Late-Time Constraints on Future Singularity Dark Energy Models from Geometry and Growth

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Linear Perturbations and Growth of Structure

3. FSFS and SFS as Dynamical Dark Energy Candidates

4. Data Sets and Likelihood Construction

4.1. Background Evolution and Geometric Functions

4.2. Pantheon + SH0ES SNe Ia with Analytic Profiling over the Absolute Magnitude

4.3. Observational Hubble Data

4.4. DESI DR2 BAO: AP-Only Constraints

4.5. Growth Data with Geometric Rescaling and Profiled

4.5.1. Perturbations and

4.5.2. Analytic Profiling of with a Planck Prior

4.6. Total Goodness of Fit and Profiling in

4.7. Geometry-Only and Growth-Only Fits, and Profiled Contour Regions

5. Results

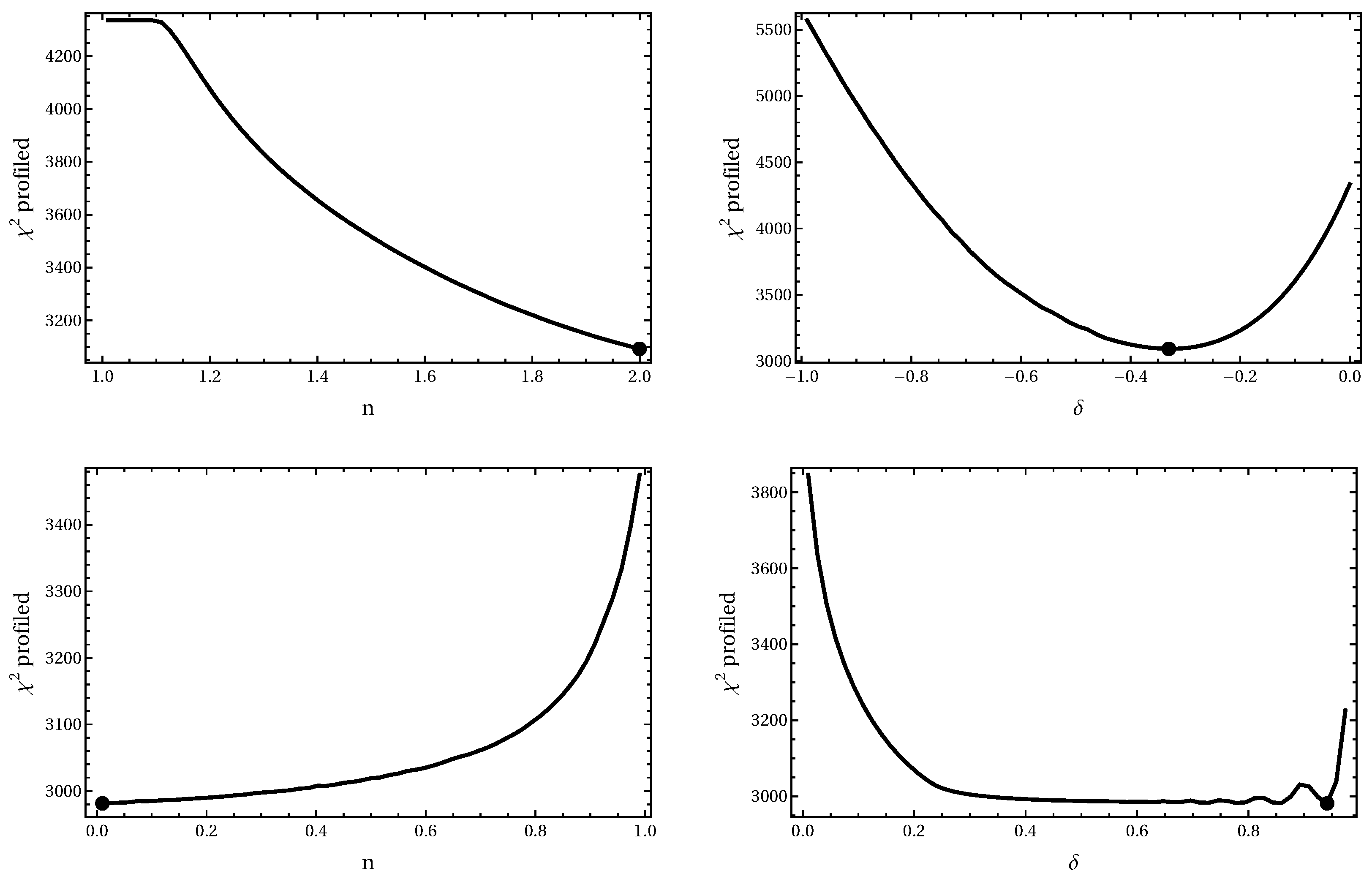

5.1. Overview of the Scan and Profiled Likelihood

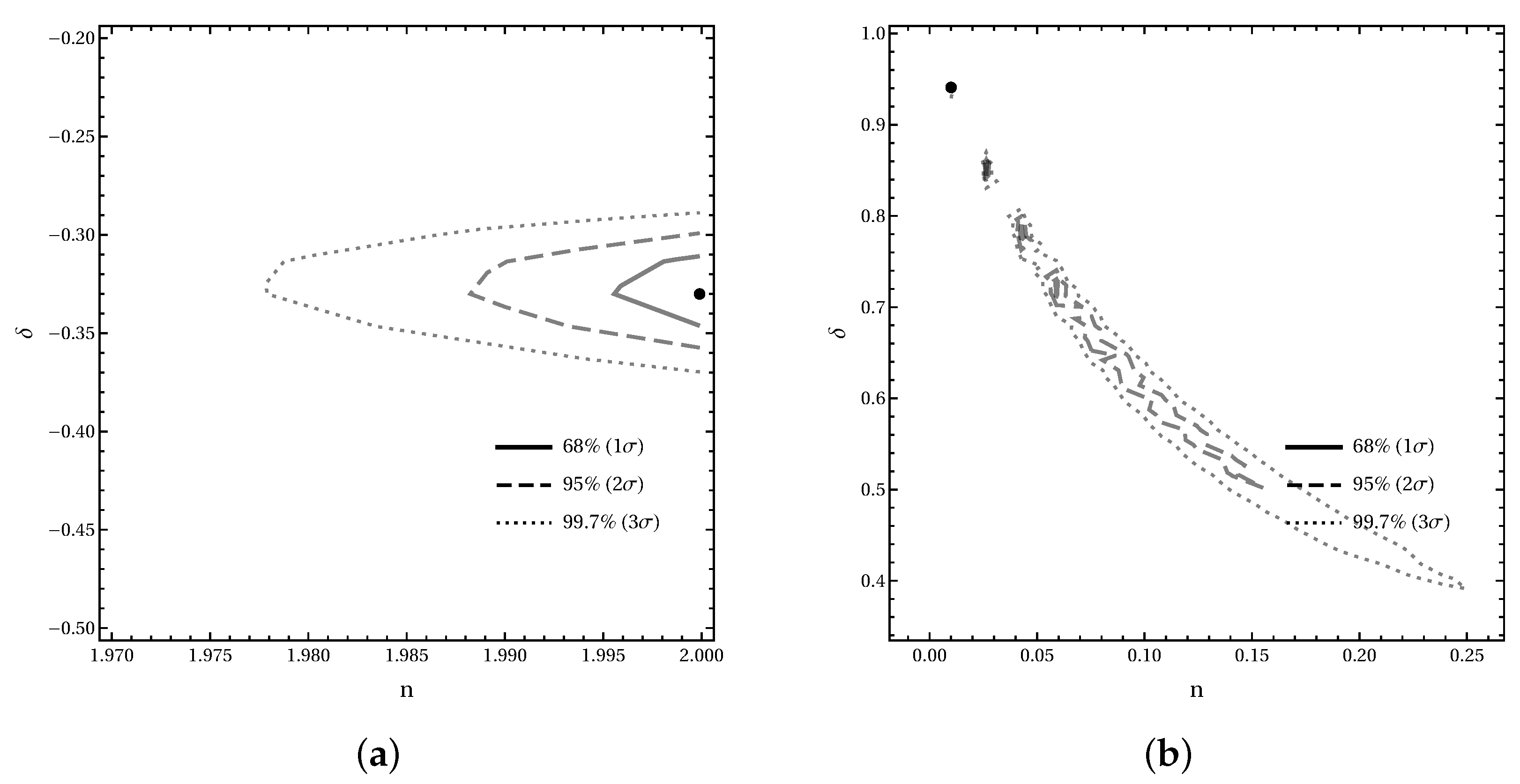

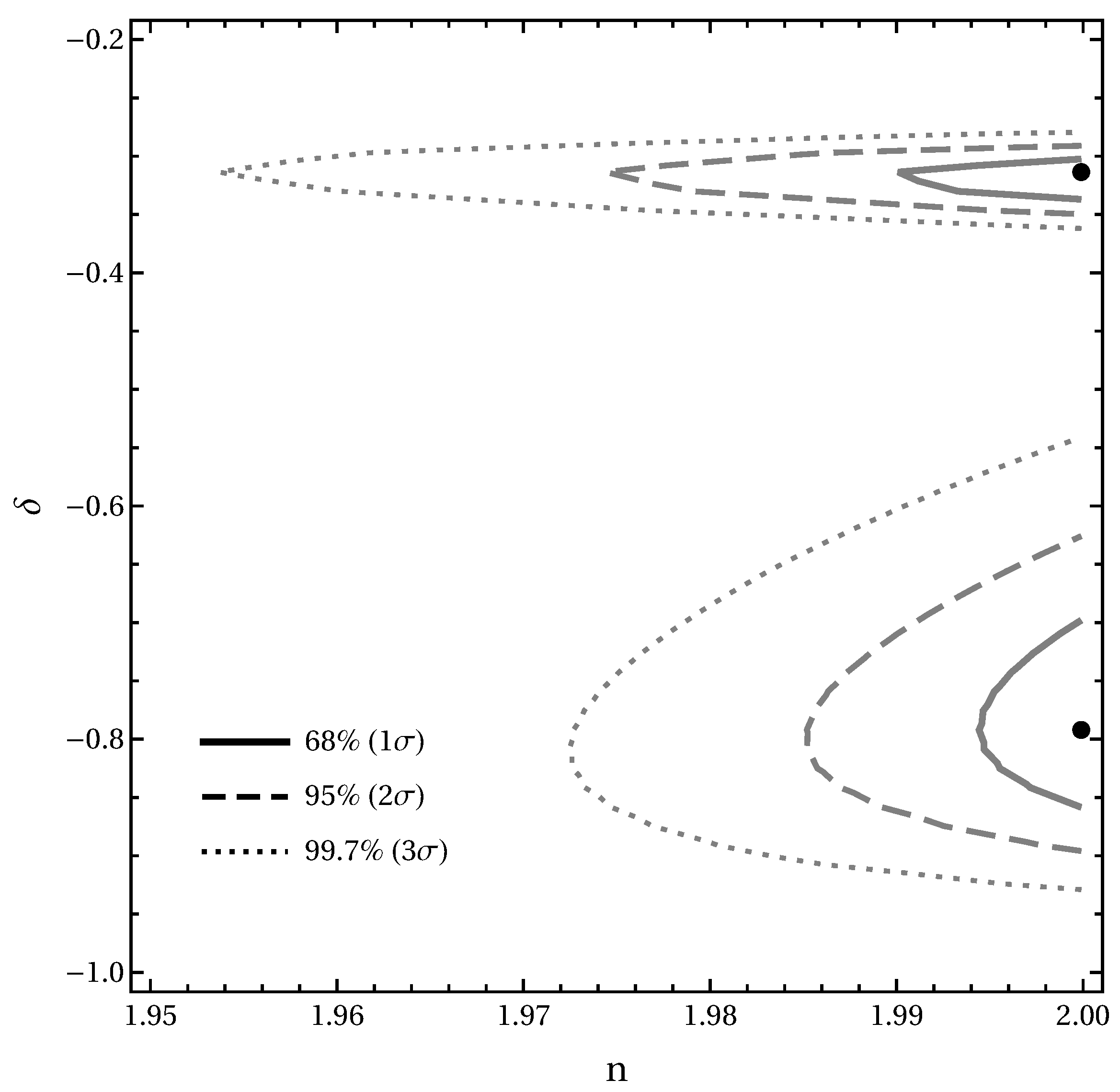

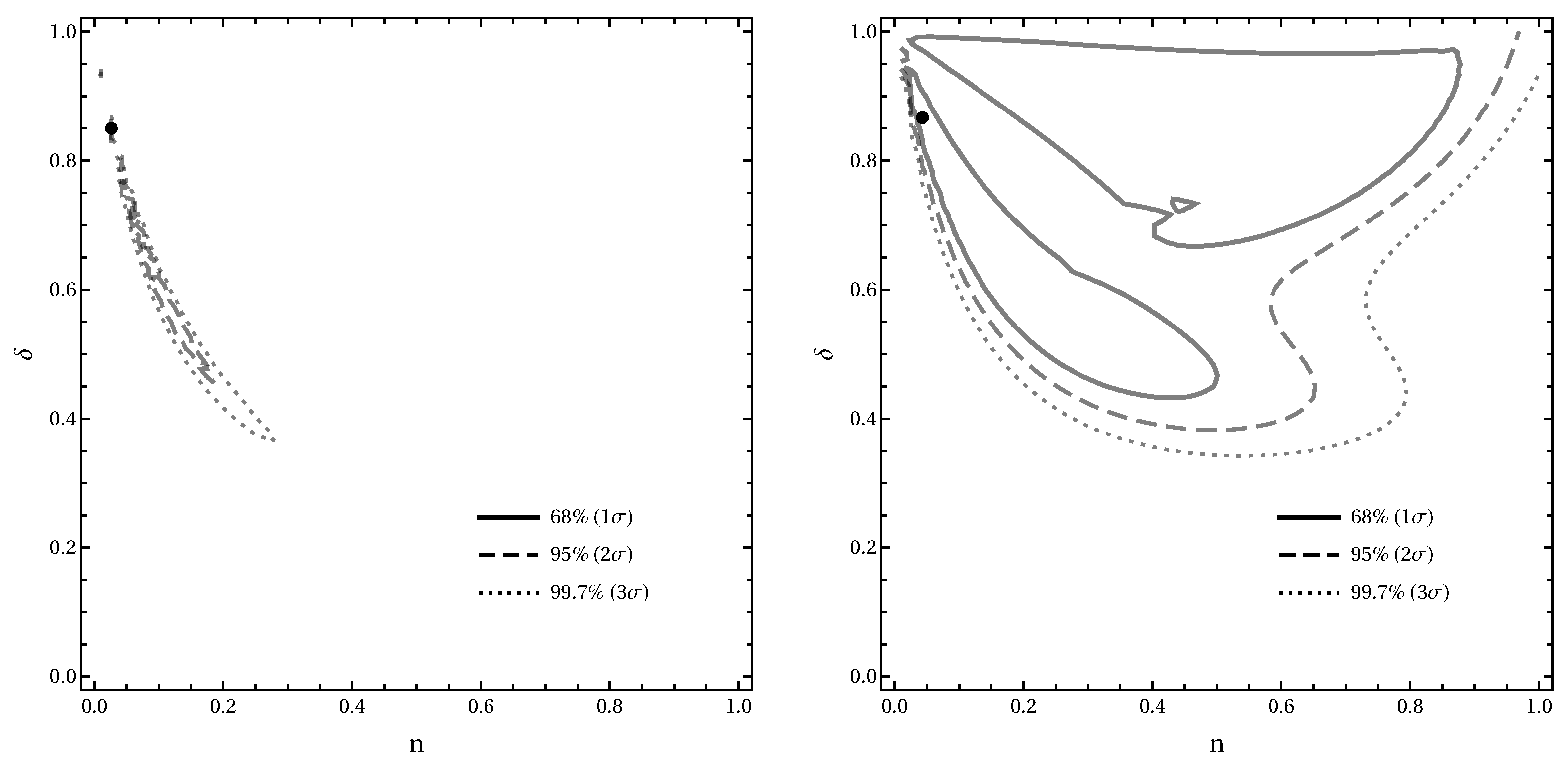

5.2. Profile–Likelihood Constraints in the Plane

5.3. Best-Fit Predictions for Background and Growth Observables

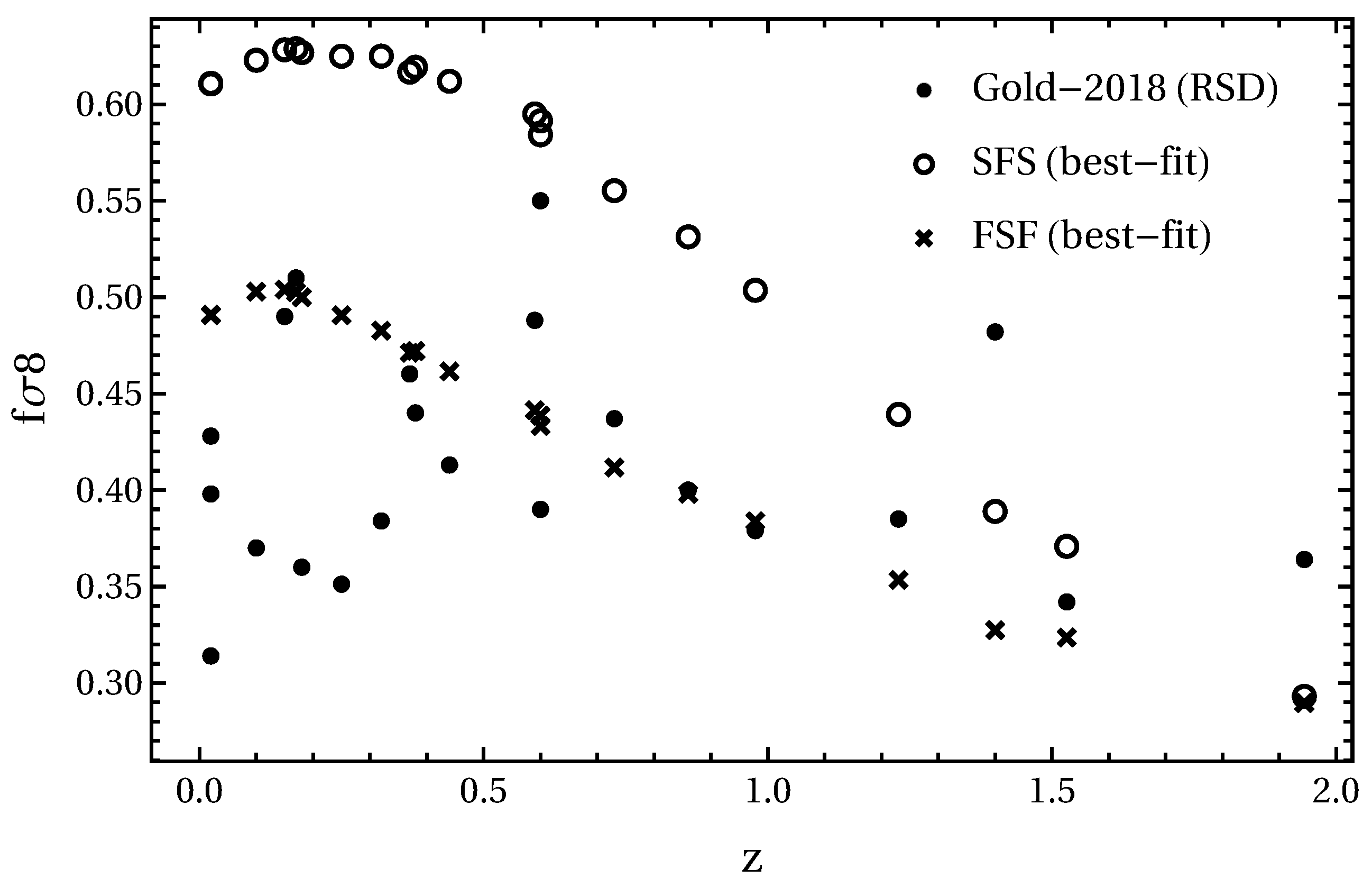

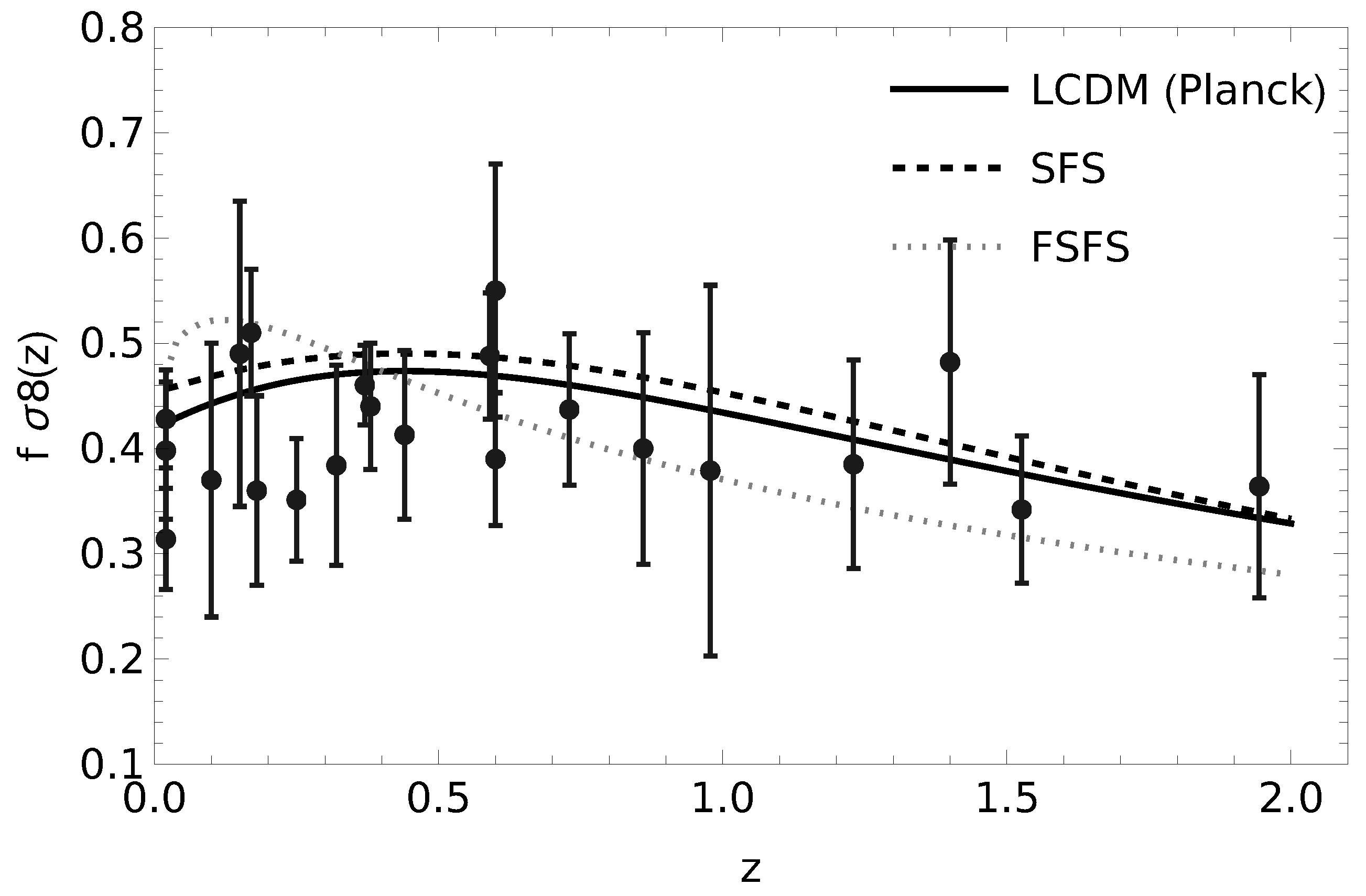

5.3.1. Growth:

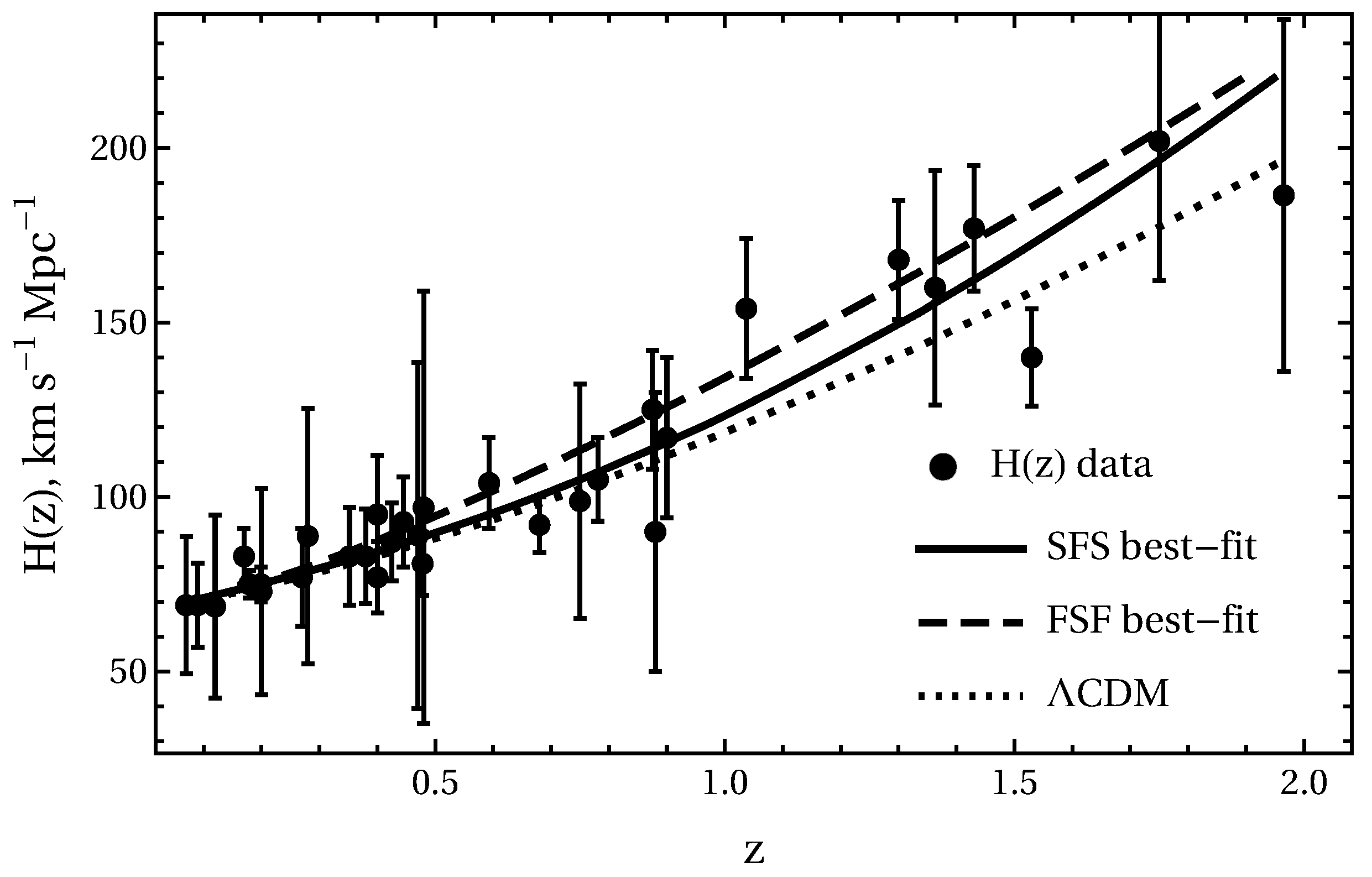

5.3.2. Expansion Rate:

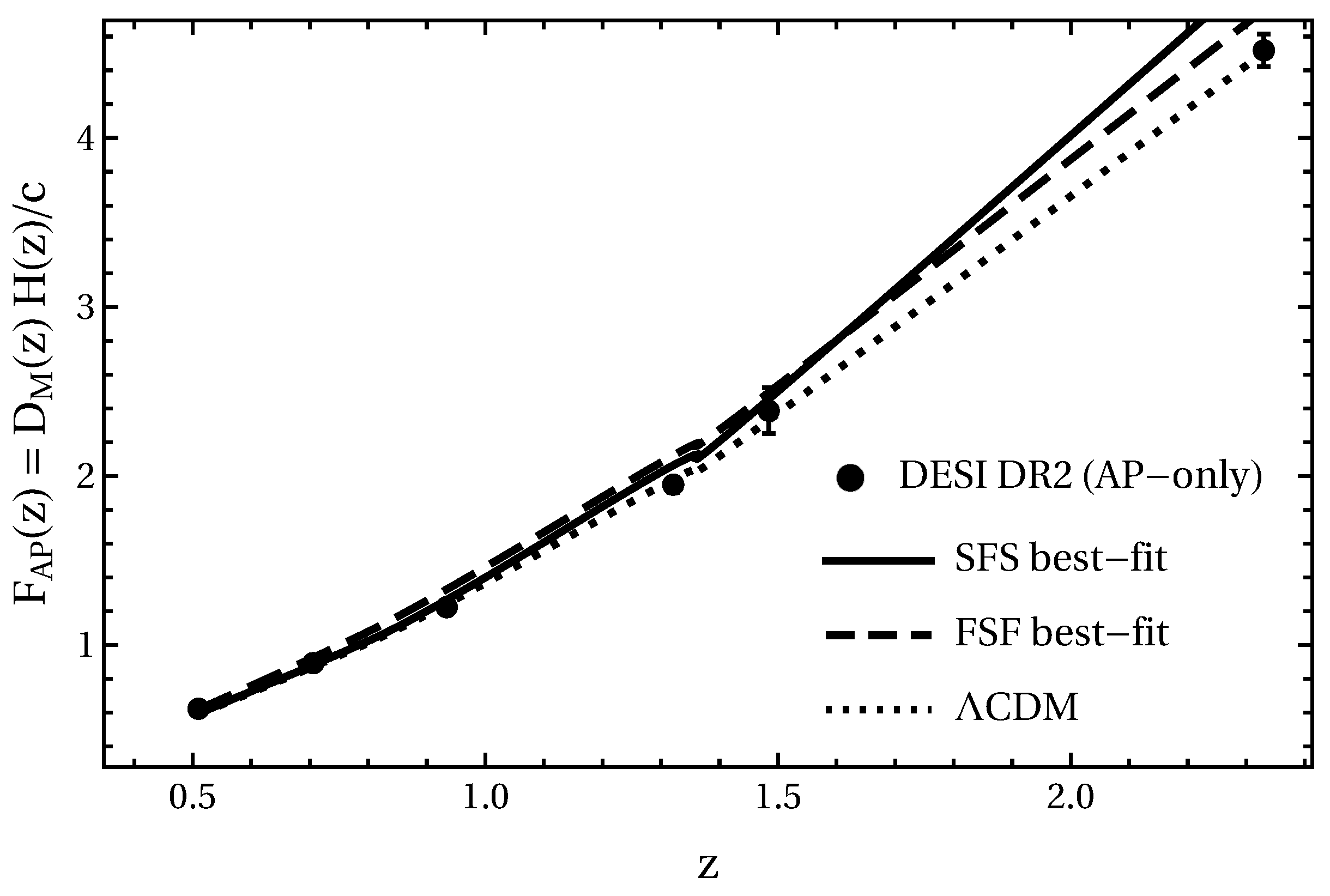

5.3.3. BAO AP-Only:

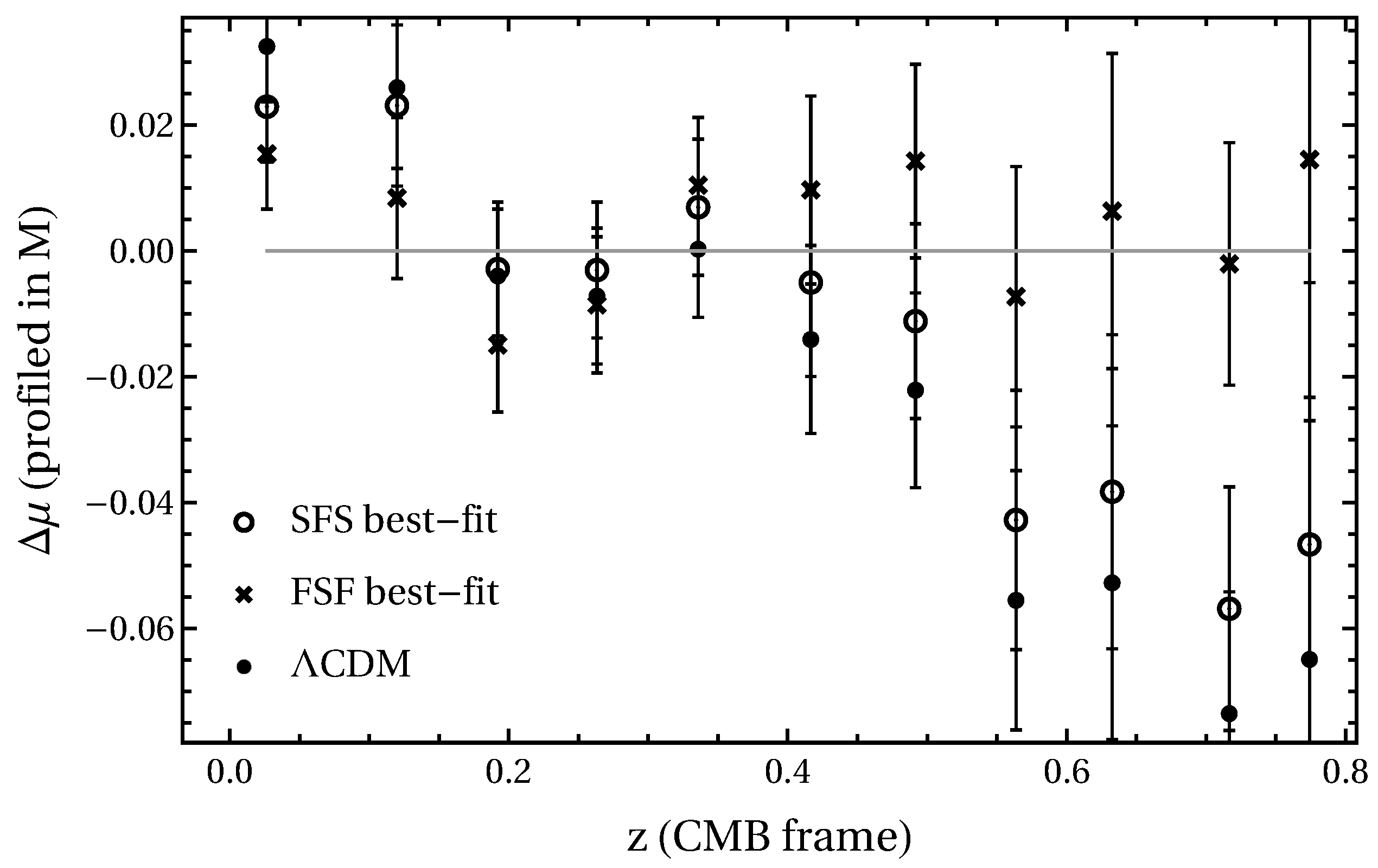

5.3.4. Supernovae: Binned Residuals with Profiled Magnitude

5.4. Goodness of Fit, CDM Comparison, and Geometry vs. Growth Split

5.5. Model-Selection Diagnostics (AIC/BIC)

5.6. Validation: Grid-Resolution Stability and Local Refinement

5.6.1. Sudden Future Singularity

5.6.2. Finite Scale Factor Singularity

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CDM | Lambda Cold Dark Matter |

| SFS | Sudden Future Singularity |

| FSFS | Finite Scale Factor Singularity |

| DESI | Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument |

| CMB | Cosmic Microwave Background |

| BAO | Baryon Acoustic Oscillations |

| SNeIa | Type Ia Supernovae |

| LSS | Large-Scale Structure |

| 1 | All calculations and figures were produced using Mathematica (Wolfram Research, Inc., Mathematica, Version 13.0, Champaign, IL (2021)). |

References

- Riess, A.G.; Filippenko, A.V.; Challis, P.; Clocchiatti, A.; Diercks, A.; Garnavich, P.M.; Gillil, R.L.; Hogan, C.J.; Jha, S.; Kirshner, R.P.; et al. Observational Evidence from Supernovae for an Accelerating Universe and a Cosmological Constant. Astron. J. 1998, 116, 1009–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlmutter, S.; Aldering, G.; Goldhaber, G.; Knop, R.A.; Nugent, P.; Castro, P.G.; Deustua, S.; Fabbro, S.; Goobar, A.; Groom, D.E.; et al. Measurements of Ω and Λ from 42 High-Redshift Supernovae. Astrophys. J. 1999, 517, 565–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, N.; Rubin, D.; Lidman, C.; Aldering, G.; Amanullah, R.; Barbary, K.; Barrientos, L.F.; Botyanszki, J.; Brodwin, M.; Connolly, N.; et al. The Hubble Space Telescope Cluster Supernova Survey: V. Improving the Dark Energy Constraints Above z > 1 and Building an Early-Type-Hosted Supernova Sample. Astrophys. J. 2012, 746, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betoule, M.; Marriner, J.; Regnault, N.; Cuillandre, J.C.; Astier, P.; Guy, J.; Ball, C.; El Hage, P.; Hardin, D.; Kessler, R.; et al. Improved Photometric Calibration of the SNLS and the SDSS Supernova Surveys. Astron. Astrophys. 2013, 552, A124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenstein, D.J.; Zehavi, I.; Hogg, D.W.; Scoccimarro, R.; Blanton, M.R.; Nichol, R.C.; Scranton, R.; Seo, H.J.; Tegmark, M.; Zheng, Z.; et al. Detection of the Baryon Acoustic Peak in the Large-Scale Correlation Function of SDSS Luminous Red Galaxies. Astrophys. J. 2005, 633, 560–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassett, B.A.; Hlozek, R. Baryon Acoustic Oscillations. arXiv 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, S.; Ata, M.; Bailey, S.; Beutler, F.; Bizyaev, D.; Blazek, J.A.; Bolton, A.S.; Brownstein, J.R.; Burden, A.; Chuang, C.H.; et al. The clustering of galaxies in the completed SDSS-III Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey: Cosmological analysis of the DR12 galaxy sample. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2017, 470, 2617–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.; Aubert, M.; Avila, S.; Ball, C.; Bautista, J.E.; Bershady, M.A.; Bizyaev, D.; Blanton, M.R.; Bolton, A.S.; Bovy, J.; et al. The Completed SDSS-IV extended Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey: Cosmological Implications from two Decades of Spectroscopic Surveys at the Apache Point observatory. arXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghanim, N.; Akrami1, Y.; Ashdown, M.; Aumont, J.; Baccigalupi, C.; Ballardini, M.; Banday, A.J.; Barreiro, R.B.; Bartolo, N.; Basak, S.; et al. Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters. Astron. Astrophys. 2020, 641, A6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, D.H.; Mortonson, M.J.; Eisenstein, D.J.; Hirata, C.; Riess, A.G.; Rozo, E. Observational Probes of Cosmic Acceleration. Phys. Rept. 2013, 530, 87–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzano, V.; Rodney, S.A.; Sendra, I.; Lazkoz, R.; Riess, A.G.; Postman, M.; Broadhurst, T.; Coe, D. Improving Dark Energy Constraints with High Redshift Type Ia Supernovae from CANDELS and CLASH. Astron. Astrophys. 2013, 557, A64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lazkoz, R.; Alcaniz, J.; Escamilla-Rivera, C.; Salzano, V.; Sendra, I. BAO cosmography. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2013, 1312, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesseris, S.; Pantazis, G.; Perivolaropoulos, L. Tension and constraints on modified gravity parametrizations of Geff(z) from growth rate and Planck data. Phys. Rev. D 2017, 96, 023542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagredo, B.; Nesseris, S.; Sapone, D. Internal robustness of growth rate data. Phys. Rev. D 2018, 98, 083543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ade, P.A.R.; Aghanim, N.; Arnaud, M.; Ashdown, M.; Aumont, J.; Baccigalupi, C.; Banday, A.J.; Barreiro, R.B.; Bartlett, J.G.; Bartolo, N.; et al. Planck 2015 results. XIII. Cosmological parameters. arxiv 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.; Ho, S.; Silvestri, A. Testing deviations from LCDM with growth rate measurements from six large-scale structure surveys at z = 0.06–1. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2016, 456, 3743–3756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albarran, I.; Bouhmadi-López, M.; Morais, J. Cosmological perturbations in an effective and genuinely phantom dark energy Universe. Phys. Dark Universe 2017, 16, 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsujikawa, S.; Gannouji, R.; Moraes, B.; Polarski, D. The dispersion of growth of matter perturbations in f(R) gravity. Phys. Rev. 2009, D80, 084044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gannouji, R.; Moraes, B.; Polarski, D. The growth of matter perturbations in f(R) models. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2009, 2009, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, E.V.; Cahn, R.N. Parameterized Beyond-Einstein Growth. Astropart. Phys. 2007, 28, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamba, K.; Lopez-Revelles, A.; Myrzakulov, R.; Odintsov, S.D.; Sebastiani, L. Cosmic history of viable exponential gravity: Equation of state oscillations and growth index from inflation to dark energy era. Class. Quant. Grav. 2013, 30, 015008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrow, J.D. Sudden future singularities. Class. Quant. Grav. 2004, 21, L79–L82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrow, J.D.; Tsagas, C.G. Structure and stability of the Lukash plane-wave spacetime. Class. Quant. Grav. 2005, 22, 825–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nojiri, S.; Odintsov, S.D. Inhomogeneous equation of state of the universe: Phantom era, future singularity and crossing the phantom barrier. Phys. Rev. 2005, D72, 023003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adame, A.; Aguilar, J.; Ahlen, S.; Alam, S.; Alexander, D.M.; Alvarez, M.; Alves, O.; Anand, A.; Andrade, U.; Armengaud, E.; et al. DESI 2024 VI: Cosmological Constraints from the Measurements of Baryon Acoustic Oscillations. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2025, 2025, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beutler, F.; Saito, S.; Seo, H.J.; Brinkmann, J.; Dawson, K.S.; Eisenstein, D.J.; Font-Ribera, A.; Ho, S.; McBride, C.K.; Montesano, F.; et al. The clustering of galaxies in the SDSS-III Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey: Testing gravity with redshift-space distortions using the power spectrum multipoles. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2014, 443, 1065–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dent, J.B.; Dutta, S. On the dangers of using the growth equation on large scales in the Newtonian gauge. Phys. Rev. D 2009, 79, 063516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dent, J.B.; Dutta, S.; Perivolaropoulos, L. New Parametrization for the Scale Dependent Growth Function in General Relativity. Phys. Rev. 2009, D80, 023514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perivolaropoulos, L. Consistency of LCDM with Geometric and Dynamical Probes. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2010, 222, 012024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denkiewicz, T. Dark energy and dark matter perturbations in singular universes. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2015, 37, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dąbrowski, M.P.; Denkiewicz, T.; Hendry, M.A. How far is it to a sudden future singularity of pressure? Phys. Rev. 2007, D75, 123524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nojiri, S.; Odintsov, S.D. Unified cosmic history in modified gravity: From F(R) theory to Lorentz non-invariant models. Phys. Rep. 2011, 505, 59–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattoën, C.; Visser, M. Necessary and sufficient conditions for big bangs, bounces, crunches, rips, sudden singularities and extremality events. Class. Quantum Gravity 2005, 22, 4913–4930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Jambrina, L.; Lazkoz, R. Geodesic behavior of sudden future singularities. Phys. Rev. D 2004, 70, 121503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dąbrowski, M.P.; Denkiewicz, T.; Martins, C.J.A.P.; Vielzeuf, P.E. Variations of the fine-structure constant α in exotic singularity models. Phys. Rev. D 2014, 89, 123512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scolnic, D.; Brout, D.; Carr, A.; Riess, A.G.; Davis, T.M.; Dwomoh, A.; Jones, D.O.; Ali, N.; Charvu, P.; Chen, R.; et al. The Pantheon + Analysis: The Full Data Set and Light-curve Release. Astrophys. J. 2022, 938, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brout, D.; Scolnic, D.; Popovic, B.; Riess, A.G.; Carr, A.; Zuntz, J.; Kessler, R.; Davis, T.M.; Hinton, S.; Jones, D.; et al. The Pantheon + Analysis: Cosmological Constraints. Astrophys. J. 2022, 938, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riess, A.G.; Yuan, W.; Macri, L.M.; Scolnic, D.; Brout, D.; Casertano, S.; Jones, D.O.; Murakami, Y.; Anand, G.S.; Breuval, L.; et al. A Comprehensive Measurement of the Local Value of the Hubble Constant with 1 km s−1 Mpc−1 Uncertainty from the Hubble Space Telescope and the SH0ES Team. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2022, 934, L7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, R.; Verde, L.; Treu, T.; Stern, D. Constraints on the Equation of State of Dark Energy and the Hubble Constant from Stellar Ages and the Cosmic Microwave Background. Astrophys. J. 2003, 593, 622–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, J.; Verde, L.; Jimenez, R. Constraints on the redshift dependence of the dark energy potential. Phys. Rev. D 2004, 71, 123001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, D.; Jimenez, D.; Verde, R.; Kamionkowski, L.; Stanford, M.; Adam, S. Cosmic Chronometers: Constraining the Equation of State of Dark Energy. I: H(z) Measurements. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2010, 2010, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moresco, M.; Cimatti, A.; Jimenez, R.; Pozzetti, L.; Zamorani, G.; Bolzonella, M.; Dunlop, J.; Lamareille, F.; Mignoli, M.; Pearce, H.; et al. Improved constraints on the expansion rate of the Universe up to z∼1.1 from the spectroscopic evolution of cosmic chronometers. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2012, 2012, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moresco, M. Raising the bar: New constraints on the Hubble parameter with cosmic chronometers at z∼2. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. Lett. 2015, 450, L16–L20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moresco, M.; Pozzetti, L.; Cimatti, A.; Jimenez, R.; Maraston, C.; Verde, L.; Thomas, D.; Citro, A.; Tojeiro, R.; Wilkinson, D. A 6of the epoch of cosmic re-acceleration. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2016, 2016, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghi, N.; Moresco, M.; Cimatti, A. Toward a Better Understanding of Cosmic Chronometers: A New Measurement of H(z) at z∼0.7. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2021, 928, L4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcock, C.; Paczynski, B. An Evolution Free Test for Non-Zero Cosmological Constant. Nature 1979, 281, 358–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballinger, W.E.; Peacock, J.A.; Heavens, A.F. Measuring the cosmological constant with redshift surveys. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1996, 282, 877–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, N. Clustering in real space and in redshift space. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1987, 227, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, A.J.S. Linear Redshift Distortions: A Review. In The Evolving Universe; Astrophysics and Space Science Library; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1998; Volume 231, pp. 185–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaike, H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 1974, 19, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, G. Estimating the Dimension of a Model. Ann. Stat. 1978, 6, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data Set | Model | n | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALL | CDM | 2925.53 | 0.00 | – | – | – | 0.814213 |

| ALL | SFS | 3092.43 | +166.90 | 1.9999 | −0.330067 | 0.9999 | 0.796342 |

| ALL | FSFS | 2981.37 | +55.84 | 0.0100 | 0.941000 | 0.677318 | 0.812095 |

| GEOM | CDM | 2909.56 | 0.00 | – | – | – | – |

| GEOM | SFS | 2926.37 | +16.80 | 1.9999 | −0.313568 | 0.9999 | – |

| GEOM | FSFS | 2947.81 | +38.25 | 0.0264983 | 0.850015 | 0.699058 | – |

| GROW | CDM | 15.9714 | 0.0000 | – | – | – | 0.814213 |

| GROW | SFS | 134.263 | +118.29 | 1.9999 | −0.792020 | 0.9999 | 0.800279 |

| GROW | FSFS | 12.5879 | −3.38 | 0.0429967 | 0.866680 | 0.733248 | 0.816469 |

| Filter | Criterion | Motivation/Failure Mode |

|---|---|---|

| Time location prior | Excludes singularities in the past; enforces the adopted model domain. | |

| Background positivity | and on the integration interval | Rejects non-expanding or ill-defined backgrounds. |

| Dark-energy viability | along the sampled background | Excludes unphysical effective-energy histories in the present setup. |

| ODE integrability (background) | Successful background solve (no NaN/Indeterminate) | Discards points where the background ODE system fails or becomes numerically unstable. |

| ODE integrability (perturbations) | Successful perturbation solve (no NaN/Indeterminate) | Discards points where the linear-growth system cannot be evolved reliably. |

| Model | Scan | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SFS | 1.9999 | 0.9999 | 3092.43 | ||

| SFS | 1.9999 | 0.9999 | 3092.65 | ||

| SFS | zoom () | 1.9999 | 0.9999 | 3092.41 | |

| FSFS | 0.01 | 0.941 | 0.677318 | 2981.37 | |

| FSFS | 0.01 | 0.941 | 0.677076 | 2981.58 | |

| FSFS | zoom () | 0.0135 | 0.9185 | 0.693061 | 2980.35 |

| Data Set | Model | N | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALL | CDM | 1760 | 2925.53 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| ALL | SFS | 1760 | 3092.43 | 166.90 | 172.90 | 189.32 |

| ALL | FSFS | 1760 | 2981.37 | 55.84 | 61.84 | 78.26 |

| GEOM | CDM | 1738 | 2909.56 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| GEOM | SFS | 1738 | 2926.37 | 16.81 | 22.81 | 39.19 |

| GEOM | FSFS | 1738 | 2947.81 | 38.25 | 44.25 | 60.63 |

| GROW | CDM | 22 | 15.97 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| GROW | SFS | 22 | 134.26 | 118.29 | 124.29 | 127.56 |

| GROW | FSFS | 22 | 12.59 | −3.38 | 2.62 | 5.89 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Denkiewicz, T. Late-Time Constraints on Future Singularity Dark Energy Models from Geometry and Growth. Universe 2026, 12, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe12010014

Denkiewicz T. Late-Time Constraints on Future Singularity Dark Energy Models from Geometry and Growth. Universe. 2026; 12(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe12010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleDenkiewicz, Tomasz. 2026. "Late-Time Constraints on Future Singularity Dark Energy Models from Geometry and Growth" Universe 12, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe12010014

APA StyleDenkiewicz, T. (2026). Late-Time Constraints on Future Singularity Dark Energy Models from Geometry and Growth. Universe, 12(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe12010014