Absence of Neuromuscular Dysfunction in Mice with Gut Epithelium-Restricted Expression of ALS Mutation hSOD1G93A

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Transgenic Mouse Models and Genotyping

2.2. Immunohistochemistry

2.3. Immunoblotting Assay

2.4. Gut Permeability Assessment

2.5. In Vivo Muscle Contractility Assessment

2.6. Mouse Daily Activity Monitoring

2.7. Grip Strength Assessment

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Generation of Transgenic Mice with Gut-Specific Overexpression of ALS Mutation hSOD1G93A (Gut-hG93A)

3.2. Confirmation of Gut-Specific hSOD1G93A Expression

3.3. Assessment of Gut Barrier Function in Gut-hG93A Mice

3.4. Analysis of Epithelial Tight Junctions and Adherens Junctions

3.5. Neuromuscular Activity Assessment in Gut-hG93A Mice

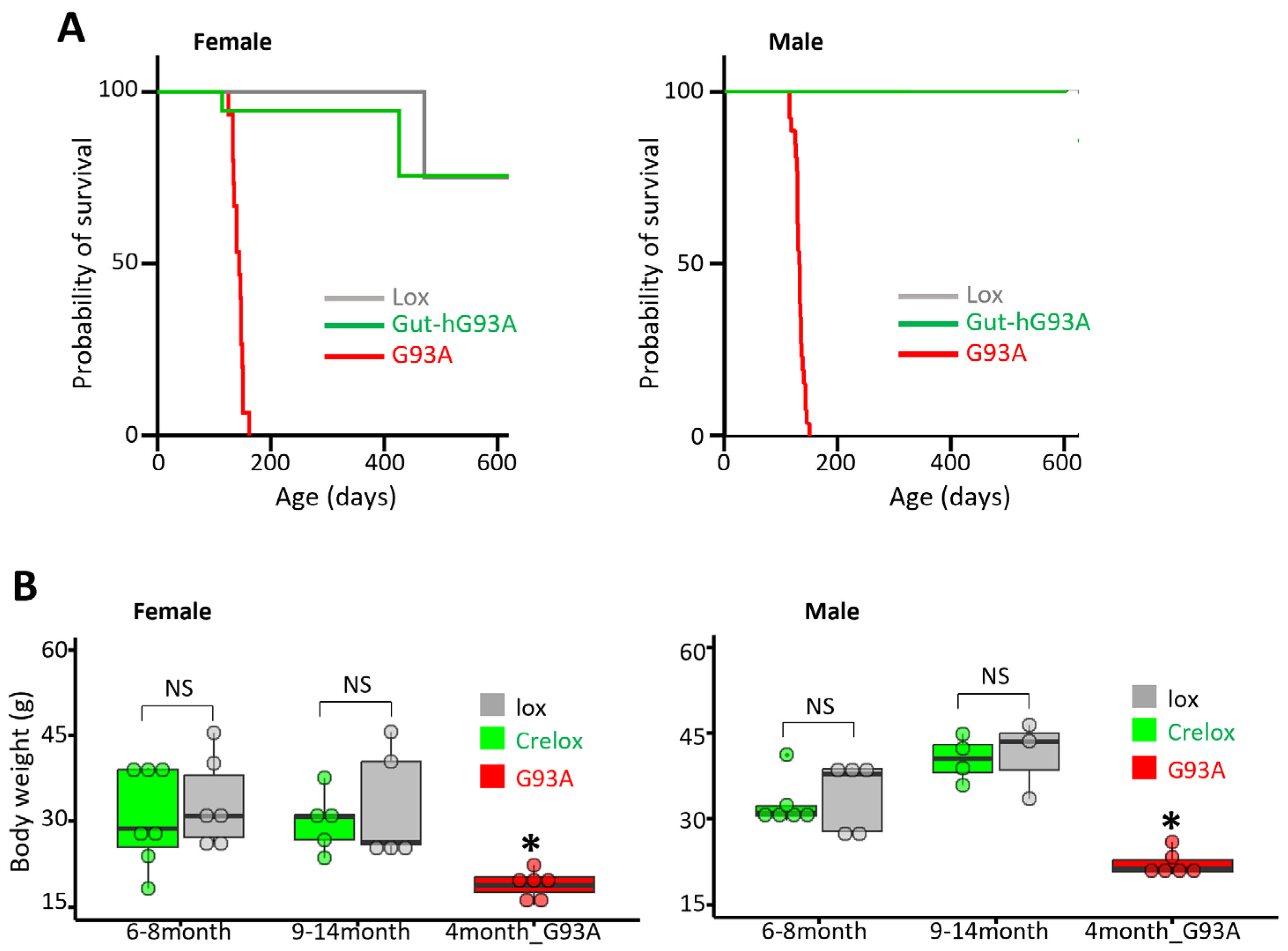

3.6. Impact on Survival and Body Weight of Gut-hG93A

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALS | Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis |

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| SOD1 | Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase type 1 |

| RFID | Radio-frequency-identification |

| FD4 | Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-4KD |

| R70 | Rhodamine B isothiocyanate |

| TA | Tibialis Anterior |

References

- Hardiman, O.; Al-Chalabi, A.; Chio, A.; Corr, E.M.; Logroscino, G.; Robberecht, W.; Shaw, P.J.; Simmons, Z.; van den Berg, L.H. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2017, 3, 17071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vucic, S.; Rothstein, J.D.; Kiernan, M.C. Advances in treating amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Insights from pathophysiological studies. Trends Neurosci. 2014, 37, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mead, R.J.; Shan, N.; Reiser, H.J.; Marshall, F.; Shaw, P.J. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A neurodegenerative disorder poised for successful therapeutic translation. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2023, 22, 185–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Roon-Mom, W.; Ferguson, C.; Aartsma-Rus, A. From Failure to Meet the Clinical Endpoint to US Food and Drug Administration Approval: 15th Antisense Oligonucleotide Therapy Approved Qalsody (Tofersen) for Treatment of SOD1 Mutated Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2023, 33, 234–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilieva, H.; Vullaganti, M.; Kwan, J. Advances in molecular pathology, diagnosis, and treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. BMJ 2023, 383, e075037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faller, K.M.; Chaytow, H.; Gillingwater, T.H. Targeting common disease pathomechanisms to treat amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2025, 21, 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yi, J.; Li, X.; Xiao, Y.; Dhakal, K.; Zhou, J. ALS-associated mutation SOD1(G93A) leads to abnormal mitochondrial dynamics in osteocytes. Bone 2018, 106, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Yi, J.; Zhang, Y.G.; Zhou, J.; Sun, J. Leaky intestine and impaired microbiome in an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mouse model. Physiol. Rep. 2015, 3, e12356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Yi, J.; Xiao, Y.; Lai, Y.; Song, P.; Zheng, W.; Jiao, H.; Fan, J.; Wu, C.; Chen, D.; et al. Impaired bone homeostasis in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mice with muscle atrophy. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 8081–8094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shefner, J.M.; Musaro, A.; Ngo, S.T.; Lunetta, C.; Steyn, F.J.; Robitaille, R.; De Carvalho, M.; Rutkove, S.; Ludolph, A.C.; Dupuis, L. Skeletal muscle in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain 2023, 146, 4425–4436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loeffler, J.P.; Picchiarelli, G.; Dupuis, L.; Gonzalez De Aguilar, J.L. The Role of Skeletal Muscle in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Brain Pathol. 2016, 26, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toepfer; Folwaczny, C.; Klauser, A.; Riepl, R.L.; Muller-Felber, W.; Pongratz M, D. Gastrointestinal dysfunction in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Other Mot. Neuron Disord. 2000, 1, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowin, J.; Xia, Y.; Jung, B.; Sun, J. Gut inflammation and dysbiosis in human motor neuron disease. Physiol. Rep. 2017, 5, e13443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Wang, X.; Yang, S.; Meng, F.; Wang, X.; Wei, H.; Chen, T. Evaluation of the microbial diversity in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis using high-throughput sequencing. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, T.; Wang, P.; Zhou, X.; Liu, T.; Liu, Q.; Li, R.; Yang, H.; Dong, H.; Liu, Y. An overlap-weighted analysis on the association of constipation symptoms with disease progression and survival in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A nested case-control study. Ther. Adv. Neurol. Disord. 2025, 18, 17562864241309811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Zhuang, Z.; Zhang, G.; Huang, T.; Fan, D. Assessment of bidirectional relationships between 98 genera of the human gut microbiota and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A 2-sample Mendelian randomization study. BMC Neurol. 2022, 22, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-Cantu, C.; Zaldivar-Ruenes, A.; Martinez-Vazquez, M.; Martinez, H.R. Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms, severity of dysphagia, and their correlation with severity of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in a Mexican cohort. Neurodegener. Dis. 2021, 21, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samara, V.C.; Jerant, P.; Gibson, S.; Bromberg, M. Bowel, bladder, and sudomotor symptoms in ALS patients. J. Neurol. Sci. 2021, 427, 117543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholson, K.; Bjornevik, K.; Abu-Ali, G.; Chan, J.; Cortese, M.; Dedi, B.; Jeon, M.; Xavier, R.; Huttenhower, C.; Ascherio, A. The human gut microbiota in people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2021, 22, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, D.; Hiergeist, A.; Adis, C.; Mayer, B.; Gessner, A.; Ludolph, A.C.; Weishaupt, J.H. The fecal microbiome of ALS patients. Neurobiol. Aging 2018, 61, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurney, M.E.; Pu, H.; Chiu, A.Y.; Dal Canto, M.C.; Polchow, C.Y.; Alexander, D.D.; Caliendo, J.; Hentati, A.; Kwon, Y.W.; Deng, H.X.; et al. Motor neuron degeneration in mice that express a human Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase mutation. Science 1994, 264, 1772–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludolph, A.C.; Bendotti, C.; Blaugrund, E.; Hengerer, B.; Loffler, J.P.; Martin, J.; Meininger, V.; Meyer, T.; Moussaoui, S.; Robberecht, W.; et al. Guidelines for the preclinical in vivo evaluation of pharmacological active drugs for ALS/MND: Report on the 142nd ENMC international workshop. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. 2007, 8, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa-Romero, C.; Guo, K.; Murdock, B.J.; Paez-Colasante, X.; Bassis, C.M.; Mikhail, K.A.; Raue, K.D.; Evans, M.C.; Taubman, G.F.; McDermott, A.J. Temporal evolution of the microbiome, immune system and epigenome with disease progression in ALS mice. Dis. Models Mech. 2020, 13, dmm041947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burberry, A.; Wells, M.F.; Limone, F.; Couto, A.; Smith, K.S.; Keaney, J.; Gillet, G.; Van Gastel, N.; Wang, J.-Y.; Pietilainen, O. C9orf72 suppresses systemic and neural inflammation induced by gut bacteria. Nature 2020, 582, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blacher, E.; Bashiardes, S.; Shapiro, H.; Rothschild, D.; Mor, U.; Dori-Bachash, M.; Kleimeyer, C.; Moresi, C.; Harnik, Y.; Zur, M. Potential roles of gut microbiome and metabolites in modulating ALS in mice. Nature 2019, 572, 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, L.M.; Calcagno, N.; Gauthier, C.; Madore, C.; Butovsky, O.; Weiner, H.L. The microbiota restrains neurodegenerative microglia in a model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Microbiome 2022, 10, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X. Potential role of gut microbiota and tissue barriers in Parkinson’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Int. J. Neurosci. 2016, 126, 771–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, M.; Gershon, M.D. The bowel and beyond: The enteric nervous system in neurological disorders. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 13, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheperjans, F. Can microbiota research change our understanding of neurodegenerative diseases? Neurodegener. Dis. Manag. 2016, 6, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Zhang, Y. Microbiome and micronutrient in ALS: From novel mechanisms to new treatments. Neurotherapeutics 2024, 21, e00441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.; Battistini, C.; Sun, J. A gut feeling in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Microbiome of mice and men. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 839526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Cai, X.; Lao, L.; Wang, Y.; Su, H.; Sun, H. Brain-gut-microbiota axis in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A historical overview and future directions. Aging Dis. 2024, 15, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noor Eddin, A.; Alfuwais, M.; Noor Eddin, R.; Alkattan, K.; Yaqinuddin, A. Gut-Modulating Agents and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Current Evidence and Future Perspectives. Nutrients 2024, 16, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, J.; Li, A.; Li, X.; Park, K.; Zhou, X.; Yi, F.; Xiao, Y.; Yoon, D.; Tan, T.; Ostrow, L.W.; et al. MG53 Preserves Neuromuscular Junction Integrity and Alleviates ALS Disease Progression. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Dong, L.; Li, A.; Yi, J.; Brotto, M.; Zhou, J. Butyrate Ameliorates Mitochondrial Respiratory Capacity of The Motor-Neuron-like Cell Line NSC34-G93A, a Cellular Model for ALS. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oami, T.; Coopersmith, C.M. Measurement of intestinal permeability during sepsis. In Sepsis Methods and Protocols; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 169–175. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, G.; Yi, J.; Ma, C.; Xiao, Y.; Yi, F.; Yu, T.; Zhou, J. Defective mitochondrial dynamics is an early event in skeletal muscle of an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mouse model. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e82112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutlin, M.; Rastelli, D.; Kuo, W.; Estep, J.; Louis, A.; Riccomagno, M.; Turner, J.; Rao, M. The Villin1 gene promoter drives Cre recombinase expression in extraintestinal tissues. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 10, 864–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odenwald, M.A.; Turner, J.R. The intestinal epithelial barrier: A therapeutic target? Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 14, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldink, J.; Bär, P.; Joosten, E.; Otten, M.; Wokke, J.; Van Den Berg, L. Sexual differences in onset of disease and response to exercise in a transgenic model of ALS. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2003, 13, 737–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, M.; Tork, C.; Shelley, B.; Mchugh, J.; Wallace, K.; Klein, S.M.; Lindstrom, M.J.; Svendsen, C.N. Sexual dimorphism in disease onset and progression of a rat model of ALS. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. 2007, 8, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo-Arozena, A.; Kalmar, B.; Essa, S.; Ricketts, T.; Joyce, P.; Kent, R.; Rowe, C.; Parker, A.; Gray, A.; Hafezparast, M. A comprehensive assessment of the SOD1G93A low-copy transgenic mouse, which models human amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Dis. Models Mech. 2011, 4, 686–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, N. Transgenic mouse model for familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with superoxide dismutase-1 mutation. Neuropathology 2001, 21, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar-Kasza, A.; Hinteregger, B.; Neddens, J.; Rabl, R.; Flunkert, S.; Hutter-Paier, B. Evaluation of neuropathological features in the SOD1-G93A low copy number transgenic mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2021, 14, 681868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Sengupta, P. Men and mice: Relating their ages. Life Sci. 2016, 152, 244–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masrori, P.; Van Damme, P. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A clinical review. Eur. J. Neurol. 2020, 27, 1918–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logroscino, G.; Traynor, B.J.; Hardiman, O.; Chiò, A.; Mitchell, D.; Swingler, R.J.; Millul, A.; Benn, E.; Beghi, E. Incidence of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in Europe. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2010, 81, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, D.R.; Siddique, T.; Patterson, D.; Figlewicz, D.A.; Sapp, P.; Hentati, A.; Donaldson, D.; Goto, J.; O’Regan, J.P.; Deng, H.X.; et al. Mutations in Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase gene are associated with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature 1993, 362, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, M.; Liu, Y.U.; Yao, X.; Qin, D.; Su, H. Variability in SOD1-associated amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Geographic patterns, clinical heterogeneity, molecular alterations, and therapeutic implications. Transl. Neurodegener. 2024, 13, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, G.S.; Antonyuk, S.V.; Hasnain, S.S. The biophysics of superoxide dismutase-1 and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2019, 52, e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunton-Stasyshyn, R.K.; Saccon, R.A.; Fratta, P.; Fisher, E.M. SOD1 function and its implications for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis pathology: New and renascent themes. Neuroscientist 2015, 21, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furukawa, Y.; Fu, R.; Deng, H.-X.; Siddique, T.; O’Halloran, T.V. Disulfide cross-linked protein represents a significant fraction of ALS-associated Cu, Zn-superoxide dismutase aggregates in spinal cords of model mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 7148–7153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Deng, H.-X.; Grisotti, G.; Zhai, H.; Siddique, T.; Roos, R.P. Wild-type SOD1 overexpression accelerates disease onset of a G85R SOD1 mouse. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009, 18, 1642–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sender, R.; Milo, R. The distribution of cellular turnover in the human body. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, N. Adult intestinal stem cells: Critical drivers of epithelial homeostasis and regeneration. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisp, M.J.; Mawuenyega, K.G.; Patterson, B.W.; Reddy, N.C.; Chott, R.; Self, W.K.; Weihl, C.C.; Jockel-Balsarotti, J.; Varadhachary, A.S.; Bucelli, R.C. In vivo kinetic approach reveals slow SOD1 turnover in the CNS. J. Clin. Investig. 2015, 125, 2772–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrawell, N.E.; Yerbury, J.J. Mutant Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase (A4V) turnover is altered in cells containing inclusions. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2021, 14, 771911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludolph, A.C.; Bendotti, C.; Blaugrund, E.; Chio, A.; Greensmith, L.; Loeffler, J.P.; Mead, R.; Niessen, H.G.; Petri, S.; Pradat, P.F.; et al. Guidelines for preclinical animal research in ALS/MND: A consensus meeting. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. 2010, 11, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dong, L.; Li, X.; Li, A.; Yi, J.; Vockery, Y.; Chang, Y.; Pan, Z.; Brotto, M.; Zhou, J. Absence of Neuromuscular Dysfunction in Mice with Gut Epithelium-Restricted Expression of ALS Mutation hSOD1G93A. Biomolecules 2026, 16, 253. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16020253

Dong L, Li X, Li A, Yi J, Vockery Y, Chang Y, Pan Z, Brotto M, Zhou J. Absence of Neuromuscular Dysfunction in Mice with Gut Epithelium-Restricted Expression of ALS Mutation hSOD1G93A. Biomolecules. 2026; 16(2):253. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16020253

Chicago/Turabian StyleDong, Li, Xuejun Li, Ang Li, Jianxun Yi, Yanan Vockery, Yan Chang, Zui Pan, Marco Brotto, and Jingsong Zhou. 2026. "Absence of Neuromuscular Dysfunction in Mice with Gut Epithelium-Restricted Expression of ALS Mutation hSOD1G93A" Biomolecules 16, no. 2: 253. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16020253

APA StyleDong, L., Li, X., Li, A., Yi, J., Vockery, Y., Chang, Y., Pan, Z., Brotto, M., & Zhou, J. (2026). Absence of Neuromuscular Dysfunction in Mice with Gut Epithelium-Restricted Expression of ALS Mutation hSOD1G93A. Biomolecules, 16(2), 253. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16020253