Psoriasis: The Versatility of Mesenchymal Stem Cell and Exosome Therapies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Disease Pathogenesis Mechanism

3. Signs and Symptoms of Psoriasis

4. The Diagnosis of Psoriasis

5. Treatment Methods for Psoriasis

6. Immunomodulatory Capability of MSCs and the Role of MSC Preconditioning

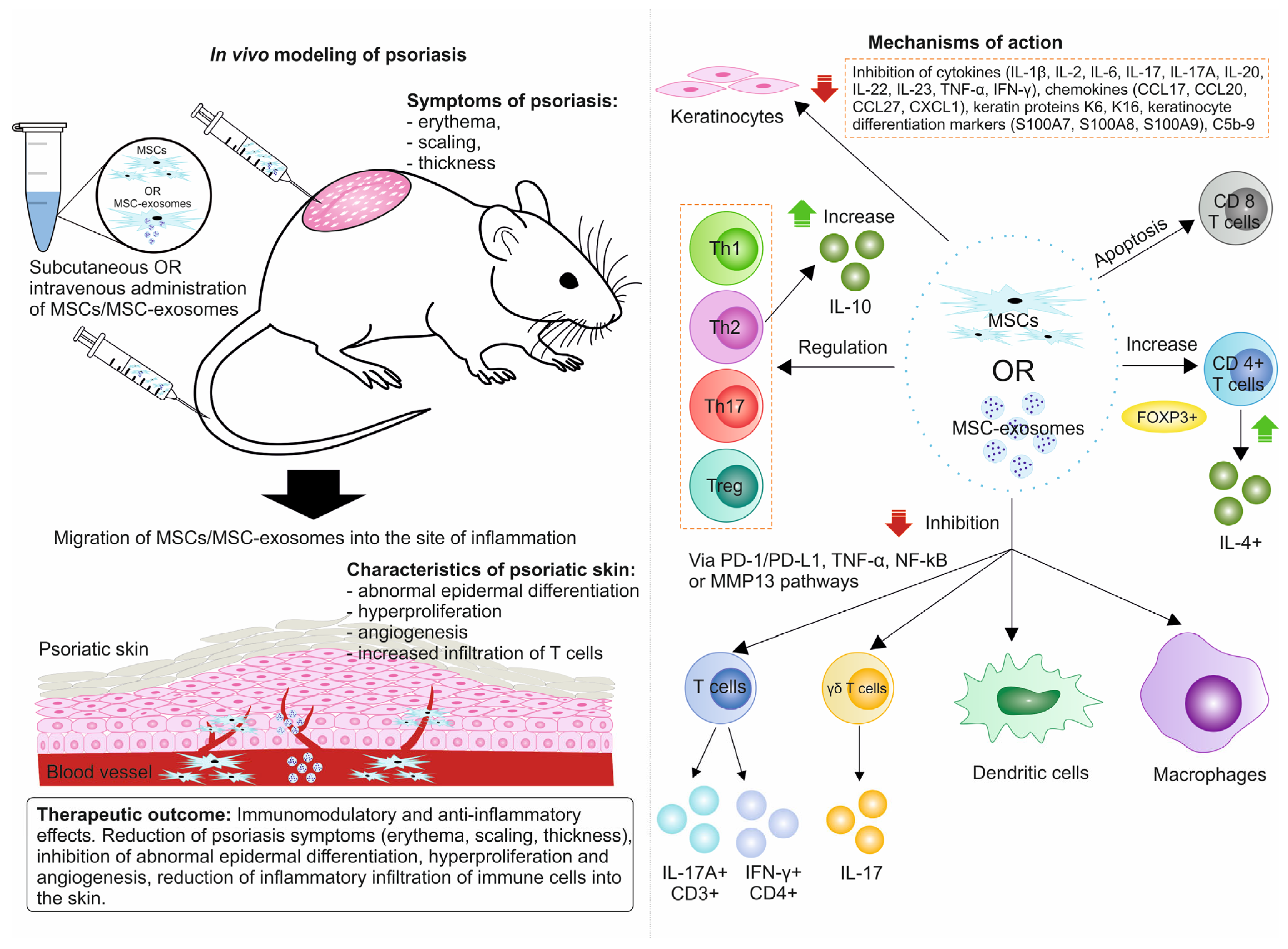

7. Preclinical Studies

7.1. In Vitro Studies

7.2. In Vivo Studies

8. Clinical Studies

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Branisteanu, D.E.; Cojocaru, C.; Diaconu, R.; Porumb, E.A.; Alexa, A.I.; Nicolescu, A.C.; Brihan, I.; Bogdanici, C.M.; Branisteanu, G.; Dimitriu, A.; et al. Update on the etiopathogenesis of psoriasis (Review). Exp. Ther. Med. 2022, 23, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raharja, A.; Mahil, S.K.; Barker, J.N. Psoriasis: A brief overview. Clin. Med. 2021, 21, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamiya, K.; Kishimoto, M.; Sugai, J.; Komine, M.; Ohtsuki, M. Risk factors for the development of psoriasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; He, M.; Jiang, J.; Duan, X.; Chai, B.; Zhang, J.; Tao, Q.; Chen, H. Triggers for the onset and recurrence of psoriasis: A review and update. Cell Commun. Signal. 2024, 22, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepat, A.; Chakole, S.; Rannaware, A. Psychological well-being of adult psoriasis patients: A narrative review. Cureus 2023, 15, e37702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Psoriasis Foundation. Available online: https://www.psoriasis.org/psoriasis-statistics/ (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Roostaeyan, O.; Kivelevitch, D.; Menter, A. A review article on brodalumab in the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Immunotherapy 2017, 9, 963–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dairov, A.; Issabekova, A.; Sekenova, A.; Shakhatbayev, M.; Ogay, V. Prevalence, incidence, gender and age distribution, and economic burden of psoriasis worldwide and in Kazakhstan. J. Clin. Med. Kaz. 2024, 21, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.-C.; Shyu, W.-C.; Lin, S.-Z. Mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Transplant. 2011, 20, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittenger, M.F.; Discher, D.E.; Péault, B.M.; Phinney, D.G.; Hare, J.M.; Caplan, A.I. Mesenchymal stem cell perspective: Cell biology to clinical progress. NPJ Regen. Med. 2019, 4, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hmadcha, A.; Martin-Montalvo, A.; Gauthier, B.R.; Soria, B.; Capilla-Gonzalez, V. Therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells for cancer therapy. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musiał-Wysocka, A.; Kot, M.; Majka, M. The pros and cons of mesenchymal stem cell-based therapies. Cell Transplant. 2019, 28, 801–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, T.; Yuan, Z.; Weng, J.; Pei, D.; Du, X.; He, C.; Lai, P. Challenges and advances in clinical applications of mesenchymal stromal cells. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 14, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volarevic, V.; Volarevic, B.S.; Gazdic, M.; Volarevic, A.; Jovicic, N.; Arsenijevic, N.; Armstrong, L.; Djonov, V.; Lako, M.; Stojkovic, M. Ethical and safety issues of stem cell-based therapy. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 15, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastrolia, I.; Foppiani, E.M.; Murgia, A.; Candini, O.; Samarelli, A.V.; Grisendi, G.; Veronesi, E.; Horwitz, E.M.; Dominici, M. Challenges in clinical development of mesenchymal stromal/stem cells: Concise review. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2019, 8, 1135–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, F.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Shahzad, K.; Zheng, J. Clinical applications of stem cell-derived exosomes. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2024, 9, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riazifar, M.; Pone, E.J.; Lötvall, J.; Zhao, W. Stem cell extracellular vesicles: Extended messages of regeneration. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2017, 57, 125–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Shen, H.; Xie, F.; Hu, D.; Jin, Q.; Hu, Y.; Zhong, T. Role of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes in the regeneration of different tissues. J. Biol. Eng. 2024, 18, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.-C.; Zheng, C.-X.; Sui, B.-D.; Liu, W.-J.; Jin, Y. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes: A novel and potential remedy for cutaneous wound healing and regeneration. World J. Stem Cells 2022, 14, 318–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, R.; Mesgin, R.M.; Nazari-Khanamiri, F.; Abdyazdani, N.; Imani, Z.; Talatapeh, S.P.; Nourmohammadi, A.; Nejati, V.; Rezaie, J. Mesenchymal stem cells-derived exosomes: Novel carriers for nanoparticle to combat cancer. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2023, 28, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Wu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Li, G.; Li, Z.; Liu, T. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes in cancer therapy resistance: Recent advances and therapeutic potential. Mol. Cancer. 2022, 21, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, A.; Wu, J.; Sun, Q. The role of mesenchymal stem cells derived exosomes as a novel nanobiotechnology target in the diagnosis and treatment of cancer. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1214190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zargar, M.J.; Kaviani, S.; Vasei, M.; Zomorrod, M.S.; Keshel, S.H.; Soleimani, M. Therapeutic role of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes in respiratory disease. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 13, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roszkowski, S. Therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes for regenerative medicine applications. Clin. Exp. Med. 2024, 24, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girolomoni, G.; Strohal, R.; Puig, L.; Bachelez, H.; Barker, J.; Boehncke, W.H.; Prinz, J.C. The role of IL-23 and the IL-23/TH 17 immune axis in the pathogenesis and treatment of psoriasis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2017, 31, 1616–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, J.; Luo, S.; Huang, Y.; Lu, Q. Critical role of environmental factors in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. J. Dermatol. 2017, 44, 863–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lande, R.; Botti, E.; Jandus, C.; Dojcinovic, D.; Fanelli, G.; Conrad, C.; Chamilos, G.; Feldmeyer, L.; Marinari, B.; Chon, S.; et al. The antimicrobial peptide LL37 is a T-cell autoantigen in psoriasis. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morizane, S.; Yamasaki, K.; Mühleisen, B.; Kotol, P.F.; Murakami, M.; Aoyama, Y.; Iwatsuki, K.; Hata, T.; Gallo, R.L. Cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide LL-37 in psoriasis enables keratinocyte reactivity against TLR9 ligands. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2012, 132, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dombrowski, Y.; Schauber, J. Cathelicidin LL-37: A defense molecule with a potential role in psoriasis pathogenesis. Exp. Dermatol. 2012, 21, 327–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yawalkar, N.; Tscharner, G.G.; Hunger, R.E.; Hassan, A.S. Increased expression of IL-12p70 and IL-23 by multiple dendritic cell and macrophage subsets in plaque psoriasis. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2009, 54, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stritesky, G.L.; Yeh, N.; Kaplan, M.H. IL-23 promotes maintenance but not commitment to the Th17 lineage. J. Immunol. 2008, 181, 5948–5955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, E.G.; Guo, C.; Rizzo, H.; Lillis, J.V.; Kurtz, S.E.; Skorcheva, I.; Purdy, D.; Fitch, E.; Iordanov, M.; Blauvelt, A. Th17 cytokines stimulate CCL20 expression in keratinocytes in vitro and in vivo: Implications for psoriasis pathogenesis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2009, 129, 2175–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.Q.F.; Akalu, Y.T.; Suarez-Farinas, M.; Gonzalez, J.; Mitsui, H.; Lowes, M.A.; Orlow, S.J.; Manga, P.; Krueger, J.G. IL-17 and TNF synergistically modulate cytokine expression while suppressing melanogenesis: Potential relevance to psoriasis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2013, 133, 2741–2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiricozzi, A.; Guttman-Yassky, E.; Suárez-Fariñas, M.; Nograles, K.E.; Tian, S.; Cardinale, I.; Chimenti, S.; Krueger, J.G. Integrative responses to IL-17 and TNF-α in human keratinocytes account for key inflammatory pathogenic circuits in psoriasis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2011, 131, 677–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brinkmann, V.; Reichard, U.; Goosmann, C.; Fauler, B.; Uhlemann, Y.; Weiss, D.S.; Weinrauch, Y.; Zychlinsky, A. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science 2004, 303, 1532–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pires, R.H.; Felix, S.B.; Delcea, M. The architecture of neutrophil extracellular traps investigated by atomic force microscopy. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 14193–14202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.C.-S.; Yu, H.-S.; Yen, F.-L.; Lin, C.-L.; Chen, G.-S.; Lan, C.-C.E. Neutrophil extracellular trap formation is increased in psoriasis and induces human β-defensin-2 production in epidermal keratinocytes. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujishima, S.; Hoffman, A.R.; Vu, T.; Kim, K.J.; Zheng, H.; Daniel, D.; Kim, Y.; Wallace, E.F.; Larrick, J.W.; Raffin, T.A. Regulation of neutrophil interleukin 8 gene expression and protein secretion by LPS, TNF-alpha, and IL-1 beta. J. Cell Physiol. 1993, 154, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herster, F.; Bittner, Z.; Archer, N.K.; Dickhöfer, S.; Eisel, D.; Eigenbrod, T.; Knorpp, T.; Schneiderhan-Marra, N.; Löffler, M.W.; Kalbacher, H.; et al. Neutrophil extracellular trap-associated RNA and LL37 enable self-amplifying inflammation in psoriasis. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strober, B.; van de Kerkhof, P.C.M.; Duffin, K.C.; Poulin, Y.; Warren, R.B.; de la Cruz, C.; van der Walt, J.M.; Stolshek, B.S.; Martin, M.L.; de Carvalho, A.V.E. Feasibility and utility of the Psoriasis Symptom Inventory (PSI) in clinical care settings: A study from the International Psoriasis Council. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2019, 20, 699–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ospanova, S.A.; Abilkasimova, G.E.; Ashueva, Z.I.; Kozhaeva, A.Z.; Zharylgaganov, T.M. Arthropathic psoriasis—Clinical and diagnostic criteria, treatment principles. Vestn. KazNMU. 2013, 2, 45–48. Available online: http://rmebrk.kz/magazine/4336# (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Blackstone, B.; Patel, R.; Bewley, A. Assessing and improving psychological well-being in psoriasis: Considerations for the clinician. Psoriasis 2022, 12, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korman, N.J. Management of psoriasis as a systemic disease: What is the evidence? Br. J. Dermatol. 2020, 182, 840–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branisteanu, D.E.; Pirvulescu, R.A.; Spinu, A.E.; Porumb, E.A.; Cojocaru, M.; Nicolescu, A.C.; Branisteanu, D.C.; Branisteanu, C.I.; Dimitriu, A.; Alexa, A.I.; et al. Metabolic comorbidities of psoriasis (Review). Exp. Ther. Med. 2022, 23, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Wu, L.; Xiao, S.; Ji, Y.; Tan, Y.; Jiang, C.; Zhang, G. Dysregulation of the gut-brain-skin axis and key overlapping inflammatory and immune mechanisms of psoriasis and depression. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 137, 111065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.-J.; Zhang, X.-B. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of psoriasis in China: 2019 concise edition#. Int. J. Dermatol. Venereol. 2020, 3, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, K.; Okada, Y. The current landscape of psoriasis genetics in 2020. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2020, 99, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, P.; Oliveira, M.; Matos, J. Striae: A potential precipitating factor for Koebner phenomenon in psoriasis? Dermatol. Online J. 2013, 19, 18186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Han, J.; Choi, H.K.; Qureshi, A.A. Smoking and risk of incident psoriasis among women and men in the United States: A combined analysis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2012, 175, 402–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, P.; Nandar, S.K.; Kathuria, S.; Ramesh, V. Effects of air pollution on the skin: A review. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2017, 83, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunes, A.T.; Fetil, E.; Akarsu, S.; Ozbagcivan, O.; Babayeva, L. Possible triggering effect of influenza vaccination on psoriasis. J. Immunol. Res. 2015, 2015, 258430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sbidian, E.; Eftekahri, P.; Viguier, M.; Laroche, L.; Chosidow, O.; Gosselin, P.; Trouche, F.; Bonnet, N.; Arfi, C.; Tubach, F.; et al. National survey of psoriasis flares after 2009 monovalent H1N1/seasonal vaccines. Dermatology 2014, 229, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koca, R.; Altinyazar, C.; Numanoğlu, G.; Unalacak, M. Guttate psoriasis-like lesions following BCG vaccination. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2004, 50, 178–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, A.W.; Harskamp, C.T.; Armstrong, E.J. Psoriasis and the risk of diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2013, 149, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salihbegovic, E.M.; Hadzigrahic, N.; Suljagic, E.; Kurtalic, N.; Hadzic, J.; Zejcirovic, A.; Bijedic, M.; Handanagic, A. Psoriasis and dyslipidemia. Mater. Sociomed. 2015, 27, 15–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, P.; Skov, L. Psoriasis and obesity. Dermatology 2016, 232, 633–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-N.; Han, K.; Song, S.-W.; Lee, J.H. Hypertension and risk of psoriasis incidence: An 11-year nationwide population-based cohort study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0202854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micali, G.; Verzì, A.E.; Giuffrida, G.; Panebianco, E.; Musumeci, M.L.; Lacarrubba, F. Inverse psoriasis: From diagnosis to current treatment options. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2019, 12, 953–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisondi, P.; Bellinato, F.; Girolomoni, G. Topographic differential diagnosis of chronic plaque psoriasis: Challenges and tricks. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandon, A.; Mufti, A.; Sibbald, R.G. Diagnosis and management of cutaneous psoriasis: A review. Adv. Ski. Wound Care 2019, 32, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Sun, L. Clinical value of dermoscopy in psoriasis. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2024, 23, 370–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Wang, Z.; Cui, Y.; Wang, J.; Gao, B.; Chen, C.; Zhu, Y.; Herre, H. A prototype for diagnosis of psoriasis in traditional Chinese medicine. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2022, 73, 5197–5217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullano, S.A.; Bianco, M.G.; Greco, M.; Mazzuca, D.; Nisticò, S.P.; Fiorillo, A.S. FT-IR saliva analysis for the diagnosis of psoriasis: A pilot study. Biomed. Signal Proces. Control 2022, 74, 103525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.-Y.; Fei, W.-M.; Li, C.-X.; Cui, Y. Comparison of dermoscopy and reflectance confocal microscopy accuracy for the diagnosis of psoriasis and lichen planus. Ski. Res. Technol. 2022, 28, 480–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, F.; Doll, A.; Uereyener, D.; Roenneberg, S.; Hillig, C.; Weber, L.; Hackert, V.; Meinel, M.; Farnoud, A.; Seiringer, P.; et al. Gene expression-based molecular test as diagnostic aid for the differential diagnosis of psoriasis and eczema in formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue, microbiopsies, and tape strips. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2023, 143, 1461–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujita, H.; Gooderham, M.; Romiti, R. Diagnosis of generalized pustular psoriasis. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2022, 23, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yorulmaz, A. Dermoscopy: The ultimate tool for diagnosis of nail psoriasis? A review of the diagnostic utility of dermoscopy in nail psoriasis. Acta Dermatovenerol. Alp. Pannonica Adriat. 2023, 32, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverberg, J.I.; Hou, A.; DeKoven, J.G.; Warshaw, E.M.; Maibach, H.I.; Atwater, A.R.; Belsito, D.V.; Zug, K.A.; Taylor, J.S.; Sasseville, D.; et al. Prevalence and trend of allergen sensitization in patients referred for patch testing with a final diagnosis of psoriasis: North American Contact Dermatitis Group data, 2001–2016. Contact Dermatitis. 2021, 85, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Wei, G.; Shao, C.; Zhu, M.; Sun, S.; Zhang, X. Analysis of dermoscopic characteristic for the differential diagnosis of palmoplantar psoriasis and palmoplantar eczema. Medicine 2021, 100, e23828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, M.; Londhe, N.D.; Ghosh, S.; Shrivastava, V.K.; Sonawane, R.S. Swarm intelligence based clustering technique for automated lesion detection and diagnosis of psoriasis. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2020, 86, 107247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Su, L.; Zhuang, L.; Wu, J.; Zhuang, J. Clinical value of vitamin D, trace elements, glucose, and lipid metabolism in diagnosis and severity evaluation of psoriasis. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2022, 2022, 8622435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourani, M.R.; Abdollahimajd, F.; Zargari, O.; Dadras, M.S. Soluble biomarkers for diagnosis, monitoring, and therapeutic response assessment in psoriasis. J. Dermatolog. Treat. 2022, 33, 1967–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibad, S.; Heibel, H.D.; Cockerell, C.J. Specificity of the histopathologic diagnosis of psoriasis. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2021, 43, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grajdeanu, I.-A.; Statescu, L.; Vata, D.; Popescu, I.A.; Porumb-Andrese, E.; Patrascu, A.I.; Taranu, T.; Crisan, M.; Solovastru, L.G. Imaging techniques in the diagnosis and monitoring of psoriasis. Exp. Ther. Med. 2019, 18, 4974–4980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinberg, I.; Huland, D.M.; Vermesh, O.; Frostig, H.E.; Tummers, W.S.; Gambhir, S.S. Photoacoustic clinical imaging. Photoacoustics 2019, 14, 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, C.; Bordagaray, M.J.; Villarroel, J.L.; Flores, T.; Benadof, D.; Fernández, A.; Valenzuela, F. Biomarkers in oral fluids as diagnostic tool for psoriasis. Life 2022, 12, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; He, Y.; Gao, L.; Tong, X.; Zhou, L.; Zeng, J. STAT2/Caspase3 in the diagnosis and treatment of psoriasis. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 53, e13959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camporro, A.F.; Roncero-Riesco, M.; Revelles-Peñas, L.; Nebreda, D.R.; Estenaga, Á.; de la Pinta, J.D.; Terrón, Á.S.B. The ñ sign: A visual clue for the histopathologic diagnosis of psoriasis. JAMA Dermatol. 2022, 158, 451–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisondi, P.; Del Giglio, M.; Girolomoni, G. Treatment approaches to moderate to severe psoriasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schadler, E.D.; Ortel, B.; Mehlis, S.L. Biologics for the primary care physician: Review and treatment of psoriasis. Dis. Mon. 2019, 65, 51–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-J.; Kim, M. Challenges and future trends in the treatment of psoriasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, C.E.M.; Armstrong, A.W.; Gudjonsson, J.E.; Barker, J.N.W.N. Psoriasis. Lancet 2021, 397, 1301–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costache, D.O.; Feroiu, O.; Ghilencea, A.; Georgescu, M.; Căruntu, A.; Căruntu, C.; Țiplica, S.G.; Jinga, M.; Costache, R.S. Skin inflammation modulation via TNF-α, IL-17, and IL-12 family inhibitors therapy and cancer control in patients with psoriasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trémezaygues, L.; Reichrath, J. Vitamin D analogs in the treatment of psoriasis: Where are we standing and where will we be going? Dermatoendocrinol 2011, 3, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huu, D.L.; Minh, T.N.; Van, T.N.; Minh, P.P.T.; Huu, N.D.; Cam, V.T.; Huyen, M.L.; Nguyet, M.V.; Thi, M.L.; Thu, H.D.T.; et al. The effectiveness of narrow band uvb (Nb-Uvb) in the treatment of pityriasis lichenoides chronica (PLC) in Vietnam. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 7, 221–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Zhao, Z.; Yu, Q.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xu, P.; Yu, Z.; Guo, C.; et al. Human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate psoriasis-like dermatitis by suppressing IL-17-producing γδ T cells. Cell Tissue Res. 2022, 388, 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, D.; Ye, S.; He, Z.; Huang, Y.; Deng, J.; Wen, Z.; Chen, X.; Li, H.; Han, Q.; Deng, H.; et al. Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (AD-MSCs) in the treatment for psoriasis: Results of a single-arm pilot trial. Ann. Transl. Med. 2021, 9, 1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diotallevi, F.; Di Vincenzo, M.; Martina, E.; Radi, G.; Lariccia, V.; Offidani, A.; Orciani, M.; Campanati, A. Mesenchymal stem cells and psoriasis: Systematic review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiñones-Vico, M.I.; Sanabria-de la Torre, R.; Sánchez-Díaz, M.; Sierra-Sánchez, Á.; Montero-Vílchez, T.; Fernández-González, A.; Arias-Santiago, S. The role of exosomes derived from mesenchymal stromal cells in dermatology. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 647012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.R.; Lee, S.Y.; You, G.E.; Kim, H.O.; Park, C.W.; Chung, B.Y. Adipose-derived stem cell exosomes alleviate psoriasis serum exosomes-induced inflammation by regulating autophagy and redox status in keratinocytes. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2023, 16, 3699–3711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolbinger, F.; Di Padova, F.; Deodhar, A.; Hawkes, J.E.; Huppertz, C.; Kuiper, T.; McInnes, I.B.; Ritchlin, C.T.; Rosmarin, D.; Schett, G.; et al. Secukinumab for the treatment of psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and axial spondyloarthritis: Physical and pharmacological properties underlie the observed clinical efficacy and safety. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 229, 107925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, C.W.; Loft, N.; Andersen, V.; Juul, L.; Zachariae, C.; Skov, L. Are systemic corticosteroids causing psoriasis flare-ups? Questionnaire for Danish dermatologists, gastroenterologists and rheumatologists. Dermatology 2021, 237, 588–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, A.; Panda, S. Use of topical corticosteroids in dermatology: An evidence-based approach. Indian J. Dermatol. 2017, 62, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, J.; Huang, H.; Luo, G.; Yin, L.; Li, B.; Chen, S.; Li, H.; Yang, Y.; Yang, X. NB-UVB irradiation attenuates inflammatory response in psoriasis. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 33, e13626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alyoussef, A. Excimer laser system: The revolutionary way to treat psoriasis. Cureus 2023, 15, e50249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, W.-R.; Zhang, Q.-Z.; Shi, S.-H.; Nguyen, A.L.; Le, A.D. Human gingiva-derived mesenchymal stromal cells attenuate contact hypersensitivity via prostaglandin E2-dependent mechanisms. Stem Cells 2011, 29, 1849–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Cao, W.; Shi, Y. Plasticity of mesenchymal stem cells in immunomodulation: Pathological and therapeutic implications. Nat. Immunol. 2014, 15, 1009–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokabu, S.; Lowery, J.W.; Jimi, E. Cell fate and differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Int. 2016, 2016, 3753581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Ren, H.; Han, Z. Mesenchymal stem cells: Immunomodulatory capability and clinical potential in immune diseases. J. Cell Immunoth. 2016, 2, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittenger, M.F.; Mackay, A.M.; Beck, S.C.; Jaiswal, R.K.; Douglas, R.; Mosca, J.D.; Moorman, M.A.; Simonetti, D.W.; Craig, S.; Marshak, D.R. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science 1999, 284, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.-M.; Du, D.-Y.; Li, Y.-T.; Ge, X.-L.; Qin, P.-T.; Zhang, Q.-H.; Liu, Y. Allogeneic bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells transplantation for stabilizing and repairing of atherosclerotic ruptured plaque. Thromb. Res. 2013, 131, e253–e257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; L’Huillier, A.; Ling, W.; Roberts, A.I.; Le, A.D.; Shi, S.; Shao, C.; et al. Inflammatory cytokine-induced intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 in mesenchymal stem cells are critical for immunosuppression. J. Immunol. 2010, 184, 2321–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyurkchiev, D.; Bochev, I.; Ivanova-Todorova, E.; Mourdjeva, M.; Oreshkova, T.; Belemezova, K.; Kyurkchiev, S. Secretion of immunoregulatory cytokines by mesenchymal stem cells. World J. Stem Cells 2014, 6, 552–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carosella, E.D.; Rouas-Freiss, N.; Tronik-Le Roux, D.; Moreau, P.; LeMaoult, J. HLA-G: An immune checkpoint molecule. Adv. Immunol. 2015, 127, 33–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Cássia Noronha, N.; Mizukami, A.; Caliári-Oliveira, C.; Cominal, J.G.; Rocha, J.L.M.; Covas, D.T.; Swiech, K.; Malmegrim, K.C.R. Priming approaches to improve the efficacy of mesenchymal stromal cell-based therapies. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2019, 10, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, W.; Xu, J. Immune modulation by mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Prolif. 2020, 53, e12712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaundal, U.; Bagai, U.; Rakha, A. Immunomodulatory plasticity of mesenchymal stem cells: A potential key to successful solid organ transplantation. J. Transl. Med. 2018, 16, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- François, M.; Romieu-Mourez, R.; Li, M.; Galipeau, J. Human MSC suppression correlates with cytokine induction of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and bystander M2 macrophage differentiation. Mol. Ther. 2012, 20, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, T.; Ji, G.; Qian, M.; Li, Q.X.; Huang, H.; Deng, S.; Liu, P.; Deng, W.; Wei, Y.; He, J.; et al. Intracellular delivery of nitric oxide enhances the therapeutic efficacy of mesenchymal stem cells for myocardial infarction. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadi9967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-S.; Yun, J.-W.; Shin, T.-H.; Lee, S.-H.; Lee, B.-C.; Yu, K.-R.; Seo, Y.; Lee, S.; Kang, T.-W.; Choi, S.W.; et al. Human umbilical cord blood mesenchymal stem cell-derived PGE2 and TGF-β1 alleviate atopic dermatitis by reducing mast cell degranulation. Stem Cells 2015, 33, 1254–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaggiari, G.M.; Capobianco, A.; Becchetti, S.; Mingari, M.C.; Moretta, L. Mesenchymal stem cell-natural killer cell interactions: Evidence that activated NK cells are capable of killing MSCs, whereas MSCs can inhibit IL-2-induced NK-cell proliferation. Blood 2006, 107, 1484–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Tam, P.K.H. Immunomodulatory mechanisms of mesenchymal stem cells and their potential clinical applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Xie, J.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Xue, M.; Chen, J.; Yang, Y.; Qiu, H. Overexpressing TGF-β1 in mesenchymal stem cells attenuates organ dysfunction during CLP-induced septic mice by reducing macrophage-driven inflammation. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 11, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, E.; Hu, M.; Wu, L.; Pan, X.; Zhu, Q.; Liu, H.; Kiu, Y. TGF-β signaling regulates differentiation of MSCs in bone metabolism: Disputes among viewpoints. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, P.; Han, T.; Xiang, X.; Wang, Y.; Fang, H.; Niu, Y.; Shen, C. The role of hepatocyte growth factor in mesenchymal stem cell-induced recovery in spinal cord injured rats. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 11, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Chen, X.; Wu, X.; Wei, S.; Han, W.; Lin, J.; Kang, M.; Chen, L. Hepatocyte growth factor-modified mesenchymal stem cells improve ischemia/reperfusion-induced acute lung injury in rats. Gene Ther. 2017, 24, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Ding, H.; Shi, X.; Ren, H. Mesenchymal stem cell-secreted prostaglandin E2 ameliorates acute liver failure via attenuation of cell death and regulation of macrophage polarization. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Hu, X.; Liu, J. PGE2 overexpressing human embryonic stem cell derived mesenchymal stromal cell relieves liver fibrosis in an immuno-suppressive manner. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2024, 20, 1667–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.-G.; Li, B.-B.; Zhou, L.; Yan, D.; Xie, Q.-L.; Zhao, W. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxgenase-transfected mesenchymal stem cells suppress heart allograft rejection by increasing the production and activity of dendritic cells and regulatory T cells. J. Investig. Med. 2020, 68, 728–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.; Chang, L.; Sun, X.; Qi, Y.; Huang, R.; Chen, K.; Wang, B.; Kang, L.; Wang, L.; Xu, B. Infusion of two-dose mesenchymal stem cells is more effective than a single dose in a dilated cardiomyopathy rat model by upregulating indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase expression. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 13, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria, A.T.J.; Rozier, P.; Fonteneau, G.; Sutra, T.; Maumus, M.; Toupet, K.; Cristol, J.-P.; Jorgensen, C.; Guilpain, P.; Noël, D. iNOS activity is required for the therapeutic effect of mesenchymal stem cells in experimental systemic sclerosis. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phinney, D.G.; Pittenger, M.F. Concise review: MSC-derived exosomes for cell-free therapy. Stem Cells 2017, 35, 851–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orciani, M.; Campanati, A.; Salvolini, E.; Lucarini, G.; Di Benedetto, G.; Offidani, A.; Di Primio, R. The mesenchymal stem cell profile in psoriasis. Br. J. Dermatol. 2011, 165, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Wang, J.; Liang, J.; Hou, H.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Cao, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, K. Psoriatic mesenchymal stem cells stimulate the angiogenesis of human umbilical vein endothelial cells in vitro. Microvasc. Res. 2021, 136, 104151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, W.; Liang, N.; Cao, Y.; Xing, J.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Zhao, X.; Li, J.; Niu, X.; Hou, R.; et al. The effects of human dermal-derived mesenchymal stem cells on the keratinocyte proliferation and apoptosis in psoriasis. Exp. Dermatol. 2021, 30, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Jiao, J.; Li, X.; Hou, R.; Li, J.; Niu, X.; Liu, R.; Yang, X.; Li, J.; Liang, J.; et al. Immunomodulatory effect of psoriasis-derived dermal mesenchymal stem cells on TH1/TH17 cells. Eur. J. Dermatol. 2021, 31, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Liang, N.; Li, J.; Yang, X.; Xing, J.; Zhou, L.; Li, J.; Hou, R.; et al. Normal mesenchymal stem cells can improve the abnormal function of T cells in psoriasis via upregulating transforming growth factor-β receptor. J. Dermatol. 2022, 49, 988–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanati, A.; Orciani, M.; Sorgentoni, G.; Consales, V.; Mattioli Belmonte, M.; Di Primio, M.; Offidani, A. Indirect co-cultures of healthy mesenchymal stem cells restore the physiological phenotypical profile of psoriatic mesenchymal stem cells. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2018, 193, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sah, S.K.; Park, K.H.; Yun, C.-O.; Kang, K.-S.; Kim, T.-Y. Effects of human mesenchymal stem cells transduced with superoxide dismutase on imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like skin inflammation in mice. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 2016, 24, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Lin, J.; Shi, P.; Su, D.; Cheng, X.; Yi, W.; Yan, J.; Chen, H.; Cheng, F. Small extracellular vesicles derived from MSCs have immunomodulatory effects to enhance delivery of ASO-210 for psoriasis treatment. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 842813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yan, J.; Li, Z.; Zheng, J.; Sun, Q. Exosomes derived from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells alleviate psoriasis-like skin inflammation. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2022, 42, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, S.C.; Cardoso, R.M.S.; Freire, P.C.; Gomes, C.F.; Duarte, F.V.; Pires das Neves, R.; Simões-Correia, J. Immunomodulatory properties of umbilical cord blood-derived small extracellular vesicles and their therapeutic potential for inflammatory skin disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Xiao, M.; Ma, K.; Li, H.; Ran, M.; Yang, S.; Yang, Y.; Fu, X.; Yang, S. Therapeutic effects of mesenchymal stem cells and their derivatives in common skin inflammatory diseases: Atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1092668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.S.; Sah, S.K.; Lee, J.H.; Seo, K.-W.; Kang, K.-S.; Kim, T.-Y. Human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate psoriasis-like skin inflammation in mice. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2017, 9, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-Y.; Park, M.; Kim, Y.-H.; Ryu, K.-H.; Lee, K.-H.; Cho, K.-A.; Woo, S.-Y. Tonsil-derived mesenchymal stem cells (T-MSCs) prevent Th17-mediated autoimmune response via regulation of the programmed death-1/programmed death ligand-1 (PD-1/PD-L1) pathway. J. Tissue Eng. Reg. Med. 2018, 12, e1022–e1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Peng, J.; Xie, Q.; Xiao, N.; Su, X.; Mei, H.; Lu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Dai, Y.; Wang, S.; et al. Mesenchymal stem cells alleviate moderate-to-severe psoriasis by reducing the production of type I interferon (IFN-I) by plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs). Stem Cells Int. 2019, 2019, 6961052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, Y.; Yamahara, K.; Hamada, A.; Fujimori, Y.; Yamanishi, K. Human amnion-derived mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate imiquimod-induced psoriasiform dermatitis in mice. J. Dermatol. 2019, 46, 276–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Lai, R.C.; Sim, W.K.; Choo, A.B.H.; Lane, E.B.; Lim, S.K. Topical application of mesenchymal stem cell exosomes alleviates the imiquimod induced psoriasis-like inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokunohe, A.; Matsuzaki, Y.; Rokunohe, D.; Sakuraba, Y.; Fukui, T.; Nakano, H.; Sawamura, D. Immunosuppressive effect of adipose-derived stromal cells on imiquimod-induced psoriasis in mice. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2016, 82, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, F.; Fei, Z.; Dai, H.; Xu, J.; Fan, Q.; Shen, S.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Q.; Chu, J.; Peng, F.; et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles with high PD-L1 expression for autoimmune diseases treatment. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, e2106265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Zhong, W.; Li, W.; Tang, M.; Zhang, K.; Zhou, F.; Shi, X.; Wu, J.; Yu, B.; Huang, C.; et al. Human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells alleviate psoriasis through TNF-α/NF-κB/MMP13 pathway. Inflammation 2023, 46, 987–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuesta-Gomez, N.; Medina-Ruiz, L.; Graham, G.J.; Campbell, J.D.M. IL-6 and TGF-β-secreting adoptively-transferred murine mesenchymal stromal cells accelerate healing of psoriasis-like skin inflammation and upregulate IL-17A and TGF-β. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, S.S.; Rafla, M.; El-Nefiawy, N.E.; Abdel Hamid, H.F.; Amin, M.A.; Fetouh, M.A. A potential role of mesenchymal stem cells derived from human umbilical cord blood in ameliorating psoriasis-like skin lesion in the rats. Folia Morphol. 2022, 81, 614–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Niu, J.-W.; Ning, H.-M.; Pan, X.; Li, X.-B.; Li, Y.; Wang, D.-H.; Hu, L.-D.; Sheng, H.-X.; Xu, M.; et al. Treatment of psoriasis with mesenchymal stem cells. Am. J. Med. 2016, 129, e13–e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.G.; Hsu, N.C.; Wang, S.M.; Wang, F.N. Successful treatment of plaque psoriasis with allogeneic gingival mesenchymal stem cells: A case study. Case Rep. Dermatol. Med. 2020, 2020, 4617520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jesus, M.M.; Santiago, J.S.; Trinidad, C.V.; See, M.E.; Semon, K.R.; Fernandez, M.O.; Chung, F.S. Autologous adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells for the treatment of psoriasis vulgaris and psoriatic arthritis: A case report. Cell Transplant. 2016, 25, 2063–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajouri, A.; Dayani, D.; Sharghi, A.T.; Karimi, S.; Niknezhadi, M.; Bidgoli, K.M.; Madani, H.; Kakroodi, F.A.; Bolurieh, T.; Mardpour, S.; et al. Subcutaneous injection of allogeneic adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells in psoriasis plaques: Clinical trial phase I subcutaneous injection of allogeneic adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells in psoriasis plaques: Clinical trial phase I. Cell J. 2023, 25, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comella, K.; Parlo, M.; Daly, R.; Dominessy, K. First-in-man intravenous implantation of stromal vascular fraction in psoriasis: A case study. Int. Med. Case Rep. J. 2018, 11, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seetharaman, R.; Mahmood, A.; Kshatriya, P.; Patel, D.; Srivastava, A. Mesenchymal stem cell conditioned media ameliorate psoriasis vulgaris: A case study. Case Rep. Dermatol. Med. 2019, 2019, 8309103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Wang, S.; Peng, C.; Zou, X.; Yang, C.; Mei, H.; Li, C.; Su, X.; Xiao, N.; Ouyang, Q.; et al. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells for psoriasis: A phase 1/2a, single-arm study. Sig. Trunsduct. Target Ther. 2022, 7, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güler, D.; Gürel, G.; Yalçın, G.Ş.; Eker, İ.; Durusu, İ.N.; Özdemir, Ç.; Vural, Ö. A case of pediatric psoriasis achieving remission after allogenic bone marrow transplantation. Turk. J. Pediatr. 2021, 63, 1078–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meybodi, M.A.M.; Nilforoushzadeh, M.A.; KhandanDezfully, N.; Mansouri, P. The safety and efficacy of adipose tissue-derived exosomes in treating mild to moderate plaque psoriasis: A clinical study. Life Sci. 2024, 353, 122915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment Method | Therapeutic Effect | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biologics | IL-17, TNF-α, IL-12, IL-23 inhibitors (e.g., infliximab, ixekizumab, secukinumab, apremilast) | Significant improvement in psoriasis severity (PASI 100 response) and long-term control of symptoms, including sustained inhibition of radiographic progression in psoriatic arthritis patients. | [79,80,82,91] |

| IL-17 + TNF-α combination therapy | Enhanced reduction in skin lesions and better control of systemic inflammation compared to monotherapy with either inhibitor. | [79] | |

| Systemic therapy | Corticosteroid injections | Directly reduces inflammation and controls severe flare-ups, but may cause localized side effects such as atrophy. | [92] |

| Oral therapy: acitretin, cyclosporine, methotrexate | Reduces general symptoms of psoriasis, can replace other methods that were restricted. | [81] | |

| Topical therapy | Topical corticosteroids | Significant reduction in inflammation, plaque thickness, and erythema. Long-term use may lead to skin thinning and other side effects. | [93] |

| Ointments, vitamin D analogues (e.g., calcipotriene, calcitriol) | Slows down skin cell proliferation, reduces plaque formation, and is often used in combination with corticosteroids for enhanced effect. | [84] | |

| Photo-therapy | Narrowband ultraviolet B (NB-UVB) | Reduces inflammation and slows the rapid growth of skin cells. Effective in treating moderate to severe plaque psoriasis with fewer side effects compared to broadband UVB. | [85] |

| Psoralen plus UVA (PUVA) | Effective for treating severe psoriasis, especially in cases resistant to other treatments. PUVA slows skin cell turnover and reduces scaling and inflammation. | [94] | |

| Excimer laser (Targeted UVB) | Specific targeting of psoriasis plaques with minimal off-target effects. Particularly useful for localized psoriasis, including scalp and nails. | [95] | |

| Cell therapy | MSCs | MSCs have been shown to reduce inflammation and modulate immune responses in psoriasis, leading to improved skin healing, reduced symptoms, and increased damaged tissue regeneration. | [88] |

| Adipose-derived MSCs (AD-MSCs) | AD-MSCs exhibit immunomodulatory properties, suppressing inflammatory cytokines such as IL-17 and TNF-α, leading to the improvement of psoriatic lesions and a reduction in disease severity. | [87] | |

| Human umbilical cord MSCs (hUC-MSCs) | hUC-MSCs have shown efficacy in reducing inflammation and promoting tissue repair, specifically by reducing IL-17-producing γδ T cells and modulating the immune response to alleviate psoriasis symptoms. | [86] | |

| MSC-Exo | MSC-Exo attenuates inflammation and promotes tissue regeneration by modulating immune responses through decreasing proinflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and IL-17. | [89] | |

| Adipose-derived stem cell exosomes (ASC-Exo) | ASC-Exo reduces psoriatic lesions and improves skin barrier function. ASC-Exo have shown efficacy in reducing hyperpigmentation and improving overall skin health. | [90] | |

| Other | Changing diet manner | Choosing a specific form of balanced diet (plant-based) could help to reduce overweight in patients with psoriasis and their severity. | [79] |

| Cytokine | Type of MSC | Preclinical Model | Therapeutic and Immunomodulatory Effects | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFN-γ | Bone marrow MSCs (BM-MSCs) | Solid organ transplantation models | IFN-γ primes MSCs to enhance immunosuppressive properties by upregulating IDO and iNOS expression, leading to suppression of T-cell proliferation. | [107] |

| Human MSCs (hMSCs) | Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) models | Enhances MSC-mediated immunosuppression and improves outcomes in GVHD by increasing programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression. | [108] | |

| TNF-α | hMSCs | Myocardial infarction in rats | Enhances the therapeutic efficacy of MSCs by promoting NO production and reducing apoptosis, thereby improving heart function. | [109] |

| IL-1β | hMSCs | Inflammatory models in vitro | IL-1β primes MSCs to secrete anti-inflammatory mediators like PGE2, enhancing their immunomodulatory functions. | [110] |

| IL-2 | hMSCs | Cancer immunotherapy models | IL-2 priming enhances MSCs’ ability to inhibit NK cell proliferation and promote Tregs’ differentiation, leading to improved immunosuppression. | [111] |

| IL-17 + TNF-α | BM-MSCs | Autoimmune encephalomyelitis in mice | The combination of IL-17 and TNF-α significantly enhances the immunosuppressive effects of MSCs, leading to reduced inflammation and better control of autoimmune responses. | [112] |

| TGF-β | hMSCs | Cecal ligation and puncture (CLP)-induced sepsis in mice | Attenuation of histopathological damage to the organ, reduction in the level of proinflammatory cytokines, and inhibition of macrophage infiltration into tissues. | [113] |

| BM-MSCs | Bone metabolism and tissue regeneration | Promotes osteoblast differentiation, bone remodeling, and tissue regeneration. | [114] | |

| HGF | BM-MSCs | Spinal cord injury in rats | Promotes recovery by reducing inflammation and enhancing nerve regeneration. | [115] |

| Gene-modified MSCs | Ischemia/reperfusion-induced acute lung injury in rats | Reduction in lung injury, and improvement of cell survival and tissue repair through anti-apoptotic effect. | [116] | |

| PGE2 | BM-MSCs | LPS-induced acute lung injury (ALI) in mice | Enhancement of the protective effects of MSCs by modulating macrophage polarization, reducing inflammation, and improving lung function. | [117] |

| Human-embryonic-stem-cell- derived MSCs | Liver fibrosis in mouse models | Reduces liver fibrosis through immunosuppressive mechanisms and regulation of T-cell function. | [118] | |

| IDO | BM-MSCs | Heart allograft rejection in rats | Suppresses heart allograft rejection by increasing the production and activity of DCs and Tregs. | [119] |

| hUC-MSCs | Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) in rats | Enhances cardiac function and survival by upregulating IDO expression, which modulates immune response and reduces inflammation. | [120] | |

| iNOS | BM-MSCs | Systemic sclerosis (SSc) in mice | iNOS activity is crucial for the anti-fibrotic effects of MSCs, reducing skin thickness and collagen deposition. | [121] |

| hMSCs | Myocardial infarction in rats | Enhances survival and paracrine function of MSCs, leading to reduced apoptosis and improved heart function. | [109] |

| Psoriasis Model | Animals, Age | Source and Tissue Origin of MSCs | Route of Administration/ Number of Repetitions | Dosage | Mechanism of Action | Therapeutic Outcome | Reference |

| IMQ-induced psoriasis-like skin inflammation | C57BL/6 mice, 8 weeks | Human-umbilical-cord-blood- derived MSCs (hUCB- MSC) | Subcutaneous injection, 2 times (24 h before and at day 6 of IMQ application) | 2 × 106 cells | MSCs overexpress SOD3, to prevent the severity and progression of psoriasis through the regulation of immune cell infiltration and functions, specifically DCs, neutrophils, and Th17 cells, and by regulating epidermal functions, TLR-7-dependent and independent pathways, MAP kinases, and JAK-STAT pathways, which augment the inflammatory actions. | Immunomodulatory effect, reducing the thickness of the epidermis and inhibiting the infiltrations of various immune cells into the skin, spleen, and lymph nodes. | [129] |

| IMQ-induced psoriasis-like skin inflammation IL-23-mediated psoriasis-like skin inflammation | C57/BL mice, male, 8–12 weeks | hUCB- MSCs | Subcutaneous injection, 24 h before IMQ application Subcutaneous injection, near the ear—2 times (24 h before and day 7) Subcutaneous injection (back skin)—2 times (on days 7 and 13) | 2 × 106 cells (per injection) | hUCB-MSCs inhibit proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine gene expression and suppress Th17 cell differentiation. MSCs prevent the infiltration of immune cells (CD4+ T cells, CD11b+ cells, and CD11c+ cells) into the skin and inhibit the expression of proinflammatory (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-17, IL-22, IL-20, TNF-α) and chemokine genes in the skin. | Anti- inflammatory effect and regulatory effect on immune cells. | [134] |

| IMQ-induced psoriasis-like skin inflammation | C57BL/6 mice, female, 8 weeks | T-MSC | Intravenous administration, 2 times (on days 1 and 3 of the IMQ application period) | 1 × 106 cells | T-MSCs induce a blockade of PD-L1, which leads to downregulation in gene expression of IL-23, TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-17, IL-22, K6, K16, and CCL20. | Immunosuppressive effect. | [135] |

| IMQ-induced psoriasis-like skin inflammation | BALB/c mice, female, 8 weeks | hUC- MSCs | Intravenous administration after 6 consecutive days of IMQ application | 1 × 106 cells | MSCs infusion inhibited the infiltration of immune cells, T cells (CD3+ cells), neutrophils (Gr-1+ cells), and IL-17+ cells into the skin. MSCs reduce the expression level of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-17, IL-23, IL-6, and IL-1β) and keratinocyte differentiation markers (S100A7, S100A8, and S100A9) and also increase the expression level of anti- inflammatory cytokine IL-10. | Immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory effects. | [136] |

| IMQ-induced psoriasis like skin inflammation | C57BL/6J mice | hAMSC | Injection into each mouse ear | 5 × 105 cells | hAMSC alleviates the keratinocyte response to proinflammatory cytokines IL-17A and IL-22 and chemokine CXCL1. | Immunomodulatory effect. | [137] |

| IMQ-induced psoriasis-like skin inflammation | BALB/c mice, male, 6–9 weeks | MSC-Exo | Daily topical application on day 3 and for a total of 3 or 7 days (two experiments using different batches of exosomes) | 100 μg/mL, 200 μL per mouse | Topically applied MSC-Exo reduce the proinflammatory cytokines (IL-17, IL-23) and inhibit C5b-9 activation through CD59 in the stratum corneum. | Anti-inflammatory effect. | [138] |

| IMQ-induced psoriasis-like skin inflammation | C57BL/6 mice, 8 weeks | hUC-MSC-derived exosomes (hUC-MSC-Exo) | Subcutaneous injection | 50 μg per mouse | hUC-MSCs-Exo suppress the expression of IL-17, IL-23, and CCL20, thereby inhibiting the phosphorylation of STAT3. | Immunomodulatory effect. Reduction in psoriatic erythema, scaling, thickening, inflammatory infiltration, and inhibition of epidermal hyperplasia. | [131] |

| IMQ-induced psoriasis-like skin inflammation | - | ASCs | Intradermal injections into the dorsal areas, 3 times (on days 0, 3, and 4) | 1 × 106 cells | ASCs inhibit the production of Th17-associated cytokines, such as IL-17A and TNF-a. | Immunosuppressive effect. | [139] |

| IMQ-induced psoriasis-like skin inflammation | C57BL/6 mice, female, 6–8 weeks | MSC-Exo-PD-L1 | Intravenous administration, 4 days | 50 μg per mouse | MSC-Exo-PD-L1 restore tissue lesions by inhibition the inflammatory immune cells via the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway. | Anti-inflammatory effect and regulatory effect on immune cells. | [140] |

| IMQ-induced psoriasis-like skin inflammation | C57BL/6 mice, 6–8 weeks | hUC-MSCs | Intravenous (one day before the first IMQ application) or subcutaneous (three times: 1 day before, 2 days after, and 4 days after the first application of IMQ) administration | 5 doses (0.5; 1; 2; 5 or 10 × 106 cells) | hUC-MSCs suppress skin inflammation by inhibiting γδ T cells producing IL-17. | Significant reduction in the severity of psoriasis-like dermatitis and suppression of the inflammatory response of cells. | [86] |

| IMQ-induced psoriasis-like skin inflammation | C57Bl/6 J mice, female, 7–9 weeks | hUC-MSCs | Intravenous administration, 5 days | 4 × 105 cells in 200 μL PBS | hUC-MSCs inhibit TNF-α production by monocytes and macrophages, which in turn prevents keratinocyte proliferation induced by the TNF-α/NF-κB/MMP13 axis. | Significant reduction in epidermal thickening and excessive keratinocyte proliferation. | [141] |

| IMQ-induced psoriasis-like skin inflammation | C57BL/6 mice, female, 7 weeks | BM-MSCs or AD-MSCs | Intravenous administration after 4 days of IMQ application | 1 × 106 cells/mouse in 100 μL of PBS | BM- or AD-MSCs improve skin repair by increasing the levels of IL-17A and TGF-β, and TGF-β promotes controlled differentiation of keratinocytes. | Accelerated healing process and reduction in severity of psoriasis. | [142] |

| IMQ-induced psoriasis-like skin inflammation | C57BL/6 mice, 8–12 weeks | UCB-MNC-Exo | Topical application, one hour after each imiquimod application for 6 days | 3 × 109 particles/cm2 UCB-MNC-sEV dissolved in hydrogel | UCB-MNC-Exo increases the number of Tregs in the skin. | Reduction in acanthosis, and prevention of keratinocyte hyperproliferation. | [132] |

| IMQ-induced psoriasis-like skin inflammation | Albino rats, male | hUC-MSCs | Subcutaneous injections at the four corners around the edge of the inflamed area of the skin, after 6 days of IMQ application | 2 × 106 cells per injection within 2 mL of the media | MSCs regulate immune cell infiltration (Th17 cells), epidermal functions, and differentiation. | Immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory effects. | [143] |

| Disease | Source of MSCs | N (M, F) | Age 1 (M, F) | Dosage | Adverse Effects | Results | Reference |

| Psoriasis vulgaris | Allogeneic hUC-MSCs | 1M, 1F | 35, 26 | 2–3 IV infusions at a dose of 1 × 106 cells/kg | Not observed | Remained relapse-free for 4–5 years | [144] |

| Plaque psoriasis | Allogeneic hGMSCs | 1M | 19 | 5 IV infusions at a dose of 3 × 106 cells/kg | Not observed | Remained disease-free for 3 years | [145] |

| Psoriasis vulgaris and arthritis | Autologous hAD-MSCs | 1M, 1F | 58, 28 | PV—3 IV infusions (2.36 × 106 cells/kg) PA—2 IV infusions (5.3 × 105 cells/kg) | Not observed | PV—decreased PASI for 292 days PA—remained relapse-free for 2 years | [146] |

| Psoriasis vulgaris | Allogeneic hAD-MSCs | 6M, 1F | 50.71 ± 10.45 | 3 IV infusions at a dose of 0.5 × 106 cells/kg | Mild or moderate AEs | PASI-50 in two patients with no additional treatment | [87] |

| Plaque psoriasis | Allogeneic hAD-MSCs | 3M, 2F | 32.8 ± 8.18 | Subcutaneous injection at a dose of 1–3 × 106 cells/cm2 | Mild burning and pain in some patients | Decreased PASI after 6 months | [147] |

| Severe psoriasis | Autologous SVF, hAD-MSCs | 1M | 43 | IV infusion of around 30–60 × 106 cells | Not observed | PASI dropped from 50.4 to 0.3 in a month, sustained for a year | [148] |

| Psoriasis vulgaris | MSC-CM | 1M | 38 | Daily topical application for one month | Not observed | PSSI dropped from 28 to 0 in a month, sustained for 6 months | [149] |

| Psoriasis vulgaris | Allogeneic hUC-MSCs | 8M, 9F | 40.76 ± 8.85 | 4 IV infusions at a dose between 1.5 and 3.0 × 106 cells/kg | Mild adverse effects all resolved within a day | PASI improvements in all patients; one patient with PASI-50 for almost 3 years | [150] |

| Psoriasis | UC-MSCs | 1M | 12 | N/A | No complications during the follow-up | Complete remission of psoriasis lesions by day 7 | [151] |

| Plaque psoriasis | hAD- MSC-Exo | 7M, 3F | 36.6 ± 8.07 | 200 µg MSC-Exo | No adverse effects observed | Reduced erythema, induration, and lesion thickness | [152] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dairov, A.; Sekenova, A.; Alimbek, S.; Nurkina, A.; Shakhatbayev, M.; Kumasheva, V.; Kuanysh, S.; Adish, Z.; Issabekova, A.; Ogay, V. Psoriasis: The Versatility of Mesenchymal Stem Cell and Exosome Therapies. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1351. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom14111351

Dairov A, Sekenova A, Alimbek S, Nurkina A, Shakhatbayev M, Kumasheva V, Kuanysh S, Adish Z, Issabekova A, Ogay V. Psoriasis: The Versatility of Mesenchymal Stem Cell and Exosome Therapies. Biomolecules. 2024; 14(11):1351. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom14111351

Chicago/Turabian StyleDairov, Aidar, Aliya Sekenova, Symbat Alimbek, Assiya Nurkina, Miras Shakhatbayev, Venera Kumasheva, Sandugash Kuanysh, Zhansaya Adish, Assel Issabekova, and Vyacheslav Ogay. 2024. "Psoriasis: The Versatility of Mesenchymal Stem Cell and Exosome Therapies" Biomolecules 14, no. 11: 1351. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom14111351

APA StyleDairov, A., Sekenova, A., Alimbek, S., Nurkina, A., Shakhatbayev, M., Kumasheva, V., Kuanysh, S., Adish, Z., Issabekova, A., & Ogay, V. (2024). Psoriasis: The Versatility of Mesenchymal Stem Cell and Exosome Therapies. Biomolecules, 14(11), 1351. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom14111351