In the Quest for Cosmic Rotation

Abstract

1. Introduction

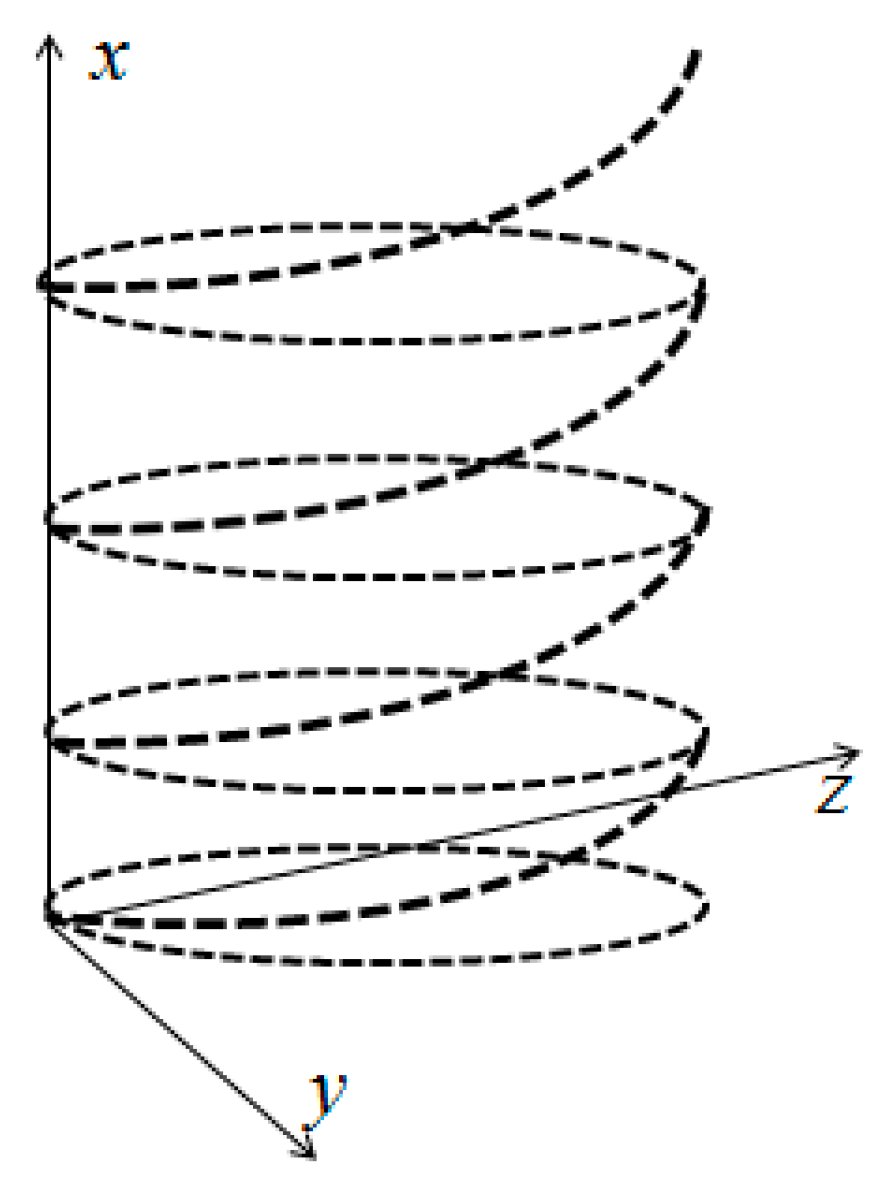

2. Metric and Matter vs. Dark Energy and Oscillating Physics

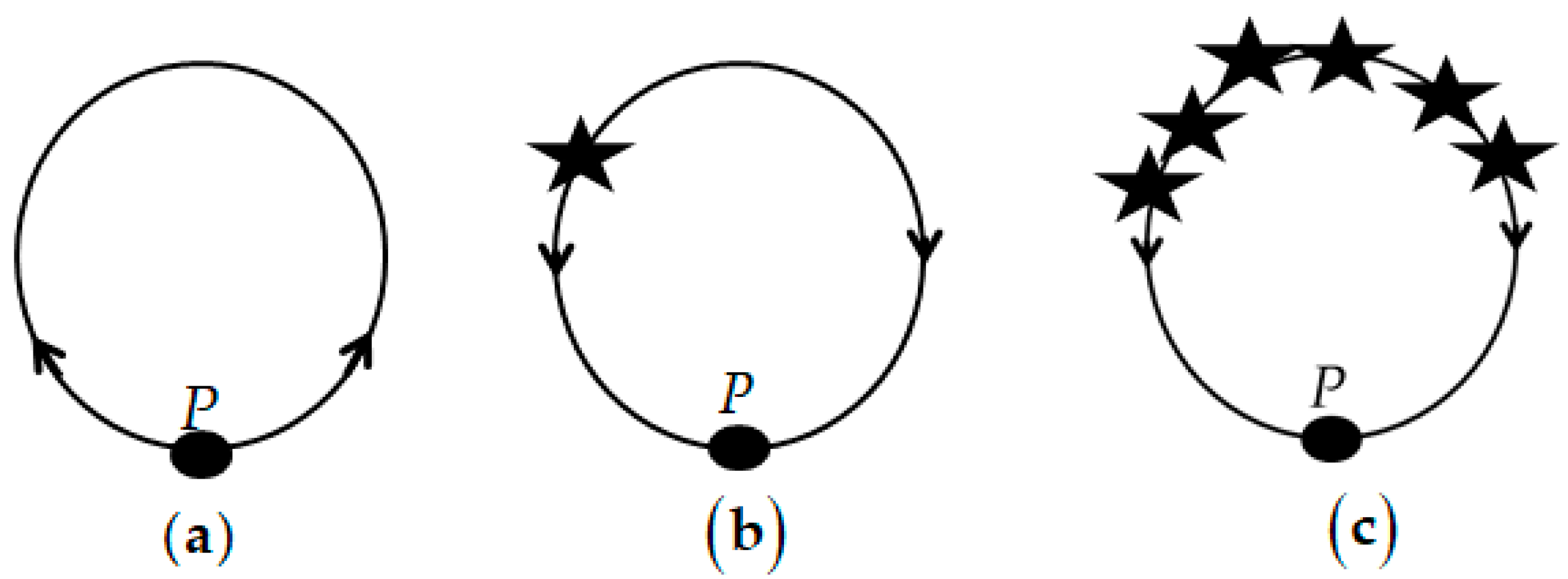

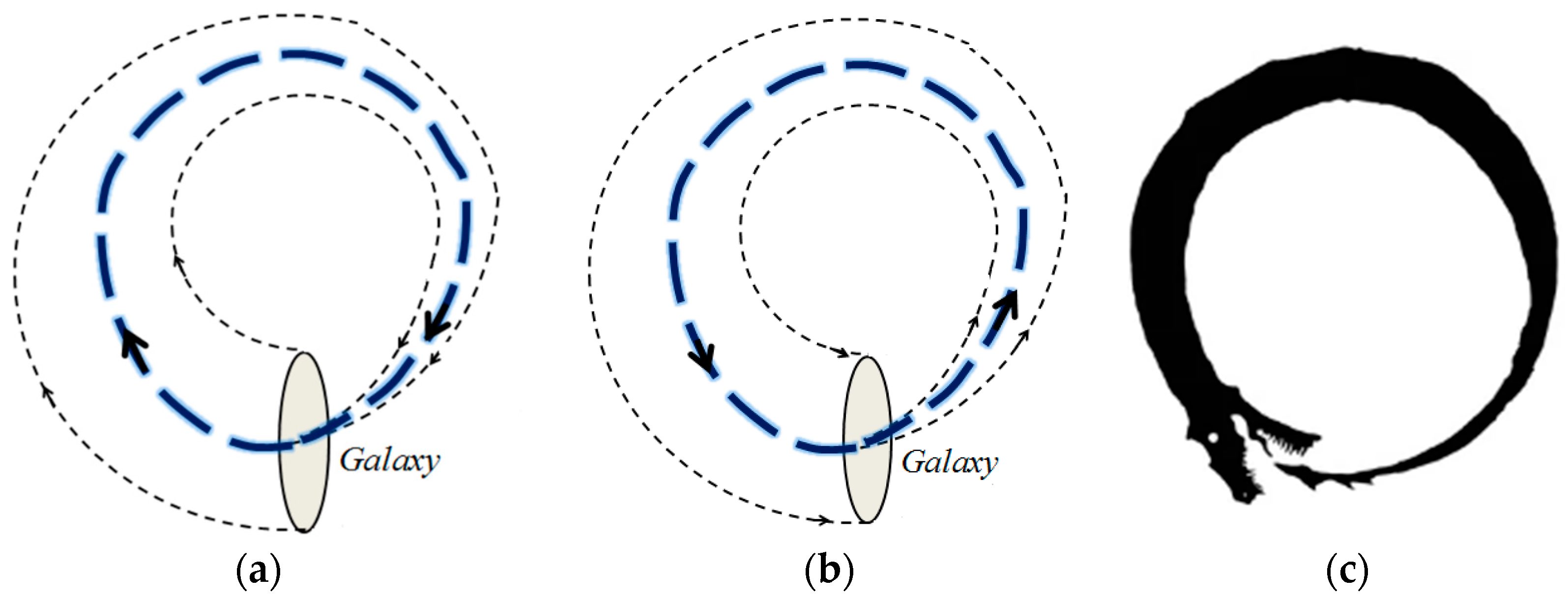

3. In the Theoretical Quest for Cosmic Rotation

4. In the Experimental Quest for Cosmic Rotation

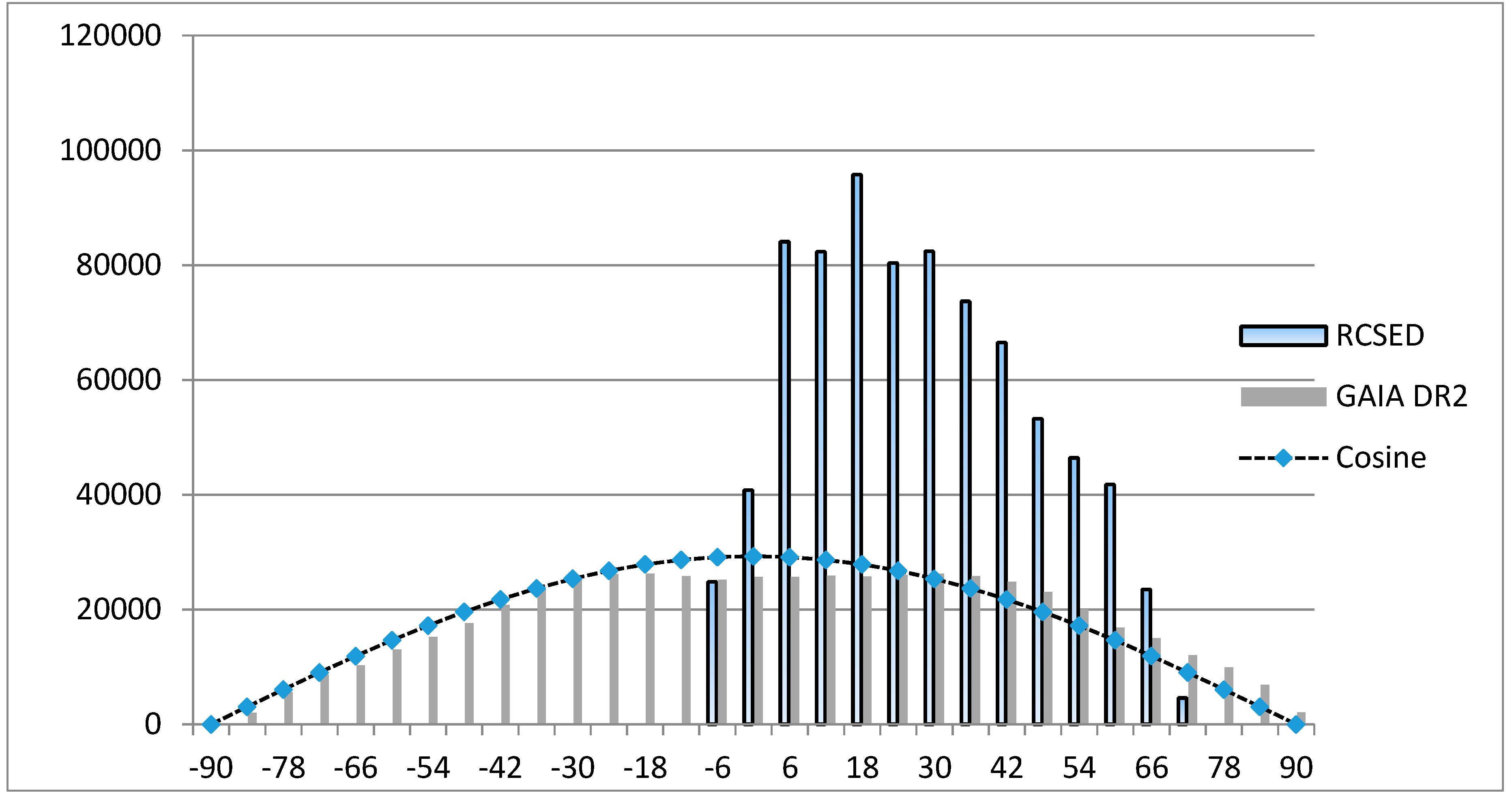

4.1. RCSED (Reference Catalog of Spectral Energy Distributions of Galaxies) Catalog

4.2. Kuminski and Shamir Catalogs

4.3. GAIA Data Release 2 Quasar Catalog

4.4. Milliquas 6.3 Catalog

4.5. KQCG (Known Quasars Catalog for GAIA Mission)

5. Numerical Experiments

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Id SDSS DR7 | Ra | Dec | z | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | 587727177915301989 | 6.31801788 | −11.12899674 | 0.164466 |

| 587734894366425177 | 186.3215957 | 11.12945461 | 0.167687 | |

| (2) | 587727177911304300 | 356.9463884 | −11.1131664 | 0.11336 |

| 587734894362427519 | 176.9362082 | 11.12183186 | 0.10569 | |

| (3) | 587727177915367567 | 6.473508 | −11.08978967 | 0.109483 |

| 587734894366490714 | 186.4752183 | 11.09098806 | 0.103002 | |

| (4) | 587727225157451822 | 9.78490157 | −10.97586123 | 0.0656358 |

| 587732772669292660 | 189.7803892 | 10.98178272 | 0.0667346 | |

| (5) | 587727177921069125 | 19.65932903 | −10.93368609 | 0.141083 |

| 588017569241432335 | 199.6689547 | 10.93044205 | 0.145941 | |

| (6) | 587727177921069119 | 19.64324854 | −10.90207866 | 0.140991 |

| 588017569241432309 | 199.6421776 | 10.89885453 | 0.149119 | |

| (7) | 587727225157779575 | 10.47400922 | −10.89314855 | 0.115176 |

| 587732772669554736 | 190.4693767 | 10.88349483 | 0.113392 | |

| (8) | 587727873696006248 | 354.4140938 | −10.76728771 | 0.0980759 |

| 587732772662673520 | 174.4078391 | 10.76580767 | 0.0941737 | |

| (9) | 587727178450665633 | 2.84320186 | −10.72060849 | 0.0626986 |

| 587734893828112436 | 182.834768 | 10.72901371 | 0.0684232 | |

| (10) | 587727178453483585 | 9.28275768 | −10.70100563 | 0.130024 |

| 587734893830864981 | 189.2821245 | 10.70562335 | 0.128155 | |

| (11) | 587727178451452024 | 4.57186615 | −10.67135056 | 0.061156 |

| 587734893828833380 | 184.568407 | 10.66631434 | 0.0513871 | |

| (12) | 587727225693536361 | 7.83605949 | −10.59958384 | 0.0905357 |

| 587732772131569821 | 187.8259964 | 10.59469904 | 0.0927822 | |

| (13) | 587727229447962769 | 23.72675428 | −10.51170548 | 0.0992561 |

| 587736543623839915 | 203.7347943 | 10.50510464 | 0.103054 | |

| (14) | 587727178458333267 | 20.61377325 | −10.47315078 | 0.109546 |

| 587736543622529169 | 200.6164952 | 10.48116533 | 0.10888 | |

| (15) | 587727229448028286 | 23.8634114 | −10.4420383 | 0.0872344 |

| 587736543623905435 | 203.8644965 | 10.44923329 | 0.083543 | |

| (16) | 587727874233335894 | 355.4913684 | −10.41356256 | 0.0980471 |

| 587732772126261484 | 175.4967819 | 10.419777 | 0.106774 | |

| (17) | 587727178459644099 | 23.56363216 | −10.30676641 | 0.087484 |

| 588017992299970676 | 203.560364 | 10.29826366 | 0.0842322 | |

| (18) | 587727874232942672 | 354.5407195 | −10.2905162 | 0.115404 |

| 587732772125802696 | 174.5311941 | 10.29906788 | 0.112148 | |

| (19) | 587727178989240463 | 6.75089715 | −10.28452672 | 0.141096 |

| 587734893292879988 | 186.7541572 | 10.2905859 | 0.138833 | |

| (20) | 587727178459775095 | 23.99049618 | −10.24662329 | 0.16844 |

| 588017992300167307 | 203.9854969 | 10.23670831 | 0.159882 | |

| (21) | 587727178992320618 | 13.92268478 | −10.23798263 | 0.0545347 |

| 588017991758970941 | 193.9286925 | 10.23919618 | 0.0576316 | |

| (22) | 587726877275324641 | 341.4198226 | −10.22775339 | 0.0854893 |

| 587732772657037548 | 161.4250258 | 10.2288603 | 0.0864014 | |

| (23) | 587727178459775058 | 23.95379218 | −10.20892227 | 0.170874 |

| 588017992300167290 | 203.9605329 | 10.21263285 | 0.16155 | |

| (24) | 587727178459775059 | 23.9542841 | −10.20863418 | 0.167602 |

| 588017992300167290 | 203.9605329 | 10.21263285 | 0.16155 | |

| (25) | 587727178992386152 | 14.00945119 | −10.16938834 | 0.0582089 |

| 588017991758971000 | 194.0154632 | 10.17011785 | 0.0547655 | |

| (26) | 587727178983473249 | 353.3035011 | −10.11314013 | 0.175384 |

| 587734893287112784 | 173.3054337 | 10.10802598 | 0.171464 | |

| (27) | 587730815751291175 | 336.940361 | −9.95373677 | 0.0563963 |

| 587734864295166164 | 156.9394599 | 9.94507402 | 0.046747 | |

| (28) | 587727179526701090 | 8.03597019 | −9.91194747 | 0.0790208 |

| 587734892756598903 | 188.0361662 | 9.91573124 | 0.0763644 | |

| (29) | 587727178995335253 | 20.82821245 | −9.86158021 | 0.128453 |

| 588017991761920153 | 200.8255428 | 9.86031309 | 0.125208 | |

| (30) | 587730815750045949 | 334.0325931 | −9.85353658 | 0.349603 |

| 588017702382403743 | 154.0277586 | 9.85157764 | 0.356585 | |

| (31) | 587727178996449304 | 23.51060112 | −9.77414538 | 0.0408057 |

| 588017991763099797 | 203.5206978 | 9.78398572 | 0.0398321 | |

| (32) | 587730815749980360 | 334.0089931 | −9.76351938 | 0.0919012 |

| 588017702382403698 | 154.016896 | 9.76374758 | 0.0834979 | |

| (33) | 587727179531354122 | 18.84193042 | −9.69197199 | 0.0623454 |

| 588017991224197282 | 198.8506924 | 9.7002904 | 0.0665447 | |

| (34) | 587727230521311310 | 22.64387404 | −9.63632312 | 0.121776 |

| 587736542549704781 | 202.645084 | 9.64360108 | 0.123518 | |

| (35) | 587730815749128409 | 331.9847156 | −9.62353845 | 0.105015 |

| 587735342655471787 | 151.9840169 | 9.63233216 | 0.114253 | |

| (36) | 587730815748866357 | 331.395196 | −9.60640427 | 0.0800119 |

| 587735342655209578 | 151.3870255 | 9.60693788 | 0.0783352 | |

| (37) | 587726877811934142 | 340.8324856 | −9.59191986 | 0.439336 |

| 587732772119904870 | 160.8394092 | 9.59742067 | 0.433453 | |

| (38) | 587730816827326649 | 342.3741793 | −9.56574501 | 0.0821777 |

| 587746210520367211 | 162.3699937 | 9.56609192 | 0.0862479 | |

| (39) | 587727230522163362 | 24.74103715 | −9.56325433 | 0.0862579 |

| 587736542550556886 | 204.7496386 | 9.55691982 | 0.0868169 | |

| (40) | 587727177929457776 | 39.13882791 | −9.51991056 | 0.081008 |

| 588017702410453175 | 219.1457622 | 9.51836998 | 0.088222 | |

| (41) | 587727180061868049 | 4.08337588 | −9.46368127 | 0.0872652 |

| 587734892218023997 | 184.0819229 | 9.45884063 | 0.094822 | |

| (42) | 587727230522425495 | 25.33108177 | −9.42130098 | 0.104163 |

| 587736542550818989 | 205.3372284 | 9.41874675 | 0.0996079 | |

| (43) | 587727177929785591 | 39.92521168 | −9.33831191 | 0.0532149 |

| 588017702410846353 | 219.9175712 | 9.34391573 | 0.0516048 | |

| (44) | 587727177930113154 | 40.58369451 | −9.32630004 | 0.155765 |

| 588017702411108409 | 220.5908395 | 9.3201034 | 0.1517 | |

| (45) | 587730816826212465 | 339.7809475 | −9.28473191 | 0.0631319 |

| 587734863222669402 | 159.7726217 | 9.27776767 | 0.0686803 | |

| (46) | 587727230524260481 | 29.54831241 | −9.28065885 | 0.0912357 |

| 587736542552653969 | 209.5405473 | 9.27495593 | 0.0982227 | |

| (47) | 587730816287113330 | 334.562248 | −9.27926377 | 0.097067 |

| 587732772117217405 | 154.5603312 | 9.27525384 | 0.1006 | |

| (48) | 587726877808787613 | 333.5596377 | −9.10873 | 0.125766 |

| 587732772116758696 | 153.5547995 | 9.10677581 | 0.117325 | |

| (49) | 587727227308802155 | 18.62293278 | −9.09116739 | 0.0828624 |

| 587736541474193627 | 198.6259619 | 9.08656038 | 0.0928012 | |

| (50) | 587727231058837640 | 24.24960403 | −9.07220804 | 0.116431 |

| 587736542013489445 | 204.258942 | 9.07093891 | 0.122971 | |

| (51) | 587727231059034221 | 24.70990827 | −9.050773 | 0.0766974 |

| 587736542013685982 | 204.707667 | 9.05688215 | 0.0775408 | |

| (52) | 587724240688382034 | 38.55751214 | −8.98833628 | 0.111355 |

| 588017992306458874 | 218.563633 | 8.99273253 | 0.116682 | |

| (53) | 587727180595134577 | 355.7997977 | −8.987712 | 0.0753556 |

| 587734891677548628 | 175.8078012 | 8.98622382 | 0.0829316 | |

| (54) | 587727180594479192 | 354.2791585 | −8.98725868 | 0.0806326 |

| 587732770515124373 | 174.277534 | 8.99625689 | 0.0760123 | |

| (55) | 587726878886723739 | 343.2696496 | −8.98547579 | 0.170464 |

| 587732771047211211 | 163.2757834 | 8.99239073 | 0.166468 | |

| (56) | 587726879426150556 | 349.2821756 | −8.9139055 | 0.0837956 |

| 587732770512961595 | 169.2765643 | 8.90951915 | 0.0850834 | |

| (57) | 587726877269229794 | 327.3372251 | −8.88489879 | 0.0911886 |

| 587732772650942640 | 147.3341982 | 8.8846179 | 0.0977782 | |

| (58) | 587727227843510349 | 13.58226852 | −8.82669194 | 0.0775205 |

| 587732769986576485 | 193.5776433 | 8.82324646 | 0.0802786 | |

| (59) | 587727227841544334 | 9.17385956 | −8.81343367 | 0.161788 |

| 587732769984675893 | 189.1800829 | 8.81570619 | 0.165148 | |

| (60) | 587727227840823364 | 7.41474543 | −8.78739786 | 0.134174 |

| 587732769983889559 | 187.4173796 | 8.79260319 | 0.141713 | |

| (61) | 587726879424774256 | 346.0556579 | −8.74818209 | 0.097193 |

| 587732770511519918 | 166.0566685 | 8.740358 | 0.0875037 | |

| (62) | 587727180071501902 | 26.40085465 | −8.73107212 | 0.121164 |

| 588017990690603214 | 206.3924788 | 8.73386769 | 0.120342 | |

| (63) | 587726877268902222 | 326.6199672 | −8.72026028 | 0.135262 |

| 587734863753838722 | 146.6245995 | 8.71266702 | 0.134986 | |

| (64) | 587727227842986122 | 12.49783122 | −8.70198555 | 0.0739487 |

| 587732769986117760 | 192.5043783 | 8.69610353 | 0.0837418 | |

| (65) | 587726878345265364 | 332.6514376 | −8.66253229 | 0.103393 |

| 587732771579494537 | 152.6458706 | 8.66485751 | 0.0973786 | |

| (66) | 587730817361182802 | 335.363148 | −8.64716609 | 0.0373209 |

| 587734862683832453 | 155.3597555 | 8.64438959 | 0.0450276 | |

| (67) | 587724240689102969 | 40.22878711 | −8.64369517 | 0.0380482 |

| 587736543094177958 | 220.2206679 | 8.64675197 | 0.0308106 | |

| (68) | 587726877268312182 | 325.2592388 | −8.63777296 | 0.0863781 |

| 587732772650025128 | 145.2509033 | 8.63971077 | 0.0846345 | |

| (69) | 587727227843510316 | 13.66287605 | −8.63255357 | 0.0778701 |

| 588017730839642176 | 193.6626503 | 8.63958689 | 0.0827405 | |

| (70) | 587730818439512260 | 346.092724 | −8.50560084 | 0.172473 |

| 587734891673354322 | 166.094645 | 8.51369065 | 0.175036 | |

| (71) | 587727231597478004 | 28.3056497 | −8.42097287 | 0.0471675 |

| 587736541478387896 | 208.3127137 | 8.41497984 | 0.0450439 | |

| (72) | 587730818439053410 | 344.9876466 | −8.39745108 | 0.0779055 |

| 587734891672895587 | 164.9894861 | 8.39564562 | 0.073904 | |

| (73) | 587727212272943399 | 320.8338911 | −8.39485218 | 0.117779 |

| 587734948049912071 | 140.8422313 | 8.39661384 | 0.11207 | |

| (74) | 587727212273271140 | 321.5992953 | −8.37544229 | 0.158414 |

| 587734948050239774 | 141.6072698 | 8.3832973 | 0.152886 | |

| (75) | 587724240155705507 | 48.22814118 | −8.33581316 | 0.0735155 |

| 587736477058990249 | 228.2378153 | 8.33940235 | 0.0804487 | |

| (76) | 587727177934307453 | 50.24970865 | −8.29951375 | 0.0330458 |

| 588017702952173868 | 230.2488442 | 8.308433 | 0.0393475 | |

| (77) | 587726878343823623 | 329.4183427 | −8.27673436 | 0.148898 |

| 587732771578052774 | 149.4134499 | 8.27527956 | 0.15852 | |

| (78) | 587726877804855542 | 324.4594709 | −8.21209911 | 0.0871732 |

| 587732772112826583 | 144.4574674 | 8.20228244 | 0.0867666 | |

| (79) | 587727178469802145 | 46.9844432 | −8.18224969 | 0.0744629 |

| 588017992310128884 | 226.9932375 | 8.19029998 | 0.0765801 | |

| (80) | 587726878882332761 | 333.2058322 | −8.14083953 | 0.0837303 |

| 587732771042820325 | 153.2151481 | 8.1369431 | 0.0842566 | |

| (81) | 587727232134873177 | 29.37707349 | −7.94639568 | 0.10361 |

| 587736526444560520 | 209.3793586 | 7.94487803 | 0.103126 | |

| (82) | 587727232134742064 | 29.16828094 | −7.91303927 | 0.0989567 |

| 587736526444429478 | 209.1635351 | 7.91749915 | 0.103407 | |

| (83) | 587730817895629069 | 329.9017868 | −7.78737555 | 0.0856975 |

| 587732771041378462 | 149.8929509 | 7.78668911 | 0.0914809 | |

| (84) | 587726878341726580 | 324.6422074 | −7.75110002 | 0.0880603 |

| 587732771576021174 | 144.6379017 | 7.74239199 | 0.0931418 | |

| (85) | 587730818435317875 | 336.3522559 | −7.7508616 | 0.109669 |

| 587732769970454629 | 156.3434173 | 7.74177121 | 0.103487 | |

| (86) | 587726877264839112 | 317.3101898 | −7.73854853 | 0.0732018 |

| 587734948048404618 | 137.3147516 | 7.72945807 | 0.0821823 | |

| (87) | 587730818433155251 | 331.3679425 | −7.45623643 | 0.0592957 |

| 587734861608321127 | 151.3713518 | 7.46400606 | 0.0621482 | |

| (88) | 587724240694542491 | 52.76892686 | −7.35645715 | 0.138503 |

| 587736543099617547 | 232.7601059 | 7.34722426 | 0.129012 | |

| (89) | 587724241765007480 | 45.13170845 | −7.34640725 | 0.161412 |

| 587736542022598934 | 225.1285679 | 7.34491587 | 0.154524 | |

| (90) | 587727179008311337 | 50.7121024 | −7.32739104 | 0.0845821 |

| 588017991774896410 | 230.7190341 | 7.3349747 | 0.0783759 | |

| (91) | 587724240694673500 | 52.96494777 | −7.25533989 | 0.133988 |

| 587736543099683339 | 232.959273 | 7.24727706 | 0.128557 | |

| (92) | 587730818432041321 | 328.9376199 | −7.06320875 | 0.0592138 |

| 587732579378724931 | 148.9383586 | 7.06251179 | 0.0602015 | |

| (93) | 587726879954370763 | 329.3517007 | −7.04637715 | 0.0859399 |

| 587732579378921673 | 149.3440319 | 7.03988761 | 0.0784532 | |

| (94) | 587724242302533699 | 46.63534829 | −6.83786511 | 0.028473 |

| 587736541486383232 | 226.6284051 | 6.83905419 | 0.0376736 | |

| (95) | 587726879953322317 | 327.0174505 | −6.78848336 | 0.0898924 |

| 587732579377873009 | 147.0128383 | 6.79790707 | 0.0932444 | |

| (96) | 587727180081660026 | 49.76721128 | −6.65462997 | 0.171731 |

| 588017990700826690 | 229.7751332 | 6.65265276 | 0.17779 | |

| (97) | 587726879952732589 | 325.6644648 | −6.53424217 | 0.0882166 |

| 587732703396430084 | 145.6718053 | 6.52802864 | 0.0933982 | |

| (98) | 587727179011195092 | 57.28409909 | −6.5146857 | 0.0656059 |

| 588017991777780111 | 237.2916735 | 6.51711338 | 0.0727241 | |

| (99) | 587726879413371300 | 319.8134098 | −6.4153901 | 0.0633028 |

| 587732770500116746 | 139.8142344 | 6.40937891 | 0.0725347 | |

| (100) | 587726879950045526 | 319.5050187 | −5.89992385 | 0.0887226 |

| 587732578837725451 | 139.5035274 | 5.89314752 | 0.090063 | |

| (101) | 587724241234690202 | 60.1469532 | −5.82246607 | 0.128101 |

| 587736542566023562 | 240.1442599 | 5.81544137 | 0.120623 | |

| (102) | 587724241771102391 | 59.12398332 | −5.6749918 | 0.0597927 |

| 587736542028693952 | 239.1163388 | 5.66555938 | 0.0621059 | |

| (103) | 587724241770709041 | 58.1813494 | −5.66402869 | 0.124912 |

| 587736542028300451 | 238.1814968 | 5.66896383 | 0.132543 | |

| (104) | 587724242307448950 | 57.81327563 | −5.44193649 | 0.12508 |

| 587736541491298661 | 237.8139452 | 5.4320315 | 0.117586 | |

| (105) | 587727180085919882 | 59.45274909 | −5.37776939 | 0.112835 |

| 588017990705086634 | 239.459686 | 5.3730717 | 0.114617 | |

| (106) | 587726879409635950 | 311.3361796 | −5.13025247 | 0.100322 |

| 587732703390204231 | 131.3358794 | 5.12942269 | 0.0944183 | |

| (107) | 587727214952710451 | 310.6951216 | −5.00957318 | 0.0533286 |

| 587732578833859013 | 130.7039891 | 5.01590373 | 0.0516006 | |

| (108) | 587726879408915112 | 309.7014626 | −5.00378611 | 0.0822278 |

| 587732703389483300 | 129.7102373 | 5.0038262 | 0.0759225 | |

| (109) | 587727180622528725 | 58.85069515 | −4.88213314 | 0.0739501 |

| 587730023336902902 | 238.8427352 | 4.88395362 | 0.0681825 | |

| (110) | 587724650869686415 | 184.6727131 | −1.25620133 | 0.0803352 |

| 587731187816595528 | 4.66679487 | 1.26085556 | 0.0876818 | |

| (111) | 587724650869424248 | 184.0892593 | −1.25371914 | 0.108284 |

| 587731187816333417 | 4.09325126 | 1.25789316 | 0.105123 | |

| (112) | 588015507671089581 | 28.14765501 | −1.22061106 | 0.174438 |

| 587726031187148932 | 208.1479272 | 1.22578036 | 0.174331 | |

| (113) | 587729971792052457 | 228.9119379 | −1.22029557 | 0.120609 |

| 587731514229588106 | 48.91797559 | 1.21584566 | 0.112363 | |

| (114) | 587748927626608776 | 172.1310313 | −1.21504223 | 0.113913 |

| 587731187811090545 | 352.1225299 | 1.21974134 | 0.119537 | |

| (115) | 587734303270764663 | 341.5351663 | −1.20503473 | 0.0583548 |

| 587726031166701712 | 161.5251899 | 1.20328815 | 0.0671257 | |

| (116) | 587722981747458159 | 196.8323221 | −1.10495117 | 0.0858605 |

| 587731514215563418 | 16.84068508 | 1.10383695 | 0.0941228 | |

| (117) | 588015507676987550 | 41.62918519 | −1.09799691 | 0.0740636 |

| 587726014013440008 | 221.6264322 | 1.10413737 | 0.0735006 | |

| (118) | 587722981750931657 | 204.8306575 | −1.06369837 | 0.0707877 |

| 587731514219036795 | 24.83154818 | 1.06710408 | 0.078975 | |

| (119) | 587731511532454043 | 19.75110345 | −0.99674932 | 0.044761 |

| 587722984433057983 | 199.7536973 | 0.99668931 | 0.0541101 | |

| (120) | 587731185125359869 | 349.0427567 | −0.98745757 | 0.091398 |

| 587748930309587102 | 169.0524929 | 0.9931595 | 0.0962012 | |

| (121) | 587731185116315784 | 328.3852669 | −0.92491413 | 0.0954053 |

| 587728950120612023 | 148.3899618 | 0.92361081 | 0.0948823 | |

| (122) | 588848898860056883 | 228.2742186 | −0.90832571 | 0.129659 |

| 588015510364225797 | 48.27957041 | 0.91491284 | 0.131263 | |

| (123) | 587731185119723924 | 336.1672691 | −0.89711779 | 0.0991819 |

| 587728950124019803 | 156.1666319 | 0.89373435 | 0.0938088 | |

| (124) | 588848898847539378 | 199.7024399 | −0.8926827 | 0.0818081 |

| 588015510351708322 | 19.70776073 | 0.89908792 | 0.0800928 | |

| (125) | 588848898830172339 | 159.9730114 | −0.85567902 | 0.0908891 |

| 587734305954463933 | 339.9668426 | 0.86319413 | 0.0873762 | |

| (126) | 588848898843279472 | 189.8915184 | −0.85366277 | 0.0242445 |

| 588015510347448339 | 9.89514685 | 0.85996826 | 0.0146933 | |

| (127) | 587728947975291011 | 153.3264231 | −0.8327221 | 0.0490744 |

| 587731187265962312 | 333.3213035 | 0.83853245 | 0.0571919 | |

| (128) | 587729778526781840 | 234.5183544 | −0.8262151 | 0.144058 |

| 587731513695142080 | 54.52663634 | 0.82450886 | 0.139076 | |

| (129) | 587722982293176752 | 217.0007899 | −0.82291535 | 0.399234 |

| 587731513687474437 | 36.99722415 | 0.81755209 | 0.397598 | |

| (130) | 587734303804031262 | 333.3022362 | −0.80519986 | 0.129767 |

| 588848900974706861 | 153.3035057 | 0.80991503 | 0.120938 | |

| (131) | 587722982300123441 | 232.9101284 | −0.79167934 | 0.0766653 |

| 587731513694421196 | 52.90549275 | 0.79102086 | 0.0856506 | |

| (132) | 587722982285508856 | 199.6286217 | −0.78745739 | 0.0882834 |

| 587731513679872138 | 19.62375817 | 0.78798276 | 0.0898079 | |

| (133) | 587734303805866210 | 337.4814454 | −0.7517174 | 0.0903008 |

| 588848900976541910 | 157.4856125 | 0.75898364 | 0.099725 | |

| (134) | 588015508192624827 | 353.1832021 | −0.74826734 | 0.0574768 |

| 588848900983423150 | 173.1767412 | 0.75630883 | 0.0674753 | |

| (135) | 588015508203241620 | 17.35657948 | −0.73451621 | 0.103116 |

| 588848900994039948 | 197.3614164 | 0.72866873 | 0.0944896 | |

| (136) | 588015508216873237 | 48.61535843 | −0.71640599 | 0.0873679 |

| 588848901007671746 | 228.6074205 | 0.70948451 | 0.0915592 | |

| (137) | 588015508218904634 | 53.23858074 | −0.70414471 | 0.0331694 |

| 588848901009703095 | 233.2419617 | 0.71068808 | 0.0378785 | |

| (138) | 587722982280593611 | 188.3839313 | −0.69206406 | 0.0716765 |

| 587731187281297523 | 8.38761185 | 0.69265965 | 0.0666569 | |

| (139) | 587748928166887621 | 179.9836371 | −0.68306759 | 0.0800753 |

| 587731187277627630 | 359.9849222 | 0.67510242 | 0.0848031 | |

| 140) | 588015508212285576 | 38.07654238 | −0.66091986 | 0.152935 |

| 588848901003084008 | 218.0833898 | 0.65782354 | 0.148348 | |

| (141) | 587722982275154175 | 175.8949958 | −0.63154972 | 0.0777659 |

| 587731187275858096 | 355.9025156 | 0.63455671 | 0.0830219 | |

| (142) | 588848899399090470 | 233.1265588 | −0.60318561 | 0.0834699 |

| 588015509829517446 | 53.12424142 | 0.60899384 | 0.0888991 | |

| (143) | 588848899394830608 | 223.4164629 | −0.59793901 | 0.0757585 |

| 588015509825257582 | 43.4242485 | 0.59779667 | 0.0674929 | |

| (144) | 587731172768809842 | 312.9796387 | −0.5957954 | 0.0542642 |

| 587725075526189422 | 132.9735106 | 0.58860398 | 0.0512173 | |

| (145) | 588848899367698514 | 161.4291165 | −0.59321324 | 0.0850623 |

| 587734305418182948 | 341.4353393 | 0.59869345 | 0.0853401 | |

| (146) | 588848899377791164 | 184.5422801 | −0.54941729 | 0.0806642 |

| 588015509808218204 | 4.53334222 | 0.54320436 | 0.0883403 | |

| (147) | 588848899381395678 | 192.8322052 | −0.54359022 | 0.0823546 |

| 588015509811822661 | 12.82661496 | 0.54938195 | 0.0838967 | |

| (148) | 587731512070570074 | 22.52506877 | −0.53886851 | 0.0752843 |

| 587722983897432095 | 202.5292389 | 0.53144561 | 0.0753058 | |

| (149) | 588848899365142729 | 155.7201062 | −0.52903144 | 0.161499 |

| 587734305415692542 | 335.7266832 | 0.52749615 | 0.161789 | |

| (150) | 587731185656922427 | 336.925539 | −0.52188082 | 0.142554 |

| 587728949587476580 | 156.9318551 | 0.51420834 | 0.147027 | |

| (151) | 587731512085708963 | 57.24298571 | −0.52109991 | 0.0398141 |

| 587722983912636747 | 237.2401798 | 0.51948336 | 0.0326624 | |

| (152) | 588848899365208074 | 155.7345006 | −0.52048483 | 0.152984 |

| 587734305415692542 | 335.7266832 | 0.52749615 | 0.161789 | |

| (153) | 587731512075026623 | 32.7941736 | −0.51697122 | 0.104186 |

| 587722983901888776 | 212.7874643 | 0.51757655 | 0.10494 | |

| (154) | 587731512070570080 | 22.53092957 | −0.51301286 | 0.0754378 |

| 587722983897432249 | 202.5290072 | 0.50960505 | 0.0842453 | |

| (155) | 588848899367567503 | 161.1736846 | −0.50354558 | 0.116059 |

| 587734305418117322 | 341.1713409 | 0.49887529 | 0.10686 | |

| (156) | 587731185663738041 | 352.414892 | −0.49559734 | 0.0610491 |

| 587748929774223562 | 172.4212536 | 0.49196292 | 0.0617746 | |

| (157) | 587731185657315605 | 337.8171047 | −0.46714883 | 0.089706 |

| 587728949587869853 | 157.8165583 | 0.46875388 | 0.0972739 | |

| (158) | 588848899365011498 | 155.3428317 | −0.46621861 | 0.0616145 |

| 587734305415561419 | 335.3404111 | 0.46782104 | 0.0585452 | |

| (159) | 587731185654825160 | 332.0329757 | −0.45305431 | 0.0966575 |

| 587728949585314077 | 152.0316255 | 0.44515599 | 0.096859 | |

| (160) | 588848899369599194 | 165.777933 | −0.43232161 | 0.408335 |

| 588015509800026315 | 345.7681431 | 0.42889055 | 0.406645 | |

| (161) | 588848899392012585 | 217.0954067 | −0.42921954 | 0.13692 |

| 588015509822505078 | 37.10056005 | 0.42263247 | 0.13819 | |

| (162) | 587748928964460711 | 162.3131562 | −0.4126741 | 0.0631013 |

| 587731186733023422 | 342.3072456 | 0.40960475 | 0.0687452 | |

| (163) | 588015508738474102 | 13.66692127 | −0.40711197 | 0.0431046 |

| 588848900455530621 | 193.6587778 | 0.40977996 | 0.048432 | |

| (164) | 588015508744241268 | 26.76827379 | −0.39658262 | 0.0921257 |

| 588848900461232473 | 206.7714106 | 0.39999281 | 0.0904585 | |

| (165) | 587730846891377212 | 322.2164035 | −0.36530606 | 0.0524633 |

| 588848900432986349 | 142.2201617 | 0.3629534 | 0.0564073 | |

| (166) | 587722982818971844 | 191.8125016 | −0.35898776 | 0.126037 |

| 587731186745933956 | 11.82036541 | 0.35818073 | 0.117239 | |

| (167) | 588015508741030001 | 19.45674285 | −0.34082464 | 0.0468492 |

| 588848900458086553 | 199.4599698 | 0.34994819 | 0.048473 | |

| (168) | 588015508727529597 | 348.5866992 | −0.33249466 | 0.0806627 |

| 588848900444520624 | 168.5870372 | 0.32365469 | 0.0784033 | |

| (169) | 588015508727136416 | 347.7652686 | −0.32576489 | 0.0983488 |

| 588848900444192846 | 167.7733221 | 0.32533721 | 0.0968191 | |

| (170) | 587730846890132061 | 319.3488484 | −0.31274778 | 0.0580555 |

| 588848900431741191 | 139.3414636 | 0.32191469 | 0.0540347 | |

| (171) | 587734304341426385 | 334.4289933 | −0.29072537 | 0.0946837 |

| 588848900438360204 | 154.434898 | 0.2951535 | 0.0948182 | |

| (172) | 587734304340640020 | 332.7387428 | −0.26301595 | 0.180004 |

| 588848900437573950 | 152.7359484 | 0.25633147 | 0.186205 | |

| (173) | 587722982822772953 | 200.5231175 | −0.25712776 | 0.0755962 |

| 587731513143394377 | 20.52539083 | 0.26106339 | 0.0739661 | |

| (174) | 587730846892097872 | 323.7534775 | −0.25580372 | 0.23578 |

| 588848900433641580 | 143.7508871 | 0.25087206 | 0.230907 | |

| (175) | 587722982818578564 | 190.8538024 | −0.25574711 | 0.108047 |

| 587731186745540781 | 10.85230943 | 0.25272055 | 0.108846 | |

| (176) | 587728948512882891 | 155.0284918 | −0.24893939 | 0.0946879 |

| 587731186729877696 | 335.0272875 | 0.25118887 | 0.0976836 | |

| (177) | 587722982829588620 | 215.9538986 | −0.24834938 | 0.0845643 |

| 587731513150144670 | 35.96309274 | 0.24429916 | 0.0878976 | |

| (178) | 587728948515438760 | 160.8665986 | −0.24408333 | 0.0612075 |

| 587731186732433592 | 340.8655553 | 0.23643433 | 0.0602342 | |

| (179) | 587728948515438760 | 160.8665986 | −0.24408333 | 0.0612075 |

| 587731186732433605 | 340.8750138 | 0.24261057 | 0.0586656 | |

| (180) | 587722982817202308 | 187.6635646 | −0.21513005 | 0.112303 |

| 587731186744164449 | 7.6553343 | 0.21555044 | 0.114242 | |

| (181) | 587731512609996966 | 28.42414238 | −0.20766632 | 0.116707 |

| 587722983363117368 | 208.4229163 | 0.20947298 | 0.116208 | |

| (182) | 587731512620351626 | 52.0486704 | −0.18938222 | 0.0851471 |

| 587722983373472062 | 232.0581374 | 0.18368629 | 0.0798633 | |

| (183) | 588848899901030743 | 153.4421478 | −0.13358412 | 0.096212 |

| 587734304877838573 | 333.4461883 | 0.14101877 | 0.0959779 | |

| (184) | 588848899931963795 | 224.1292204 | −0.10150706 | 0.37695 |

| 588015509288648969 | 44.12854088 | 0.10090797 | 0.37109 | |

| (185) | 587731512620613919 | 52.66581732 | −0.08391774 | 0.0747399 |

| 587722983373733982 | 232.6567434 | 0.09144794 | 0.0712474 | |

| (186) | 587731512616550555 | 43.4068315 | −0.02922721 | 0.0437379 |

| 587722983369670840 | 223.4084883 | 0.02099328 | 0.0447694 | |

| (187) | 587731186188353997 | 324.4826276 | −0.02063334 | 0.0912575 |

| 587725074994364633 | 144.4802056 | 0.02165878 | 0.0908592 |

| Id SDSS DR7 | Ra | Dec | z | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | 587727227839578254 | 4.62339359 | −8.82776469 | 0.104797 |

| 587732769982709974 | 184.6230609 | 8.826889 | 0.481948 | |

| (2) | 587726877268312182 | 325.2592388 | −8.63777296 | 0.0863781 |

| 587732772650025129 | 145.2584188 | 8.63747987 | 0.182619 | |

| (3) | 587727227845804151 | 19.00360312 | −8.53841652 | 0.125065 |

| 587736540937519274 | 199.003274 | 8.53767648 | 0.0523744 | |

| (4) | 587726879422152915 | 340.0250784 | −8.32576871 | 0.211179 |

| 587732770508898457 | 160.0243395 | 8.32579967 | 0.46663 | |

| (5) | 587727212272943498 | 320.9004948 | −8.31734032 | 0.118795 |

| 587734948049977496 | 140.900737 | 8.31661374 | 0.132243 | |

| (6) | 587724240691855395 | 46.59481629 | −8.02287019 | 0.119974 |

| 587736543096930620 | 226.5946368 | 8.0234898 | 0.141641 | |

| (7) | 587726879416648036 | 327.4332687 | −7.24482558 | 0.120794 |

| 587732770503458957 | 147.4334035 | 7.24510724 | 0.172101 | |

| (8) | 587730818432041321 | 328.9376199 | −7.06320875 | 0.0592138 |

| 587732579378724931 | 148.9383586 | 7.06251179 | 0.0602015 | |

| (9) | 587726879951618320 | 323.0326676 | −6.24542716 | 0.0835999 |

| 587732703395315898 | 143.0324689 | 6.2463979 | 0.152482 | |

| (10) | 587726879409635950 | 311.3361796 | −5.13025247 | 0.100322 |

| 587732703390204231 | 131.3358794 | 5.12942269 | 0.0944183 | |

| (11) | 587724242308432093 | 60.09682211 | −5.0670592 | 0.139483 |

| 587736541492281504 | 240.0961397 | 5.06798605 | 0.161674 | |

| (12) | 587722981749620931 | 201.8110903 | −1.15290891 | 0.0672574 |

| 587731514217726115 | 21.81094788 | 1.15332655 | 0.0825304 | |

| (13) | 588848898840002840 | 182.4290969 | −0.99010277 | 0.101162 |

| 588015510344171606 | 2.42945951 | 0.99083329 | 0.0595599 | |

| (14) | 587731511542349980 | 42.40717742 | −0.84245813 | 0.023485 |

| 587722984443019391 | 222.4075711 | 0.84279922 | 0.211561 | |

| (15) | 588848899373138039 | 173.8651882 | −0.55499635 | 0.105208 |

| 588015509803565082 | 353.8651982 | 0.55470851 | 0.241575 | |

| (16) | 588015508736114824 | 8.29352396 | −0.35022869 | 0.0803753 |

| 588848900453171355 | 188.2937459 | 0.35119113 | 0.091289 | |

| (17) | 587722982819365056 | 192.6996089 | −0.24023107 | 0.082066 |

| 587731186746327197 | 12.69923244 | 0.23965712 | 0.243192 | |

| (18) | 588848899913482481 | 181.8731715 | −0.20286898 | 0.086595 |

| 588015509270167718 | 1.87315452 | 0.20227552 | 0.139049 | |

| (19) | 587731186189599168 | 327.3151749 | −0.17472973 | 0.475598 |

| 587725074995609777 | 147.314463 | 0.17484814 | 0.0847248 | |

| (20) | 587731512608817253 | 25.67986817 | −0.10862577 | 0.114301 |

| 587722983361937622 | 205.6799242 | 0.10944099 | 0.0763704 | |

| (21) | 588848899931963795 | 224.1292204 | −0.10150706 | 0.37695 |

| 588015509288648969 | 44.12854088 | 0.10090797 | 0.37109 | |

| (22) | 588848899903258801 | 158.5313323 | −0.04817315 | 0.0649146 |

| 587734304880066822 | 338.5305229 | 0.04819563 | 0.212747 |

| Id SDSS DR7 | Ra | Dec | z | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | 587726877268312182 | 325.2592388 | −8.63777296 | 0.0863781 |

| 587732772650025129 | 145.2584188 | 8.63747987 | 0.182619 | |

| (2) | 587727227845804151 | 19.00360312 | −8.53841652 | 0.125065 |

| 587736540937519274 | 199.003274 | 8.53767648 | 0.0523744 | |

| (3) | 587726879422152915 | 340.0250784 | −8.32576871 | 0.211179 |

| 587732770508898457 | 160.0243395 | 8.32579967 | 0.46663 | |

| (4) | 587727212272943498 | 320.9004948 | −8.31734032 | 0.118795 |

| 587734948049977496 | 140.900737 | 8.31661374 | 0.132243 | |

| (5) | 587724240691855395 | 46.59481629 | −8.02287019 | 0.119974 |

| 587736543096930620 | 226.5946368 | 8.0234898 | 0.141641 | |

| (6) | 587726879416648036 | 327.4332687 | −7.24482558 | 0.120794 |

| 587732770503458957 | 147.4334035 | 7.24510724 | 0.172101 | |

| (7) | 587730818432041321 | 328.9376199 | −7.06320875 | 0.0592138 |

| 587732579378724931 | 148.9383586 | 7.06251179 | 0.0602015 | |

| (8) | 587726879951618320 | 323.0326676 | −6.24542716 | 0.0835999 |

| 587732703395315898 | 143.0324689 | 6.2463979 | 0.152482 | |

| (9) | 587726879409635950 | 311.3361796 | −5.13025247 | 0.100322 |

| 587732703390204231 | 131.3358794 | 5.12942269 | 0.0944183 | |

| (10) | 587724242308432093 | 60.09682211 | −5.0670592 | 0.139483 |

| 587736541492281504 | 240.0961397 | 5.06798605 | 0.161674 | |

| (11) | 587722981749620931 | 201.8110903 | −1.15290891 | 0.0672574 |

| 587731514217726115 | 21.81094788 | 1.15332655 | 0.0825304 | |

| (12) | 588848898840002840 | 182.4290969 | −0.99010277 | 0.101162 |

| 588015510344171606 | 2.42945951 | 0.99083329 | 0.0595599 | |

| (13) | 588848899373138039 | 173.8651882 | −0.55499635 | 0.105208 |

| 588015509803565082 | 353.8651982 | 0.55470851 | 0.241575 | |

| (14) | 588015508736114824 | 8.29352396 | −0.35022869 | 0.0803753 |

| 588848900453171355 | 188.2937459 | 0.35119113 | 0.091289 | |

| (15) | 587722982819365056 | 192.6996089 | −0.24023107 | 0.082066 |

| 587731186746327197 | 12.69923244 | 0.23965712 | 0.243192 | |

| (16) | 588848899913482481 | 181.8731715 | −0.20286898 | 0.086595 |

| 588015509270167718 | 1.87315452 | 0.20227552 | 0.139049 | |

| (17) | 587731512608817253 | 25.67986817 | −0.10862577 | 0.114301 |

| 587722983361937622 | 205.6799242 | 0.10944099 | 0.0763704 | |

| (18) | 588848899931963795 | 224.1292204 | −0.10150706 | 0.37695 |

| 588015509288648969 | 44.12854088 | 0.10090797 | 0.37109 |

Appendix B

| Id SDSS DR8 | Ra | Dec | Ell | Sp | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | 1237678888521237047 | 26.56961575 | −3.036690882 | 0.009671 | 0.990329 |

| 1237674469000413487 | 206.569743 | 3.036761704 | 0.147295 | 0.852705 | |

| (2) | 1237655693017940456 | 231.1268834 | −1.237362786 | 0.153929 | 0.846071 |

| 1237646588233974200 | 51.12707011 | 1.237392067 | 0.471205 | 0.528795 | |

| (3) | 1237655693017940456 | 231.1268834 | −1.237362786 | 0.153929 | 0.846071 |

| 1237657815275471153 | 51.12706887 | 1.237400496 | 0.52382 | 0.47618 | |

| (4) | 1237655693017940456 | 231.1268834 | −1.237362786 | 0.153929 | 0.846071 |

| 1237653000613921219 | 51.12707746 | 1.237402214 | 0.486234 | 0.513766 | |

| (5) | 1237655693017940456 | 231.1268834 | −1.237362786 | 0.153929 | 0.846071 |

| 1237659915511726413 | 51.12707585 | 1.237404045 | 0.484072 | 0.515928 | |

| (6) | 1237655693017940456 | 231.1268834 | −1.237362786 | 0.153929 | 0.846071 |

| 1237666516881834000 | 51.12704369 | 1.237412566 | 0.545912 | 0.454088 | |

| (7) | 1237655693017940456 | 231.1268834 | −1.237362786 | 0.153929 | 0.846071 |

| 1237666662937788799 | 51.12706696 | 1.23741968 | 0.492949 | 0.507051 | |

| (8) | 1237655693017940456 | 231.1268834 | −1.237362786 | 0.153929 | 0.846071 |

| 1237663330011251042 | 51.127083 | 1.237427134 | 0.502022 | 0.497978 | |

| (9) | 1237655693017940456 | 231.1268834 | −1.237362786 | 0.153929 | 0.846071 |

| 1237666409538519489 | 51.12708146 | 1.237445228 | 0.461594 | 0.538406 | |

| (10) | 1237655693017940456 | 231.1268834 | −1.237362786 | 0.153929 | 0.846071 |

| 1237666340814716950 | 51.12708141 | 1.237451208 | 0.435734 | 0.564266 | |

| (11) | 1237655693017940456 | 231.1268834 | −1.237362786 | 0.153929 | 0.846071 |

| 1237657587639386438 | 51.12708243 | 1.237457695 | 0.432267 | 0.567733 | |

| (12) | 1237655693017940456 | 231.1268834 | −1.237362786 | 0.153929 | 0.846071 |

| 1237657587639321096 | 51.12707884 | 1.237457919 | 0.457914 | 0.542086 | |

| (13) | 1237646748740026642 | 62.17470211 | −1.016792147 | 0.095611 | 0.904389 |

| 1237648705676575427 | 242.1748881 | 1.016716451 | 0.092952 | 0.907048 | |

| (14) | 1237646748740026642 | 62.17470211 | −1.016792147 | 0.095611 | 0.904389 |

| 1237648705676575428 | 242.1748845 | 1.01672036 | 0.078252 | 0.921748 | |

| (15) | 1237652997934416225 | 62.1747088 | −1.016787397 | 0.108173 | 0.891827 |

| 1237648705676575427 | 242.1748881 | 1.016716451 | 0.092952 | 0.907048 | |

| (16) | 1237652997934416225 | 62.1747088 | −1.016787397 | 0.108173 | 0.891827 |

| 1237648705676575428 | 242.1748845 | 1.01672036 | 0.078252 | 0.921748 | |

| (17) | 1237657761048166683 | 62.17471976 | −1.016786518 | 0.114383 | 0.885617 |

| 1237648705676575427 | 242.1748881 | 1.016716451 | 0.092952 | 0.907048 | |

| (18) | 1237657761048166683 | 62.17471976 | −1.016786518 | 0.114383 | 0.885617 |

| 1237648705676575428 | 242.1748845 | 1.01672036 | 0.078252 | 0.921748 | |

| (19) | 1237646748740026643 | 62.17475111 | −1.016781419 | 0.097682 | 0.902318 |

| 1237655551815123559 | 242.1749457 | 1.01671526 | 0.083047 | 0.916953 | |

| (20) | 1237646748740026643 | 62.17475111 | −1.016781419 | 0.097682 | 0.902318 |

| 1237648705676575427 | 242.1748881 | 1.016716451 | 0.092952 | 0.907048 | |

| (21) | 1237646748740026643 | 62.17475111 | −1.016781419 | 0.097682 | 0.902318 |

| 1237648705676575428 | 242.1748845 | 1.01672036 | 0.078252 | 0.921748 | |

| (22) | 1237649823937986797 | 62.17470476 | −1.016778157 | 0.109712 | 0.890288 |

| 1237648705676575427 | 242.1748881 | 1.016716451 | 0.092952 | 0.907048 | |

| (23) | 1237649823937986797 | 62.17470476 | −1.016778157 | 0.109712 | 0.890288 |

| 1237648705676575428 | 242.1748845 | 1.01672036 | 0.078252 | 0.921748 | |

| (24) | 1237646585554469394 | 62.17471262 | −1.016759557 | 0.087926 | 0.912074 |

| 1237648705676575427 | 242.1748881 | 1.016716451 | 0.092952 | 0.907048 | |

| (25) | 1237646585554469394 | 62.17471262 | −1.016759557 | 0.087926 | 0.912074 |

| 1237648705676575428 | 242.1748845 | 1.01672036 | 0.078252 | 0.921748 | |

| (26) | 1237666497028096411 | 62.17470133 | −1.016724343 | 0.06974 | 0.93026 |

| 1237648705676575427 | 242.1748881 | 1.016716451 | 0.092952 | 0.907048 | |

| (27) | 1237666497028096411 | 62.17470133 | −1.016724343 | 0.06974 | 0.93026 |

| 1237648705676575428 | 242.1748845 | 1.01672036 | 0.078252 | 0.921748 | |

| (28) | 1237666497028096412 | 62.17471675 | −1.016711222 | 0.07633 | 0.92367 |

| 1237648705676575427 | 242.1748881 | 1.016716451 | 0.092952 | 0.907048 | |

| (29) | 1237666497028096412 | 62.17471675 | −1.016711222 | 0.07633 | 0.92367 |

| 1237648705676575428 | 242.1748845 | 1.01672036 | 0.078252 | 0.921748 | |

| (30) | 1237655177615638991 | 128.668235 | −0.926547264 | 0.883225 | 0.116775 |

| 1237649942587703356 | 308.6681411 | 0.926418898 | 0.861631 | 0.138369 | |

| (31) | 1237648720134537650 | 128.6682518 | −0.926538368 | 0.902699 | 0.097301 |

| 1237649942587703356 | 308.6681411 | 0.926418898 | 0.861631 | 0.138369 | |

| (32) | 1237648720166060380 | 200.6434022 | −0.866110951 | 0.989174 | 0.010826 |

| 1237663480353259732 | 20.64339386 | 0.86631035 | 0.958359 | 0.041641 |

| Id SDSS DR8 | Ra | Dec | Sp | Zphot | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | 1237650372102127690 | 201.8110906 | −1.1529332 | 0.80 | 0.061 |

| 1237666662924943502 | 21.81093325 | 1.15332143 | 0.56 | 0.070 | |

| (2) | 1237650372102127690 | 201.8110906 | −1.1529332 | 0.80 | 0.061 |

| 1237660237652623499 | 21.81093366 | 1.15333317 | 0.64 | 0.071 | |

| (3) | 1237650372102127690 | 201.8110906 | −1.1529332 | 0.80 | 0.061 |

| 1237663205460607081 | 21.81092528 | 1.15333562 | 0.61 | 0.070 | |

| (4) | 1237650372102127690 | 201.8110906 | −1.1529332 | 0.80 | 0.061 |

| 1237660010021060695 | 21.8109353 | 1.15333828 | 0.58 | 0.069 | |

| (5) | 1237650372102127690 | 201.8110906 | −1.1529332 | 0.80 | 0.061 |

| 1237660010021060693 | 21.8109426 | 1.1533383 | 0.58 | 0.069 | |

| (6) | 1237650372102127690 | 201.8110906 | −1.1529332 | 0.80 | 0.061 |

| 1237646588221128874 | 21.81095251 | 1.15334338 | 0.54 | 0.071 | |

| (7) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.8110888 | −1.1529142 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237656909048971424 | 21.81094041 | 1.1533158 | 0.59 | 0.072 | |

| (8) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.8110888 | −1.1529142 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237666662924943502 | 21.81093325 | 1.15332143 | 0.56 | 0.070 | |

| (9) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.8110888 | −1.1529142 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237657235442630860 | 21.8109474 | 1.15332466 | 0.57 | 0.078 | |

| (10) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.8110888 | −1.1529142 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237657815262625899 | 21.81092583 | 1.15333002 | 0.57 | 0.075 | |

| (11) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.8110888 | −1.1529142 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237646588221128876 | 21.81094599 | 1.15333221 | 0.67 | 0.074 | |

| (12) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.8110888 | −1.1529142 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237666340801871988 | 21.81093809 | 1.15333261 | 0.59 | 0.072 | |

| (13) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.8110888 | −1.1529142 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237660237652623499 | 21.81093366 | 1.15333317 | 0.64 | 0.071 | |

| (14) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.8110888 | −1.1529142 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237662969220497579 | 21.81093606 | 1.15333365 | 0.67 | 0.073 | |

| (15) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.8110888 | −1.1529142 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237663205460607081 | 21.81092528 | 1.15333562 | 0.61 | 0.070 | |

| (16) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.8110888 | −1.1529142 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237657106606063792 | 21.81092612 | 1.15333705 | 0.65 | 0.077 | |

| (17) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.8110888 | −1.1529142 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237659915498881211 | 21.81093881 | 1.15333749 | 0.64 | 0.076 | |

| (18) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.8110888 | −1.1529142 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237660010021060693 | 21.8109426 | 1.1533383 | 0.58 | 0.069 | |

| (19) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.8110888 | −1.1529142 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237663544779276481 | 21.8109381 | 1.15334331 | 0.59 | 0.074 | |

| (20) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.8110888 | −1.1529142 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237646588221128874 | 21.81095251 | 1.15334338 | 0.54 | 0.071 | |

| (21) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.8110888 | −1.1529142 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237657737950789725 | 21.81092483 | 1.15334534 | 0.64 | 0.073 | |

| (22) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.8110888 | −1.1529142 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237666409525739588 | 21.81091124 | 1.15334613 | 0.60 | 0.080 | |

| (23) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.8110888 | −1.1529142 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237656513889894587 | 21.81092948 | 1.15334793 | 0.59 | 0.072 | |

| (24) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.8110888 | −1.1529142 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237656513889894586 | 21.81093578 | 1.15334862 | 0.64 | 0.073 | |

| (25) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.8110888 | −1.1529142 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237657072230400220 | 21.81093259 | 1.15334873 | 0.61 | 0.076 | |

| (26) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.8110888 | −1.1529142 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237678617427378399 | 21.81092545 | 1.15335605 | 0.66 | 0.079 | |

| (27) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.8110888 | −1.1529142 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237678617427378397 | 21.81093158 | 1.15336241 | 0.59 | 0.076 | |

| (28) | 1237651279931506991 | 201.8110746 | −1.1529118 | 0.76 | 0.085 |

| 1237657235442630860 | 21.8109474 | 1.15332466 | 0.57 | 0.078 | |

| (29) | 1237651279931506991 | 201.8110746 | −1.1529118 | 0.76 | 0.085 |

| 1237657815262625899 | 21.81092583 | 1.15333002 | 0.57 | 0.075 | |

| (30) | 1237651279931506991 | 201.8110746 | −1.1529118 | 0.76 | 0.085 |

| 1237657106606063792 | 21.81092612 | 1.15333705 | 0.65 | 0.077 | |

| (31) | 1237651279931506991 | 201.8110746 | −1.1529118 | 0.76 | 0.085 |

| 1237659915498881211 | 21.81093881 | 1.15333749 | 0.64 | 0.076 | |

| (32) | 1237651279931506991 | 201.8110746 | −1.1529118 | 0.76 | 0.085 |

| 1237666409525739588 | 21.81091124 | 1.15334613 | 0.60 | 0.080 | |

| (33) | 1237651279931506991 | 201.8110746 | −1.1529118 | 0.76 | 0.085 |

| 1237657072230400220 | 21.81093259 | 1.15334873 | 0.61 | 0.076 | |

| (34) | 1237651279931506991 | 201.8110746 | −1.1529118 | 0.76 | 0.085 |

| 1237678617427378399 | 21.81092545 | 1.15335605 | 0.66 | 0.079 | |

| (35) | 1237651279931506991 | 201.8110746 | −1.1529118 | 0.76 | 0.085 |

| 1237678617427378397 | 21.81093158 | 1.15336241 | 0.59 | 0.076 | |

| (36) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.8110905 | −1.1529069 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237656909048971424 | 21.81094041 | 1.1533158 | 0.59 | 0.072 | |

| (37) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.8110905 | −1.1529069 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237666662924943502 | 21.81093325 | 1.15332143 | 0.56 | 0.070 | |

| (38) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.8110905 | −1.1529069 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237657235442630860 | 21.8109474 | 1.15332466 | 0.57 | 0.078 | |

| (39) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.8110905 | −1.1529069 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237657815262625899 | 21.81092583 | 1.15333002 | 0.57 | 0.075 | |

| (40) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.8110905 | −1.1529069 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237646588221128876 | 21.81094599 | 1.15333221 | 0.67 | 0.074 | |

| (41) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.8110905 | −1.1529069 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237666340801871988 | 21.81093809 | 1.15333261 | 0.59 | 0.072 | |

| (42) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.8110905 | −1.1529069 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237660237652623499 | 21.81093366 | 1.15333317 | 0.64 | 0.071 | |

| (43) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.8110905 | −1.1529069 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237662969220497579 | 21.81093606 | 1.15333365 | 0.67 | 0.073 | |

| (44) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.8110905 | −1.1529069 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237663205460607081 | 21.81092528 | 1.15333562 | 0.61 | 0.070 | |

| (45) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.8110905 | −1.1529069 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237657106606063792 | 21.81092612 | 1.15333705 | 0.65 | 0.077 | |

| (46) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.8110905 | −1.1529069 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237659915498881211 | 21.81093881 | 1.15333749 | 0.64 | 0.076 | |

| (47) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.8110905 | −1.1529069 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237660010021060695 | 21.8109353 | 1.15333828 | 0.58 | 0.069 | |

| (48) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.8110905 | −1.1529069 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237660010021060693 | 21.8109426 | 1.1533383 | 0.58 | 0.069 | |

| (49) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.8110905 | −1.1529069 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237663544779276481 | 21.8109381 | 1.15334331 | 0.59 | 0.074 | |

| (50) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.8110905 | −1.1529069 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237646588221128874 | 21.81095251 | 1.15334338 | 0.54 | 0.071 | |

| (51) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.8110905 | −1.1529069 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237657737950789725 | 21.81092483 | 1.15334534 | 0.64 | 0.073 | |

| (52) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.8110905 | −1.1529069 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237666409525739588 | 21.81091124 | 1.15334613 | 0.60 | 0.080 | |

| (53) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.8110905 | −1.1529069 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237656513889894587 | 21.81092948 | 1.15334793 | 0.59 | 0.072 | |

| (54) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.8110905 | −1.1529069 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237656513889894586 | 21.81093578 | 1.15334862 | 0.64 | 0.073 | |

| (55) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.8110905 | −1.1529069 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237657072230400220 | 21.81093259 | 1.15334873 | 0.61 | 0.076 | |

| (56) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.8110905 | −1.1529069 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237678617427378399 | 21.81092545 | 1.15335605 | 0.66 | 0.079 | |

| (57) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.8110905 | −1.1529069 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237678617427378397 | 21.81093158 | 1.15336241 | 0.59 | 0.076 | |

| (58) | 1237666406859014666 | 62.17467447 | −1.016796 | 0.90 | 0.081 |

| 1237655551815123559 | 242.1749457 | 1.01671526 | 0.92 | 0.088 | |

| (59) | 1237666406859014666 | 62.17467447 | −1.016796 | 0.90 | 0.081 |

| 1237648705676575427 | 242.1748881 | 1.01671645 | 0.91 | 0.084 | |

| (60) | 1237666406859014666 | 62.17467447 | −1.016796 | 0.90 | 0.081 |

| 1237648705676575428 | 242.1748845 | 1.01672036 | 0.92 | 0.076 | |

| (61) | 1237652997934416225 | 62.1747088 | −1.0167874 | 0.89 | 0.074 |

| 1237648705676575427 | 242.1748881 | 1.01671645 | 0.91 | 0.084 | |

| (62) | 1237652997934416225 | 62.1747088 | −1.0167874 | 0.89 | 0.074 |

| 1237648705676575428 | 242.1748845 | 1.01672036 | 0.92 | 0.076 | |

| (63) | 1237646748740026643 | 62.17475111 | −1.0167814 | 0.90 | 0.076 |

| 1237648705676575427 | 242.1748881 | 1.01671645 | 0.91 | 0.084 | |

| (64) | 1237646748740026643 | 62.17475111 | −1.0167814 | 0.90 | 0.076 |

| 1237648705676575428 | 242.1748845 | 1.01672036 | 0.92 | 0.076 | |

| (65) | 1237649823937986797 | 62.17470476 | −1.0167782 | 0.89 | 0.071 |

| 1237648705676575428 | 242.1748845 | 1.01672036 | 0.92 | 0.076 | |

| (66) | 1237646585554469394 | 62.17471262 | −1.0167596 | 0.91 | 0.083 |

| 1237655551815123559 | 242.1749457 | 1.01671526 | 0.92 | 0.088 | |

| (67) | 1237646585554469394 | 62.17471262 | −1.0167596 | 0.91 | 0.083 |

| 1237648705676575427 | 242.1748881 | 1.01671645 | 0.91 | 0.084 | |

| (68) | 1237646585554469394 | 62.17471262 | −1.0167596 | 0.91 | 0.083 |

| 1237648705676575428 | 242.1748845 | 1.01672036 | 0.92 | 0.076 | |

| (69) | 1237666497028096411 | 62.17470133 | −1.0167243 | 0.93 | 0.085 |

| 1237655551815123559 | 242.1749457 | 1.01671526 | 0.92 | 0.088 | |

| (70) | 1237666497028096411 | 62.17470133 | −1.0167243 | 0.93 | 0.085 |

| 1237648705676575427 | 242.1748881 | 1.01671645 | 0.91 | 0.084 | |

| (71) | 1237666497028096411 | 62.17470133 | −1.0167243 | 0.93 | 0.085 |

| 1237648705676575428 | 242.1748845 | 1.01672036 | 0.92 | 0.076 | |

| (72) | 1237660007354335814 | 62.17467871 | −1.016717 | 0.89 | 0.068 |

| 1237648705676575428 | 242.1748845 | 1.01672036 | 0.92 | 0.076 | |

| (73) | 1237666497028096412 | 62.17471675 | −1.0167112 | 0.92 | 0.089 |

| 1237655551815123559 | 242.1749457 | 1.01671526 | 0.92 | 0.088 | |

| (74) | 1237666497028096412 | 62.17471675 | −1.0167112 | 0.92 | 0.089 |

| 1237648705676575427 | 242.1748881 | 1.01671645 | 0.91 | 0.084 | |

| (75) | 1237648721222828169 | 161.910801 | −0.1931421 | 0.69 | 0.123 |

| 1237653012428554879 | 341.9117668 | 0.19238554 | 0.59 | 0.131 | |

| (76) | 1237648721222828169 | 161.910801 | −0.1931421 | 0.69 | 0.123 |

| 1237663479262544284 | 341.9117693 | 0.19240627 | 0.63 | 0.119 | |

| (77) | 1237648721222828169 | 161.910801 | −0.1931421 | 0.69 | 0.123 |

| 1237663479262544283 | 341.9117693 | 0.19240627 | 0.62 | 0.116 |

| Id SDSS DR8 | Ra | Dec | Sp | Zphot | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | 1237671139859628503 | 164.797490 | −21.936403 | 0.99 | 0.103 |

| 1237680273114923318 | 344.796820 | 21.936782 | 0.88 | 0.142 | |

| (2) | 1237671139859628503 | 164.797490 | −21.936403 | 0.99 | 0.103 |

| 1237679478537912674 | 344.796831 | 21.936789 | 0.85 | 0.123 | |

| (3) | 1237671239182254464 | 165.440684 | −20.397881 | 0.56 | 0.079 |

| 1237679476390560006 | 345.439848 | 20.398063 | 0.96 | 0.059 | |

| (4) | 1237671239182254464 | 165.440684 | −20.397881 | 0.56 | 0.079 |

| 1237680270967636262 | 345.439859 | 20.398065 | 0.95 | 0.058 | |

| (5) | 1237671239182254464 | 165.440684 | −20.397881 | 0.56 | 0.079 |

| 1237680270967636263 | 345.439855 | 20.398073 | 0.93 | 0.064 | |

| (6) | 1237671239182254464 | 165.440684 | −20.397881 | 0.56 | 0.079 |

| 1237679476390560005 | 345.439850 | 20.398083 | 0.96 | 0.058 | |

| (7) | 1237668756705771673 | 313.351245 | −17.157470 | 0.99 | 0.092 |

| 1237667539074023810 | 133.351503 | 17.157239 | 0.62 | 0.210 | |

| (8) | 1237668756705771673 | 313.351245 | −17.157470 | 0.99 | 0.092 |

| 1237667292113011156 | 133.351519 | 17.157253 | 0.56 | 0.154 | |

| (9) | 1237667247022604530 | 55.572846 | −11.962790 | 0.96 | 0.099 |

| 1237668350292328878 | 235.572915 | 11.963025 | 0.76 | 0.072 | |

| (10) | 1237667247022604530 | 55.572846 | −11.962790 | 0.96 | 0.099 |

| 1237668270839038355 | 235.572925 | 11.963054 | 0.78 | 0.058 | |

| (11) | 1237667726440530093 | 83.727284 | −6.167019 | 0.63 | 0.274 |

| 1237671693914146439 | 263.726548 | 6.167152 | 0.99 | 0.092 | |

| (12) | 1237680066953806059 | 334.767374 | −3.511891 | 0.99 | 0.067 |

| 1237654600491729036 | 154.766800 | 3.511264 | 0.97 | 0.117 | |

| (13) | 1237679079114932401 | 334.767352 | −3.511879 | 0.99 | 0.076 |

| 1237654600491729036 | 154.766800 | 3.511264 | 0.97 | 0.117 | |

| (14) | 1237679433981362251 | 359.485290 | −3.315196 | 0.65 | 0.063 |

| 1237651737367347360 | 179.485647 | 3.314965 | 0.84 | 0.086 | |

| (15) | 1237679433981362251 | 359.485290 | −3.315196 | 0.65 | 0.063 |

| 1237651737367347361 | 179.485641 | 3.314973 | 0.80 | 0.079 | |

| (16) | 1237679433981362253 | 359.485278 | −3.315192 | 0.74 | 0.066 |

| 1237651737367347360 | 179.485647 | 3.314965 | 0.84 | 0.086 | |

| (17) | 1237679433981362253 | 359.485278 | −3.315192 | 0.74 | 0.066 |

| 1237651737367347361 | 179.485641 | 3.314973 | 0.80 | 0.079 | |

| (18) | 1237672836917362790 | 359.485272 | −3.315190 | 0.71 | 0.061 |

| 1237651737367347360 | 179.485647 | 3.314965 | 0.84 | 0.086 | |

| (19) | 1237672836917362790 | 359.485272 | −3.315190 | 0.71 | 0.061 |

| 1237651737367347361 | 179.485641 | 3.314973 | 0.80 | 0.079 | |

| (20) | 1237678888521237046 | 26.569616 | −3.036691 | 0.99 | 0.076 |

| 1237674469000413486 | 206.569743 | 3.036762 | 0.85 | 0.115 | |

| (21) | 1237650372102127690 | 201.811091 | −1.152933 | 0.80 | 0.061 |

| 1237656909048971424 | 21.810940 | 1.153316 | 0.59 | 0.072 | |

| (22) | 1237650372102127690 | 201.811091 | −1.152933 | 0.80 | 0.061 |

| 1237666662924943502 | 21.810933 | 1.153321 | 0.56 | 0.070 | |

| (23) | 1237650372102127690 | 201.811091 | −1.152933 | 0.80 | 0.061 |

| 1237657235442630860 | 21.810947 | 1.153325 | 0.57 | 0.078 | |

| (24) | 1237650372102127690 | 201.811091 | −1.152933 | 0.80 | 0.061 |

| 1237657815262625899 | 21.810926 | 1.153330 | 0.57 | 0.075 | |

| (25) | 1237650372102127690 | 201.811091 | −1.152933 | 0.80 | 0.061 |

| 1237646588221128876 | 21.810946 | 1.153332 | 0.67 | 0.074 | |

| (26) | 1237650372102127690 | 201.811091 | −1.152933 | 0.80 | 0.061 |

| 1237666340801871988 | 21.810938 | 1.153333 | 0.59 | 0.072 | |

| (27) | 1237650372102127690 | 201.811091 | −1.152933 | 0.80 | 0.061 |

| 1237660237652623499 | 21.810934 | 1.153333 | 0.64 | 0.071 | |

| (28) | 1237650372102127690 | 201.811091 | −1.152933 | 0.80 | 0.061 |

| 1237662969220497579 | 21.810936 | 1.153334 | 0.67 | 0.073 | |

| (29) | 1237650372102127690 | 201.811091 | −1.152933 | 0.80 | 0.061 |

| 1237663205460607081 | 21.810925 | 1.153336 | 0.61 | 0.070 | |

| (30) | 1237650372102127690 | 201.811091 | −1.152933 | 0.80 | 0.061 |

| 1237657106606063792 | 21.810926 | 1.153337 | 0.65 | 0.077 | |

| (31) | 1237650372102127690 | 201.811091 | −1.152933 | 0.80 | 0.061 |

| 1237659915498881211 | 21.810939 | 1.153337 | 0.64 | 0.076 | |

| (32) | 1237650372102127690 | 201.811091 | −1.152933 | 0.80 | 0.061 |

| 1237660010021060695 | 21.810935 | 1.153338 | 0.58 | 0.069 | |

| (33) | 1237650372102127690 | 201.811091 | −1.152933 | 0.80 | 0.061 |

| 1237660010021060693 | 21.810943 | 1.153338 | 0.58 | 0.069 | |

| (34) | 1237650372102127690 | 201.811091 | −1.152933 | 0.80 | 0.061 |

| 1237663544779276481 | 21.810938 | 1.153343 | 0.59 | 0.074 | |

| (35) | 1237650372102127690 | 201.811091 | −1.152933 | 0.80 | 0.061 |

| 1237646588221128874 | 21.810953 | 1.153343 | 0.54 | 0.071 | |

| (36) | 1237650372102127690 | 201.811091 | −1.152933 | 0.80 | 0.061 |

| 1237657737950789725 | 21.810925 | 1.153345 | 0.64 | 0.073 | |

| (37) | 1237650372102127690 | 201.811091 | −1.152933 | 0.80 | 0.061 |

| 1237666409525739588 | 21.810911 | 1.153346 | 0.60 | 0.080 | |

| (38) | 1237650372102127690 | 201.811091 | −1.152933 | 0.80 | 0.061 |

| 1237656513889894587 | 21.810929 | 1.153348 | 0.59 | 0.072 | |

| (39) | 1237650372102127690 | 201.811091 | −1.152933 | 0.80 | 0.061 |

| 1237656513889894586 | 21.810936 | 1.153349 | 0.64 | 0.073 | |

| (40) | 1237650372102127690 | 201.811091 | −1.152933 | 0.80 | 0.061 |

| 1237657072230400220 | 21.810933 | 1.153349 | 0.61 | 0.076 | |

| (41) | 1237650372102127690 | 201.811091 | −1.152933 | 0.80 | 0.061 |

| 1237678617427378399 | 21.810925 | 1.153356 | 0.66 | 0.079 | |

| (42) | 1237650372102127690 | 201.811091 | −1.152933 | 0.80 | 0.061 |

| 1237678617427378397 | 21.810932 | 1.153362 | 0.59 | 0.076 | |

| (43) | 1237655500274270455 | 201.811109 | −1.152926 | 0.76 | 0.116 |

| 1237656909048971424 | 21.810940 | 1.153316 | 0.59 | 0.072 | |

| (44) | 1237655500274270455 | 201.811109 | −1.152926 | 0.76 | 0.116 |

| 1237666662924943502 | 21.810933 | 1.153321 | 0.56 | 0.070 | |

| (45) | 1237655500274270455 | 201.811109 | −1.152926 | 0.76 | 0.116 |

| 1237657235442630860 | 21.810947 | 1.153325 | 0.57 | 0.078 | |

| (46) | 1237655500274270455 | 201.811109 | −1.152926 | 0.76 | 0.116 |

| 1237657815262625899 | 21.810926 | 1.153330 | 0.57 | 0.075 | |

| (47) | 1237655500274270455 | 201.811109 | −1.152926 | 0.76 | 0.116 |

| 1237646588221128876 | 21.810946 | 1.153332 | 0.67 | 0.074 | |

| (48) | 1237655500274270455 | 201.811109 | −1.152926 | 0.76 | 0.116 |

| 1237666340801871988 | 21.810938 | 1.153333 | 0.59 | 0.072 | |

| (49) | 1237655500274270455 | 201.811109 | −1.152926 | 0.76 | 0.116 |

| 1237660237652623499 | 21.810934 | 1.153333 | 0.64 | 0.071 | |

| (50) | 1237655500274270455 | 201.811109 | −1.152926 | 0.76 | 0.116 |

| 1237662969220497579 | 21.810936 | 1.153334 | 0.67 | 0.073 | |

| (51) | 1237655500274270455 | 201.811109 | −1.152926 | 0.76 | 0.116 |

| 1237663205460607081 | 21.810925 | 1.153336 | 0.61 | 0.070 | |

| (52) | 1237655500274270455 | 201.811109 | −1.152926 | 0.76 | 0.116 |

| 1237657106606063792 | 21.810926 | 1.153337 | 0.65 | 0.077 | |

| (53) | 1237655500274270455 | 201.811109 | −1.152926 | 0.76 | 0.116 |

| 1237659915498881211 | 21.810939 | 1.153337 | 0.64 | 0.076 | |

| (54) | 1237655500274270455 | 201.811109 | −1.152926 | 0.76 | 0.116 |

| 1237660010021060695 | 21.810935 | 1.153338 | 0.58 | 0.069 | |

| (55) | 1237655500274270455 | 201.811109 | −1.152926 | 0.76 | 0.116 |

| 1237660010021060693 | 21.810943 | 1.153338 | 0.58 | 0.069 | |

| (56) | 1237655500274270455 | 201.811109 | −1.152926 | 0.76 | 0.116 |

| 1237663544779276481 | 21.810938 | 1.153343 | 0.59 | 0.074 | |

| (57) | 1237655500274270455 | 201.811109 | −1.152926 | 0.76 | 0.116 |

| 1237646588221128874 | 21.810953 | 1.153343 | 0.54 | 0.071 | |

| (58) | 1237655500274270455 | 201.811109 | −1.152926 | 0.76 | 0.116 |

| 1237657737950789725 | 21.810925 | 1.153345 | 0.64 | 0.073 | |

| (59) | 1237655500274270455 | 201.811109 | −1.152926 | 0.76 | 0.116 |

| 1237666409525739588 | 21.810911 | 1.153346 | 0.60 | 0.080 | |

| (60) | 1237655500274270455 | 201.811109 | −1.152926 | 0.76 | 0.116 |

| 1237656513889894587 | 21.810929 | 1.153348 | 0.59 | 0.072 | |

| (61) | 1237655500274270455 | 201.811109 | −1.152926 | 0.76 | 0.116 |

| 1237656513889894586 | 21.810936 | 1.153349 | 0.64 | 0.073 | |

| (62) | 1237655500274270455 | 201.811109 | −1.152926 | 0.76 | 0.116 |

| 1237657072230400220 | 21.810933 | 1.153349 | 0.61 | 0.076 | |

| (63) | 1237655500274270455 | 201.811109 | −1.152926 | 0.76 | 0.116 |

| 1237678617427378399 | 21.810925 | 1.153356 | 0.66 | 0.079 | |

| (64) | 1237655500274270455 | 201.811109 | −1.152926 | 0.76 | 0.116 |

| 1237678617427378397 | 21.810932 | 1.153362 | 0.59 | 0.076 | |

| (65) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.811089 | −1.152914 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237656909048971424 | 21.810940 | 1.153316 | 0.59 | 0.072 | |

| (66) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.811089 | −1.152914 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237666662924943502 | 21.810933 | 1.153321 | 0.56 | 0.070 | |

| (67) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.811089 | −1.152914 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237657235442630860 | 21.810947 | 1.153325 | 0.57 | 0.078 | |

| (68) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.811089 | −1.152914 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237657815262625899 | 21.810926 | 1.153330 | 0.57 | 0.075 | |

| (69) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.811089 | −1.152914 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237646588221128876 | 21.810946 | 1.153332 | 0.67 | 0.074 | |

| (70) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.811089 | −1.152914 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237666340801871988 | 21.810938 | 1.153333 | 0.59 | 0.072 | |

| (71) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.811089 | −1.152914 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237660237652623499 | 21.810934 | 1.153333 | 0.64 | 0.071 | |

| (72) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.811089 | −1.152914 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237662969220497579 | 21.810936 | 1.153334 | 0.67 | 0.073 | |

| (73) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.811089 | −1.152914 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237663205460607081 | 21.810925 | 1.153336 | 0.61 | 0.070 | |

| (74) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.811089 | −1.152914 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237657106606063792 | 21.810926 | 1.153337 | 0.65 | 0.077 | |

| (75) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.811089 | −1.152914 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237659915498881211 | 21.810939 | 1.153337 | 0.64 | 0.076 | |

| (76) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.811089 | −1.152914 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237660010021060695 | 21.810935 | 1.153338 | 0.58 | 0.069 | |

| (77) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.811089 | −1.152914 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237660010021060693 | 21.810943 | 1.153338 | 0.58 | 0.069 | |

| (78) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.811089 | −1.152914 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237663544779276481 | 21.810938 | 1.153343 | 0.59 | 0.074 | |

| (79) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.811089 | −1.152914 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237646588221128874 | 21.810953 | 1.153343 | 0.54 | 0.071 | |

| (80) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.811089 | −1.152914 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237657737950789725 | 21.810925 | 1.153345 | 0.64 | 0.073 | |

| (81) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.811089 | −1.152914 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237666409525739588 | 21.810911 | 1.153346 | 0.60 | 0.080 | |

| (82) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.811089 | −1.152914 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237656513889894587 | 21.810929 | 1.153348 | 0.59 | 0.072 | |

| (83) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.811089 | −1.152914 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237656513889894586 | 21.810936 | 1.153349 | 0.64 | 0.073 | |

| (84) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.811089 | −1.152914 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237657072230400220 | 21.810933 | 1.153349 | 0.61 | 0.076 | |

| (85) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.811089 | −1.152914 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237678617427378399 | 21.810925 | 1.153356 | 0.66 | 0.079 | |

| (86) | 1237651709428367652 | 201.811089 | −1.152914 | 0.82 | 0.079 |

| 1237678617427378397 | 21.810932 | 1.153362 | 0.59 | 0.076 | |

| (87) | 1237651279931506991 | 201.811075 | −1.152912 | 0.76 | 0.085 |

| 1237656909048971424 | 21.810940 | 1.153316 | 0.59 | 0.072 | |

| (88) | 1237651279931506991 | 201.811075 | −1.152912 | 0.76 | 0.085 |

| 1237666662924943502 | 21.810933 | 1.153321 | 0.56 | 0.070 | |

| (89) | 1237651279931506991 | 201.811075 | −1.152912 | 0.76 | 0.085 |

| 1237657235442630860 | 21.810947 | 1.153325 | 0.57 | 0.078 | |

| (90) | 1237651279931506991 | 201.811075 | −1.152912 | 0.76 | 0.085 |

| 1237657815262625899 | 21.810926 | 1.153330 | 0.57 | 0.075 | |

| (91) | 1237651279931506991 | 201.811075 | −1.152912 | 0.76 | 0.085 |

| 1237646588221128876 | 21.810946 | 1.153332 | 0.67 | 0.074 | |

| (92) | 1237651279931506991 | 201.811075 | −1.152912 | 0.76 | 0.085 |

| 1237666340801871988 | 21.810938 | 1.153333 | 0.59 | 0.072 | |

| (93) | 1237651279931506991 | 201.811075 | −1.152912 | 0.76 | 0.085 |

| 1237660237652623499 | 21.810934 | 1.153333 | 0.64 | 0.071 | |

| (94) | 1237651279931506991 | 201.811075 | −1.152912 | 0.76 | 0.085 |

| 1237662969220497579 | 21.810936 | 1.153334 | 0.67 | 0.073 | |

| (95) | 1237651279931506991 | 201.811075 | −1.152912 | 0.76 | 0.085 |

| 1237663205460607081 | 21.810925 | 1.153336 | 0.61 | 0.070 | |

| (96) | 1237651279931506991 | 201.811075 | −1.152912 | 0.76 | 0.085 |

| 1237657106606063792 | 21.810926 | 1.153337 | 0.65 | 0.077 | |

| (97) | 1237651279931506991 | 201.811075 | −1.152912 | 0.76 | 0.085 |

| 1237659915498881211 | 21.810939 | 1.153337 | 0.64 | 0.076 | |

| (98) | 1237651279931506991 | 201.811075 | −1.152912 | 0.76 | 0.085 |

| 1237660010021060695 | 21.810935 | 1.153338 | 0.58 | 0.069 | |

| (99) | 1237651279931506991 | 201.811075 | −1.152912 | 0.76 | 0.085 |

| 1237660010021060693 | 21.810943 | 1.153338 | 0.58 | 0.069 | |

| (100) | 1237651279931506991 | 201.811075 | −1.152912 | 0.76 | 0.085 |

| 1237663544779276481 | 21.810938 | 1.153343 | 0.59 | 0.074 | |

| (101) | 1237651279931506991 | 201.811075 | −1.152912 | 0.76 | 0.085 |

| 1237646588221128874 | 21.810953 | 1.153343 | 0.54 | 0.071 | |

| (102) | 1237651279931506991 | 201.811075 | −1.152912 | 0.76 | 0.085 |

| 1237657737950789725 | 21.810925 | 1.153345 | 0.64 | 0.073 | |

| (103) | 1237651279931506991 | 201.811075 | −1.152912 | 0.76 | 0.085 |

| 1237666409525739588 | 21.810911 | 1.153346 | 0.60 | 0.080 | |

| (104) | 1237651279931506991 | 201.811075 | −1.152912 | 0.76 | 0.085 |

| 1237656513889894587 | 21.810929 | 1.153348 | 0.59 | 0.072 | |

| (105) | 1237651279931506991 | 201.811075 | −1.152912 | 0.76 | 0.085 |

| 1237656513889894586 | 21.810936 | 1.153349 | 0.64 | 0.073 | |

| (106) | 1237651279931506991 | 201.811075 | −1.152912 | 0.76 | 0.085 |

| 1237657072230400220 | 21.810933 | 1.153349 | 0.61 | 0.076 | |

| (107) | 1237651279931506991 | 201.811075 | −1.152912 | 0.76 | 0.085 |

| 1237678617427378399 | 21.810925 | 1.153356 | 0.66 | 0.079 | |

| (108) | 1237651279931506991 | 201.811075 | −1.152912 | 0.76 | 0.085 |

| 1237678617427378397 | 21.810932 | 1.153362 | 0.59 | 0.076 | |

| (109) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.811090 | −1.152907 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237656909048971424 | 21.810940 | 1.153316 | 0.59 | 0.072 | |

| (110) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.811090 | −1.152907 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237666662924943502 | 21.810933 | 1.153321 | 0.56 | 0.070 | |

| (111) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.811090 | −1.152907 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237657235442630860 | 21.810947 | 1.153325 | 0.57 | 0.078 | |

| (112) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.811090 | −1.152907 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237657815262625899 | 21.810926 | 1.153330 | 0.57 | 0.075 | |

| (113) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.811090 | −1.152907 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237646588221128876 | 21.810946 | 1.153332 | 0.67 | 0.074 | |

| (114) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.811090 | −1.152907 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237666340801871988 | 21.810938 | 1.153333 | 0.59 | 0.072 | |

| (115) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.811090 | −1.152907 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237660237652623499 | 21.810934 | 1.153333 | 0.64 | 0.071 | |

| (116) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.811090 | −1.152907 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237662969220497579 | 21.810936 | 1.153334 | 0.67 | 0.073 | |

| (117) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.811090 | −1.152907 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237663205460607081 | 21.810925 | 1.153336 | 0.61 | 0.070 | |

| (118) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.811090 | −1.152907 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237657106606063792 | 21.810926 | 1.153337 | 0.65 | 0.077 | |

| (119) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.811090 | −1.152907 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237659915498881211 | 21.810939 | 1.153337 | 0.64 | 0.076 | |

| (120) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.811090 | −1.152907 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237660010021060695 | 21.810935 | 1.153338 | 0.58 | 0.069 | |

| (121) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.811090 | −1.152907 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237660010021060693 | 21.810943 | 1.153338 | 0.58 | 0.069 | |

| (122) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.811090 | −1.152907 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237663544779276481 | 21.810938 | 1.153343 | 0.59 | 0.074 | |

| (123) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.811090 | −1.152907 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237646588221128874 | 21.810953 | 1.153343 | 0.54 | 0.071 | |

| (124) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.811090 | −1.152907 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237657737950789725 | 21.810925 | 1.153345 | 0.64 | 0.073 | |

| (125) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.811090 | −1.152907 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237666409525739588 | 21.810911 | 1.153346 | 0.60 | 0.080 | |

| (126) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.811090 | −1.152907 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237656513889894587 | 21.810929 | 1.153348 | 0.59 | 0.072 | |

| (127) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.811090 | −1.152907 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237656513889894586 | 21.810936 | 1.153349 | 0.64 | 0.073 | |

| (128) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.811090 | −1.152907 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237657072230400220 | 21.810933 | 1.153349 | 0.61 | 0.076 | |

| (129) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.811090 | −1.152907 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237678617427378399 | 21.810925 | 1.153356 | 0.66 | 0.079 | |

| (130) | 1237648702974525748 | 201.811090 | −1.152907 | 0.82 | 0.071 |

| 1237678617427378397 | 21.810932 | 1.153362 | 0.59 | 0.076 | |

| (131) | 1237666406859014666 | 62.174674 | −1.016796 | 0.90 | 0.081 |

| 1237655551815123559 | 242.174946 | 1.016715 | 0.92 | 0.088 | |

| (132) | 1237666406859014666 | 62.174674 | −1.016796 | 0.90 | 0.081 |

| 1237648705676575427 | 242.174888 | 1.016716 | 0.91 | 0.084 | |

| (133) | 1237666406859014666 | 62.174674 | −1.016796 | 0.90 | 0.081 |

| 1237648705676575428 | 242.174884 | 1.016720 | 0.92 | 0.076 | |

| (134) | 1237646748740026642 | 62.174702 | −1.016792 | 0.90 | 0.099 |

| 1237655551815123559 | 242.174946 | 1.016715 | 0.92 | 0.088 | |

| (135) | 1237646748740026642 | 62.174702 | −1.016792 | 0.90 | 0.099 |

| 1237648705676575427 | 242.174888 | 1.016716 | 0.91 | 0.084 | |

| (136) | 1237646748740026642 | 62.174702 | −1.016792 | 0.90 | 0.099 |

| 1237648705676575428 | 242.174884 | 1.016720 | 0.92 | 0.076 | |

| (137) | 1237652997934416225 | 62.174709 | −1.016787 | 0.89 | 0.074 |

| 1237655551815123559 | 242.174946 | 1.016715 | 0.92 | 0.088 | |

| (138) | 1237652997934416225 | 62.174709 | −1.016787 | 0.89 | 0.074 |

| 1237648705676575427 | 242.174888 | 1.016716 | 0.91 | 0.084 | |

| (139) | 1237652997934416225 | 62.174709 | −1.016787 | 0.89 | 0.074 |

| 1237648705676575428 | 242.174884 | 1.016720 | 0.92 | 0.076 | |

| (140) | 1237657761048166683 | 62.174720 | −1.016787 | 0.89 | 0.113 |

| 1237655551815123559 | 242.174946 | 1.016715 | 0.92 | 0.088 | |

| (141) | 1237657761048166683 | 62.174720 | −1.016787 | 0.89 | 0.113 |

| 1237648705676575427 | 242.174888 | 1.016716 | 0.91 | 0.084 | |

| (142) | 1237657761048166683 | 62.174720 | −1.016787 | 0.89 | 0.113 |

| 1237648705676575428 | 242.174884 | 1.016720 | 0.92 | 0.076 | |

| (143) | 1237646748740026643 | 62.174751 | −1.016781 | 0.90 | 0.076 |

| 1237655551815123559 | 242.174946 | 1.016715 | 0.92 | 0.088 | |

| (144) | 1237646748740026643 | 62.174751 | −1.016781 | 0.90 | 0.076 |

| 1237648705676575427 | 242.174888 | 1.016716 | 0.91 | 0.084 | |

| (145) | 1237646748740026643 | 62.174751 | −1.016781 | 0.90 | 0.076 |

| 1237648705676575428 | 242.174884 | 1.016720 | 0.92 | 0.076 | |

| (146) | 1237649823937986797 | 62.174705 | −1.016778 | 0.89 | 0.071 |

| 1237655551815123559 | 242.174946 | 1.016715 | 0.92 | 0.088 | |

| (147) | 1237649823937986797 | 62.174705 | −1.016778 | 0.89 | 0.071 |

| 1237648705676575427 | 242.174888 | 1.016716 | 0.91 | 0.084 | |

| (148) | 1237649823937986797 | 62.174705 | −1.016778 | 0.89 | 0.071 |

| 1237648705676575428 | 242.174884 | 1.016720 | 0.92 | 0.076 | |

| (149) | 1237646585554469394 | 62.174713 | −1.016760 | 0.91 | 0.083 |

| 1237655551815123559 | 242.174946 | 1.016715 | 0.92 | 0.088 | |

| (150) | 1237646585554469394 | 62.174713 | −1.016760 | 0.91 | 0.083 |

| 1237648705676575427 | 242.174888 | 1.016716 | 0.91 | 0.084 | |

| (151) | 1237646585554469394 | 62.174713 | −1.016760 | 0.91 | 0.083 |

| 1237648705676575428 | 242.174884 | 1.016720 | 0.92 | 0.076 | |

| (152) | 1237666497028096411 | 62.174701 | −1.016724 | 0.93 | 0.085 |

| 1237655551815123559 | 242.174946 | 1.016715 | 0.92 | 0.088 | |

| (153) | 1237666497028096411 | 62.174701 | −1.016724 | 0.93 | 0.085 |

| 1237648705676575427 | 242.174888 | 1.016716 | 0.91 | 0.084 | |

| (154) | 1237666497028096411 | 62.174701 | −1.016724 | 0.93 | 0.085 |

| 1237648705676575428 | 242.174884 | 1.016720 | 0.92 | 0.076 | |

| (155) | 1237660007354335814 | 62.174679 | −1.016717 | 0.89 | 0.068 |

| 1237655551815123559 | 242.174946 | 1.016715 | 0.92 | 0.088 | |

| (156) | 1237660007354335814 | 62.174679 | −1.016717 | 0.89 | 0.068 |

| 1237648705676575427 | 242.174888 | 1.016716 | 0.91 | 0.084 | |

| (157) | 1237660007354335814 | 62.174679 | −1.016717 | 0.89 | 0.068 |

| 1237648705676575428 | 242.174884 | 1.016720 | 0.92 | 0.076 | |

| (158) | 1237666497028096412 | 62.174717 | −1.016711 | 0.92 | 0.089 |

| 1237655551815123559 | 242.174946 | 1.016715 | 0.92 | 0.088 | |

| (159) | 1237666497028096412 | 62.174717 | −1.016711 | 0.92 | 0.089 |

| 1237648705676575427 | 242.174888 | 1.016716 | 0.91 | 0.084 | |

| (160) | 1237666497028096412 | 62.174717 | −1.016711 | 0.92 | 0.089 |

| 1237648705676575428 | 242.174884 | 1.016720 | 0.92 | 0.076 | |

| (161) | 1237666497538883899 | 2.523832 | −0.444620 | 0.66 | 0.260 |

| 1237648705113555092 | 182.524814 | 0.444527 | 0.57 | 0.110 | |

| (162) | 1237666497538883899 | 2.523832 | −0.444620 | 0.66 | 0.260 |

| 1237674651003519212 | 182.524830 | 0.444553 | 0.68 | 0.088 | |

| (163) | 1237666299997782594 | 2.523821 | −0.444607 | 0.72 | 0.310 |

| 1237648705113555092 | 182.524814 | 0.444527 | 0.57 | 0.110 | |

| (164) | 1237648673959378974 | 161.910785 | −0.193158 | 0.79 | 0.150 |

| 1237653012428554879 | 341.911767 | 0.192386 | 0.59 | 0.131 | |

| (165) | 1237648673959378974 | 161.910785 | −0.193158 | 0.79 | 0.150 |

| 1237663479262544284 | 341.911769 | 0.192406 | 0.63 | 0.119 | |

| (166) | 1237648673959378974 | 161.910785 | −0.193158 | 0.79 | 0.150 |

| 1237663479262544283 | 341.911769 | 0.192406 | 0.62 | 0.116 | |

| (167) | 1237648673959378974 | 161.910785 | −0.193158 | 0.79 | 0.150 |

| 1237663526510395758 | 341.911752 | 0.192409 | 0.74 | 0.135 | |

| (168) | 1237648721222828169 | 161.910801 | −0.193142 | 0.69 | 0.123 |

| 1237653012428554879 | 341.911767 | 0.192386 | 0.59 | 0.131 | |

| (169) | 1237648721222828169 | 161.910801 | −0.193142 | 0.69 | 0.123 |

| 1237663479262544284 | 341.911769 | 0.192406 | 0.63 | 0.119 | |

| (170) | 1237648721222828169 | 161.910801 | −0.193142 | 0.69 | 0.123 |

| 1237663479262544283 | 341.911769 | 0.192406 | 0.62 | 0.116 | |

| (171) | 1237648721222828169 | 161.910801 | −0.193142 | 0.69 | 0.123 |

| 1237663526510395758 | 341.911752 | 0.192409 | 0.74 | 0.135 |

| SpecObjID | Ra | Dec | z | Elliptical | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | 4839208601778651136 | 2.66932 | 1.37162 | 0.2678 | 0.935 |

| 4329151476691107840 | 182.669 | −1.3722 | 0.5809 | 0.892 | |

| (2) | 4914588370669666304 | 2.99248 | −3.2495 | 0.0003 | 0.861 |

| 5346040858121076736 | 182.993 | 3.24996 | 0.6052 | 0.958 | |

| (3) | 734224488962484224 | 4.30274 | −9.4565 | 0.1170 | 0.663 |

| 6075454403388112896 | 184.303 | 9.45639 | 2.4796 | 0.730 | |

| (4) | 734242081148528640 | 4.62338 | −8.8278 | 0.1047 | 0.686 |

| 1384895138274240512 | 184.623 | 8.82687 | 0.4819 | 0.997 | |

| (5) | 1680006812310464512 | 5.91966 | 0.54668 | 0.0596 | 0.709 |

| 4331440114590285824 | 185.92 | −0.546 | 0.5116 | 0.995 | |

| (6) | 735378151655368704 | 6.86606 | −8.8217 | 0.1888 | 0.550 |

| 1830869162549864448 | 186.866 | 8.822 | 0.0855 | 0.911 | |

| (7) | 4844864764419506176 | 8.16193 | 2.99506 | 0.4595 | 0.708 |

| 376056649636407296 | 188.161 | −2.9954 | 0.0991 | 0.792 | |

| (8) | 4919173338989330432 | 9.19367 | −2.8909 | 0.4721 | 0.999 |

| 5351416371190693888 | 189.193 | 2.89151 | 0.5333 | 0.999 | |

| (9) | 4753611070676402176 | 10.3652 | −0.5698 | 0.4595 | 0.994 |

| 4333736164478943232 | 190.365 | 0.5689 | 0.0006 | 0.661 | |

| (10) | 4039789700742381568 | 10.3652 | −0.5698 | 0.4594 | 0.995 |

| 4333736164478943232 | 190.365 | 0.5689 | 0.0006 | 0.661 | |

| (11) | 4920278343259521024 | 11.2634 | −2.7318 | 0.3479 | 0.998 |

| 5353712700990423040 | 191.263 | 2.73184 | 0.4950 | 0.636 | |

| (12) | 1683253395470706688 | 11.3174 | −0.1229 | 0.4762 | 0.913 |

| 4333669644025462784 | 191.318 | 0.12199 | 0.0004 | 0.788 | |

| (13) | 778123041480665088 | 11.5428 | 1.11225 | 0.2160 | 0.885 |

| 4270781151322832896 | 191.542 | −1.1128 | 0.5737 | 0.877 | |

| (14) | 4920246732300222464 | 11.7652 | −2.4001 | 0.5587 | 0.995 |

| 5354974390096756736 | 191.766 | 2.40077 | 0.4318 | 0.966 | |

| (15) | 779218704851298304 | 12.1667 | 0.06339 | 0.3315 | 0.827 |

| 4333606696984772608 | 192.167 | −0.0629 | 0.6460 | 0.988 | |

| (16) | 4848371932909273088 | 12.7862 | 2.31558 | 0.3916 | 0.995 |

| 4254850052604297216 | 192.786 | −2.3157 | 0.3638 | 0.927 | |

| (17) | 4755887885000376320 | 13.4472 | −0.2816 | 0.6521 | 0.988 |

| 4334910722825256960 | 193.448 | 0.28142 | 0.6379 | 0.998 | |

| (18) | 4921514474173104128 | 13.5581 | −1.4265 | 0.6410 | 0.891 |

| 4334919244040372224 | 193.559 | 1.42684 | 2.7379 | 0.512 | |

| (19) | 1219440076220557312 | 13.8081 | 1.19783 | 0.1501 | 0.630 |

| 4334772459238064128 | 193.809 | −1.1978 | 0.0008 | 0.784 | |

| (20) | 445869587716663296 | 16.9041 | −1.2101 | 0.1278 | 0.744 |

| 4511605535782993920 | 196.904 | 1.21051 | 0.6376 | 0.920 | |

| (21) | 4858431363432841216 | 17.7868 | 2.55229 | 0.1187 | 0.975 |

| 4563366149601361920 | 197.787 | −2.5522 | 0.4748 | 0.999 | |

| (22) | 781377596066654208 | 18.153 | −0.8043 | 0.4344 | 0.825 |

| 4511537915817885696 | 198.152 | 0.8038 | 0.4538 | 0.743 | |

| (23) | 447132651329972224 | 18.6371 | 0.23377 | 0.0449 | 0.812 |

| 3294404095737096192 | 198.638 | −0.233 | 0.0003 | 0.524 | |

| (24) | 743193205964564480 | 19.0036 | −8.5384 | 0.1251 | 0.834 |

| 2023364803757631488 | 199.003 | 8.53769 | 0.0524 | 0.910 | |

| (25) | 783713783397771264 | 19.6607 | −0.1202 | 0.0774 | 0.815 |