Histamine Intolerance: The Current State of the Art

Abstract

1. Introduction

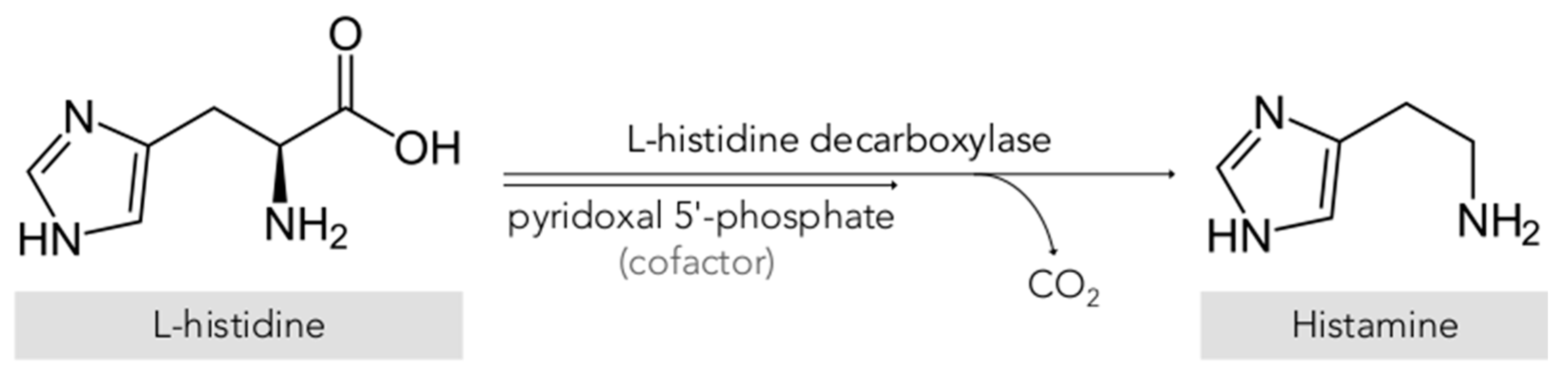

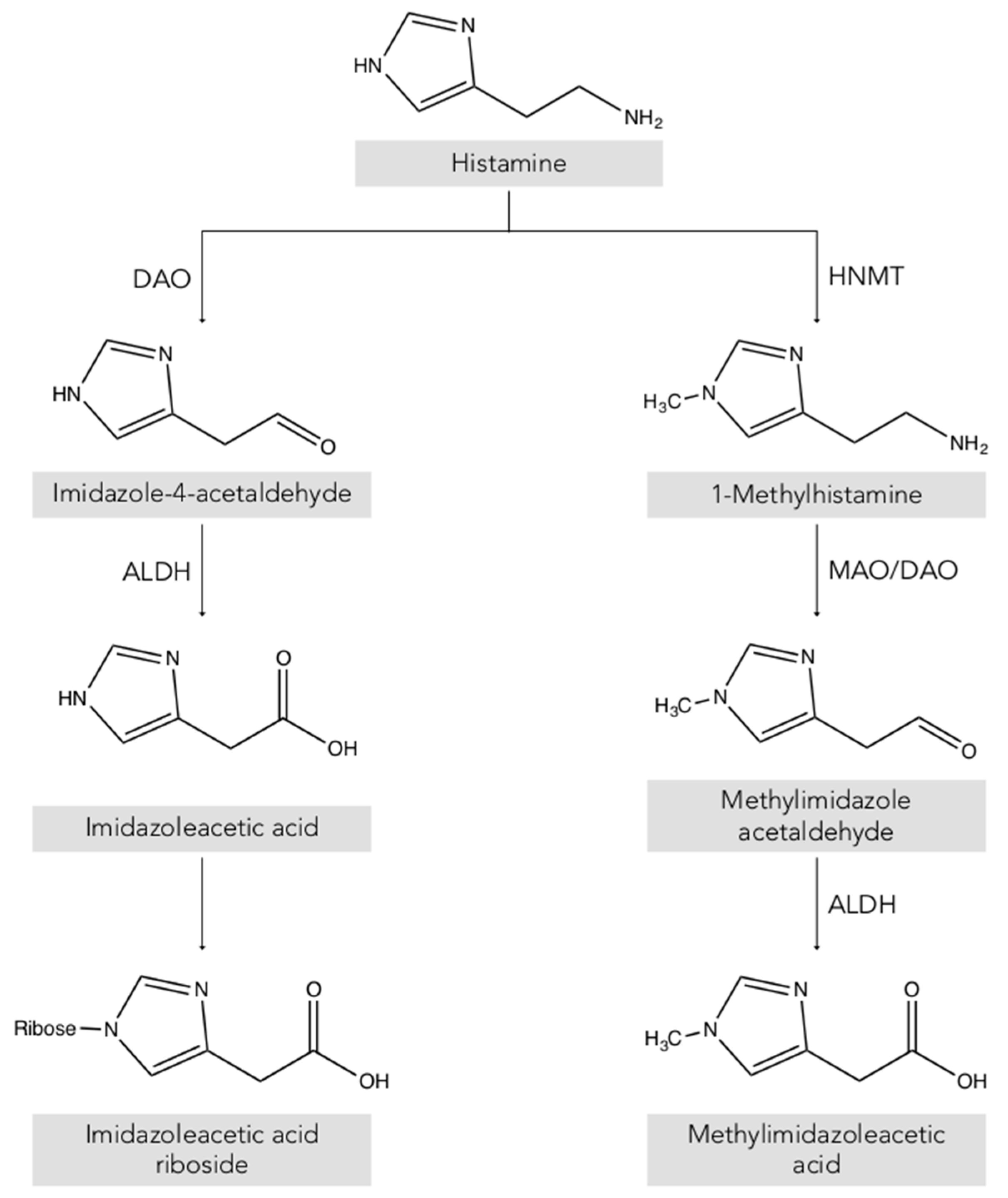

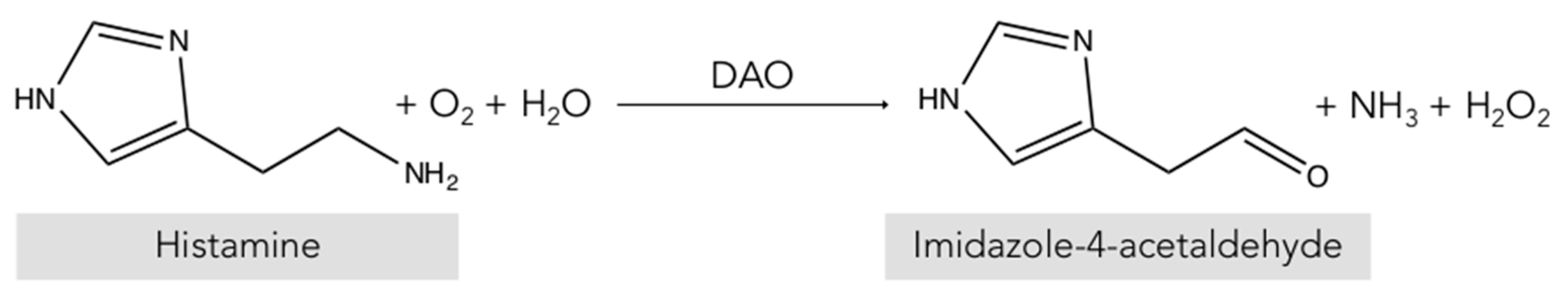

2. Histamine

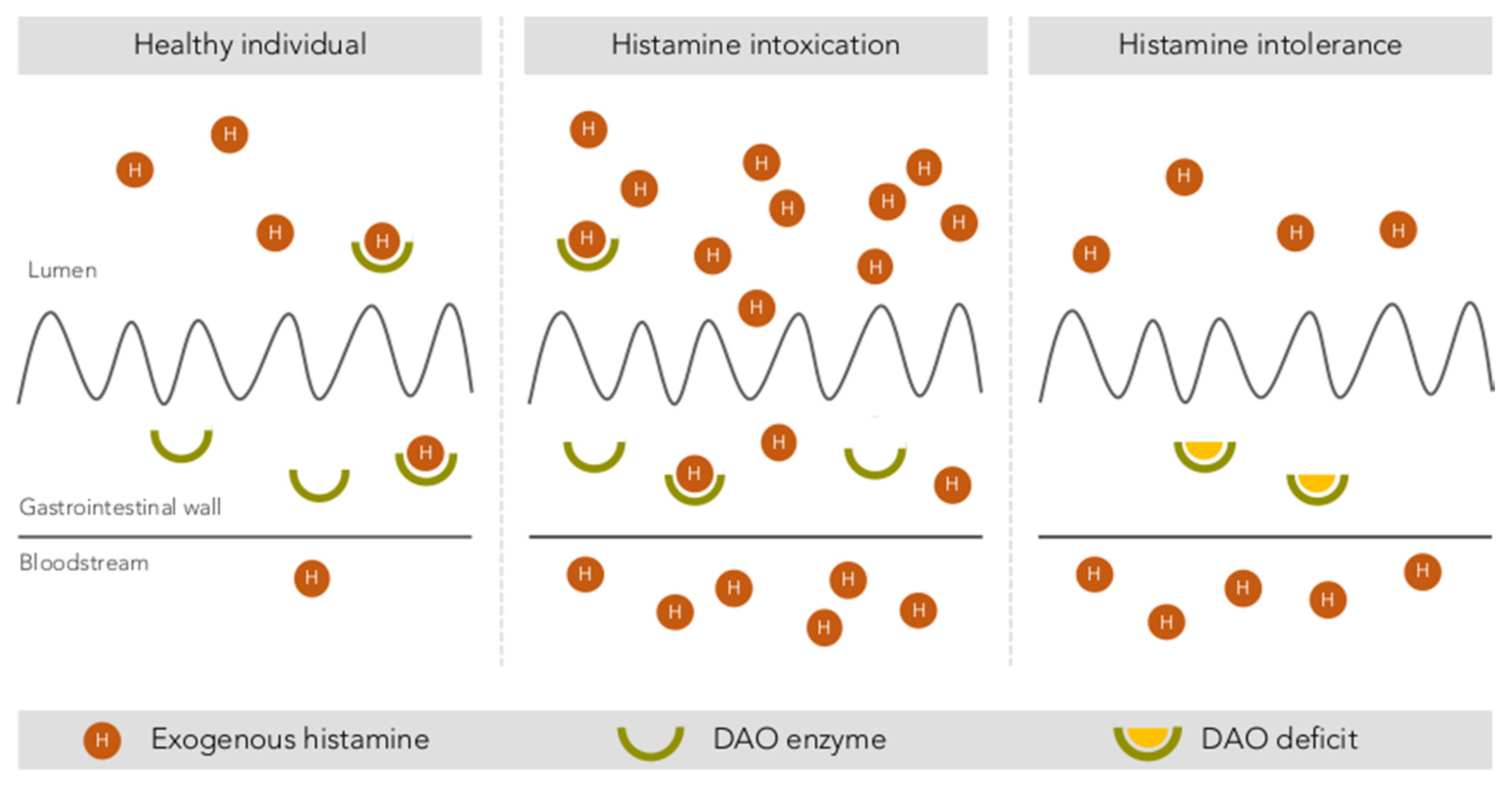

3. Histamine in Foods

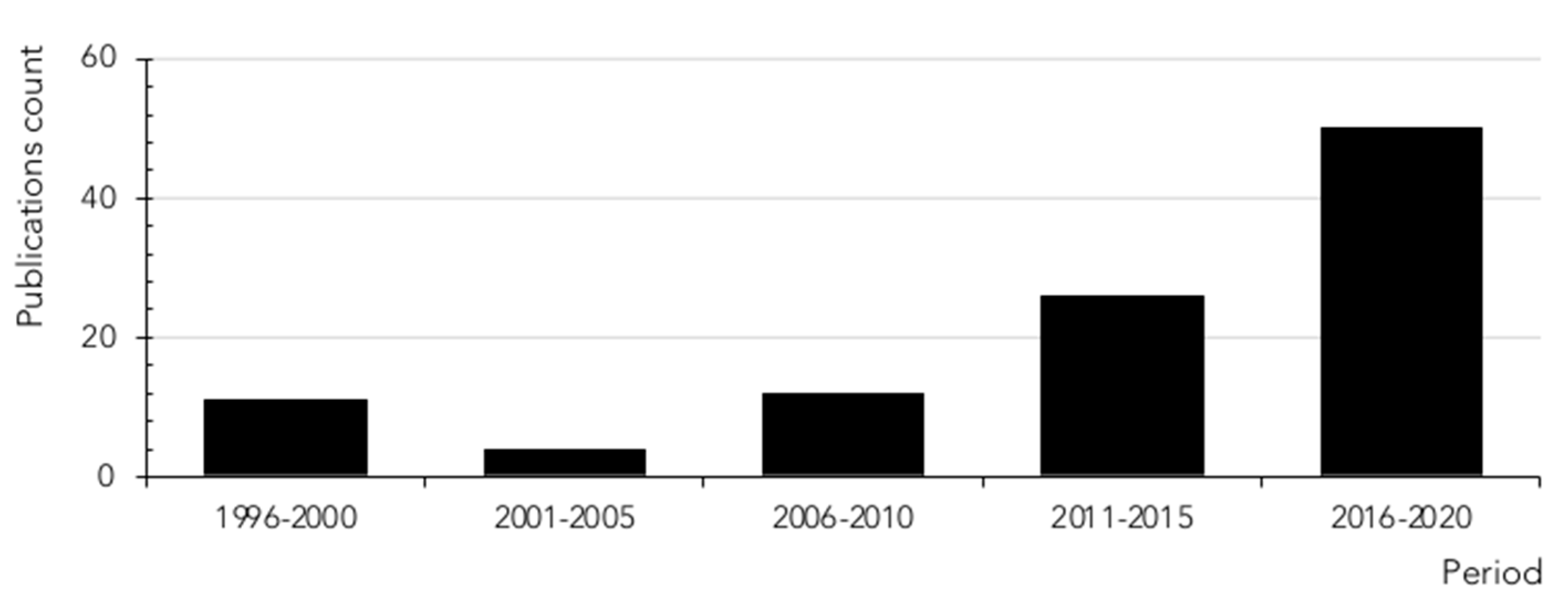

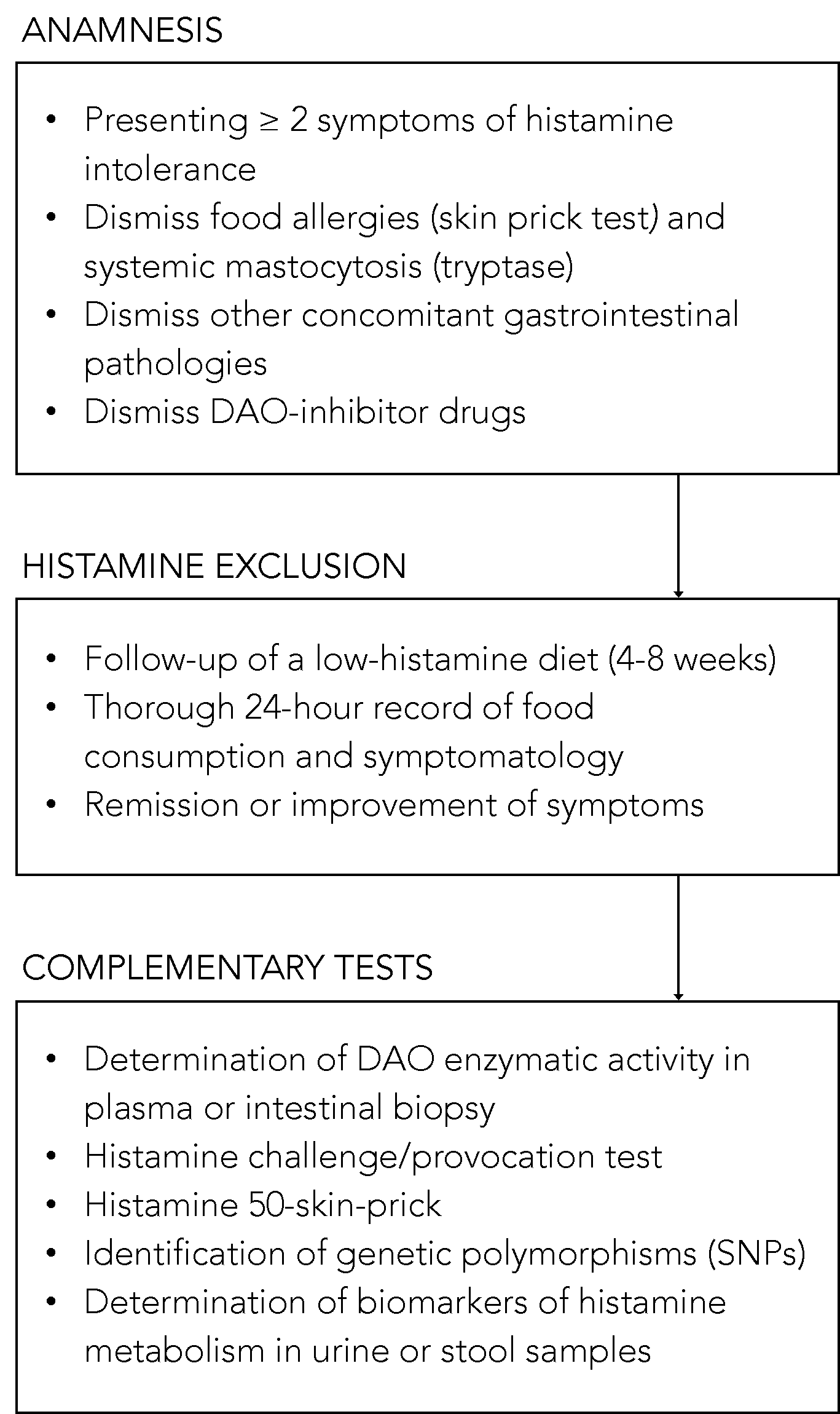

4. Uncertainties Associated with Histamine Poisoning: A Paradigm Shift Towards Histamine Intolerance

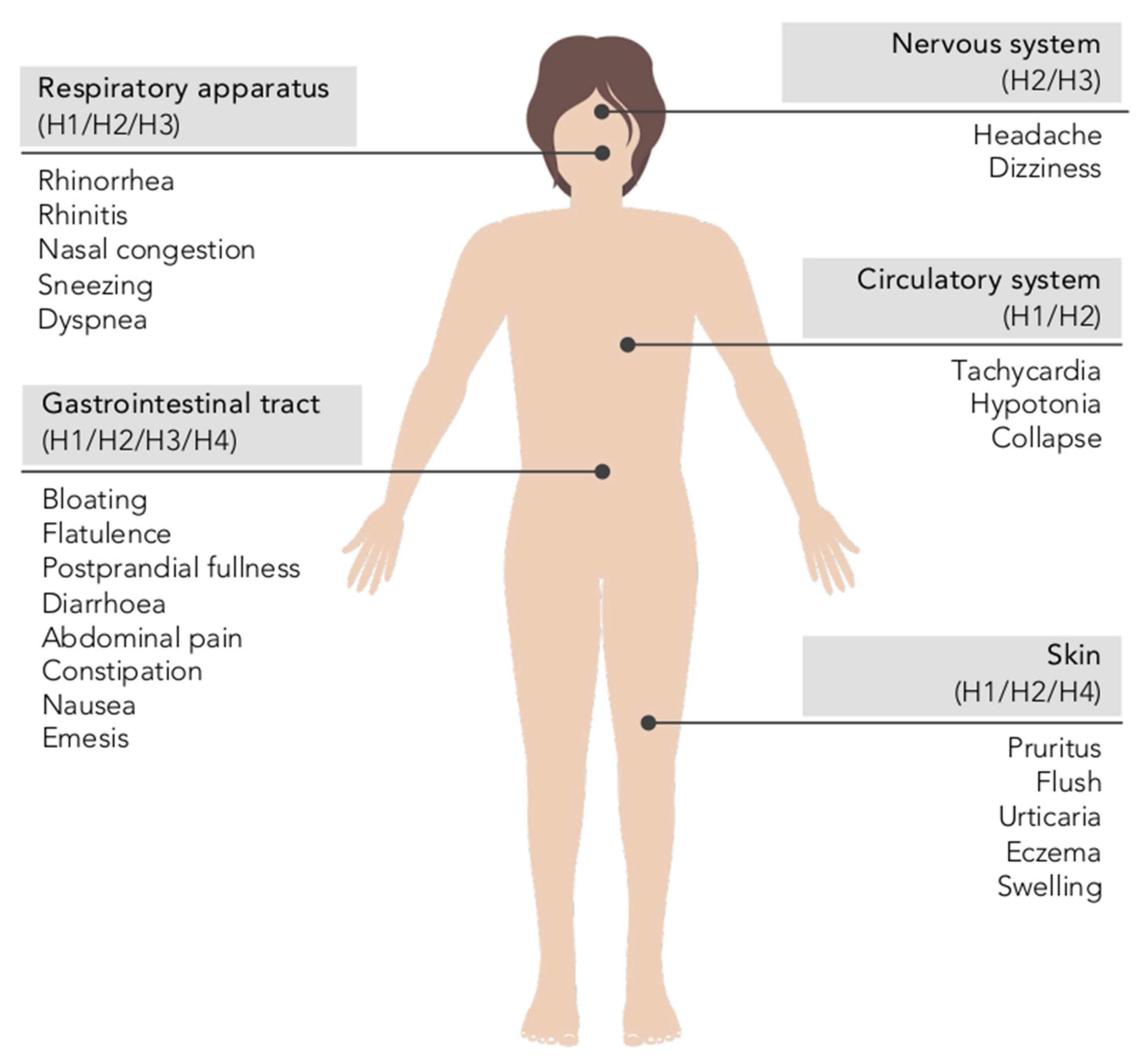

5. Histamine Intolerance

5.1. The Etiology of Histamine Intolerance

5.2. Prevalence of DAO Deficit in Persons with Symptoms Related to Histamine Intolerance

5.3. Diagnosis of Histamine Intolerance

5.4. Treatment Approaches to Histamine Intolerance

5.4.1. Low-Histamine Diet

| Design and Outcomes of the Study | Number of Patients and Symptoms | Duration | Percentage of Patients with Improvement in the Study Outcomes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prospective study with evaluation of the evolution of the symptomatology | 28 patients with chronic headache and 17 with other dermatological and respiratory symptoms | 4 weeks | 68% reduction in chronic headache and 82% reduction in other symptoms | [124] |

| Prospective study with evaluation of the evolution of symptoms, plasma histamine levels and DAO activity | 10 patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria and 19 control individuals | 3 weeks | 100% reduction in symptoms, 100% reduction in plasma histamine and no changes in DAO activity | [122] |

| Prospective study with evaluation of the evolution of symptoms, plasma histamine levels and DAO activity | 35 patients with headache and other symptoms (urticaria, arrhythmia, diarrhea and asthma) | 4 weeks | 77% reduction in symptoms, 73% increase in DAO activity and no changes in plasma histamine levels | [85] |

| Prospective study with evaluation of the evolution of symptoms and DAO activity (in five of the patients) | 17 patients with DAO deficiency, atopic eczema and other symptoms (headache, flushing and gastrointestinal symptoms) | 2 weeks | 100% reduction in symptoms and 60% (three out of five) increase in DAO activity | [86] |

| Prospective study with evaluation of the evolution of symptoms and the use of antihistamine drugs | 13 patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria and 35 control patients (without diet) | 4 weeks | Lack of improvement in symptoms and no changes in the use of antihistamines | [125] |

| Prospective study with evaluation of the evolution of the symptomatology | 36 patients with atopic dermatitis and 19 control individuals | 2 weeks | 33% reduction in symptoms | [88] |

| Prospective study with evaluation of the evolution of the symptomatology and DAO activity | 20 patients with DAO deficiency and dermatological, gastrointestinal and respiratory symptoms | 6–12 months | 100% reduction in symptoms and 100% increase in DAO activity | [83] |

| Retrospective study with evaluation of the evolution of the symptomatology | 16 pediatric patients with diffuse abdominal pain, diarrhea, headache, vomiting and rash | 4 weeks | 100% reduction of symptoms | [91] |

| Prospective study with evaluation of the evolution of the symptomatology | 16 pediatric patients with chronic abdominal pain and DAO deficiency | 4 weeks | 88% reduction of symptoms | [92] |

| Retrospective study with evaluation of the evolution of the symptomatology | 157 patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria | 4 weeks | 46% reduction of symptoms | [126] |

| Prospective study with evaluation of the evolution of the symptomatology and DAO activity | 56 patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria and gastrointestinal symptoms | 3 weeks | 75% reduction in symptoms and no changes in DAO activity | [87] |

| Prospective study with evaluation of the evolution of symptoms, plasma histamine levels and DAO activity | 22 patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria | 4 weeks | 100% reduction in symptoms, 100% reduction in plasma histamine levels and no changes in DAO activity | [112] |

| Retrospective study with evaluation of the evolution of the symptomatology and DAO activity | 63 patients with gastrointestinal symptoms | 7–18 months | 79% reduction in symptoms and 52% increase in DAO activity | [123] |

5.4.2. Exogenous DAO Supplementation

6. Conclusions and Perspectives

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards (BIOHAZ). Scientific Opinion on risk based control of biogenic amine formation in fermented foods. EFSA J. 2011, 9, 1–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windaus, A.; Vogt, W. Synthese des Imidazolyl-äthylamins. Berichte der Dtsch. Chem. Gesellschaft 1907, 40, 3691–3695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comas-Basté, O.; Luz Latorre-Moratalla, M.; Sánchez-Pérez, S.; Teresa Veciana-Nogués, M.; del Carmen Vidal-Carou, M. Histamine and Other Biogenic Amines in Food. From Scombroid Poisoning to Histamine Intolerance. In Biogenic Amines; Proestos, C., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dale, H.H.; Laidlaw, P.P. The physiological action of β-iminazolylethylamine. J. Physiol. 1910, 41, 318–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tansey, E.M. The wellcome physiological research laboratories 1894–1904: The home office, pharmaceutical firms, and animal experiments. Med. Hist. 1989, 33, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riley, J.F. Histamine and Sir Henry Dale. Br. Med. J. 1965, 1, 1488–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panula, P.; Chazot, P.L.; Cowart, M.; Gutzmer, R.; Leurs, R.; Liu, W.L.S.; Stark, H.; Thurmond, R.L.; Haas, H.L. International union of basic and clinical pharmacology. XCVIII. histamine receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 2015, 67, 601–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlieg-Boerstra, B.J.; van der Heide, S.; Oude Elberink, J.N.G.; Kluin-Nelemans, J.C.; Dubois, A.E.J. Mastocytosis and adverse reactions to biogenic amines and histamine-releasing foods: What is the evidence? Neth. J. Med. 2005, 63, 244–249. [Google Scholar]

- Russo, P.; Spano, G.; Arena, M.P.; Capozzi, V.; Fiocco, D.; Grieco, F.; Beneduce, L. Are consumers aware of the risks related to biogenic amines in food. Curr Res. Technol. Edu. Top. Appl. Microbiol. Microb. Biotechnol. 2010, 1087–1095. [Google Scholar]

- Maintz, L.; Novak, N. Histamine and histamine intolerance. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 85, 1185–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comas-Basté, O.; Latorre-Moratalla, M.L.; Bernacchia, R.; Veciana-Nogués, M.T.; Vidal-Carou, M.C. New approach for the diagnosis of histamine intolerance based on the determination of histamine and methylhistamine in urine. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2017, 145, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worm, J.; Falkenberg, K.; Olesen, J. Histamine and migraine revisited: Mechanisms and possible drug targets. J. Headache Pain 2019, 20, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovacova-Hanuskova, E.; Buday, T.; Gavliakova, S.; Plevkova, J. Histamine, histamine intoxication and intolerance. Allergol. Immunopathol. (Madr.) 2015, 43, 498–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmore, B.O.; Bollinger, J.A.; Dooley, D.M. Human kidney diamine oxidase: Heterologous expression, purification, and characterization. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2002, 7, 565–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwelberger, H.G.; Feurle, J.; Houen, G. Mapping of the binding sites of human diamine oxidase (DAO) monoclonal antibodies. Inflamm. Res. 2018, 67, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finney, J.; Moon, H.J.; Ronnebaum, T.; Lantz, M.; Mure, M. Human copper-dependent amine oxidases. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2014, 546, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehm, T.; Pils, S.; Gludovacz, E.; Szoelloesi, H.; Petroczi, K.; Majdic, O.; Quaroni, A.; Borth, N.; Valent, P.; Jilma, B. Quantification of human diamine oxidase. Clin. Biochem. 2017, 50, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwelberger, H.G.; Feurle, J.; Houen, G. Mapping of the binding sites of human histamine N-methyltransferase (HNMT) monoclonal antibodies. Inflamm. Res. 2017, 66, 1021–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwelberger, H.G. Histamine intolerance: Overestimated or underestimated? Inflamm. Res. 2009, 58, 51–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarisch, R.; Wantke, F.; Raithel, M.; Hemmer, W. Histamine and biogenic amines. In Histamine Intolerance: Histamine and Seasickness; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 3–43. ISBN 9783642554476. [Google Scholar]

- Gludovacz, E.; Maresch, D.; De Carvalho, L.L.; Puxbaum, V.; Baier, L.J.; Sützl, L.; Guédez, G.; Grünwald-Gruber, C.; Ulm, B.; Pils, S.; et al. Oligomannosidic glycans at asn-110 are essential for secretion of human diamine oxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 1070–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsenhans, B.; Hunder, G.; Strugala, G.; Schümann, K. Longitudinal pattern of enzymatic and absorptive functions in the small intestine of rats after short-term exposure to dietary cadmium chloride. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 1999, 36, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, A.P.; Hilmer, K.M.; Collyer, C.A.; Shepard, E.M.; Elmore, B.O.; Brown, D.E.; Dooley, D.M.; Guss, J.M. Structure and inhibition of human diamine oxidase. Biochemistry 2009, 48, 9810–9822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boehm, T.; Reiter, B.; Ristl, R.; Petroczi, K.; Sperr, W.; Stimpfl, T.; Valent, P.; Jilma, B. Massive release of the histamine-degrading enzyme diamine oxidase during severe anaphylaxis in mastocytosis patients. Allergy Eur. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 74, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maršavelski, A.; Petrović, D.; Bauer, P.; Vianello, R.; Kamerlin, S.C.L. Empirical Valence Bond Simulations Suggest a Direct Hydride Transfer Mechanism for Human Diamine Oxidase. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 3665–3674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smolinska, S.; Jutel, M.; Crameri, R.; O’Mahony, L. Histamine and gut mucosal immune regulation. Allergy 2014, 69, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjaastad, Ö.V. Potentiation by aminoguanidine of the sensitivity of sheep to histamine given by mouth. Effect of aminoguanidine on the urinary excretion of endogenous histamine. Q. J. Exp. Physiol. Cogn. Med. Sci. 1967, 52, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattler, J.; Häfner, D.; Klotter, H.J.; Lorenz, W.; Wagner, P.K. Food-induced histaminosis as an epidemiological problem: Plasma histamine elevation and haemodynamic alterations after oral histamine administration and blockade of diamine oxidase (DAO). Agents Actions 1988, 23, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klocker, J.; Mätzler, S.A.; Huetz, G.-N.; Drasche, A.; Kolbitsch, C.; Schwelberger, H.G. Expression of histamine degrading enzymes in porcine tissues. Inflamm. Res. 2005, 54 (Suppl. 1), S54–S57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations); WHO (World Health Organization). Public Health Risks of Histamine and other Biogenic Amines from Fish and Fishery Products. Meeting Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bover-Cid, S.; Latorre-Moratalla, M.L.; Veciana-Nogués, M.T.; Vidal-Carou, M.C. Processing Contaminants: Biogenic Amines. In Encyclopedia of Food Safety; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 2, pp. 381–391. ISBN 9780123786128. [Google Scholar]

- Vidal-Carou, M.C.; Veciana-Nogués, M.T.; Latorre-Moratalla, M.L.; Bover-Cid, S. Biogenic Amines: Risks and Control. In Handbook of Fermented Meat and Poultry; Toldrá, F., Hui, Y., Astiasarán, I., Sebranek, J., Talon, R., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 413–428. ISBN 9781118522653. [Google Scholar]

- Doeun, D.; Davaatseren, M.; Chung, M.S. Biogenic amines in foods. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2017, 26, 1463–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardini, F.; Özogul, Y.; Suzzi, G.; Tabanelli, G.; Özogul, F. Technological factors affecting biogenic amine content in foods: A review. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latorre-Moratalla, M.L.; Bover-Cid, S.; Bosch-Fusté, J.; Vidal-Carou, M.C. Influence of technological conditions of sausage fermentation on the aminogenic activity of L. curvatus CTC273. Food Microbiol. 2012, 29, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linares, D.M.; Martĺn, M.C.; Ladero, V.; Alvarez, M.A.; Fernández, M. Biogenic amines in dairy products. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2011, 51, 691–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visciano, P.; Schirone, M.; Tofalo, R.; Suzzi, G. Histamine poisoning and control measures in fish and fishery products. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladero, V.; Calles-Enriquez, M.; Fernandez, M.; Alvarez, M.A. Toxicological Effects of Dietary Biogenic Amines. Curr. Nutr. Food Sci. 2010, 6, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latorre-Moratalla, M.L.; Bover-Cid, S.; Talon, R.; Aymerich, T.; Garriga, M.; Zanardi, E.; Ianieri, A.; Fraqueza, M.J.; Elias, M.; Drosinos, E.H.; et al. Distribution of aminogenic activity among potential autochthonous starter cultures for dry fermented sausages. J. Food Prot. 2010, 73, 524–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naila, A.; Flint, S.; Fletcher, G.; Bremer, P.; Meerdink, G. Control of biogenic amines in food - Existing and emerging approaches. J. Food Sci. 2010, 75, R139–R150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latorre-Moratalla, M.L.; Comas-Basté, O.; Bover-Cid, S.; Vidal-Carou, M.C. Tyramine and histamine risk assessment related to consumption of dry fermented sausages by the Spanish population. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2017, 99, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Assessment of the incidents of histamine intoxication in some EU countries. Technical report. EFSA Support. Publ. 2017, 14, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.L. Histamine Poisoning Associated with Fish, Cheese, and Other Foods; World Health Organization Press: Geneve, Switzerland, 1985; Volume 46. [Google Scholar]

- Legroux, R.; Levaditi, J.; Segond, L. Methode de mise en evidence de l’histamine dans les aliments causes d’intoxications collectives a l’aide de l’inoculation au cobaye. C. R. Biol. 1946, 140, 863–864. [Google Scholar]

- Legroux, R.; Levaditi, J.; Bouidin, G.; Bovet, D. Intoxications histaminiques collectives consecutives a l’ingestion de thon frais. Presse Med. 1964, 54, 545–546. [Google Scholar]

- Colombo, F.M.; Cattaneo, P.; Confalonieri, E.; Bernardi, C. Histamine food poisonings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 1131–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations); WHO (World Health Organization). Histamine in Salmonids. Joint FAO/WHO Literature Review; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; ISBN 9789241514439. [Google Scholar]

- Lehane, L.; Olley, J. Histamine fish poisoning revisited. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2000, 58, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungerford, J.M. Scombroid poisoning: A review. Toxicon 2010, 56, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA); European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). The European Union summary report on trends and sources of zoonoses, zoonotic agents and food-borne outbreaks in 2017. EFSA J. 2018, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gelderen, C.E.M.; Savelkoul, T.J.F.; van Ginkel, L.A.; van Dokkum, W. The effects of histamine administered in fish samples to healthy volunteers. Clin. Toxicol. 1992, 30, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motil, K.J.; Scrimshaw, N.S. The role of exogenous histamine in scombroid poisoning. Toxicol. Lett. 1979, 3, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, S.G.O.; Bieber, T.; Dahl, R.; Friedmann, P.S.; Lanier, B.Q.; Lockey, R.F.; Motala, C.; Ortega Martell, J.A.; Platts-Mills, T.A.E.; Ring, J.; et al. Revised nomenclature for allergy for global use: Report of the Nomenclature Review Committee of the World Allergy Organization, October 2003. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2004, 113, 832–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuck, C.J.; Biesiekierski, J.R.; Schmid-Grendelmeier, P.; Pohl, D. Food Intolerances. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amon, U.; Bangha, E.; Küster, T.; Menne, A.; Vollrath, I.B.; Gibbs, B.F. Enteral histaminosis: Clinical implications. Inflamm. Res. 1999, 48, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, C.H. The disappearance of histamine from autolysing lung tissue. J. Physiol. 1929, 67, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondovì, B.; Rotilio, G.; Finazzi, A.; Scioscia-Santoro, A. Purification of pig-kidney diamine oxidase and its identity with histaminase. Biochem. J. 1964, 91, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolvekamp, M.C.J.; de Bruin, R.W.F. Diamine Oxidase: An Overview of Historical, Biochemical and Functional Aspects. Dig. Dis. 1994, 12, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwelberger, H.G.; Bodner, E. Purification and characterization of diamine oxidase from porcine kidney and intestine. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Protein Struct. Mol. Enzymol. 1997, 1340, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, T. Diamine Oxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 1950, 188, 125–136. [Google Scholar]

- Comas-Basté, O.; Latorre-Moratalla, M.L.; Rabell-González, J.; Veciana-Nogués, M.T.; Vidal-Carou, M.C. Lyophilised legume sprouts as a functional ingredient for diamine oxidase enzyme supplementation in histamine intolerance. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 125, 109201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnedl, W.J.; Lackner, S.; Enko, D.; Schenk, M.; Holasek, S.J.; Mangge, H. Evaluation of symptoms and symptom combinations in histamine intolerance. Intest. Res. 2019, 17, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinzer, T.C.; Tietz, E.; Waldmann, E.; Schink, M.; Neurath, M.F.; Zopf, Y. Circadian profiling reveals higher histamine plasma levels and lower diamine oxidase serum activities in 24% of patients with suspected histamine intolerance compared to food allergy and controls. Allergy Eur. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018, 73, 949–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnedl, W.J.; Lackner, S.; Enko, D.; Schenk, M.; Mangge, H.; Holasek, S.J. Non-celiac gluten sensitivity: People without celiac disease avoiding gluten—Is it due to histamine intolerance? Inflamm. Res. 2018, 67, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschenbach, J.R.; Honscha, K.U.; Von Vietinghoff, V.; Gäbel, G. Bioelimination of histamine in epithelia of the porcine proximal colon of pigs. Inflamm. Res. 2009, 58, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo-Casas, J.; Comas-Basté, O.; Latorre-Moratalla, M.L.; Lorente-Gascón, M.; Duelo, A.; Vidal-Carou, M.C.; Soler-Singla, L. Low serum diamine oxidase (DAO) activity levels in patients with migraine. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 74, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martín, E.; Ayuso, P.; Martínez, C.; Blanca, M.; Agúndez, J.A.G. Histamine pharmacogenomics. Pharmacogenomics 2009, 10, 867–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucher, A.N. Association of Polymorphic Variants of Key Histamine Metabolism Genes and Histamine Receptor Genes with Multifactorial Diseases. Russ. J. Genet. 2019, 55, 794–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayuso, P.; García-Martín, E.; Martínez, C.; Agúndez, J.A.G. Genetic variability of human diamine oxidase: Occurrence of three nonsynonymous polymorphisms and study of their effect on serum enzyme activity. Pharmacogenet. Genom. 2007, 17, 687–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Martín, E.; García-Menaya, J.; Sánchez, B.; Martínez, C.; Rosendo, R.; Agúndez, J.A.G. Polymorphisms of histamine-metabolizing enzymes and clinical manifestations of asthma and allergic rhinitis. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2007, 37, 1175–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, S.; Ali, A.; Siahbalaei, Y.; Ahmad, U.; Nargis, F.; Pandey, A.K.; Singh, B. Association of Diamine oxidase (DAO) variants with the risk for migraine from North Indian population. Meta Gene 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maintz, L.; Yu, C.F.; Rodríguez, E.; Baurecht, H.; Bieber, T.; Illig, T.; Weidinger, S.; Novak, N. Association of single nucleotide polymorphisms in the diamine oxidase gene with diamine oxidase serum activities. Allergy Eur. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011, 66, 893–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enko, D.; Meinitzer, A.; Mangge, H.; Kriegshaüser, G.; Halwachs-Baumann, G.; Reininghaus, E.Z.; Bengesser, S.A.; Schnedl, W.J. Concomitant Prevalence of Low Serum Diamine Oxidase Activity and Carbohydrate Malabsorption. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 2016, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondovi, B.; Fogel, W.A.; Federico, R.; Calinescu, C.; Mateescu, M.A.; Rosa, A.C.; Masini, E. Effects of amine oxidases in allergic and histamine-mediated conditions. Recent Pat. Inflamm. Allergy Drug Discov. 2013, 7, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukudome, I.; Kobayashi, M.; Dabanaka, K.; Maeda, H.; Okamoto, K.; Okabayashi, T.; Baba, R.; Kumagai, N.; Oba, K.; Fujita, M.; et al. Diamine oxidase as a marker of intestinal mucosal injury and the effect of soluble dietary fiber on gastrointestinal tract toxicity after intravenous 5-fluorouracil treatment in rats. Med. Mol. Morphol. 2014, 47, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyoshi, J.; Miyamoto, H.; Goji, T.; Taniguchi, T.; Tomonari, T.; Sogabe, M.; Kimura, T.; Kitamura, S.; Okamoto, K.; Fujino, Y.; et al. Serum diamine oxidase activity as a predictor of gastrointestinal toxicity and malnutrition due to anticancer drugs. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 30, 1582–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnedl, W.J.; Enko, D. Considering histamine in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griauzdaitė, K.; Maselis, K.; Žvirblienė, A.; Vaitkus, A.; Jančiauskas, D.; Banaitytė-Baleišienė, I.; Kupčinskas, L.; Rastenytė, D. Associations between migraine, celiac disease, non-celiac gluten sensitivity and activity of diamine oxidase. Med. Hypotheses 2020, 142, 109738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enko, D.; Kriegshäuser, G.; Halwachs-Baumann, G.; Mangge, H.; Schnedl, W.J. Serum diamine oxidase activity is associated with lactose malabsorption phenotypic variation. Clin. Biochem. 2017, 50, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitner, R.; Zoernpfenning, E.; Missbichler, A. Evaluation of the inhibitory effect of various drugs/active ingredients on the activity of human diamine oxidase in vitro. Clin. Transl. Allergy 2014, 4, P23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattler, J.; Hesterberg, R.; Lorenz, W.; Schmidt, U.; Crombach, M.; Stahlknecht, C.D. Inhibition of human and canine diamine oxidase by drugs used in an intensive care unit: Relevance for clinical side effects? Agents Actions 1985, 16, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Pérez, S.; Comas-Basté, O.; Rabell-González, J.; Veciana-Nogués, M.; Latorre-Moratalla, M.; Vidal-Carou, M. Biogenic Amines in Plant-Origin Foods: Are They Frequently Underestimated in Low-Histamine Diets? Foods 2018, 7, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mušič, E.; Korošec, P.; Šilar, M.; Adamič, K.; Košnik, M.; Rijavec, M. Serum diamine oxidase activity as a diagnostic test for histamine intolerance. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2013, 125, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzotti, G.; Breda, D.; Di Gioacchino, M.; Burastero, S.E. Serum diamine oxidase activity in patients with histamine intolerance. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2016, 29, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbrecher, I.; Jarisch, R. Histamin und kopfschmerz. Allergologie 2005, 28, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maintz, L.; Benfadal, S.; Allam, J.P.; Hagemann, T.; Fimmers, R.; Novak, N. Evidence for a reduced histamine degradation capacity in a subgroup of patients with atopic eczema. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2006, 117, 1106–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, N.; Dirk, D.; Peveling-Oberhag, A.; Reese, I.; Rady-Pizarro, U.; Mitzel, H.; Staubach, P. A Popular myth–low-histamine diet improves chronic spontaneous urticaria–fact or fiction? J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2017, 31, 650–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worm, M.; Fiedler, E.M.; Dölle, S.; Schink, T.; Hemmer, W.; Jarisch, R.; Zuberbier, T. Exogenous histamine aggravates eczema in a subgroup of patients with atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2009, 89, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, H.J.; Cho, S.I.; Kim, H.O.; Park, C.W.; Lee, C.H. Lack of association of plasma histamine with diamine oxidase in chronic idiopathic urticaria. Ann. Dermatol. 2013, 25, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honzawa, Y.; Nakase, H.; Matsuura, M.; Chiba, T. Clinical significance of serum diamine oxidase activity in inflammatory bowel disease: Importance of evaluation of small intestinal permeability. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2011, 17, 23–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosell-Camps, A.; Zibetti, S.; Pérez-Esteban, G.; Vila-Vidal, M.; Ramis, L.F.; García-Teresa-García, E.; Ferrés-Ramis, L.; García-Teresa-García, E. Intolerancia a la histamina como causa de síntomas digestivos crónicos en pacientes pediátricos. Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig. 2013, 105, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, K.M.; Gruber, E.; Deutschmann, A.; Jahnel, J.; Hauer, A.C. Histamine intolerance in children with chronic abdominal pain. Arch. Dis. Child. 2013, 98, 832–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klocker, J.; Perkmann, R.; Klein-Weigel, P.; Mörsdorf, G.; Drasche, A.; Klingler, A.; Fraedrich, G.; Schwelberger, H.G. Continuous administration of heparin in patients with deep vein thrombosis can increase plasma levels of diamine oxidase. Vascul. Pharmacol. 2004, 40, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martín, E.; Ayuso, P.; Martínez, C.; Agúndez, J.A.G. Improved analytical sensitivity reveals the occurrence of gender-related variability in diamine oxidase enzyme activity in healthy individuals. Clin. Biochem. 2007, 40, 1339–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, Y.; Shinohara, Y.; Yano, M.; Yamamoto, M.; Yoshio, M.; Satake, K.; Toda, A.; Hirai, M.; Usami, M. Effect of the menstrual cycle on serum diamine oxidase levels in healthy women. Clin. Biochem. 2013, 46, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarisch, R. Histamin-Intoleranz, Histamin und Seekrankheit, 2nd ed.; Thieme: Stuttgart, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Reese, I.; Ballmer-Weber, B.; Beyer, K.; Fuchs, T.; Kleine-Tebbe, J.; Klimek, L.; Lepp, U.; Niggemann, B.; Saloga, J.; Schäfer, C.; et al. German guideline for the management of adverse reactions to ingested histamine. Guideline of the German Society for Allergology and Clinical Immunology (DGAKI), the German Society for Pediatric Allergology and Environmental Medicine (GPA), the German Asso. Allergo J. Int. 2017, 26, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Töndury, B.; Wüthrich, B.; Schmid-Grendelmeier, P.; Seifert, B.; Ballmer-Weber, B. Histamine intolerance: Is the determination of diamine oxidase activity in the serum useful in routine clinical practice? Allergologie 2008, 31, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kofler, H.; Aberer, W.; Deibl, M.; Hawranek, T.; Klein, G.; Reider, N.; Fellner, N. Diamine oxidase (DAO) serum activity: Not a useful marker for diagnosis of histamine intolerance. Allergologie 2009, 32, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnoor, H.S.J.; Mosbech, H.; Skov, P.S.; Poulsen, L.K.; Jensen, B.M. Diamine oxidase determination in serum. Low assay reproducibility and misdassification of healthy subjects. Allergo J. 2013, 22, 108–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kofler, L.; Ulmer, H.; Kofler, H. Histamine 50-Skin-Prick Test: A Tool to Diagnose Histamine Intolerance. ISRN Allergy 2011, 2011, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, A.; Buczyłko, K.; Zielińska-Bliźniewska, H.; Wagner, W. Impaired resolution of wheals in the skin prick test and low diamine oxidase blood level in allergic patients. Postep. Dermatol. i Alergol. 2019, 36, 538–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessof, M.H.; Gant, V.; Hinuma, K.; Murphy, G.M.; Dowling, R.H. Recurrent urticaria and reduced diamine oxidase activity. Clin. Exp. Allergy 1990, 20, 373–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raithel, M.; Küfner, M.; Ulrich, P.; Hahn, E.G. The Involvement of the Histamine Degradation Pathway by Diamine Oxidase in Manifest Gastrointestinal Allergies. In Proceedings of the Inflammation Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; Volume 48, pp. 75–76. [Google Scholar]

- Kuefner, M.A.; Schwelberger, H.G.; Weidenhiller, M.; Hahn, E.G.; Raithel, M. Both catabolic pathways of histamine via histamine-N-melhyl-transferase and diamine oxidase are diminished in the colonic mucosa of patients with food allergy. Inflamm. Res. 2004, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuefner, M.A.; Schwelberger, H.G.; Hahn, E.G.; Raithel, M. Decreased histamine catabolism in the colonic mucosa of patients with colonic adenoma. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2008, 53, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wöhrl, S.; Hemmer, W.; Focke, M.; Rappersberger, K.; Jarisch, R. Histamine intolerance-like symptoms in healthy volunteers after oral provocation with liquid histamine. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2004, 25, 305–311. [Google Scholar]

- Komericki, P.; Klein, G.; Reider, N.; Hawranek, T.; Strimitzer, T.; Lang, R.; Kranzelbinder, B.; Aberer, W. Histamine intolerance: Lack of reproducibility of single symptoms by oral provocation with histamine: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled cross-over study. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2011, 123, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnedl, W.J.; Schenk, M.; Lackner, S.; Enko, D.; Mangge, H.; Forster, F. Diamine oxidase supplementation improves symptoms in patients with histamine intolerance. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2019, 28, 1779–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo-Casas, J.; Comas-Basté, O.; Latorre-Moratalla, M.L.; Lorente-Gascón, M.; Duelo, A.; Soler-Singla, L.; Vidal-Carou, M.C. Diamine oxidase (DAO) supplement reduces headache in episodic migraine patients with DAO deficiency: A randomized double-blind trial. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Mauro Martin, I.; Brachero, S.; Garicano Vilar, E. Histamine intolerance and dietary management: A complete review. Allergol. Immunopathol. (Madr.) 2016, 44, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, J.H.; Chung, B.Y.; Kim, H.O.; Park, C.W. A histamine-free diet is helpful for treatment of adult patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria. Ann. Dermatol. 2018, 30, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joneja, J.M.V.; Carmona-Silva, C. Outcome of a histamine-restricted diet based on chart audit. J. Nutr. Environ. Med. 2001, 11, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pediatrii, K.; Alergologii Dziecięcej, N.; Kacik, J. Objawy pseudoalergii a zaburzenia metabolizmu histaminy Symptoms of pseudoallergy and histamine metabolism disorders. Pediatr. i Med. Rodz. 2016, 12, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhn, L.; Störsrud, S.; Törnblom, H.; Bengtsson, U.; Simré, M. Self-Reported Food-Related Gastrointestinal Symptoms in IBS Are Common and Associated With More Severe Symptoms and Reduced Quality of Life. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 108, 634–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefèvre, S.; Astier, C.; Kanny, G. Histamine intolerance or false food allergy with histamine mechanism. Rev. Fr. Allergol. 2017, 57, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ede, G. Histamine intolerance: Why freshness matters? J. Evol. Health 2017, 2, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiss Interest Group Histamine Intolerance (SIGHI) Therapy of Histamine Intolerance. Available online: https://www.histaminintoleranz.ch/en/introduction.html (accessed on 22 July 2020).

- Vidal-Carou, M.C.; Veciana-Nogués, M.T.; Latorre-Moratalla, M.L. Intolerancia a la Histamina e Hipersensibilidad a Aditivos Alimentarios. In Nutrición y dietética clínica; Salas-Salvadó, J., Bonadai Sanjaume, A., Trallero-Casañas, R., Saló i Solà, M.E., Burgos-Peláez, R., Eds.; Elsevier: Barcelona, Spain, 2019; pp. 535–540. ISBN 9788491133032. [Google Scholar]

- Cornillier, H.; Giraudeau, B.; Samimi, M.; Munck, S.; Hacard, F.; Jonville-Bera, A.P.; Jegou, M.H.; D’acremont, G.; Pham, B.N.; Chosidow, O.; et al. Effect of diet in chronic spontaneous urticaria: A systematic review. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2019, 99, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuberbier, T.; Aberer, W.; Asero, R.; Abdul Latiff, A.H.; Baker, D.; Ballmer-Weber, B.; Bernstein, J.A.; Bindslev-Jensen, C.; Brzoza, Z.; Buense Bedrikow, R.; et al. The EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/WAO guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis and management of urticaria. Allergy Eur. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018, 73, 1393–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guida, B.; De Martino, C.D.; De Martino, S.D.; Tritto, G.; Patella, V.; Trio, R.; D’Agostino, C.; Pecoraro, P.; D’Agostino, L. Histamine plasma levels and elimination diet in chronic idiopathic urticaria. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 54, 155–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lackner, S.; Malcher, V.; Enko, D.; Mangge, H.; Holasek, S.J.; Schnedl, W.J. Histamine-reduced diet and increase of serum diamine oxidase correlating to diet compliance in histamine intolerance. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 73, 102–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wantke, F.; Götz, M.; Jarisch, R. Histamine-free diet: Treatment of choice for histamine-induced food intolerance and supporting treatment for chronical headaches. Clin. Exp. Allergy Exp. Allergy 1993, 23, 982–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, C.; Park, C.; Choi, J.; Lee, H. A study of elimination diet for chronic idiopathic urticaria in Korea. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2008, 58, AB38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebenhaar, F.; Melde, A.; Magerl, M.; Zuberbier, T.; Church, M.K.; Maurer, M. Histamine intolerance in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2016, 30, 1774–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, A.M.; Watson, R.R. Lactose Intolerance. In Nutrients in Dairy and Their Implications for Health and Disease; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 205–211. ISBN 9780128097632. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2017/2470 of 20 December 2017 establishing the Union list of novel foods in accordance with Regulation (EU) 2015/2283 of the European Parliament and of the Council on novel foods. Off. J. Eur. Union 2017, L 351, 72–201.

- Comas-Basté, O.; Latorre-Moratalla, M.L.; Sánchez-Pérez, S.; Veciana-Nogués, M.T.; Vidal-Carou, M.C. In vitro determination of diamine oxidase activity in food matrices by an enzymatic assay coupled to UHPLC-FL. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2019, 411, 7595–7602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettner, L.; Seitl, I.; Fischer, L. Evaluation of porcine diamine oxidase for the conversion of histamine in food-relevant amounts. J. Food Sci. 2020, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondovì, B.; Rotilio, G.; Costa, M.T.; Finazzi-Agrò, A.; Chiancone, E.; Hansen, R.E.; Beinert, H. Diamine oxidase from pig kidney. Improved purification and properties. J. Biol. Chem. 1967, 242, 1160–1167. [Google Scholar]

- Floris, G.; Fadda, M.B.; Pellegrini, M.; Corda, M.; Agro’, A.F. Purification of pig kidney diamine oxidase by gel-exclusion chromatography. FEBS Lett. 1976, 72, 179–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouvrette, P.; Male, K.B.; Luong, J.H.T.; Gibbs, B.F. Amperometric biosensor for diamine using diamine oxidase purified from porcine kidney. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 1997, 20, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivirand, K.; Rinken, T. Biosensors for Biogenic Amines: The Present State of Art Mini-Review. Anal. Lett. 2011, 44, 2821–2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blemur, L.; Le, T.C.; Marcocci, L.; Pietrangeli, P.; Mateescu, M.A. Carboxymethyl starch/alginate microspheres containing diamine oxidase for intestinal targeting. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2016, 63, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietrangeli, P.; Federico, R.; Mondovì, B.; Morpurgo, L. Substrate specificity of copper-containing plant amine oxidases. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2007, 101, 997–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masini, E.; Bani, D.; Marzocca, C.; Mateescu, M.A.; Mannaioni, P.F.; Federico, R.; Mondovì, B. Pea seedling histaminase as a novel therapeutic approach to anaphylactic and inflammatory disorders: A plant histaminase in allergic asthma and ischemic shock. Sci. World J. 2007, 7, 888–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Chen, H.; Gu, Z. Factors Influencing Diamine Oxidase Activity and γ-Aminobutyric Acid Content of Fava Bean (Vicia faba L.) during Germination. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 11616–11620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrigiani, P.; Serafini-Fracassini, D.; Fara, A. Diamine oxidase activity in different physiological stages of Helianthus tuberosus tuber. Plant Physiol. 1989, 89, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, P.; Srivastava, S.K. Photoregulation of Diamine Oxidase from Pea Seedlings. J. Plant Physiol. 1995, 146, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurenzi, M.; Tipping, A.J.; Marcus, S.E.; Knox, J.P.; Federico, R.; Angelini, R.; McPherson, M.J. Analysis of the distribution of copper amine oxidase in cell walls of legume seedlings. Planta 2001, 214, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavladoraki, P.; Cona, A.; Angelini, R. Copper-containing amine oxidases and FAD-dependent polyamine oxidases are key players in plant tissue differentiation and organ development. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivirand, K.; Rinken, T. Purification and properties of amine oxidase from pea seedlings. Proc. Est. Acad. Sci. Chem. 2007, 56, 164–171. [Google Scholar]

- Yacoub, M.R.; Ramirez, G.A.; Berti, A.; Mercurio, G.; Breda, D.; Saporiti, N.; Burastero, S.; Dagna, L.; Colombo, G. Diamine Oxidase Supplementation in Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria: A Randomized, Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Study. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2018, 176, 268–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Food | Histamine Content (mg/kg) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean (SD) | Median | Minimum | Maximum | |

| Fruits, vegetables and plant-based products | |||||

| Fruits | 136 | 0.07 (0.20) | ND | ND | 2.51 |

| Nuts | 41 | 0.45 (1.23) | ND | ND | 11.86 |

| Vegetables | 98 | 2.82 (7.43) | ND | ND | 69.72 |

| Legumes | 11 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Cereals | 28 | 0.12 (0.33) | ND | ND | 0.89 |

| Chocolate | 25 | 0.58 (0.44) | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.56 |

| Spices | 12 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Alcoholic beverages | |||||

| Beer | 176 | 1.23 (2.47) | 0.70 | ND | 21.60 |

| White wine | 83 | 1.24 (1.69) | 0.45 | 0.10 | 13.00 |

| Red wine | 260 | 3.81 (3.51) | 1.90 | 0.09 | 55.00 |

| Fish and seafood products | |||||

| Fresh fish | 136 | 0.79 (0.71) | ND | ND | 36.55 |

| Canned fish | 96 | 14.42 (16.03) | 5.93 | ND | 657.05 |

| Semipreserved fish | 49 | 3.48 (3.37) | 2.18 | ND | 34.90 |

| Meat and meat products | |||||

| Fresh meat | 6 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Cooked meat | 48 | 0.30 (0.26) | ND | ND | 4.80 |

| Cured meat | 23 | 12.98 (37.64) | 0.80 | ND | 150.00 |

| Dry-fermented sausages | 209 | 32.15 (14.22) | 8.03 | ND | 357.70 |

| Dairy products | |||||

| Unripened cheese | 20 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Raw milk cheese | 20 | 59.37 (106.74) | 18.38 | ND | 389.86 |

| Pasteurized milk cheese | 20 | 18.05 (38.23) | 4.59 | ND | 162.03 |

| Active Ingredient | Indication |

|---|---|

| Chloroquine | Antimalarial |

| Clavulanic acid | Antibiotic |

| Colistimethate | Antibiotic |

| Cefuroxime | Antibiotic |

| Verapamil | Antihypertensive |

| Clonidine | Antihypertensive |

| Dihydralazine | Antihypertensive |

| Pentamidine | Antiprotozoal |

| Isoniazid | Antituberculous |

| Metamizole | Analgesic |

| Diclofenac | Analgesic and anti-inflammatory |

| Acetylcysteine | Mucoactive |

| Amitriptyline | Antidepressant |

| Metoclopramide | Antiemetic |

| Suxamethonium | Muscle relaxant |

| Cimetidine | Antihistamine (H2 antagonist) |

| Prometazina | Antihistamine (H1 antagonist) |

| Ascorbic acid | Vitamin C |

| Thiamine | Vitamin B1 |

| Foods Excluded by Low-Histamine Diets | ||

|---|---|---|

| <20% * | 20–60% * | >60% * |

| Milk | Shellfish | Cured and semicured cheese |

| Lentils | Eggs | Grated cheese |

| Chickpeas | Fermented soy derivatives | Oily fish |

| Soybeans | Eggplant | Canned and semipreserved oily fish derivatives |

| Mushrooms | Avocado | Dry-fermented meat products |

| Banana | Spinach | |

| Kiwi | Tomatoes | |

| Pineapple | Fermented cabbage | |

| Plum | Citrus | |

| Nuts | Strawberries | |

| Chocolate | Wine | |

| Beer | ||

| Design | Number of Patients and Symptoms | Duration of DAO Supplementation | Efficacy Outcomes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover provocation study using histamine-containing and histamine-free tea in combination with DAO capsules or placebo | 39 patients with histamine intolerance (headache and gastrointestinal and skin complaints) | - | Statistically significant reduction of histamine-associated symptoms compared to placebo | [108] |

| Retrospective study with evaluation of the clinical response to DAO supplementation | 14 patients with diagnosis of histamine intolerance (headache and gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, respiratory and skin complaints) | 2 weeks | Reduction of at least one of the reported symptoms in 93% of patients | [84] |

| Double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study | 20 patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria | 1 month | Significant reduction of 7-Day Urticaria Activity Score (UAS-7) and slight significant reduction of daily antihistamine dose | [144] |

| Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial | 100 patients with episodic migraine and serum DAO deficit | 1 month | Significant decrease in the duration of migraine attacks and decrease in triptans intake | [110] |

| Open-label interventional pilot study | 28 patients with histamine intolerance (gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, respiratory and skin complaints) and reduced serum DAO values | 1 month of intervention and 1 month of follow-up | Significant improvement in frequency and intensity of all symptoms. 61% of patients showed slightly increase in serum DAO values. During the follow-up period (without DAO supplementation), the symptoms sum scores increased and DAO levels decreased. | [109] |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Comas-Basté, O.; Sánchez-Pérez, S.; Veciana-Nogués, M.T.; Latorre-Moratalla, M.; Vidal-Carou, M.d.C. Histamine Intolerance: The Current State of the Art. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1181. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom10081181

Comas-Basté O, Sánchez-Pérez S, Veciana-Nogués MT, Latorre-Moratalla M, Vidal-Carou MdC. Histamine Intolerance: The Current State of the Art. Biomolecules. 2020; 10(8):1181. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom10081181

Chicago/Turabian StyleComas-Basté, Oriol, Sònia Sánchez-Pérez, Maria Teresa Veciana-Nogués, Mariluz Latorre-Moratalla, and María del Carmen Vidal-Carou. 2020. "Histamine Intolerance: The Current State of the Art" Biomolecules 10, no. 8: 1181. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom10081181

APA StyleComas-Basté, O., Sánchez-Pérez, S., Veciana-Nogués, M. T., Latorre-Moratalla, M., & Vidal-Carou, M. d. C. (2020). Histamine Intolerance: The Current State of the Art. Biomolecules, 10(8), 1181. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom10081181