Machine Learning-Based Virtual Screening for the Identification of Novel CDK-9 Inhibitors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Processing

2.2. Molecular Representations

2.3. Machine Learning Algorithms

2.4. Model Evaluation and Structural Similarity Metrics

2.5. Model Development and Assessment

2.6. Virtual Screening

2.7. Clustering

2.8. Experimental Validation

2.8.1. Enzymatic Assays

2.8.2. Immunofluorescence Analysis

2.8.3. Cell Viability Assays

2.9. Molecular Docking Studies

2.10. Molecular Dynamics Simulation

3. Results

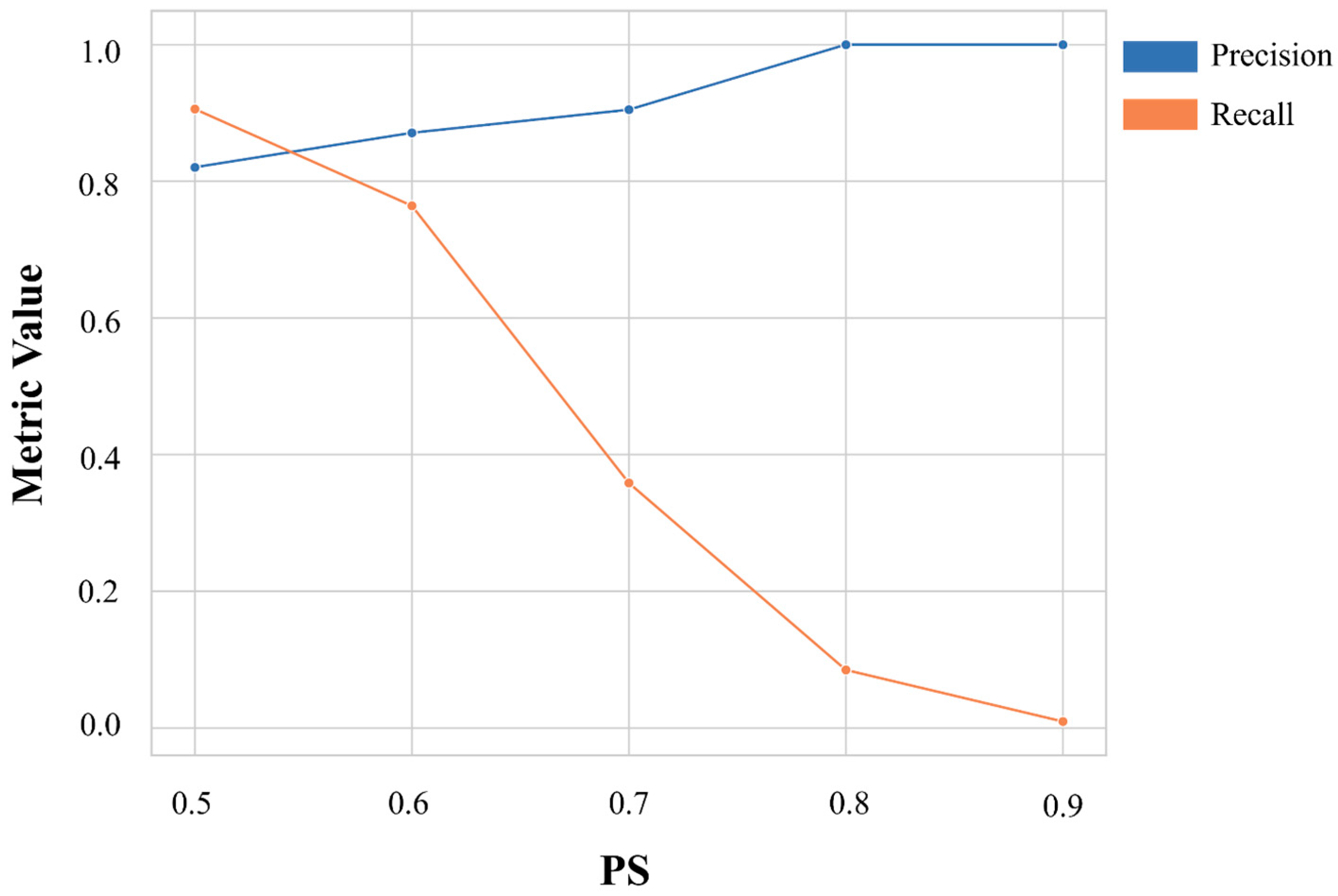

3.1. Machine Learning Model Generation, Optimization, and Assessment

3.2. Virtual Screening

3.3. Enzymatic Assays

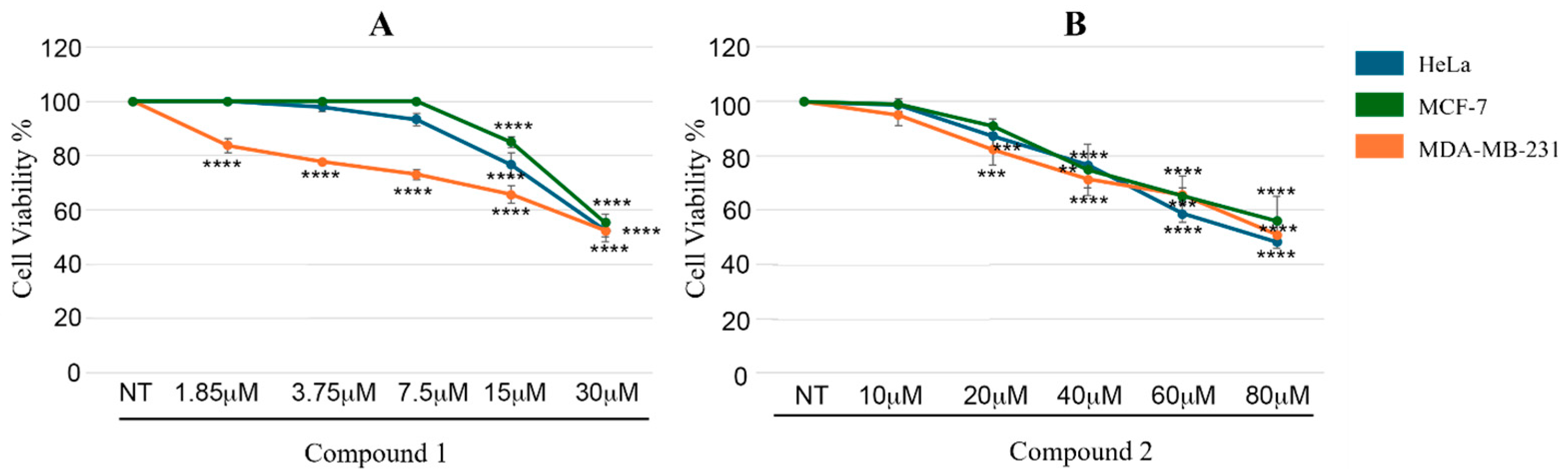

3.4. Antiproliferative Assays

3.5. Molecular Modeling Studies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mandal, R.; Becker, S.; Strebhardt, K. Targeting CDK9 for Anti-Cancer Therapeutics. Cancers 2021, 13, 2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfano, L.; Iannuzzi, C.A.; Barone, D.; Forte, I.M.; Ragosta, M.C.; Cuomo, M.; Mazzarotti, G.; Dell’Aquila, M.; Altieri, A.; Caporaso, A.; et al. CDK9-55 Guides the Anaphase-Promoting Complex/Cyclosome (APC/C) in Choosing the DNA Repair Pathway Choice. Oncogene 2024, 43, 1263–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacon, C.W.; D’Orso, I. CDK9: A Signaling Hub for Transcriptional Control. Transcription 2019, 10, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egloff, S. CDK9 Keeps RNA Polymerase II on Track. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2021, 78, 5543–5567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anshabo, A.T.; Milne, R.; Wang, S.; Albrecht, H. CDK9: A Comprehensive Review of Its Biology, and Its Role as a Potential Target for Anti-Cancer Agents. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 678559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, C.; Wei, N.; Li, T.; Ahmed Bhat, M.; Mohammadi, M.; Kuang, C. CDK9 Inhibitors for the Treatment of Solid Tumors. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2024, 229, 116470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kryštof, V.; Chamrád, I.; Jorda, R.; Kohoutek, J. Pharmacological Targeting of CDK9 in Cardiac Hypertrophy. Med. Res. Rev. 2010, 30, 646–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellvard, A.; Zeitlmann, L.; Heiser, U.; Kehlen, A.; Niestroj, A.; Demuth, H.U.; Koziel, J.; Delaleu, N.; Potempa, J.; Mydel, P. Inhibition of CDK9 as a Therapeutic Strategy for Inflammatory Arthritis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toure, M.A.; Koehler, A.N. Addressing Transcriptional Dysregulation in Cancer through CDK9 Inhibition. Biochemistry 2023, 62, 1114–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galati, S.; Di Stefano, M.; Bertini, S.; Granchi, C.; Giordano, A.; Gado, F.; Macchia, M.; Tuccinardi, T.; Poli, G. Identification of New GSK3β Inhibitors through a Consensus Machine Learning-Based Virtual Screening. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stefano, M.; Galati, S.; Ortore, G.; Caligiuri, I.; Rizzolio, F.; Ceni, C.; Bertini, S.; Bononi, G.; Granchi, C.; Macchia, M.; et al. Machine Learning-Based Virtual Screening for the Identification of Cdk5 Inhibitors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stefano, M.; Piazza, L.; Poles, C.; Galati, S.; Granchi, C.; Giordano, A.; Campisi, L.; Macchia, M.; Poli, G.; Tuccinardi, T. KinasePred: A Computational Tool for Small-Molecule Kinase Target Prediction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez, D.; Gaulton, A.; Bento, A.P.; Chambers, J.; De Veij, M.; Félix, E.; Magariños, M.P.; Mosquera, J.F.; Mutowo, P.; Nowotka, M.; et al. ChEMBL: Towards Direct Deposition of Bioassay Data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D930–D940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galati, S.; Di Stefano, M.; Macchia, M.; Poli, G.; Tuccinardi, T. MolBook UNIPI─Create, Manage, Analyze, and Share Your Chemical Data for Free. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2023, 63, 3977–3982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galati, S.; Di Stefano, M.; Piazza, L.; Poles, C.; Macchia, M.; Tuccinardi, T. MolBook Pro 2025. Available online: https://molbookpro.farm.unipi.it/ (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Irwin, J.J.; Tang, K.G.; Young, J.; Dandarchuluun, C.; Wong, B.R.; Khurelbaatar, M.; Moroz, Y.S.; Mayfield, J.; Sayle, R.A. ZINC20-A Free Ultralarge-Scale Chemical Database for Ligand Discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2020, 60, 6065–6073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrum, G. RDKit: Open-Source Cheminformatics. Available online: https://www.rdkit.org (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Müller, A.; Nothman, J.; Louppe, G.; et al. Scikit-Learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Ralaivola, L.; Swamidass, S.J.; Saigo, H.; Baldi, P. Graph Kernels for Chemical Informatics. Neural Netw. 2005, 18, 1093–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthews, B.W. Comparison of the Predicted and Observed Secondary Structure of T4 Phage Lysozyme. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Protein Struct. 1975, 405, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajusz, D.; Rácz, A.; Héberger, K. Why is Tanimoto Index an Appropriate Choice for Fingerprint-Based Similarity Calculations? J. Cheminform. 2015, 7, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demšar, J.; Erjavec, A.; Hočevar, T.; Milutinovič, M.; Možina, M.; Toplak, M.; Umek, L.; Zbontar, J.; Zupan, B. Orange: Data Mining Toolbox in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2013, 14, 2349–2353. [Google Scholar]

- Minzel, W.; Venkatachalam, A.; Fink, A.; Hung, E.; Brachya, G.; Burstain, I.; Shaham, M.; Rivlin, A.; Omer, I.; Zinger, A.; et al. Small Molecules Co-Targeting CKIα and the Transcriptional Kinases CDK7/9 Control AML in Preclinical Models. Cell 2018, 175, 171–185.e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Ascenzio, M.; Secci, D.; Carradori, S.; Zara, S.; Guglielmi, P.; Cirilli, R.; Pierini, M.; Poli, G.; Tuccinardi, T.; Angeli, A.; et al. 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition, HPLC Enantioseparation, and Docking Studies of Saccharin/Isoxazole and Saccharin/Isoxazoline Derivatives as Selective Carbonic Anhydrase IX and XII Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 2470–2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case, D.A.; Cheatham, T.E.; Darden, T.; Gohlke, H.; Luo, R.; Merz, K.M.; Onufriev, A.; Simmerling, C.; Wang, B.; Woods, R.J. The Amber Biomolecular Simulation Programs. J. Comput. Chem. 2005, 26, 1668–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mota, A.d.L.; Evangelista, A.F.; Macedo, T.; Oliveira, R.; Scapulatempo-Neto, C.; Vieira, R.A.d.C.; Marques, M.M.C. Molecular Characterization of Breast Cancer Cell Lines by Clinical Immunohistochemical Markers. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 13, 4708–4712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamle, M.; Pandhi, S.; Mishra, S.; Barua, S.; Kurian, A.; Mahato, D.K.; Rasane, P.; Büsselberg, D.; Kumar, P.; Calina, D.; et al. Camptothecin and Its Derivatives: Advancements, Mechanisms and Clinical Potential in Cancer Therapy. Med. Oncol. 2024, 41, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Singh, K.; Almasan, A. Histone H2AX Phosphorylation: A Marker for DNA Damage. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012, 920, 613–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartori, A.A.; Lukas, C.; Coates, J.; Mistrik, M.; Fu, S.; Bartek, J.; Baer, R.; Lukas, J.; Jackson, S.P. Human CtIP Promotes DNA End Resection. Nature 2007, 450, 509–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, T.; Cao, S.; Su, P.C.; Patel, R.; Shah, D.; Chokshi, H.B.; Szukala, R.; Johnson, M.E.; Hevener, K.E. Hit Identification and Optimization in Virtual Screening: Practical Recommendations Based on a Critical Literature Analysis. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 6560–6572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Shen, Z.; Chen, R.; Yao, C.; Pan, Z.; Wu, D.; Dong, X. Identification of Potent CDK9 Inhibitors with Novel Skeletons via Virtual Screening, Biological Evaluation, and Molecular Dynamics Simulation. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2024, 15, 1654–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; He, H.; Zhao, L.; Chen, K.-B.; Li, S.; Chen, C.Y.-C. Adaptive Boost Approach for Possible Leads of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2022, 231, 104690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Han, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, C.; Li, J.; Li, Z. Identification of Novel CDK 9 Inhibitors Based on Virtual Screening, Molecular Dynamics Simulation, and Biological Evaluation. Life Sci. 2020, 258, 118228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asamitsu, K.; Hirokawa, T.; Okamoto, T. Drug Design for Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 9 (CDK9) Inhibitors in Silico. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2025, 42, 101988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Kumar, V.; Jung, T.S.; Lee, J.S.; Lee, K.W.; Hong, J.C. Uncovering Potential CDK9 Inhibitors from Natural Compound Databases through Docking-Based Virtual Screening and MD Simulations. J. Mol. Model. 2024, 30, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Kutchukian, P.; Nguyen, N.D.; AlQuraishi, M.; Sorger, P.K. A Hybrid Structure-Based Machine Learning Approach for Predicting Kinase Inhibition by Small Molecules. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2023, 63, 5457–5472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piazza, L.; Di Stefano, M.; Poles, C.; Bononi, G.; Poli, G.; Renzi, G.; Galati, S.; Giordano, A.; Macchia, M.; Carta, F.; et al. A Machine Learning Platform for Isoform-Specific Identification and Profiling of Human Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitors. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Huang, J.; Chen, R.; Cai, H.; Chen, Y.; He, S.; Xu, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L. Ligand- and Structure-Based Identification of Novel CDK9 Inhibitors for the Potential Treatment of Leukemia. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2022, 72, 116994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Lead-Oriented (LO) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Active | Inactive | Total | |

| Training | 1375 | 1375 | 2750 |

| Test | 279 | 279 | 558 |

| Potency-Oriented (PO) | |||

| Active | Inactive | Total | |

| Training | 447 | 447 | 894 |

| Test | 106 | 106 | 212 |

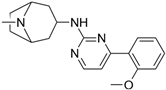

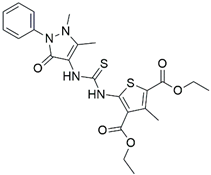

| Cpds. | Structure | Experimental IC50 (nM) |

|---|---|---|

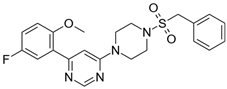

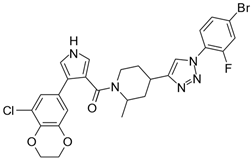

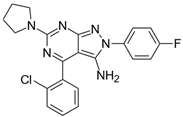

| 1 |  | 3510 |

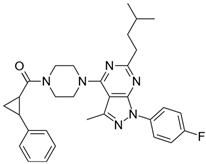

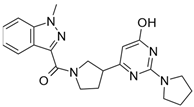

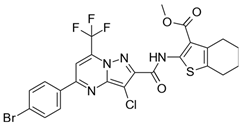

| 2 |  | 16,800 |

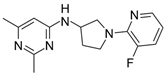

| 3 |  | 28,600 |

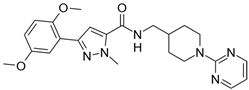

| 4 |  | 67,200 |

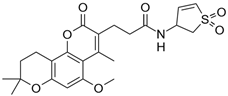

| 5 |  | 107,000 |

| 6 |  | 133,000 |

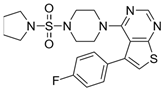

| 7 |  | 250,000 |

| 8 |  | 250,000 |

| 9 |  | 250,000 |

| 10 |  | 250,000 |

| 11 |  | 250,000 |

| 12 |  | 250,000 |

| 13 |  | 250,000 |

| 14 |  | 250,000 |

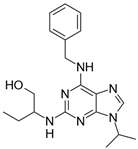

| Roscovitine |  | 476 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Piazza, L.; Poles, C.; Bononi, G.; Granchi, C.; Di Stefano, M.; Poli, G.; Giordano, A.; Medugno, A.; Napolitano, G.M.; Tuccinardi, T.; et al. Machine Learning-Based Virtual Screening for the Identification of Novel CDK-9 Inhibitors. Biomolecules 2026, 16, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010012

Piazza L, Poles C, Bononi G, Granchi C, Di Stefano M, Poli G, Giordano A, Medugno A, Napolitano GM, Tuccinardi T, et al. Machine Learning-Based Virtual Screening for the Identification of Novel CDK-9 Inhibitors. Biomolecules. 2026; 16(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010012

Chicago/Turabian StylePiazza, Lisa, Clarissa Poles, Giulia Bononi, Carlotta Granchi, Miriana Di Stefano, Giulio Poli, Antonio Giordano, Annamaria Medugno, Giuseppe Maria Napolitano, Tiziano Tuccinardi, and et al. 2026. "Machine Learning-Based Virtual Screening for the Identification of Novel CDK-9 Inhibitors" Biomolecules 16, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010012

APA StylePiazza, L., Poles, C., Bononi, G., Granchi, C., Di Stefano, M., Poli, G., Giordano, A., Medugno, A., Napolitano, G. M., Tuccinardi, T., & Alfano, L. (2026). Machine Learning-Based Virtual Screening for the Identification of Novel CDK-9 Inhibitors. Biomolecules, 16(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010012