Protein S-Palmitoylation as Potential Therapeutic Target for Dermatoses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Protein S-Palmitoylation and Its Catalytic Enzyme

3. Protein S-Palmitoylation Impacts Skin Physiological Processes and Dermatosis

3.1. Skin Barrier

3.2. Melanogenesis

3.3. Skin Virus Infection

3.4. Alopecia

3.5. Atopic Dermatitis, Psoriasis and Other Skin Inflammatory Processes

3.6. Skin Carcinogenesis

4. Protein S-Palmitoylation Exerts Roles Through Impacting Cellular or Physiological Processes

4.1. Cellular Differentiation

4.2. Autophagy

4.3. Pyroptosis

4.4. Ferroptosis

4.5. Apoptosis

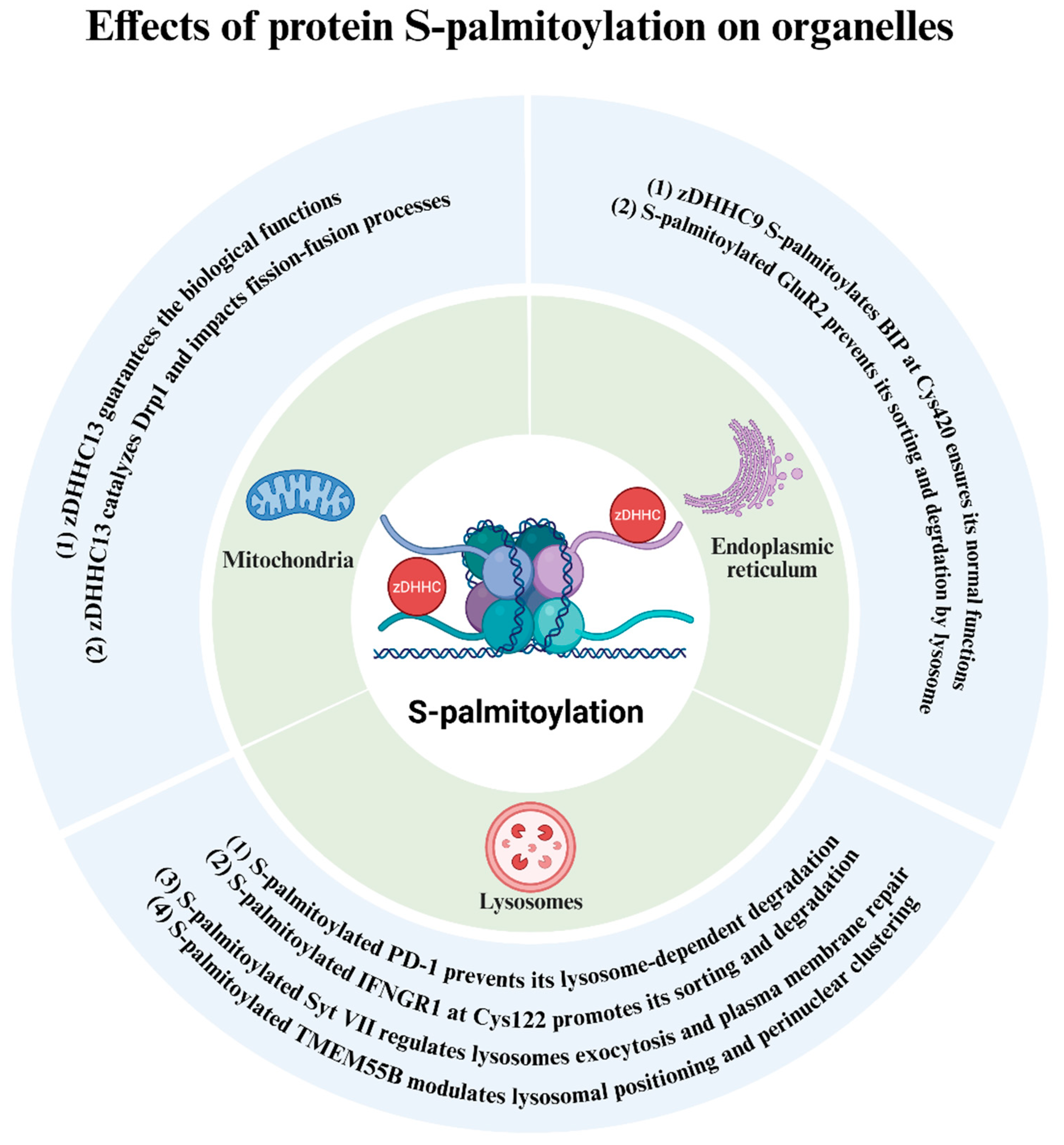

5. Protein S-Palmitoylation Exerts Its Roles Through Impacting Specific Organelles

5.1. Mitochondria

5.2. Endoplasmic Reticulum

5.3. Lysosomes

6. Great Treatment Potential of Protein S-Palmitoylation Inhibitors in Dermatosis

7. Conclusions and Perspective

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Beltrao, P.; Bork, P.; Krogan, N.J.; van Noort, V. Evolution and functional cross-talk of protein post-translational modifications. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2013, 9, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deribe, Y.L.; Pawson, T.; Dikic, I. Post-translational modifications in signal integration. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010, 17, 666–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, E.K.; Zachman, D.K.; Hirschey, M.D. Discovering the landscape of protein modifications. Mol. Cell 2021, 81, 1868–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Zhang, X.; Chen, X.; Aramsangtienchai, P.; Tong, Z.; Lin, H. Protein Lipidation: Occurrence, Mechanisms, Biological Functions, and Enabling Technologies. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 919–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anwar, M.U.; van der Goot, F.G. Refining S-acylation: Structure, regulation, dynamics, and therapeutic implications. J. Cell Biol. 2023, 222, e202307103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.; Sun, Y.; Niu, J.; Jarugumilli, G.K.; Wu, X. Protein Lipidation in Cell Signaling and Diseases: Function, Regulation, and Therapeutic Opportunities. Cell Chem. Biol. 2018, 25, 817–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resh, M.D. Covalent lipid modifications of proteins. Curr. Biol. 2013, 23, R431–R435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.M.; Hang, H.C. Protein S-palmitoylation in cellular differentiation. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2017, 45, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blaskovic, S.; Blanc, M.; van der Goot, F.G. What does S-palmitoylation do to membrane proteins? FEBS J. 2013, 280, 2766–2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, M.E.; Deschenes, R.J. Palmitoylation: Policing protein stability and traffic. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-Y.; Yang-Yen, H.-F.; Tsai, C.-C.; Thio, C.L.-P.; Chuang, H.-L.; Yang, L.-T.; Shen, L.-F.; Song, I.W.; Liu, K.-M.; Huang, Y.-T.; et al. Protein Palmitoylation by ZDHHC13 Protects Skin against Microbial-Driven Dermatitis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2017, 137, 894–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, B.; Yang, W.; Li, W.; He, L.; Lu, L.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chao, T.; Huang, R.; et al. Zdhhc2 Is Essential for Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells Mediated Inflammatory Response in Psoriasis. Front. Immunol. 2021, 11, 607442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDonald, M.E.; Saleem, A.N.; Chen, Y.-H.; Baek, H.J.; Hsiao, Y.-W.; Huang, H.-W.; Kao, H.-J.; Liu, K.-M.; Shen, L.-F.; Song, I.w.; et al. Mice with Alopecia, Osteoporosis, and Systemic Amyloidosis Due to Mutation in Zdhhc13, a Gene Coding for Palmitoyl Acyltransferase. PLoS Genet. 2010, 6, e1000985. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.-Y.; Lin, K.-R.; Chen, Y.-J.; Chiang, Y.-J.; Ho, K.-C.; Shen, L.-F.; Song, I.W.; Liu, K.-M.; Yang-Yen, H.-F.; Chen, Y.-J.; et al. Palmitoyl Acyltransferase Activity of ZDHHC13 Regulates Skin Barrier Development Partly by Controlling PADi3 and TGM1 Protein Stability. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2020, 140, 959–970.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niki, Y.; Adachi, N.; Fukata, M.; Fukata, Y.; Oku, S.; Makino-Okamura, C.; Takeuchi, S.; Wakamatsu, K.; Ito, S.; Declercq, L.; et al. S-Palmitoylation of Tyrosinase at Cysteine500 Regulates Melanogenesis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2023, 143, 317–327.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhu, H.; Whiteheart, S.W. Dynamic cycling of t-SNARE acylation regulates platelet exocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 3593–3606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noland, C.L.; Gierke, S.; Schnier, P.D.; Murray, J.; Sandoval, W.N.; Sagolla, M.; Dey, A.; Hannoush, R.N.; Fairbrother, W.J.; Cunningham, C.N. Palmitoylation of TEAD Transcription Factors Is Required for Their Stability and Function in Hippo Pathway Signaling. Structure 2016, 24, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, F.S.; Abrami, L.; Linder, M.E.; Bamji, S.X.; Dickinson, B.C.; van der Goot, F.G. Mechanisms and functions of protein S-acylation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 488–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrami, L.; Audagnotto, M.; Ho, S.; Marcaida, M.J.; Mesquita, F.S.; Anwar, M.U.; Sandoz, P.A.; Fonti, G.; Pojer, F.; Dal Peraro, M.; et al. Palmitoylated acyl protein thioesterase APT2 deforms membranes to extract substrate acyl chains. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2021, 17, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, F.S.; Abrami, L.; Sergeeva, O.; Turelli, P.; Qing, E.; Kunz, B.; Raclot, C.; Paz Montoya, J.; Abriata, L.A.; Gallagher, T.; et al. S-acylation controls SARS-CoV-2 membrane lipid organization and enhances infectivity. Dev. Cell 2021, 56, 2790–2807.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorleku, O.A.; Barns, A.-M.; Prescott, G.R.; Greaves, J.; Chamberlain, L.H. Endoplasmic Reticulum Localization of DHHC Palmitoyltransferases Mediated by Lysine-based Sorting Signals. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 39573–39584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocks, O.; Gerauer, M.; Vartak, N.; Koch, S.; Huang, Z.-P.; Pechlivanis, M.; Kuhlmann, J.; Brunsveld, L.; Chandra, A.; Ellinger, B.; et al. The Palmitoylation Machinery Is a Spatially Organizing System for Peripheral Membrane Proteins. Cell 2010, 141, 458–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohno, Y.; Kihara, A.; Sano, T.; Igarashi, Y. Intracellular localization and tissue-specific distribution of human and yeast DHHC cysteine-rich domain-containing proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2006, 1761, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korycka, J.; Łach, A.; Heger, E.; Bogusławska, D.M.; Wolny, M.; Toporkiewicz, M.; Augoff, K.; Korzeniewski, J.; Sikorski, A.F. Human DHHC proteins: A spotlight on the hidden player of palmitoylation. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2012, 91, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solis, G.P.; Kazemzadeh, A.; Abrami, L.; Valnohova, J.; Alvarez, C.; van der Goot, F.G.; Katanaev, V.L. Local and substrate-specific S-palmitoylation determines subcellular localization of Gαo. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.-J.; Stix, R.; Rana, M.S.; Shikwana, F.; Murphy, R.E.; Ghirlando, R.; Faraldo-Gómez, J.D.; Banerjee, A. Bivalent recognition of fatty acyl-CoA by a human integral membrane palmitoyltransferase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2022050119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jennings, B.C.; Linder, M.E. DHHC Protein S-Acyltransferases Use Similar Ping-Pong Kinetic Mechanisms but Display Different Acyl-CoA Specificities. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 7236–7245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemonidis, K.; Gorleku, O.A.; Sanchez-Perez, M.C.; Grefen, C.; Chamberlain, L.H.; Brennwald, P.J. The GolgiS-acylation machinery comprises zDHHC enzymes with major differences in substrate affinity andS-acylation activity. Mol. Biol. Cell 2014, 25, 3870–3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Chen, X.; Sun, Y.; Jiang, L.; Xia, Z.; Ye, K.; Jiang, H.; Yang, B.; Ying, M.; Cao, J.; et al. ZDHHC12-mediated claudin-3 S-palmitoylation determines ovarian cancer progression. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2020, 10, 1426–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.-M.; Chen, Y.-J.; Shen, L.-F.; Haddad, A.N.S.; Song, I.W.; Chen, L.-Y.; Chen, Y.-J.; Wu, J.-Y.; Yen, J.J.Y.; Chen, Y.-T. Cyclic Alopecia and Abnormal Epidermal Cornification in Zdhhc13-Deficient Mice Reveal the Importance of Palmitoylation in Hair and Skin Differentiation. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2015, 135, 2603–2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhu, B.; Yin, C.; Liu, W.; Han, C.; Chen, B.; Liu, T.; Li, X.; Chen, X.; Li, C.; et al. Palmitoylation-dependent activation of MC1R prevents melanomagenesis. Nature 2017, 549, 399–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.S.; Martina, J.A.; Hammer, J.A. Melanoregulin is stably targeted to the melanosome membrane by palmitoylation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 426, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujic, I.; Sanlorenzo, M.; Esteve-Puig, R.; Vujic, M.; Kwong, A.; Tsumura, A.; Murphy, R.; Moy, A.; Posch, C.; Monshi, B.; et al. Acyl protein thioesterase 1 and 2 (APT-1, APT-2) inhibitors palmostatin B, ML348 and ML349 have different effects on NRAS mutant melanoma cells. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 7297–7306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, T.; Yang, X.; Lee, H.; Garst, E.H.; Valencia, E.; Chandran, K.; Im, W.; Hang, H.C. S-Palmitoylation and Sterol Interactions Mediate Antiviral Specificity of IFITMs. ACS Chem. Biol. 2022, 17, 2109–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garst, E.H.; Lee, H.; Das, T.; Bhattacharya, S.; Percher, A.; Wiewiora, R.; Witte, I.P.; Li, Y.; Peng, T.; Im, W.; et al. Site-Specific Lipidation Enhances IFITM3 Membrane Interactions and Antiviral Activity. ACS Chem. Biol. 2021, 16, 844–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Hou, D.; Chen, W.; Lu, X.; Komaniecki, G.P.; Xu, Y.; Yu, T.; Zhang, S.M.; Linder, M.E.; Lin, H. MAVS Cys508 palmitoylation promotes its aggregation on the mitochondrial outer membrane and antiviral innate immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2403392121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Cai, J.; Zhao, X.; Ma, L.; Zeng, P.; Zhou, L.; Liu, Y.; Yang, S.; Cai, Z.; Zhang, S.; et al. Palmitoylation prevents sustained inflammation by limiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation through chaperone-mediated autophagy. Mol. Cell 2023, 83, 281–297.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, C.J.; Mecklenburg, L.; Jaubert, J.; Martinez-Santamaria, L.; Iritani, B.M.; Espejo, A.; Napoli, E.; Song, G.; del Río, M.; DiGiovanni, J.; et al. Increased Susceptibility to Skin Carcinogenesis Associated with a Spontaneous Mouse Mutation in the Palmitoyl Transferase Zdhhc13 Gene. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2015, 135, 3133–3143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Liu, J.; Min, X.; Zeng, W.; Shan, B.; Zhang, M.; He, Z.; Zhang, Y.; He, K.; Yuan, J.; et al. Reduction of DHHC5-mediated beclin 1 S-palmitoylation underlies autophagy decline in aging. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2024, 31, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Yao, J.; Liu, L.; Luo, Y.; Yang, A. Atg8–PE protein-based in vitro biochemical approaches to autophagy studies. Autophagy 2022, 18, 2020–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, F.; Wang, Y.; Yao, J.; Mei, L.; Huang, X.; Kong, H.; Chen, J.; Chen, X.; Liu, L.; Wang, Z.; et al. ZDHHC7-mediated S-palmitoylation of ATG16L1 facilitates LC3 lipidation and autophagosome formation. Autophagy 2024, 20, 2719–2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.W.; Kim, D.H.; Park, K.S.; Kim, M.K.; Park, Y.M.; Muallem, S.; So, I.; Kim, H.J. Palmitoylation controls trafficking of the intracellular Ca2+ channel MCOLN3/TRPML3 to regulate autophagy. Autophagy 2018, 15, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, C.; Sadhukhan, T.; Bagh, M.B.; Appu, A.P.; Chandra, G.; Mondal, A.; Saha, A.; Mukherjee, A.B. Cln1-mutations suppress Rab7-RILP interaction and impair autophagy contributing to neuropathology in a mouse model of infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2020, 43, 1082–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Shen, N.; Liu, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhu, R.; Jiang, H.; Wu, X.; Wei, Y.; Tang, J. AMPKα1-mediated ZDHHC8 phosphorylation promotes the palmitoylation of SLC7A11 to facilitate ferroptosis resistance in glioblastoma. Cancer Lett. 2024, 584, 216619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Li, Z.; Jin, B.; Ye, W.; Wang, L.; Zhang, S.; Zheng, J.; Lin, Z.; Chen, B.; Liu, F.; et al. Loss of LncRNA DUXAP8 synergistically enhanced sorafenib induced ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma via SLC7A11 de-palmitoylation. Clin. Transl. Med. 2023, 13, e1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Hou, J.; Zhou, G.; Wang, H.; Wu, Z. zDHHC3-mediated S-palmitoylation of SLC9A2 regulates apoptosis in kidney clear cell carcinoma. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 150, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balasubramanian, A.; Hsu, A.Y.; Ghimire, L.; Tahir, M.; Devant, P.; Fontana, P.; Du, G.; Liu, X.; Fabin, D.; Kambara, H.; et al. The palmitoylation of gasdermin D directs its membrane translocation and pore formation during pyroptosis. Sci. Immunol. 2024, 9, eadn1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Li, S.; Wang, C.; Vidmar, K.J.; Bracey, S.; Li, L.; Willard, B.; Miyagi, M.; Lan, T.; Dickinson, B.C.; et al. Palmitoylation at a conserved cysteine residue facilitates gasdermin D-mediated pyroptosis and cytokine release. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2400883121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, G.; Healy, L.B.; David, L.; Walker, C.; El-Baba, T.J.; Lutomski, C.A.; Goh, B.; Gu, B.; Pi, X.; Devant, P.; et al. ROS-dependent S-palmitoylation activates cleaved and intact gasdermin D. Nature 2024, 630, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.; Shan, H.; Hou, S.; Fang, H.; Ma, M.; Chen, Z.; Tan, L.; Xu, D. A palmitoylation–depalmitoylation relay spatiotemporally controls GSDMD activation in pyroptosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2024, 26, 757–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Z.; Gu, J.; Li, B.O.; Yang, L. Inhibition of gasdermin D palmitoylation by disulfiram is crucial for the treatment of myocardial infarction. Transl. Res. 2024, 264, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Zhang, X.; Cai, X.; Li, N.; Zheng, H.; Tang, M.; Zhu, J.; Su, K.; Zhang, R.; Ye, N.; et al. NU6300 covalently reacts with cysteine-191 of gasdermin D to block its cleavage and palmitoylation. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadi9284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margheritis, E.; Kappelhoff, S.; Danial, J.; Gehle, N.; Kohl, W.; Kurre, R.; González Montoro, A.; Cosentino, K. Gasdermin D cysteine residues synergistically control its palmitoylation-mediated membrane targeting and assembly. EMBO J. 2024, 43, 4274–4297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Wang, M.R.; Ding, Y.; Lin, Y.; Xu, T.T.; He, X.X.; Li, P.Y. Lenvatinib promotes hepatocellular carcinoma pyroptosis by regulating GSDME palmitoylation. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2025, 26, 2532217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krysan, D.J.; Santiago-Tirado, F.H.; Peng, T.; Yang, M.; Hang, H.C.; Doering, T.L. A Single Protein S-acyl Transferase Acts through Diverse Substrates to Determine Cryptococcal Morphology, Stress Tolerance, and Pathogenic Outcome. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1004908. [Google Scholar]

- Nichols, C.B.; Ferreyra, J.; Ballou, E.R.; Alspaugh, J.A. Subcellular Localization Directs Signaling Specificity of the Cryptococcus neoformans Ras1 Protein. Eukaryot. Cell 2009, 8, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick, D.; Barth, S.; Macleod, K.F. Autophagy: Cellular and molecular mechanisms. J. Pathol. 2010, 221, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kihara, A.; Kabeya, Y.; Ohsumi, Y.; Yoshimori, T. Beclin–phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complex functions at the trans-Golgi network. EMBO Rep. 2001, 2, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broz, P.; Pelegrín, P.; Shao, F. The gasdermins, a protein family executing cell death and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 20, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.Y.; Li, S.T.; Lin, S.C.; Kao, C.H.; Hong, C.H.; Lee, C.H.; Yang, L.T. Gasdermin A Is Required for Epidermal Cornification during Skin Barrier Regeneration and in an Atopic Dermatitis-Like Model. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2023, 143, 1735–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, L.-F.; Chen, Y.-J.; Liu, K.-M.; Haddad, A.N.S.; Song, I.W.; Roan, H.-Y.; Chen, L.-Y.; Yen, J.J.Y.; Chen, Y.-J.; Wu, J.-Y.; et al. Role of S-Palmitoylation by ZDHHC13 in Mitochondrial function and Metabolism in Liver. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napoli, E.; Song, G.; Liu, S.; Espejo, A.; Perez, C.J.; Benavides, F.; Giulivi, C. Zdhhc13-dependent Drp1 S-palmitoylation impacts brain bioenergetics, anxiety, coordination and motor skills. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liu, J.; Yu, T.; Lu, F.; Miao, Q.; Meng, X.; Xiao, W.; Yang, H.; Zhang, X. ZDHHC9-mediated Bip/GRP78 S-palmitoylation inhibits unfolded protein response and promotes bladder cancer progression. Cancer Lett. 2024, 598, 217118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.; Xiong, W.; Kojic, L.; Cynader, M.S. Subunit-selective palmitoylation regulates the intracellular trafficking of AMPA receptor. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2009, 30, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnik, S.; Heybrock, S.; Saftig, P.; Damme, M. S-palmitoylation determines TMEM55B-dependent positioning of lysosomes. J. Cell Sci. 2022, 135, jcs258566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flannery, A.R.; Czibener, C.; Andrews, N.W. Palmitoylation-dependent association with CD63 targets the Ca2+ sensor synaptotagmin VII to lysosomes. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 191, 599–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Hua, F.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, S.; Wang, W.; Zhou, J.; Wang, W.; Liao, P.; Yan, Y.; et al. Loss of Optineurin Drives Cancer Immune Evasion via Palmitoylation-Dependent IFNGR1 Lysosomal Sorting and Degradation. Cancer Discov. 2021, 11, 1826–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Li, C.; He, F.; Song, T.; Brosseau, J.-P.; Wang, H.; Lu, H.; Fang, C.; Shi, H.; Lan, J.; et al. A peptidic inhibitor for PD-1 palmitoylation targets its expression and functions. RSC Chem. Biol. 2021, 2, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feichtinger, R.G.; Sperl, W.; Bauer, J.W.; Kofler, B. Mitochondrial dysfunction: A neglected component of skin diseases. Exp. Dermatol. 2014, 23, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, M.; Chen, J.; Chen, J.; Shen, X.; Ni, J. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in skin aging induced by UVB. Exp. Dermatol. 2023, 33, e14956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu El-Hamd, M.; Abdel-Hamid, S.; Hamdy, A.-t.; Abdelhamed, A. Increased serum ATG5 as a marker of autophagy in psoriasis vulgaris patients: A cross-sectional study. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2024, 316, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davda, D.; El Azzouny, M.A.; Tom, C.T.; Hernandez, J.L.; Majmudar, J.D.; Kennedy, R.T.; Martin, B.R. Profiling Targets of the Irreversible Palmitoylation Inhibitor 2-Bromopalmitate. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013, 8, 1912–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Yuan, Q.; Wang, S.; Yu, T.; Qi, X. Role of S-palmitoylation in digestive system diseases. Cell Death Discov. 2025, 11, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaun, C.; Takizawa, H.; Galindo, A.; Munro, K.R.; McLellan, J.; Sugimoto, I.; Okino, T.; Tomkinson, N.C.O.; Chamberlain, L.H. Development of a novel high-throughput screen for the identification of new inhibitors of protein S-acylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 102469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Wang, C.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, S.; Liu, X.; Yang, X.; Liu, W. Bioactive fatty acid analog-derived hybrid nanoparticles confer antibody-independent chemo-immunotherapy against carcinoma. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2023, 21, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Dermatologic Phenotypes | Enzymes | Substrates and Sites | Change of S-Palmitoylation | Pathogenic Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin barrier | zDHHC13 [14,28] | Not identified [14,28] | Up | Promote skin barrier development |

| zDHHC12 [30] | Claudin-3, Cys181/182/184 [30] | Up | Promote skin barrier integrity | |

| Melanogenesis | zDHHC13 [32] | MC1R, Cys315 [32] | Up | Increase pigmentation, prevent melanoma occurrence |

| zDHHC2,3 and 5 [15] | Tyrosinase, Cys500 [15] | Up | Diminish melanin content | |

| Not identified | Melanoregulin, N-terminus [29] | Up | Stabilize melanoregulin in the melanosome membrane | |

| Alopecia | zDHHC13 [28] | Cornifelin, Cys58/59/60/95 [28] | Down | Cyclic alopecia |

| Atopic dermatitis | zDHHC13 [11] | Not identified | Down | Atopic dermatitis |

| Psoriasis | zDHHC2 [12] | Not identified | Up | Promote psoriasis progression |

| Skin inflammatory | zDHHC12 [36] | NLRP3, Cys 844 [36] | Up | Promote NLRP3 degradation |

| zDHHC7 [31] | NLRP3, Cys 126 [31] | Up | Promote inflammasome assembly | |

| zDHHC5 [33] | NLRP3, Cys837/838 [33] | Up | Promote inflammasome activation | |

| zDHHC5 [34,35] | NOD1, Cys558/567/952 [34,35] | Up | Enhance NOD1’s stability | |

| zDHHC5 [34,35] | NOD2, Cys 395/1033 [34,35] | Up | Enhance NOD2’s stability | |

| Carcinogenesis | zDHHC13 [37] | Not identified | Down | Inhibit malignant progression of papillomas |

| Physiological Processes | Enzymes | Substrate and Sites | Change of Palmitoylation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Differentiation | zDHHC13 [28] | Not identified | Up |

| Autophagy | zDHHC5 [58] | Beclin1 Cys137 [58] | Up |

| zDHHC5 [40] | ATG16L1 Cys153 [40] | Up | |

| zDHHC1/11 [41] | MCOLN3/TRPML3, Cys549/550/551 [41] | Up Up | |

| PPT1 [42] | Rab7, Cys205/207 [42] | Up | |

| Pyroptosis | zDHHC5 [47,48,49,50,59] | GSDMD, Cys 191/192 [47,48,49,50,59] | Up |

| zDHHC7 [47,48,49,50,59] | GSDMD, Cys 191/192 [47,48,49,50,59] | Up | |

| zDHHC9 [47,48,49,50,59] | GSDMD, Cys 191/192 [47,48,49,50,59] | Up | |

| zDHHC14 [47,48,49,50,59] | GSDMD, Cys 191/192 [47,48,49,50,59] | Up | |

| Not identified | GSDMD, Cys 39,57 [52] | Up | |

| zDHHC 2/7/11/15 [53] | GSDME [53] | Up | |

| Ferroptosis | DUXAP8 [44] | SCL7A11, Cys414 [44] | Up |

| zDHHC8 [60] | SLC7A11, Cys327 [60] | Up | |

| Apoptosis | zDHHC3 [45] | SLC9A2 [45] | Up |

| Organelles | Enzymes | Substrate and Sites | Direction of Palmitoylation Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mitochondria | zDHHC13 [61,69] | Drp1 [61] | UP |

| Endoplasmic reticulum | zDHHC9 [70] | BIP, Cys420 [70] | UP |

| Lysosome | Not identified | TMEM55B [71] | UP |

| Not identified | Syt VII [65] | UP | |

| Not identified | IFNGR1, Cys122 [66] | UP | |

| Not identified | PD-1 [67] | UP |

| Compound | Chemical Structure | Mechanism of S-Palmitoylation Inhibition | Selectivity |

|---|---|---|---|

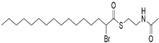

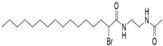

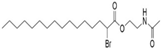

| 2-bromopalmitate (2-BP) |  | Forms a covalent bond with the cysteine in the DHHC motif on its α-position carbon [68] | Without |

| MY-D-2 (2-BP analog) |  | An electron-deficient ester increases reactivity of the α-position carbon [72] | Weak inhibiting potency against zDHHC 3/7 |

| MY-D-3 (2-BP analog) |  | An electron-rich amide decreases reactivity of the α-position carbon [72] | Without obvious inhibiting potency |

| MY-D-4 (2-BP analog) |  | An electron-deficient thioester increases reactivity of the α-position carbon [72] | Strong inhibiting potency against zDHHC 3/7 |

| MY-D-5 (MY-D-4 analog) |  | An additional electron-rich amide is added to decrease reactivity of the α-position carbon on MY-D-4 [72] | Weak inhibiting potency against zDHHC 3/7 |

| MY-D-6 (MY-D-4 analog) |  | An additional electron-deficient ester is added to increase reactivity of the α-position carbon on MY-D-4 [72] | Weak inhibiting potency against zDHHC 3/7 |

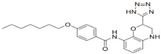

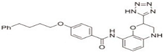

| Tetrazole-containing compound 1 (TTZ-1) |  | Inhibiting zDHHC 2 autoacylation [73] | zDHHC 2 |

| Tetrazole-containing compound 2 (TTZ-2) |  | Inhibiting zDHHC 2 autoacylation [73] | zDHHC 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Feng, Y.; Wu, J.; Tang, H.; Liu, S.; Jia, H.; Liang, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, L.; Li, L.; Lei, X. Protein S-Palmitoylation as Potential Therapeutic Target for Dermatoses. Biomolecules 2026, 16, 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010053

Feng Y, Wu J, Tang H, Liu S, Jia H, Liang Y, Li Z, Li L, Li L, Lei X. Protein S-Palmitoylation as Potential Therapeutic Target for Dermatoses. Biomolecules. 2026; 16(1):53. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010053

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeng, Yanhai, Jianxin Wu, Hui Tang, Shunying Liu, Honglin Jia, Yi Liang, Zhenglin Li, Lingbo Li, Lingfei Li, and Xia Lei. 2026. "Protein S-Palmitoylation as Potential Therapeutic Target for Dermatoses" Biomolecules 16, no. 1: 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010053

APA StyleFeng, Y., Wu, J., Tang, H., Liu, S., Jia, H., Liang, Y., Li, Z., Li, L., Li, L., & Lei, X. (2026). Protein S-Palmitoylation as Potential Therapeutic Target for Dermatoses. Biomolecules, 16(1), 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010053