Comparative Transcriptomics Reveals the Molecular Basis for Inducer-Dependent Efficiency in Gastrodin Propionylation by Aspergillus oryzae Whole-Cell Biocatalyst

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microorganism and Chemicals

2.2. Cultivation and Induction of A. oryzae

2.3. Propionylation of Gastrodin by A. oryzae Whole Cells in Ionic Liquid-Containing System

2.4. Detection and Quantification of Substrate and Products

2.5. Biomass Quantification

2.6. RNA Library Construction and Transcriptome Sequencing

2.7. Homology Modeling and Molecular Docking

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

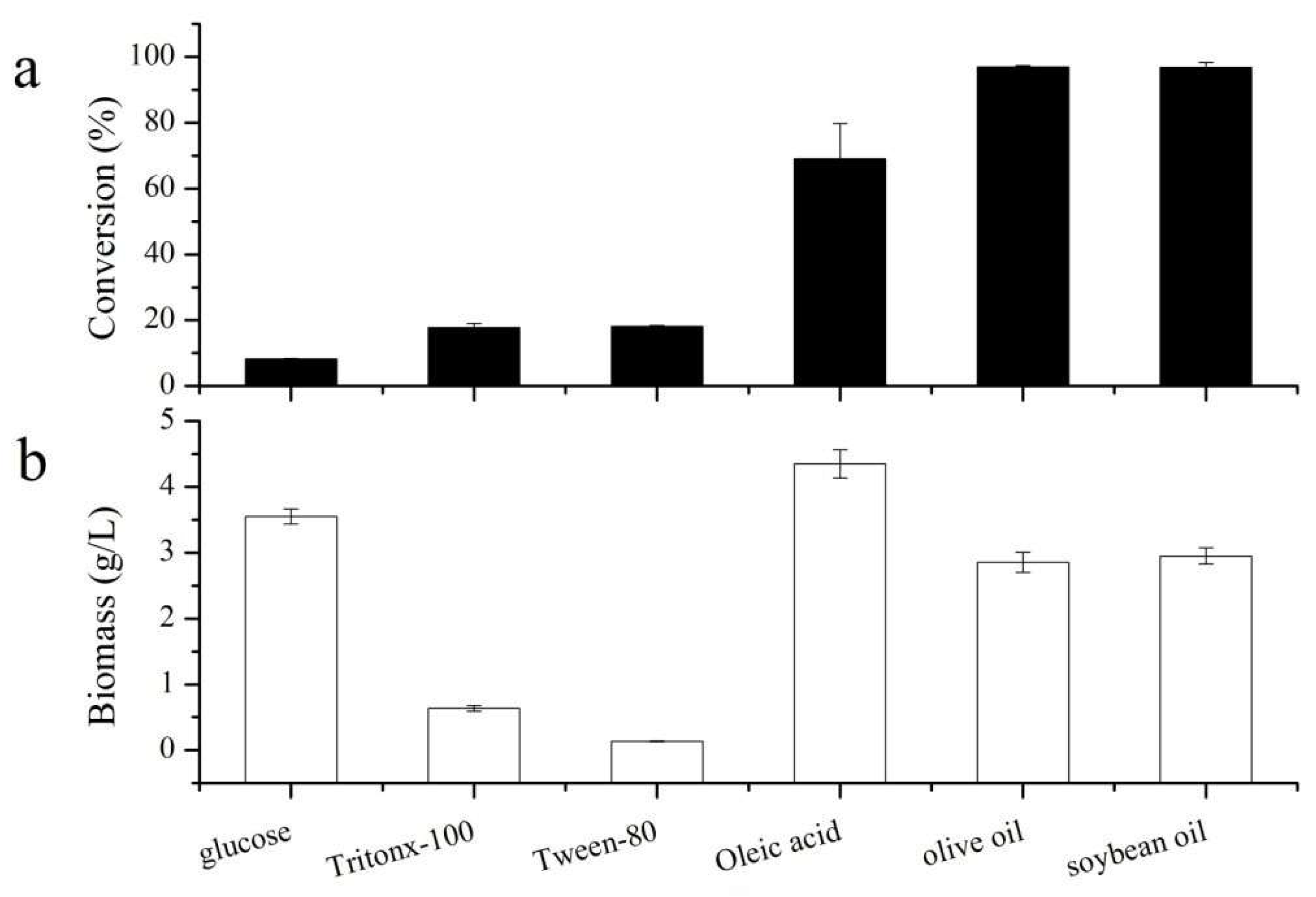

3.1. Effect of Inducer Type on the Catalytic Activity of A. oryzae Whole Cells in Gastrodin Propionylation and on Biomass

3.2. RNA Quality Assessment and De Novo Assembly Evaluation

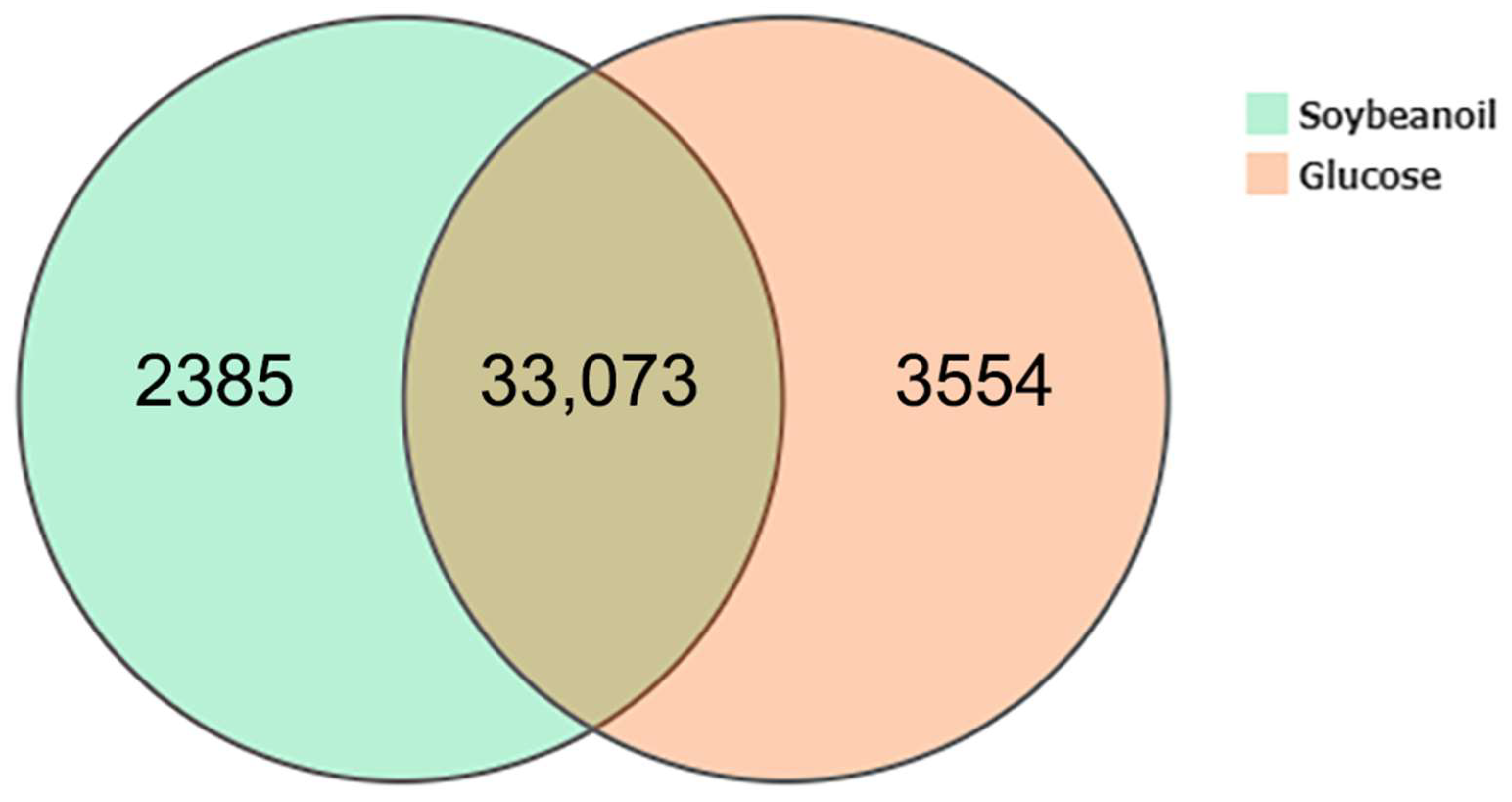

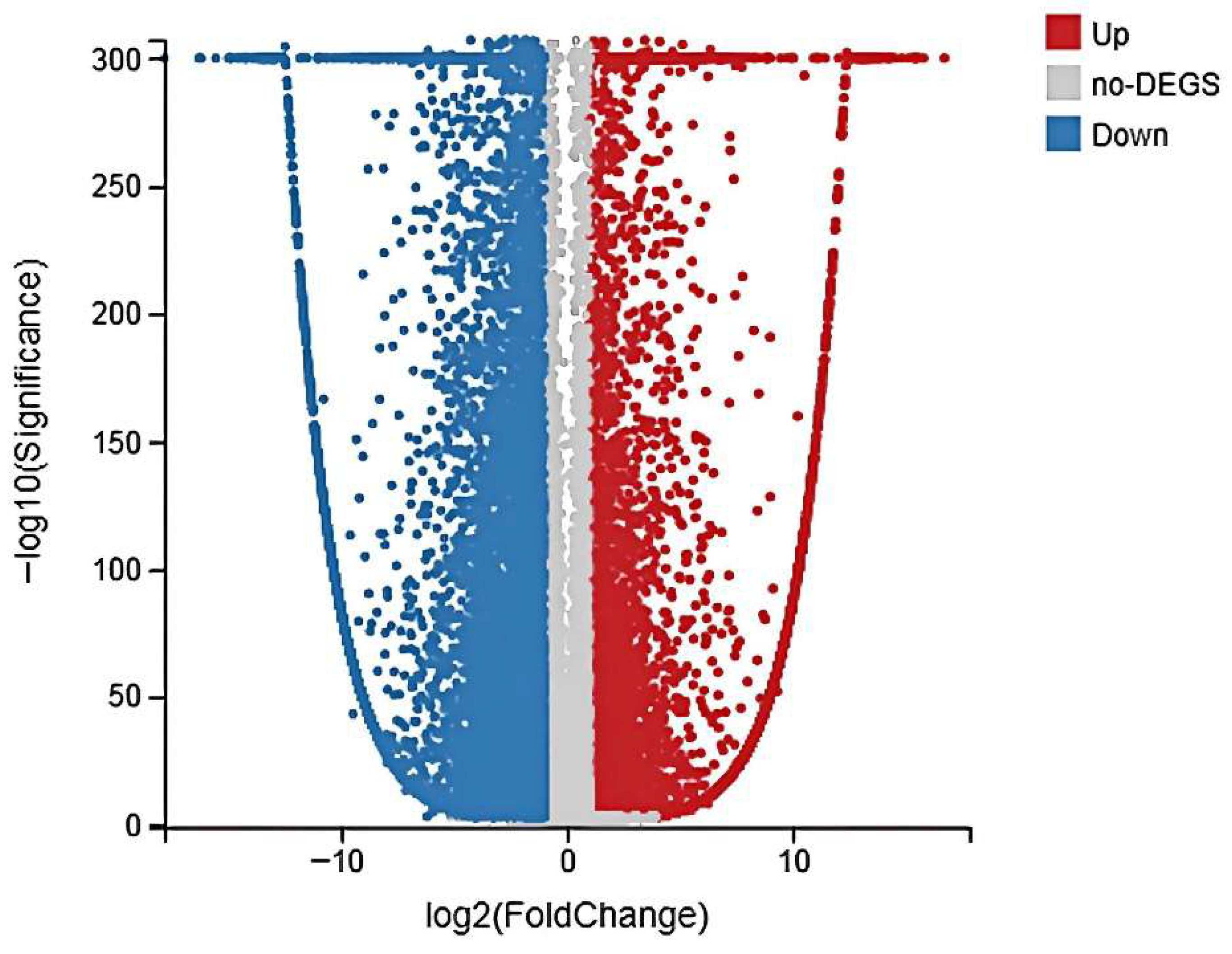

3.3. Global Gene Expression and Identification of DEGs

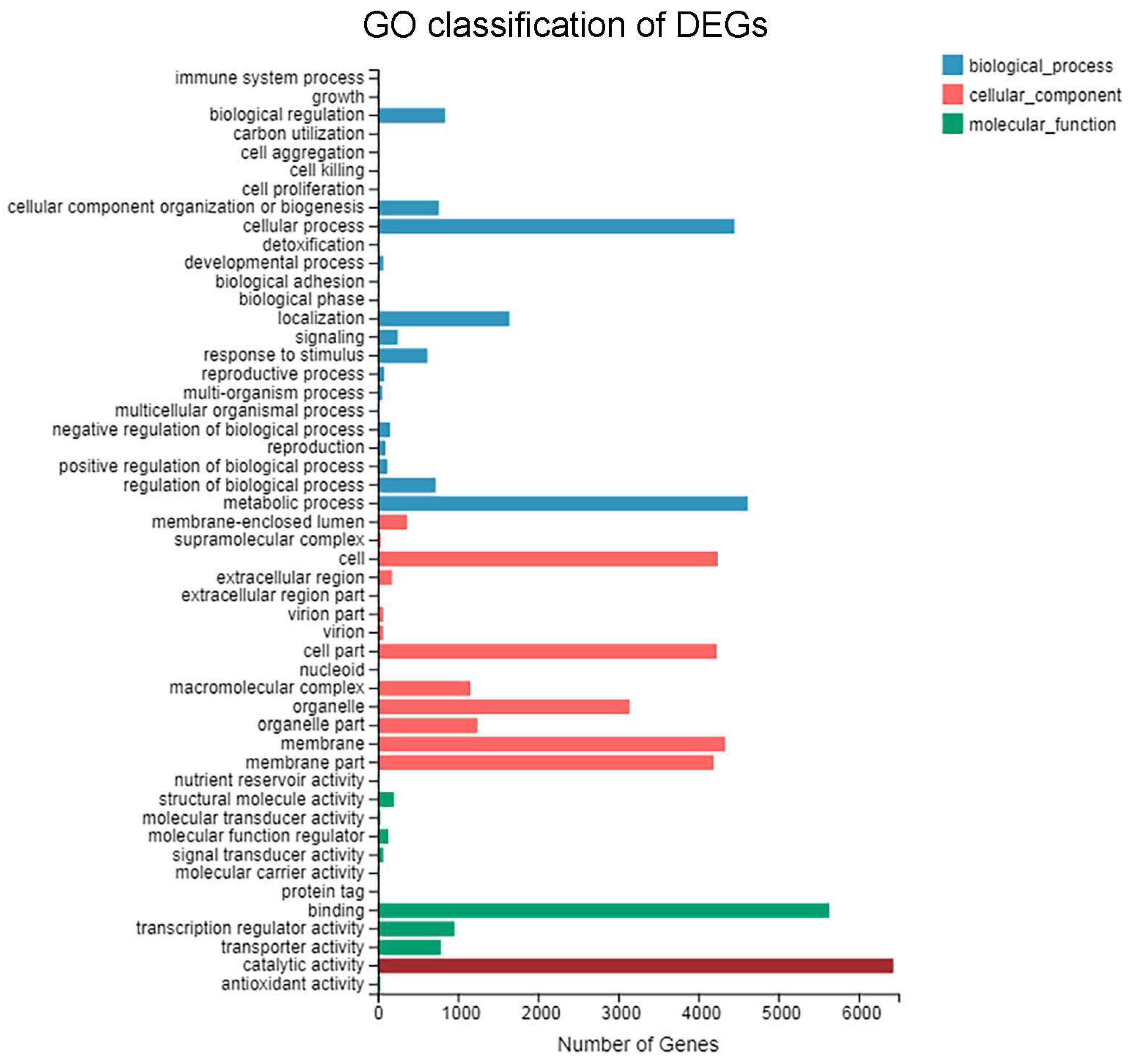

3.4. GO Functional Enrichment Analysis of DEGs

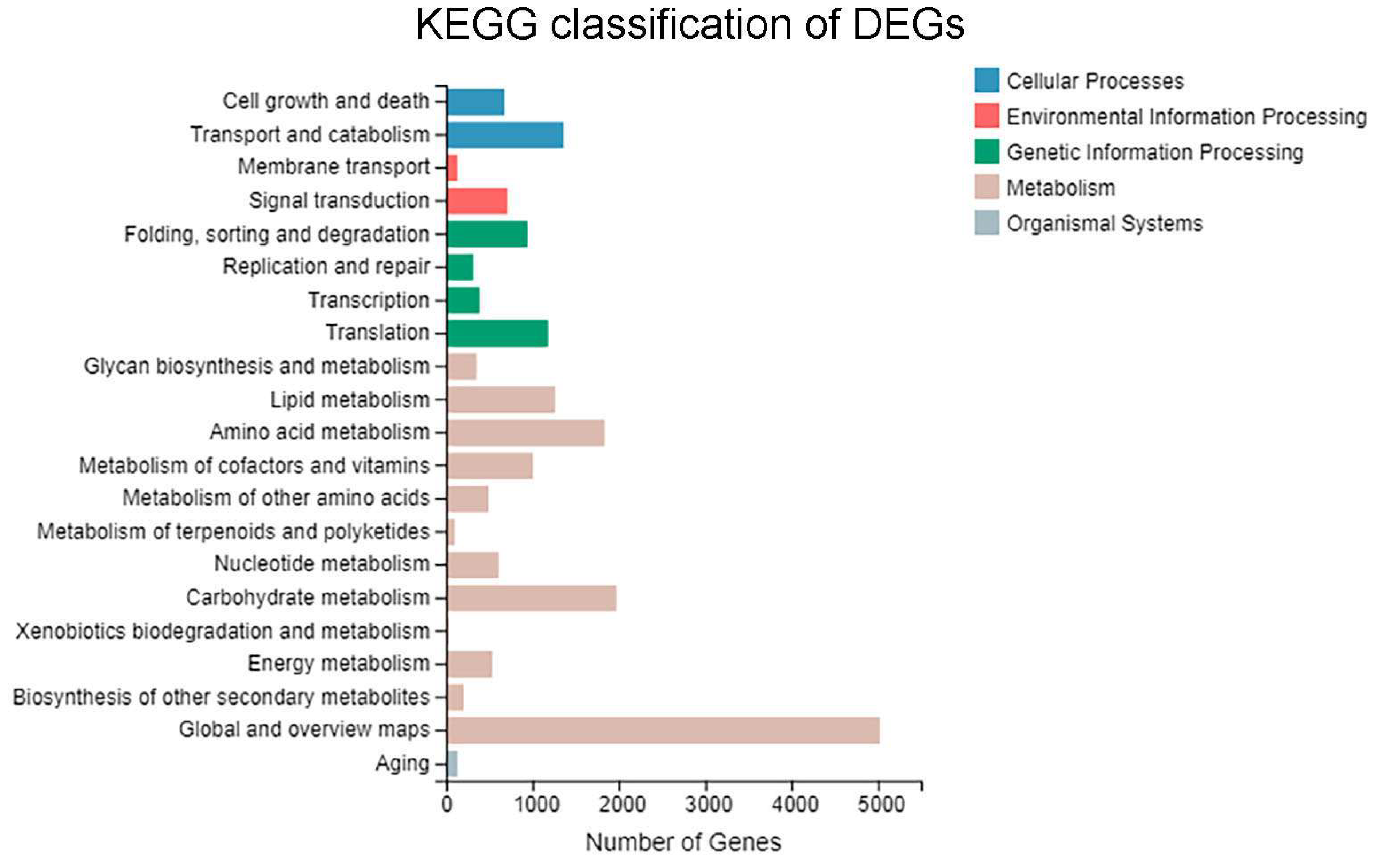

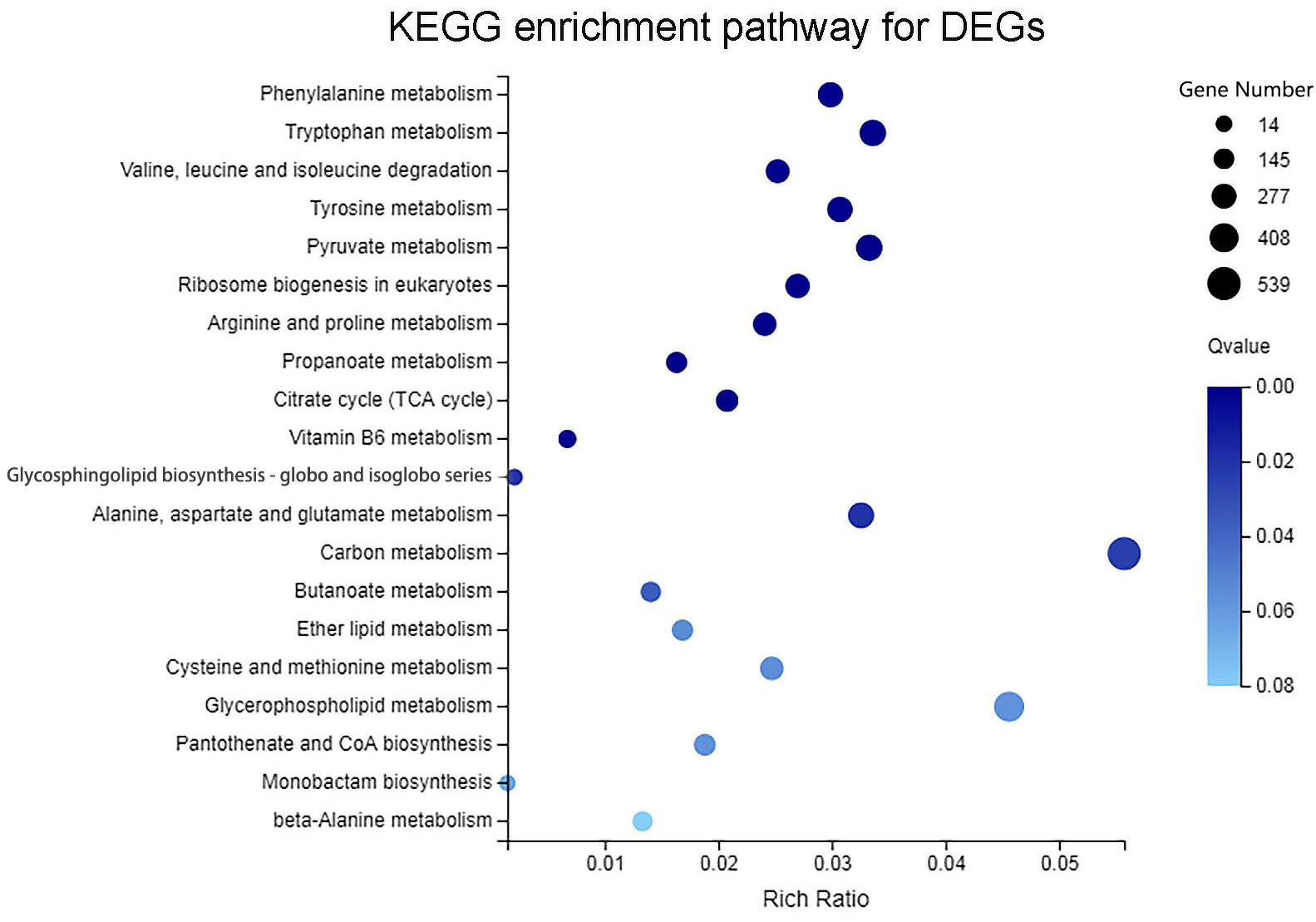

3.5. KEGG Pathway Enrichment Analysis of DEGs

3.6. Prioritization of Key Candidate Lipase Genes from DEGs

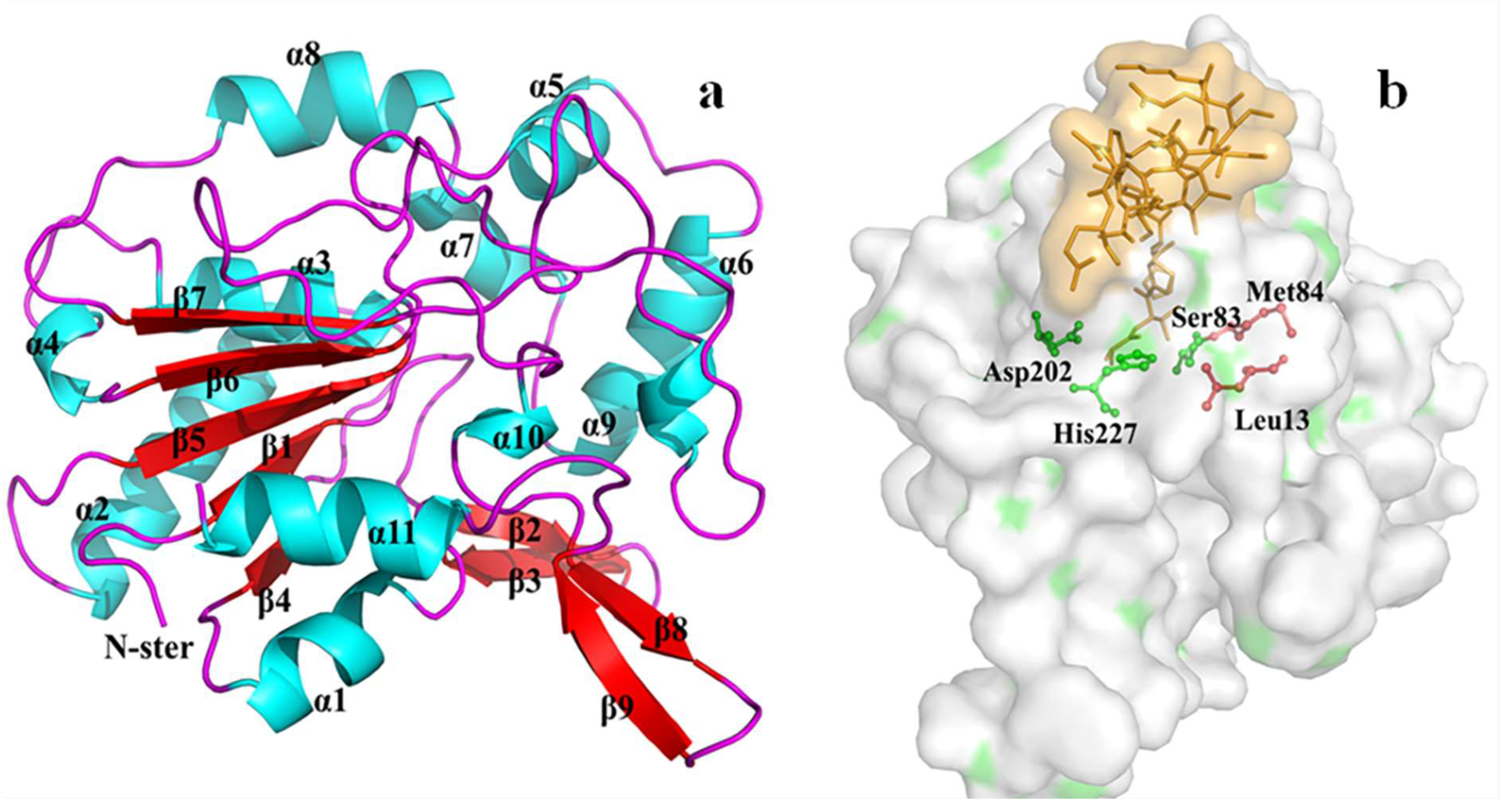

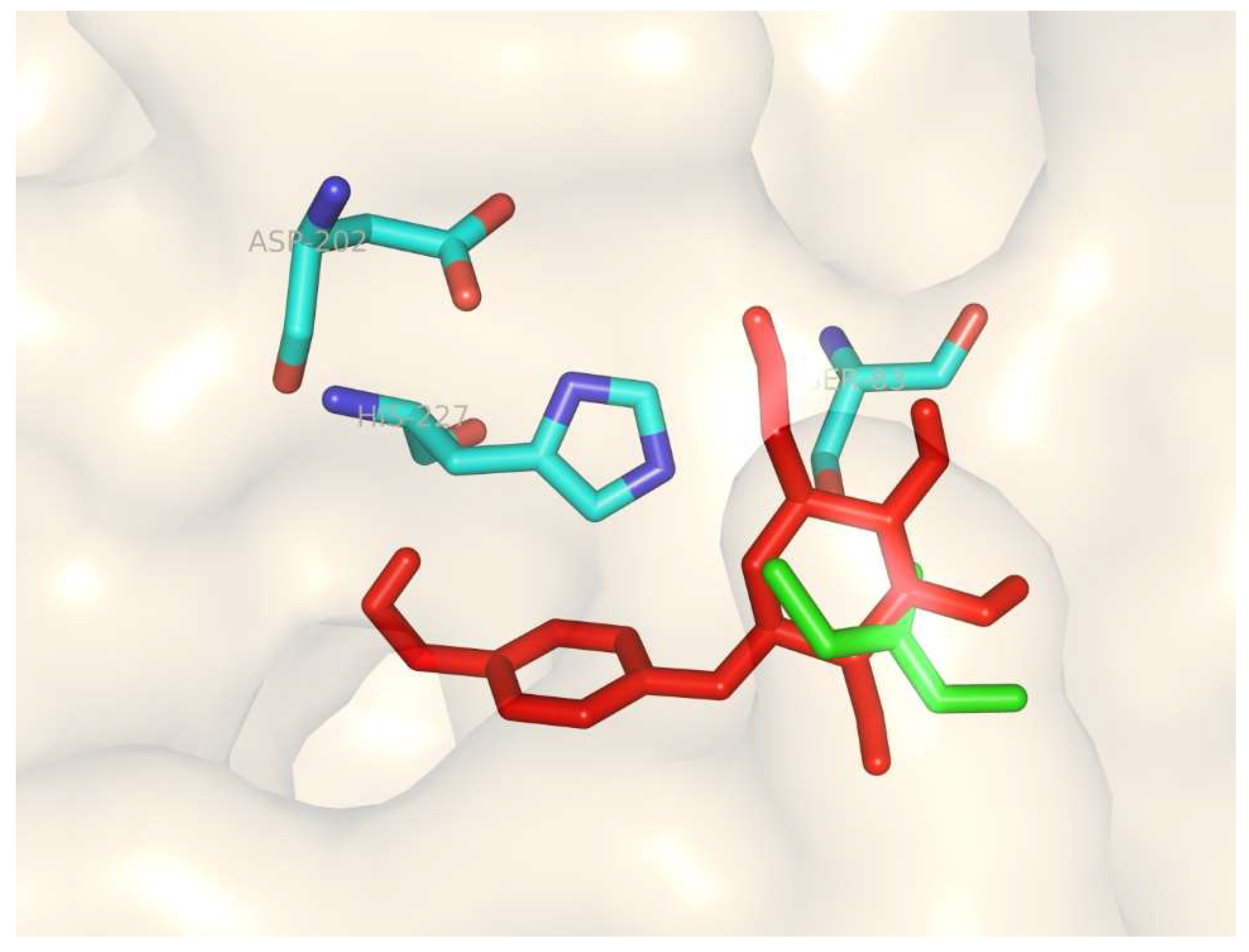

3.7. Homology Modeling and Molecular Docking of the Differentially Expressed Lipase

3.8. Analysis of the Regulatory Mechanism Underlying High Lipase Expression Induced by Soybean Oil

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, Y.; Gao, J.; Peng, M.; Meng, H.; Ma, H.; Cai, P.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Si, G. A Review on Central Nervous System Effects of Gastrodin. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y.; Yin, H.; Bi, H.; Zhuang, Y.; Liu, T.; Ma, Y. De novo biosynthesis of Gastrodin in Escherichia coli. Metab. Eng. 2016, 35, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Tian, W.; Wang, Q.; Shangguan, C.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Yue, L.; Chen, C. Evaluation of the changes in active substances and their effects on intestinal microflora during simulated digestion of Gastrodia elata. LWT 2022, 169, 113924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Cheng, D.; Zhang, C.; Xue, F. The Pharmacological Effects of Gastrodin and the Progress in the Treatment of Neurological Disorders. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2025, 53, 803–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, F.; Zeng, S.; Huang, C. Unraveling stabilization mechanisms in advanced starch nanoemulsions: From fabrication to food preservation applications. Food Hydrocoll. 2026, 173, 112249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokioja, J.; Yang, B.; Linderborg, K.M. Acylated anthocyanins: A review on their bioavailability and effects on postprandial carbohydrate metabolism and inflammation. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 5570–5615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, K.; Wang, X.; Huang, B.; Wu, X.; Shen, S.; Lin, Z.; Zhao, J.; Cai, Z. Comparative study on the intestinal absorption of three gastrodin analogues via the glucose transport pathway. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 163, 105839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmstrøm, T.; Pedersen, C.M. Enzyme-Catalyzed Regioselective Acetylation of Functionalized Glycosides. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 2020, 4612–4615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Jahan, F.; Mahajan, R.V.; Saxena, R.K. Efficient regioselective acylation of quercetin using Rhizopus oryzae lipase and its potential as antioxidant. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 218, 1246–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Zhang, Y.; Simpson, B. Food enzymes immobilization: Novel carriers, techniques and applications. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2022, 43, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.; Ye, Y.; Du, Z.; Chen, G. Cell-surface engineering of yeasts for whole-cell biocatalysts. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2021, 44, 1003–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Ansorge-Schumacher, M.B.; Haag, R.; Wu, C. Living whole-cell catalysis in compartmentalized emulsion. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 295, 122221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Wu, Y.; Long, S.; Feng, S.; Jia, X.; Hu, Y.; Ma, M.; Liu, J.; Zeng, B. Aspergillus oryzae as a Cell Factory: Research and Applications in Industrial Production. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Ma, M.; Xin, X.; Tang, Y.; Zhao, G.; Xiao, X. Efficient acylation of gastrodin by Aspergillus oryzae whole-cells in non-aqueous media. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 16701–16712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najjar, A.; Hassan, E.A.; Zabermawi, N.; Saber, S.H.; Bajrai, L.H.; Almuhayawi, M.S.; Abujamel, T.S.; Almasaudi, S.B.; Azhar, L.E.; Moulay, M.; et al. Optimizing the catalytic activities of methanol and thermotolerant Kocuria flava lipases for biodiesel production from cooking oil wastes. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Li, X.; Xin, X.; Xu, H.; Mo, L.; Yu, Y.; Zhao, G. Comparative transcriptomics to reveal the mechanism of enhanced catalytic activities of Aspergillus niger whole-cells cultured with different inducers in hydrolysis of citrus flavonoids. Food Res. Int. 2022, 156, 111344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Hao, L.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; Zhao, G. Comparative transcriptomics reveals the mechanism of antibacterial activity of fruit-derived dihydrochalcone flavonoids against Porphyromonas gingivalis. Food Funct. 2024, 15, 9734–9749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, L.; Fang, Z.; Lee, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W.; Li, H.; Lu, W. Integration of Transcriptome and Metabolome Reveals the Genes and Metabolites Involved in Bifidobacterium bifidum Biofilm Formation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terabayashi, T.; Germino, G.G.; Menezes, L.F. Pathway identification through transcriptome analysis. Cell. Signal. 2020, 74, 109701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhao, X.; Li, R.; Yang, H. Integrated metabolomics and transcriptomics reveal the adaptive responses of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium to thyme and cinnamon oils. Food Res. Int. 2022, 157, 111241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elhussiny, N.I.; El-Refai, H.A.; Mohamed, S.S.; Shetaia, Y.M.; Amin, H.A.; Klöck, G. Aspergillus flavus biomass catalytic lipid modification: Optimization of cultivation conditions. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2024, 14, 22633–22645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabiszewska, A.; Zieniuk, B.; Jasińska, K.; Nowak, D.; Sasal, K.; Kobus, J.; Jankiewicz, U. Extracellular Lipases of Yarrowia lipolytica Yeast in Media Containing Plant Oils—Studies Supported by the Design of Experiment Methodology. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipiczki, G.; Micevic, S.S.; Kohari-Farkas, C.; Nagy, E.S.; Nguyen, Q.D.; Gere, A.; Bujna, E. Effects of Olive Oil and Tween 80 on Production of Lipase by Yarrowia Yeast Strains. Processes 2024, 12, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, A.; Longo, M.A.; Deive, F.J.; Álvarez, M.S.; Rodríguez, A. Dual role of a natural deep eutectic solvent as lipase extractant and transesterification enhancer. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 346, 131095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.; Tanaka, M.; Konno, Y.; Ichikawa, T.; Ichinose, S.; Hasegawa-Shiro, S.; Shintani, T.; Gomi, K. Distinct mechanism of activation of two transcription factors, AmyR and MalR, involved in amylolytic enzyme production in Aspergillus oryzae. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 1805–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhuang, W.; Rabiee, H.; Zhu, C.; Deng, J.; Ge, L.; Ying, H. Amphiphilic Nanointerface: Inducing the Interfacial Activation for Lipase. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 39622–39636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Jiang, T.; Wu, Y.; Cui, L.; Qin, S.; He, B. Elucidation of lid open and orientation of lipase activated in interfacial activation by amphiphilic environment. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 119, 1211–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, C.; Zhu, X.; Peng, Q.; Ma, Q. Catalytic site flexibility facilitates the substrate and catalytic promiscuity of Vibrio dual lipase/transferase. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wu, X.; Wang, Q.; Li, Z.; Liu, X.; Sheng, X.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, M.; Xu, J.; Feng, X.; et al. CD73-Adenosine A1R Axis Regulates the Activation and Apoptosis of Hepatic Stellate Cells Through the PLC-IP3-Ca2+/DAG-PKC Signaling Pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 922885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katti, S.S.; Krieger, I.V.; Ann, J.; Lee, J.; Sacchettini, J.C.; Igumenova, T.I. Structural anatomy of Protein Kinase C C1 domain interactions with diacylglycerol and other agonists. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Shumate, L.T.; Matthias, J.; Aydin, C.; Wein, M.N.; Spatz, J.M.; Goetz, R.; Mohammadi, M.; Plagge, A.; Divieti Pajevic, P.; et al. A G protein-coupled, IP3/protein kinase C pathway controlling the synthesis of phosphaturic hormone FGF23. JCI Insight 2019, 4, e125007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample Name | Concentration (ng/μL) | Volume (μL) | Amount (μg) | OD260/280 | OD260/230 | RIN | 28S/18S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S_1 | 730 | 40 | 29.2 | 2.14 | 2.38 | 7.1 | 1.7 |

| S_2 | 2863 | 40 | 114.52 | 0.98 | 1.12 | 5.7 | 2.2 |

| S_3 | 1617 | 40 | 64.68 | 1.99 | 2.27 | 6.8 | 1.9 |

| G_1 | 2632 | 40 | 105.28 | 1.45 | 1.66 | 6.6 | 3.1 |

| G_2 | 2177 | 40 | 87.08 | 1.82 | 2.08 | 6.5 | 2.3 |

| G_3 | 3024 | 20 | 60.48 | 1.51 | 1.74 | 6.8 | 1.8 |

| Sample | Total Number | Total Length (bp) | Mean Length (bp) | N50 (bp) | N70 (bp) | N90 (bp) | GC(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G_1 | 33,926 | 78,394,507 | 2310 | 3534 | 2457 | 1302 | 49.59 |

| G_2 | 40,428 | 115,325,163 | 2852 | 4463 | 3062 | 1642 | 49.52 |

| G_3 | 31,948 | 70,971,079 | 2221 | 3231 | 2276 | 1280 | 49.67 |

| S_1 | 23,499 | 43,553,160 | 1853 | 2818 | 1931 | 1018 | 49.93 |

| S_2 | 33,692 | 99,384,502 | 2949 | 5255 | 3217 | 1529 | 49.38 |

| S_3 | 22,370 | 40,272,927 | 1800 | 2790 | 1912 | 970 | 49.96 |

| All-Unigene | 47,718 | 179,560,378 | 3762 | 5559 | 3804 | 2067 | 49.42 |

| Database | Number of Annotated Unigenes | Annotation Ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|

| NR | 44142 | 92.51 |

| NT | 47190 | 98.89 |

| Swissprot | 34166 | 71.60 |

| KEGG | 35860 | 75.15 |

| KOG | 30809 | 64.56 |

| Pfam | 37455 | 78.49 |

| GO | 28719 | 60.18 |

| Gene ID | NR Annotation |

|---|---|

| CL117.Contig30_All | unnamed protein product [Aspergillus oryzae RIB40] |

| CL117.Contig6_All | unnamed protein product [Aspergillus oryzae RIB40] |

| CL117.Contig36_All | PLD-like domain protein [Aspergillus parasiticus SU-1] |

| CL117.Contig54_All | PLD-like domain protein [Aspergillus parasiticus SU-1] |

| CL117.Contig7_All | HLH transcription factor (GlcD gamma), putative [Aspergillus oryzae 3.042] |

| CL117.Contig12_All | phospholipase PldA [Aspergillus oryzae RIB40] |

| CL117.Contig50_All | phospholipase PldA [Aspergillus oryzae RIB40] |

| CL2062.Contig2_All | phospholipase D1 [Aspergillus oryzae 3.042] > KDE78745.1 phospholipase D1 [Aspergillus oryzae 100-8] |

| CL2062.Contig8_All | phospholipase D1 [Aspergillus oryzae 3.042] > KDE78745.1 phospholipase D1 [Aspergillus oryzae 100-8] |

| CL4019.Contig2_All | lysophospholipase 1 [Aspergillus flavus AF70] |

| CL2271.Contig7_All | hypothetical protein AN7792.2 [Aspergillus nidulans FGSC A4] |

| CL24.Contig17_All | triacylglycerol lipase [Aspergillus bombycis] |

| CL24.Contig40_All | triacylglycerol lipase [Aspergillus oryzae RIB40] |

| CL24.Contig67_All | triacylglycerol lipase [Aspergillus bombycis] |

| Unigene4417_All | lipase atg15 [Aspergillus oryzae RIB40] |

| CL542.Contig1_All | lipase/esterase, putative [Aspergillus flavus NRRL3357] |

| CL542.Contig4_All | lipase/esterase, putative [Aspergillus flavus NRRL3357] |

| CL726.Contig10_All | putative non-hemolytic phospholipase C precursor [Aspergillus flavus AF70] |

| CL726.Contig9_All | non-hemolytic phospholipase C precursor [Aspergillus oryzae RIB40] |

| CL726.Contig1_All | phospholipase C [Aspergillus oryzae 3.042] > KDE81680.1 phospholipase C [Aspergillus oryzae 100-8] |

| CL972.Contig11_All | phospholipase C [Aspergillus oryzae 3.042] |

| CL972.Contig7_All | phospholipase C [Aspergillus oryzae 3.042] |

| CL195.Contig2_All | alpha/beta hydrolase, putative [Aspergillus flavus NRRL3357] |

| CL31.Contig14_All | phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C, putative [Aspergillus oryzae 3.042] |

| CL31.Contig7_All | phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C, putative [Aspergillus oryzae 3.042] |

| CL31.Contig8_All | phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C, putative [Aspergillus oryzae 3.042] |

| Gene ID | NR Annotation |

|---|---|

| CL24.Contig17_All | triacylglycerol lipase [Aspergillus bombycis] |

| CL24.Contig40_All | triacylglycerol lipase [Aspergillus oryzae RIB40] |

| CL24.Contig67_All | triacylglycerol lipase [Aspergillus bombycis] |

| Unigene4417_All | lipase atg15 [Aspergillus oryzae RIB40] |

| Pathway Name | Pathway ID | Term Candidate Gene Num |

|---|---|---|

| Glycerophospholipid metabolism | ko00564 | 18 |

| Ether lipid metabolism | ko00565 | 14 |

| Inositol phosphate metabolism | ko00562 | 8 |

| Endocytosis | ko04144 | 9 |

| Glycerolipid metabolism | ko00561 | 5 |

| Phosphatidylinositol signaling system | ko04070 | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, D.; Ma, M.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; Zhao, G. Comparative Transcriptomics Reveals the Molecular Basis for Inducer-Dependent Efficiency in Gastrodin Propionylation by Aspergillus oryzae Whole-Cell Biocatalyst. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1695. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121695

Wu D, Ma M, Liu X, Li X, Zhao G. Comparative Transcriptomics Reveals the Molecular Basis for Inducer-Dependent Efficiency in Gastrodin Propionylation by Aspergillus oryzae Whole-Cell Biocatalyst. Biomolecules. 2025; 15(12):1695. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121695

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Desheng, Maohua Ma, Xiaohan Liu, Xiaofeng Li, and Guanglei Zhao. 2025. "Comparative Transcriptomics Reveals the Molecular Basis for Inducer-Dependent Efficiency in Gastrodin Propionylation by Aspergillus oryzae Whole-Cell Biocatalyst" Biomolecules 15, no. 12: 1695. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121695

APA StyleWu, D., Ma, M., Liu, X., Li, X., & Zhao, G. (2025). Comparative Transcriptomics Reveals the Molecular Basis for Inducer-Dependent Efficiency in Gastrodin Propionylation by Aspergillus oryzae Whole-Cell Biocatalyst. Biomolecules, 15(12), 1695. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121695