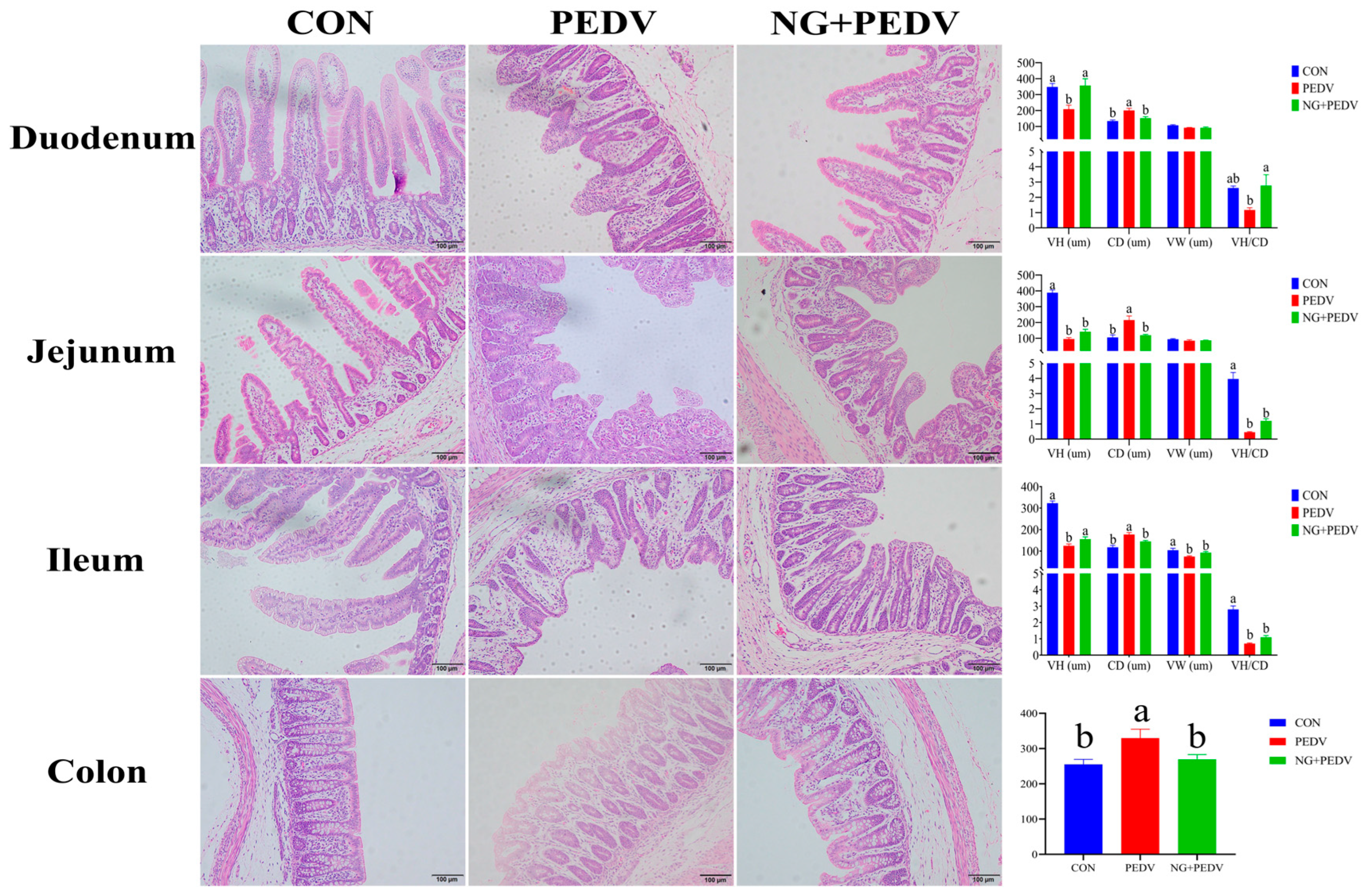

Figure 1.

Effect of NG on the morphological structure of intestine in PEDV-infected piglets. VH: Villus height; CD: Crypt depth; VW: Villus width; VH/CD: Ratio of villus height to crypt depth. CON, the control group. PEDV, the PEDV infection group. NG + PEDV, the NG + PEDV infection group. Data are presented as means ± standard error of the mean for each group (n = 6). a, b Values within a column that do not share a common superscript letter indicate a significant difference at p < 0.05. Values with mixed superscript letters (ab) are not significantly different from the groups labeled with a or b alone.

Figure 1.

Effect of NG on the morphological structure of intestine in PEDV-infected piglets. VH: Villus height; CD: Crypt depth; VW: Villus width; VH/CD: Ratio of villus height to crypt depth. CON, the control group. PEDV, the PEDV infection group. NG + PEDV, the NG + PEDV infection group. Data are presented as means ± standard error of the mean for each group (n = 6). a, b Values within a column that do not share a common superscript letter indicate a significant difference at p < 0.05. Values with mixed superscript letters (ab) are not significantly different from the groups labeled with a or b alone.

Figure 2.

Effect of NG on the antioxidant capacity of PEDV-infected piglets. GSH-PX: Glutathione peroxidase; CAT: Catalase; T-SOD: Total superoxide dismutase; H2O2: Hydrogen peroxide; MDA: Malondialdehyde; MPO: Myeloperoxidase. CON, the control group. PEDV, the PEDV infection group. NG + PEDV, the NG + PEDV infection group. Data are presented as means ± standard error of the mean for each group (n = 6). a, b, c Values within a column that do not share a common superscript letter indicate a significant difference at p < 0.05. Values with mixed superscript letters (ab) are not significantly different from the groups labeled with a or b alone.

Figure 2.

Effect of NG on the antioxidant capacity of PEDV-infected piglets. GSH-PX: Glutathione peroxidase; CAT: Catalase; T-SOD: Total superoxide dismutase; H2O2: Hydrogen peroxide; MDA: Malondialdehyde; MPO: Myeloperoxidase. CON, the control group. PEDV, the PEDV infection group. NG + PEDV, the NG + PEDV infection group. Data are presented as means ± standard error of the mean for each group (n = 6). a, b, c Values within a column that do not share a common superscript letter indicate a significant difference at p < 0.05. Values with mixed superscript letters (ab) are not significantly different from the groups labeled with a or b alone.

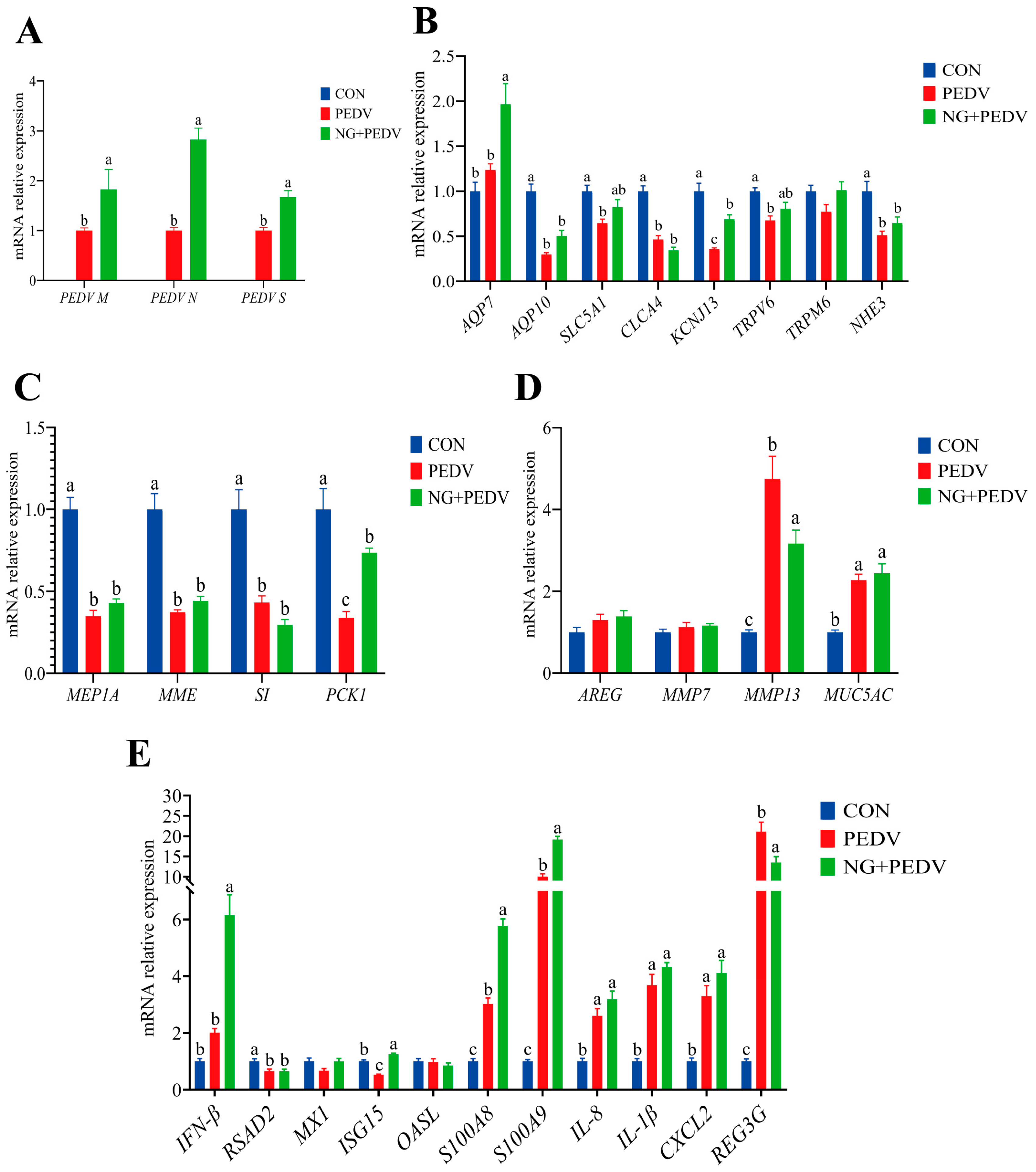

Figure 3.

Effect of NG on duodenal-related genes in PEDV-infected piglets. (A) PEDV-associated genes; (B) Genes associated with water and ion transport channels; (C) Genes associated with digestion and absorption; (D) Genes associated with tissue injury and repair; (E) Genes associated with immunity and inflammation. PEDV M, Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Membrane Protein; PEDV N, Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Nucleocapsid Protein; PEDV S, Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Spike Protein; AQP7, Aquaporin 7; AQP10, Aquaporin 10; SLC5A1, Solute Carrier Family 5 Member 1; CLCA4, Chloride Channel Accessory 4; KCNJ13, Potassium Inwardly Rectifying Channel Subfamily J Member 13; TRPM6, Transient Receptor Potential Cation Channel Subfamily M Member 6; TRPV6, Transient Receptor Potential Cation Channel Subfamily V Member 6; NHE3, Sodium Hydrogen Exchanger 3; MEP1A, Meprin A Subunit Alpha; MME, Membrane Metalloendopeptidase; SI, Sucrase-Isomaltase; PCK1, Phosphoenolpyruvate Carboxykinase 1; AREG, Amphiregulin; MMP7, Matrix Metallopeptidase 7; MMP13, Matrix Metallopeptidase 13; MUC5AC, Mucin 5AC, Oligomeric Mucus/Gel-Forming; IFN-β, Interferon Beta; RSAD2, Radical S-Adenosyl Methionine Domain Containing 2; MX1, MX Dynamin Like GTPase 1; ISG15, Interferon Stimulated Gene 15; OASL, 2′,5′-Oligoadenylate Synthetase Like; S100A8, S100 Calcium Binding Protein A8; S100A9, S100 Calcium Binding Protein A9; IL-8, Interleukin 8; IL-1β, Interleukin 1 Beta; CXCL2, C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 2; REG3G, Regenerating Family Member 3 Gamma. CON, the control group. PEDV, the PEDV infection group. NG + PEDV, the NG + PEDV infection group. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean for each group (n = 6). a, b, c Values within a column that do not share a common superscript letter indicate a significant difference at p < 0.05. Values with mixed superscript letters (ab) are not significantly different from the groups labeled with a or b alone.

Figure 3.

Effect of NG on duodenal-related genes in PEDV-infected piglets. (A) PEDV-associated genes; (B) Genes associated with water and ion transport channels; (C) Genes associated with digestion and absorption; (D) Genes associated with tissue injury and repair; (E) Genes associated with immunity and inflammation. PEDV M, Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Membrane Protein; PEDV N, Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Nucleocapsid Protein; PEDV S, Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Spike Protein; AQP7, Aquaporin 7; AQP10, Aquaporin 10; SLC5A1, Solute Carrier Family 5 Member 1; CLCA4, Chloride Channel Accessory 4; KCNJ13, Potassium Inwardly Rectifying Channel Subfamily J Member 13; TRPM6, Transient Receptor Potential Cation Channel Subfamily M Member 6; TRPV6, Transient Receptor Potential Cation Channel Subfamily V Member 6; NHE3, Sodium Hydrogen Exchanger 3; MEP1A, Meprin A Subunit Alpha; MME, Membrane Metalloendopeptidase; SI, Sucrase-Isomaltase; PCK1, Phosphoenolpyruvate Carboxykinase 1; AREG, Amphiregulin; MMP7, Matrix Metallopeptidase 7; MMP13, Matrix Metallopeptidase 13; MUC5AC, Mucin 5AC, Oligomeric Mucus/Gel-Forming; IFN-β, Interferon Beta; RSAD2, Radical S-Adenosyl Methionine Domain Containing 2; MX1, MX Dynamin Like GTPase 1; ISG15, Interferon Stimulated Gene 15; OASL, 2′,5′-Oligoadenylate Synthetase Like; S100A8, S100 Calcium Binding Protein A8; S100A9, S100 Calcium Binding Protein A9; IL-8, Interleukin 8; IL-1β, Interleukin 1 Beta; CXCL2, C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 2; REG3G, Regenerating Family Member 3 Gamma. CON, the control group. PEDV, the PEDV infection group. NG + PEDV, the NG + PEDV infection group. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean for each group (n = 6). a, b, c Values within a column that do not share a common superscript letter indicate a significant difference at p < 0.05. Values with mixed superscript letters (ab) are not significantly different from the groups labeled with a or b alone.

![Biomolecules 16 00048 g003 Biomolecules 16 00048 g003]()

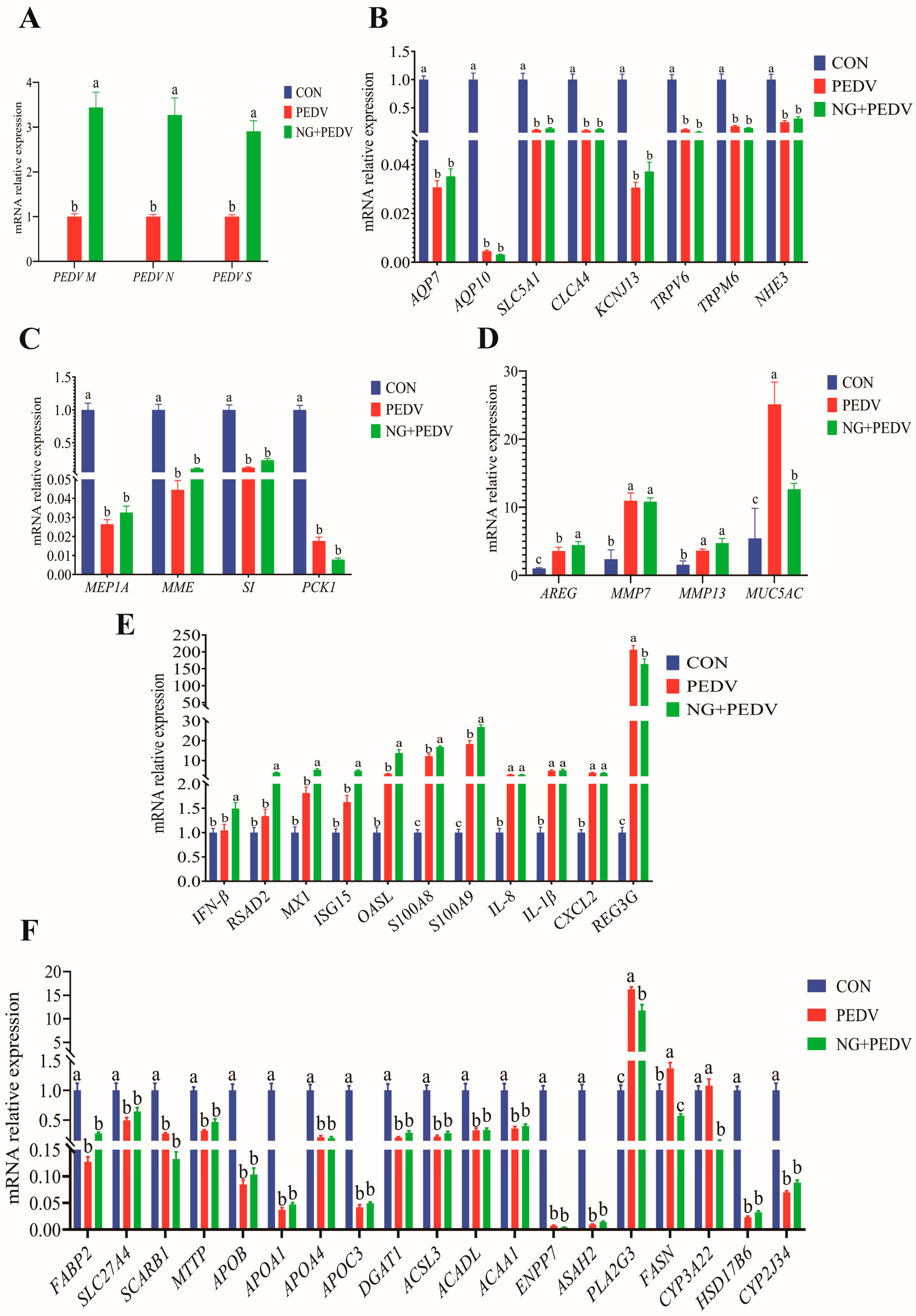

Figure 4.

Effect of NG on jejunum-related genes in PEDV-infected piglets. (A) PEDV-related genes; (B) Genes associated with water and ion transport channels; (C) Genes related to digestion and absorption; (D) Genes linked to tissue injury and repair; (E) Genes involved in immunity and inflammation; (F) Genes associated with lipid metabolism. PEDV M, Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Membrane Protein; PEDV N, Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Nucleocapsid Protein; PEDV S, Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Spike Protein; AQP7, Aquaporin 7; AQP10, Aquaporin 10; SLC5A1, Solute Carrier Family 5 Member 1; CLCA4, Chloride Channel Accessory 4; KCNJ13, Potassium Inwardly Rectifying Channel Subfamily J Member 13; TRPM6, Transient Receptor Potential Cation Channel Subfamily M Member 6; TRPV6, Transient Receptor Potential Cation Channel Subfamily V Member 6; NHE3, Sodium Hydrogen Exchanger 3; MEP1A, Meprin A Subunit Alpha; MME, Membrane Metalloendopeptidase; SI, Sucrase-Isomaltase; PCK1, Phosphoenolpyruvate Carboxykinase 1; AREG, Amphiregulin; MMP7, Matrix Metallopeptidase 7; MMP13, Matrix Metallopeptidase 13; MUC5AC, Mucin 5AC, Oligomeric Mucus/Gel-Forming; IFN-β, Interferon Beta; RSAD2, Radical S-Adenosyl Methionine Domain Containing 2; MX1, MX Dynamin Like GTPase 1; ISG15, Interferon Stimulated Gene 15; OASL, 2′,5′-Oligoadenylate Synthetase Like; S100A8, S100 Calcium Binding Protein A8; S100A9, S100 Calcium Binding Protein A9; IL-8, Interleukin 8; IL-1β, Interleukin 1 Beta; CXCL2, C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 2; REG3G, Regenerating Family Member 3 Gamma; FABP2, Fatty Acid Binding Protein 2, Intestinal; SLC27A4, Solute Carrier Family 27 Member 4; SCARB1, Scavenger Receptor Class B Member 1; MTTP, Microsomal Triglyceride Transfer Protein; APOB, Apolipoprotein B; APOA1, Apolipoprotein A1; APOA4, Apolipoprotein A4; APOC3, Apolipoprotein C3; DGAT1, Diacylglycerol O-Acyltransferase 1; ACSL3, Acyl-CoA Synthetase Long Chain Family Member 3; ACADL, Acyl-CoA Dehydrogenase, Long Chain; ACAA1, Acetyl-CoA Acyltransferase 1; ENPP7, Ectonucleotide Pyrophosphatase/Phosphodiesterase Family Member 7; ASAH2, N-Acylsphingosine Amidohydrolase 2; PLA2G3, Phospholipase A2 Group III; FASN, Fatty Acid Synthase; CYP3A22, Cytochrome P450 Family 3 Subfamily A Member 22; HSD17B6, Hydroxysteroid 17-Beta Dehydrogenase 6; CYP2J34, Cytochrome P450 Family 2 Subfamily J Member 34. CON, the control group. PEDV, the PEDV infection group. NG + PEDV, the NG + PEDV infection group. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean for each group (n = 6). a, b, c Values within a column that do not share a common superscript letter indicate a significant difference at p < 0.05.

Figure 4.

Effect of NG on jejunum-related genes in PEDV-infected piglets. (A) PEDV-related genes; (B) Genes associated with water and ion transport channels; (C) Genes related to digestion and absorption; (D) Genes linked to tissue injury and repair; (E) Genes involved in immunity and inflammation; (F) Genes associated with lipid metabolism. PEDV M, Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Membrane Protein; PEDV N, Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Nucleocapsid Protein; PEDV S, Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Spike Protein; AQP7, Aquaporin 7; AQP10, Aquaporin 10; SLC5A1, Solute Carrier Family 5 Member 1; CLCA4, Chloride Channel Accessory 4; KCNJ13, Potassium Inwardly Rectifying Channel Subfamily J Member 13; TRPM6, Transient Receptor Potential Cation Channel Subfamily M Member 6; TRPV6, Transient Receptor Potential Cation Channel Subfamily V Member 6; NHE3, Sodium Hydrogen Exchanger 3; MEP1A, Meprin A Subunit Alpha; MME, Membrane Metalloendopeptidase; SI, Sucrase-Isomaltase; PCK1, Phosphoenolpyruvate Carboxykinase 1; AREG, Amphiregulin; MMP7, Matrix Metallopeptidase 7; MMP13, Matrix Metallopeptidase 13; MUC5AC, Mucin 5AC, Oligomeric Mucus/Gel-Forming; IFN-β, Interferon Beta; RSAD2, Radical S-Adenosyl Methionine Domain Containing 2; MX1, MX Dynamin Like GTPase 1; ISG15, Interferon Stimulated Gene 15; OASL, 2′,5′-Oligoadenylate Synthetase Like; S100A8, S100 Calcium Binding Protein A8; S100A9, S100 Calcium Binding Protein A9; IL-8, Interleukin 8; IL-1β, Interleukin 1 Beta; CXCL2, C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 2; REG3G, Regenerating Family Member 3 Gamma; FABP2, Fatty Acid Binding Protein 2, Intestinal; SLC27A4, Solute Carrier Family 27 Member 4; SCARB1, Scavenger Receptor Class B Member 1; MTTP, Microsomal Triglyceride Transfer Protein; APOB, Apolipoprotein B; APOA1, Apolipoprotein A1; APOA4, Apolipoprotein A4; APOC3, Apolipoprotein C3; DGAT1, Diacylglycerol O-Acyltransferase 1; ACSL3, Acyl-CoA Synthetase Long Chain Family Member 3; ACADL, Acyl-CoA Dehydrogenase, Long Chain; ACAA1, Acetyl-CoA Acyltransferase 1; ENPP7, Ectonucleotide Pyrophosphatase/Phosphodiesterase Family Member 7; ASAH2, N-Acylsphingosine Amidohydrolase 2; PLA2G3, Phospholipase A2 Group III; FASN, Fatty Acid Synthase; CYP3A22, Cytochrome P450 Family 3 Subfamily A Member 22; HSD17B6, Hydroxysteroid 17-Beta Dehydrogenase 6; CYP2J34, Cytochrome P450 Family 2 Subfamily J Member 34. CON, the control group. PEDV, the PEDV infection group. NG + PEDV, the NG + PEDV infection group. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean for each group (n = 6). a, b, c Values within a column that do not share a common superscript letter indicate a significant difference at p < 0.05.

![Biomolecules 16 00048 g004 Biomolecules 16 00048 g004]()

Figure 5.

Effect of NG on ileus-related genes in PEDV-infected piglets. (A) PEDV-related genes; (B) Genes associated with water and ion transport channels; (C) Genes related to digestion and absorption; (D) Genes linked to tissue injury and repair; (E) Genes involved in immunity and inflammation; (F) Genes associated with lipid metabolism. PEDV M, Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Membrane Protein; PEDV N, Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Nucleocapsid Protein; PEDV S, Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Spike Protein; AQP7, Aquaporin 7; AQP10, Aquaporin 10; SLC5A1, Solute Carrier Family 5 Member 1; CLCA4, Chloride Channel Accessory 4; KCNJ13, Potassium Inwardly Rectifying Channel Subfamily J Member 13; TRPM6, Transient Receptor Potential Cation Channel Subfamily M Member 6; TRPV6, Transient Receptor Potential Cation Channel Subfamily V Member 6; NHE3, Sodium Hydrogen Exchanger 3; MEP1A, Meprin A Subunit Alpha; MME, Membrane Metalloendopeptidase; SI, Sucrase-Isomaltase; PCK1, Phosphoenolpyruvate Carboxykinase 1; AREG, Amphiregulin; MMP7, Matrix Metallopeptidase 7; MMP13, Matrix Metallopeptidase 13; MUC5AC, Mucin 5AC, Oligomeric Mucus/Gel-Forming; IFN-β, Interferon Beta; RSAD2, Radical S-Adenosyl Methionine Domain Containing 2; MX1, MX Dynamin Like GTPase 1; ISG15, Interferon Stimulated Gene 15; OASL, 2′,5′-Oligoadenylate Synthetase Like; S100A8, S100 Calcium Binding Protein A8; S100A9, S100 Calcium Binding Protein A9; IL-8, Interleukin 8; IL-1β, Interleukin 1 Beta; CXCL2, C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 2; REG3G, Regenerating Family Member 3 Gamma; FABP2, Fatty Acid Binding Protein 2, Intestinal; SLC27A4, Solute Carrier Family 27 Member 4; SCARB1, Scavenger Receptor Class B Member 1; MTTP, Microsomal Triglyceride Transfer Protein; APOB, Apolipoprotein B; APOA1, Apolipoprotein A1; APOA4, Apolipoprotein A4; APOC3, Apolipoprotein C3; DGAT1, Diacylglycerol O-Acyltransferase 1; ACSL3, Acyl-CoA Synthetase Long Chain Family Member 3; ACADL, Acyl-CoA Dehydrogenase, Long Chain; ACAA1, Acetyl-CoA Acyltransferase 1; ENPP7, Ectonucleotide Pyrophosphatase/Phosphodiesterase Family Member 7; ASAH2, N-Acylsphingosine Amidohydrolase 2; PLA2G3, Phospholipase A2 Group III; FASN, Fatty Acid Synthase; CYP3A22, Cytochrome P450 Family 3 Subfamily A Member 22; HSD17B6, Hydroxysteroid 17-Beta Dehydrogenase 6; CYP2J34, Cytochrome P450 Family 2 Subfamily J Member 34. CON, the control group. PEDV, the PEDV infection group. NG + PEDV, the NG + PEDV infection group. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean for each group (n = 6). a, b, c Values within a column that do not share a common superscript letter indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Effect of NG on ileus-related genes in PEDV-infected piglets. (A) PEDV-related genes; (B) Genes associated with water and ion transport channels; (C) Genes related to digestion and absorption; (D) Genes linked to tissue injury and repair; (E) Genes involved in immunity and inflammation; (F) Genes associated with lipid metabolism. PEDV M, Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Membrane Protein; PEDV N, Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Nucleocapsid Protein; PEDV S, Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Spike Protein; AQP7, Aquaporin 7; AQP10, Aquaporin 10; SLC5A1, Solute Carrier Family 5 Member 1; CLCA4, Chloride Channel Accessory 4; KCNJ13, Potassium Inwardly Rectifying Channel Subfamily J Member 13; TRPM6, Transient Receptor Potential Cation Channel Subfamily M Member 6; TRPV6, Transient Receptor Potential Cation Channel Subfamily V Member 6; NHE3, Sodium Hydrogen Exchanger 3; MEP1A, Meprin A Subunit Alpha; MME, Membrane Metalloendopeptidase; SI, Sucrase-Isomaltase; PCK1, Phosphoenolpyruvate Carboxykinase 1; AREG, Amphiregulin; MMP7, Matrix Metallopeptidase 7; MMP13, Matrix Metallopeptidase 13; MUC5AC, Mucin 5AC, Oligomeric Mucus/Gel-Forming; IFN-β, Interferon Beta; RSAD2, Radical S-Adenosyl Methionine Domain Containing 2; MX1, MX Dynamin Like GTPase 1; ISG15, Interferon Stimulated Gene 15; OASL, 2′,5′-Oligoadenylate Synthetase Like; S100A8, S100 Calcium Binding Protein A8; S100A9, S100 Calcium Binding Protein A9; IL-8, Interleukin 8; IL-1β, Interleukin 1 Beta; CXCL2, C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 2; REG3G, Regenerating Family Member 3 Gamma; FABP2, Fatty Acid Binding Protein 2, Intestinal; SLC27A4, Solute Carrier Family 27 Member 4; SCARB1, Scavenger Receptor Class B Member 1; MTTP, Microsomal Triglyceride Transfer Protein; APOB, Apolipoprotein B; APOA1, Apolipoprotein A1; APOA4, Apolipoprotein A4; APOC3, Apolipoprotein C3; DGAT1, Diacylglycerol O-Acyltransferase 1; ACSL3, Acyl-CoA Synthetase Long Chain Family Member 3; ACADL, Acyl-CoA Dehydrogenase, Long Chain; ACAA1, Acetyl-CoA Acyltransferase 1; ENPP7, Ectonucleotide Pyrophosphatase/Phosphodiesterase Family Member 7; ASAH2, N-Acylsphingosine Amidohydrolase 2; PLA2G3, Phospholipase A2 Group III; FASN, Fatty Acid Synthase; CYP3A22, Cytochrome P450 Family 3 Subfamily A Member 22; HSD17B6, Hydroxysteroid 17-Beta Dehydrogenase 6; CYP2J34, Cytochrome P450 Family 2 Subfamily J Member 34. CON, the control group. PEDV, the PEDV infection group. NG + PEDV, the NG + PEDV infection group. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean for each group (n = 6). a, b, c Values within a column that do not share a common superscript letter indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

![Biomolecules 16 00048 g005 Biomolecules 16 00048 g005]()

Figure 6.

Effects of NG on colon-related gene expression in PEDV-infected piglets. (A) PEDV-related genes; (B) Genes associated with tissue injury and repair; (C) Genes related to water and ion transport channels; (D) Genes linked to immunity and inflammation. PEDV M, Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Membrane Protein; PEDV N, Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Nucleocapsid Protein; PEDV S, Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Spike Protein; AREG, Amphiregulin; MMP7, Matrix Metallopeptidase 7; MMP13, Matrix Metallopeptidase 13; MUC5AC, Mucin 5AC, Oligomeric Mucus/Gel-Forming; AQP7, Aquaporin 7; AQP10, Aquaporin 10; SLC5A1, Solute Carrier Family 5 Member 1; CLCA4, Chloride Channel Accessory 4; KCNJ13, Potassium Inwardly Rectifying Channel Subfamily J Member 13; TRPM6, Transient Receptor Potential Cation Channel Subfamily M Member 6; TRPV6, Transient Receptor Potential Cation Channel Subfamily V Member 6; NHE3, Sodium Hydrogen Exchanger 3; IFN-β, Interferon Beta; RSAD2, Radical S-Adenosyl Methionine Domain Containing 2; MX1, MX Dynamin Like GTPase 1; ISG15, Interferon Stimulated Gene 15; OASL, 2′,5′-Oligoadenylate Synthetase Like; S100A8, S100 Calcium Binding Protein A8; S100A9, S100 Calcium Binding Protein A9; IL-8, Interleukin 8; IL-1β, Interleukin 1 Beta; CXCL2, C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 2; REG3G, Regenerating Family Member 3 Gamma. CON, the control group. PEDV, the PEDV infection group. NG + PEDV, the NG + PEDV infection group. Data is presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) for each group (n = 6). Significant differences among groups are indicated by different superscript letters a, b, c within a column (p < 0.05).

Figure 6.

Effects of NG on colon-related gene expression in PEDV-infected piglets. (A) PEDV-related genes; (B) Genes associated with tissue injury and repair; (C) Genes related to water and ion transport channels; (D) Genes linked to immunity and inflammation. PEDV M, Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Membrane Protein; PEDV N, Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Nucleocapsid Protein; PEDV S, Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Spike Protein; AREG, Amphiregulin; MMP7, Matrix Metallopeptidase 7; MMP13, Matrix Metallopeptidase 13; MUC5AC, Mucin 5AC, Oligomeric Mucus/Gel-Forming; AQP7, Aquaporin 7; AQP10, Aquaporin 10; SLC5A1, Solute Carrier Family 5 Member 1; CLCA4, Chloride Channel Accessory 4; KCNJ13, Potassium Inwardly Rectifying Channel Subfamily J Member 13; TRPM6, Transient Receptor Potential Cation Channel Subfamily M Member 6; TRPV6, Transient Receptor Potential Cation Channel Subfamily V Member 6; NHE3, Sodium Hydrogen Exchanger 3; IFN-β, Interferon Beta; RSAD2, Radical S-Adenosyl Methionine Domain Containing 2; MX1, MX Dynamin Like GTPase 1; ISG15, Interferon Stimulated Gene 15; OASL, 2′,5′-Oligoadenylate Synthetase Like; S100A8, S100 Calcium Binding Protein A8; S100A9, S100 Calcium Binding Protein A9; IL-8, Interleukin 8; IL-1β, Interleukin 1 Beta; CXCL2, C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 2; REG3G, Regenerating Family Member 3 Gamma. CON, the control group. PEDV, the PEDV infection group. NG + PEDV, the NG + PEDV infection group. Data is presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) for each group (n = 6). Significant differences among groups are indicated by different superscript letters a, b, c within a column (p < 0.05).

![Biomolecules 16 00048 g006 Biomolecules 16 00048 g006]()

Table 1.

Primer sequences for related genes.

Table 1.

Primer sequences for related genes.

| Gene Name | Forward (5′-3′) | Reverse (5′-3′) | Accession Number |

|---|

| ACAA1 | GGGAGAAGCAGGATACCTTTG | CATTGCCCTTGTCATCGTAGA | XM_021071664 |

| ACADL | GGATGGAAGTGACTGGATTCTC | GAGAGCGAGCTTCACGATTT | NM_213897 |

| ACSL3 | TTTTGCTGTCCCGTTGGTC | GTATCCACCTTCTTCCCAGTTCTTT | NM_001143698 |

| APOA1 | CCTTGGCTGTGCTCTTCCTC | ACGGTGGCAAAATCCTTCAC | NM_214398 |

| APOA4 | ACCCAGCAGCTCAACACTCTC | GAGTCCTTGGTCAGGCGTTC | NM_214388 |

| APOB | GGGATGATGGCACAGGTTACA | TGACGTGGACTTGGTGCTTT | NM_001375388 |

| APOC3 | CTAACCAGCGTGAAGGAGTC | CAGAAGTCGGTGAACTTGCC | NM_001002801 |

| AQP10 | GGGCGTTATACTAGCCATCTAC | CCAACTGCACCAAGGAGTAA | NM_001128454 |

| AQP7 | GAGTTCTTGGCCGAGTTCAT | CCCAACACGTACACAGGAAA | NM_001113438 |

| AREG | GAGTACGATAACGAACCGCACA | TTTCCACTTTTGCCTCCCTTT | NM_214376 |

| ASAH2 | ATAGAGCACCTACAGGCAAAC | TCGGGTTAGCACCTACAAATAC | XM_005671250 |

| CLCA4 | ACAGCGTTTGAGGTGGTTAG | ATGATGGCCCCACTTTGTTT | XM_001926978 |

| CXCL2 | CGGAAGTCATAGCCACTCTCAA | CAGTAGCCAGTAAGTTTCCTCCATC | NM_001001861 |

| CYP2J34 | TGAGGCTGTTGGATGAAGTC | TGAAGAGGGTTTGGTGGG | NM_001244633 |

| CYP3A22 | AGCTCCTAAGATTTGATTTCCTCG | CCACTCGGCGCATTTGTT | NM_001195509 |

| DGAT1 | GCTGGCTCTGATGGTCTACG | GTAGAGATCTGCAGAAGCGGC | XM_005655311 |

| ENPP7 | CTGCCTTATCACACCACACT | CGCCTTGGTAGGTGACATT | XM_013980746 |

| FABP2 | GAAACTTGCAGCTCATGACAAT | GTCTGCGAGGCTGTAGTTAAA | NM_001031780 |

| FASN | ACACCTTCGTGCTGGCCTAC | ATGTCGGTGAACTGCTGCAC | NM_001099930 |

| GPX2 | CCGGGACTTCACCCAACTC | CGGACGTACTTGAGGCTGTT | NM_001115136 |

| GSTO2 | GCCTTGAGATGTGGGAGAGAA | AAGATGGTGTTCTGATAGCCAAGA | XM_001927288 |

| HSD17B6 | TCAGATGTCCTGAGATGTGAGC | TCCAGACTTGCTTCATTGCCT | XM_005663895 |

| IFN-β | AGCAGATCTTCGGCATTCTC | GTCATCCATCTGCCCATCAA | NM_001003923 |

| IL-1β | CAACGTGCAGTCTATGGAGT | GAGGTGCTGATGTACCAGTTG | NM_214055 |

| IL-8 | TTCGATGCCAGTGCATAAATA | CTGTACAACCTTCTGCACCCA | NM_213867 |

| ISG15 | AGCATGGTCCTGTTGATGGTG | CAGAAATGGTCAGCTTGCACG | NM_001128469 |

| KCNJ13 | ATGGATGTGTCGCTGGTCTTT | CACAACTGCTTGCCTTTACGAG | XM_001926506 |

| MEP1A | AAGCTGGTCAAGATGAAGACCT | TTTGAGTTCTGGGGATCACCTT | XM_001928416 |

| MME | CACAACATCAGAAACAGCGACA | GGCAATCAAATCCTCAACCAC | XM_021069694 |

| MMP13 | AGTTTGGCCATTCCTTAGGTCTTG | GGCTTTTGCCAGTGTAGGTATAGAT | XM_003129808 |

| MMP7 | GGTGGCAGCATAGGCATTAAC | TCCGTAGGTTGGATACATCACAG | NM_001348795 |

| MTTP | CCGTCGAGTTCTGAAGGAAAT | GAATGCCAGAACCAGAGTAGAG | NM_214185 |

| MUC5AC | GTCAATGGCCGCACAATTCAG | CATCGTGGGAGAGGAACTCG | XM_021082583 |

| MX1 | AGTGCGGCTGTTTACCAAG | TTCACAAACCCTGGCAACTC | NM_214061 |

| NHE3 | AAGTACGTGAAGGCCAACATCTC | TTCTCCTTGACCTTGTTCTCGTC | XM_021077062 |

| OASL | GGCACCCCTGTTTTCCTCT | AGCACCGCTTTTGGATGG | NM_001031790 |

| PCK1 | CGGGATTTCGTGGAGA | CCTCTTGATGACACCCTCT | NM_001123158 |

| PEDV M | TCCCGTTGATGAGGTGAT | AGGATGCTGAAAGCGAAAA | KT021228 |

| PEDV N | TTGGTGGTAATGTGGCTGTTC | TGGTTTCACGCTTGTTCTTCTT | KT021228 |

| PEDV S | CTCTCTGGTACAGGCAGCAC | GCTCACGTAGAGTCAAGGCA | KT021228 |

| PLA2G3 | ACTCTGCTGGGAACTCATCT | GGTAGTTTCGGATGCCATAGTT | XM_021072944 |

| REG3G | CTGTCTCAGGTCCAAGGTGAAG | CAAGGCATAGCAGTAGGAAGCA | XM_005662419 |

| RPL19 | AACTCCCGTCAGCAGATCC | AGTACCCTTCCGCTTACCG | XM_003131509 |

| RSAD2 | CCCCACTAGCGTCAATTACC | TGATCTTCTCCATACCCGCT | NM_213817 |

| S100A8 | AACTCTGTTTCGGGGAGACC | CGCGTAGATGGCGTGGTAA | NM_001160271 |

| S100A9 | CCAGGATGTGGTTTATGGCTTTC | CGGACCAAATGTCGCAGA | XM_013997035 |

| SCARB1 | CTTCGTGAACCGCACTGTTG | CCCGGAATCGGAGTTGTTGA | NM_213967 |

| SI | ATGTCCGTGGTGGTCATATTC | TTTCCTTGTGCCGTCTGATTA | XM_021069750 |

| SLC27A4 | TGGAAAGGCGAGAACGTGT | CAGCAGAGTGGACAGTGAGCA | XM_021069609 |

| SLC5A1 | GTCATCTACTTCGTGGTGGTG | ACCCAAATCAGAGCATTCCATT | NM_001164021 |

| TRPM6 | TACGGGAAGAGATGTGGTGT | CGCCTGAGCTTCATCTCATT | XM_021064975 |

| TRPV6 | AGGAGCTGGTGAGCCTCAAGT | GGGGTCAGTTTGGTTGTTGG | NM_001436069 |

Table 2.

Piglets’ daily feed intake.

Table 2.

Piglets’ daily feed intake.

| | Group | Daily Feed Intake |

|---|

| D4 | CON | 3600 g/day |

| PEDV | 3600 g/day |

| NG + PEDV | 3600 g/day |

| D5 | CON | 3600 g/day |

| PEDV | 3600 g/day |

| NG + PEDV | 3600 g/day |

| D6 | CON | 3600 g/day |

| PEDV | 3600 g/day |

| NG + PEDV | 3600 g/day |

| D7 | CON | 3600 g/day |

| PEDV | 3600 g/day |

| NG + PEDV | 3600 g/day |

| D8 | CON | 3600 g/day |

| PEDV | 3600 g/day |

| NG + PEDV | 3600 g/day |

| D9 | CON | 3600 g/day |

| PEDV | 3600 g/day |

| NG + PEDV | 3600 g/day |

| D10 | CON | 3600 g/day |

| PEDV | 3600 g/day |

| NG + PEDV | 3600 g/day |

Table 3.

Effect of NG on ADG, diarrhea score, and diarrhea rate in PEDV-infected piglets.

Table 3.

Effect of NG on ADG, diarrhea score, and diarrhea rate in PEDV-infected piglets.

| Item | CON | PEDV | NG + PEDV | p-Value |

|---|

| ADG (g) (4–8) | 86.04 ± 10.28 | 87.08 ± 16.20 | 89.54 ± 18.08 | 0.161 |

| ADG (g) (8–11) | 141.67 ± 11.20 | 51.28 ± 37.73 | 80.58 ± 23.36 | 0.079 |

Table 4.

Effect of NG on serum DAO and D-xylose levels in PEDV-infected piglets.

Table 4.

Effect of NG on serum DAO and D-xylose levels in PEDV-infected piglets.

| Item | CON | PEDV | NG + PEDV | p-Value |

|---|

| DAO (U/L) | 7.55 ± 0.87 | 8.36 ± 0.37 | 7.57 ± 0.91 | 0.694 |

| D-xylose (mmol/L) | 0.99 ± 0.04 a | 0.56 ± 0.02 b | 0.61 ± 0.08 b | <0.001 |

Table 5.

Effect of NG on plasma biochemical parameters in PEDV-infected piglets.

Table 5.

Effect of NG on plasma biochemical parameters in PEDV-infected piglets.

| Item | CON | PEDV | NG + PEDV | p-Value |

|---|

| TB (μmol/L) | 1.89 ± 0.3 a | 1.01 ± 0.16 b | 2.29 ± 0.29 a | 0.01 |

| TP (g/L) | 53.71 ± 1.21 b | 63.61 ± 1.75 a | 66.52 ± 2.36 a | <0.001 |

| ALB (g/L) | 28.58 ± 0.75 b | 30.88 ± 1.45 b | 35.12 ± 0.89 a | 0.002 |

| AST (U/L) | 33.67 ± 4.28 | 30.83 ± 4.1 | 33.17 ± 3.35 | 0.864 |

| ALT (U/L) | 31.33 ± 3.39 b | 39.33 ± 2.11 ab | 46.67 ± 4.62 a | 0.025 |

| ALP (U/L) | 826 ± 79.63 a | 553.17 ± 49.05 b | 711.67 ± 62.05 ab | 0.03 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 3.84 ± 0.4 | 3.31 ± 0.16 | 4.43 ± 0.62 | 0.224 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 0.53 ± 0.05 b | 0.63 ± 0.05 b | 0.91 ± 0.09 a | 0.003 |

| GLU (mmol/L) | 6.85 ± 0.38 | 6.45 ± 0.42 | 7.32 ± 0.49 | 0.388 |

| Ca (g/L) | 4.93 ± 0.29 | 4.29 ± 0.11 | 4.73 ± 0.13 | 0.084 |

| P (mg/dL) | 2.66 ± 0.14 | 2.66 ± 0.1 | 2.69 ± 0.22 | 0.993 |

| CREA (μmol/L) | 64.66 ± 3.67 b | 75.83 ± 2.92 ab | 87.23 ± 3.61 a | 0.001 |

| HDL (mmol/L) | 1.77 ± 0.22 | 1.28 ± 0.09 | 1.67 ± 0.21 | 0.172 |

| LDL (mmol/L) | 1.22 ± 0.11 b | 1.23 ± 0.09 b | 1.81 ± 0.21 a | 0.016 |

| BUN (mmol/L) | 1.93 ± 0.22 b | 6.58 ± 0.57 a | 8.12 ± 0.69 a | <0.001 |

| GGT (U/L) | 45 ± 5.54 | 48 ± 2.92 | 58.33 ± 6.58 | 0.203 |

| CK (U/L) | 413.67 ± 46.2 a | 210.5 ± 17.74 b | 104.67 ± 13.79 b | <0.001 |

| LDH (U/L) | 772.52 ± 25.13 | 661.37 ± 24.04 | 727.58 ± 55.77 | 0.149 |

Table 6.

Effect of NG on hematological parameters of PEDV-infected piglets.

Table 6.

Effect of NG on hematological parameters of PEDV-infected piglets.

| Item | CON | PEDV | NG + PEDV | p-Value |

|---|

| WBC (109/L) | 9.37 ± 0.96 | 8.91 ± 0.45 | 10.72 ± 1.11 | 0.799 |

| Neu (109/L) | 2.91 ± 0.3 | 2.77 ± 0.28 | 2.84 ± 0.34 | 0.411 |

| Lym (109/L) | 6.44 ± 0.53 | 5.26 ± 0.4 | 5.71 ± 0.51 | 0.830 |

| Mon (109/L) | 0.35 ± 0.04 b | 0.72 ± 0.05 a | 0.83 ± 0.1 a | 0.008 |

| Eos (109/L) | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.142 |

| Neu% (%) | 31.9 ± 2.85 | 30.93 ± 2.38 | 38.05 ± 4.68 | 0.414 |

| Lym% (%) | 60.23 ± 4.57 | 59.08 ± 3.11 | 52.28 ± 4.71 | 0.374 |

| Mon% (%) | 3.88 ± 0.43 b | 8.97 ± 1.06 a | 9.07 ± 1.14 a | 0.008 |

| Eos% (%) | 0.68 ± 0.07 | 0.82 ± 0.04 | 0.6 ± 0.08 | 0.173 |

| RBC (1012/L) | 5.23 ± 0.38 | 6.31 ± 0.22 | 6.18 ± 0.75 | 0.275 |

| HGB (g/L) | 108.33 ± 7.85 | 131.67 ± 2.44 | 123 ± 13.78 | 0.231 |

| HCT (%) | 33.62 ± 2.35 | 41.17 ± 1.16 | 37.58 ± 4.24 | 0.212 |

| MCV (fL) | 64.47 ± 1.13 | 65.35 ± 1.64 | 61.45 ± 1.99 | 0.238 |

| MCH (pg) | 20.75 ± 0.47 | 20.92 ± 0.61 | 20.1 ± 0.53 | 0.541 |

| MCHC (g/L) | 322.33 ± 3.72 | 320.17 ± 4.54 | 327.33 ± 2.26 | 0.383 |

| RDW-CV (%) | 23.8 ± 0.56 | 23.38 ± 0.68 | 23.98 ± 0.69 | 0.799 |

| RDW-SD (fL) | 55.78 ± 1.33 | 55.73 ± 2.28 | 53.8 ± 2.76 | 0.772 |

| PLT (109/L) | 453.5 ± 51.04 | 451.14 ± 56.68 | 334.22 ± 39.44 | 0.371 |

| MPV (fL) | 9.9 ± 0.28 | 9.83 ± 0.43 | 9.95 ± 0.33 | 0.973 |

| PDW (%) | 15.4 ± 0.11 | 15.58 ± 0.1 | 15.28 ± 0.09 | 0.151 |

| PCT (%) | 0.45 ± 0.05 | 0.39 ± 0.03 | 0.33 ± 0.04 | 0.412 |