NFS1 Plays a Critical Role in Regulating Ferroptosis Homeostasis

Abstract

1. Introduction

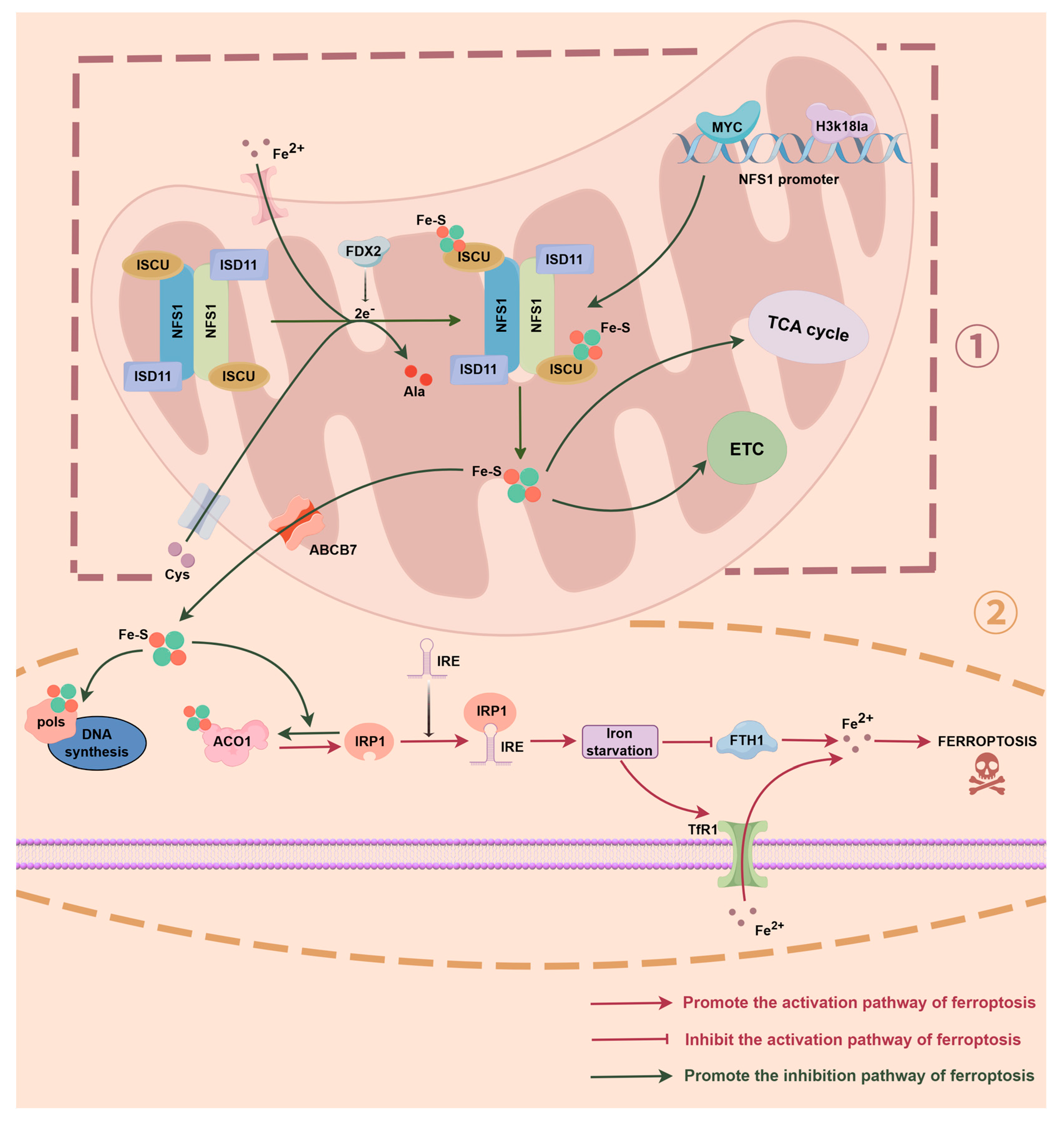

2. NFS1 and Iron Homeostasis Regulation

2.1. NFS1 Regulates the Fe-S–ACO1–IRP1 Axis

| Protein | Cellular Location | Function | NFS1 Role | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISCU | Mitochondria | Scaffold protein for Fe-S cluster assembly | Supply sulphur atoms for Fe-S cluster assembly | [18] |

| ABCB7 | Mitochondria | Fe-S cluster export to cytosol | Provide Fe-S cluster precursors for ABCB7 | [54,55] |

| ACO1/IRP1 | Cytosol | Iron regulation via IRE binding | Provide Fe-S clusters, determining the functional state of ACO1 | [34,36] |

| DNA polymerase | Nucleus | DNA replication fidelity | Generates Fe-S precursors for CIA-mediated assembly, indirectly supporting DNA polymerase | [56,57] |

| NDUFS1 | Mitochondria | Complex I subunit in electron transport chain | NFS1 initiates Fe-S cluster formation required for ETC function | [58] |

| FDX1/FDX2 | Mitochondria | Electron donors for Fe-S biosynthesis | NFS1-generated sulfur supports Fe-S cluster transfer | [59,60] |

| LIAS | Mitochondria | Lipoic acid synthesis | Supply sulphur to maintain the assembly of Fe-S clusters in LIAS | [61,62] |

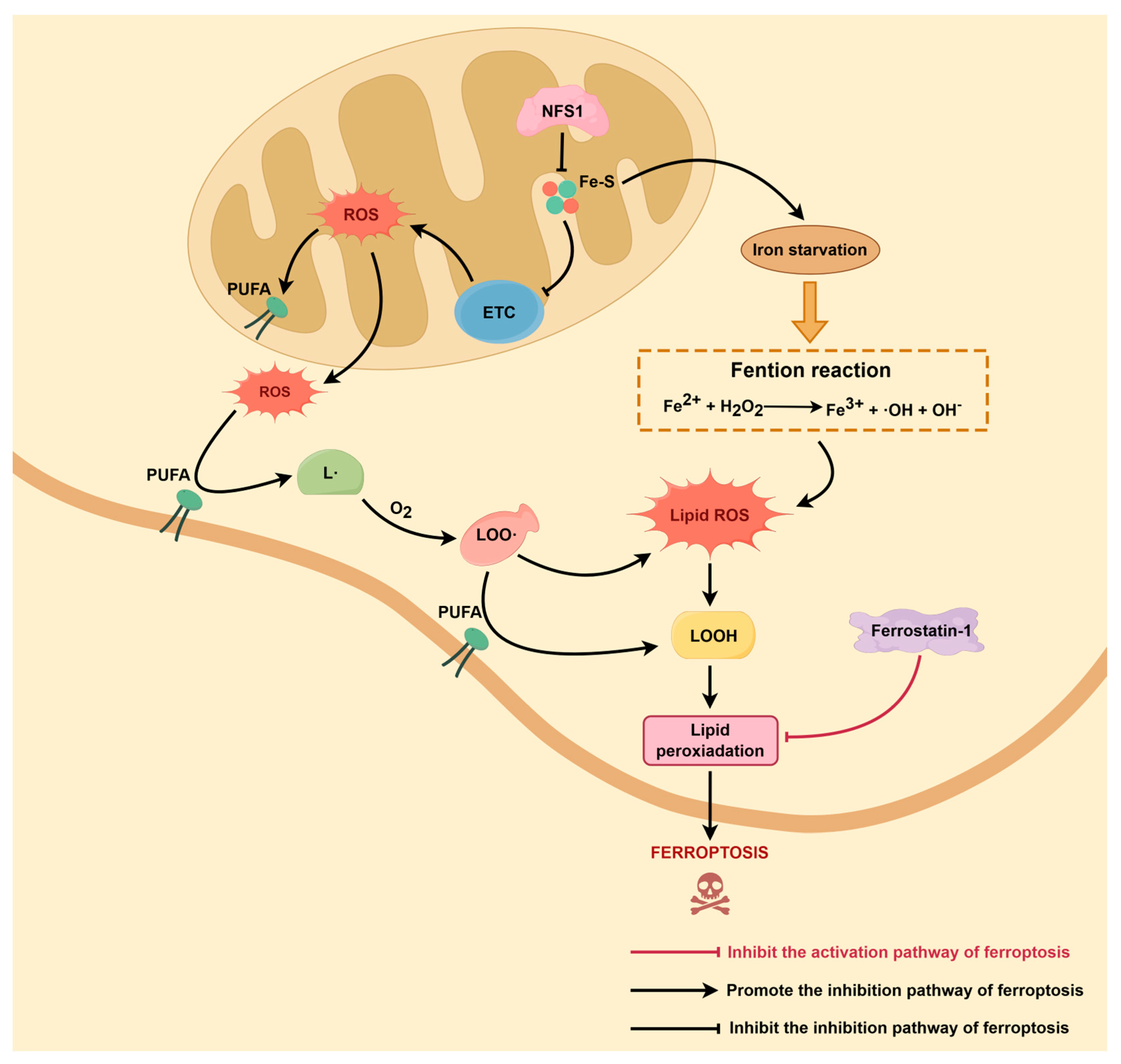

2.2. Free Iron Accumulation Drives the Fenton Reaction

3. NFS1 and ROS Plus Lipid Peroxidation

3.1. NFS1 Regulates Mitochondrial ROS Production

3.2. Lipid ROS Accumulation Is Key to the Ferroptosis Initiation

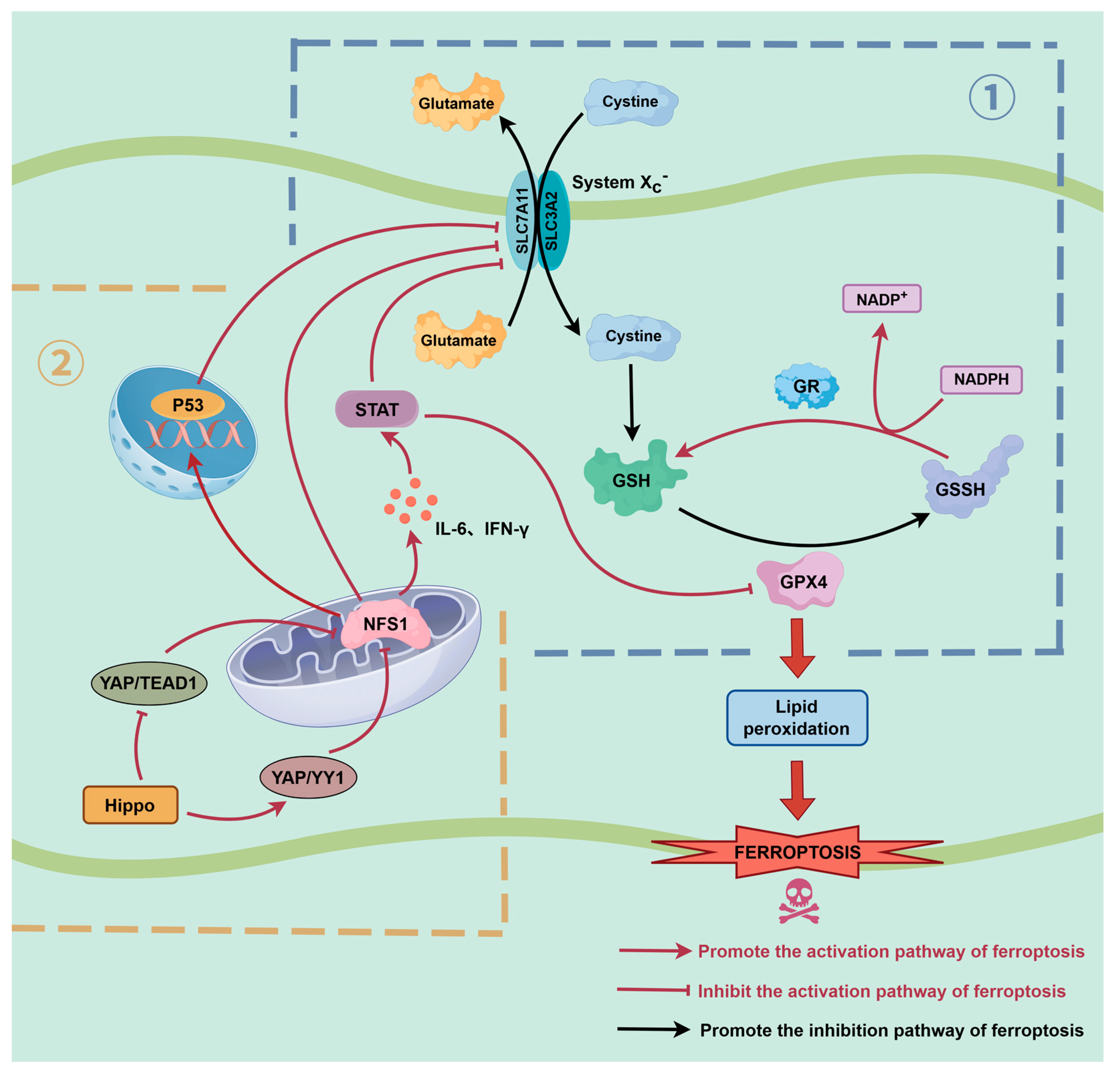

4. Interaction Between NFS1 and Key Ferroptosis Pathways

4.1. NFS1 Regulates the GPX4-GSH-Xc− System Axis

4.2. Cooperative Regulation of the NFS1 and p53 Pathways

4.3. NFS1-STST Axis

5. Research on NFS1 in Disease

5.1. Tumor

5.2. Cardiomyopathy

5.3. Mitochondrial Disorders

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| CIA | Cytosolic iron–sulfur assembly |

| COXPD19 | Compound oxidative phosphorylation deficiency type 19 |

| COXPD52 | Compound oxidative phosphorylation deficiency type 52 |

| CRC | Colorectal cancer |

| Cys | Cysteine |

| DHODH | Dihydroorotate dehydrogenase |

| ETC | Electron transport chain |

| Fe-S | Iron-sulfur |

| GC | Gastric cancer |

| Glu | Glutamate |

| GPX4 | Glutathione peroxidase 4 |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| HCC | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| HS | Heat stress |

| IMWA | Incomplete microwave ablation |

| IREs | Iron response elements |

| LC | Lung cancer |

| L• | Lipid radicals |

| LOO• | Lipid peroxy radicals |

| LOOH | Lipid peroxides |

| MWA | Microwave ablation |

| NFS1 | Cysteine desulfurase |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| O2− | Superoxide anion |

| ONOO− | Peroxynitrite |

| OXPHOS | Oxidative phosphorylation |

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

| PUFAs | Polyunsaturated fatty acids |

| RCD | Regulated cell death |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| TCA | Tricarboxylic acid cycle |

| YAP | Yes-associated protein |

| •NO2 | Nitrogen dioxide radical |

| •OH | Hydroxyl radicals |

References

- Dixon, S.J. Ferroptosis: Bug or Feature? Immunol. Rev. 2017, 277, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotchkiss, R.S.; Strasser, A.; McDunn, J.E.; Swanson, P.E. Cell Death. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 1570–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minami, J.K.; Morrow, D.; Bayley, N.A.; Fernandez, E.G.; Salinas, J.J.; Tse, C.; Zhu, H.; Su, B.; Plawat, R.; Jones, A.; et al. Cdkn2a Deletion Remodels Lipid Metabolism to Prime Glioblastoma for Ferroptosis. Cancer Cell 2023, 41, 1048–1060.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.W.; Lee, J.Y.; Oh, M.; Lee, E.W. An Integrated View of Lipid Metabolism in Ferroptosis Revisited via Lipidomic Analysis. Exp. Mol. Med. 2023, 55, 1620–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Conrad, M. Ferroptosis: When Metabolism Meets Cell Death. Physiol. Rev. 2025, 105, 651–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Zhang, G.; Hu, J.; Tian, Y.; Fu, X. Ferroptosis at the Nexus of Metabolism and Metabolic Diseases. Theranostics 2024, 14, 5826–5852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Kim, W.K.; Bae, K.H.; Lee, S.C.; Lee, E.W. Lipid Metabolism and Ferroptosis. Biology 2021, 10, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Q.; Liu, N.; Wu, J.; Chen, J.; Chen, X.; Peng, C. Mefloquine Enhances the Efficacy of Anti-Pd-1 Immunotherapy via Ifn-Γ-Stat1-Irf1-Lpcat3-Induced Ferroptosis in Tumors. J. Immunother. Cancer 2024, 12, e008554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, A.; Ichu, T.A.; Milosevich, N.; Melillo, B.; Schafroth, M.A.; Otsuka, Y.; Scampavia, L.; Spicer, T.P.; Cravatt, B.F. Lpcat3 Inhibitors Remodel the Polyunsaturated Phospholipid Content of Human Cells and Protect from Ferroptosis. ACS Chem. Biol. 2022, 17, 1607–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, J.; He, D.; Zhang, C.; Duan, C.; Li, B. Ferroptosis, a New Form of Cell Death: Opportunities and Challenges in Cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 12, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann Angeli, J.P.; Schneider, M.; Proneth, B.; Tyurina, Y.Y.; Tyurin, V.A.; Hammond, V.J.; Herbach, N.; Aichler, M.; Walch, A.; Eggenhofer, E.; et al. Inactivation of the Ferroptosis Regulator Gpx4 Triggers Acute Renal Failure in Mice. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014, 16, 1180–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarangelo, A.; Magtanong, L.; Bieging-Rolett, K.T.; Li, Y.; Ye, J.; Attardi, L.D.; Dixon, S.J. P53 Suppresses Metabolic Stress-Induced Ferroptosis in Cancer Cells. Cell Rep. 2018, 22, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Li, Q.; Ling, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Chu, K.; Xue, L.; Tao, S. Stat6 Inhibits Ferroptosis and Alleviates Acute Lung Injury via Regulating P53/Slc7a11 Pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Li, J.; Peng, H.; Zhang, M.; Wu, X.; Gui, F.; Li, W.; Ai, F.; Yu, B.; Liu, Y. Meteorin-Like/Meteorin-B Protects Lps-Induced Acute Lung Injury by Activating Sirt1-P53-Slc7a11 Mediated Ferroptosis Pathway. Mol. Med. 2023, 29, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Kon, N.; Li, T.; Wang, S.J.; Su, T.; Hibshoosh, H.; Baer, R.; Gu, W. Ferroptosis as a P53-Mediated Activity During Tumour Suppression. Nature 2015, 520, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Hickman, J.H.; Wang, S.J.; Gu, W. Dynamic Roles of P53-Mediated Metabolic Activities in Ros-Induced Stress Responses. Cell Cycle 2015, 14, 2881–2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, D.; Wang, M.; Wu, Y.; Tang, D.; Liu, X. Mitochondria as Multifaceted Regulators of Ferroptosis. Life Metab. 2022, 1, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montealegre, S.; Lebigot, E.; Debruge, H.; Romero, N.; Héron, B.; Gaignard, P.; Legendre, A.; Imbard, A.; Gobin, S.; Lacène, E.; et al. Fdx2 and Iscu Gene Variations Lead to Rhabdomyolysis with Distinct Severity and Iron Regulation. Neurol. Genet. 2022, 8, e648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Luo, M.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, J.; Gao, T.; Connell, D.O.; Yao, F.; Mu, C.; Cai, B.; Shang, Y.; et al. Nedd4 Ubiquitylates Vdac2/3 to Suppress Erastin-Induced Ferroptosis in Melanoma. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Du, T.; Yang, H.; Lei, L.; Guo, M.; Ding, H.F.; Zhang, J.; Wang, H.; Chen, X.; et al. Atf3 Promotes Erastin-Induced Ferroptosis by Suppressing System Xc−. Cell Death Differ. 2020, 27, 662–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Qi, Q.; Wu, N.; Wang, Y.; Feng, Q.; Jin, R.; Jiang, L. Aspirin Promotes Rsl3-Induced Ferroptosis by Suppressing Mtor/Srebp-1/Scd1-Mediated Lipogenesis in Pik3ca-Mutant Colorectal Cancer. Redox Biol. 2022, 55, 102426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Xie, F.; Mo, Y.; Qin, D.; Zheng, B.; Chen, L. Rsl3 Promotes Parp1 Apoptotic Functions by Distinct Mechanisms During Ferroptosis. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2025, 30, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Hou, W.; Song, X.; Yu, Y.; Huang, J.; Sun, X.; Kang, R.; Tang, D. Ferroptosis: Process and Function. Cell Death Differ. 2016, 23, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zilka, O.; Shah, R.; Li, B.; Friedmann Angeli, J.P.; Griesser, M.; Conrad, M.; Pratt, D.A. On the Mechanism of Cytoprotection by Ferrostatin-1 and Liproxstatin-1 and the Role of Lipid Peroxidation in Ferroptotic Cell Death. ACS Cent. Sci. 2017, 3, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Chen, X.; Ru, F.; Gan, Y.; Li, B.; Xia, W.; Dai, G.; He, Y.; Chen, Z. Liproxstatin-1 Attenuates Unilateral Ureteral Obstruction-Induced Renal Fibrosis by Inhibiting Renal Tubular Epithelial Cells Ferroptosis. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miotto, G.; Rossetto, M.; Di Paolo, M.L.; Orian, L.; Venerando, R.; Roveri, A.; Vučković, A.M.; Bosello Travain, V.; Zaccarin, M.; Zennaro, L.; et al. Insight into the Mechanism of Ferroptosis Inhibition by Ferrostatin-1. Redox Biol. 2020, 28, 101328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Guo, P.; Xie, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, G. Ferroptosis, a New Form of Cell Death, and Its Relationships with Tumourous Diseases. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2017, 21, 648–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.Y.; Dixon, S.J. Mechanisms of Ferroptosis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016, 73, 2195–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Yi, J.; Zhu, J.; Minikes, A.M.; Monian, P.; Thompson, C.B.; Jiang, X. Role of Mitochondria in Ferroptosis. Mol. Cell 2019, 73, 354–363.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Liu, Z.; Liu, J.; Li, Z.; Bao, Y.; Sun, X.; Zhao, W.; Zhou, A.; Wu, H. Ncoa4 Linked to Endothelial Cell Ferritinophagy and Ferroptosis:A Key Regulator Aggravate Aortic Endothelial Inflammation and Atherosclerosis. Redox Biol. 2025, 79, 103465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, Y.; Wei, C.; Sun, L.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J.; Luo, J.; Yu, X.; He, J.; Ge, H.; Liu, P. Melatonin Inhibits Ferroptosis and Delays Age-Related Cataract by Regulating Sirt6/P-Nrf2/Gpx4 and Sirt6/Ncoa4/Fth1 Pathways. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 157, 114048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Xie, L.; Hong, J.; Zhuang, Q.; Ren, L.; Li, X.; Zhang, C. Overexpression of Nfs1 Cysteine Desulphurase Relieves Sevoflurane-Induced Neurotoxicity and Cognitive Dysfunction in Neonatal Mice via Suppressing Oxidative Stress and Ferroptosis. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2024, 38, e70051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chafe, S.C.; Vizeacoumar, F.S.; Venkateswaran, G.; Nemirovsky, O.; Awrey, S.; Brown, W.S.; McDonald, P.C.; Carta, F.; Metcalfe, A.; Karasinska, J.M.; et al. Genome-Wide Synthetic Lethal Screen Unveils Novel Caix-Nfs1/Xct Axis as a Targetable Vulnerability in Hypoxic Solid Tumors. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabj0364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.F.; Hu, P.S.; Wang, Y.Y.; Tan, Y.T.; Yu, K.; Liao, K.; Wu, Q.N.; Li, T.; Meng, Q.; Lin, J.Z.; et al. Phosphorylated Nfs1 Weakens Oxaliplatin-Based Chemosensitivity of Colorectal Cancer by Preventing Panoptosis. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sewell, K.E.; Gola, G.F.; Pignataro, M.F.; Herrera, M.G.; Noguera, M.E.; Olmos, J.; Ramírez, J.A.; Capece, L.; Aran, M.; Santos, J. Direct Cysteine Desulfurase Activity Determination by Nmr and the Study of the Functional Role of Key Structural Elements of Human Nfs1. ACS Chem. Biol. 2023, 18, 1534–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, S.W.; Sviderskiy, V.O.; Terzi, E.M.; Papagiannakopoulos, T.; Moreira, A.L.; Adams, S.; Sabatini, D.M.; Birsoy, K.; Possemato, R. Nfs1 Undergoes Positive Selection in Lung Tumours and Protects Cells from Ferroptosis. Nature 2017, 551, 639–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Li, L.; Li, W.; Liu, K.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Z. Nfs1 Inhibits Ferroptosis in Gastric Cancer by Regulating the Stat3 Pathway. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2024, 56, 573–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Xie, H.; Li, J.; Huang, X.; Cai, Y.; Yang, R.; Yang, D.; Bao, W.; Zhou, Y.; Li, T.; et al. Histone Lactylation Drives Liver Cancer Metastasis by Facilitating Nsf1-Mediated Ferroptosis Resistance after Microwave Ablation. Redox Biol. 2025, 81, 103553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, G.; Hai, X.X.; Jia, L.Y.; Zhang, Y.J.; Ren, Y.J.; Pang, Z.D.; Wu, L.H.; Han, M.Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.J.; et al. Hippo Pathway Activation Mediates Cardiomyocyte Ferroptosis to Promote Dilated Cardiomyopathy Through Downregulating Nfs1. Redox Biol. 2025, 82, 103597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, S.; Tian, J.; Yang, F.; Chen, H.; Bai, S.; Kang, J.; Pang, K.; Huang, J.; Dong, M.; et al. Impaired Iron-Sulfur Cluster Synthesis Induces Mitochondrial Parthanatos in Diabetic Cardiomyopathy. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e2406695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ying, X.; Wang, Y.; Zou, Z.; Yuan, A.; Xiao, Z.; Geng, N.; Qiao, Z.; Li, W.; Lu, X.; et al. Hydrogen Sulfide Alleviates Mitochondrial Damage and Ferroptosis by Regulating Opa3-Nfs1 Axis in Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Cell Signal 2023, 107, 110655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ru, Q.; Li, Y.; Chen, L.; Wu, Y.; Min, J.; Wang, F. Iron Homeostasis and Ferroptosis in Human Diseases: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Prospects. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Shen, J.; Jiang, J.; Wang, F.; Min, J. Targeting Ferroptosis Opens New Avenues for the Development of Novel Therapeutics. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukumoto, J.; Lin, M.; Banday, M.M.; Patil, S.S.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Breitzig, M.; Soundararajan, R.; Galam, L.; Narala, V.R.; Johns, C.; et al. Aberrant Expression of Aco1 in Vasculatures Parallels Progression of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 890380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, A.D.; Bentley, R.E.; Archer, S.L.; Dunham-Snary, K.J. Mitochondrial Iron-Sulfur Clusters: Structure, Function, and an Emerging Role in Vascular Biology. Redox Biol. 2021, 47, 102164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinhilper, R.; Boß, L.; Freibert, S.A.; Schulz, V.; Krapoth, N.; Kaltwasser, S.; Lill, R.; Murphy, B.J. Two-Stage Binding of Mitochondrial Ferredoxin-2 to the Core Iron-Sulfur Cluster Assembly Complex. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 10559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, V.; Steinhilper, R.; Oltmanns, J.; Freibert, S.A.; Krapoth, N.; Linne, U.; Welsch, S.; Hoock, M.H.; Schünemann, V.; Murphy, B.J.; et al. Mechanism and Structural Dynamics of Sulfur Transfer During De Novo [2fe-2s] Cluster Assembly on Iscu2. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühlenhoff, U.; Balk, J.; Richhardt, N.; Kaiser, J.T.; Sipos, K.; Kispal, G.; Lill, R. Functional Characterization of the Eukaryotic Cysteine Desulfurase Nfs1p from Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 36906–36915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakai, Y.; Nakai, M.; Hayashi, H.; Kagamiyama, H. Nuclear Localization of Yeast Nfs1p Is Required for Cell Survival. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 8314–8320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovárová, J.; Horáková, E.; Changmai, P.; Vancová, M.; Lukeš, J. Mitochondrial and Nucleolar Localization of Cysteine Desulfurase Nfs and the Scaffold Protein Isu in Trypanosoma Brucei. Eukaryot. Cell 2014, 13, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, M.M.; Dosche, C.; Löhmannsröben, H.G.; Leimkühler, S. Dual Role of the Molybdenum Cofactor Biosynthesis Protein Mocs3 in Trna Thiolation and Molybdenum Cofactor Biosynthesis in Humans. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 17297–17307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marelja, Z.; Stöcklein, W.; Nimtz, M.; Leimkühler, S. A Novel Role for Human Nfs1 in the Cytoplasm: Nfs1 Acts as a Sulfur Donor for Mocs3, a Protein Involved in Molybdenum Cofactor Biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 25178–25185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, V.D.; Lill, R. Biogenesis of Cytosolic and Nuclear Iron-Sulfur Proteins and Their Role in Genome Stability. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1853, 1528–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Kim, J.K.; Kim, H. Abcb7 Simultaneously Regulates Apoptotic and Non-Apoptotic Cell Death by Modulating Mitochondrial Ros and Hif1α-Driven Nfκb Signaling. Oncogene 2020, 39, 1969–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maclean, A.E.; Sloan, M.A.; Renaud, E.A.; Argyle, B.E.; Lewis, W.H.; Ovciarikova, J.; Demolombe, V.; Waller, R.F.; Besteiro, S.; Sheiner, L. The Toxoplasma Gondii Mitochondrial Transporter Abcb7l Is Essential for the Biogenesis of Cytosolic and Nuclear Iron-Sulfur Cluster Proteins and Cytosolic Translation. mBio 2024, 15, e0087224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netz, D.J.; Stith, C.M.; Stümpfig, M.; Köpf, G.; Vogel, D.; Genau, H.M.; Stodola, J.L.; Lill, R.; Burgers, P.M.; Pierik, A.J. Eukaryotic DNA Polymerases Require an Iron-Sulfur Cluster for the Formation of Active Complexes. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011, 8, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ter Beek, J.; Parkash, V.; Bylund, G.O.; Osterman, P.; Sauer-Eriksson, A.E.; Johansson, E. Structural Evidence for an Essential Fe-S Cluster in the Catalytic Core Domain of DNA Polymerase ϵ. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 5712–5722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Yang, Z.; Wang, J.; Lu, W.; Wang, S.; Yang, M.; Sun, P.; Hu, W.; Yang, L.; Li, H. Naringin Attenuates Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury by Promoting Mitochondrial Translocation of Ndufs1 and Suppressing Cardiac Microvascular Endothelial Cell Ferroptosis. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2025, 145, 110019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, V.; Basu, S.; Freibert, S.A.; Webert, H.; Boss, L.; Mühlenhoff, U.; Pierrel, F.; Essen, L.O.; Warui, D.M.; Booker, S.J.; et al. Functional Spectrum and Specificity of Mitochondrial Ferredoxins Fdx1 and Fdx2. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2023, 19, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheftel, A.D.; Stehling, O.; Pierik, A.J.; Elsässer, H.P.; Mühlenhoff, U.; Webert, H.; Hobler, A.; Hannemann, F.; Bernhardt, R.; Lill, R. Humans Possess Two Mitochondrial Ferredoxins, Fdx1 and Fdx2, with Distinct Roles in Steroidogenesis, Heme, and Fe/S Cluster Biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 11775–11780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Chen, T.; Xu, C.; Yu, X.; Shi, J.; Yang, C.; Zhu, T. Iron Overload Exaggerates Renal Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury by Promoting Tubular Cuproptosis via Interrupting Function of Lias. Redox Biol. 2025, 86, 103795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendricks, A.L.; Wachnowsky, C.; Fries, B.; Fidai, I.; Cowan, J.A. Characterization and Reconstitution of Human Lipoyl Synthase (Lias) Supports Isca2 and Iscu as Primary Cluster Donors and an Ordered Mechanism of Cluster Assembly. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Minikes, A.M.; Jiang, X. Ferroptosis at the Intersection of Lipid Metabolism and Cellular Signaling. Mol. Cell 2022, 82, 2215–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujihara, K.M.; Zhang, B.Z.; Jackson, T.D.; Ogunkola, M.O.; Nijagal, B.; Milne, J.V.; Sallman, D.A.; Ang, C.S.; Nikolic, I.; Kearney, C.J.; et al. Eprenetapopt Triggers Ferroptosis, Inhibits Nfs1 Cysteine Desulfurase, and Synergizes with Serine and Glycine Dietary Restriction. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabm9427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Gan, H.; Wang, Y.; Jia, G.; Li, H.; Ma, Z.; Wang, J.; Shang, X.; Niu, W. Identification of a Selective Inhibitor of Human Nfs1, a Cysteine Desulfurase Involved in Fe-S Cluster Assembly, via Structure-Based Virtual Screening. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, X.; Cui, L.; Mi, Y.; Hu, J.; Cai, Z.; Tang, Q.; Yang, L.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Li, H.; et al. Ferroptosis in Cancer: Revealing the Multifaceted Functions of Mitochondria. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2025, 82, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sviderskiy, V.O.; Blumenberg, L.; Gorodetsky, E.; Karakousi, T.R.; Hirsh, N.; Alvarez, S.W.; Terzi, E.M.; Kaparos, E.; Whiten, G.C.; Ssebyala, S.; et al. Hyperactive Cdk2 Activity in Basal-Like Breast Cancer Imposes a Genome Integrity Liability That Can Be Exploited by Targeting DNA Polymerase E. Mol. Cell 2020, 80, 682–698.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.; Taylor, S.W.; Zhang, B.; Ghosh, S.S.; Capaldi, R.A. Oxidative Damage to Mitochondrial Complex I Due to Peroxynitrite: Identification of Reactive Tyrosines by Mass Spectrometry. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 37223–37230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewan, A.; Jain, C.; Das, M.; Tripathi, A.; Sharma, A.K.; Singh, H.; Malhotra, N.; Seshasayee, A.S.N.; Chakrapani, H.; Singh, A. Intracellular Peroxynitrite Perturbs Redox Balance, Bioenergetics, and Fe-S Cluster Homeostasis in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Redox Biol. 2024, 75, 103285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiti, A.K.; Spoorthi, B.C.; Saha, N.C.; Panigrahi, A.K. Mitigating Peroxynitrite Mediated Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Aged Rat Brain by Mitochondria-Targeted Antioxidant Mitoq. Biogerontology 2018, 19, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Wang, L.; Wu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Yao, Y.; Yang, H.; Hao, C. Lipid Metabolism in Ferroptosis: Mechanistic Insights and Therapeutic Potential. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1545339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rochette, L.; Dogon, G.; Rigal, E.; Zeller, M.; Cottin, Y.; Vergely, C. Lipid Peroxidation and Iron Metabolism: Two Corner Stones in the Homeostasis Control of Ferroptosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radi, R.; Beckman, J.S.; Bush, K.M.; Freeman, B.A. Peroxynitrite-Induced Membrane Lipid Peroxidation: The Cytotoxic Potential of Superoxide and Nitric Oxide. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1991, 288, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez de la Lastra, J.M.; Juan, C.A.; Plou, F.J.; Pérez-Lebeña, E. The Nitration of Proteins, Lipids and DNA by Peroxynitrite Derivatives-Chemistry Involved and Biological Relevance. Stresses 2022, 2, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manivarma, T.; Kapralov, A.A.; Samovich, S.N.; Tyurina, Y.Y.; Tyurin, V.A.; VanDemark, A.P.; Nowak, W.; Bayır, H.; Bahar, I.; Kagan, V.E.; et al. Membrane Regulation of 15lox-1/Pebp1 Complex Prompts the Generation of Ferroptotic Signals, Oxygenated Pes. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2023, 208, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, J.; Pan, X.; Wei, G.; Hua, Y. Research Progress of Glutathione Peroxidase Family (Gpx) in Redoxidation. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1147414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Lian, G.; Zhou, T.; Cai, Z.; Yang, S.; Li, W.; Cheng, L.; Ye, Y.; He, M.; Lu, J.; et al. Palmitoylation of Gpx4 via the Targetable Zdhhc8 Determines Ferroptosis Sensitivity and Antitumor Immunity. Nat. Cancer 2025, 6, 768–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Wang, H.; Liu, S.; Hao, M.; Luo, D.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, Y.; Nian, Y.; Zhang, L.; Chu, B.; et al. PPalmitoylation-Dependent Regulation of Gpx4 Suppresses Ferroptosis. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppula, P.; Zhang, Y.; Zhuang, L.; Gan, B. Amino Acid Transporter Slc7a11/Xct at the Crossroads of Regulating Redox Homeostasis and Nutrient Dependency of Cancer. Cancer Commun. 2018, 38, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Zheng, W.; Guan, J.; Liu, H.; Dan, Y.; Zhu, L.; Song, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Socs2-Enhanced Ubiquitination of Slc7a11 Promotes Ferroptosis and Radiosensitization in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cell Death Differ. 2023, 30, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Gao, W.; Sheng, Y.; Sun, J.; Wen, D. Resveratrol Drives Ferroptosis of Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cells Through Hsa-Mir-335-5p/Nfs1/Gpx4 Pathway in a Ros-Dependent Manner. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2023, 69, 131–137. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.; Yuan, H.; Zhang, C.; Han, D.; Wang, Y.; Feng, L. Induced Ferroptosis Pathway by Regulating Cellular Lipid Peroxidation with Peroxynitrite Generator for Reversing “Cold” Tumors. Small 2024, 20, e2404807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, X.; Hu, R.; Lu, E.; Luo, K.; Yan, X.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, M.; Sha, X. Inhalable Biomimetic Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid-Based Nanoreactors for Peroxynitrite-Augmented Ferroptosis Potentiate Radiotherapy in Lung Cancer. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2025, 23, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stockwell, B.R. Ferroptosis Turns 10: Emerging Mechanisms, Physiological Functions, and Therapeutic Applications. Cell 2022, 185, 2401–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Chu, B.; Yang, X.; Liu, Z.; Jin, Y.; Kon, N.; Rabadan, R.; Jiang, X.; Stockwell, B.R.; Gu, W. Ipla2β-Mediated Lipid Detoxification Controls P53-Driven Ferroptosis Independent of Gpx4. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.K.; Chen, T.J.; Tan, G.Y.T.; Chang, F.P.; Sridharan, S.; Yu, C.A.; Chang, Y.H.; Chen, Y.J.; Cheng, L.T.; Hwang-Verslues, W.W. Mex3a Mediates P53 Degradation to Suppress Ferroptosis and Facilitate Ovarian Cancer Tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2023, 83, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gu, W. P53 in Ferroptosis Regulation: The New Weapon for the Old Guardian. Cell Death Differ. 2022, 29, 895–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, R.; Wang, W.; Zhang, W. Ferroptosis and the Bidirectional Regulatory Factor P53. Cell Death Discov. 2023, 9, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Li, W.; Zhang, J.; Liu, K.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Z. Nfs1 as a Candidate Prognostic Biomarker for Gastric Cancer Correlated with Immune Infiltrates. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2024, 17, 3855–3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, H.Y.; Yang, W.; Liao, J.; Wang, H.H.; Wang, X.T.; Yan, W. Nfs1, Together with Fxn, Protects Cells from Ferroptosis and DNA Damage in Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Redox Biol. 2025, 87, 103878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershkovitz, T.; Kurolap, A.; Tal, G.; Paperna, T.; Mory, A.; Staples, J.; Brigatti, K.W.; Gonzaga-Jauregui, C.; Dumin, E.; Saada, A.; et al. A Recurring Nfs1 Pathogenic Variant Causes a Mitochondrial Disorder with Variable Intra-Familial Patient Outcomes. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2021, 26, 100699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.H.; Friederich, M.W.; Ellsworth, K.A.; Frederick, A.; Foreman, E.; Malicki, D.; Dimmock, D.; Lenberg, J.; Prasad, C.; Yu, A.C.; et al. Expanding the Phenotypic and Molecular Spectrum of Nfs1-Related Disorders That Cause Functional Deficiencies in Mitochondrial and Cytosolic Iron-Sulfur Cluster Containing Enzymes. Hum. Mutat. 2022, 43, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhan, S.M.; Wang, J.; Robinson, J.F.; Lahiry, P.; Siu, V.M.; Prasad, C.; Kronick, J.B.; Ramsay, D.A.; Rupar, C.A.; Hegele, R.A. Exome Sequencing Identifies Nfs1 Deficiency in a Novel Fe-S Cluster Disease, Infantile Mitochondrial Complex Ii/Iii Deficiency. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 2014, 2, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.C.; Friemel, M.; Marum, J.E.; Tucker, E.J.; Bruno, D.L.; Riley, L.G.; Christodoulou, J.; Kirk, E.P.; Boneh, A.; DeGennaro, C.M.; et al. Mutations in Lyrm4, Encoding Iron-Sulfur Cluster Biogenesis Factor Isd11, Cause Deficiency of Multiple Respiratory Chain Complexes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013, 22, 4460–4473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, P.P.; Srivastava, S.; Kumar, S.K.P.; Sinha, D.; D’Silva, P. Mapping Key Residues of Isd11 Critical for Nfs1-Isd11 Subcomplex Stability: Implications in the Development of Mitochondrial Disorder, Coxpd19. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 25876–25890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, A.C.; Bornhövd, C.; Prokisch, H.; Neupert, W.; Hell, K. The Nfs1 Interacting Protein Isd11 Has an Essential Role in Fe/S Cluster Biogenesis in Mitochondria. EMBO J. 2006, 25, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, C.; Fang, B.; Chen, X.; Wang, K.; Xin, H.; Wang, K.; Yang, S.M. Ferroptosis, a Therapeutic Target for Cardiovascular Diseases, Neurodegenerative Diseases and Cancer. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, F.; Lane, D.; Nguyen, T.P.M.; Bush, A.I.; Ayton, S. In Defence of Ferroptosis. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, R.J.; Dong, X.; Zhuang, H.W.; Pang, F.X.; Ding, S.C.; Li, N.; Mai, Y.X.; Zhou, S.T.; Wang, J.Y.; Zhang, J.F. Baicalin Induces Ferroptosis in Osteosarcomas through a Novel Nrf2/Xct/Gpx4 Regulatory Axis. Phytomedicine 2023, 116, 154881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Mi, Y.; Wang, Y.; Meng, Q.; Xu, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, D.; Wang, Y.; Liang, D.; Li, W.; et al. Loureirin C Inhibits Ferroptosis After Cerebral Ischemia Reperfusion Through Regulation of the Nrf2 Pathway in Mice. Phytomedicine 2023, 113, 154729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Wu, B.; Zhong, B.; Lin, L.; Ding, Y.; Jin, X.; Huang, Z.; Lin, M.; Wu, H.; Xu, D. Naringenin Alleviates Myocardial Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury by Regulating the Nuclear Factor-Erythroid Factor 2-Related Factor 2 (Nrf2) /System Xc−/ Glutathione Peroxidase 4 (Gpx4) Axis to Inhibit Ferroptosis. Bioengineered 2021, 12, 10924–10934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magtanong, L.; Ko, P.J.; To, M.; Cao, J.Y.; Forcina, G.C.; Tarangelo, A.; Ward, C.C.; Cho, K.; Patti, G.J.; Nomura, D.K.; et al. Exogenous Monounsaturated Fatty Acids Promote a Ferroptosis-Resistant Cell State. Cell Chem. Biol. 2019, 26, 420–432.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppula, P.; Zhuang, L.; Gan, B. Cystine Transporter Slc7a11/Xct in Cancer: Ferroptosis, Nutrient Dependency, and Cancer Therapy. Protein Cell 2021, 12, 599–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzarska, M.A.; Grochowina, I.; Soldek, J.; Jelen, M.; Schilke, B.; Marszalek, J.; Craig, E.A.; Dutkiewicz, R. During Fes Cluster Biogenesis, Ferredoxin and Frataxin Use Overlapping Binding Sites on Yeast Cysteine Desulfurase Nfs1. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 101570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zangari, J.; Stehling, O.; Freibert, S.A.; Bhattacharya, K.; Rouaud, F.; Serre-Beinier, V.; Maundrell, K.; Montessuit, S.; Ferre, S.M.; Vartholomaiou, E.; et al. D-Cysteine Impairs Tumour Growth by Inhibiting Cysteine Desulfurase Nfs1. Nat. Metab. 2025, 7, 1646–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, Z.; Shi, Z.; Cui, M.; Ma, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Jing, R.; Wang, J. Overexpression of the Ferroptosis-Related Gene, Nfs1, Corresponds to Gastric Cancer Growth and Tumor Immune Infiltration. Open Life Sci. 2025, 20, 20251135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, Y.; Tan, G.; Yang, X.; Lin, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xie, T.; Zhou, H.; Fang, J.; Zhao, Q.; et al. Iron-Sulphur Cluster Biogenesis Factor Lyrm4 Is a Novel Prognostic Biomarker Associated with Immune Infiltrates in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancer Cell Int. 2021, 21, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Wei, W.; Wu, D.; Huang, F.; Li, M.; Li, W.; Yin, J.; Peng, Y.; Lu, Y.; Zhao, Q.; et al. Blockade of Gch1/Bh4 Axis Activates Ferritinophagy to Mitigate the Resistance of Colorectal Cancer to Erastin-Induced Ferroptosis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 810327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, M.C.; Zhang, D.L.; Jeong, S.Y.; Kovtunovych, G.; Ollivierre-Wilson, H.; Noguchi, A.; Tu, T.; Senecal, T.; Robinson, G.; Crooks, D.R.; et al. Deletion of Iron Regulatory Protein 1 Causes Polycythemia and Pulmonary Hypertension in Mice Through Translational Derepression of Hif2α. Cell Metab. 2013, 17, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Xu, B.; Han, Q.; Zhou, H.; Xia, Y.; Gong, C.; Dai, X.; Li, Z.; Wu, G. Ferroptosis: A Novel Anti-Tumor Action for Cisplatin. Cancer Res. Treat. 2018, 50, 445–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Sui, S.; Wang, L.; Li, H.; Zhang, L.; Xu, S.; Zheng, X. Inhibition of Tumor Propellant Glutathione Peroxidase 4 Induces Ferroptosis in Cancer Cells and Enhances Anticancer Effect of Cisplatin. J. Cell. Physiol. 2020, 235, 3425–3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, G.; Zhang, Y.; Koppula, P.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Lin, S.H.; Ajani, J.A.; Xiao, Q.; Liao, Z.; Wang, H.; et al. The Role of Ferroptosis in Ionizing Radiation-Induced Cell Death and Tumor Suppression. Cell Res. 2020, 30, 146–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Springer, A.D.; Dowdy, S.F. Galnac-Sirna Conjugates: Leading the Way for Delivery of Rnai Therapeutics. Nucleic Acid. Ther. 2018, 28, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamberlain, K.; Riyad, J.M.; Weber, T. Cardiac Gene Therapy with Adeno-Associated Virus-Based Vectors. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2017, 32, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inagaki, K.; Fuess, S.; Storm, T.A.; Gibson, G.A.; McTiernan, C.F.; Kay, M.A.; Nakai, H. Robust Systemic Transduction with Aav9 Vectors in Mice: Efficient Global Cardiac Gene Transfer Superior to That of Aav8. Mol. Ther. 2006, 14, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, L.; Luo, P.; Chen, Q.; Liu, J.; Huang, Y.; Wu, C.; Pan, X.; Huang, Z. Fibroin Nanodisruptor with Ferroptosis-Autophagy Synergism Is Potent for Lung Cancer Treatment. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 664, 124582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, H.; Nakamura, H.; Fang, J. The Epr Effect for Macromolecular Drug Delivery to Solid Tumors: Improvement of Tumor Uptake, Lowering of Systemic Toxicity, and Distinct Tumor Imaging in Vivo. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2013, 65, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, S.; Na, J.; Liu, X.; Wu, P. Different Targeting Ligands-Mediated Drug Delivery Systems for Tumor Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debacker, A.J.; Voutila, J.; Catley, M.; Blakey, D.; Habib, N. Delivery of Oligonucleotides to the Liver with Galnac: From Research to Registered Therapeutic Drug. Mol. Ther. 2020, 28, 1759–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grommes, C.; Oxnard, G.R.; Kris, M.G.; Miller, V.A.; Pao, W.; Holodny, A.I.; Clarke, J.L.; Lassman, A.B. “Pulsatile” High-Dose Weekly Erlotinib for Cns Metastases from Egfr Mutant Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Neuro Oncol. 2011, 13, 1364–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, W.H.; Rouault, T.A. In-Gel Activity Assay of Mammalian Mitochondrial and Cytosolic Aconitases, Surrogate Markers of Compartment-Specific Oxidative Stress and Iron Status. Bio-Protoc. 2024, 14, e5126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, S.J.; Lemberg, K.M.; Lamprecht, M.R.; Skouta, R.; Zaitsev, E.M.; Gleason, C.E.; Patel, D.N.; Bauer, A.J.; Cantley, A.M.; Yang, W.S.; et al. Ferroptosis: An Iron-Dependent Form of Nonapoptotic Cell Death. Cell 2012, 149, 1060–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, F.; George, S.L.; Ning, J.; Li, L.; Huang, X. A Signature Enrichment Design with Bayesian Adaptive Randomization. J. Appl. Stat. 2021, 48, 1091–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Yee, D. I-Spy 2: A Neoadjuvant Adaptive Clinical Trial Designed to Improve Outcomes in High-Risk Breast Cancer. Curr. Breast Cancer Rep. 2019, 11, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Wang, X. A Metabolic Perspective on Cuproptosis. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tralongo, P.; Ballato, M.; Fiorentino, V.; Giordano, W.G.; Zuccalà, V.; Pizzimenti, C.; Bakacs, A.; Ieni, A.; Tuccari, G.; Fadda, G.; et al. Cuproptosis: A Review on Mechanisms, Role in Solid and Hematological Tumors, and Association with Viral Infections. Mediterr. J. Hematol. Infect. Dis. 2025, 17, e2025052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Chen, D.; Yao, L.; Sun, Y.; Li, D.; Le, J.; Dian, Y.; Zeng, F.; Chen, X.; Deng, G. The Molecular Mechanism and Therapeutic Landscape of Copper and Cuproptosis in Cancer. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sun, S.; Cao, H.; Li, X.; Liao, H. NFS1 Plays a Critical Role in Regulating Ferroptosis Homeostasis. Biomolecules 2026, 16, 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010032

Sun S, Cao H, Li X, Liao H. NFS1 Plays a Critical Role in Regulating Ferroptosis Homeostasis. Biomolecules. 2026; 16(1):32. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010032

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Siying, Hanwen Cao, Xuemei Li, and Hongfei Liao. 2026. "NFS1 Plays a Critical Role in Regulating Ferroptosis Homeostasis" Biomolecules 16, no. 1: 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010032

APA StyleSun, S., Cao, H., Li, X., & Liao, H. (2026). NFS1 Plays a Critical Role in Regulating Ferroptosis Homeostasis. Biomolecules, 16(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010032