Experimental Limiting Factors for the Search of μ → eγ at Future Facilities †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Experimental Limiting Factors

3.1.1. Efficiency

3.1.2. Photon Energy

3.1.3. Positron Energy

3.1.4. Relative Angle

3.1.5. Relative Time

3.1.6. Summary

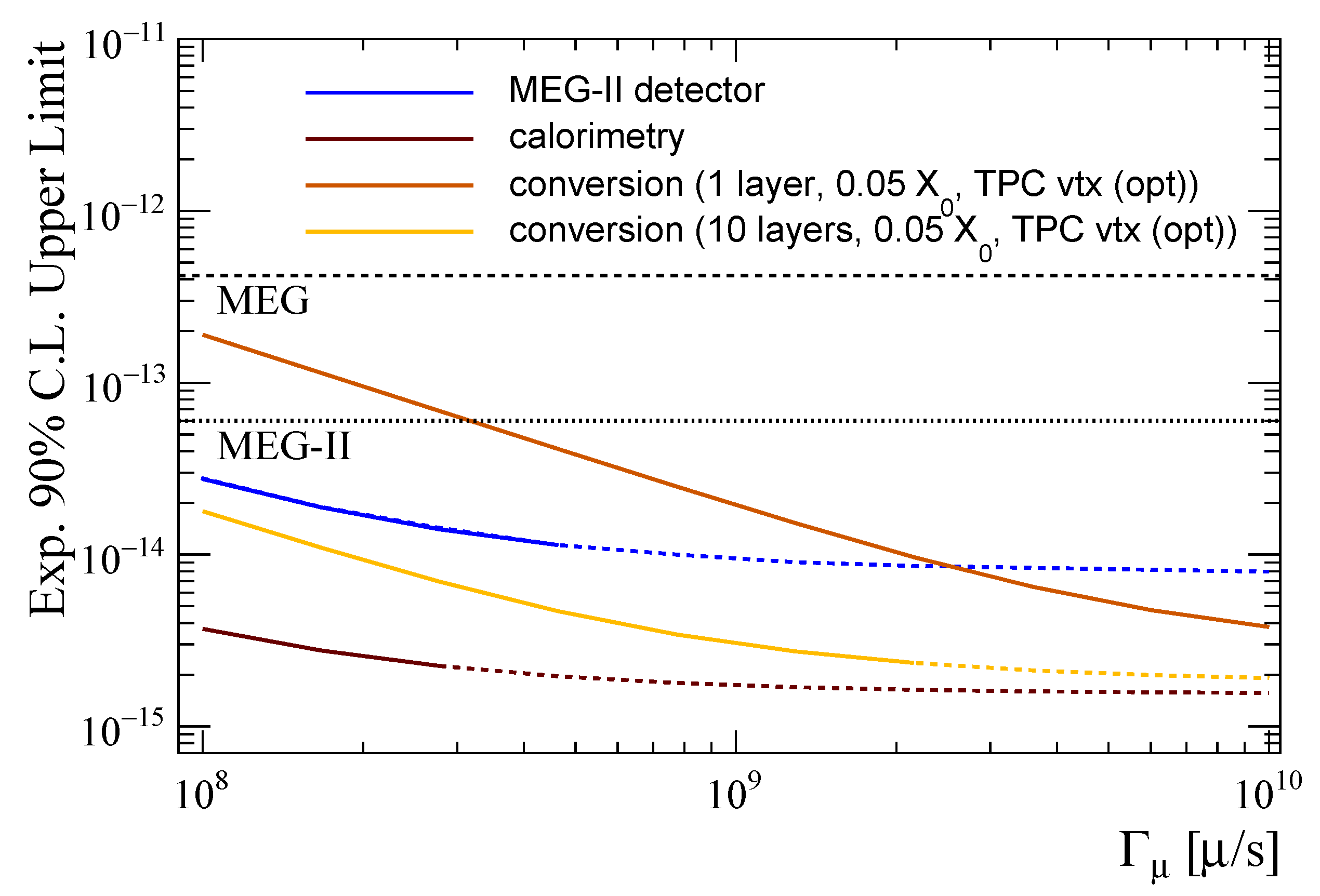

3.2. Sensitivity Reach

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baldini, A.M.; Bao, Y.; Baracchini, E.; Bemporad, C.; Berg, F.; Biasotti, M.; Boca, G.; Cattaneo, P.W.; Cavoto, G.; Cei, F.; et al. Search for the lepton flavour violating decay μ+ → e+γ with the full dataset of the MEG experiment. Eur. Phys. J. 2016, 76, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettle, P.R. HiMB: Towards a new high intensity muon beam. Available online: https://indico.cern.ch/event/356972/contributions/1766761/attachments/710281/975042/FMSW2015-Kettle.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2019).

- Cook, S.; D’Arcy, R.; Edmonds, A.; Fukuda, M.; Hatanaka, K.; Hino, Y.; Kuno, Y.; Lancaster, M.; Mori, Y.; Ogitsu, T.; et al. Delivering the world’s most intense muon beam. Phys. Rev. Accel. Beams 2017, 20, 030101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebedev, V. (Ed.) The PIP-II Reference Design Report; FERMILAB-DESIGN-2015-01; Fermilab: Batavia, IL, USA, 2015.

- Kuno, Y.; Okada, Y. Muon decay and physics beyond the standard model. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2001, 73, 151–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, R.D.; Cooper, M.D.; Frank, J.S.; Hallin, A.L.; Heusi, P.A.; Hoffman, C.M.; Hogan, G.E.; Mariam, F.G.; Matis, H.S.; Mischke, R.E.; et al. Search for Rare Muon Decays with the Crystal Box Detector. Phys. Rev. D 1988, 38, 2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, J.; Bai, X.; Baldini, A.M.; Baracchini, E.; Bemporad, C.; Boca, G.; Cattaneo, P.W.; Cavoto, G.; Cei, F.; Cerri, C.; et al. The MEG detector for μ+ → e+γ decay search. Eur. Phys. J. 2013, 73, 2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldini, A.M.; Baracchini, E.; Bemporad, C.; Berg, F.; Biasotti, M.; Boca, G.; Cattaneo, P.W.; Cavoto, G.; Cei, F.; Chiappini, M.; et al. The design of the MEG II experiment. Eur. Phys. J. 2018, 78, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, M.L.; Chen, Y.K.; Cooper, M.D.; Cooper, P.S.; Dzemidzic, M.; Empl, A.; Gagliardi, C.A.; Hogan, G.E.; Hughes, E.B.; Hungerford, E.V.; et al. New limit for the family-number non-conserving decay μ+ → e+γ. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999, 83, 1521–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostinelli, S.; Allison, J.; Amako, K.; Apostolakis, J.; Araujo, H.; Arce, P.; Asai, M.; Axen, D.; Banerjee, S.; Barrand, G.; et al. GEANT4: A Simulation toolkit. Nucl. Instrum. Methods A 2003, 506, 250–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, N.; Augustin, H.; Bachmann, S.; Kiehn, M.; Perić, I.; Perrevoort, A.-K.; Philipp, R.; Schöning, A.; Stumpf, K.; Wiedner, D.; et al. A Tracker for the Mu3e Experiment based on High-Voltage Monolithic Active Pixel Sensors. Nucl. Instrum. Methods A 2013, 732, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.H.; Echenard, B.; Hitlin, D.G. The next generation of μ− > eγ and μ− > 3e CLFV search experiments. arXiv, 2013; arXiv:1309.7679. Available online: http://inspirehep.net/record/1256023/plots?ln=en (accessed on 14 January 2019).

- Peric, I.; Augustin, H.; Backhaus, M.; Barbero, M.; Benoit, M.; Berger, N.; Bompard, F.; Breugnon, P.; Clemens, J.; Dannheim, D.; et al. High-voltage pixel detectors in commercial CMOS technologies for ATLAS, CLIC and Mu3e experiments. Nucl. Instrum. Methods A 2013, 731, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavoto, G.; Papa, A.; Renga, F.; Ripiccini, E.; Voena, C. The quest for μ → eγ and its experimental limiting factors at future high intensity muon beams. Eur. Phys. J. 2018, 78, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, G.J.; Cousins, R.D. A Unified approach to the classical statistical analysis of small signals. Phys. Rev. D 1998, 57, 3873–3889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scintillator | Density (g/cm) | Light Yield (ph/keV) | Decay Time (ns) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LaBr(Ce) | 5.08 | 63 | 16 |

| LYSO | 7.1 | 27 | 41 |

| YAP | 5.35 | 22 | 26 |

| LXe | 2.89 | 40 | 45 |

| NaI(Tl) | 3.67 | 38 | 250 |

| BGO | 7.13 | 9 | 300 |

| Typical figure | Comments | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Calorimetry | γ Conversion | ||

| Efficiency | |||

| Material budget | 0.5∼0.9 | – | magnet coil |

| Pair production | – | 0.02∼0.04 | 0.05∼0.1 |

| Minimum energies | – | 0.8 | MeV |

| Photon Energy Resolution | |||

| Energy loss | – | 250∼800 keV | 0.05∼0.1 |

| Photon Statistics & segmentation | 800 keV | – | |

| Positron Energy Resolution | |||

| Energy loss | 15 keV | ||

| Tracking & MS | 100 keV | ||

| Relative Angle Resolution | |||

| MS on target | 2.6/2.8 mrad (/) | ||

| MS on gas & walls | 3.3/3.3 mrad (/) | cm, cm, B = 1 T | |

| Tracking | 6.0/4.5 mrad (/) | ||

| Alignment | <1 mrad | <100 m target alignment | |

| Observable | One Photon Conversion Layer | Photon Calorimeter |

|---|---|---|

| [ps] | 60 | 50 |

| [keV] | 100 | 100 |

| [keV] | 320 | 850 |

| Efficiency [%] | 1.2 | 42 |

| [mrad] | [mrad] | |

|---|---|---|

| None | 7.3 | 6.2 |

| TPC | 3.5 (6.1) | 3.8 (4.8) |

| Silicon | 8.0 (6.3) | 7.4 (6.9) |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Renga, F.; Cavoto, G.; Papa, A.; Ripiccini, E.; Voena, C. Experimental Limiting Factors for the Search of μ → eγ at Future Facilities. Universe 2019, 5, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe5010027

Renga F, Cavoto G, Papa A, Ripiccini E, Voena C. Experimental Limiting Factors for the Search of μ → eγ at Future Facilities. Universe. 2019; 5(1):27. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe5010027

Chicago/Turabian StyleRenga, Francesco, Gianluca Cavoto, Angela Papa, Emanuele Ripiccini, and Cecilia Voena. 2019. "Experimental Limiting Factors for the Search of μ → eγ at Future Facilities" Universe 5, no. 1: 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe5010027

APA StyleRenga, F., Cavoto, G., Papa, A., Ripiccini, E., & Voena, C. (2019). Experimental Limiting Factors for the Search of μ → eγ at Future Facilities. Universe, 5(1), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe5010027