1. Introduction

The first detection of gravitational waves from the neutron-star-merger GW170817 [

1], has generated considerable interest in the equation of state (EOS) of matter created in such extreme events. In these events, temperatures of tens of MeV are expected to be generated over regions that vary in density by several orders of magnitude. Therefore, it is imperative to adopt EOS descriptions in which the symmetries and degrees of freedom change according to the local temperature and density conditions of the system. From the point of view of merger simulations, it is important to use a small grid for the simulation to capture the complexity of the event.

In this work, we present a compilation of former works that treated separately the low- and high-density regimes expected to be formed in neutron-star mergers. First, we discuss an extension of the excluded volume (EV) approach, which takes into consideration light nuclei beyond the usual -particle in the subnuclear regime. Here, the EOS of Akmal, Pandharipande, and Ravenhall (APR) is used as the underlying description for interacting nucleons. Second, for the description of the supranuclear regime, we discuss the Chiral Mean Field (CMF) formalism, in which the hadronic degrees of freedom include both nucleons and hyperons. For sufficiently high temperature and/or density, the CMF model incorporates a first-order phase transition to deconfined quark matter. The merger simulations of this work are performed using a covariant general-relativistic description of hydrodynamics coupled to a fully general-relativistic spacetime evolution. The numerical grid in the simulation achieves the highest resolution of 250 m covering the two stars and a total extent of 1500 km.

2. Subnuclear Density

In this section, we discuss the subnuclear density region, which we take to be fm. Besides density, thermodynamic variables also depend on temperature T and electron fraction , the latter being equal to baryonic charge fraction due to the charge neutrality requirement. In this regime, a uniform phase of nucleonic matter would be mechanically (spinodally) unstable, which would give rise to a negative compressibility. Although this instability shrinks in size with increasing isospin asymmetry (lower electron/charge faction), it does not disappear for small temperatures. As a solution to the problem, an inhomogeneous phase must be included in the formalism. In our case, it consists (in addition to nucleons and electrons) of light nuclear clusters. As a result, the mechanical instability is lifted for MeV. At lower temperatures, mechanically stable configurations must necessarily include heavy nuclei () and/or pasta phases.

In the EV approach, the -particles and other light nuclei (H, and He, and He) are assumed to be structureless and their interactions with “outside” nucleons are taken into account by treating them as rigid spheres of constant volume. This treatment accounts only for repulsive interactions, the attractive ones being deemed small. The total free energy density can be decomposed as , where the different terms stand for baryon, electron, and photon contributions. The baryon contribution consists of a nuclear contribution given by non-interacting Boltzmann gases and an “outside” nucleon contribution given by the APR EoS.

The APR EOS is a Skyme-like parametric fit [

2] to the microscopic calculations of Akmal and Pandharipande [

3], where the NN interaction is described by the Argonne-18 2-body potential, a modified Urbana-IX 3-body potential (so that the binding energy of isospin-symmetric nuclear matter is −16 MeV), and a 2-body relativistic boost potential. The Argonne-18 potential is a high precision fit to the Nijmegen scattering database, such that it reproduces phase shifts and scattering lengths. The Urbana-IX describes 2-pion exchange and includes phenomenological in-medium modifications (involving

isobars) to the 2-body interaction. The boost potential is a correction to the 2-body potential when the interaction is observed in a frame other than the rest-frame of the nucleons. The expectation value of the ground state corresponding to the total potential is determined by variational chain summation techniques using a variational wave-function consisting of a symmetrized product of pair-correlation operators acting on the Fermi gas wave-function. As a result, isospin-symmetric nuclear matter equilibrium bulk properties other than

and

are predictions of the model, instead of quantities to which it is fitted.

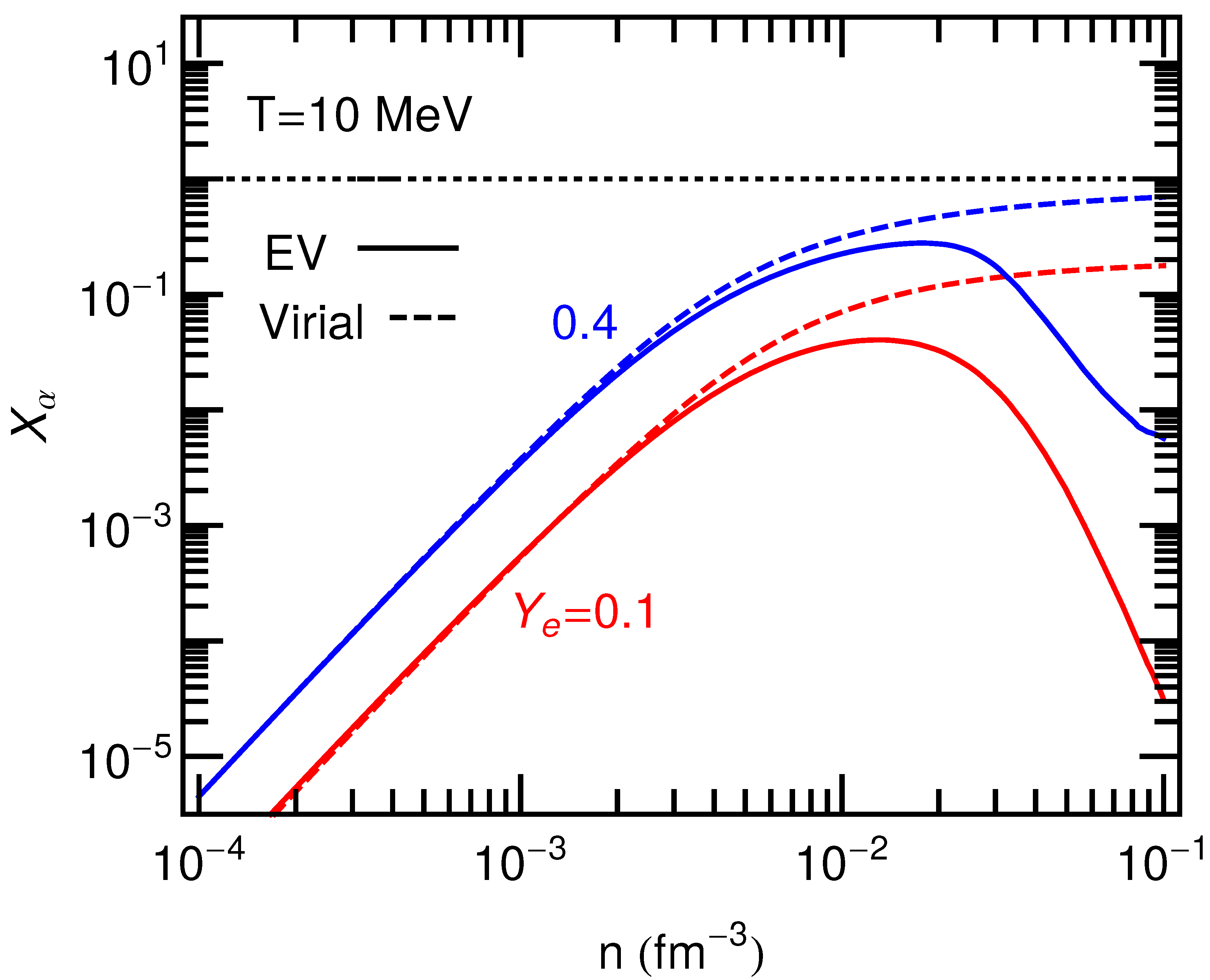

Figure 1, shows a comparison of EV with virial expansion results for

matter. The virial approach includes bound and continuum state corrections to the ideal gas results for thermal variables [

4]. It is model-independent, as experimental phase-shift data are used as input for the theory. The pressure is obtained from the partition function

according to

and it is expressed in terms of the fugacities

, (

, n, p) and the 2nd virial coefficients

, which are simple integrals involving thermal weights and elastic scattering phase shifts. As expected, there are fewer

particles at lower lepton fractions (blue vs. red curves). The APR/EV approach predicts significantly lower

-particle populations at large densities relative to the virial approach (solid vs dashed curves). This is a consequence of only repulsive interactions being included in the EV approach, which is not the case in the virial approach. In the latter, owing to the lack of sufficiently high-energy data such that the nuclear hard-core is resolved, the

-nucleon interaction is predominantly attractive. The sudden disappearance of the

particles causes a change in slope in the baryonic component of thermodynamic quantities. In the case of lower temperatures, this causes a non-monotonic behavior in the baryonic component of thermodynamic quantities. The non-monotonic behavior is smoothed out when other light nuclei are considered (see Ref. [

5] for more details).

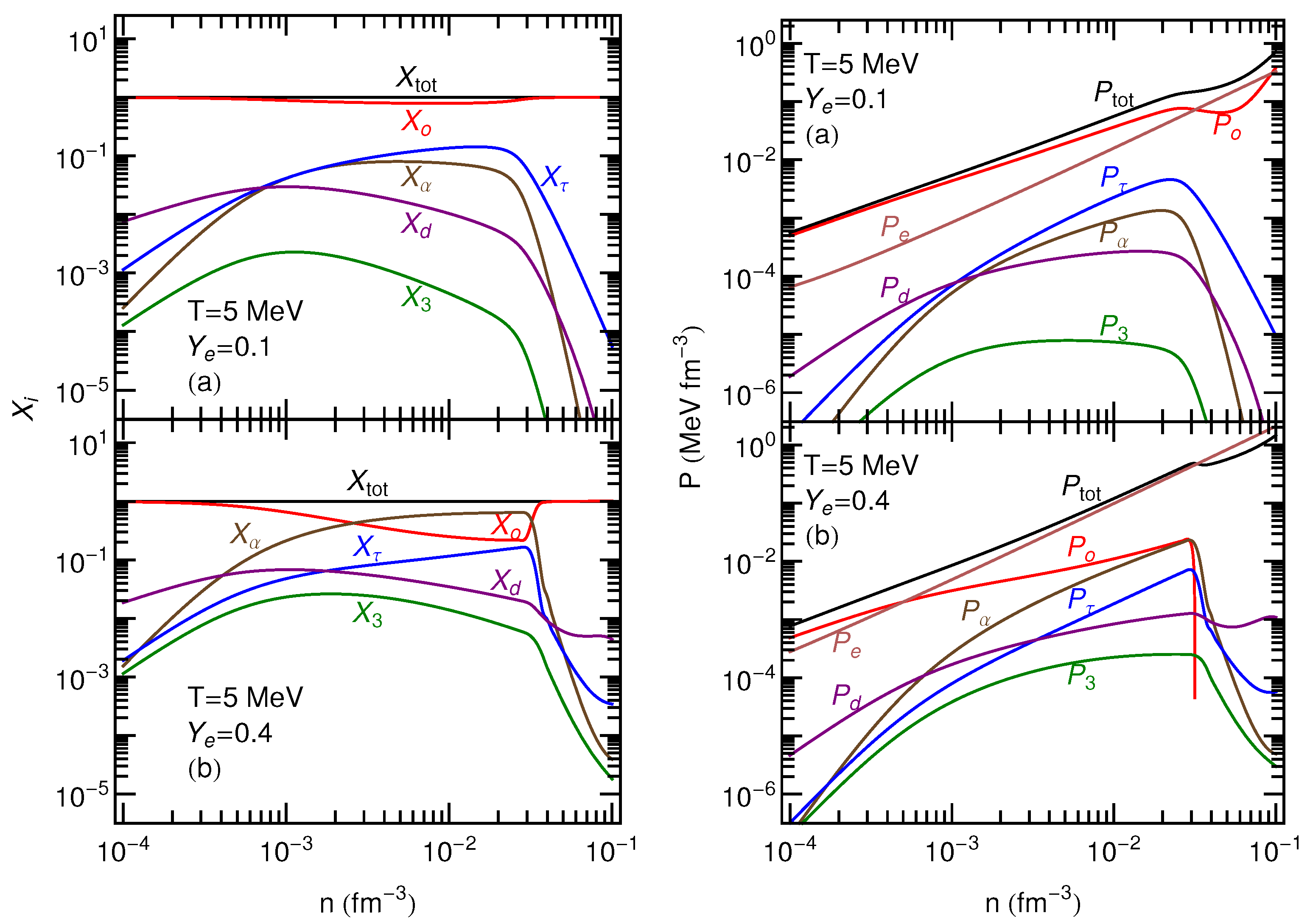

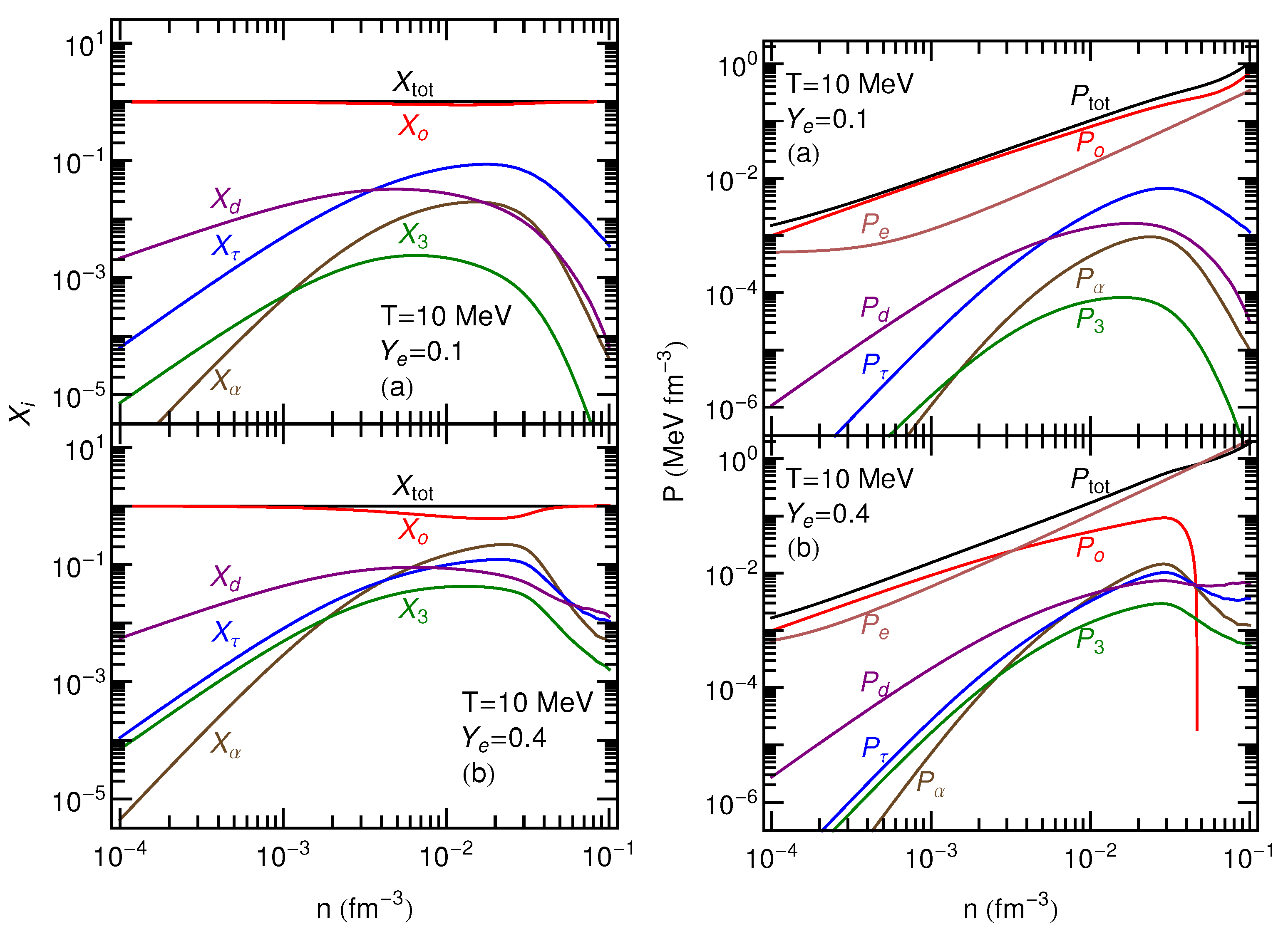

The mass fractions of the various light nuclear clusters, as calculated by applying the EV approach to the APR EOS, are presented in the left panels of

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 for temperatures of 5 MeV and 10 MeV, respectively. These are determined by a combination of the charge and baryon number conservation laws, the binding energy of each type of nucleus, and local conditions (

). The density at which a particular species vanishes is primarily controlled by the EV

assigned to it. In this instance, we are using the corresponding experimentally determined charge radii. Note, however, that this choice is by no means compulsory. For example, in Ref. [

6],

was obtained by calculating the effective interaction range consistent with an optical potential fitted to neutron-

scattering data. Moreover, the presence of heavy nuclei (not taken into account here) will also affect the relative particle concentrations.

The right panels of

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 show the contributions of light nuclei, nucleons, and electrons to the total pressure. Being that the light nuclei are treated as non-interacting gases, their pressures are given by classical ideal gas expressions,

, modulated by EV factors. The latter act significantly only at the higher end of the density range considered here and cause the populations of the light nuclei to decline. Please note that electronic contributions dominate at higher densities and even more so as

increases (lower panels). The negative slope in the total pressure around 0.03 fm

in the bottom right panel of

Figure 2 is related to the spinodal instability of purely nucleonic matter (and, therefore, the nuclear liquid-gas phase transition) which is more pronounced at lower temperatures and for more isospin-symmetric configurations. This unphysical behavior is not present in the bottom right panel of

Figure 3. Even though the APR liquid-gas critical temperature of about 18 MeV has not been reached in this case, mainly due to electrons, and to a lesser extend to the light nuclei, the total pressure remains monotonically increasing at 10 MeV temperature.

3. Supranuclear Density

For densities larger than

, matter is too dense for nuclei of any type to form and, thus, consists of uniformly distributed nucleons and electrons. On one hand, effective field theory has already enabled first-principle calculations of isospin-symmetric and asymmetric matter with systematic corrections. On the other, continuing beyond

to encompass the central densities of neutron stars is precluded in these methods, as the perturbative expansion parameter reaches uncomfortably large values (see Ref. [

7] for a recent review of the topic). Phenomenological approaches based on non-relativistic potential models with contact and finite-range interactions have long been used to explore the EOS at supranuclear densities, the advantage of these models being that calculations are relatively easier than first-principle calculations. However, higher-than-two-body interactions, found necessary to fit constraints offered by laboratory data on nuclei at near-nuclear densities, can render these EOS’s acausal at large density due to the lack of Lorentz invariance in a non-relativistic approach. These higher-than-two-body interactions correspond to terms in the energy density which vary as

with

. At sufficiently high densities, they will dominate all other contributions including the thermal parts and lead to superluminal behavior

.

As a solution to this problem, relativistic Dirac-Brueckner-Hartree-Fock [

8,

9,

10,

11] and mean field-theoretical [

12] models are used at supranuclear densities, as they and their extensions are inherently Lorentz invariant and, thus, preserve causality. We choose to work with the CMF model, which is based on a nonlinear realization of the SU(3) sigma model [

13]. This framework incorporates chiral symmetry and its restoration at large densities and temperatures, as predicted in QCD. Being that hadrons and quarks in the CMF model interact via meson exchange in a chirally invariant manner, the various particle masses originate from interactions with the medium. The model in this specific parametrization is in agreement with standard nuclear and astrophysical constraints [

14,

15], as well as lattice QCD and perturbative QCD [

16,

17]. In particular, in the limit of zero-temperature and zero-angular momentum, it predicts a maximum mass of

for a hadronic star and

when quarks are included.

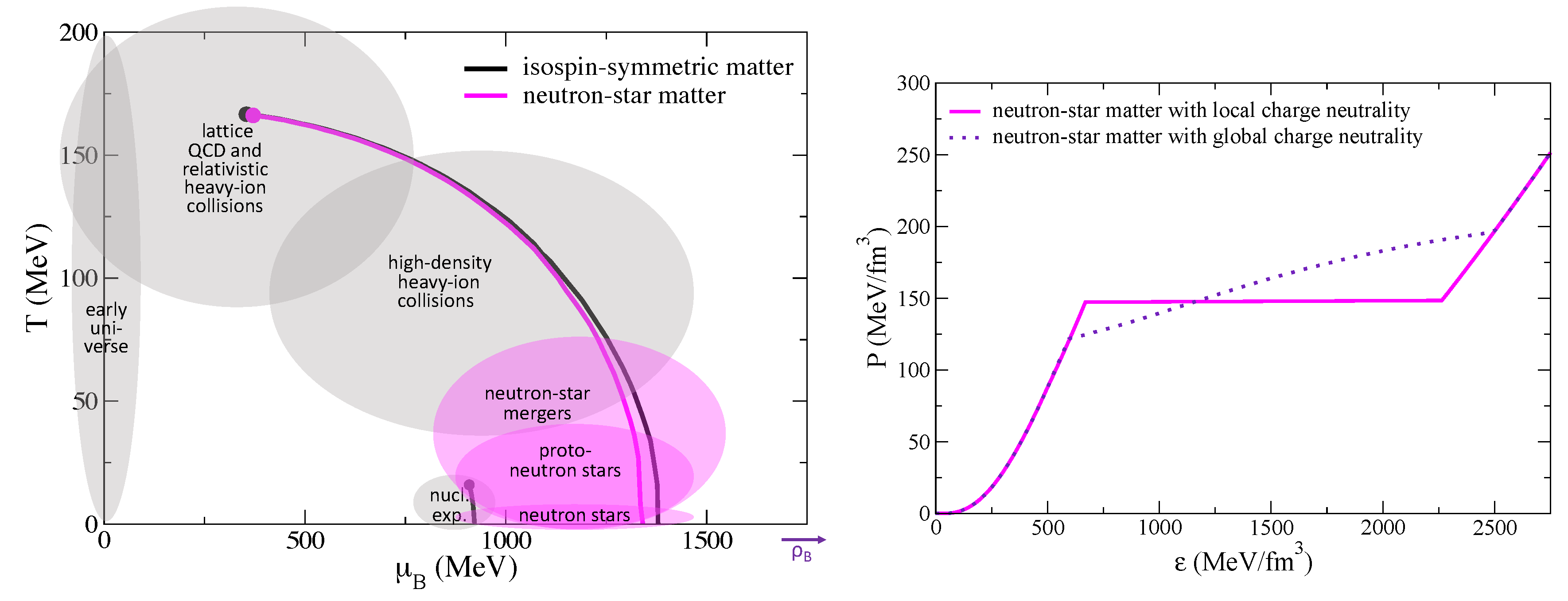

This approach allows for the existence of soluted quarks in the hadronic phase and soluted hadrons in the quark phase at finite temperature. However, quarks (hadrons) will always give the dominant contribution in the quark (hadron) phase, and the two phases can be distinguished by their approximate order parameters, e.g., the chiral condensate

for chiral symmetry restoration or the field

for deconfinement (named in analogy with the Polyakov loop). This inter-penetration of quarks and hadrons (that increases with temperature) provides a physically effective description and is indeed required to achieve the crossover transition known to take place at small chemical potential values [

18]. The left panel of

Figure 4 contains the QCD phase diagram (modified from Ref. [

19]) resulting from the CMF model and illustrates these features. The right panel in

Figure 4 shows the neutron-star matter EOS (assuming charge neutrality and chemical equilibrium) at zero temperature calculated from the CMF model. It can be seen that if the local charge neutrality condition is relaxed to a global charge neutrality condition, a mixed phase appears. In the following, we

are not going to allow for such relaxation (equivalent to considering a large surface tension between the phases) to study the maximum effect the phase transition can have in binary mergers. We are also going to use a neutrino-leakage scheme to evolve the charge fraction of matter, which will allow us to go beyond the initially chemically equilibrated data.

The neutron-star-merger simulations [

20] discussed next are performed using the

Frankfurt/IllinoisGRMHD code (

FIL) [

21,

22,

23,

24] including weak-interactions via the neutrino-leakage scheme [

25,

26,

27]. The binaries are initially placed at a distance of 45 km in quasi-circular orbit and perform around five orbits before the merger. These simulations include two setups with equal-mass neutron stars with a combined total mass of

and

. For each of these systems, two identical scenarios were simulated either employing the standard CMF EOS, where quarks and a strong first-order PT are included, or a purely hadronic variant, in which the quarks are artificially suppressed.

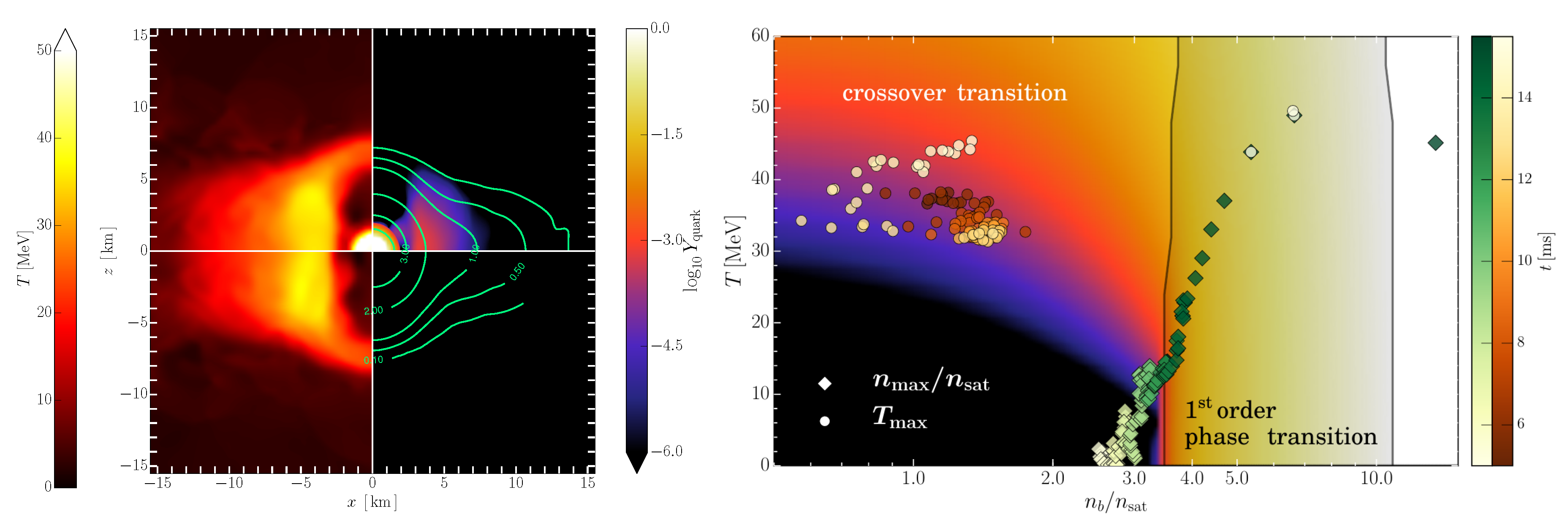

The left panel of

Figure 5 shows the meridional plane for the

M

binary

ms after the merger, when the first-order phase transition has already occurred and formed a hot and dense core inside the hypermassive neutron star. Different subpanels compare simulations performed with the CMF model allowing for quarks (top subpanels) or artificially suppressing quarks (bottom subpanels). The top subpanels show that a large quark fraction is only present in the center and outside ring, where the temperature is high. Please note that in the bottom subpanels, due to the lack of a first-order PT having taken place, there is no hot central region. This feature is a consequence of the sudden compactification generated by the very steep first-order phase transition and would have been significantly less pronounced if a mixture of phases had been included in the EOS.

The right panel of

Figure 5 shows which parts of the EOS and the QCD phase diagram are actually probed between 5 ms and 15 ms after the merger for the low-mass binary remnant. The diamonds show the evolution of the maximum baryon density, which basically probes the center of the merged object. The circles show the evolution of the maximum temperature, which probes different regions of the remnant but, eventually, coincides with the center (when circles and diamonds meet). The continued emission of GWs and, hence, the induced loss of angular momentum through GWs leads to a continuous rise of the central density, which ultimately reaches and crosses the boundary of the first-order PT (gray-shaded area).

In the right panel of

Figure 5, the background color code illustrates the relative fraction of quarks compared with the total baryonic one throughout the whole phase diagram. Although it is not shown, the first-order phase transition region will bend left at large temperatures (as indicated in the left panel of

Figure 4) but will eventually disappear reaching the crossover region. The first-order phase transition appears in the right panel of

Figure 5 as a surface because we show the phase diagram as a function of density and the reason there are points inside the region is (i) due to the way our data was slightly interpolated in that range and (2) the small but finite resolution of the dynamical time-scale of the hydrodynamical simulation. The first-order phase transition would correspond to a line if we had chosen to plot the phase diagram as a function of chemical potential instead. This and other plots will be discussed in a separate publication. Please note that as discussed in detail in Ref. [

20], the deconfinement phase transition is enough to produce a dephasing in the gravitational wave form after the merger. This is different from hyperon effects or early quark deconfinement, which should leave imprints in the waveform already before or immediately after the merger [

28,

29,

30].

4. Discussion and Outlook

Despite advances made in dense nuclear matter theory, many issues remain unresolved and/or poorly constrained with attendant uncertainties in simulations of supernovae and binary mergers of neutron stars. In this work, we explored the effects of light nuclear clusters such as d, H, He and He on the properties of the EOS at subnuclear densities. Their interactions among themselves and with nucleons were described in the EV approach. We found that the light cluster relative concentrations are mostly dependent upon the binding energy of the various species. The volume associated with each type of nucleus plays a role only at the higher density range of the subnuclear region and characterizes the population decline of the species at those densities.

We also emphasized that while the EV approach is very useful, it accounts only for repulsive interactions among nuclei and nucleons. We know that attractive interactions are present from phase-shift data and their inclusion in a calculation will certainly provide corrections to the system’s state variables. Nevertheless, we expect that these corrections are likely to be small below densities of about 0.01 fm, as indicated from a comparison with the virial approach.

Considering supranuclear densities, the CMF model represents a very useful tool to study the influence of different hyperonic and quark degrees of freedom in astrophysical scenarios. This can be seen, for example, in signatures of deconfinement phase transition predicted to exist in neutron-star mergers. Although the differences generated by quarks in this case are not large, they will be possible to resolve if detected by third-generation GW detectors [

31,

32], especially in the case that a merger takes place in a nearby system.

While the CMF approach is suitable to describe matter at supranuclear densities (in the neutron-star core), another description is needed for subnuclear densities (the crust and the very low-density regions produced in binary mergers). For the moment, we have matched the CMF EOS to the nuclear statistical equilibrium description presented in Ref. [

33], but we are soon going to connect it to the EV approach discussed in this proceeding [

5]. This complete table will be made publicly available at CompOSE.