First and Second Law of Thermodynamics Constraints in the Lifshitz Theory of Dispersion Forces

Abstract

1. Introduction and Historical Context

2. Dispersion Forces, Engineering, and Industry

2.1. The Arnold-Hunkinger-Dransfeld Experiment

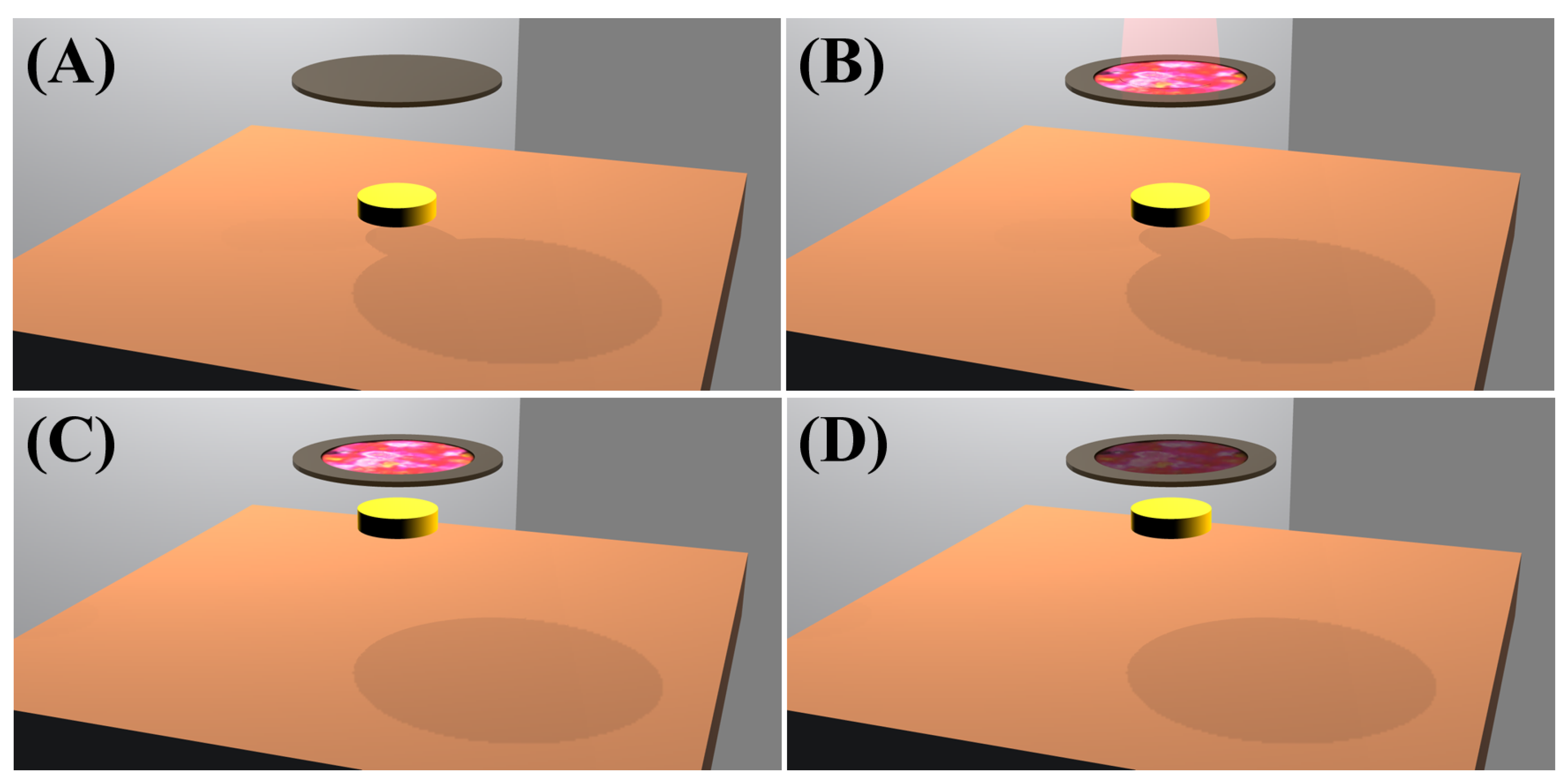

2.2. Casimir Force-Enabled Energy Storage

2.3. Casimir Force-Driven Nanodevice Actuation

“There is the problem that materials stick together by the molecular (Van der Waals) attractions. It would be like this: After you have made a part and you unscrew the nut from a bolt, it isn’t going to fall down because the gravity isn’t appreciable; it would even be hard to get it off the bolt. It would be like those old movies of a man with his hands full of molasses, trying to get rid of a glass of water. There will be several problems of this nature that we will have to be ready to design for.”

“Furthermore, it appears that the attractive force between parallel surfaces may not always have to be dealt with as a nuisance; rather, it may be manipulated to perform useful tasks just as capillary forces have been utilized to actuate MEMS components. Dynamic characteristics of the ACO may be used to design small gap resonators based on the Casimir effect.”

“Though the stiction phenomenon has been widely investigated leading to its better understanding, it has never intentionally been used in a positive way for MEMS applications.”

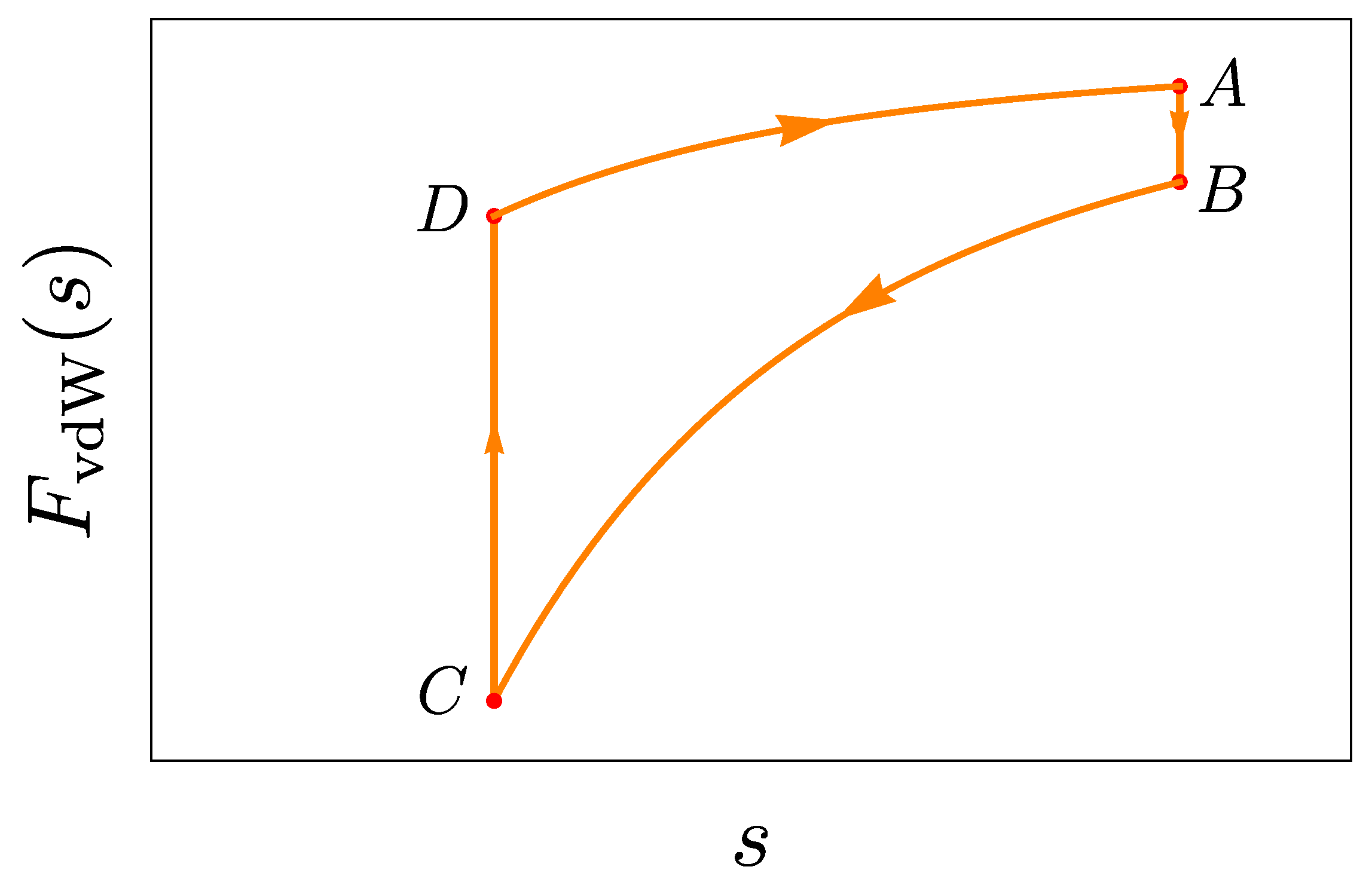

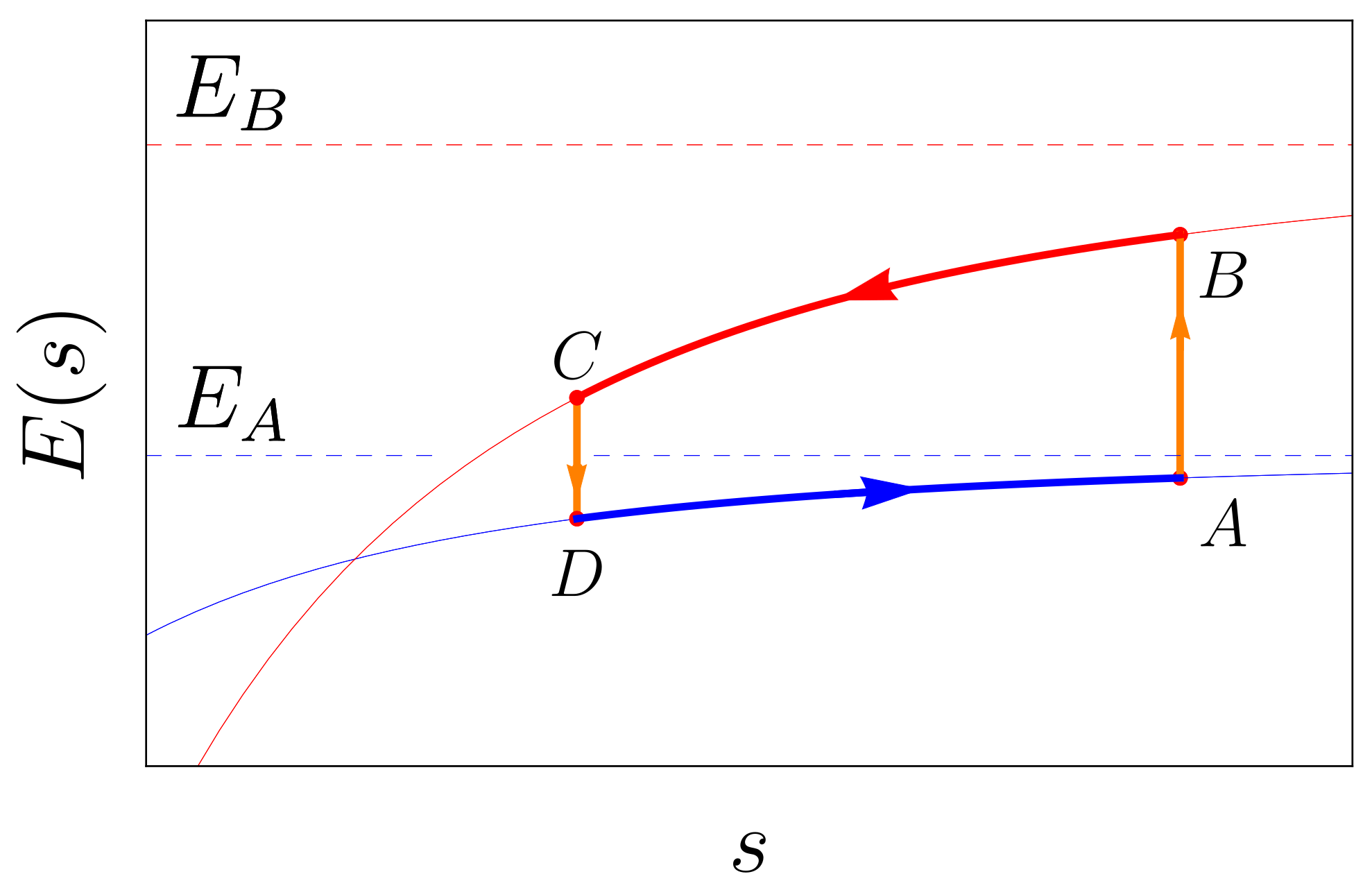

3. Dispersion Force-Enabled Thermodynamical Engine Cycles

- A.

- The former was to address Forward’s direct and crucial question [67], that is, whether or not the nature of dispersion forces is conservative. This issue was attacked by investigating whether it is possible, in principle, to achieve a non-zero net energy exchange (“energy extraction”) by introducing appropriately designed dispersion force-enabled engine cycles (Ref. [77], Sections II).

- B.

- The latter aim was to explore the possibility of driving MEMS by means of such a dispersion force modulation mechanism as that identified in the AHD experiment. In order to describe the effect of irradiation on dispersion forces, an analytical description of the dielectric functions of the semiconductor boundaries was adopted, appropriate for industrial use (Ref. [77], Sections IV–V).

3.1. Dispersion Forces and Energy Conservation

3.2. Response

3.3. Resolution

“This is the crucial point. The work we must do to recombine the electrons with the atoms is of course larger when the distance of the plates is small and it is presumably equal to the total energy released by the vacuum during the compression phase.”[118]

3.3.1. General Results: The First Law of Thermodynamics

3.3.2. General Results: The Second Law of Thermodynamics

3.3.3. Two-Level Atom-Surface Interaction

Summary 1

3.3.4. Simple Atomic Engine Cycle

Summary 2

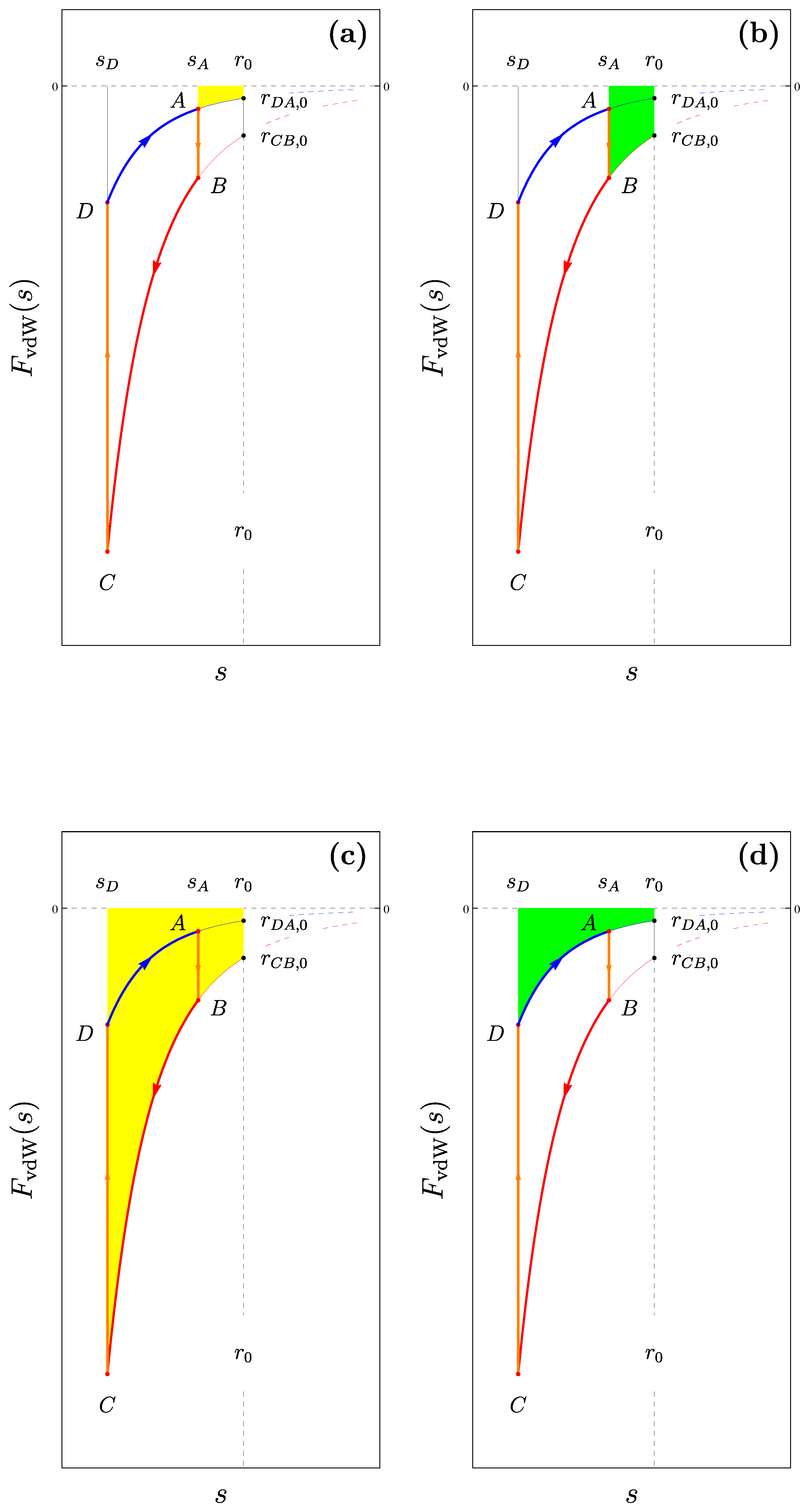

3.3.5. Engine Cycles with Macroscopic Boundaries

Summary 3

3.3.6. Plane-Sphere Boundaries

Summary 4

3.3.7. Extremely near Range Limit

- 1.

- The real temperatures are K so that the present analysis must be repeated using the more general expressions from the Lifshitz theory, involving the free energy.

- 2.

- The expressions we used for the force are perturbative results. In recent years, several theories have been proposed to obtain the exact, nonperturbative expressions for the Casimir-Polder free energy, including also the effect of a non-zero temperature, for these systems [172,173,174,175,176,177,178]. As expected, the nonperturbative Casimir-Polder force behaves differently than in the perturbative approximation at near range, thus requiring a revision of our expressions.

- 3.

4. Silence and Debates About Violations of the Laws of Thermodynamics

5. Conclusions

- 1.

- The treatments proposed herein must be generalized to the non-vanishing temperature case ( K), considering distance-dependent optical properties, and, in the atom–wall case, employing nonperturbative results.

- 2.

- What theoretical predictions can be made about the energy re-emitted at the end of the downstroke and its interactions with the cavity walls? Can such radiation be directly observed?

- 3.

- 4.

- What is the effect of out-of-equilibrium conditions on the results of this paper?

- 5.

- What is the effect of fluctuations on the results of this paper?

- 6.

- To what extent do thermodynamical considerations alone constrain the general mathematical form of any non-perturbative dispersion force law?

- 7.

- What experiments can be carried out to detect any force law modifications connected to the issues raised in this paper?

- 8.

- What is the anticipated technological impact on nano-device performance of those same modifications?

- 9.

- Are there different regimes or systems in which violations of the First and Second Laws of Thermodynamics reappear?

- 10.

- How can these results valid for illuminated semiconductors be extended to completely different strategies for dispersion force modulation?

“From the experimental perspective, …still very few aspects of stochastic quantum thermodynamics have been tested in the laboratory.”

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- A Year Full of Quantum Celebrations. Nat. Photon. 2025, 19, 117. [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, K. The Revolutionary Dawn of Quantum Mechanics. Nature 2025, 637, 269–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jammer, M. The Philosophy of Quantum Mechanics; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Quantum Mechanics at 100: An Unfinished Revolution. Nature 2025, 637, 251–252. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michelson, A.A. The Department of Physics. In Annual Register. July, 1895–July, 1896, with Announcements for 1896-7; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1896; pp. 159–162. [Google Scholar]

- Lagemann, R. Michelson on Measurement. Am. J. Phys. 1959, 27, 182–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millikan, R.A. The Autobiography of Robert Millikan; Prentice-Hall, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, F. Dispersion Force Engineering. The Long Path from Hooked Atoms to next-Generation Spacecraft. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 54, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boltzmann, L. Lectures on Gas Theory; Dover Publications, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Boltzmann, L. Theoretical Physics and Philosophical Problems; D. Reidel Publishing Company: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Derjaguin, B.V.P.N. Lebedev’s Ideas on the Nature of Molecular Forces. Sov.-Phys.-Uspekhi [Transl. Uspekhi Fiz. Nauk.] 1967, 10, 108–111. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, B. Molecular Forces, Based on the Baker Lectures of Peter J. W. Debye; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Margenau, H.; Kestner, N.R. Theory of Intermolecular Forces, 2nd ed.; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1971; pp. 1–400. [Google Scholar]

- Mahanti, J. Dispersion Forces; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Rowlinson, J.S. Cohesion—A Scientific History of Intermolecular Forces; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002; pp. 1–333. [Google Scholar]

- London, F. The General Theory of Molecular Forces. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1937, 33, 8–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, V.V.; Forman, P. Why Was It Schrödinger Who Developed de Broglie’s Ideas? Hist. Stud. Phys. Sci. 1969, 1, 291–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jammer, M. The Conceptual Development of Quantum Mechanics; McGraw-Hill Book Company: New York, NY, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Renn, J. Schrödinger and the Genesis ofWave Mechanics. In Erwin Schrödinger—50 Years After; Reiter, W.L., Yngvason, J., Eds.; European Mathematical Society: Helsinki, Finland, 2013; pp. 9–36. [Google Scholar]

- de Broglie, L. Recherches Sur La Théorie Des Quanta. Ann. Phys. 1925, 10, 22–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heisenberg, W. Über Quantentheoretische Umdeutung Kinematischer Und Mechanischer Beziehungen. Z. Phys. 1925, 33, 879–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heisenberg, W. Quantum-Theoretical Re-Interpretation of Kinematic and Mechanical Relations. In Sources of Quantum Mechanics; van der Waerden, B.L., Ed.; Dover Publications, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1968; pp. 261–276. [Google Scholar]

- Born, M.; Heisenberg, W.; Jordan, P. Zur Quantenmechanik. II. Z. Phys. 1926, 35, 557–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Waerden, B.L. (Ed.) Sources of Quantum Mechanics; Dover Publications, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Darrigol, O. The Origin of Quantized Matter Waves. Hist. Stud. Phys. Biol. Sci. 1986, 16, 197–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger, E. Quantisierung Als Eigenwertproblem. Erste Mitteilung. Ann. Phys. 1926, 79, 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger, E. Quantisierung Als Eigenwertproblem. Zweite Mitteilung. Ann. Phys. 1926, 79, 489–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger, E. Quantisierung Als Eigenwertproblem. Dritte Mitteilung. Ann. Phys. 1926, 80, 437–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger, E. Quantisierung Als Eigenwertproblem. Vierte Mitteilung. Ann.Phys. 1926, 81, 109–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger, E. Collected Papers on Wave Mechanics; Blackie & Son Limited: London, UK, 1928. [Google Scholar]

- Newton, I. Newton’s Principia (Translated into English by Andrew Motte), 1st ed.; Daniel Adee: New York, NY, USA, 1687. [Google Scholar]

- Krupp, H. Particle Adhesion: Theory and Experiment. Advan. Colloid Interface Sci. 1967, 1, 111–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, G. Molecular Cohesion. London, Edinburgh, Dublin Philos. Mag. J. Sci. 1928, 6, 695–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.C. Die Gegenseitige Einwirkung Zweier Wasserstoffatome. Phys. Z. 1927, 28, 663–666. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.C. The Problem of the Normal Hydrogen Molecule in the New Quantum Mechanics. Phys. Rev. 1928, 31, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- London, F. Die Bedeutung Der Quantentheorie Ffir Die Chemie. Die Naturwissenschaften 1929, 17, 516–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenschitz, R.V.; London, F. Uber Das Verhaltnis Der van Der Waalsschen Krafte Zu Den Homoopolaren Bindungskraften. Z. Phys. 1930, 60, 491–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drude, P. The Theory of Optics; Longmans, Green, and Co.: London, UK, 1902; pp. 1–588. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, R.S. The Cohesive Force between Solid Surfaces and the Surface Energy of Solids. Phil. Mag. 1932, 13, 853–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennard-Jones, J.E. Processes of Adsorption and Diffusion on Solid Surfaces. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1932, 28, 333–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, J.H. The Influence of van Der Waals Forces and Primary Bonds on Binding Energy, Strength and Special Reference to Some Artificial Resins. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1936, 32, 10–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamaker, H. The London-van Der Waals Attraction between Spherical Particles. Physica 1937, 4, 1058–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verwey, E.J.W.; Overbeek, J.T.G. Theory of the Stability of Lyophobic Colloids; Elsevier Publishing Company, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Casimir, H.B.G.; Polder, D. The Influence of Retardation on the London-van Der Waals Forces. Phys. Rev. 1948, 73, 360–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casimir, H.B.G. Some Main Lines of 50 Years of Philips Research in Physics. In An Anthology of Philips Research; Casimir, H.B.G., Gradstein, S., Eds.; N. V. Philips’ Gloeilampenfabrieken: Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 1966; pp. 81–92. [Google Scholar]

- Casimir, H.B.G. On the Attraction between Two Perfectly Conducting Plates. Proc. Kon. Ned. Akad. Wetenshap 1948, 51, 793–795. [Google Scholar]

- Casimir, H.B.G. Van Der Waals Forces and Zero Point Energy. In Physics of Strong Fields; Greiner, W., Ed.; Springer: Bellingham, WA, USA, 1987; pp. 957–964. [Google Scholar]

- Casimir, H.B.G. Van Der Waals Forces and Zero Point Energy. In Essays in Honour of Victor Frederick Weisskopf (Physics and Society); Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 53–66. [Google Scholar]

- Casimir, H.B.G. Some Remarks on the History of the So-Called Casimir Effect. In The Casimir Effect 50 Years Later: Proceedings of the Fourth Workshop on Quantum Field Theory Under the Influence of External Conditions, Leipzig, Germany, 14–18 September 1998; Bordag, M., Ed.; World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd.: Singapore, 1999; pp. 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Lifshitz, E.M. The Theory of Molecular Attractive Forces between Solids. Sov. Phys. JETP 1956, 2, 73–83. [Google Scholar]

- Dzyaloshinskii, I.; Lifshitz, E.M.; Pitaevskii, L.P. The General Theory of van Der Waals Forces. Adv. Phys. 1961, 10, 165–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milonni, P.W. The Quantum Vacuum; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bordag, M.; Klimchitskaya, G.L.; Mohideen, U.; Mostepanenko, V.M. Advances in the Casimir Effect; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hunklinger, S. Bestimmung Der van Der Waals-Krafte Zwischen Makroskopischen Korpern Mit Einer Neuen Hochempfindlichen Methode. Ph.D. Thesis, Technischen Hochschule München, München, Germany, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, W. Das Verhalten Der Elektromagnetischen Nullpunktenergie Und Die van Der Waals-Kraft Zwischen Halbleitenden Oberflächen. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Hochschule München, München, Germany, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Hunklinger, S.; Geisselman, H.; Arnold, W. A Dynamic Method for Measuring the van Der Waals Forces between Macroscopic Bodies. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 1972, 43, 584–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, W.; Hunklinger, S.; Dransfeld, K. Influence of Optical Absorption on the Van Der Waals Interaction between Solids. Phys. Rev. B 1979, 19, 6049–6056, Erratum in Phys. Rev. B 1980, 21, 1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Mohideen, U.; Klimchitskaya, G.L.; Mostepanenko, V.M. Experimental Test for the Conductivity Properties from the Casimir Force between Metal and Semiconductor. Phys. Rev. A 2006, 74, 022103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chen, F.; Klimchitskaya, G.L.; Mostepanenko, V.M.; Mohideen, U. Control of the Casimir Force by the Modification of Dielectric Properties with Light. Phys. Rev. B 2007, 76, 035338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Klimchitskaya, G.L.; Mostepanenko, V.M.; Mohideen, U. Demonstration of Optically Modulated Dispersion Forces. Opt. Express 2007, 15, 4823–4829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimchitskaya, G.L.; Mohideen, U.; Mostepanenko, V.M. Control of the Casimir Force Using Semiconductor Test Bodies. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 2011, 25, 171–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, F. Membrane Actuation by Casimir Force Manipulation. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 2008, 41, 164033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, F. The Economics of van Der Waals Force Engineering. In Proceedings of the Space Technology and Applications Int. Forum (STAIF-2008), AIP Conf. Proc. 969, Albuquerque, NW, USA, 10–14 February 2008; El-Genk, M.S., Ed.; Melville: New York, NY, USA, 2008; Volume 969, pp. 959–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, F. The Future of van Der Waals Force Enabled Technology-Transfer into the Aerospace Marketplace. In Nanotube Superfiber Materials, Science to Commercialization; Schulz, M.J., Shanov, V.N., Yin, J., Cahay, M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 729–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, F. Engines Powered by the Forces between Atoms. Am. Sci. 2014, 102, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimchitskaya, G.L.; Mohideen, U.; Mostepanenko, V.M. Pulsating Casimir Force. J. Phys. A 2007, 40, F841–F847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forward, R.L. Extracting Electrical Energy from the Vacuum by Cohesion of Charged Foliated Conductors. Phys. Rev. B 1984, 30, 1700–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forward, R.L. Alternate Propulsion Energy Sources, Final Report for the Period 3 March 1983 to 21 September 1983, AFRPL TR-83-067; Technical report; Air Force Rocket Propulsion Laboratory: Edwards Air Force Base, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Forward, R.L. Alternate Propulsion Energy Sources, Final Report for the Period 3 March 1983 to 23 September 1983, F04611-83-C-0013; Technical Report March; Air Force Rocket Propulsion Laboratory: Edwards Air Force Base, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, F. Energy Storage from Dispersion Forces in Nanotubes. In Nanotube Superfiber Materials: Changing Engineering Design; Schulz, M., Shanov, V.N., Zhangzhang, Y., Eds.; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Chapter 27; pp. 789–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feynman, R.P. There’s Plenty of Room at the Bottom. J. Microelectromech. Syst. 1992, 1, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serry, F.M.; Walliser, D.; Maclay, G. The Anharmonic Casimir Oscillator (ACO)-the Casimir Effect in a Model Microelectromechanical System. J. Microelectromech. Sys. 1995, 4, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulyanov, S.V.; Yamafuji, K.; Fukuda, T.; Arai, F.; Rizzotto, G.G.; Pagni, A. Quantum and Thermodynamic Self-Organization Conditions for Artificial Life of Biological Mobile Micro-Nano-Robot with AI Control. (Report 2. Methodology of R&D and Stochastic Dynamic). In Proceedings of the MHS’96 Proceedings of the Seventh International Symposium on Micro Machine and Human Science, Nagoya, Japan, 2–4 October 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, N. Nanostructures in Motion: Micro-Instruments for Moving Nanometer-Scale Objects. In Nanotechnology; Timp, G., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 89–159. [Google Scholar]

- Millis, M.G. Prerequisites for Space Drive Science. In Frontiers of Propulsion Science; Progress in Astronautics and Aeronautics; Millis, M.G., Davis, E.W., Eds.; AIAA: Reston, VA, USA, 2009; Volume 227, pp. 127–174. [Google Scholar]

- Millis, M.G. NASA Breakthrough Propulsion Physics Program. Acta Astronaut. 1999, 44, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, F. Engine Cycle of an Optically Controlled Vacuum Energy Transducer. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 60, 14740–14755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serry, F.M.; Walliser, D.; Maclay, G. The Role of the Casimir Effect in the Static Deflection and Stiction of Membrane Strips in Microelectromechanical Systems (MEMS). J. Appl. Phys. 1998, 84, 2501–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buks, E.; Roukes, M.L. Metastability and the Casimir Effect in Micromechanical Systems. Europhys. Lett. 2001, 54, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buks, E.; Roukes, M.L. Stiction, Adhesion Energy, and the Casimir Effect in Micromechanical Systems. Phys. Rev. B 2001, 63, 033402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.B.; Aksyuk, V.; Kleiman, R.; Bishop, D.; Capasso, F. Nonlinear Micromechanical Casimir Oscillator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001, 87, 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.B.; Aksyuk, V.A.; Kleiman, R.N.; Bishop, D.J.; Capasso, F. Quantum Mechanical Actuation of Microelectromechanical Systems by the Casimir Force. Science 2001, 291, 1941–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, R.K. Resistance to the Systematic Study of Multiple Discoveries in Science. Eur. J. Sociol. 1963, 4, 237–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, R.K. The Sociology of Science; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA; ; London, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Corigliano, A. Surface Interactions. In Mechanics of Microsystems; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 351–391. [Google Scholar]

- Agache, V.; Buchaillot, L.; Quévy, E.; Collard, D. Stiction-Controlled Locking System for Three-Dimensional Self-Assembled Microstructures: Theory and Experimental Validation. In Proceedings of the Proc. Design, Test, Integration, and Packaging of MEMS/MOEMS 2001, Cannes-Mandelieu, France, 25–27 April 2001; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2001; Volume 4408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agache, V.; Quévy, E.; Collard, D.; Buchaillot, L. Stiction-Controlled Locking System for Three-Dimensional Self-Assembled Microstructures: Theory and Experimental Validation. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2001, 79, 3869–3871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, E.J. Quantum Stickiness Put to Use. Ind. Phys. 2001, 7, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, K. A Tiny Force of Nature Is Stronger than Thought, Friday. New York Times, 9 February 2001; p. A17. [Google Scholar]

- Spengen, W.M.V.; Puers, R.; Wolf, I.D. A Physical Model to Predict Stiction in MEMS. J. Micromechanics Microengineering 2002, 12, 702–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, F. Gravimetry by Nanoscale Parametric Amplifiers Driven by Radiation-Induced Dispersion Force Modulation. In Proceedings of the 2021 Scientific Assembly of the International Association of Geodesy, Beijing, China, 28 June–2 July 2021; Freymüller, J.T., Sánchez, L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 154, pp. 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, F. Spacecraft Accelerometry with Parametric Nanoamplifiers Pumped by Radiation-Induced Dispersion Force Modulation. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 10th International Workshop on Metrology for AeroSpace (MetroAeroSpace), Milan, Italy, 19–21 June 2023; pp. 336–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, F. Radiation-Pumped, Dispersion Force-Driven Nanoscale Accelerometers: Progress in Autonomous Navigation Simulations of Solar Sail Missions to Mars (Accepted, to Appear). In Proceedings of the 17th Marcel Grossmann Meeting, Pescara, Italy, 7–12 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, F. Casimir Forces: Fundamental Theory, Computation, and Nanodevice Applications. In Quantum Nano-Photonics, NATO Science for Peace and Security Series B: Physics and Biophysics (Erice, Sicily, Italy); Springer Nature B. V.: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 149–180. [Google Scholar]

- Forward, R.L. Apparent Endless Extraction of Energy from the Vacuum by Cyclic Manipulation of Casimir Cavity Dimensions. In Proceedings of the NASA Breakthrough Propulsion Physics Workshop ProceedingsNASA Lewis Research Center, Cleveland, OH, USA, 12–14 August 1997. [Google Scholar]

- London, F. Uber Einige Eigenschaften Und Anwendungen Der Molekularkrafte. Z. Phys. Chem. B 1930, 11, 222–251. [Google Scholar]

- Planck, M. Über Die Begründung Des Gesetzes Der Schwarzen Strahlung. Ann. Phys. 1912, 342, 642–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A.; Stern, O. Einige Argumente Für, Die Annahme Einer Molekularen Agitation Beim Absoluten Nullpunkt. Ann. Phys. 1913, 345, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, T.S. Black-Body Theory and the Quantum Discontinuity; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA; London, UK, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg, S. The Cosmological Constant Problem. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1989, 61, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, S. Is the Zero-Point Energy Real? In Ontological Aspects of Quantum Field Theory; Kuhlmann, M., Lyre, H., Wayne, A., Eds.; World Scientific: Hackensack, NJ, USA, 2002; pp. 313–343. [Google Scholar]

- Enz, C.P. Is the Zero-Point Energy Real? In Physical Reality and Mathematical Description; Enz, C.P., Mehra, J., Eds.; D. Reidel Publishing Company: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1974; pp. 124–132. [Google Scholar]

- Rugh, S.E.; Zinkernagel, H.; Cao, T.Y. The Casimir Effect and the Interpretation of the Vacuum. Stud. Hist. Philos. Sci. Part Stud. Hist. Philos. Mod. Phys. 1999, 30, 111–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugh, S.E.; Zinkernagel, H. The Quantum Vacuum and the Cosmological Constant Problem. Stud. Hist. Philos. Mod. Phys. 2002, 33, 663–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milton, K.A. The Casimir Effect: Recent Controversies and Progress. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 2004, 37, R209–R277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, R.L. The Casimir Effect and the Quantum Vacuum. Phys. Rev. D 2005, 72, 021301(R). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugh, S.E.; Zinkernagel, H. Quantum vacuum fluctuations and the cosmological constant. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 2007, 40, 6647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolić, H. Proof That Casimir Force Does Not Originate from Vacuum Energy. Phys. Lett. B 2016, 761, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolić, H. Is Zero-Point Energy Physical? A Toy Model for Casimir-like Effect. Ann. Phys. 2017, 383, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, T.H. Retarded van Der Waals Forces at All Distances Derived from Classical Electrodynamics with Classical Electromagnetic Zero-Point Radiation. Phys. Rev. A 1973, 7, 1832–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, T.H. The Classical Vacuum. Sci. Am. 1985, 253, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puthoff, H.E. The Energetic Vacuum: Implications for Energy Research. Specul. Sci. Technol. 1990, 13, 247–257. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, D.C.; Puthoff, H.E. Extracting Energy and Heat from the Vacuum. Phys. Rev. E 1993, 48, 1562–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, E.W.; Puthoff, H.E. On Extracting Energy from the Quantum Vacuum. In Frontiers of Propulsion Science; Progress in Astronautics and Aeronautics; Millis, M.G., Davis, E.W., Eds.; AIAA: Reston, VA, USA, 2009; Volume 227, pp. 569–603. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, D.C. Two New Methods in Stochastic Electrodynamics for Analyzing the Simple Harmonic Oscillator and Possible Extension to Hydrogen. Physics 2023, 5, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergia, S.; Lugli, P.; Zamboni, N. Zero-Point Energy, Planck’s Law, and the Prehistory of Stochastic Electrodynamics. Part II: Einstein and Stern’s Paper of 1913. Ann. Fond. Louis Broglie 1980, 5, 39–62. [Google Scholar]

- Yam, P. Exploiting Zero-Point Energy. Sci. Am. 1997, 277, 82–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scandurra, M. Thermodynamic Properties of the Quantum Vacuum. arXiv, 2001; arXiv:hep-th/0104127. [Google Scholar]

- Inui, N. Temperature Dependence of the Casimir Force between Silicon Slabs. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2003, 72, 2198–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemansky, M.W.; Dittman, R.H. Heat and Thermodynamics, 7th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Landau, L.D.; Lifshitz, E.M. Quantum Mechanics—Non-Relativistic Theory, 2nd ed.; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1965; pp. 1–632. [Google Scholar]

- Lorentz, H.A. The Theory of Electrons; Dover Publications, Inc.: Mineola, NY, USA, 1952; pp. 1–343. [Google Scholar]

- Semak, V.V.; Shneider, M.N. Invicem Lorentz Oscillator Model (ILOM). arXiv 2017, arXiv:1709.02466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semak, V.V.; Shneider, M.N. Analysis of Harmonic Generation by a Hydrogen-like Atom Using a Quasi-Classical Non-Linear Oscillator Model with Realistic Electron Potential. Osa Contin. 2019, 2, 2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinshelwood, C.N. The Structure of Physical Chemistry; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Karplus, M.; Porter, R.N. Atoms & Molecules; The Benjamin/Cummings Publishing Company: Menlo Park, CA, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Kleppner, D. With Apologies to Casimir. Phys. Today 1990, 43, 9–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taddei, M.M.; Mendes, T.N.; Farina, C. Subtleties in Energy Calculations in the Image Method. Eur. J. Phys. 2009, 30, 965–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taddei, M.M.; Mendes, T.N.; Farina, C. An Introduction to Dispersive Interactions. Eur. J. Phys. 2010, 31, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Melo e Souza, R.; Kort-Kamp, W.J.M.; Sigaud, C.; Farina, C. Sommerfeld’s Image Method in the Calculation of van Der Waals Forces. Int. J. Mod. Phys. Conf Ser. 2012, 14, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Melo e Souza, R.; Kort-Kamp, W.J.M.; Sigaud, C.; Farina, C. Image Method in the Calculation of the van Der Waals Force between an Atom and a Conducting Surface. Am J. Phys. 2013, 81, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Tannoudji, C.; Diu, B.; Laloë, F.; Van Der Waals, F. Quantum Mechanics; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1977; pp. 1130–1140. [Google Scholar]

- Kittel, C.; Knight, W.D.; Ruderman, M.A. Berkeley Physics Course Vol. 1 (Mechanics), 2nd ed.; McGraw Hill Book Company: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Arfken, G. Mathematical Methods for Physicists, 3rd ed.; Academic Press, Inc.: Orlando, FL, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Fowles, G.L.; Cassiday, G.L. Analytical Mechanics; Thomson Brooks/Cole: Belmont, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fermi, E. Thermodynamics; Dover Publications, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, G. Quantum-Electrodynamic Level. Shifts between Parallel Mirrors: Applications, Mainly to Rydberg States. Proc. Roy. Soc. Series A 1987, 410, 175–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.; Haroche, S.; Hinds, E.A.; Jhe, W.; Meschede, D. Measuring the van Der Waals Forces between a Rydberg Atom and a Metallic Surface. Phys. Rev. A 1988, 37, 3594–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Born, M.; Wolf, E. Principles of Optics, 4th ed.; Pergamom Press: Oxford, UK, 1970; pp. 1–859. [Google Scholar]

- Aspnes, D.E. Local Field Effects and Effect Medium Theory—A Microscopic Perspective. Am. J. Phys. 1982, 50, 704–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannay, J.H. The Clausius-Mossotti Equation: An Alternative Derivation. Eur. J. Phys. 1983, 4, 141–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsegian, V.A. Van Der Waals Forces; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Israelachvili, J.N. Intermolecular and Surface Forces, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: Waltham, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- van Kampen, N.G.; Nijboer, B.R.A.; Schram, K. On the Macroscopic Theory of van Der Waals Forces. Phys. Lett. A 1968, 26, 307–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupp, H.; Sandstede, G.; Schramm, K.H. Beitraege Zur Entwicklung Des Chemischen Apparatewesens. Dechema Monograph. 1960, 38, 115–147. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, J.D. Classical Electrodynamics, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Shadowitz, A. The Electromagnetic Field; Dover Publications, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Zangwill, A. Modern Electrodynamics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, F.S.J. Berkeley Physics Course Vol. 3. Waves.; McGraw-Hill: Newton, MA, USA, 1968; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Reif, F. Fundamentals of Statistical and Thermal Physics; Waveland Press: Long Grove, IL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Inui, N. Numerical Study of Enhancement of the Casimir Force between Silicon Membranes by Irradiation with UV Laser. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2004, 73, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, M.J.; Shapiro, H.N.; Boettner, D.D.; Bailey, M.B. Fundamentals of Engineering Thermodynamics, 8th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Derjaguin, B.V. Untersuchungen Uber Die Reibung Und Adhesion, IV. Koll. Ztschr. 1934, 69, 155–164. [Google Scholar]

- Derjaguin, B.V.; Titijevskaia, A.S.; Abricossova, I.I.; Malkina, A.D. Investigations of the Forces of Interaction of Surfaces in Different Media and Their Application to the Problem of Colloid Stability. Discuss. Faraday Soc. 1954, 18, 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derjaguin, B.V.; Abrikosova, I.I. Direct Measurement of the Molecular Attraction of Solid Bodies I. Statement of the Problem and Method of Measuring Forces by Using Negative Feedback. Sov. Phys. JETP 1957, 3, 819–829. [Google Scholar]

- Derjaguin, B.V. The Force between Molecules. Sci. Am. 1960, 203, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derjaguin, B.V.; Rabinovich, Y.I.; Churaev, N.V. Direct Measurement of Molecular Forces. Nature 1978, 272, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressi, G.; Carugno, G.; Onofrio, R.; Ruoso, G. Measurement of the Casimir Force between Parallel Metallic Surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002, 88, 041804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamoreaux, S.K. Demonstration of the Casimir Force in the 0.6 to 6 μm Range. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997, 78, 5–8, Erratum in Phys. Rev. Lett. 1998, 81, 5475–5476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamoreaux, S.K. Reanalysis of Casimir Force Measurements in the 0.6-to-6-μm Range. Phys. Rev. A 2010, 82, 024102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamoreaux, S.K. Progress in Experimental Measurements of the Surface— Surface Casimir Force: Electrostatic Calibrations and Limitations to Accuracy. In Casimir Physics. Springer Lecture Notes in Physics 834; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 219–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamoreaux, S.K. The Casimir Force and Related Effects: The Status of the Finite Temperature Correction and Limits on New Long-Range Forces. Annu. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 2012, 62, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamoreaux, S.K. The Casimir Force: Background, Experiments, and Applications. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2005, 68, 201–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamoreaux, S.K. Casimir Forces: Still Surprising after 60 Years. Phys. Today 2007, 60, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, A.W.; Ibanescu, M.; Iannuzzi, D.; Joannopoulos, J.D.; Johnson, S.G. Virtual Photons in Imaginary Time: Computing Exact Casimir Forces via Standard Numerical Electromagnetism Techniques. Phys. Rev. A 2007, 76, 032106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, F. Improved Finite-Difference Computation of the van Der Waals Force: One-dimensional Case. Phys. Rev. A 2009, 80, 042113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.G. Numerical Methods for Computing Casimir Interactions. In Casimir Physics, Lecture Notes in Physics 834; Dalvit, D., Milonni, P., Roberts, D., da Rosa, F., Eds.; Springe: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 175–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derjaguin, B.V.; Abrikosova, I.I.; Lifshitz, E.M. Direct Measurement of Molecular Attraction between Solid Separated by a Narrow Gap. Q. Rev. Chem. Soc. 1956, 10, 295–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blocki, J.; Randrup, J.; Swiatecki, W.J.; Tsang, C.F. Proximity Forces. Ann. Phys. 1977, 105, 427–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scardicchio, A.; Jaffe, R.L. Casimir Effects: An Optical Approach I. Foundations and Examples. Nucl. Phys. B 2005, 704, 552–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esquivel-Sirvent, R.; Reyes, L.; Bárcenas, J. Stability and the Proximity Theorem in Casimir Actuated Nano Devices. New J. Phys. 2006, 8, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordag, M.; Klimchitskaya, G.L.; Mostepanenko, V.M. Nonperturbative Theory of Atom-Surface Interaction: Corrections at Short Separations. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2018, 30, 055003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordag, M. Casimir and Casimir-Polder Forces with Dissipation from First Principles. Phys. Rev. A 2017, 96, 062504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, P.R.; Ford, G.W.; Milonni, P.W. Nonperturbative Calculation of the London—van Der Waals Interaction Potential. Phys. Rev. A 2014, 89, 022127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, P.R.; Ford, G.W.; Milonni, P.W. Coupled-Oscillator Theory of Dispersion and Casimir-Polder Interactions. J. Chem. Phys. 2014, 141, 164105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passante, R.; Rizzuto, L.; Spagnolo, S.; Tanaka, S.; Petrosky, T.Y. Harmonic Oscillator Model for the Atom-Surface Casimir-Polder Interaction Energy. Phys. Rev. A 2012, 85, 062109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhmann, S.Y.; Welsch, D.G. Casimir–Polder Forces on Excited Atoms in the Strong Atom–Field Coupling Regime. Phys. Rev. A 2008, 77, 012110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhmann, S.Y.; Knöll, L.; Welsch, D.G.; Ho, D.T. Casimir-Polder Forces: A Nonperturbative Approach. Phys. Rev. A 2004, 70, 052117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Góger, S.; Karimpour, M.R.; Karimpour, M.R. Four-Dimensional Scaling of Dipole Polarizability: FromSingleParticle Models toAtoms and Molecules. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2024, 2024, 6621–6631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antao, T.V.; Peres, N.M. The Polarizability of a Confined Atomic System: An Application of the Dalgarno-Lewis Method. Eur. J. Phys. 2021, 42, 045407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, C.; Galatry, L. The Effective Polarizability of an Atom near a Metal Surface; van Der Waals and Non-Local Effects. Surf. Sci. 1984, 141, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meixner, W.C.; Antoniewicz, P.R. Effect of Atomic Size on the Effective Polarizability of Physisorbed Atoms. Phys. Status Solidi (B) 1978, 86, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meixner, W.C.; Antoniewicz, P.R. Effective Polarizability of Polarizable Atoms near Metal Surfaces. Phys. Rev. B 1976, 13, 3276–3282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, W.; Liao, Q.; Zhang, C.; He, J. Micro-/Nanoscaled Irreversible Otto Engine Cycle with Friction Loss and Boundary Effects and Its Performance Characteristics. Energy 2010, 35, 4658–4662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriet, L.; Jordan, A.N.; Hur, K.L. Electrical Current from Quantum Vacuum Fluctuations in Nano-Engines. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 92, 125306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benenti, G.; Casati, G.; Saito, K.; Whitney, R.S. Fundamental Aspects of Steady-State Conversion of Heat to Work at the Nanoscale. Phys. Rep. 2017, 694, 1–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, F.; Corra, L.A.; Gogolin, C.; Anders, J.; Adesso, G. Thermodynamics in the Quantum Regime; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 195. [Google Scholar]

- Mayrhofer, R.D.; Elouard, C.; Splettstoesser, J.; Jordan, A.N. Stochastic Thermodynamic Cycles of a Mesoscopic Thermoelectric Engine. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 103, 075404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jussiau, É.; Bresque, L.; Auffèves, A.; Murch, K.W.; Jordan, A.N. Many-Body Quantum Vacuum Fluctuation Engines. Phys. Rev. Res. 2023, 5, 033122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, J.C. A Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism, 2nd ed.; Henry Frowde: London, UK, 1881; Volume I. [Google Scholar]

- Jeans, J.H. The Mathematical Theory of Electricity and Magnetism, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1911. [Google Scholar]

- Reitz, J.R.; Frederick, J. Milford. Foundations of Electromagnetic Theory; Addison-Wesley Publishing Company: Reading, MA, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, D.J. Introduction to Electrodynamics; Prentice-Hall, Inc.: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1999; pp. 1–576. [Google Scholar]

- Boykin, T.B.; Hite, D.; Singh, N. The Two-Capacitor Problem with Radiation. Am. J. Phys. 2002, 70, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choy, T.C. Capacitors Can Radiate: Further Results for the Two-Capacitor Problem. Am. J. Phys. 2004, 72, 662–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milsom, J.A. Untold Secrets of the Slowly Charging Capacitor. Am. J. Phys. 2020, 88, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mita, K.; Boufaida, M. Ideal Capacitor Circuits and Energy Conservation. Am. J. Phys. 1999, 67, 737–739, Erratum in Am. J. Phys. 2000, 68, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangopadhyaya, A.; Mallow, J.V. Comment on “Ideal Capacitor Circuits and Energy Conservation,” by K. Mita and M. Boufaida [Am. J. Phys. 67 (8), 737-739 (1999)]. Am. J. Phys. 2000, 68, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panofsky, W.K.H.; Phillips, M. Classical Electricity and Magnetism, 2nd ed.; Addison-Wesley Publ. Co., Inc.: Reading, MA, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Zemansky, M.W.; Dittman, R.H. Heat and Thermodynamics, 5th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, E.N. How to Transform, with a Capacitor, Thermal Energy into Usable Work. Eur. J. Phys. 2010, 31, 1457–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggins, R.A. Energy Storage, 1st ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- D’Abramo, G. Thermo-Charged Capacitors and the Second Law of Thermodynamics. Phys. Lett. A 2010, 374, 1801–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earman, J.; Norton, J.D. Exorcist XIV: The Wrath of Maxwell’s Demon. Part I. From Maxwell to Szilard. Stud. Hist. Phil. Mod. Phys. 1998, 29, 435–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caves, C.M. Quantitative Limits on the Ability of a Maxwell Demon to Extract Work from Heat. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1990, 64, 2111–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddox, J. Maxwell’s Demon Flourishes. Nature 1990, 345, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmels, Y. Thermodynamics in the Presence of Electromagnetic Fields. Phys. Rev. E 1995, 52, 1452–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmels, Y. Thermodynamics of Electroquasistatic Systems: The Parallel Plate Capacitor. J. Electrost. 1996, 38, 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmels, Y. Storage of Electromagnetic Field Energy in Matter. Eur. Phys. J. D 2002, 21, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.H. Thermodynamic Pressure and Mechanical Pressure for Electromagnetic Media. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2409.01203. [Google Scholar]

- Čapek, V.; Sheehan, D.P. Challenges to the Second Law of Thermodynamics; Theory and Experiment; Fundamental Theories of Physics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; Volume 146. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan, D.; Gross, D.H.E. Extensivity and the Thermodynamic Limit: Why Size Really Does Matter. Phys. A 2006, 370, 461–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, D.P. The Second Law of Thermodynamics: Foundations and Status. Found. Phys. 2007, 37, 1653–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond, C. Finding a Balance between Anarchy and Orthodoxy. In Proceedings of the Evaluation Methods for Machine Learning Workshop at the 25th ICML, Helsinki, Finland, 5–9 July 2008; National Research Council of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Falkenburg, B. Particle Metaphysics: A Critical Account of Subatomic Reality; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jabs, A. Quantum Mechanics in Terms of Realism. Phys. Essays 1996, 95, 36–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, M. Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science; Dover Publications, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1957; pp. 1–384. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, H.; Bartlett, A.; Galindo, L.I.R.; Collins, H.; Reyes-Galindo, L. Demarcating Fringe Science for Policy. Perspect. Sci. 2017, 25, 411–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo, L.I.R. The Sociology of Theoretical Physics. Ph.D. Thesis, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mulkay, M.; Gilbert, G.N. Joking Apart: Some Recommendations Concerning the Analysis of Scientific Culture. Soc. Stud. Sci. 1982, 12, 585–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baez, J. The Crackpot Index. A Simple Method for Rating Potentially Revolutionary Contributions to Physics. 1998. Available online: http://math.ucr.edu/home/baez/crackpot.html (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Siegel, W. Are You a Quack? Available online: http://insti.physics.sunysb.edu/~siegel/quack.html (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Thérèse, S.; Martin, B. Shame, Scientist! Degradation Rituals in Science. Prometheus 2010, 28, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, T.S. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, 2nd ed.; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1970; Volume I and II. [Google Scholar]

- Feyerabend, P. Against Method, 4th ed.; Verso Books: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich, H.J. Some Observations on the Neglect of the Sociology of Science. Philos. Sci. 1962, 29, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo, L.I.R. Controversias En El Efecto Casimir. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City, Mexico, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, B. Strategies for Dissenting Scientists. J. Sci. Explor. 1998, 12, 605–616. [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen, R.A. Thought Experiments. Am. Sci. 1991, 79, 250–263. [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen, R.A. Thought Experiments; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Gooding, D.C. What Is Experimental about Thought Experiments? In PSA: Proceedings of the Biennial Meeting of the Philosophy of Science Association; The Universit yof Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1992; Volume 1992, pp. 280–290. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, E.W.; Teofilo, V.L.; Haisch, B.; Puthoff, H.E.; Nickisch, L.J.; Rueda, A.; Cole, D.C. Review of Experimental Concepts for Studying the Quantum Vacuum Field. In Proceedings of the Space Technology and Applications International Forum AIP Conference Proceedings STAIF, Albuquerque, NM, USA, 12–16 February 2006; Volume 813, pp. 1390–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moddel, G.; Dmitriyeva, O. Extraction of Zero-Point Energy from the Vacuum: Assessment of Stochastic Electrodynamics-Based Approach as Compared to Other Methods. Atoms 2019, 7, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ţiplea, G.; Simaciu, I.; Milea, P.L.; Şchiopu, P. Extraction of Energy from the Vacuum in SED: Theoretical and Technological Models and Limitations. U.P.B. Sci. Bull. Series A 2021, 83, 267–286. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan, D.P. Casimir Chemistry. J. Chem. Phys 2009, 131, 104706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, H.; March, P.; Lawrence, J.; Vera, J.; Sylvester, A.; Brady, D.; Bailey, P. Measurement of Impulsive Thrust from a Closed Radio-Frequency Cavity in Vacuum. J. Propul. Power 2016, 33, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajmar, M.; Neunzig, O.; Weikert, M. High-Accuracy Thrust Measurements of the EMDrive and Elimination of False-Positive Effects. CEAS Space J. 2022, 14, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esquivel-Sirvent, R.; Villarreal, C.; Cocoletzi, G.H. Superlattice-Mediated Tuning of Casimir Forces. Phys. Rev. A 2001, 64, 052108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esquivel-Sirvent, R.; Villarreal, C.; Noguez, C. Casimir Forces Between Thermally Activated Nanocomposites. MRS Online Proc. Libr. 2001, 703, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inui, N. Casimir Force between a Metallic Sphere and a Semiconductive Plate Illuminated with Gaussian Beam. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2006, 75, 024004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inui, N. Change in the Casimir Force between Semiconductive Bodies by Irradiation. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2007, 89, 012018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inui, N. Optical Switching of a Graphene Mechanical Switch Using the Casimir Effect. J. Appl. Phys. 2017, 122, 104501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, F. Advances in the Formulation of Minimal Thermodynamically Consistent Models for Dispersion Force-Driven High-Accuracy Inertial Nano-Sensors. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 12th International Workshop on Metrology for AeroSpace (MetroAeroSpace), Naples, Italy, 18–20 June 2025; pp. 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, F. Nanopropulsion from High-Energy Particle Beams via Dispersion Forces in Nanotubes (AIAA-2012-3713). In Proceedings of the 48th AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference (JPC) & Exhibit, Atlanta, GA, USA, 30 July–1 August 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, F. Reflectance Modulation by Free-Carrier Exciton Screening in Semiconducting Nanotubes. J. Appl. Phys. 2013, 114, 024310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzano, G.; Zambrini, R. Quantum Thermodynamics under Continuous Monitoring: A General Framework. AVS Quantum Sci. 2022, 4, 025302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekola, J.P.; Solinas, P.; Shnirman, A.; Averin, D.V. Calorimetric Measurement of Work in a Quantum System. New J. Phys. 2013, 15, 115006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solinas, P.; Amico, M.; Zanghì, N. Measurement of Work and Heat in the Classical and Quantum Regimes. Phys. Rev. A 2021, 103, l060202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinjanampathy, S.; Anders, J. Quantum Thermodynamics. Contemp. Phys. 2016, 57, 545–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gittes, F. Two Famous Results of Einstein Derived from the Jarzynski Equality. Am. J. Phys. 2018, 86, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, G. On the Fluctuations of the Casimir Force. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 1991, 24, 991–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, G. On the Fluctuations of the Casimir Force: II. The Stress-Correlation Function. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 1991, 24, 5533–5551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaekel, M.t.; Reynaud, S. Fluctuations and Dissipation for a Mirror in Vacuum. Quantum Opt. 1992, 4, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.h.; Kuo, C.i.; Ford, L.H. Fluctuations of the Retarded van Der Waals Force. Phys. Rev. A 2002, 65, 062102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Messina, R.; Passante, R. Fluctuations of the Casimir-Polder Force between an Atom and a Conducting Wall. Phys. Rev. A 2007, 76, 032107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deffner, S. ; Steve Campbell. Quantum Thermodynamics; Morgan & Claypool Publishers: San Rafael, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Eglinton, J.; Carollo, F.; Lesanovsky, I.; Brandner, K. Stochastic Thermodynamics at the Quantum-Classical Boundary: A Self-Consistent Framework Based on Adiabatic-Response Theory. Quantum 2024, 8, 1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, F. Nanomechanical Sensing of Gravitational Wave-Induced Casimir Force Perturbations. Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 2014, 23, 1442001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, F. Gravitational-Wave Detection by Dispersion Force Modulation in Nanoscale Parametric Amplifiers. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2016, 718, 072004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, F. Gravitational-Wave Response of Parametric Amplifiers Driven by Radiation-Induced Dispersion Force Modulation. In Proceedings of the Fourteenth Marcel Grossmann Meeting on General Relativity, Rome, Italy, 12–18 July 2015; Bianchi, M., Jantzen, R.T., Ruffini, R., Eds.; World Scientific: Singapore, 2017; pp. 3175–3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pinto, F. First and Second Law of Thermodynamics Constraints in the Lifshitz Theory of Dispersion Forces. Atoms 2025, 13, 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/atoms13110087

Pinto F. First and Second Law of Thermodynamics Constraints in the Lifshitz Theory of Dispersion Forces. Atoms. 2025; 13(11):87. https://doi.org/10.3390/atoms13110087

Chicago/Turabian StylePinto, Fabrizio. 2025. "First and Second Law of Thermodynamics Constraints in the Lifshitz Theory of Dispersion Forces" Atoms 13, no. 11: 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/atoms13110087

APA StylePinto, F. (2025). First and Second Law of Thermodynamics Constraints in the Lifshitz Theory of Dispersion Forces. Atoms, 13(11), 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/atoms13110087