Vitamin B12 Protects Against Early Diabetic Kidney Injury and Alters Clock Gene Expression in Mice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Study

2.2. Systolic Blood Pressure (SBP) Analysis

2.3. Sample Collection

2.4. Plasma Biological Parameters

2.5. Histology and Immunofluorescence

2.6. RNA Sequencing and Data Analysis

2.7. Quantitative Reverse-Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

2.8. Cell Culture and Synchronization

2.9. Protein Extraction

2.10. Western Blott Assay

3. Results

3.1. B12 Treatment Improves Multiple Metabolic and Renal Function Parameters in Diabetic Mice

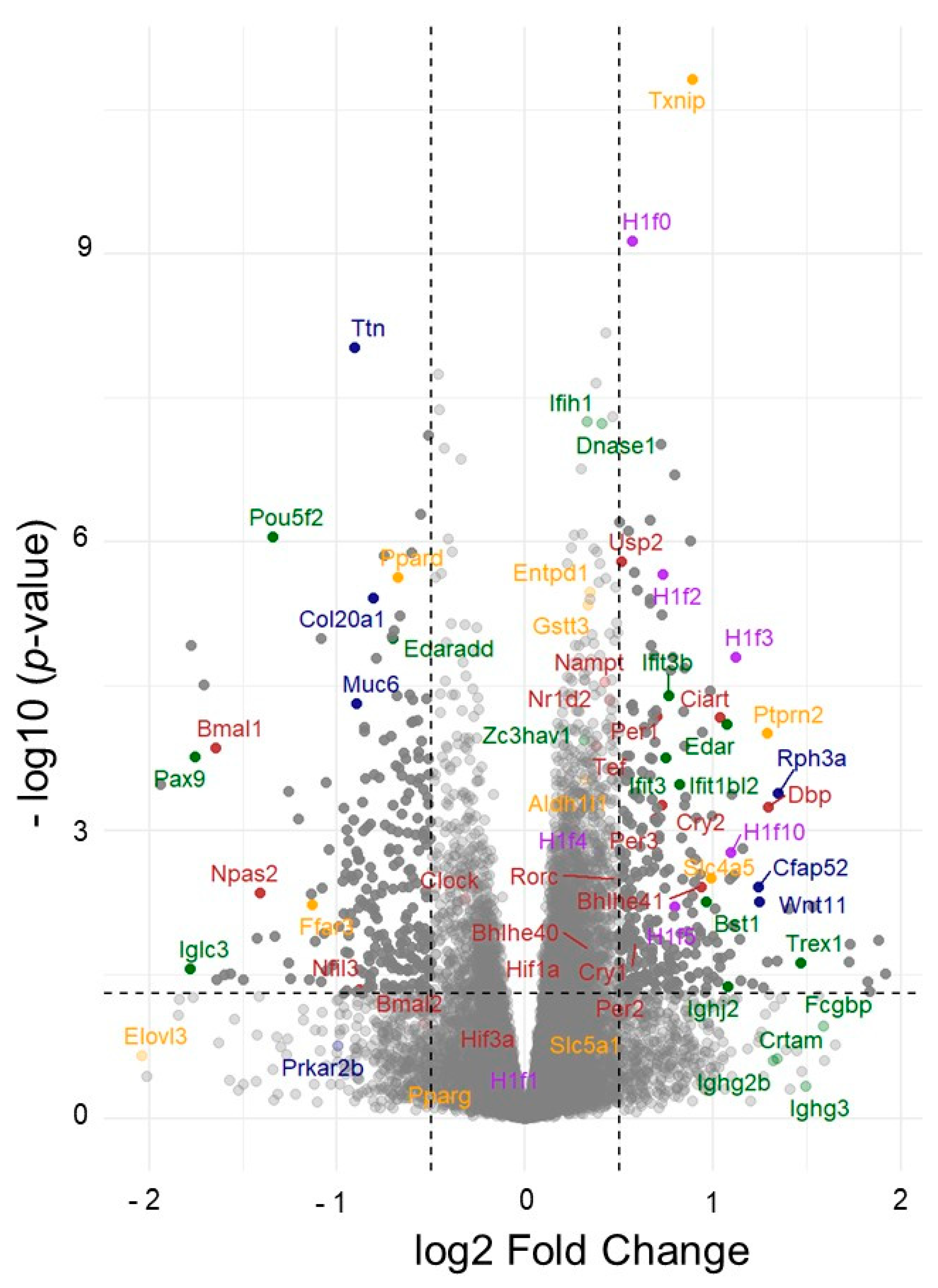

3.2. Global Gene Expression Analyses Revealed Pathways Through Which B12 Mitigates DN Development

3.2.1. Immune-Inflammatory Pathways

3.2.2. Solute Carrier Expression and Water Handling

3.2.3. Redox Regulation

3.2.4. Metabolic and Structural Pathways

3.2.5. Vitamin B12 Reprograms Circadian Clock Networks and Chromatin Architecture in the Diabetic Kidney

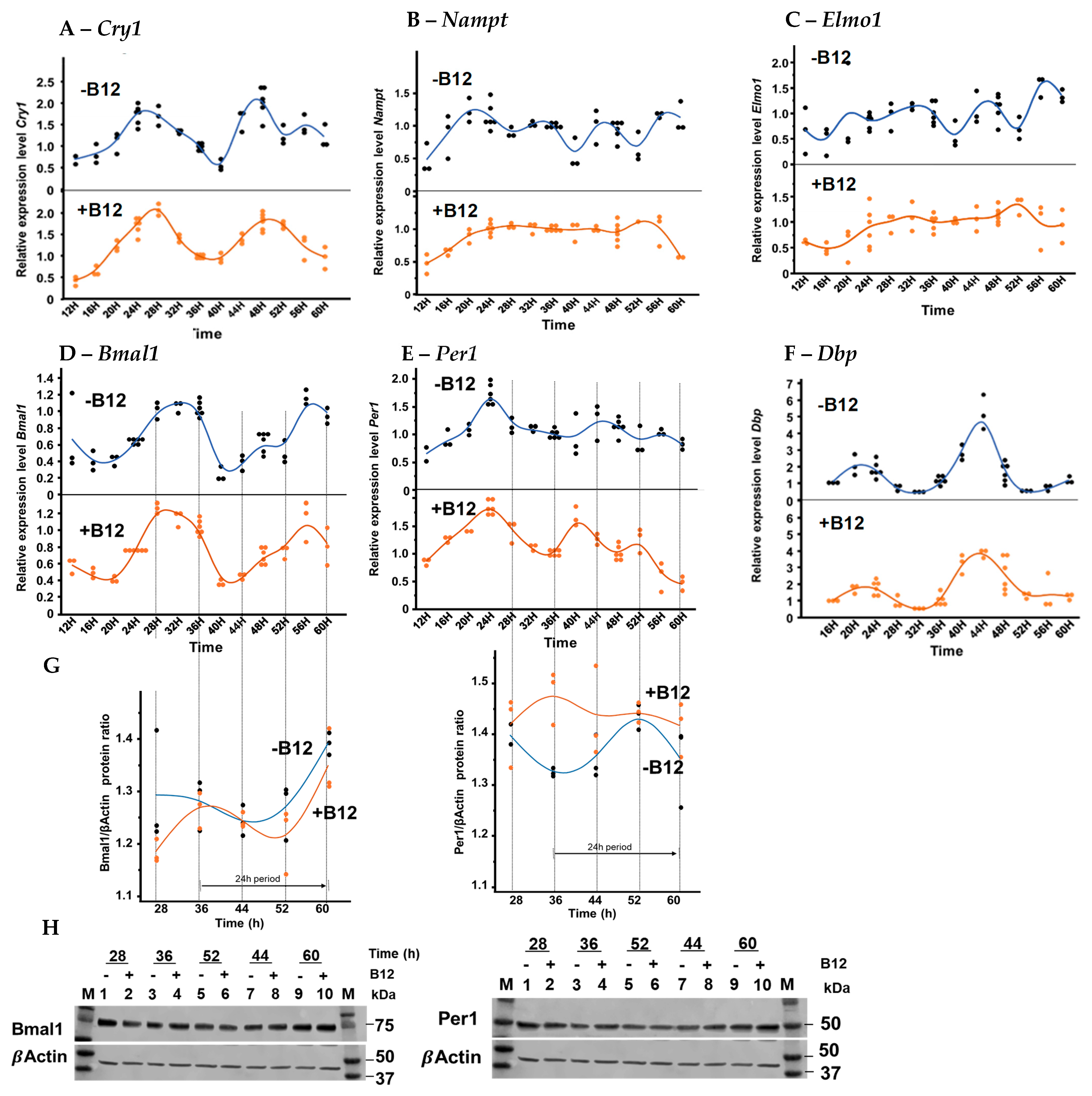

3.3. Circadian Gene Expression of Proximal Tubular BU.MPT Cells

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| B12 | Vitamin B12 |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| Elmo1 | Engulfment and Cell Motility 1 |

| SNPs | Single nucleotide polymorphisms |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| TGFβ1 | Transforming growth factor β1 |

| SBP | Systolic blood pressure |

| GEO | NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative Reverse-transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| PAS | Periodic Acid–Schiff |

| TNF | Tumor necrosis factor |

| ECM | extra cellular matrix |

| AGEs | Advanced glycation end-products |

| BP | Blood pressure |

| SLC | Solute carrier |

References

- Roth, J.R.; Lawrence, J.G.; Bobik, T.A. COBALAMIN (COENZYME B12): Synthesis and Biological Significance. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1996, 50, 137–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doets, E.L.; van Wijngaarden, J.P.; Szczecinska, A.; Dullemeijer, C.; Souverein, O.W.; Dhonukshe-Rutten, R.A.; Cavelaars, A.E.; van ‘t Veer, P.; Brzozowska, A.; de Groot, L.C. Vitamin B12 intake and status and cognitive function in elderly people. Epidemiol. Rev. 2013, 35, 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suarez-Moreira, E.; Yun, J.; Birch, C.S.; Williams, J.H.H.; McCaddon, A.; Brasch, N.E. Vitamin B12 and Redox Homeostasis: Cob(II)alamin Reacts with Superoxide at Rates Approaching Superoxide Dismutase (SOD). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 15078–15079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victor, P.; Umapathy, D.; George, L.; Juttada, U.; Ganesh, G.V.; Amin, K.N.; Viswanathan, V.; Ramkumar, K.M. Crosstalk between endoplasmic reticulum stress and oxidative stress in the progression of diabetic nephropathy. Cell Stress Chaperones 2021, 26, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpe, C.M.O.; Villar-Delfino, P.H.; Dos Anjos, P.M.F.; Nogueira-Machado, J.A. Cellular death, reactive oxygen species (ROS) and diabetic complications. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hathaway, C.K.; Chang, A.S.; Grant, R.; Kim, H.S.; Madden, V.J.; Bagnell, C.R., Jr.; Jennette, J.C.; Smithies, O.; Kakoki, M. High Elmo1 expression aggravates and low Elmo1 expression prevents diabetic nephropathy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 2218–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakoki, M.; Bahnson, E.M.; Hagaman, J.R.; Siletzky, R.M.; Grant, R.; Kayashima, Y.; Li, F.; Lee, E.Y.; Sun, M.T.; Taylor, J.M.; et al. Engulfment and cell motility protein 1 potentiates diabetic cardiomyopathy via Rac-dependent and Rac-independent ROS production. JCI Insight 2019, 4, e127660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodhini, D.; Chidambaram, M.; Liju, S.; Revathi, B.; Laasya, D.; Sathish, N.; Kanthimathi, S.; Ghosh, S.; Anjana, R.M.; Mohan, V.; et al. Association of rs11643718 SLC12A3 and rs741301 ELMO1 Variants with Diabetic Nephropathy in South Indian Population. Ann. Hum. Genet. 2016, 80, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leak, T.S.; Perlegas, P.S.; Smith, S.G.; Keene, K.L.; Hicks, P.J.; Langefeld, C.D.; Mychaleckyj, J.C.; Rich, S.S.; Kirk, J.K.; Freedman, B.I.; et al. Variants in intron 13 of the ELMO1 gene are associated with diabetic nephropathy in African Americans. Ann. Hum. Genet. 2009, 73, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakoki, M.; Ramanathan, P.V.; Hagaman, J.R.; Grant, R.; Wilder, J.C.; Taylor, J.M.; Charles Jennette, J.; Smithies, O.; Maeda-Smithies, N. Cyanocobalamin prevents cardiomyopathy in type 1 diabetes by modulating oxidative stress and DNMT-SOCS1/3-IGF-1 signaling. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Bahnson, E.M.; Wilder, J.; Siletzky, R.; Hagaman, J.; Nickekeit, V.; Hiller, S.; Ayesha, A.; Feng, L.; Levine, J.S.; et al. Oral high dose vitamin B12 decreases renal superoxide and post-ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. Redox Biol. 2020, 32, 101504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parravano, M.; Scarinci, F.; Parisi, V.; Giorno, P.; Giannini, D.; Oddone, F.; Varano, M. Citicoline and Vitamin B12 Eye Drops in Type 1 Diabetes: Results of a 3-year Pilot Study Evaluating Morpho-Functional Retinal Changes. Adv. Ther. 2020, 37, 1646–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izumi, T.; Yokota-Hashimoto, H.; Zhao, S.; Wang, J.; Halban, P.H.; Takeuchi, T. Dominant Negative Pathogenesis by Mutant Proinsulin in the Akita Diabetic Mouse. Diabetes 2003, 52, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, N.; Taylor, L.S.; Nassar-Guifarro, M.; Monawar, M.S.; Dunn, S.M.; Devanney, N.A.; Li, F.; Johnson, L.A.; Kayashima, Y. Genomic and cellular context-dependent expression of the human ELMO1 gene transcript variants. Gene 2025, 954, 149438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujicic, S.; Feng, L.; Antoni, A.; Rauch, J.; Levine, J.S. Identification of Intracellular Signaling Events Induced in Viable Cells by Interaction with Neighboring Cells Undergoing Apoptotic Cell Death. J. Vis. Exp. 2016, e54980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Chu, L.; Zhou, X.; Xu, T.; Shen, Q.; Li, T.; Wu, Y. Vitamin B12-Induced Autophagy Alleviates High Glucose-Mediated Apoptosis of Islet beta Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Sun, G.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, R. Involvement of the NF-kappaB signaling pathway in the renoprotective effects of isorhamnetin in a type 2 diabetic rat model. Biomed. Rep. 2016, 4, 628–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Deng, X.; Jia, J.; Wang, D.; Yuan, G. Ectodysplasin A/Ectodysplasin A Receptor System and Their Roles in Multiple Diseases. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 788411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, J.; Kubota, K.; Murakam, H.; Sawamura, M.; Matsushima, T.; Tamura, T.; Saitoh, T.; Kurabayshi, H.; Naruse, T. Immunomodulation by vitamin B12: Augmentation of CD8þ T lymphocytes and natural killer (NK) cell activity in vitamin B12-deficient patients by methyl-B12 treatment. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1999, 116, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoenig, M.P.; Brooks, C.R.; Hoorn, E.J.; Hall, A.M. Biology of the proximal tubule in body homeostasis and kidney disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2025, 40, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thielen, L.; Shalev, A. Diabetes pathogenic mechanisms and potential new therapies based upon a novel target called TXNIP. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2018, 25, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassandra, B.C.-F.; Bryan, G.H.-H.; Gemma Murguía, H.; Edgar, O.R.-M.; Juan, J.S.-C.; Brissia, L. The impact of diabetes on spermatogenesis. GSC Adv. Res. Rev. 2024, 21, 040–046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, I.I.; Xu, Q.; Naillat, F.; Ali, N.; Miinalainen, I.; Samoylenko, A.; Vainio, S.J. Impairment of Wnt11 function leads to kidney tubular abnormalities and secondary glomerular cystogenesis. BMC Dev. Biol. 2016, 16, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramsey, K.M.; Yoshino, J.; Brace, C.S.; Abrassart, D.; Kobayashi, Y.; Marcheva, B.; Hong, H.K.; Chong, J.L.; Buhr, E.D.; Lee, C.; et al. Circadian Clock Feedback Cycle Through NAMPT-Mediated NAD+ Biosynthesis. Science 2009, 324, 651–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Xie, L.; Lu, W.; Yu, X.; Dong, H.; Ma, Y.; Kong, R. Hyperactivation of p53 contributes to mitotic catastrophe in podocytes through regulation of the Wee1/CDK1/cyclin B1 axis. Ren. Fail. 2024, 46, 2365408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farshadi, E.; van der Horst, G.T.J.; Chaves, I. Molecular Links between the Circadian Clock and the Cell Cycle. J. Mol. Biol. 2020, 432, 3515–3524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Liao, R.; Liu, C.; Liu, S.; Huang, H.; Liu, J.; Jin, T.; Guo, H.; Zheng, Z.; Xia, M.; et al. Epigenetic regulation of TXNIP-mediated oxidative stress and NLRP3 inflammasome activation contributes to SAHH inhibition-aggravated diabetic nephropathy. Redox Biol. 2021, 45, 102033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojilkovic, S.S.; Sokanovic, S.J.; Constantin, S. What is known and unknown about the role of neuroendocrine genes Ptprn and Ptprn2. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1531723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, D.K.; Shrestha, S.; Lillycrop, K.A.; Joglekar, C.V.; Pan, H.; Holbrook, J.D.; Fall, C.H.D.; Yajnik, C.S.; Chandak, G.R. Vitamin B12supplementation influences methylation of genes associated with Type 2 diabetes and its intermediate traits. Epigenomics 2017, 10, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, I.A.; Mehler, M.F. Epigenetics of Sleep and Chronobiology. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2014, 14, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stow, L.R.; Gumz, M.L. The circadian clock in the kidney. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2011, 22, 598–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Lin, Y.; Gao, L.; Yang, Z.; Lin, J.; Ren, S.; Li, F.; Chen, J.; Wang, Z.; Dong, Z.; et al. PPAR-gamma integrates obesity and adipocyte clock through epigenetic regulation of Bmal1. Theranostics 2022, 12, 1589–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oda, M.; Koyanagi, S.; Tsurudome, Y.; Kanemitsu, T.; Matsunaga, N.; Ohdo, S. Renal circadian clock regulates the dosing-time dependency of cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity in mice. Mol. Pharmacol. 2014, 85, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J.; Diaz, A.N.; Gumz, M.L. Clock genes in hypertension: Novel insights from rodent models. Blood Press. Monit. 2014, 19, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crislip, G.R.; Costello, H.M.; Juffre, A.; Cheng, K.Y.; Lynch, I.J.; Johnston, J.G.; Drucker, C.B.; Bratanatawira, P.; Agarwal, A.; Mendez, V.M.; et al. Male kidney-specific BMAL1 knockout mice are protected from K(+)-deficient, high-salt diet-induced blood pressure increases. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2023, 325, F656–F668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoads, D.B.; Rosenbaum, D.H.; Unsal, H.; Isselbacher, K.J.; Levitsky, L.L. Circadian periodicity of intestinal Na+/glucose cotransporter 1 mRNA levels is transcriptionally regulated. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 9510–9516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakahata, Y.; Sahar, S.; Astarita, G.; Kaluzova, M.; Sassone-Corsi, P. Circadian control of the NAD+ salvage pathway by CLOCK-SIRT1. Science 2009, 324, 654–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Qu, H.; Wang, Y. Methylation of HIF3A promoter CpG islands contributes to insulin resistance in gestational diabetes mellitus. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 2019, 7, e00583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, S.; Kruger, J.; Maierhofer, A.; Bottcher, Y.; Kloting, N.; El Hajj, N.; Schleinitz, D.; Schon, M.R.; Dietrich, A.; Fasshauer, M.; et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor 3A gene expression and methylation in adipose tissue is related to adipose tissue dysfunction. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 27969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Fan, Y. Role of H1 linker histones in mammalian development and stem cell differentiation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Gene Regul. Mech. 2016, 1859, 496–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prendergast, L.; Reinberg, D. The missing linker: Emerging trends for H1 variant-specific functions. Genes Dev. 2021, 35, 40–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas-Pena, M.; Rebollo, E.; Jordan, A. Imaging analysis of six human histone H1 variants reveals universal enrichment of H1.2, H1.3, and H1.5 at the nuclear periphery and nucleolar H1X presence. eLife 2024, 12, RP91306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, J.; Bai, W.; Li, K. Histone Modifications: Potential Therapeutic Targets for Diabetic Retinopathy. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Zhang, L.; He, Y.; Zhou, T.; Cheng, X.; Huang, W.; Xu, Y. Novel histone post-translational modifications in diabetes and complications of diabetes: The underlying mechanisms and implications. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 156, 113984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, O.S.; Sant, K.E.; Dolinoy, D.C. Nutrition and epigenetics: An interplay of dietary methyl donors, one-carbon metabolism and DNA methylation. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2012, 23, 853–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.C.; Guarente, L. SIRT1 mediates central circadian control in the SCN by a mechanism that decays with aging. Cell 2013, 153, 1448–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellet, M.M.; Sassone-Corsi, P. Mammalian circadian clock and metabolism—The epigenetic link. J. Cell Sci. 2010, 123, 3837–3848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, G.; Kroger, M.; Meier-Ewert, K. Effects of Vitamin B12 on Performance and Circadian Rhythm in Normal Subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology 1996, 15, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandholm, N.; Cole, J.B.; Nair, V.; Sheng, X.; Liu, H.; Ahlqvist, E.; van Zuydam, N.; Dahlstrom, E.H.; Fermin, D.; Smyth, L.J.; et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis and omics integration I dentifies novel genes associated with diabetic kidney disease. Diabetologia 2022, 65, 1495–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letonja, J.; Nussdorfer, P.; Petrovic, D. Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms in the Thioredoxin Antioxidant System and Their Association with Diabetic Nephropathy in Slovenian Patients with Type 2 Diabetes—A Preliminary Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizarro, A.; Hayer, K.; Lahens, N.F.; Hogenesch, J.B. CircaDB: A database of mammalian circadian gene expression profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D1009–D1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costello, H.M.; Johnston, J.G.; Juffre, A.; Crislip, G.R.; Gumz, M.L. Circadian clocks of the kidney: Function, mechanism, and regulation. Physiol. Rev. 2022, 102, 1669–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wariyapperuma Appuhamillage, N.M.W.; Deshmukh, A.A.; Moser, R.L.; Ma, Q.; Zhou, J.; Li, F.; Kayashima, Y.; Maeda, N. Vitamin B12 Protects Against Early Diabetic Kidney Injury and Alters Clock Gene Expression in Mice. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1689. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121689

Wariyapperuma Appuhamillage NMW, Deshmukh AA, Moser RL, Ma Q, Zhou J, Li F, Kayashima Y, Maeda N. Vitamin B12 Protects Against Early Diabetic Kidney Injury and Alters Clock Gene Expression in Mice. Biomolecules. 2025; 15(12):1689. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121689

Chicago/Turabian StyleWariyapperuma Appuhamillage, Niroshani M. W., Anshulika A. Deshmukh, Rachel L. Moser, Qing Ma, Jiayi Zhou, Feng Li, Yukako Kayashima, and Nobuyo Maeda. 2025. "Vitamin B12 Protects Against Early Diabetic Kidney Injury and Alters Clock Gene Expression in Mice" Biomolecules 15, no. 12: 1689. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121689

APA StyleWariyapperuma Appuhamillage, N. M. W., Deshmukh, A. A., Moser, R. L., Ma, Q., Zhou, J., Li, F., Kayashima, Y., & Maeda, N. (2025). Vitamin B12 Protects Against Early Diabetic Kidney Injury and Alters Clock Gene Expression in Mice. Biomolecules, 15(12), 1689. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121689