The Cap-Independent Translation of Survivin 5′UTR and HIV-1 IRES Sequences Is Inhibited by Oxidative Stress Produced by H. pylori Gamma-Glutamyl Transpeptidase Activity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines and Culture Conditions

2.2. Reporter Plasmid Construction

2.3. Luciferase Reporter Assay

2.4. Western Blot Analysis

2.5. Reverse Transcription and Polymerase Chain Reaction

2.6. In Vitro Transcription

2.7. In Vitro Translation

2.8. siRNA Transfection

2.9. Infection of AGS Cells

2.10. Statistical Analysis of Data

3. Results

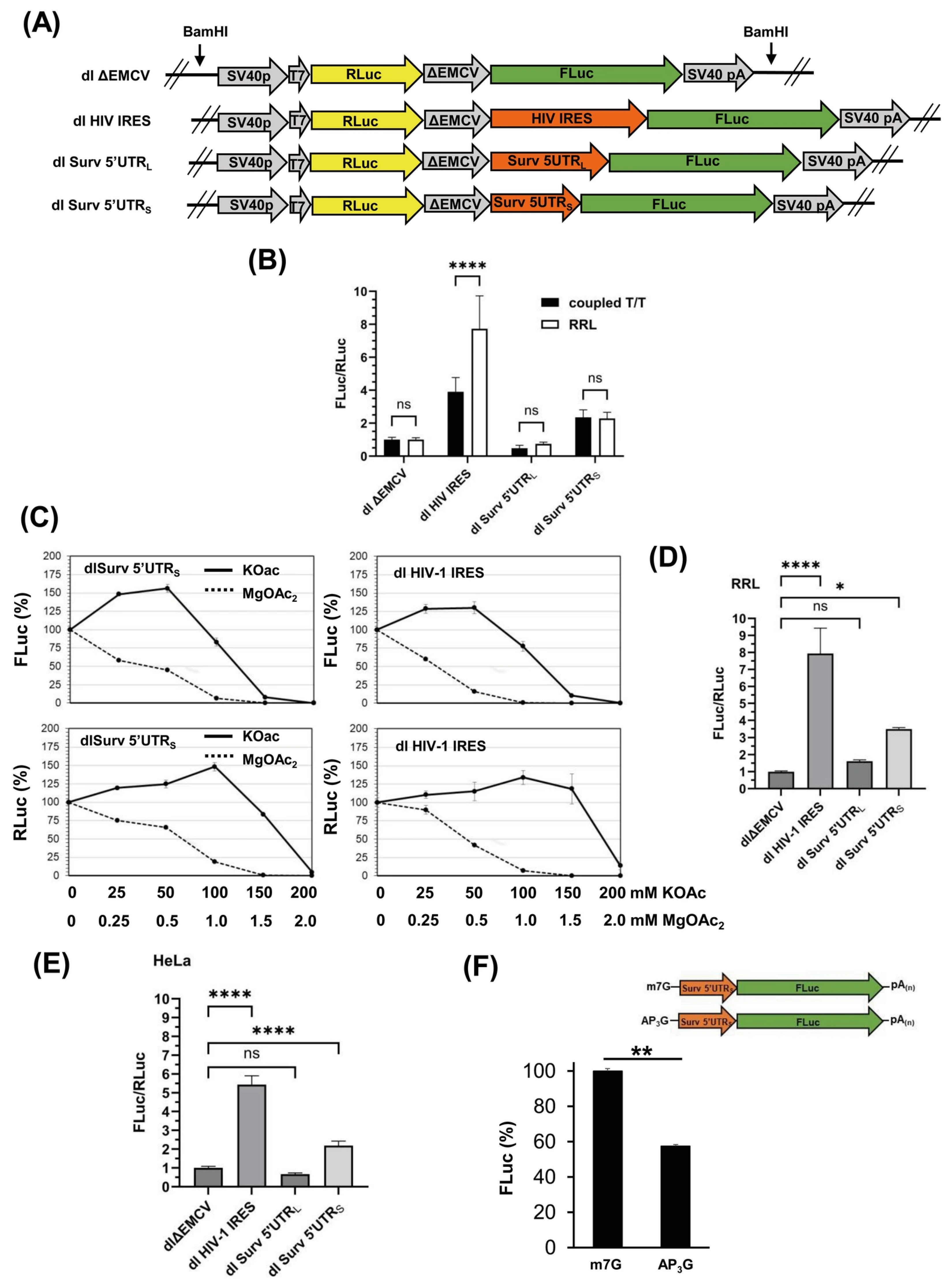

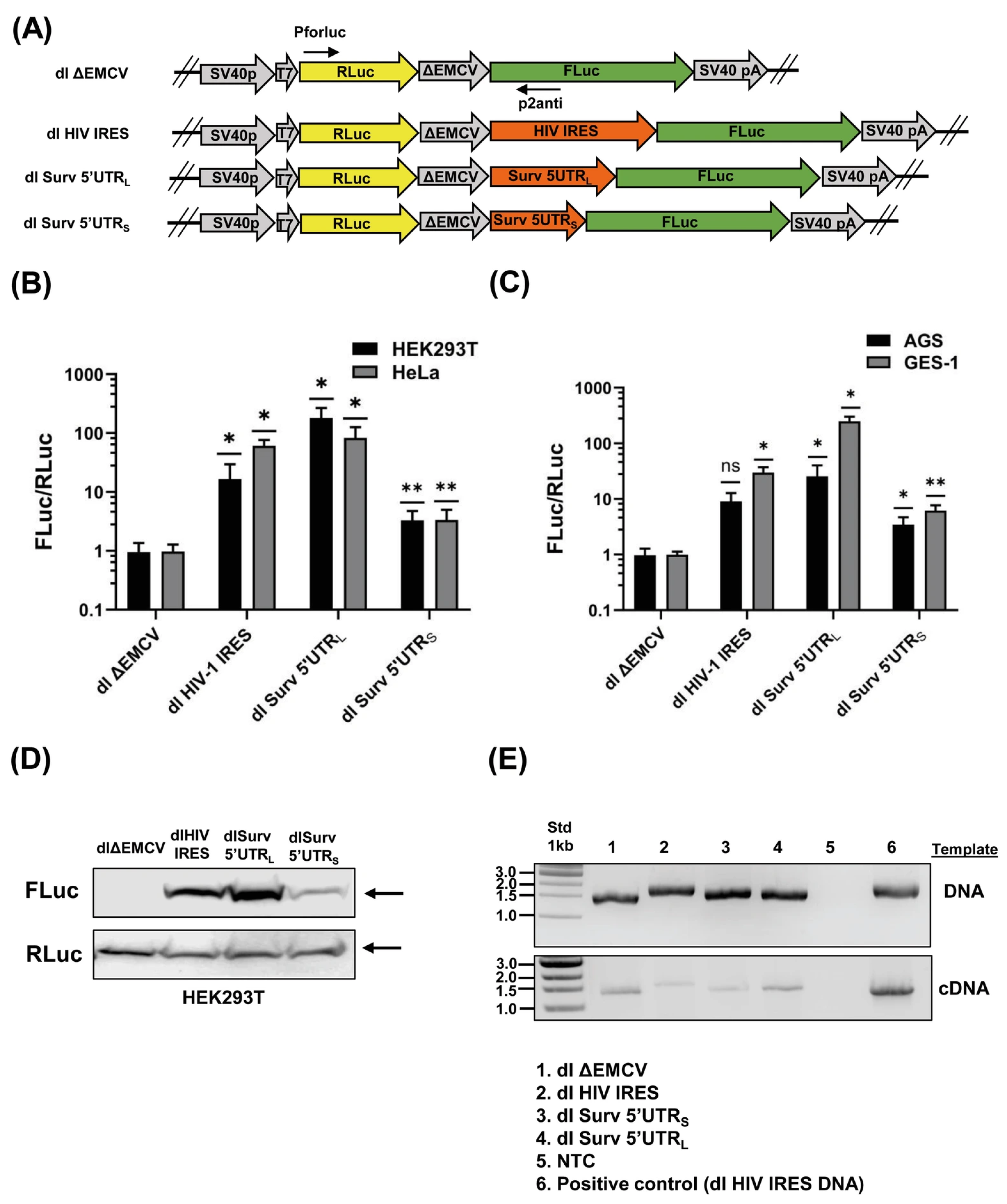

3.1. The Survivin 5′UTRs Drive Translation in a Bicistronic Assay

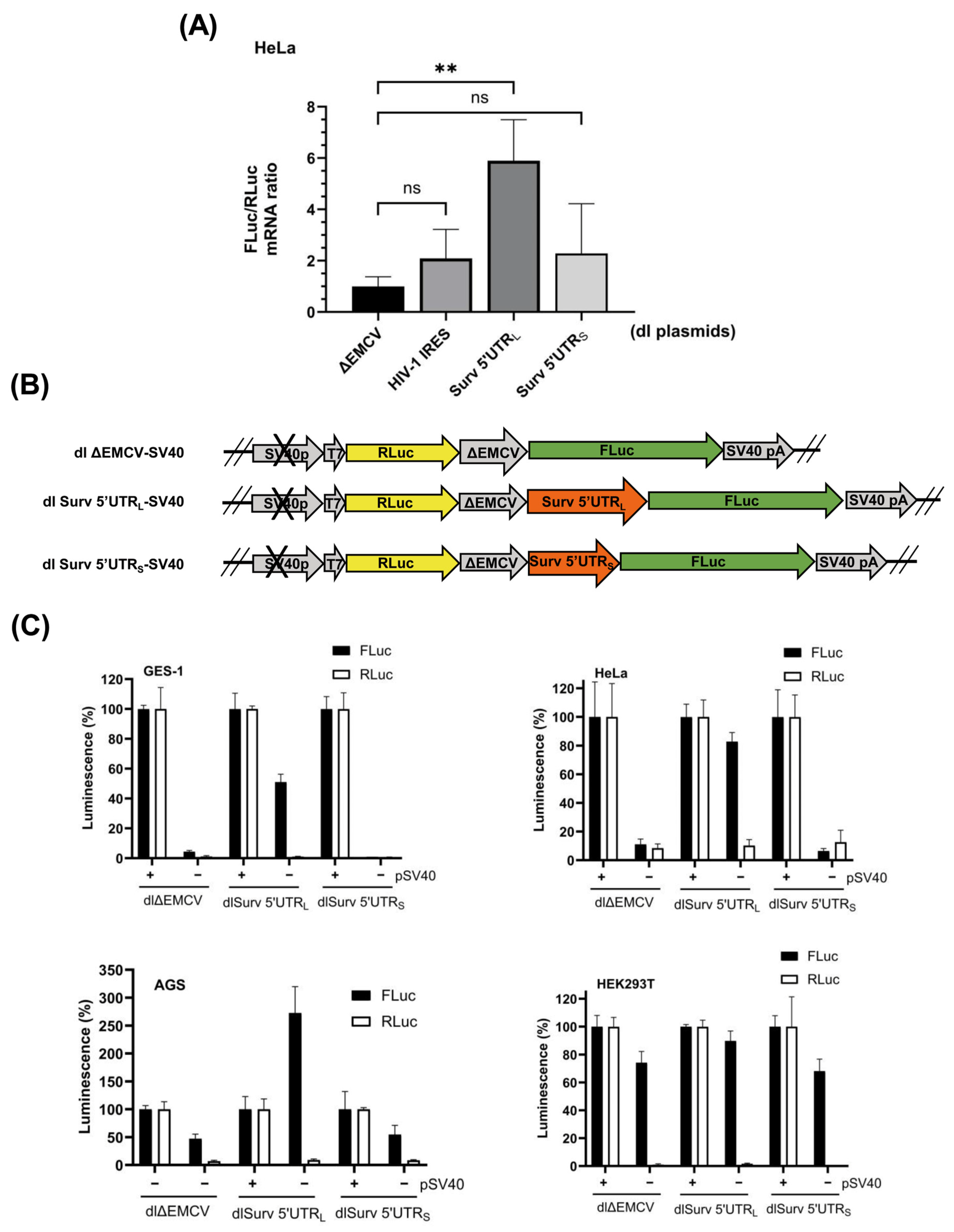

3.2. The Survivin 5′UTRL Contains a Region with Cryptic Promoter Activity

3.3. Survivin 5′UTRS Exhibits Cap-Independent Activity

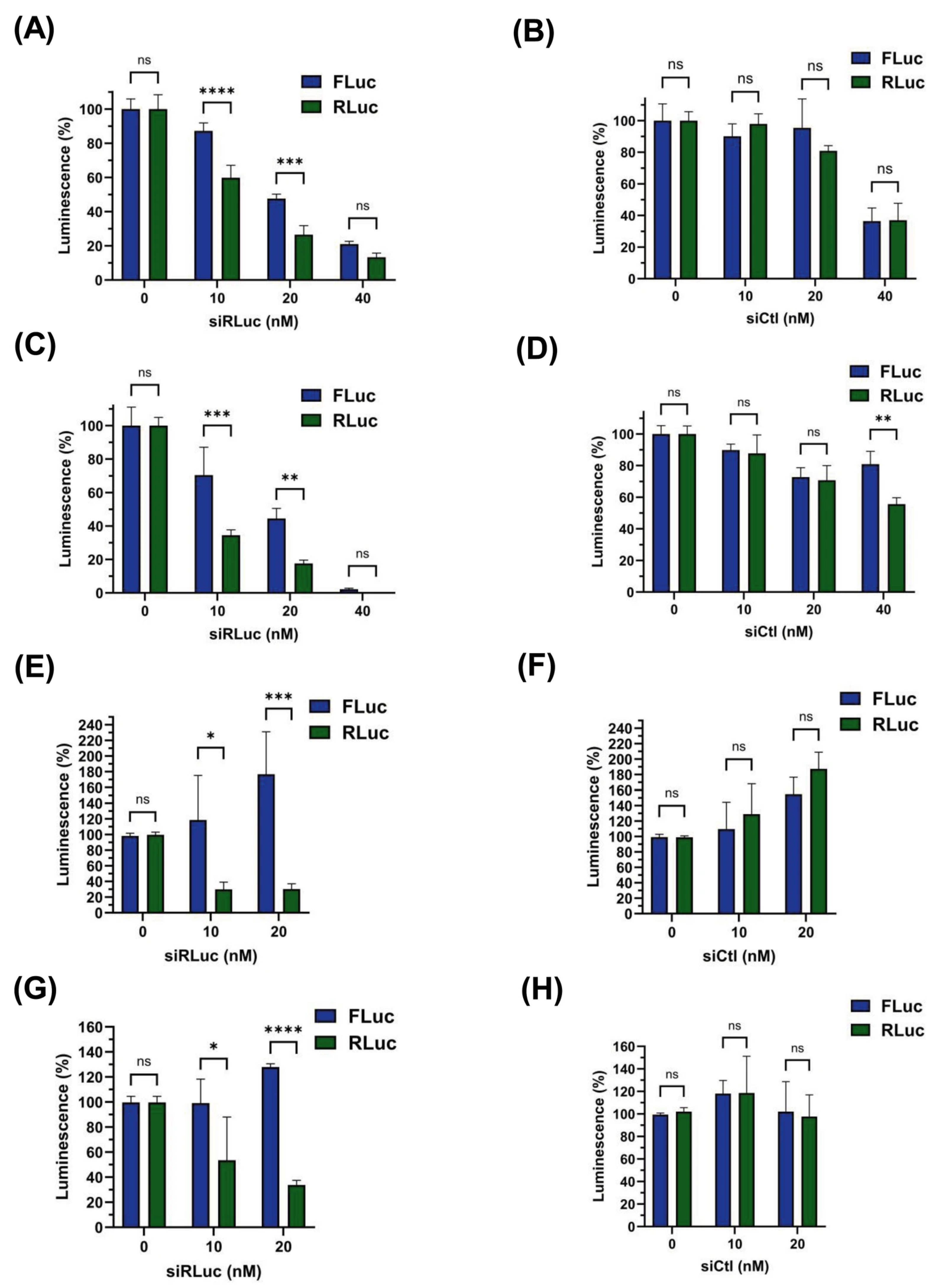

3.4. siRNA-Mediated Destabilization of Bicistronic mRNAs

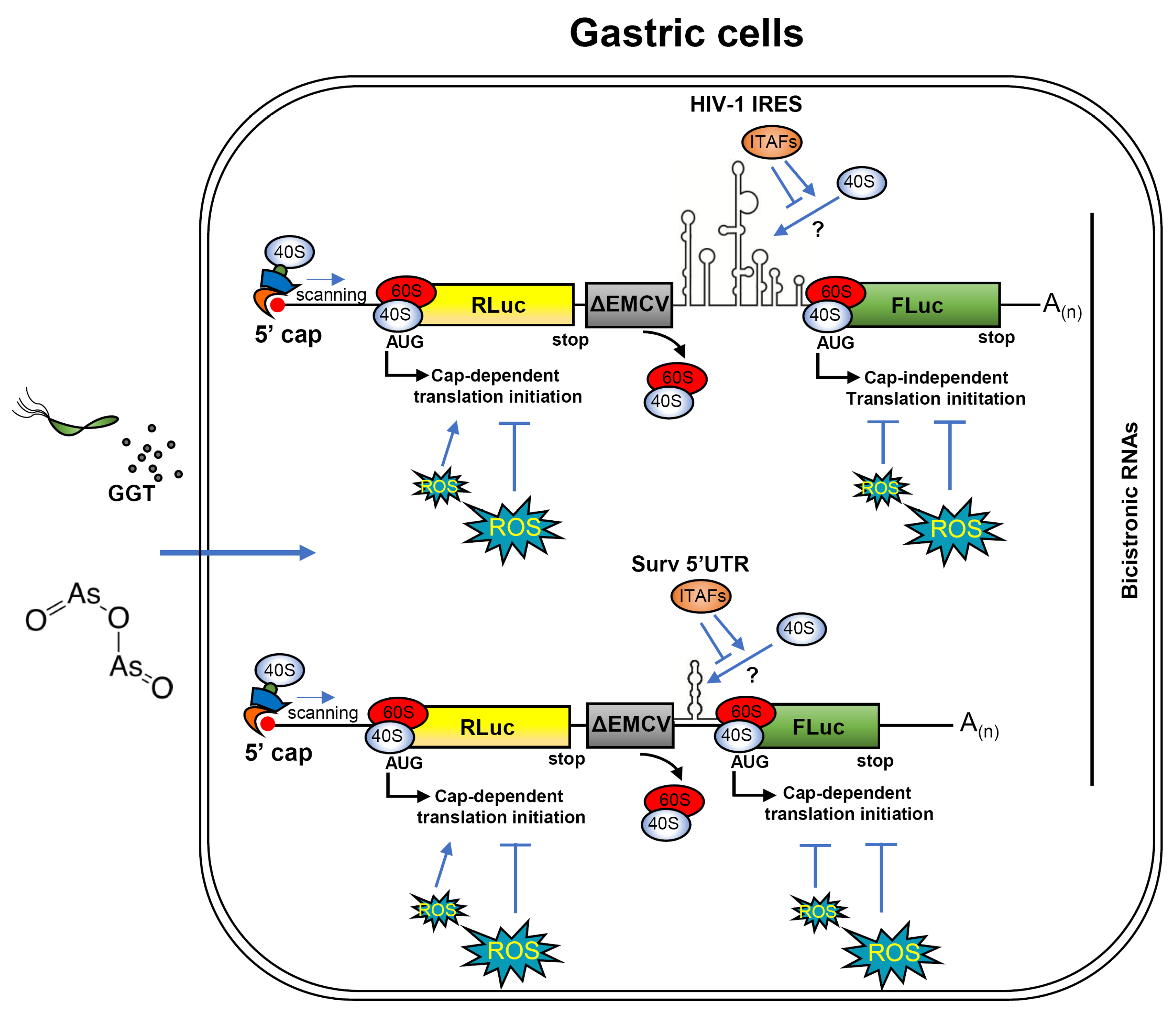

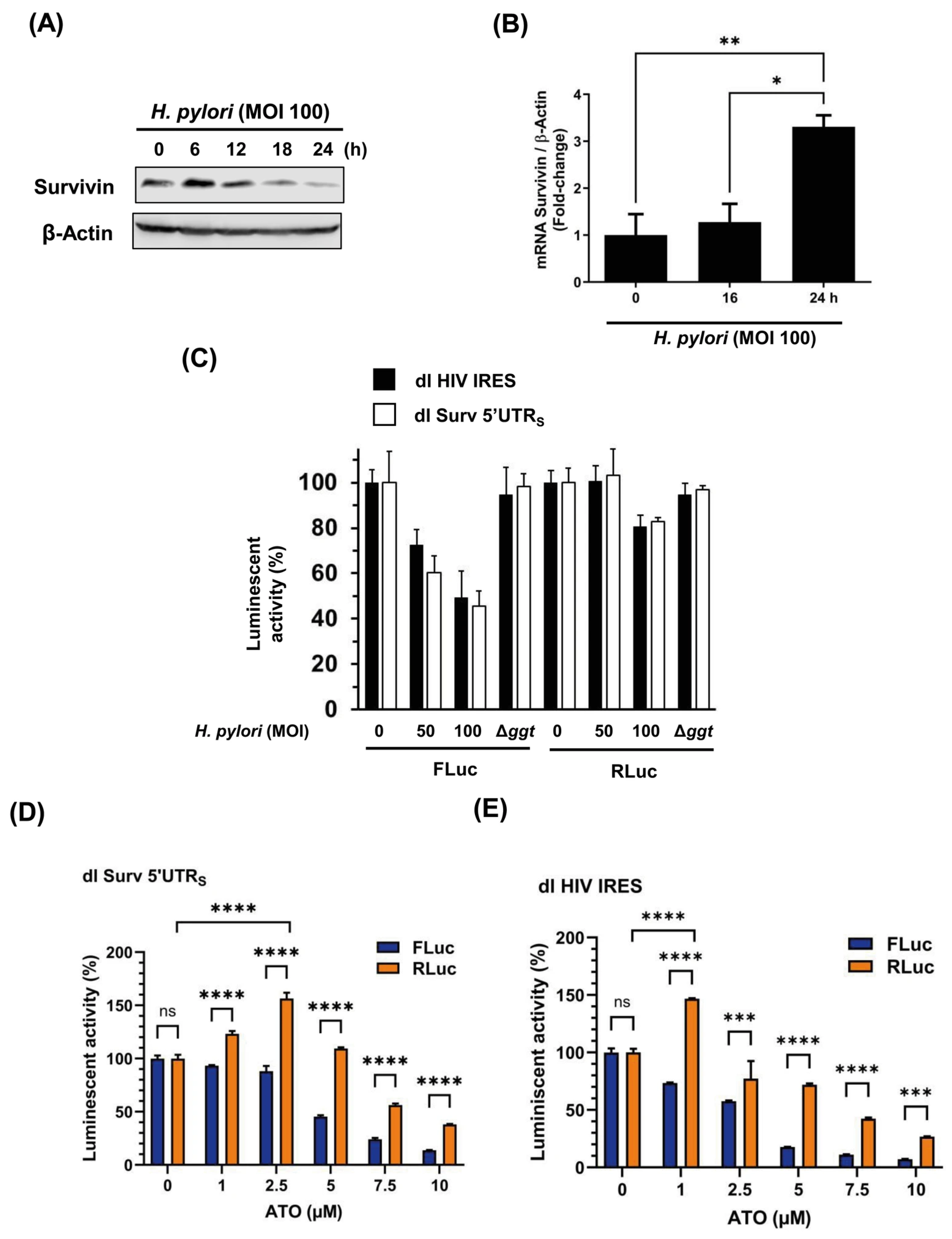

3.5. The Cap-Independent Translation Is Sensitive to Oxidative Stress Produced by H. pylori Gamma-Glutamyl Transpeptidase Activity and a Prooxidant Agent

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 5′UTR | 5′ untranslated region |

| poly(A)+ | RNA polyadenylated |

| Cap+ | Capped RNA |

| H. pylori | Helicobacter pylori |

| HCV | Hepatitis C virus |

| IRES | Internal ribosome entry site |

| GGT | gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase |

| HIV-1 | Human Immunodeficiency Virus 1 |

| ATO | Arsenic trioxide |

| ROS | Radical oxygen species |

| EMVC | Encephalomyocarditis virus |

| RLuc/FLuc | Renilla/Firefly luciferases |

| ITAF | IRES trans-acting factor |

| Surv 5′UTRS | Survivin 5′UTR short variant |

| Surv 5′UTRL | Survivin 5′UTR long variant |

| RRL | Rabbit reticulocyte lysate |

| MOI | Multiplicity of infection |

References

- Cheung, C.H.; Huang, C.C.; Tsai, F.Y.; Lee, J.Y.; Cheng, S.M.; Chang, Y.C.; Huang, Y.C.; Chen, S.H.; Chang, J.Y. Survivin—Biology and potential as a therapeutic target in oncology. OncoTargets Ther. 2013, 6, 1453–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, M.; Bravo, D.; Canales, J.; Sanhueza, C.; Diaz, N.; Almarza, O.; Toledo, H.; Quest, A.F. Helicobacter pylori-induced loss of survivin and gastric cell viability is attributable to secreted bacterial gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase activity. J. Infect. Dis. 2013, 208, 1131–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valenzuela, M.; Perez-Perez, G.; Corvalan, A.H.; Carrasco, G.; Urra, H.; Bravo, D.; Toledo, H.; Quest, A.F. Helicobacter pylori-induced loss of the inhibitor-of-apoptosis protein survivin is linked to gastritis and death of human gastric cells. J. Infect. Dis. 2010, 202, 1021–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafatmanesh, A.; Behjati, M.; Mobasseri, N.; Sarvizadeh, M.; Mazoochi, T.; Karimian, M. The survivin molecule as a double-edged sword in cellular physiologic and pathologic conditions and its role as a potential biomarker and therapeutic target in cancer. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 235, 725–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Aljahdali, I.; Ling, X. Cancer therapeutics using survivin BIRC5 as a target: What can we do after over two decades of study? J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. CR 2019, 38, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lladser, A.; Sanhueza, C.; Kiessling, R.; Quest, A.F. Is survivin the potential Achilles’ heel of cancer? Adv. Cancer Res. 2011, 111, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budhidarmo, R.; Day, C.L. IAPs: Modular regulators of cell signalling. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2015, 39, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamm, I.; Wang, Y.; Sausville, E.; Scudiero, D.A.; Vigna, N.; Oltersdorf, T.; Reed, J.C. IAP-family protein survivin inhibits caspase activity and apoptosis induced by Fas (CD95), Bax, caspases, and anticancer drugs. Cancer Res. 1998, 58, 5315–5320. [Google Scholar]

- Dohi, T.; Okada, K.; Xia, F.; Wilford, C.E.; Samuel, T.; Welsh, K.; Marusawa, H.; Zou, H.; Armstrong, R.; Matsuzawa, S.; et al. An IAP-IAP complex inhibits apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 34087–34090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Nettesheim, D.; Liu, Z.; Olejniczak, E.T. Solution structure of human survivin and its binding interface with Smac/Diablo. Biochemistry 2005, 44, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, M.A.; Lan, W.; Powers, S.E.; McCleland, M.L.; Kuang, J.; Stukenberg, P.T. Aurora B kinase exists in a complex with survivin and INCENP and its kinase activity is stimulated by survivin binding and phosphorylation. Mol. Biol. Cell 2002, 13, 3064–3077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanhueza, C.; Wehinger, S.; Castillo Bennett, J.; Valenzuela, M.; Owen, G.I.; Quest, A.F. The twisted survivin connection to angiogenesis. Mol. Cancer 2015, 14, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, X.; Lu, M.; Zhou, Y.; Li, G.; Liu, Z. LncRNA FENDRR represses proliferation, migration and invasion through suppression of survivin in cholangiocarcinoma cells. Cell Cycle 2019, 18, 889–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boidot, R.; Vegran, F.; Lizard-Nacol, S. Transcriptional regulation of the survivin gene. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2014, 41, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Necochea-Campion, R.; Chen, C.S.; Mirshahidi, S.; Howard, F.D.; Wall, N.R. Clinico-pathologic relevance of Survivin splice variant expression in cancer. Cancer Lett. 2013, 339, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Gambosova, K.; Cooper, Z.A.; Holloway, M.P.; Kassai, A.; Izquierdo, D.; Cleveland, K.; Boney, C.M.; Altura, R.A. EGF regulates survivin stability through the Raf-1/ERK pathway in insulin-secreting pancreatic beta-cells. BMC Mol. Biol. 2010, 11, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, D.S.; Grossman, D.; Plescia, J.; Li, F.; Zhang, H.; Villa, A.; Tognin, S.; Marchisio, P.C.; Altieri, D.C. Regulation of apoptosis at cell division by p34cdc2 phosphorylation of survivin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 13103–13107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Tenev, T.; Martins, L.M.; Downward, J.; Lemoine, N.R. The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway regulates survivin degradation in a cell cycle-dependent manner. J. Cell Sci. 2000, 113, 4363–4371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.; Kim, W.K.; Kwon, Y.; Jang, M.; Bauer, S.; Kim, H. Survivin is a novel transcription regulator of KIT and is downregulated by miRNA-494 in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Int. J. Cancer 2018, 142, 2080–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohi, T.; Xia, F.; Altieri, D.C. Compartmentalized phosphorylation of IAP by protein kinase A regulates cytoprotection. Mol. Cell 2007, 27, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Holloway, M.P.; Ma, L.; Cooper, Z.A.; Riolo, M.; Samkari, A.; Elenitoba-Johnson, K.S.; Chin, Y.E.; Altura, R.A. Acetylation directs survivin nuclear localization to repress STAT3 oncogenic activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 36129–36137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vong, Q.P.; Cao, K.; Li, H.Y.; Iglesias, P.A.; Zheng, Y. Chromosome alignment and segregation regulated by ubiquitination of survivin. Science 2005, 310, 1499–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickramasinghe, V.O.; Laskey, R.A. Control of mammalian gene expression by selective mRNA export. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2015, 16, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebauer, F.; Hentze, M.W. Molecular mechanisms of translational control. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004, 5, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leppek, K.; Das, R.; Barna, M. Functional 5′ UTR mRNA structures in eukaryotic translation regulation and how to find them. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 158–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, S.E.; Hillner, P.E.; Vale, R.D.; Sachs, A.B. Circularization of mRNA by eukaryotic translation initiation factors. Mol. Cell 1998, 2, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero, H.; Perez-Gil, G.; Sampieri, C.L. Eukaryotic initiation factor 4A (eIF4A) during viral infections. Virus Genes 2019, 55, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, M. Structural features in eukaryotic mRNAs that modulate the initiation of translation. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 19867–19870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badura, M.; Braunstein, S.; Zavadil, J.; Schneider, R.J. DNA damage and eIF4G1 in breast cancer cells reprogram translation for survival and DNA repair mRNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 18767–18772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, S.Y.; Maizel, J.V., Jr. A common RNA structural motif involved in the internal initiation of translation of cellular mRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 25, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spriggs, K.A.; Bushell, M.; Mitchell, S.A.; Willis, A.E. Internal ribosome entry segment-mediated translation during apoptosis: The role of IRES-trans-acting factors. Cell Death Differ. 2005, 12, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherrill, K.W.; Byrd, M.P.; Van Eden, M.E.; Lloyd, R.E. BCL-2 translation is mediated via internal ribosome entry during cell stress. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 29066–29074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.Q.; Halaby, M.J.; Zhang, Y. The identification of an internal ribosomal entry site in the 5′-untranslated region of p53 mRNA provides a novel mechanism for the regulation of its translation following DNA damage. Oncogene 2006, 25, 4613–4619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palavecino, C.E.; Carrasco-Veliz, N.; Quest, A.F.G.; Garrido, M.P.; Valenzuela-Valderrama, M. The 5′ untranslated region of the anti-apoptotic protein Survivin contains an inhibitory upstream AUG codon. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 526, 898–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejos, M.; Carvajal, F.; Pino, K.; Navarrete, C.; Ferres, M.; Huidobro-Toro, J.P.; Sargueil, B.; Lopez-Lastra, M. Functional and structural analysis of the internal ribosome entry site present in the mRNA of natural variants of the HIV-1. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e35031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasey, A.; Lopez-Lastra, M.; Ohlmann, T.; Beerens, N.; Berkhout, B.; Darlix, J.L.; Sonenberg, N. The leader of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genomic RNA harbors an internal ribosome entry segment that is active during the G2/M phase of the cell cycle. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 3939–3949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejos, M.; Deforges, J.; Plank, T.D.; Letelier, A.; Ramdohr, P.; Abraham, C.G.; Valiente-Echeverria, F.; Kieft, J.S.; Sargueil, B.; Lopez-Lastra, M. Activity of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 cell cycle-dependent internal ribosomal entry site is modulated by IRES trans-acting factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 6186–6200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela-Valderrama, M.; Cerda-Opazo, P.; Backert, S.; Gonzalez, M.F.; Carrasco-Veliz, N.; Jorquera-Cordero, C.; Wehinger, S.; Canales, J.; Bravo, D.; Quest, A.F.G. The Helicobacter pylori Urease Virulence Factor Is Required for the Induction of Hypoxia-Induced Factor-1alpha in Gastric Cells. Cancers 2019, 11, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, M.; Glorieux, C.; Stockis, J.; Sid, B.; Sandoval, J.M.; Felipe, K.B.; Kviecinski, M.R.; Verrax, J.; Buc Calderon, P. Retinoic acid synergizes ATO-mediated cytotoxicity by precluding Nrf2 activity in AML cells. Br. J. Cancer 2014, 111, 874–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares, E.; Landry, D.M.; Caceres, C.J.; Pino, K.; Rossi, F.; Navarrete, C.; Huidobro-Toro, J.P.; Thompson, S.R.; Lopez-Lastra, M. The 5′ untranslated region of the human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 mRNA enables cap-independent translation initiation. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 5936–5955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejos, M.; Ramdohr, P.; Valiente-Echeverria, F.; Tapia, K.; Rodriguez, F.E.; Lowy, F.; Huidobro-Toro, J.P.; Dangerfield, J.A.; Lopez-Lastra, M. The 5′-untranslated region of the mouse mammary tumor virus mRNA exhibits cap-independent translation initiation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, 618–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvajal, F.; Vallejos, M.; Walters, B.; Contreras, N.; Hertz, M.I.; Olivares, E.; Caceres, C.J.; Pino, K.; Letelier, A.; Thompson, S.R.; et al. Structural domains within the HIV-1 mRNA and the ribosomal protein S25 influence cap-independent translation initiation. FEBS J. 2016, 283, 2508–2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, F.L.; Smiley, J.; Russell, W.C.; Nairn, R. Characteristics of a human cell line transformed by DNA from human adenovirus type 5. J. Gen. Virol. 1977, 36, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caceres, C.J.; Angulo, J.; Lowy, F.; Contreras, N.; Walters, B.; Olivares, E.; Allouche, D.; Merviel, A.; Pino, K.; Sargueil, B.; et al. Non-canonical translation initiation of the spliced mRNA encoding the human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 basic leucine zipper protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, 11030–11047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, M.K.; Padilla, O.R.; Zhu, E. Survivin is a key factor in the differential susceptibility of gastric endothelial and epithelial cells to alcohol-induced injury. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2010, 61, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Liu, K.; Lu, F.; Zhai, C.; Cheng, F. Programmed cell death in Helicobacter pylori infection and related gastric cancer. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1416819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, S.A.; Edelman, G.M.; Mauro, V.P. A 9-nt segment of a cellular mRNA can function as an internal ribosome entry site (IRES) and when present in linked multiple copies greatly enhances IRES activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 1536–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.K.; Scott, M.P.; Sarnow, P. Homeotic gene Antennapedia mRNA contains 5′-noncoding sequences that confer translational initiation by internal ribosome binding. Genes Dev. 1992, 6, 1643–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godet, A.C.; David, F.; Hantelys, F.; Tatin, F.; Lacazette, E.; Garmy-Susini, B.; Prats, A.C. IRES Trans-Acting Factors, Key Actors of the Stress Response. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gendron, K.; Ferbeyre, G.; Heveker, N.; Brakier-Gingras, L. The activity of the HIV-1 IRES is stimulated by oxidative stress and controlled by a negative regulatory element. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 902–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baugh, M.A. HIV: Reactive oxygen species, enveloped viruses and hyperbaric oxygen. Med. Hypotheses 2000, 55, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Lin, Z.; Zhao, M.; Xu, T.; Wang, C.; Hua, L.; Wang, H.; Xia, H.; Zhu, B. Silver Nanoparticle Based Codelivery of Oseltamivir to Inhibit the Activity of the H1N1 Influenza Virus through ROS-Mediated Signaling Pathways. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 24385–24393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badawi, A.; Biyanee, A.; Nasrullah, U.; Winslow, S.; Schmid, T.; Pfeilschifter, J.; Eberhardt, W. Inhibition of IRES-dependent translation of caspase-2 by HuR confers chemotherapeutic drug resistance in colon carcinoma cells. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 18367–18385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, B.; Harris, B.R.; Liu, Y.; Deng, Y.; Gradilone, S.A.; Cleary, M.P.; Liu, J.; Yang, D.Q. Targeting IRES-Mediated p53 Synthesis for Cancer Diagnosis and Therapeutics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belot, A.; Gourbeyre, O.; Palin, A.; Rubio, A.; Largounez, A.; Besson-Fournier, C.; Latour, C.; Lorgouilloux, M.; Gallitz, I.; Montagner, A.; et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress controls iron metabolism through TMPRSS6 repression and hepcidin mRNA stabilization by RNA-binding protein HuR. Haematologica 2021, 106, 1202–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liwak, U.; Thakor, N.; Jordan, L.E.; Roy, R.; Lewis, S.M.; Pardo, O.E.; Seckl, M.; Holcik, M. Tumor suppressor PDCD4 represses internal ribosome entry site-mediated translation of antiapoptotic proteins and is regulated by S6 kinase 2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2012, 32, 1818–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz, P.; Román, A.; Carrasco-Aviño, G.; Rodriguez, A.; Corvalán, A.; Lavandero, S.; Quest, A.F. Helicobacter pylori Infection Triggers PERK-Associated Survivin Loss in Gastric Tissue Samples and Cell Lines. J. Cancer Sci. Clin. Ther. 2021, 5, 063–082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Yang, S.M.; Zhang, H.P.; Yang, Y.; Sun, S.B.; Chang, J.P.; Tao, X.C.; Yang, T.Y.; Liu, C.; Yang, Y.M. Endoplasmic reticulum stress mediates the arsenic trioxide-induced apoptosis in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2015, 68, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozpolat, B.; Akar, U.; Tekedereli, I.; Alpay, S.N.; Barria, M.; Gezgen, B.; Zhang, N.; Coombes, K.; Kornblau, S.; Lopez-Berestein, G. PKCdelta Regulates Translation Initiation through PKR and eIF2alpha in Response to Retinoic Acid in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cells. Leuk. Res. Treat. 2012, 2012, 482905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, M.A.; Redondo, N.; Garcia-Moreno, M.; Carrasco, L. Phosphorylation of eIF2alpha is responsible for the failure of the picornavirus internal ribosome entry site to direct translation from Sindbis virus replicons. J. Gen. Virol. 2013, 94, 796–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boye, E.; Grallert, B. eIF2alpha phosphorylation and the regulation of translation. Curr. Genet. 2020, 66, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Hu, W.; Ouyang, Q.; Zhang, S.; He, L.; Chen, W.; Li, X.; Hu, C. Helicobacter pylori infection induces stem cell-like properties in Correa cascade of gastric cancer. Cancer Lett. 2022, 542, 215764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, S.Y.; Zhu, L.; Wu, L.Y.; Liu, H.R.; Ma, X.P.; Li, Q.; Wu, M.D.; Wang, W.J.; Li, J.; Wu, H.G. Helicobacter pylori-positive chronic atrophic gastritis and cellular senescence. Helicobacter 2023, 28, e12944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugano, K.; Moss, S.F.; Kuipers, E.J. Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia: Real Culprit or Innocent Bystander as a Precancerous Condition for Gastric Cancer? Gastroenterology 2023, 165, 1352–1366.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlmann, T.; Mengardi, C.; Lopez-Lastra, M. Translation initiation of the HIV-1 mRNA. Translation 2014, 2, e960242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rubilar, M.; Carrasco-Véliz, N.; Garrido, M.P.; Silva, M.I.; Quest, A.F.G.; González, M.F.; Palacios, E.; Villena, J.; Montenegro, I.; Valenzuela-Valderrama, M. The Cap-Independent Translation of Survivin 5′UTR and HIV-1 IRES Sequences Is Inhibited by Oxidative Stress Produced by H. pylori Gamma-Glutamyl Transpeptidase Activity. Biomolecules 2026, 16, 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010164

Rubilar M, Carrasco-Véliz N, Garrido MP, Silva MI, Quest AFG, González MF, Palacios E, Villena J, Montenegro I, Valenzuela-Valderrama M. The Cap-Independent Translation of Survivin 5′UTR and HIV-1 IRES Sequences Is Inhibited by Oxidative Stress Produced by H. pylori Gamma-Glutamyl Transpeptidase Activity. Biomolecules. 2026; 16(1):164. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010164

Chicago/Turabian StyleRubilar, Mariaignacia, Nicolás Carrasco-Véliz, Maritza P. Garrido, María I. Silva, Andrew F. G. Quest, María Fernanda González, Esteban Palacios, Joan Villena, Iván Montenegro, and Manuel Valenzuela-Valderrama. 2026. "The Cap-Independent Translation of Survivin 5′UTR and HIV-1 IRES Sequences Is Inhibited by Oxidative Stress Produced by H. pylori Gamma-Glutamyl Transpeptidase Activity" Biomolecules 16, no. 1: 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010164

APA StyleRubilar, M., Carrasco-Véliz, N., Garrido, M. P., Silva, M. I., Quest, A. F. G., González, M. F., Palacios, E., Villena, J., Montenegro, I., & Valenzuela-Valderrama, M. (2026). The Cap-Independent Translation of Survivin 5′UTR and HIV-1 IRES Sequences Is Inhibited by Oxidative Stress Produced by H. pylori Gamma-Glutamyl Transpeptidase Activity. Biomolecules, 16(1), 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010164