Serum CCL18 May Reflect Multiorgan Involvement with Poor Outcome in Systemic Sclerosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics

2.2. Patients and Controls

2.3. Organ Involvement

2.4. Biomarker Tests

2.5. Survival Analysis

2.6. Disease Activity

2.7. Statistical Analysis

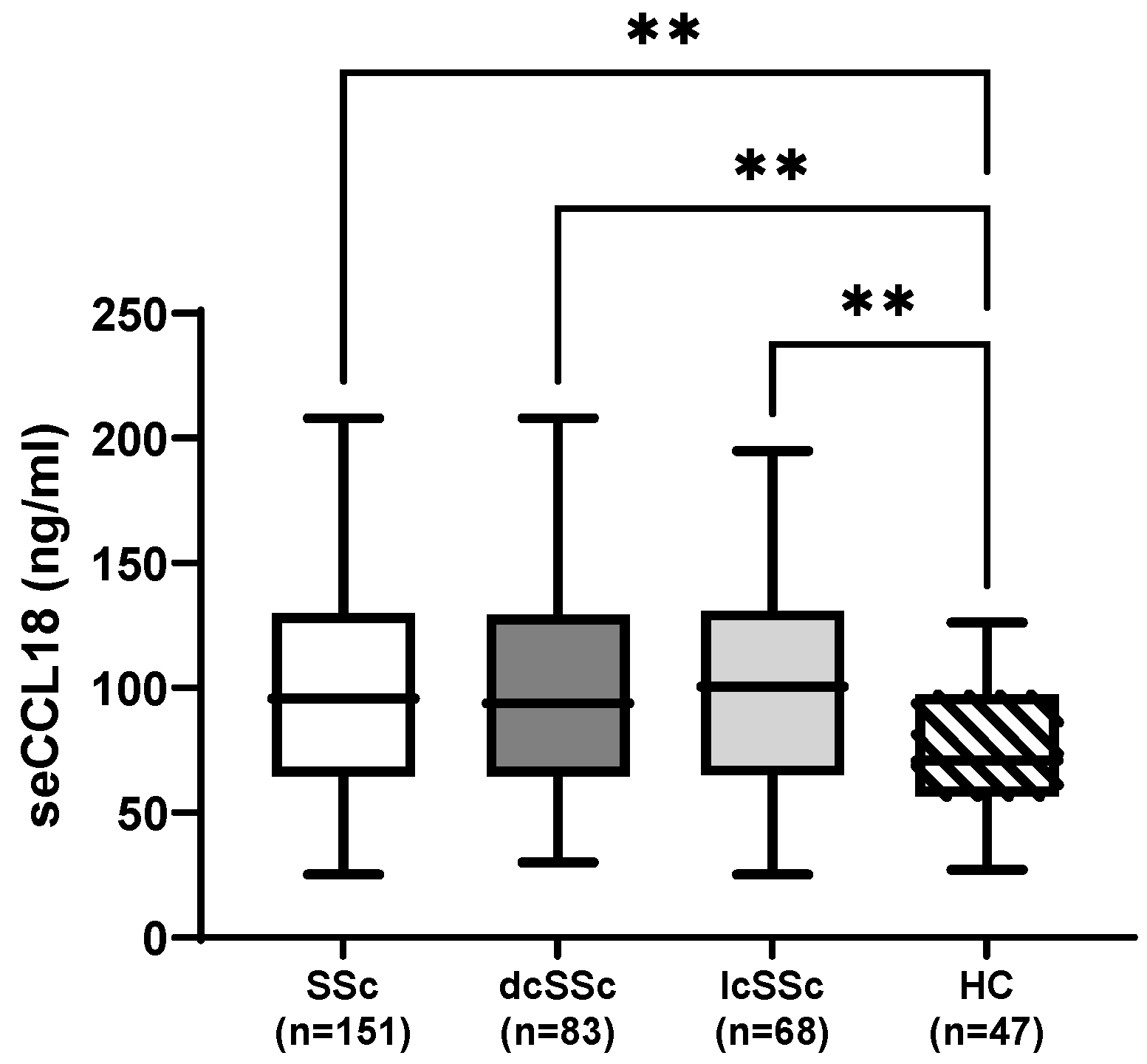

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics and Organ Manifestations

3.2. Demographics and Disease Duration

3.3. SSc-ILD and Functional Exercise Capacity

3.4. Non-Pulmonary Organ Involvement

3.4.1. Cardiac

3.4.2. Gastrointestinal

3.4.3. Musculoskeletal and Skin

3.4.4. Laboratory Parameters

3.4.5. Other

3.5. Disease Activity

3.6. Survival Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACA | Anticentromere antibody |

| ACEi | Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor |

| ACR | American College of Rheumatology |

| AECG | American–European Consensus Group |

| ANA | Antinuclear antibody |

| ANCA | Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody |

| ARB | Angiotensin II receptor blocker |

| ATA | Anti-topoisomerase I antibody |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| dcSSc | Diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis |

| DLCO | Diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide |

| DU | Digital ulcer |

| ECG | Electrocardiography |

| EF | Ejection fraction |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| EMR | Electronic medical record |

| ESR | Erythrocyte sedimentation rate |

| EULAR | European League Against Rheumatism |

| EUSTAR | European Scleroderma Trials and Research Group |

| EUSTAR-AI | EUSTAR Activity Index |

| FVC | Forced vital capacity |

| GERD | Gastroesophageal reflux disease |

| GI | Gastrointestinal |

| HC | Healthy control |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| HRCT | High-resolution computed tomography |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| lcSSc | Limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis |

| LOX | Lysyl oxidase |

| LVDD | Left ventricular diastolic dysfunction |

| LVMi | Left ventricular mass index |

| mPAP | Mean pulmonary arterial pressure |

| mRSS | Modified Rodnan Skin Score |

| NHIF | National Health Insurance Fund |

| PAH | Pulmonary arterial hypertension |

| PAWP | Pulmonary artery wedge pressure |

| PVR | Pulmonary vascular resistance |

| RHC | Right heart catheterization |

| RNA-Pol III | RNA polymerase III antibody |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| seCCL18 | Serum C–C motif chemokine ligand 18 |

| SP-D | Surfactant protein D |

| SSc | Systemic sclerosis |

| SSc-ILD | Systemic sclerosis–associated interstitial lung disease |

| TFR | Tendon friction rub |

| TLC | Total lung capacity |

| TTE | Transthoracic echocardiography |

| UCLA-GIT 2.0 | University of California Los Angeles Gastrointestinal Tract 2.0 questionnaire |

| WU | Wood unit |

| 6MWT | Six-minute walk test |

References

- Denton, C.P.; Khanna, D. Systemic Sclerosis. Lancet 2017, 390, 1685–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeRoy, E.C.; Black, C.; Fleischmajer, R.; Jablonska, S.; Krieg, T.; Medsger, T.A.; Rowell, N.; Wollheim, F. Scleroderma (Systemic Sclerosis): Classification, Subsets and Pathogenesis. J. Rheumatol. 1988, 15, 202–205. [Google Scholar]

- Bournia, V.-K.; Fragoulis, G.E.; Mitrou, P.; Mathioudakis, K.; Tsolakidis, A.; Konstantonis, G.; Vourli, G.; Paraskevis, D.; Tektonidou, M.G.; Sfikakis, P.P. All-Cause Mortality in Systemic Rheumatic Diseases under Treatment Compared with the General Population, 2015–2019. RMD Open 2021, 7, e001694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nihtyanova, S.I.; Tang, E.C.; Coghlan, J.G.; Wells, A.U.; Black, C.M.; Denton, C.P. Improved Survival in Systemic Sclerosis Is Associated with Better Ascertainment of Internal Organ Disease: A Retrospective Cohort Study. QJM 2010, 103, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saketkoo, L.A.; Frech, T.; Varjú, C.; Domsic, R.; Farrell, J.; Gordon, J.K.; Mihai, C.; Sandorfi, N.; Shapiro, L.; Poole, J.; et al. A Comprehensive Framework for Navigating Patient Care in Systemic Sclerosis: A Global Response to the Need for Improving the Practice of Diagnostic and Preventive Strategies in SSc. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2021, 35, 101707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fields, A.; Potel, K.N.; Cabuhal, R.; Aziri, B.; Stewart, I.D.; Schock, B.C. Mediators of Systemic Sclerosis-Associated Interstitial Lung Disease (SSc-ILD): Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses. Thorax 2022, 78, 799–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, D.; Tashkin, D.P.; Denton, C.P.; Renzoni, E.A.; Desai, S.R.; Varga, J. Etiology, Risk Factors, and Biomarkers in Systemic Sclerosis with Interstitial Lung Disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 201, 650–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Affandi, A.J.; Radstake, T.R.D.J.; Marut, W. Update on Biomarkers in Systemic Sclerosis: Tools for Diagnosis and Treatment. Semin. Immunopathol. 2015, 37, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimar, D.; Rosner, I.; Nov, Y.; Slobodin, G.; Rozenbaum, M.; Halasz, K.; Haj, T.; Jiries, N.; Kaly, L.; Boulman, N.; et al. Brief Report: Lysyl Oxidase Is a Potential Biomarker of Fibrosis in Systemic Sclerosis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014, 66, 726–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Bon, L.; Affandi, A.J.; Broen, J.; Christmann, R.B.; Marijnissen, R.J.; Stawski, L.; Farina, G.A.; Stifano, G.; Mathes, A.L.; Cossu, M.; et al. Proteome-Wide Analysis and CXCL4 as a Biomarker in Systemic Sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manetti, M.; Guiducci, S.; Romano, E.; Bellando-Randone, S.; Conforti, M.L.; Ibba-Manneschi, L.; Matucci-Cerinic, M. Increased Serum Levels and Tissue Expression of Matrix Metalloproteinase-12 in Patients with Systemic Sclerosis: Correlation with Severity of Skin and Pulmonary Fibrosis and Vascular Damage. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2012, 71, 1064–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaug, B.; Assassi, S. Biomarkers in Systemic Sclerosis. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2019, 31, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokeerbux, M.R.; Giovannelli, J.; Dauchet, L.; Mouthon, L.; Agard, C.; Lega, J.C.; Allanore, Y.; Jego, P.; Bienvenu, B.; Berthier, S.; et al. Survival and Prognosis Factors in Systemic Sclerosis: Data of a French Multicenter Cohort, Systematic Review, and Meta-Analysis of the Literature. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2019, 21, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Hudson, M.; Baron, M.; Carreira, P.; Stevens, W.; Rabusa, C.; Tatibouet, S.; Carmona, L.; Joven, B.E.; Huq, M.; et al. Early Mortality in a Multinational Systemic Sclerosis Inception Cohort. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017, 69, 1067–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyndall, A.J.; Bannert, B.; Vonk, M.; Airò, P.; Cozzi, F.; Carreira, P.E.; Bancel, D.F.; Allanore, Y.; Müller-Ladner, U.; Distler, O.; et al. Causes and Risk Factors for Death in Systemic Sclerosis: A Study from the EULAR Scleroderma Trials and Research (EUSTAR) Database. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010, 69, 1809–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czirják, L.; Nagy, Z.; Szegedi, G. Survival Analysis of 118 Patients with Systemic Sclerosis. J. Intern. Med. 1993, 234, 335–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czirják, L.; Kumánovics, G.; Varjú, C.; Nagy, Z.; Pákozdi, A.; Szekanecz, Z.; Szucs, G. Survival and Causes of Death in 366 Hungarian Patients with Systemic Sclerosis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2008, 67, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagy, G.; Minier, T.; Varjú, C.; Faludi, R.; Kovács, K.T.; Lóránd, V.; Hermann, V.; Czirják, L.; Kumánovics, G. The Presence of Small Joint Contractures Is a Risk Factor for Survival in 439 Patients with Systemic Sclerosis. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2017, 35, 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Kodera, M.; Hasegawa, M.; Komura, K.; Yanaba, K.; Takehara, K.; Sato, S. Serum Pulmonary and Activation-Regulated Chemokine/CCL18 Levels in Patients with Systemic Sclerosis: A Sensitive Indicator of Active Pulmonary Fibrosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005, 52, 2889–2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutyser, E.; Richmond, A.; Van Damme, J. Involvement of CC Chemokine Ligand 18 (CCL18) in Normal and Pathological Processes. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2005, 78, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasse, A.; Pechkovsky, D.V.; Toews, G.B.; Schäfer, M.; Eggeling, S.; Ludwig, C.; Germann, M.; Kollert, F.; Zissel, G.; Müller-Quernheim, J. CCL18 as an Indicator of Pulmonary Fibrotic Activity in Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias and Systemic Sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 56, 1685–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schraufstatter, I.; Takamori, H.; Sikora, L.; Sriramarao, P.; DiScipio, R.G. Eosinophils and Monocytes Produce Pulmonary and Activation-Regulated Chemokine, Which Activates Cultured Monocytes/Macrophages. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2004, 286, L494–L501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsicopoulos, A.; Chang, Y.; Ait Yahia, S.; de Nadai, P.; Chenivesse, C. Role of CCL18 in Asthma and Lung Immunity. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2013, 43, 716–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Lieshout, A.W.T.; Fransen, J.; Flendrie, M.; Eijsbouts, A.M.M.; van den Hoogen, F.H.J.; van Riel, P.L.C.M.; Radstake, T.R.D.J. Circulating Levels of the Chemokine CCL18 but Not CXCL16 Are Elevated and Correlate with Disease Activity in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2007, 66, 1334–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Momohara, S.; Okamoto, H.; Iwamoto, T.; Mizumura, T.; Ikari, K.; Kawaguchi, Y.; Takeuchi, M.; Kamatani, N.; Tomatsu, T. High CCL18/PARC Expression in Articular Cartilage and Synovial Tissue of Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. J. Rheumatol. 2007, 34, 266–271. [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama, M.; Yasuoka, H.; Yoshimoto, K.; Takeuchi, T. CC-Chemokine Ligand 18 Is a Useful Biomarker Associated with Disease Activity in IgG4-Related Disease. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2018, 77, 1386–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brix, S.R.; Stege, G.; Disteldorf, E.; Hoxha, E.; Krebs, C.; Krohn, S.; Otto, B.; Klätschke, K.; Herden, E.; Heymann, F.; et al. CC Chemokine Ligand 18 in ANCA-Associated Crescentic GN. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2015, 26, 2105–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasse, A.; Probst, C.; Bargagli, E.; Zissel, G.; Toews, G.B.; Flaherty, K.R.; Olschewski, M.; Rottoli, P.; Müller-Quernheim, J. Serum CC-Chemokine Ligand 18 Concentration Predicts Outcome in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2009, 179, 717–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiev, K.P.; Hua-Huy, T.; Kettaneh, A.; Gain, M.; Duong-Quy, S.; Tolédano, C.; Cabane, J.; Dinh-Xuan, A.T. Serum CC Chemokine Ligand-18 Predicts Lung Disease Worsening in Systemic Sclerosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2011, 38, 1355–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schupp, J.; Becker, M.; Günther, J.; Müller-Quernheim, J.; Riemekasten, G.; Prasse, A. Serum CCL18 Is Predictive for Lung Disease Progression and Mortality in Systemic Sclerosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2014, 43, 1530–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhai, M.; Hoffmann-Vold, A.M.; Avouac, J.; Pezet, S.; Cauvet, A.; Leblond, A.; Fretheim, H.; Garen, T.; Kuwana, M.; Molberg, Ø.; et al. Performance of Candidate Serum Biomarkers for Systemic Sclerosis-Associated Interstitial Lung Disease. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019, 71, 972–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Györfi, A.-H.; Filla, T.; Dickel, N.; Möller, F.; Li, Y.-N.; Bergmann, C.; Matei, A.-E.; Harrer, T.; Kunz, M.; Schett, G.; et al. Performance of Serum Biomarkers Reflective of Different Pathogenic Processes in Systemic Sclerosis-Associated Interstitial Lung Disease. Rheumatology 2024, 63, 962–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, M.J.S.; Jee, A.S.; Hansen, D.; Proudman, S.; Youssef, P.; Kenna, T.J.; Stevens, W.; Nikpour, M.; Sahhar, J.; Corte, T.J. Multiple Serum Biomarkers Associate with Mortality and Interstitial Lung Disease Progression in Systemic Sclerosis. Rheumatology 2024, 63, 2981–2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volkmann, E.R.; Tashkin, D.P.; Kuwana, M.; Li, N.; Roth, M.D.; Charles, J.; Hant, F.N.; Bogatkevich, G.S.; Akter, T.; Kim, G.; et al. Progression of Interstitial Lung Disease in Systemic Sclerosis: The Importance of Pneumoproteins Krebs von Den Lungen 6 and CCL18. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019, 71, 2059–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, D.; Denton, C.P.; Jahreis, A.; van Laar, J.M.; Frech, T.M.; Anderson, M.E.; Baron, M.; Chung, L.; Fierlbeck, G.; Lakshminarayanan, S.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Subcutaneous Tocilizumab in Adults with Systemic Sclerosis (FaSScinate): A Phase 2, Randomised, Controlled Trial. Lancet 2016, 387, 2630–2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. STROBE Initiative the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies. Lancet 2007, 370, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Den Hoogen, F.; Khanna, D.; Fransen, J.; Johnson, S.R.; Baron, M.; Tyndall, A.; Matucci-Cerinic, M.; Naden, R.P.; Medsger, T.A.; Carreira, P.E.; et al. 2013 Classification Criteria for Systemic Sclerosis: An American College of Rheumatology/European League against Rheumatism Collaborative Initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 2013, 65, 2737–2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeRoy, E.C.; Medsger, T.A. Criteria for the Classification of Early Systemic Sclerosis. J. Rheumatol. 2001, 28, 1573–1576. [Google Scholar]

- Distler, O.; Brown, K.K.; Distler, J.H.W.; Assassi, S.; Maher, T.M.; Cottin, V.; Varga, J.; Coeck, C.; Gahlemann, M.; Sauter, W.; et al. Design of a Randomised, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial of Nintedanib in Patients with Systemic Sclerosis-Associated Interstitial Lung Disease (SENSCISTM). Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2017, 35, 75–81. [Google Scholar]

- Bálint, Z.; Farkas, H.; Farkas, N.; Minier, T.; Kumánovics, G.; Horváth, K.; Solyom, A.I.; Czirják, L.; Varjú, C. A Three-Year Follow-up Study of the Development of Joint Contractures in 131 Patients with Systemic Sclerosis. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2014, 32, 68–74. [Google Scholar]

- Vitali, C.; Bombardieri, S.; Jonsson, R.; Moutsopoulos, H.M.; Alexander, E.L.; Carsons, S.E.; Daniels, T.E.; Fox, P.C.; Fox, R.I.; Kassan, S.S.; et al. Classification Criteria for Sjögren’s Syndrome: A Revised Version of the European Criteria Proposed by the American-European Consensus Group. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2002, 61, 554–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkmann, E.R.; McMahan, Z. Gastrointestinal Involvement in Systemic Sclerosis: Pathogenesis, Assessment and Treatment. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2022, 34, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonneau, G.; Robbins, I.M.; Beghetti, M.; Channick, R.N.; Delcroix, M.; Denton, C.P.; Elliott, C.G.; Gaine, S.P.; Gladwin, M.T.; Jing, Z.-C.; et al. Updated Clinical Classification of Pulmonary Hypertension. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009, 54, S43–S54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruni, C.; Ross, L. Cardiac Involvement in Systemic Sclerosis: Getting to the Heart of the Matter. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2021, 35, 101668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodworth, T.G.; Suliman, Y.A.; Li, W.; Furst, D.E.; Clements, P. Scleroderma Renal Crisis and Renal Involvement in Systemic Sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2016, 12, 678–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enright, P.L.; Sherrill, D.L. Reference Equations for the Six-Minute Walk in Healthy Adults. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1998, 158, 1384–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valentini, G.; Iudici, M.; Walker, U.A.; Jaeger, V.K.; Baron, M.; Carreira, P.; Czirják, L.; Denton, C.P.; Distler, O.; Hachulla, E.; et al. The European Scleroderma Trials and Research Group (EUSTAR) Task Force for the Development of Revised Activity Criteria for Systemic Sclerosis: Derivation and Validation of a Preliminarily Revised EUSTAR Activity Index. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2017, 76, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schraufstatter, I.U.; Zhao, M.; Khaldoyanidi, S.K.; Discipio, R.G. The Chemokine CCL18 Causes Maturation of Cultured Monocytes to Macrophages in the M2 Spectrum. Immunology 2012, 135, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann-Vold, A.-M.; Tennøe, A.H.; Garen, T.; Midtvedt, Ø.; Abraityte, A.; Aaløkken, T.M.; Lund, M.B.; Brunborg, C.; Aukrust, P.; Ueland, T.; et al. High Level of Chemokine CCL18 Is Associated with Pulmonary Function Deterioration, Lung Fibrosis Progression, and Reduced Survival in Systemic Sclerosis. Chest 2016, 150, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, C.; Zhu, M.; Lieu, M.; Moodley, S.; Wang, Y.; McConaghy, T.; Larner, B.; Widdop, R.; Sobey, C.; Drummond, G.; et al. CCL18 as a Mediator of the Pro-Fibrotic Actions of M2 Macrophages in the Vessel Wall during Hypertension. FASEB J. 2017, 31, 825.2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd-Jones, D.M.; Evans, J.C.; Levy, D. Hypertension in Adults across the Age Spectrum: Current Outcomes and Control in the Community. JAMA 2005, 294, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elhai, M.; Avouac, J.; Allanore, Y. Circulating Lung Biomarkers in Idiopathic Lung Fibrosis and Interstitial Lung Diseases Associated with Connective Tissue Diseases: Where Do We Stand? Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2020, 50, 480–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bairkdar, M.; Chen, E.Y.-T.; Dickman, P.W.; Hesselstrand, R.; Westerlind, H.; Holmqvist, M. Survival in Swedish Patients with Systemic Sclerosis: A Nationwide Population-Based Matched Cohort Study. Rheumatology 2023, 62, 1170–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Almeida Chaves, S.; Porel, T.; Mounié, M.; Alric, L.; Astudillo, L.; Huart, A.; Lairez, O.; Michaud, M.; Prévot, G.; Ribes, D.; et al. Sine Scleroderma, Limited Cutaneous, and Diffused Cutaneous Systemic Sclerosis Survival and Predictors of Mortality. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2021, 23, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, W.A.; Fries, J.F.; Masi, A.T.; Shulman, L.E. Pathologic Observations in Systemic Sclerosis (Scleroderma). A Study of Fifty-Eight Autopsy Cases and Fifty-Eight Matched Controls. Am. J. Med. 1969, 46, 428–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Singh, J.; Kedika, R.; Mendoza, F.; Jimenez, S.A.; Blomain, E.S.; DiMarino, A.J.; Cohen, S.; Rattan, S. Role of Muscarinic-3 Receptor Antibody in Systemic Sclerosis: Correlation with Disease Duration and Effects of IVIG. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2016, 310, G1052–G1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, F.A.; DiMarino, A.; Cohen, S.; Adkins, C.; Abdelbaki, S.; Rattan, S.; Cao, C.; Denuna-Rivera, S.; Jimenez, S.A. Treatment of Severe Swallowing Dysfunction in Systemic Sclerosis with IVIG: Role of Antimuscarinic Antibodies. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swaminathan, S.; Goldblatt, F.; Dugar, M.; Gordon, T.P.; Roberts-Thomson, P.J. Prevalence of Sicca Symptoms in a South Australian Cohort with Systemic Sclerosis. Intern. Med. J. 2008, 38, 897–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SSc | dcSSc | lcSSc | |||||||

| n (%) | Elevated seCCL18 (>130 ng/mL) | Normal seCCL18 (≤130 ng/mL) | p | Elevated seCCL18 (>130 ng/mL) | Normal seCCL18 (≤130 ng/mL) | p | Elevated seCCL18 (>130 ng/mL) | Normal seCCL18 (≤130 ng/mL) | p |

| SSc-ILD | 30/37 * (81.1) | 69/114 (60.5) | 0.022 | 18/19 * (94.7) | 42/64 (65.6) | 0.013 | 12/18 (66.7) | 27/50 (54) | 0.351 |

| FVC < 70% | 6/36 * (16.7) | 4/114 (3.5) | 0.006 | 3/19 (15.8) | 4/64 (6.3) | 0.189 | 3/17 * (17.6) | 0/50 | 0.014 |

| DLCO < 70% | 29/36 * (80.6) | 62/114 (54.4) | 0.005 | 16/19 * (84.2) | 37/64 (57.8) | 0.035 | 13/17 (76.5) | 25/50 (50) | 0.057 |

| SSc | dcSSc | lcSSc | |||||||

| Clinical Feature, n (%) | Elevated seCCL18 (>130 ng/mL) | Normal seCCL18 (≤130 ng/mL) | p | Elevated seCCL18 (>130 ng/mL) | Normal seCCL18 (≤130 ng/mL) | p | Elevated seCCL18 (>130 ng/mL) | Normal seCCL18 (≤130 ng/mL) | p |

| Musculoskeletal | |||||||||

| Small joint contracture | 24/37 * (64.9) | 49/111 (44.1) | 0.029 | 14/19 (73.7) | 36/62 (58.1) | 0.220 | 10/18 * (55.6) | 13/49 (26.5) | 0.027 |

| TFR | 19/37 * (51.4) | 31/113 (27.4) | 0.007 | 12/19 * (63.2) | 23/63 (36.5) | 0.040 | 7/18 * (38.9) | 8/50 (16) | 0.045 |

| Vascular | |||||||||

| Digital ulcer ever | 15/37 (40.5) | 40/111 (36) | 0.623 | 7/19 (36.8) | 30/62 (48.4) | 0.377 | 8/18 * (44.4) | 10/49 (20.4) | 0.049 |

| Gastrointestinal | |||||||||

| GERD | 22/37 (59.5) | 91/114 * (79.8) | 0.013 | 10/19 (52.6) | 53/64 * (82.8) | 0.007 | 12/18 (66.7) | 38/50 (76) | 0.442 |

| Laboratory | |||||||||

| ATA positive | 15/37 * (40.5) | 25/114 (21.9) | 0.026 | 10/19 (52.6) | 22/64 (34.4) | 0.151 | 5/18 * (27.8) | 3/50 (6.0) | 0.014 |

| RNA-Pol III positive | 6/37 (16.2) | 9/111 (8.1) | 0.157 | 2/19 (10.5) | 7/62 (11.3) | 0.926 | 4/18 * (22.2) | 2/49 (4.1) | 0.040 |

| CRP > 5 mg/L | 19/37 * (51.4) | 22/114 (19.3) | <0.001 | 8/19 * (42.1) | 11/64 (17.2) | 0.023 | 11/18 * (61.1) | 11/50 (22) | 0.002 |

| ESR > 28 mm/h | 14/37 * (37.8) | 21/114 (18.4) | 0.015 | 8/19 * (42.1) | 10/64 (15.6) | 0.014 | 6/18 (33.3) | 11/50 (22) | 0.341 |

| Other | |||||||||

| Sicca symptoms | 17/37 (45.9) | 74/111 * (66.7) | 0.025 | 8/19 (42.1) | 36/62 (58.1) | 0.222 | 9/18 (50) | 38/49 * (77.6) | 0.029 |

| Currently on immunosuppressants | 25/37 * (67.6) | 48/114 (42.1) | 0.007 | 16/19 * (84.2) | 36/64 (56.3) | 0.027 | 9/18 * (50) | 12/50 (24) | 0.041 |

| Univariate Analysis (Kaplan–Meier) | ||

| Log Rank Chi-Square | p | |

| Elevated seCCL18 (>130 ng/mL) | 6.218 | 0.013 |

| SSc-ILD | 7.069 | 0.008 |

| DLCO < 80% | 6.047 | 0.014 |

| Arrhythmia (ECG or Holter monitor) | 6.659 | 0.010 |

| Six Minute Walk Test below lower limit of normal | 14.459 | <0.001 |

| Small joint contractures (joint < 75% range of motion) | 8.061 | 0.005 |

| Subcutaneous calcinosis | 4.393 | 0.036 |

| Low BMI (<18.5 kg/m2) or weight loss (10% in 1 year) due to malabsorption | 4.186 | 0.041 |

| Multivariate Cox regression (backward stepwise) | ||

| Overall mortality risk HR (95% CI) | p | |

| Six Minute Walk Test Reference (per 10% decrease) | 1.249 (1.046–1.490) | 0.014 |

| seCCL18 (per 1-SD increment) | 1.789 (1.133–2.824) | 0.013 |

| Decreasing DLCO (per 10% decrease) | 1.942 (1.321–2.857) | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Filipánits, K.; Nagy, G.; Jász, D.K.; Minier, T.; Simon, D.; Erdő-Bonyár, S.; Berki, T.; Kumánovics, G. Serum CCL18 May Reflect Multiorgan Involvement with Poor Outcome in Systemic Sclerosis. Biomolecules 2026, 16, 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010136

Filipánits K, Nagy G, Jász DK, Minier T, Simon D, Erdő-Bonyár S, Berki T, Kumánovics G. Serum CCL18 May Reflect Multiorgan Involvement with Poor Outcome in Systemic Sclerosis. Biomolecules. 2026; 16(1):136. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010136

Chicago/Turabian StyleFilipánits, Kristóf, Gabriella Nagy, Dávid Kurszán Jász, Tünde Minier, Diána Simon, Szabina Erdő-Bonyár, Tímea Berki, and Gábor Kumánovics. 2026. "Serum CCL18 May Reflect Multiorgan Involvement with Poor Outcome in Systemic Sclerosis" Biomolecules 16, no. 1: 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010136

APA StyleFilipánits, K., Nagy, G., Jász, D. K., Minier, T., Simon, D., Erdő-Bonyár, S., Berki, T., & Kumánovics, G. (2026). Serum CCL18 May Reflect Multiorgan Involvement with Poor Outcome in Systemic Sclerosis. Biomolecules, 16(1), 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010136