A Case Study of a Companion Galaxy Outshining Its AGN Neighbour in a Distant Merger System

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Observations

2.2. Data Imaging

2.3. SED Fitting

3. Results

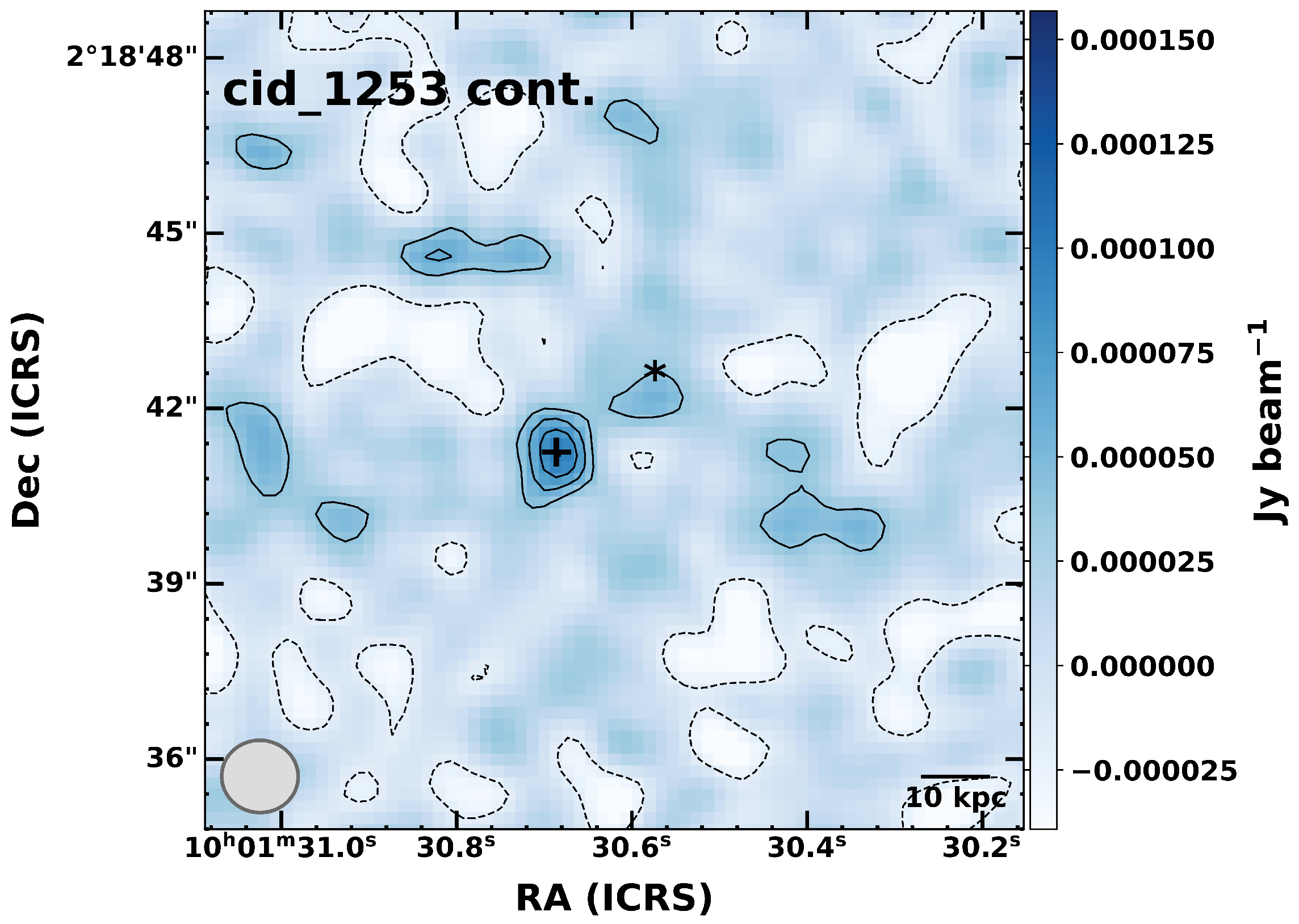

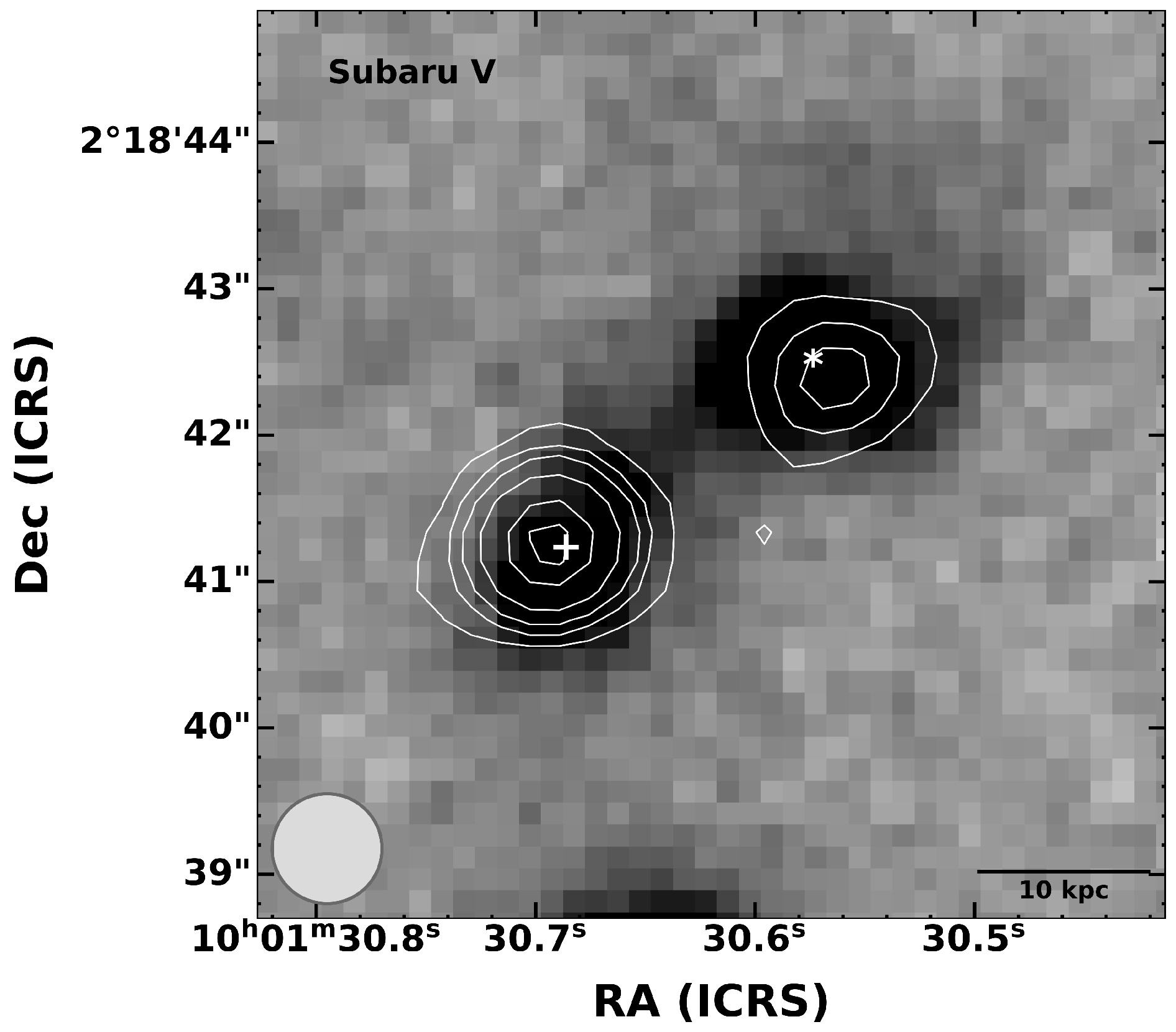

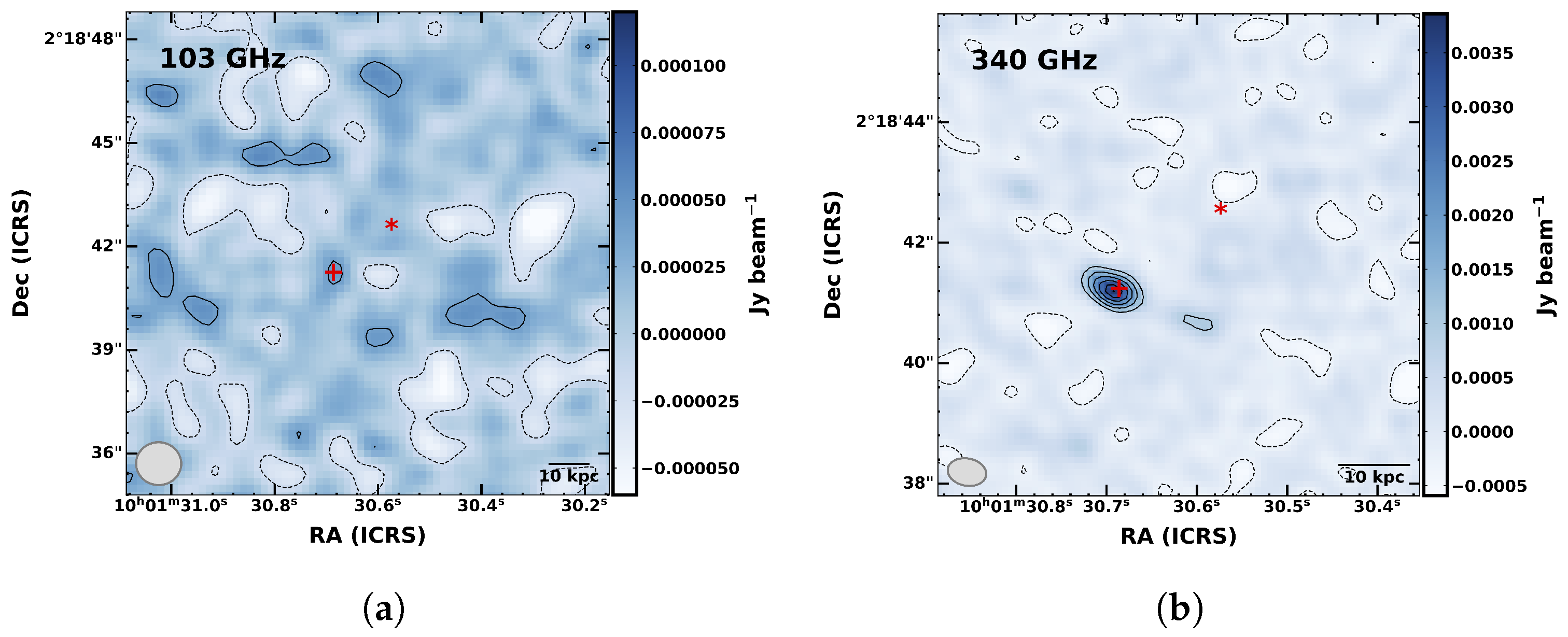

3.1. Continuum Emission

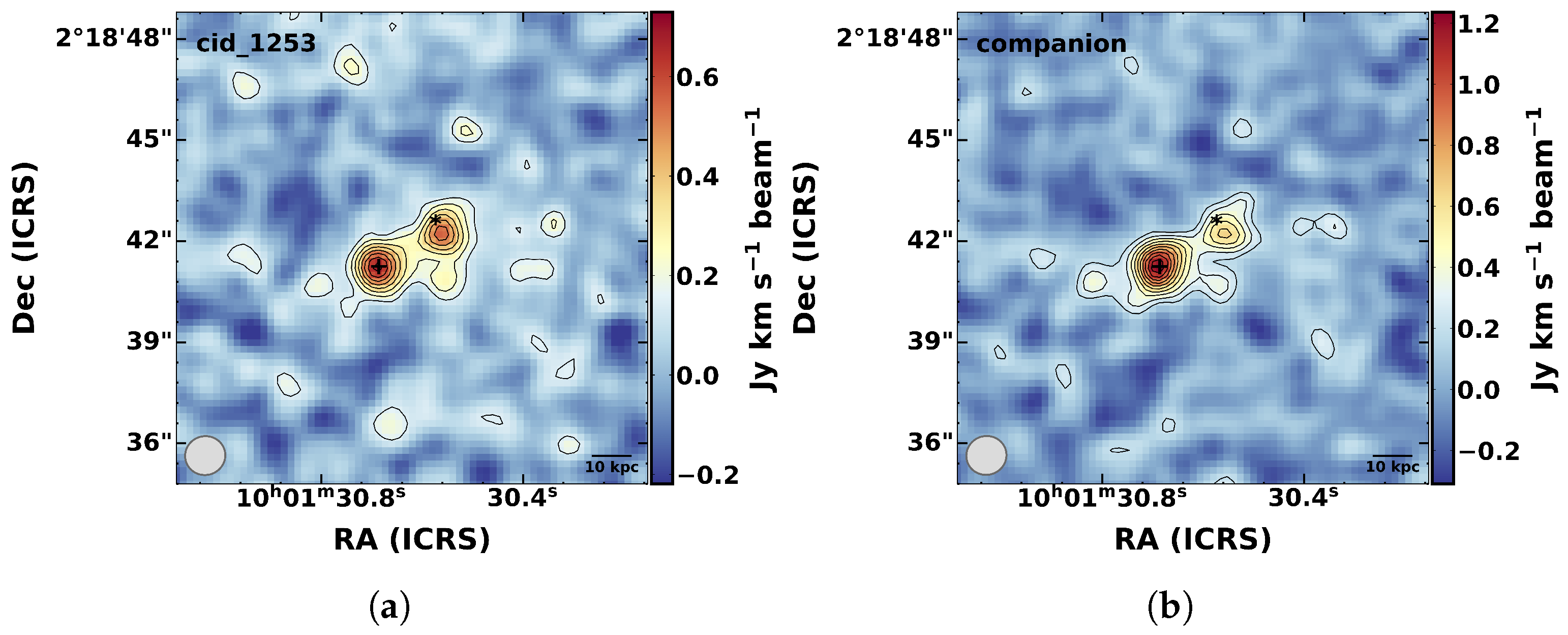

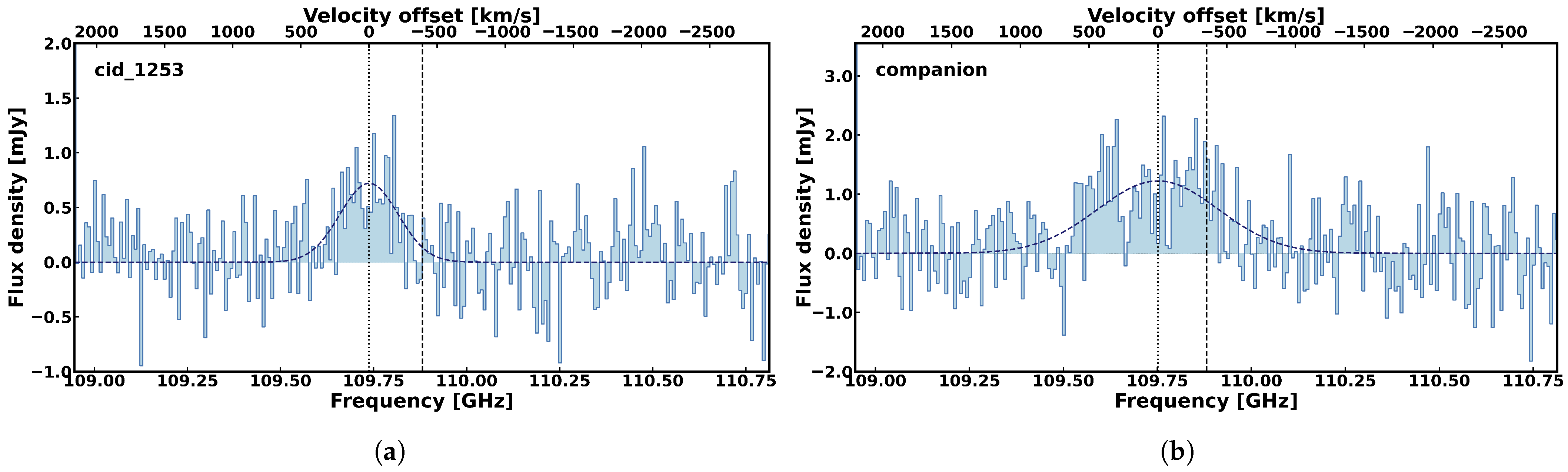

3.2. CO(3–2) Line Emission

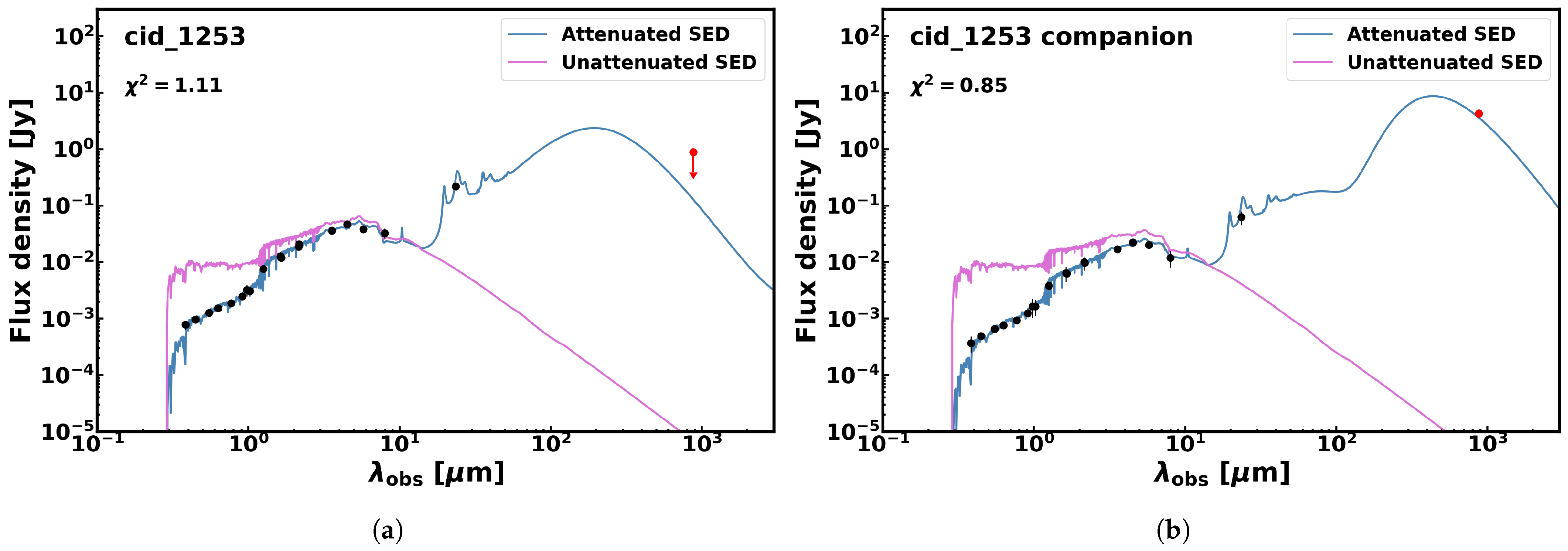

3.3. SED Fitting Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Molecular Gas Mass of the System

4.2. Dust Emission and Star Formation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGN | active galactic nucleus |

| ALMA | Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array |

| CASA | Common Astronomy Software Applications |

| FIR | far-infrared |

| FWHM | full width at half maximum |

| SED | spectral energy distribution |

| SFR | star formation rate |

| SPW | spectral window |

| SUBMM | submillimetre |

| VLA | Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array |

Appendix A. Multi-Wavelength Photometry of cid_1253 and Its Companion Galaxy

| cid_1253 | COSMOS2015 666121 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filter Name | AB Magnitude | Flux Density () 1 | AB Magnitude | Flux Density () 1 |

| CFHT/Megacam u | ||||

| Subaru/Suprime B | ||||

| Subaru/Suprime V | ||||

| Subaru/Suprime r | ||||

| Subaru/Suprime | ||||

| HSC/Subaru Y | ||||

| VISTA Y | ||||

| VISTA J | ||||

| CFHT/WIRCAM H | ||||

| VISTA H | ||||

| VISTA | ||||

| CFHT/WIRCAM | ||||

| Spitzer/IRAC | ||||

| Spitzer/IRAC | ||||

| Spitzer/IRAC | ||||

| Spitzer/IRAC | ||||

| Spitzer/MIPS | − | − | ||

| ALMA | − | <891 2 | − | |

Appendix B. Line Contamination to the Band 3 Continuum

References

- Fabian, A.C. Observational Evidence of Active Galactic Nuclei Feedback. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 2012, 50, 455–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, C.M.; Costa, T.; Tadhunter, C.N.; Flütsch, A.; Kakkad, D.; Perna, M.; Vietri, G. AGN outflows and feedback twenty years on. Nat. Astron. 2018, 2, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, C.M.; Ramos Almeida, C. Observational Tests of Active Galactic Nuclei Feedback: An Overview of Approaches and Interpretation. Galaxies 2024, 12, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glikman, E.; Simmons, B.; Mailly, M.; Schawinski, K.; Urry, C.M.; Lacy, M. Major Mergers Host the Most-luminous Red Quasars at z ~ 2: A Hubble Space Telescope WFC3/IR Study. Astrophys. J. 2015, 806, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, J.; Torrey, P.; Ellison, S.L.; Patton, D.R.; Hopkins, P.F.; Bueno, M.; Hayward, C.C.; Narayanan, D.; Kereš, D.; Bluck, A.F.L.; et al. Interacting galaxies on FIRE-2: The connection between enhanced star formation and interstellar gas content. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2019, 485, 1320–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparre, M.; Whittingham, J.; Damle, M.; Hani, M.H.; Richter, P.; Ellison, S.L.; Pfrommer, C.; Vogelsberger, M. Gas flows in galaxy mergers: Supersonic turbulence in bridges, accretion from the circumgalactic medium, and metallicity dilution. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2022, 509, 2720–2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacey, H.R.; Arrigoni Battaia, F. Luck of the Irish? A companion of the Cloverleaf connected by a bridge of molecular gas. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2022, 517, L11–L15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiding, P.; Chiaberge, M.; Lambrides, E.; Meyer, E.T.; Willner, S.P.; Hilbert, B.; Haas, M.; Miley, G.; Perlman, E.S.; Barthel, P.; et al. Powerful Radio-loud Quasars Are Triggered by Galaxy Mergers in the Cosmic Bright Ages. Astrophys. J. 2024, 963, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comerford, J.M.; Nevin, R.; Negus, J.; Barrows, R.S.; Eracleous, M.; Müller-Sánchez, F.; Roy, N.; Stemo, A.; Storchi-Bergmann, T.; Wylezalek, D. An Excess of Active Galactic Nuclei Triggered by Galaxy Mergers in MaNGA Galaxies of Stellar Mass ∼1011 M ⊙. Astrophys. J. 2024, 963, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; De Breuck, C.; Wylezalek, D.; Lehnert, M.D.; Faisst, A.L.; Vayner, A.; Nesvadba, N.; Vernet, J.; Kukreti, P.; Stern, D. Gas-poor Hosts and Gas-rich Companions of z ≈ 3.5 Radio Active Galactic Nuclei: ALMA Insights into Jet Triggering and Feedback. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2025, 987, L37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molyneux, S.J.; Calistro Rivera, G.; De Breuck, C.; Harrison, C.M.; Mainieri, V.; Lundgren, A.; Kakkad, D.; Circosta, C.; Girdhar, A.; Costa, T.; et al. The Quasar Feedback Survey: Characterizing CO excitation in quasar host galaxies. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2024, 527, 4420–4439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Wang, R.; Li, J.; Neri, R.; Pensabene, A.; Decarli, R.; Shao, Y.; Bañados, E.; Cox, P.; Bertoldi, F.; et al. Constraining the Excitation of Molecular Gas in Two Quasar-starburst Systems at z ∼ 6. Astrophys. J. 2024, 977, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audibert, A.; Ramos Almeida, C.; García-Burillo, S.; Speranza, G.; Lamperti, I.; Pereira-Santaella, M.; Panessa, F. Molecular gas excitation and outflow properties of obscured quasars at z ∼ 0.1. Astron. Astrophys. 2025, 699, A83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischetti, M.; Feruglio, C.; Piconcelli, E.; Duras, F.; Pérez-Torres, M.; Herrero, R.; Venturi, G.; Carniani, S.; Bruni, G.; Gavignaud, I.; et al. The WISSH quasars project. IX. Cold gas content and environment of luminous QSOs at z ∼ 2.4–4.7. Astron. Astrophys. 2021, 645, A33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossati, M.; Fumagalli, M.; Lofthouse, E.K.; Dutta, R.; Cantalupo, S.; Arrigoni Battaia, F.; Fynbo, J.P.U.; Lusso, E.; Murphy, M.T.; Prochaska, J.X.; et al. MUSE analysis of gas around galaxies (MAGG)—III. The gas and galaxy environment of z = 3–4.5 quasars. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2021, 503, 3044–3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogasy, J.; Knudsen, K.K.; Varenius, E. VLA detects CO(1-0) emission in the z = 3.65 quasar SDSS J160705+533558. Astron. Astrophys. 2022, 660, A60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Vergara, C.; Rybak, M.; Hodge, J.; Hennawi, J.F.; Decarli, R.; González-López, J.; Arrigoni-Battaia, F.; Aravena, M.; Farina, E.P. ALMA Reveals a Large Overdensity and Strong Clustering of Galaxies in Quasar Environments at z ~ 4. Astrophys. J. 2022, 927, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentealba-Fuentes, M.; Lira, P.; Díaz-Santos, T.; Trakhtenbrot, B.; Netzer, H.; Videla, L. Study of the ∼50 kpc circumgalactic environment around the merger system J2057-0030 at z ∼ 4.6 using ALMA. Astron. Astrophys. 2024, 687, A62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.Y.; Dai, Y.S.; Omont, A.; Liu, D.; Cox, P.; Neri, R.; Krips, M.; Yang, C.; Wu, X.B.; Huang, J.S. Dust and Cold Gas Properties of Starburst HyLIRG Quasars at z ∼ 2.5. Astrophys. J. 2024, 964, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pensabene, A.; Cantalupo, S.; Cicone, C.; Decarli, R.; Galbiati, M.; Ginolfi, M.; de Beer, S.; Fossati, M.; Fumagalli, M.; Lazeyras, T.; et al. ALMA survey of a massive node of the Cosmic Web at z ∼ 3. I. Discovery of a large overdensity of CO emitters. Astron. Astrophys. 2024, 684, A119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatziminaoglou, E.; Messias, H.; Souza, R.; Borkar, A.; Farrah, D.; Feltre, A.; Magdis, G.; Pitchford, L.K.; Pérez-Fournon, I. An ALMA Band 7 survey of SDSS/Herschel quasars in Stripe 82: I. The properties of the 870 micron counterparts. Astron. Astrophys. 2025, 702, A183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; De Breuck, C.; Wylezalek, D.; Vernet, J.; Lehnert, M.D.; Stern, D.; Rupke, D.S.N.; Nesvadba, N.P.H.; Vayner, A.; Zakamska, N.L.; et al. JWST + ALMA ubiquitously discover companion systems within ≲18 kpc around four z ≈ 3.5 luminous radio-loud AGN. Astron. Astrophys. 2025, 696, A88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laigle, C.; McCracken, H.J.; Ilbert, O.; Hsieh, B.C.; Davidzon, I.; Capak, P.; Hasinger, G.; Silverman, J.D.; Pichon, C.; Coupon, J.; et al. The COSMOS2015 Catalog: Exploring the 1 < z < 6 Universe with Half a Million Galaxies. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 2016, 224, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchesi, S.; Civano, F.; Elvis, M.; Salvato, M.; Brusa, M.; Comastri, A.; Gilli, R.; Hasinger, G.; Lanzuisi, G.; Miyaji, T.; et al. The Chandra COSMOS Legacy survey: Optical/IR identifications. Astrophys. J. 2016, 817, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elvis, M.; Civano, F.; Vignali, C.; Puccetti, S.; Fiore, F.; Cappelluti, N.; Aldcroft, T.L.; Fruscione, A.; Zamorani, G.; Comastri, A.; et al. The Chandra COSMOS Survey. I. Overview and Point Source Catalog. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 2009, 184, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civano, F.; Marchesi, S.; Comastri, A.; Urry, M.C.; Elvis, M.; Cappelluti, N.; Puccetti, S.; Brusa, M.; Zamorani, G.; Hasinger, G.; et al. The Chandra Cosmos Legacy Survey: Overview and Point Source Catalog. Astrophys. J. 2016, 819, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schinnerer, E.; Sargent, M.T.; Bondi, M.; Smolčić, V.; Datta, A.; Carilli, C.L.; Bertoldi, F.; Blain, A.; Ciliegi, P.; Koekemoer, A.; et al. The VLA-COSMOS Survey. IV. Deep Data and Joint Catalog. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 2010, 188, 384–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolčić, V.; Novak, M.; Bondi, M.; Ciliegi, P.; Mooley, K.P.; Schinnerer, E.; Zamorani, G.; Navarrete, F.; Bourke, S.; Karim, A.; et al. The VLA-COSMOS 3 GHz Large Project: Continuum data and source catalog release. Astron. Astrophys. 2017, 602, A1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Circosta, C.; Mainieri, V.; Lamperti, I.; Padovani, P.; Bischetti, M.; Harrison, C.M.; Kakkad, D.; Zanella, A.; Vietri, G.; Lanzuisi, G.; et al. SUPER. IV. CO(J = 3-2) properties of active galactic nucleus hosts at cosmic noon revealed by ALMA. Astron. Astrophys. 2021, 646, A96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Lang, P.; Magnelli, B.; Schinnerer, E.; Leslie, S.; Fudamoto, Y.; Bondi, M.; Groves, B.; Jiménez-Andrade, E.; Harrington, K.; et al. Automated Mining of the ALMA Archive in the COSMOS Field (A3COSMOS). I. Robust ALMA Continuum Photometry Catalogs and Stellar Mass and Star Formation Properties for ∼700 Galaxies at z = 0.5–6. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 2019, 244, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMullin, J.P.; Waters, B.; Schiebel, D.; Young, W.; Golap, K. CASA Architecture and Applications. In Astronomical Data Analysis Software and Systems XVI, Proceedings of the 16th Annual Conference on Astronomical Data Analysis Software and Systems (ADASS XVI), Tucson, AZ, USA, 15–18 October 2007; Shaw, R.A., Hill, F., Bell, D.J., Eds.; Astronomical Society of the Pacific Conference Series; Astronomical Society of the Pacific: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2007; Volume 376, p. 127. [Google Scholar]

- da Cunha, E.; Charlot, S.; Elbaz, D. A simple model to interpret the ultraviolet, optical and infrared emission from galaxies. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2008, 388, 1595–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Cunha, E.; Walter, F.; Smail, I.R.; Swinbank, A.M.; Simpson, J.M.; Decarli, R.; Hodge, J.A.; Weiss, A.; van der Werf, P.P.; Bertoldi, F.; et al. An ALMA Survey of Sub-millimeter Galaxies in the Extended Chandra Deep Field South: Physical Properties Derived from Ultraviolet-to-radio Modeling. Astrophys. J. 2015, 806, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruzual, G.; Charlot, S. Stellar population synthesis at the resolution of 2003. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2003, 344, 1000–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlot, S.; Fall, S.M. A Simple Model for the Absorption of Starlight by Dust in Galaxies. Astrophys. J. 2000, 539, 718–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Daddi, E.; Liu, D.; Smolčić, V.; Schinnerer, E.; Calabrò, A.; Gu, Q.; Delhaize, J.; Delvecchio, I.; Gao, Y.; et al. “Super-deblended” Dust Emission in Galaxies. II. Far-IR to (Sub)millimeter Photometry and High-redshift Galaxy Candidates in the Full COSMOS Field. Astrophys. J. 2018, 864, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padovani, P.; Alexander, D.M.; Assef, R.J.; De Marco, B.; Giommi, P.; Hickox, R.C.; Richards, G.T.; Smolčić, V.; Hatziminaoglou, E.; Mainieri, V.; et al. Active galactic nuclei: What’s in a name? Astron. Astrophys. Rev. 2017, 25, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comrie, A.; Wang, K.S.; Hwang, Y.H.; Pińska, A.; Harris, P.; Raul-Omar, C.; Hou, K.C.; Aikema, D.; Chiang, C.C.; Ming-Yi, L.; et al. CARTA: The Cube Analysis and Rendering Tool for Astronomy. Zenodo 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Circosta, C.; Mainieri, V.; Padovani, P.; Lanzuisi, G.; Salvato, M.; Harrison, C.M.; Kakkad, D.; Puglisi, A.; Vietri, G.; Zamorani, G.; et al. SUPER. I. Toward an unbiased study of ionized outflows in z ∼ 2 active galactic nuclei: Survey overview and sample characterization. Astron. Astrophys. 2018, 620, A82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, P.M.; Vanden Bout, P.A. Molecular Gas at High Redshift. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 2005, 43, 677–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daddi, E.; Bournaud, F.; Walter, F.; Dannerbauer, H.; Carilli, C.L.; Dickinson, M.; Elbaz, D.; Morrison, G.E.; Riechers, D.; Onodera, M.; et al. Very High Gas Fractions and Extended Gas Reservoirs in z = 1.5 Disk Galaxies. Astrophys. J. 2010, 713, 686–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakkad, D.; Mainieri, V.; Brusa, M.; Padovani, P.; Carniani, S.; Feruglio, C.; Sargent, M.; Husemann, B.; Bongiorno, A.; Bonzini, M.; et al. ALMA observations of cold molecular gas in AGN hosts at z ∼ 1.5—Evidence of AGN feedback? Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2017, 468, 4205–4215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravena, M.; Decarli, R.; Gónzalez-López, J.; Boogaard, L.; Walter, F.; Carilli, C.; Popping, G.; Weiss, A.; Assef, R.J.; Bacon, R.; et al. The ALMA Spectroscopic Survey in the Hubble Ultra Deep Field: Evolution of the Molecular Gas in CO-selected Galaxies. Astrophys. J. 2019, 882, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassata, P.; Liu, D.; Groves, B.; Schinnerer, E.; Ibar, E.; Sargent, M.; Karim, A.; Talia, M.; Fèvre, O.L.; Tasca, L.; et al. ALMA Reveals the Molecular Gas Properties of Five Star-forming Galaxies across the Main Sequence at 3. Astrophys. J. 2020, 891, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Emonts, B.H.C.; Cai, Z.; Li, J.; Battaia, F.A.; Prochaska, J.X.; Yoon, I.; Lehnert, M.D.; Sarazin, C.; Wu, Y.; et al. The SUPERCOLD-CGM Survey. I. Probing the Extended CO(4-3) Emission of the Circumgalactic Medium in a Sample of 10 Enormous Lyα Nebulae at z ∼ 2. Astrophys. J. 2023, 950, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carilli, C.L.; Walter, F. Cool Gas in High-Redshift Galaxies. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 2013, 51, 105–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riechers, D.A. SMM J04135+10277: A Candidate Early-stage “Wet-Dry” Merger of Two Massive Galaxies at z = 2.8. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2013, 765, L31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogasy, J.; Knudsen, K.K.; Drouart, G.; Lagos, C.D.P.; Fan, L. SMM J04135+10277: A distant QSO-starburst system caught by ALMA. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2020, 493, 3744–3756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Kohno, K.; Hatsukade, B.; Egusa, F.; Yamashita, T.; Schramm, M.; Ichikawa, K.; Imanishi, M.; Izumi, T.; Nagao, T.; et al. Massive Molecular Gas Companions Uncovered by Very Large Array CO(1-0) Observations of the z = 5.2 Radio Galaxy TN J0924-2201. Astrophys. J. 2023, 944, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pensabene, A.; Cantalupo, S.; Wang, W.; Bacchini, C.; Fraternali, F.; Bischetti, M.; Cicone, C.; Decarli, R.; Pezzulli, G.; Galbiati, M.; et al. ALMA survey of a massive node of the Cosmic Web at z ∼ 3: II. A dynamically cold and massive disk galaxy in the proximity of a hyper-luminous quasar. Astron. Astrophys. 2025, 701, A120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoville, N.; Aussel, H.; Sheth, K.; Scott, K.S.; Sanders, D.; Ivison, R.; Pope, A.; Capak, P.; Vanden Bout, P.; Manohar, S.; et al. The Evolution of Interstellar Medium Mass Probed by Dust Emission: ALMA Observations at z = 0.3–2. Astrophys. J. 2014, 783, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiklind, T.; Conselice, C.J.; Dahlen, T.; Dickinson, M.E.; Ferguson, H.C.; Grogin, N.A.; Guo, Y.; Koekemoer, A.M.; Mobasher, B.; Mortlock, A.; et al. Properties of Submillimeter Galaxies in the CANDELS GOODS-South Field. Astrophys. J. 2014, 785, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traina, A.; Magnelli, B.; Gruppioni, C.; Delvecchio, I.; Parente, M.; Calura, F.; Bisigello, L.; Feltre, A.; Pozzi, F.; Vallini, L. A3COSMOS: Dust mass function and dust mass density at 0.5 <z <6. Astron. Astrophys. 2024, 690, A84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Observing Band | Observing Frequency (GHz) | Beam Size | rms () |

|---|---|---|---|

| Band 3 | 103 | 0.020 | |

| Band 7 | 340 | 0.3 | |

| Band 3 (CO line) | 109 | 1 | – 2 |

| cid_1253 | COSMOS2015 666121 | |

|---|---|---|

| () 1 | <60 | <60 |

| () 1 | < | |

| () | ||

| FWHM () | ||

| () | ||

| () 2 | ||

| () 3 | < | |

| () | ||

| () |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fogasy, J.; Perger, K. A Case Study of a Companion Galaxy Outshining Its AGN Neighbour in a Distant Merger System. Universe 2026, 12, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe12010023

Fogasy J, Perger K. A Case Study of a Companion Galaxy Outshining Its AGN Neighbour in a Distant Merger System. Universe. 2026; 12(1):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe12010023

Chicago/Turabian StyleFogasy, Judit, and Krisztina Perger. 2026. "A Case Study of a Companion Galaxy Outshining Its AGN Neighbour in a Distant Merger System" Universe 12, no. 1: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe12010023

APA StyleFogasy, J., & Perger, K. (2026). A Case Study of a Companion Galaxy Outshining Its AGN Neighbour in a Distant Merger System. Universe, 12(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe12010023