Bioactivity and In Silico Studies of Isoquinoline and Related Alkaloids as Promising Antiviral Agents: An Insight

Abstract

1. Introduction

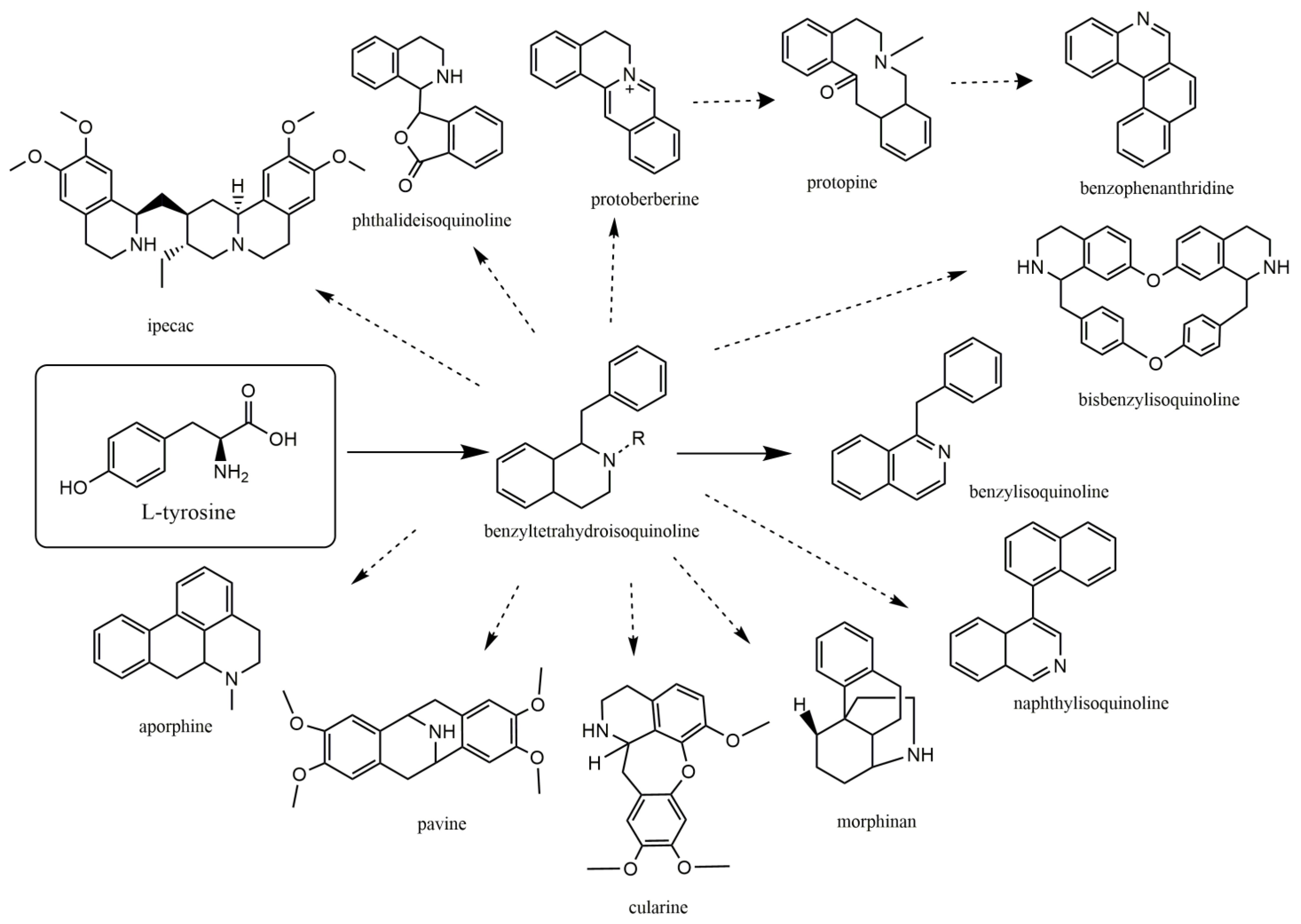

2. Isoquinoline and Related Alkaloids: A New Ray of Hope

3. Therapeutic Targets for SARS-CoV-2 Inhibition: In Silico Approaches

3.1. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme-2 (ACE2) and Spike(S) Protein

3.2. Main Protease (Mpro) or 3-Chemotrypsin-like Protease (3CLpro)

3.3. RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase (RdRp)

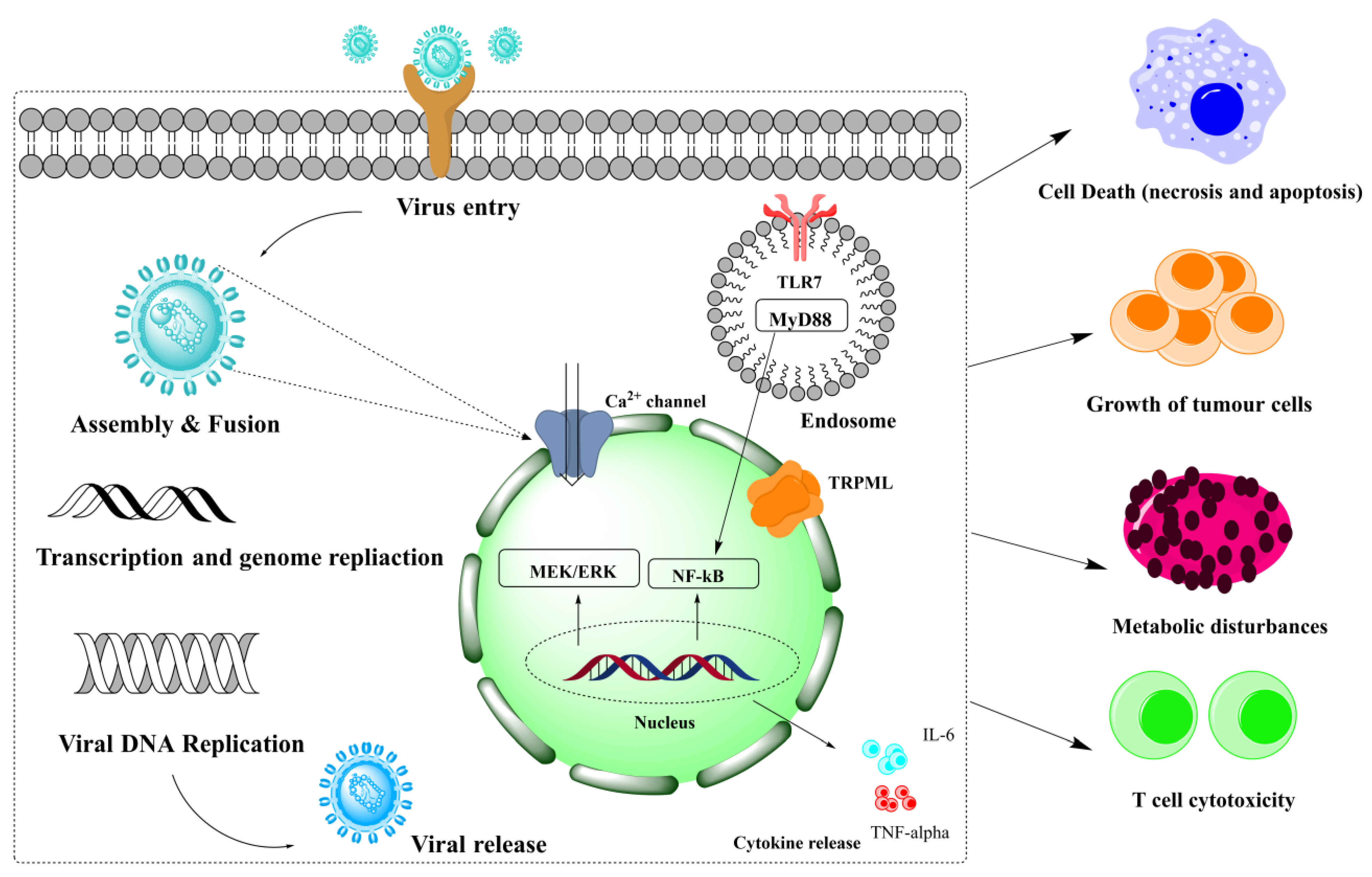

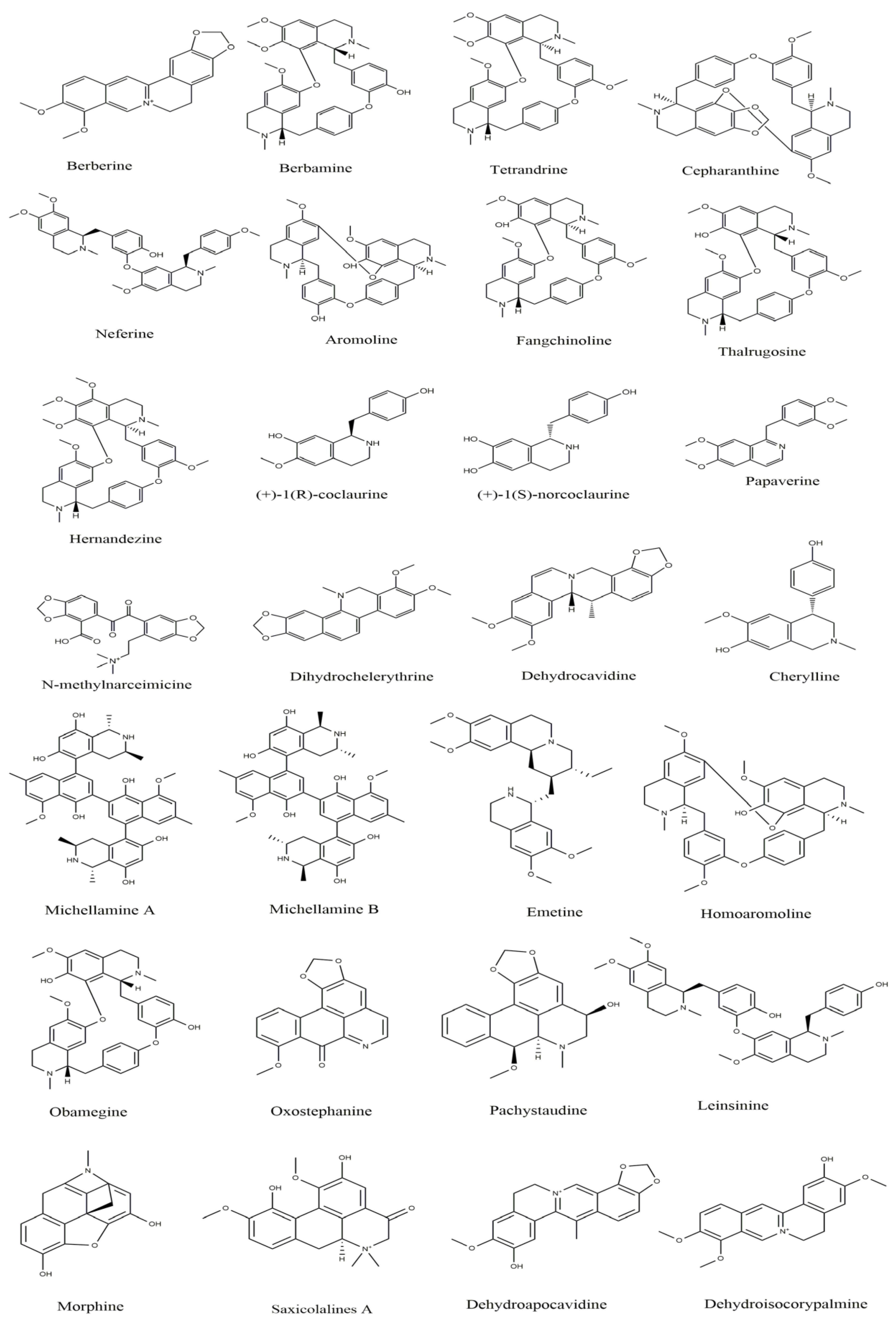

4. Antiviral Actions of Isoquinoline Related Alkaloids

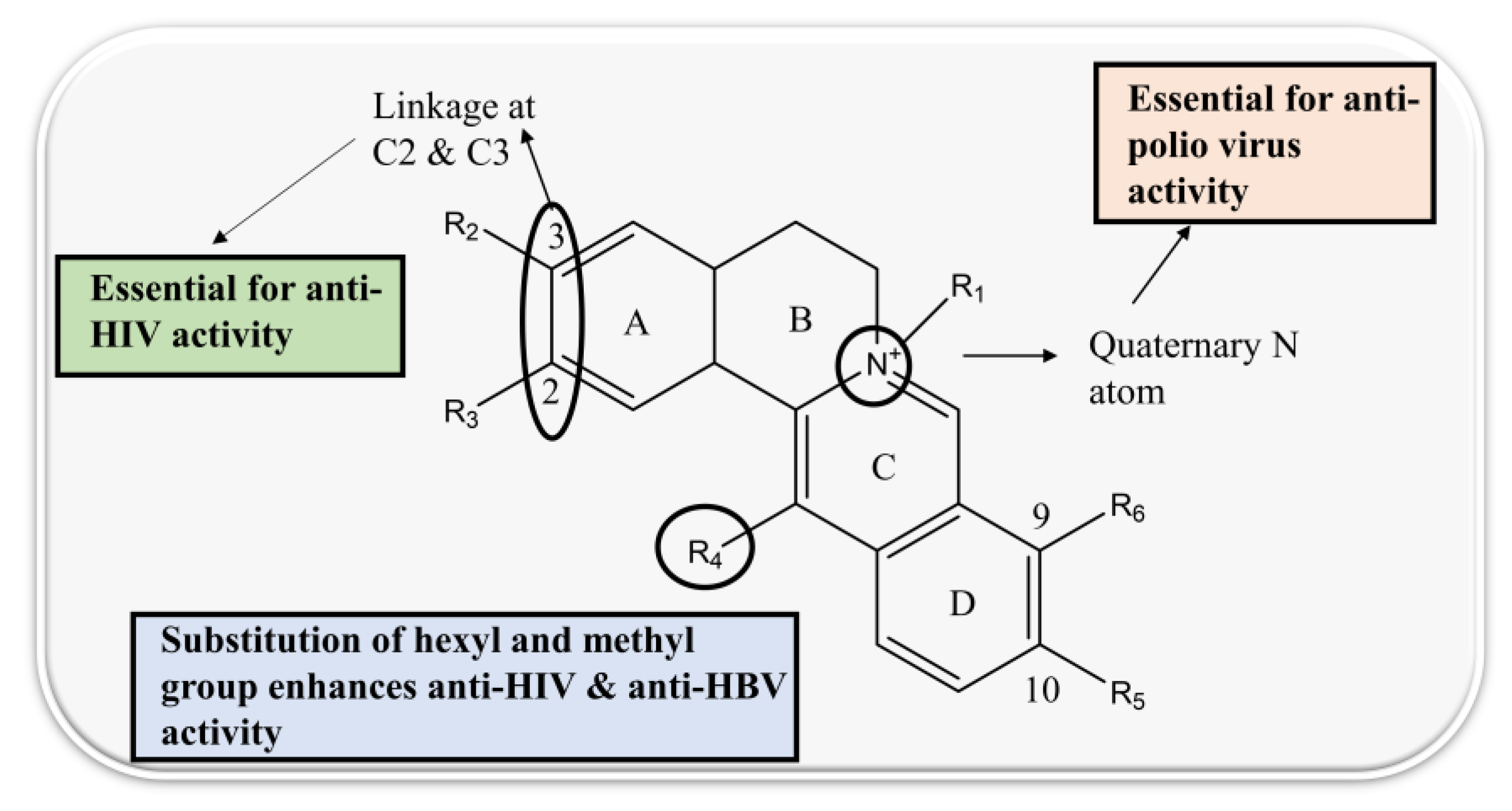

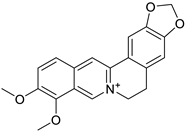

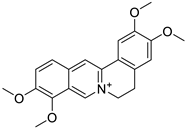

4.1. Protoberberine Alkaloids

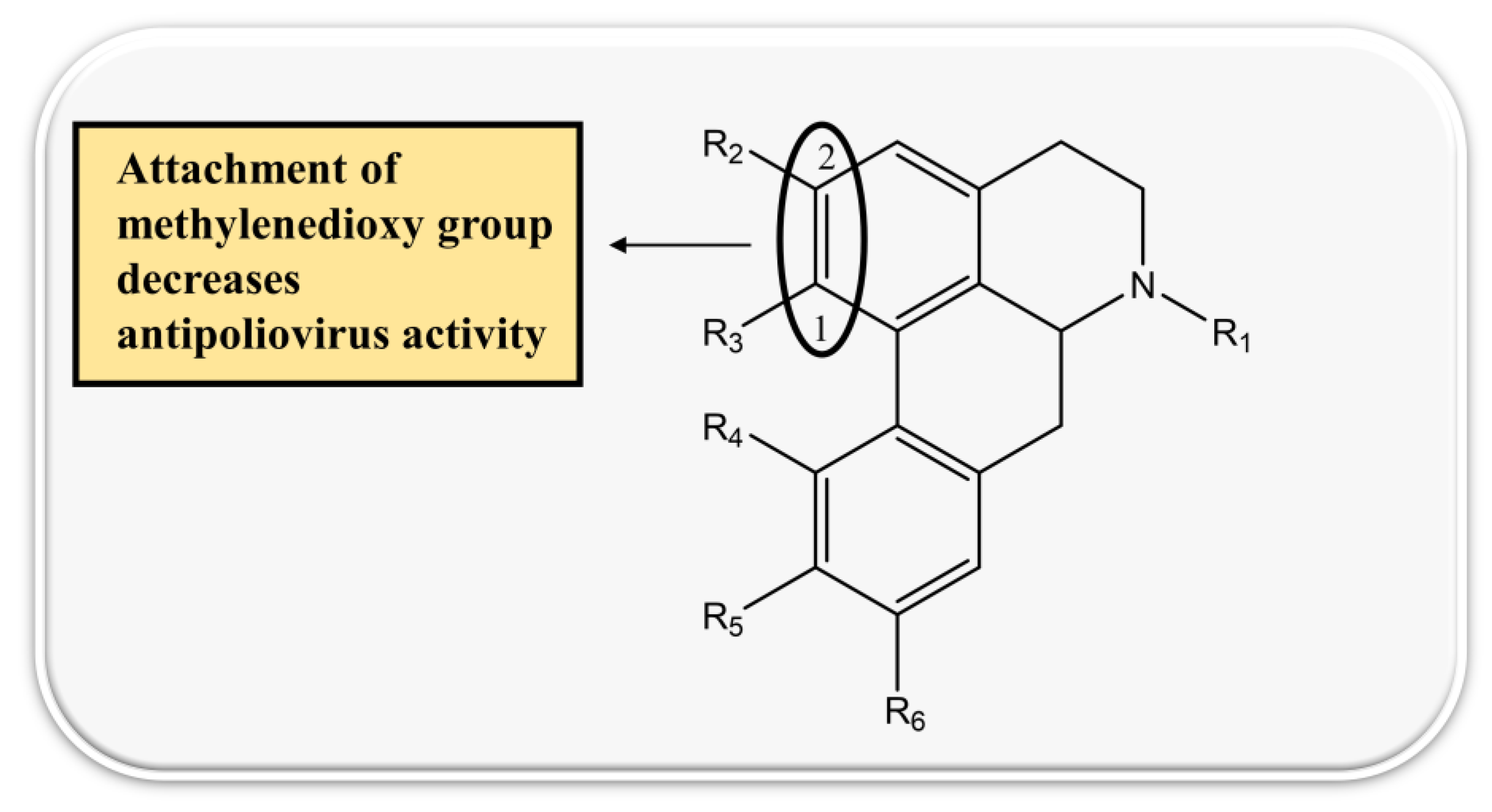

4.2. Aporphine Alkaloids

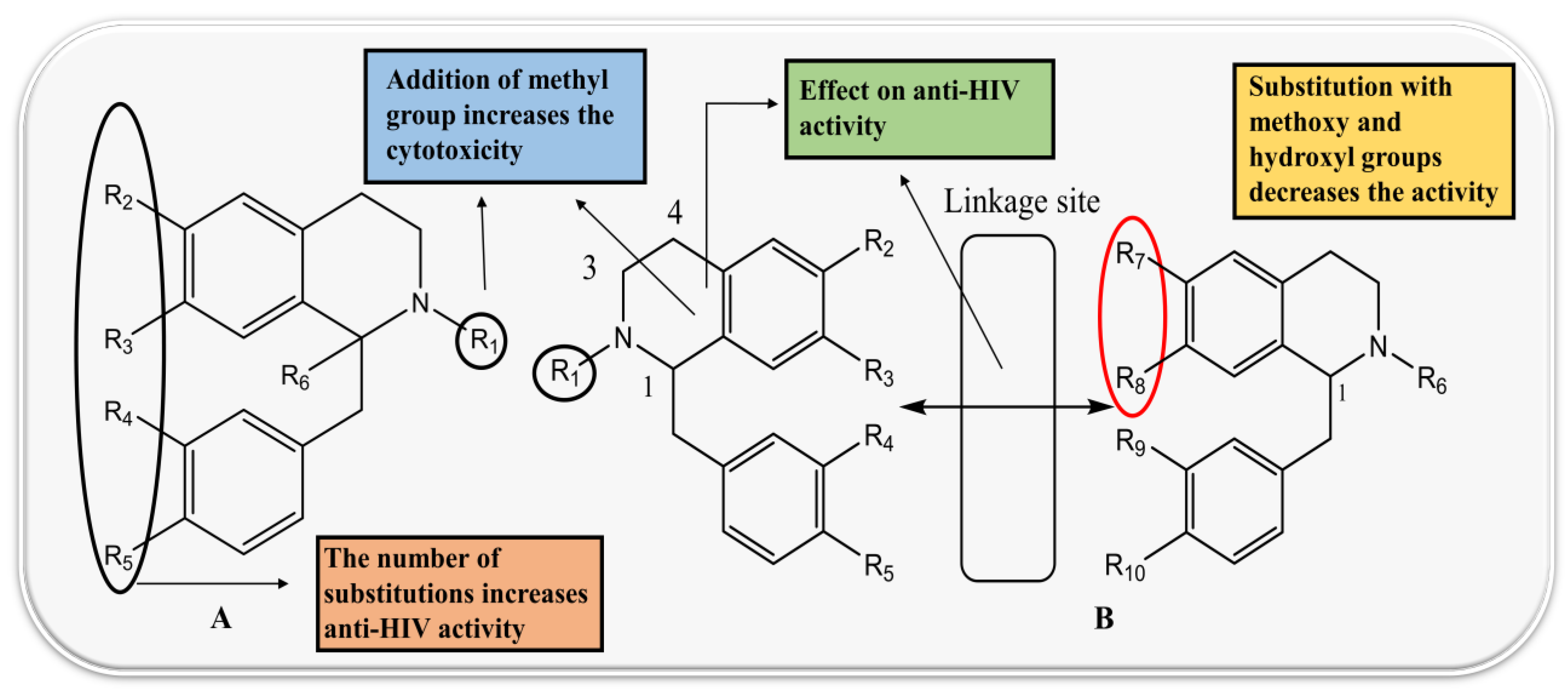

4.3. Benzyltetrahydroisoquinoline and Benzylisoquinoline

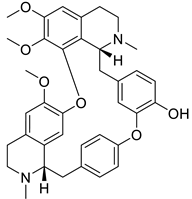

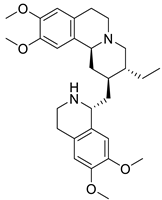

4.4. Bisbenzylisoquinoline (BBI)

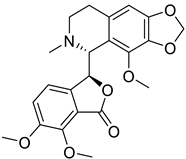

4.5. Ipecac Alkaloids

4.6. Naphythylisoquinoline Alkaloids

4.7. Pavine Alkaloids

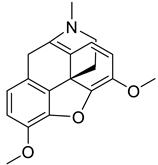

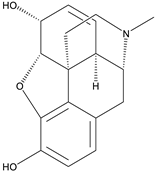

4.8. Morphinan and Promorphinan Alkaloids

4.9. Benzophenanthridines

5. Inflammation Inhibition

6. Clinical Findings

7. Conclusions and Future Perspective

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Caldaria, A.; Conforti, C.; Di Meo, N.; Dianzani, C.; Jafferany, M.; Lotti, T.; Zalaudek, I.; Giuffrida, R. COVID-19 and SARS: Differences and similarities. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 33, e13395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabaan, A.A.; Al-Ahmed, S.H.; Haque, S.; Sah, R.; Tiwari, R.; Malik, Y.S.; Dhama, K.; Yatoo, M.I.; Bonilla-Aldana, D.K.; Rodriguez-Morales, A.J. SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-COV: A comparative overview. Infez Med 2020, 28, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Boon, S.S.; Wang, M.H.; Chan, R.W.Y.; Chan, P.K.S. Genomic and evolutionary comparison between SARS-CoV-2 and other human coronaviruses. J. Virol. Methods 2021, 289, 114032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hiv-aids#:~:text=HIV%20continues%20to%20be%20a,no%20cure%20for%20HIV%20infection (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-b#:~:text=HBV%2DHIV%20coinfection&text=Conversely%2C%20the%20global%20prevalence%20of,%2Dinfected%20persons%20is%207.4%25 (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- Ball, M.J.; Lukiw, W.J.; Kammerman, E.M.; Hill, J.M. Intracerebral propagation of Alzheimer’s disease: Strengthening evidence of a herpes simplex virus etiology. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2013, 9, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hober, D.; Sane, F.; Jaidane, H.; Riedweg, K.; Goffard, A.; Desailloud, R. Immunology in the clinic review series; focus on type 1 diabetes and viruses: Role of antibodies enhancing the infection with Coxsackievirus-B in the pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2012, 168, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.L.; Baack, B.; Smith, B.D.; Yartel, A.; Pitasi, M.; Falck-Ytter, Y. Eradication of hepatitis C virus infection and the development of hepatocellular carcinoma: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann. Intern. Med. 2013, 158 Pt 1, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharb, R.; Shahar Yar, M.; Sharma, P.C. Recent advances and future perspectives of triazole analogs as promising antiviral agents. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2011, 11, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, A.L.; Bezerra, L.P.; Shawar, D.E.; Neto, N.A.; Mesquita, F.P.; Silva, G.O.D.; Souza, P.F. Synthetic antiviral peptides: A new way to develop targeted antiviral drugs. Future Virol. 2022, 17, 577–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serban, G. Synthetic Compounds with 2-Amino-1,3,4-Thiadiazole Moiety Against Viral Infections. Molecules 2020, 25, 942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ling, L.; Zhang, Z.; Marin-Lopez, A. Current Advances in Zika Vaccine Development. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burki, T. The origin of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 174–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nováková, L.; Pavlík, J.; Chrenková, L.; Martinec, O.; Červený, L. Current antiviral drugs and their analysis in biological materials–Part II: Antivirals against hepatitis and HIV viruses. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2018, 147, 378–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganjhu, R.K.; Mudgal, P.P.; Maity, H.; Dowarha, D.; Devadiga, S.; Nag, S.; Arunkumar, G. Herbal plants and plant preparations as remedial approach for viral diseases. Virus Dis. 2015, 26, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitazato, K.; Wang, Y.; Kobayashi, N. Viral infectious disease and natural products with antiviral activity. Drug Discov. 2007, 1, 14–22. [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari, B.; Marasini, B.P.; Rayamajhee, B.; Bhattarai, B.R.; Lamichhane, G.; Khadayat, K.; Adhikari, A.; Khanal, S.; Parajuli, N. Potential roles of medicinal plants for the treatment of viral diseases focusing on COVID-19: A review. Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 1298–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Conlon, M.; Ren, W.; Chen, B.B.; Bączek, T. Natural Products as Targeted Modulators of the Immune System. J. Immunol. Res. 2018, 2018, 7862782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, K.; Kohli, S.K.; Kaur, R.; Bhardwaj, A.; Bhardwaj, V.; Ohri, P.; Sharma, A.; Ahmad, A.; Bhardwaj, R.; Ahmad, P. Herbal immune-boosters: Substantial warriors of pandemic Covid-19 battle. Phytomed. Int. J. Phytother. Phytopharm. 2021, 85, 153361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.C.; Sharma, O.; Vasudeva, N.; Mishra, D.; Singh, S. Anti-HIV substances of natural origin–An updated account. Nat. Prod. Radiance 2006, 70–78. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, B.; Sharma, S.; Nair, N.; Majeed, J.; Goyal, R.K.; Dhobi, M. Therapeutic opportunities of edible antiviral plants for COVID-19. Mol Cell Biochem 2021, 476, 2345–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrityunjaya, M.; Pavithra, V.; Neelam, R.; Janhavi, P.; Halami, P.; Ravindra, P. Immune-boosting, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory food supplements targeting pathogenesis of COVID-19. Front. Immunol. 2020, 2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.-H.; Wu, K.-L.; Zhang, X.; Deng, S.-Q.; Peng, B. In silico screening of Chinese herbal medicines with the potential to directly inhibit 2019 novel coronavirus. J. Integr. Med. 2020, 18, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omrani, M.; Keshavarz, M.; Nejad Ebrahimi, S.; Mehrabi, M.; Mcgaw, L.J.; Ali Abdalla, M.; Mehrbod, P. Potential Natural Products Against Respiratory Viruses: A Perspective to Develop Anti-COVID-19 Medicines. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erika, P.; Avila M, M.C.; Muñoz, D.R.; Cuca S, L.E. Natural isoquinoline alkaloids: Pharmacological features and multi-target potential for complex diseases. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 177, 106126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, Z.-X.; Yang, P.; Tang, Q.; Cheng, P.; Liu, X.-B.; Zheng, Y.-J.; Liu, Y.-S.; Zeng, J.-G. Isoquinoline Alkaloids and Their Antiviral, Antibacterial, and Antifungal Activities and Structure-activity Relationship. Curr. Org. Chem. 2017, 21, 1920–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warowicka, A.; Nawrot, R.; Goździcka-Józefiak, A. Antiviral activity of berberine. Arch. Virol. 2020, 165, 1935–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souto, A.L.; Tavares, J.F.; Da Silva, M.S.; Diniz, M.D.F.F.M.; De Athayde-Filho, P.F.; Barbosa Filho, J.M. Anti-inflammatory activity of alkaloids: An update from 2000 to 2010. Molecules 2011, 16, 8515–8534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bribi, N. Pharmacological activity of Alkaloids: A Review. Asian J. Bot. 2018, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, C.; Lv, L.; Gao, B.; Li, M. Research Progress on Antibacterial Activities and Mechanisms of Natural Alkaloids: A Review. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, A.; Gandhi, A.; Fimognari, C.; Atanasov, A.G.; Bishayee, A. Alkaloids for cancer prevention and therapy: Current progress and future perspectives. Eur. J. Pharm. 2019, 858, 172472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.; Mubarak, M.S.; Amin, S. Antifungal Potential of Alkaloids As An Emerging Therapeutic Target. Curr Drug Targets 2017, 18, 1825–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnsworth, N.R.; Svoboda, G.H.; Blomster, R.N. Antiviral Activity of Selected Catharanthus Alkaloids. J. Pharm. Sci. 1968, 57, 2174–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renard-Nozaki, J.; Kim, T.; Imakura, Y.; Kihara, M.; Kobayashi, S. Effect of alkaloids isolated from Amaryllidaceae on herpes simplex virus. Res. Virol. 1989, 140, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topcu, G.S.H.; Toraman, G.O.A.; Altan, V.M. Natural alkaloids as potential anti-coronavirus compounds. (Special Issue: Therapeutic options and potential vaccine studies against COVID-19. Bezmialem Sci. 2020, 8, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramawat, K.G. Biodiversity and Chemotaxonomy; Sustainable Development and Biodiversity; Ramawat, K.G., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; Volume 24. [Google Scholar]

- Santoro, D.; Bellinghieri, G.; Savica, V. Development of the concept of pain in history. J. Nephrol. 2011, 24 (Suppl. 17), S133–S136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kukula-Koch, W.A.; Widelski, J. Chapter 9—Alkaloids, Pharmacognosy; Badal, S., Delgoda, R., Eds.; Academic Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 163–198. [Google Scholar]

- Qing, Z.; Xu, Y.; Yu, L.; Liu, J.; Huang, X.; Tang, Z.; Cheng, P.; Zeng, J. Investigation of fragmentation behaviours of isoquinoline alkaloids by mass spectrometry combined with computational chemistry. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, Z.-X.; Huang, J.-L.; Yang, X.-Y.; Liu, J.-H.; Cao, H.-L.; Xiang, F.; Cheng, P.; Zeng, J.-G. Anticancer and Reversing Multidrug Resistance Activities of Natural Isoquinoline Alkaloids and their Structure-activity Relationship. Curr. Med. Chem. 2018, 25, 5088–5114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, X.-F.; Yang, C.-J.; Morris-Natschke, S.L.; Li, J.-C.; Yin, X.-D.; Liu, Y.-Q.; Guo, X.; Peng, J.-W.; Goto, M.; Zhang, J.-Y.; et al. Biologically active isoquinoline alkaloids covering 2014–2018. Med. Res. Rev. 2020, 40, 2212–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, B.C.; Da Silva Maia Bezerra Filho, C.; Ismail, N.S.M.; Sousa, D.P.D. Alkaloids: Therapeutic Potential against Human Coronaviruses. Molecules 2020, 25, 5496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majnooni, M.B.; Fakhri, S.; Bahrami, G.; Naseri, M.; Farzaei, M.H.; Echeverría, J. Alkaloids as Potential Phytochemicals against SARS-CoV-2: Approaches to the Associated Pivotal Mechanisms. Evid. -Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2021, 2021, 6632623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abookleesh, F.L.; Al-Anzi, B.S.; Ullah, A. Potential Antiviral Action of Alkaloids. Molecules 2022, 27, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, R.K.; Majeed, J.; Tonk, R.; Dhobi, M.; Patel, B.; Sharma, K.; Apparsundaram, S. Current targets and drug candidates for prevention and treatment of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) infection. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 21, 365–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurya, V.K.; Kumar, S.; Prasad, A.K.; Bhatt, M.L.; Saxena, S.K. Structure-based drug designing for potential antiviral activity of selected natural products from Ayurveda against SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein and its cellular receptor. Virusdisease 2020, 31, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, P. In silico investigation of phytoconstituents from Indian medicinal herb ‘Tinospora cordifolia (giloy)’against SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) by molecular dynamics approach. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021, 39, 6792–6809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, T.; Bhat, S.; Pundir, H.; Chandra, S. Identification of Berbamine, Oxyacanthine and Rutin from Berberis asiatica as anti-SARS-CoV-2 compounds: An in silico study. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2021, 109, 108028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, N.; Sood, D.; Van Der Spek, P.J.; Sharma, H.S.; Chandra, R. Molecular binding mechanism and pharmacology comparative analysis of noscapine for repurposing against SARS-CoV-2 protease. J. Proteome Res. 2020, 19, 4678–4689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jadhav, V.; Ingle, S.; Ahmed, R. Inhibitory activity of palmatine on main protease complex (mpro) of SARS-CoV-2. Rom. J. Biophys. 2021, 31, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Shen, X.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, Y. Discovery of Anti-2019-nCoV Agents from 38 Chinese Patent Drugs toward Respiratory Diseases via Docking Screening. Preprints 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, D.; Hossain, R.; Khan, R.; Dey, D.; Toma, T.R.; Islam, M.; Pracheta, D.; Khalid, R.; Hakeem, K. Computer-aided Evaluation of Anti-SARS-CoV-2 (3-chymotrypsin-like Protease and Transmembrane Protease Serine 2 Inhibitors) Activity of Cepharanthine: An In silico Approach. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2021, 12, 768–780. [Google Scholar]

- Byler, K.G.; Ogungbe, I.V.; Setzer, W.N. Setzer In-silico screening for anti-Zika virus phytochemicals. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2016, 69, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, M.; Miroliaei, M. Inhibitory effects of selected isoquinoline alkaloids against main protease (Mpro) of SARS-CoV-2, in silico study. Silico Pharmacol. 2022, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, S.; Roy, A. In silico analysis of selected alkaloids against main protease (Mpro) of SARS-CoV-2. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2020, 332, 109309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogosnitzky, M.; Okediji, P.; Koman, I. Cepharanthine: A review of the antiviral potential of a Japanese-approved alopecia drug in COVID-19. Pharmacol. Rep. 2020, 72, 1509–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hijikata, A.; Shionyu-Mitsuyama, C.; Nakae, S.; Shionyu, M.; Ota, M.; Kanaya, S.; Hirokawa, T.; Nakajima, S.; Watashi, K.; Shirai, T. Evaluating cepharanthine analogues as natural drugs against SARS-CoV-2. FEBS Open Bio 2022, 12, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, D.; Kumari, K.; Jayaraj, A.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, R.V.; Dass, S.K.; Chandra, R.; Singh, P. Understanding the binding affinity of noscapines with protease of SARS-CoV-2 for COVID-19 using MD simulations at different temperatures. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021, 39, 2659–2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Jain, N.K.; Kumar, N.; Kulkarni, G.T. Molecular docking study to identify a potential inhibitor of covid-19 main protease enzyme: An in-silico approach. ChemRxiv 2020. Cambridge: Cambridge Open Engage; This content is a preprint and has not been peer-reviewed. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Qiu, M.; Chu, Y.; Chen, D.; Wang, X.; Su, A.; Wu, Z. Downregulation of cellular c-Jun N-terminal protein kinase and NF-κB activation by berberine may result in inhibition of herpes simplex virus replication. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 5068–5078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, W.; Liang, G.; Xiao, J.; Studer, E.J.; Hylemon, P.B.; Pandak, W.M., Jr.; Wang, G.; Li, X.; Zhou, H. Berberine Inhibits HIV Protease Inhibitor-Induced Inflammatory Response by Modulating ER Stress Signaling Pathways in Murine Macrophages. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.Z.; Li, K.; Maskey, A.R.; Huang, W.; Toutov, A.A.; Yang, N.; Srivastava, K.; Geliebter, J.; Tiwari, R.; Miao, M. A small molecule compound berberine as an orally active therapeutic candidate against COVID-19 and SARS: A computational and mechanistic study. FASEB J. 2021, 35, e21360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzorno, A.; Padey, B.; Dubois, J.; Julien, T.; Traversier, A.; Dulière, V.; Brun, P.; Lina, B.; Rosa-Calatrava, M.; Terrier, O. In vitro evaluation of antiviral activity of single and combined repurposable drugs against SARS-CoV-2. Antivir. Res. 2020, 181, 104878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghareeb, D.A.; Saleh, S.R.; Seadawy, M.G.; Nofal, M.S.; Abdulmalek, S.A.; Hassan, S.F.; Khedr, S.M.; Abdelwahab, M.G.; Sobhy, A.A.; Yassin, A.M. Nanoparticles of ZnO/Berberine complex contract COVID-19 and respiratory co-bacterial infection in addition to elimination of hydroxychloroquine toxicity. J. Pharm. Investig. 2021, 51, 735–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, F.S.; Van Woudenbergh, E.; Overheul, G.J.; Eleveld, M.J.; Kurver, L.; Van Heerbeek, N.; Van Laarhoven, A.; Miesen, P.; Den Hartog, G.; De Jonge, M.I. Berberine and obatoclax inhibit SARS-CoV-2 replication in primary human nasal epithelial cells in vitro. Viruses 2021, 13, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cecil, C.E.; Davis, J.M.; Cech, N.B.; Laster, S.M. Inhibition of H1N1 influenza A virus growth and induction of inflammatory mediators by the isoquinoline alkaloid berberine and extracts of goldenseal (Hydrastis canadensis). Int. Immunopharmacol. 2011, 11, 1706–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varghese, F.S.; Thaa, B.; Amrun, S.N.; Simarmata, D.; Rausalu, K.; Nyman, T.A.; Merits, A.; Mcinerney, G.M.; Ng, L.F.P.; Ahola, T. The Antiviral Alkaloid Berberine Reduces Chikungunya Virus-Induced Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Signaling. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 9743–9757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botwina, P.; Owczarek, K.; Rajfur, Z.; Ochman, M.; Urlik, M.; Nowakowska, M.; Szczubiałka, K.; Pyrc, K. Berberine hampers influenza a replication through inhibition of MAPK/ERK pathway. Viruses 2020, 12, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.Q.; Fu, Y.J.; Wu, S.; Qin, H.Q.; Zhen, X.; Song, B.M.; Weng, Y.S.; Wang, P.C.; Chen, X.Y.; Jiang, Z.Y. Anti-influenza activity of berberine improves prognosis by reducing viral replication in mice. Phytother. Res. 2018, 32, 2560–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luganini, A.; Mercorelli, B.; Messa, L.; Palù, G.; Gribaudo, G.; Loregian, A. The isoquinoline alkaloid berberine inhibits human cytomegalovirus replication by interfering with the viral Immediate Early-2 (IE2) protein transactivating activity. Antivir. Res. 2019, 164, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.R.; Ma, Y.B.; Zhao, Y.X.; Yao, S.Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, J.J. Two new quaternary alkaloids and anti-hepatitis B virus active constituents from Corydalis saxicola. Planta Med. 2007, 73, 787–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashiwada, Y.; Aoshima, A.; Ikeshiro, Y.; Chen, Y.-P.; Furukawa, H.; Itoigawa, M.; Fujioka, T.; Mihashi, K.; Cosentino, L.M.; Morris-Natschke, S.L. Anti-HIV benzylisoquinoline alkaloids and flavonoids from the leaves of Nelumbo nucifera, and structure–activity correlations with related alkaloids. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2005, 13, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tietjen, I.; Ntie-Kang, F.; Mwimanzi, P.; Onguéné, P.A.; Scull, M.A.; Idowu, T.O.; Ogundaini, A.O.; Meva’a, L.M.; Abegaz, B.M.; Rice, C.M. Screening of the Pan-African natural product library identifies ixoratannin A-2 and boldine as novel HIV-1 inhibitors. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0121099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boustie, J.; Stigliani, J.-L.; Montanha, J.; Amoros, M.; Payard, M.; Girre, L. Antipoliovirus structure− activity relationships of some aporphine alkaloids. J. Nat. Prod. 1998, 61, 480–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Han, C.; Song, X.; Chen, G.; Chen, J. Bioactive aporphine alkaloids from the stems of Dasymaschalon rostratum. Bioorganic Chem. 2019, 90, 103069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orhana, I.; Ozçelik, B.; Karaoğlu, T.; Sener, B. Antiviral and antimicrobial profiles of selected isoquinoline alkaloids from Fumaria and Corydalis species. Z. Nat. C J. Biosci. 2007, 62, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montanha, J.; Amoros, M.; Boustie, J.; Girre, L. Anti-herpes virus activity of aporphine alkaloids. Planta Med. 1995, 61, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellinger, B.; Bojkova, D.; Zaliani, A.; Cinatl, J.; Claussen, C.; Westhaus, S.; Keminer, O.; Reinshagen, J.; Kuzikov, M.; Wolf, M. A SARS-CoV-2 cytopathicity dataset generated by high-content screening of a large drug repurposing collection. Sci. Data 2021, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nokta, M.; Albrecht, T.; Pollard, R. Papaverine hydrochloride: Effects on HIV replication and T-lymphocyte cell function. Immunopharmacology 1993, 26, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.M.; Nakamura, N.; Miyashiro, H.; Hattori, M.; Komatsu, K.; Kawahata, T.; Otake, T. Screening of Chinese and Mongolian herbal drugs for anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) activity. Phytother. Res. 2002, 16, 186–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otshudi, A.L.; Apers, S.; Pieters, L.; Claeys, M.; Pannecouque, C.; De Clercq, E.; Van Zeebroeck, A.; Lauwers, S.; Frederich, M.; Foriers, A. Biologically active bisbenzylisoquinoline alkaloids from the root bark of Epinetrum villosum. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 102, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Z.; Lu, Y.; Liao, Q.; Wu, Y.; Chen, X. Fangchinoline inhibits human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication by interfering with gp160 proteolytic processing. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e39225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.E.; Min, J.S.; Jang, M.S.; Lee, J.Y.; Shin, Y.S.; Song, J.H.; Kim, H.R.; Kim, S.; Jin, Y.H.; Kwon, S. Natural Bis-Benzylisoquinoline Alkaloids-Tetrandrine, Fangchinoline, and Cepharanthine, Inhibit Human Coronavirus OC43 Infection of MRC-5 Human Lung Cells. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Dutt, J.; Arrunategui-Correa, V.; Baltatzis, S.; Foster, C.S. Cytokine mRNA in BALB/c mouse corneas infected with herpes simplex virus. Eye 1999, 13, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- He, C.-L.; Huang, L.-Y.; Wang, K.; Gu, C.-J.; Hu, J.; Zhang, G.-J.; Xu, W.; Xie, Y.-H.; Tang, N.; Huang, A.-L. Identification of bis-benzylisoquinoline alkaloids as SARS-CoV-2 entry inhibitors from a library of natural products. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heister, P.M.; Poston, R.N. Pharmacological hypothesis: TPC2 antagonist tetrandrine as a potential therapeutic agent for COVID-19. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2020, 8, e00653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glebov, O.O. Understanding SARS-CoV-2 endocytosis for COVID-19 drug repurposing. FEBS J. 2020, 287, 3664–3671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Yang, P.; Huang, C.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, S. Inhibitory effect on SARS-CoV-2 infection of neferine by blocking Ca2+-dependent membrane fusion. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 93, 5825–5832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Jiang, H.; Yao, T.; Zeng, S. Fragmentation study on the phenolic alkaloid neferine and its analogues with anti-HIV activities by electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry with hydrogen/deuterium exchange and its application for rapid identification of in vitro microsomal metabolites of neferine. Rapid. Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2007, 21, 2120–2128. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Li, H.; Ye, Z.; Xu, Q.; Fu, Q.; Sun, W.; Qi, W.; Yue, J. Berbamine inhibits Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) infection by compromising TPRMLs-mediated endolysosomal trafficking of low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR). Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2021, 10, 1257–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Li, H.; Yuen, T.T.-T.; Ye, Z.; Fu, Q.; Sun, W.; Xu, Q.; Yang, Y.; Chan, J.F.-W.; Zhang, G. Berbamine inhibits the infection of SARS-CoV-2 and flaviviruses by compromising TPRMLs-mediated endolysosomal trafficking of viral receptors. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 6, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, B.; Shen, X.; He, Y.; Pan, X.; Liu, F.-L.; Wang, Y.; Yang, F.; Fang, S.; Wu, Y.; Duan, Z. SARS-CoV-2 envelope protein causes acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)-like pathological damages and constitutes an antiviral target. Cell Res. 2021, 31, 847–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawawi, A.; Ma, C.; Nakamura, N.; Hattori, M.; Kurokawa, M.; Shiraki, K.; Kashiwaba, N.; Ono, M. Anti-herpes simplex virus activity of alkaloids isolated from Stephania cepharantha. Biol Pharm Bull 1999, 22, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, M.; Ono, M.; Baba, M. Potent inhibition of HIV type 1 replication by an antiinflammatory alkaloid, cepharanthine, in chronically infected monocytic cells. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 1998, 14, 1239–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furusawa, S.; Wu, J. The effects of biscoclaurine alkaloid cepharanthine on mammalian cells: Implications for cancer, shock, and inflammatory diseases. Life Sci. 2007, 80, 1073–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuda, K.; Hattori, S.; Komizu, Y.; Kariya, R.; Ueoka, R.; Okada, S. Cepharanthine inhibited HIV-1 cell–cell transmission and cell-free infection via modification of cell membrane fluidity. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 24, 2115–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baba, M.; Okamoto, M.; Kashiwaba, N.; Ono, M. Anti-HIV-1 activity and structure-activity relationship of cepharanoline derivatives in chronically infected cells. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 2001, 12, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Li, G.; Cen, Y. Study on the inhibitory effect of cepharanthine on herpes simplex type-1 virus (HSV-1) in vitro. J. Chin. Med. Mater. 2004, 27, 107–110. [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto, M.; Ono, M.; Baba, M. Suppression of cytokine production and neural cell death by the anti-inflammatory alkaloid cepharanthine: A potential agent against HIV-1 encephalopathy. Biochem. Pharm. 2001, 62, 747–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.H.; Wang, Y.F.; Liu, X.J.; Lu, J.H.; Qian, C.W.; Wan, Z.Y.; Yan, X.G.; Zheng, H.Y.; Zhang, M.Y.; Xiong, S.; et al. Antiviral activity of cepharanthine against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus in vitro. Chin. Med. J. (Engl.) 2005, 118, 493–496. [Google Scholar]

- Ohashi, H.; Watashi, K.; Saso, W.; Shionoya, K.; Iwanami, S.; Hirokawa, T.; Shirai, T.; Kanaya, S.; Ito, Y.; Kim, K.S. Multidrug treatment with nelfinavir and cepharanthine against COVID-19. BioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawawi, A.; Nakamura, N.; Hattori, M.; Kurokawa, M.; Shiraki, K. Inhibitory effects of Indonesian medicinal plants on the infection of herpes simplex virus type 1. Phytother. Res. 1999, 13, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyall, J.; Coleman, C.M.; Venkataraman, T.; Holbrook, M.R.; Kindrachuk, J.; Johnson, R.F.; Olinger Jr, G.G.; Jahrling, P.B.; Laidlaw, M.; Johansen, L.M. Repurposing of clinically developed drugs for treatment of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 4885–4893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, M.R.; Hallock, Y.F.; Cardellina, J.H., 2nd; Manfredi, K.P.; Blunt, J.W.; Mcmahon, J.B.; Buckheit, R.W., Jr.; Bringmann, G.; Schaffer, M.; Cragg, G.M.; et al. Anti-HIV michellamines from Ancistrocladus korupensis. J. Med. Chem. 1994, 37, 1740–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, J.B.; Currens, M.J.; Gulakowski, R.J.; Buckheit, R.W., Jr.; Lackman-Smith, C.; Hallock, Y.F.; Boyd, M.R. Michellamine B a novel plant alkaloid, inhibits human immunodeficiency virus-induced cell killing by at least two distinct mechanisms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1995, 39, 484–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bringmann, G.; Steinert, C.; Feineis, D.; Mudogo, V.; Betzin, J.; Scheller, C. HIV-inhibitory michellamine-type dimeric naphthylisoquinoline alkaloids from the Central African liana Ancistrocladus congolensis. Phytochemistry 2016, 128, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelova, A.; Tenev, T.; Varadinova, T. Expression of cellular proteins Bcl-X (L), XIAP and Bax involved in apoptosis in cells infected with herpes simplex virus 1 and effect of pavine alkaloid (-)-thalimonine on virus-induced suppression of apoptosis. Acta Virol. 2004, 48, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vanquelef, E.; Amoros, M.; Boustie, J.; Lynch, M.A.; Waigh, R.D.; Duval, O. Synthesis and antiviral effect against herpes simplex type 1 of 12-substituted benzo [c] phenanthridinium salts. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2004, 19, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, G.T.; Miller, J.F.; Kinghorn, A.D.; Hughes, S.H.; Pezzuto, J.M. HIV-1 and HIV-2 reverse transcriptases: A comparative study of sensitivity to inhibition by selected natural products. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1992, 185, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, T.-J.; Goodsell, D.S.; Kan, C.-C. Identification of sanguinarine as a novel HIV protease inhibitor from high-throughput screening of 2,000 drugs and natural products with a cell-based assay. Lett. Drug Des. Discov. 2005, 2, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Niu, J.; Wang, C.; Huang, B.; Wang, W.; Zhu, N.; Deng, Y.; Wang, H.; Ye, F.; Cen, S. High-throughput screening and identification of potent broad-spectrum inhibitors of coronaviruses. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e00023-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leitao Da-Cunha, E.V.; Fechine, I.M.; Guedes, D.N.; Barbosa-Filho, J.M.; Sobral Da Silva, M. Protoberberine Alkaloids; The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Biology; Cordell, G.A., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005; Volume 62, pp. 1–75. [Google Scholar]

- Babalghith, A.O.; Al-Kuraishy, H.M.; Al-Gareeb, A.I.; De Waard, M.; Al-Hamash, S.M.; Jean-Marc, S.; Negm, W.A.; Batiha, G.E.-S. The role of berberine in Covid-19: Potential adjunct therapy. Inflammopharmacology 2022, 3(6), 2003–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; You, L.; Wu, J.; Zhao, M.; Guo, R.; Zhang, H.; Su, R.; Mao, Q.; Deng, D.; Hao, Y. Berberine suppresses influenza virus-triggered NLRP3 inflammasome activation in macrophages by inducing mitophagy and decreasing mitochondrial ROS. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2020, 108, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, J.-Q.; Kim, Y.-J.; Wu, J.; Wang, Q.; Hao, Y. In vivo and in vitro antiviral effects of berberine on influenza virus. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2011, 17, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.L.; Han, T.; Liu, R.H.; Zhang, C.; Chen, H.S.; Zhang, W.D. Alkaloids from Corydalis saxicola and their anti-hepatitis B virus activity. Chem. Biodivers. 2008, 5, 777–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aljofan, M.; Netter, H.J.; Aljarbou, A.N.; Hadda, T.B.; Orhan, I.E.; Sener, B.; Mungall, B.A. Anti-hepatitis B activity of isoquinoline alkaloids of plant origin. Arch. Virol. 2014, 159, 1119–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, T.B.; Huang, B.; Fong, W.P.; Yeung, H.W. Anti-human immunodeficiency virus (anti-HIV) natural products with special emphasis on HIV reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Life Sci. 1997, 61, 933–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, M.; Fan, X.; Yuan, B.; Takagi, N.; Liu, S.; Han, X.; Ren, J.; Liu, J. Berberine inhibits NLRP3 Inflammasome pathway in human triple-negative breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cell. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.M.; Wang, R.; Li, J.J.; Li, N.S.; Zheng, Y.T. Anti-HIV-1 activities of four berberine compounds in vitro. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2007, 5, 225–228. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, R.; Sharma, P.; Gupta, G.K.; Ntie-Kang, F.; Kumar, D. Structure-Activity-Relationship and Mechanistic Insights for Anti-HIV Natural Products. Molecules 2020, 25, 2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.-C.; Wang, K.-W. New analogues of aporphine alkaloids. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2018, 18, 1590–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, M.V.; Rao, M.R.; Rhodes, D.; Hansen, M.S.; Rubins, K.; Bushman, F.D.; Venkateswarlu, Y.; Faulkner, D.J. Lamellarin alpha 20-sulfate, an inhibitor of HIV-1 integrase active against HIV-1 virus in cell culture. J. Med. Chem. 1999, 42, 1901–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, T.; Ishibashi, F.; Iwao, M. Lamellarin Alkaloids: Isolation, Synthesis, and Biological Activity. Alkaloids Chem. Biol. 2020, 83, 1–112. [Google Scholar]

- Mediouni, S.; Chinthalapudi, K.; Ekka, M.K.; Usui, I.; Jablonski, J.A.; Clementz, M.A.; Mousseau, G.; Nowak, J.; Macherla, V.R.; Beverage, J.N. Didehydro-cortistatin A inhibits HIV-1 by specifically binding to the unstructured basic region of Tat. mBio 2019, 10, e02662-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessing, C.F.; Nixon, C.C.; Li, C.; Tsai, P.; Takata, H.; Mousseau, G.; Ho, P.T.; Honeycutt, J.B.; Fallahi, M.; Trautmann, L.; et al. In Vivo Suppression of HIV Rebound by Didehydro-Cortistatin A, a "Block-and-Lock" Strategy for HIV-1 Treatment. Cell Rep. 2017, 21, 600–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, S.M.; Hassan, E.M.; Ibrahim, N.A. Cytotoxic and antiviral activities of aporphine alkaloids of Magnolia grandiflora L. Nat. Prod. Res. 2010, 24, 1395–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avci, F.G.; Atas, B.; Gulsoy Toplan, G.; Gurer, C.; Sariyar Akbulut, B. Chapter 4—Antibacterial and Antifungal Activities of Isoquinoline Alkaloids of the Papaveraceae and Fumariaceae Families and Their Implications in Structure–Activity Relationships; Studies in Natural Products Chemistry; Atta ur, R., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; Volume 70, pp. 87–118. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.-Y.; Shin, H.-S.; Park, H.; Kim, Y.-C.; Yun, Y.G.; Park, S.; Shin, H.-J.; Kim, K. In vitro inhibition of coronavirus replications by the traditionally used medicinal herbal extracts, Cimicifuga rhizoma, Meliae cortex, Coptidis rhizoma, and Phellodendron cortex. J. Clin. Virol. 2008, 41, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, T.; Khan, M.A.; Ullah, N.; Nadhman, A. Therapeutic potential of medicinal plants against COVID-19: The role of antiviral medicinal metabolites. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2021, 31, 101890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, L.V.; Ngo, H.T.; Lim, Y.-S.; Hwang, S.B. Hepatitis C virus non-structural 5B protein interacts with cyclin A2 and regulates viral propagation. J. Hepatol. 2012, 57, 960–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.-Y.; Chen, C.; Zhang, H.-Q.; Guo, H.-Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Hua, S.-N.; Yu, J.; Xiao, P.-G. Identification of natural compounds with antiviral activities against SARS-associated coronavirus. Antivir. Res. 2005, 67, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Forrest, J.C.; Zhang, X. A screen of the NIH Clinical Collection small molecule library identifies potential anti-coronavirus drugs. Antivir. Res. 2015, 114, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-W.; Lee, Y.-Z.; Kang, I.-J.; Barnard, D.L.; Jan, J.-T.; Lin, D.; Huang, C.-W.; Yeh, T.-K.; Chao, Y.-S.; Lee, S.-J. Identification of phenanthroindolizines and phenanthroquinolizidines as novel potent anti-coronaviral agents for porcine enteropathogenic coronavirus transmissible gastroenteritis virus and human severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Antivir. Res. 2010, 88, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, I.; Ahmet, O. Potentials of plant-based substance to inhabit and probable cure for the COVID-19. Turk. J. Biol. 2020, 44, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, A.; Gopi Krishna Reddy, A.; Satyanarayana, G.; Raghavendra, N.K. 1,2,3,4-Tetrahydroisoquinolines as inhibitors of HIV-1 integrase and human LEDGF/p75 interaction. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2018, 91, 1133–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turano, A.S.G.; Caruso a Bonfanti, C.; Luzzati, R.; Bassetti, D.; Manca, N. Inhibitory effect of papaverine on HIV replication in vitro. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 1989, 5, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, Y.; Iwasa, K.; Okada, S.; Takeuchi, S.; Moriyasu, M.; Kamigauchi, M.; Koyama, J.; Takeuchi, A.; Tokuda, H.; Kim, H.S. Geranyl derivatives of isoquinoline alkaloids show increased biological activities. Heterocycles 2010, 81, 1193–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasa, K.; Moriyasu, M.; Tachibana, Y.; Kim, H.-S.; Wataya, Y.; Wiegrebe, W.; Bastow, K.F.; Cosentino, L.M.; Kozuka, M.; Lee, K.-H. Simple Isoquinoline and Benzylisoquinoline Alkaloids as Potential Antimicrobial, Antimalarial, Cytotoxic, and Anti-HIV Agents. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2001, 9, 2871–2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, C.; Opatz, T. Chapter One—Bisbenzylisoquinoline Alkaloids, The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Biology; Knölker, H.-J., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 1–114. [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto, M.; Okamoto, T.; Baba, M. Inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication by combination of transcription inhibitor K-12 and other antiretroviral agents in acutely and chronically infected cells. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1999, 43, 492–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Tang, Q.; Rao, Z.; Fang, Y.; Jiang, X.; Liu, W.; Luan, F.; Zeng, N. Inhibition of herpes simplex virus 1 by cepharanthine via promoting mcellular autophagy through up-regulation of STING/TBK1/P62 pathway. Antivir. Res. 2021, 193, 105143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, H.-H.; Wang, L.-Q.; Liu, W.-L.; An, X.-P.; Liu, Z.-D.; He, X.-Q.; Song, L.-H.; Tong, Y.-G. Repurposing of clinically approved drugs for treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 in a 2019-novel coronavirus-related coronavirus model. Chin. Med. J. 2020, 133, 1051–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Liu, W.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L.; An, W.; An, X.; Song, L.; Tong, Y.; Fan, H.; Lu, C. Transcriptome analysis of cepharanthine against a SARS-CoV-2-related coronavirus. Brief. Bioinform. 2021, 22, 1378–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Yu, R.; Wang, X.; Chen, B.; Si, F.; Zhou, J.; Xie, C.; Li, Z.; Zhang, D. Bis-Benzylisoquinoline Alkaloids Inhibit Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus In Vitro and In Vivo. Viruses 2022, 14, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chen, X.; Zhou, S.-J. Dauricine combined with clindamycin inhibits severe pneumonia co-infected by influenza virus H5N1 and Streptococcus pneumoniae in vitro and in vivo through NF-κB signaling pathway. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 137, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Lao, B.; Dong, X.; Sun, X.; Dong, Y.; Sheng, G.; Fu, J. Study on anti-influenza effect of alkaloids from roots of Mahonia bealei in vitro. Zhong Yao Cai 2003, 26, 29–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, S.; Dutt, J.; Zhao, T.; Foster, C.S. Stephen Foster Tetrandrine potently inhibits herpes simplex virus type-1-induced keratitis in BALB/c mice. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 1997, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wink, M. Potential of DNA intercalating alkaloids and other plant secondary metabolites against SARS-CoV-2 causing COVID-19. Diversity 2020, 12, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Xu, M.; Lee, E.M.; Gorshkov, K.; Shiryaev, S.A.; He, S.; Sun, W.; Cheng, Y.; Hu, X.; Tharappel, A.M.; et al. Emetine inhibits Zika and Ebola virus infections through two molecular mechanisms: Inhibiting viral replication and decreasing viral entry. Cell Discov. 2018, 4, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, P.I.; Krpina, K.; Ianevski, A.; Shtaida, N.; Jo, E.; Yang, J.; Koit, S.; Tenson, T.; Hukkanen, V.; Anthonsen, M.W.; et al. Novel Antiviral Activities of Obatoclax, Emetine, Niclosamide, Brequinar, and Homoharringtonine. Viruses 2019, 11, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, G.T.; Kinghorn, A.D.; Hughes, S.H.; Pezzuto, J.M. Psychotrine and its O-methyl ether are selective inhibitors of human immunodeficiency virus-1 reverse transcriptase. J. Biol.Chem. 1991, 266, 23529–23536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, G.T.; Pezzuto, J.M.; Kinghorn, A.D.; Hughes, S.H. Evaluation of natural products as inhibitors of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) reverse transcriptase. J. Nat. Prod. 1991, 54, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredi, K.P.; Blunt, J.W.; Cardellina, J.H., 2nd; Mcmahon, J.B.; Pannell, L.L.; Cragg, G.M.; Boyd, M.R. Novel alkaloids from the tropical plant Ancistrocladus abbreviatus inhibit cell killing by HIV-1 and HIV-2. J. Med. Chem. 1991, 34, 3402–3405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, E.L.; Chao, W.R.; Ross, L.J.; Borhani, D.W.; Hobbs, P.D.; Upender, V.; Dawson, M.I. Michellamine alkaloids inhibit protein kinase C. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1999, 365, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supko Jg, M.L. Pharmacokinetics of michellamine B, a naphthylisoquinoline alkaloid with in vitro activity against human immunodeficiency virus types 1 and 2, in the mouse and dog. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1995, 39, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallock, Y.F.; Manfredi, K.P.; Dai, J.-R.; Cardellina, J.H.; Gulakowski, R.J.; Mcmahon, J.B.; Schäffer, M.; Stahl, M.; Gulden, K.-P.; Bringmann, G. Michellamines D− F, new HIV-inhibitory dimeric naphthylisoquinoline alkaloids, and korupensamine E, a new antimalarial monomer, from Ancistrocladus korupensis. J. Nat. Prod. 1997, 60, 677–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ka, S.; Merindol, N.; Sow, A.A.; Singh, A.; Landelouci, K.; Plourde, M.B.; Pépin, G.; Masi, M.; Di Lecce, R.; Evidente, A. Amaryllidaceae alkaloid cherylline inhibits the replication of dengue and Zika viruses. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 65, e00398-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homan, J.W.; Steele, A.D.; Martinand-Mari, C.; Rogers, T.J.; Henderson, E.E.; Charubala, R.; Pfleiderer, W.; Reichenbach, N.L.; Suhadolnik, R.J. Inhibition of morphine-potentiated HIV-1 replication in peripheral blood mononuclear cells with the nuclease-resistant 2-5A agonist analog, 2-5A(N6B). JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2002, 30, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, W.W. Structural Modification, Bioactivity of Derivatives of Three Protopines and Their Structure-Activity Relationship. Postgraduate Thesis, Northwest A&F University, ShanXi, China.

- Huang, Q.; Wu, X.; Zheng, X.; Luo, S.; Xu, S.; Weng, J. Targeting inflammation and cytokine storm in COVID-19. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 159, 105051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.S.; Kim, H.S.; Min, K.R.; Kim, Y.; Lim, H.K.; Chang, Y.K.; Chung, M.W. Anti-inflammatory effects of fangchinoline and tetrandrine. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2000, 69, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.-J.; Ng, L.-T. Tetrandrine Inhibits Proinflammatory Cytokines, iNOS and COX-2 Expression in Human Monocytic Cells. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2007, 30, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Wang, Y.; Feng, D.-C.; Xiao, B.-G.; Xu, L.-Y. Tetrandrine suppresses lipopolysaccharide-induced microglial activation by inhibiting NF-κB pathway. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2008, 29, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eissa, L.A.; Kenawy, H.I.; El-Karef, A.; Elsherbiny, N.M.; El-Mihi, K.A. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of berberine attenuate hepatic fibrosis induced by thioacetamide injection in rats. Chem. -Biol. Interact. 2018, 294, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, S.A. Noscapine, a possible drug candidate for attenuation of cytokine release associated with SARS-CoV-2. Drug Dev. Res. 2020, 81, 765–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Liu, Y.; Xia, G.; Liu, Y.; Lin, S.; Guo, L. Novel isoquinoline alkaloid litcubanine A-a potential anti-inflammatory candidate. Front. Immunol. 2021, 1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

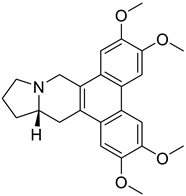

| Sr. No. | Alkaloid | Isoquinoline and Related Alkaloid | Structure | Target | Binding Score/Affinity | Docking Software | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Thebaine | aporphine alkaloid |  | ACE2, S-protein | −100.77 and −103.58 kcal/mol | Molegro Virtual Docker 3.0.0 | [46] |

| 2. | Berberine | Protoberberine alkaloid |  | ACE2, S-protein, 3CLpro | −97.54, −99.93 and −7.3 kcal/mol | Auto Dock; Auto Dock Vina | [46,47] |

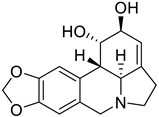

| 3. | Lycorine | Tetrahydroisoquinolines |  | S1 subunit; SARS-CoV-2 | −86.92 kcal/mol | Discovery Studio 2.5 | [42] |

| 4. | Tylophorine | phenanthraindolizidine alkaloid |  | S1 subunit; SARS-CoV-2 | −89.77 kcal/mol | Discovery Studio 2.5 | [42] |

| 5. | Tetrandrine | bis-benzylisoquinoline alkaloid |  | S1 subunit; SARS-CoV-2 | −72.96 kcal/mol | Discovery Studio 2.5 | [42] |

| 6. | Fangchinoline | bis-benzylisoquinoline |  | S1 subunit; SARS-CoV-2 | −92.66 kcal/mol | Discovery Studio 2.5 | [42] |

| 7. | Berbamine | bis-benzylisoquinoline |  | Mpro | −20.79 kcal/mol | PyRx | [48] |

| 8. | Noscapine | phthalideisoquinoline alkaloid |  | Mpro | −292.42 kJ/mol | Hex 8.0 | [49] |

| 9. | Palmatine | protoberberine |  | Mpro | >8 kcal/mol | Swiss Dock; EADock DSS | [50] |

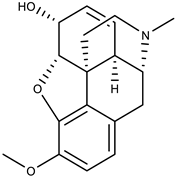

| 10. | Morphine | aporphine alkaloid |  | Mpro | >−6.0 kcal/mol | AutoDock Vina v.1.0.2. | [51] |

| 11. | Codeine | aporphine alkaloid |  | Mpro | >−6.0 kcal/mol | AutoDock Vina v.1.0.2. | [51] |

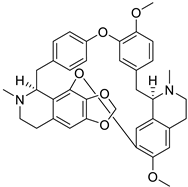

| 12. | Cepharanthine | biscoclaurine alkaloid |  | 3CLpro, S1-RBD, and TMPRSS-2 | −8.5, −106.74, −7.4 kcal/mol | Auto Dock Vina v.1.0.2; Discovery Studio 2.5 | [42,52] |

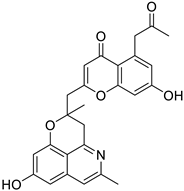

| 13. | Cassiarin D | isoquinoline alkaloid |  | RdRP | −150.7 kJ/mol | Molegro Virtual Docker (version 6.0, Molegro ApS, Aarhus, Denmark)) | [53] |

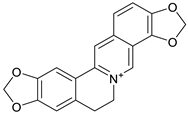

| 14. | Coptisine | protoberberine |  | Mpro, N3-Mpro | −9.15 and −8.17 kcal/mol | Autodock (version 4.2) | [54] |

| 15. | Emetine | Ipecac alkaloids |  | Mpro | −10.17 kcal/mol | Autodock version 4.2.6 | [55] |

| Sr. No. | Active Compound | Cell Lines/model | IC50/CC50 Value | EC50/ED50 Value | Mechanism/Activity | Antiviral Activity | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protoberberine Alkaloids | |||||||

| 1. | Berberine | HEC-1-A cells HEK293T | 165.7 µM | - | suppression of HSV-induced NF-κB activation, IκB-α degradation and p65 nuclear translocation | HSV | [60] |

| J774A.1 cells | - | - | inhibition of HIV-PI induced TNF-α and IL-6 in macrophages | HIV | [61] | ||

| Calu-3 cells | - | - | increases CD8+ cells and IFN-γ to produce immunomodulatory activity | SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 | [62] | ||

| Vero E6 cells | 10.58 µΜ | - | drug antagonism was seen (remdesivir + BBR) | SARS-CoV-2 | [63] | ||

| Vero E6 cell | - | 16.70 μM | suppression of SARS-CoV-2 target proteins | SARS-CoV-2 | [64] | ||

| VeroE6 cells and nasal epithelial cells | - | 9.1 µM | inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 replication | SARS-CoV-2 | [65] | ||

| RAW 264.7 macrophage and A549 cells | 0.44 μM | - | inhibition of viral growth of influenza and suppresses production of TNF-α and PGE2 | H1N1 | [66] | ||

| human osteosarcoma cell (HOS) | - | 12.2 µM | inhibits MAPK/PI3K-AKt signaling pathways | Chikungunya virus | [67] | ||

| A549 cells and in vivo (mice) | - | - | BBR suppresses TLR7, MyD88, and NF-κB to resist viral replication in mice | H1N1 | [68,69] | ||

| HFF, HELF, and NIH 3T3 | - | 2.65 µM | inhibition of DNA polymerase and immediate-early (IE-3) proteins | HCMV | [70] | ||

| A549, LET1, HAE, and MDCK | 17 µM, 4 µM, 16 µM, and 52 µM | - | interfere MEK/ERK pathway to inhibit export of the viral ribonucleoprotein | H1N1 | [68] | ||

| 2. | Saxicolalines A | Hep G 2.2.15 cell line | 2.19 and >2.81 against HBsAg b* and HBeAg c* respectively | - | - | HBV | [71] |

| 3. | N-methylnarceimicine | Hep G 2.2.15 cell line | 1.24 µM and 1.86 µM against HBsAg b and HBeAg c respectively | - | - | HBV | [71] |

| Aporphine Alkaloids | |||||||

| 1. | Roemerine | H9 cells | - | 0.84 μg/mL | inhibition of HIV replication by 50% | HIV-1 | [72] |

| 2. | Nuciferine | 0.8 μg/mL | |||||

| 3. | Nornuciferine | <0.8 μg/mL | |||||

| 4. | Boldine | PMBMCs, CEM-GXR cells, Vero cells | 207.7, 250 µM | 50.2 µM | inhibit HIV-1 replication, reduction of the viral titer | HIV-1, poliovirus | [73,74] |

| 5. | Dasymaroine A | C8166 cell line | - | 1.93 to 9.70 µM | reduce viral replication by 50% | HIV-1 | [75] |

| 6. | Dasymaroine B | ||||||

| 7. | Laurolitsine | Vero cells | 95 µM | 62 µM | reduction of the viral titer | Poliovirus | [74] |

| 8. | Isoboldine HCL | 217 µM | −15 µM | ||||

| 9. | Glaucine fumarate | 142 µM | 9 µM | ||||

| 10. | N-acetylnorglaucine | 342 µM | 50 µM | ||||

| 11. | N-methyllaurotetanine | 250 µM | 15 µM | ||||

| 12. | laurotetanine, HCl | 165 µM | 31 µM | ||||

| 13. | (+)-bulbocapnine | MDBK and Vero cell lines | - | - | - | PI-3 | [76] |

| 14. | Pachystaudine | Vero cells | 68 µM | −31 µM | reduction of the viral titer and viral replication | Poliovirus and HSV | [74,77] |

| 15. | Oxostephanine | 28 µM | - | ||||

| 16. | Oliverine HCl | Vero cells | 9 µM | - | reduction of the viral titer | Poliovirus | [74] |

| Benzylisoquinoline and Benzyltetrahydroisoquinoline Alkaloids | |||||||

| 1. | (+)-1(R)-coclaurine | H9 cells | >100 µg/mL | 0.8 µg/mL | inhibition of HIV replication by 50% | HIV-1 | [72] |

| 2. | (−)-1(R)-N-methylcoclaurinre | 1.45 µg/mL | <0.8 µg/mL | ||||

| 3. | (−)-1(S)-norcoclaurine | 20 µg/mL | <0.8 µg/mL | ||||

| 4. | Armepavine | 1.77 µg/mL | <0.8 µg/mL | ||||

| 5. | Lotusine | >100 µg/mL | 20.7 µg/mL | ||||

| 6. | Papaverine | Vero E6, Caco-2, and BHK-21 cells | 1.1 µM | - | reduce SARS-CoV-2 cytotoxic effect | SARS-CoV-2 | [78] |

| 7. | Papaverine hydrochloride | MT4 cells | 5.8 µM | inhibition of viral replication | HIV | [79] | |

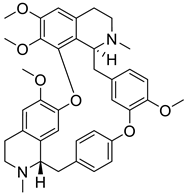

| Bis-benzylisoquinoline Alkaloids (BBI) | |||||||

| 1. | Aromoline | MT-4 cells | - | IC100 31.3µg/mL | cytopathic effect of HIV is inhibited | HIV-1 | [80] |

| 2. | Cycleanine | HCT-116 | - | 1.83 µg/mL | - | HIV-2 | [81] |

| 3. | Fangchinoline | MT-4, PM1, and 293T cells | - | 0.8 to 1.7 µM | interfering with gp160 proteolytic cleavage thus inhibit viral replication | HIV-1 | [82] |

| MRC-5 fibroblast lung cell line | 1.01 µM | - | inhibition of S and N protein expression as well as HCoV-OC43 replication | HCoV-OC43 | [83] | ||

| 4. | Tetrandrine | BALB | - | - | IL-6 inhibition in the corneal inflammation | HSV | [84] |

| HEK 293T cells expressing ACE2 | - | >10 µM | suppress viral entry by inhibiting Ca2+-mediated fusion | SARS-CoV-2 | [85] | ||

| MRC-5 cells | 0.33 μmol/L | - | two-pore channel 2 inhibition | SARS-CoV-2 | [86,87] | ||

| MRC-5 fibroblast lung cell line | 0.33 µM | - | inhibition of S and N protein expression as well as HCoV-OC43 replication | HCoV-OC43 | [83] | ||

| 5. | Neferine | HEK293/hACE2 and HuH7 cell lines | - | 0.13–0.41 µΜ | blockage of viral entry by inhibiting Ca2+-mediated fusion | HCOV OC43 | [88] |

| Dog hepatic microsomes | - | - | N-demethylation and O-demethylation | HIV | [89] | ||

| HEK 293T cells expressing ACE2 | - | >10 µM | suppress viral entry by inhibiting Ca2+−-mediated fusion | SARS-CoV-2 | [85] | ||

| Huh7, HEK293/hACE2 cell lines | - | 0.36 µM | blockage of Ca2+ dependent membrane fusion | SARS-CoV-2 | [88] | ||

| 6. | Berbamine | Hela cells, A549 cells | - | JEV (1.62 µM) ZIKV (2.17 µM) | inhibiting Ca2+ channel transient receptor potential membrane channel mucolipin (TRPML) | JEV andZIKV | [90] |

| Huh7-cells | - | ~2.4 μM | inhibition of Ca2+ influx and TRPMLs | SARS-CoV-2 | [91] | ||

| Vero E6 cells | 5.79 µM | 0.94 µM | inhibition to the 2-E channel | SARS-CoV-2 | [92] | ||

| Vero cells | 16.3–24.9 µg/mL | - | - | HSV-1 TK and HSV-2 | [93] | ||

| 7. | Cepharanthine | U1 and ACH-2 | - | 0.016 µg/mL | inhibition of NF-κB pathway | HIV-1 | [94] |

| U937 cells | 4.6 µg/mL | - | inhibition of inflammatory cytokines | HIV-1 | [95] | ||

| PHA-blast cells from PBMC, HEK 293T, MOLT4 cells | CC50—10.0 µg/mL | - | reduce plasma membrane fluidity to block the NF-κB pathway and HIV-1 entrance | HIV-1 | [96] | ||

| U1 cells | - | 0.0041 µg/mL | inhibition of NF-κB pathway | HIV-1 | [94,97] | ||

| Vero cells and Hela cells | 0.835 μg/mL | - | inhibition of NF-κB | HSV | [98,99] | ||

| MRC-5 fibroblast lung cell line | 0.83 µM | - | inhibition of viral S and N protein expression as well as HCoV-OC43 replication | HCoV-OC43 | [83] | ||

| Vero E6 cells | 6.0 µg/mL–9.5 µg/mL | - | - | SARS-CoV | [100] | ||

| HEK 293T cells expressing ACE2 | - | >10 µM | suppression of viral entry through inhibition of Ca2+-mediated fusion | SARS-CoV-2 | [85] | ||

| Vero E6 cells | 0.91 µM | - | combination of NFV and CEP reduces viral RNA levels | SARS-CoV-2 | [101] | ||

| 8. | di-O-acetylsinococuline (FK-3000) | MT-4 cells | CC0 15.6 µg/mL | - | inhibition of HIV cytopathic effect | HIV-1 | [80] |

| 9. | 12-O-ethylpiperazinyl cepharanoline | U1 cells | - | 0.028 µg/mL | inhibition of NF-κB pathway | HIV-1 | [97] |

| 10. | Homoaromoline | Vero cells | 16.3–24.9 µg/mL | - | - | HSV-1 TK and HSV-2 | [102] |

| 11. | Isotetrandrine | ||||||

| 12. | Thalrugosine | ||||||

| 13. | Obamegine | ||||||

| 14. | Hernandezine | HEK 293T cells | - | >10 µM | inhibition of Ca2+-mediated fusion | SARS-CoV-2 | [85] |

| Ipecac Alkaloids | |||||||

| 1. | Emetine | HEK293 cells | 93–52.9 nM | - | inhibit MERS-CoV entry | MERS-CoV | [103] |

| SNB-19 cells | 29.8 nM | - | |||||

| Vero E6 cells | 8.74 nM | - | |||||

| BHK21 cells | 0.30 µM | ||||||

| Vero E6, Caco-2, and BHK-21 cells | 0.52 µM | - | inhibit cytotoxic effect of SARS-CoV-2 | SARS-CoV-2 | [78] | ||

| 2. | Emetine dihydrochloride hydrate | Vero E6 cells | - | 0.051 µM | inhibition of viral replication - | SARS | [103] |

| 0.014 µM | MERS | ||||||

| Naphthylisoquinoline Alkaloids | |||||||

| 1. | Michellamine A | MT-2 target, CEM-SS cells | - | EC50~20 µM | inhibition of viral replication | HIV-1 and HIV-2 | [104] |

| 2. | Michellamine B | MT-2 target, CEM-SS cells | - | EC50~20 µM | inhibition of viral replication | HIV-1 and HIV-2 | [104,105] |

| CEM-SS and MT-2 | - | 18 µg/mL | inhibition of viral replication | HIV-1 and HIV-2 | [104] | ||

| H9 Cells | 20.4 µM | - | |||||

| 3. | Michellamine A2 | H9 Cells | 29.6 µM | - | inhibition of HIV replication | HIV-1 | [106] |

| 4. | Michellamine A3 | H9 Cells | 15.2 µM | - | HIV-1 | [106] | |

| 5. | Michellamine A4 | H9 Cells | 35.9 µM | - | HIV-1 | [106] | |

| Pavine Alkaloid | |||||||

| 1. | (−)-Thalimonine | MDBK cells | - | - | restoration of apoptosis during viral replication | HSV | [107] |

| Morphinan and Promorphinan | |||||||

| 1. | FK-3000 | Vero cells | 7.8 µg/mL | - | reduction in plaque formation | HSV | [93] |

| 2. | Cephakicine | 44.4 µg/mL | |||||

| 3. | Sinoacutine | >50 µg/mL | |||||

| 4. | Cephasamine | ||||||

| 5. | Cephamonine | ||||||

| 6. | Sinomenine | ||||||

| 7. | 14-episinomenine | ||||||

| 8. | Tannagine | ||||||

| Benzophenanthridines | |||||||

| 1. | Fagaronine | Vero cells | CC50 > 0.3 mM | - | inhibition of topoisomerases I and II | HSV | [108] |

| 2. | Fagaronine chloride | HIV-1 and HIV-2 RT assays | IC50—9.5 µg/mL | - | inhibit RNA and DNA polymerizing enzymes | HIV-2 RT | [109] |

| 3. | Nitidine chloride | IC50—7.1 µg/mL | - | ||||

| 4. | Sanguinarine | HTS (E. coli-based assay) | IC50—12.82 µM | - | inhibits proteolytic activity | HIV-1 | [110] |

| 5. | Chelerythrine | IC50—38.71 µM | |||||

| 6. | Lycorine | BHK21 cells | - | 0.15 µM | viral load suppression | HCoV-OC43 | [111] |

| Sr. No. | Title | Phase | Viral Infection | Study | Completion of Study | Origin | NCT Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The Effect of Berberine on Intestinal Function and Inflammatory Mediators in Severe Patients with Covid-19 (BOIFIM) | Phase 4 | COVID-19 | Interventional | April 2020 | Chinese medical association | NCT04479202 |

| 2 | Effect of Berberine on Metabolic Syndrome, Efficacy and Safety in Combination with Antiretroviral Therapy in PLWH. (BERMESyH) | Phase 3 | HIV-1 | Interventional | July 2022 | Hospital Civil de Guadalajara | NCT04860063 |

| 3 | Tetrandrine Tablets Used in the Treatment of COVID-19 (TT-NPC) | Phase 4 | COVID-19 | Interventional | May 2021 | Henan Provincial People’s Hospital | NCT04308317 |

| 4 | Study of Oral High/Low-dose Cepharanthine Compared with Placebo in Non-Hospitalized Adults with COVID-19 | Phase 2 | COVID-19 | Interventional | August 2022 | Hai Li, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine | NCT05398705 |

| 5 | Measurement of the Efficacy of MORPHINE in the Early Management of Dyspnea in COVID-19 Positive Patients (CODYS) | NA | COVID-19 | Observational | February 2021 | Hospices Civils de Lyon | NCT04522037 |

| 6 | Safety and Efficacy of COVIDEX™ Therapy in Management of Adult COVID-19 Patients in Uganda. (COT) | Phase 2 | COVID-19 | Interventional | December 2022 | College of Health Sciences, Makerere University | NCT05228626 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sharma, D.; Sharma, N.; Manchanda, N.; Prasad, S.K.; Sharma, P.C.; Thakur, V.K.; Rahman, M.M.; Dhobi, M. Bioactivity and In Silico Studies of Isoquinoline and Related Alkaloids as Promising Antiviral Agents: An Insight. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom13010017

Sharma D, Sharma N, Manchanda N, Prasad SK, Sharma PC, Thakur VK, Rahman MM, Dhobi M. Bioactivity and In Silico Studies of Isoquinoline and Related Alkaloids as Promising Antiviral Agents: An Insight. Biomolecules. 2023; 13(1):17. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom13010017

Chicago/Turabian StyleSharma, Divya, Neetika Sharma, Namish Manchanda, Satyendra K. Prasad, Prabodh Chander Sharma, Vijay Kumar Thakur, M. Mukhlesur Rahman, and Mahaveer Dhobi. 2023. "Bioactivity and In Silico Studies of Isoquinoline and Related Alkaloids as Promising Antiviral Agents: An Insight" Biomolecules 13, no. 1: 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom13010017

APA StyleSharma, D., Sharma, N., Manchanda, N., Prasad, S. K., Sharma, P. C., Thakur, V. K., Rahman, M. M., & Dhobi, M. (2023). Bioactivity and In Silico Studies of Isoquinoline and Related Alkaloids as Promising Antiviral Agents: An Insight. Biomolecules, 13(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom13010017