Proximity Ligation Assay: From a Foundational Principle to a Versatile Platform for Molecular and Translational Research

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Proximity Ligation Assay

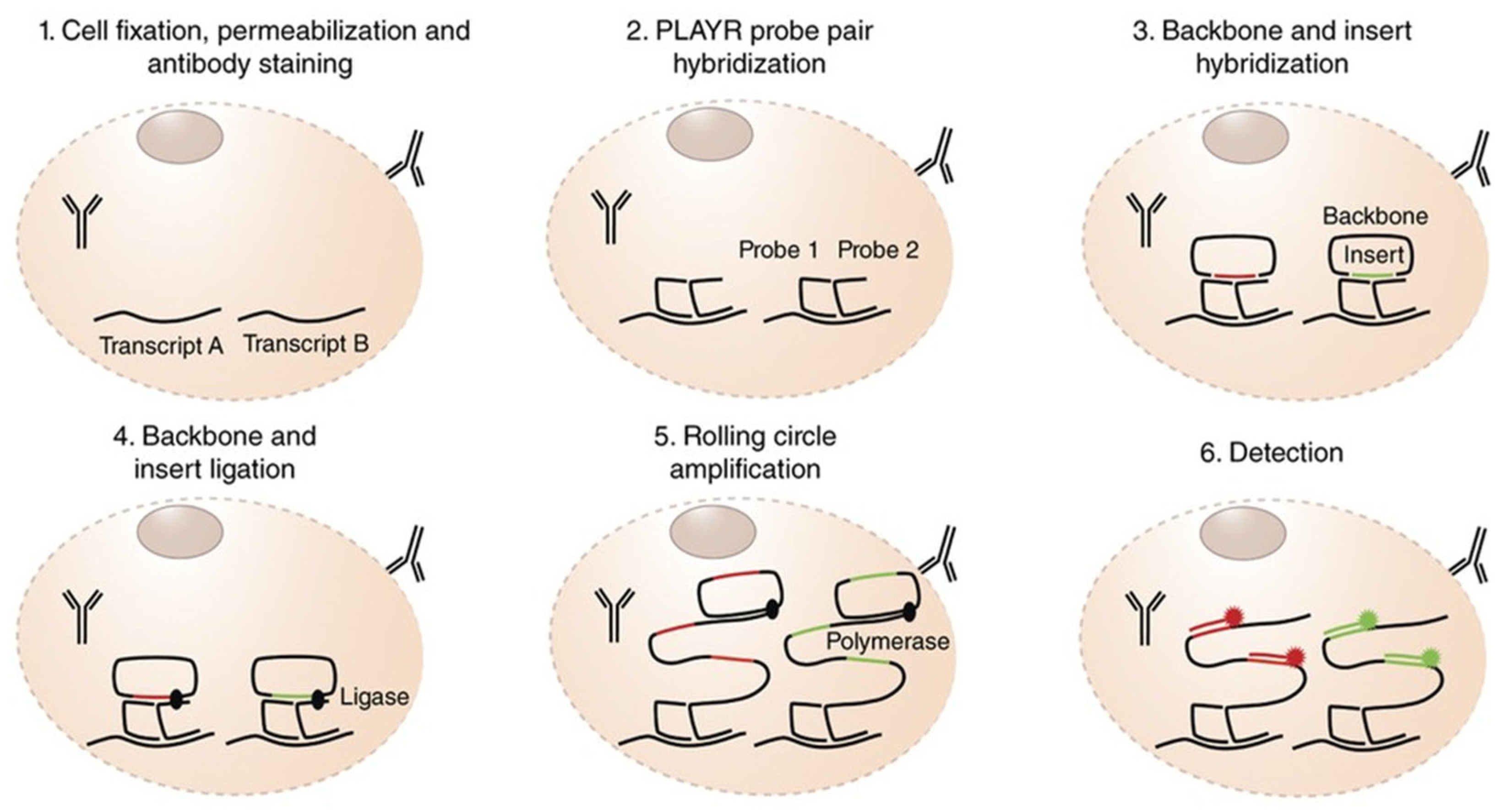

2.1. The Principle of PLA

2.2. The Development History of PLA

2.3. The Classification of PLA

2.4. Comparison Between isPLA and Key PPI Methods

3. Foundational Applications of isPLA in Cellular Biology

3.1. Mapping PPI Networks In Situ

3.2. Elucidating PTMs and Signaling Cascades

3.3. Investigating Subcellular Architecture and Organelle Crosstalk

3.4. Probing Dynamic Cellular Processes

4. Translational and Clinical Applications of PLA

4.1. Dissecting Cancer Pathways and Identifying Biomarkers

4.2. Unraveling Protein Pathologies in Neuroscience

4.3. Pathogen Detection and Infectious Disease Diagnostics

5. Technological Evolution and Advanced PLA Platforms

5.1. Enhancing Specificity and Sensitivity

5.2. Expanding Throughput

5.3. Integrating Advanced Readouts

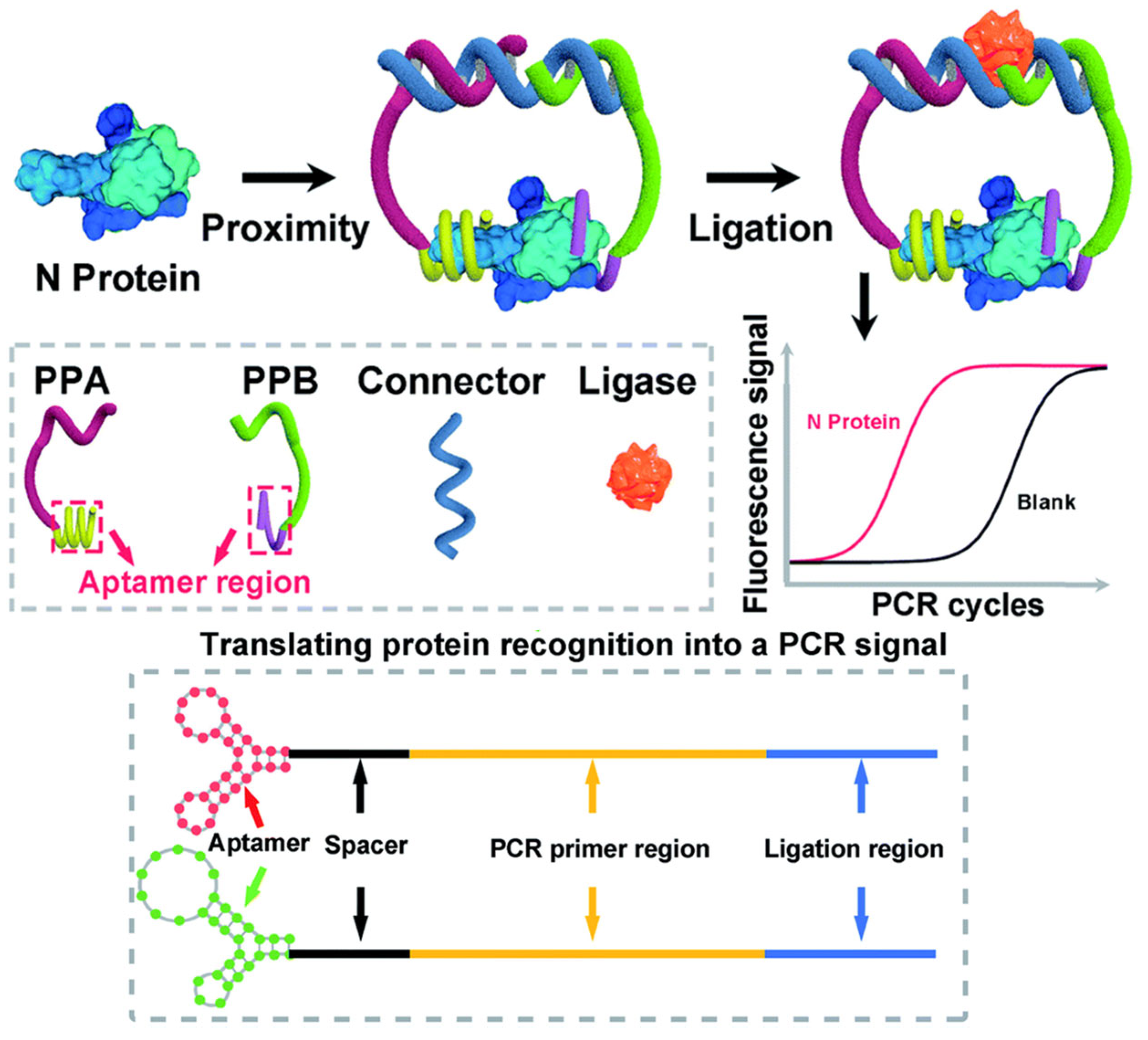

5.4. Beyond Antibodies

6. Perspectives and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Alzheimer’s Disease |

| AP-MS | Affinity Purification-Mass Spectrometry |

| Aβ | Amyloid-β |

| BiFC | Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation |

| CDKs | Cyclin-Dependent Kinases |

| CEA | Carcinoembryonic Antigen |

| CHA | Catalyzed Hairpin Assembly |

| Co-IP | Co-Immunoprecipitation |

| ECPLA | Electrochemical Proximity Ligation Assay |

| ELISA | Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| ER | Endoplasmic Reticulum |

| FRET | Förster Resonance Energy Transfer |

| HER2 | Human Epidermal growth factor Receptor 2 |

| HIV | Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| HRP2 | Histidine-Rich Protein 2 |

| IF | Immunofluorescence |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| isPLA | In situ Proximity Ligation Assay |

| LOD | Limit of Detection |

| MCS | Membrane Contact Sites |

| NAATs | Nucleic Acid Amplification Tests |

| NGS | Next-Generation Sequencing |

| NPC | Nuclear Pore Complex |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| PD | Parkinson’s Disease |

| PDGF | Platelet-Derived Growth Factor |

| PdNPs | Palladium Nanoparticles |

| PEA | Proximity Extension Assay |

| PLA | Proximity Ligation Assay |

| PPIs | Protein–Protein Interactions |

| PTMs | Post-Translational Modifications |

| RCA | Rolling Circle Amplification |

| RDTs | Rapid Diagnostic Tests |

| RTKs | Receptor Tyrosine Kinases |

| Y2H | Yeast two-Hybrid |

References

- Barabasi, A.L.; Gulbahce, N.; Loscalzo, J. Network medicine: A network-based approach to human disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011, 12, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammed, H.; Carroll, J.S. Approaches for assessing and discovering protein interactions in cancer. Mol. Cancer Res. 2013, 11, 1295–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Citovsky, V.; Gafni, Y.; Tzfira, T. Localizing protein-protein interactions by bimolecular fluorescence complementation in planta. Methods 2008, 45, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Miernyk, J.A.; Thelen, J.J. Biochemical approaches for discovering protein-protein interactions. Plant J. 2008, 53, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalonde, S.; Ehrhardt, D.W.; Loque, D.; Chen, J.; Rhee, S.Y.; Frommer, W.B. Molecular and cellular approaches for the detection of protein-protein interactions: Latest techniques and current limitations. Plant J. 2008, 53, 610–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.W.; Kyung, T.; Yoo, J.; Kim, T.; Chung, C.; Ryu, J.Y.; Lee, H.; Park, K.; Lee, S.; Jones, W.D.; et al. Real-time single-molecule co-immunoprecipitation analyses reveal cancer-specific Ras signalling dynamics. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strotmann, V.I.; Stahl, Y. Visualization of in vivo protein-protein interactions in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 3866–3880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, H.; Picard, L.P.; Schonegge, A.M.; Bouvier, M. Bioluminescence resonance energy transfer-based imaging of protein-protein interactions in living cells. Nat. Protoc. 2019, 14, 1084–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajapakse, H.E.; Gahlaut, N.; Mohandessi, S.; Yu, D.; Turner, J.R.; Miller, L.W. Time-resolved luminescence resonance energy transfer imaging of protein-protein interactions in living cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 13582–13587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinthal, D.; Tzfira, T. Imaging protein-protein interactions in plant cells by bimolecular fluorescence complementation assay. Trends Plant Sci. 2009, 14, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, S.; Wallmeroth, N.; Berendzen, K.W.; Grefen, C. Techniques for the Analysis of Protein-Protein Interactions in Vivo. Plant Physiol. 2016, 171, 727–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foddai, A.C.; Grant, I.R. Methods for detection of viable foodborne pathogens: Current state-of-art and future prospects. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 4281–4288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, P.; Liu, C.; Li, Z.; Xue, Z.; Mao, P.; Hu, J.; Xu, F.; Yao, C.; You, M. Emerging ELISA derived technologies for in vitro diagnostics. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2022, 152, 116605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, S.; Emre, E.; Ugur, K.; Aydin, M.A.; Sahin, İ.; Cinar, V.; Akbulut, T. An overview of ELISA: A review and update on best laboratory practices for quantifying peptides and proteins in biological fluids. J. Int. Med. Res. 2025, 53, 03000605251315913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Wang, K.; Li, H.; Fan, Y.; Sun, X.; Wang, X.; Sun, H. Recent advances in electrochemical proximity ligation assay. Talanta 2023, 254, 124158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Yang, Y.; Hong, T.; Zhu, G. Proximity ligation assay: An ultrasensitive method for protein quantification and its applications in pathogen detection. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 923–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soderberg, O.; Leuchowius, K.J.; Gullberg, M.; Jarvius, M.; Weibrecht, I.; Larsson, L.G.; Landegren, U. Characterizing proteins and their interactions in cells and tissues using the in situ proximity ligation assay. Methods 2008, 45, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatloukal, B.; Kufferath, I.; Thueringer, A.; Landegren, U.; Zatloukal, K.; Haybaeck, J. Sensitivity and specificity of in situ proximity ligation for protein interaction analysis in a model of steatohepatitis with Mallory-Denk bodies. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e96690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanipour, L.; Darmanis, S.; Landegren, U.; Glimelius, B.; Pahlman, L.; Birgisson, H. Detection of biomarkers with solid-phase proximity ligation assay in patients with colorectal cancer. Transl. Oncol. 2016, 9, 251–255. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, A.D.; Liu, Y.; von Eyben, R.; Hsu, C.C.; Hu, C.; Rosati, L.M.; Parekh, A.; Ng, K.; Hacker-Prietz, A.; Zheng, L.; et al. Multiplex proximity ligation assay to Identify potential prognostic biomarkers for improved survival in locally advanced pancreatic cancer patients treated with stereotactic body radiation therapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2018, 100, 486–489. [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksson, S.; Horecka, J.; Brustugun, O.T.; Schlingemann, J.; Koong, A.C.; Tibshirani, R.; Davis, R.W. Multiplexed proximity ligation assays to profile putative plasma biomarkers relevant to pancreatic and ovarian cancer. Clin. Chem. 2008, 54, 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Wang, Y.; Li, W. PPI finder: A mining tool for human protein-protein interactions. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e4554. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, R.; Roberts, E.; Bieniarz, C. In situ detection of protein complexes and modifications by chemical ligation proximity assay. Bioconjug. Chem. 2016, 27, 1690–1696. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, Q.H.; Tao, T.; Xie, L.Q.; Lu, H.J. ELISA-PLA: A novel hybrid platform for the rapid, highly sensitive and specific quantification of proteins and post-translational modifications. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 80, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, F.M.S.; Mereiter, S.; Lonn, P.; Siart, B.; Shen, Q.; Heldin, J.; Raykova, D.; Karlsson, N.G.; Polom, K.; Roviello, F.; et al. Detection of post-translational modifications using solid-phase proximity ligation assay. New Biotechnol. 2018, 45, 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Kamali-Moghaddam, M.; Pettersson, F.E.; Wu, D.; Englund, H.; Darmanis, S.; Lord, A.; Tavoosidana, G.; Sehlin, D.; Gustafsdottir, S.; Nilsson, L.N.; et al. Sensitive detection of Abeta protofibrils by proximity ligation—Relevance for Alzheimer’s disease. BMC Neurosci. 2010, 11, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Fernandez, W.; Carvajal-Tapia, C.; Prusky, A.; Katdare, K.A.; Wang, E.; Shostak, A.; Ventura-Antunes, L.; Harmsen, H.J.; Lippmann, E.S.; Fuxe, K.; et al. Detection, visualization and quantification of protein complexes in human Alzheimer’s disease brains using proximity ligation assay. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Crum, M.; Chavan, D.; Vu, B.; Kourentzi, K.; Willson, R.C. Nanoparticle-Based Proximity Ligation Assay for Ultrasensitive, Quantitative Detection of Protein Biomarkers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 31845–31849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hmila, I.; Marnissi, B.; Kamali-Moghaddam, M.; Ghram, A. Aptamer-Assisted Proximity Ligation Assay for Sensitive Detection of Infectious Bronchitis Coronavirus. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0208122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, S.; Chafe, S.C.; Venugopal, C.; Singh, S.K. Proximity Ligation Assay. Methods Mol. Biol. 2025, 2944, 135–140. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, M.S. Proximity Ligation Assay (PLA). Methods Mol. Biol. 2022, 2422, 191–201. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsdottir, S.M.; Schallmeiner, E.; Fredriksson, S.; Gullberg, M.; Söderberg, O.; Jarvius, M.; Jarvius, J.; Howell, M.; Landegren, U. Proximity ligation assays for sensitive and specific protein analyses. Anal. Biochem. 2005, 345, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundberg, M.; Thorsen, S.B.; Assarsson, E.; Villablanca, A.; Tran, B.; Gee, N.; Knowles, M.; Nielsen, B.S.; Couto, E.G.; Martin, R. Multiplexed homogeneous proximity ligation assays for high-throughput protein biomarker research in serological material. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2011, 10, M110.004978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, S.T.; Zahn, J.M.; Horecka, J.; Kunz, P.L.; Ford, J.M.; Fisher, G.A.; Le, Q.T.; Chang, D.T.; Ji, H.; Koong, A.C. Identification of a biomarker panel using a multiplex proximity ligation assay improves accuracy of pancreatic cancer diagnosis. J. Transl. Med. 2009, 7, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soderberg, O.; Gullberg, M.; Jarvius, M.; Ridderstrale, K.; Leuchowius, K.J.; Jarvius, J.; Wester, K.; Hydbring, P.; Bahram, F.; Larsson, L.G.; et al. Direct observation of individual endogenous protein complexes in situ by proximity ligation. Nat. Methods 2006, 3, 995–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredriksson, S.; Gullberg, M.; Jarvius, J.; Olsson, C.; Pietras, K.; Gustafsdottir, S.M.; Ostman, A.; Landegren, U. Protein detection using proximity-dependent DNA ligation assays. Nat. Biotechnol. 2002, 20, 473–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullberg, M.; Gustafsdottir, S.M.; Schallmeiner, E.; Jarvius, J.; Bjarnegard, M.; Betsholtz, C.; Landegren, U.; Fredriksson, S. Cytokine detection by antibody-based proximity ligation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 8420–8424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, S.; Helbing, I.; Bohmer, S.A.; Hayashi, M.; Claesson-Welsh, L.; Soderberg, O.; Bohmer, F.D. In situ proximity ligation assay (in situ PLA) to assess PTP-protein interactions. Methods Mol. Biol. 2016, 1447, 217–242. [Google Scholar]

- Maszczak-Seneczko, D.; Sosicka, P.; Olczak, T.; Olczak, M. In situ proximity ligation assay (PLA) analysis of protein complexes formed between Golgi-resident, glycosylation-related transporters and transferases in adherent mammalian cell cultures. Methods Mol. Biol. 2016, 1496, 133–143. [Google Scholar]

- Löf, L.; Ebai, T.; Dubois, L.; Wik, L.; Ronquist, K.G.; Nolander, O.; Lundin, E.; Söderberg, O.; Landegren, U.; Kamali-Moghaddam, M. Detecting individual extracellular vesicles using a multicolor in situ proximity ligation assay with flow cytometric readout. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 34358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, S.S.; Hvid, M.; Pedersen, F.S.; Deleuran, B. Proximity ligation assay combined with flow cytometry is a powerful tool for the detection of cytokine receptor dimerization. Cytokine 2013, 64, 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leuchowius, K.J.; Weibrecht, I.; Söderberg, O. In situ proximity ligation assay for microscopy and flow cytometry. Curr. Protoc. Cytom. 2011, 56, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcatti, M.; Jamison, D.; Fracassi, A.; Zhang, W.-R.; Limon, A.; Taglialatela, G. A method to study human synaptic protein-protein interactions by using flow cytometry coupled to proximity ligation assay (Syn-FlowPLA). J. Neurosci. Methods 2023, 396, 109920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darmanis, S.; Nong, R.Y.; Hammond, M.; Gu, J.; Alderborn, A.; Vanelid, J.; Siegbahn, A.; Gustafsdottir, S.; Ericsson, O.; Landegren, U.; et al. Sensitive plasma protein analysis by microparticle-based proximity ligation assays. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2010, 9, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, M.; Eriksson, A.; Tran, B.; Assarsson, E.; Fredriksson, S. Homogeneous antibody-based proximity extension assays provide sensitive and specific detection of low-abundant proteins in human blood. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, e102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assarsson, E.; Lundberg, M.; Holmquist, G.; Björkesten, J.; Bucht Thorsen, S.; Ekman, D.; Eriksson, A.; Rennel Dickens, E.; Ohlsson, S.; Edfeldt, G. Homogenous 96-plex PEA immunoassay exhibiting high sensitivity, specificity, and excellent scalability. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e95192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berggrund, M.; Enroth, S.; Lundberg, M.; Assarsson, E.; Stålberg, K.; Lindquist, D.; Hallmans, G.; Grankvist, K.; Olovsson, M.; Gyllensten, U. Identification of candidate plasma protein biomarkers for cervical cancer using the multiplex proximity extension assay. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2019, 18, 735–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, J.B.; Kumar, A.; Hall, S.; Palmqvist, S.; Stomrud, E.; Bali, D.; Parchi, P.; Mattsson-Carlgren, N.; Janelidze, S.; Hansson, O. DOPA decarboxylase is an emerging biomarker for Parkinsonian disorders including preclinical Lewy body disease. Nat. Aging 2023, 3, 1201–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, R.; Moaddel, R.; Kwan, J.Y.; Rasheed, M.; Ruffo, P.; Landeck, N.; Reho, P.; Vasta, R.; Calvo, A.; Moglia, C. A plasma proteomics-based candidate biomarker panel predictive of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat. Med. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar, B.; Boustani, K.; Ogger, P.P.; Papadaki, A.; Tonkin, J.; Orton, C.M.; Ghai, P.; Suveizdyte, K.; Hewitt, R.J.; Desai, S.R. Immuno-proteomic profiling reveals aberrant immune cell regulation in the airways of individuals with ongoing post-COVID-19 respiratory disease. Immunity 2022, 55, 542–556.E5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blokzijl, A.; Nong, R.; Darmanis, S.; Hertz, E.; Landegren, U.; Kamali-Moghaddam, M. Protein biomarker validation via proximity ligation assays. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Proteins Proteom. 2014, 1844, 933–939. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.S.; Lai, E.M. Protein-protein interactions: Co-immunoprecipitation. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017, 1615, 211–219. [Google Scholar]

- Hegazy, M.; Cohen-Barak, E.; Koetsier, J.L.; Najor, N.A.; Arvanitis, C.; Sprecher, E.; Green, K.J.; Godsel, L.M. Proximity ligation assay for detecting protein-protein interactions and protein modifications in cells and tissues in situ. Curr. Protoc. Cell Biol. 2020, 89, e115. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, W.; Ma, Y.; Mou, Q.; Shao, X.; Lyu, M.; Garcia, V.; Kong, L.; Lewis, W.; Yang, Z.; Lu, S.; et al. Sialic acid aptamer and RNA in situ hybridization-mediated proximity ligation assay for spatial imaging of glycoRNAs in single cells. Nat. Protoc. 2025, 20, 1930–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teunissen, A.J.P.; Perez-Medina, C.; Meijerink, A.; Mulder, W.J.M. Investigating supramolecular systems using Forster resonance energy transfer. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 7027–7044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghisaidoobe, A.B.; Chung, S.J. Intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence in the detection and analysis of proteins: A focus on Forster resonance energy transfer techniques. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 22518–22538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuoriluoto, M.; Laine, L.J.; Saviranta, P.; Pouwels, J.; Kallio, M.J. Spatio-temporal composition of the mitotic Chromosomal Passenger Complex detected using in situ proximity ligation assay. Mol. Oncol. 2011, 5, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durhan, S.T.; Sezer, E.N.; Son, C.D.; Baloglu, F.K. Fast screening of protein-protein interactions using Forster resonance energy transfer (FRET-) based fluorescence plate reader assay in live cells. Appl. Spectrosc. 2023, 77, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohil, K.; Wu, S.Y.; Takahashi-Yamashiro, K.; Shen, Y.; Campbell, R.E. Biosensor optimization using a Forster resonance energy transfer pair based on mScarlet red fluorescent protein and an mScarlet-derived green fluore. ACS Sens. 2023, 8, 587–597. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Yang, J. Development of mKate3/HaloTag7 (JFX650) and CFP/YFP dual-fluorescence (or Forster) resonance energy transfer pairs for visualizing dual-molecular activity. ACS Sens. 2024, 9, 5264–5274. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanusic, D.; Eschricht, M.; Denner, J. Investigation of membrane protein-protein interactions using correlative FRET-PLA. Biotechniques 2014, 57, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felgueiras, J.; Silva, J.V.; Fardilha, M. Adding biological meaning to human protein-protein interactions identified by yeast two-hybrid screenings: A guide through bioinformatics tools. J. Proteom. 2018, 171, 127–140. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Y.; Li, G.; Wang, P.; Guo, Y.; Li, J. A simple and precise method (Y2H-in-frame-seq) improves yeast two-hybrid screening with cDNA libraries. J. Genet. Genom. 2022, 49, 595–598. [Google Scholar]

- Ietswaart, R.; Smalec, B.M.; Xu, A.; Choquet, K.; McShane, E.; Jowhar, Z.M.; Guegler, C.K.; Baxter-Koenigs, A.R.; West, E.R.; Fu, B.X.H. Genome-wide quantification of RNA flow across subcellular compartments reveals determinants of the mammalian transcript life cycle. Mol. Cell 2024, 84, 2765–2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrino, B.A.; Xie, Y.; Alexandru, C. Analyzing the integrin adhesome by in situ proximity ligation assay. Methods Mol. Biol. 2021, 2217, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Snider, J.; Kotlyar, M.; Saraon, P.; Yao, Z.; Jurisica, I.; Stagljar, I. Fundamentals of protein interaction network mapping. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2015, 11, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romer, T.; Leonhardt, H.; Rothbauer, U. Engineering antibodies and proteins for molecular in vivo imaging. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2011, 22, 882–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldinotti, R.; Pauzin, F.P.; Fevang, H.; Ishizuka, Y.; Bramham, C.R. A nanobody-based proximity ligation assay detects constitutive and stimulus-regulated native Arc/Arg3.1 oligomers in hippocampal neuronal dendrites. Mol. Neurobiol. 2025, 62, 3973–3990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedin, F.; Benoit, V.; Ferrazzi, E.; Aufradet, E.; Boulet, L.; Rubens, A.; Dalbon, P.; Imbaud, P. Procalcitonin detection in human plasma specimens using a fast version of proximity extension assay. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0281157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Wang, F.; Zou, W.; Li, X.; Lei, T.; Li, P.; Song, Y.; Liu, C.; Yue, J. Tumor endothelium-derived PODXL correlates with immunosuppressive microenvironment and poor prognosis in cervical cancer patients receiving radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy. Biomark Res. 2024, 12, 106. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.C.; Lin, K.T.; Chen, C.H.; Lee, S.A.; Lee, P.Y.; Liu, Y.W.; Kuo, Y.L.; Wang, F.S.; Lai, J.M.; Huang, C.Y. Using an in situ proximity ligation assay to systematically profile endogenous protein-protein interactions in a pathway network. J. Proteome Res. 2014, 13, 5339–5346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.M.; Jiang, Z.L.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, C.X.; Liu, H.Y.; Wan, J.H. The functions and mechanisms of post-translational modification in protein regulators of RNA methylation: Current status and future perspectives. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 126773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spoel, S.H.; Tada, Y.; Loake, G.J. Post-translational protein modification as a tool for transcription reprogramming. New Phytol. 2010, 186, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajadhar, A.; Guha, A. A proximity ligation assay using transiently transfected, epitope-tagged proteins: Application for in situ detection of dimerized receptor tyrosine kinases. Biotechniques 2010, 48, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heldin, J.; Sander, M.R.; Leino, M.; Thomsson, S.; Lennartsson, J.; Söderberg, O. Dynamin inhibitors impair platelet-derived growth factor β-receptor dimerization and signaling. Exp. Cell Res. 2019, 380, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.-C.; Liu, Y.-W.; Huang, Y.-H.; Yeh, Y.-C.; Chou, T.-Y.; Wu, Y.-C.; Wu, C.-C.; Chen, Y.-R.; Cheng, H.-C.; Lu, P.-J. Protein phosphorylation profiling using an in situ proximity ligation assay: Phosphorylation of AURKA-elicited EGFR-Thr654 and EGFR-Ser1046 in lung cancer cells. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e55657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazek, M.; Betz, C.; Hall, M.N.; Reth, M.; Zengerle, R.; Meier, M. Proximity ligation assay for high-content profiling of cell signaling pathways on a microfluidic chip. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2013, 12, 3898–3907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Liu, Z.; Yang, Q. The role of ubiquitination and deubiquitination in cancer metabolism. Mol. Cancer 2020, 19, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, L.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, X.; Wang, R.; You, Q.; Wang, L. Beyond Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeric Molecules: Designing Heterobifunctional Molecules Based on Functional Effectors. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 8091–8112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristic, M.; Brockly, F.; Piechaczyk, M.; Bossis, G. Detection of protein-protein interactions and posttranslational modifications using the proximity ligation assay: Application to the study of the SUMO pathway. Methods Mol. Biol. 2016, 1449, 279–290. [Google Scholar]

- Voeltz, G.K.; Sawyer, E.M.; Hajnóczky, G.; Prinz, W.A. Making the connection: How membrane contact sites have changed our view of organelle biology. Cell 2024, 187, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obara, C.J.; Nixon-Abell, J.; Moore, A.S.; Riccio, F.; Hoffman, D.P.; Shtengel, G.; Xu, C.S.; Schaefer, K.; Pasolli, H.A.; Masson, J.B.; et al. Motion of VAPB molecules reveals ER-mitochondria contact site subdomains. Nature 2024, 626, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhammouda, S.; Vishwakarma, A.; Gatti, P.; Germain, M. Mitochondria endoplasmic reticulum contact sites (MERCs): Proximity ligation assay as a tool to study organelle interaction. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 789959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamanaka, T.; Nishiyama, R.; Shimogori, T.; Nukina, N. Proteomics-Based Approach Identifies Altered ER Domain Properties by ALS-Linked VAPB Mutation. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dharan, A.; Talley, S.; Tripathi, A.; Mamede, J.I.; Majetschak, M.; Hope, T.J.; Campbell, E.M. KIF5B and Nup358 cooperatively mediate the nuclear import of HIV-1 during infection. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaan Profes, M.; Tiroumalechetty, A.; Patel, N.; Lauar, S.S.; Sidoli, S.; Kurshan, P.T. Characterization of the intracellular neurexin interactome by in vivo proximity ligation suggests its involvement in presynaptic actin assembly. PLoS Biol. 2024, 22, e3002466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.; Wei, J.; Zhang, L.; Hou, X.; Tan, J.; Yuan, Q.; Tan, W. Aptamer-Protein Interactions: From Regulation to Biomolecular Detection. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 12471–12506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurse, P. The discovery of cyclin-dependent kinases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2024, 25, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, M.; Fjeldbo, C.S.; Holm, R.; Stokke, T.; Kristensen, G.B.; Lyng, H. Mitochondrial Function of CKS2 Oncoprotein Links Oxidative Phosphorylation with Cell Division in Chemoradioresistant Cervical Cancer. Neoplasia 2019, 21, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blokzijl, A.; Zieba, A.; Hust, M.; Schirrmann, T.; Helmsing, S.; Grannas, K.; Hertz, E.; Moren, A.; Chen, L.; Soderberg, O. Single chain antibodies as tools to study TGF-beta regulated SMAD proteins in proximity ligationbased pharmacological screens. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2016, 15, 3374–3385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsuragi, Y.; Ichimura, Y.; Komatsu, M. p62/SQSTM 1 functions as a signaling hub and an autophagy adaptor. FEBS J. 2015, 282, 4672–4678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuzawa, Y.; Oshima, S.; Nibe, Y.; Kobayashi, M.; Maeyashiki, C.; Nemoto, Y.; Nagaishi, T.; Okamoto, R.; Tsuchiya, K.; Nakamura, T.; et al. RIPK3 regulates p62-LC3 complex formation via the caspase-8-dependent cleavage of p62. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 456, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, G.; Soleimanpour, S.A. Visualization of endogenous mitophagy complexes in situ in human pancreatic beta cells utilizing proximity ligation assay. J. Vis. Exp. 2019, 147, e59398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loibl, S.; Gianni, L. HER2-positive breast cancer. Lancet 2017, 389, 2415–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asgari-Karchekani, S.; Aryannejad, A.; Mousavi, S.A.; Shahsavarhaghighi, S.; Tavangar, S.M. The role of HER2 alterations in clinicopathological and molecular characteristics of breast cancer and HER2-targeted therapies: A comprehensive review. Med. Oncol. 2022, 39, 210. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- He, X.X.; Ding, L.; Lin, Y.; Shu, M.; Wen, J.M.; Xue, L. Protein expression of HER2, 3, 4 in gastric cancer: Correlation with clinical features and survival. J. Clin. Pathol. 2015, 68, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.L.; Yang, Y.S.; Xu, D.P.; Qu, J.H.; Guo, M.Z.; Gong, Y.; Huang, J. Comparative study on overexpression of HER2/neu and HER3 in gastric cancer. World J. Surg. 2009, 33, 2112–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capelan, M.; Pugliano, L.; De Azambuja, E.; Bozovic, I.; Saini, K.; Sotiriou, C.; Loi, S.; Piccart-Gebhart, M. Pertuzumab: New hope for patients with HER2-positive breast cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2013, 24, 273–282. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, S.S.; Dane, M.; Chin, K.; Tatarova, Z.; Liu, M.; Liby, T.; Thompson, W.; Smith, R.; Nederlof, M.; Bucher, E. Microenvironment-mediated mechanisms of resistance to HER2 inhibitors differ between HER2+ breast cancer subtypes. Cell Syst. 2018, 6, 329–342. [Google Scholar]

- Burden, H.; Holmes, C.; Persad, R.; Whittington, K. Prostasomes—Their effects on human male reproduction and fertility. Hum. Reprod. Update 2006, 12, 283–292. [Google Scholar]

- Tavoosidana, G.; Ronquist, G.; Darmanis, S.; Yan, J.H.; Carlsson, L.; Wu, D.; Conze, T.; Ek, P.; Semjonow, A.; Eltze, E.; et al. Multiple recognition assay reveals prostasomes as promising plasma biomarkers for prostate cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 8809–8814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramov, A.Y.; Berezhnov, A.V.; Fedotova, E.I.; Zinchenko, V.P.; Dolgacheva, L.P. Interaction of misfolded proteins and mitochondria in neurodegenerative disorders. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2017, 45, 1025–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahara, N.; Maeda, S.; Takashima, A. Tau oligomerization: A role for tau aggregation intermediates linked to neurodegeneration. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2008, 5, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzulli, J.R.; Mishizen, A.J.; Giasson, B.I.; Lynch, D.R.; Thomas, S.A.; Nakashima, A.; Nagatsu, T.; Ota, A.; Ischiropoulos, H. Cytosolic catechols inhibit α-synuclein aggregation and facilitate the formation of intracellular soluble oligomeric intermediates. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 10068–10078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finder, V.H.; Glockshuber, R. Amyloid-β aggregation. Neurodegener. Dis. 2007, 4, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengoa-Vergniory, N.; Velentza-Almpani, E.; Silva, A.M.; Scott, C.; Vargas-Caballero, M.; Sastre, M.; Wade-Martins, R.; Alegre-Abarrategui, J. Tau-proximity ligation assay reveals extensive previously undetected pathology prior to neurofibrillary tangles in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2021, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanis, L. α-Synuclein in Parkinson’s disease. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Med. 2012, 2, a009399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calogero, A.M.; Basellini, M.J.; Isilgan, H.B.; Longhena, F.; Bellucci, A.; Mazzetti, S.; Rolando, C.; Pezzoli, G.; Cappelletti, G. Acetylated α-Tubulin and α-Synuclein: Physiological interplay and contribution to α-synuclein oligomerization. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeStefano, V.; Khan, S.; Tabada, A. Applications of PLA in modern medicine. Eng. Regener. 2020, 1, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Beer, J.C.; Hao, Q.; Ariyapala, I.S.; Sahajan, A.; Komarov, A.; Cha, K.; Moua, M.; Qiu, X.; Xu, X. NULISA: A proteomic liquid biopsy platform with attomolar sensitivity and high multiplexing. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, E.L.; Allen, J.F. Tsg101, an inactive homologue of ubiquitin ligase e2, interacts specifically with human immunodeficiency virus type 2 gag polyprotein and results in increased levels of ubiquitinated gag. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 11226–11235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, A.N.; Waheed, A.A.; Ablan, S.D.; Huang, W.; Newton, A.; Petropoulos, C.J.; Brindeiro, R.D.; Freed, E.O. Elucidation of the molecular mechanism driving duplication of the HIV-1 PTAP late domain. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 768–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltezou, H.C.; Papanikolopoulou, A.; Vassiliu, S.; Theodoridou, K.; Nikolopoulou, G.; Sipsas, N.V. COVID-19 and respiratory virus co-infections: A systematic review of the literature. Viruses 2023, 15, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.W.; Chen, Y.J.; Chang, Y.W.; Huang, C.Y.; Liu, B.H.; Yu, F.Y. Novel enzyme-linked aptamer-antibody sandwich assay and hybrid lateral flow strip for SARS-CoV-2 detection. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 22, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; He, L.; Hu, Y.; Luo, Z.; Zhang, J. A serological aptamer-assisted proximity ligation assay for COVID-19 diagnosis and seeking neutralizing aptamers. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 12157–12164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heutmekers, M.; Gillet, P.; Maltha, J.; Scheirlinck, A.; Cnops, L.; Bottieau, E.; Van Esbroeck, M.; Jacobs, J. Evaluation of the rapid diagnostic test CareStart pLDH Malaria (Pf-pLDH/pan-pLDH) for the diagnosis of malaria in a reference setting. Malar. J. 2012, 11, 204. [Google Scholar]

- Poti, K.E.; Sullivan, D.J.; Dondorp, A.M.; Woodrow, C.J. HRP2: Transforming malaria diagnosis, but with caveats. Trends Parasitol. 2020, 36, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop, J.D.; Hsieh, H.V.; Gasperino, D.J.; Weigl, B.H. Sensitivity enhancement in lateral flow assays: A systems perspective. Lab Chip 2019, 19, 2486–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaesson, A.; Grannas, K.; Ebai, T.; Heldin, J.; Koos, B.; Leino, M.; Raykova, D.; Oelrich, J.; Arngården, L.; Söderberg, O. Improved efficiency of in situ protein analysis by proximity ligation using UnFold probes. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 5400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalili, R.; Horecka, J.; Swartz, J.R.; Davis, R.W.; Persson, H.H. Streamlined circular proximity ligation assay provides high stringency and compatibility with low-affinity antibodies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E925–E933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clausson, C.M.; Allalou, A.; Weibrecht, I.; Mahmoudi, S.; Farnebo, M.; Landegren, U.; Wahlby, C.; Soderberg, O. Increasing the dynamic range of in situ PLA. Nat. Methods 2011, 8, 892–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serebryannyy, L.A.; Misteli, T. HiPLA: High-throughput imaging proximity ligation assay. Methods 2019, 157, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shkel, O.; Kharkivska, Y.; Kim, Y.K.; Lee, J.S. Proximity labeling techniques: A multi-omics toolbox. Chem.-Asian J. 2022, 17, e202101240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darmanis, S.; Nong, R.Y.; Vänelid, J.; Siegbahn, A.; Ericsson, O.; Fredriksson, S.; Bäcklin, C.; Gut, M.; Heath, S.; Gut, I.G. ProteinSeq: High-performance proteomic analyses by proximity ligation and next generation sequencing. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e25583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vree, P.J.; De Wit, E.; Yilmaz, M.; Van De Heijning, M.; Klous, P.; Verstegen, M.J.; Wan, Y.; Teunissen, H.; Krijger, P.H.; Geeven, G. Targeted sequencing by proximity ligation for comprehensive variant detection and local haplotyping. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 1019–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vistain, L.; Van Phan, H.; Keisham, B.; Jordi, C.; Chen, M.; Reddy, S.T.; Tay, S. Quantification of extracellular proteins, protein complexes and mRNAs in single cells by proximity sequencing. Nat. Methods 2022, 19, 1578–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Wang, W.; Dang, K.; Ge, Q.; Zhao, X. Integration of single-cell transcriptome and proteome technologies: Toward spatial resolution levels. View 2023, 4, 20230040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wik, L.; Nordberg, N.; Broberg, J.; Björkesten, J.; Assarsson, E.; Henriksson, S.; Grundberg, I.; Pettersson, E.; Westerberg, C.; Liljeroth, E. Proximity extension assay in combination with next-generation sequencing for high-throughput proteome-wide analysis. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2021, 20, 100168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, M.H.; Nolan, G.P. Mass cytometry: Single cells, many features. Cell 2016, 165, 780–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Ding, X. The intriguing landscape of single-cell protein analysis. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2105932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frei, A.P.; Bava, F.A.; Zunder, E.R.; Hsieh, E.W.; Chen, S.Y.; Nolan, G.P.; Gherardini, P.F. Highly multiplexed simultaneous detection of RNAs and proteins in single cells. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Wang, T.; Kim, J.; Shannon, C.; Easley, C.J. Quantitation of femtomolar protein levels via direct readout with the electrochemical proximity assay. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 7066–7072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, A.B.; Kurian, A.S.N.; Easley, C.J. Nucleic-Acid Driven Cooperative Bioassays Using Probe Proximity or Split-Probe Techniques. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 198–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Yao, Y.; Luo, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, D.; Gao, F.; Wang, P. Proximity hybridization-regulated catalytic DNA hairpin assembly for electrochemical immunoassay based on in situ DNA template-synthesized Pd nanoparticles. Anal. Chim. Acta 2017, 969, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Qian, M.; Cheng, Y.; Qiu, X. Robust visualization of membrane protein by aptamer mediated proximity ligation assay and Förster resonance energy transfer. Colloids Surf. B 2025, 248, 114486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Luo, C.; Mei, Q.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, W.; Su, D.; Fu, W.; Luo, Y. Aptamer-cholesterol-mediated proximity ligation assay for accurate identification of exosomes. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 5411–5418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassanzadeh-Ghassabeh, G.; Devoogdt, N.; De Pauw, P.; Vincke, C.; Muyldermans, S. Nanobodies and their potential applications. Nanomedicine 2013, 8, 1013–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimmel, B.R.; Arora, K.; Chada, N.C.; Bharti, V.; Kwiatkowski, A.J.; Finkelstein, J.E.; Hanna, A.; Arner, E.N.; Sheehy, T.L.; Pastora, L.E. Potentiating cancer immunotherapies with modular albumin-hitchhiking nanobody–STING agonist conjugates. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.-N.; Zhu, L.; Qing, Y.-X.; Ye, S.-Y.; Ye, Q.-N.; Huang, X.-Y.; Zhao, D.-K.; Tian, T.-Y.; Li, F.-C.; Yan, G.-R. Engineering multi-specific nano-antibodies for cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Sieder, M.; Mitterer, M.; Reth, M.; Cavallari, M.; Yang, J. A new branched proximity hybridization assay for the quantification of nanoscale protein–protein proximity. PLoS Biol. 2019, 17, e3000569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, C.; Ruff, D.; Kirvell, S.; Johnson, G.; Dhillon, H.S.; Bustin, S.A. Proximity assays for sensitive quantification of proteins. Biomol. Detect. Quantif. 2015, 4, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.C.; Nederby, L.; Henriksen, M.O.; Hansen, M.; Nyvold, C.G. Sensitive ligand-based protein quantification using immuno-PCR: A critical review of single-probe and proximity ligation assays. Biotechniques 2014, 56, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albayrak, C.; Jordi, C.A.; Zechner, C.; Lin, J.; Bichsel, C.A.; Khammash, M.; Tay, S. Digital quantification of proteins and mRNA in single mammalian cells. Mol. Cell 2016, 61, 914–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koos, B.; Andersson, L.; Clausson, C.M.; Grannas, K.; Klaesson, A.; Cane, G.; Soderberg, O. Analysis of protein interactions in situ by proximity ligation assays. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2014, 377, 111–126. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | isPLA | Solution-Phase PLA |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Localization, visualization, contextual analysis | Quantification, profiling, biomarker discovery |

| Sample Type | Fixed cells, cytospins, tissue sections | Biological fluids (plasma, serum, urine), cell lysates |

| Sample State | Spatially intact, morphologically preserved | Homogenized liquid |

| Key Ligation Product | Circular DNA template | Linear DNA reporter molecule |

| Amplification Method | RCA | PCR |

| Readout Instrument | Fluorescence/confocal microscope, flow cytometer | qPCR instrument, digital PCR system, DNA sequencer |

| Key Advantage | Provides spatial context and subcellular localization | High sensitivity, high throughput, and high multiplexing capability |

| Primary Application | Mechanistic cell biology, pathology, validating interactions in situ | Clinical proteomics, diagnostics, systems biology |

| Feature | isPLA | Co-IP | FRET | Y2H |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Principle | Proximity-dependent DNA ligation and amplification | Antibody-based pulldown of protein complexes | Non-radiative energy transfer between fluorophores | Reconstitution of a transcription factor |

| Sample type | Fixed cells/tissues | Cell/tissue lysate | Live cells | Live yeast cells |

| Endogenous proteins | Yes | Yes | No (requires fusion tags) | No (requires fusion tags) |

| Spatial information | High (subcellular localization) | None (bulk lysate) | High (live-cell imaging) | Low (nuclear localization only) |

| Temporal resolution | Low (endpoint assay) | Low (endpoint assay) | High (real-time dynamics) | Low (endpoint assay) |

| Sensitivity | Very High (single-molecule) | Moderate to Low | Moderate | High (genetic amplification) |

| Throughput | Low to Medium (HiPLA) | Low | Low | Very High (screening) |

| Primary use | In situ validation, localization | Biochemical validation, discovery (with MS) | Live-cell dynamics, distance measurement | Discovery screening |

| Key advantage | In situ detection of endogenous interactions with high sensitivity and spatial context | Gold standard for biochemical validation; can identify unknown partners | Real-time analysis in living cells with high spatial resolution | Unbiased, genome-wide screening for novel interactions |

| Key limitation | Endpoint assay; semi-quantitative; requires specific antibodies; risk of proximity artifacts | No spatial information; may miss transient interactions | Requires overexpression of fusion proteins; complex setup | High false-positive rate; non-physiological context |

| Platform | Conventional isPLA | HiPLA | PLA-CyTOF | PLA-Seq | PLA with Super-Resolution | ECPLA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary readout | Fluorescent spots | Fluorescent spots (High-Content Imaging) | Fluorescence/Isotope signals (Single-cell) | DNA sequences (NGS) | Fluorescent spots (STED/STORM) | Electrical signal (Amperometr) |

| Throughput | Low | High | Very High | High | Very Low | High |

| Multiplexing capacity | Low (1–4 plex) | Low (1–2 plex per screen) | Medium to High (3–50+ plex) | Very High (100 s–1000 s+ plex) | Low (1–2 plex) | Low to Medium |

| Resolution | Diffraction-limited (~1 µm signal) | Diffraction-limited (~1 µm signal) | Single-cell population | Bulk tissue/cell population | Nanoscale (~20–50 nm) | Bulk sample |

| Primary advantage | Preserves subcellular spatial context for targeted interactions. | Enables systematic, image-based screening of interactomes. | High-dimensional, single-cell quantification of interactions and protein markers. | Enables discovery-oriented, interactome-scale profiling. | Visualizes the nanoscale organization of protein complexes in situ. | Low-cost, rapid, and portable; suitable for point-of-care diagnostics. |

| Key limitation | Low throughput; limited multiplexing. | Indirect multiplexing; requires large antibody libraries. | Loss of tissue architecture and subcellular spatial information. | Loss of single-cell and spatial resolution; complex bioinformatics. | Extremely low throughput; requires specialized microscopy. | Typically, lower multiplexing; less established for in situ use. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, H.; Ma, X.; Shi, D.; Wang, P. Proximity Ligation Assay: From a Foundational Principle to a Versatile Platform for Molecular and Translational Research. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1468. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15101468

Li H, Ma X, Shi D, Wang P. Proximity Ligation Assay: From a Foundational Principle to a Versatile Platform for Molecular and Translational Research. Biomolecules. 2025; 15(10):1468. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15101468

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Hengxuan, Xiangqi Ma, Dawei Shi, and Peng Wang. 2025. "Proximity Ligation Assay: From a Foundational Principle to a Versatile Platform for Molecular and Translational Research" Biomolecules 15, no. 10: 1468. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15101468

APA StyleLi, H., Ma, X., Shi, D., & Wang, P. (2025). Proximity Ligation Assay: From a Foundational Principle to a Versatile Platform for Molecular and Translational Research. Biomolecules, 15(10), 1468. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15101468