Advances in Bioactive Compounds from Plants and Their Applications in Alzheimer’s Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Plant-Derived Bioactive Compounds in the Management of AD

| Phytochemicals | Targeted Mechanisms | Models | Key Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Curcumin | GSK-3β/CDK5 suppression, Aβ binding, ADAM10 boosting, tau kinase inhibition. NF-κB/AMPK modulation. | In vitro assays, scopolamine rats. Cell lines, AD rodent models. Streptozotocin rats, microglia cultures. | Reduced Aβ aggregation, improved cognition. Prevented fibril formation, curtailed tau hyperphosphorylation [13,63,71,72,73,74,75]. |

| EGCG | BACE1 suppression, Aβ oligomer remodeling, APP processing shift, cytokine inhibition, Nrf2 activation. | STZ-AD rats, in vitro assays, hippocampal tissues, STZ rats. | Aβ inhibition, cognitive improvement, 20–40% ROS decrease, mitochondrial restoration [15,18,19,70]. |

| Rosmarinic Acid | Aβ binding, fibril disruption, Aβ oligomerization suppression, aggregate remodeling, AChE inhibition, monoamine modulation. | In vitro assays, AD rodents, Aβ cell lines, rodent impairment models, cortical neurons. | Inhibited aggregation, improved memory, elevated acetylcholine [16,17,54,55,56]. |

| Carnosic Acid | COX-2/NF-κB inhibition, Nrf2 activation, ROS scavenging. | Microglial cultures, rodent models. | ROS reduction, cytokine suppression [16]. |

| Withaferin A | Aβ suppression, NF-κB inhibition, oxidative stress reduction, BDNF/CREB activation. | PC-12 cells, rats, rat cortical neurons. | Reduced Aβ accumulation, protected from cytotoxicity, axon/dendrite outgrowth, restored memory deficits [9,35,76,77,78,79]. |

| Withanoside IV/Sominone/Withanolides | Aβ clearance, neuroinflammation reduction. AChE inhibition, cytokine attenuation. | Aβ-injected mice, 5XFAD mice, Wistar rats, SH-SY5Y cells. | Improved memory, prevented neuronal loss, alleviated cognitive dysfunction [9,35,77,80]. |

| Withanamides A/C | Aβ fibril prevention, BBB permeability. | PC-12 cells. | Protected from Aβ-induced death [9,35,76]. |

| Ginkgolides A/B/C/J | BACE1 reduction, cholesterol lowering, Aβ aggregation inhibition. | APP/PS1 mice, PC-12 cells. | Aβ reduction, improved cognition [36,39]. |

| Bilobalide | Membrane stabilization, ROS scavenging, mitochondrial protection. | Streptozotocin rats, Aβ-injected mice. | ROS decrease, neuronal preservation [39]. |

| EGb 761 Extract | NF-κB suppression, antioxidant upregulation, synaptic modulation. | Aged rodents, AD models. | ROS decrease, restored blood flow [34,36,39]. |

| Bacosides A/B | BACE1 inhibition, Aβ binding, and fibril conversion. AChE inhibition, CREB/BDNF activation, synaptic enhancement. | APP cells, scopolamine rats. Aged rodents, PC-12 cells. | Aβ inhibition, memory reversal. Increased dendritic branching, restored cognition [37,40,41]. |

| Saponins | ROS scavenging, cytokine suppression, antioxidant upregulation. | Streptozotocin rats, neuronal cultures. | Normalized peroxidation, reduced IL-6/TNF-α [37,49]. |

| Ginsenosides Rb1/Rg1 | Aβ clearance enhancement, tau phosphorylation inhibition via PI3K/Akt, AChE inhibition, BDNF promotion, receptor agonism. | APP/PS1 mice, streptozotocin rats, rodent models. | Reduced phosphorylated tau, improved cognition, elevated acetylcholine, enhanced neurogenesis [44,45,46,47]. |

| Compound K | NF-κB suppression, Nrf2 activation, ROS scavenging. | AD rat models. | ROS reduction, anti-inflammatory shift [44,45]. |

| Crocin/Safranal/Trans-crocetin | Monoamine modulation, AChE inhibition, BDNF/CREB promotion. Aβ suppression, tau inhibition, NF-κB suppression, gut barrier enhancement. | Streptozotocin rats, neuronal cultures, scopolamine rats, microbiota models. | Attenuated fibril formation, cytokine reduction, elevated acetylcholine, enhanced synaptic density, improved learning, decreased BBB permeability [51,58,59]. |

| Madecassoside | ROS scavenging, cytokine suppression, Nrf2 activation. | Aged mice, neurodegenerative models. | ROS normalization, reduced inflammation [38,42,43,57]. |

| Triterpenoids | AChE inhibition, BDNF/CREB promotion, synaptic density enhancement. | Cortical neurons, AD models. | Increased dendritic integrity, neurogenesis [38,42,43,57]. |

| Asiaticoside | Aβ attenuation. | 5XFAD mice, neuronal cultures. | Plaque formation inhibition, improved cognition [42,43]. |

| Theanine (with catechins) | Free radical scavenging, metabolic modulation. | Rodent models. | Neuroprotective effects [15,18,19]. |

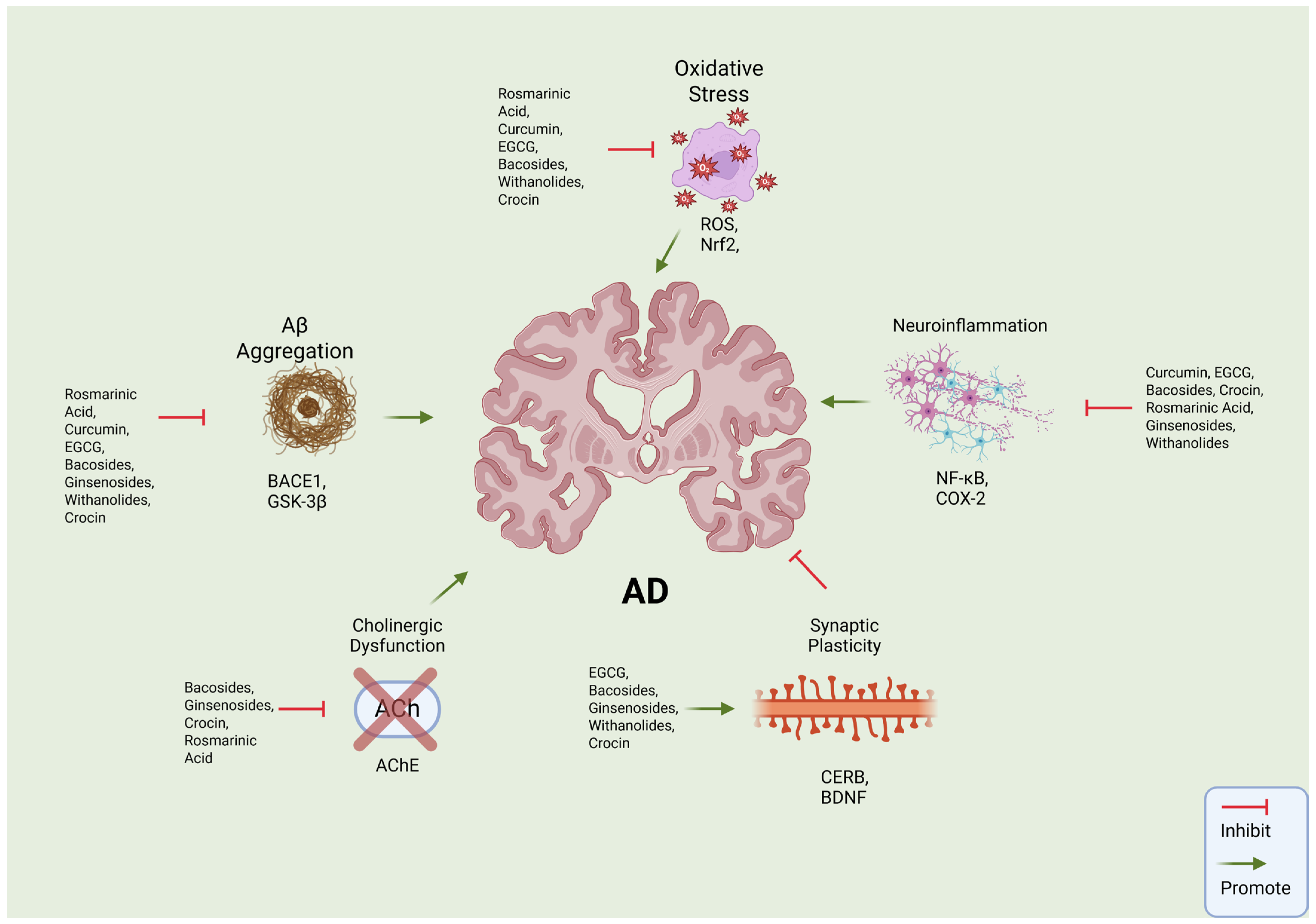

| Pathology | Key Features | Molecular Targets | Key Compounds |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amyloid Cascade | Aberrant APP cleavage by β- and γ-secretase. | BACE1, GSK-3β, ADAM10 | Curcumin, Bacosides, EGCG, Withanolide A [13,15,18,19,37,40,41,49,71,75,81]. |

| Oxidative Stress | Reduced cytochrome-c oxidase, ROS elevation. | Nrf2, SOD, GPx, electron transport chain | Withaferin A, Rosmarinic Acid, EGCG [9,15,16,17,18,19,35,52,53,76,77,78]. |

| Neuroinflammation | Microglial/astrocyte activation, cytokine release. | NF-κB, inflammasomes, IL-1β/TNF-α/IL-6 | Curcumin, Safranal, Bilobalide [13,14,34,36,39,50,51,71,75,81]. |

| Cholinergic Dysfunction | Loss of nucleus basalis neurons, acetylcholine depletion. | AChE, ChAT, muscarinic/nicotinic receptors | Bacosides, Rosmarinic Acid, Ginsenosides [16,17,37,41,45,46,49,52,53,54,55,60,61,82,83]. |

| Impaired Synaptic Plasticity | Loss of synaptic density and connectivity. Reduced dendritic branching and spine density. | BDNF, CREB | Crocin, Asiaticoside, Theanine [14,15,18,19,38,42,50,51,57]. |

| Tau Pathology | Hyperphosphorylation and NFT formation. | GSK-3β, CDK5, PI3K/Akt | Curcumin, Ginsenosides, Crocin [13,14,46,47,51,63,71,75]. |

| Gut–Brain Axis Dysregulation | Dysbiosis, barrier permeability. | SCFA production, vagal signaling, BBB | Curcumin, Ginsenosides, Crocin, Withanolides [35,44,76,80,84]. |

4. Phytochemicals’ Mechanisms of Action

5. Multi-Target Approaches of Phytochemicals

6. Addressing Bioavailability and Delivery Science

7. Bridging Preclinical and Clinical Evidence

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kumar, A.; Sidhu, J.; Lui, F.; Tsao, J.W. Alzheimer Disease. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Safiri, S.; Ghaffari Jolfayi, A.; Fazlollahi, A.; Morsali, S.; Sarkesh, A.; Daei Sorkhabi, A.; Golabi, B.; Aletaha, R.; Motlagh Asghari, K.; Hamidi, S.; et al. Alzheimer’s disease: A comprehensive review of epidemiology, risk factors, symptoms diagnosis, management, caregiving, advanced treatments and associated challenges. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1474043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, U.A.; Liu, L.; Provenzano, F.A.; Berman, D.E.; Profaci, C.P.; Sloan, R.; Mayeux, R.; Duff, K.E.; Small, S.A. Molecular drivers and cortical spread of lateral entorhinal cortex dysfunction in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Neurosci. 2014, 17, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barage, S.H.; Sonawane, K.D. Amyloid cascade hypothesis: Pathogenesis and therapeutic strategies in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropeptides 2015, 52, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twarowski, B.; Herbet, M. Inflammatory Processes in Alzheimer’s Disease-Pathomechanism, Diagnosis and Treatment: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Megur, A.; Baltriukienė, D.; Bukelskienė, V.; Burokas, A. The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis and Alzheimer’s Disease: Neuroinflammation Is to Blame? Nutrients 2020, 13, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Lim, J.; Oh, J. Taming neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease: The protective role of phytochemicals through the gut-brain axis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 178, 117277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, D.T.; Li, R.X.; Sun, J.R.; Rong, X.W.; Guo, X.G.; Zhu, G.D. Global mortality, prevalence and disability-adjusted life years of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias in adults aged 60 years or older, and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic: A comprehensive analysis for the global burden of disease 2021. BMC Psychiatry 2025, 25, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, J.; Vengalasetti, Y.V.; Bredesen, D.E.; Rao, R.V. Neuroprotective Herbs for the Management of Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Sun, Y. Current Status of Plant-Based Bioactive Compounds as Therapeutics in Alzheimer’s Diseases. J. Integr. Neurosci. 2025, 24, 23090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Reiss, A.B.; Pinkhasov, A.; Kasselman, L.J. Plants, Plants, and More Plants: Plant-Derived Nutrients and Their Protective Roles in Cognitive Function, Alzheimer’s Disease, and Other Dementias. Medicina 2022, 58, 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shishtar, E.; Rogers, G.T.; Blumberg, J.B.; Au, R.; Jacques, P.F. Long-term dietary flavonoid intake and risk of Alzheimer disease and related dementias in the Framingham Offspring Cohort. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 112, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, S.; Ye, X.; Su, W.; Wang, Y. Curcumin alleviates Alzheimer’s disease by inhibiting inflammatory response, oxidative stress and activating the AMPK pathway. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 2023, 134, 102363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anaeigoudari, F.; Anaeigoudari, A.; Kheirkhah-Vakilabad, A. A review of therapeutic impacts of saffron (Crocus sativus L.) and its constituents. Physiol. Rep. 2023, 11, e15785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pervin, M.; Unno, K.; Ohishi, T.; Tanabe, H.; Miyoshi, N.; Nakamura, Y. Beneficial Effects of Green Tea Catechins on Neurodegenerative Diseases. Molecules 2018, 23, 1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopresti, A.L. Salvia (Sage): A Review of its Potential Cognitive-Enhancing and Protective Effects. Drugs R&D 2017, 17, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguchi-Shinohara, M.; Ono, K.; Hamaguchi, T.; Nagai, T.; Kobayashi, S.; Komatsu, J.; Samuraki-Yokohama, M.; Iwasa, K.; Yokoyama, K.; Nakamura, H.; et al. Safety and efficacy of Melissa officinalis extract containing rosmarinic acid in the prevention of Alzheimer’s disease progression. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biasibetti, R.; Tramontina, A.C.; Costa, A.P.; Dutra, M.F.; Quincozes-Santos, A.; Nardin, P.; Bernardi, C.L.; Wartchow, K.M.; Lunardi, P.S.; Gonçalves, C.A. Green tea (-)epigallocatechin-3-gallate reverses oxidative stress and reduces acetylcholinesterase activity in a streptozotocin-induced model of dementia. Behav. Brain Res. 2013, 236, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.Y.; Bae, K.; Seong, Y.H.; Song, K.S. Green tea catechins as a BACE1 (beta-secretase) inhibitor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2003, 13, 3905–3908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peron, R.; Vatanabe, I.P.; Manzine, P.R.; Camins, A.; Cominetti, M.R. Alpha-Secretase ADAM10 Regulation: Insights into Alzheimer’s Disease Treatment. Pharmaceuticals 2018, 11, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Du, X.; Han, G.; Gao, W. Association between tea consumption and risk of cognitive disorders: A dose-response meta-analysis of observational studies. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 43306–43321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, M.; Lopes, I.; Magalhães, L.; Sárria, M.P.; Machado, R.; Sousa, J.C.; Botelho, C.; Teixeira, J.; Gomes, A.C. Novel concept of exosome-like liposomes for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Control. Release 2021, 336, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolik, V.V.; Berchenko, O.G. The cumulative effect of the combined action of miR-101 and curcumin in a liposome on a model of Alzheimer’s disease in mononuclear cells. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1169980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matharoo, N.; Mohd, H.; Michniak-Kohn, B. Transferosomes as a transdermal drug delivery system: Dermal kinetics and recent developments. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 16, e1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, M.; Saraf, S.; Pradhan, M.; Patel, R.J.; Singhvi, G.; Ajazuddin; Alexander, A. Design and optimization of curcumin loaded nano lipid carrier system using Box-Behnken design. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 141, 111919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, H.; Gad, H.A.; Khattab, M.A.; Mansour, M. The Tragedy of Alzheimer’s Disease: Towards Better Management via Resveratrol-Loaded Oral Bilosomes. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pires, P.C.; Paiva-Santos, A.C.; Veiga, F. Liposome-Derived Nanosystems for the Treatment of Behavioral and Neurodegenerative Diseases: The Promise of Niosomes, Transfersomes, and Ethosomes for Increased Brain Drug Bioavailability. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asani, E.; Hatami, H.; Hamidian, G.; Hatami, S. Investigating the Effects of Niosome Curcumin on the Alteration of NF-κB Gene Expression and Memory and Learning in the Prefrontal Cortex of Alzheimer’s Rats. Mol. Neurobiol. 2025, 62, 13707–13721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwish, A.B.; Salama, A.; Younis, M.M. Neuroprotective efficiency of celecoxib vesicular bilosomes for the management of lipopolysaccharide-induced Alzheimer in mice employing 2(3) full factorial design. Inflammopharmacology 2024, 32, 3925–3942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsheikh, M.A.; El-Feky, Y.A.; Al-Sawahli, M.M.; Ali, M.E.; Fayez, A.M.; Abbas, H. A Brain-Targeted Approach to Ameliorate Memory Disorders in a Sporadic Alzheimer’s Disease Mouse Model via Intranasal Luteolin-Loaded Nanobilosomes. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, K.; Ahmad, M.Z.; Saikia, R.; Pathak, M.P.; Sahariah, J.J.; Kalita, P.; Das, A.; Islam, M.A.; Pramanik, P.; Tayeng, D.; et al. Nanomedicine: A New Frontier in Alzheimer’s Disease Drug Targeting. Central Nerv. Syst. Agents Med. Chem. 2025, 25, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khishvand, M.A.; Yeganeh, E.M.; Zarei, M.; Soleimani, M.; Mohammadi, M.; Mahjub, R. Development, Statistical Optimization, and Characterization of Resveratrol-Containing Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLNs) and Determination of the Efficacy in Reducing Neurodegenerative Symptoms Related to Alzheimer’s Disease: In Vitro and In Vivo Study. Biomed. Res. Int. 2024, 2024, 7877265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalili, C.; Kiani, A.; Gholami, M.; Bahrehmand, F.; Fakhri, S.; Kakehbaraei, S.; Kakebaraei, S. Brain targeting based nanocarriers loaded with resveratrol in Alzheimer’s disease: A review. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2023, 17, 154–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, A.; Kojder, K.; Zielonka-Brzezicka, J.; Wróbel, J.; Bosiacki, M.; Fabiańska, M.; Wróbel, M.; Sołek-Pastuszka, J.; Klimowicz, A. The Use of Ginkgo biloba L. as a Neuroprotective Agent in the Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 775034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerose, V.; Ponticelli, M.; Benedetto, N.; Carlucci, V.; Lela, L.; Tzvetkov, N.T.; Milella, L. Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal, a Potential Source of Phytochemicals for Treating Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Systematic Review. Plants 2024, 13, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.K.; Srivastav, S.; Castellani, R.J.; Plascencia-Villa, G.; Perry, G. Neuroprotective and Antioxidant Effect of Ginkgo biloba Extract Against AD and Other Neurological Disorders. Neurotherapeutics 2019, 16, 666–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Manap, A.S.; Vijayabalan, S.; Madhavan, P.; Chia, Y.Y.; Arya, A.; Wong, E.H.; Rizwan, F.; Bindal, U.; Koshy, S. Bacopa monnieri, a Neuroprotective Lead in Alzheimer Disease: A Review on Its Properties, Mechanisms of Action, and Preclinical and Clinical Studies. Drug Target Insights 2019, 13, 1177392819866412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, N.E.; Zweig, J.A.; Caruso, M.; Martin, M.D.; Zhu, J.Y.; Quinn, J.F.; Soumyanath, A. Centella asiatica increases hippocampal synaptic density and improves memory and executive function in aged mice. Brain Behav. 2018, 8, e01024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Hao, W.; Qin, Y.; Decker, Y.; Wang, X.; Burkart, M.; Schötz, K.; Menger, M.D.; Fassbender, K.; Liu, Y. Long-term treatment with Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761 improves symptoms and pathology in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Behav. Immun. 2015, 46, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangeet, S.; Khan, A. Bacopa monnieri phytochemicals as promising BACE1 inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease therapy. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 13504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preethi, J.; Singh, H.K.; Charles, P.D.; Rajan, K.E. Participation of microRNA 124-CREB pathway: A parallel memory enhancing mechanism of standardised extract of Bacopa monniera (BESEB CDRI-08). Neurochem. Res. 2012, 37, 2167–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, D.G.; Caruso, M.; Murchison, C.F.; Zhu, J.Y.; Wright, K.M.; Harris, C.J.; Gray, N.E.; Quinn, J.F.; Soumyanath, A. Centella Asiatica Improves Memory and Promotes Antioxidative Signaling in 5XFAD Mice. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teerapattarakan, N.; Kamsrijai, U.; Janyou, A.; Hankittichai, P.; Anukanon, S.; Hawiset, T.; Issara, U. Preclinical neuropharmacological effects of Centella asiatica-derived asiaticoside and madecassoside in Alzheimer’s disease. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2025, 180, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, W.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, P.; Cui, R. Effects of Ginseng on Neurological Disorders. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.J.; Jung, S.W.; Kim, S.Y.; Cho, I.H.; Kim, H.C.; Rhim, H.; Kim, M.; Nah, S.Y. Panax ginseng as an adjuvant treatment for Alzheimer’s disease. J. Ginseng Res. 2018, 42, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Oh, J.P.; Yoo, M.; Cui, C.H.; Jeon, B.M.; Kim, S.C.; Han, J.H. Minor ginsenoside F1 improves memory in APP/PS1 mice. Mol. Brain 2019, 12, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Bi, P.; Qi, Z.; Zhang, C. Anti-neuroinflammation effect of ginsenoside Rbl in a rat model of Alzheimer disease. Neurosci. Lett. 2011, 487, 70–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Tang, G.; Li, L.; Shu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, L.; Tang, J. Herbal medicine and gut microbiota: Exploring untapped therapeutic potential in neurodegenerative disease management. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2024, 47, 146–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukumaran, N.P.; Amalraj, A.; Gopi, S. Neuropharmacological and cognitive effects of Bacopa monnieri (L.) Wettst—A review on its mechanistic aspects. Complement. Ther. Med. 2019, 44, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshiri, M.; Vahabzadeh, M.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Clinical Applications of Saffron (Crocus sativus) and its Constituents: A Review. Drug Res. 2015, 65, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatziagapiou, K.; Kakouri, E.; Lambrou, G.I.; Bethanis, K.; Tarantilis, P.A. Antioxidant Properties of Crocus Sativus L. and Its Constituents and Relevance to Neurodegenerative Diseases; Focus on Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Disease. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2019, 17, 377–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd El-Hack, M.E.; Rudayni, H.A.; Aldhalmi, A.K.; Youssef, I.M.; Arif, M.; Alawam, A.S.; Allam, A.A.; Khafaga, A.F.; Ashour, E.A.; Khan, M.M.H. Beyond traditional uses: Unveiling the epigenetic, microbiome-modulating, metabolic, and nutraceutical benefits of Salvia officinalis in human and livestock nutrition. J. Funct. Foods 2025, 128, 106843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertas, A.; Yigitkan, S.; Orhan, I.E. A Focused Review on Cognitive Improvement by the Genus Salvia L. (Sage)-From Ethnopharmacology to Clinical Evidence. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeri, A.; Sahebkar, A.; Javadi, B. Melissa officinalis L.—A review of its traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 188, 204–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, D.O.; Scholey, A.B.; Tildesley, N.T.; Perry, E.K.; Wesnes, K.A. Modulation of mood and cognitive performance following acute administration of Melissa officinalis (lemon balm). Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2002, 72, 953–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahboubi, M. Melissa officinalis and rosmarinic acid in management of memory functions and Alzheimer disease. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2019, 9, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Wu, L.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Qin, L.; Hayashi, M.; Kudo, M.; Gao, M.; Liu, T. Therapeutic Potential of Centella asiatica and Its Triterpenes: A Review. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 568032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ide, K.; Yamada, H.; Takuma, N.; Park, M.; Wakamiya, N.; Nakase, J.; Ukawa, Y.; Sagesaka, Y.M. Green tea consumption affects cognitive dysfunction in the elderly: A pilot study. Nutrients 2014, 6, 4032–4042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García, C.J.; Beltrán, D.; Frutos-Lisón, M.D.; García-Conesa, M.T.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A.; García-Villalba, R. New findings in the metabolism of the saffron apocarotenoids, crocins and crocetin, by the human gut microbiota. Food Funct. 2024, 15, 9315–9329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalini, V.T.; Neelakanta, S.J.; Sriranjini, J.S. Neuroprotection with Bacopa monnieri-A review of experimental evidence. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 2653–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lho, S.K.; Kim, T.H.; Kwak, K.P.; Kim, K.; Kim, B.J.; Kim, S.G.; Kim, J.L.; Kim, T.H.; Moon, S.W.; Park, J.Y.; et al. Effects of lifetime cumulative ginseng intake on cognitive function in late life. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2018, 10, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, A.J.; Sreenivasan, C.; Parikh, A.; AlQassab, O.; Kanthajan, T.; Pandey, M.; Nwosu, M. Curcumin and Cognitive Function: A Systematic Review of the Effects of Curcumin on Adults With and Without Neurocognitive Disorders. Cureus 2024, 16, e67706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCubrey, J.A.; Lertpiriyapong, K.; Steelman, L.S.; Abrams, S.L.; Cocco, L.; Ratti, S.; Martelli, A.M.; Candido, S.; Libra, M.; Montalto, G.; et al. Regulation of GSK-3 activity by curcumin, berberine and resveratrol: Potential effects on multiple diseases. Adv. Biol. Regul. 2017, 65, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riepe, M.; Hoerr, R.; Schlaefke, S. Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761 is safe and effective in the treatment of mild dementia—a meta-analysis of patient subgroups in randomised controlled trials. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2025, 26, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pase, M.P.; Kean, J.; Sarris, J.; Neale, C.; Scholey, A.B.; Stough, C. The cognitive-enhancing effects of Bacopa monnieri: A systematic review of randomized, controlled human clinical trials. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2012, 18, 647–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayati, Z.; Yang, G.; Ayati, M.H.; Emami, S.A.; Chang, D. Saffron for mild cognitive impairment and dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2020, 20, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhondzadeh, S.; Noroozian, M.; Mohammadi, M.; Ohadinia, S.; Jamshidi, A.H.; Khani, M. Melissa officinalis extract in the treatment of patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease: A double blind, randomised, placebo controlled trial. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2003, 74, 863–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puttarak, P.; Dilokthornsakul, P.; Saokaew, S.; Dhippayom, T.; Kongkaew, C.; Sruamsiri, R.; Chuthaputti, A.; Chaiyakunapruk, N. Effects of Centella asiatica (L.) Urb. on cognitive function and mood related outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, A.L. Network pharmacology: The next paradigm in drug discovery. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008, 4, 682–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pervin, M.; Unno, K.; Takagaki, A.; Isemura, M.; Nakamura, Y. Function of Green Tea Catechins in the Brain: Epigallocatechin Gallate and its Metabolites. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Huang, W.; Huang, J.; Luo, Y.; Huang, N. Natural bioactive compounds form herbal medicine in Alzheimer’s disease: From the perspective of GSK-3β. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1497861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzini, E.; Peña-Corona, S.I.; Hernández-Parra, H.; Chandran, D.; Saleena, L.A.K.; Sawikr, Y.; Peluso, I.; Dhumal, S.; Kumar, M.; Leyva-Gómez, G.; et al. Neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects of curcumin in Alzheimer’s disease: Targeting neuroinflammation strategies. Phytother. Res. 2024, 38, 3169–3189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narasingappa, R.B.; Javagal, M.R.; Pullabhatla, S.; Htoo, H.H.; Rao, J.K.; Hernandez, J.F.; Govitrapong, P.; Vincent, B. Activation of α-secretase by curcumin-aminoacid conjugates. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 424, 691–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Lim, G.P.; Begum, A.N.; Ubeda, O.J.; Simmons, M.R.; Ambegaokar, S.S.; Chen, P.P.; Kayed, R.; Glabe, C.G.; Frautschy, S.A.; et al. Curcumin Inhibits Formation of Amyloid β Oligomers and Fibrils, Binds Plaques, and Reduces Amyloid in Vivo*. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 5892–5901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, T.; Zhang, Y.; Botchway, B.O.A.; Zhang, J.; Fan, R.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X. Curcumin can improve Parkinson’s disease via activating BDNF/PI3k/Akt signaling pathways. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2022, 164, 113091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullaiah, C.P.; Sp, P.P.; Sk, P.; Nemalapalli, Y.; Birudala, G.; Lahari, S.; Vippamakula, S.; Shakila, R.; Ganjayi, M.S.; Mitta, R. Exploring Withanolides from Withania somnifera: A Promising Avenue for Alzheimer’s Disease Treatment. Curr. Pharmacol. Rep. 2025, 11, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulska, P.; Malinowska, M.; Ignacyk, M.; Szustowski, P.; Nowak, J.; Pesta, K.; Szeląg, M.; Szklanny, D.; Judasz, E.; Kaczmarek, G.; et al. Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera)-Current Research on the Health-Promoting Activities: A Narrative Review. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuboyama, T.; Tohda, C.; Komatsu, K. Neuritic regeneration and synaptic reconstruction induced by withanolide A. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2005, 144, 961–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuboyama, T.; Tohda, C.; Zhao, J.; Nakamura, N.; Hattori, M.; Komatsu, K. Axon- or dendrite-predominant outgrowth induced by constituents from Ashwagandha. Neuroreport 2002, 13, 1715–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, C.T. Dysfunction of the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis in Neurodegenerative Disease: The Promise of Therapeutic Modulation With Prebiotics, Medicinal Herbs, Probiotics, and Synbiotics. J. Evid. Based Integr. Med. 2020, 25, 2515690x20957225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voulgaropoulou, S.D.; van Amelsvoort, T.; Prickaerts, J.; Vingerhoets, C. The effect of curcumin on cognition in Alzheimer’s disease and healthy aging: A systematic review of pre-clinical and clinical studies. Brain Res. 2019, 1725, 146476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandimalla, R.; Reddy, P.H. Therapeutics of Neurotransmitters in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2017, 57, 1049–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.I.; Park, K.S.; Cho, I.H. Panax ginseng: A candidate herbal medicine for autoimmune disease. J. Ginseng Res. 2019, 43, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Mou, C.; Hu, Y.; He, Z.; Cho, J.Y.; Kim, J.H. In vivo metabolism, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacological activities of ginsenosides from ginseng. J. Ginseng Res. 2025, 49, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabska-Kobyłecka, I.; Szpakowski, P.; Król, A.; Książek-Winiarek, D.; Kobyłecki, A.; Głąbiński, A.; Nowak, D. Polyphenols and Their Impact on the Prevention of Neurodegenerative Diseases and Development. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, S.K.; Yadav, D.; Katiyar, S.; Jain, S.; Yadav, H. Postbiotics as Mitochondrial Modulators in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Mechanistic Insights and Therapeutic Potential. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai Shi Min, S.; Liew, S.Y.; Chear, N.J.Y.; Goh, B.H.; Tan, W.-N.; Khaw, K.Y. Plant Terpenoids as the Promising Source of Cholinesterase Inhibitors for Anti-AD Therapy. Biology 2022, 11, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konrath, E.L.; Passos, C.D.S.; Klein-Júnior, L.C.; Henriques, A.T. Alkaloids as a source of potential anticholinesterase inhibitors for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2013, 65, 1701–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prajapati, S.K.; Lekkala, L.; Yadav, D.; Jain, S.; Yadav, H. Microbiome and Postbiotics in Skin Health. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoanaivo, P.; Wright, C.W.; Willcox, M.L.; Gilbert, B. Whole plant extracts versus single compounds for the treatment of malaria: Synergy and positive interactions. Malar. J. 2011, 10, S4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, T.K.; Jana, P.; Chakrabarti, S.K.; Abdul Hamid, M.R.W. Curcumin Downregulates GSK3 and Cdk5 in Scopolamine-Induced Alzheimer’s Disease Rats Abrogating Aβ40/42 and Tau Hyperphosphorylation. J. Alzheimers Dis. Rep. 2019, 3, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, L.; Liu, L.; Ji, H.-F. Regulative effects of curcumin spice administration on gut microbiota and its pharmacological implications. Food Nutr. Res. 2017, 61, 1361780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.-X.; Han, Z.; Drieu, K.; Papadopoulos, V. Ginkgo biloba extract (Egb 761) inhibits beta-amyloid production by lowering free cholesterol levels. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2004, 15, 749–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Xing, Y.; Gao, Q.; Wang, D.; Chen, H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y. Ginkgo biloba Extract Drives Gut Flora and Microbial Metabolism Variation in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, R.; Singh, H.K.; Prasad, S. A Special Extract of Bacopa monnieri (CDRI-08) Restores Learning and Memory by Upregulating Expression of the NMDA Receptor Subunit GluN2B in the Brain of Scopolamine-Induced Amnesic Mice. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 2015, 254303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sushma; Sahu, M.R.; Murugan, N.A.; Mondal, A.C. Amelioration of Amyloid-β Induced Alzheimer’s Disease by Bacopa monnieri through Modulation of Mitochondrial Dysfunction and GSK-3β/Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2023, 68, e2300245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radhika Kapoor, S.S.; Kakkar, P. Bacopa monnieri modulates antioxidant responses in brain and kidney of diabetic rats. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2009, 27, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, M.; Ojha, R.P.; Prabu, P.C.; Devi, B.P.; Agrawal, A.; Dubey, G.P. Prevention of age-associated neurodegeneration and promotion of healthy brain ageing in female Wistar rats by long term use of bacosides. Biogerontology 2012, 13, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Pi, Y.; Ma, L.; Li, F.; Luo, J.; Cai, Y.; Wu, Y.; Liu, M.; Dai, Y.; Zheng, F.; et al. Effects of ginseng on short-chain fatty acids and intestinal microbiota in rats with spleen-qi deficiency based on gas chromatography-mass spectrometry and 16s rRNA technology. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2023, 37, e9640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, T.; Abnous, K.; Vahdati, F.; Mehri, S.; Razavi, B.M.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Antidepressant Effect of Crocus sativus Aqueous Extract and its Effect on CREB, BDNF, and VGF Transcript and Protein Levels in Rat Hippocampus. Drug Res. 2015, 65, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Cheng, W.; Wang, D.; Zeng, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, T.; Zhang, L.; Yang, J.; Sun, L.; et al. Amelioration of cognitive impairment using epigallocatechin-3-gallate in ovariectomized mice fed a high-fat diet involves remodeling with Prevotella and Bifidobacteriales. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 13, 1079313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhapola, R.; Beura, S.K.; Sharma, P.; Singh, S.K.; Harikrishnareddy, D. Oxidative stress in Alzheimer’s disease: Current knowledge of signaling pathways and therapeutics. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2024, 51, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challa, V.; Prajapati, S.K.; Gangani, S.; Yadav, D.; Lekkala, L.; Jain, S.; Yadav, H. Microbiome–Aging–Wrinkles Axis of Skin: Molecular Insights and Microbial Interventions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Wang, Y.; Luo, G. Ligustrazine Phosphate Ethosomes for Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease, In Vitro and in Animal Model Studies. AAPS PharmSciTech 2012, 13, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, K.H.M.; White, D.J.; Pipingas, A.; Poorun, K.; Scholey, A. Further Evidence of Benefits to Mood and Working Memory from Lipidated Curcumin in Healthy Older People: A 12-Week, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Partial Replication Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rainey-Smith, S.R.; Brown, B.M.; Sohrabi, H.R.; Shah, T.; Goozee, K.G.; Gupta, V.B.; Martins, R.N. Curcumin and cognition: A randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind study of community-dwelling older adults. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 115, 2106–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.S.; Gopal, P.M.; Thomas, J.V.; Mohan, M.C.; Thomas, S.C.; Maliakel, B.P.; Krishnakumar, I.M.; Pulikkaparambil Sasidharan, B.C. Influence of CurQfen(®)-curcumin on cognitive impairment: A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, 3-arm, 3-sequence comparative study. Front. Dement. 2023, 2, 1222708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Small, G.W.; Siddarth, P.; Li, Z.; Miller, K.J.; Ercoli, L.; Emerson, N.D.; Martinez, J.; Wong, K.-P.; Liu, J.; Merrill, D.A.; et al. Memory and Brain Amyloid and Tau Effects of a Bioavailable Form of Curcumin in Non-Demented Adults: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled 18-Month Trial. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2018, 26, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-T.; Chu, K.; Sim, J.-Y.; Heo, J.-H.; Kim, M. Panax Ginseng Enhances Cognitive Performance in Alzheimer Disease. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2008, 22, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshvar, A.; Jouzdani, A.F.; Firozian, F.; Asl, S.S.; Mohammadi, M.; Ranjbar, A. Neuroprotective effects of crocin and crocin-loaded niosomes against the paraquat-induced oxidative brain damage in rats. Open Life Sci. 2022, 17, 1174–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghnia, H.R.; Shaterzadeh, H.; Forouzanfar, F.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Neuroprotective effect of safranal, an active ingredient of Crocus sativus, in a rat model of transient cerebral ischemia. Folia Neuropathol. 2017, 3, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezai-Zadeh, K.; Arendash, G.W.; Hou, H.; Fernandez, F.; Jensen, M.; Runfeldt, M.; Shytle, R.D.; Tan, J. Green tea epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) reduces β-amyloid mediated cognitive impairment and modulates tau pathology in Alzheimer transgenic mice. Brain Res. 2008, 1214, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smach, M.A.; Hafsa, J.; Charfeddine, B.; Dridi, H.; Limem, K. Effects of sage extract on memory performance in mice and acetylcholinesterase activity. Ann. Pharm. Fr. 2015, 73, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhondzadeh, S.; Noroozian, M.; Mohammadi, M.; Ohadinia, S.; Jamshidi, A.H.; Khani, M. Salvia officinalis extract in the treatment of patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease: A double blind, randomized and placebo-controlled trial. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2003, 28, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamaguchi, T.; Ono, K.; Murase, A.; Yamada, M. Phenolic Compounds Prevent Alzheimer’s Pathology through Different Effects on the Amyloid-β Aggregation Pathway. Am. J. Pathol. 2009, 175, 2557–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Plant | Preclinical Key Findings | Clinical Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Withania somnifera | Dendrite outgrowth and regeneration (in vitro WL-A 1 μM for 7 days) memory recovery (in vivo 10 μM/kg daily for 13 days) [78]. | Memory improvement in MCI (n = 50, RCT, 300 mg twice daily, 8 weeks) [9]. |

| Curcuma longa | Improving cognitive/spatial memory while reducing cytokines and increasing SOD in amyloid-β1–42-injected mice (150 mg/kg daily 10 days) [13]. | Cognitive gains (n = 79, RCT, 80 mg orally, once daily, 12 weeks) [105]. No observable difference between placebo and treatment group (n = 96, RCT, 12 months, 1500 mg daily) [106]. Improved cognitive and locomotive function in AD (n = 48, RCT, 800 mg daily for 6 months) [107]. Improved memory and attention (n = 40, RCT, 180 mg daily for 18 months) [108]. |

| Ginkgo biloba | Decreased Aβ production and attenuated synaptic loss in APP mice (240 mg daily for 5 months) [39]. | Improved symptoms in mild dementia (n = 782, meta-analysis of RCT, 240 mg) [64]. |

| Bacopa monnieri | Improved memory and learning in streptozotocin Wistar rats (30 mg/kg orally 2 weeks) [37]. | Memory enhancement in healthy adults (systematic review of 6 RCTs, 3 of which used 450 mg daily) [65]. |

| Panax ginseng | Spatial working memory improvements in APP/PS1 mice (20 mg/kg daily orally of F1 for 8 weeks) [46]. Reversed neuroinflammation in Aβ1–42-injected rats treated with Rb1 [47]. | Cognitive improvement in AD trials (n = 97, RCT, 4.5 g daily for 12 weeks) [109]. |

| Crocus sativus | Decreased neuroinflammation (n = 30 rats, 20 mg/kg for 7 days) [110]. Increased antioxidants and decreased lipid peroxidation (MCAO rats, 72.5, 145 mg/kg for 4 weeks) [111]. | Significantly improves cognition (n = 54, RCT, 30 mg daily, 22 weeks; n = 46, RCT, 30 mg daily, 16 weeks; n = 68, RCT, 30 mg daily, 48 weeks; n = 35, RCT, 125 mg daily, 48 weeks) [66]. |

| Camellia sinensis | Cognitive improvement, decreased Aβ and tau (APPSw mice, 20 mg/kg for 60 days intraperitoneal injection, 50 mg/kg for 6 months orally) [112]. | Lowers risk of cognitive disorder (meta-analysis of n = 21,444, 6 cohort, n = 6249, 3 case-control, n = 20,742, 8 cross-sectional studies) [21]. |

| Salvia officinalis | Lowers AChE activity in mice (300 mg/kg for 7 days) [113] | Significant improvement in cognition (n = 42, RCT) [114]. |

| Melissa officinalis | Aβ reduction in AD mice (Tg2576) for 10 months from the age of 5 months orally [115]. | Reduced agitation and improved cognitive function in patients with AD (n = 42, RCT, 4 months) [67]. |

| Centella asiatica | Increased synaptic density and cognition (20-month-old CB6F1 mice, 2 mg/mL in drinking water for 2 weeks) [38]. | No difference in cognitive function (meta-analysis of 11 RCTs) [68]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pavlov, S.; Prajapati, S.K.; Yadav, D.; Marcano-Rodriguez, A.; Yadav, H.; Jain, S. Advances in Bioactive Compounds from Plants and Their Applications in Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomolecules 2026, 16, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010007

Pavlov S, Prajapati SK, Yadav D, Marcano-Rodriguez A, Yadav H, Jain S. Advances in Bioactive Compounds from Plants and Their Applications in Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomolecules. 2026; 16(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010007

Chicago/Turabian StylePavlov, Steve, Santosh Kumar Prajapati, Dhananjay Yadav, Andrea Marcano-Rodriguez, Hariom Yadav, and Shalini Jain. 2026. "Advances in Bioactive Compounds from Plants and Their Applications in Alzheimer’s Disease" Biomolecules 16, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010007

APA StylePavlov, S., Prajapati, S. K., Yadav, D., Marcano-Rodriguez, A., Yadav, H., & Jain, S. (2026). Advances in Bioactive Compounds from Plants and Their Applications in Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomolecules, 16(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010007