Antifungal Activity of Surfactin Against Cytospora chrysosperma

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Strains

2.2. Preparation of Fresh Mycelia

2.3. Antifungal Activity of Surfactin Against Cytospora chrysosperma

2.4. Effect of Surfactin on the Morphology of C. chrysosperma

2.4.1. Optical Microscope Observation

2.4.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Observation

2.4.3. Transmission Electron Microscopy Observation

2.5. Effect of Surfactin on Cell Membrane Integrity of C. chrysosperma

2.6. Effect of Surfactin on Oxidative Stress in C. chrysosperma

2.7. Mitochondrial Membrane of C. chrysosperma

2.8. Effect of Surfactin on Energy Metabolism of C. chrysosperma

2.9. Observation of Autophagy in C. chrysosperma Treated with Surfactin

2.10. Effect of Surfactin on Transcriptome of C. chrysosperma

2.11. RT-qPCR Analysis

2.12. Molecular Docking

2.13. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

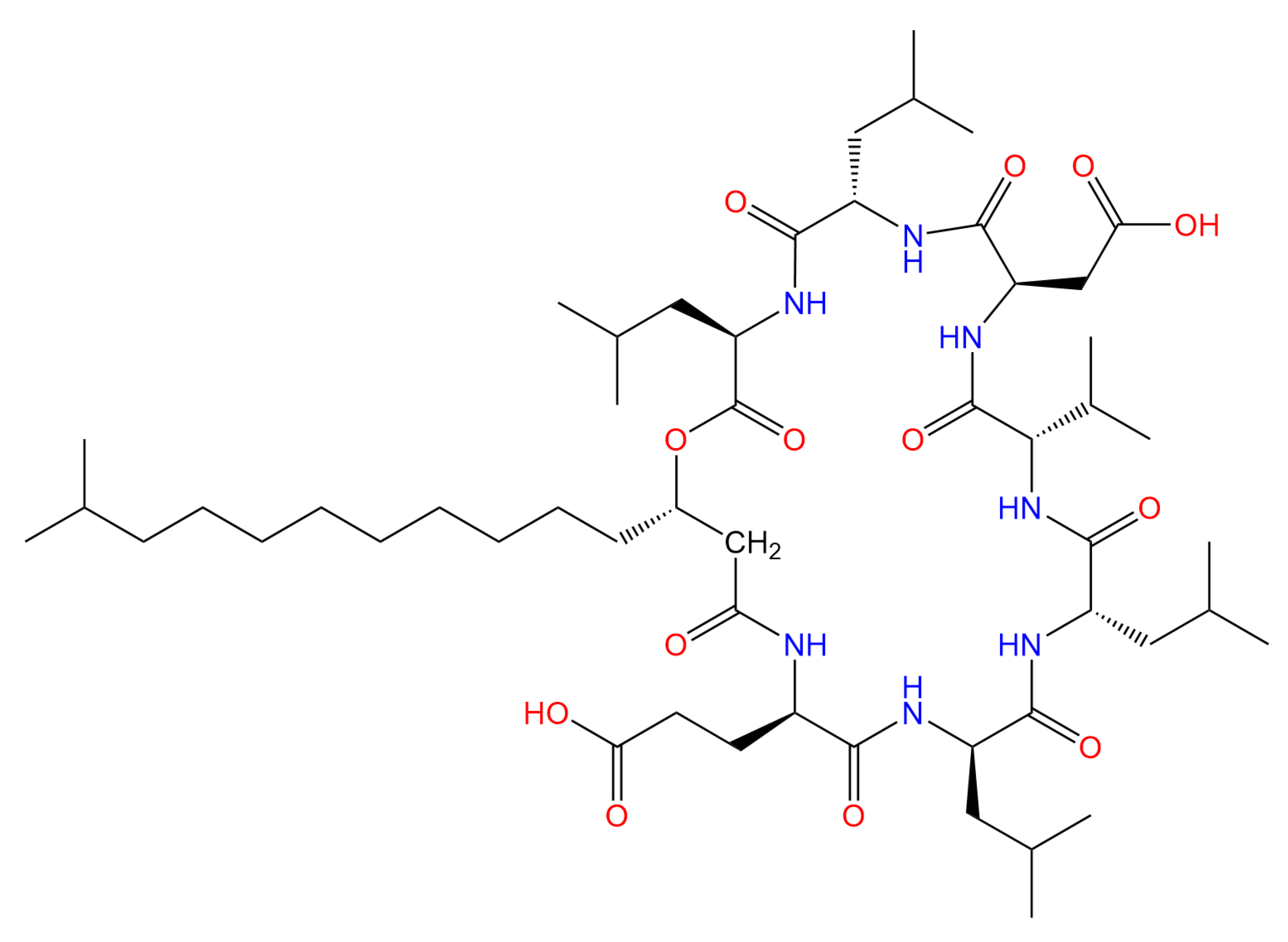

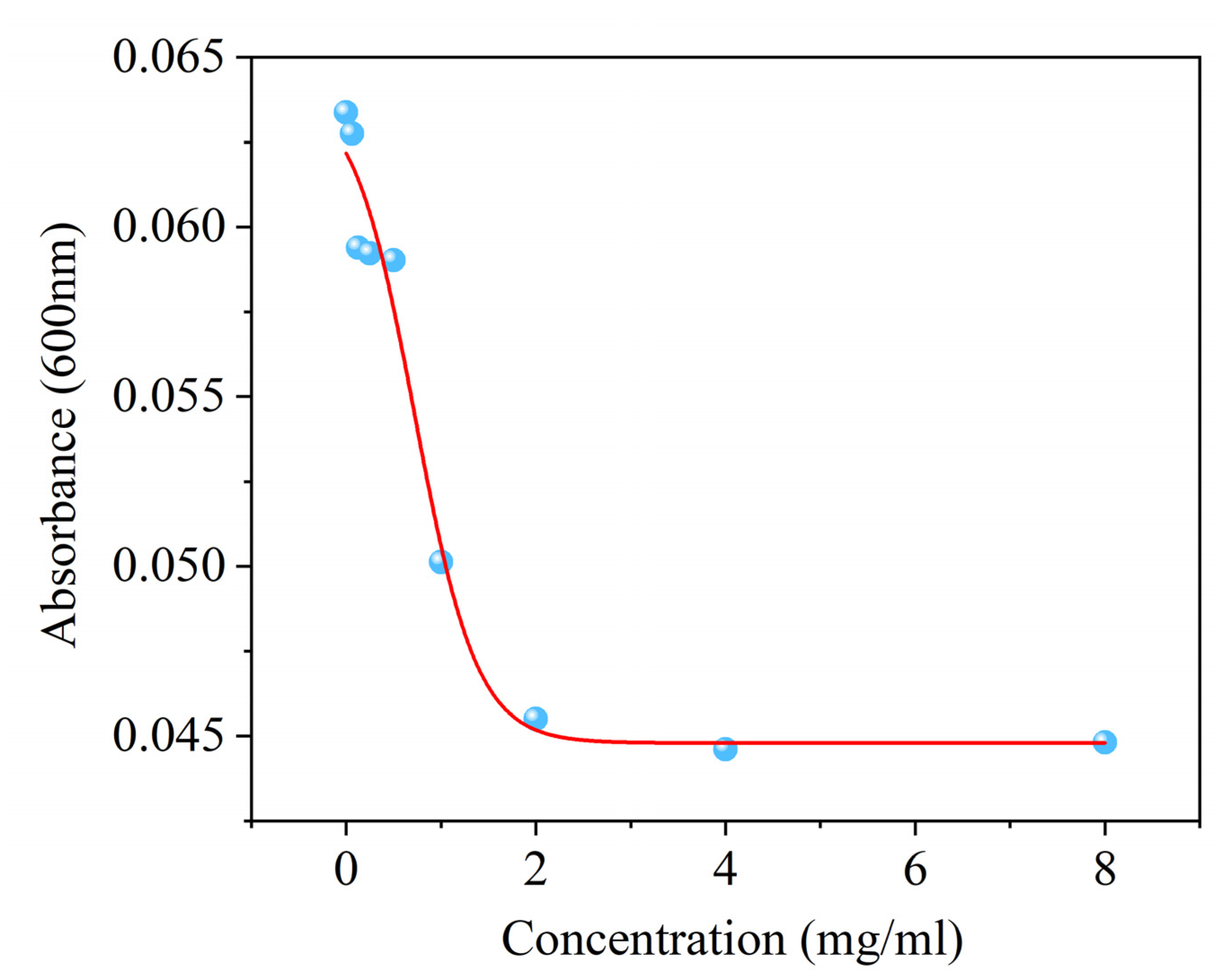

3.1. Antifungal Activity of Surfactin Against C. chrysosperma

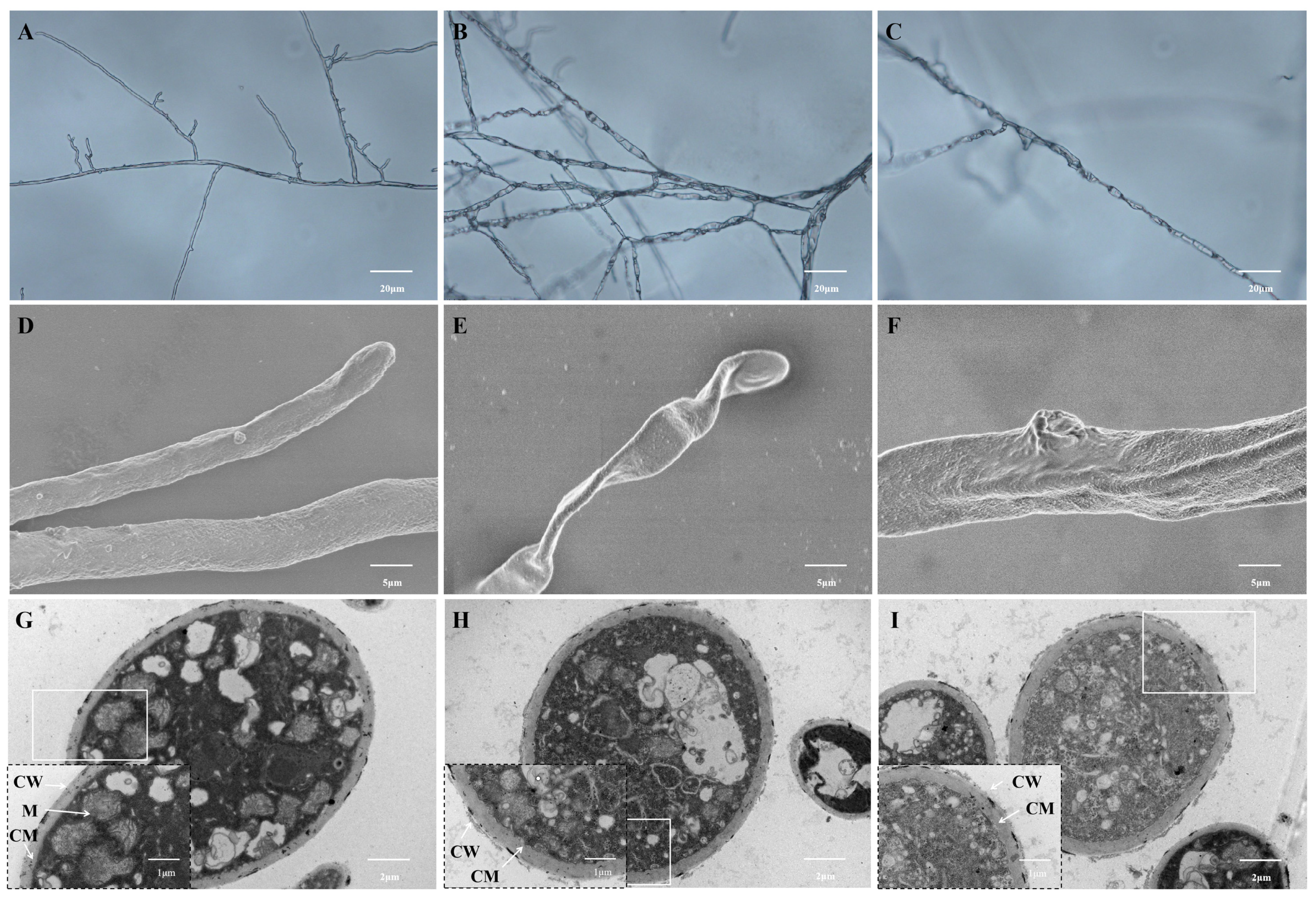

3.2. Effect of Surfactin on the Morphology of C. chrysosperma

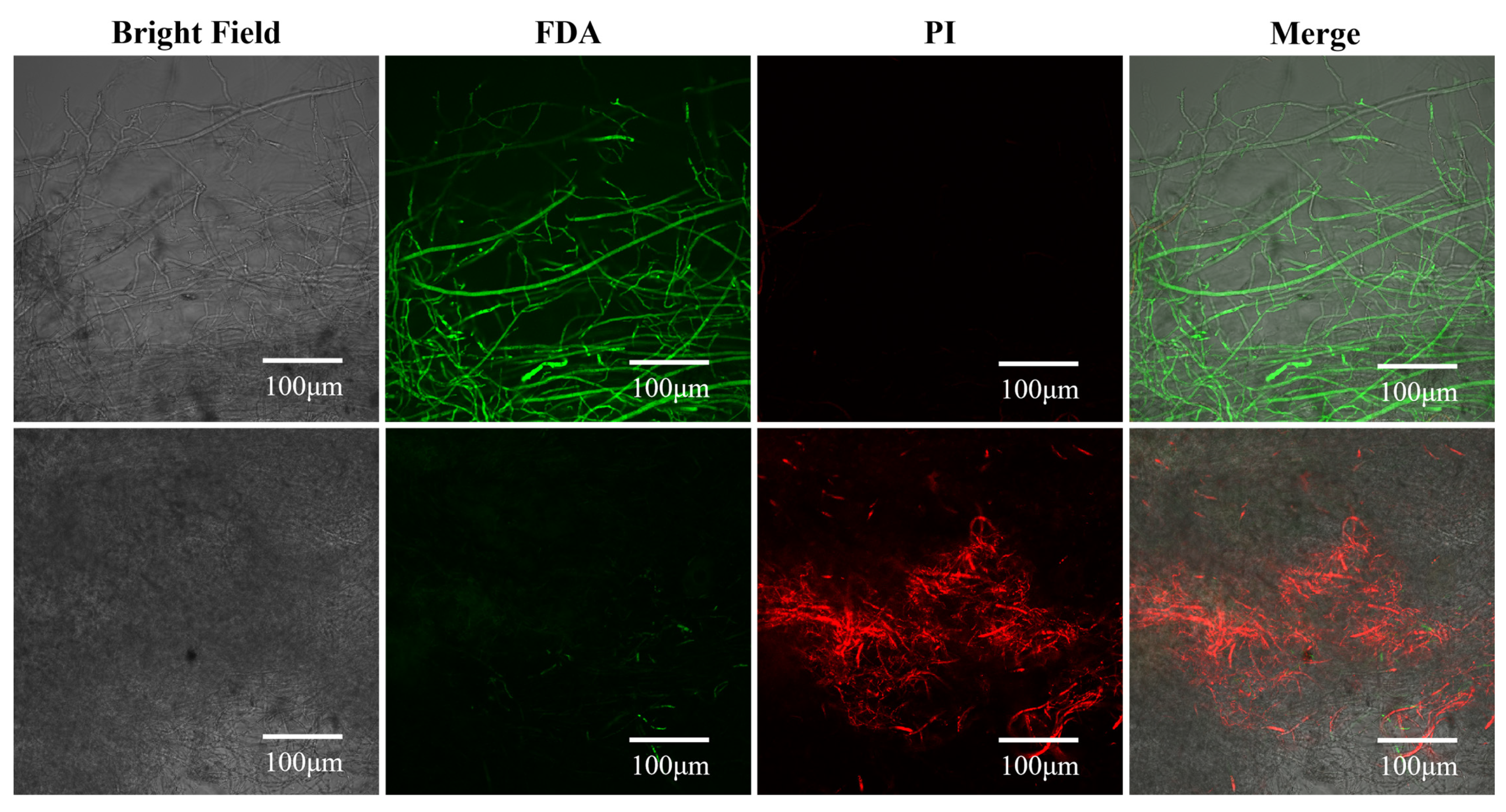

3.3. Effects of Surfactin on Cell Membrane Integrity and Viability

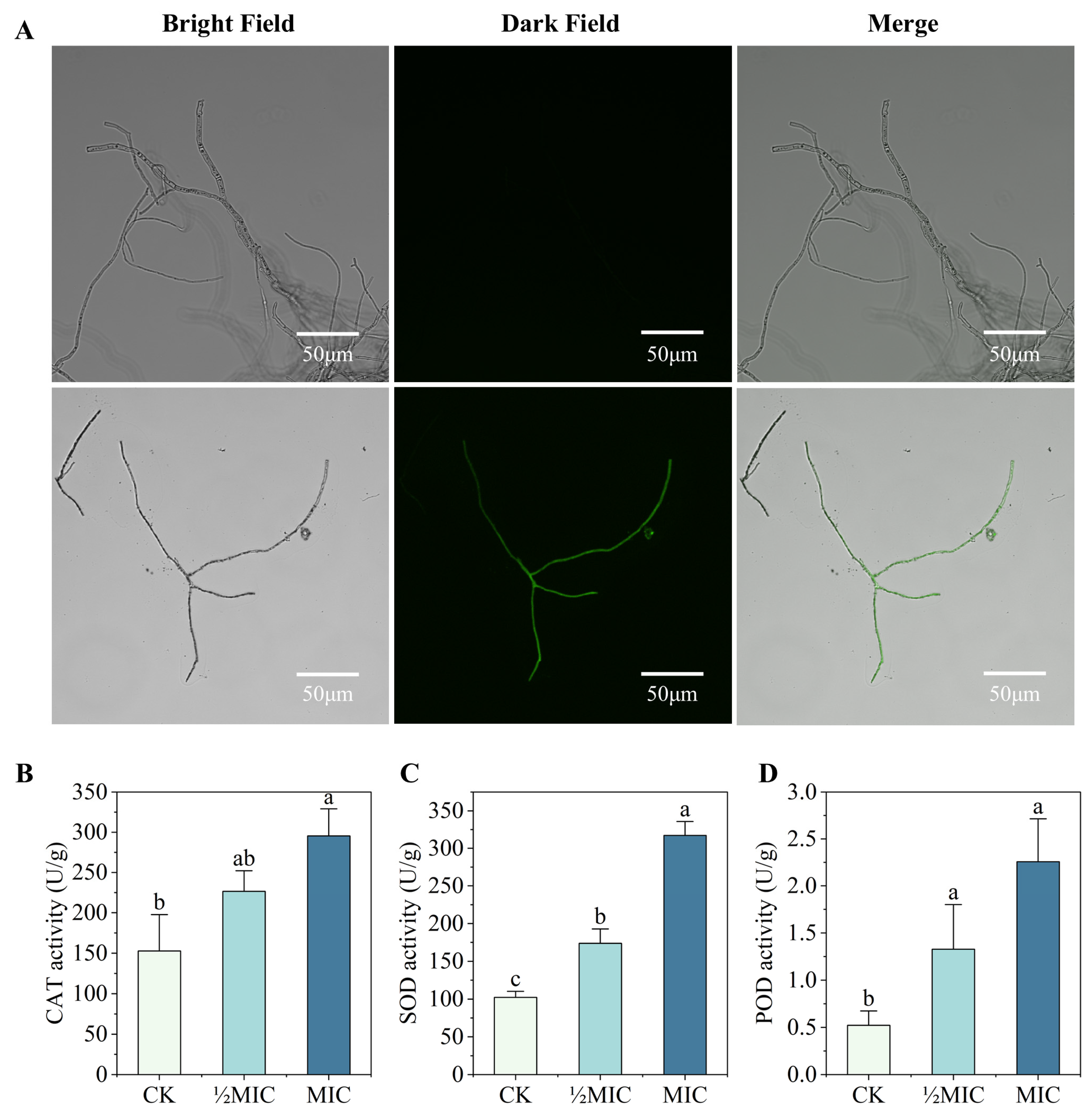

3.4. Effects of Surfactin on Oxidative Stress in C. chrysosperma

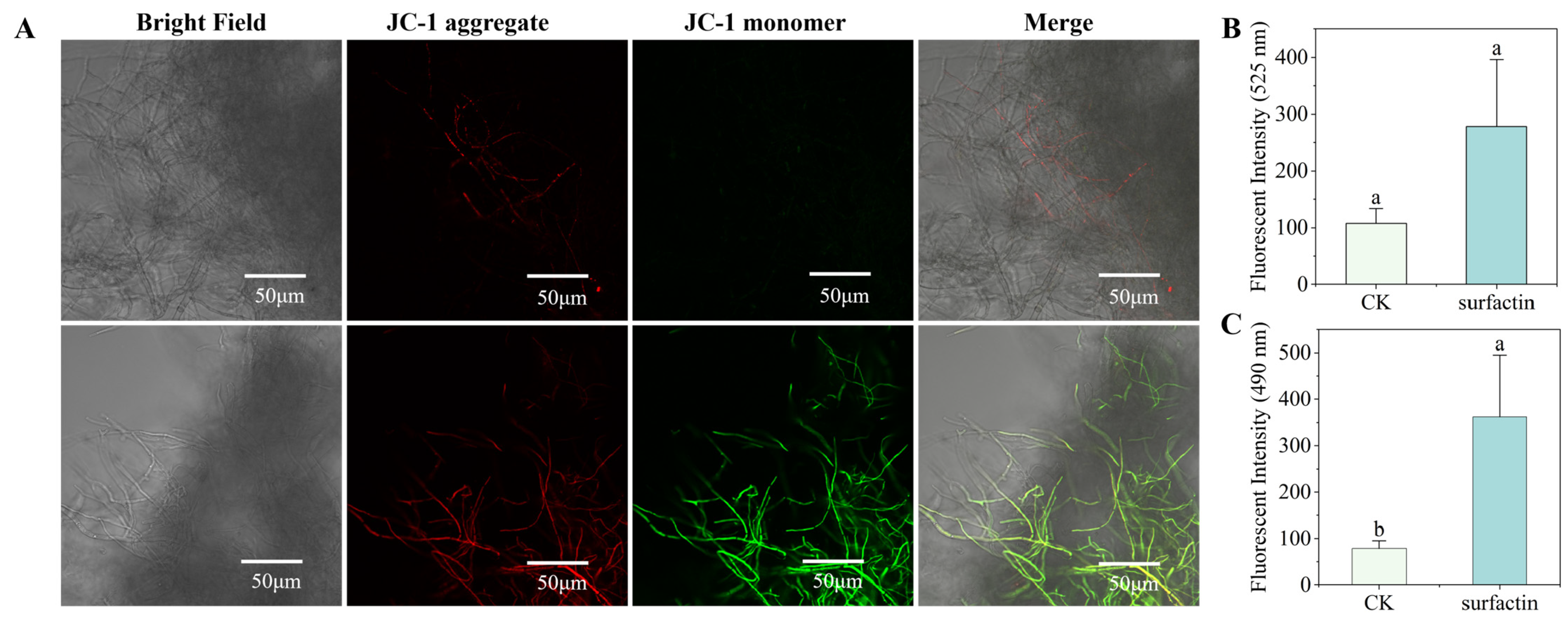

3.5. Effect of Surfactin on Mitochondrial Membrane Potential

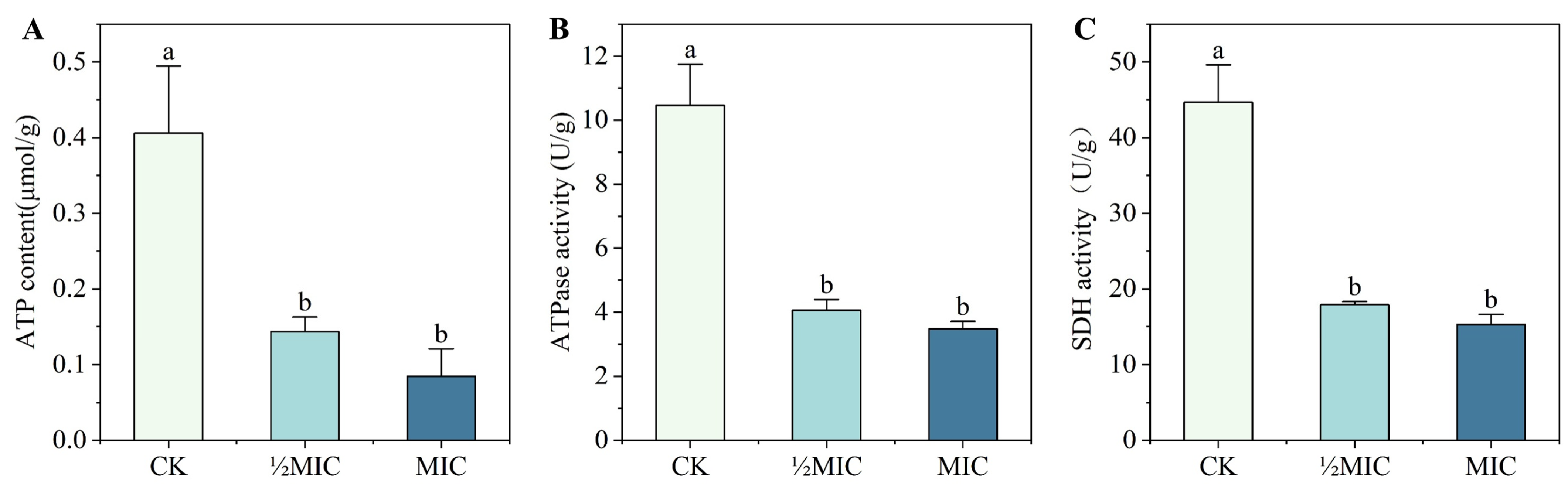

3.6. Effects of Surfactin on Energy Metabolism

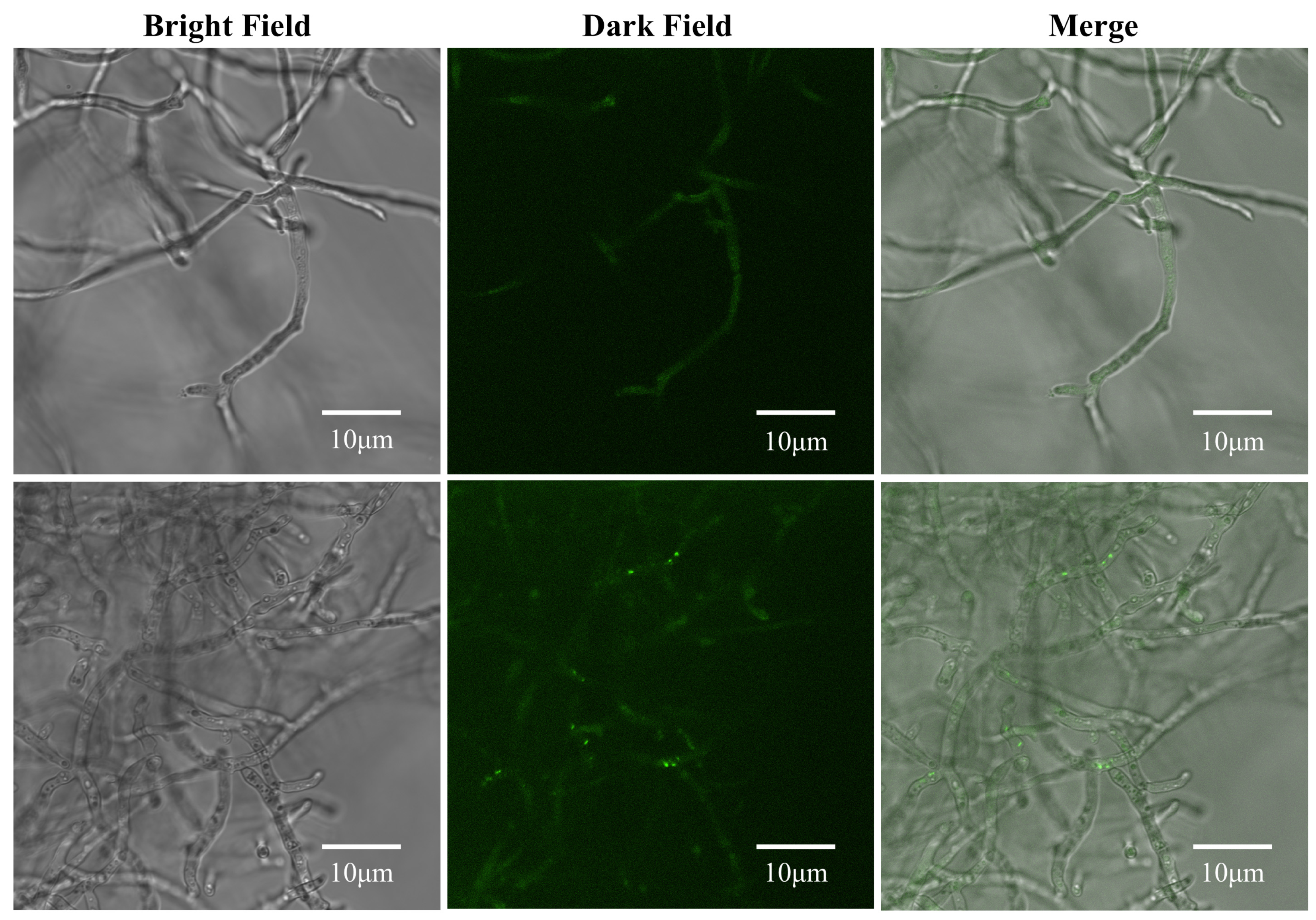

3.7. Surfactin Induces Autophagy in C. chrysosperma

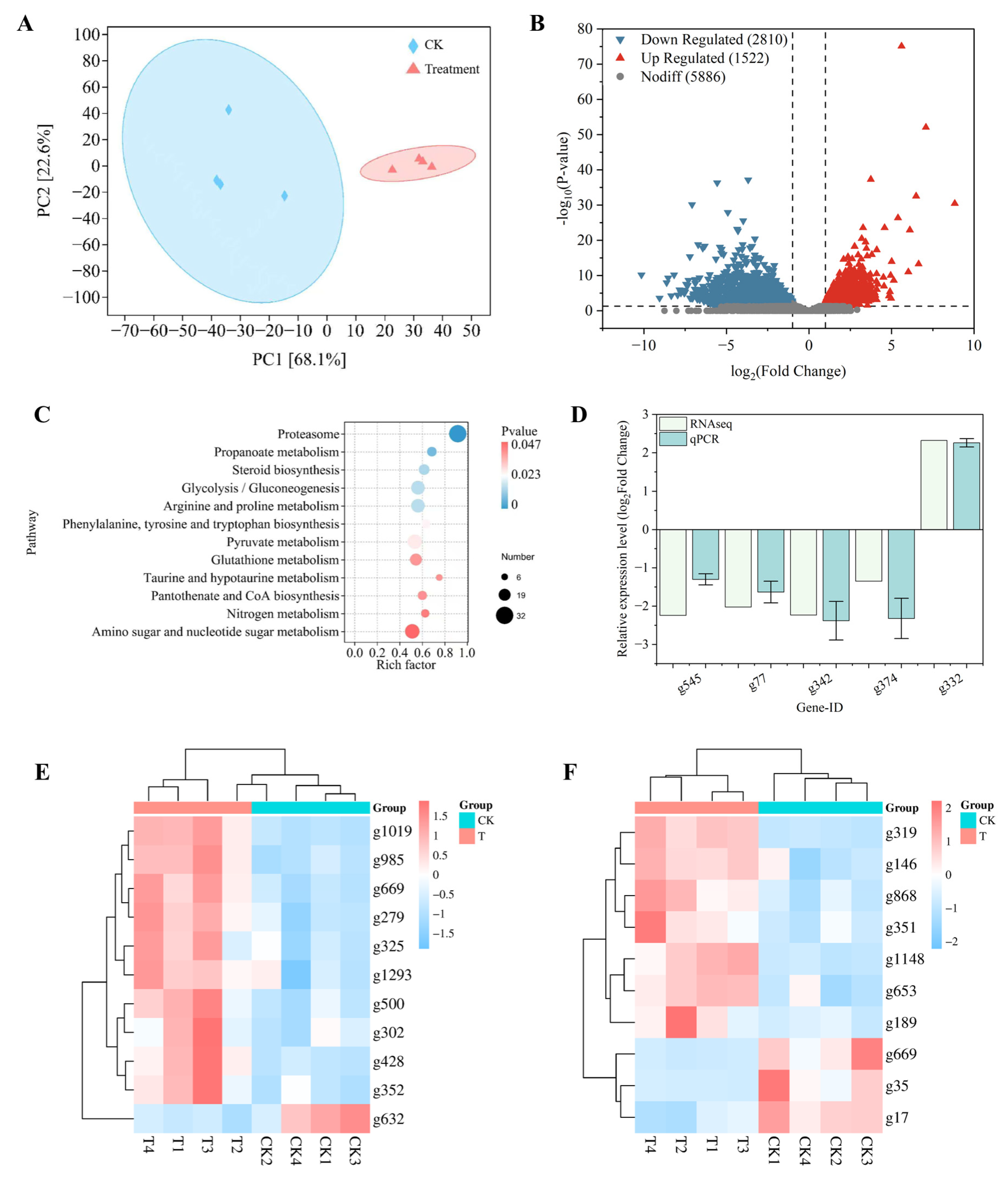

3.8. Transcriptomic Response of C. chrysosperma to Surfactin

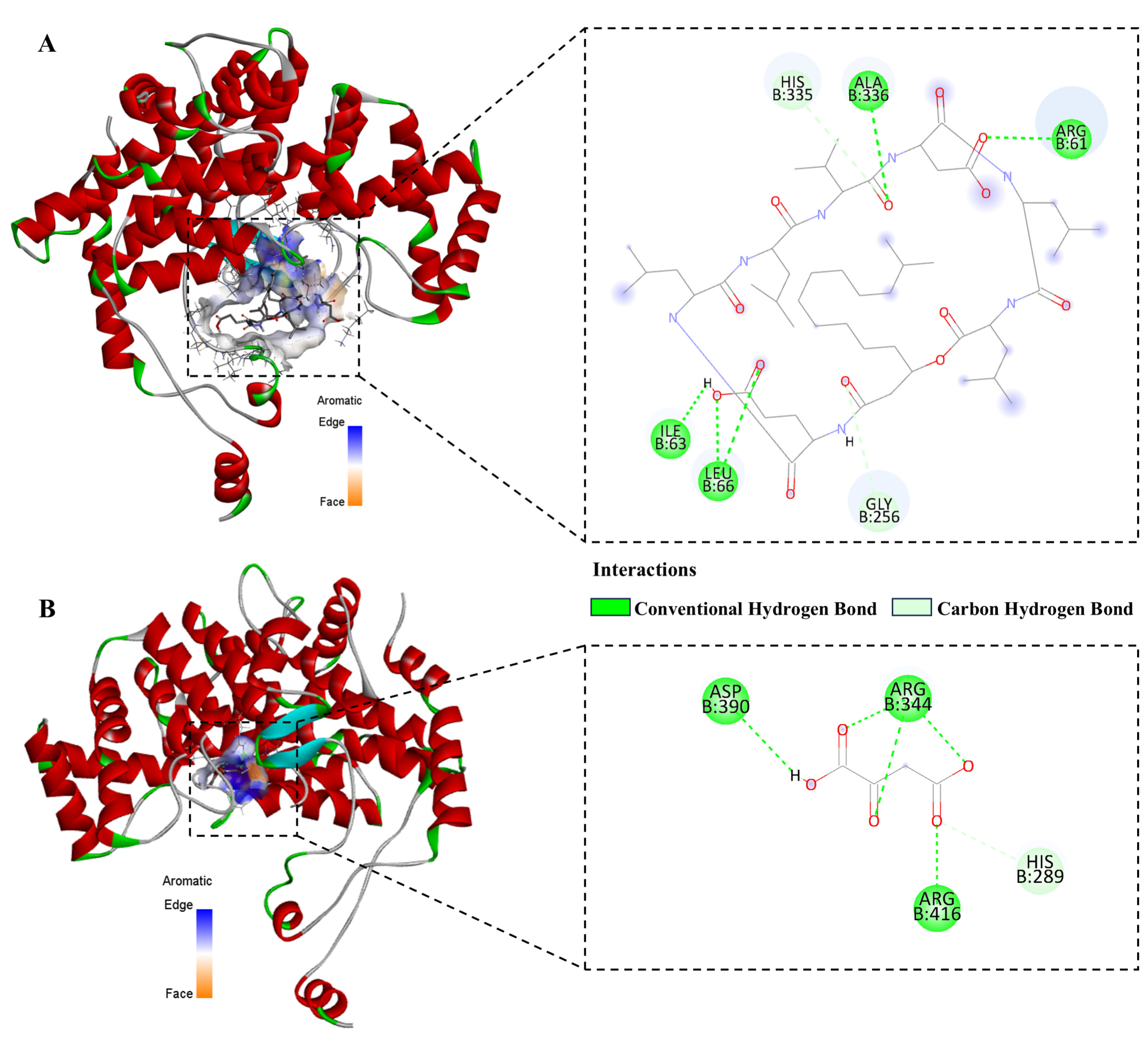

3.9. Molecular Docking

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, S.; Zhang, R.; Sun, D.; Zhu, T.; Chen, X.; Chen, X.; Chen, X. First Report of Cytospora tritici Causing Branch Canker on English Walnut in China. J. Plant Pathol. 2023, 105, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, S.S.; Wang, Z.; Yan, C.C.; Hao, H.T.; Wang, L.; Feng, H.Z. Identification of Fungal Species Associated with Apple Canker in Tarim Basin, China. Plant Dis. 2023, 107, 1284–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Q.; Zhang, H.; Bao, L.; Song, Z.; Liu, C.; Jiang, Z.; Zheng, Y. NCs-Delivered Pesticides: A Promising Candidate in Smart Agriculture. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Huang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Si, H.; Luo, H.; Chen, S.; Wang, Z.; He, H.; Liao, S. Synthesis, Antifungal Activity and Action Mechanism of Novel Citral Amide Derivatives Against Rhizoctonia solani. Pest Manag. Sci. 2024, 80, 4482–4494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.; Wang, C.; Song, X.; Ding, X.; Wu, L.; Wu, H.; Gao, X.; Borriss, R. Bacillus velezensis FZB42 in 2018: The Gram-Positive Model Strain for Plant Growth Promotion and Biocontrol. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J.; Borriss, R.; Sun, K.; Zhang, R.; Chen, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y. Research Advances in the Identification of Regulatory Mechanisms of Surfactin Production by Bacillus: A Review. Microb. Cell Fact. 2024, 23, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelli, F.; Jardak, M.; Elloumi, J.; Stien, D.; Cherif, S.; Mnif, S.; Aifa, S. Antibacterial, anti-adherent and cytotoxic activities of surfactin(s) from a lipolytic strain Bacillus safensis F4. Biodegradation 2019, 30, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, A.; Hassan, M.N.; Imran, M.; Iqbal, M.; Majeed, S.; Brader, G.; Sessitsch, A.; Hafeez, F.Y. Biocontrol Activity of Surfactin A Purified from Bacillus NH-100 and NH-217 Against Rice Bakanae Disease. Microbiol. Res. 2018, 209, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandin, C.; Darsonval, M.; Mayeur, C.; Le Coq, D.; Aymerich, S.; Briandet, R. Biofilm Formation and Synthesis of Antimicrobial Compounds by the Biocontrol Agent Bacillus velezensis QST713 in an Agaricus bisporus Compost Micromodel. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 85, e00327-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Li, Q.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, N.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, R. Responses of Beneficial Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SQR9 to Different Soilborne Fungal Pathogens Through the Alteration of Antifungal Compounds Production. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xu, X.-X.; Sun, Y.-X.; Xin, Q.-H.; Lv, Y.-Y.; Hu, Y.-S.; Bian, K. Surfactin Inhibits Fusarium graminearum by Accumulating Intracellular ROS and Inducing Apoptosis Mechanisms. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 39, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, S.; McDougal, R.; Clearwater, M.J.; Williams, N.; Scott, P. Development of a high throughput optical density assay to determine fungicide sensitivity of oomycetes. J. Microbiol. Methods 2018, 154, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, J.M. Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2001, 48, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Liu, S.; Liao, X. Effects and Inhibition Mechanism of Phenazine-1-Carboxamide on the Mycelial Morphology and Ultrastructure of Rhizoctonia solani. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2018, 147, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.Q.; Zhang, X.Y.; Dhanasekaran, S.R.; Godana, E.A.; Yang, Q.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, H. Transcriptome Analysis of Postharvest Pear (Pyrus pyrifolia Nakai) in Response to Penicillium expansum Infection. Sci. Hortic. 2021, 288, 110361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talpan, D.; Salla, S.; Seidelmann, N.; Walter, P.; Fuest, M. Antifibrotic Effects of Caffeine, Curcumin and Pirfenidone in Primary Human Keratocytes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, W.Y.; Zhu, X.M.; Zhang, S.B.; Lv, Y.-Y.; Zhai, H.-C.; Wei, S.; Ma, P.-A.; Hu, Y.-S. Antifungal Effects of Carvacrol, the Main Volatile Compound in Origanum vulgare L. Essential Oil, Against Aspergillus flavus in Postharvest Wheat. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2024, 410, 110514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perelman, A.; Wachtel, C.; Cohen, M.; Haupt, S.; Shapiro, H.; Tzur, A. JC-1: Alternative Excitation Wavelengths Facilitate Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Cytometry. Cell Death Dis. 2012, 3, e430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.F.; Yang, C.J.; Shang, X.F.; Zhao, Z.-M.; Liu, Y.-Q.; Zhou, R.; Liu, H.; Wu, T.-L.; Zhao, W.-B.; Wang, Y.-L.; et al. Bioassay-Guided Isolation of Two Antifungal Compounds from Magnolia officinalis, and the Mechanism of Action of Honokiol. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2020, 170, 104705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhang, W.; Lv, Z.; Shi, L.; Zhang, K.; Ge, B. Induced Defense Response in Soybean to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum Using Wuyiencin from Streptomyces albulus CK-15. Plant Dis. 2023, 107, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisnovsky, S.; Lei, E.K.; Jean, S.R.; Kelley, S.O. Mitochondrial Chemical Biology: New Probes Elucidate the Secrets of the Powerhouse of the Cell. Cell Chem. Biol. 2016, 23, 917–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuster, M.; Kilaru, S.; Steinberg, G. Azoles Activate Type I and Type II Programmed Cell Death Pathways in Crop Pathogenic Fungi. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, H.F.; Sun, T.-T.; Tong, X.-Y.; Ren, J.; Zhang, Y.-H.; Shaw, P.-C.; Luo, D.-Q.; Cao, F. Antifungal Activity and Mechanism of Chaetoglobosin D Against Alternaria alternata in Tomato Postharvest Storage. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2024, 214, 113014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, C.L.; Colombo, M.I. Assays to Assess Autophagy Induction and Fusion of Autophagic Vacuoles with a Degradative Compartment, Using Monodansylcadaverine (MDC) and DQ-BSA. Methods Enzymol. 2009, 452, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar, S.; Saravanan, V. Biosurfactants-Types, Sources and Applications. Res. J. Microbiol. 2015, 10, 181–192. Available online: https://scialert.net/abstract/?doi=jm.2015.181.192 (accessed on 15 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Mielich-Süss, B.; Lopez, D. Molecular Mechanisms Involved in Bacillus subtilis Biofilm Formation. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 17, 555–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, C.; Teruel, J.A.; Aranda, F.J.; Ortiz, A. Molecular Mechanism of Membrane Permeabilization by the Peptide Antibiotic Surfactin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2003, 1611, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.P.; Uhl, J.; Grosch, R.; Alquéres, S.; Pittroff, S.; Dietel, K.; Schmitt-Kopplin, P.; Borriss, R.; Hartmann, A. Cyclic Lipopeptides of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens subsp. plantarum Colonizing the Lettuce Rhizosphere Enhance Plant Defense Responses Toward the Bottom Rot Pathogen Rhizoctonia solani. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2015, 28, 984–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, N.; Velramar, B.; Velu, R.K. Investigation of Antifungal Activity of Surfactin Against Mycotoxigenic Phytopathogenic Fungus Fusarium moniliforme and Its Impact in Seed Germination and Mycotoxicosis. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2019, 155, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Zhao, S.; Wang, C. β-Carboline Alkaloids from Peganum harmala Inhibit Fusarium oxysporum from Codonopsis radix Through Damaging the Cell Membrane and Inducing ROS Accumulation. Pathogens 2022, 11, 1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, S.; Ihara, T.; Tamura, H.; Tanaka, S.; Ikeda, T.; Kajihara, H.; Dissanayake, C.; Abdel-Motaal, F.F.; El-Sayed, M.A. α-Tomatine, the Major Saponin in Tomato, Induces Programmed Cell Death Mediated by Reactive Oxygen Species in the Fungal Pathogen Fusarium oxysporum. FEBS Lett. 2007, 581, 3217–3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, P.; Roy, A.; Hess, D.; Ghosh, A.; Das, S. Deciphering the Mode of Action of a Mutant Allium sativum Leaf Agglutinin (mASAL), a Potent Antifungal Protein on Rhizoctonia solani. BMC Microbiol. 2015, 15, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rottenberg, H. The Reduction in the Mitochondrial Membrane Potential in Aging: The Role of the Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, S.; Chang, W.; Zhang, M.; Shi, H.; Lou, H. Chiloscyphenol A Derived from Chinese Liverworts Exerts Fungicidal Action by Eliciting Both Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Plasma Membrane Destruction. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Yang, X.; Zhao, J.; Zeeshan, M.; Wang, C.; Yang, D.; Han, X.; Zhang, G. Antifungal Activity and Potential Inhibition Mechanism of 4-(Diethylamino)salicylaldehyde Against Rhizoctonia solani. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2025, 212, 106444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, M.; Yang, X.; Bie, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, M.; Li, Y.; Shao, G.; Luo, J. Citrate Synthase Desuccinylation by SIRT5 Promotes Colon Cancer Cell Proliferation and Migration. Biol. Chem. 2020, 401, 1031–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Zhu, Y.; Mo, Y.; Gao, X.; Miao, M.; Yu, W. Acetylation of Citrate Synthase Inhibits Bombyx mori Nucleopolyhedrovirus Propagation by Affecting Energy Metabolism. Microb. Pathog. 2022, 173, 105890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, M.; Stolp, Z.D.; Hardwick, J.M. Targeting Intrinsic Cell Death Pathways to Control Fungal Pathogens. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2019, 162, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xu, C.; Sun, Q.; Xu, J.; Chai, Y.; Berg, G.; Cernava, T.; Ma, Z.; Chen, Y. Post-Translational Regulation of Autophagy Is Involved in Intra-Microbiome Suppression of Fungal Pathogens. Microbiome 2021, 9, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struyfs, C.; Cools, T.L.; De Cremer, K.; Sampaio-Marques, B.; Ludovico, P.; Wasko, B.M.; Kaeberlein, M.; Cammue, B.P.A.; Thevissen, K. The Antifungal Plant Defensin HsAFP1 Induces Autophagy, Vacuolar Dysfunction and Cell Cycle Impairment in Yeast. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2020, 1862, 183255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twigg, M.S.; Baccile, N.; Banat, I.M.; Déziel, E.; Marchant, R.; Roelants, S.; Van Bogaert, I.N.A. Microbial Biosurfactant Research: Time to Improve the Rigour in the Reporting of Synthesis, Functional Characterization and Process Development. Microb. Biotechnol. 2021, 14, 147–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarubbo, L.A.; Maria da Gloria, C.S.; Durval, I.J.; Bezerra, K.G.; Ribeiro, B.G.; Silva, I.A.; Twigg, M.S.; Banat, I.M. Biosurfactants: Production, Properties, Applications, Trends, and General Perspectives. Biochem. Eng. J. 2022, 181, 108377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaikwad, S. Tapping Significance of Microbial Surfactants as a Biopesticide and Synthetic Pesticide Remediator: An Ecofriendly Approach for Maintaining the Environmental Sustainability. In Insecticides—Advances in Insect Control and Sustainable Pest Management; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badmus, S.O.; Amusa, H.K.; Oyehan, T.A.; Saleh, T.A. Environmental Risks and Toxicity of Surfactants: Overview of Analysis, Assessment, and Remediation Techniques. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 62085–62104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zhu, H.; Ozkan, H.E.; Bagley, W.E.; Derksen, R.C.; Krause, C.R. Adjuvant Effects on Evaporation Time and Wetted Area of Droplets on Waxy Leaves. Trans. ASABE 2010, 53, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, I.M.M.; Santos, B.L.P.; Ruzene, D.S.; Silva, D.P. An Overview of Current Research and Developments in Biosurfactants. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2021, 100, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostás, M.; Blassmann, K. Insects Had It First: Surfactants as a Defence Against Predators. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2009, 276, 633–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gens | Gene Description | Primers (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

| g545 | Vitamin D3 24-hydroxylase | CTTGACGACTCTCCCGAAGG |

| GAAAAACCGACTCCCGTCCT | ||

| g77 | Glycerol kinase | CAAGTCATTACGGGGCCTCA |

| CAGAGTCGAGATGCCACCAA | ||

| g342 | Glyceraldehyde dehydrogenase | CAAGTCCAGCAACGAGCAAA |

| AAGGCCACCTTGTCTACGTC | ||

| g374 | Homologous genes of killer toxin α/β subunits | TCCCGTGCCTCTTCTTTCAC |

| CCCGGGTATTCCCAATCGAG | ||

| g332 | Inositol polyphosphate kinase 2 | ACGTGACCTGGATACCGAAC |

| CCAGACCGATGCCACTATCA | ||

| ACT | Actin | TCGGTATGGGTCAGAAGGAC |

| GGAGCCTCAGTCAACAGGAC |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; Chang, L.; Lian, Q.; Du, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhang, G.; Liu, Z. Antifungal Activity of Surfactin Against Cytospora chrysosperma. Biomolecules 2026, 16, 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010051

Wang X, Chang L, Lian Q, Du Y, Huang J, Zhang G, Liu Z. Antifungal Activity of Surfactin Against Cytospora chrysosperma. Biomolecules. 2026; 16(1):51. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010051

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xinyue, Liangqiang Chang, Qinggui Lian, Yejuan Du, Jiafeng Huang, Guoqiang Zhang, and Zheng Liu. 2026. "Antifungal Activity of Surfactin Against Cytospora chrysosperma" Biomolecules 16, no. 1: 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010051

APA StyleWang, X., Chang, L., Lian, Q., Du, Y., Huang, J., Zhang, G., & Liu, Z. (2026). Antifungal Activity of Surfactin Against Cytospora chrysosperma. Biomolecules, 16(1), 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010051