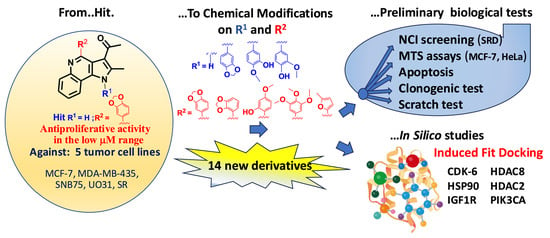

Tuning Scaffold Properties of New 1,4-Substituted Pyrrolo[3,2-c]quinoline Derivatives Endowed with Anticancer Potential, New Biological and In Silico Insights

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

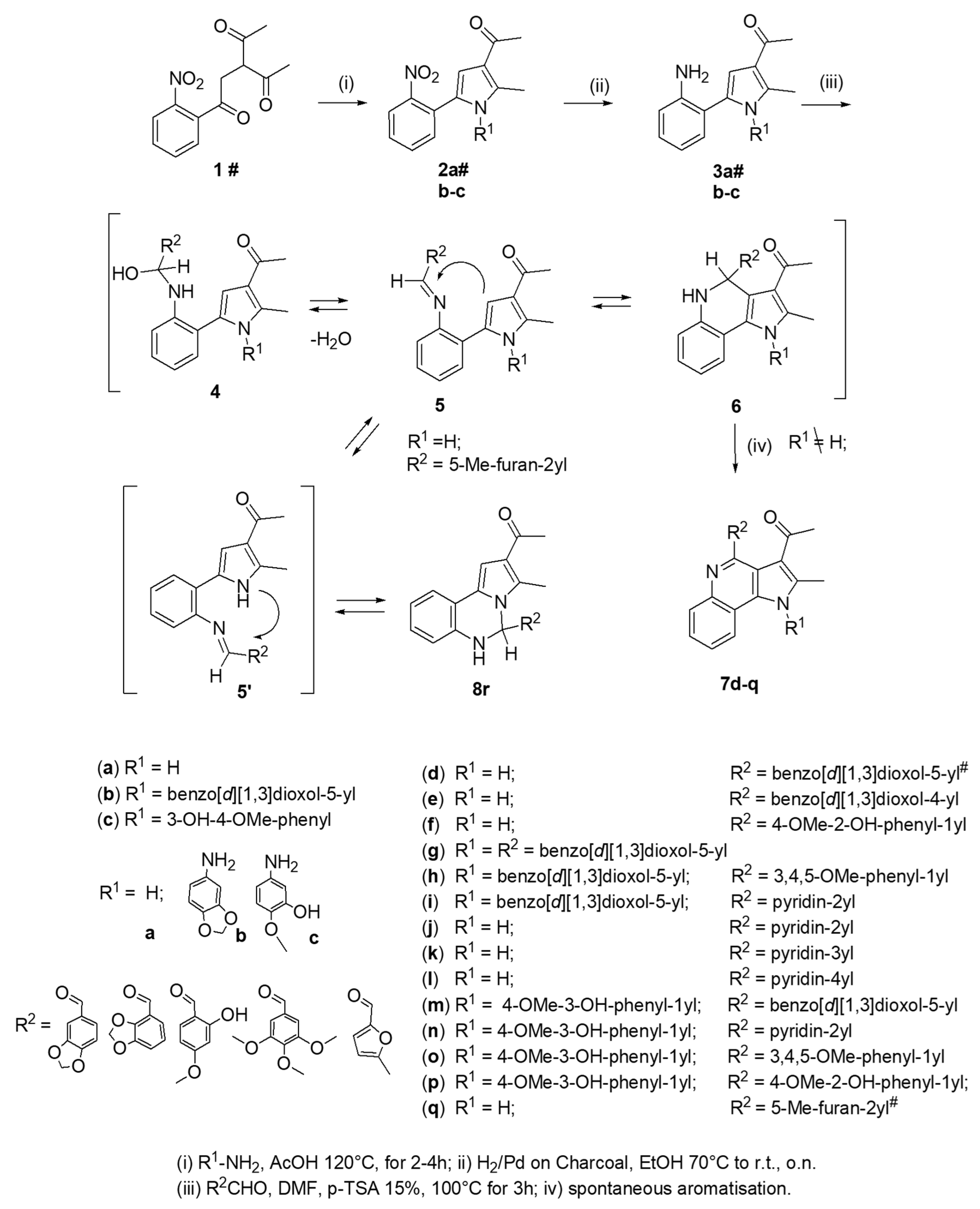

2.1. Chemistry: Experimental Procedures for the Synthesis and Characterization of PQ Compounds

2.1.1. General Procedure for the Preparation of 3-Acetyl-2-methyl-1-R1-5-(2-nitro-phenyl)-pyrrole 2a–c

2.1.2. General Procedure for the Preparation of 3-Acetyl-2-methyl-1-R1-5-(2-aminophenyl)-pyrrole 3a–c

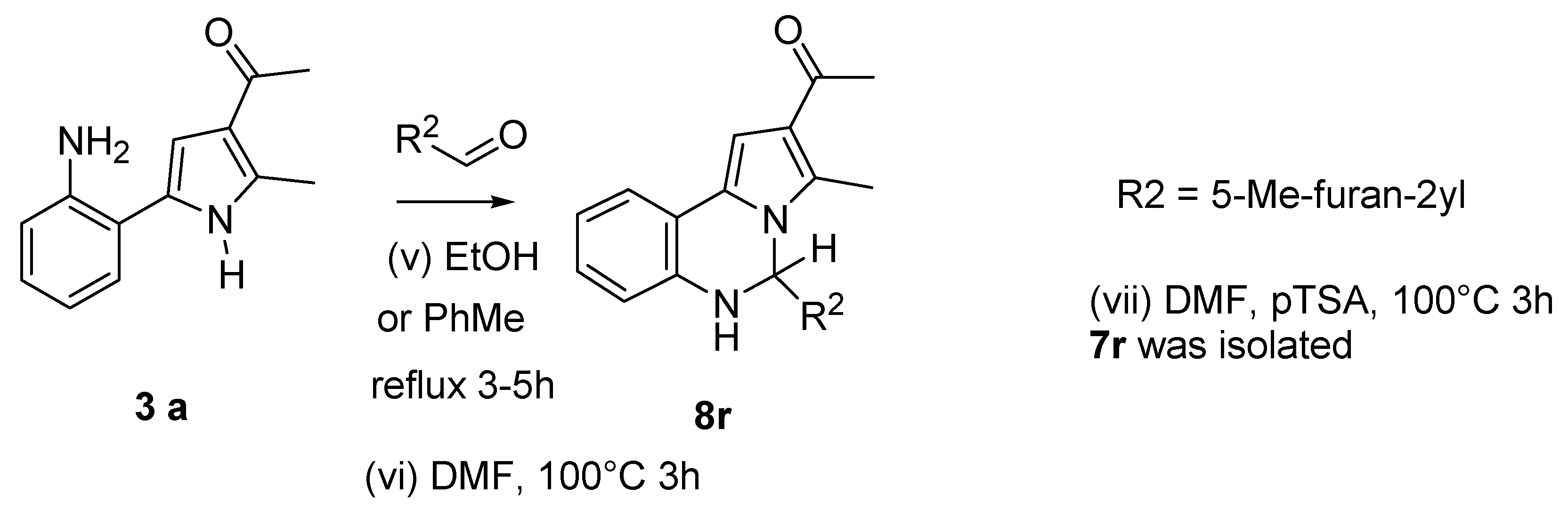

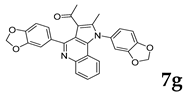

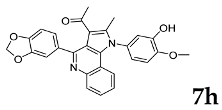

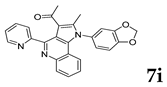

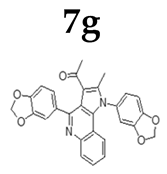

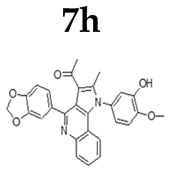

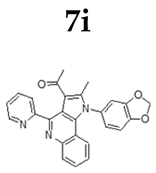

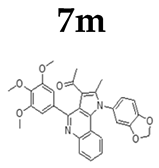

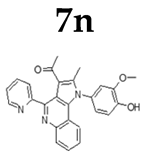

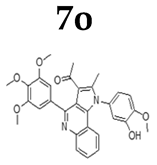

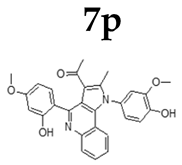

2.1.3. General Procedure for the Preparation of PQs (7d–q)

2.2. Biology

2.2.1. Cell Cultures

2.2.2. Cell Treatments

2.2.3. Clonogenic Assay

2.2.4. Wound Healing Test

2.2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.2.6. MTS Assays

2.3. Computational Studies

2.3.1. Ligand Preparation

2.3.2. Protein Preparation

2.3.3. Docking Validation

3. Results

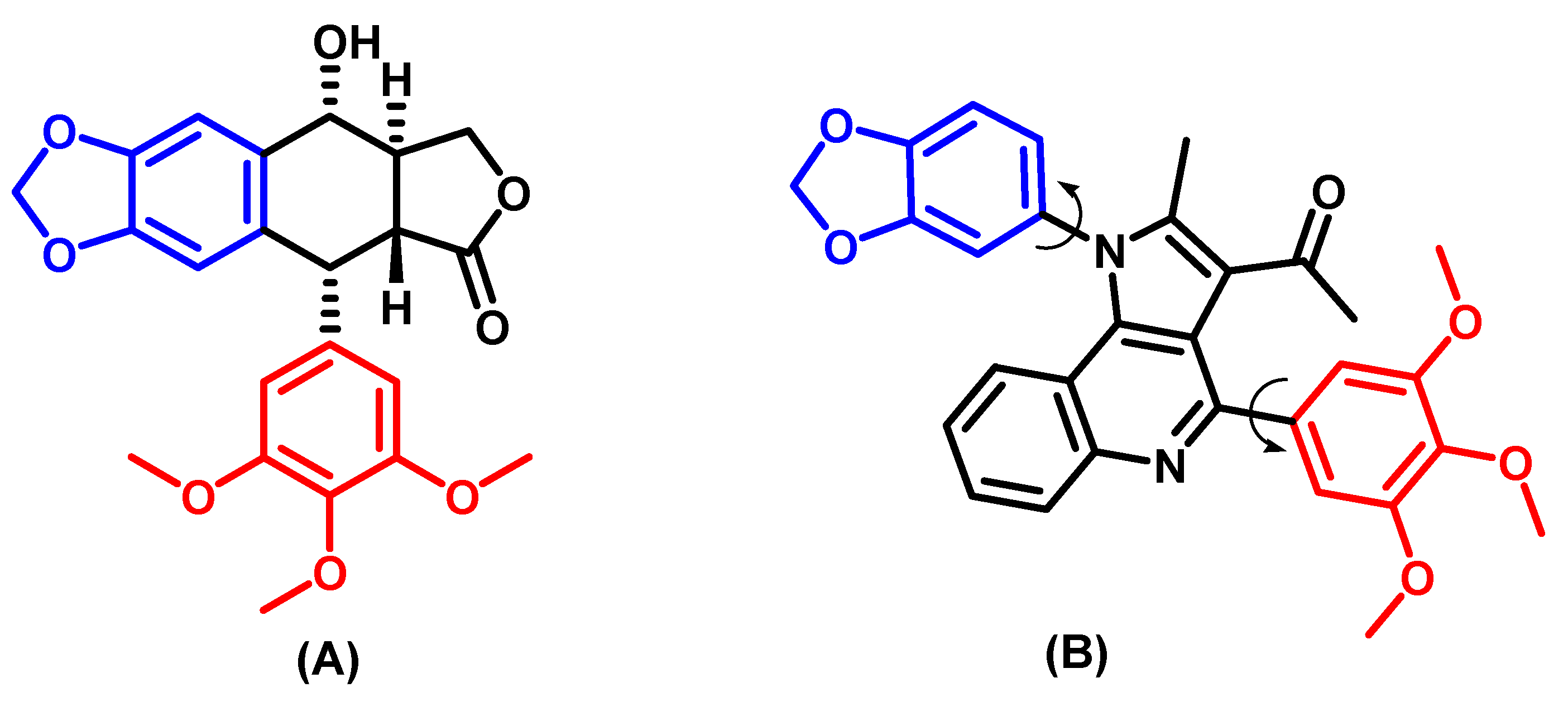

3.1. Chemistry

3.2. Biological Studies

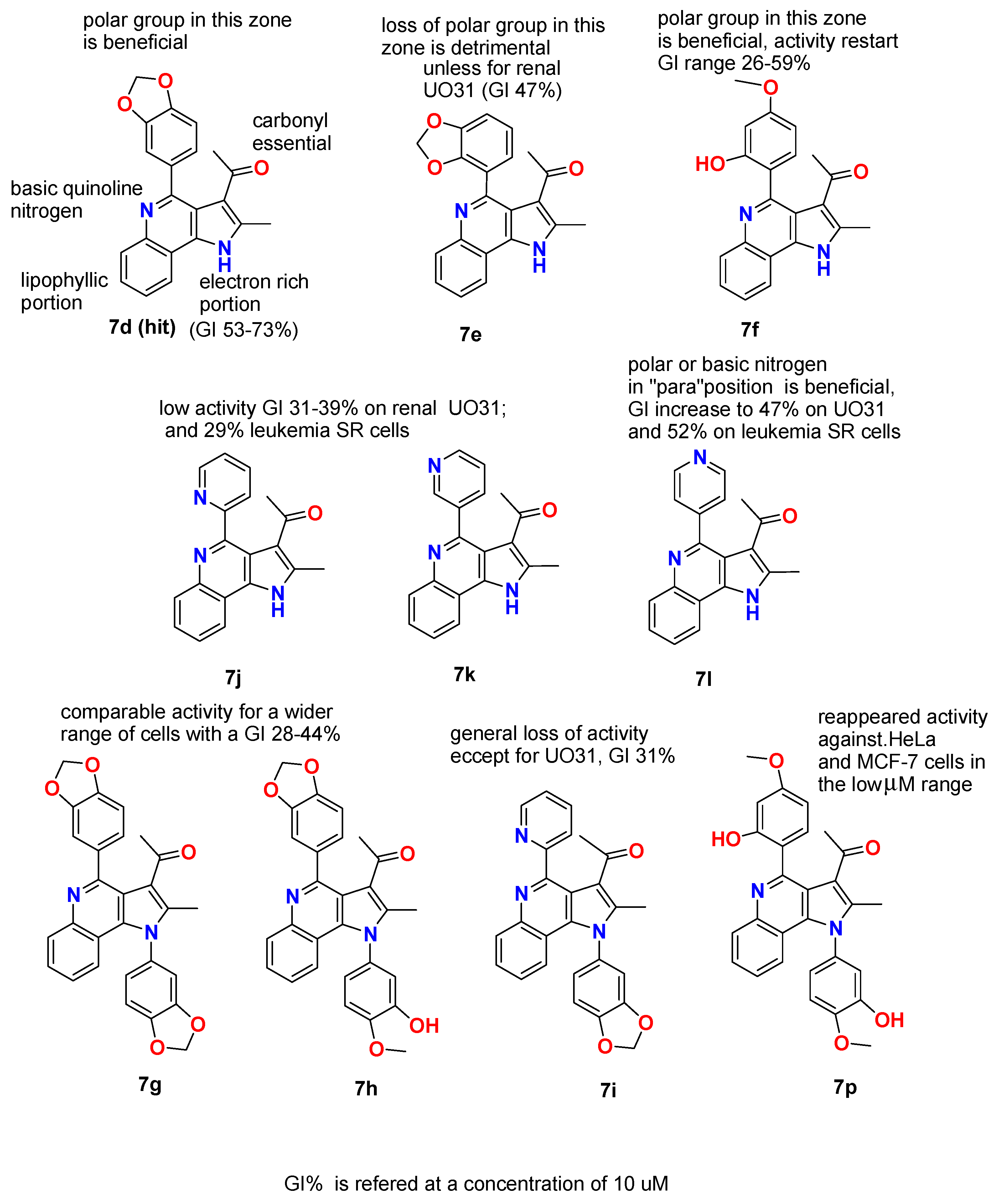

3.2.1. NCI Antiproliferative Assays

3.2.2. MTS Antiproliferative Assays

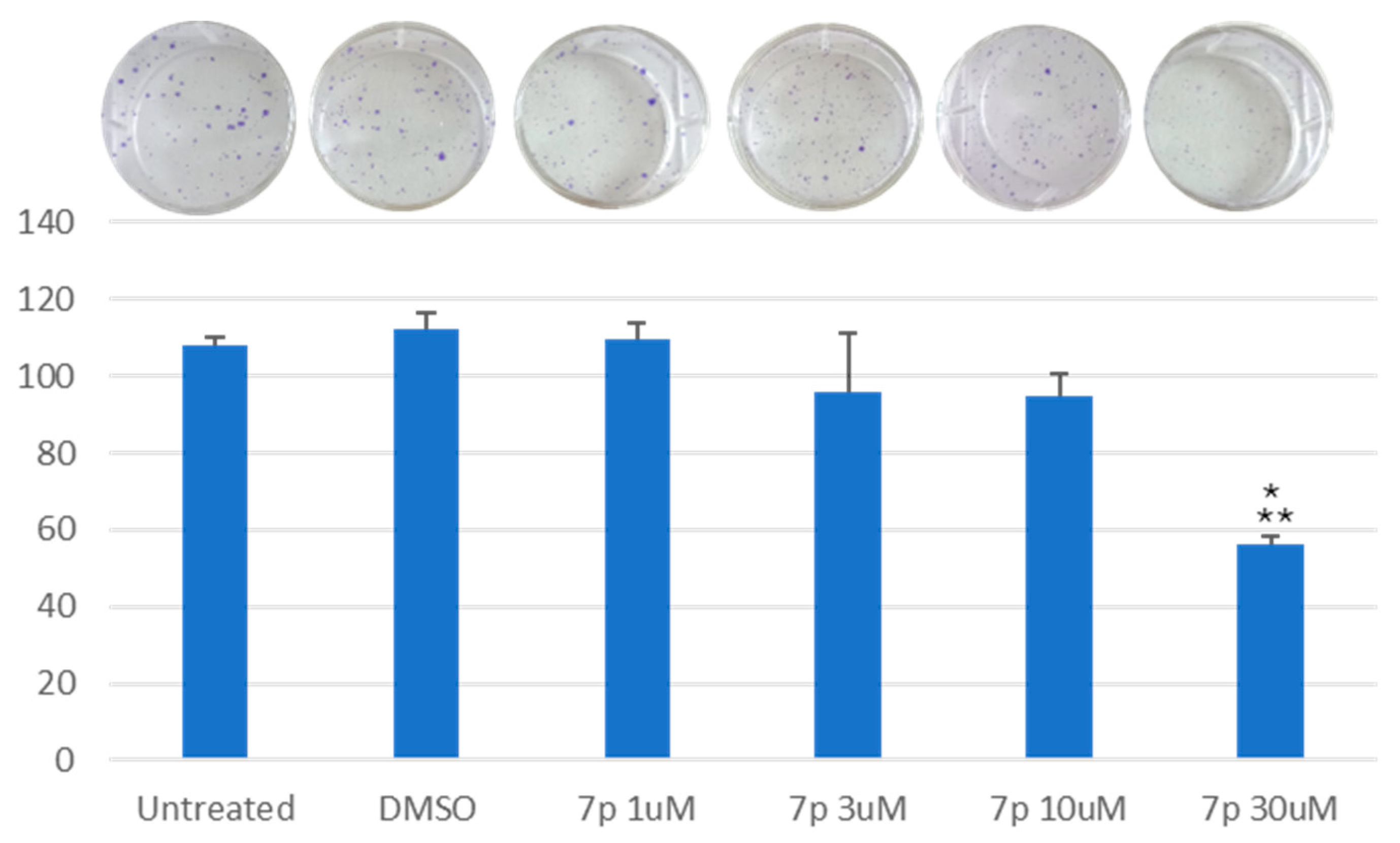

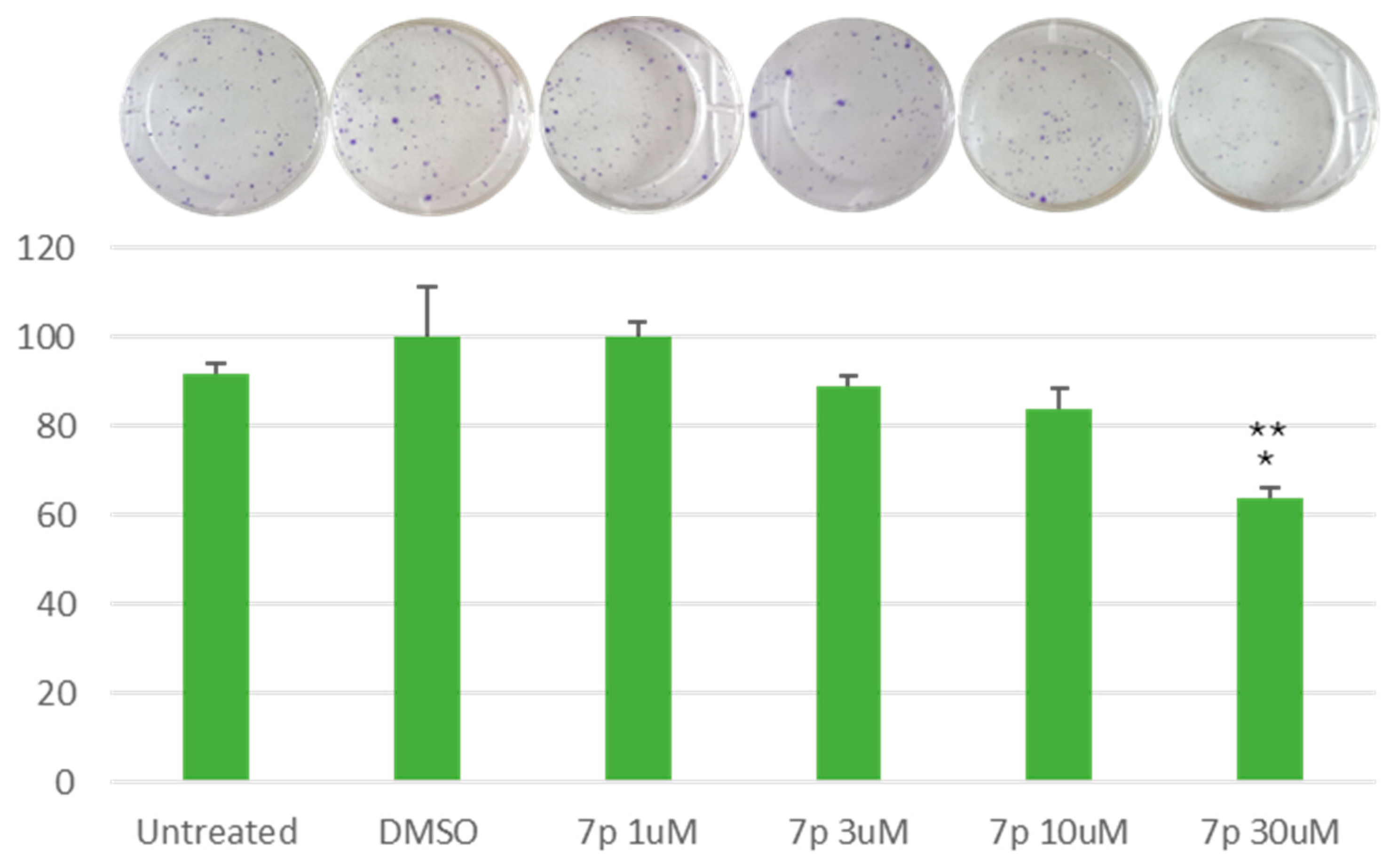

3.2.3. Clonogenic Assay on HeLa and MCF-7 Cells

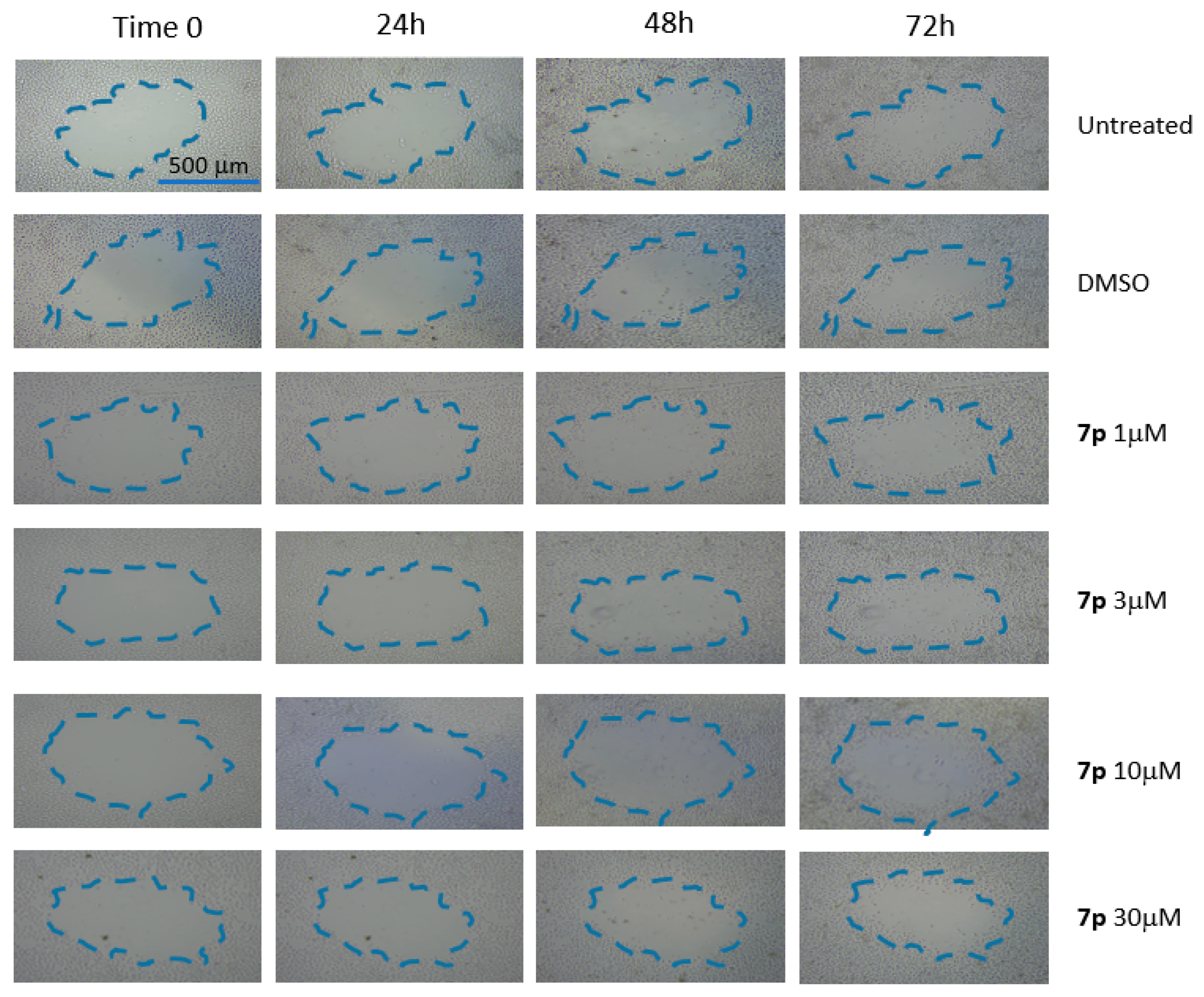

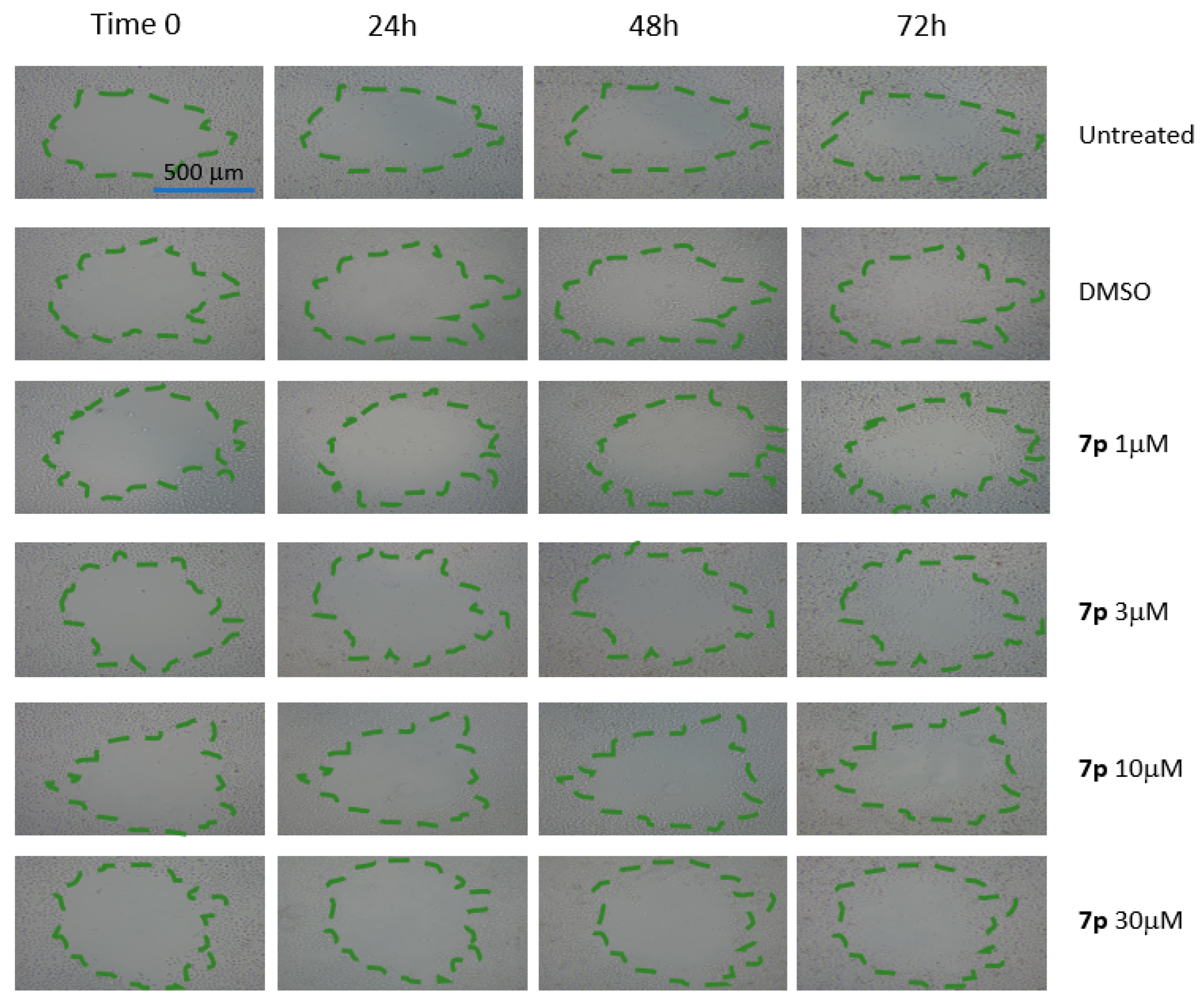

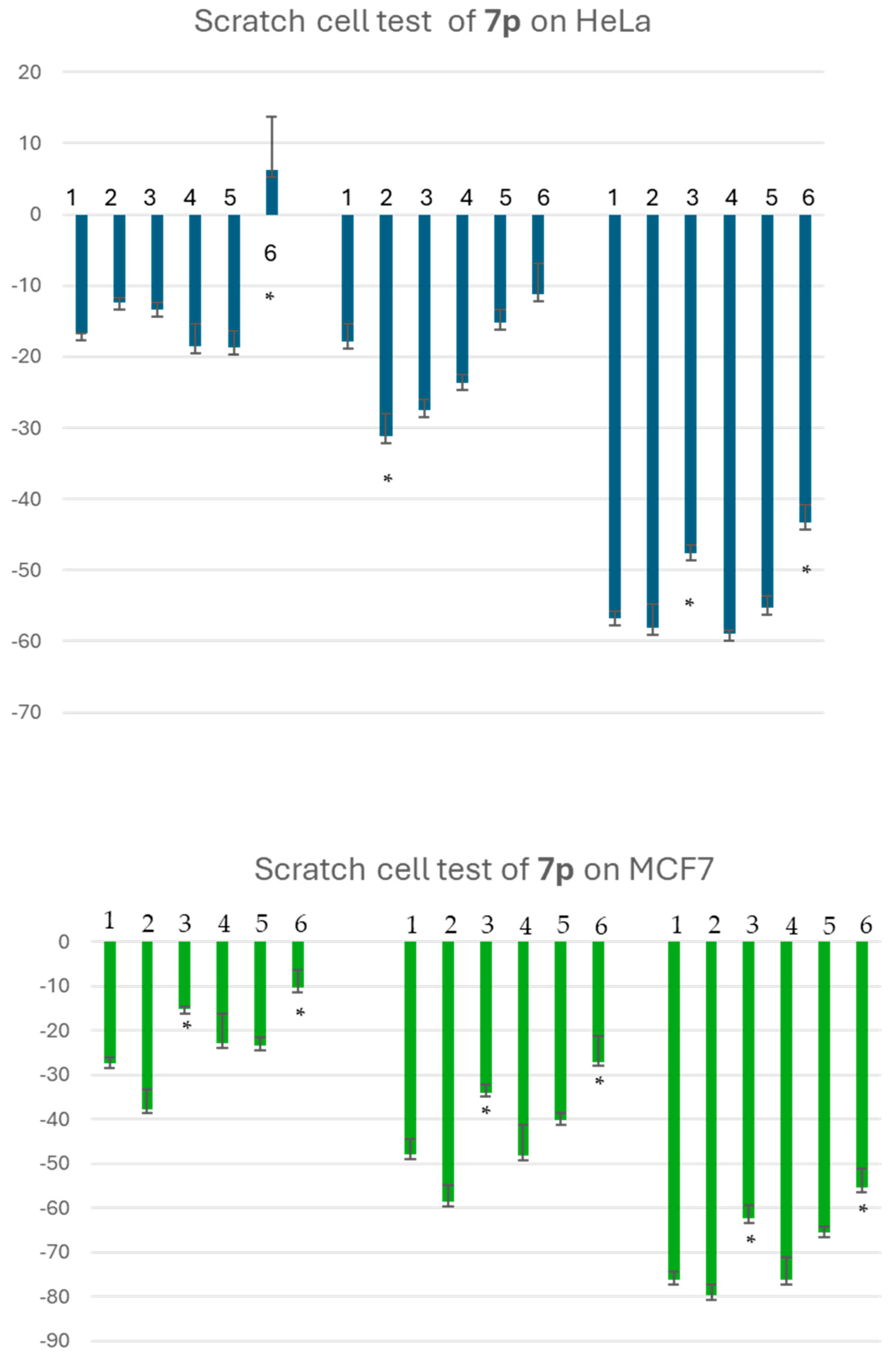

3.2.4. Scratch Test on HeLa and MCF-7 Cells

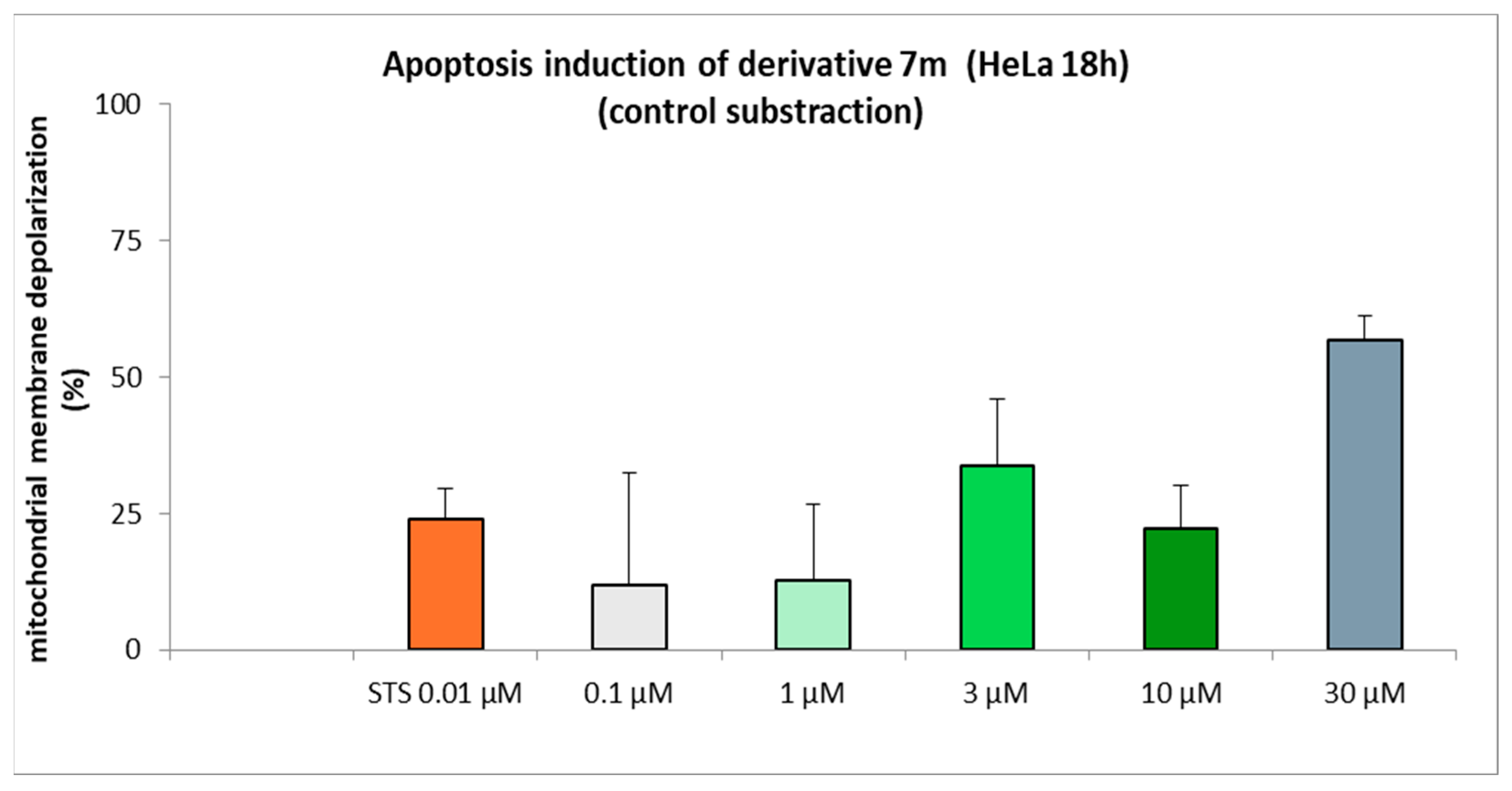

3.2.5. Apoptosis Induction of Derivative 7m on HeLa Cells

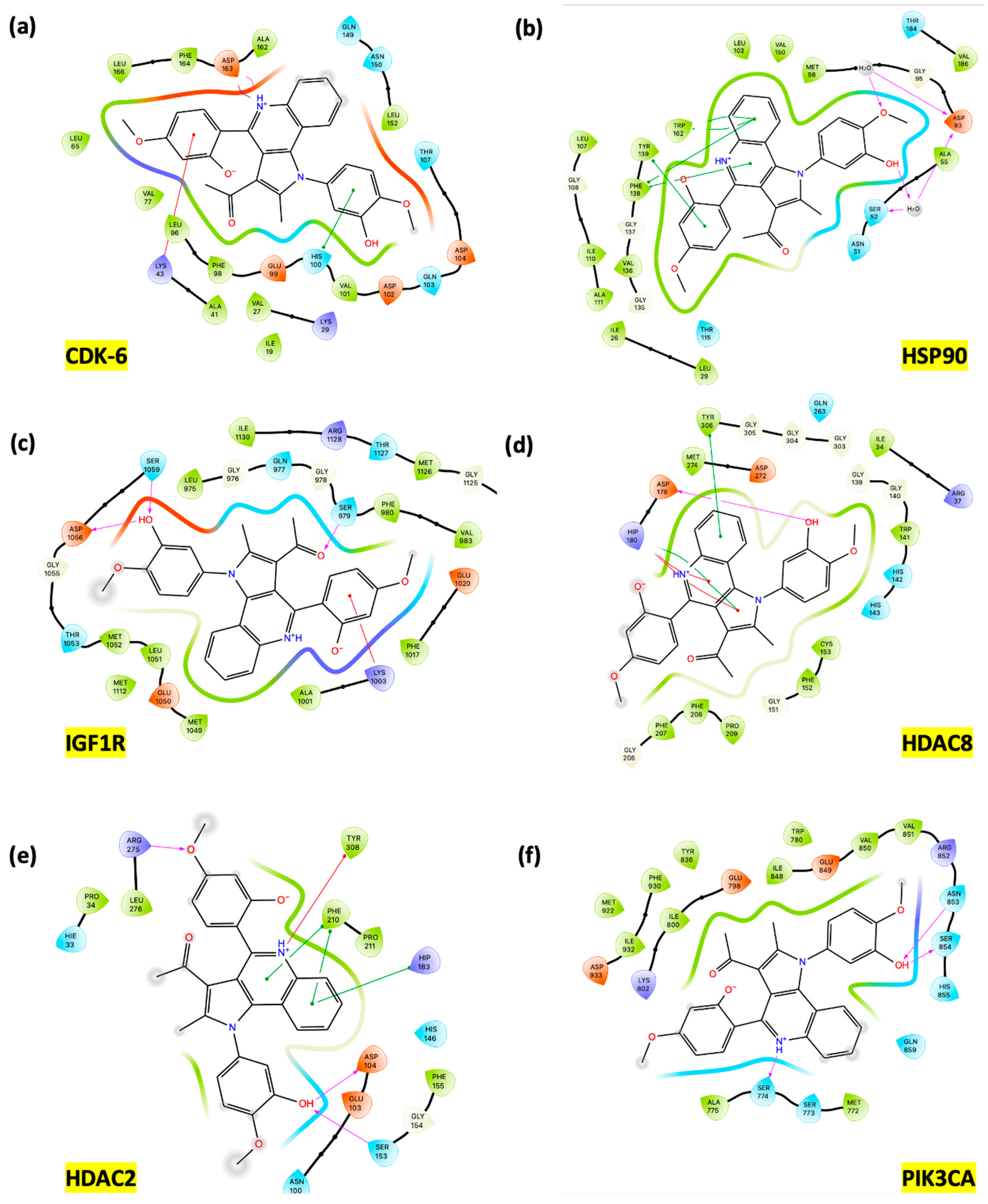

3.3. In Silico Studies: Induced Fit Docking Investigations

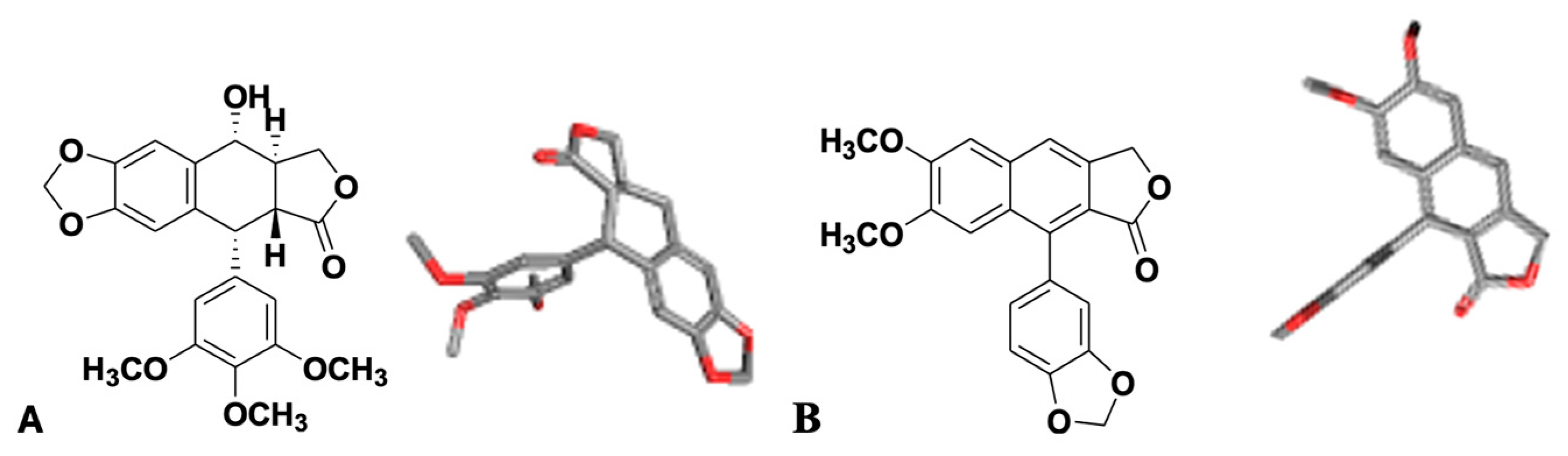

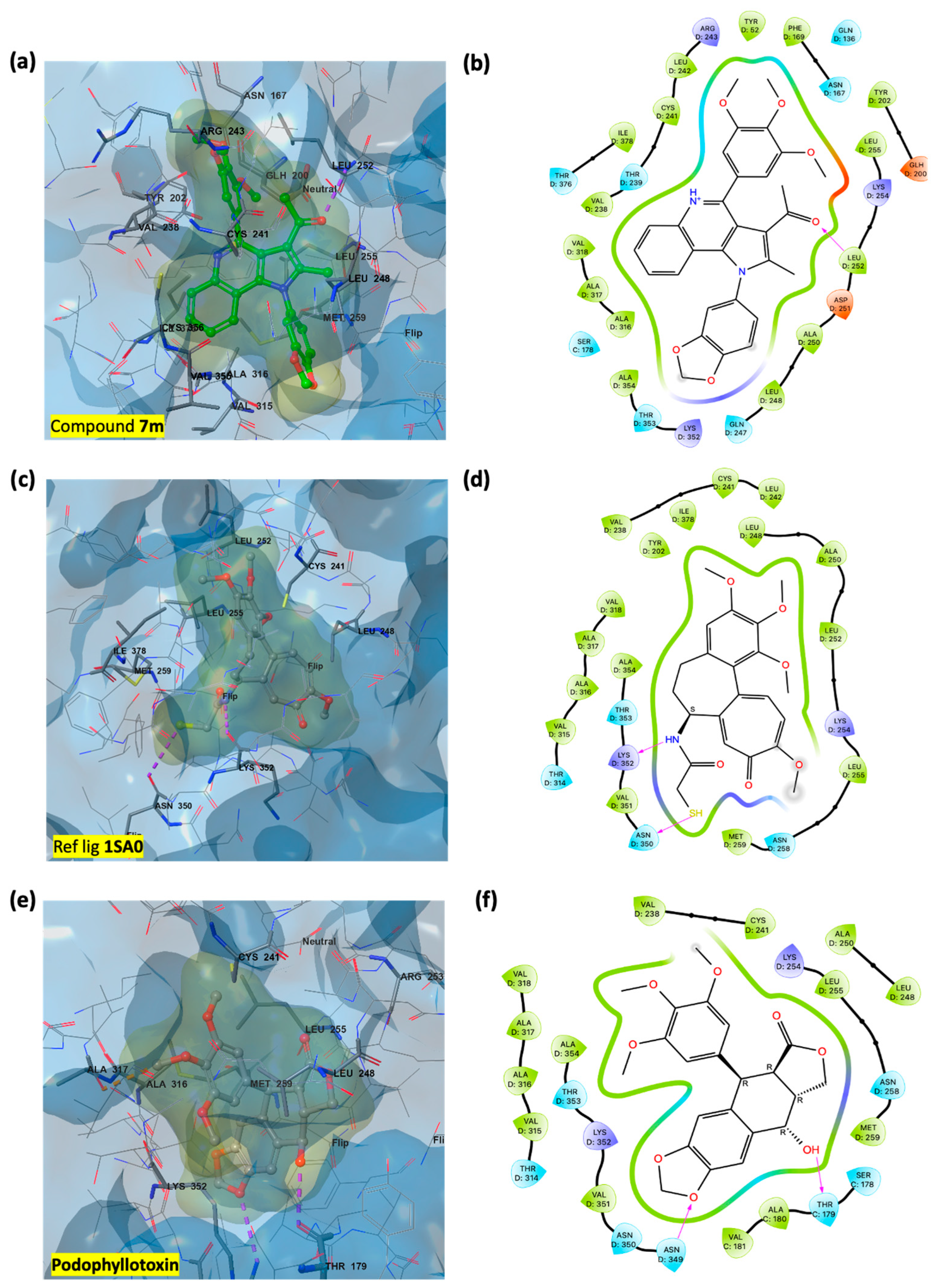

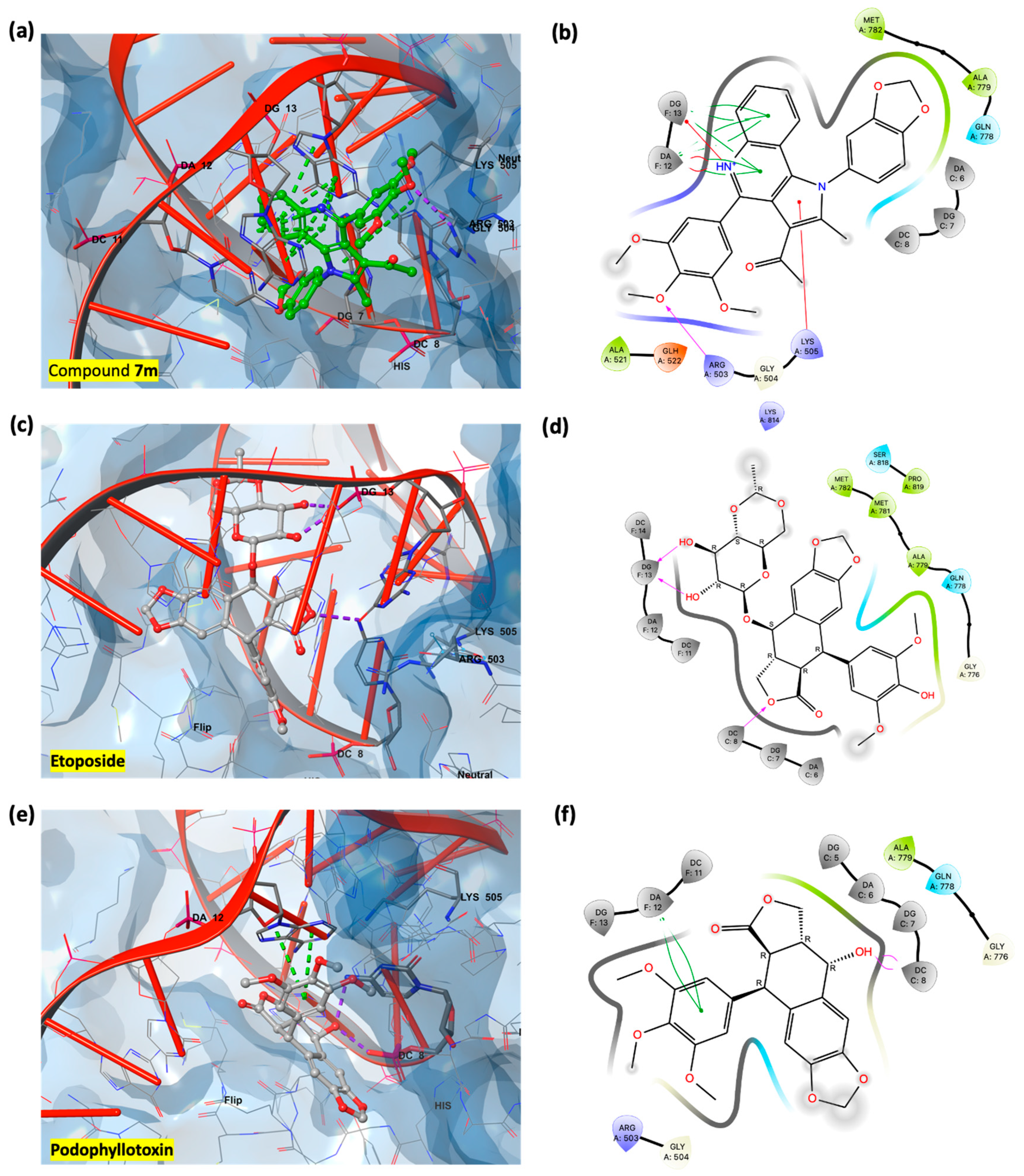

3.3.1. Assessment of Podophyllotoxin-like Mechanisms of Compound 7m Through Molecular Docking

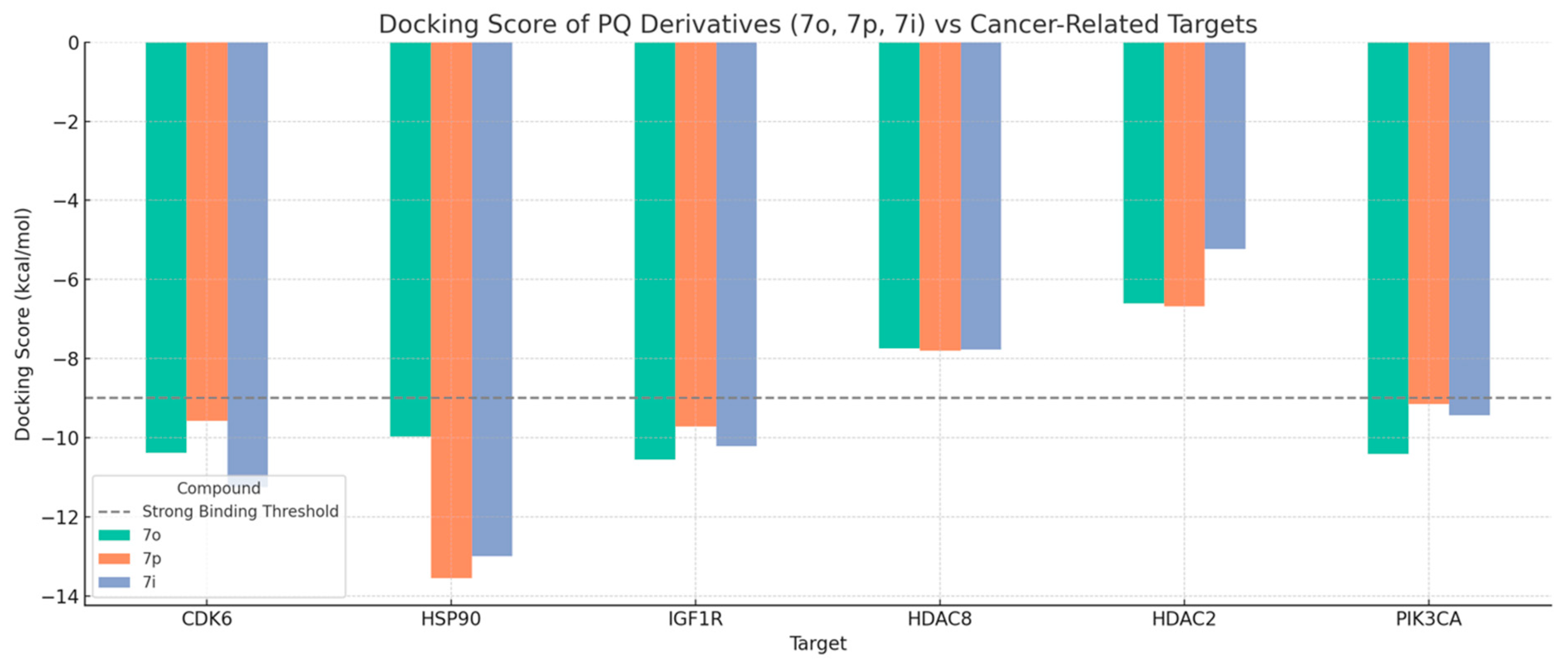

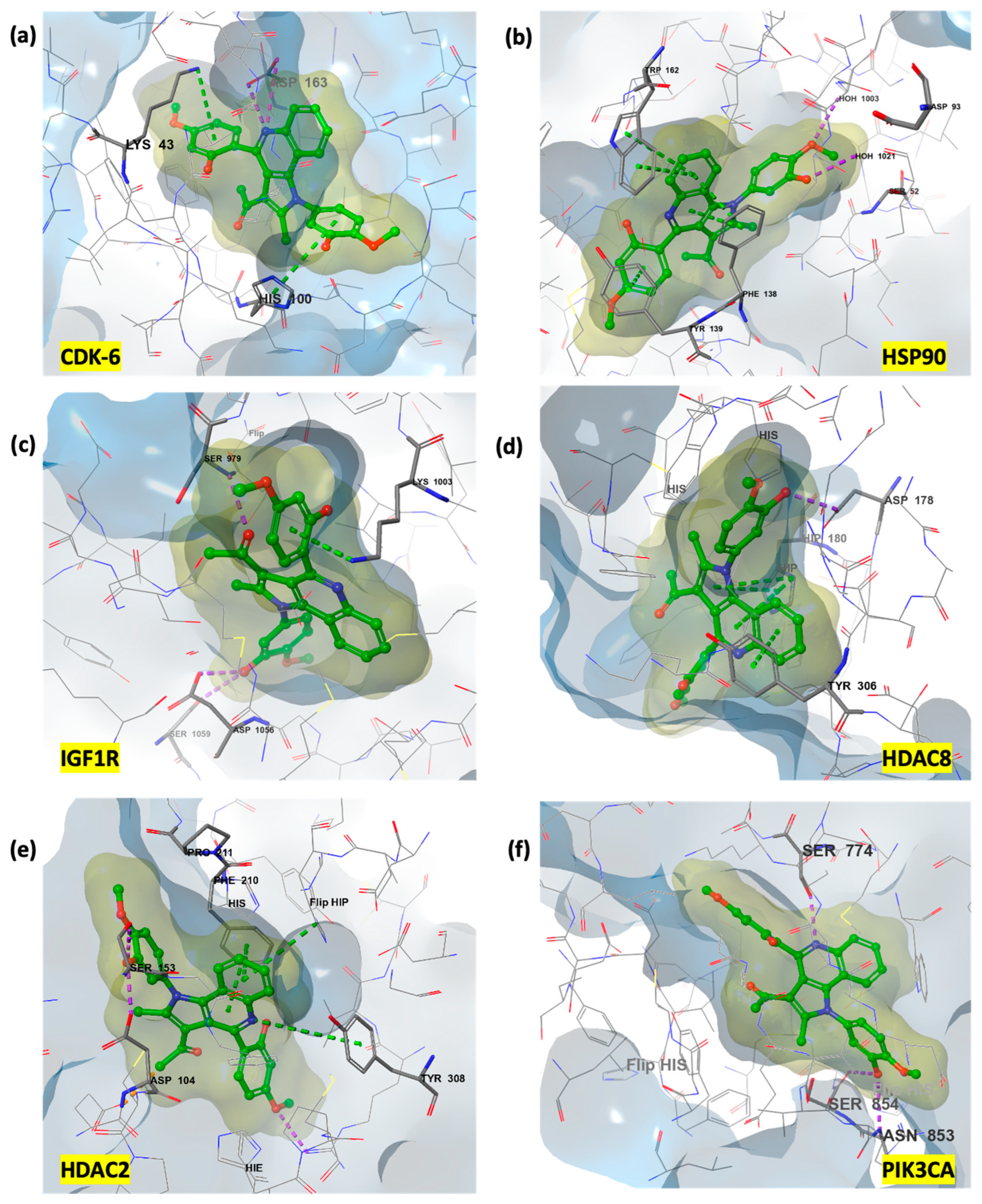

3.3.2. Rationalization of Antiproliferative Activity of PQ Derivatives Through Induced Fit Docking on Six Cancer-Associated Targets

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| GI50 | Growth Inhibition 50% |

| G% | percentage of cell growth |

| HSP90 | Heat Shock Protein 90 |

| GI% | percentage of cell growth inhibition |

| IGF1R | Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 Receptor |

| IFD | Induced Fit Docking |

| NCI | National Cancer Institute |

| PQ | Pyrrolo[3,2-c]quinoline |

| PPT | Podophyllotoxin |

| SRB | Sulforhodamine B |

| TSA | Toluenesulfonic acid |

| STS | Staurosporine |

| MTS | Tetrazolium salt (colorimetric agent for biotest) |

| CDK6 | Cyclin-dependent Kinase 6 |

| HDAC2 | Histone Deacetylase 2 |

| HDAC8 | Histone Deacetylase 8 |

| PIK3CA | PhosphatidylInositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-Kinase Catalytic subunit alpha |

References

- Lauria, A.; La Monica, G.; Bono, A.; Martorana, A. Quinoline anticancer agents active on DNA and DNA-interacting proteins: From classical to emerging therapeutic targets. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 220, 113555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Králová, P.; Soural, M. Biological Properties of Pyrroloquinoline and Pyrroloisoquinoline Derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 269, 116287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amărandi, R.-M.; Al-Matarneh, M.-C.; Popovici, L.; Ciobanu, C.I.; Neamțu, A.; Mangalagiu, I.I.; Danac, R. Exploring Pyrrolo-Fused Heterocycles as Promising Anticancer Agents: An Integrated Synthetic, Biological, and Computational Approach. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingoia, F.; Di Sano, C.; D’Anna, C.; Fazzari, M.; Minafra, L.; Bono, A.; La Monica, G.; Martorana, A.; Almerico, A.M.; Lauria, A. Synthesis of New Antiproliferative 1,3,4-Substituted-Pyrrolo[3,2-c]Quinoline Derivatives, Biological and in Silico Insights. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 258, 115537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, M.L.; Lamartina, L.; Mingoia, F. A New Entry to the Substituted Pyrrolo[3,2-c]Quinoline Derivatives of Biological Interest by Intramolecular Heteroannulation of Internal Imines. Tetrahedron 2004, 60, 5873–5880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohassab, A.M.; Hassan, H.A.; Abdelhamid, D.; Gouda, A.M.; Youssif, B.G.M.; Tateishi, H.; Fujita, M.; Otsuka, M.; Abdel-Aziz, M. Design and Synthesis of Novel Quinoline/Chalcone/1,2,4-Triazole Hybrids as Potent Antiproliferative Agent Targeting EGFR and BRAFV600E Kinases. Bioorg. Chem. 2021, 106, 104510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Lv, M.; Tian, X. A Review on Hemisynthesis, Biosynthesis, Biological Activities, Mode of Action, and Structure-Activity Relationship of Podophyllotoxins: 2003–2007. Curr. Med. Chem. 2008, 16, 327–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Rakesh, K.P.; Shantharam, C.S.; Manukumar, H.M.; Asiri, A.M.; Marwani, H.M.; Qin, H.L. Podophyllotoxin Derivatives as an Excellent Anticancer Aspirant for Future Chemotherapy: A Key Current Imminent Needs. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2018, 26, 340–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Song, Z.; Cai, F.; Ruan, L.; Jiang, R. Chemistry and Biological Activities of Naturally Occurring and Structurally Modified Podophyllotoxins. Molecules 2022, 28, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmati, S.; Seradj, H. Justicidin B: A Promising Bioactive Lignan. Molecules 2016, 21, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DellaGreca, M.; Zuppolini, S.; Zarrelli, A. Isolation of Lignans as Seed Germination and Plant Growth Inhibitors from Mediterranean Plants and Chemical Synthesis of Some Analogues. Phytochem. Rev. 2013, 12, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Qin, J.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, X.; Yang, M. 6′-Hydroxy Justicidin B Triggers a Critical Imbalance in Ca2+ Homeostasis and Mitochondrion-Dependent Cell Death in Human Leukemia K562 Cells. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 323303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Lee, E.; Choi, P.G.; Kim, H.S.; Park, S.H.; Seo, H.D.; Hahm, J.H.; Ahn, J.; Jung, C.H. Justicia Procumbens Prevents Hair Loss in Androgenic Alopecia Mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 170, 115913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, E.; Dattolo, G.; Cirrincione, G.; Plescia, S.E.; Daidone, G. Polycondensed Nitrogen Heterocycles. VII. 5,6-Dihydro-7-h-Pyrrolo[1,2-D]-[1,4] Benzodiazepin-6-Ones. A Novel Series of Annelatcd 1,4-Benzodiazepines. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1979, 16, 209–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingoia, F.; Di Sano, C.; Di Blasi, F.; Fazzari, M.; Martorana, A.; Almerico, A.M.; Lauria, A. Exploring the Anticancer Potential of Pyrazolo[1,2-a]Benzo[1,2,3,4]Tetrazin-3-One Derivatives: The Effect on Apoptosis Induction, Cell Cycle and Proliferation. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 64, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzozowska, B.; Gałecki, M.; Tartas, A.; Ginter, J.; Kaźmierczak, U.; Lundholm, L. Freeware Tool for Analysing Numbers and Sizes of Cell Colonies. Radiat. Environ. Biophys. 2019, 58, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger Release 2021-2, LigPrep, Schrödinger, LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2021.

- Schrödinger Release 2021-2: Protein Preparation Wizard, Epik, Schrödinger, LLC: New York, NY, USA; Impact, Schrödinger, LLC: New York, NY, USA; Prime, Schrödinger, LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2021.

- Banks, J.L.; Beard, H.S.; Cao, Y.; Cho, A.E.; Damm, W.; Farid, R.; Felts, A.K.; Halgren, T.A.; Mainz, D.T.; Maple, J.R.; et al. Integrated Modeling Program, Applied Chemical Theory (IMPACT). J. Comput. Chem. 2005, 26, 1752–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravelli, R.B.G.; Gigant, B.; Curmi, P.A.; Jourdain, I.; Lachkar, S.; Sobel, A.; Knossow, M. Insight into Tubulin Regulation from a Complex with Colchicine and a Stathmin-like Domain. Nature 2004, 428, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.-C.; Li, T.-K.; Farh, L.; Lin, L.-Y.; Lin, T.-S.; Yu, Y.-J.; Yen, T.-J.; Chiang, C.-W.; Chan, N.-L. Structural Basis of Type II Topoisomerase Inhibition by the Anticancer Drug Etoposide. Science 2011, 333, 459–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immormino, R.M.; Kang, Y.; Chiosis, G.; Gewirth, D.T. Structural and Quantum Chemical Studies of 8-Aryl-Sulfanyl Adenine Class Hsp90 Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 4953–4960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velaparthi, U.; Wittman, M.; Liu, P.; Stoffan, K.; Zimmermann, K.; Sang, X.; Carboni, J.; Li, A.; Attar, R.; Gottardis, M.; et al. Discovery and Initial SAR of 3-(1H-Benzo[d]Imidazol-2-Yl)Pyridin-2(1H)-Ones as Inhibitors of Insulin-like Growth Factor 1-Receptor (IGF-1R). Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 2317–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanan, E.J.; Braun, M.G.; Heald, R.A.; Macleod, C.; Chan, C.; Clausen, S.; Edgar, K.A.; Eigenbrot, C.; Elliott, R.; Endres, N.; et al. Discovery of GDC-0077 (Inavolisib), a Highly Selective Inhibitor and Degrader of Mutant PI3Kα. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 16589–16621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, M.; Johnson, Z.L.; Lee, S.Y. Visualizing Multistep Elevator-like Transitions of a Nucleoside Transporter. Nature 2017, 545, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauffer, B.E.L.; Mintzer, R.; Fong, R.; Mukund, S.; Tam, C.; Zilberleyb, I.; Flicke, B.; Ritscher, A.; Fedorowicz, G.; Vallero, R.; et al. Histone Deacetylase (HDAC) Inhibitor Kinetic Rate Constants Correlate with Cellular Histone Acetylation but Not Transcription and Cell Viability. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 26926–26943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, L.; Dobler, M.R.; Radetich, B.; Zhu, Y.; Atadja, P.W.; Claiborne, T.; Grob, J.E.; McRiner, A.; Pancost, M.R.; Patnaik, A.; et al. Human HDAC Isoform Selectivity Achieved via Exploitation of the Acetate Release Channel with Structurally Unique Small Molecule Inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2011, 19, 4626–4634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, H.M.; Westbrook, J.; Feng, Z.; Gilliland, G.; Bhat, T.N.; Weissig, H.; Shindyalov, I.N.; Bourne, P.E. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RCSB PDB. Available online: www.rcsb.org (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Madhavi Sastry, G.; Adzhigirey, M.; Day, T.; Annabhimoju, R.; Sherman, W. Protein and Ligand Preparation: Parameters, Protocols, and Influence on Virtual Screening Enrichments. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2013, 27, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolcsár, V.J.; Szőllősi, G. Synthesis of a Pyrrolo[1,2-a]Quinazoline-1,5-Dione Derivative by Mechanochemical Double Cyclocondensation Cascade. Molecules 2022, 27, 5671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monks, A.; Scudiero, D.; Skehan, P.; Shoemaker, R.; Paull, K.; Vistica, D.; Hose, C.; Langley, J.; Cronise, P.; Vaigro-wolff, A.; et al. Feasibility of a High-Flux Anticancer Drug Screen Using a Diverse Panel of Cultured Human Tumor Cell Lines. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1991, 83, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissADME: A Free Web Tool to Evaluate Pharmacokinetics, Drug-Likeness and Medicinal Chemistry Friendliness of Small Molecules. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanjai, C.; Hakkimane, S.S.; Guru, B.R.; Gaonkar, S.L. A Comprehensive Review on Anticancer Evaluation Techniques. Bioorg. Chem. 2024, 142, 106973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, H.S.; Lewis, W.; Williams, H.E.L.; Bradshaw, T.D.; Moody, C.J.; Stevens, M.F.G. Discovery of New Imidazotetrazinones with Potential to Overcome Tumor Resistance. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 257, 115507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franken, N.A.P.; Rodermond, H.M.; Stap, J.; Haveman, J.; van Bree, C. Clonogenic Assay of Cells in Vitro. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 2315–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cory, G. Scratch-Wound Assay. Methods Mol. Biol. 2011, 769, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, M.; Belvedere, R.; Petrella, A.; Iervasi, E.; Ponassi, M.; Brullo, C.; Spallarossa, A. Novel Tetrasubstituted 5-Arylamino Pyrazoles Able to Interfere with Angiogenesis and Ca2+ Mobilization. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 276, 116715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillarisetti, P.; Myers, K.A. Identification and Characterization of Agnuside, a Natural Proangiogenic Small Molecule. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 160, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancini, M.; Anderson, B.O.; Caldwell, E.; Sedghinasab, M.; Paty, P.B.; Hockenbery, D.M. Mitochondrial Proliferation and Paradoxical Membrane Depolarization during Terminal Differentiation and Apoptosis in a Human Colon Carcinoma Cell Line. J. Cell Biol. 1997, 138, 449–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDonald, J.A.; Kura, N.; Sussman, C.; Woods, D.C. Mitochondrial Membrane Depolarization Enhances TRAIL-Induced Cell Death in Adult Human Granulosa Tumor Cells, KGN, through Inhibition of BIRC5. J. Ovarian Res. 2018, 11, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancer-Rodríguez, J.; Gopar-Cuevas, Y.; García-Aguilar, K.; Chávez-Briones, M.d.L.; Miranda-Maldonado, I.; Ancer-Arellano, A.; Ortega-Martínez, M.; Jaramillo-Rangel, G. Cell Proliferation and Apoptosis—Key Players in the Lung Aging Process. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floryk, D.; Houštěk, J. Tetramethyl Rhodamine Methyl Ester (TMRM) Is Suitable for Cytofluorometric Measurements of Mitochondrial Membrane Potential in Cells Treated with Digitonin. Biosci. Rep. 1999, 19, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, S. Apoptosis by Death Factor. Cell 1997, 88, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, G.M. Caspases: The Executioners of Apoptosis. Biochem. J. 1997, 326, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alekseev, O.M.; Richardson, R.T.; Pope, M.R.; O’Rand, M.G. Mass Spectrometry Identification of NASP Binding Partners in HeLa Cells. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 2005, 61, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandhu, C.; Connor, M.; Kislinger, T.; Slingerland, J.; Emili, A. Global Protein Shotgun Expression Profiling of Proliferating MCF-7 Breast Cancer Cells. J. Proteome Res. 2005, 4, 674–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dupont, J.; Le Roith, D. Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 and Oestradiol Promote Cell Proliferation of MCF-7 Breast Cancer Cells: New Insights into Their Synergistic Effects. Mol. Pathol. 2001, 54, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alao, J.P.; Stavropoulou, A.V.; Lam, E.W.F.; Coombes, R.C.; Vigushin, D.M. Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor, Trichostatin A Induces Ubiquitin-Dependent Cyclin D1 Degradation in MCF-7 Breast Cancer Cells. Mol. Cancer 2006, 5, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.H.; Lin, C.L.I.; Tsal, J.H.; Ho, C.T.; Chen, W.J. 3,5,3′,4′,5′-Pentamethoxystilbene (MR-5), a Synthetically Methoxylated Analogue of Resveratrol, Inhibits Growth and Induces G1 Cell Cycle Arrest of Human Breast Carcinoma MCF-7 Cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 58, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nebenfuehr, S.; Kollmann, K.; Sexl, V. The Role of CDK6 in Cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2020, 147, 2988–2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De los Santos, M.; Martinez-Iglesias, O.; Aranda, A. Anti-Estrogenic Actions of Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors in MCF-7 Breast Cancer Cells. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2007, 14, 1021–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokar, F.; Mahabadi, J.A.; Salimian, M.; Taherian, A.; Hayat, S.M.G.; Sahebkar, A.; Atlasi, M.A. Differential Expression of HSP90 in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 Cell Lines after Treatment with Doxorubicin. J. Pharmacopunct. 2019, 22, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güven, C.M.; Özgür, A. BIIB021, an Orally Available and Small-Molecule Inhibitor of HSP90, Activates Intrinsic Apoptotic Pathway in Human Cervical Adenocarcinoma Cell Line (HeLa). Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 27, 7299–7308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleskandarany, M.A.; Rakha, E.A.; Ahmed, M.A.H.; Powe, D.G.; Paish, E.C.; Macmillan, R.D.; Ellis, I.O.; Green, A.R. PIK3CA Expression in Invasive Breast Cancer: A Biomarker of Poor Prognosis. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2010, 122, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, B.M.; Jana, L.; Kasajima, A.; Lehmann, A.; Prinzler, J.; Budczies, J.; Winzer, K.-J.; Dietel, M.; Weichert, W.; Denkert, C. Differential Expression of Histone Deacetylases HDAC1, 2 and 3 in Human Breast Cancer-Overexpression of HDAC2 and HDAC3 Is Associated with Clinicopathological Indicators of Disease Progression. BMC Cancer 2013, 13, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christopoulos, P.F.; Msaouel, P.; Koutsilieris, M. The Role of the Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 System in Breast Cancer. Mol. Cancer 2015, 14, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudouit, F.; Houssin, R.; Hénichart, J.P. A Synthesis of New Pyrrolo[3,2-c]Quinolines. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2001, 38, 755–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| |||

| Panel | Cell line | G% | GI% |

| Leukemia | SR | 31.64 | 68.36 |

| CNS | SNB75 | 46.47 | 53.53 |

| Melanoma | MDA-MB-435 | 42.11 | 57.89 |

| Renal | UO31 | 26.43 | 73.57 |

| Breast | MCF-7 | 41.49 | 58.51 |

| |||

| Panel | Cell line | G% | GI% |

| Leukemia | SR | 72.55 | 27.45 |

| CNS | SNB75 | 75.72 | 24.38 |

| Melanoma | MDA-MB-435 | 71.06 | 28.94 |

| Renal | UO31 | 52.94 | 47.06 |

| |||

| Panel | Cell line | G% | GI% |

| Leukemia | SR | 46.86 | 53.14 |

| K562 | 68.37 | 31.63 | |

| NSCLC | HOP62 | 69.72 | 30.28 |

| HOP92 | 69.45 | 30.55 | |

| CNS | SNB75 | 55.06 | 44.94 |

| Melanoma | UACC62 | 54.36 | 45.64 |

| Renal | UO31 | 40.72 | 59.28 |

| Breast | MCF-7 | 73.48 | 26.52 |

| |||

| Panel | Cell line | G% | GI% |

| Leukemia | SR | 59.17 | 40.83 |

| K562 | 71.32 | 28.68 | |

| CCRF-CEM | 67.59 | 32.41 | |

| MOLT-4 | 57.82 | 42.18 | |

| NSCLC | HOP62 | 69.82 | 30.18 |

| CNS | SNB-75 | 65.24 | 34.76 |

| Renal | A498 | 64.96 | 35.03 |

| UO31 | 55.38 | 44.62 | |

| Breast | T-47D | 69.70 | 30.30 |

| |||

| Cancer Panel | Cell line | G% | GI% |

| Leukemia | SR | 65.60 | 34.40 |

| K562 | 70.80 | 29.20 | |

| CCRF-CEM | 75.57 | 24.43 | |

| MOLT-4 | 65.34 | 34.66 | |

| Colon | HCT-15 | 70.80 | 29.20 |

| Renal | UO31 | 69.43 | 30.57 |

| |||

| Cancer Panel | Cell line | G% | GI% |

| Renal | UO31 | 72.34 | 27.66 |

| |||

| Cancer Panel | Cell line | G% | GI% |

| Renal | UO31 | 68.98 | 31.02 |

| |||

| Cancer Panel | Cell line | G% | GI% |

| Leukemia | SR | 70.23 | 29.77 |

| Renal | UO31 | 60.63 | 39.37 |

| Breast | T-47D | 7265 | 27.35 |

| |||

| Cancer Panel | Cell line | G% | GI% |

| Leukemia | SR | 47.98 | 52.02 |

| K562 | 75.04 | 24.96 | |

| NSCLC | NCI-H522 | 73.75 | 26.25 |

| Melanoma | UACC62 | 71.94 | 28.06 |

| Renal | UO31 | 52.21 | 47.79 |

| Compound | MW | Consensus Log P | TPSA | GI Absorption | L, G, V, E, and M Violations * | PAINS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7d | 344.36 | 3.77 | 64.21 | High | 0 | 0 |

| 7f | 346.38 | 3.52 | 75.21 | High | 0 | 0 |

| Tumour Cell |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAN5 | 17.8 | 16.6 | 77.4 | 25.2 | 90.8 | 27.2 | 33.6 |

| H292 | 91.3 | 38.2 | 67.2 | 55 | 92.4 | 40.4 | 22.4 |

| 16HBE | 22.2 | 17.9 | 52 | 16.5 | 59.4 | 22.3 | 34.2 |

| HeLa | 75.3 | 38.5 | 40.3 | 38.2 | 46.7 | 71.3 | 16.4 |

| MCF7 | 10.6 | 15.7 | 16.7 | 18.4 | 17.5 | 13.6 | 2.8 |

| Caco2 | 20.2 | 16.6 | 58.5 | 28.2 | 50.7 | 15.8 | 25.3 |

| Tubulin (1SA0) | Topoisomerase II (3QX3) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cpd * | Dock * | IFD * | Cpd * | Dock * | IFD * |

| 7m | −11.813 | −1753.29 | 7m | −8.028 | −1686.15 |

| Lig co-cryst | −11.152 | −1749.12 | Etoposide (Lig co-cryst) | −7.552 | −1685.51 |

| Podophyllotoxin | −11.331 | −1749.08 | Podophyllotoxin | −6.232 | −1681.10 |

| CDK6 | HSP90 | IGF1R | ||||||

| Cpd * | Dock * | IFD * | Cpd * | Dock * | IFD * | Cpd * | Dock * | IFD * |

| 7o | −10.381 | −568 | 7i | −13.002 | −479.36 | 7m | −11.967 | −658.69 |

| 7l | −10.814 | −567.42 | 7p | −13.558 | −478.93 | 7n | −10.186 | −658.08 |

| 7n | −9.875 | −567.04 | Ref lig | −11.662 | −477.17 | 7o | −10.562 | −656.07 |

| 7i | −11.246 | −567.02 | 7j | −10.554 | −476.58 | 7h | −10.664 | −655.34 |

| 7h | −11.04 | −566.38 | 7l | −10.476 | −475.48 | 7p | −9.72 | −654.49 |

| Ref lig | −11.934 | −566.26 | 7n | −9.924 | −475.17 | 7j | −10.456 | −654.43 |

| 7j | −10.296 | −565.65 | 7h | −10.793 | −475.1 | 7i | −10.208 | −653.94 |

| 7p | −9.579 | −564.6 | 7f | −10.432 | −474.97 | 7k | −10.536 | −653.63 |

| 7k | −9.093 | −564.1 | 7d | −10.25 | −474.74 | 7f | −9.157 | −653.45 |

| 7g | −10.38 | −563.37 | 7q | −10.007 | −474.54 | 7g | −9.461 | −653.44 |

| 7d | −10.323 | −563.11 | 7k | −10.11 | −473.91 | 7d | −10.782 | −653.33 |

| 7e | −9.747 | −562.89 | 7g | −10.566 | −473.07 | Ref lig | −9.929 | −652.72 |

| 7q | −8.264 | −562.73 | 7o | −9.967 | −472.94 | 7q | −9.291 | −652.35 |

| 7m | −8.32 | −562.73 | 7e | −10.216 | −472.22 | 7l | −8.84 | −652.08 |

| 7f | −9.132 | −562.63 | 7m | −8.986 | −471.29 | 7e | −11.528 | −652.04 |

| HDAC8 | HDAC2 | PIK3CA | ||||||

| Cpd * | Dock * | IFD * | Cpd * | Dock * | IFD * | Cpd * | Dock * | IFD * |

| 7j | −9.346 | −746.07 | 7o | −6.601 | −845.79 | 7o | −10.417 | −2036.46 |

| 7l | −8.985 | −745.9 | 7n | −5.51 | −845.61 | 7n | −8.961 | −2035.25 |

| 7d | −10.333 | −745.79 | 7k | −6.769 | −845.28 | Ref lig | −9.937 | −2035.15 |

| 7q | −9.117 | −744.87 | 7j | −6.221 | −845.21 | 7l | −8.669 | −2034.97 |

| Ref lig | −10.116 | −744.81 | 7f | −6.91 | −845.17 | 7i | −9.43 | −2034.95 |

| 7e | −8.741 | −744.25 | 7h | −6.815 | −845.08 | 7m | −9.031 | −2034.93 |

| 7n | −7.742 | −744.13 | 7p | −6.678 | −844.96 | 7p | −9.146 | −2034.92 |

| 7k | −8.324 | −743.82 | 7l | −5.936 | −844.42 | 7h | −9.319 | −2034.65 |

| 7m | −8.171 | −743.58 | 7m | −6.219 | −843.99 | 7f | −8.439 | −2033.96 |

| 7i | −7.766 | −743.48 | 7i | −5.227 | −843.69 | 7g | −10.58 | −2033.72 |

| 7p | −7.804 | −742.76 | 7q | −6.077 | −843.68 | 7j | −6.799 | −2033.45 |

| 7f | −7.143 | −742.18 | 7g | −6.094 | −842.73 | 7k | −8.445 | −2033.15 |

| 7h | −7.763 | −741.92 | 7e | −6.117 | −842.5 | 7q | −8.695 | −2032.86 |

| 7g | −8.199 | −741.89 | 7d | −5.434 | −842.45 | 7d | −8.233 | −2032.48 |

| 7o | −7.749 | −741.83 | Ref lig | −4.997 | −841.81 | 7e | −10.059 | −2031.87 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mingoia, F.; Di Sano, C.; D’Anna, C.; Fazzari, M.; Bono, A.; La Monica, G.; Martorana, A.; Lauria, A. Tuning Scaffold Properties of New 1,4-Substituted Pyrrolo[3,2-c]quinoline Derivatives Endowed with Anticancer Potential, New Biological and In Silico Insights. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1718. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121718

Mingoia F, Di Sano C, D’Anna C, Fazzari M, Bono A, La Monica G, Martorana A, Lauria A. Tuning Scaffold Properties of New 1,4-Substituted Pyrrolo[3,2-c]quinoline Derivatives Endowed with Anticancer Potential, New Biological and In Silico Insights. Biomolecules. 2025; 15(12):1718. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121718

Chicago/Turabian StyleMingoia, Francesco, Caterina Di Sano, Claudia D’Anna, Marco Fazzari, Alessia Bono, Gabriele La Monica, Annamaria Martorana, and Antonino Lauria. 2025. "Tuning Scaffold Properties of New 1,4-Substituted Pyrrolo[3,2-c]quinoline Derivatives Endowed with Anticancer Potential, New Biological and In Silico Insights" Biomolecules 15, no. 12: 1718. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121718

APA StyleMingoia, F., Di Sano, C., D’Anna, C., Fazzari, M., Bono, A., La Monica, G., Martorana, A., & Lauria, A. (2025). Tuning Scaffold Properties of New 1,4-Substituted Pyrrolo[3,2-c]quinoline Derivatives Endowed with Anticancer Potential, New Biological and In Silico Insights. Biomolecules, 15(12), 1718. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121718