Development and Characterization of Cannabidiol Self-Emulsifying Drug Delivery System: In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. HPLC Analytical Method

2.2.2. Screening of CBD Solubility in Different Excipients

2.2.3. Pseudo-Ternary Diagram Construction

2.2.4. Emulsification Time

2.2.5. Particle Size and Polydispersity Analysis

2.2.6. Drug Loading

2.2.7. Thermodynamic Stress Testing for Kinetic Stability Evaluation

2.2.8. In Vitro Release

2.2.9. In Vitro Digestion

2.2.10. In Vivo Bioavailability Study

Plasma Samples Preparation

Plasma Sample Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

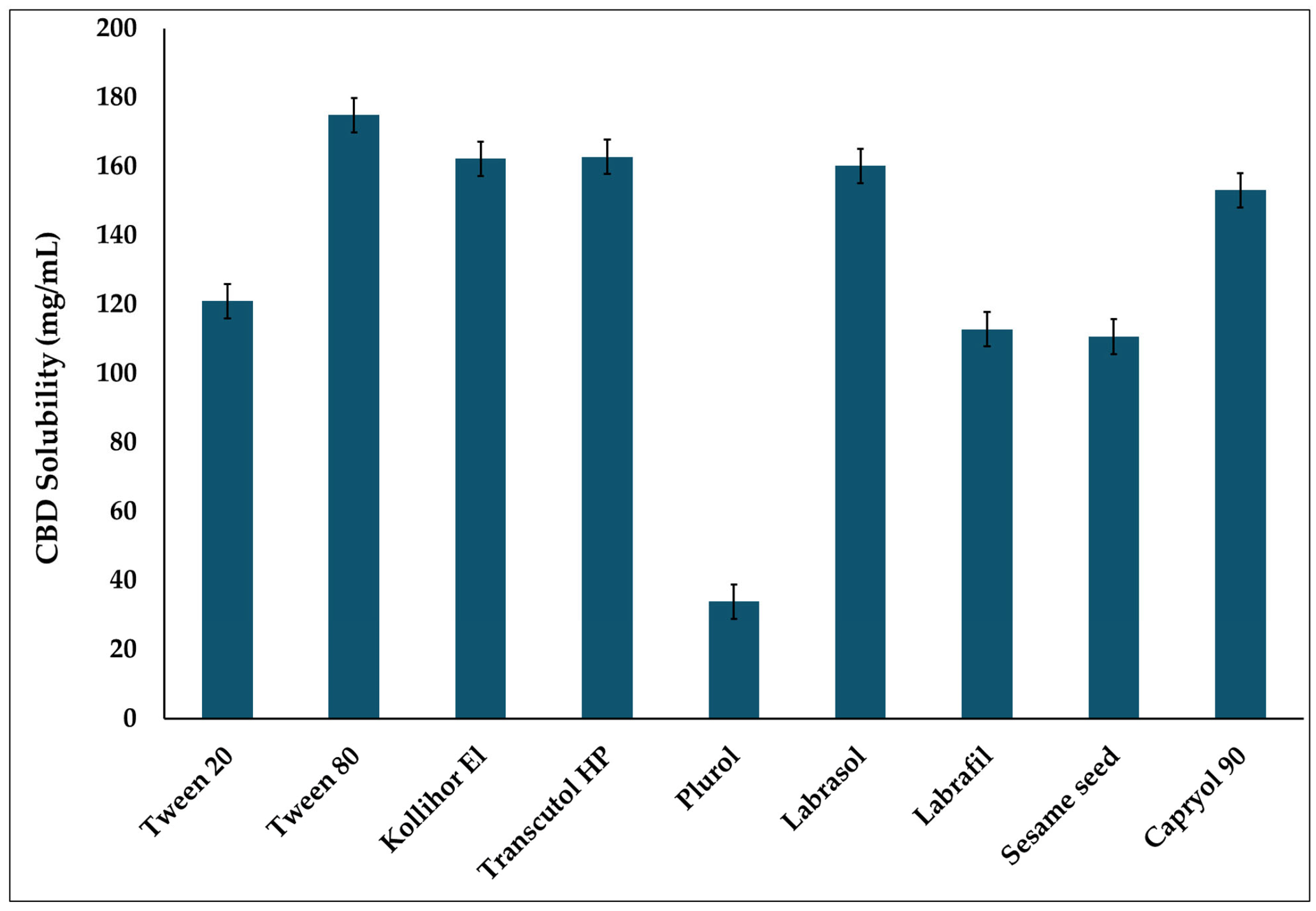

3.1. Solubility Study

3.2. Pseudo-Ternary Diagram

3.3. Emulsification Time

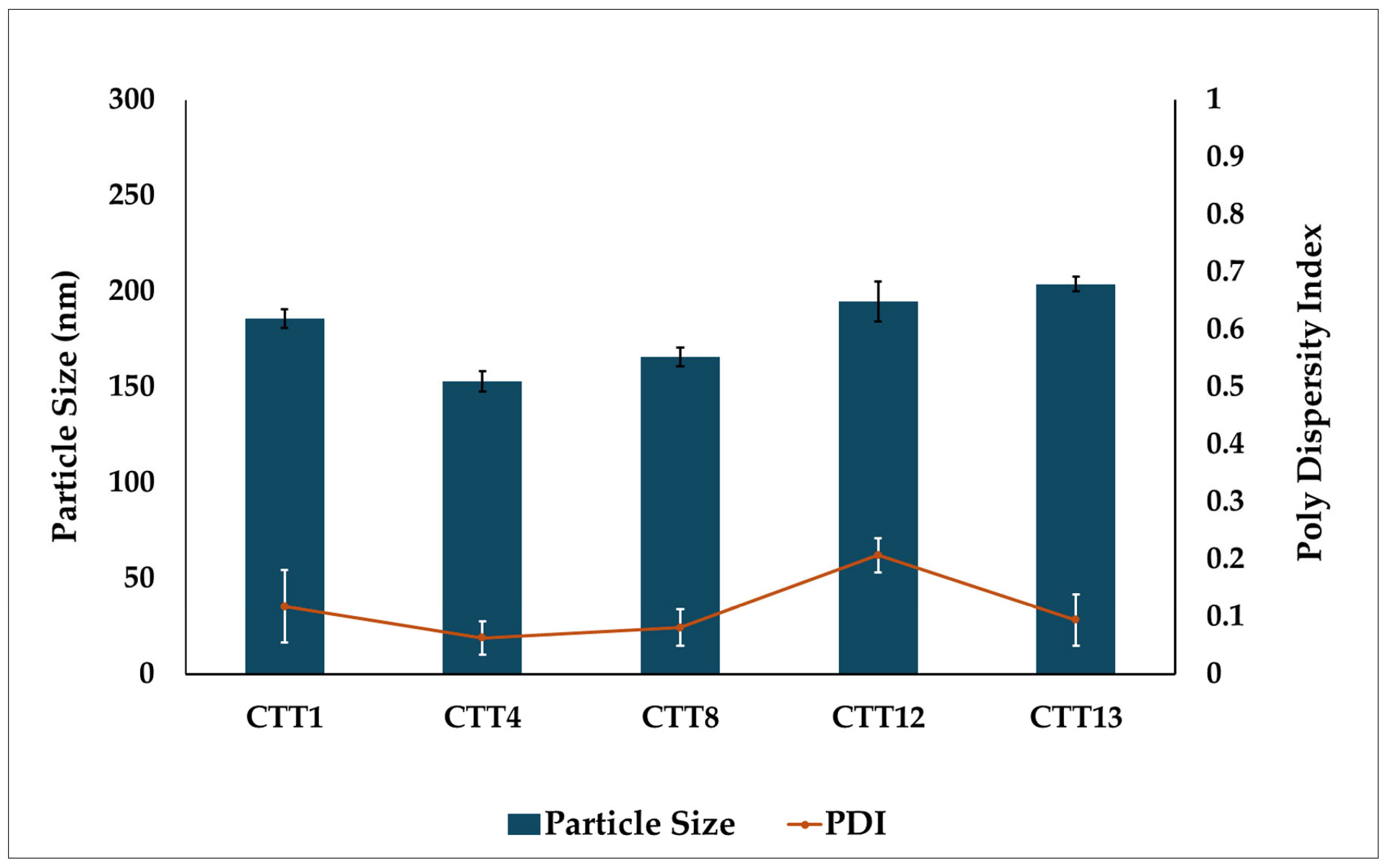

3.4. Particle Size and PDI

3.5. Drug Loading

3.6. Kinetic Stability

3.7. In Vitro Drug Release

3.8. In Vitro Digestion

3.9. In Vivo Bioavailability Data

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CBD | Cannabidiol |

| THC | Tetrahydrocannabinol |

| CB | Cannabinoid receptor |

| ECS | Endocannabinoid system |

| FAAH | Fatty acid amide hydrolase |

| LBDDS | Lipid based drug delivery system |

| GIT | Gastrointestinal tract |

| P-gp | P-glycoprotein |

| SEDDS | Self-emulsifying drug delivery system |

| PS | Particle size |

| PDI | Polydispersity index |

| ET | Emulsification time |

| PVDF | Polyvinylidene fluoride |

| IACUC | Institutional animal care and use committee |

| UPLA | Ultra-performance liquid chromatography |

| MRM | Multiple reaction monitoring |

| LLOQ | Lowest limit of quantification |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| MTC | Medium-chain triglyceride |

| HLB | Hydrophilic lipophilic balance |

References

- Pisanti, S.; Bifulco, M. Medical Cannabis: A plurimillennial history of an evergreen. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 8342–8351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shaughnessy, W.B. On the preparations of the Indian hemp, or Gunjah: Cannabis indica their effects on the animal system in health, and their utility in the treatment of tetanus and other convulsive diseases. Prov. Med. J. Retrosp. Med. Sci. 1843, 5, 363. [Google Scholar]

- Hanuš, L.O.; Maslov, L.N. A Brief but Concise History of the Discovery and Elucidation of the Structure of the Major Cannabinoids. Psychoactives 2025, 4, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khouchlaa, A.; Khouri, S.; Hajib, A.; Zeouk, I.; Amalich, S.; Msairi, S.; El Menyiy, N.; Rais, C.; Lahyaoui, M.; Khalid, A.; et al. Health benefits, pharmacological properties, and metabolism of cannabinol: A comprehensive review. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 213, 118359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, T.B.; Spivey, W.N.; Easterfield, T.H. III.—Cannabinol. Part I. J. Chem. Soc. Trans. 1899, 75, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.; Hunt, M.; Clark, J.H. Structure of cannabidiol, a product isolated from the marihuana extract of Minnesota wild hemp I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1940, 62, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocq, M.A. History of cannabis and the endocannabinoid system. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 22, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pertwee, R.G. Cannabinoid pharmacology: The first 66 years. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2006, 147, S163–S171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finn, D.P.; Haroutounian, S.; Hohmann, A.G.; Krane, E.; Soliman, N.; Rice, A.S. Cannabinoids, the endocannabinoid system, and pain: A review of preclinical studies. Pain 2021, 162, S5–S25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.C.; Mackie, K. Review of the endocannabinoid system. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 2021, 6, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarrete, F.; García-Gutiérrez, M.S.; Jurado-Barba, R.; Rubio, G.; Gasparyan, A.; Austrich-Olivares, A.; Manzanares, J. Endocannabinoid system components as potential biomarkers in psychiatry. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasiulewicz, A.; Znajdek, K.; Grudzień, M.; Pawiński, T.; Sulkowska, J.I. A guide to targeting the endocannabinoid system in drug design. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taha, I.E.; ElSohly, M.A.; Radwan, M.M.; Omari, S.; Repka, M.A.; Ashour, E.A. Development and in vitro evaluation of cannabidiol mucoadhesive buccal film formulations using hot-melt extrusion technology. Med. Cannabis Cannabinoids 2024, 7, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalay, S.; Jarocka-Karpowicz, I.; Skrzydlewska, E. Antioxidative and anti-inflammatory properties of cannabidiol. Antioxidants 2019, 9, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, J.; Fan, M.; An, C.; Ni, F.; Huang, W.; Luo, J. A narrative review of molecular mechanism and therapeutic effect of cannabidiol (CBD). Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2022, 130, 439–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickey, J.P.; Collins, A.E.; Nelson, M.L.; Chen, H.; Kalisch, B.E. Modulation of oxidative stress and Neuroinflammation by Cannabidiol (CBD): Promising targets for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 4379–4402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, D.L.; Devi, L.A. Diversity of molecular targets and signaling pathways for CBD. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2020, 8, e00682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, R.A.; Whalley, B.J. The proposed mechanisms of action of CBD in epilepsy. Epileptic Disord. 2020, 22, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devinsky, O.; Patel, A.D.; Cross, J.H.; Villanueva, V.; Wirrell, E.C.; Privitera, M.; Greenwood, S.M.; Roberts, C.; Checketts, D.; VanLandingham, K.E.; et al. Effect of cannabidiol on drop seizures in the Lennox–Gastaut syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1888–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perucca, E.; Bialer, M. Critical aspects affecting cannabidiol oral bioavailability and metabolic elimination, and related clinical implications. CNS Drugs 2020, 34, 795–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitovs, A.; Logviss, K.; Lauberte, L.; Mohylyuk, V. Oral delivery of cannabidiol: Revealing the formulation and absorption challenges. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2024, 92, 105316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolli, A.R.; Hoeng, J. Cannabidiol bioavailability is nonmonotonic with a long terminal elimination half-life: A pharmacokinetic modeling-based analysis. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2025, 10, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maji, I.; Mahajan, S.; Sriram, A.; Medtiya, P.; Vasave, R.; Khatri, D.K.; Kumar, R.; Singh, S.B.; Madan, J.; Singh, P.K. Solid self emulsifying drug delivery system: Superior mode for oral delivery of hydrophobic cargos. J. Control. Release 2021, 337, 646–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buya, A.B.; Beloqui, A.; Memvanga, P.B.; Préat, V. Self-nano-emulsifying drug-delivery systems: From the development to the current applications and challenges in oral drug delivery. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastav, A.K.; Karpathak, S.; Rai, M.K.; Kumar, D.; Misra, D.P.; Agarwal, V. Lipid based drug delivery systems for oral, transdermal and parenteral delivery: Recent strategies for targeted delivery consistent with different clinical application. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2023, 85, 104526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalepu, S.; Manthina, M.; Padavala, V. Oral lipid-based drug delivery systems–an overview. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2013, 3, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chime, S.A.; Onyishi, I.V. Lipid-based drug delivery systems (LDDS): Recent advances and applications of lipids in drug delivery. Afr. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2013, 7, 3034–3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Beg, S.; Khurana, R.K.; Sandhu, P.S.; Kaur, R.; Katare, O.P. Recent advances in self-emulsifying drug delivery systems (SEDDS). Crit. Rev.™ Ther. Drug Carr. Syst. 2014, 31, 121–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanjani, B.; Garg, A.; Garg, S. A review on self emulsifying drug delivery system. Asian J. Biomater. Res. 2016, 2, 137–141. [Google Scholar]

- Salawi, A. Self-emulsifying drug delivery systems: A novel approach to deliver drugs. Drug Deliv. 2022, 29, 1811–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokania, S.; Joshi, A.K. Self-microemulsifying drug delivery system (SMEDDS)–challenges and road ahead. Drug Deliv. 2015, 22, 675–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhritlahre, R.K.; Padwad, Y.; Saneja, A. Self-emulsifying formulations to augment therapeutic efficacy of nutraceuticals: From concepts to clinic. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 115, 347–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.; Hussain, A.; Hussain, M.S.; Mirza, M.A.; Iqbal, Z. Role of excipients in successful development of self-emulsifying/microemulsifying drug delivery system (SEDDS/SMEDDS). Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2013, 39, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gul, W.; Gul, S.W.; Radwan, M.M.; Wanas, A.S.; Mehmedic, Z.; Khan, I.I.; Sharaf, M.H.; ElSohly, M.A. Determination of 11 cannabinoids in biomass and extracts of different varieties of Cannabis using high-performance liquid chromatography. J. AOAC Int. 2015, 98, 1523–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truong, D.H.; Tran, T.H.; Ramasamy, T.; Choi, J.Y.; Lee, H.H.; Moon, C.; Choi, H.G.; Yong, C.S.; Kim, J.O. Development of solid self-emulsifying formulation for improving the oral bioavailability of erlotinib. Aaps Pharmscitech 2016, 17, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanil, K.; Almotairy, A.; Uttreja, P.; Ashour, E.A. Formulation development and evaluation of cannabidiol hot-melt extruded solid self-emulsifying drug delivery system for oral applications. AAPS PharmSciTech 2024, 25, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kommana, N.; Bharti, K.; Surekha, D.B.; Thokala, S.; Mishra, B. Development, optimization and evaluation of losartan potassium loaded Self Emulsifying Drug Delivery System. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 60, 102026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Prá, M.A.; Vardanega, R.; Loss, C.G. Lipid-based formulations to increase cannabidiol bioavailability: In vitro digestion tests, pre-clinical assessment and clinical trial. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 609, 121159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, L.Y.; Bannigan, P.; Sanaee, F.; Evans, J.C.; Dunne, M.; Regenold, M.; Ahmed, L.; Dubins, D.; Allen, C. Development and pharmacokinetic evaluation of a self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery system for the oral delivery of cannabidiol. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 168, 106058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, I.E.; ElSohly, M.A.; Radwan, M.M.; Elkanayati, R.M.; Wanas, A.; Joshi, P.H.; Ashour, E.A. Enhancement of cannabidiol oral bioavailability through the development of nanostructured lipid carriers: In vitro and in vivo evaluation studies. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2025, 15, 2722–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, P.S.; Serafini, M.R.; Alves, I.A.; Novoa, D.M. Recent progress in self-emulsifying drug delivery systems: A systematic patent review (2011–-2020). Crit. Rev. Ther. Drug Carr. Syst. 2022, 39, 1–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epidiolex. Full Prescribing Information. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/210365lbl.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Porter, C.J.; Pouton, C.W.; Cuine, J.F.; Charman, W.N. Enhancing intestinal drug solubilisation using lipid-based delivery systems. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2008, 60, 673–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, A.; Backensfeld, T.; Denner, K.; Weitschies, W. Effects of non-ionic surfactants on cytochrome P450-mediated metabolism in vitro. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2011, 78, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Mao, X.; Cao, L.; Xue, K.; Si, L.; Qiu, J.; Schimmer, A.D.; Li, G. Nonionic surfactants are strong inhibitors of cytochrome P450 3A biotransformation activity in vitro and in vivo. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2009, 36, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danaei, M.R.; Dehghankhold, M.; Ataei, S.; Hasanzadeh Davarani, F.; Javanmard, R.; Dokhani, A.; Khorasani, S.; Mozafari, Y.M. Impact of particle size and polydispersity index on the clinical applications of lipidic nanocarrier systems. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umadevi, S.; Boopathi, R.S. A paradigm shift in bioavailability enhancement using solid self emulisifying drug delivery system. J. Appl. Pharm. Res. 2025, 13, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, H.; Mihankhah, P.; Khaligh, N.G. Influence of tween nature and type on physicochemical properties and stability of spearmint essential oil (Mentha spicata L.) stabilized with basil seed mucilage nanoemulsion. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 359, 119379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghananim, A.; Özalp, Y.; Mesut, B.; Serakinci, N.; Özsoy, Y.; Güngör, S. A solid ultra fine self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery system (S-snedds) of deferasirox for improved solubility: Optimization, characterization, and in vitro cytotoxicity studies. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohite, P.; Singh, S.; Pawar, A.; Sangale, A.; Prajapati, B.G. Lipid-based oral formulation in capsules to improve the delivery of poorly water-soluble drugs. Front. Drug Deliv. 2023, 3, 1232012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaukonen, A.M.; Boyd, B.J.; Porter, C.J.; Charman, W.N. Drug solubilization behavior during in vitro digestion of simple triglyceride lipid solution formulations. Pharm. Res. 2004, 21, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdalla, A.; Klein, S.; Mäder, K. A new self-emulsifying drug delivery system (SEDDS) for poorly soluble drugs: Characterization, dissolution, in vitro digestion and incorporation into solid pellets. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2008, 35, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sek, L.; Porter, C.J.; Kaukonen, A.M.; Charman, W.N. Evaluation of the in--vitro digestion profiles of long and medium chain glycerides and the phase behaviour of their lipolytic products. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2002, 54, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Formulation | Capryol® 90 (% w/w) | Tween® 20 (% w/w) | Transcutol® HP (% w/w) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CTT1 | 20 | 65 | 15 |

| CTT2 | 80 | 10 | 10 |

| CTT3 | 10 | 80 | 10 |

| CTT4 | 15 | 80 | 5 |

| CTT5 | 50 | 40 | 10 |

| CTT6 | 25 | 70 | 5 |

| CTT7 | 30 | 60 | 10 |

| CTT8 | 15 | 70 | 15 |

| CTT9 | 40 | 45 | 15 |

| CTT10 | 60 | 25 | 15 |

| CTT11 | 10 | 10 | 80 |

| CTT12 | 20 | 40 | 40 |

| CTT13 | 15 | 55 | 30 |

| CTT14 | 25 | 15 | 60 |

| CTT15 | 40 | 15 | 45 |

| CTT16 | 50 | 20 | 30 |

| Formulation | E T (sec.) | P S * (nm) | PDI |

|---|---|---|---|

| CTT1 | 57 | 13.85 ± 1.11 | 0.24 ± 0.02 |

| CTT2 | _ | _ | _ |

| CTT3 | 20 | 17.76 ± 14.12 | 0.20 ± 0.08 |

| CTT4 | 15 | 11.16 ± 2.16 | 0.18 ± 0.47 |

| CTT5 | 10 | 266 ± 17.36 | 0.37 ± 0.02 |

| CTT6 | 13 | 82.66 ± 2.36 | 0.54 ± 0.04 |

| CTT7 | 10 | 89.57 ± 53.77 | 0.85 ± 0.24 |

| CTT8 | 11 | 10.49 ± 0.57 | 0.18 ± 0.04 |

| CTT9 | 5 | 225.00 ± 50.11 | 0.46 ± 0.16 |

| CTT10 | - | - | - |

| CTT11 | 5 | 405.50 ± 119 | 0.39 ± 0.09 |

| CTT12 | 6 | 63.59 ± 1.17 | 0.20 ± 0.02 |

| CTT13 | 25 | 11.50 ± 0.87 | 0.17 ± 0.06 |

| CTT14 | 5 | 146.50 ± 49.82 | 0.38 ± 0.09 |

| CTT15 | _ | _ | _ |

| CTT16 | _ | _ | _ |

| Group | Cmax (ng/mL) | Tmax (h) | AUC0–4h (ng⋅h/mL) | AUC0–24h (ng⋅h/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBD-IV | 1513.63 ± 480.42 | 0.083 | 649.80 ± 65.45 | 912.79 ± 159.86 |

| CTT4 | 129.03 ± 53.15 | 4 | 249.33 ± 29.05 | 1363.16 ± 245.13 |

| CTT8 | 49.22 ± 44.55 | 4 | 147.01 ± 94.46 | 549.12 ± 199.94 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mostafa, N.; Taha, I.E.; Abourobe, N.M.; Ashour, E.A. Development and Characterization of Cannabidiol Self-Emulsifying Drug Delivery System: In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation. Biomolecules 2026, 16, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010021

Mostafa N, Taha IE, Abourobe NM, Ashour EA. Development and Characterization of Cannabidiol Self-Emulsifying Drug Delivery System: In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation. Biomolecules. 2026; 16(1):21. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010021

Chicago/Turabian StyleMostafa, Nourhan, Iman E. Taha, Noha M. Abourobe, and Eman A. Ashour. 2026. "Development and Characterization of Cannabidiol Self-Emulsifying Drug Delivery System: In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation" Biomolecules 16, no. 1: 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010021

APA StyleMostafa, N., Taha, I. E., Abourobe, N. M., & Ashour, E. A. (2026). Development and Characterization of Cannabidiol Self-Emulsifying Drug Delivery System: In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation. Biomolecules, 16(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010021