Abstract

This review investigates the application of unsupervised machine learning algorithms to astronomical data. Unsupervised machine learning enables researchers to analyze large, high-dimensional, and unlabeled datasets and is sometimes considered more helpful for exploratory analysis because it is not limited by present knowledge and can therefore be used to extract new knowledge. Unsupervised machine learning algorithms that have been repeatedly applied to analyze astronomical data are classified according to their usage, including dimension reduction and clustering. This review also discusses anomaly detection and symbolic regression. For each algorithm, this review discusses the algorithm’s functioning in mathematical and statistical terms, the algorithm’s characteristics (e.g., advantages and shortcomings and possible types of inputs), and the different types of astronomical data analyzed with the algorithm. Example figures are generated. The algorithms are tested on synthetic datasets. This review aims to provide an up-to-date overview of both the high-level concepts and detailed applications of various unsupervised learning methods in astronomy, highlighting their advantages and disadvantages to help researchers new to unsupervised learning.

1. Introduction

Machine learning (ML) has been applied to various analyses of astronomical data, such as analyzing spectral data (e.g., [1,2,3]), catalogs (e.g., [4,5,6]), light curves (e.g., [7,8,9]), and images (e.g., [10,11,12]). ML is a subfield of artificial intelligence, aiming to mimic human brain functions using computers. Rather than manually coding every step, as in traditional programming, researchers use ML algorithms to analyze data. ML adjusts models iteratively to minimize errors. Parameters are either automatically optimized by ML or manually fine-tuned by researchers. In simple terms, ML focuses on achieving a desired outcome rather than specifying how to produce it, performing tasks with general guidance rather than detailed instructions [13]. Unlike traditional programming, ML often involves iterative processes that cannot be easily described by equations.

The growing significance of ML arises from the rapidly increasing volume and complexity of astronomical data collected using progressively advanced instruments [14]. With the advanced instruments, high-resolution, high-dimensional datasets are collected. ML offers efficient and objective solutions for analyzing such large datasets. Therefore, ML has become increasingly popular among astronomers.

There are two types of ML techniques: unsupervised and supervised. Unsupervised ML conducts exploratory data analysis, discovering unknown data features, without any prior information on classification. In comparison, supervised ML requires a labeled dataset (i.e., a training set), where the features are known [14]. Supervised ML learns from this labeled dataset and makes predictions on new data with the same properties [14,15]. This review focuses on unsupervised ML algorithms, which are very crucial for scientific research because they are not constrained by existing knowledge and can uncover new insights [14].

In this review, we classify unsupervised ML algorithms into two categories based on their primary use: dimensionality reduction and clustering. Within the discussion of dimensionality reduction algorithms, we also include neural network-based methods. While clustering and dimensionality reduction are typically framed as objectives, neural networks are better viewed as model architectures that extract information from data; the resulting learned representations can then be used to perform tasks such as clustering or dimensionality reduction.

Clustering refers to finding the concentration of multivariable data points [16]. In simpler words, clustering groups objects so that those in the same group are more similar to each other than to those in different groups.

Dimensionality reduction selects or constructs a subset of features that best describe the data, reducing the number of features [14]. It retains essential information while discarding trivial information [16]. Manifold learning is an important branch of dimensionality reduction that performs non-linear reduction to unfold the surface of data and reveal its underlying structure [16].

A neural network model is designed to mimic the structure and function of the human brain [16]. A neural network consists of multiple interconnected neurons or layers of neurons, where each neuron receives inputs and transmits outputs. A shallow neural network has one or two hidden layers, while deep learning models have three or more. While deep learning can be used for supervised ML, this review focuses on unsupervised neural networks.

This review may serve as an up-to-date, comprehensive manual on unsupervised ML algorithms and their applications in astronomy, tailored for astronomy researchers new to ML. Emerging approaches—such as semi-supervised, self-supervised, and hybrid models—provide additional strategies for analyzing complex astronomical datasets and are discussed in detail in Section 5.

2. Dimensionality Reduction

This section introduces various dimensionality reduction algorithms, including principal component analysis, multi-dimensional scaling and isometric feature mapping, locally linear embedding, t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding, self-organizing maps, and auto-encoders and variational auto-encoders. These algorithms project high-dimensional data into lower dimensions by identifying linear or non-linear structures that preserve essential information and, in some cases, by studying the underlying manifold1 of the data.

2.1. Linear Methods

We examine the commonly used linear dimensionality reduction algorithms PCA and its kernel-based extension, kernel PCA.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Kernal PCA

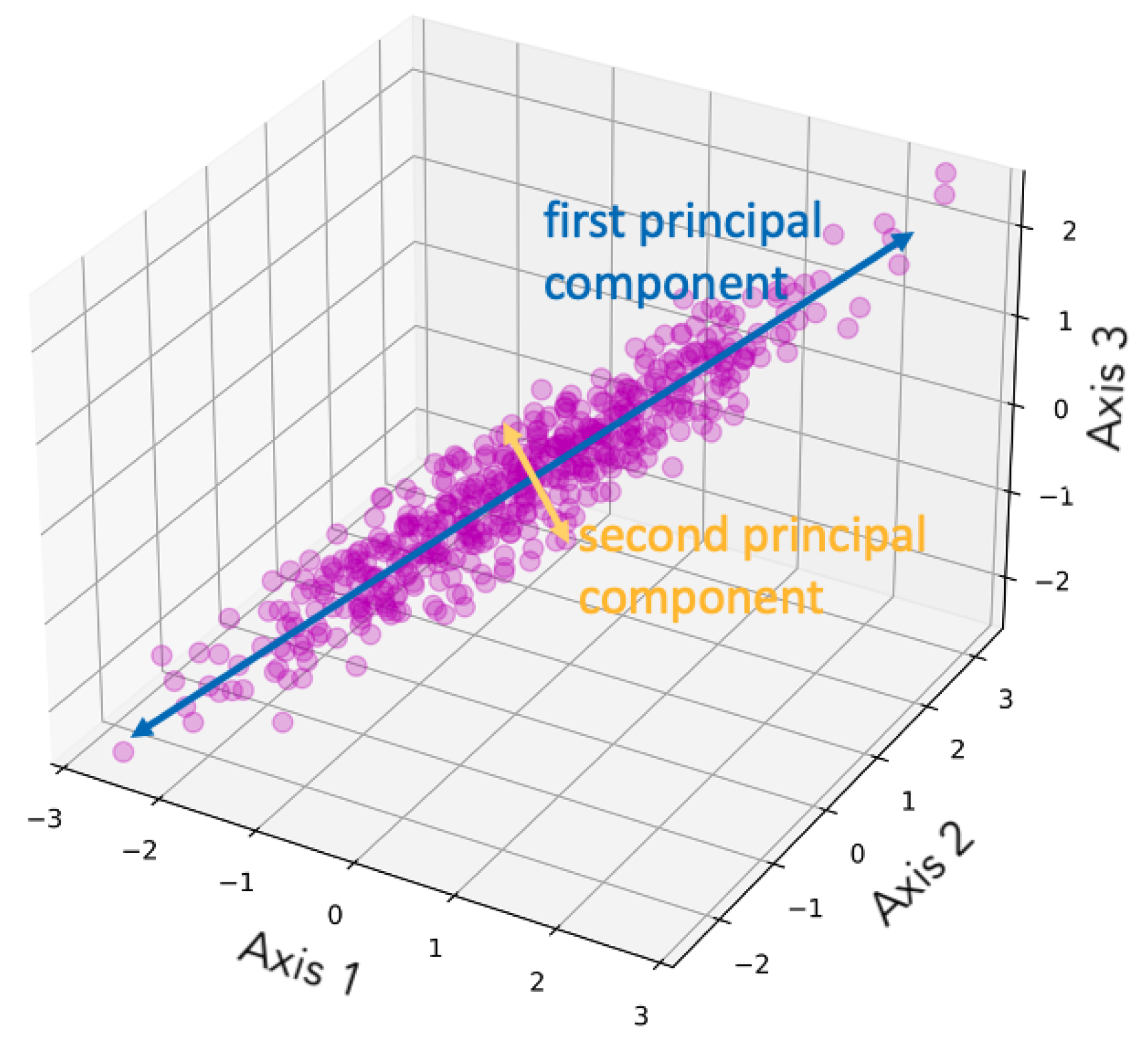

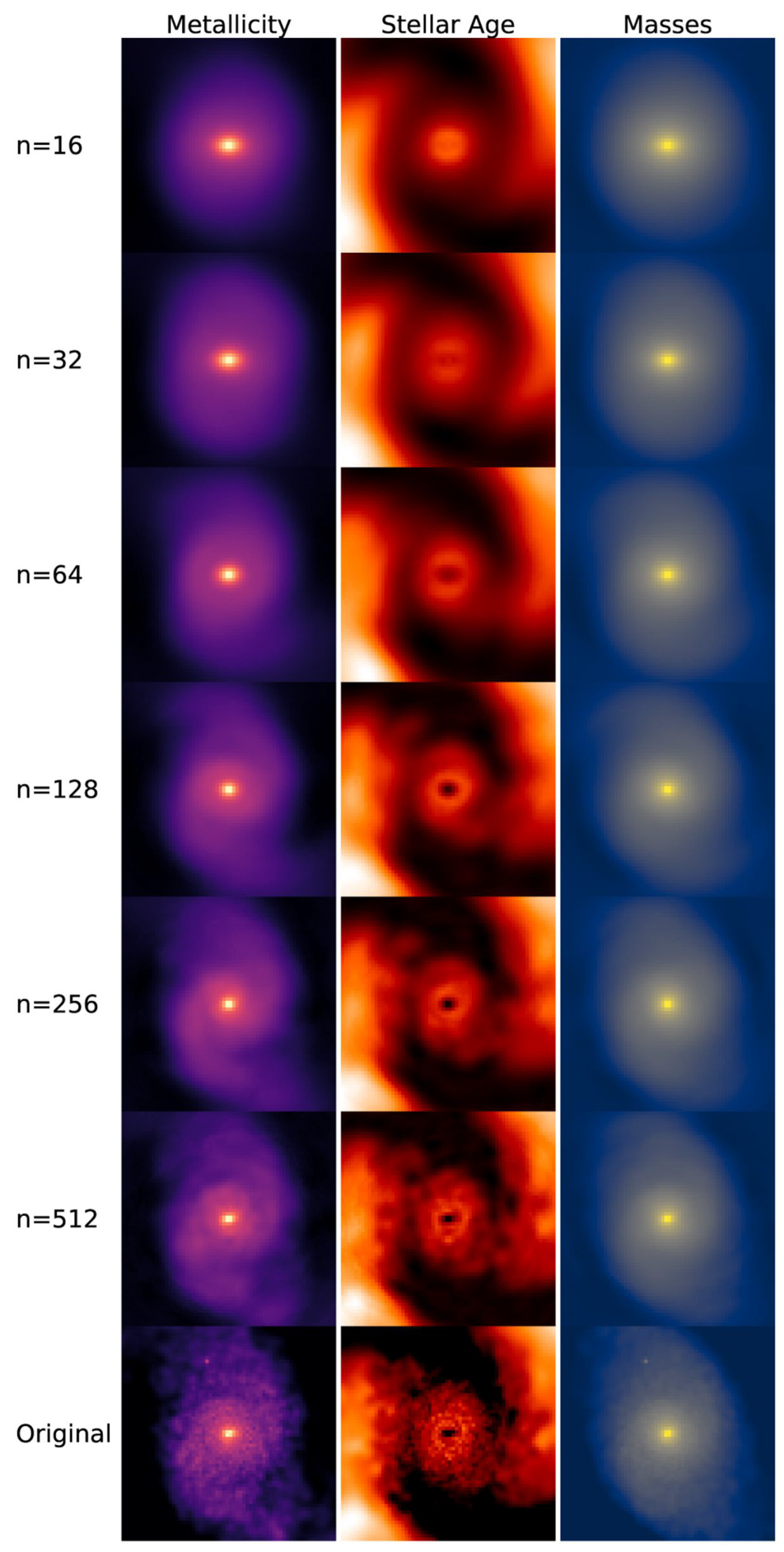

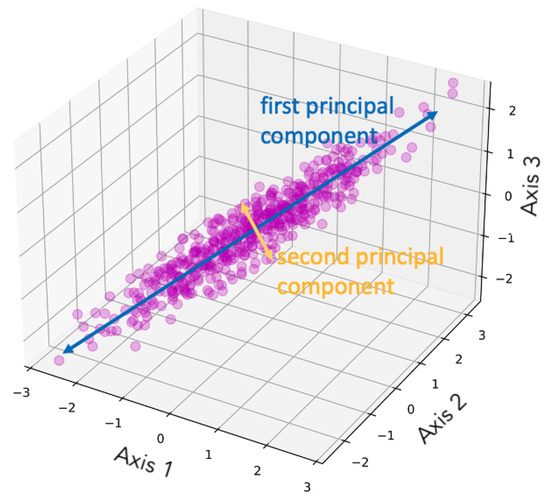

Principal component analysis (PCA), as suggested by its name, is a dimensionality reduction method that focuses on the principal components (PCs) of the multivariate dataset. PCA was initially developed by Pearson [17] and further improved by Hotelling [18,19]. PCA performs singular value decomposition (SVD) and can be interpreted as a rotation and projection of the dataset to maximize variance, thereby highlighting the most important features [16]. PCA constructs a covariance matrix of the dataset, and the orthonormal eigenvectors are the PCs (i.e., the axes) [14]. The PCs are identified sequentially: the first maximizes the variance, the second is orthogonal to the first while maximizing the residual variance, and the subsequent components are orthogonal to all prior components [16]. The PCs are linearly uncorrelated, so applying PCA removes the correlation between multiple dimensions, simplifying the data. The first few components convey most of the information [15]. Therefore, when all PCs are retained, the transformation is simply a rotation of the original coordinate system and thus no information is lost; when k PCs are used, the data are reduced to k dimensions. Figure 1 is a demonstration of dimensionality reduction with PCA, showing how the first two PCs are selected given the dataset. Figure 2 illustrates an example of PCA applied to images, showing how the reconstructed images retain the main features of the original data. The number n on the left indicates the number of PCs used for the reconstruction. A smaller number of components corresponds to greater compression in feature space, which results in a blurrier reconstructed image.

Figure 1.

Demonstration of dimensionality reduction with PCA, showing how the two PCs are selected given the dataset. The figure is taken from Follette [20], licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/).

Figure 2.

Example of PCA applied to images. Figure is taken from Çakir, U. and Buck, T. [21], licensed under CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Choosing an appropriate number of principal components k is a critical step in PCA. Retaining too few components risks discarding meaningful structure in the data, whereas retaining too many diminishes the benefits of dimensionality reduction. The optimal choice of k depends strongly on the dataset’s size and characteristics, as well as on the intended purpose of dimensionality reduction (e.g., visualization versus pre-processing). A common approach is to examine how the reconstruction error—quantifying the discrepancy between the reconstructed and original data—varies with the number of retained PCs. In many practical applications, the eigenvalue decays approximately exponentially or as a power law because additional PCs contribute only marginal improvements. For example, Çakir, U. and Buck, T. [21] retain 215 three-dimensional eigengalaxies (PCs) from an original sample of 11,960 galaxies. They report that 90% of their input images produce reconstruction errors below 0.027, which they use to validate that their chosen value of k is adequate.

There are some shortcomings in PCA. Firstly, pre-processing (i.e., treatment of the dataset before applying the algorithm) is necessary for PCA to yield informative results [16]. PCA is sensitive to outliers, so outliers need to be removed. Then, due to the property of PCA, the data needs to be normalized beforehand, similar to K-means (see Section 3.2) and some other algorithms. For instance, z-score normalization, sometimes referred to as feature scaling, can be applied. The equation is , where z is the z-score of feature i for a given data point, is the value of that feature for that data point, and and are the mean and standard deviation of that feature across the dataset. Secondly, PCA is a linear decomposition of data and thus not applicable in some cases (e.g., when effects are multiplicative) [14]. When applied to analyze a non-linear dataset, PCA may fail. Thirdly, standard PCA only supports batch processing, meaning that all data must be loaded into memory at once. To address this limitation, incremental PCA was developed to enable minibatch processing. In this approach, the algorithm processes small, randomly sampled subsets of the data (i.e., minibatches) in each iteration, which reduces memory requirements and computational cost. However, because the principal components are estimated from partial data rather than the full dataset, the resulting components may be slightly less accurate than those obtained from standard PCA.

As mentioned, PCA is a linear method. Therefore, to analyze datasets that are not linearly separable, kernel PCA [22] is introduced, where kernel means that the algorithm uses a function that measures the similarity between two data points, corresponding to an inner product in a transformed feature space. Compared to PCA, kernel PCA is able to make a non-linear projection of the data points, thus providing a clearer presentation of information by unfolding the dataset. When mapping the kernelized PCA back to the original feature space, there will be some small differences, even if the number of components defined is the same as the number of original features. The difference can be reduced by choosing a different kernel function or by adjusting the implementation, as suggested by Pedregosa et al. [23]. In particular, they recommend tuning the hyperparameter alpha, which is used when learning the inverse transformation. This step relies on ridge regression, where a smaller value of alpha typically improves the reconstruction but can also make the model more sensitive to noise and increase the risk of overfitting.

PCA has been applied to dimensionality reduction of spectral data (e.g., [24,25,26,27,28]), light curves (e.g., [29]), catalogs (e.g., [30]), and images (e.g., [11]).

2.2. Non-Linear Methods

There are also non-linear methods aiming to process non-linear datasets. The discussed algorithms are multi-dimensional scaling and isometric feature mapping, locally linear embedding, and t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding.

2.2.1. Multi-Dimensional Scaling and Isometric Feature Mapping

Multi-dimensional scaling (MDS) [31] is a dimensionality reduction algorithm frequently compared to PCA. James O. Ramsay [32] gives the core theory behind MDS. MDS aims to preserve the disparities, which are the pairwise distances computed in the original high-dimensional space. Given a dataset, MDS first computes the pairwise distances between all pairs of points. It then reconstructs a low-dimensional representation of the data that minimizes a quantity known as stress (also known as the error). Stress is defined as the sum of the differences between the original pairwise distances and the corresponding distances in the low-dimensional embedding. There are various ways to define disparities. For example, metric MDS (also known as absolute MDS) defines disparity as a function of the absolute distance between two points. In contrast, non-metric MDS [33,34] preserves the rank order of the pairwise distances. That is, if one pair of points is farther apart than another pair of points, the same relative ordering is maintained in the low-dimensional embedding space2.

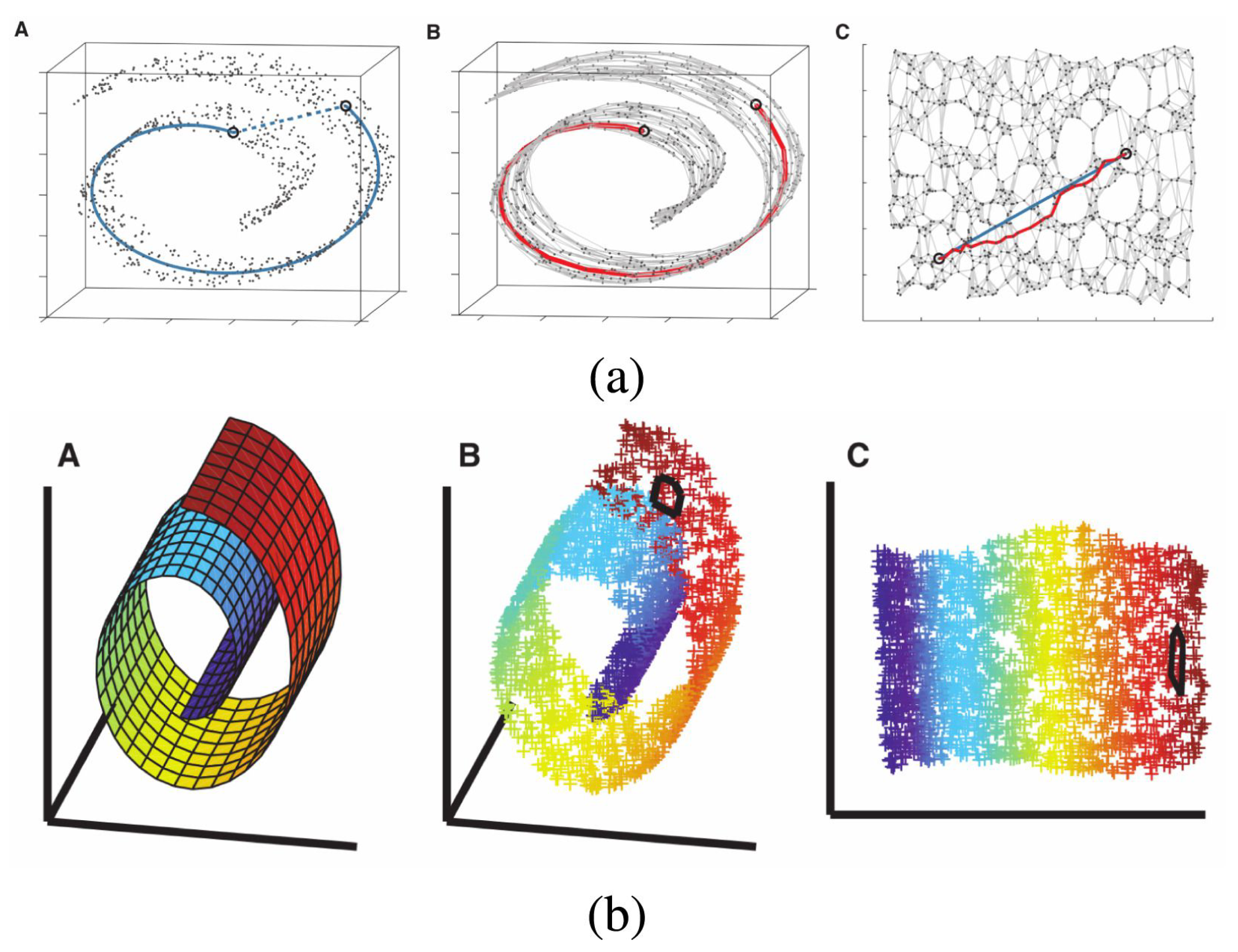

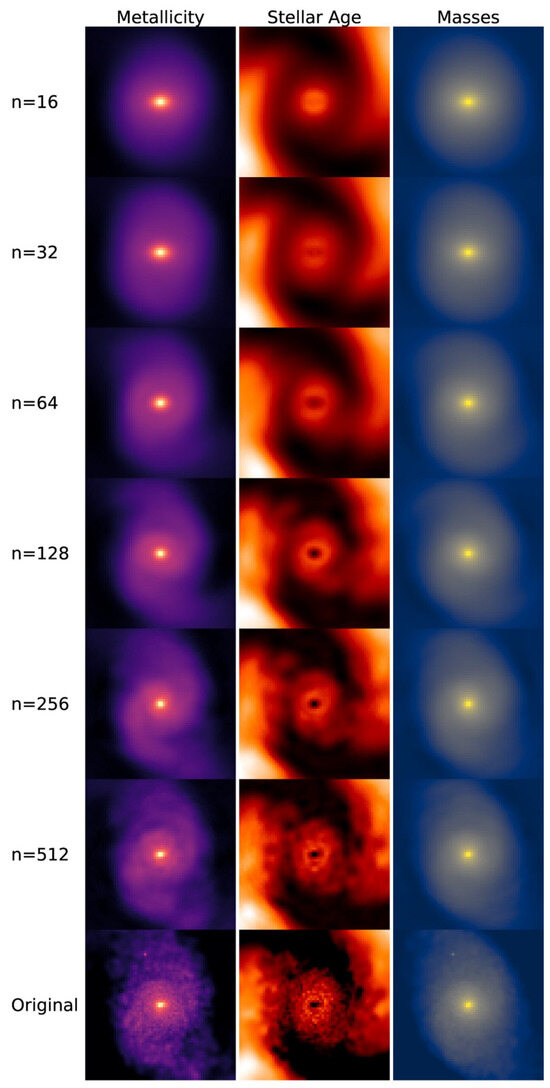

Isometric feature mapping (Isomap, [35]), an extension of MDS, is also used for non-linear dimensionality reduction. Unlike PCA and classical MDS, which rely on Euclidean distances, Isomap uses geodesic distance. Specifically, Isomap first connects each point to its nearest neighbors based on Euclidean distance, constructing a neighborhood graph. The geodesic distance between two points is then approximated as the shortest path along this graph. In other words, Isomap approximates the geodesic curves lying on the manifold and computes the distance along these curves [16]. While MDS considers the distances between all pairs of points to define the shape of the data, Isomap only uses distances between neighboring points and sets the distances between all other pairs to zero, thus unfolding the manifold [16]. After constructing this new distance matrix, Isomap applies MDS to the resulting structure. Figure 3a shows an example of how a three-dimensional ‘Swiss roll’ manifold is unfolded to two dimensions by Isomap.

Figure 3.

Example of dimensionality reduction with (a) Isomap and (b) LLE (Section 2.2.2), showing how the two algorithms unroll a ‘Swiss roll’ manifold. Each panel contains three mini-plots labeled A–C. In (a), A shows the geodesic distance between two points on the manifold (blue line), B shows the corresponding distance along the neighborhood graph (red line), and C presents the resulting low-dimensional embedding after unfolding. In (b), A–C correspond to the same stages, with color used to represent the local structure of the manifold. The change in the circled area between B and C illustrates how LLE preserves local structure during the unfolding. The figure is taken from Fotopoulou [15], licensed under CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Bu et al. [36] point out that Isomap is more efficient than PCA in feature extraction for spectral classification. However, Ivezić et al. [16] state that Isomap is more computationally expensive compared to locally linear embedding (see Section 2.2.2). The book also lists various algorithms that can reduce the amount of computation, such as the Floyd–Warshall algorithm [37] and the Dijkstra algorithm [38].

MDS has been used to reduce the dimension of catalogs (e.g., [12]), while Isomap has been used to reduce spectral data (e.g., [36,39,40]) and latent spaces generated by neural networks (see Section 2.3.2) (e.g., [41]).

2.2.2. Locally Linear Embedding

Locally linear embedding (LLE, [42]) is an algorithm for dimensionality reduction that preserves the data’s local geometry [16]. For each data point, LLE identifies its k nearest neighbors and produces a set of weights that can be applied to the neighbors to best reconstruct the data point. The weight indicates the geometry defined by the data point and its nearest neighbors. The weight matrix W is find by minimizing the error , where X denotes the original dataset [16]. From the weight matrix, LLE finds the low-dimensional embedding Y by minimizing the error [16]. The solution to the two equations can be found by imposing efficient linear algebra techniques: some computations are performed to find another matrix , and eigenvalue decomposition is performed on , producing the low-dimensional embedding. Figure 3b shows an example of how a three-dimensional ‘Swiss roll’ manifold is flattened to two dimensions by LLE.

A shortcoming of LLE is that the direct eigenvalue decomposition becomes expensive for large datasets [16]. According to Ivezić et al. [16], this problem can be circumvented by using iterative methods, such as Arnoldi decomposition, which is available in the Fortran package ARPACK [43]. LLE is sometimes compared with PCA. On the one hand, LLE does not allow the projection of new data, which would impact the weight matrix and subsequent computations. This means that when LLE is applied to reduce new data of the same type, the training process needs to be repeated, unlike some other methods (e.g., PCA) that allow direct application of a trained template to new data. On the other hand, Vanderplas and Connolly [44] show that LLE leads to improved classification, although Bu et al. [45] point out that the usage of LLE is more specific than PCA and thus more limited.

LLE has been applied to dimensionality reduction of spectral data (e.g., [44,46,47,48]) and light curves (e.g., [7,49]).

2.2.3. t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding

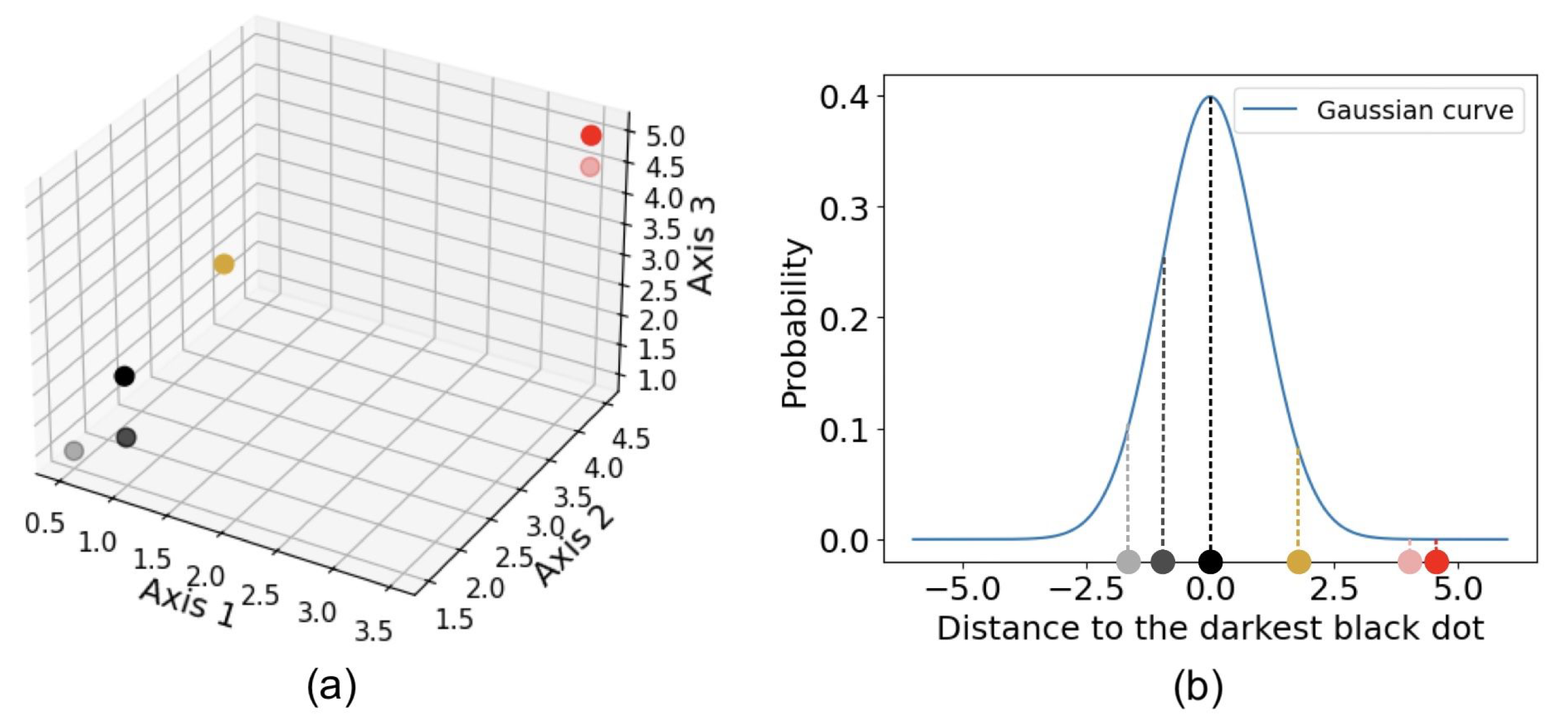

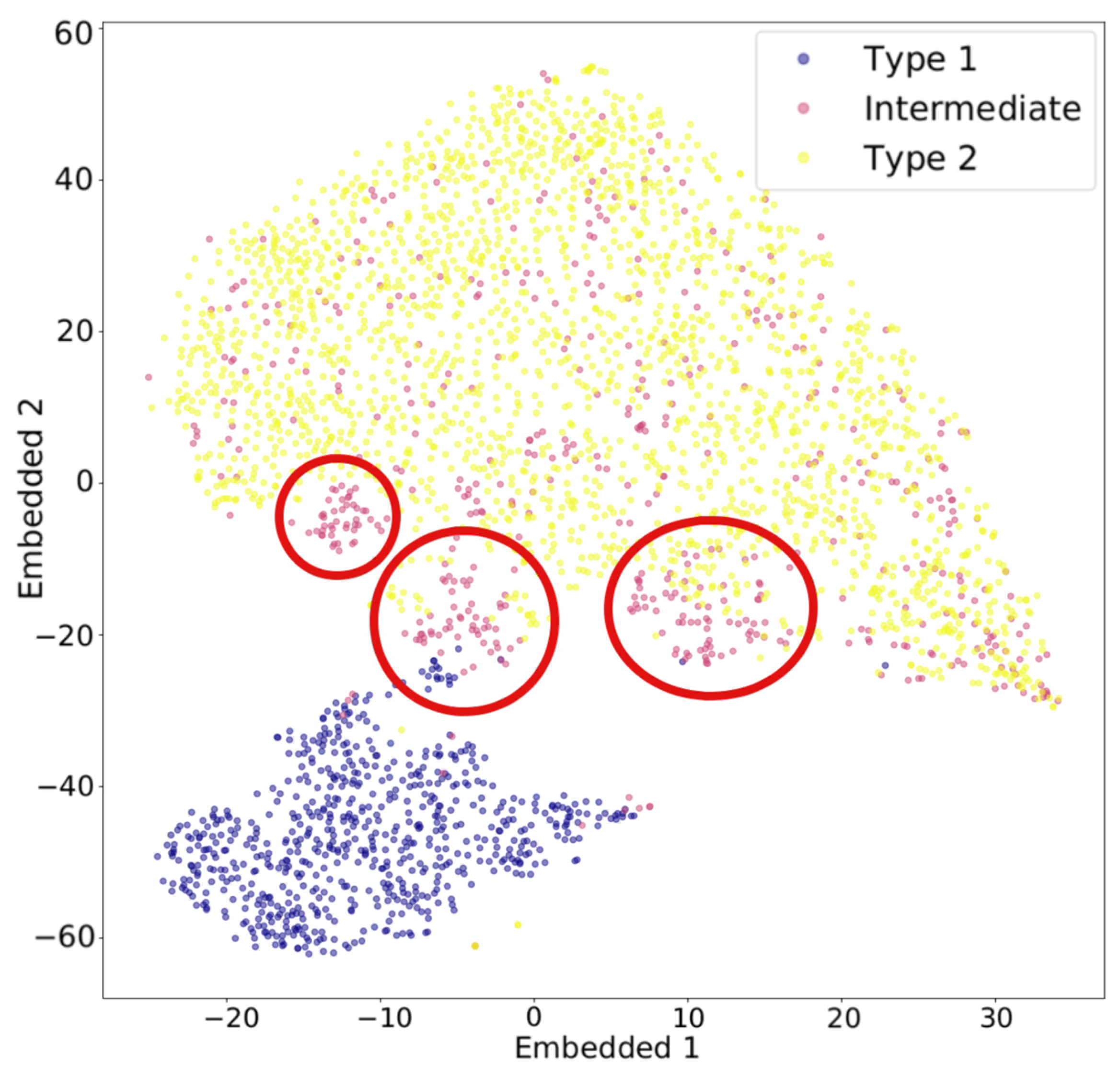

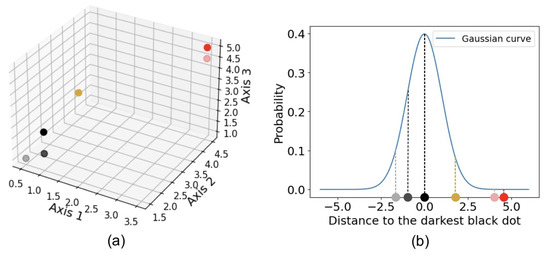

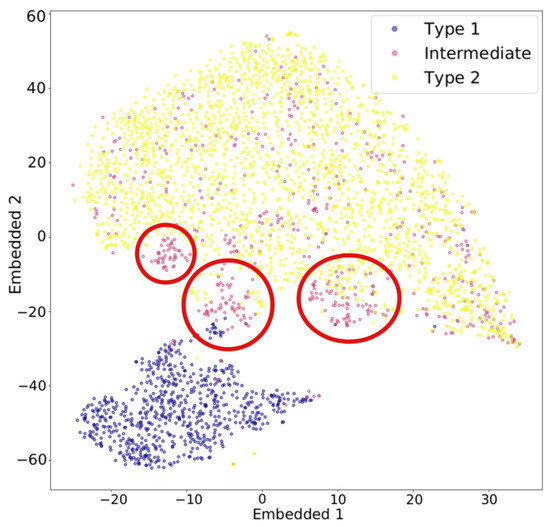

t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) is another widely used algorithm for dimensionality reduction. Stochastic neighbor embedding, developed by Hinton and Roweis [50], forms the basis of t-SNE, and the t-distribution variant was introduced by van der Maaten and Hinton [51]. t-SNE converts the affinities—similarities between two points, usually measured by pairwise distances in a high-dimensional space—into Gaussian joint probabilities [23]. Figure 4 illustrates how t-SNE calculates affinity using a three-dimensional dataset shown in (a). For example, the distance from any point to the darkest black dot is computed, and t-SNE calculates the corresponding conditional Gaussian probabilities, as shown in (b). Perplexity, a hyperparameter that reflects the effective number of nearest neighbors considered when computing conditional probabilities, determines the width of the Gaussian distribution around each point. Because of normalization, the probabilities between any two points, a and b, can differ depending on whether the perspective is from a to b or from b to a. The joint probability is typically defined as the average of these two probabilities. The probabilities are further represented by Student’s t-distributions [23]. When high-dimensional data is projected into a low-dimensional space, the probability distribution is maximally preserved [14]. That is, t-SNE uses a joint Gaussian distribution to model the likelihood of data in the high-dimensional space, which is then mapped to a Student’s t-distribution in the low-dimensional space [15]. Figure 5 illustrates an example of t-SNE applied to spectral data. Each spectrum can be represented as a vector whose dimensionality equals the total number of wavelength bins. The color of each dot indicates the cluster it belongs to, as determined by a given clustering algorithm, while the pink dots represent intermediate data points. The t-SNE projection reveals that the circled groups of pink data points lie near the boundary between the two main clusters, suggesting the presence of possible intermediate-type subgroups.

Figure 4.

Example of how t-SNE measures the affinity between two points, demonstrated using a three-dimensional dataset, shown in (a). For example, the distance from any dot to the darkest black dot is computed, and the corresponding probability is determined using a Gaussian kernel, as shown in (b).

Figure 5.

Example of dimensionality reduction with t-SNE applied to spectral data. The red circle marks the region in which intermediate-type subgroups are likely to be found. Figure is taken from Peruzzi, T. et al. [52], licensed under CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

As discussed, Isomap and LLE can learn a single continuous manifold. However, in many cases, there is more than one manifold. Due to its design, t-SNE can learn different manifolds in the dataset. t-SNE also mitigates the issue of overcrowding at the center, a common problem in many dimensionality reduction algorithms where points cluster densely, by using a t-distribution with heavier tails than a Gaussian distribution [15]. This allows distant points to be spread out more effectively in the lower-dimensional space. Nonetheless, t-SNE has some disadvantages. Similarly to LLE, t-SNE does not allow the projection of new data points once the manifold has been learned. t-SNE is non-deterministic, which means it generates different results each time it runs. t-SNE is also very computationally expensive. To accelerate computation, the Barnes–Hut approximation [53] may be adopted, but the embedding manifolds applicable are limited to two or three dimensions. t-SNE may not preserve the global structure of the dataset. To solve this problem, one may select initial points by PCA.

t-SNE has been applied to reduce the dimensionality of catalogs (e.g., [54,55,56], which are, respectively, quasar parameters, line ratios, and chemical abundance), spectral data [57], photometry data [58], and light curves [8,59].

2.3. Neural Network-Based Dimensionality Reduction

This section introduces two neural network algorithms: the self-organizing map and the auto-encoder. Both techniques transmit outputs between interconnected neurons that mimic the human brain, performing tasks such as clustering, dimensionality reduction, and outlier detection or producing information that can be used as input for other algorithms.

2.3.1. Self-Organizing Map

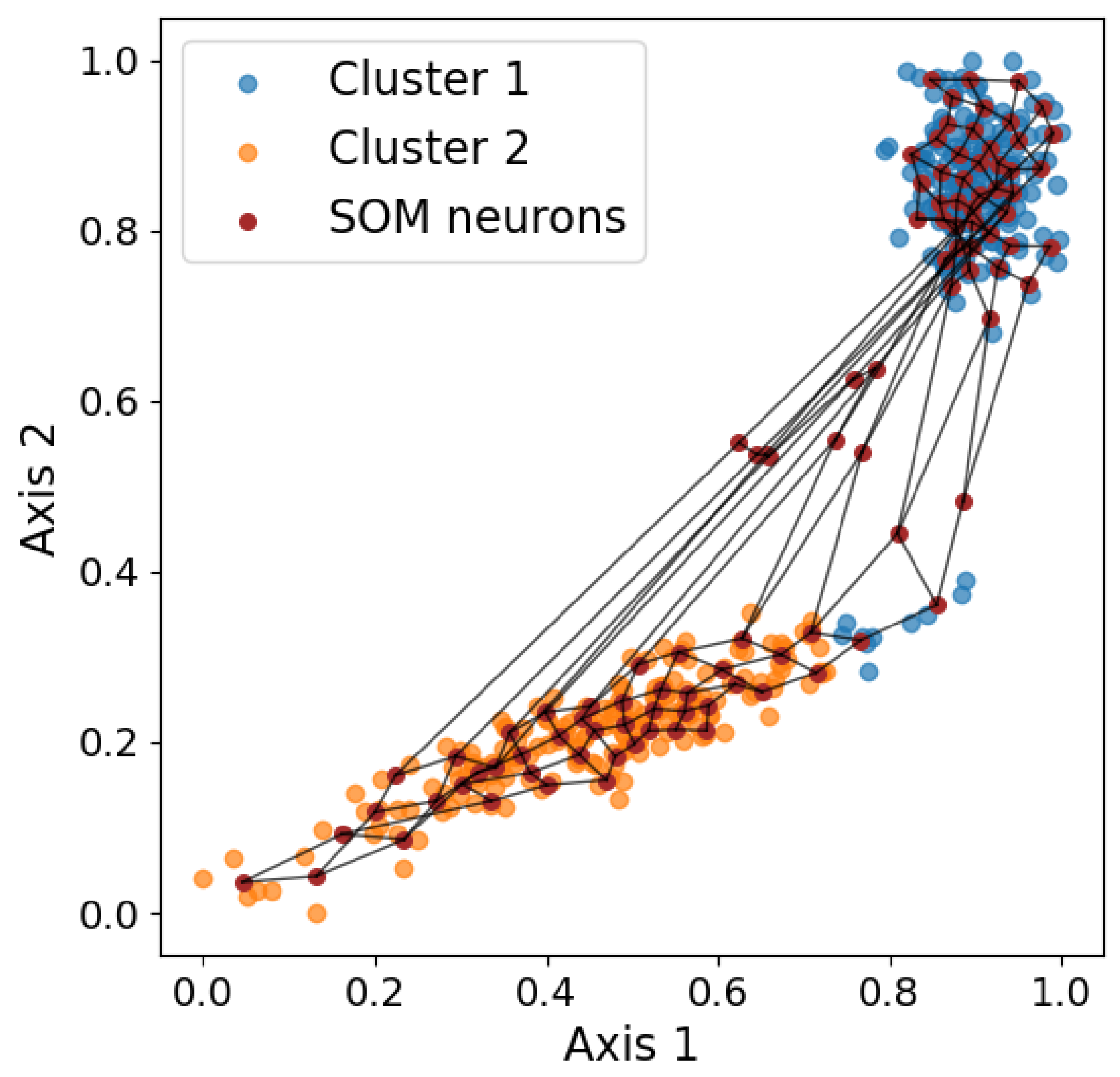

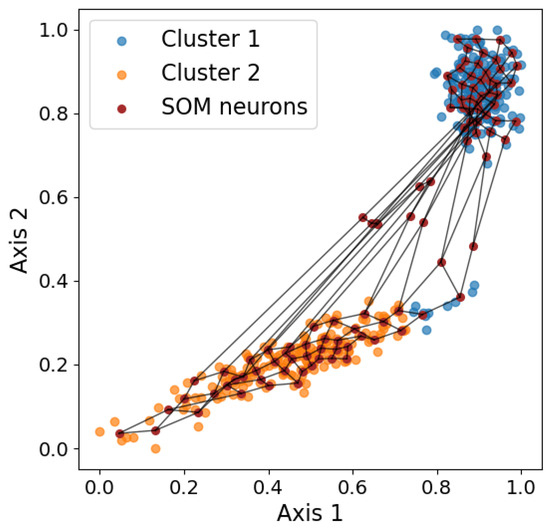

The self-organizing map (SOM, [60]) is a neural network technique typically used for visualization by dimensionality reduction, but the SOM can also be applied in clustering and outlier detection. The SOM uses competitive learning, which is a form of unsupervised learning where nodes compete to represent input data. When used for dimensionality reduction, the output is almost always two-dimensional. The number of output nodes is first defined manually, usually . Having more data points indicates that more output nodes, and thus a higher k, are needed. Each node is assigned a weight vector, which can be viewed as a coordinate in the input space that the node is responsible for. Therefore, the weight has the same dimensionality as the input space. Then, for each data point, the SOM updates the weights of the closer nodes so the nodes become even closer to the data point. That is, the closest nodes are dragged the most, while the furthest nodes are not dragged much. The process of updating each node is iterated for the weight vectors to converge. Figure 6 shows a visualization of the final result. In the end, each data point can be assigned to a winning neuron, which is the node whose weight vector is closest to the data point in the input space. Therefore, each data point can be represented by the x and y coordinates of the corresponding winning neuron. When used in clustering, the number of nodes is set to be the known number of clusters, and the data points with the same winning node belong to the same cluster. The SOM performs clustering by partitioning the space, producing notably different results compared to the other clustering algorithms discussed previously, as discussed in Section 3.7.

Figure 6.

Visualization of the SOM grid overlaid on the two-dimensional input data. The purple dots represent neuron weights, and the black lines connect neighboring neurons, illustrating how the SOM captures the underlying data topology.

Notably, the SOM performs a simplification of data, not only reducing the dimensionality but also changing continuous data into discrete data. In other words, similar data points, corresponding to the same node, are presented by the same box in the map. Consequently, the SOM presents the distribution of data in the 2D space clearly, but the resulting output may not be used for further data mining because most of the information is lost. Another disadvantage is that, like other neural networks, the SOM is also computationally expensive.

The SOM has been applied to photometric and spectroscopic data (e.g., for dimensionality reduction in [61,62,63,64]), catalogs (e.g., for dimensionality reduction and clustering in [65]), and light curves (e.g., for clustering in [66,67]).

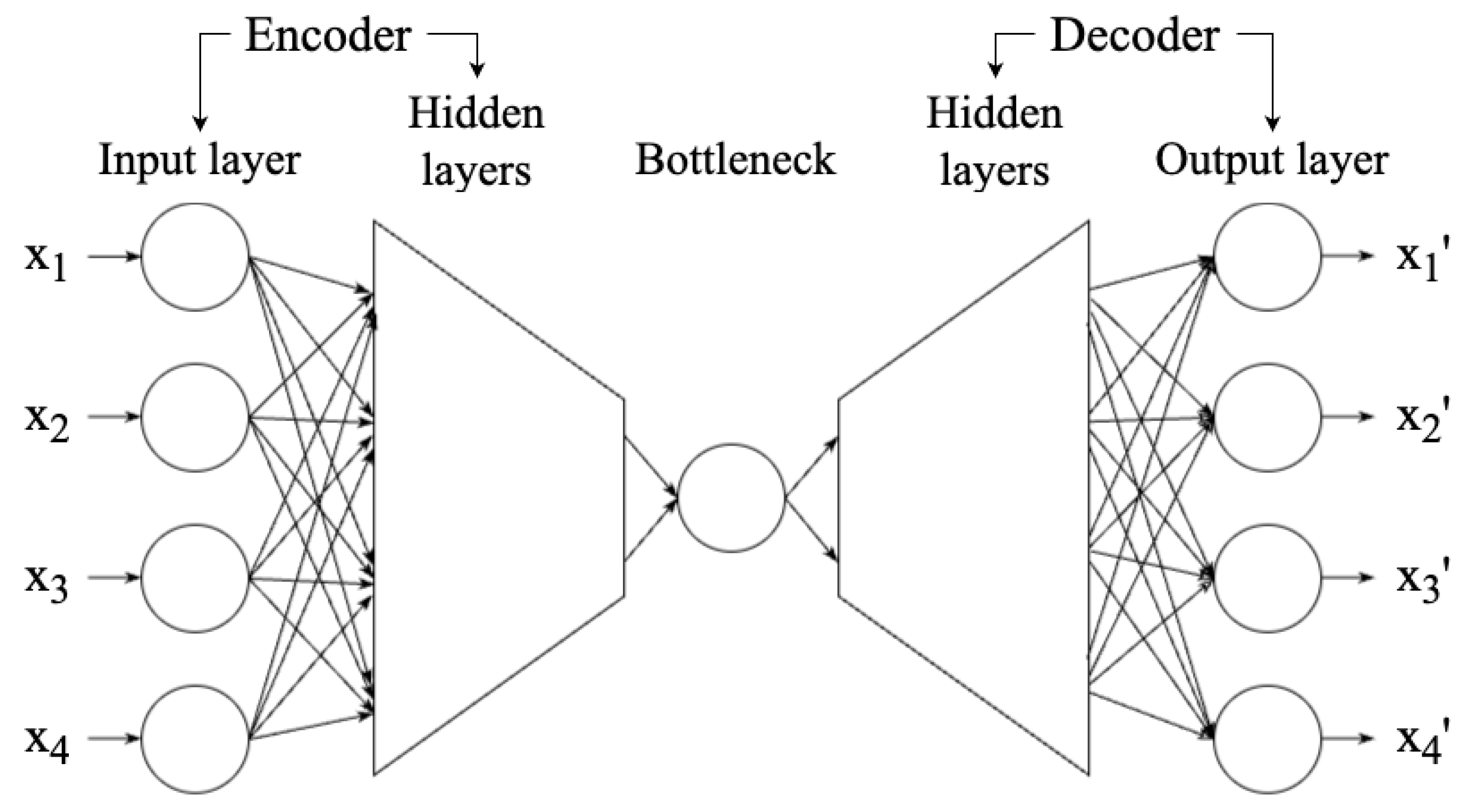

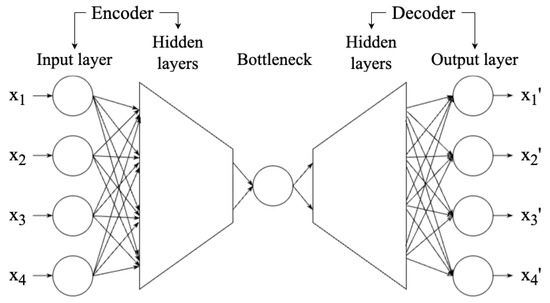

2.3.2. Auto-Encoder and Variational Auto-Encoder

An auto-encoder (AE, [68,69]) is a neural network technique that aims to reduce a high-dimensional dataset to a low-dimensional representation (also known as latent space) so that the dataset reconstructed from the representation is highly similar to the original dataset. Therefore, an AE can be used in dimensionality reduction. As shown in Figure 7, an AE network can be divided into three components: encoder, bottleneck, and decoder. The encoder consists of multiple layers, with the same or decreasing number of neurons in each layer, until the information reaches the bottleneck—the most compressed representation of data, with the lowest dimensionality in the AE, only preserving the significant features. The bottleneck is thus the output of the encoder. If the number of neurons of the bottleneck is less than the dimensionality of the data, then the AE compresses the data [16]. The decoder works to reconstruct the data from the bottleneck. Once the encoder and decoder are trained, new data can be entered without retraining.

Figure 7.

Structure of the AE, showing the input and output layers, encoder and decoder, and bottleneck. A shallow neural network has one or two hidden layers, while deep learning models have three or more. The figure is adapted from Fotopoulou [15], which was adapted from Kramer [68], licensed under CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Similarly to the SOM, AEs can also be used for denoising, other than dimensionality reduction. However, the AE is extremely computationally expensive and may require a GPU to run. Another disadvantage of the AE is that the AE does not guarantee a continuous interpolation3 of new data because of the compactness of the latent space [16]. Therefore, the variational auto-encoder (VAE, [70]) was introduced to solve the interpolation issue. The VAE imposes a Gaussian prior, mapping each data point to a probability distribution in the latent space rather than a single point. Data for reconstruction is then sampled from this distribution, mitigating issues related to interpolation and overfitting.

The AE has been be applied to compress and decompress images (e.g., [71,72]) and catalogs (e.g., [73]) and to denoise time series (e.g., [74]). The VAE has been applied for anomaly detection of spectroscopic data (e.g., [75]) and time series data (e.g., [76]).

2.4. Examples of Applications of Different Dimensionality Reduction Algorithms

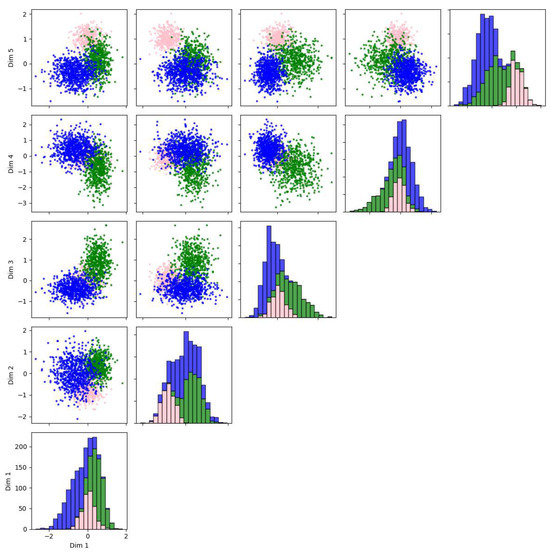

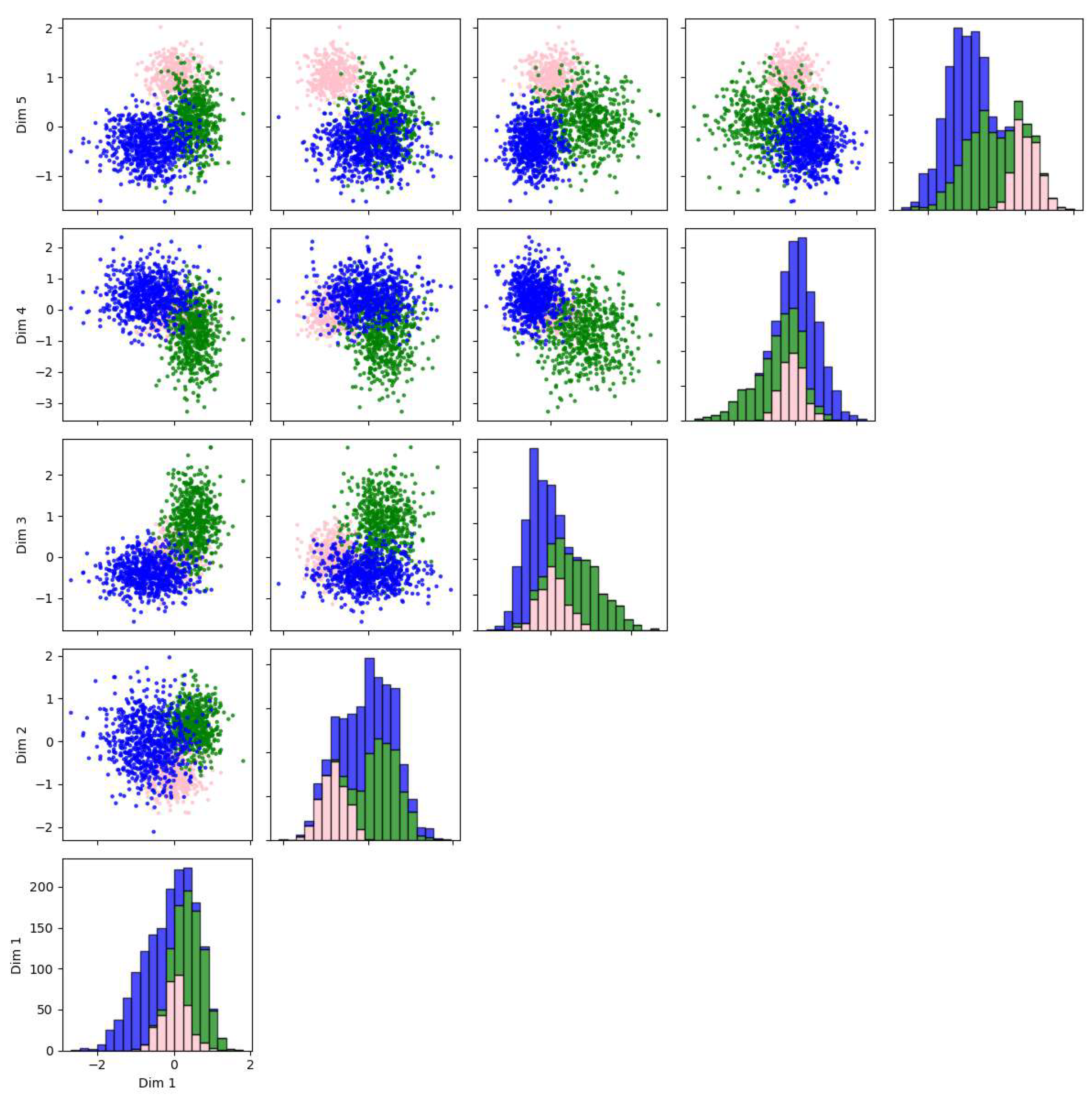

In this section, we present examples of applying different dimensionality reduction algorithms to real observational datasets in astronomy. The dataset consists of five-dimensional astrometry data for 1254 stars, including right ascension, declination, distance, proper motion in right ascension, and proper motion in declination. The data is provided by SIMBAD [77]. We used Strasbourg Astronomical Data Center (CDS, [78]) for the criteria query of data. The criteria we used were , and spectral types being dimmer than or equal to ‘O’. The data is pre-processed by normalizing, removing outliers, and then re-normalizing to adjust the scale based solely on the inlier data, retaining 1113 data points.

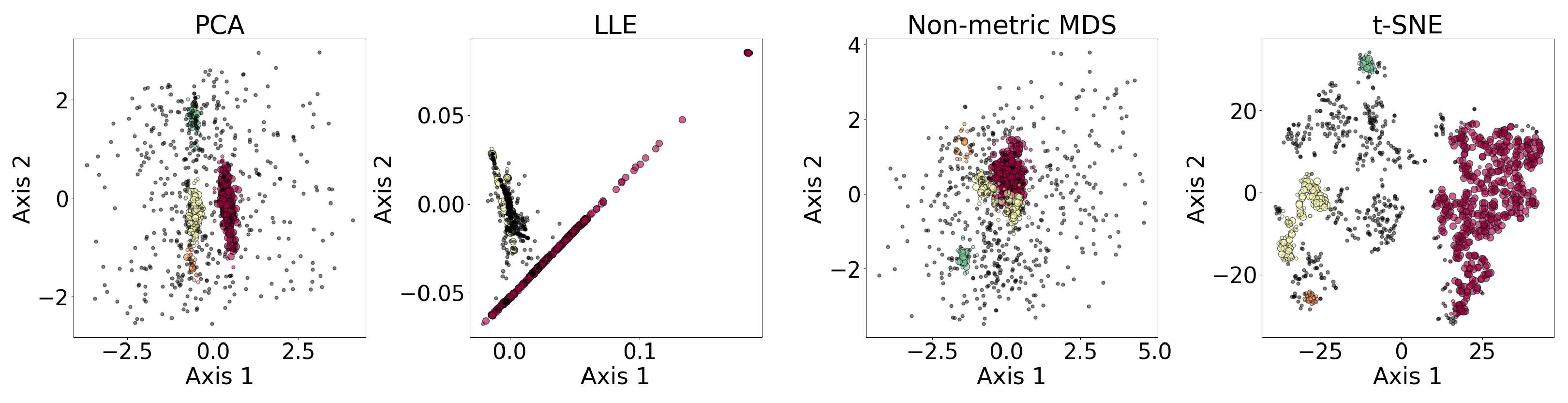

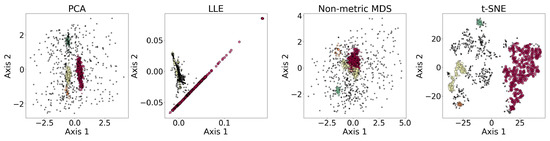

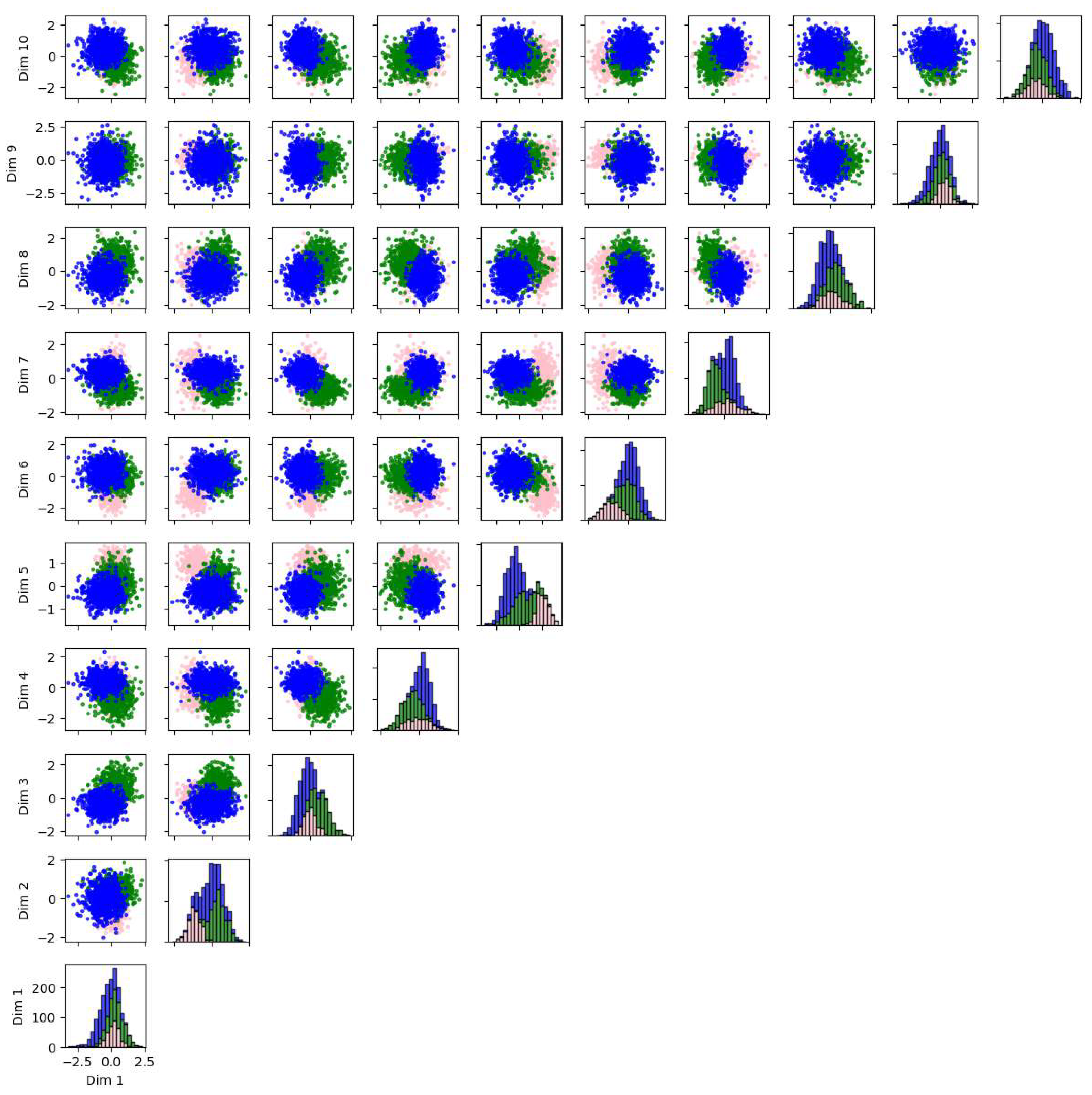

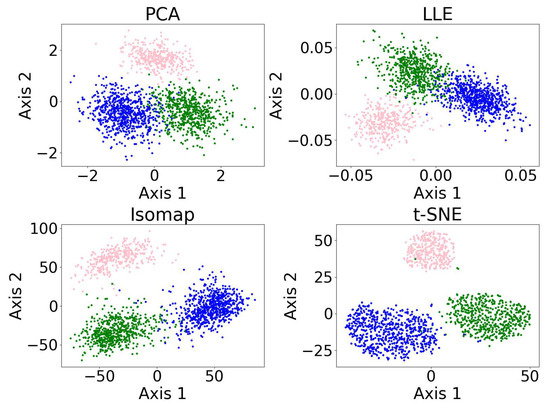

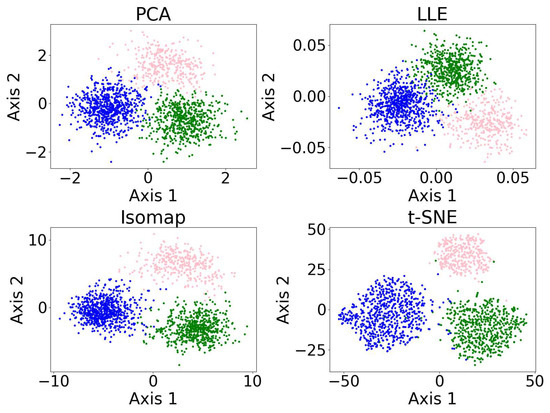

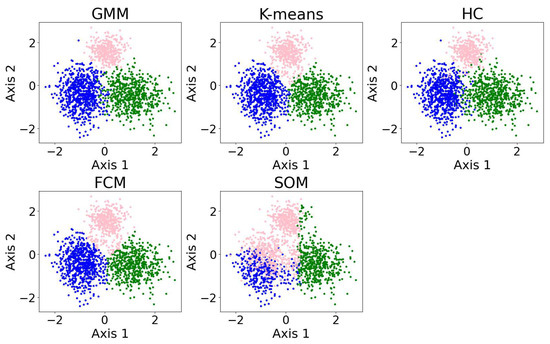

Figure 8 shows the results of the dimensionality reduction algorithms, including PCA, LLE, non-metric MDS, and t-SNE. The five-dimensional dataset is clustered with DBSCAN (see Section 3.4) before being reduced to two dimensions. PCA is linear, while the other three algorithms are non-linear. PCA and t-SNE project the clusters relatively separately, suggesting they may be suitable for dimensionality reduction prior to clustering. In contrast, LLE and MDS—especially LLE—tend to project clusters with overlap, which may impair clustering performance. LLE’s behavior may be further amplified by its sensitivity to outliers and its reliance on local neighborhood structure.

Figure 8.

Results of the dimensionality reduction algorithms applied to the same five-dimensional dataset. The algorithms include PCA, LLE, non-metric MDS, and t-SNE. The five-dimensional dataset is clustered with DBSCAN before being reduced to two dimensions, where different colors represent different clusters, and the black dots represent the outliers. This figure illustrates how the clusters are distributed under different dimensionality reduction algorithms.

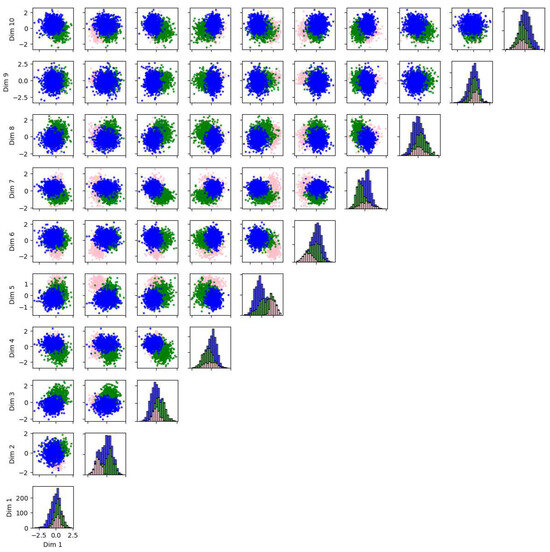

We also applied PCA, Isomap, LLE, and t-SNE to reduce the dimensionality of 5-dimensional and 10-dimensional synthetic datasets described in Appendix A.1. The results and evaluations are presented in Appendix A.2. We find that t-SNE provides the greatest separation between clusters. When used for dimensionality reduction prior to clustering, t-SNE and Isomap achieve higher accuracy, while PCA and Isomap show greater robustness. LLE requires fine-tuning of the parameters and shows lower accuracy and robustness compared to the other algorithms.

2.5. Benchmarking of Dimensionality Reduction Algorithms

In this section, we present a benchmarking study of dimensionality reduction algorithms. Table 1 summarizes each algorithm’s run time, classic applications, novel applications, popular datasets, strengths, weaknesses and failure modes, and overall evaluation. We also provide a summary of literature-based comparisons of algorithm performance.

Table 1.

Benchmarking table of the dimensionality reduction algorithms.

Table 2 presents the result of a focused search, showing the number of refereed astronomy papers in the SAO/NASA Astrophysics Data System (ADS) that applied each algorithm to different types of data from 2015 to 2025. These results offer insight into which algorithms are most widely used for specific types of analyses, reflecting current trends and preferences in the field.

Table 2.

Result of a focused search, showing the number of refereed astronomy papers in the ADS that applied each dimensionality reduction algorithm to different types of data from 2015 to 2025. The rows are ordered by the sum of all algorithm applications, with higher totals ranked first. The box corresponding to the most popular application for each algorithm is highlighted in yellow. We do not report counts for cases in which latent spaces are used as inputs to the SOM or AE because any focused search for such usage would also return studies where the latent spaces produced by the SOM or AE were subsequently fed into other algorithms, making the numbers ambiguous.

Multiple studies have compared different linear and non-linear dimensionality reduction algorithms, most using spectral data. A majority of the studies [36,39,48,87] report that Isomap outperforms PCA for the dimensionality reduction of spectra from stars, massive protostars, and galaxies. In particular, Daniel et al. [48] show that, compared to PCA, LLE may better preserve information crucial for classification in a lower-dimensional projection. Similarly, Vanderplas and Connolly [44] show that LLE outperforms PCA for the classification of galactic spectra. They also point out that PCA performs better for continuum spectra than for line spectra. On the other hand, Kao et al. [46] suggest that PCA outperforms Isomap, LLE, and t-SNE when XGBoost or Random Forest is used for classification; in this example, quasar spectra are classified. When applied to catalogs, Zhang et al. [55] suggest that t-SNE outperforms PCA at visualizing galaxy clusters given high-dimensional datasets. When applied to images, Semenov et al. [118] suggest that LLE outperforms PCA, Isomap, and t-SNE; this example uses galaxy images.

In terms of the neural network-based algorithms AE and SOM, we find that the AE has wider applications in general. The AE can be used for dimensionality reduction and feature extraction, data compression, anomaly detection and denoising, and generative modeling; meanwhile the SOM is mostly used for dimensionality reduction and clustering only. This is due to the AE having a more complex architecture than the SOM, which allows the AE to learn complex, non-linear features. However, this complexity makes the AE more computationally demanding and typically slower to train, often requiring GPU for efficient training. In contrast, the SOM is CPU-friendly, though less flexible in application. The VAE is even more computationally expensive than the traditional AE, but it helps mitigate overfitting and improves generalization of the model, as stated in Section 2.3.2. In modern applications, most AEs and VAEs applied to images are implemented with convolutional layers, so the nomenclature ‘AE’ commonly includes what would traditionally be called the CAE. The CAE is a variant of the AE that combines a convolutional neural network (CNN) with an AE, using convolutional layers instead of connected layers. The CAE is best viewed as an architectural choice within the broader AE family rather than a distinct network structure. By far, there is a higher number of applications of VAEs in astronomy compared to CAEs. By conducting focused research in the ADS regarding the application of each algorithm in astronomy in the most recent 10 years (i.e., from 2015 to 2025), we found that SOM is more often applied to analyze photometric data, while the AE, VAE, and CAE are usually used on images.

In terms of the performance of the AE and SOM, they are not often directly compared in published studies; instead, they are frequently implemented together. Multiple studies apply the VAE for denoising and subsequently implement the SOM to study pulses of the Vela Pulsar [119,120,121]. Amaya et al. [122] use an AE for dimensionality reduction of solar wind data and then apply an SOM to cluster the latent vectors produced by the AE. Ralph et al. [71] apply the CAE and SOM to cluster radio-astronomical images: the CAE first converts the images into feature vectors, the SOM further reduces the CAE latent space, and K-means is used for clustering. Teimoorinia et al. [123] use a Deep Embedded SOM (DESOM, [124]) for clustering large astronomical images. The DESOM embeds the SOM within the bottleneck of the AE, resulting in improved classification performance and shorter training time [123].

There are various answers regarding which algorithm provides the most interpretable low-dimensional projection. As suggested by the Strengths column of the benchmarking Table 1, the choice of algorithm depends on which aspect of the data one aims to reveal or investigate. PCA is linear, so the results are more intuitive. Isomap, LLE, and t-SNE are non-linear, projecting similar data points closely, which makes them more suitable for displaying different clusters, where the clusters may overlap in a PCA projection. The SOM is often used for preliminary clustering and low-dimensional visualization, while AEs are commonly used for dimensionality reduction aimed at learning compressed latent representations that capture non-linear structure, and they are also used as a component in generative models.

Some hybrid models (Section 5) combine multiple dimensionality reduction algorithms to produce the most interpretable and useful projections.

3. Clustering

Given a dataset, we may be interested in classifying it into groups so that each group contains similar data. Unsupervised clustering algorithms are designed to accomplish this task without the need for human-provided labels. This section introduces various clustering algorithms, including the Gaussian mixture model, the K-means algorithm, hierarchical clustering, density-based spatial clustering of applications with noise and its hierarchical variant, and fuzzy C-means clustering. These algorithms group datasets into clusters by either iteratively estimating functions that represent the clusters, expanding clusters outward from core data points, or progressively merging or splitting clusters.

3.1. Gaussian Mixture Model

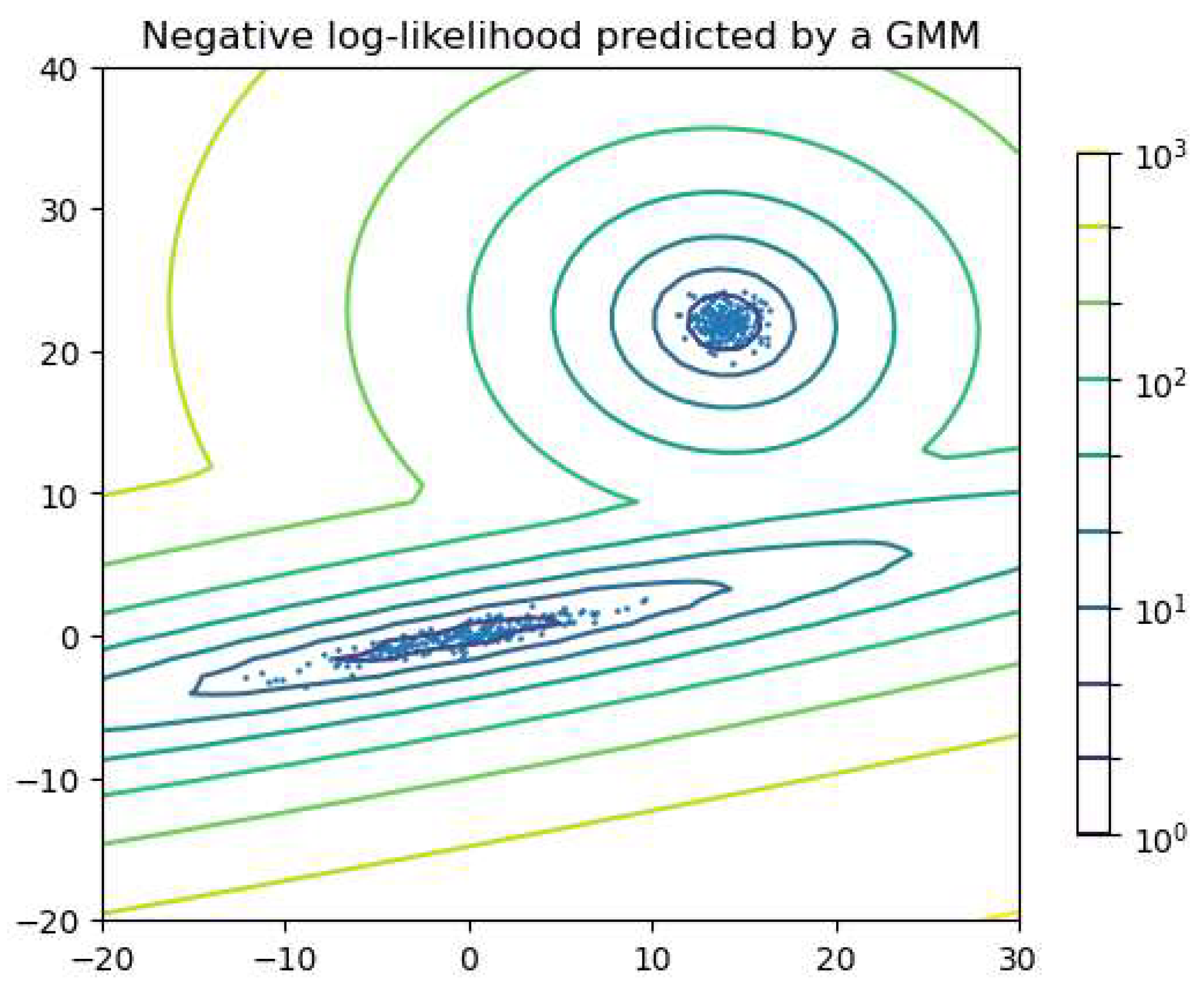

The Gaussian mixture model (GMM) is widely used to group objects or data into clusters. The GMM is a probabilistic model that assumes the data distribution can be represented as a weighted sum of multiple Gaussian functions, where each function has an associated weight that sums to one across all components. Each Gaussian function is treated as a component, allowing objects to be clustered based on which component assigns the highest probability to each data point. The expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm is the iterative process of fitting Gaussian functions to the data. For GMMs in particular, it is common to initialize the model parameters using K-means (Section 3.2), which provides a reasonable starting estimate for the component means. In the E-step, EM calculates the probability of generating each data point using Gaussian functions with the parameters. In the M-step, EM adjusts the parameters to maximize the probability. The E- and M-steps are repeated until convergence criteria are met, such as a sufficiently small change in log-likelihood. The GMM assumes the clusters to be convex-shaped; i.e., each cluster has a single center and follows a relatively ellipsoidal distribution around it. Figure 9 shows an example in which two components are considered for clustering. The lines can be seen as the contour line of the sum of the two Gaussian functions.

Figure 9.

Example of clustering with the GMM, where two components are considered for clustering. The lines show the equi-probability contours of the model, making a contour plot of the sum of the two Gaussian functions. Figure generated using code adapted from the scikit-learn documentation: scikit-learn.org (https://scikit-learn.org/1.1/auto_examples/mixture/plot_gmm_pdf.html).

The GMM assumes the number of components is known, though this is often not the case in practice. As a result, the users may either apply the Bayesian information criterion (BIC, [125]) to determine the number of components or use the variational Bayesian GMM (VBGMM, based on the variational inference algorithm of Blei and Jordan [126]), which does not fix the number of components. The BIC is a score computed from a grid search over different numbers of components and the shapes of their distributions (i.e., the types of covariance). The combination with the lowest BIC score indicates the best fit to the data distribution and is used for the GMM. The VBGMM requires more hyperparameters than the standard EM-based GMM. In particular, the choice of prior on the mixture weights plays a central role. When using a Dirichlet distribution as the prior, the maximum number of components is fixed, and the concentration parameter controls how weight is distributed across components: the lower the concentration parameter, the more weight is placed on fewer components [23]. In contrast, when the VBGMM is formulated with a Dirichlet process prior (often referred to as the DPGMM), the model is theoretically capable of using an unbounded number of components. In this case, the concentration parameter similarly regulates how many components are effectively used, with smaller values favoring fewer active components [23].

The GMM has been applied to cluster photometric data (e.g., [127,128]), spectroscopic data (e.g., [129]), catalogs (e.g., [130,131]), and scattered data (e.g., [132]). An example of an application of the DPGMM is the detection of the shape of open clusters [133].

3.2. K-Means

The K-means algorithm was developed by MacQueen [134] to partition N-dimensional objects into k clusters. The procedure of K-means can be summarized as follows. First, centroid initialization is applied. From the data, k initial centroids are picked, and each element is assigned to be in the same cluster as the closest centroid. Next, the centroids are updated by computing the mean position of all points assigned to each cluster. Based on the updated centroids, points are reassigned to the nearest centroid, and the centroids are recomputed. This process of assignment and centroid update is repeated iteratively until convergence, at which point the centroids minimize the in-cluster sum of squares, i.e., the sum of squared distances between each point and its cluster centroid.

K-means has several limitations. Similarly to the GMM (Section 3.1), K-means requires prior knowledge of the number of clusters. This issue can be mitigated by testing different numbers of clusters and selecting the one at which the distortion curve4 begins to level off, indicating diminishing returns from adding more clusters [6], or by using a large number of clusters and discarding small clusters when the data allows [1]. Another limitation is K-means’ sensitivity to centroid initialization. One common approach is to repeat the computation for different initializations and select the result that produces the smallest in-cluster sum of squares, as demonstrated by Panos et al. [3]. Alternatively, the K-means++ algorithm [135] improves the initial centroid selection by ensuring that centroids are initially well separated, which often leads to better clustering outcomes. Additionally, K-means assumes that clusters are convex-shaped, which may not hold for more complex data distributions.

The K-means algorithm has been applied to various types of data for clustering, including scattered data from catalogs (e.g., [6]), spectral data (e.g., [1,2,3]), and polarimetric data (e.g., [136]).

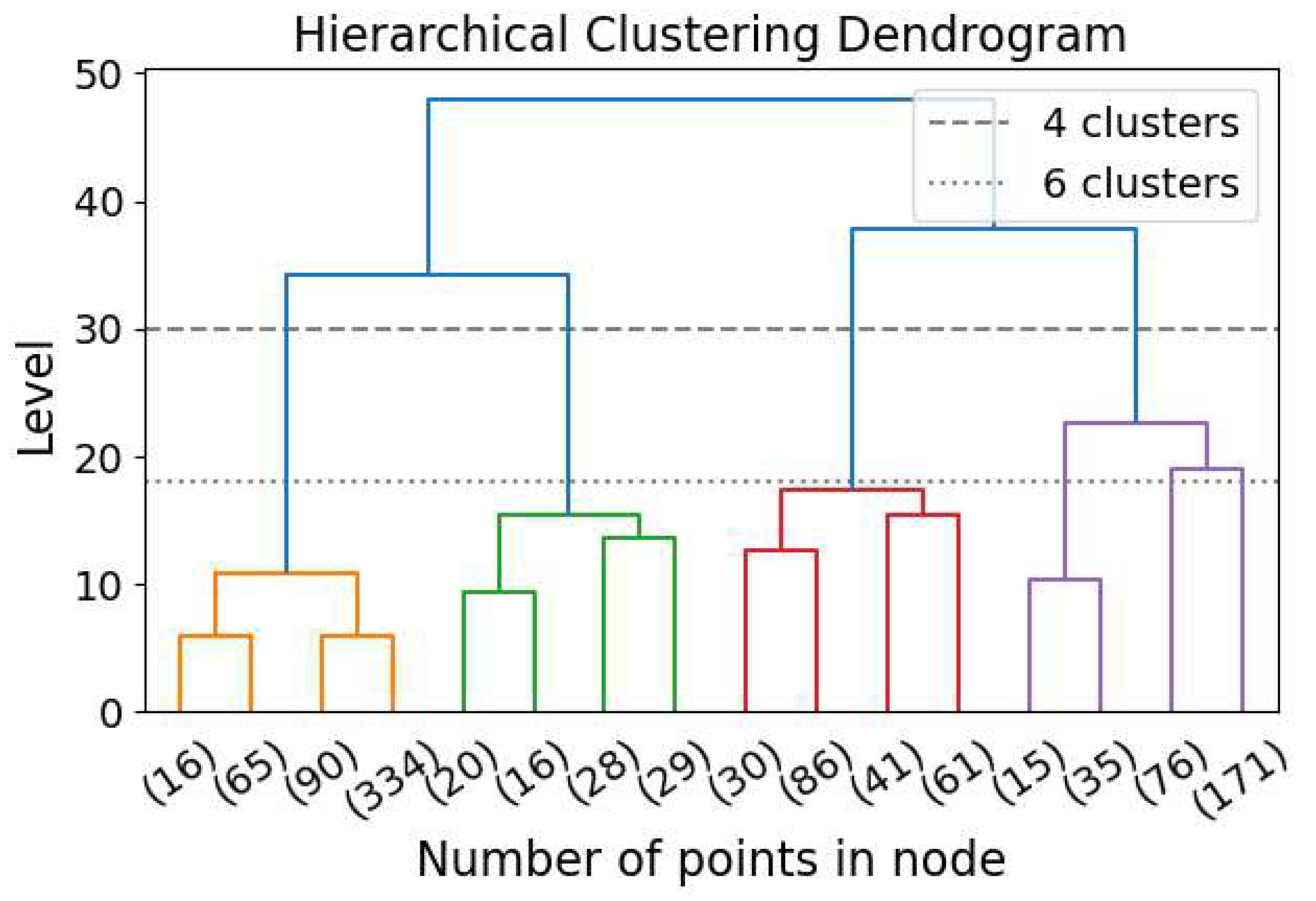

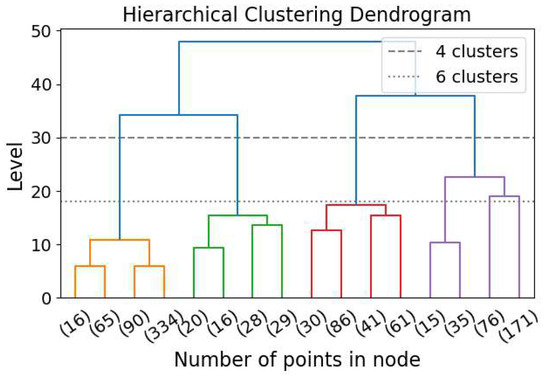

3.3. Hierarchical Clustering and Friends-of-Friends Clustering

Hierarchical clustering (HC) is a clustering algorithm that identifies clusters across all scales without requiring a specified number of clusters [16]. HC can be performed in a top-down (also known as divisive) or bottom-up (also known as agglomerative; [137]) approach. A diagram demonstrating the bottom-up clustering dendrogram is Figure 10. In the bottom-up approach, the N elements start as N independent clusters, each containing a single element. The two nearest clusters are then merged, reducing the number of clusters from N to . The distance between clusters is calculated in various ways, generating significantly different results. One example is to sum the distances between all possible pairs of points, with one point from each cluster, and divide by the product of the two numbers of elements from the two clusters [16]. The merging procedure is repeated until there is only one cluster, containing all N elements. The top-down approach is the reverse of the bottom-up approach. Instead of merging clusters, this method divides a single cluster into two at each step. By imposing HC, all possible clustering with all possible numbers of clusters are generated, and the user can choose the level (i.e., the number of clusters) for investigation.

Figure 10.

Hierarchical clustering dendrogram for the bottom-up approach. The dashed line shows the level selected for clustering when 4 clusters are required, and the dotted line shows the level selected when 6 clusters are required.

Friends-of-Friends clustering (FOF) can be viewed as single-linkage agglomerative hierarchical clustering with a ‘linking length’ l. In single-linkage clustering, the distance between two clusters is defined as the minimum distance between any two points in the clusters. The linking length serves as the threshold for merging: if the distance between two points is smaller than l, they are considered ’friends’ and belong to the same cluster [16].

An advantage of HC is that the computation does not need to be repeated if different numbers of clusters are considered. Another advantage is that HC does not assume the shape of clusters to be convex, unlike GMM and K-means algorithms.

HC has been applied to cluster bivariate data (e.g., chemical abundances and positions of stars in [138,139]), higher-dimensional scattered data (e.g., [140]), light curves (e.g., [9]), and spectral data (e.g., [141]). FOF is often used in cluster analysis for cosmological N-body simulations, mostly to cluster particles into dark matter halos (e.g., [142,143,144]).

3.4. Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise

Density-based spatial clustering of applications with noise (DBSCAN, [145]) is another clustering algorithm that discovers clusters of all shapes and does not require a specified number of clusters. DBSCAN divides the areas into high-density areas and low-density areas. High-density areas are where the cluster lies. Core samples are picked from high-density areas. We define the core sample as a sample that has a minimum of k samples at a maximum distance s from itself. Samples within a distance s from a core sample are considered neighbors of the sample. Then, the same requirement is applied to find the core samples among the neighbors. Samples are assigned to the same cluster as their nearest core sample. Then, for each additional core sample, we find its neighboring core samples. The steps are performed iteratively to cluster the samples.

DBSCAN has some advantages and disadvantages. As discussed above, an advantage of DBSCAN is that it does not assume the clusters to have convex shapes, thus discovering clusters with arbitrary shapes. Another advantage is that DBSCAN can filter out the outliers, which are non-core samples that do not neighbor any core sample. On the other hand, one crucial disadvantage of DBSCAN is that the results are greatly impacted by the parameters k and s, especially s. For high-density data, DBSCAN may require a higher k for better clustering. s is highly dependent on the data: setting s too small would lead to the fringes of clusters being recognized as outliers, while setting s too large could merge clusters. However, there are various ways to determine k and s (e.g., [146,147,148,149]). Another disadvantage of DBSCAN is the single density threshold conveyed by the fixed k and s, which means DBSCAN may not be useful when the clusters have different densities (i.e., inhomogeneous). This disadvantage could be avoided using hierarchical DBSCAN, which is introduced in Section 3.5.

DBSCAN has been applied to five-dimensional scattered data from catalogs (e.g., position and motion taken from GAIA catalogs by [146,150,151]), three-dimensional positional scattered data (e.g., positions of stars, taken from GAIA catalogs, by [147]), spectral data (e.g., [148,149]), and images (e.g., [10]).

3.5. Hierarchical Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise

Hierarchical density-based spatial clustering of applications with noise (HDBSCAN, [152]) is the hierarchical extension of DBSCAN, as indicated by the name. HDBSCAN is also used for clustering, especially for globally inhomogeneous data, whereas DBSCAN assumes the data to be homogeneous. As discussed above, DBSCAN imposes a single density threshold to define clusters. As a result, DBSCAN may not be applicable when the clusters have different densities. HDBSCAN solves this problem by fixing the minimum number of samples k and considering all possible distances s (for more information on k and s, refer to Section 3.4). First, HDBSCAN defines the core distance of a point as the distance to its nearest k-th point. For all pairs of points p and q, HDBSCAN defines the mutual reachability distance as the maximum of the core distances of the two points and the distance between them, and thus transforms the graph so that each pair of data points is separated by their mutual reachability distance. Then, HDBSCAN finds the minimum spanning tree in the new graph, which connects all points with the smallest total distance while avoiding cycles. From the minimum spanning tree, HDBSCAN uses HC to find all possible clusterings.

HDBSCAN has all the advantages of DBSCAN, but it also has two additional advantages: HDBSCAN does not apply the same density threshold to all clusters, and the computation does not need to be repeated to consider different numbers of clusters. HDBSCAN eliminates the use of s and instead has a new parameter—the minimum size of a cluster. In some cases, this parameter may be easier to set than s, since it is basically asking what size of a group of data you would consider a cluster [153]. Similarly, HDBSCAN shares some limitations with DBSCAN. A key disadvantage is its sensitivity to hyperparameters: selecting suboptimal values can lead to under- or over-clustering. In addition, HDBSCAN tends to identify clusters in the densest regions, potentially labeling points in more diffuse clusters as outliers [152].

HDBSCAN has been applied to spectroscopic and photometric data (e.g., [154,155,156]), light curves (e.g., [157]), astrometric data (e.g., [158]), and other catalogs (e.g., [159,160]).

3.6. Fuzzy C-Means Clustering

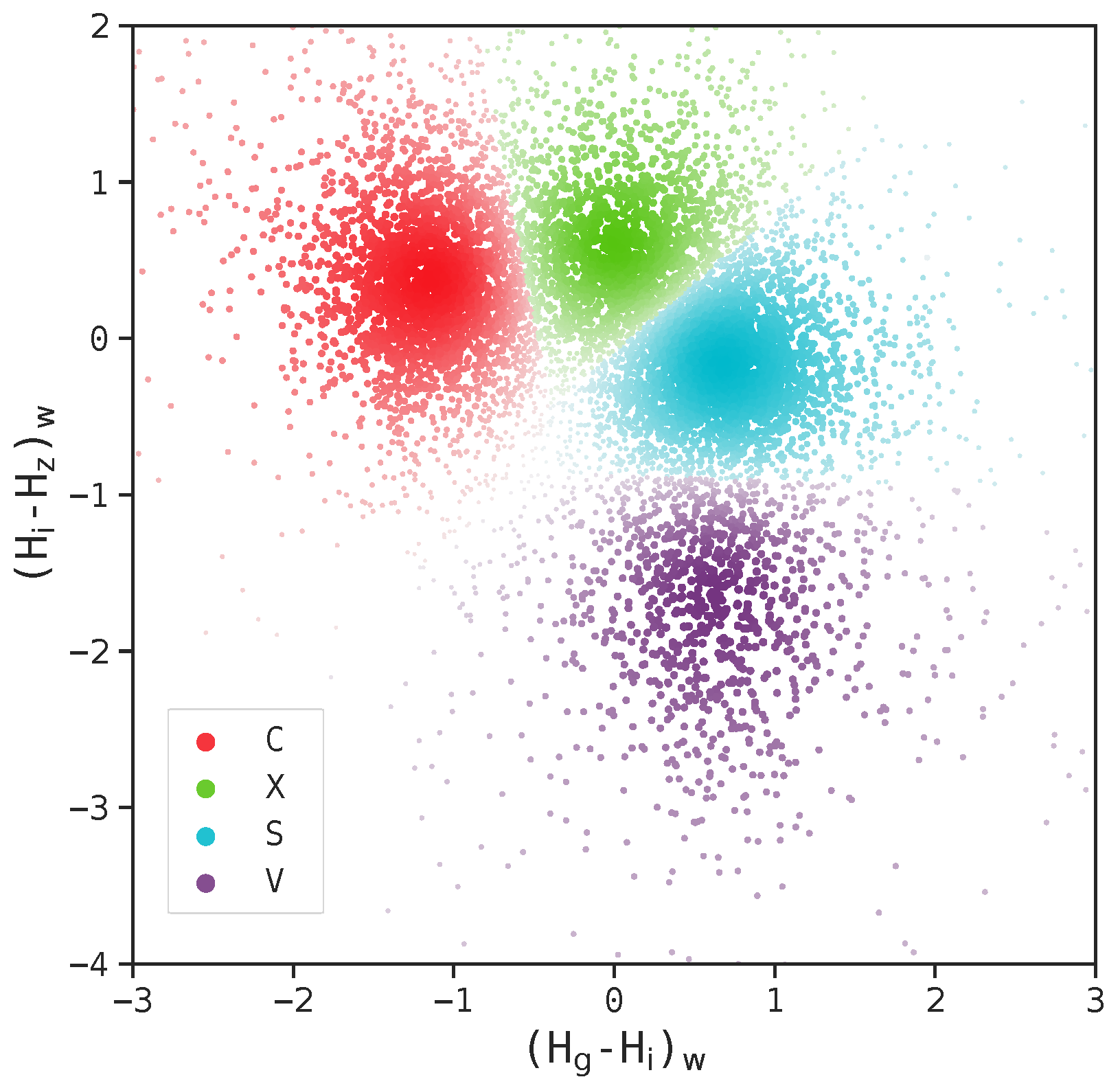

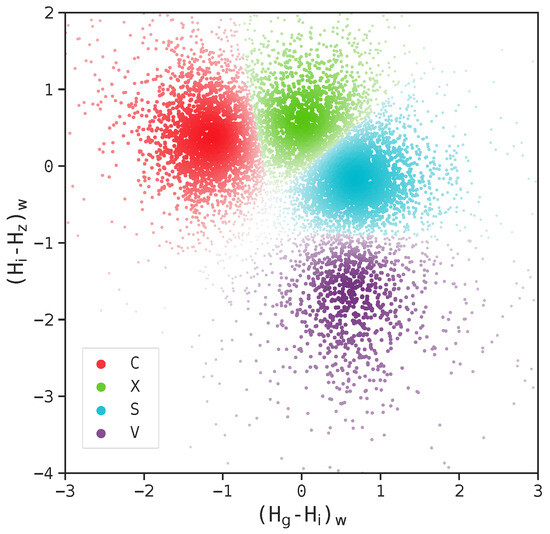

Fuzzy C-means clustering (FCM, also known as C-means clustering), being the most widely applied fuzzy clustering (also known as soft clustering) algorithm, was initially developed by Dunn [161] and further improved by Bezdek [162]. Soft clustering means that the algorithms may not assign a data point to a single cluster. Instead, the point may be assigned to multiple clusters with corresponding membership grades between 0 and 1. That is, a point at the edge of a cluster may have a smaller membership grade for that cluster (e.g., 0.1) compared to a point at the center of the cluster (e.g., 0.95). Turning to FCM, it is very similar to the K-means algorithm mentioned in Section 3.2. The only difference is that K-means clustering imposes hard clustering, while C-means clustering imposes soft clustering. In fact, K-means clustering is sometimes referred to as hard C-means clustering [163]. Figure 11 shows an application of FCM to two-dimensional scattered data from the Sloan Moving Object Catalog.

Figure 11.

Example of clustering with FCM applied to scattered data. The intensity of each data point reflects the probability of its membership in the cluster. The figure is taken from Colazo et al. [164], licensed under CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

The advantages and disadvantages are very similar to those of K-means clustering. One shared disadvantage is the need for prior knowledge about the number of clusters. To avoid this problem, FCM can be imposed using different numbers of clusters, and then one can compute the fuzzy partition coefficient for each resulting clustering, which measures how well the clustering describes the data, and select the number of clusters that generates the smallest coefficient. Compared to K-means, an advantage of FCM is that it may be more flexible because it allows assigning multiple clusters to a point, thus generating more reliable results. However, FCM is more expensive in computation due to the same characteristic. There are some algorithms built on FCM, aiming at reducing the computational cost (e.g., [165,166]).

Fuzzy clustering has been applied to cluster catalogs (e.g., [167,168]), spectral data (e.g., [169]), and images (e.g., [170]). FCM has been applied to cluster time series data (e.g., [171]), catalogs (e.g., [172,173]), and images (e.g., [174,175]).

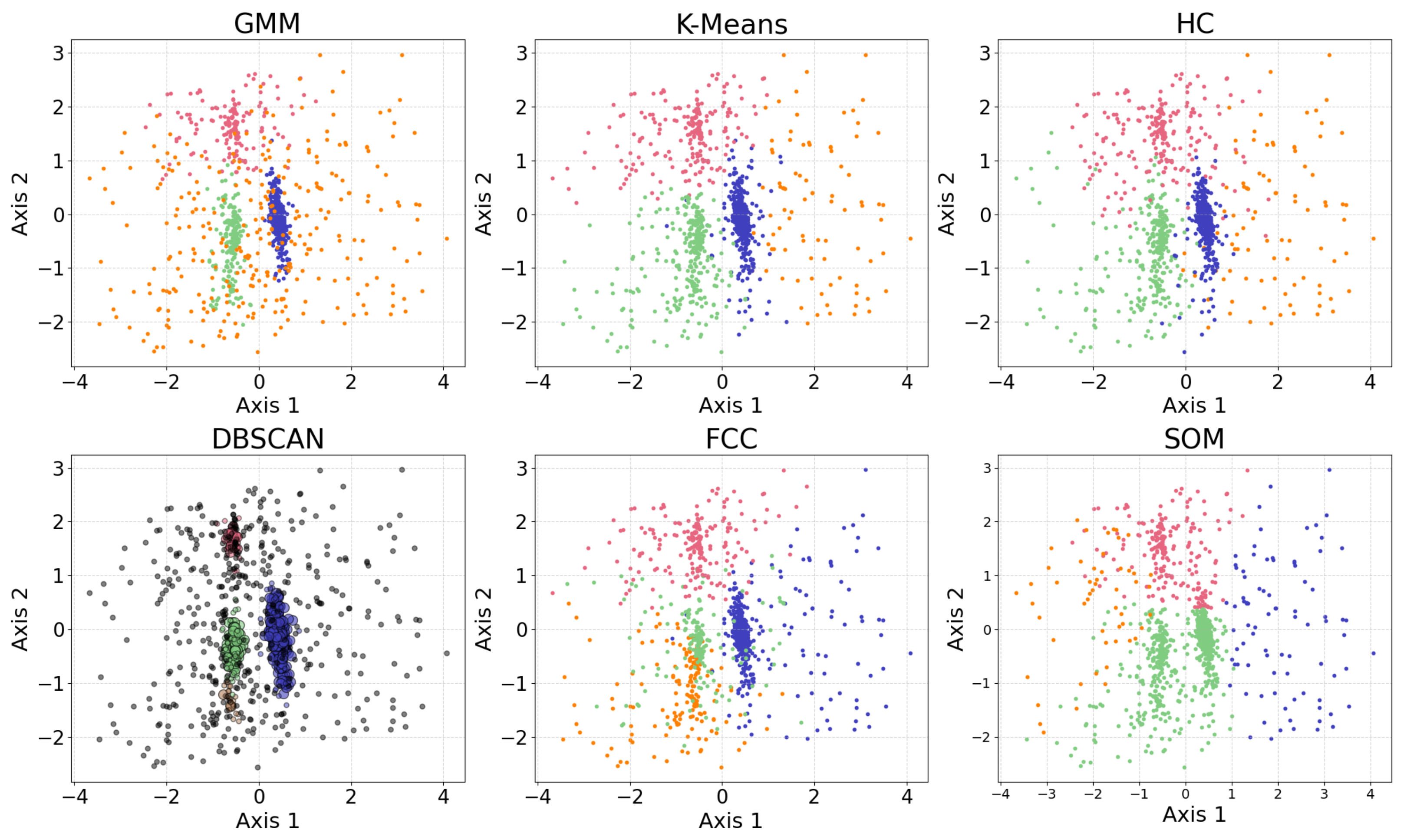

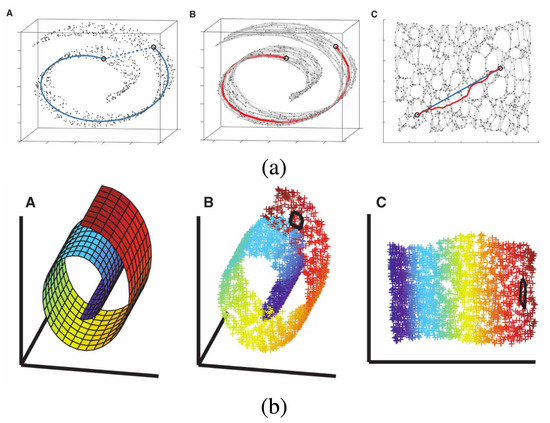

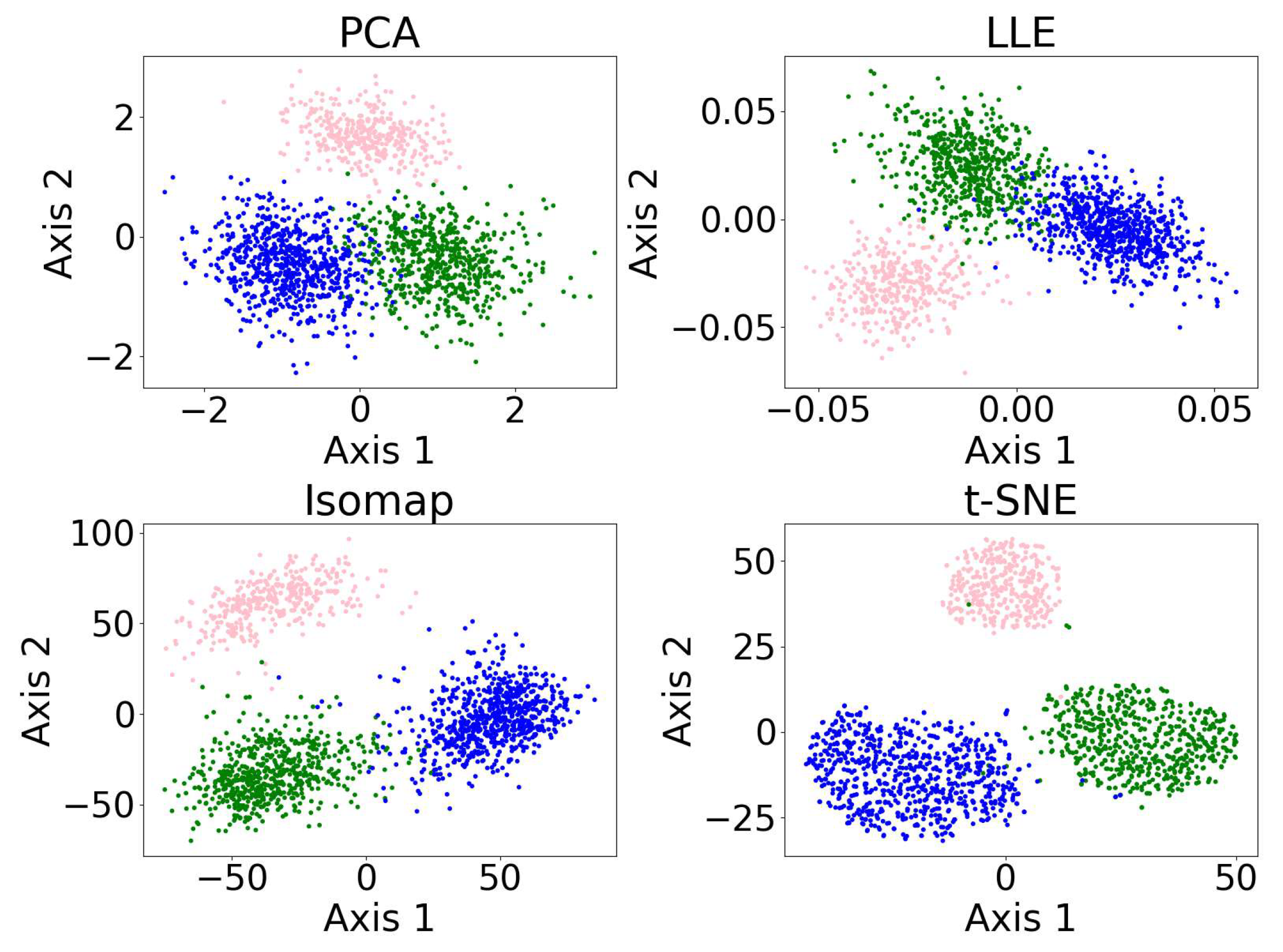

3.7. Examples of Applications of Different Clustering Algorithms

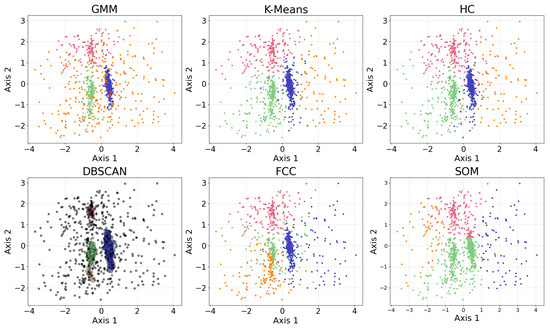

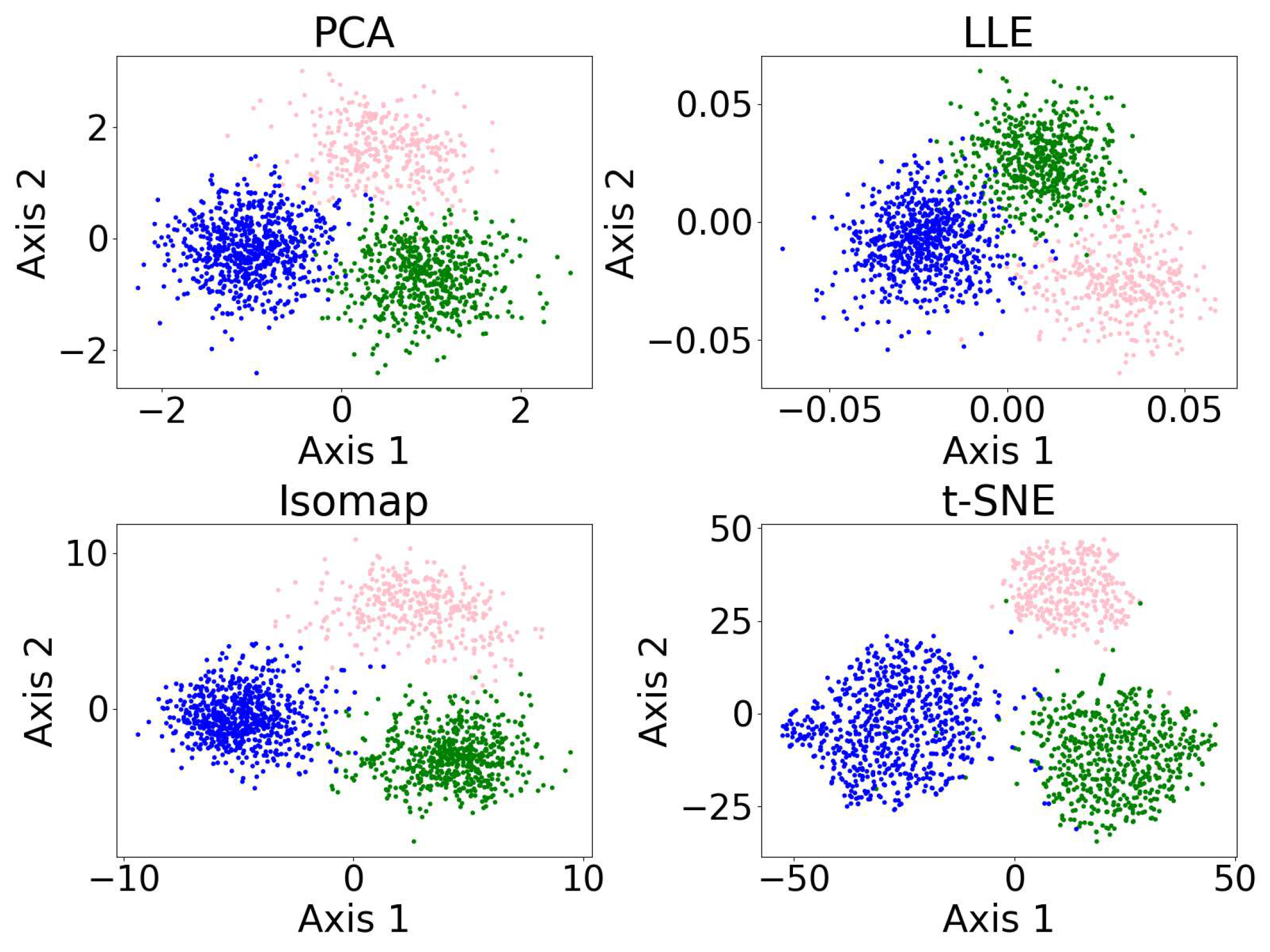

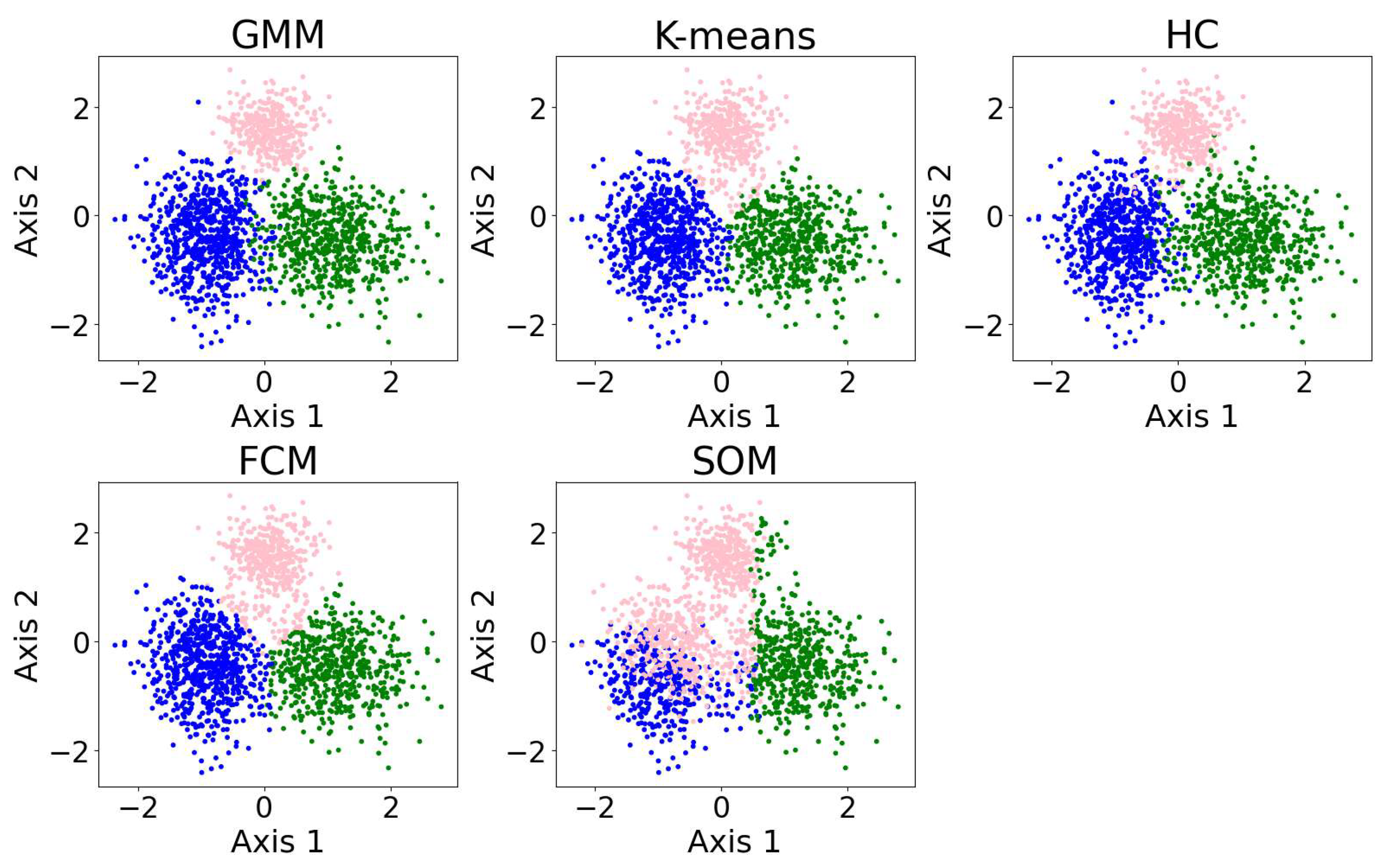

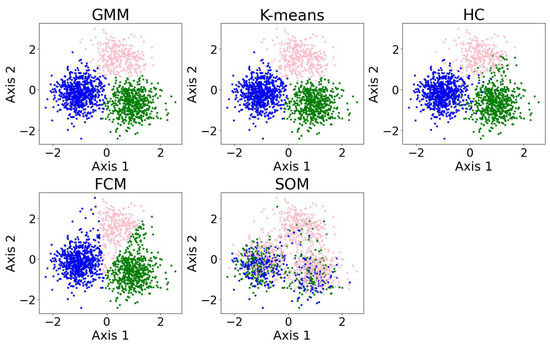

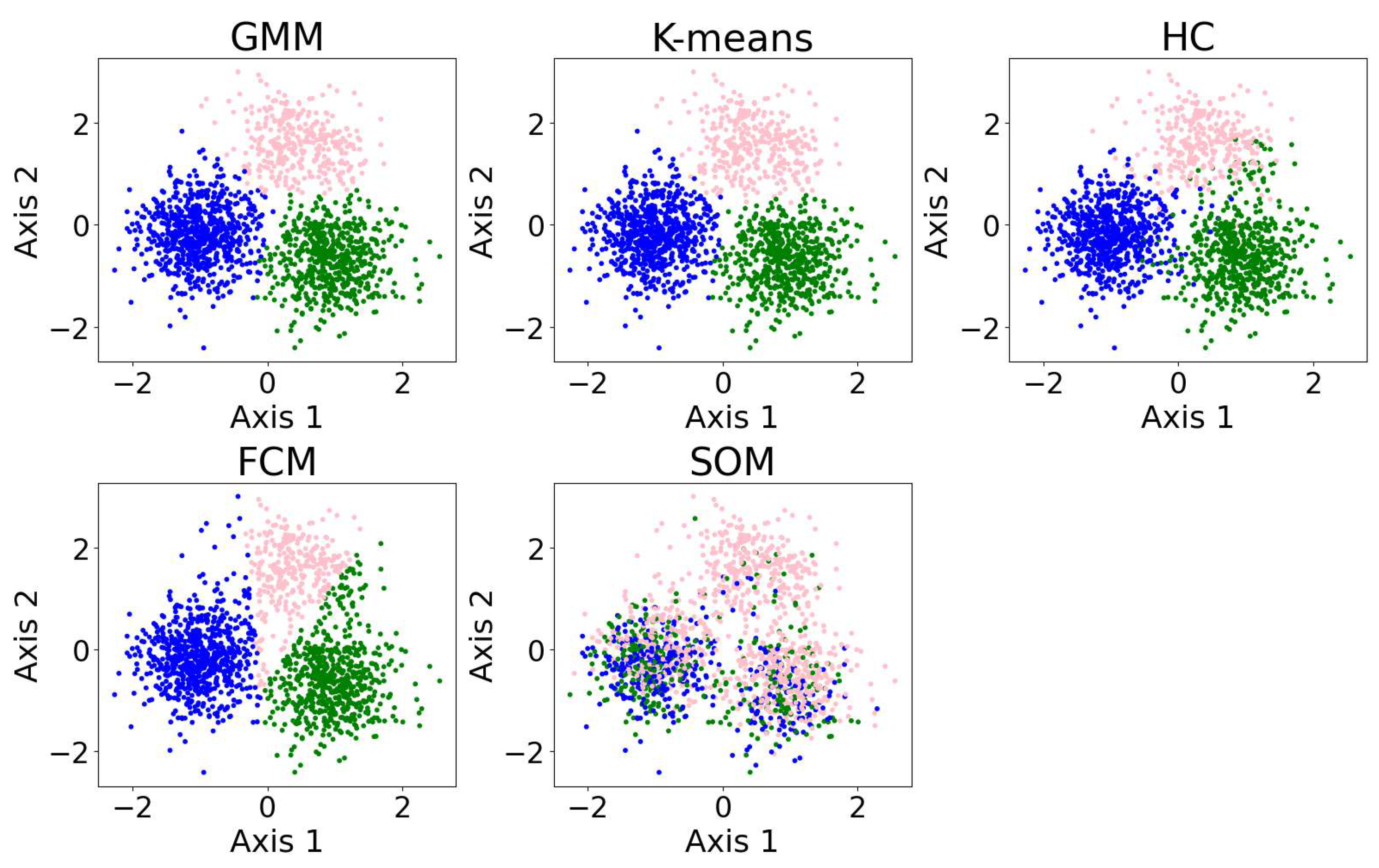

In this section, we present examples of applying different clustering algorithms to the same real observational datasets in astronomy as those introduced in Section 2.4. Figure 12 shows the results of the clustering algorithms, including the GMM, K-means, HC, DBSCAN, FCM, and the self-organizing map (SOM, see Section 2.3.1). PCA is applied for visualization after the dataset is clustered. The clustering algorithms are applied to generate four clusters, as suggested by the BIC calculation discussed in Section 3.1.

Figure 12.

The clustering algorithms are applied to the same five-dimensional dataset, with the number of clusters set to four based on the BIC calculation. For algorithms that do not take the number of clusters as a hyperparameter, their hyperparameters were selected to yield four clusters. The algorithms include the GMM, K-means, HC, DBSCAN, FCM, and the SOM. The dataset is dimensionally reduced with PCA to a two-dimensional projection after the dataset is clustered. The colors of the clusters are selected manually. When interpreting the results, note that PCA may not provide the best representation of the clusters; therefore, overlapping clusters or other irregularities do not necessarily indicate a failure of the algorithm. Among the six algorithms, the GMM and DBSCAN yield similar results by recognizing outliers, while K-means and HC produce similar clusterings.

Among the six algorithms, the GMM and DBSCAN yield similar results by recognizing outliers, while K-means and HC produce similar clustering. The GMM, K-means, and HC identify three relatively dense, convex-shaped clusters and one scattered cluster that likely represents outliers. In contrast, DBSCAN excludes the outlier cluster from its core clusters, instead labeling the scattered points as noise, resulting in a total of five distinct clusters. Comparing the GMM and DBSCAN, the overlap between corresponding clusters shows high consistency, where 83.3% of the data points are similarly clustered: the upper clusters overlap by 19.9% of the GMM upper cluster and 100.0% of the DBSCAN upper cluster; the lower right clusters by 99.3% and 96.8%, respectively; the lower left clusters by 74.4% and 99.3%, respectively (where the green and orange clusters are combined for easier comparison); and the broader (i.e., outlier) clusters by 94.9% and 63.8%, respectively. Comparing K-means and HC, the overlap between corresponding clusters also shows high consistency, where 94.16% of the data points are similarly clustered: the upper clusters (pink) overlap by 91.7% of the K-means upper cluster and 85.8% of the HC upper cluster; the lower right clusters (blue) by 95.1% and 99.2%, respectively; the lower left clusters (green) by 94.6% and 93.9%, respectively; and the scattered clusters on the right by 93.1% and 87.1%, respectively. The statistics may change slightly if the program is re-run, as most algorithms are not deterministic.

We also applied the algorithms to cluster 5-dimensional and 10-dimensional synthetic datasets. The results and evaluations are presented in Appendix A.3. We find that the GMM outperforms the other algorithms, while K-means demonstrates improved accuracy and robustness in higher dimensions. The SOM yields poor clustering performance; however, it is typically not used for clustering directly. The SOM is typically used for data visualization or as a preliminary step before applying other clustering algorithms.

3.8. Benchmarking of Clustering Algorithms

In this section, we present a benchmarking study of clustering algorithms. Table 3 summarizes each algorithm’s run time, classic applications, novel applications, popular datasets, strengths, weaknesses and failure modes, and overall evaluation. We also provide a summary of literature-based comparisons of algorithm performance.

Table 3.

Benchmarking table of the clustering algorithms.

Table 4 presents the result of a focused search, showing the number of refereed astronomy papers in the ADS that applied each algorithm to different types of data from 2015 to 2025. These results offer insight into which algorithms are most widely used for specific types of analyses, reflecting current trends and preferences in the field.

Table 4.

Result of a focused search, showing the number of refereed astronomy papers in ADS that applied each clustering algorithm to different types of data from 2015 to 2025. The rows are ordered by the sum of all algorithm applications, with higher totals ranked first. The box corresponding to the most popular application for each algorithm is highlighted in yellow.

Compared to the dimensionality reduction algorithms, the difference in application of the clustering algorithms may be more significant. Generally speaking, when clusters are spherical and have similar densities, K-means provides fast and inexpensive clustering and is applicable to large, high-dimensional datasets. When clusters have different sizes but are still convex-shaped (e.g., spherical or oval), the GMM can be applied and will be fast when there is not much noise. If clusters are not convex-shaped but have similar densities, DBSCAN can be applied. If clusters are not convex-shaped and have different densities, HDBSCAN can be applied. If we want to investigate the hierarchical structure of the dataset, HC can be applied. If the clusters overlap and we want to know the membership probability, soft clustering algorithms, such as FCM, can be applied.

Some studies compare the discussed algorithms. As Hunt and Reffert [151] point out, both the GMM and K-means do not deal with noise, while DBSCAN and HDBSCAN do. The same paper also suggests that DBSCAN produces less reliable OC membership lists compared to the GMM and HDBSCAN. Yan et al. [148] suggest that DBSCAN can identify consecutive structures in position–position–velocity space, while HDBSCAN cannot. Yan et al. [100] suggest that, when applied to classify accretion states, K-means is usually more accurate than HC.

4. Other Applications of Unsupervised Machine Learning

This section introduces two additional applications of unsupervised machine learning: anomaly detection and symbolic regression. Anomaly detection refers to identifying outliers in a dataset using various algorithmic approaches. Symbolic regression is a task where algorithms, typically genetic programming, search for one or more analytical expressions that model the data, with or without prior physical knowledge.

4.1. Anomaly Detection

Anomaly detection aims to find objects that either do not belong to pre-defined classes (in supervised learning) or are produced as noise or unusual events. Anomaly detection is particularly crucial as a pre-processing step before applying supervised algorithms: when a supervised classification algorithm is trained, we typically do not include anomalies in the training set. Therefore, if anomalies are presented as input to a supervised classifier, they will be forcibly assigned to one of the pre-defined classes [201].

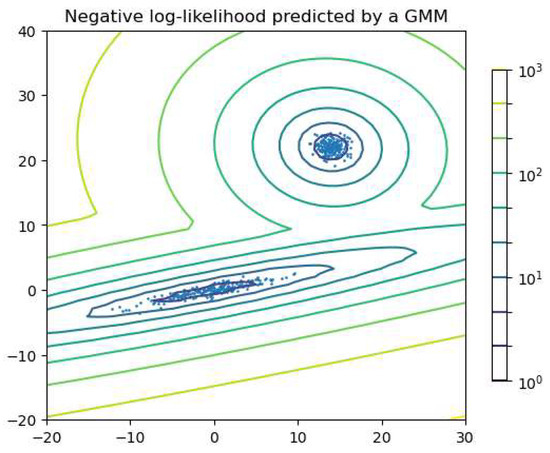

Some dimensionality reduction algorithms, such as LLE and t-SNE, are good visualization tools to identify the outliers [15]. These projections often map outliers far from the main clusters, which can help guide the application of clustering algorithms to detect outliers more effectively (e.g., [48]). Furthermore, certain clustering algorithms can identify outliers directly, without relying on a dimensionality reduction step. For example, the GMM can group the outliers into one or multiple clusters but may not classify them as outliers, as shown in Figure 12. An extension of the GMM computes the log-likelihood of each sample, where a smaller score indicates a higher chance of being an outlier. The threshold for outlier detection may be manually selected to achieve better results, especially when the probabilistic distribution of the data points is not Gaussian. Other clustering algorithms, such as DBSCAN and its variant HDBSCAN, can also identify the outliers, though both require certain parameters to be selected manually. SOM denoising also performs outlier detection but requires a manually defined probabilistic threshold, similar to the GMM (e.g., [105]). VAEs can also be used to identify outliers by applying a threshold on the reconstruction error of each data point. For example, Villaescusa-Navarro et al. [202] use a fully unsupervised VAE on 2D gas map images and identify anomalies: images with significantly larger reconstruction errors compared to typical samples are classified as outliers. Their goal is to provide theoretical predictions for various observables as a function of cosmology and astrophysics, and the anomaly detection step helps to rule out theoretical models that deviate from the learned manifold.

In addition to the algorithms discussed above, Isolation Forest (iForest, [203]) is a dedicated anomaly detection algorithm. iForest uses random trees to randomly partition the dataset. It randomly selects a feature (i.e., a dimension), chooses a random splitting threshold on that feature, and recursively partitions the data until each point is isolated in its own partition. The outliers are partitioned first because they are more isolated (i.e., sparse and located at the edges of the data), resulting in a smaller isolation path length, which is the number of partitions required to isolate a point. This suggests that, given the path length, a shorter path length suggests a higher likelihood of the point being an outlier. The path length greatly relies on the initial random partitions, so multiple trees are considered. The anomaly score is computed from the lengths obtained from multiple trees, with outliers having higher anomaly scores. The number of trees and the threshold for determining outliers are user-defined, where the threshold is often indicated by the contamination rate hyperparameter, which can significantly impact the results. Due to its structure, iForest is fast and efficient. However, iForest may not perform well when interdependencies exist between features [204]. iForest has been applied to detect the outliers in time series (e.g., [204]), catalogs (e.g., [205]), light curves (e.g., [157]), and latent spaces of neural networks (e.g., [206,207,208]).

In addition to unsupervised methods, there are also semi-supervised approaches (Section 5) for identifying anomalies. Richards et al. [201] introduced a semi-supervised routine to classify All Sky Automated Survey objects while detecting anomalies. The paper applies Random Forest—typically used as a supervised algorithm—in a semi-supervised setting, where the feature vector produced by the Random Forest is used to compute an anomaly score for each object. A threshold on this score is then used to determine the anomalies. The study claims that this routine is able to find interesting objects that do not belong to any of the pre-defined classes. Furthermore, Lochner and Bassett [209] point out that although most anomaly detection methods are able to flag anomalies, they often fail to distinguish relevant anomalies from irrelevant ones. For example, one may want to remove anomalies caused by instrument errors but retain unusual astronomical events or features. The ‘relevance’ of anomalies ultimately depends on the users’ scientific goals. They introduce a semi-supervised anomaly detection framework, Astronomaly, that uses active learning to search for interesting anomalies. The authors demonstrate that the method is able to recover many interesting galaxies in the Galaxy Zoo dataset.

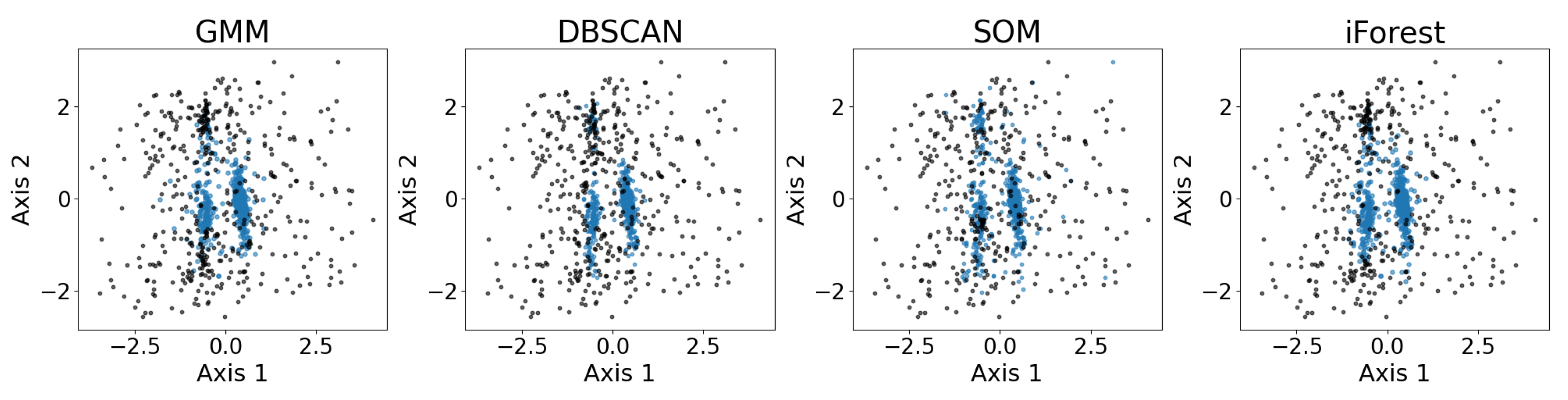

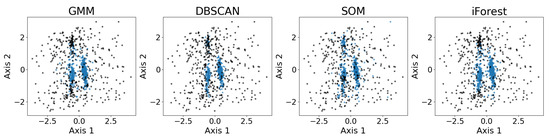

Figure 13 shows the exemplary results of outlier detection using the GMM, DBSCAN, the SOM, and iForest. The datasets are the same real observational datasets in astronomy as those introduced in Section 2.4. As shown, all four outlier detection algorithms identify the three major convex-shaped clusters, as discussed in Section 3.7, generating similar results with minor differences. While the true outliers are unknown, the algorithms show consistent patterns in separating points that lie farther from the cluster cores, particularly for the two larger clusters. The SOM exhibits a more scattered inlier pattern, whereas the GMM, DBSCAN, and iForest produce results that largely confirm each other.

Figure 13.

Results of outlier detection using the GMM, DBSCAN, the SOM, and iForest on the five-dimensional dataset, presented using PCA. The labeled inliers are the blue dots, and the labeled outliers are the black dots. The four anomaly detection algorithms are able to identify the three major clusters to some extent. Under PCA visualization, both the GMM and SOM label a few points along the edge of the cluster as outliers, while DBSCAN and iForest consider half of the upper cluster as outliers. Again, PCA may not provide the best representation of the clusters, so irregularities do not necessarily indicate a failure of the algorithm.

4.2. Symbolic Regression

Symbolic regression (SR) is an algorithm that computes analytical equations solely from the data by finding the equations and their parameters simultaneously [210]. SR is based on the concept of genetic programming, which is a subfield of evolutionary computing. SR randomly initializes the first population, generating multiple configurations (i.e., equations). The symbolic expression of the equation can be visualized using tree structures with nodes and branches, with each node being a symbol (e.g., ÷, log, 4.2, X, and Y). SR examines the configurations and removes the less effective ones. Then, SR randomly selects and exchanges sub-configurations from two or more configurations. The evolutionary procedure iterates until SR produces a robust equation.

SR is frequently used as a supervised learning algorithm, where a label y is given for every data point , and the goal is to find a model . SR can also be applied in an unsupervised setting, where the objective is to discover an implicit relationship among variables by identifying an equation of the form that describes the dataset [211]. Equivalently, if the dataset consists solely of the variables, one may seek a relation . While there are numerous applications of supervised SR in astronomy (e.g., [212,213,214,215,216]), the use of unsupervised SR remains relatively unexplored. A key reason why unsupervised SR has seen limited application is the difficulty of identifying a meaningful model that satisfies an implicit equation. The discrete search space contains a dense distribution of degenerate solutions—in simpler terms, there are infinitely many mathematically valid implicit equations that fit the data [211]—which degrades SR performance [217]. For example, an implicit model of the form is valid whenever and are semantically equivalent (e.g., and ). Therefore, only a few SR methods are suitable for application to unlabeled data.

One early attempt to address this challenge was proposed by Schmidt and Lipson [211]. They show that directly applying basic SR methods does not guarantee recovering a meaningful implicit model for complex data. To address this, they introduce the Implicit Derivative Method, which uses the local derivatives of the data points when searching for an implicit equation. The idea is that a meaningful model should be able to predict the derivatives of each variable. For unordered data, one can fit a higher-order plane to the local neighborhood of each point and compute the derivatives from the fitted hyperplane. Schmidt and Lipson [211] demonstrate that this approach is accurate for simple 2D and 3D geometric shapes and for basic physical systems. However, it remains unclear whether the method can scale to the large, noisy, and high-dimensional datasets commonly encountered in astronomy.

Building on the need to better recover complex models, a more recent approach was introduced by Kuang et al. [217]. They propose a pre-training framework, PIE, designed to recover implicit equations from unlabeled data in an unsupervised setting. In particular, PIE generates a large synthetic pre-training dataset to refine the search space and reduce the impact of degenerate solutions. This method has not yet been applied in astronomy, and its applicability may be limited by the extremely large input data volumes typical of astronomical surveys, as well as the presence of noise and anomalies.

5. Future Directions

This section discusses the open challenges and future research directions of unsupervised ML in astronomy.

Scalability to large datasets has always been a critical problem for ML. Unsupervised ML, whose main aim is to reduce the manual cost of analyzing large datasets, requires the ability to handle large datasets efficiently. Many studies work with large databases such as Gaia and SDSS, but the actual size of the examined datasets selected from the databases is often moderate (e.g., 720k in Queiroz et al. [56] and 320k in Lyke et al. [81]). Therefore, the databases used in the studies may not fully reflect the scalability of the algorithms. Even algorithms successfully applied to full databases might struggle with future, larger datasets (e.g., the upcoming LSST survey5). Non-linear dimensionality reduction methods generally scale poorly due to high computational complexity, while PCA requires batch processing and large memory. Certain clustering algorithms (e.g., HC, DBSCAN, and HDBSCAN) also do not readily scale to extremely large datasets. The SOM is computationally complex and therefore scales poorly, whereas EM is expensive to train but can be applied to large datasets once trained. To mitigate these issues, practitioners have developed extensions of traditional algorithms, such as minibatch processing and randomized SVD, trading a small amount of accuracy for improved scalability.

Data acquisition also presents challenges. Although diverse types of data are available, a substantial gap exists between the volume of photometric and spectroscopic data. Compared to photometric data, spectroscopic data may give us more precise information about the objects, and most of the discussed ML algorithms are more often used on spectroscopic and spectral data, as shown in Table 2 and Table 4. However, as noted by van den Busch et al. [102], spectroscopic observations are considerably scarcer because they are more time-consuming and expensive. The scarcity of spectroscopic observations gives rise to a major challenge for redshift calibration, as photometric estimates for individual galaxies are less precise and subject to biases [218]. One strategy to address this limitation is direct calibration (DIR, [218]), which matches photometric sources to spectroscopic counterparts. However, because spectroscopic coverage is incomplete, photometric data without a corresponding spectroscopic match within the same SOM cell must be excluded. Building on DIR, Wright et al. [63] introduced additional quality control, an approach subsequently adopted by van den Busch et al. [102] and Hildebrandt et al. [62] to jointly exploit photometric and spectroscopic data for redshift calibration.

Building on the recent developments, future astronomical studies can leverage semi-supervised, self-supervised, and ensemble methods to improve data analysis. The following sections discuss these approaches in more detail, highlighting recent applications and potential benefits.

Semi-supervised and self-supervised learning are deep neural network methods. Semi-supervised learning utilizes both unlabeled and labeled data, a scenario very common in astronomy. In contrast, self-supervised learning generates its own labels from a given unlabeled dataset, which are then used for subsequent training. Together, semi-supervised and self-supervised approaches blur the traditional distinction between supervised and unsupervised learning. Focused research shows that the number of studies utilizing semi-supervised learning has increased exponentially since 2000, from just two papers in the ADS database between 2000 and 2005 to 124 papers between 2020 and 2025. Balakrishnan et al. [219] apply semi-supervised learning to classify pulsars, and Rahmani et al. [220] use it to classify galactic spectra. Both studies suggest that semi-supervised learning may have a higher classification accuracy compared to supervised learning. Similarly, Stein et al. [221] suggest that, compared to supervised and unsupervised learning, self-supervised learning may generate higher-quality image representatives, especially if there is insufficient labeled data.

Ensemble methods, which combine multiple algorithms to improve performance, include both hybrid models and model stacking. A hybrid model is a strategy that combines different algorithms with the same objective to generate an outcome, performing tasks such as classification. Hybrid models are expected to combine the advantages of individual algorithms while mitigating their disadvantages. For example, Kumar and Kumar [222] apply hybrid and traditional models to analyze sunspot time series data and find that hybrid models consistently outperform traditional models by capturing complex patterns. A pipeline can be considered a type of hybrid model if multiple algorithms are used. A pipeline is a workflow with multiple components, where each component produces its own output that is either used for subsequent analysis or serves as the final output. For instance, Angarita et al. [223] perform dimensionality reduction on a spectral catalog by applying LLE after PCA, as LLE is more computationally expensive, and then apply GMM for clustering. Asadi et al. [183] use K-means as a component of a semi-supervised learning framework, in combination with Random Forest, to classify spectroscopic data. Yan et al. [100] first cluster galactic photometric data into SOM neurons and then cluster the neurons using HC. Compared to using only HC, this model reduces computational cost. Compared to using only SOM, it is more flexible and allows faster inspection of results for different numbers of clusters. In addition, model stacking—a branch of ensemble learning6—is considered a branch of hybrid models when different algorithms are combined. Model stacking involves training multiple base models, followed by a meta-model trained on the predictions or outputs of the base models, which then produces the final result. Shojaeian et al. [224] demonstrate model stacking of six different algorithms using geometric data and further improve training using PCA. Bussov and Nättilä [225] provide an example in astrophysics, applying model stacking to multiple SOM models to study simulated plasma flows.

In recent years, there have been several developments in extending classical algorithms such as the SOM and HDBSCAN. A frequently used algorithm for star clustering is Stars’ Galactic Origin (StarGo, [226]), which is based on the SOM. Hierarchical Mode Association Clustering (HMAC, [227]) has been applied in astronomy to cluster astrometric data [139], while Agglomerative Clustering for ORganising Nested Structures (ACORNS, [189]) was developed to cluster spectroscopic data. Both HMAC and ACORNS are based on HC. HDBSCAN-MC [197] integrates Monte Carlo simulation with HDBSCAN to better handle astrometric data with significant uncertainties. The Extreme Deconvolution GMM (XDGMM) combines extreme deconvolution [228] with the GMM. Applications of the XDGMM include, but are not limited to, identifying membership lists of the Gaia-Sausage-Enceladus using stellar spectroscopic data [177] and clustering Gamma-ray bursts [229]. These examples are not exhaustive, as new developments continue to emerge frequently.

In addition, new algorithms have been developed. Some of the new algorithms, such as the dimensionality reduction algorithm Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP), have increasing popularity in the field, while more applications may be needed for a comprehensive evaluation. Examples of UMAP applications include reducing the dimensionality of galaxy images [118], stellar spectral data [107], and simulated time series magnetohydrodynamic data of star-forming clouds [172].

6. Conclusions

This review discusses unsupervised machine learning algorithms used in astronomy, classifying the algorithms into two categories by their aims: dimensionality reduction and clustering. Anomaly detection and symbolic regression are also briefly discussed. For each algorithm, the mechanism, characteristics (e.g., advantages and disadvantages), and past applications are reviewed. Benchmarking studies are presented. Most algorithms are frequently used in astronomy, such as DBSCAN and the VAE, while some others are underutilized, such as unsupervised symbolic regression. Table 2 and Table 4 present the results of a focused search, showing the number of refereed astronomy papers in the ADS that applied each algorithm to different types of data from 2015 to 2025. These results offer insight into which algorithms are most widely used for specific types of analyses, reflecting current trends and preferences in the field. The rows are ordered by the sum of all algorithm applications, with higher totals ranked first.

This review also provides examples demonstrating the application of these algorithms to a real five-dimensional astrometry dataset and two synthetic datasets of five and ten dimensions. Overall, unsupervised machine learning has wide application in astronomy, allowing us to analyze a large quantity of high-dimensional, unlabeled data, meeting the needs arising from technological development regarding observation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.-T.K., D.X., and R.F.; methodology, C.-T.K. and D.X.; software, C.-T.K. and D.X.; validation, C.-T.K. and D.X.; formal analysis, C.-T.K.; investigation, C.-T.K. and D.X.; resources, C.-T.K.; data curation, C.-T.K.; writing—original draft preparation, C.-T.K.; writing—review and editing, C.-T.K. and D.X.; visualization, C.-T.K. and D.X.; supervision, D.X. and R.F.; project administration, C.-T.K., D.X., and R.F.; funding acquisition, D.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

D.X. acknowledges the support of the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), [funding reference number 568580]. D.X. also acknowledges support from the Eric and Wendy Schmidt AI in Science Postdoctoral Fellowship Program, a program of Schmidt Sciences.

Data Availability Statement

Data used in this study are publicly available from the SIMBAD astronomical database and were retrieved using the ‘Query by Criteria’ interface (https://simbad.cds.unistra.fr/simbad/sim-fsam (accessed on 8 September 2025)).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACORNS | Agglomerative clustering for organising nested structures |

| AE | Auto-encoder |

| BIC | Bayesian information criterion |

| CADET | Cavity Detection Tool |

| CAE | Convolutional auto-encoder |

| DBSCAN | Density-based spatial clustering of applications with noise |

| DESOM | Deep embedded self-organizing map |

| dim red | Dimensionality reduction |

| DIR | Direct calibration |