Virulence Reduction in Yersinia pestis by Combining Delayed Attenuation with Plasmid Curing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, and Culture Conditions

2.2. Animals

2.3. Construction of the Plasmids

2.4. Mutagenesis

2.5. Preparation of Crp Antiserum

2.6. Western Blotting

2.7. Animal Challenges

2.8. ELISA

2.9. In Vivo Cytokine Analysis

2.10. Statistics

3. Results

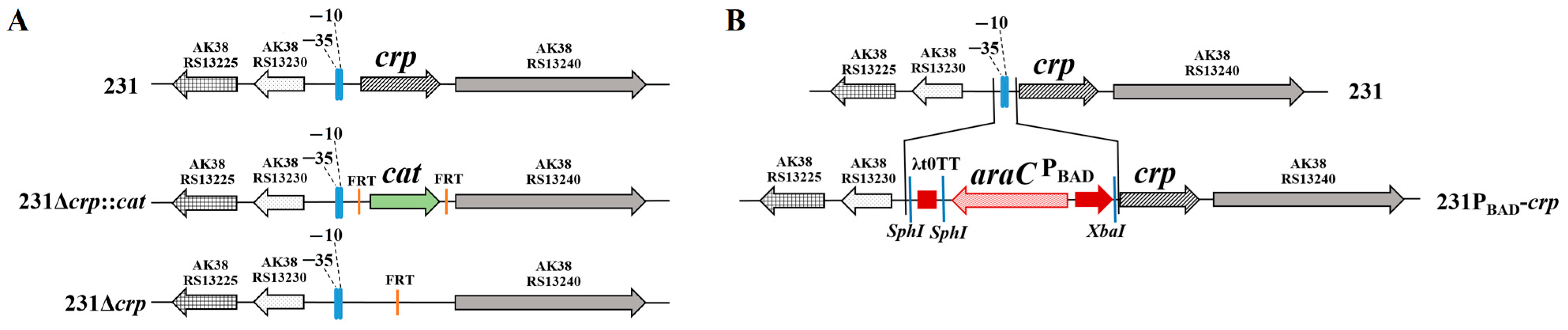

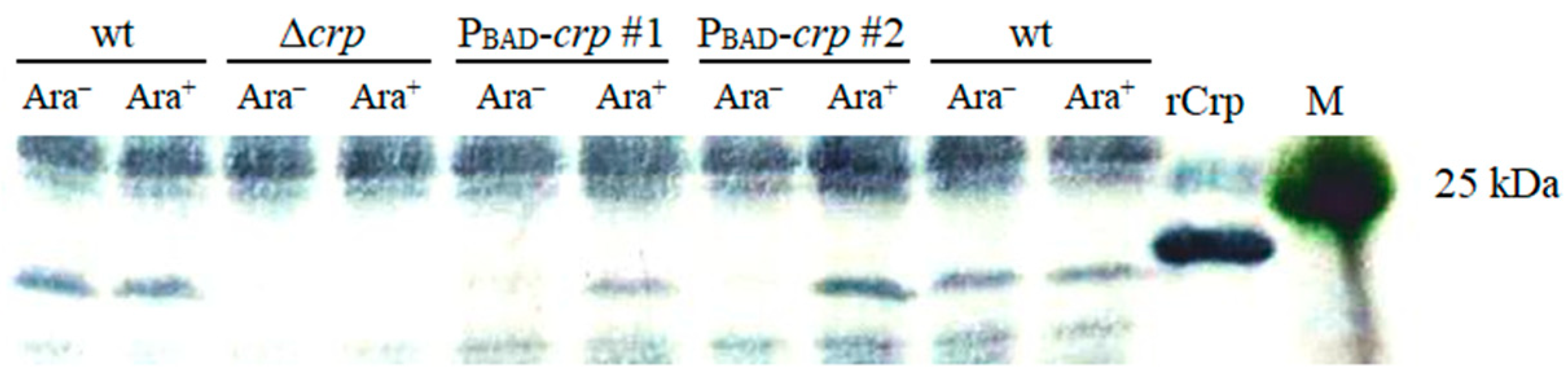

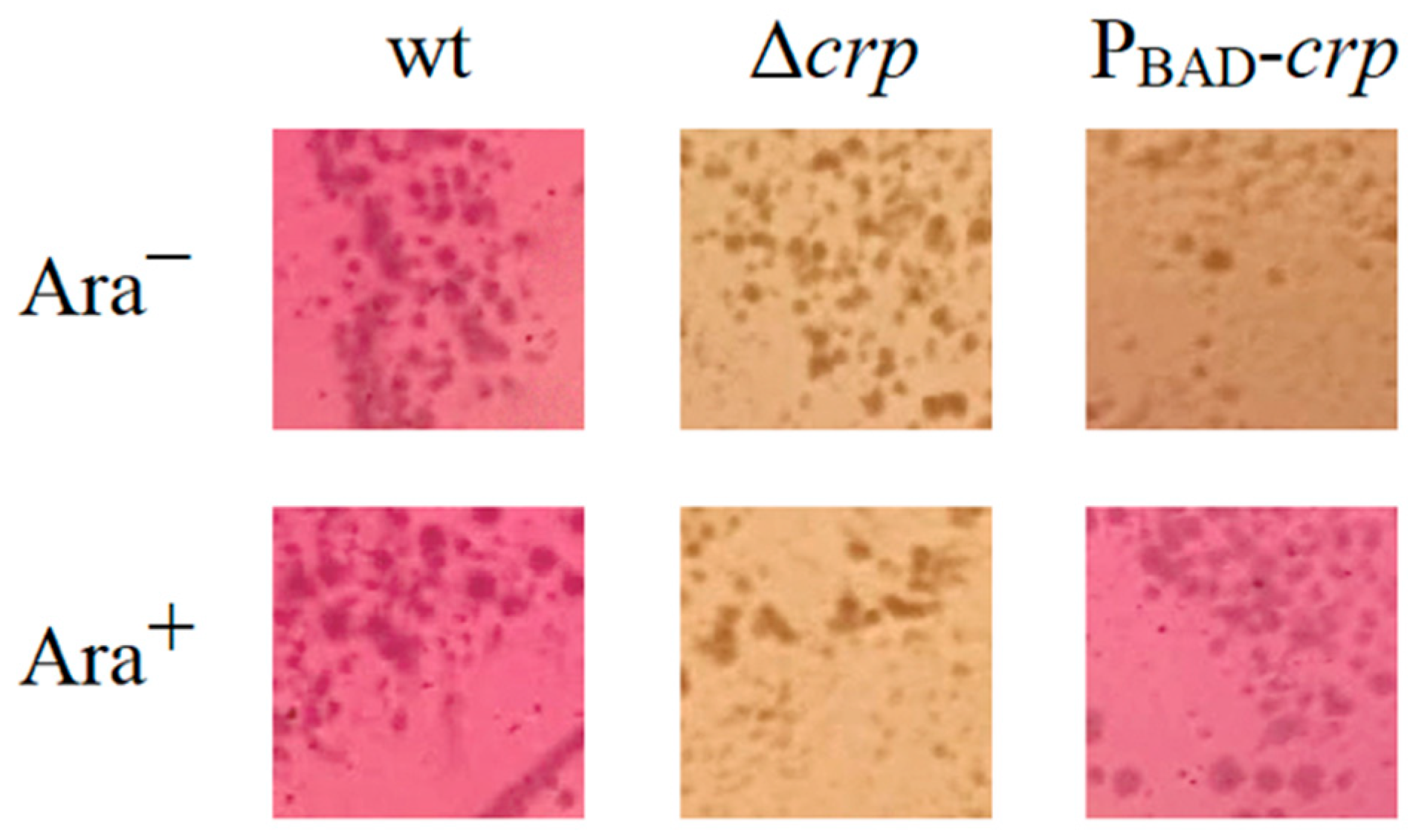

3.1. Construction of the Deletion-Insertion Mutation to Achieve Regulated Delayed Attenuation

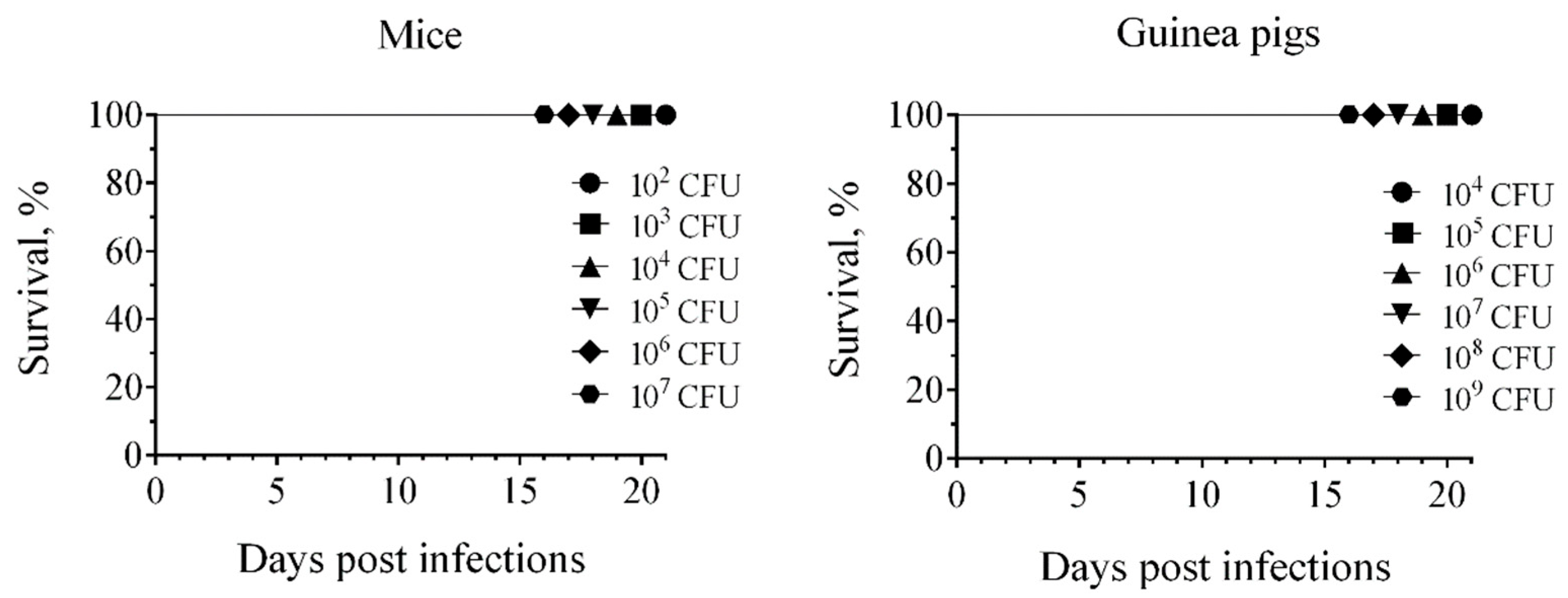

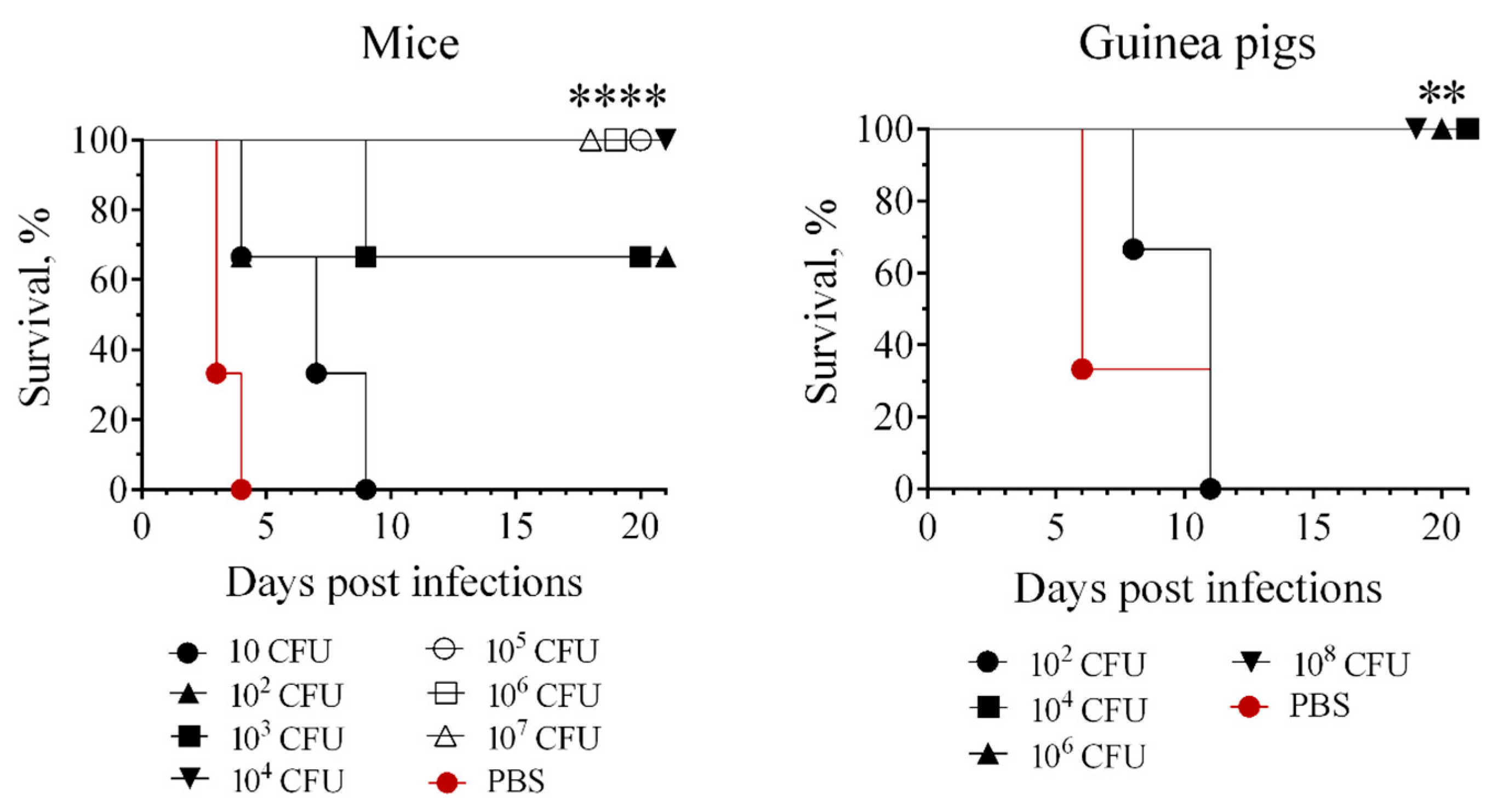

3.2. Attenuation of Mutant Strains in s.c. Challenged Mice and Guinea Pigs

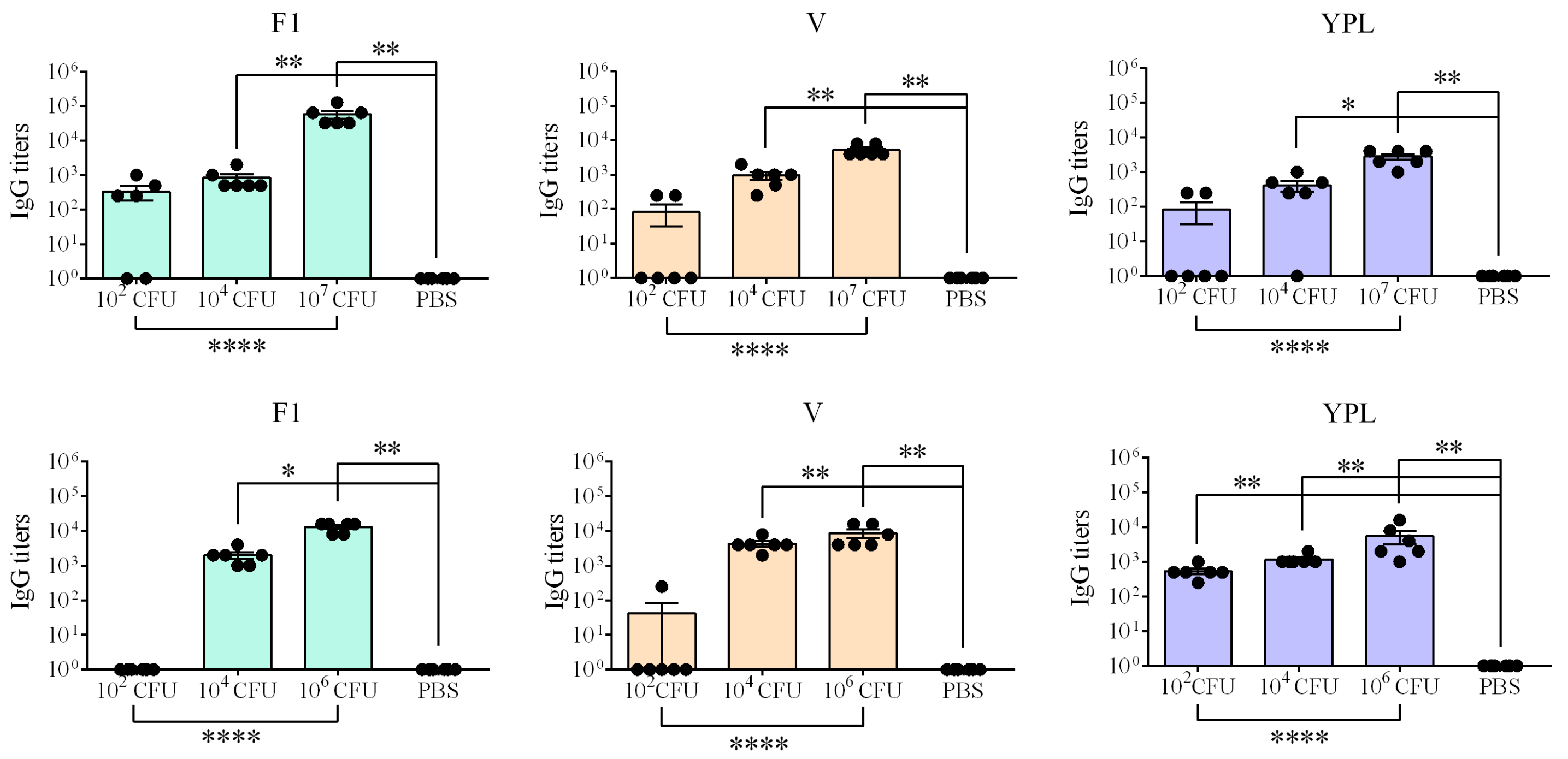

3.3. Humoral Immune Responses

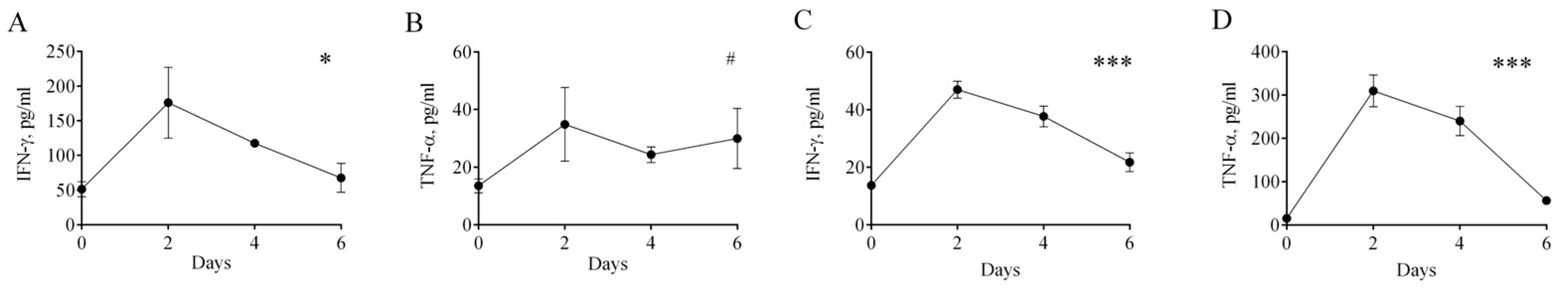

3.4. Cell-Mediated Immune Response

3.5. Ability of s.c. Administered Strain with araC PBAD-Regulated crp to Induce Protective Immunity to s.c. Challenge with Wild-Type Y. pestis Strain 231

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zeppelini, C.G.; De Almeida, A.M.P.; Cordeiro-Estrela, P. Zoonoses as Ecological Entities: A Case Review of Plague. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0004949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gage, K.L.; Kosoy, M.Y. Natural History of Plague: Perspectives from More than a Century of Research. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2005, 50, 505–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbieri, R.; Signoli, M.; Chevé, D.; Costedoat, C.; Tzortzis, S.; Aboudharam, G.; Raoult, D.; Drancourt, M. Yersinia pestis: The Natural History of Plague. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 34, e00044-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, B.A.; Jones, C.H.; Welch, V.; True, J.M. Outlook of Pandemic Preparedness in a Post-COVID-19 World. npj Vaccines 2023, 8, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukoaka, B.M.; Okesanya, O.J.; Daniel, F.M.; Ahmed, M.M.; Udam, N.G.; Wagwula, P.M.; Adigun, O.A.; Udoh, R.A.; Peter, I.G.; Lawal, H. Updated WHO List of Emerging Pathogens for a Potential Future Pandemic: Implications for Public Health and Global Preparedness. Infez. Med. 2024, 4, 463–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathogens Prioritization [Digest]. Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/consultation-rdb/prioritization-pathogens-v6final.pdf?sfvrsn=c98effa7_9&download=true (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Butler, T. Plague History: Yersin’s Discovery of the Causative Bacterium in 1894 Enabled, in the Subsequent Century, Scientific Progress in Understanding the Disease and the Development of Treatments and Vaccines. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2014, 20, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amelio, E.; Salemi, S.; D’Amelio, R. Anti-Infectious Human Vaccination in Historical Perspective. Int. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 35, 260–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workshop WHO. Efficacy Trials of Plague Vaccines: Endpoints, Trial Design, Site Selection. 2018. Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/blue-print/plaguevxeval-finalmeetingreport.pdf?sfvrsn=c251bd35_2 (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Adamovicz, J.J.; Andrews, G.P. Plague Vaccines. In Biological Weapons Defense; Lindler, L.E., Lebeda, F.J., Korch, G.W., Eds.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 121–153. ISBN 978-1-58829-184-4. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W. Plague Vaccines: Status and Future. In Yersinia pestis: Retrospective and Perspective; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Yang, R., Anisimov, A., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2016; Volume 918, pp. 313–360. ISBN 978-94-024-0888-1. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig, J.A.; Hendrix, E.K.; Chopra, A.K. Plague Vaccines: New Developments in an Ongoing Search. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 4931–4941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtiss, R.; Wanda, S.-Y.; Gunn, B.M.; Zhang, X.; Tinge, S.A.; Ananthnarayan, V.; Mo, H.; Wang, S.; Kong, W. Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium Strains with Regulated Delayed Attenuation In Vivo. Infect. Immun. 2009, 77, 1071–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtiss Iii, R.; Xin, W.; Li, Y.; Kong, W.; Wanda, S.-Y.; Gunn, B.; Wang, S. New Technologies in Using Recombinant Attenuated Salmonella Vaccine Vectors. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 2010, 30, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juárez-Rodríguez, M.D.; Yang, J.; Kader, R.; Alamuri, P.; Curtiss, R.; Clark-Curtiss, J.E. Live Attenuated Salmonella Vaccines Displaying Regulated Delayed Lysis and Delayed Antigen Synthesis to Confer Protection against Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 2012, 80, 815–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Roland, K.L.; Kuang, X.; Branger, C.G.; Curtiss, R. Yersinia pestis with Regulated Delayed Attenuation as a Vaccine Candidate to Induce Protective Immunity against Plague. Infect. Immun. 2010, 78, 1304–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allio, T. The FDA Animal Rule and Its Role in Protecting Human Safety. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2018, 17, 971–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, M.K.; Saviolakis, G.A.; Welkos, S.L.; House, R.V. Advanced Development of the rF1V and rBV A/B Vaccines: Progress and Challenges. Adv. Prev. Med. 2012, 2012, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kislichkina, A.A.; Krasil’nikova, E.A.; Platonov, M.E.; Skryabin, Y.P.; Sizova, A.A.; Solomentsev, V.I.; Gapel’chenkova, T.V.; Dentovskaya, S.V.; Bogun, A.G.; Anisimov, A.P. Whole-Genome Assembly of Yersinia pestis 231, the Russian Reference Strain for Testing Plague Vaccine Protection. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2021, 10, e01373-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datsenko, K.A.; Wanner, B.L. One-Step Inactivation of Chromosomal Genes in Escherichia coli K-12 Using PCR Products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 6640–6645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherepanov, P.P.; Wackernagel, W. Gene Disruption in Escherichia coli: TcR and KmR Cassettes with the Option of Flp-Catalyzed Excision of the Antibiotic-Resistance Determinant. Gene 1995, 158, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnenberg, M.S.; Kaper, J.B. Construction of an Eae Deletion Mutant of Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli by Using a Positive-Selection Suicide Vector. Infect. Immun. 1991, 59, 4310–4317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leal-Balbino, T.C.; Leal, N.C.; Nascimento, M.G.M.D.; Oliveira, M.B.M.D.; Balbino, V.D.Q.; Almeida, A.M.P.D. The pgm locus and pigmentation phenotype in Yersinia pestis. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2006, 29, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, W.D.; Stull, H.B. Gene Transfer in Pasteurella pestis Harboring the F′ Cm Plasmid of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1972, 110, 926–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmanyar, M.; Cavanaugh, D.C. Plague Manual; World Health Organization (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Ferber, D.M.; Brubaker, R.R. Plasmids in Yersinia pestis. Infect. Immun. 1981, 31, 839–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Gurion, R.; Shafferman, A. Essential Virulence Determinants of Different Yersinia Species Are Carried on a Common Plasmid. Plasmid 1981, 5, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portnoy, D.A.; Falkow, S. Virulence-Associated Plasmids from Yersinia enterocolitica and Yersinia pestis. J. Bacteriol. 1981, 148, 877–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Protsenko, O.A.; Anisimov, P.I.; Mozharov, O.T.; Konnov, N.P.; Popov, I.A. Detection and characterization of Yersinia pestis plasmids determining pesticin I, fraction I antigen, and “mouse” toxin synthesis. Genetika 1983, 19, 1081–1090. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kopylov, P.K.; Svetoch, T.E.; Ivanov, S.A.; Kombarova, T.I.; Perovskaya, O.N.; Titareva, G.M.; Anisimov, A.P. Characteristics of the Chromatographic Cleaning and Protectiveness of the LcrV Isoform of Yersinia pestis. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2019, 55, 524–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trunyakova, A.S.; Platonov, M.E.; Ivanov, S.A.; Kopylov, P.K.; Dentovskaya, S.V.; Anisimov, A.P. A Recombinant Low-Endotoxic Yersinia pseudotuberculosis Strain—Over-Producer of Yersinia pestis F1 Antigen. Genet. Microbiol. Virol. 2024, 42, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okan, N.A.; Mena, P.; Benach, J.L.; Bliska, J.B.; Karzai, A.W. The smpB-ssrA Mutant of Yersinia pestis Functions as a Live Attenuated Vaccine to Protect Mice against Pulmonary Plague Infection. Infect. Immun. 2010, 78, 1284–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinsiek, S.; Bettenbrock, K. Glucose Transport in Escherichia coli Mutant Strains with Defects in Sugar Transport Systems. J. Bacteriol. 2012, 194, 5897–5908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, J.A.; Henderson, L.M. New Technology for Improved Vaccine Safety and Efficacy. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Food Anim. Pract. 2001, 17, 585–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montminy, S.W.; Khan, N.; McGrath, S.; Walkowicz, M.J.; Sharp, F.; Conlon, J.E.; Fukase, K.; Kusumoto, S.; Sweet, C.; Miyake, K.; et al. Virulence factors of Yersinia pestis are overcome by a strong lipopolysaccharide response. Nat. Immunol. 2006, 7, 1066–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Six, D.; Kuang, X.; Roland, K.L.; Raetz, C.R.H.; Curtiss, R. A Live Attenuated Strain of Yersinia pestis KIM as a Vaccine against Plague. Vaccine 2011, 29, 2986–2998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodeinde, O.A.; Subrahmanyam, Y.V.; Stark, K.; Quan, T.; Bao, Y.; Goguen, J.D. A surface protease and the invasive character of plague. Science 1992, 258, 1004–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebbane, F.; Uversky, V.N.; Anisimov, A.P. Yersinia pestis Plasminogen Activator. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anisimova, T.I.; Sayapina, L.V.; Sergeeva, G.M.; Isupov, I.V.; Beloborodov, R.A.; Samoilova, L.V.; Anisimov, A.P.; Ledvanov, M.Y.; Shvedun, G.P.; Zadumina, S.Y.; et al. Main Requirements for Vaccine Strains of the Plague Pathogen: Methodological Guidelines MU 3.3.1.1113-02; Federal Centre of State Epidemic Surveillance of Ministry of Health of Russian Federation: Moscow, Russia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mba, I.E.; Sharndama, H.C.; Anyaegbunam, Z.K.G.; Anekpo, C.C.; Amadi, B.C.; Morumda, D.; Doowuese, Y.; Ihezuo, U.J.; Chukwukelu, J.U.; Okeke, O.P. Vaccine Development for Bacterial Pathogens: Advances, Challenges and Prospects. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2023, 28, 275–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anisimov, A.P.; Vagaiskaya, A.S.; Trunyakova, A.S.; Dentovskaya, S.V. Live Plague Vaccine Development: Past, Present, and Future. Vaccines 2025, 13, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korobkova, E.I. Live Antiplague Vaccine; Medgiz: Moscow, Russia, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, J.; Copse, C.; Leary, S.; Stagg, A.J.; Williamson, E.D.; Titball, R.W. Synergistic Protection of Mice against Plague with Monoclonal antibodies Specific for the F1 and V Antigens of Yersinia pestis. Infect. Immun. 2003, 71, 2234–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, M.; Rogers, D.; Russell, P.; Stagg, A.J.; Bell, D.L.; Eley, S.M.; Titball, R.W.; Williamson, E.D. The SCID/Beige Mouse as a Model to Investigate Protection against Yersinia pestis. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 1999, 23, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, E.D.; Flick-Smith, H.C.; Waters, E.; Miller, J.; Hodgson, I.; Le Butt, C.S.; Hill, J. Immunogenicity of the rF1+rV Vaccine for Plague with Identification of Potential Immune Correlates. Microb. Pathog. 2007, 42, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, B.D.; Macleod, C.; Henning, L.; Krile, R.; Chou, Y.-L.; Laws, T.R.; Butcher, W.A.; Moore, K.M.; Walker, N.J.; Williamson, E.D.; et al. Predictors of Survival after Vaccination in a Pneumonic Plague Model. Vaccines 2022, 10, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zheng, B.; Lu, J.; Wu, H.; Wu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Jiao, L.; Pan, H.; Zhou, J. Evaluation of Human Antibodies from Vaccinated Volunteers for Protection against Yersinia pestis Infection. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e01054-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smiley, S.T. Immune Defense against Pneumonic Plague. Immunol. Rev. 2008, 225, 256–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parent, M.A.; Wilhelm, L.B.; Kummer, L.W.; Szaba, F.M.; Mullarky, I.K.; Smiley, S.T. Gamma Interferon, Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha, and Nitric Oxide Synthase 2, Key Elements of Cellular Immunity, Perform Critical Protective Functions during Humoral Defense against Lethal Pulmonary Yersinia pestis Infection. Infect. Immun. 2006, 74, 3381–3386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, Y.; Flashner, Y.; Tidhar, A.; Zauberman, A.; Aftalion, M.; Lazar, S.; Gur, D.; Shafferman, A.; Mamroud, E. T Cells Play an Essential Role in Anti-F1 Mediated Rapid Protection against Bubonic Plague. Vaccine 2011, 29, 6866–6873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, E.D.; Kilgore, P.B.; Hendrix, E.K.; Neil, B.H.; Sha, J.; Chopra, A.K. Progress on the Research and Development of Plague Vaccines with a Call to Action. npj Vaccines 2024, 9, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Strain, Plasmid | Relevant Attributes | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Y. pestis | ||

| 231 | 0.ANT3 phylogroup, wild-type strain, universally virulent (LD50 for mice ≤ 10 CFU, for guinea pigs ≤ 10 CFU); Pgm+, pMT1+, pPst+, pCD+, parental strain | SCPM-O ** [19] |

| EV | 1.ORI3 phylogroup, vaccine strain, Δpgm *, pMT1+, pPst+, pCD+ | SCPM-O |

| EVΔcrp::cat | Δcrp derivative of EV, CmR | |

| 231Δcrp | Δcrp derivative of 231, CmS | This study |

| 231PBAD-crp | ΔPcrp::araC PBAD crp derivative of Y. pestis 231 | This study |

| 231PBAD-crp(pPst¯) | ΔPcrp::araC PBAD crp pPst¯ derivative of Y. pestis 231PBAD-crp | This study |

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | F−, gyrA96(Nalr), recA1, relA1, endA1, thi-1, hsdR17(rk–, mk+), glnV44, deoR, Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169, [φ80dΔ(lacZ)M15], supE44 | SCPM-O |

| S17-1 λpir | thi pro hsdR−hsdM+ recA RP4 2-Tc::Mu-Km::Tn7(TpRSmRPmS) | SCPM-O |

| BL21(DE3) | F–ompT hsdSB (rB– mB–) gal dcm (DE3) | SCPM-O |

| Plasmid | ||

| pKD46 | bla araC PBADgam bet exo pSC101 oriTS | [20] |

| pKD3 | bla FRT cat FRT PS1 PS2 oriR6K | [20] |

| pCP20 | bla cat cI857 λPRflp pSC101 oriTS | [21] |

| pET-24b (+) | kan pBR322 ori PT7 | Novagene (Madison, WI, USA; now Millipore Sigma) |

| pET24-crp | kan pBR322 ori PT7 crp | This study |

| pUC57 | bla pUC ori | Thermo Fisher Scientific (Vilnius, Lithunia) |

| pUC57-URcrp-araC Pbad-crp | bla pUC ori araC PBAD crp | This study |

| pUC57-URcrp-Lt0TT-araC PBAD-crp | bla pUC ori bacteriophage Lambda t0 transcriptional terminator PBAD crp | This study |

| pCVD442 | ori R6K mob RP4 bla sacB | [22] |

| pCVD442-Δcrp::cat | bla R6K ori RP4 mob sacB Δcrp::cat | This study |

| pCVD442-URcrp-Lt0TT- araC PBAD-crp | bla R6K ori RP4 mob sacB bacteriophage Lambda t0 transcriptional terminator PBAD crp | This study |

| crp Primers for Mutant Construction and Screening | |

| Crp1F | ATGGTTCTCGGTAAGCCACAAACAGACCCGACTCTCGAATGGTTCCTGTCTCATTATGGGAATTAGCCATGGTCC |

| Crp1R | TTAACGGGTGCCGTAAACGACGATCGTTTTACCGTGTGCGGAGATCAAGTTTTGAGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC |

| Crp2F | TAACAACAAAGATACAGCCC |

| Crp2R | AGTAACAAAATTGTGCCACC |

| Crp-KF | GACTTCGCGTACCTCAAAGC |

| Crp-KR | TACATAACCGGAACCACAAC |

| Primers for pCVD442-URcrp-Lt0TT-PBAD-crp Construction | |

| Pbad-SphI | GCGGCATGCATAATGTGCCTGTCAAATGG |

| Pbad-XbaI | GCGTCTAGAGAGAAACAGTAGAGAGTTGC |

| Lt0-SphIF | AGCGCATGCTGACTCCTGTTGATAGATCC |

| Lt0-SphIR | TTTGCATGCGACAAGTTGCTGCGATTCTC |

| Crp-Hind | CCTAAGCTTCCCGGGTCGGCTGATAGATCAACTGC |

| Crp-SphI | GAAGCATGCGCCGAAAGGTATAGCCAAGG |

| Crp-XbaI | GCGTCTAGAAAGTTAGGCAGCGATAACAAC |

| Crp-SalI | CTTGTCGACTTAACGGGTGCCGTAAAC |

| Primers for pET24-crp Construction | |

| Crp-NdeI | TAGTATCATATGGTTCTCGGTAAGCCACA |

| Crp-XhoI | TACTCGAGACGGGTGCCGTAAACGACGAT |

| Screening for pCD1 | |

| yscFPlus | ACACCATATGAGTAACTTCTCTGGATTTACG |

| yscFMinus | ATTCTCGAGTGGGAACTTCTGTAGGATG |

| Screening for pMT | |

| caf1Plus | AGTTCCGTTATCGCCATTGC |

| caf1Minus | GGTTAGATACGGTTACGGTTAC |

| Screening for pPst | |

| PstF | CAATCATATGTCAGATACAATGGTAGTG |

| PstR | CTCCTCGAGTTTTAACAATCCACTATC |

| Y. pestis Strains | LD50, CFU | |

|---|---|---|

| Mice | Guinea Pigs | |

| 231 | 3 | 3 |

| 231Δcrp | >107 | 2.1 × 108 |

| 231PBAD-crp | 5.6 × 104 | 4.6 × 107 |

| 231PBAD-crp(pPst¯) | >107 | >109 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dentovskaya, S.V.; Shaikhutdinova, R.Z.; Platonov, M.E.; Lipatnikova, N.A.; Mazurina, E.M.; Gapel’chenkova, T.V.; Kopylov, P.K.; Ivanov, S.A.; Trunyakova, A.S.; Vagaiskaya, A.S.; et al. Virulence Reduction in Yersinia pestis by Combining Delayed Attenuation with Plasmid Curing. Biomolecules 2026, 16, 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010040

Dentovskaya SV, Shaikhutdinova RZ, Platonov ME, Lipatnikova NA, Mazurina EM, Gapel’chenkova TV, Kopylov PK, Ivanov SA, Trunyakova AS, Vagaiskaya AS, et al. Virulence Reduction in Yersinia pestis by Combining Delayed Attenuation with Plasmid Curing. Biomolecules. 2026; 16(1):40. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010040

Chicago/Turabian StyleDentovskaya, Svetlana V., Rima Z. Shaikhutdinova, Mikhail E. Platonov, Nadezhda A. Lipatnikova, Elizaveta M. Mazurina, Tat’yana V. Gapel’chenkova, Pavel Kh. Kopylov, Sergei A. Ivanov, Alexandra S. Trunyakova, Anastasia S. Vagaiskaya, and et al. 2026. "Virulence Reduction in Yersinia pestis by Combining Delayed Attenuation with Plasmid Curing" Biomolecules 16, no. 1: 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010040

APA StyleDentovskaya, S. V., Shaikhutdinova, R. Z., Platonov, M. E., Lipatnikova, N. A., Mazurina, E. M., Gapel’chenkova, T. V., Kopylov, P. K., Ivanov, S. A., Trunyakova, A. S., Vagaiskaya, A. S., & Anisimov, A. P. (2026). Virulence Reduction in Yersinia pestis by Combining Delayed Attenuation with Plasmid Curing. Biomolecules, 16(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010040