The Xenopus Oocyte System: Molecular Dynamics of Maturation, Fertilization, and Post-Ovulatory Fate

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Power and Appeal of Xenopus Oocytes as a Model System

2.1. Why Xenopus laevis Has Been a Cornerstone in Developmental and Cell Biology

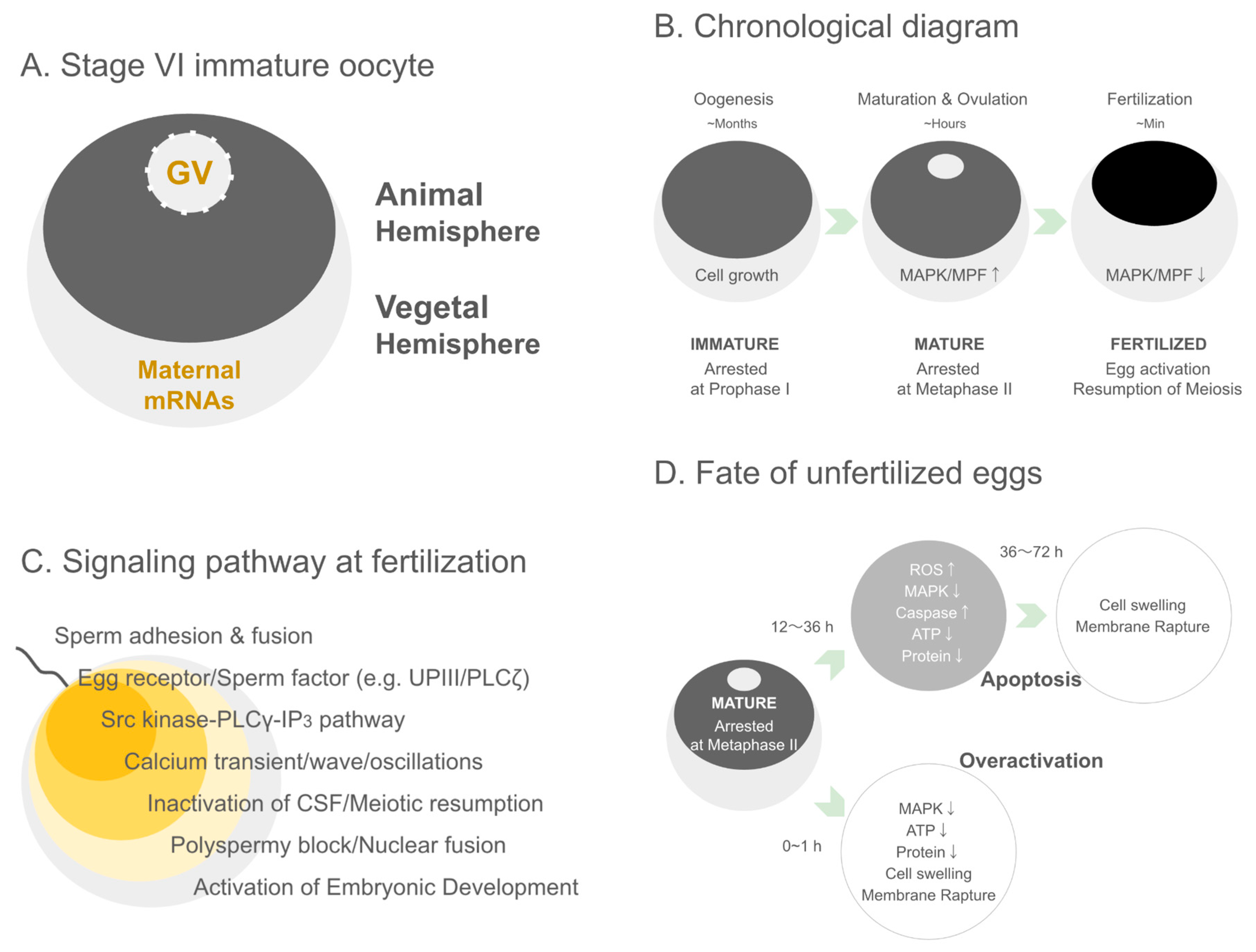

2.2. Cytological Architecture of Xenopus Oocytes

2.3. Overview of Research Techniques in Xenopus Oocytes

2.4. Limitations and Expanding Applications of Xenopus as a Model Organism—A Comparative Perspective with Xenopus tropicalis

| Feature | Xenopus laevis | Xenopus tropicalis | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome ploidy | Allotetraploid (2n = 36 × 2) | Diploid (2n = 20) | [6,66] |

| Genome size | ~3.1 Gb | ~1.7 Gb | [6,66] |

| Generation time | ~1 year | ~4–6 months | [5] |

| Embryonic development rate (23 °C in Xenopus laevis/26 °C in Xenopus tropicalis) | ~24 h to neurula | ~18 h to neurula | [2,51] |

| Oocyte diameter (Stage VI) | ~1.2 mm | ~0.7 mm | [7,50] |

| Ease of oocyte microinjection | Excellent (large oocytes) | Good (smaller oocytes) | [50,64] |

| Suitability for transgenesis/CRISPR | Limited by tetraploidy | High; efficient germline transmission | [32,69,70] |

| Genome resources and annotation | Well-established ESTs and partial genome | Fully sequenced, annotated genome | [66] |

| Use in developmental biology | Classic model for cell cycle, embryology, and oocyte maturation | Complementary model for forward genetics and genome editing | [3,5] |

| Main advantages | Large eggs, historical knowledge base, ease of manipulation | Genetic tractability, diploid genome, shorter generation time | [5] |

| Main limitations | Polyploid genome complicates genetics | Smaller size, limited historical datasets | [5,7] |

2.5. Summary

3. The Regulation of Oocyte Formation and Meiotic Arrest

3.1. Developmental Stages of Xenopus Oocytes and Meiotic Arrest at the GV Stage

3.2. The Role of MPF (Cdk1/CyclinB Complex)

3.3. GVBD and Ovulation-Inducing Hormones

3.4. Experimental Detection of MPF Activity In Vitro

3.5. Summary

4. Oocyte Maturation and Intracellular Signaling Networks

4.1. The Mos-MEK-MAPK Pathway and Activation of MPF

4.2. Regulation by 14-3-3 Proteins, Wee1/Myt1, and Cdc25

4.3. Transport Pathways, Localization Control, and Translational Regulation (CPEB and Poly(A) Tail)

4.4. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Oocyte Maturation

4.5. Summary

5. The Moment of Fertilization—Calcium Waves, Blocks, and Activation

5.1. Sperm Guidance and Adhesion: Mechanisms and Species Specificity

5.2. Sperm-Derived PLCζ and the IP3-Mediated Fertilization Calcium Wave

5.3. Sperm-Derived Trypsin-like Protease and Egg UPIII–Src Tyrosine Kinase Axis

5.4. Formation of the Fertilization Envelope, Vitelline Layer Modification, and Polyspermy Block Mechanisms

5.4.1. Cortical Granule Exocytosis and Fertilization Envelope Formation

5.4.2. Vitelline Layer Hardening and Egg Yolk Plug Consolidation

5.4.3. Functional Significance and Research Applications

5.5. Resumption of the Cell Cycle After Activation—Inactivation of CSF

5.6. Summary

6. Fertilization as a Trigger for Early Development and the Regulation of Activation Factors

6.1. Xenopus in the Context of Mosaic Versus Regulative Development

A Contextual View

6.2. Cytoplasmic Determinants and the Initiation of Mesoderm Induction

6.3. Germ Layer Differentiation Programs and the Onset of Translation

6.4. Sperm-Derived Centrosome and the Establishment of the First Cleavage Axis

6.5. Summary

7. Post-Ovulatory Fate of Oocytes—The Journey of Unfertilized Eggs

7.1. Apoptosis vs. Atresia—Natural Death Pathways of Unfertilized Eggs

Comparative Perspectives and Biological Implications

7.2. Caspase-Dependent and -Independent Pathways—Mitochondrial Contributions to Oocyte Demise

7.3. Post-Maturation Lifespan Limitation and Molecular Changes in Unfertilized Eggs

7.4. Overactivation—Necrosis-like Cell Death of Unfertilized Eggs Due to Mechanical Stress

7.5. Clinical Implications—Intersection with Reproductive Medicine

7.6. Summary

8. Cutting-Edge Research Utilizing Xenopus Eggs (mRNA Injection Screening, Genome Editing)

9. Conclusions: Unresolved Questions and Future Directions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gurdon, J.B.; Hopwood, N. The introduction of Xenopus laevis into developmental biology: Of empire, pregnancy testing and ribosomal genes. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2000, 44, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sive, H.L.; Grainger, R.M.; Harland, R.M. Early Development of Xenopus laevis: A Laboratory Manual; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Amaya, E. Xenomics. Genome Res. 2005, 15, 1683–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heasman, J. Patterning the early Xenopus embryo. Development 2006, 133, 1205–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harland, R.M.; Grainger, R.M. Xenopus research: Metamorphosed by genetics and genomics. Trends Genet. 2011, 27, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Session, A.M.; Uno, Y.; Kwon, T.; Chapman, J.A.; Toyoda, A.; Takahashi, S.; Fukui, A.; Hikosaka, A.; Suzuki, A.; Kondo, M.; et al. Genome evolution in the allotetraploid frog Xenopus laevis. Nature 2016, 538, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, P.; Conlon, F.; Furlow, J.D.; Horb, M.E. Expanding the genetic toolkit in Xenopus: Approaches and opportunities for human disease modeling. Dev. Biol. 2017, 426, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, D.W. CRegulation of cell polarity and RNA localization in vertebrate oocytes. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2013, 306, 127–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, M.L.; Messitt, T.J.; Mowry, K.L. Putting RNAs in the right place at the right time: RNA localization in the frog oocyte. Biol. Cell 2005, 97, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Pasquier, D.; Dupré, A.; Jessus, C. Unfertilized Xenopus eggs die by Bad-dependent apoptosis under the control of Cdk1 and JNK. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrell, J.E., Jr. Xenopus oocyte maturation: New lessons from a good egg. Bioessays 1999, 21, 833–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessus, C.; Ozon, R. How does Xenopus oocyte acquire its competence to undergo meiotic maturation? Biol. Cell. 2004, 96, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloc, M.; Dougherty, M.T.; Bilinski, S.; Chan, A.P.Y.; Brey, E.; King, M.L.; Patrick, C.W.; Etkin, L.D. Three-dimensional ultrastructural analysis of RNA distribution within germinal granules of Xenopus. Dev. Biol. 2002, 241, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masui, Y.; Clarke, H.J. Oocyte maturation. Int. Rev. Cytol. 1979, 57, 185–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.D. The induction of oocyte maturation: Transmembrane signaling events and regulation of the cell cycle. Development 1989, 107, 685–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busa, W.B.; Nuccitelli, R. An elevated free calcium wave follows fertilization in eggs of the frog, Xenopus laevis. J. Cell Biol. 1985, 100, 1325–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuccitelli, R. How do sperm activate eggs? Curr. Top Dev. Biol. 1991, 25, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cross, N.L.; Elinson, R.P. A fast block to polyspermy in frog eggs mediated by changes in the membrane potential. Dev. Biol. 1980, 75, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwao, Y. Egg activation in physiological polyspermy. Reproduction 2012, 144, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishimoto, T. Cell-cycle control during meiotic maturation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2003, 15, 654–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, J.L.; Wessel, G.M. Defending the zygote: Search for the ancestral animal block to polyspermy. Curr. Top Dev. Biol. 2006, 72, 1–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madgwick, S.; Jones, K.T. How eggs arrest at metaphase II: MPF stabilisation plus APC/C inhibition equals CSF. Cell Div. 2007, 2, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez, R.; Richter, J.D. Translational control by CPEB: A means to the end. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001, 2, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, H.E.; Meijer, H.A.; de Moor, C.H. Translational control by cytoplasmic polyadenylation in Xenopus oocytes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2008, 1779, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagata, N. Meiotic metaphase arrest in animal oocytes: Its mechanisms and biological significance. Trends Cell Biol. 1996, 6, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weeks, D.L.; Melton, D.A. A maternal mRNA localized to the vegetal hemisphere in Xenopus eggs codes for a growth factor related to TGF-β. Cell 1987, 51, 861–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Houston, D.W.; King, M.L.; Payne, C.; Wylie, C.; Heasman, J. The role of maternal VegT in establishing the primary germ layers in Xenopus embryos. Cell 1998, 94, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heasman, J.; Crawford, A.; Goldstone, K.; Garner-Hamrick, P.; Gumbiner, B.; McCrea, P.; Kintner, C.; Yoshida-Noro, C.; Wylie, C. Overexpression of cadherins and catenins inhibits dorsal mesoderm induction in early Xenopus embryos. Cell 1994, 79, 791–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wylie, C.; Kofron, M.; Payne, C.; Anderson, R.; Hosobuchi, M.; Joseph, E.; Heasman, J. Maternal β-catenin establishes a dorsal signal in early Xenopus embryos. Development 1996, 122, 2987–2996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moody, S.A. Fates of blastomeres of the 16-cell stage Xenopus embryo. Dev. Biol. 1987, 119, 560–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwkoop, P.D.; Faber, J. Normal Table of Xenopus laevis (Daudin); North-Holland Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Blitz, I.L.; Jcob Biesinger, J.; Xie, X.; Cho, K.W.Y. Biallelic genome modification in F(0) Xenopus tropicalis embryos using the CRISPR/Cas system. Genesis 2013, 51, 827–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.H.; Au, K.F.; Yablonovitch, A.L.; Wills, A.E.; Chuang, J.; Baker, J.C.; Wong, W.H.; Li, J.B. RNA sequencing reveals a diverse and dynamic repertoire of the Xenopus tropicalis transcriptome over development. Genome Res. 2013, 23, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, G.I.; Trbovich, A.M.; Gosden, R.G.; Tilly, J.L. Mitochondria and the death of oocytes. Nature 2000, 403, 500–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fissore, R.A.; Kurokawa, M.; Knott, J.; Zhang, M.; Smyth, J. Mechanisms underlying oocyte activation and postovulatory ageing. Reproduction 2002, 124, 745–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokmakov, A.A.; Sato, K. Egg Overactivation—An Overlooked Phenomenon of Gamete Death. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, T.; Aitken, R.J. Oxidative stress and ageing of the post-ovulatory oocyte. Reproduction 2013, 146, R217–R227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatone, C.; Amicarelli, F. The aging ovary—The poor granulosa cells. Fertil. Steril. 2013, 99, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masui, Y. From oocyte maturation to the in vitro cell cycle: The history of discoveries of Maturation-Promoting Factor (MPF) and Cytostatic Factor (CSF). Differentiation 2001, 69, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masui, Y. The elusive cytostatic factor in the animal egg. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000, 1, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nebreda, A.R.; Ferby, I. Regulation of the meiotic cell cycle in oocytes. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2000, 12, 666–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokmakov, A.A.; Stefanov, V.E.; Iwasaki, T.; Sato, K.; Fukami, Y. Calcium Signaling and Meiotic Exit at Fertilization in Xenopus Egg. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 18659–18676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloc, M.; Bilinski, S.; Etkin, L.D. The Balbiani Body and Germ Cell Determinants: 150 Years Later. Curr. Top Dev. Biol. 2004, 59, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupré, A.; Daldello, E.M.; Nairn, A.C.; Jessus, C.; Haccard, O. Phosphorylation of ARPP19 by protein kinase A prevents meiosis resumption in Xenopus oocytes. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurdon, J.B. Adult frogs derived from the nuclei of single somatic cells. Dev. Biol. 1962, 4, 256–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieschke, G.J.; Currie, P.D. Animal models of human disease: Zebrafish swim into view. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2007, 8, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, L.L.; Robledo, R.F.; Bult, C.J.; Churchill, G.A.; Paigen, B.J.; Svenson, K.L. The mouse as a model for human biology: A resource guide for complex trait analysis. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2007, 8, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grainger, R.M. Xenopus tropicalis as a model organism for genetics and genomics: Past, present, and future. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012, 917, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.L.; Strausberg, R.L.; Wagner, L.; Pontius, J.; Clifton, S.W.; Richardson, P. Genetic and genomic tools for Xenopus research: The NIH Xenopus initiative. Dev. Dyn. 2002, 225, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, J.N. Oogenesis in Xenopus laevis (Daudin). I. Stages of oocyte development in laboratory maintained animals. J. Morphol. 1972, 136, 153–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwkoop, P.D.; Faber, J. Normal Table of Xenopus laevis (Daudin): A Systematical and Chronological Survey of the Development from the Fertilized Egg till the End of Metamorphosis; Garland Science: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, R.A.; Jared, D.W.; Dumont, J.N.; Sega, M.W. Protein incorporation by isolated amphibian oocytes: III. Optimum incubation conditions. J. Exp. Zool. 1973, 184, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, R.A.; Misulovin, Z. Long-term growth and differentiation of Xenopus oocytes in a defined medium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1978, 75, 5534–5538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gard, D.L. Organization, nucleation, and acetylation of microtubules in Xenopus laevis oocytes: A study by confocal immunofluorescence microscopy. Dev. Biol. 1991, 143, 346–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klymkowsky, M.W.; Maynell, L.A. MPF-induced breakdown of cytokeratin filament organization in the maturing Xenopus oocyte depends upon the translation of maternal mRNAs. Dev. Biol. 1989, 134, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, H. Specification of embryonic axis and mosaic development in ascidians. Dev. Dyn. 2005, 233, 1177–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, P.; Wacaster, J.F. The amphibian gray crescent region--a site of developmental information? Dev. Biol. 1972, 28, 454–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heasman, J. Morpholino oligos: Making sense of antisense? Dev. Biol. 2002, 243, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurdon, J.B.; Melton, D.A. Nuclear reprogramming in cells. Science 2008, 322, 1811–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haccard, O.; Jessus, C.; Cayla, X.; Goris, J.; Merlevede, W.; Ozon, R. In vivo activation of a microtubule-associated protein kinase during meiotic maturation of the Xenopus oocyte. Eur. J. Biochem. 1990, 192, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokmakov, A.A.; Matsumoto, Y.; Isobe, T.; Sato, K. In Vitro Reconstruction of Xenopus Oocyte Ovulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokmakov, A.A.; Stefanov, V.E.; Sato, K. Dissection of the Ovulatory Process Using ex vivo Approaches. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 605379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dascal, N. The use of Xenopus oocytes for the study of ion channels. CRC Crit. Rev. Biochem. 1987, 22, 317–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stühmer, W. [16] Electrophysiologic recordings from Xenopus oocytes. Methods Enzymol. 1998, 293, 280–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stühmer, W. [19] Electrophysiological recording from Xenopus oocytes. Methods Enzymol. 1992, 207, 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellsten, U.; Harland, R.M.; Gilchrist, M.J.; Hendrix, D.; Jurka, J.; Kapitonov, V.; Ovcharenko, I.; Putnam, N.H.; Shu, S.; Taher, L.; et al. The genome of the Western clawed frog Xenopus tropicalis. Science 2010, 328, 633–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briggs, J.A.; Weinreb, C.; Wagner, D.E.; Megason, S.; Klein, A.M. The dynamics of gene expression in vertebrate embryogenesis at single-cell resolution. Science 2018, 360, eaar5780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briggs, J.A.; Weinreb, C.; Wagner, D.E.; Megason, S.; Peshkin, L.; Kirschner, M.W.; Klein, A.M. Xenopus Time Series Data: The Dynamics of Gene Expression in Vertebrate Embryogenesis at Single Cell Resolution. Harvard Xenopus Jamboree Dataset. 2018. Available online: https://kleintools.hms.harvard.edu/tools/currentDatasetsList_xenopus_v2.html (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Nakayama, T.; Blitz, I.L.; Fish, M.B.; Odeleye, A.O.; Manohar, S.; Cho, K.W.Y.; Grainger, R.M. Cas9-based genome editing in Xenopus tropicalis. Methods Enzymol. 2014, 546, 355–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakayama, T.; Fish, M.B.; Fisher, M.; Oomen-Hajagos, J.; Thomsen, G.H.; Grainger, R.M. Simple and efficient CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeted mutagenesis in Xenopus tropicalis. Genesis 2013, 51, 835–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautier, J.; Minshull, J.; Lohka, M.; Glotzer, M.; Hunt, T.; Maller, J.L. Cyclin is a component of maturation-promoting factor from Xenopus. Cell 1990, 60, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffré, M.; Martoriati, A.; Belhachemi, N.; Chambon, J.P.; Houliston, E.; Jessus, C. A critical balance between Cyclin B synthesis and Myt1 activity controls meiosis entry in Xenopus oocytes. Development 2011, 138, 3735–3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newport, J.; Kirschner, M. A major developmental transition in early Xenopus embryos: I. Characterization and timing of cellular changes at the midblastula stage. Cell 1982, 30, 675–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newport, J.; Kirschner, M. A major developmental transition in early Xenopus embryos: II. Control of the onset of transcription. Cell 1982, 30, 687–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halley-Stott, R.P.; Pasque, V.; Astrand, C.; Miyamoto, K.; Simeoni, I.; Jullien, J.; Gurdon, J.B. Mammalian nuclear transplantation to Germinal Vesicle stage Xenopus oocytes—A method for quantitative transcriptional reprogramming. Methods 2010, 51, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumagai, A.; Dunphy, W.G. Regulation of the cdc25 protein during the cell cycle in Xenopus extracts. Cell 1992, 70, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurse, P. Universal control mechanism regulating onset of M-phase. Nature 1990, 344, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohka, M.J.; Masui, Y. Formation in vitro of sperm pronuclei and mitotic chromosomes induced by amphibian ooplasmic components. Science 1983, 220, 719–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masui, Y.; Markert, C.L. Cytoplasmic control of nuclear behavior during meiotic maturation of frog oocytes. J. Exp. Zool. 1971, 177, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, M.J.; Glotzer, M.; Lee, T.H.; Philippe, M.; Kirschner, M.W. Cyclin activation of p34cdc2. Cell 1990, 63, 1013–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabbri, R.; Porcu, E.; Marsella, T.; Rocchetta, G.; Venturoli, S.; Flamigni, C. Human oocyte cryopreservation: New perspectives regarding oocyte survival. Hum. Reprod. 2001, 16, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meijer, L.; Arion, D.; Golsteyn, R.; Pines, J.; Brizuela, L.; Hunt, T.; Beach, D. Cyclin is a component of the sea urchin egg M-phase specific histone H1 kinase. EMBO J. 1989, 8, 2275–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrell, J.E., Jr.; Machleder, E.M. The biochemical basis of an all-or-none cell fate switch in Xenopus oocytes. Science 1998, 280, 895–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingolia, N. Cell cycle: Bistability is needed for robust cycling. Curr. Biol. 2005, 15, R961–R963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, A.W.; Kirschner, M.W. Cyclin synthesis drives the early embryonic cell cycle. Nature 1989, 339, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, D.O. Principles of CDK regulation. Nature 1995, 374, 131–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayaa, M.; Booth, R.A.; Sheng, Y.; Liu, X.J. The classical progesterone receptor mediates Xenopus oocyte maturation through a nongenomic mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 12607–12612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, L.B.; Kim, B.; Jahani, D.; Hammes, S.R. G protein βγ subunits inhibit nongenomic progesterone-induced signaling and maturation in Xenopus laevis oocytes: Evidence for a release of inhibition mechanism for cell cycle progression. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 41512–41520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Gong, H.; Thomsen, G.H.; Lennarz, W.J. Gamete Interactions in Xenopus laevis: Identification of Sperm Binding Glycoproteins in the Egg Vitelline Envelope. J. Cell Biol. 1997, 136, 1099–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maller, J.L.; Krebs, E.G. Progesterone-stimulated meiotic cell division in Xenopus oocytes. Induction by regulatory subunit and inhibition by catalytic subunit of adenosine 3′:5′-monophosphate-dependent protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1977, 252, 1712–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagata, N.; Oskarsson, M.; Copeland, T.; Brumbaugh, J.; Vande Woude, G.F. Function of c-mos proto-oncogene product in meiotic maturation in Xenopus oocytes. Nature 1988, 335, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunquist, B.J.; Maller, J.L. Under arrest: Cytostatic factor (CSF)-mediated metaphase arrest in vertebrate eggs. Genes. Dev. 2003, 17, 683–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppig, J.J. Oocyte control of ovarian follicular development and function in mammals. Reproduction 2001, 122, 829–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilchrist, R.B.; Thompson, J.G. Oocyte maturation: Emerging concepts and technologies to improve developmental potential in vitro. Theriogenology 2007, 67, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haccard, O.; Jessus, C. Redundant pathways for Cdc2 activation in Xenopus: Oocyte: Either cyclin B or Mos synthesis. EMBO Rep. 2006, 7, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.L.; Kikuchi, K.; Sun, Q.Y.; Schatten, H. Oocyte aging: Cellular and molecular changes, developmental potential, and reversal possibility. Hum. Reprod. Update 2009, 15, 573–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, A.W. Cell cycle extracts. Methods Cell Biol. 1991, 36, 581–605. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, J.V.; Vermeulen, M.; Santamaria, A.; Kumar, C.; Miller, M.L.; Jensen, L.J.; Gnad, F.; Cox, J.; Jensen, T.S.; Nigg, E.A.; et al. Quantitative phosphoproteomics reveals widespread full phosphorylation site occupancy during mitosis. Sci. Signal. 2010, 3, ra3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, B.; Tyson, J.J. Numerical analysis of a comprehensive model of M-phase control in Xenopus oocyte extracts and intact embryos. J. Cell Sci. 1993, 106 Pt 4, 1153–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomerening, J.R.; Sontag, E.D.; Ferrell, J.E. Building a cell cycle oscillator: Hysteresis and bistability in the activation of Cdc2. Nat. Cell Biol. 2003, 5, 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matten, W.T.; Copeland, T.D.; Ahn, N.G.; Vande Woude, G.F. Positive feedback between MAP kinase and Mos during Xenopus oocyte maturation. Dev. Biol. 1996, 179, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishimoto, T. MPF-based meiotic cell cycle control: Half a century of lessons from starfish oocytes. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 2018, 94, 180–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, J.A.; Kornbluth, S. Cdc25 and Wee1: Analogous opposites? Cell Div. 2007, 2, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackintosh, C. Dynamic interactions between 14-3-3 proteins and phosphoproteins regulate diverse cellular processes. Biochem. J. 2004, 381 Pt 2, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaffe, M.B.; Rittinger, K.; Volinia, S.; Caron, P.R.; Aitken, A.; Leffers, H.; Gamblin, S.J.; Smerdon, S.J.; Cantley, L.C. The structural basis for 14-3-3:phosphopeptide binding specificity. Cell 1997, 91, 961–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Winkler, K.; Yoshida, M.; Kornbluth, S. Maintenance of G2 arrest in the Xenopus oocyte: A role for 14-3-3–mediated inhibition of Cdc25 nuclear import. EMBO J. 1999, 18, 2174–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, B.C.; Weaver, J.S.; Ruderman, J.V. G2 arrest in Xenopus oocytes depends on phosphorylation of Cdc25 by protein kinase A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 16794–16799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, Y.; Tilly, J.L. Oocyte Apoptosis: Like Sand through an Hourglass. Dev. Biol. 1999, 213, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajo, N.; Yoshitome, S.; Iwashita, J.; Iida, M.; Uto, K.; Ueno, S.; Okamoto, K.; Sagata, N. Absence of Wee1 ensures the meiotic cell cycle in Xenopus oocytes. Genes Dev. 2000, 14, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izumi, T.; Maller, J.L. Phosphorylation and activation of Xenopus Cdc25 phosphatase in cell-free extracts. Mol. Biol. Cell 1995, 6, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, P.R.; Coleman, T.R.; Kumagai, A.; Dunphy, W.G. Myt1: A membrane-associated inhibitory kinase that phosphorylates Cdc2 on both threonine-14 and tyrosine-15. Science 1995, 270, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Richter, J.D. RINGO/cdk1 and CPEB mediate poly(A) tail stabilization and translational regulation by ePAB. Genes. Dev. 2007, 21, 2571–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, M.; Melton, D.A. Xwnt-11: A maternally expressed Xenopus wnt gene. Development 1993, 119, 1161–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betley, J.N.; Heinrich, B.; Vernos, I.; Sardet, C.; Prodon, F.; Deshler, J.O. Kinesin II mediates Vg1 mRNA transport in Xenopus oocytes. Curr. Biol. 2004, 14, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, J.A.; Kreiling, J.A.; Powrie, E.A.; Wood, T.R.; Mowry, K.L. Directional transport is mediated by a dynein-dependent step in an RNA localization pathway. PLoS Biol. 2013, 11, e1001551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshler, J.O.; Highett, M.I.; Schnapp, B.J. A highly conserved RNA-binding protein for cytoplasmic mRNA localization in vertebrates. Curr. Biol. 1998, 8, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Moor, C.H.; Richter, J.D. Cytoplasmic polyadenylation elements mediate masking and unmasking of cyclin B1 mRNA. EMBO J. 1999, 18, 2294–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, J.D. Cytoplasmic polyadenylation in development and beyond. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1999, 63, 446–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hake, L.E.; Richter, J.D. CPEB is a specificity factor that mediates cytoplasmic polyadenylation during Xenopus oocyte maturation. Cell 1994, 79, 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, D.C.; Ryan, K.; Manley, J.L.; Richter, J.D. Symplekin and xGLD-2 are required for CPEB-mediated cytoplasmic polyadenylation. Cell 2004, 119, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stebbins-Boaz, B.; Cao, Q.; de Moor, C.H.; Mendez, R.; Richter, J.D. Maskin is a CPEB-associated factor that transiently interacts with eIF-4E. Mol. Cell 1999, 4, 1017–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stebbins-Boaz, B.; Hake, L.E.; Richter, J.D. CPEB controls the cytoplasmic polyadenylation of cyclin, Cdk2 and c-mos mRNAs and is necessary for oocyte maturation in Xenopus. EMBO J. 1996, 15, 2582–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.L.; Evans, V.; Shen, S.; Richter, J.D. The nuclear experience of CPEB: Implications for RNA processing and translational control. RNA 2010, 16, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groisman, I.; Huang, Y.S.; Mendez, R.; Cao, Q.; Theurkauf, W.; Richter, J.D. CPEB, maskin, and cyclin B1 mRNA at the mitotic apparatus: Implications for local translational control of cell division. Cell 2000, 103, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneau, F.; Dupré, A.; Jessus, C.; Daldello, E.M. Translational Control of Xenopus Oocyte Meiosis: Toward the Genomic Era. Cells 2020, 9, 1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, W.; Moore, J.; Chen, K.; Lassaletta, A.D.; Yi, C.S.; Tyson, J.J.; Sible, J.C. Hysteresis drives cell-cycle transitions in Xenopus laevis oocytes and extracts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 975–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haccard, O.; Sarcevic, B.; Lewellyn, A.; Hartley, R.; Roy, L.; Izumi, T.; Erikson, E.; Maller, J.L. Induction of metaphase arrest in cleaving Xenopus embryos by MAP kinase. Science 1993, 262, 1262–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ookata, K.; Hisanaga, S.; Okumura, E.; Kishimoto, T. Association of p34cdc2/cyclin B complex with microtubules in starfish oocytes. J. Cell Sci. 1993, 105 Pt 4, 873–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Ferrell, J.E. A positive-feedback-based bistable ‘memory module’ that governs a cell fate decision. Nature 2003, 426, 460–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gard, D.L. Microtubule organization during maturation of Xenopus oocytes: Assembly and rotation of the meiotic spindles. Dev. Biol. 1992, 151, 516–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaigne, A.; Campillo, C.; Voituriez, R.; Gov, N.S.; Sykes Verlhac, M.H.; Terret, M.E. A soft cortex is essential for asymmetric spindle positioning in mouse oocytes. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013, 15, 958–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Dumollard, R.; Rossbach, A.; Lai, F.A.; Swann, K. Redistribution of mitochondria leads to bursts of ATP production during spontaneous mouse oocyte maturation. J. Cell Physiol. 2010, 224, 672–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, B.; Tyson, J.J. Design principles of biochemical oscillators. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 981–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrell, J.E., Jr. Feedback loops and reciprocal regulation: Recurring motifs in the systems biology of the cell cycle. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2013, 25, 676–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacquier, V.D.; Moy, G.W. Isolation of bindin: The protein responsible for adhesion of sperm to sea urchin eggs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1977, 74, 2456–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassarman, P.M. Mammalian fertilization: Molecular aspects of gamete adhesion, exocytosis, and fusion. Cell 1999, 96, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Anzi, B.; Chandler, D.E. A sperm chemoattractant is released from Xenopus egg jelly during spawning. Dev. Biol. 1998, 198, 366–375. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, J.H.; Xiang, X.; Ziegert, T.; Kittelson, A.; Rawls, A.; Bieber, A.L.; Chandler, D.E. Allurin, a 21-kDa sperm chemoattractant from Xenopus egg jelly, is related to mammalian sperm-binding proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 11205–11210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, J.H.; Chandler, D.E. Xenopus laevis egg jelly contains small proteins that are essential to fertilization. Dev. Biol. 1999, 210, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lishko, P.V.; Kirichok, Y. The role of Hv1 and CatSper channels in sperm activation. J. Physiol. 2010, 588 Pt 23, 4667–4672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lishko, P.V.; Botchkina, I.L.; Kirichok, Y. Progesterone activates the principal Ca2+ channel of human sperm. Nature 2011, 471, 387–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, D.; Navarro, B.; Perez, G.; Jackson, A.C.; Hsu, S.; Shi, Q.; Tilly, J.L.; Clapham, D.E. A sperm ion channel required for sperm motility and male fertility. Nature 2001, 413, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strünker, T.; Goodwin, N.; Brenker, C.; Kashikar, N.D.; Weyand, I.; Seifert, R.; Kaupp, U.B. The CatSper channel mediates progesterone-induced Ca+2+ influx in human sperm. Nature 2011, 471, 382–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darszon, A.; Guerrero, A.; Galindo, B.E.; Nishigaki, T.; Wood, C.D. Sperm-activating peptides in the regulation of ion fluxes, signal transduction and motility. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2008, 52, 595–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grey, R.D.; Wolf, D.P.; Hedrick, J.L. Formation and structure of the fertilization envelope in Xenopus laevis. Dev. Biol. 1974, 36, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubo, H.; Kotani, M.; Yamamoto, Y.; Hazato, T. Involvement of Sperm Proteases in the Binding of Sperm to the Vitelline Envelope in Xenopus laevis. Zoolog Sci. 2008, 25, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessel, G.M.; Wong, J.L. Cell surface changes in the egg at fertilization. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2009, 76, 942–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueda, Y.; Yoshizaki, N.; Iwao, Y. Acrosome reaction in sperm of the frog, Xenopus laevis: Its detection and induction by oviductal pars recta secretion. Dev. Biol. 2002, 243, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueda, Y.; Kubo, H.; Iwao, Y. Characterization of the acrosome reaction-inducing substance in Xenopus (ARISX) secreted from the oviductal pars recta onto the vitelline envelope. Dev. Biol. 2003, 264, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Wang, L.; Marques, S.; Ialy-Radio, C.; Barbaux, S.; Lefèvre, B.; Gourier, C.; Ziyyat, A. Oocyte ERM and EWI Proteins Are Involved in Mouse Fertilization. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 863729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, N.; Saito, T.; Wada, I. Noncanonical phagocytosis-like SEAL establishes mammalian fertilization. Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 115463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runge, K.E.; Evans, J.E.; He, Z.Y.; Gupta, S.; McDonald, K.L.; Stahlberg, H.; Primakoff, P.; Myles, D.G. Oocyte CD9 is enriched on the microvillar membrane and required for normal microvillar shape and distribution. Dev. Biol. 2007, 304, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, N.F.; Snell, W.J. Microvilli and Cell–Cell Fusion During Fertilization. Trends Cell Biol. 1998, 8, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.L.; Wessel, G.M. Extracellular matrix modifications at fertilization: Regulation of dityrosine crosslinking by transamidation. Development 2009, 136, 1835–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primakoff, P.; Myles, D.G. Penetration, adhesion, and fusion in mammalian sperm-egg interaction. Science 2002, 296, 2183–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stricker, S.A. Comparative Biology of Calcium Signaling during Fertilization and Egg Activation in Animals. Dev. Biol. 1999, 211, 157–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitaker, M. Calcium at fertilization and in early development. Physiol. Rev. 2006, 86, 25–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larman, M.G.; Saunders, C.M.; Carroll, J.; Lai, F.A.; Swann, K. Cell cycle-dependent Ca2+ oscillations in mouse embryos are regulated by nuclear targeting of PLCzeta. J. Cell Sci. 2004, 117 Pt 12, 2513–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saunders, C.M.; Larman, M.G.; Parrington, J.; Cox, L.J.; Royse, J.; Blayney, L.M.; Swann, K.; Lai, F.A. PLCζ: A sperm-specific trigger of Ca2+ oscillations in eggs and embryo development. Development 2002, 129, 3533–3544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouchi, Z.; Shikano, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Shirakawa, H.; Fukami, K.; Miyazaki, S. The role of EF-hand domains and C2 domain in regulation of enzymatic activity of phospholipase Czeta. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 21015–21021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoda, A.; Oda, S.; Shikano, T.; Kouchi, Z.; Awaji, T.; Shirakawa, H.; Kinoshita, K.; Miyazaki, S. Ca2+ oscillation-inducing phospholipase C zeta expressed in mouse eggs is accumulated to the pronucleus during egg activation. Dev. Biol. 2004, 268, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bainbridge, R.E.; Rosenbaum, J.C.; Sau, P.; Carlson, A.E. Genomic Insights into Fertilization: Tracing PLCZ1 Orthologs Across Amphibian Lineages. Genome Biol. Evol. 2025, 17, evaf052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwao, Y.; Shiga, K.; Shiroshita, A.; Yoshikawa, T.; Sakiie, M.; Ueno, T.; Ueno, S.; Ijiri, T.W.; Sato, K. The need of MMP-2 on the sperm surface for Xenopus fertilization: Its role in a fast electrical block to polyspermy. Mech. Dev. 2014, 134, 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watabe, M.; Hiraiwa, A.; Sakai, M.; Ueno, T.; Ueno, S.; Nakajima, K.; Yaoita, Y.; Iwao, Y. Sperm MMP-2 is indispensable for fast electrical block to polyspermy at fertilization in Xenopus tropicalis. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2021, 88, 744–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berridge, M.J.; Lipp, P.; Bootman, M.D. The versatility and universality of calcium signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000, 1, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kume, S.; Muto, A.; Aruga, J.; Nakagawa, T.; Michikawa, T.; Furuichi, T.; Nakade, S.; Okano, H.; Mikoshiba, K. The Xenopus IP3 receptor: Structure, function, and localization in oocytes and eggs. Cell 1993, 73, 555–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyazaki, S.; Yuzaki, M.; Nakada, K.; Shirakawa, H.; Nakanishi, S.; Nakade, S.; Mikoshiba, K. Block of calcium wave and cortical contraction by an antibody against inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor in fertilized hamster eggs. Science 1992, 257, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, G.; Goldbeter, A. Properties of intracellular Ca2+ waves generated by a model based on Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release. Biophys. J. 1994, 67, 2191–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friel, D.D.; Tsien, R.W. A caffeine- and ryanodine-sensitive Ca2+ store in bullfrog sympathetic neurons modulates the effects of Ca2+ entry on [Ca2+]i. J. Physiol. 1992, 450, 217–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulware, M.J.; Marchant, J.S. Nuclear pore disassembly from endoplasmic reticulum membranes promotes Ca2+ signalling competency. J. Physiol. 2008, 586, 2873–2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontanilla, R.A.; Nuccitelli, R. Characterization of the sperm-induced calcium wave in Xenopus eggs using confocal microscopy. Biophys. J. 1998, 75, 2079–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swann, K.; Lai, F.A. Egg Activation at Fertilization by a Soluble Sperm Protein. Physiol. Rev. 2016, 96, 127–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanassoulas, A.; Swann, K.; Lai, F.A.; Nomikos, M. Sperm factors and egg activation: The structure and function relationship of sperm PLCZ1. Reproduction 2022, 164, F1–F8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Carney, T.J. Protease-mediated activation of Par2 elicits calcium waves during zebrafish egg activation and blastomere cleavage. PLoS Biol. 2025, 23, e3003181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomikos, M.; Blayney, L.M.; Larman, M.G.; Campbell, K.; Rossbach, A.; Saunders, C.M.; Swann, K.; Lai, F.A. Sperm PLCζ: From structure to Ca2+ oscillations, egg activation and therapeutic potential. FEBS Lett. 2013, 587, 3609–3616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barresi, M.J.F.; Gilbert, S.F. Developmental Biology, 13th ed.; Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe, L.A. The fast block to polyspermy: New insight into a century-old problem. J. Gen. Physiol. 2018, 150, 1233–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitaker, M.; Swann, K. Lighting the fuse at fertilization. Development 1993, 117, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahbub Hasan, A.K.M.; Hashimoto, A.; Maekawa, Y.; Matsumoto, T.; Kushima, S.; Ijiri, T.W.; Fukami, Y.; Sato, K. The egg membrane microdomain-associated uroplakin III-Src system becomes functional during oocyte maturation and is required for bidirectional gamete signaling at fertilization in Xenopus laevis. Development 2014, 141, 1705–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahbub Hasan, A.K.M.; Fukami, Y.; Sato, K. Gamete membrane microdomains and their associated molecules in fertilization signaling. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2011, 78, 814–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahbub Hasan, A.K.; Sato, K.; Sakakibara, K.; Ou, Z.; Iwasaki, T.; Ueda, Y.; Fukami, Y. Uroplakin III a novel Src substrate in Xenopus egg rafts, is a target for sperm protease essential for fertilization. Dev. Biol. 2005, 286, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Tokmakov, A.A.; Iwasaki, T.; Fukami, Y. Tyrosine kinase-dependent activation of phospholipase Cγ is required for calcium transient in Xenopus egg fertilization. Dev. Biol. 2000, 224, 453–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizote, A.; Okamoto, S.; Iwao, Y. Activation of Xenopus eggs by proteases: Possible involvement of a sperm protease in fertilization. Dev. Biol. 1999, 208, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.T.; Liang, F.X.; Wu, X.R. Uroplakins as Markers of Urothelial Differentiation. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1999, 462, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Runft, L.L.; Jaffe, L.A.; Mehlmann, L.M. Egg activation at fertilization: Where it all begins. Dev. Biol. 2002, 245, 237–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K. Fertilization and Protein Tyrosine Kinase Signaling: Are They Merging or Emerging? In Reproductive and Developmental Strategies; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2018; pp. 569–589. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, K. Transmembrane Signal Transduction in Oocyte Maturation and Fertilization: Focusing on Xenopus laevis as a Model Animal. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 16, 114–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Yoshino, K.; Tokmakov, A.A.; Iwasaki, T.; Yonezawa, K.; Fukami, Y. Studying fertilization in cell-free extracts: Focusing on membrane/lipid raft functions and proteomics. Methods Mol. Biol. 2006, 322, 395–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilburn, D.B.; Swanson, W.J. From molecules to mating: Rapid evolution and biochemical studies of reproductive proteins. J. Proteomics 2016, 135, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, E.; Doe, B.; Goulding, D.; Wright, G.J. Juno is the egg Izumo receptor and is essential for mammalian fertilization. Nature 2014, 508, 483–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, N.; Ikawa, M.; Isotani, A.; Okabe, M. The immunoglobulin superfamily protein Izumo is required for sperm to fuse with eggs. Nature 2005, 434, 234–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.; Yamashita, M.; Noda, T.; Ikawa, M. The role of IZUMO1 complexes in mammalian fertilization: Insights from structural prediction and gene disruption. FEBS Lett. 2023, 597, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ohto, U.; Ishida, H.; Krayukhina, E.; Uchiyama, S.; Inoue, N.; Shimizu, T. Structure of IZUMO1-JUNO reveals sperm-oocyte recognition during mammalian fertilization. Nature 2016, 534, 566–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellerman, D.A.; Pei, J.; Gupta, S.; Snell, W.J.; Myles, D.G.; Primakoff, P. Izumo is part of a multiprotein family whose members form large complexes on mammalian sperm. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2009, 76, 1188–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satouh, Y.; Inoue, N.; Ikawa, M.; Okabe, M. Visualization of the moment of mouse sperm-egg fusion and dynamic localization of IZUMO1. J. Cell Sci. 2012, 125 Pt 21, 4985–4990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaji, K.; Oda, S.; Shikano, T.; Ohnuki, T.; Uematsu, Y.; Sakagami, J.; Tada, N.; Miyazaki, S.; Kudo, A. The gamete fusion process is defective in eggs of Cd9-deficient mice. Nat. Genet. 2000, 24, 279–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Naour, F.; Rubinstein, E.; Jasmin, C.; Prenant, M.; Boucheix, C. Severely reduced female fertility in CD9-deficient mice. Science 2000, 287, 319–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyado, K.; Yamada, G.; Yamada, S.; Hasuwa, H.; Nakamura, Y.; Ryu, F.; Suzuki, K.; Kosai, K.; Inoue, K.; Ogura, A.; et al. Requirement of CD9 on the egg plasma membrane for fertilization. Science 2000, 287, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, E.; Wright, G.J. Izumo meets Juno: Preventing polyspermy in fertilization. Cell Cycle 2014, 13, 2019–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalbi, M.; Barraud-Lange, V.; Ravaux, B.; Howan, K.; Rodriguez, N.; Soule, P.; Ndzoudi, A.; Boucheix, C.; Rubinstein, E.; Wolf, J.P.; et al. Binding of sperm protein Izumo1 and its egg receptor Juno drives Cd9 accumulation in the intercellular contact area prior to fusion during mammalian fertilization. Development 2014, 141, 3732–3739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deneke, V.E.; Blaha, A.; Lu, Y.; Suwita, J.P.; Draper, J.M.; Phan, C.S.; Panser, K.; Schleiffer, A.; Jacob, L.; Humer, T.; et al. A conserved fertilization complex bridges sperm and egg in vertebrates. Cell 2024, 187, 7066–7078.e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledford, H. AlphaFold reveals how sperm and egg hook up in intimate detail. Nat. News 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacak, P.; Kluger, C.; Vogel, V. Molecular dynamics of JUNO-IZUMO1 complexation suggests biologically relevant mechanisms in fertilization. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 20342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, J.L.; Wessel, G.M. Major components of a sea urchin block to polyspermy are structurally and functionally conserved. Evol. Dev. 2004, 6, 134–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bement, W.M.; Capco, D.G. Activators of protein kinase C trigger cortical granule exocytosis, cortical contraction, and cleavage furrow formation in Xenopus laevis oocytes and eggs. J. Cell Biol. 1989, 108, 885–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwao, Y.; Elinson, R.P. Control of sperm nuclear behavior in physiologically polyspermic newt eggs: Possible involvement of MPF. Dev. Biol. 1990, 142, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacquier, V.D. The quest for the sea urchin egg receptor for sperm. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 425, 583–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, J.L.; Créton, R.; Wessel, G.M. The oxidative burst at fertilization is dependent upon activation of the dual oxidase Udx1. Dev. Cell. 2004, 7, 801–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.L.; Wessel, G.M. Renovation of the egg extracellular matrix at fertilization. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2008, 52, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.L.; Wessel, G.M. Free-radical crosslinking of specific proteins alters the function of the egg extracellular matrix during fertilization. Development 2008, 135, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, L.A.; Cross, N.L. Electrical regulation of sperm-egg fusion. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1986, 48, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, W.J.; Vacquier, V.D. The rapid evolution of reproductive proteins. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2002, 3, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlisle, J.A.; Swanson, W.J. Molecular mechanisms and evolution of fertilization proteins. J. Exp. Zool. B Mol. Dev. Evol. 2021, 336, 652–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, S.D.; Schwab, M.S.; Taieb, F.E.; Lewellyn, A.L.; Maller, J.L. The critical role of the MAP kinase pathway in meiosis II in Xenopus oocytes is mediated by p90(Rsk). Curr. Biol. 2000, 10, 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoji, S.; Yoshida, N.; Amanai, M.; Ohgishi, M.; Fukui, T.; Fujimoto, S.; Nakano, Y.; Kajikawa, E.; Perry, A.C.F. Mammalian Emi2 mediates cytostatic arrest and transduces the signal for meiotic exit via Cdc20. EMBO J. 2006, 25, 834–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Maller, J.L. Calcium elevation at fertilization coordinates phosphorylation of XErp1/Emi2 by Plx1 and CaMK II to release metaphase arrest by cytostatic factor. Curr. Biol. 2005, 15, 1458–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stearns, T.; Kirschner, M. In vitro reconstitution of centrosome assembly and function: The central role of gamma-tubulin. Cell 1994, 76, 623–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conklin, E.G. The Organization and Cell-Lineage of the Ascidian Egg. J. Acad. Nat. Sci. Phila. 1905, 13 Pt 1, 1–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.B. Amphioxus, and the Mosaic Theory of Development. J. Morphol. 1893, 8, 579–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driesch, H. Entwicklungsmechanische Studien: I. Der Wert der beiden ersten Furchungszellen in der Echinidenentwicklung. Z. Für Wiss. Zool. 1892, 53, 160–184. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, S.F. Developmental Biology, 9th ed.; Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, J.Y.; Mowry, K.L. Xenopus Staufen is a component of a ribonucleoprotein complex containing Vg1 RNA and kinesin. Development 2004, 131, 3035–3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; King, M.L. Xenopus VegT RNA is localized to the vegetal cortex during oogenesis and encodes a novel T-box transcription factor involved in mesodermal patterning. Development 1996, 122, 4119–4129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spemann, H. Embryonic Development and Induction; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Spemann, H.; Mangold, H. Über Induktion von Embryonalanlagen durch Implantation artfremder Organisatoren. Roux’ Archiv für Entwicklungsmechanik der Organismen. Dev. Genes Evol. 1924, 100, 599–638. [Google Scholar]

- Astrow, S.; Holton, B.; Weisblat, D. Centrifugation redistributes factors determining cleavage patterns in leech embryos. Dev. Biol. 1987, 120, 270–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elinson, R.P.; Kao, K.R. The Location of Dorsal Information in Frog Early Development: (dorsoventral polarity/organizer/mesoderm/dorsal). Dev. Growth Differ. 1989, 31, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elinson, R.P.; Rowning, B. A transient array of parallel microtubules in frog eggs: Potential tracks for a cytoplasmic rotation that specifies the dorso-ventral axis. Dev. Biol. 1988, 128, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, J.P.; Gerhart, J.C. Subcortical rotation in Xenopus eggs: An early step in embryonic axis specification. Dev. Biol. 1987, 123, 526–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerhart, J.C. Mechanisms regulating pattern formation in the amphibian egg and early embryo. In Biological Regulation and Development; Goldberger, R.F., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1980; pp. 133–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, L.; Slack, J.M.W. Regional specification within the mesoderm of early embryos of Xenopus laevis. Development 1987, 100, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saka, Y.; Smith, J.C. Spatial and temporal patterns of cell division during early Xenopus embryogenesis. Dev. Biol. 2001, 229, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.C. A mesoderm-inducing factor is produced by Xenopus cell line. Development 1987, 99, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, C.E.; Old, R.W. Regulation of the early expression of the Xenopus nodal-related 1 gene, Xnr1. Development 2000, 127, 1221–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kofron, M.; Demel, T.; Xanthos, J.; Lohr, J.; Sun, B.; Sive, H.; Osada, S.; Wright, C.; Wylie, C.; Heasman, J. Mesoderm induction in Xenopus is a zygotic event regulated by maternal VegT via TGF-beta growth factors. Development 1999, 126, 5759–5770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorn, A.M.; Wells, J.M. Vertebrate endoderm development and organ formation. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2009, 25, 221–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthos, J.B.; Kofron, M.; Wylie, C.; Heasman, J. Maternal VegT is the initiator of a molecular network specifying endoderm in Xenopus laevis. Development 2001, 128, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, E.M.; Melton, D.A. Mutant Vg1 ligands disrupt endoderm and mesoderm formation in Xenopus embryos. Development 1998, 125, 2677–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomsen, G.H.; Melton, D.A. Processed Vg1 protein is an axial mesoderm inducer in Xenopus. Cell 1993, 74, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larabell, C.A.; Torres, M.; Rowning, B.A.; Yost, C.; Miller, J.R.; Wu, M.; Kimelman, D.; Moon, R.T. Establishment of the dorso-ventral axis in Xenopus embryos is presaged by early asymmetries in β-catenin that are modulated by the Wnt signaling pathway. J. Cell Biol. 1997, 136, 1123–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, S.; Steinbeisser, H.; Warga, R.M.; Hausen, P. β-catenin translocation into nuclei demarcates the dorsalizing centers in frog and fish embryos. Mech. Dev. 1996, 57, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwkoop, P.D. The formation of the mesoderm in urodelean amphibians. I. Induction by the endoderm. Wilhelm. Roux Arch. Entwickl. Mech. Org. 1969, 162, 341–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brannon, M.; Kimelman, D. Activation of Siamois by the Wnt pathway. Dev. Biol. 1996, 180, 344–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKendry, R.; Hsu, S.C.; Harland, R.M.; Grosschedl, R. LEF-1/TCF proteins mediate Wnt-inducible transcription from the Xenopus nodal-related 3 promoter. Dev. Biol. 1997, 192, 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Robertis, E.M. Spemann’s organizer and self-regulation in amphibian embryos. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006, 7, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harland, R.; Gerhart, J. Formation and function of Spemann’s Organizer. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 1997, 13, 611–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez, R.; Murthy, K.G.; Ryan, K.; Manley, J.L.; Richter, J.D. Phosphorylation of CPEB by Eg2 mediates the recruitment of CPSF into an active cytoplasmic polyadenylation complex. Mol. Cell 2000, 6, 1253–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Richter, J.D. Dissolution of the maskin–eIF4E complex by cytoplasmic polyadenylation and poly(A)-binding protein controls cyclin B1 mRNA translation and oocyte maturation. EMBO J. 2002, 21, 3852–3862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonoda, J.; Wharton, R.P. Recruitment of Nanos to hunchback mRNA by Pumilio. Genes. Dev. 1999, 13, 2704–2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, C.; Clements, D.; Friday, R.V.; Stott, D.; Woodland, H.R. Xsox17α and -β mediate endoderm formation in Xenopus. Cell 1997, 91, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, E.; Munoz-Sanjuan, I.; Altmann, C.R.; Vonica, A.; Brivanlou, A.H. Cell fate specification and competence by Coco, a maternal BMP, TGFβ and Wnt inhibitor. Development 2003, 130, 1381–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlange, T.; Andrée, B.; Arnold, H.H.; Brand, T. BMP2 is required for early heart development during a distinct time period. Mech. Dev. 2000, 91, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadros, W.; Lipshitz, H.D. The maternal-to-zygotic transition: A play in two acts. Development 2009, 136, 3033–3042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.T.; Bonneau, A.R.; Giraldez, A.J. Zygotic genome activation during the maternal-to-zygotic transition. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2014, 30, 581–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schatten, G. The centrosome and its mode of inheritance: The reduction of the centrosome during gametogenesis and its restoration during fertilization. Dev. Biol. 1994, 165, 299–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heald, R.; Tournebize, R.; Blank, T.; Sandaltzopoulos, R.; Becker, P.; Hyman, A.; Karsenti, E. Self-organization of microtubules into bipolar spindles around artificial chromosomes in Xenopus egg extracts. Nature 1996, 382, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilchik, M.V.; Black, S.D. The first cleavage plane and the embryonic axis are determined by separate mechanisms in Xenopus laevis: I. Independence in undisturbed embryos. Dev. Biol. 1988, 128, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhart, J.; Danilchik, M.; Doniach, T.; Roberts, S.; Rowning, B.; Stewart, R. Cortical rotation of the Xenopus egg: Consequences for the anteroposterior pattern of embryonic dorsal development. Development 1989, 107, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.R.; Rowning, B.A.; Larabell, C.A.; Yang-Snyder, J.A.; Bates, R.L.; Moon, R.T. Establishment of the dorsal–ventral axis in Xenopus embryos coincides with the dorsal enrichment of Dishevelled that is dependent on cortical rotation. J. Cell Biol. 1999, 146, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, C.; Kimelman, D. Move it or lose it: Axis specification in Xenopus. Development 2004, 131, 3491–3499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, C.R.; Hyman, A.A. Asymmetric cell division in C. elegans: Cortical polarity and spindle positioning. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2004, 20, 427–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houliston, E.; Elinson, R.P. Microtubules and cytoplasmic reorganisation in the frog egg. Curr. Top Dev. Biol. 1992, 26, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilly, J.L. Commuting the death sentence: How oocytes strive to survive. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001, 2, 838–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sible, J.C.; Anderson, J.A.; Lewelly, A.L.; Maller, J.L. Zygotic transcription is required to block a maternal program of apoptosis in Xenopus Embryos. Dev. Biol. 1997, 189, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stack, J.H.; Newport, J.W. Developmentally regulated activation of apoptosis early in Xenopus gastrulation results in cyclin A degradation during interphase of the cell cycle. Development 1997, 124, 3185–3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsueh, A.J.W.; Billig, H.; Tsafriri, A. Ovarian follicle atresia: A hormonally controlled apoptotic process. Endocr. Rev. 1994, 15, 707–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsafriri, A.; Braw, R.H. Experimental approaches to atresia in mammals. Oxf. Rev. Reprod. Biol. 1984, 6, 226–265. [Google Scholar]

- Durlinger, A.L.L.; Gruijters, M.J.G.; Kramer, P.; Karels, B.; Ingraham, H.A.; Nachtigal, M.W.; Uilenbroek, J.T.J.; Grootegoed, J.A.; Themmen, A.P.N. Anti-Müllerian hormone inhibits initiation of primordial follicle growth in the mouse ovary. Endocrinology 2002, 143, 1076–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martoriati, A.; Molinaro, C.; Marchand, G.; Fliniaux, I.; Marin, M.; Bodart, J.F.; Takeda-Uchimura, Y.; Lefebvre, T.; Dehennaut, V.; Cailliau, K. Follicular cells protect Xenopus oocyte from abnormal maturation via integrin signaling downregulation and O-GlcNAcylation control. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299, 104950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroemer, G.; Levine, B. Autophagic cell death: The story of a misnomer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 1004–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konduktorova, V.V.; Luchinskaya, N.N. Follicular cells of the amphibian ovary: Origin, structure, and functions. Ontogenez 2013, 44, 316–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, L.; Jan, S.Z.; Hamer, G.; van Pelt, A.M.; van der Stelt, I.; Keijer, J.; Teerds, K.J. Preantral follicular atresia occurs mainly through autophagy, while antral follicles degenerate mostly through apoptosis. Biol. Reprod. 2018, 99, 853–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidapur, S.K.; Nadkarni, V.B. Steroid-synthesizing cellular sites in amphibian ovary: A histochemical study. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 1974, 22, 459–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavera-Mendoza, L.; Ruby, S.; Brousseau, P.; Fournier, M.; Cyr, D.; Marcogliese, D. Response of the amphibian tadpole Xenopus laevis to atrazine: Gonadal effects including increased ovarian atresia. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2002, 21, 1264–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Peng, X.; Mei, S. Autophagy in ovarian follicular development and atresia. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 15, 726–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Kurokawa, M. Regulation of Oocyte Apoptosis: A View from Gene Knockout Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin-Moshier, Y.; Marchant, J.S. The Xenopus Oocyte: A Single-Cell Model for Studying Ca2+ signaling. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2013, 2013, pdb-top066308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluck, R.M.; Bossy-Wetzel, E.; Green, D.R.; Newmeyer, D.D. The Release of Cytochrome c from Mitochondria: A Primary Site for Bcl-2 Regulation of Apoptosis. Science 1997, 275, 1132–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluck, R.M.; Martin, S.J.; Hoffman, B.M.; Zhou, J.S.; Green, D.R.; Newmeyer, D.D. Cytochrome c Activation of CPP32-like Proteolysis Plays a Critical Role in a Xenopus Cell-free Apoptosis System. EMBO J. 1997, 16, 4639–4649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newmeyer, D.D.; Farschon, D.M.; Reed, J.C. Cell-free Apoptosis in Xenopus Egg Extracts: Inhibition by Bcl-2 and Requirement for an Organelle Fraction Enriched in Mitochondria. Cell 1994, 79, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Candé, C.; Cohen, I.; Daugas, E.; Ravagnan, L.; Larochette, N.; Zamzami, N.; Kroemer, G. Apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF): A novel caspase-independent death effector released from mitochondria. Biochimie 2002, 84, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joza, N.; Susin Sa Daugas, E.; Stanford, W.L.; Cho, S.K.; Li, C.Y.; Sasaki, T.; Elia, A.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Ravagnan, L.; Ferri, K.F.; et al. Essential role of the mitochondrial apoptosis-inducing factor in programmed cell death. Nature 2001, 410, 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Loo, G.; Schotte, P.; van Gurp, M.; Demol, H.; Hoorelbeke, B.; Gevaert, K.; Rodriguez, I.; Ruiz-Carrillo, A.; Vandekerckhove, J.; Declercq, W.; et al. Endonuclease G: A mitochondrial protein released in apoptosis and involved in caspase-independent DNA degradation. Cell Death Differ. 2001, 8, 1136–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, D.; Lee, I.W.; Yuen, W.S.; Carroll, J. Oocyte mitochondria—Key regulators of oocyte function and potential therapeutic targets for improving fertility. Biol. Reprod. 2022, 106, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goud, A.P.; Goud, P.T.; Diamond, M.P.; Gonik, B.; Abu-Soud, H.M. Reactive oxygen species and oocyte aging: Role of superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, and hypochlorous acid. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008, 44, 1295–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D.R.; Kroemer, G. The pathophysiology of mitochondrial cell death. Science 2004, 305, 626–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ježek, P. Mitochondrial Redox Regulations and Redox Biology of Mitochondria. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, M.; Gogvadze, V.; Orrenius, S.; Zhivotovsky, B. Mitochondria oxidative stress and cell death. Apoptosis 2007, 12, 913–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boumela, I.; Assou, S.; Aouacheria, A.; Haouzi, D.; Dechaud, H.; De Vos, J.; Handyside, A.; Hamamah, S. Involvement of BCL2 family members in the regulation of human oocyte and early embryo survival and death: Gene expression and beyond. Reproduction 2011, 141, 549–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cory, S.; Adams, J.M. The BCL-2 Family: Regulators of the Cellular Life-or-Death Switch. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2002, 2, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youle, R.J.; Strasser, A. The BCL-2 protein family: Opposing activities that mediate cell death. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.E.; Freel, C.D.; Kornbluth, S. Features of programmed cell death in intact Xenopus oocytes and early embryos revealed by near-infrared fluorescence and real-time monitoring. Cell Death Differ. 2010, 17, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokmakov, A.A.; Iguchi, S.; Iwasaki, T.; Fukami, Y. Unfertilized frog eggs die by apoptosis following meiotic exit. BMC Cell Biol. 2011, 12, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatone, C.; Amicarelli, F.; Carbone, M.C.; Monteleone, P.; Caserta, D.; Marci, R.; Artini, P.G.; Piomboni, P.; Focarelli, R. Cellular and molecular aspects of ovarian follicle ageing. Hum. Reprod. Update 2008, 14, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, A.E.; Caban, S.J.; McLaughlin Ea Roman, S.D.; Bromfield, E.G.; Nixon, B.; Sutherland, J.M. The Impact of Aging on Macroautophagy in the Pre-ovulatory Mouse Oocyte. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 691826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukamoto, S.; Kuma, A.; Murakami, M.; Kishi, C.; Yamamoto, A.; Mizushima, N. Autophagy is essential for preimplantation development of mouse embryos. Science 2008, 321, 117–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwari, M.; Prasad, S.; Tripathi, A.; Pandey, A.N.; Ali, I.; Singh, A.K.; Shrivastav, T.G.; Chaube, S.K. Apoptosis in Mammalian Oocytes: A Review. Apoptosis 2015, 20, 1019–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokmakov, A.A.; Teranishi, R.; Sato, K. Spontaneous Overactivation of Xenopus Frog Eggs Triggers Necrotic Cell Death. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokmakov, A.A.; Morichika, Y.; Teranishi, R.; Sato, K. Oxidative Stress-Induced Overactivation of Frog Eggs Triggers Calcium-Dependent Non-Apoptotic Cell Death. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokmakov, A.A.; Sato, K. Modulation of Intracellular ROS and Senescence-Associated Phenotypes of Xenopus Oocytes and Eggs by Selective Antioxidants. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokmakov, A.A.; Awamura, M.; Sato, K. Biochemical hallmarks of oxidative stress-induced overactivation of Xenopus eggs. Biomed. Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 7180540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calonge, M. Oocyte Collection for IVF. In Principles of IVF Laboratory Practice: Laboratory Set-Up, Training and Daily Operation; Montag, M.H.M., Morbeck, D.E., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023; Chapter 17; pp. 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trounson, A.; Gosden, R. Biology and Pathology of the Oocyte: Role in Fertility, Medicine and Nuclear Reprogramming; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Trounson, A.; Gosden, R. Biology and Pathology of the Oocyte: Its Role in Fertility and Reproductive Medicine; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003; pp. 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, M.; Franciosi, F. Acquisition of oocyte competence to develop as an embryo: Integrated nuclear and cytoplasmic events. Hum. Reprod. Update 2018, 24, 245–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canosa, S.; Maggiulli, R.; Cimadomo, D.; Innocenti, F.; Fabozzi, G.; Gennarelli, G.; Revelli, A.; Bongioanni, F.; Vaiarelli, A.; Ubaldi, F.M.; et al. Cryostorage management of reproductive cells and tissues in ART: Status, needs, opportunities and potential new challenges. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2023, 47, 103252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krisher, R.L. The effect of oocyte quality on development. J. Anim. Sci. 2004, 82, E14–E23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Blerkom, J. Mitochondrial function in the human oocyte and embryo and their role in developmental competence. Mitochondrion 2011, 11, 797–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baust, J.G.; Gao, D.; Baust, J.M. Cryopreservation: An emerging paradigm change. Organogenesis 2009, 5, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baust, J.G.; Baust, J.M. Viability and functional assays used to assess preservation efficacy: The multiple endpoint/tier approach. In Advances in Biopreservation; Baust, G., Baust, M., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006; Chapter 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schatten, H.; Sun, Q.Y. Centrosome dynamics during mammalian oocyte maturation with a focus on meiotic spindle formation. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2011, 78, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moody, S.A. Microinjection of mRNAs and Oligonucleotides. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2018, 12, pdb.prot097261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnizler, K.; Küster, M.; Methfessel, C.; Fejtl, M. The roboocyte: Automated cDNA/mRNA injection and subsequent TEVC recording on Xenopus oocytes in 96-well microtiter plates. Recept. Channels 2003, 9, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya, D.; Marfo, C.A.; Li, D.; Lane, M.; Khokha, M.K. CRISPR/Cas9: An inexpensive, efficient loss-of-function tool to screen human disease genes in Xenopus. Dev. Biol. 2015, 408, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Y.; Ma, L.; Guo, Q.; E, W.; Fang, X.; Yang, L.; Ruan, F.; Wang, J.; Zhang, P.; Sun, Z.; et al. Cell landscape of larval and adult Xenopus laevis at single-cell resolution. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sato, K.-I. The Xenopus Oocyte System: Molecular Dynamics of Maturation, Fertilization, and Post-Ovulatory Fate. Biomolecules 2026, 16, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010022

Sato K-I. The Xenopus Oocyte System: Molecular Dynamics of Maturation, Fertilization, and Post-Ovulatory Fate. Biomolecules. 2026; 16(1):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010022

Chicago/Turabian StyleSato, Ken-Ichi. 2026. "The Xenopus Oocyte System: Molecular Dynamics of Maturation, Fertilization, and Post-Ovulatory Fate" Biomolecules 16, no. 1: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010022

APA StyleSato, K.-I. (2026). The Xenopus Oocyte System: Molecular Dynamics of Maturation, Fertilization, and Post-Ovulatory Fate. Biomolecules, 16(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010022