Abstract

The latest global analysis of neutrino oscillation data indicates that the normal neutrino mass ordering is favored over the inverted one at the level. The best-fit values of the largest neutrino mixing angle and the Dirac CP-violating phase are located in the higher octant and the third quadrant, respectively. We show that these experimental trends can be naturally explained by the - reflection symmetry breaking, triggered by the one-loop renormalization-group equations (RGEs) running from a superhigh energy scale down to the electroweak scale in the framework of the minimal supersymmetric standard model (MSSM). The complete parameter space is numerically explored for both the Majorana and Dirac cases, by allowing the smallest neutrino mass and the MSSM parameter to vary within their reasonable ranges.

1. Introduction

In the last twenty years, we have witnessed compelling evidence of the neutrino oscillation phenomena [1], as recognized by both the 2015 Nobel Prize in Physics and the 2016 Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics. The standard model (SM) of particle physics must be extended to explain the neutrino masses and the large lepton flavor mixing effects. One can describe the mixings between the three known neutrinos (, , ) and their mass eigenstates (, , ) in terms of a unitary matrix, the Pontecorvo–Maki–Nakagawa–Sakata (PMNS) matrix [2,3]:

where and (for ) with being the neutrino mixing angles, , and with and being three unphysical phases and two Majorana phases, respectively. Different from the quark sector, there are big mixing angles and a potentially large Dirac CP-violating phase in the lepton sector. On the other hand, the masses of the three known neutrinos are found to be finite, but tiny. It is popular to introduce some heavy degrees of freedom (i.e., the seesaw mechanism [4,5,6,7,8]) and certain flavor symmetries at a superhigh energy scale to explain the smallness of neutrino masses and the lepton flavor mixing patterns observed at low energies. In this case, we need to run the renormalization-group equations (RGEs) to bridge the gap between these two scales.

A credible global analysis of experimental data often points to the truth of particle physics [9,10]. The latest global analysis of available neutrino oscillation data indicates that the normal neutrino mass ordering () is favored over the inverted one () at the level [11], where (for ) stand for the neutrino masses. Moreover, the best-fit value of the atmospheric neutrino mixing angle is slightly larger than (i.e., located in the upper octant), and the best-fit value of the Dirac phase is somewhat smaller than (i.e., located in the third quadrant). The - reflection symmetry [12,13,14], the minimal discrete flavor symmetry responsible for the nearly maximal atmospheric neutrino mixing and potentially maximal CP violation in neutrino oscillations, can naturally lead to and . Assuming this symmetry is realized at a superhigh energy scale, such as the seesaw scale , it can be spontaneously broken at the electroweak scale 10 GeV because of the RGE running effect, leading to the deviations of from . Whether such quantum corrections agree with the experimental results of and at low energies depends on the neutrino mass ordering and the theoretical framework accommodating the RGEs [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. We show that the normal neutrino mass ordering, the upper-octant of , and the third-quadrant of can be naturally correlated via the RGE-induced - reflection symmetry-breaking effect in the minimal supersymmetric standard model (MSSM) framework. Based on more reliable experimental data, we numerically explore the almost complete parameter space in both the Dirac and Majorana cases by allowing the smallest neutrino mass and the MSSM parameter to vary in their reasonable regions. From the final numerical results, one can tell which part of the parameter space is favored by current neutrino oscillation data and which part is ruled out. We also conclude that the best-fit values of and [11] may be explained by the spontaneous - reflection symmetry breaking. The scenario under consideration will be tested in future neutrino oscillation experiments and help to constrain the values of the smallest neutrino mass , the MSSM parameter , and even the Majorana phases. Therefore, our in-depth analysis is timely, general, and suggestive.

2. Spontaneous - Reflection Symmetry Breaking

2.1. The Majorana Case

If neutrinos are Majorana particles, the - reflection symmetry requires the Majorana neutrino mass matrix to be invariant under charge-conjugation transformations , , and . In other words, the corresponding Majorana mass matrix elements (for and i running over ) must be constrained by , , and [14]. Taking the parametrization form of U as in Equation (1), one immediately obtains the constraints on U as follows: , or , or , and or , for the four physical parameters, as well as and for the three unphysical phases. In the framework of the MSSM, the evolution of from down to through the one-loop RGE can be expressed as: [23,24]

with , in which:

Here, , with being an arbitrary renormalization scale between and , and denoting the gauge couplings, and and (for ) standing for the Yukawa coupling eigenvalues of the top quark and charged leptons, respectively. Because of the smallness of and , one can safely take the approximation ≃ with:

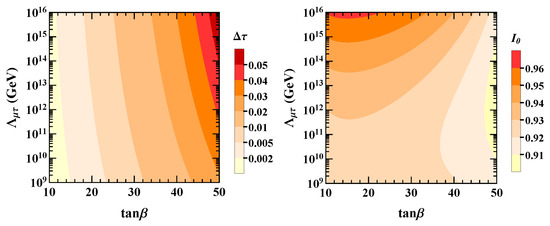

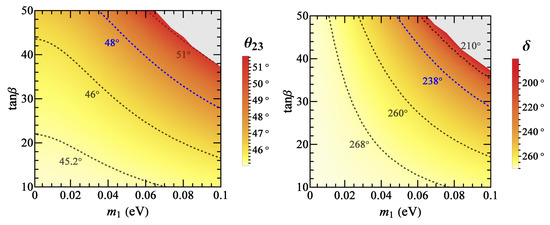

In Figure 1, we show the two-dimensional maps of (left panel) and (right panel) with respect to and . One can see that the value of does not change too much with different settings of and . In contrast, can change from –. Shifting the energy scale is equivalent to altering to obtain the same value of . In the numerical calculations, we have fixed the - symmetry scale as , with varying in a decent range, i.e, . We use and to measure the strengths of the RGE-induced - reflection symmetry-breaking effect that are relevant for oscillation experiments. They can be approximated as:

in which and take their values at , and denote the possible options of and in their - symmetry limit at , and the ratios are defined with and at (for ). In obtaining Equation (5), the - reflection symmetry conditions and have been applied. The corresponding RGE-induced corrections to the other six flavor parameters , , , , , , and have been listed in [22]. Unless otherwise specified, the parameters appearing in the subsequent text and equations are all the quantities at .

Figure 1.

Possible values of (left) and (right) with respect to and .

2.2. The Dirac Case

It is also theoretically interesting to combine a pure Dirac mass term with the - reflection symmetry for three known neutrinos [20]. In this case, is invariant under the charge-conjugation transformations , , and for the left-handed neutrino fields and , , and for the right-handed neutrino fields. Similar to the Majorana case, this leads to constraints on the mass matrix elements (for ), i.e., , , , , and . Diagonalizing this special mass matrix leads us to the following predictions: , or , and at . Under the MSSM framework, the one-loop RGE evolution of from to can be described as [20]:

where the definitions of and are the same as those in Equations (2) and (3). Using the same conventions as in the Majorana case, the deviations of and between and can be expressed as:

The expressions for deviations of , , , , , , and can be found in [22]. The analytical approximations made in Equations (5) and (7) are instructive and helpful for understanding the RGE-induced - reflection symmetry-breaking effect. However, the accuracy will be quite poor if the neutrino masses are strongly degenerate. Therefore, we have to use the numerical approach to evaluate the spontaneous - reflection symmetry-breaking effect and to explore the allowed parameter space by fitting the current experimental data.

3. Numerical Exploration

In the framework of MSSM, we input the constraints of the - reflection symmetry as initial conditions at ∼ and numerically run the RGEs from down to . To be more concrete, the initial conditions include and , as well as four different cases of and for Majorana neutrinos: Case A: ; Case B: ; Case C: and ; Case D: and . For any given values of the MSSM parameter and the smallest neutrino mass at , we scan the other relevant neutrino oscillation parameters like at over properly wide ranges by utilizing the MultiNest program [25,26,27]. The conventions and have been adopted to keep consistent with the definitions in [11]. For each scan, the neutrino mixing parameters at are yielded and then compared with their global-fit values by minimizing:

Here, stand for the parameters at , which are produced by the RGE running from ; ’s represent the best-fit values of in the global analysis; and ’s are the corresponding symmetrized errors. We take the best-fit values and the errors of the six neutrino oscillation parameters in [11]: , , , , , . The smallest neutrino mass is allowed to take values over the range , and the MSSM parameter may vary from 10–50. With this setup, we examine how significantly and at can deviate from their initial values at by incorporating the recent global-fit results [11].

3.1. The Majorana Case

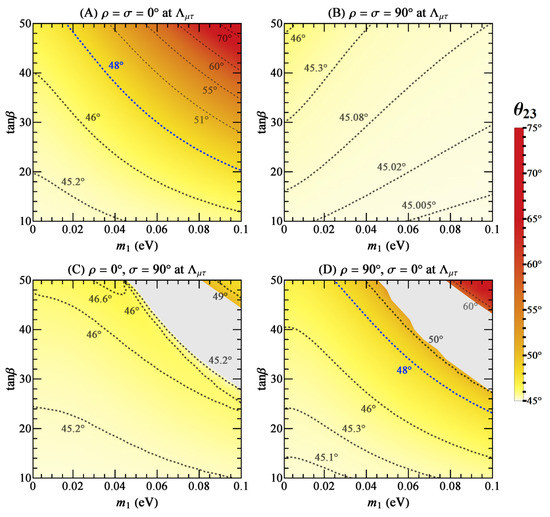

In Figure 2 and Figure 3, we plot the allowed values of and at by taking different values of and with . Four different cases of the initial Majorana phases at have been considered. For each point in the - plane, and are determined simultaneously. The boundary conditions for the RGEs include both the initial values of at and the experimental constraints on at . In this case, the RGEs may not have a realistic solution for some combinations of and ; the gray-gap regions in Figure 2 and Figure 3 (Cases C and D) are excluded. There is no such gap in Cases A and B with different initial values of and . The RGE running effect always pushes to the higher octant and, in most cases, leads to the third quadrant, just the right direction as indicated by the best-fit values of these two quantities [11]. In Case A and Case D, may be significantly corrected for ≃ and ≃50. Of course, such an evolution will be strongly disfavored by the experimental information of , which has not been included for this analysis. Our main purpose is to show the general magnitudes of RGE corrections to and , without directly involving the experimental limits on them. In Case B, is not sensitive to the RGE running. The RGE-induced corrections to in Cases A and B are very weak. We highlight Case D, in which the best-fit point ≃ is reachable for the same settings of and .

Figure 2.

The values of at due to the spontaneous - reflection symmetry-breaking effect, where the dashed curves are the contours with some typical values of and the blue ones agree with the best-fit result of in [11].

Figure 3.

The values of at due to the spontaneous - reflection symmetry-breaking effect, where the dashed curves are the contours with some typical values of and the blue ones agree with the best-fit result of in [11].

The RGE corrections to and in Figure 2 and Figure 3 can be understood with the help of the analytical expressions in Equation (5), if the neutrino masses are not so degenerate. The factor is essentially proportional to as a result of ≃ for , and the magnitudes of and always increase with . Because the factors and ≃ are all positive for the normal mass ordering, the sign of is always positive. The dependence of and on the neutrino mass is different for the four options of and at . In the region of small and , the radiative correction to is proportional to for Cases A, C, and D, but it is inversely proportional to in Case B with . As for , its value depends on two terms: one is enhanced by ; and the other is suppressed by . However, the latter one can become dominant in some cases. For example, in Case A, the first term is positive and dominant when the neutrino mass is relatively small, while the second term is negative and will gradually dominate when the value of increases.

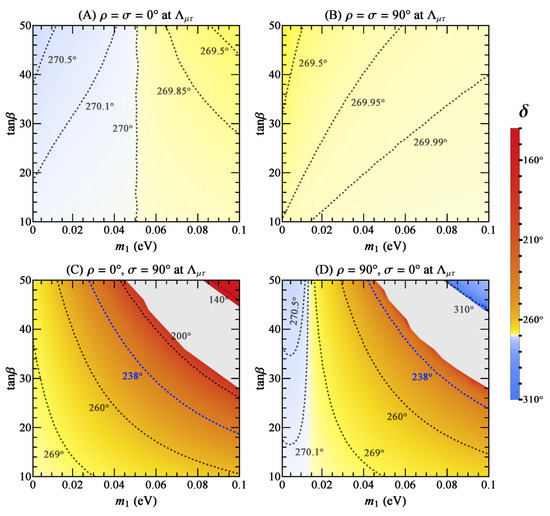

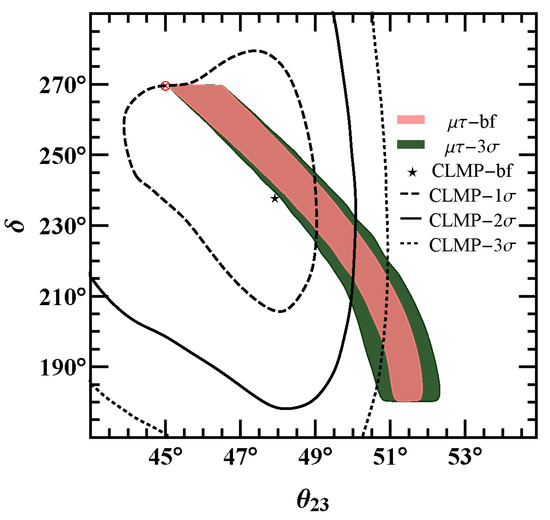

To see the correlation between and at , we marginalize and over the reasonable ranges and and show the results in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The correlation between and at compared with the global-fit results (represented with “CLMP”) [11], where and are marginalized over and , respectively. The red circled cross ⊗ signifies the point . The pink regions are allowed for and when at all take their best-fit values. The green region is allowed when these four observables are relaxed from their best-fit values to their ranges.

The recent global-fit results [11] are given as the black contours for the (dashed), (solid), and (dotted) confidence levels. The best-fit point of the global analysis is marked as the black star. We notice that the - reflection symmetry point at , which is marked as the red circled cross in the plot, is on the dashed contour. This means that and are statistically disfavored at the level [11]. For the pink regions, the best-fit values of can be simultaneously reached (i.e., ). If the value of is relaxed to (i.e., the confidence level for two degrees of freedom), the wider green regions of and will be allowed. In the two upper panels of Figure 4, which correspond to Cases A (left one) and B (right one), the allowed range of is very narrow; this feature is compatible with the two upper panels of Figure 3 where varies less than . In these two cases, the green region almost overlaps with the pink region. In the two lower panels of Figure 4, corresponding to Cases C (left one) and D (right one), the RGE-induced corrections of and are both significant. The separate shaded region around in Figure 4C is associated with the small upper-right corner of the parameter space in Figure 2C or Figure 3C. There is a similar separate shaded region in Case D, but it is outside the chosen ranges of and in plotting Figure 4D, and its confidence level is much weaker, outside the region in the global analysis.

3.2. The Dirac Case

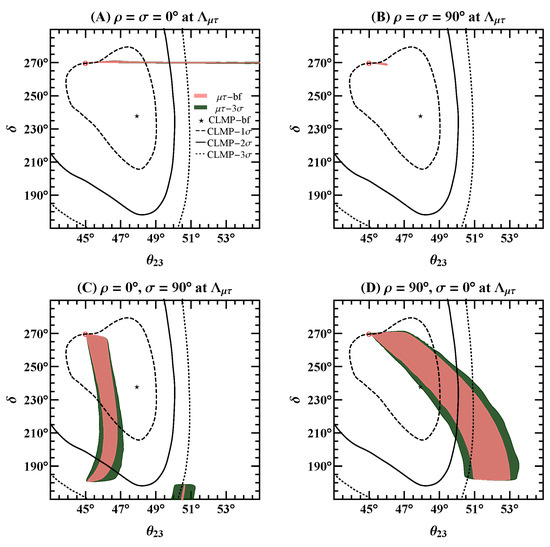

The corresponding numerical analysis for the Dirac neutrinos is much easier due to the absence of two Majorana phases. Similar to the Majorana case, the allowed regions of and at and their intimate correlation are illustrated in Figure 5 and Figure 6. The analytical approximations of and in Equation (7) can be further simplified to:

Figure 5.

For the Dirac case, the allowed values of (left) panel and (right) panel at are owed to the spontaneous - reflection symmetry-breaking effect. The dashed curves are the contours with some typical values of and , and the blue ones stand for the best-fit result of or in [11].

Figure 6.

The correlation of at for the Dirac case. The conventions are the same as Figure 4.

It is easy to see that bigger values of and lead to larger deviations of from . In particular, and are always located in the upper octant and the third quadrant, respectively. In Figure 5, we have the gray regions for the same reason as that in the Majorana case. Similar to Case D in the Majorana case, the spontaneous - reflection symmetry breaking can take very close to their best-fit point in the global analysis.

4. Conclusions

The - reflection symmetry is inclusive to explain the nearly maximal atmospheric neutrino mixing and the potentially maximal CP violation in neutrino oscillations. However, the latest global analysis suggests this symmetry should be broken at the low energy experimental scale. The RGE running effect can be responsible for the symmetry breaking. The normal neutrino mass ordering, the upper-octant of , and the third-quadrant of can be naturally correlated with the RGEs running effect in the MSSM framework. Some of our main observations are subject to the chosen theoretical framework, i.e., the MSSM. The reasons why we do not consider the standard model is: (a) in the SM, the RGE running effect is always very small; (b) in the SM, the running direction of from down to is opposite its current best-fit result in the normal mass ordering case; and (c) there may be the vacuum-stability problem as the energy scale is above GeV [28,29] in the SM. On the other hand, the best-fit values of and will unavoidably fluctuate in the future when more experimental data are accumulated and included in the global analysis. Since we have generally explored the complete parameter space, our results still keep working. If the future precision measurements favor the inverted neutrino mass ordering, the lower octant of , and (or) another quadrant of , one can perform the numerical analysis in the same way, either within or beyond the MSSM. In the same spirit, one may study other interesting flavor symmetries and their RGE-induced breaking effect, in order to link model building at high-energy scales effectively with the observed neutrino oscillation data at low energies.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this paper.

Funding

This research work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 11775231 and Grant No. 11775232.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the organizers of the 7th International Conference on New Frontiers in Physics (ICNFP 2018), where this work was reported.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tanabashi, M.; Particle Data Group; et al. Review of Particle Physics. Phys. Rev. D 2018, 98, 030001. [Google Scholar]

- Maki, Z.; Nakagawa, M.; Sakata, S. Remarks on the unified model of elementary particles. Prog. Theor. Phys. 1962, 28, 870–880. [Google Scholar]

- Pontecorvo, B. Neutrino Experiments and the Problem of Conservation of Leptonic Charge. Sov. Phys. JETP 1968, 26, 984–988. [Google Scholar]

- Minkowski, P. μ → eγ at a Rate of One Out of 109 Muon Decays? Phys. Lett. B 1977, 67, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagida, T. Horizontal Symmetry And Masses Of Neutrinos. In Proceedings of the Workshop on the Unified Theories and the Baryon Number in the Universe, Tsukuba, Japan, 13–14 February 1979; Sawada, O., Sugamoto, A., Eds.; National Laboratory for High Energy Physics: Tsukuba, Japan, 1979; p. 95. [Google Scholar]

- Gell-Mann, M.; Ramond, P.; Slansky, R. Complex Spinors and Unified Theories. In Supergravity; van Nieuwenhuizen, P., Freedman, D., Eds.; North Holland Publishing Co.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1979; p. 315. [Google Scholar]

- Glashow, S.L. The Future of Elementary Particle Physics. In Quarks and Leptons; Lévy, M., Basdevant, J.L., Speiser, D., Weyers, J., Gastmans, R., Jacob, M., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1980; p. 687. [Google Scholar]

- Mohapatra, R.N.; Senjanovic, G. Neutrino Mass and Spontaneous Parity Violation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1980, 44, 912. [Google Scholar]

- Fogli, G.L.; Lisi, E.; Marrone, A.; Palazzo, A.; Rotunno, A.M. Hints of θ13 > 0 from global neutrino data analysis. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 101, 141801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, F.P.; Bai, J.Z.; Balantekin, A.B.; Band, H.R.; Beavis, D.; Beriguete, W.; Bishai, M.; Blyth, S.; Boddy, K.; Brown, R.L.; et al. Observation of electron-antineutrino disappearance at Daya Bay. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 171803. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Capozzi, F.; Lisi, E.; Marrone, A.; Palazzo, A. Current unknowns in the three neutrino framework. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 2018, 102, 48–72. [Google Scholar]

- Babu, K.S.; Ma, E.; Valle, J.W.F. Underlying A(4) symmetry for the neutrino mass matrix and the quark mixing matrix. Phys. Lett. B 2003, 552, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, P.F.; Scott, W.G. μ-τ reflection symmetry in lepton mixing and neutrino oscillations. Phys. Lett. B 2002, 547, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.Z.; Zhao, Z.H. A review of μ-τ flavor symmetry in neutrino physics. Rept. Prog. Phys. 2016, 79, 076201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, S.; Xing, Z.Z. Resolving the octant of θ23 via radiative μ-τ symmetry breaking. Phys. Rev. D 2014, 90, 073005. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.L. μ-τ reflection symmetry and radiative corrections. arXiv, 2014; arXiv:1409.8600. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.H. Breakings of the neutrino μ-τ reflection symmetry. J. High Energy Phys. 2017, 2017, 023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodejohann, W.; Xu, X.J. Trimaximal μ-τ reflection symmetry. Phys. Rev. D 2017, 96, 055039. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.C.; Yue, C.X.; Zhao, Z.H. Neutrino μ-τ reflection symmetry and its breaking in the minimal seesaw. J. High Energy Phys. 2017, 2017, 102. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, Z.Z.; Zhang, D.; Zhu, J.Y. The μ-τ reflection symmetry of Dirac neutrinos and its breaking effect via quantum corrections. J. High Energy Phys. 2017, 2017, 135. [Google Scholar]

- Nath, N.; Xing, Z.Z.; Zhang, J. μ-τ Reflection Symmetry Embedded in Minimal Seesaw. Eur. Phys. J. C 2018, 78, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.Y.; Xing, Z.Z.; Zhu, J.Y. Correlation of normal neutrino mass ordering with upper octant of θ23 and third quadrant of δ via spontaneous μ-τ symmetry breaking. arXiv, 2018; arXiv:1806.06640. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, J.R.; Lola, S. Can neutrinos be degenerate in mass? Phys. Lett. B 1999, 458, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritzsch, H.; Xing, Z.Z. Mass and flavor mixing schemes of quarks and leptons. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 2000, 45, 1–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feroz, F.; Hobson, M.P. Multimodal nested sampling: An efficient and robust alternative to MCMC methods for astronomical data analysis. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2008, 384, 449–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feroz, F.; Hobson, M.P.; Bridges, M. MultiNest: An efficient and robust Bayesian inference tool for cosmology and particle physics. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2009, 398, 1601–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feroz, F.; Hobson, M.P.; Cameron, E.; Pettitt, A.N. Importance Nested Sampling and the MultiNest Algorithm. arXiv, 2013; arXiv:1306.2144. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, Z.Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, S. Impacts of the Higgs mass on vacuum stability, running fermion masses and two-body Higgs decays. Phys. Rev. D 2012, 86, 013013. [Google Scholar]

- Elias-Miro, J.; Espinosa, J.R.; Giudice, G.F.; Isidori, G.; Riotto, A.; Strumia, A. Higgs mass implications on the stability of the electroweak vacuum. Phys. Lett. B 2012, 709, 222–228. [Google Scholar]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).