Absolute Configuration of the New 3-epi-cladocroic Acid from the Mediterranean Sponge Haliclona fulva

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. General

2.2. Animal Material

2.3. Extraction and Purification

| 1 | 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position | δH (m, J Hz) | δC | δH (m, J Hz) | δC |

| 1 | - | 178.8 | - | 177.1a |

| 2 | 1.35 (m, 1H) | 19.8 | 1.69 (ddd, J = 8.8, 7.9, 5.4 Hz, 1H) | 17.7 |

| 3 | 1.42 (m, 1H) | 24.1 | 1.30 (m, 1H) | 23.1 |

| 4 | 1.30 (m, 1H) | 33.2 | 1.54 (m, 1H) | 27.1 |

| 5-13 | 1.26 (m, 2H) | 29.3-29.8 | 1.26 (m, 2H) | 29.3-29.8 |

| 14 | 1.41 (m, 2H) | 29.2 | 1.41 (m, 2H) | 29.2 |

| 15 | 2.32 (q, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H) | 30.4 | 2.32 (q, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H) | 30.4 |

| 16 | 6.00 (dt, J = 10.4, 7.3 Hz, 1H) | 146.5 | 6.00 (dt, J = 10.4, 7.3 Hz, 1H) | 146.5 |

| 17 | 5.44 (ddd, J = 10.9, 3.5, 1.4 Hz, 1H) | 108.1 | 5.44 (ddd, J = 10.9, 3.5, 1.4 Hz, 1H) | 108.1 |

| 18 | - | 80.8 | - | 80.8 |

| 19 | 3.07 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H) | 81.3 | 3.07 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H) | 81.3 |

| 20a | 0.78 (ddd, J = 8.0, 6.5, 4.1 Hz, 1H) | 16.5 | 0.96 (dt, J = 10.2, 7.1, 5.2 Hz, 1H) | 14.5 |

| 20b | 1.22 (m, 1H) | 16.5 | 1.08 (ddd, J = 8.5, 8.0, 4.6 Hz, 1H) | 14.5 |

2.4. Methyl Esterification of 1 and 2

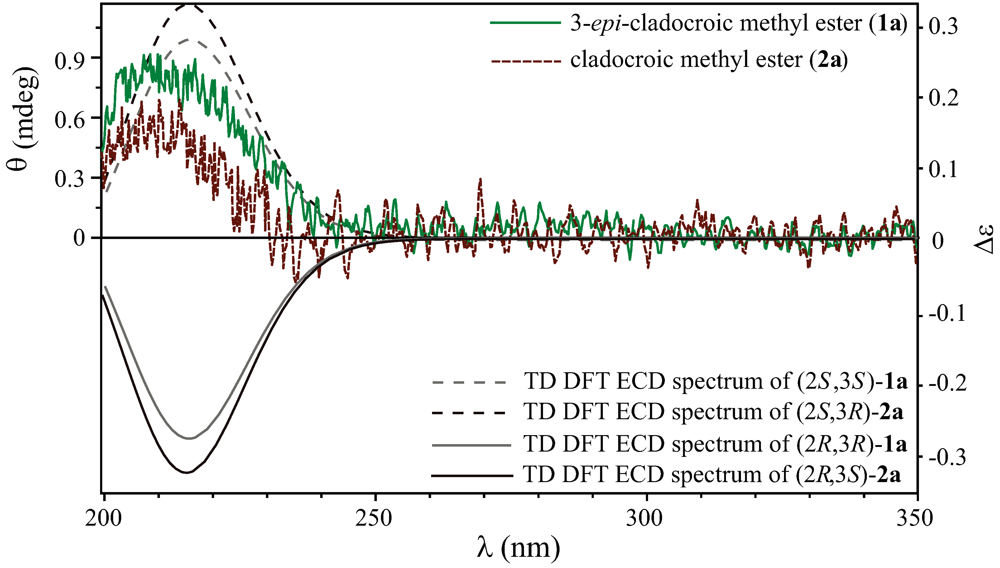

= + 21.5 (MeOH, c 0.1); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 210 (0.34); CD (MeOH, c 3.15× 10−4 M) ∆ε (λmax nm) 0.81 (212); 1H NMR (500 MHz) NMR (CDCl3), see Table 2; EIMS m/z 318 M+•; HRESIMS m/z 341.24362 [M+Na]+; calcd for C21H34O2Na, 341.24510, ∆ -4.33618 ppm).

= + 21.5 (MeOH, c 0.1); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 210 (0.34); CD (MeOH, c 3.15× 10−4 M) ∆ε (λmax nm) 0.81 (212); 1H NMR (500 MHz) NMR (CDCl3), see Table 2; EIMS m/z 318 M+•; HRESIMS m/z 341.24362 [M+Na]+; calcd for C21H34O2Na, 341.24510, ∆ -4.33618 ppm).

= + 12.1 (MeOH, c 0.1); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 210 (0.54); CD (MeOH, c 3.15× 10−4 M) ∆ε (λmax nm) 0.32 (212); 1H NMR (500 MHz) NMR (CDCl3), see Table 2; EIMS m/z 318 M+•; HRESIMS m/z 341.24353 [M+Na]+; calcd for C21H34O2Na, 341.24510, ∆ -4.60447 ppm).

= + 12.1 (MeOH, c 0.1); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 210 (0.54); CD (MeOH, c 3.15× 10−4 M) ∆ε (λmax nm) 0.32 (212); 1H NMR (500 MHz) NMR (CDCl3), see Table 2; EIMS m/z 318 M+•; HRESIMS m/z 341.24353 [M+Na]+; calcd for C21H34O2Na, 341.24510, ∆ -4.60447 ppm). | 1a | 2a | |

|---|---|---|

| Position | δH (m, J Hz) | δH (m, J Hz) |

| 1 | - | - |

| 2 | 1.35 (m, 1H) | 1.68 (m, 1H) |

| 3 | 1.39 (m, 1H) | 1.30 (m, 1H) |

| 4 | 1.30 (m, 1H) | 1.66 (m, 1H) |

| 5-13 | 1.25 (m, 2H) | 1.25 (m, 2H) |

| 14 | 1.31 (m, 2H) | 1.30 (m, 2H) |

| 15 | 2.32 (q, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H) | 2.32 (q, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H) |

| 16 | 6.00 (dt, J = 10.4, 7.3 Hz, 1H) | 6.00 (dt, J = 10.4, 7.3 Hz, 1H) |

| 17 | 5.44 (ddd, J = 10.9, 3.5, 1.4 Hz, 1H) | 5.44 (ddd, J = 10.9, 3.5, 1.4 Hz, 1H) |

| 18 | - | - |

| 19 | 3.07 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H) | 3.07 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H) |

| 20a | 0.69 (ddd, J = 7.5, 6.7, 4.0 Hz, 1H) | 0.96 (dt, J = 9.9, 7.1, 4.7 Hz, 1H) |

| 20b | 1.14 (ddd, J = 8.1, 5.0, 4.2 Hz, 1H) | 1.01 (ddd, J = 11.8, 8.0, 4.5 Hz, 1H) |

| Me | 3.67 (s, 3H) | 3.67 (s, 3H) |

2.5. Gas Chromatography Analysis

2.6. Computational Details

peak height and ∆E and R are the excitation energies and the rotatory strengths for transition i , respectively. For the Figure 2, Rvel was used.

peak height and ∆E and R are the excitation energies and the rotatory strengths for transition i , respectively. For the Figure 2, Rvel was used.

3. Results and Discussion

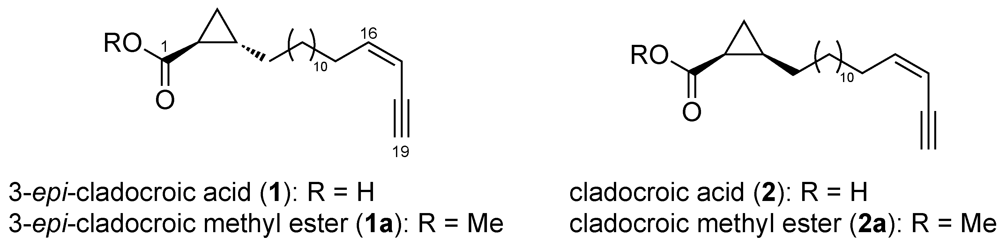

3.1. Structure Elucidation

3.2. Determination of the Absolute Configuration

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgements

References

- Van Soest, R.; Boury-Esnault, N.; Hooper, J.; Rützler, K.; de Voogd, N.; Alvarez de Glasby, B.; Hajdu, E.; Pisera, A.; Manconi, R.; Schoenberg, C.; et al. World Porifera Database. 2011. Available online: http://www.marinespecies.org/ (accessed on 16 December 2012).

- Cimino, G.; de Stefano, S. New acetylenic compounds from the sponge Reniera fulva. Tetrahedron Lett. 1977, 18, 1325–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, M.J.; Zubía, E.; Carballo, J.L.; Salvá, J. Fulvinol, a new long-chain diacetylenic metabolite from the sponge Reniera fulva. J. Nat. Prod. 1996, 59, 1069–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubía, E.; Ortega, M.J.; Carballo, J.L.; Salvá, J. Sesquiterpene hydroquinones from the sponge Reniera mucosa. Tetrahedron 1994, 50, 8153–8160. [Google Scholar]

- Defant, A.; Mancini, I.; Raspor, L.; Guella, G.; Turk, T.; Sepčić, K. New structural insights into saraines A, B, and C, macrocyclic alkaloids from the mediterranean sponge Reniera (Haliclona) sarai. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 2011, 3761–3767. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, K.H.; Kang, G.W.; Jeon, J.E.; Lim, C.; Lee, H.S.; Sim, C.J.; Oh, K.B.; Shin, J. Haliclonin a, a new macrocyclic diamide from the sponge Haliclona sp. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 1713–1716. [Google Scholar]

- Timm, C.; Mordhorst, T.; Köck, M. Synthesis of 3-alkyl pyridinium alkaloids from the arctic sponge Haliclona viscosa. Mar. Drugs 2010, 8, 483–497. [Google Scholar]

- Sakai, R.; Higa, T.; Jefford, C.W.; Bernardinelli, G. Manzamine a, a novel antitumor alkaloid from a sponge. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986, 108, 6404–6405. [Google Scholar]

- Barrow, R.; Capon, R. Alkyl and alkenyl resorcinols from an australian marine sponge, Haliclona sp. (haplosclerida : Haliclonidae). Aust. J. Chem. 1991, 44, 1393–1405. [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh, Y.M.; Djerassi, C. Steroids from sponges. Tetrahedron 1974, 30, 4095–4103. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.Y.S.; Abrell, L.M.; Avelar, A.; Borgeson, B.M.; Crews, P. New hirsutane based sesquiterpenes from salt water cultures of a marine sponge-derived fungus and the terrestrial fungus Coriolus consors. Tetrahedron 1998, 54, 7335–7342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.A.; Gustafson, K.R.; Boswell, J.L.; Boyd, M.R. Haligramides a and b, two new cytotoxic hexapeptides from the marine sponge Haliclona nigra. J. Nat. Prod. 2000, 63, 956–959. [Google Scholar]

- Nuzzo, G.; Ciavatta, M.L.; Villani, G.; Manzo, E.; Zanfardino, A.; Varcamonti, M.; Gavagnin, M. Fulvynes, antimicrobial polyoxygenated acetylenes from the mediterranean sponge Haliclona fulva. Tetrahedron 2012, 68, 754–760. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, J.; Seo, Y.; Cho, K.W.; Rho, J.R.; Paul, V.J. Osirisynes A-F, highly oxygenated polyacetylenes from the sponge Haliclona osiris. Tetrahedron 1998, 54, 8711–8720. [Google Scholar]

- D’Auria, M.V.; Paloma, L.G.; Minale, L.; Riccio, R.; Zampella, A.; Debitus, C. Metabolites of the new caledonian sponge Claodocroce incurvata. J. Nat. Prod. 1993, 56, 418–423. [Google Scholar]

- Diedrich, C.; Grimme, S. Systematic investigation of modern quantum chemical methods to predict electronic circular dichroism spectra. J. Phys. Chem. A 2003, 107, 2524–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laville, R.; Genta-Jouve, G.; Urda, C.; Fernández, R.; Thomas, O.P.; Reyes, F.; Amade, P. Njaoaminiums A, B, and C: Cyclic 3-alkylpyridinium salts from the marine sponge Reniera sp. Molecules 2009, 14, 4716–4724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pescitelli, G.; Kurtán, T.; Krohn, K. Assignment of the Absolute Configurations of Natural Products by Means of Solid-State Electronic Circular Dichroism and Quantum Mechanical Calculations. In Comprehensive Chiroptical Spectroscopy; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 217–249. [Google Scholar]

- Goto, H.; Osawa, E. Corner flapping: A simple and fast algorithm for exhaustive generation of ring conformations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989, 111, 8950–8951. [Google Scholar]

- Goto, H.; Osawa, E. Further developments in the algorithm for generating cyclic conformers. Test with cycloheptadecane. Tetrahedron 1992, 33, 1343–1346. [Google Scholar]

- Goto, H.; Osawa, E. An efficient algorithm for searching low-energy conformers of cyclic and acyclic molecules. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2 1993, 2, 187–198. [Google Scholar]

- Goto, H.; Ohta, K.; Kamakura, T.; Obata, S.; Nakayama, N.; Matsumoto, T.; Osawa, E. CONFLEX 6; Conflex Corp: Tokyo-Yokohama, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Montgomery, J.A., Jr.; Vreven, T.; Kudin, K.N.; Burant, J.C.; et al. Gaussian 03, Revision C.01. Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.; Yang, W.; Parr, R.G. Development of the colle-salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 785–789. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasi, J.; Mennucci, B.; Cammi, R. Quantum mechanical continuum solvation models. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 2999–3094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, P.J.; Harada, N. ECD cotton effect approximated by the gaussian curve and other methods. Chirality 2010, 22, 229–233. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.Y.S.; Kuramoto, M.; Uemura, D.; Yamada, A.; Yamaguchi, K.; Yazawa, K. Three novel anti-microfouling nitroalkyl pyridine alkaloids from the okinawan marine sponge Callyspongia sp. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996, 37, 1813–1816. [Google Scholar]

- Poulter, C.D.; Boikess, R.S.; Brauman, J.I.; Winstein, S. Shielding effects of a cyclopropane ring. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1972, 94, 2291–2296. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Sha, Y. A convenient synthesis of amino acid methyl esters. Molecules 2008, 13, 1111–1119. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, G. A new look at carbonyl electronic transitions. J. Chem. Educ. 1990, 67, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Genta-Jouve, G.; Thomas, O.P. Absolute Configuration of the New 3-epi-cladocroic Acid from the Mediterranean Sponge Haliclona fulva. Metabolites 2013, 3, 24-32. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo3010024

Genta-Jouve G, Thomas OP. Absolute Configuration of the New 3-epi-cladocroic Acid from the Mediterranean Sponge Haliclona fulva. Metabolites. 2013; 3(1):24-32. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo3010024

Chicago/Turabian StyleGenta-Jouve, Grégory, and Olivier P. Thomas. 2013. "Absolute Configuration of the New 3-epi-cladocroic Acid from the Mediterranean Sponge Haliclona fulva" Metabolites 3, no. 1: 24-32. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo3010024

APA StyleGenta-Jouve, G., & Thomas, O. P. (2013). Absolute Configuration of the New 3-epi-cladocroic Acid from the Mediterranean Sponge Haliclona fulva. Metabolites, 3(1), 24-32. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo3010024