Comparison of In Vitro Multiple Physiological Activities of Cys–Tyr–Gly–Ser–Arg (CYGSR) Linear and Cyclic Peptides and Analysis Based on Molecular Docking

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Chemicals

2.1.2. Cell

2.1.3. Assay Kits

2.1.4. Instruments

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Synthesis of L-CR5

2.2.2. Cleavage of L-CR5

2.2.3. Cyclization of L-CR5

2.2.4. HPLC Purification and Analysis

2.2.5. MALDI-TOF MS

2.2.6. Cell Culture

2.2.7. Cell Viability

2.2.8. DPPH Assay

2.2.9. Tyrosinase Inhibition Assay

2.2.10. MMP-1 Expression Inhibition ELISA Assay

2.2.11. Determination of Protein Content

2.2.12. Data Analysis and Statistical Processing

2.2.13. Molecular Docking Simulation

3. Results

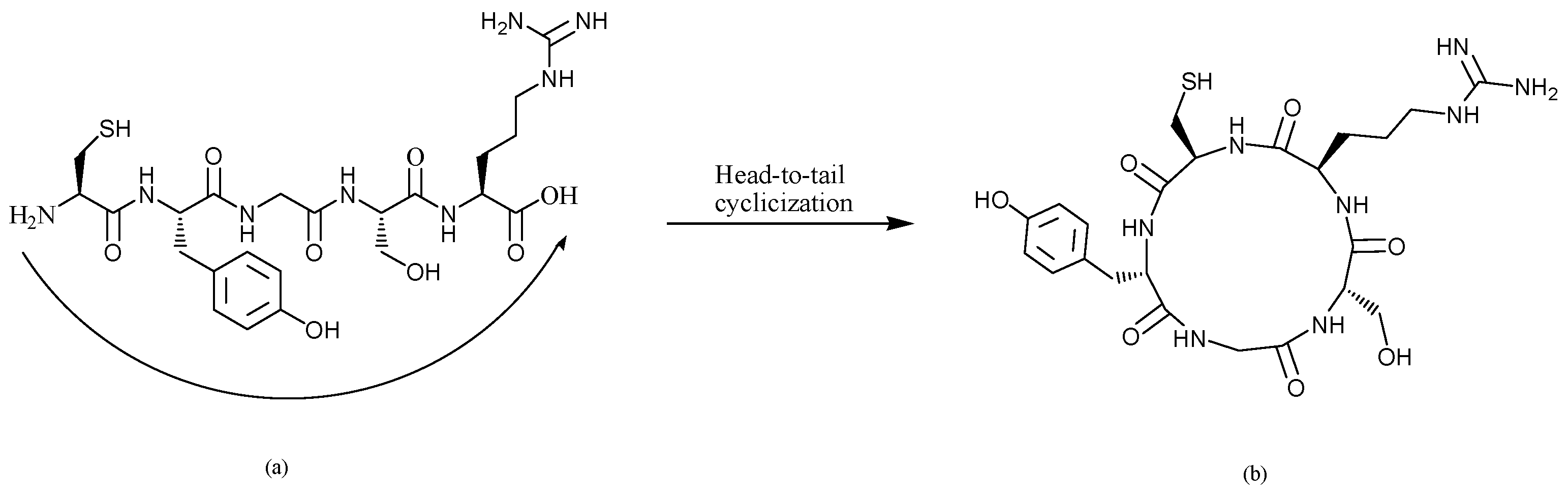

3.1. Structures of L-CR5 and C-CR5

3.2. Molecular Weight Determination of the Cyclic Peptide (C-CR5)

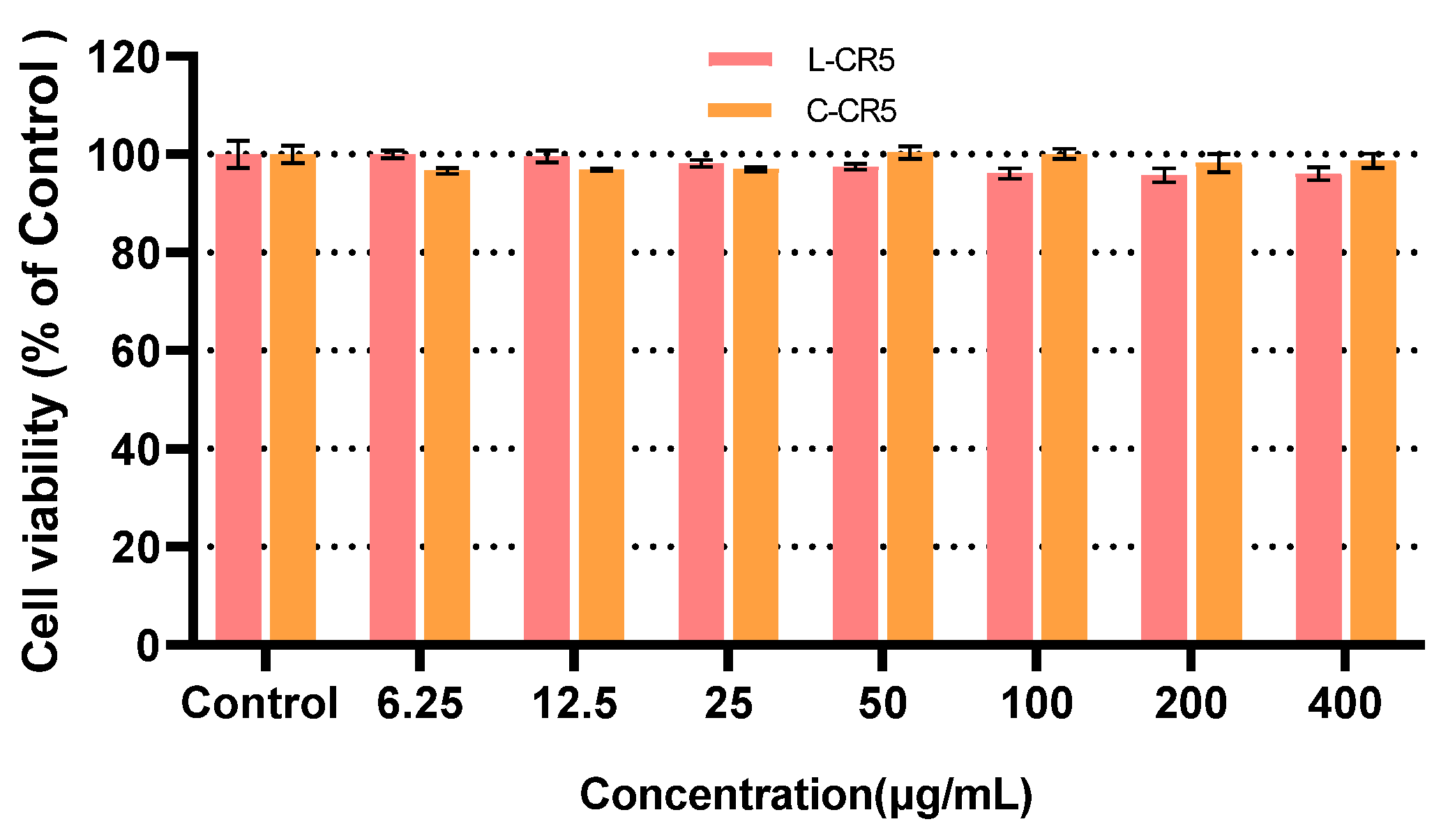

3.3. Cytotoxicity Evaluation of L-CR5 and C-CR5

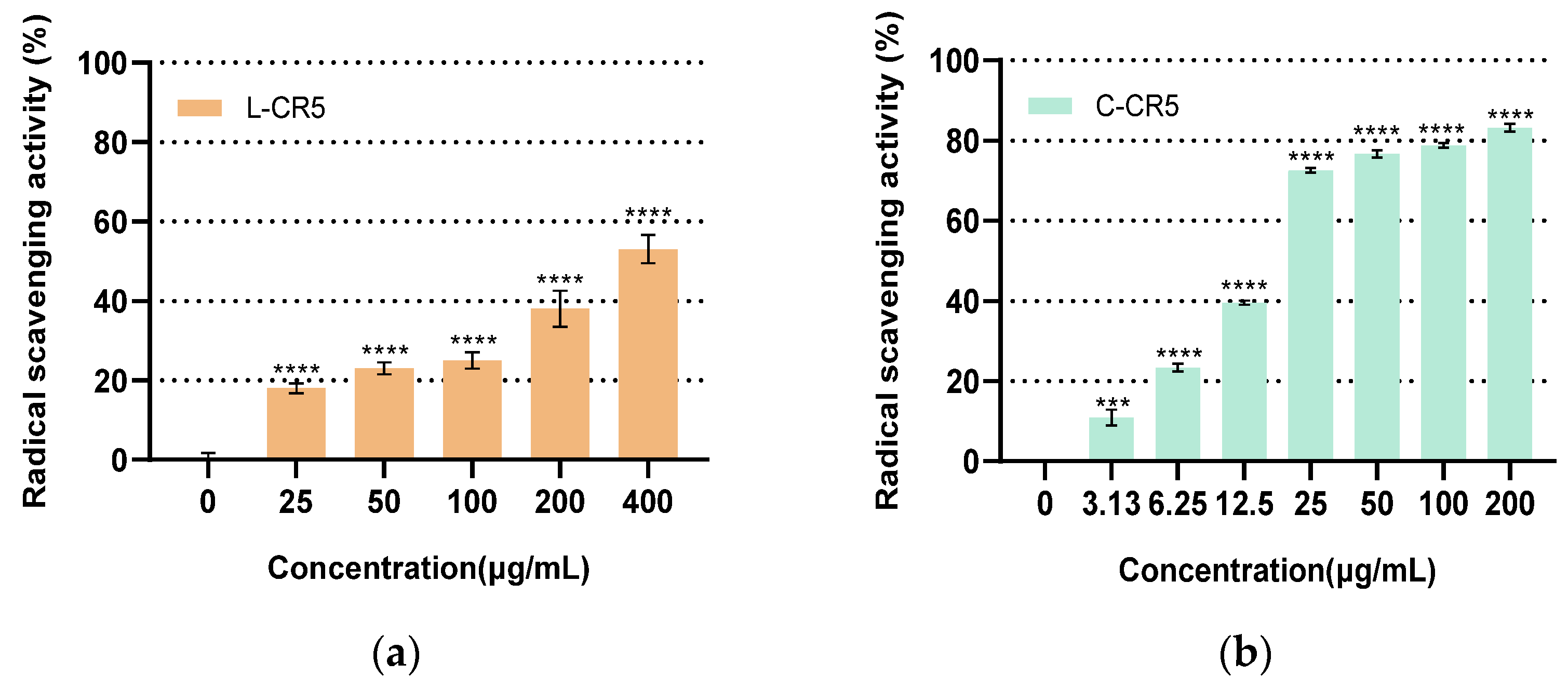

3.4. Comparison of DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity Between L-CR5 and C-CR5

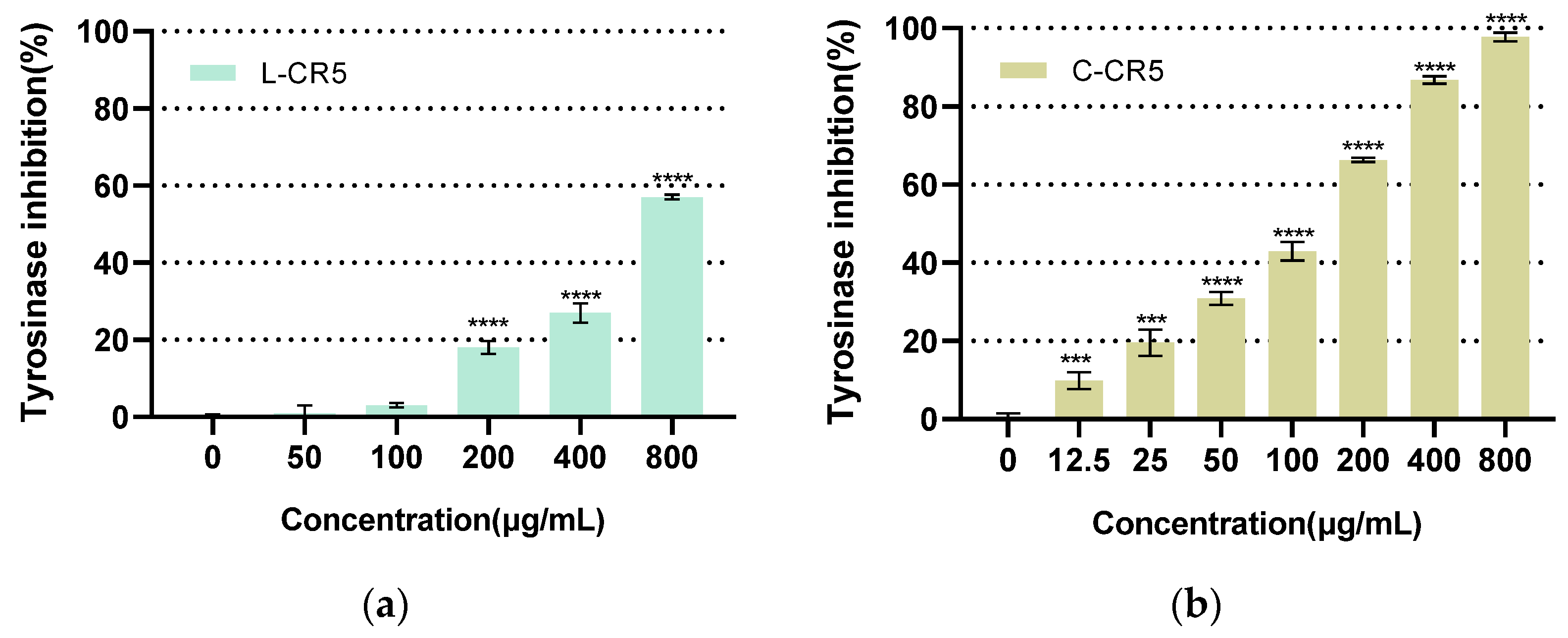

3.5. Comparison of Tyrosinase Inhibitory Activity of L-CR5 and C-CR5

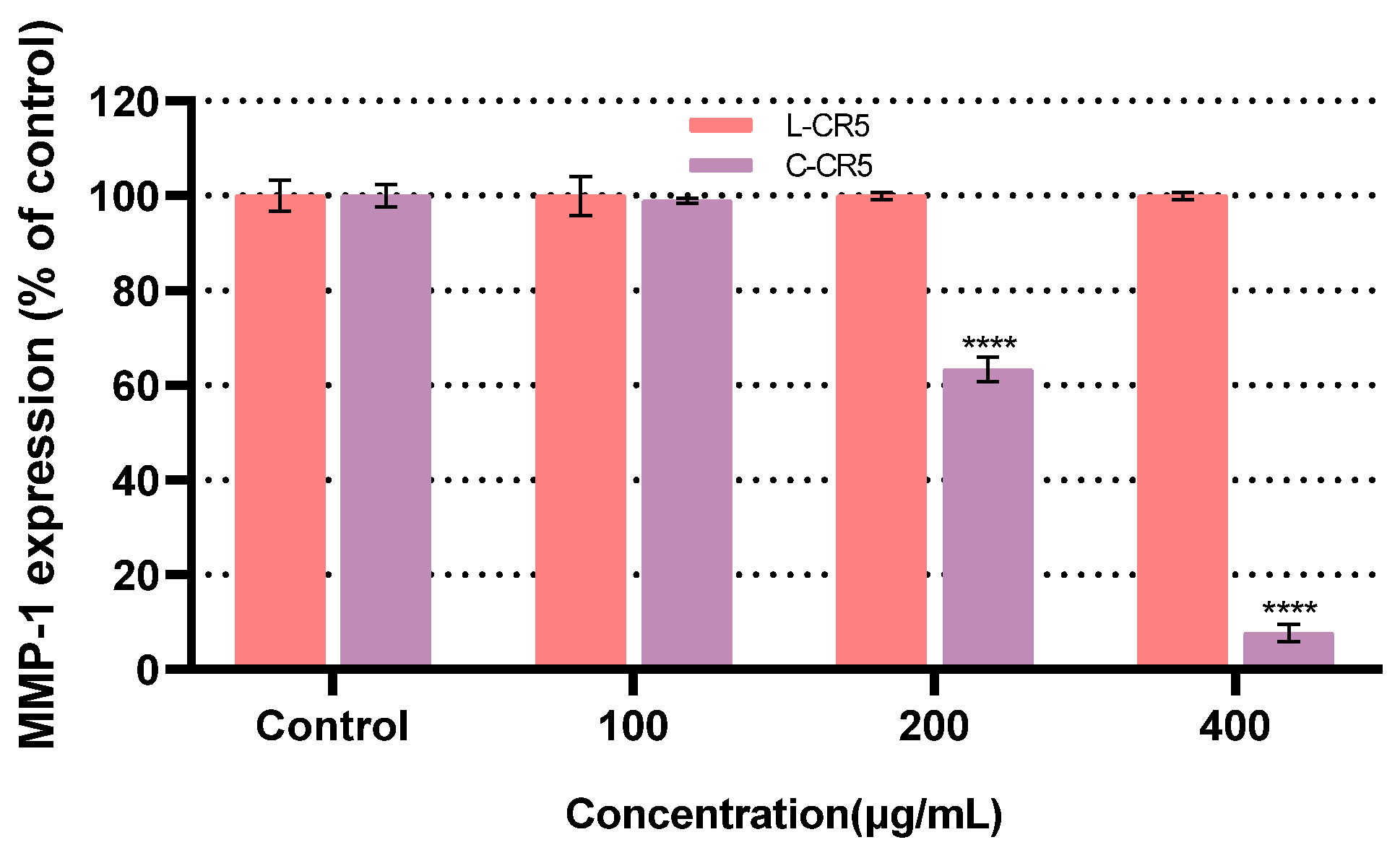

3.6. Comparison of MMP-1 Expression of L-CR5 and C-CR5

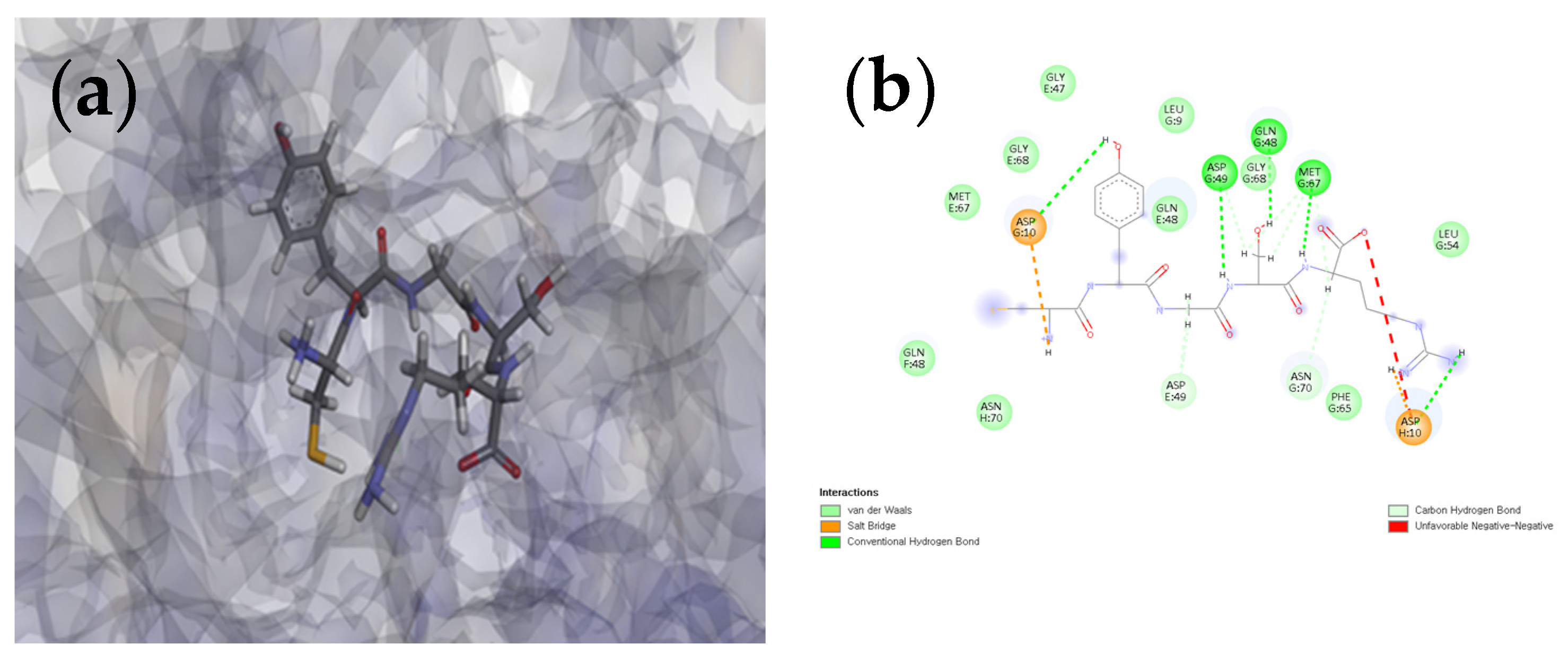

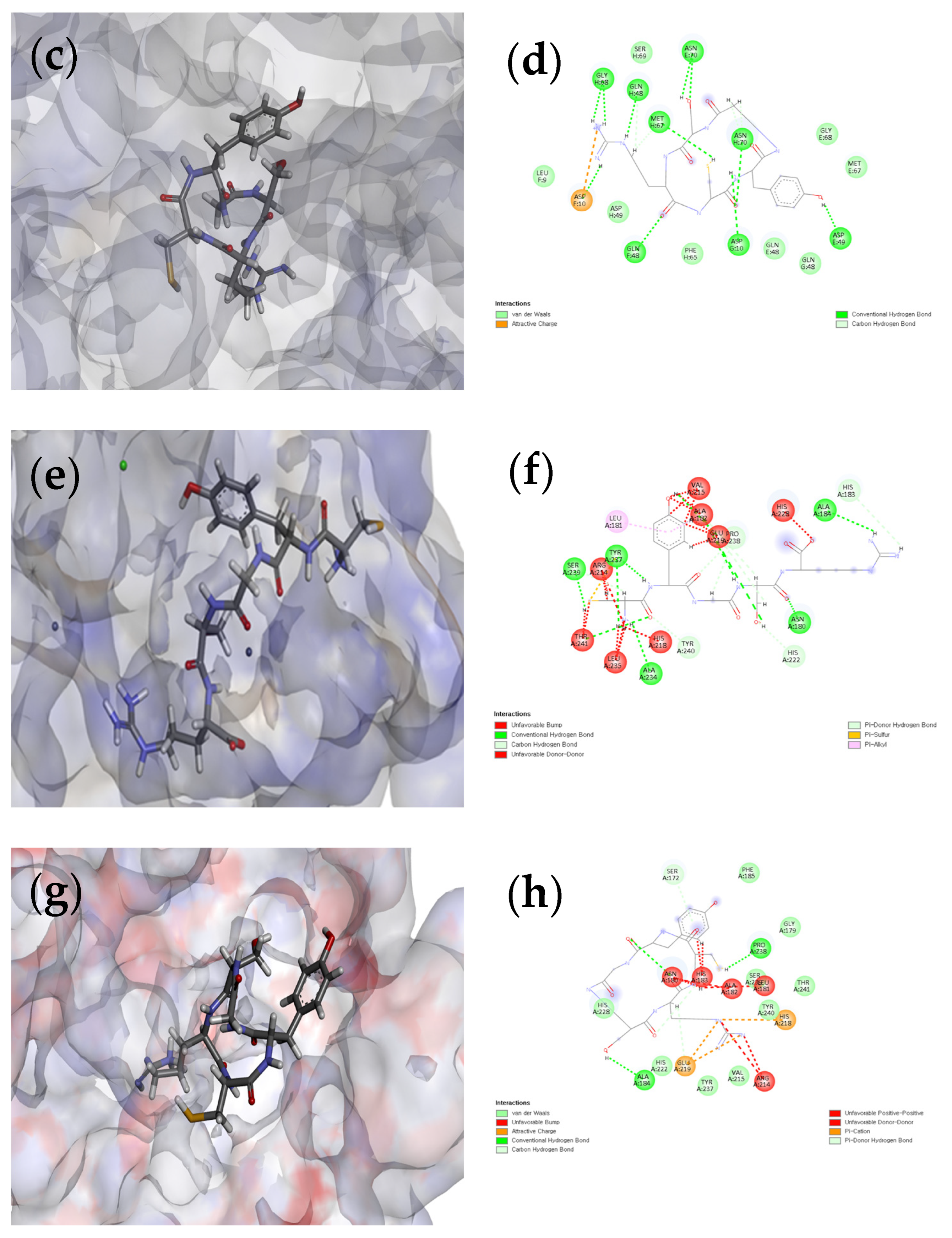

3.7. Docking of L-CR5 and C-CR5 Molecules with Target Proteins (Tyrosinase and MMP-1)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| C-CR5 | Cyclic-CYGSR |

| CR5 | Cys-Tyr-Gly-Ser-Arg;CYGSR |

| CTC | 2-Cholorotrityl chloride resin |

| DCM | dichloro methane |

| DIEA | N,N-diisopropylethylamine |

| DIC | N,N-diisoepropylcarbodiimide |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s medium |

| DMF | N,N-Dimethylformamide |

| DPBS | Dulbecco’s Phosphate Buffered Saline |

| DPPH | 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| EDC | N-ethyl-N′-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide |

| FBS | fetal bovine serum |

| HOBt | N-hyroxybenzotriazole |

| HPLC | High Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| IMDM | Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s medium |

| IPE | isopropyl ether |

| L-CR5 | Linear-CYGSR |

| MALDI-TOF | Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight |

| MMP-1 | Matrix Metalloproteinase-1 |

| MVD | Molegro Virtual Docker |

| PDA | Photodiode array |

| SAR | structure-activity relationship |

| SPPS | solid-phase peptide synthesis |

| TFA | trifluoroacetic acid |

| TIS | triisopropylsilane |

References

- Lamers, C. Overcoming the Shortcomings of Peptide-Based Therapeutics. Future Drug. Discov. 2022, 4, FDD75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baral, K.C.; Choi, K.Y. Barriers and Strategies for Oral Peptide and Protein Therapeutics Delivery: Update on Clinical Advances. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, B.J.; King, A.T.; Katsifis, A.; Matesic, L.; Jamie, J.F. Methods to Enhance the Metabolic Stability of Peptide-Based PET Radiopharmaceuticals. Molecules 2020, 25, 2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, L.; Genio, V.D.; Albericio, F.; Williams, D.R. Advances in Peptidomimetics for Next-Generation Therapeutics: Strategies, Modifications, and Applications. Chem. Rev. 2025, 125, 7099–7166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, H.C.; Luk, L.Y.P.; Tsai, Y.-H. Approaches for Peptide and Protein Cyclisation. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2021, 19, 3983–4001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamley, I.W. Small Bioactive Peptides for Biomaterials Design and Therapeutics. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 14015–14041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, A.; Vázquez, A. Bioactive Peptides: A Review. Food Qual. Saf. 2017, 1, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Walraven, N.; FitzGerald, R.J.; Danneel, H.-J.; Amigo-Benavent, M. Bioactive Peptides in Cosmetic Formulations: Review of Current in Vitro and Ex Vivo Evidence. Peptides 2025, 193, 171440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Nie, T.; Zhang, L.; Liu, X.; Deng, H. Peptides in Cosmetics: From Pharmaceutical Breakthroughs to Skincare Innovations. Cosmetics 2025, 12, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiga, E.; Ferreira, L.; Correia, M.; Pires, P.C.; Hameed, H.; Araújo, A.R.T.S.; Cefali, L.C.; Mazzola, P.G.; Hamishehkar, H.; Veiga, F.; et al. Anti-Aging Peptides for Advanced Skincare: Focus on Nanodelivery Systems. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2023, 89, 105087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintea, A.; Manea, A.; Pintea, C.; Vlad, R.-A.; Bîrsan, M.; Antonoaea, P.; Rédai, E.M.; Ciurba, A. Peptides: Emerging Candidates for the Prevention and Treatment of Skin Senescence: A Review. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Nielsen, A.L.; Heinis, C. Cyclic Peptides for Drug Development. Angew. Chem. 2024, 136, e202308251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.-S.; Joo, S.H. Recent Trends in Cyclic Peptides as Therapeutic Agents and Biochemical Tools. Biomol. Ther. 2020, 28, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, Q.N.; Young, R.; Sudhakar, H.K.; Gao, T.; Huang, T.; Tan, Y.S.; Lau, Y.H. Cyclisation Strategies for Stabilising Peptides with Irregular Conformations. RSC Med. Chem. 2021, 12, 887–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.-H.; Kim, B.-M. In Vitro and In Silico Evaluation of a Novel Multifunctional Cyclic Peptide with Antioxidant, Tyrosinase-Inhibitory, and Extracellular Matrix-Modulating Activities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roxin, Á.; Zheng, G. Flexible Or Fixed: A Comparative Review Of Linear And Cyclic Cancer-Targeting Peptides. Future Med. Chem. 2012, 4, 1601–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falanga, A.; Nigro, E.; De Biasi, M.; Daniele, A.; Morelli, G.; Galdiero, S.; Scudiero, O. Cyclic Peptides as Novel Therapeutic Microbicides: Engineering of Human Defensin Mimetics. Molecules 2017, 22, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hacker, D.E.; Abrigo, N.A.; Hoinka, J.; Richardson, S.L.; Przytycka, T.M.; Hartman, M.C.T. Direct, Competitive Comparison of Linear, Monocyclic, and Bicyclic Libraries Using mRNA Display. ACS Comb. Sci. 2020, 22, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Vlachos, E.N.; Bryant, P. Design of Linear and Cyclic Peptide Binders from Protein Sequence Information. Commun. Chem. 2025, 8, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.; Arumugam, S. Food-Derived Linear vs. Rationally Designed Cyclic Peptides as Potent TNF-Alpha Inhibitors: An Integrative Computational Study. Front. Bioinform. 2025, 5, 1716375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaofi, A.; On, N.; Kiptoo, P.; Williams, T.D.; Miller, D.W.; Siahaan, T.J. Comparison of Linear and Cyclic His-Ala-Val Peptides in Modulating the Blood-Brain Barrier Permeability: Impact on Delivery of Molecules to the Brain. J. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 105, 797–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.H.; Kim, J.; Lee, H.; Kim, S.Y.; Jang, H.-H.; Ryu, S.H.; Kim, B.J.; Lee, T.G. Laminin Peptide YIGSR Induces Collagen Synthesis in Hs27 Human Dermal Fibroblasts. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 428, 416–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.; Du, B.; Zhang, C.; Zaman, F.; Huang, Y. Isolation and Identification of an Antioxidant Collagen Peptide from Skipjack Tuna (Katsuwonus Pelamis) Bone. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 27032–27041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, K.; Jia, X.; Fu, C.; Yu, H.; Wang, Y. Antioxidant Peptides, the Guardian of Life from Oxidative Stress. Med. Res. Rev. 2024, 44, 275–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Fan, H.; Teng, X.; Sun, T.; Zhang, S.; Wang, N.; Zhang, X.; Liu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, D. Exploring Novel Antioxidant Cyclic Peptides in Corn Protein Hydrolysate: Preparation, Identification and Molecular Docking Analysis. Food Chem. 2025, 464, 141747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Sun, T.; Gao, H.; Liu, X.; Zhang, S.; Liu, T.; Wang, D.; Fan, H.; Zhang, Y. Bioinformatics-Assisted Discovery of Antioxidant Cyclic Peptides from Corn Gluten Meal. Foods 2025, 14, 1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Paz-Lugo, P.; Lupiáñez, J.A.; Meléndez-Hevia, E. High Glycine Concentration Increases Collagen Synthesis by Articular Chondrocytes in Vitro: Acute Glycine Deficiency Could Be an Important Cause of Osteoarthritis. Amino Acids 2018, 50, 1357–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Zhong, B.; Qin, X.; Xu, H.; Li, Z.; Li, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, W.; Lou, Z.; Fan, Y.; et al. An Epidermal Serine Sensing System for Skin Healthcare. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, T.; Kanazawa, S.; Ichibori, R.; Tanigawa, T.; Magome, T.; Shingaki, K.; Miyata, S.; Tohyama, M.; Hosokawa, K. L-Arginine Stimulates Fibroblast Proliferation through the GPRC6A-ERK1/2 and PI3K/Akt Pathway. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e92168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozovičar, K.; Bratkovič, T. Small and Simple, yet Sturdy: Conformationally Constrained Peptides with Remarkable Properties. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, S. Cyclic Peptide Drugs Approved in the Last Two Decades (2001–2021). RSC Chem. Biol. 2022, 3, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, S.; Maharani, R.; Maksum, I.; Siahaan, T. Peptide Design for Enhanced Anti-Melanogenesis: Optimizing Molecular Weight, Polarity, and Cyclization. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2025, 19, 645–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Tao, K.; Huang, H.; Jia, J.; Khan, S.N.; Cui, J. Discovery of a Novel Cyclopeptide as Tyrosinase Inhibitor for Skin Lightening. Ski. Res. Technol. 2025, 31, e70207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndinguri, M.; Bhowmick, M.; Tokmina-Roszyk, D.; Robichaud, T.; Fields, G. Peptide-Based Selective Inhibitors of Matrix Metalloproteinase-Mediated Activities. Molecules 2012, 17, 14230–14248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.; Shawon, A.R.M.; Aeyas, A.; Uddin, M.A. Cyclic Peptides as an Inhibitor of Metastasis in Breast Cancer Targeting MMP-1: Computational Approach. Inform. Med. Unlocked 2022, 35, 101128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, R.; Christensen, M.H. MolDock: A New Technique for High-Accuracy Molecular Docking. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 3315–3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martian, P.C.; Tertis, M.; Leonte, D.; Hadade, N.; Cristea, C.; Crisan, O. Cyclic Peptides: A Powerful Instrument for Advancing Biomedical Nanotechnologies and Drug Development. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2025, 252, 116488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseinzadeh, P.; Watson, P.R.; Craven, T.W.; Li, X.; Rettie, S.; Pardo-Avila, F.; Bera, A.K.; Mulligan, V.K.; Lu, P.; Ford, A.S.; et al. Anchor Extension: A Structure-Guided Approach to Design Cyclic Peptides Targeting Enzyme Active Sites. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Wang, N.; Zhang, W.; Cheng, X.; Yan, Z.; Shao, G.; Wang, X.; Wang, R.; Fu, C. Therapeutic Peptides: Current Applications and Future Directions. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schurink, M.; Van Berkel, W.J.H.; Wichers, H.J.; Boeriu, C.G. Novel Peptides with Tyrosinase Inhibitory Activity. Peptides 2007, 28, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jwad, R.; Weissberger, D.; Hunter, L. Strategies for Fine-Tuning the Conformations of Cyclic Peptides. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 9743–9789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scharbert, L.; Strodel, B. Innovative Strategies for Modeling Peptide–Protein Interactions and Rational Peptide Drug Design. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2025, 93, 103083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yang, L.; Cao, S.; Gao, Z.; Yang, B.; Zhang, G.; Zhu, R.; Wu, D. CyclicPepedia: A Knowledge Base of Natural and Synthetic Cyclic Peptides. Brief. Bioinform. 2024, 25, bbae190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathias, G.E.; Iwuala, L.C.; Ikenyirimba, O.J.; Obannaya, S.N.; Ekep-Obasi, M.R.; Ebenso, E.E. Quantum and Molecular Modelling of Abrocitinib as a Potential Disruptor of Cell Polarity in Colorectal Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 39651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Raza, A.; Singh, S.K.; Kaur, J.; Wadhwa, P. Computational Evaluation of ADMET Properties and Molecular Docking Studies on Cryptolepine Analogs as Inhibitors of HIV Integrase. Curr. Signal Transduct. Ther. 2025, 20, e15743624305290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Z.; Song, Q.; Xu, J.; Yu, S.; Ma, H. The Cyclic Antimicrobial Peptide C-LR18 Has Enhanced Antibacterial Activity, Improved Stability, and a Longer Half-Life Compared to the Original Peptide. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaskani, C.; Poulos, C.P.; Zhang, J.; Tobe, S.S. The Synthesis and Biological Activity of Linear and Cyclic Analogs of the Two Diuretic Peptides of Diploptera Punctata. Peptides 2009, 30, 603–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Peptide | Target Protein | MolDock Score (kcal/mol) | Rerank Score | H-Bond (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L-CR5 | Tyrosinase | −75.3578 | −65.8698 | −10.5355 |

| C-CR5 | Tyrosinase | −110.023 | −72.9746 | −14.8095 |

| L-CR5 | MMP-1 | −60.0822 | 21.1785 | −3.24147 |

| C-CR5 | MMP-1 | −99.6438 | 27.7123 | −9.19535 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kim, G.-H.; Bang, J.-E.; Kim, B.-M. Comparison of In Vitro Multiple Physiological Activities of Cys–Tyr–Gly–Ser–Arg (CYGSR) Linear and Cyclic Peptides and Analysis Based on Molecular Docking. Biomolecules 2026, 16, 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010126

Kim G-H, Bang J-E, Kim B-M. Comparison of In Vitro Multiple Physiological Activities of Cys–Tyr–Gly–Ser–Arg (CYGSR) Linear and Cyclic Peptides and Analysis Based on Molecular Docking. Biomolecules. 2026; 16(1):126. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010126

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Ga-Hyun, Jeong-Eun Bang, and Bo-Mi Kim. 2026. "Comparison of In Vitro Multiple Physiological Activities of Cys–Tyr–Gly–Ser–Arg (CYGSR) Linear and Cyclic Peptides and Analysis Based on Molecular Docking" Biomolecules 16, no. 1: 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010126

APA StyleKim, G.-H., Bang, J.-E., & Kim, B.-M. (2026). Comparison of In Vitro Multiple Physiological Activities of Cys–Tyr–Gly–Ser–Arg (CYGSR) Linear and Cyclic Peptides and Analysis Based on Molecular Docking. Biomolecules, 16(1), 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010126