Abstract

This paper presents a comparative study on the suitability of free-boundary surface parameterization techniques for generating trajectories on 3D surfaces. The approach maps a 3D surface to a 2D parametric domain through four parameterization methods: Least-Squares Conformal Mapping, Boundary First Flattening, As-Rigid-As-Possible, and Conformal Equivalence of Triangular Meshes. Structured trajectory patterns are generated in the 2D domain and projected back to 3D. We introduce center-to-boundary geodesic deviation measure, which yields a deviation profile over the boundary loop and reflects how well central alignment is preserved under each parameterization method. The results highlight differences in distortion and geodesic preservation, reflecting the suitability of methods for path generation.

1. Introduction

Generating 3D robotic trajectories on complex surfaces is a common requirement in various industrial applications such as spray painting, surface polishing, camera scanning, and depowdering. A robotic trajectory consists of a sequence of via points, each defined by a 3D position and an orientation. One of the main challenges in generating via points lies in dealing directly with the 3D geometry, especially when the surface has high curvature or complex topology. To address this, surface parameterization (also known as UV mapping or flattening) is widely used for path generation. Parameterization maps a 3D surface onto a 2D domain, assigning 2D coordinates to each vertex of the mesh while preserving the connectivity of the triangles. Depending on the algorithm, the parameterization may aim to preserve angles, areas, or local rigidity. Several methods have been proposed for surface parameterization. Lévy et al. [1] introduced the Least Squares Conformal Map (LSCM), which remains the most widely adopted free-boundary parameterization method due to its conformality. Sawhney and Crane [2] proposed Boundary First Flattening (BFF), which emphasizes boundary control to produce near-isometric maps while preserving angles. Liu et al. [3] introduced the As-Rigid-As-Possible (ARAP) free-boundary parameterization, which preserves triangle shapes as rigidly as possible. ARAP balances conformality and rigidity through a parameter : yields the as-similar-as-possible (ASAP) mapping, equivalent to LSCM, while produces the fully rigid ARAP mapping. ARAP does not require mapping the border to a convex polygon and needs only a minimal set of pinned vertices. Springborn et al. [4] presented the Conformal Equivalence of Triangular Meshes (CETM), which computes a conformal map by solving for scale factors that satisfy the discrete conformal equivalence relation, enabling high-quality angle-preserving flattening with rigorous theoretical guarantees. McGovern and Xiao [5] generated a UV grid on a freeform 3D polygon mesh and computed a constrained coverage path with evenly spaced steps. Phan et al. [6] used the LSCM to produce a scanner path with controlled overlap between passes, focusing on minimizing conformal distortion. However, for high-curvature models, uneven area distortion can cause non-uniform point spacing after back-projection, leading to abrupt orientation changes and noise. Weingartshofer et al. [7,8] presented an automated workflow for robotic drawing on complex surfaces. Their approach applied LSCM-based parameterization and two projection methods to transfer user-defined 2D patterns onto 3D objects, followed by trajectory generation. They also investigated motion and hybrid force/motion control to ensure accurate execution with constant contact force, demonstrating applicability to industrial tasks such as painting, cutting, and engraving. Song and Kim [9] developed a robotic pen-drawing system that reproduces digital art on unknown 3D surfaces using a seven-DOF manipulator with impedance control, applying LSCM on RGB-D point clouds for distortion-free mapping of 2D drawings onto uneven geometries.

While parameterization simplifies path planning by allowing trajectory generation in the 2D domain before mapping it back to the 3D surface, the choice of parameterization method remains critical for accurately transferring via points between domains. Each technique imposes different constraints, such as preserving angles, area, or rigidity, which directly influence the uniformity and quality of the resulting trajectories. If the 2D region between the parametric center and a boundary point is locally compressed, the corresponding 3D segment becomes stretched, leading to enlarged spacing between consecutive path points after back-projection. Conversely, when the 2D area is stretched, the mapped 3D segment becomes compressed, yielding denser spacing. Because such distortions vary nonuniformly across the surface depending on local curvature and bumpiness, their overall impact on the generated trajectory is difficult to predict from local metrics alone. In industrial robotic processes such as spray painting, polishing, machining, surface inspection, and robotic drawing, mapping distortion directly affects the accuracy and consistency of generated trajectories. Its influence can be expressed through measurable task-level constraints. For coverage trajectories like spiral or raster, maintaining uniform spacing after back-projection is critical: deviations beyond roughly 15–20% of the nominal step cause overlap or under-coverage between adjacent passes. Excessive stretching or compression can shift the deposited or drawn pattern from its intended position in robotic drawing, while in painting it leads to uneven coating thickness. Similarly, in polishing or machining, it results in irregular material removal, and in scanning or inspection, it alters sampling density and measurement consistency. Evaluating parameterization methods by how well they preserve spacing and distribution over the 3D surface therefore provides a unified and quantitative criterion for assessing their suitability in trajectory generation.

Because the suitability of a parameterization depends on the downstream task, a generalized yet physically interpretable criterion is needed to assess trajectory accuracy. In parameterization-based trajectory generation, paths are typically constructed in the 2D parametric domain with respect to a reference point, often chosen as the pole of inaccessibility, the location farthest from the boundary of the parameterized shape. Ideally, when this farthest point in 2D is mapped back onto the 3D surface, it should coincide with the true geodesic center, i.e., the point farthest from the surface boundary in the 3D domain. A parameterization that preserves this correspondence maintains the relative center-to-boundary relationships of the surface and is therefore more suitable for evenly distributing trajectories around the geometry. To quantitatively evaluate this correspondence, we introduce the center-to-boundary geodesic deviation (CBGD) metric. The CBGD measures how much the back-projected parametric center deviates from its true 3D geodesic location after flattening and re-mapping, effectively capturing the cumulative stretching or compression between the center and boundary that causes global trajectory drift. It thus provides a unified, physically meaningful measure of mapping consistency directly related to spacing preservation and coverage uniformity in generated trajectories. This evaluation is performed on single-patch, genus-zero test meshes. Each model represents a simply connected open surface with a single boundary loop, ensuring that conformal and free-boundary parameterizations can be applied consistently across all objects.

In this work, we compare four different free-boundary parameterization techniques to evaluate their effectiveness for trajectory generation. The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the methodology, including parameterization and back-projection; Section 3 reports and discusses the experimental results; and Section 4 concludes the paper.

2. Methodology

We compare free-boundary parameterization techniques for generating 3D trajectories by first flattening the surface, represented as a triangular mesh, onto a 2D parametric domain using four different methods: LSCM, BFF, ARAP, and CETM. Trajectory patterns are created in the 2D domain, and the via points are then mapped back to the 3D surface through barycentric interpolation. To evaluate symmetry preservation and distortion, we use a center-to-boundary geodesic deviation measure comparing the mesh center with the back-projected 2D center; the resulting profile indicates suitability for path generation.

2.1. Three-Dimensional Surface Parameterization to Two-Dimensional Plane

Consider a 3D manifold triangular mesh model , composed of a set of vertices and a set of triangular faces . The goal of surface parameterization is to define a bijective mapping function

that transforms the 3D mesh into a 2D parametric domain , consisting of a vertex set and triangle set . The parameterization must preserve the mesh connectivity, i.e., Vertices in the parametric domain can be further categorized into boundary vertices and interior vertices , such that: The connectivity among vertices is described by the edge set , inherited from the original mesh topology. The notation and symbols used throughout the paper are shown in the Table 1.

Table 1.

Notation used for the 3D triangular mesh and its 2D parameterized triangular mesh.

2.1.1. Least-Squares Conformal Mapping (LSCM)

The Least-Squares Conformal Mapping (LSCM) method aims to flatten a 3D triangular mesh onto a 2D domain while minimizing angular distortion in a least-squares sense. In complex analysis, a conformal map is defined as a bijection that locally preserves angles. The transformation of a 3D triangulated surface into a 2D domain can be represented as a complex-valued function:

where are coordinates in the local 2D basis of a triangle, and are the real and imaginary parts in the parametric domain. Conformality requires the Cauchy–Riemann equations:

which can be expressed compactly as

Let be a triangle of the mesh, with an orthonormal basis . A point with coordinates inside the triangle can be expressed in barycentric coordinates and the mapping to the parameter domain is:

This defines the interpolation of the coordinates of the triangle’s vertices across its interior using barycentric coordinates. The barycentric coordinates are computed as:

This matrix expression gives the barycentric coordinates of a point relative to the triangle’s vertices, normalized by twice the triangle’s area . The gradient of u over a triangle can then be written as:

is the matrix mapping the vertex u coordinates to their spatial gradient over the triangle. The matrix is given by:

This matrix encodes the edge directions of the triangle in the local 2D basis, scaled by the inverse of twice the area. The discrete Cauchy–Riemann condition becomes:

This enforces the discrete conformality condition for each triangle by ensuring the gradients of u and v remain orthogonal and equally scaled. Since exact conformality is only possible for developable surfaces, LSCM minimizes the following energy in the least-squares sense:

This energy measures the deviation from conformality across the mesh, weighted by triangle areas, and is minimized to compute the LSCM parameterization. The discrete LSCM energy was assembled using the cotangent Laplacian and vector–area matrix , leading to the sparse linear system

which couples the real and imaginary parts of the mapping coordinates. To eliminate the null space of rigid motions, two boundary vertices were fixed to and , constraining translation and rotation while leaving scale free. The system was solved using a direct sparse Cholesky factorization until machine-precision convergence.

2.1.2. Boundary First Flattening (BFF)

The Boundary First Flattening (BFF) algorithm focuses on accurately controlling the shape of the boundary in the 2D parametric domain while maintaining near-isometric mapping of the interior. This is particularly useful for applications where boundary geometry is critical. Let be the input 3D triangular mesh, and the resulting 2D parameterization domain. The set of vertices is divided into:

are boundary vertices and are interior vertices in the 3D mesh. The boundary loop is first extracted and mapped to 2D boundary coordinates .

BFF computes a discrete conformal metric using the Cherrier formula, which relates the change in curvature to the logarithmic scale factors at each vertex:

Here, is the original Gaussian curvature at vertex i, and is the target curvature after flattening. The difference controls the vertex scaling. The boundary scale factors are determined by integrating the geodesic curvature along the boundary:

is the original edge length in , and is the scaled length in . The method uses the Poincaré–Steklov operator to transform boundary length constraints (Dirichlet conditions) into compatible boundary angle constraints (Neumann conditions), due to which the interior harmonic extension matches the boundary shape. The interior vertex coordinates are solved via the Laplace equation:

Thus, u and v coordinates vary harmonically across the mesh. In practice, the BFF algorithm first computes boundary scale factors from curvature constraints, then integrates them to obtain the target boundary shape in 2D, and finally solves the Laplace equation to determine the interior vertex positions. In our implementation, BFF was used in its minimum-distortion configuration, where boundary lengths are prescribed through the logarithmic scale factors rather than by directly fixing curvatures. The Poincaré–Steklov operator was realized by solving discrete Poisson equations on the mesh, which provided the relation between the boundary scale factors and the corresponding curvature variation through the Cherrier relation. The boundary curve in the parameter domain was reconstructed by integrating unit tangents derived from cumulative exterior angles so that the edge lengths matched the prescribed targets. The interior coordinates were obtained by harmonic extension from this boundary curve, and the reconstructed boundaries were visually confirmed to be free of self-intersections.

2.1.3. As-Rigid-As-Possible (ARAP)

The As-Rigid-As-Possible (ARAP) parameterization aims to preserve the local shape of triangles as much as possible during the flattening process. It seeks to minimize distortions by aligning each triangle in the parameter domain with its counterpart in the 3D mesh through locally optimal rigid transformations. Let be a triangle in with vertex positions in 3D and corresponding positions in the parameter domain. For an edge of triangle , we define the edge vectors in 3D and 2D as

Here, denotes the edge from vertex i to vertex j in the original 3D domain , while denotes the corresponding edge in the parameter domain . The ARAP energy is defined over all triangles of the mesh as

where denotes the set of edges of triangle . The coefficients are cotangent weights, defined as

with and being the angles opposite to edge in the two adjacent triangles. is the optimal rotation matrix associated with triangle q, ensuring that the deformation from the original 3D edges to their 2D counterparts is as close as possible to a rigid transformation. In practice, is computed by solving a local Procrustes problem, typically using the singular value decomposition (SVD) of the covariance matrix between the original 3D edges and their 2D mappings. The minimization of is carried out with the standard local/global scheme, which alternates between estimating the optimal rotations for fixed vertex positions and solving a sparse symmetric linear system to update the vertex positions with the rotations held fixed. This iterative process progressively refines the parameterization to achieve a mapping that is as rigid as possible while accommodating the flattening into the 2D domain. Implementation-wise, the ARAP solver employs cotangent edge weights with a unit weighting factor . The initialization is performed using a harmonic map, which serves as the As-Similar-As-Possible (ASAP) starting configuration before switching to the full ARAP energy. Each iteration alternates between local updates, where optimal per-triangle rotations are estimated via stabilized SVD to handle near-degenerate elements, and a global step that updates vertex coordinates by solving a sparse symmetric linear system through a direct Cholesky-based solver. The process is repeated until the displacement of vertices between successive iterations falls below numerical tolerance, ensuring convergence to a stable, locally rigid parameterization.

2.1.4. Conformal Equivalence of Triangular Meshes (CETM)

The Conformal Equivalence of Triangular Meshes (CETM) method, introduced by Springborn et al. [4], finds a parameterization that is conformally equivalent to the original mesh while allowing precise control over target curvature. Let be the logarithmic scale factor assigned to vertex i. The scaled edge lengths are defined as

where is the original length of edge in , and is the conformally scaled length in . The Gaussian curvature at vertex i after scaling is given by

where is the angle at the vertex i in triangle q under the scaled metric. CETM solves for u such that

where is the prescribed target curvature. The choice of satisfies the discrete Gauss–Bonnet condition, ensuring that the sum of curvatures matches that of a flat embedding, and the sum of curvatures is considered to be for boundaries. The problem is formulated as a convex optimization via the energy

where is a convex function of the scaled angles of triangle q, derived from the Lobachevsky function. The second term enforces the target curvature constraints. Once the optimal u is obtained, the scaled edge lengths are recovered, and the 2D layout of vertices is computed using a boundary embedding followed by harmonic extension to the interior. In practice, interior vertices use and boundary vertices , ensuring consistency with the discrete Gauss–Bonnet theorem. The energy is minimized using Newton’s method with analytic gradient and a Hessian assembled from cotangent weights of the current image triangles. Angles close to 0 or are clamped to stabilize the Hessian near degenerate configurations. After convergence, the 2D layout is reconstructed from the optimized edge lengths and angles, enforcing triangle inequalities to avoid local flips.

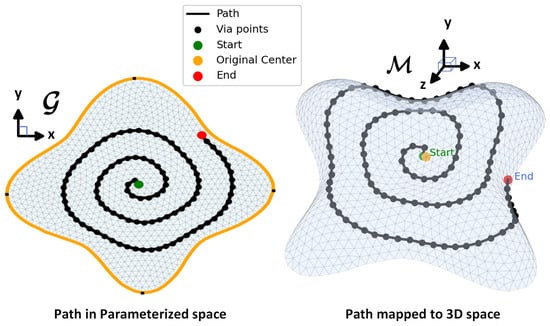

2.2. Three-Dimensional Path Generation

Once the surface is parameterized, a desired path is defined in the 2D domain. In this work, we chose a contour-parallel spiral path starting from the central point and expanding toward the boundary as shown in Figure 1. The generated path consisted of three spiral turns with a total length of 318.34 units and a step size of 3.2, with the center at (49.4, 49.4). The objective was not to emphasize the path design itself but to evaluate how different parameterization methods influenced the accuracy of transferring this path back onto the 3D surface. The 2D path consisted of a set of via points in , and each 2D waypoint was mapped to the original mesh through barycentric interpolation. For a given point inside a 2D triangle with vertices , barycentric weights were computed such that

We then found the 3D triangle corresponding to , whose vertices were . We used barycentric weights to find the point inside 3D triangle as follows:

The procedure involved locating the 2D triangle that contained each point , computing its barycentric weights, and applying the same weights to the corresponding vertices of to reconstruct the 3D point. To efficiently identify , a uniform-grid spatial index was built over per-face axis-aligned bounding boxes in , providing near-constant lookup time. Neighboring cells were also queried for points near boundaries to avoid missing candidates. Candidate faces were validated using an orientation-based point-in-triangle test that returned barycentric coordinates. For robustness near edges and vertices, coordinates with values () were accepted, small negatives were clamped to zero, and weights were normalized to sum to one. Points lying exactly on shared edges were resolved deterministically by selecting the triangle with the maximal minimum barycentric weight, ensuring consistent 2D–3D correspondence. Faces with near-zero UV area were excluded, and points failing inclusion were logged and discarded to preserve numerical stability and determinism.

Figure 1.

Path designed in the parameterized domain (ARAP) and mapped onto the 3D surface.

The reconstructed 3D waypoints obtained via barycentric interpolation in Equation (22) can be directly converted into robot-executable poses, which define both the Cartesian position and orientation of the end-effector. For each waypoint , the unit normal is computed as the normalized average of the facet normals of all triangles incident to . The offset point is then defined to account for the tool distance from the surface:

The Cartesian pose of the end-effector is expressed as

where is the quaternion representation of the rotation matrix , which aligns the tool z-axis with while maintaining tangential consistency with the trajectory direction. In practice, this tangential consistency is achieved through a projection-based formulation:

These poses can then be passed to motion-planning frameworks such as PyMoveIt2, which solve the inverse kinematics problem

yielding joint configurations that can be executed on the robot. While the reconstructed waypoints can be directly converted into robot-executable poses, this alone does not ensure that spatial spacing and coverage uniformity are preserved. Even small distortions in the 2D map can accumulate into global drift once the trajectory is back-projected onto the 3D surface.

To quantify how each parameterization affects these center–boundary relationships, we introduce the center-to-boundary geodesic deviation (CBGD). This metric measures the displacement of the back-projected parametric center from its true geodesic position on , capturing the cumulative stretching or compression between the surface center and its boundary. Lower CBGD values indicate better mapping consistency and more reliable spacing for coverage-oriented trajectories. The boundary of the mesh is represented by the ordered set of vertices . Let denote the true center of , defined as the vertex with the maximum geodesic distance from , and let be the mapped center obtained from the parametric domain. For each boundary vertex , let denote the geodesic distance between a point P and on . The relative center-to-boundary geodesic deviation at is then given by

and the set defines the geodesic deviation profile along the boundary loop.

3. Results and Discussion

All experiments were implemented in Python 3.8.10 and carried out on a system running Windows 11, a 13th-generation Intel i9 processor, and 32 GB of RAM. We evaluated eight triangular meshes—Wash basin (10,902 faces, 5589 vertices), Turtle (7600 faces, 3954 vertices), Face mask (11,168 faces, 5735 vertices), Bumpcap (15,082 faces, 7641 vertices), Kitten face (31,954 faces, 16,195 vertices), Lilium top (1844 faces, 975 vertices), Four-sided star (5344 faces, 2801 vertices), and Car body (12,763 faces, 6517 vertices). Before parameterization, each input mesh was cleaned to eliminate geometric defects that could affect distortion analysis. The cleaning stage merged duplicate vertices and edges, removed degenerate or unreferenced faces, repaired inconsistent normals, and ensured manifold connectivity. The cleaned meshes were then processed using four parameterization solvers (LSCM, BFF, CETM, and ARAP). Each resulting UV layout was validated by checking (i) the positivity of the outer boundary area and (ii) the ratio of non-zero UV magnitudes. If either condition failed, the mesh was reprocessed and the parameterization repeated for a limited number of attempts. When valid mappings could not be obtained, isotropic explicit remeshing was applied to improve triangle regularity and solver stability, using the meshing_isotropic_explicit_remeshing filter in PyMeshLab configured with ten iterations, a crease angle of , and a target edge length of approximately 1–2% of the mesh bounding-box diagonal. The center-to-boundary geodesic deviation (CBGD) was then computed for all methods as defined in Equation (26). Distortion between the center and boundary in the 2D domain causes the back-projected parametric center to deviate from its true 3D geodesic position, altering the corresponding distances to boundary points in . This deviation reflects potential local over- or undersampling in the trajectory. Ideally, a parameterization preserves these center–boundary relationships, yielding near-symmetric sampling and a geodesic deviation approaching zero.

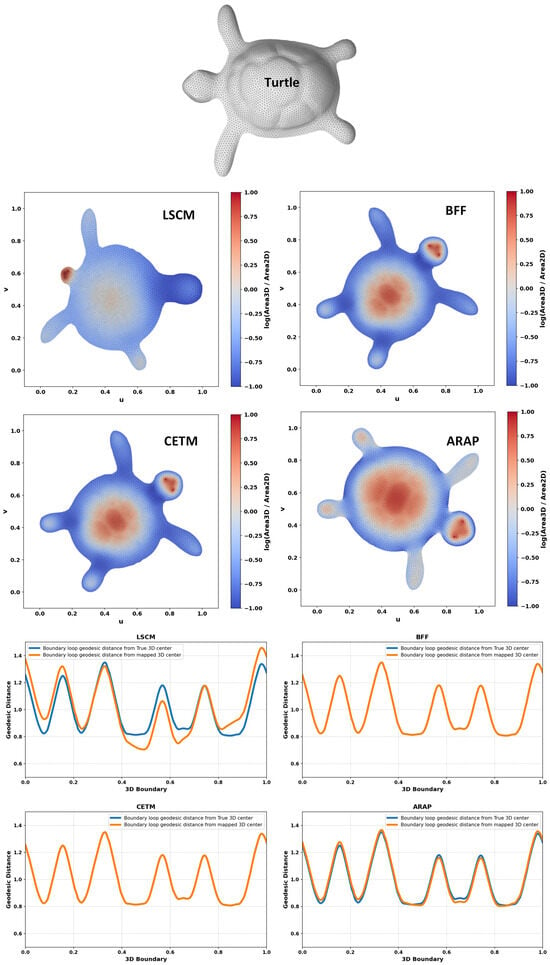

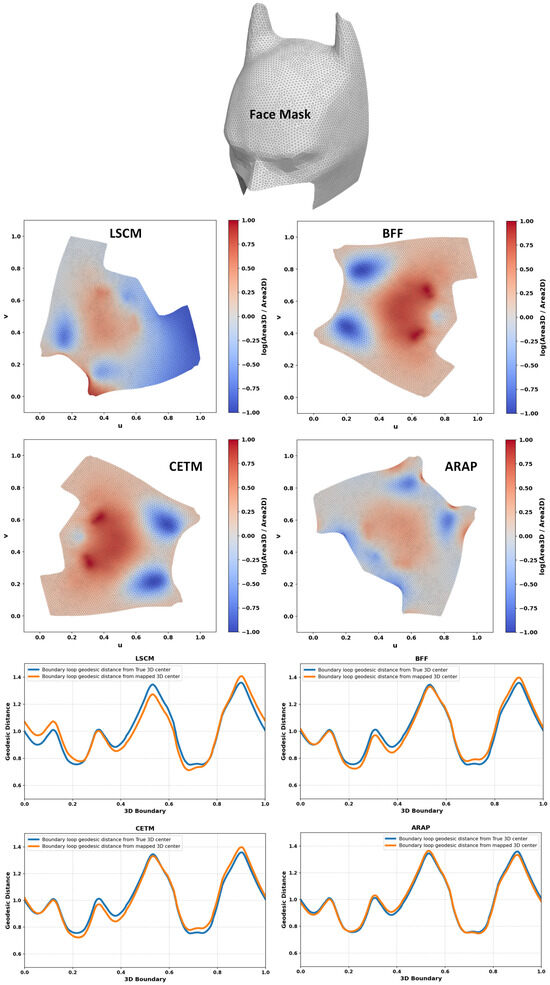

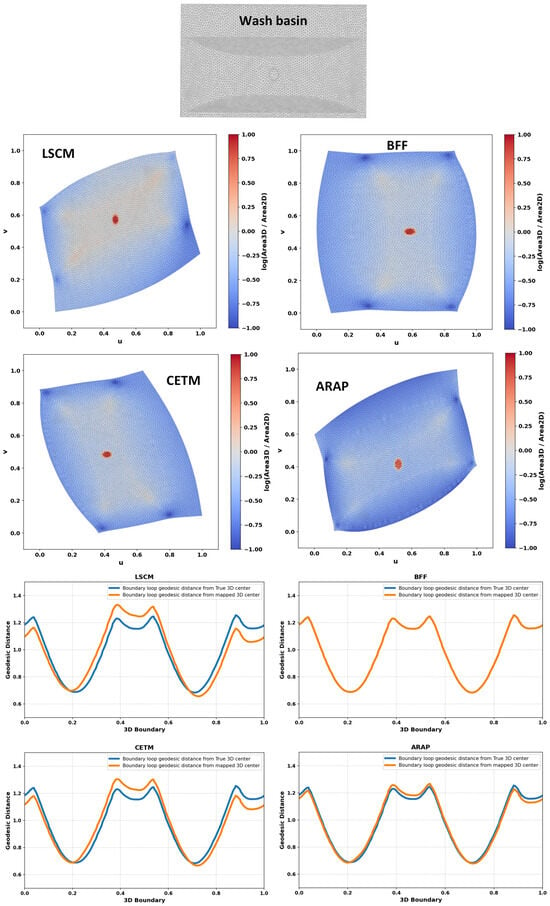

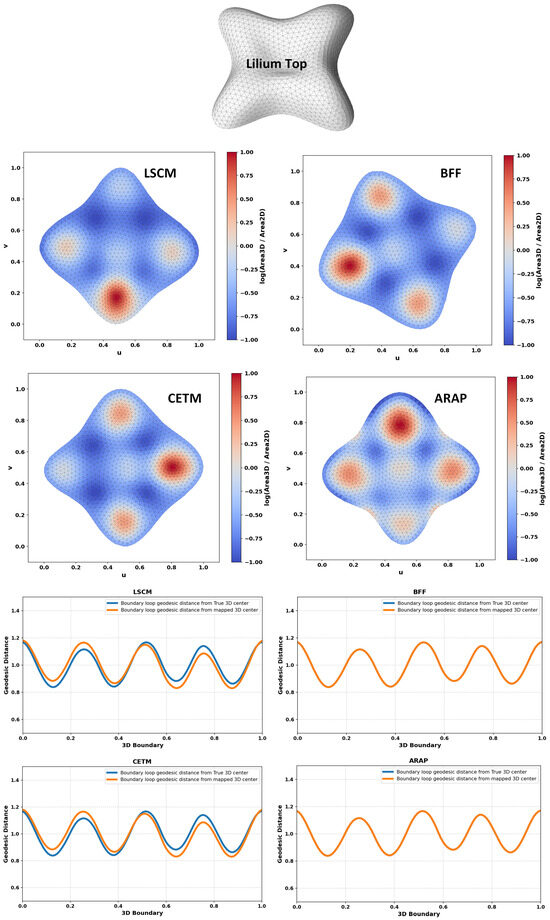

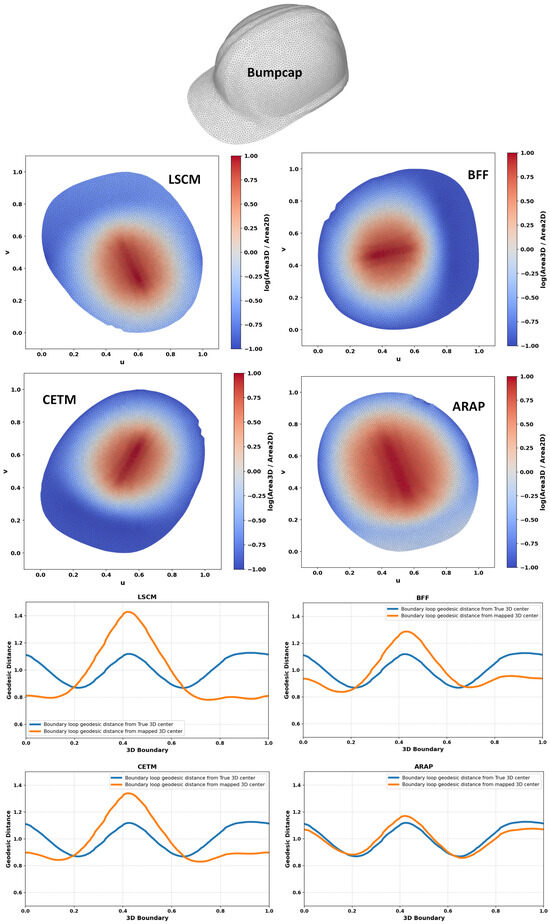

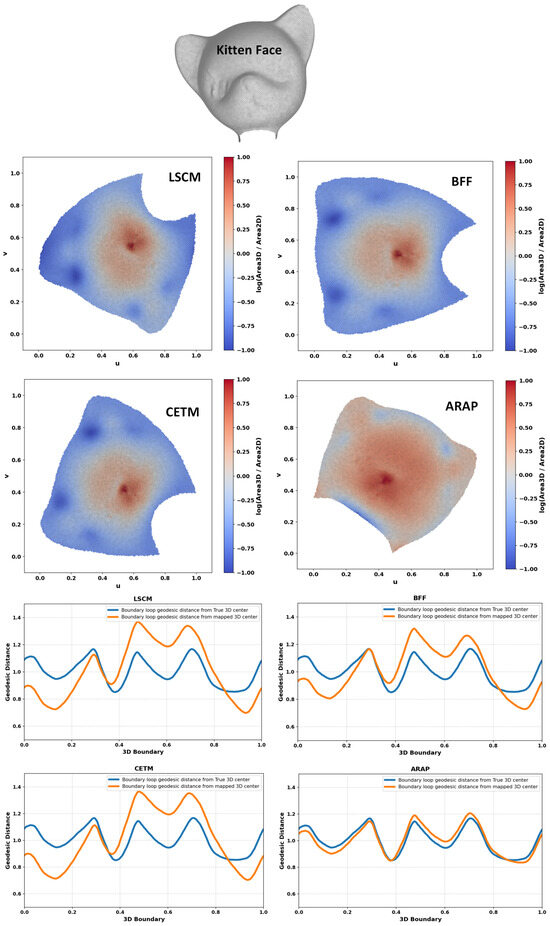

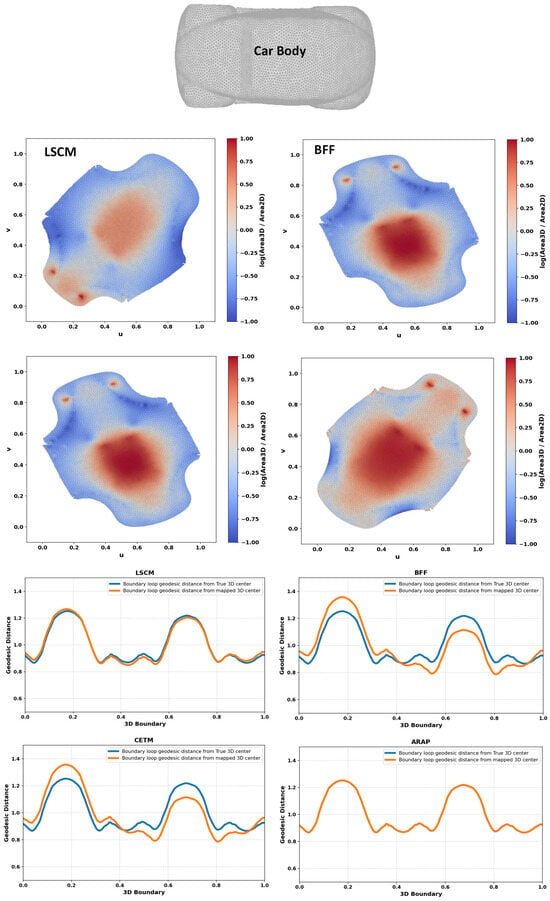

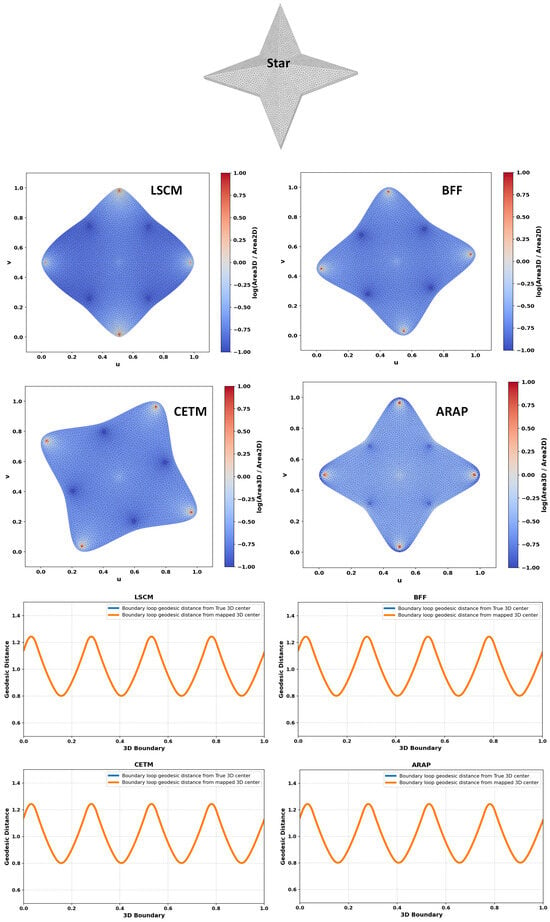

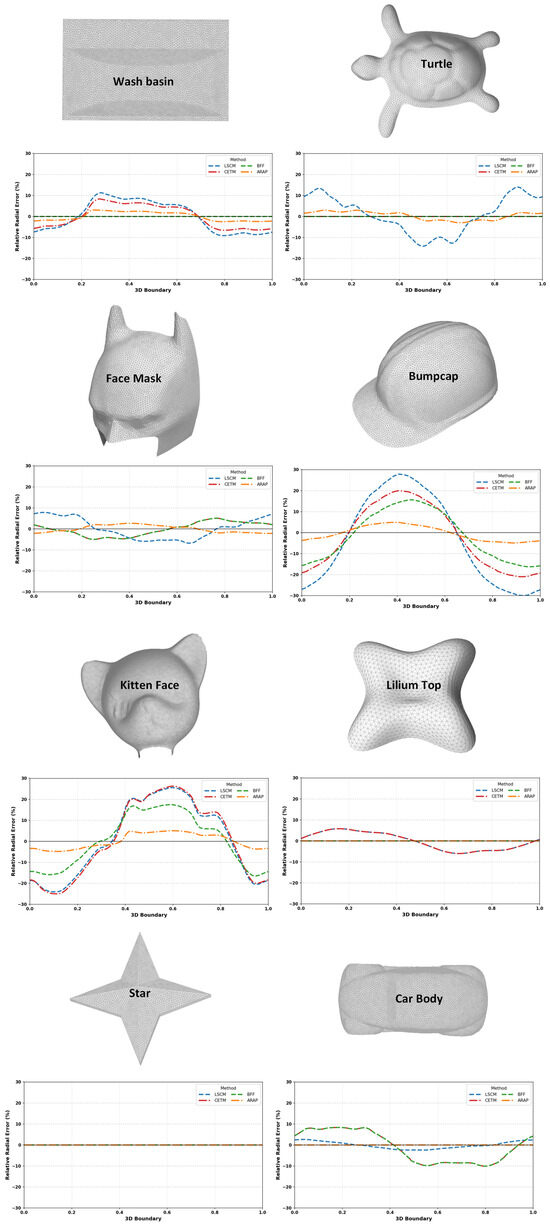

Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9 shows the area distortion produced by the four parameterization methods (ARAP, BFF, CETM, and LSCM) together with the corresponding center-to-boundary geodesic distance deviation for each test object. Figure 10 shows the per-object geodesic deviation curves for all four methods. The error depended on local curvature and geometry. Bumpcap and Kitten face showed the largest, least-uniform errors, with LSCM having the highest peak. Objects with limited curvature variation and minimal bumpiness exhibited mild deviations. On smoother geometries, deviations remained moderate, with ARAP and BFF generally tighter and CETM and LSCM more variable. For Four-sided star, all methods performed almost perfectly, as its creased structure limited stretching/compression and preserved center alignment.

Figure 2.

Area distortion and comparison between geodesic distances from the true center to the boundary and from the mapped center to the boundary for different free-boundary parameterizations.

Figure 3.

Area distortion and comparison between geodesic distances from the true center to the boundary and from the mapped center to the boundary for different free-boundary parameterizations.

Figure 4.

Area distortion and comparison between geodesic distances from the true center to the boundary and from the mapped center to the boundary for different free-boundary parameterizations.

Figure 5.

Area distortion and comparison between geodesic distances from the true center to the boundary and from the mapped center to the boundary for different free-boundary parameterizations.

Figure 6.

Area distortion and comparison between geodesic distances from the true center to the boundary and from the mapped center to the boundary for different free-boundary parameterizations.

Figure 7.

Area distortion and comparison between geodesic distances from the true center to the boundary and from the mapped center to the boundary for different free-boundary parameterizations.

Figure 8.

Area distortion and comparison between geodesic distances from the true center to the boundary and from the mapped center to the boundary for different free-boundary parameterizations.

Figure 9.

Area distortion and comparison between geodesic distances from the true center to the boundary and from the mapped center to the boundary for different free-boundary parameterizations.

Figure 10.

Per-object geodesic deviation profiles for LSCM, BFF, CETM, and ARAP.

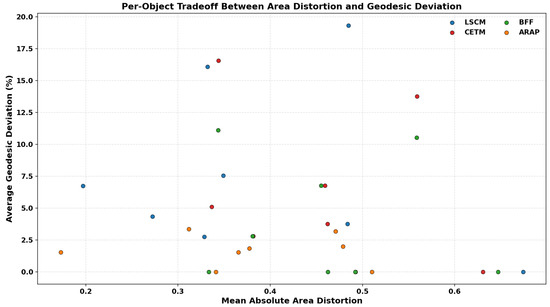

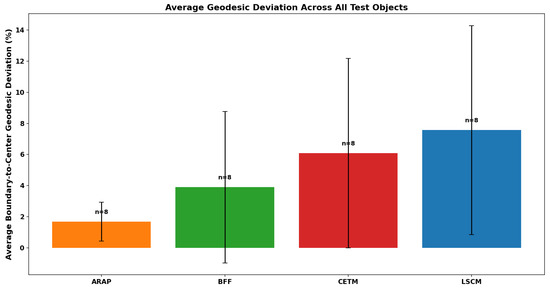

Figure 11 and Figure 12 summarize the average center-to-boundary geodesic deviation. Figure 11 reports the results across eight test objects, while Figure 12 compares the deviation for four parameterization techniques: ARAP, BFF, CETM, LSCM. ARAP achieved the lowest mean deviation of 1.7% with the smallest variance, BFF and CETM gave intermediate performance, and LSCM showed the largest deviation of 7.65% with higher variability.

Figure 11.

Absolute area distortion versus average geodesic deviation for the test meshes across the four parameterization methods (LSCM, CETM, BFF, and ARAP).

Figure 12.

Average geodesic deviation across all parameterization methods.

On average (mean ± std over eight objects), LSCM had the shortest time (0.0668 ± 0.0434 s), followed by ARAP (0.2413 ± 0.1327 s), BFF (0.2973 ± 0.5223 s), and CETM (0.4573 ± 0.4541 s) as described in Table 2. LSCM is fast and conformal but shows the largest spread in area distortion and geodesic deviation. Its free boundary can rescale the boundary to keep angles, which introduces anisotropy near high curvature. These local effects accumulate as radial stretch or compression and appear as uneven 3D spacing after back-projection. LSCM remains popular for its simplicity, stability, and rapid convergence, but in robotic path generation, spatial fidelity is far more critical than marginal gains in computation time. The few seconds of difference between methods are negligible compared to the impact of geometric accuracy on the reconstructed 3D trajectory. In such cases, ARAP provides more consistent reconstruction, preserving both local rigidity and global scale coherence.

Table 2.

Parameterization computation time (in seconds) for each object and method.

4. Conclusions

This work evaluated four free-boundary parameterization techniques, LSCM, BFF, CETM, and ARAP, on triangular meshes of varying geometric complexity, to assess their suitability for trajectory generation on known 3D surfaces. The evaluation procedure consisted of first designing a structured path in the 2D parametric domain and then projecting it back to the 3D surface via barycentric interpolation. To quantify parameterization suitability in this context, the center-to-boundary geodesic deviation was adopted as a reliable and interpretable profile, directly reflecting how faithfully 2D paths aligned with intrinsic 3D geodesics. Among the tested methods, ARAP consistently delivered the lowest average deviation of 1.7% with the smallest variance, making it the preferred choice when area deformation is critical, such as in path generation over known 3D surfaces. BFF and CETM performed competitively on smooth, low-curvature geometries, while LSCM, despite its popularity, exhibited higher and more variable deviations of 7.65% and is therefore less suitable when precise geodesic preservation is required. Overall, ARAP emerges as the most robust default for path planning on known 3D surfaces, with BFF a strong alternative if angle preservation is critical for an application.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.P., C.M. and M.M.; methodology, M.M. and G.P.; validation, M.M. and M.G.; formal analysis, M.M.; investigation, M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M.; writing—review and editing, G.P. and C.M.; supervision, G.P. and C.M.; project administration, G.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Union–NextGenerationEU, with funds made available by the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4, Component 2, Investment 3.3 (M.D. 352/2022), and by SACMI Imola S.C., Italy. Grant CUP: J33C22001460009.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the collaboration of SACMI Imola S.C. and Gaiotto Automation S.p.A. in providing industrial support during this research. During the preparation of this manuscript, authors used OpenAI for language polishing and text refinement. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Mattia Gambazza was employed by SACMI Imola S.C, Italy. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Lévy, B.; Petitjean, S.; Ray, N.; Maillot, J. Least Squares Conformal Maps for Automatic Texture Atlas Generation. ACM Trans. Graph. (TOG) 2002, 21, 362–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawhney, R.; Crane, K. Boundary First Flattening. ACM Trans. Graph. 2017, 37, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Y.; Gotsman, C.; Gortler, S.J. A Local/Global Approach to Mesh Parameterization. Comput. Graph. Forum 2008, 27, 1495–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springborn, B.; Schröder, P.; Pinkall, U. Conformal Equivalence of Triangle Meshes. In SIGGRAPH ’08: ACM SIGGRAPH 2008 Papers; Association for Computing Machinery: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGovern, S.; Xiao, J. UV Grid Generation on 3D Freeform Surfaces for Constrained Robotic Coverage Path Planning. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 18th International Conference on Automation Science and Engineering (CASE), Mexico City, Mexico, 20–24 August 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, N.D.M.; Quinsat, Y.; Lavernhe, S.; Lartigue, C. Scanner Path Planning with the Control of Overlap for Part Inspection with an Industrial Robot. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2018, 98, 629–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weingartshofer, T.; Haddadi, A.; Hartl-Nesic, C.; Kugi, A. Flexible Robotic Drawing on 3D Objects with an Industrial Robot. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Conference on Control Technology and Applications (CCTA), Trieste, Italy, 23–25 August 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weingartshofer, T.; Hartl-Nesic, C.; Kugi, A. Automatic and Flexible Robotic Drawing on Complex Surfaces with an Industrial Robot. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2024, 32, 1602–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Kim, Y.J. Distortion-Free Robotic Surface-Drawing Using Conformal Mapping. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–24 May 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).