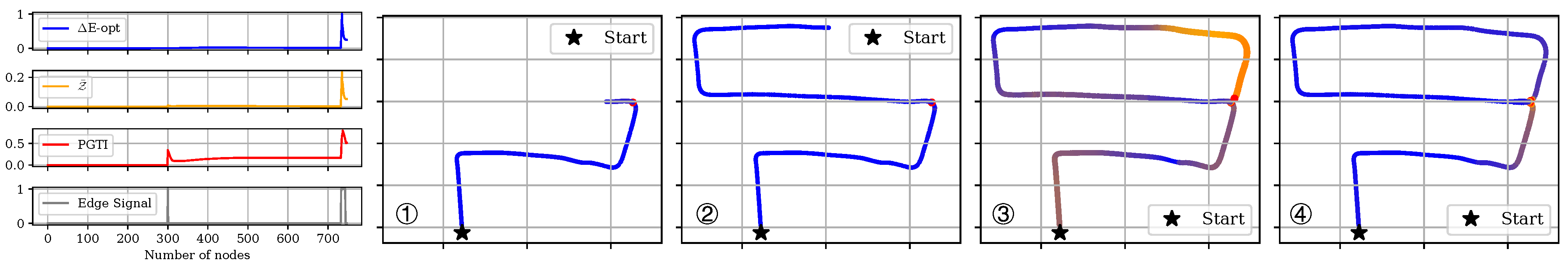

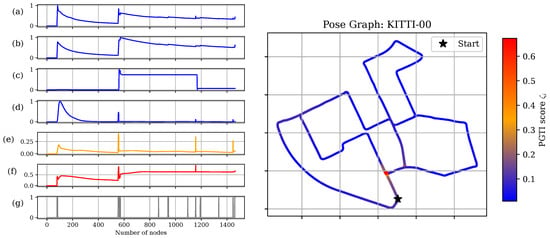

Comparing with Optimality Criteria: Figure 4 illustrates how each metric behaves on a representative KITTI-00 pose graph. In Figure 4, each curve is normalized and plotted against the keyframe index. We follow the standard plotting style used in previous work [22] using graph-based optimality criteria. The horizontal axis corresponds to the keyframe index, i.e., the current number of nodes , so movement to the right can be interpreted as discrete “time” as new frames are inserted into the pose graph. For each metric (e.g., or ), the curve shows the value recomputed on the current graph at that step. The edge-insertion signal is a binary indicator that is 1 at keyframes where at least one new edge is added to the support graph (and 0 otherwise), and we plot it to indicate at which vertices the topology of changes. Cross-correlation analysis between each metric and the edge-insertion signal reveals that, except for , all metrics respond immediately and track the insertion of edges into without any delay. However, merely reflecting change is insufficient; our focus and main interests lie in the interpretability of these changes. Table 3 provides a summary of the interpretations of each metric. Among the candidates, only the proposed is explicitly linked to graph topology, while the others only have vague or implicit connections. The optimality criteria also lack both capability for multi-scale analysis and locating vertices with error, which are exactly the strengths provided by our method.

Figure 4.

Comparison between different metrics in KITTI-00 case. (a) ; (b) ; (c) ; (d) ; (e) ; (f) PGTI ; and (g) the edge-insertion indicator. Vertices are colored using score vector . Brighter colors indicate larger values. (a–d) were normalized before plotting, while (e,f) were already normalized in Equation (17). The horizontal axis shows the keyframe index, and the vertical axis shows the normalized metric value. The edge-insertion signal indicates keyframes at which new edges are added to the support graph.

Table 3.

Qualitative characteristics of metrics. Here, ✓ indicates the presence of the feature, while ✗ indicates its absence.

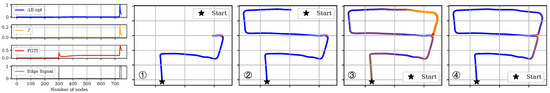

Comparing with Mean Value Option : We use the maximum value in to capture the worst case in the graph. Figure 5 provides a detailed comparison between the average metric and the proposed metric . yields a significantly smaller value during the interval between the first and second edge insertions (the period between ① and ③ in Figure 5), showing how averaging can blur the problem. The inconsistency, which is highlighted in red at ②, has not vanished; it is simply covered by the averaging process. A similar phenomenon occurs in Figure 4. Therefore, by tracking the maximum inconsistency, provides a more accurate indication of the map’s topological health.

Figure 5.

Visualization of normalized , , and in KITTI-05 case, together with several typical scenes during the tracking. ①: keyframe id 325, shortly after the first peak in edge-insertion signal; ②: keyframe id 600; ③: keyframe id 734, the starting keyframe of the second peak; ④: keyframe id 748, the last keyframe. Here, again, the horizontal axis corresponds to the keyframe index, and the curves show the evolution of each metric over graph growth, with the edge-insertion signal marking when new support-graph edges appear.

Global-to-Local Adaptability: The multi-scale nature of the HKS, as described in [10], enables PGTI to capture both local and global structural variations in the graph. Figure 3 illustrates how this multi-scale property is interpreted in practice. By adjusting the parameters in Equation (3), one can seamlessly analyze the graph at different scales. In contrast, conventional optimality criteria lack multi-scale capability, as they are typically defined using a single eigenvalue. Although the second Laplacian eigenvalue is theoretically related to the graph diameter, its upper and lower bounds are too loose to be useful in practice [46]. As a result, conventional criteria cannot adapt to scale varying tasks.

Vertex-Level Analysis: Because the score vector records the topological difference for every vertex , PGTI supports vertex-level diagnosis. Visualizations such as Figure 4 and Figure 5 are examples of this property, where the suspicious vertices are colored in brighter colors. By exploiting the entire graph spectrum, PGTI offers a fine-grained analysis that optimality criteria cannot achieve. This vertex perspective enables us to locate and classify the specific types of inconsistencies associated with individual vertices.

6.3. Case Studies About Inconsistency Classification

In this section, we show a practical use case of PGTI: an automatic diagnosis of the scale of topological inconsistencies in real-world pose graphs. Leveraging the multi-scale nature and vertex-level capability, PGTI distinguishes local and harmless defects (e.g., incomplete loop fusion) from global and serious failures (e.g., perceptual aliasing).

6.3.1. Time-Cut Inconsistency Test

inherits the multi-scale property of the HKS: early diffusion times encode local neighborhood geometry, whereas later times reflect global structures. To show the different scales, we partition the time grid of Equation (3) at a ratio and define

For the worst-case vertex indicated by , we compute and using Equation (17), respectively. Then, we collect the corresponding and using Equation (18). Since the optimal may vary by scene, we instead sweep over a set of values and observe the magnitudes of local and global partitions. This -split test verifies robustness to the split choice and highlights the scale (local vs. global) and the severity of each detected inconsistency.

6.3.2. Results Interpretation

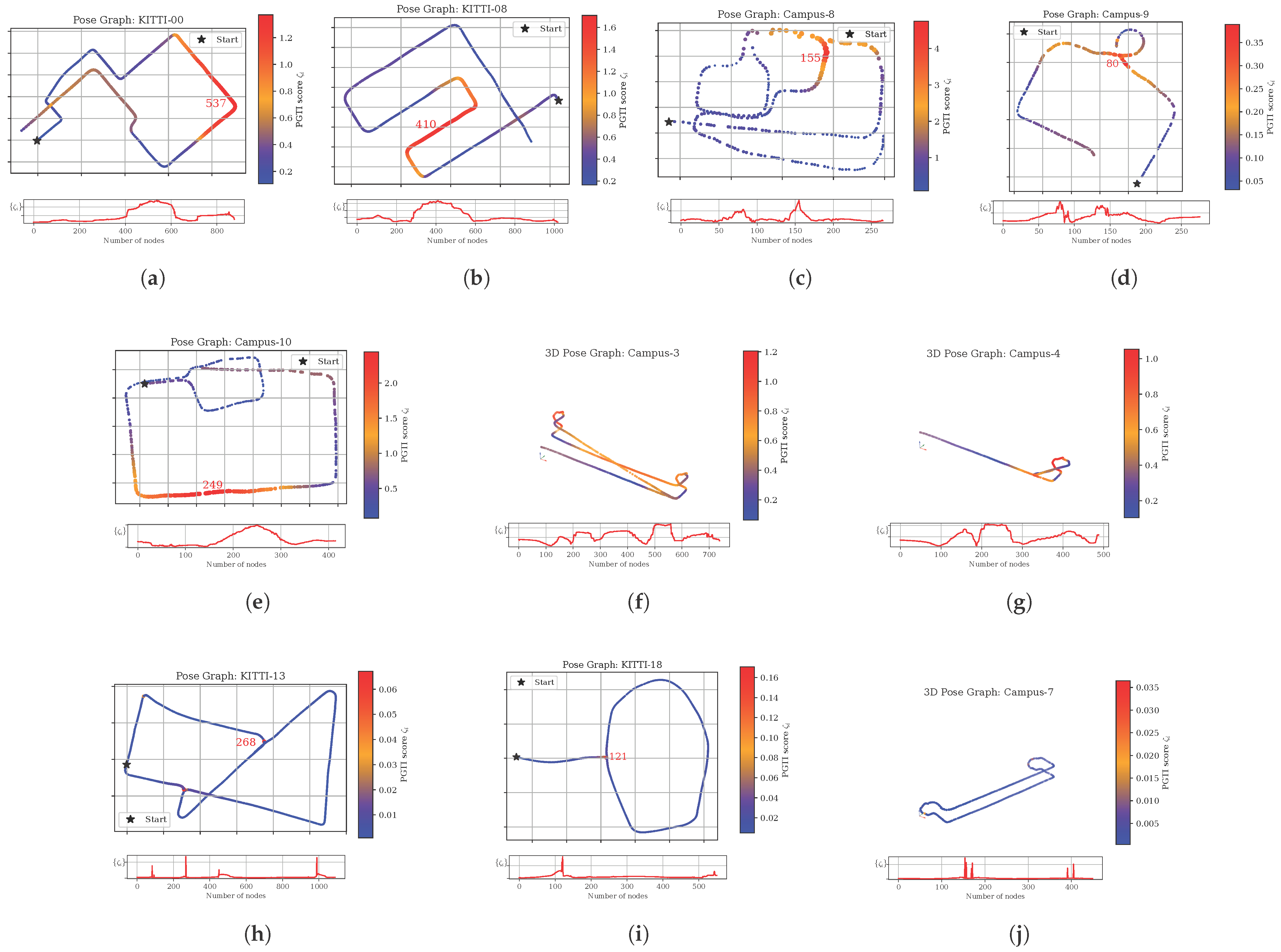

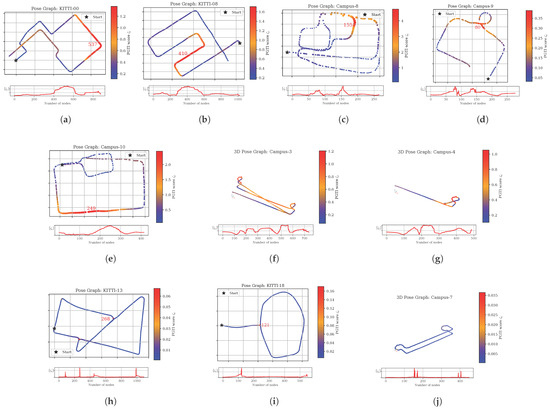

Table 4 and Figure 6 provide detailed results of the -split test on multiple real-world pose graphs and the corresponding visualizations. In Table 4, each row corresponds to one sequence and reports the overall integrity score together with its local and global components, and , obtained from the -split of the HKS time grid. Large values of indicate severe inconsistencies between the pose-graph topology and the free-space topology, while small values correspond to essentially benign defects. The relative magnitudes of and show whether each inconsistency is mainly local (affecting a small neighborhood) or global (affecting the structure of the entire map). Figure 6 visualizes the corresponding pose graphs, with vertices colored by per-vertex scores so that the numerical values in Table 4 can be directly related to visible structural problems such as self-intersections, missed loops, or false loops.

Table 4.

Results of separated PGTI and at different HKS time-cut parameter . Red numbers correspond to larger global inconsistencies, while blue numbers correspond to larger local inconsistencies.

Figure 6.

Visualization of real-world pose graphs with vertices colored by per-vertex PGTI scores . Brighter colors indicate larger values. Each subfigure (a–j) corresponds to one of the real-world examples listed in rows (a–j) of corresponding maps shown in Table 4. Trajectory self-intersections caused by scale drift (KITTI-00, KITTI-08); intersections from missed loop closures (Campus-8, Campus-9, Campus-10); perceptual aliasing in repetitive environments (Campus-3, Campus-4); and minor, essentially harmless inconsistencies (KITTI-13, KITTI-18, Campus-7).

By inspecting the magnitude, we can distinguish harmful from benign inconsistencies. High values correspond to severe structural errors (Figure 6a–g), whereas low values indicate minor, essentially harmless inconsistencies (Figure 6h–j).

Large errors: These errors arise typically when trajectory segments are spatially close yet topologically far in the pose graph; that is, the trajectory intersects itself without connecting edges to represent the topological link, which we summarize as trajectory collisions. This situation often occurs from accumulated scale drift during tracking (Figure 6a,b) or missed loop closures (Figure 6c–e). Moreover, false loops caused by perceptual aliasing are also an important cause for the self-intersection of the explored space (Figure 6f,g). One may refer to the Supplementary Video S1 for detailed visualizations of some additional examples. As a result, metric values are high, meaning the current pose graph is not a good proxy of the true spatial structure.

The -split analysis further shows that the global component dominates the local one. Vertex 537 in Figure 6a is a typical example, where the local neighborhood remains intact, but edges inserted elsewhere have greatly altered the vertex’s relative position in the whole map. This insight enables simple heuristics for automatic detection of perceptual aliasing problems. For example, a large global value increase triggered immediately after a loop-closure attempt is a strong indication that the loop closure match is spurious. However, for cases that do not introduce free-space overlap, PGTI can hardly help, which we conclude as a limitation.

Harmless inconsistency: We also observe inconsistencies with low-magnitude , whose causes include incomplete loop fusion (Figure 6h,i) and missing edges during tracking (Figure 6j). Because pose-graph construction relies on heuristics such as covisibility, it cannot guarantee that all spatially close keyframes are linked. In practice, these cases often appear as small impulses in vector and are generally benign and only have a minor effect on the map’s overall structure.

6.3.3. Discussion on Experiment Results

Whether an inconsistency is local or global is relative to the overall size of the map. In the Campus-9 case (Figure 6d), the overall score is moderate, and and are nearly equal, indicating comparable local and global inconsistencies. This is because the erroneous part affects only a small segment of the trajectory and occupies a limited portion of the map. Thus, its impact is blurred by the surrounding healthy structure. It follows that, as the map continues to grow, such inconsistencies will become even increasingly local relatively, since the selection of in Equation (17) depends on and , both of which change with the map size. This scale dependence is a limitation of the PGTI metric. A future direction is to develop a theoretically grounded normalization scheme that makes the metric totally independent of pose-graph size. Nevertheless, the -split test still allows us to distinguish between different forms of inconsistency.

6.4. Time Complexity

The PGTI calculation is light weighted. We may utilize a KD-tree structure to store the vertex coordinates; the time complexity for creating and is . The most time-consuming step is the eigenvalue decomposition of and , which is also the major computational cost for the optimality methods [22]. Based on our current hardware setup, the average computation time on random graphs with 1000 vertices is approximately 75 [ms]. In practice, focusing on only a subset of eigenvalues rather than the entire spectrum could reduce the computational costs for extremely large maps. Also, testing the necessary subgraphs is also a good choice for shortening calculation time. When combined with multithreading and parallel computation, real-time performance is also possible.

7. Limitations

Here, we summarize the main limitations of the proposed PGTI approach based on the experimental results and discussions above.

First, PGTI is explicitly designed to capture topological inconsistencies, namely mismatches between the connectivity encoded in the pose graph and the connectivity of the explored free space. As discussed in Section 6.3.3, when errors only cause moderate metric distortions that do not induce free-space overlap or change the connectivity, the resulting integrity score can remain small and PGTI may not flag these issues. In this sense, PGTI should be regarded as complementary to traditional metric error measures and covariance-based criteria rather than as a complete replacement.

Second, as discussed in Section 6.4, the time grid for the heat kernel signatures is defined using the eigenvalues and of the merged graph. When the pose graph grows significantly, these eigenvalues change, and a given defect occupies a smaller and smaller relative portion of the global structure. Our Supplementary Video S1 also illustrates this effect with dynamic visualizations. This introduces a scale dependence: the same local inconsistency may yield a smaller value on a much larger map. A more theoretically grounded normalization of the HKS would help make PGTI more size-invariant, which is an important direction for future work.

Third, the current construction of the free-space and merged support graphs relies on the minimum-sphere approximation around keyframes, using the distances to neighboring landmarks as shown in Section 5.1. This approximation is most reliable when the SLAM pipeline provides a reasonably dense and well-distributed set of landmarks. According to our empirical results, in commonly used ORB-feature-based SLAM systems [26,27], the number of landmarks per frame typically exceeds 500, which we consider sufficient to capture the local geometry at a reasonable level of accuracy. On the other hand, in environments that lack texture, the minimum sphere may struggle to approximate the free space, which constitutes another limitation. Nonetheless, with recent advances such as MAST3R-SLAM [47], efficient per-pixel dense reconstruction is now feasible, and an appropriate integration of such dense mapping pipelines might solve this limitation.

Finally, the main computational bottleneck of PGTI is the eigenvalue decomposition of the Laplacians and , as discussed in Section 6.4. As suggested in our discussion, computing only a subset of eigenpairs and selecting subgraphs focused on suspicious regions can be used to accelerate the computation for extremely large graphs (e.g., over 10,000 nodes). Exploring such techniques in the context of online SLAM and large-scale mapping is left for future work.

8. Conclusions

We introduced the PGTI for assessing the pose-graph quality in SLAM systems. Leveraging heat diffusion principles, PGTI provides a robust, efficient, and scalable approach for detecting topological inconsistencies. The experimental results show that the PGTI is capable of quantifying topological errors, which cannot be accomplished by traditional optimality criteria, and performing as a diagnosis guidance.

Future work will be focused on real-time integration and extending PGTI to specific applications. We believe that the PGTI holds great potential for use in applications such as active SLAM and multiagent SLAM. It can guide exploration strategies in active SLAM by identifying areas requiring refinement and improve collaborative mapping in multiagent SLAM by ensuring consistent spatial connectivity. Another promising direction is to combine PGTI with high-accuracy control points (e.g., fixed landmarks obtained from precise offline measurements) when such data are available. This would allow a joint analysis of PGTI and error measures, providing deeper insight into how topological integrity relates to metric trajectory accuracy, scale drift, and random error accumulation. In addition, integrating PGTI into calibration and sensor-fusion pipelines is an interesting avenue for future research, where PGTI could act as a topology-oriented diagnostic signal to ensure that estimated extrinsics and fused trajectories remain consistent with the connectivity of the explored free space.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/robotics14120189/s1, Video S1: pgti.mp4.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.X. and T.O.; methodology, S.X.; software, S.X.; validation, S.X., K.S., and R.I.; formal analysis, S.X.; investigation, S.X.; resources, K.S. and M.O.; data curation, S.X. and R.I.; original draft preparation, S.X.; review and editing, S.X., K.S., R.I., M.O. and T.O.; visualization, S.X.; supervision, T.O. and K.S.; project administration, T.O. and M.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by JSPS KAKENHI, grant numbers JP24K21173 and JP24H00351. This work was also supported by the UTokyo-SMBC Forest GX project.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in repository PGTI at https://github.com/shxxie/PGTI.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kümmerle, R.; Grisetti, G.; Strasdat, H.; Konolige, K.; Burgard, W. g2o: A general framework for graph optimization. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Shanghai, China, 9–13 May 2011; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 3607–3613. [Google Scholar]

- Strasdat, H. Local Accuracy and Global Consistency for Efficient Visual SLAM. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Computing, Imperial College London, London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Arévalo, M.L.; Neira, J.; Castellanos, J.A. On the importance of uncertainty representation in active SLAM. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2018, 34, 829–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, S.; Fitch, R. Active SLAM for mobile robots with area coverage and obstacle avoidance. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatronics 2020, 25, 1182–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, H.; Reid, I.; Castellanos, J.A. On the comparison of uncertainty criteria for active SLAM. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, St. Paul, MN, USA, 14–18 May 2012; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 2080–2087. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, S.; Fitch, R.; Zhao, L.; Yu, H.; Yang, D. On-line 3D active pose-graph SLAM based on key poses using graph topology and sub-maps. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–24 May 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 169–175. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, D.; Tan, P.; Yu, W. Collaborative visual SLAM for multiple agents: A brief survey. Virtual Real. Intell. Hardw. 2019, 1, 461–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blochliger, F.; Fehr, M.; Dymczyk, M.; Schneider, T.; Siegwart, R. Topomap: Topological mapping and navigation based on visual slam maps. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Brisbane, Australia, 21–25 May 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 3818–3825. [Google Scholar]

- Chaplot, D.S.; Salakhutdinov, R.; Gupta, A.; Gupta, S. Neural topological slam for visual navigation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 12875–12884. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Ovsjanikov, M.; Guibas, L. A concise and provably informative multi-scale signature based on heat diffusion. Comput. Graph. Forum 2009, 28, 1383–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasdat, H.; Montiel, J.; Davison, A.J. Scale Drift-Aware Large Scale Monocular SLAM. In Proceedings of the Robotics: Science and Systems, Zaragoza, Spain, 27–30 June 2010; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011; Volume 2, p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Grisetti, G.; Stachniss, C.; Burgard, W. Nonlinear constraint network optimization for efficient map learning. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2009, 10, 428–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlone, L.; Aragues, R.; Castellanos, J.A.; Bona, B. A fast and accurate approximation for planar pose graph optimization. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2014, 33, 965–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, F.; Maire, F.; Sitte, J.; Choset, H.; Tully, S.; Kantor, G. Topological slam using neighbourhood information of places. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, St. Louis, MO, USA, 11–15 October 2009; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 4937–4942. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Y.; Li, J.; Qi, L.; Fan, H. Loop closure detection for visual SLAM using PCANet features. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 24–29 July 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 2274–2281. [Google Scholar]

- Lajoie, P.Y.; Hu, S.; Beltrame, G.; Carlone, L. Modeling perceptual aliasing in slam via discrete–continuous graphical models. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2019, 4, 1232–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Ishikawa, R.; Sakurada, K.; Onishi, M.; Oishi, T. Fast Structural Representation and Structure-aware Loop Closing for Visual SLAM. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Kyoto, Japan, 23–27 October 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 6396–6403. [Google Scholar]

- Eudes, A.; Lhuillier, M. Error propagations for local bundle adjustment. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Miami, FL, USA, 20–25 June 2009; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 2411–2418. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, P.; Zhu, Z.; Sun, S.; Rong, Z.; Zhao, X.; Tan, M. Covariance estimation for pose graph optimization in visual-inertial navigation systems. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2023, 8, 3657–3667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosoussi, K.; Huang, S.; Dissanayake, G. Novel insights into the impact of graph structure on SLAM. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Chicago, IL, USA, 14–18 September 2014; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 2707–2714. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, S.; Zhao, L.; Dissanayake, G. Cramér–Rao bounds and optimal design metrics for pose-graph SLAM. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2021, 37, 627–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Placed, J.A.; Castellanos, J.A. A general relationship between optimality criteria and connectivity indices for active graph-SLAM. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 8, 816–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Placed, J.A.; Rodríguez, J.J.G.; Tardós, J.D.; Castellanos, J.A. Explorb-slam: Active visual slam exploiting the pose-graph topology. In Proceedings of the Iberian Robotics Conference, Zaragoza, Spain, 23–25 November 2022; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 199–210. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, R.; Guo, H.; Yau, W.Y.; Xie, L. Graph-based slam-aware exploration with prior topo-metric information. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 7597–7604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, R.; Yuan, S.; Guo, H.; Yin, P.; Yau, W.Y.; Xie, L. Multi-robot active graph exploration with reduced pose-slam uncertainty via submodular optimization. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 14–18 October 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 10229–10236. [Google Scholar]

- Mur-Artal, R.; Tardós, J.D. ORB-SLAM2: An Open-Source SLAM System for Monocular, Stereo and RGB-D Cameras. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2017, 33, 1255–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, C.; Elvira, R.; Rodríguez, J.J.G.; Montiel, J.M.; Tardós, J.D. Orb-slam3: An accurate open-source library for visual, visual–inertial, and multimap slam. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2021, 37, 1874–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, S.; Dissanayake, G. Anchor selection for SLAM based on graph topology and submodular optimization. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2021, 38, 329–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitanov, A.; Indelman, V. Topological belief space planning for active SLAM with pairwise Gaussian potentials and performance guarantees. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2024, 43, 69–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Martínez, E.A.; Flores-Fuentes, W.; Achakir, F.; Sergiyenko, O.; Murrieta-Rico, F.N. Vision-based navigation and perception for autonomous robots: Sensors, SLAM, control strategies, and cross-domain applications—A review. Eng 2025, 6, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muravyev, K.; Yakovlev, K. Evaluation of topological mapping methods in indoor environments. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 132683–132698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sünderhauf, N.; Protzel, P. Towards a robust back-end for pose graph SLAM. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, St. Paul, MN, USA, 14–18 May 2012; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 1254–1261. [Google Scholar]

- Khosoussi, K.; Giamou, M.; Sukhatme, G.S.; Huang, S.; Dissanayake, G.; How, J.P. Reliable graphs for SLAM. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2019, 38, 260–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallvé, J.; Solà, J.; Andrade-Cetto, J. Graph SLAM sparsification with populated topologies using factor descent optimization. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2018, 3, 1322–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, B.; Giamou, M.; Paull, L.; Agha-mohammadi, A.a.; Leonard, J.; How, J. Information-based active SLAM via topological feature graphs. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 55th Conference on Decision and Control (CDC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 12–14 December 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 5583–5590. [Google Scholar]

- Muravyev, K.; Melekhin, A.; Yudin, D.; Yakovlev, K. PRISM-TopoMap: Online topological mapping with place recognition and scan matching. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2025, 10, 3126–3133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muravyev, K.; Yakovlev, K. NavTopo: Leveraging Topological Maps for Autonomous Navigation of a Mobile Robot. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Interactive Collaborative Robotics, Mexico City, Mexico, 14–18 October 2024; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 144–157. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, W.; Liu, P.; Miao, R.; Gong, Z.; Wen, F.; Ying, R. Navigation system with SLAM-based trajectory topological map and reinforcement learning-based local planner. Adv. Robot. 2021, 35, 939–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Wang, J.; Xu, M.; Zhao, H.; Chen, Z. Topology aware object-level semantic mapping towards more robust loop closure. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2021, 6, 7041–7048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, O.; Kim, N.; Choi, Y.; Yoo, H.; Park, J.; Oh, S. Visual graph memory with unsupervised representation for visual navigation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 15890–15899. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, G.; Li, Y.; Qi, W.; Zhang, K.; Liu, B.; Chen, K.; Li, H.; Ma, J. SLAM-Free Visual Navigation with Hierarchical Vision-Language Perception and Coarse-to-Fine Semantic Topological Planning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.20739. [Google Scholar]

- Sepulchre, R. Consensus on nonlinear spaces. Annu. Rev. Control 2011, 35, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, G. Topology and data. Bull. Am. Math. Soc. 2009, 46, 255–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, W.; Ying, R.; Gong, Z.; Miao, R.; Wen, F.; Liu, P. SLAM based topological mapping and navigation. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/ION Position, Location and Navigation Symposium (PLANS), Portland, Oregon, USA, 20–23 April 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1336–1341. [Google Scholar]

- Geiger, A.; Lenz, P.; Urtasun, R. Are we ready for Autonomous Driving? The KITTI Vision Benchmark Suite. In Proceedings of the Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Providence, RI, USA, 16–21 June 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mohar, B. Eigenvalues, diameter, and mean distance in graphs. Graphs Comb. 1991, 7, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murai, R.; Dexheimer, E.; Davison, A.J. MASt3R-SLAM: Real-time dense SLAM with 3D reconstruction priors. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–21 June 2025; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 16695–16705. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).