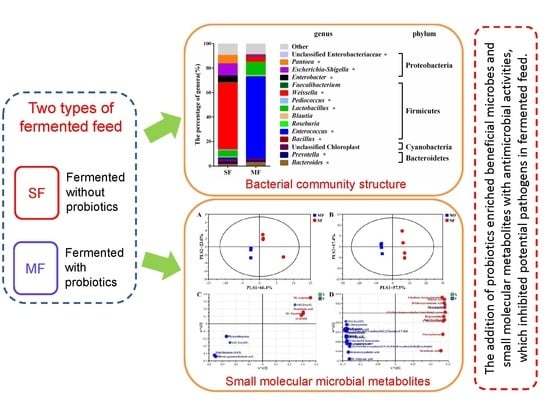

Comprehensive Understanding of the Bacterial Populations and Metabolites Profile of Fermented Feed by 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing and Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Lactic Acid and Volatile Fatty Acid Concentrations and pH in the Fermented Feed

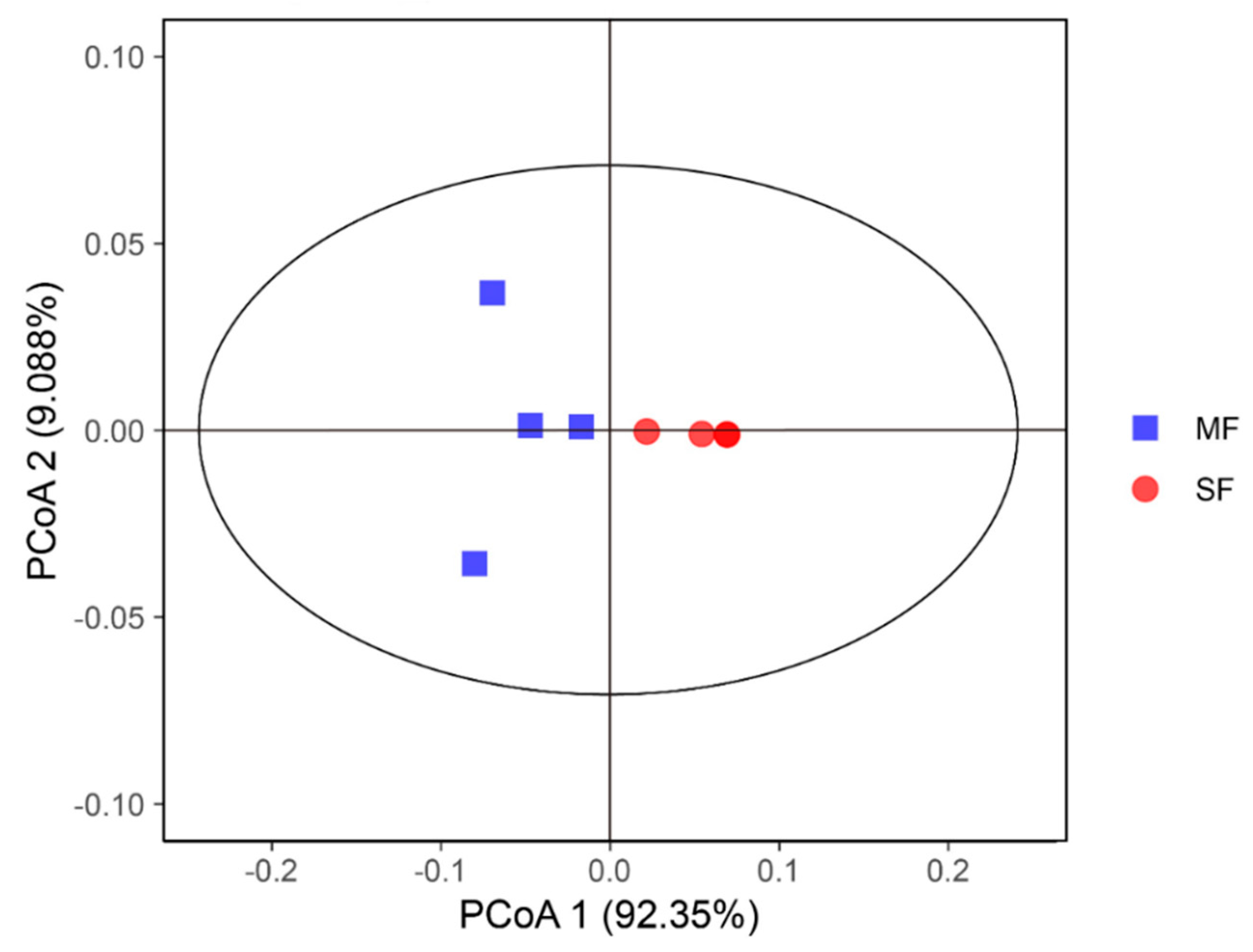

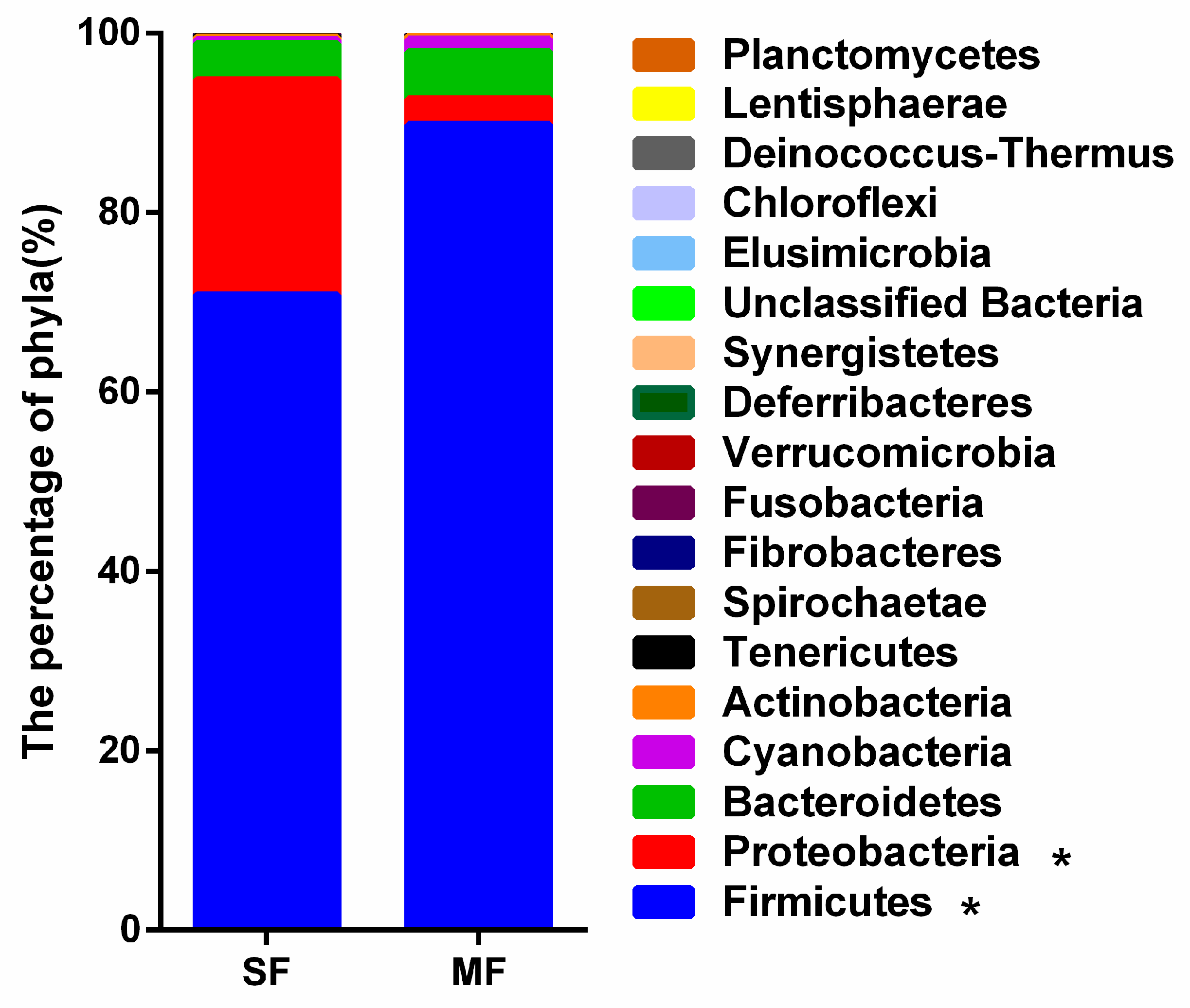

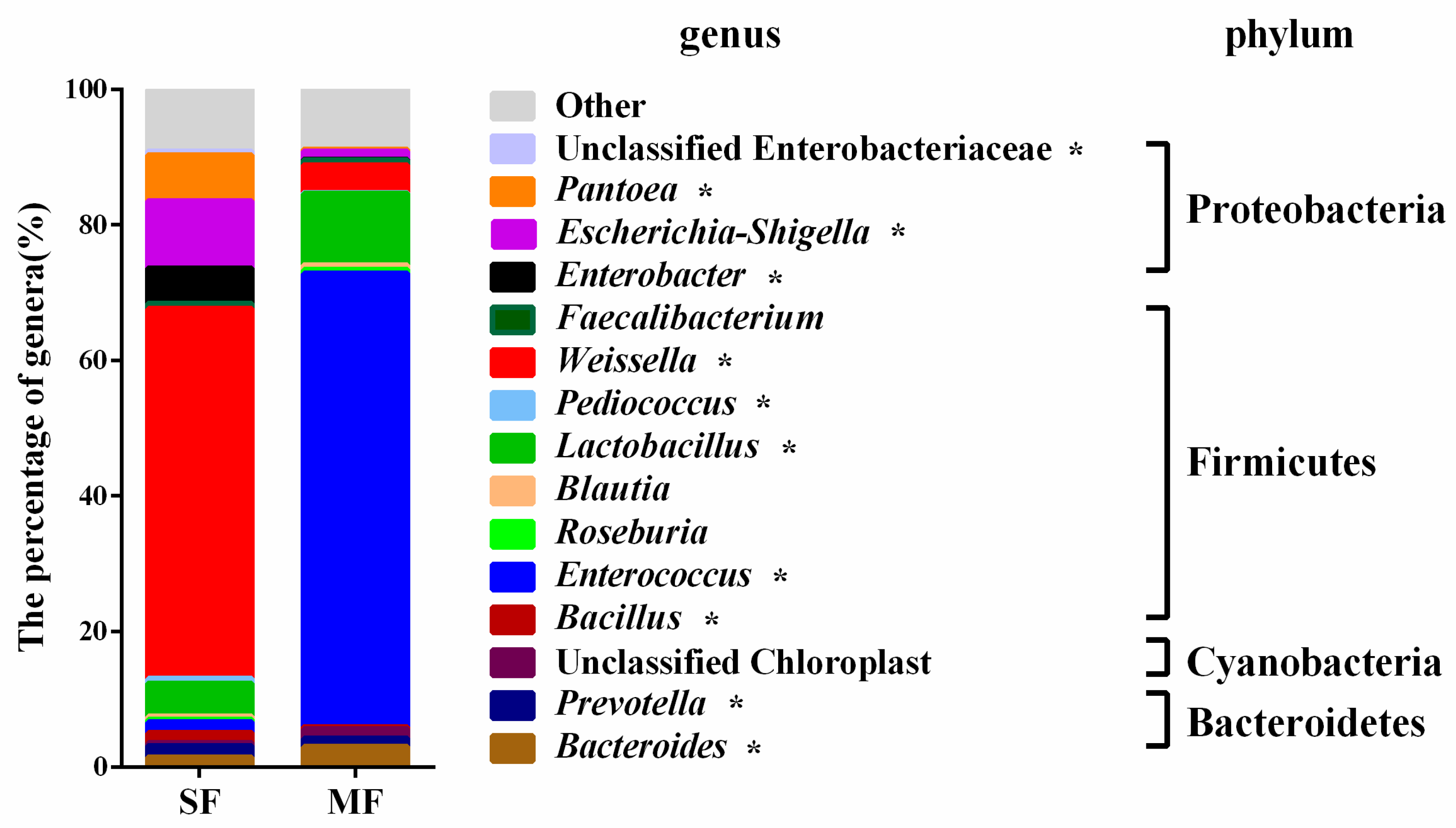

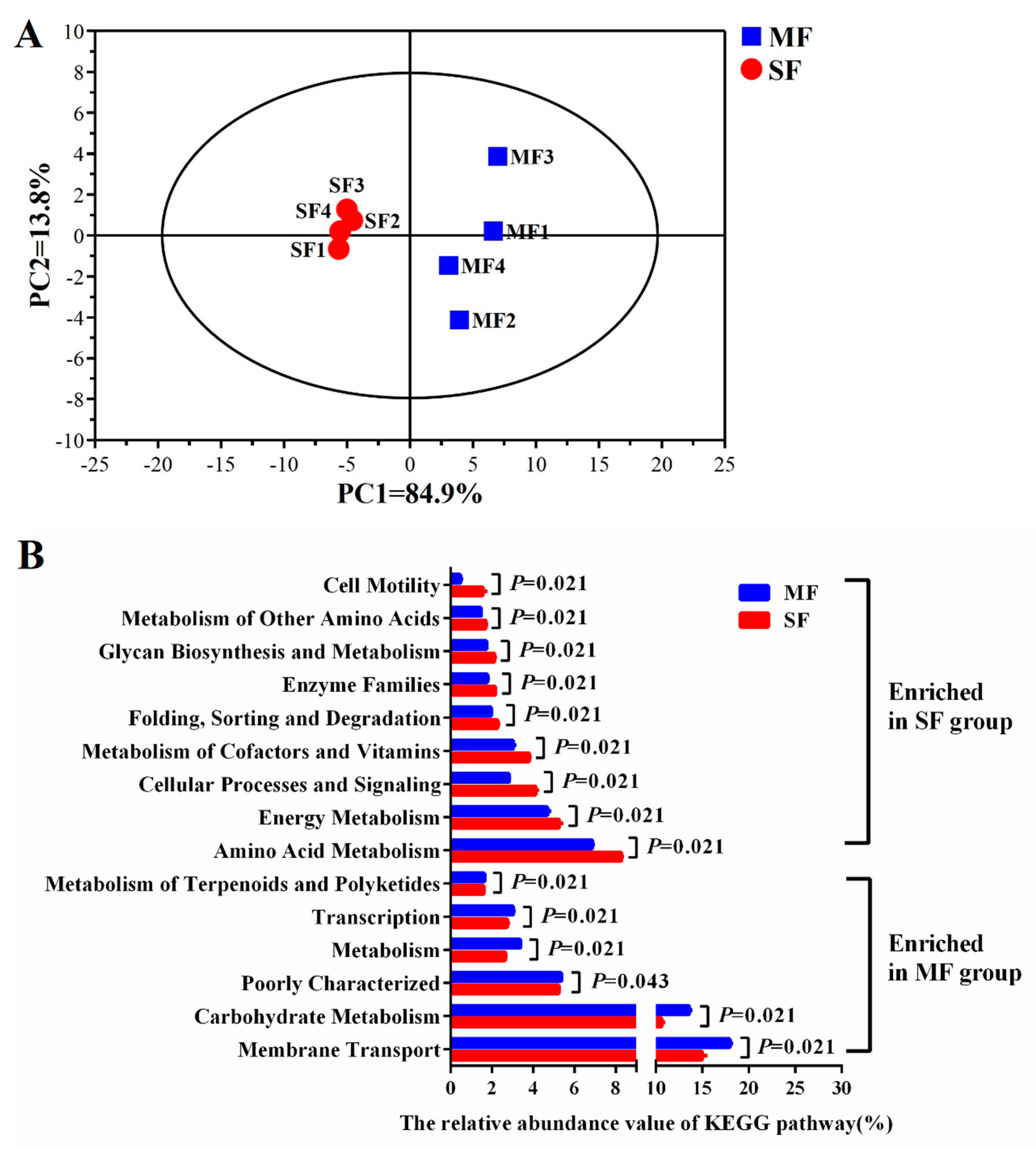

2.2. Bacterial Community Composition in the Fermented Feed

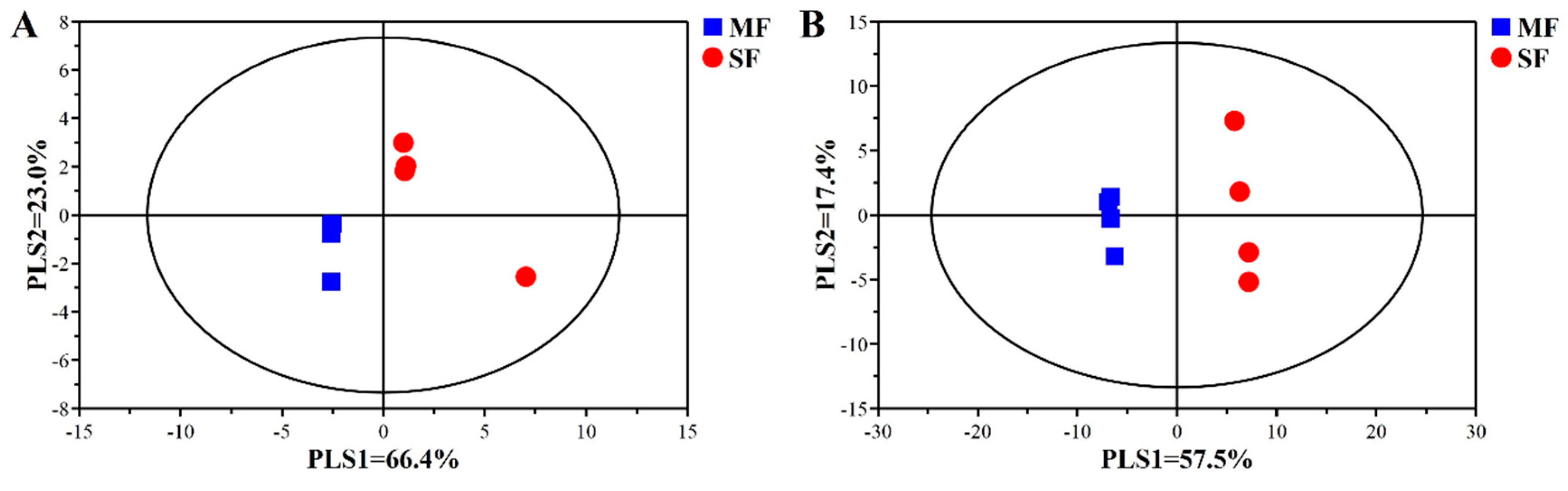

2.3. Small Molecular Metabolites in the Fermented Feed

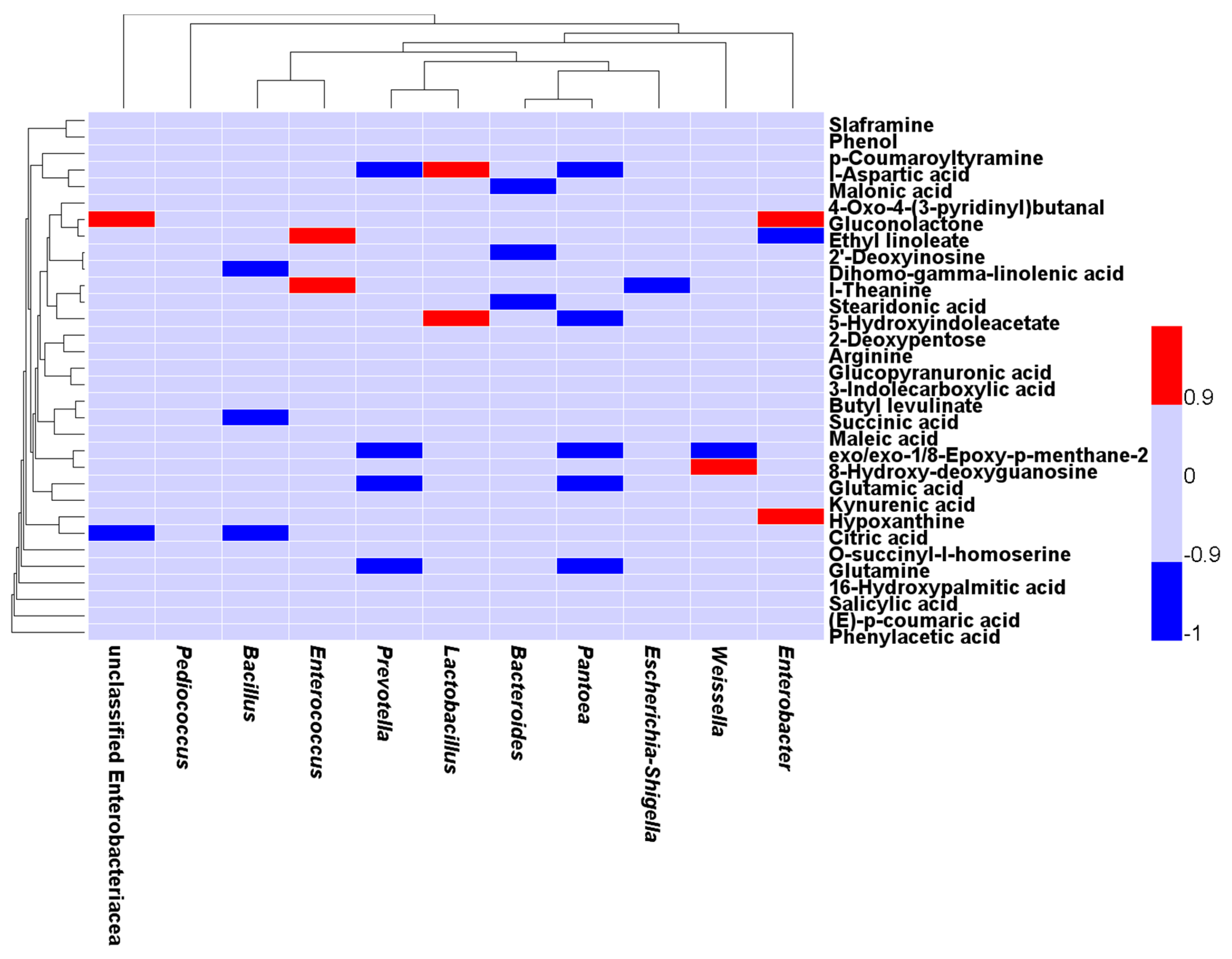

2.4. Correlation between the Bacterial Populations and Small Molecular Metabolites in the Fermented Feed

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Microorganisms, Culture Preparation, and Feed Fermentation Progress

4.2. Determination of pH and Volatile Fatty Acid (VFA) and Lactate Contents

4.3. DNA Extraction, 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing, and Data Analysis

4.4. Liquid Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry Analysis and Data Processing

4.5. Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Plumed-Ferrer, C.; von Wright, A. Fermented pig liquid feed: Nutritional, safety and regulatory aspects. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2009, 106, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Han, Y.; Zhao, J.Z.; Zhou, Z.J.; Fan, H. Consuming fermented distillers’ dried grains with solubles (DDGS) feed reveals a shift in the faecal microbiota of growing and fattening pigs using 454 pyrosequencing. J. Integr. Agric. 2017, 16, 900–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Shi, C.; Zhang, Y.; Song, D.; Lu, Z.; Wang, Y. Microbiota in fermented feed and swine gut. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 2941–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Missotten, J.A.M.; Michiels, J.; Goris, J.; Herman, L.; Heyndrickx, M.; De Smet, S.; Dierick, N.A. Screening of two probiotic products for use in fermented liquid feed. Livest. Sci. 2007, 108, 232–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Wang, F.; Lu, Z.; Wang, Y. Effects of supplementing sow diets with Saccharomyces cerevisiae refermented sorghum dried distiller’s grains with solubles from late gestation to weaning on the performance of sows and progeny. J. Anim. Sci. 2017, 95, 190–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, Y.; Wang, C.; Lu, Z.; Wang, F.; Feng, J.; Wang, Y. Amino acid and phosphorus digestibility of fermented corn-soybean meal mixed feed with Bacillus subtilis and Enterococcus faecium fed to pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 2017, 95, 3996–4004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Li, D.; Li, Z.L.; Kang, L.N.; Jiang, Y.Y.; Liu, X.Y.; Chi, Y.P.; Li, Y.Q.; Wang, J.H. Effects of Bacillus fermentation on the protein microstructure and anti-nutritional factors of soybean meal. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2017, 65, 520–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Gao, M.; Zhang, R.; Sun, Z.; Wang, C.; Yang, F.; Huang, T.; Qu, S.; Zhao, L.; Li, Y. Effects of soybean meal fermented by L. plantarum, B. subtilis and S. cerevisieae on growth, immune function and intestinal morphology in weaned piglets. Microb. Cell Factories 2017, 16, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Cho, Y.; Lee, Y.; Han, S.K.; Kim, C.G.; Choo, D.W.; Kim, Y.R.; Kim, H.Y. A proteomic approach for rapid identification of Weissella species isolated from Korean fermented foods on MALDI-TOF MS supplemented with an in-house database. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017, 243, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohashi, Y.; Ushida, K. Health-beneficial effects of probiotics: Its mode of action. Anim. Sci. J. 2009, 80, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Dun, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, D.; Peng, N.; Zhao, S.; Liang, Y. Dietary Enterococcus faecalis LAB31 improves growth performance, reduces diarrhea, and increases fecal Lactobacillus number of weaned piglets. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0116635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bednorz, C.; Guenther, S.; Oelgeschläger, K.; Kinnemann, B.; Pieper, R.; Hartmann, S.; Tedin, K.; Semmler, T.; Neumann, K.; Schierack, P.; et al. Feeding the probiotic Enterococcus faecium strain NCIMB 10415 to piglets specifically reduces the number of Escherichia coli pathotypes that adhere to the gut mucosa. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 9, 7896–7904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, C.; Xing, W.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, K.; Liu, J.; Deng, B.; Deng, J.; Li, Y.; Tan, C. Effects of dietary supplementation of probiotic Enterococcus faecium on growth performance and gut microbiota in weaned piglets. AMB Express 2019, 9, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatoum, R.; Labrie, S.; Fliss, I. Antimicrobial and probiotic properties of yeasts: From fundamental to novel applications. Front. Microbiol. 2012, 3, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.J.; Niu, C.C.; Guo, X.H. Mixed culture models for predicting intestinal microbial interactions between Escherichia coli and Lactobacillus in the presence of probiotic Bacillus subtilis. Benef. Microbes 2015, 6, 871–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Zhao, J.B.; Guo, P.T.; Lu, W.Q.; Geng, Z.Y.; Levesque, C.L.; Johnston, L.J.; Wang, C.L.; Liu, L.; Zhang, J.; et al. Dietary corn bran fermented by Bacillus subtilis MA139 decreased gut cellulolytic bacteria and microbiota diversity in Finishing Pigs. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paudyal, R.; Barnes, R.H.; Karatzas, K.A.G. A novel approach in acidic disinfection through inhibition of acid resistance mechanisms; Maleic acid-mediated inhibition of glutamate decarboxylase activity enhances acid sensitivity of Listeria monocytogenes. Food Microbiol. 2018, 69, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, B.K.; Lim, S.W.; Kim, B.S.; Lee, J.Y.; Moon, S.S. Isolation and in vivo and in vitro antifungal activity of phenylacetic acid and sodium phenylacetate from Streptomyces humidus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001, 67, 3739–3745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Cho, J.Y.; Kuk, J.H.; Moon, J.H.; Cho, J.I.; Kim, Y.C.; Park, K.H. Identification and antimicrobial activity of phenylacetic acid produced by Bacillus licheniformis isolated from fermented soybean, Chungkook-Jang. Curr. Microbiol. 2004, 48, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annan, N.T.; Poll, L.; Sefa-Dedeh, S.; Plahar, W.A.; Jakobsen, M. Volatile compounds produced by Lactobacillus fermentum, Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Candida krusei in single starter culture fermentations of Ghanaian maize dough. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2003, 94, 462–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelenko, C.; Wheeler, M.L.; Anderson, A.P.; Callaway, B.D.; McKinley, J.C. Studies in burns: XIV, Heling in burn wounds treated with Ethyl Linoleate alone or in combination with selected topical antibacterial agents. Ann. Surg. 1975, 182, 562–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yazawa, H.; Iwahashi, H.; Kamisaka, Y.; Kimura, K.; Aki, T.; Ono, K.; Uemura, H. Heterologous production of dihomo-γ-linolenic acid in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 6965–6971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Khan, M.A.K.; Yang, J.; Hussain, S.A.; Zhang, H.; Liang, L.; Garre, V.; Song, Y. Construction of DGLA producing cell factory by genetic modification of Mucor circinelloides. Microb. Cell Factories 2019, 18, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuevas, M.J.; Mauriz, J.L.; Almar, M.; Collado, P.S.; González-Gallego, J. Effect of epomediol on ethinyloestradiol-induced changes in bile acid and cholesterol metabolism in rats. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2001, 28, 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuong, Q.V.; Bowyer, M.C.; Roach, P.D. L-theanine: Properties, synthesis, and isolation from tea. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 1, 1931–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türközü, D.; Şanlier, N. L-theanine, unique amino acid of tea, and its metabolism, health effects, and safety. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 1681–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juneja, L.R.; Chu, D.C.; Okubo, T.; Nagato, Y.; Yokogoshi, H. L-theanine: A unique amino acid of green tea and its relaxation effect in humans. Trend Food Sci. Technol. 1999, 10, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, K.; Lee, C.; Kim, S.W. Aspergillus oryzae GB-107 fermentation improves nutritional quality of food soybeans and feed soybean meal. J. Med. Food 2004, 7, 430–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, W.; Li, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Mao, S.; Zhu, W. The bacterial and archaeal community structures and methanogenic potential of the cecal microbiota of goats fed with hay and high-grain diets. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 2018, 111, 2037–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.Z.; Mao, S.Y.; Yao, W.; Zhu, W.Y. DGGE and 16S rDNA analysis reveals a highly diverse and rapidly colonising bacterial community on different substrates in the rumen of goats. Animal 2008, 2, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporaso, J.G.; Kuczynski, J.; Stombaugh, J.; Bittinger, K.; Bushman, F.D.; Costello, E.K.; Fierer, N.; Pena, A.G.; Goodrich, J.K.; Gordon, J.I. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods. 2010, 7, 335–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, H.M.; Liu, J.H.; Feng, P.F.; Zhu, W.Y.; Mao, S.Y. Grain-rich diets altered the colonic fermentation and mucosa-associated bacterial communities and induced mucosal injuries in goats. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 20329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Garrity, G.M.; Tiedje, J.M.; Cole, J.R. Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 3, 5261–5267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeSantis, T.Z.; Hugenholtz, P.; Larsen, N.; Rojas, M.; Brodie, E.L.; Keller, K.; Huber, T.; Dalevi, D.; Hu, P.; Andersen, G.L. Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 5069–5072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schloss, P.D.; Westcott, S.L.; Ryabin, T.; Hall, J.R.; Hartmann, M.; Hollister, E.B.; Lesniewski, R.A.; Oakley, B.B.; Parks, D.H.; Robinson, C.J.; et al. Introducing mothur: Open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 7537–7541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozupone, C.; Knight, R. UniFrac: A new phylogenetic method for comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 8228–8235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langille, M.G.I.; Zaneveld, J.; Caporaso, J.G.; Mcdonald, D.; Dan, K.; Reyes, J.A.; Clemente, J.C.; Burkepile, D.E.; Thurber, R.L.V.; Knight, R. Predictive functional profiling of microbial communities using 16S rRNA marker gene sequences. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 814–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Guo, C.; Hu, F.; Liu, J.; Mao, S. Hepatic Metabolic Profile Reveals the Adaptive Mechanisms of Ewes to Severe Undernutrition during Late Gestation. Metabolites 2018, 8, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | SF | MF | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 4.79 ± 0.09 | 4.97 ± 0.02 | 0.006 |

| Lactate (μmol/g) | 49.52 ± 5.02 | 98.71 ± 4.59 | <0.001 |

| Acetate (μmol/g) | 153.66 ± 5.44 | 20.35 ± 3.65 | <0.001 |

| Propionate (μmol/g) | 19.04 ± 4.72 | 4.97 ± 0.88 | 0.001 |

| Isobutyrate (μmol/g) | 6.50 ± 0.94 | 0.56 ± 0.04 | <0.001 |

| Total volatile fatty acid (μmol/g) | 179.20 ± 7.34 | 25.88 ± 4.51 | <0.001 |

| Item | SF | MF | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| OTUs | 1571 ± 19 | 1559 ± 114 | 0.248 |

| Ace | 1949 ± 33 | 1559 ± 114 | 0.021 |

| Chao1 | 1949 ± 48 | 1945 ± 101 | 0.564 |

| Shannon | 2.72 ± 0.17 | 2.61 ± 0.31 | 0.772 |

| Simpson | 0.30 ± 0.02 | 0.36 ± 0.07 | 0.037 |

| Compounds | RT a | Mass | VIP | FDR | FC b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organic acids | |||||

| Maleic acid | 1.22 | 116 | 1.31 | <0.001 | 11.86 |

| Phenylacetic acid | 3.63 | 136 | 1.30 | 0.002 | 11.10 |

| Citric acid | 0.88 | 192 | 1.31 | <0.001 | 3.13 |

| Kynurenic acid | 3.56 | 189 | 1.31 | <0.001 | 2.97 |

| 3-Indolecarboxylic acid | 3.56 | 161 | 1.31 | <0.001 | 2.90 |

| Succinic acid | 1.26 | 118 | 1.27 | <0.001 | 2.10 |

| 5-Hydroxyindoleacetate | 3.79 | 191 | 1.29 | <0.001 | 1.99 |

| (E)-p-coumaric acid | 3.87 | 164 | 1.28 | <0.001 | 1.98 |

| Salicylic acid | 3.51 | 138 | 1.30 | <0.001 | 1.77 |

| Glucopyranuronic acid | 0.85 | 194 | 1.29 | 0.002 | 0.03 |

| Malonic acid | 0.85 | 104 | 1.29 | <0.001 | 0.02 |

| Lipids | |||||

| Ethyl linoleate | 12.32 | 308 | 1.50 | <0.001 | 19.66 |

| Dihomo-gamma-linolenic acid | 9.41 | 306 | 1.49 | <0.001 | 11.70 |

| 16-Hydroxy hexadecanoic acid | 9.38 | 272 | 1.24 | <0.001 | 2.19 |

| Stearidonic acid | 7.05 | 276 | 1.20 | 0.002 | 0.54 |

| Gluconolactone | 0.88 | 178 | 1.25 | <0.001 | 0.28 |

| Butyl levulinate | 5.26 | 172 | 1.29 | <0.001 | 0.10 |

| Amino acids and derivatives | |||||

| l-Theanine | 0.86 | 174 | 1.28 | <0.001 | 8.57 |

| Glutamine | 0.83 | 146 | 1.30 | <0.001 | 3.50 |

| O-succinyl-l-homoserine | 1.25 | 219 | 1.28 | <0.001 | 2.31 |

| Glutamic acid | 0.84 | 147 | 1.22 | 0.002 | 2.10 |

| l-Aspartic acid | 0.84 | 133 | 1.21 | 0.002 | 1.74 |

| Arginine | 0.79 | 174 | 1.30 | 0.002 | 0.03 |

| Nucleosides, Nucleotides | |||||

| 2-Deoxypentose | 1.21 | 134 | 1.29 | <0.001 | 4.86 |

| 2’-Deoxyinosine | 1.18 | 252 | 1.27 | <0.001 | 0.45 |

| Hypoxanthine | 1.18 | 136 | 1.28 | <0.001 | 0.42 |

| 8-Hydroxy-deoxyguanosine | 1.18 | 283 | 1.23 | 0.002 | 0.29 |

| Others | |||||

| exo,exo-1,8-Epoxy-p-menthane-2,6-diol | 7.95 | 186 | 1.30 | <0.001 | 11.72 |

| 4-Oxo-4-(3-pyridinyl)butanal | 3.56 | 163 | 1.31 | <0.001 | 2.88 |

| p-Coumaroyltyramine | 4.20 | 283 | 1.22 | 0.002 | 2.07 |

| Phenol | 3.51 | 94 | 1.30 | <0.001 | 1.79 |

| Slaframine | 3.74 | 198 | 1.31 | <0.001 | 0.16 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jin, W.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, K.; Xue, Y.; Xie, F.; Mao, S. Comprehensive Understanding of the Bacterial Populations and Metabolites Profile of Fermented Feed by 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing and Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry. Metabolites 2019, 9, 239. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo9100239

Jin W, Zhang Z, Zhu K, Xue Y, Xie F, Mao S. Comprehensive Understanding of the Bacterial Populations and Metabolites Profile of Fermented Feed by 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing and Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry. Metabolites. 2019; 9(10):239. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo9100239

Chicago/Turabian StyleJin, Wei, Zheng Zhang, Kun Zhu, Yanfeng Xue, Fei Xie, and Shengyong Mao. 2019. "Comprehensive Understanding of the Bacterial Populations and Metabolites Profile of Fermented Feed by 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing and Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry" Metabolites 9, no. 10: 239. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo9100239

APA StyleJin, W., Zhang, Z., Zhu, K., Xue, Y., Xie, F., & Mao, S. (2019). Comprehensive Understanding of the Bacterial Populations and Metabolites Profile of Fermented Feed by 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing and Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry. Metabolites, 9(10), 239. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo9100239