Characterization of Volatile Organic Compounds Released by Penicillium expansum and Penicillium polonicum

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strains and Media

2.2. GC-MS Detection of VOCs Emitted by Penicillium Species

3. Results

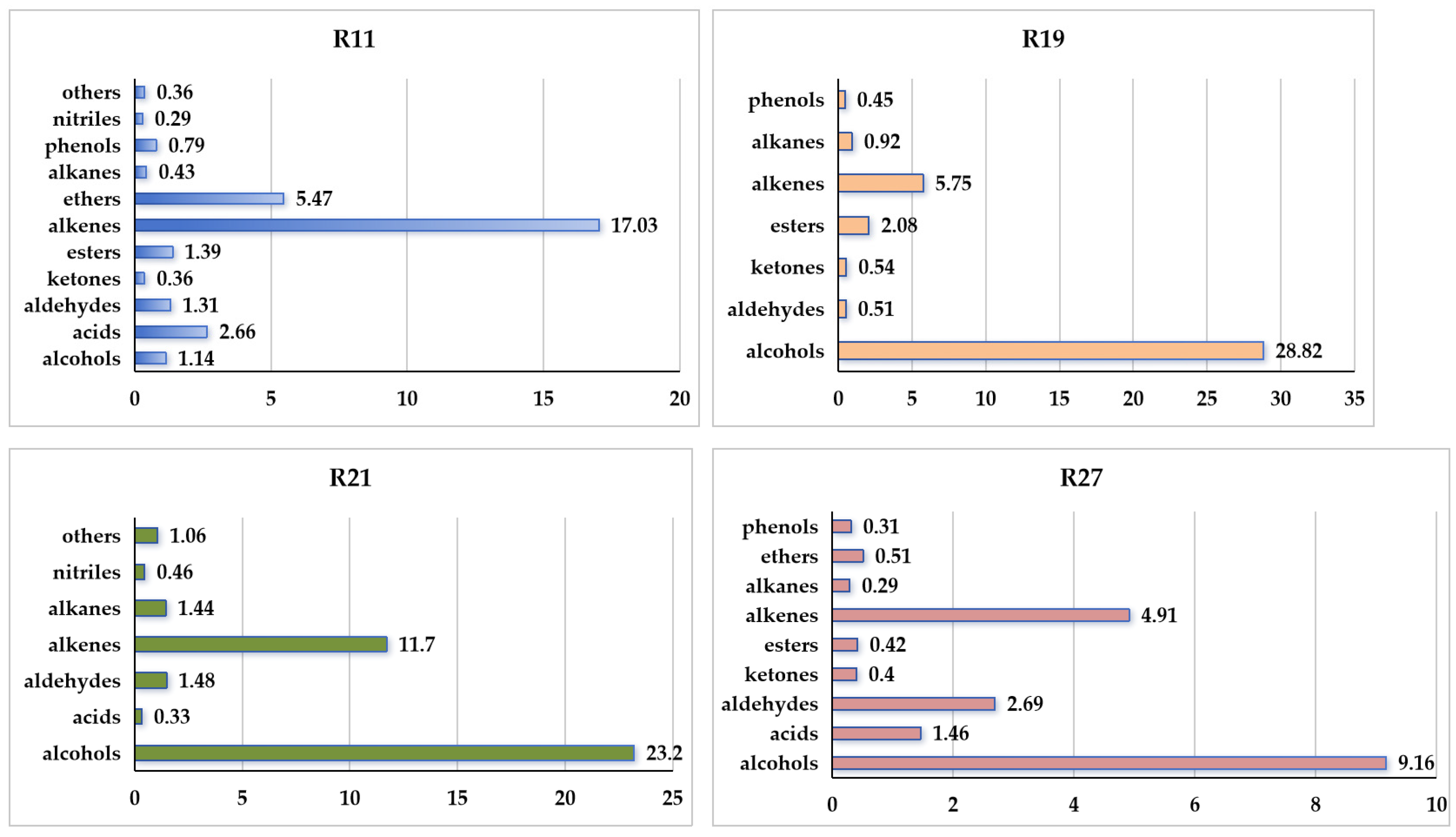

3.1. Analyses of VOC Profiles Emitted by Penicillium expansum

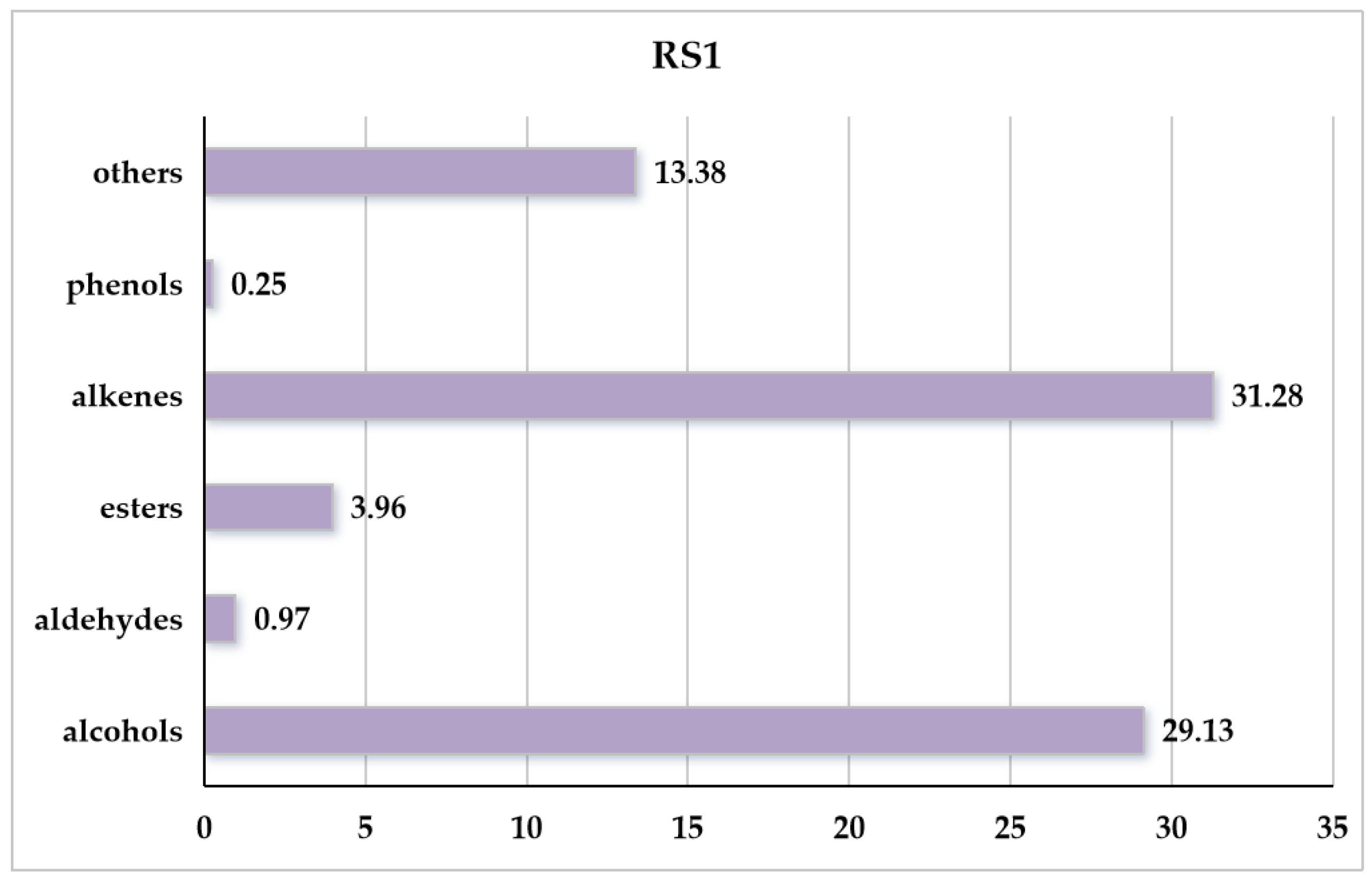

3.2. Analysis of VOC Profile of Penicillium polonicum RS1

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barreiro, C.; García-Estrada, C. Proteomics and Penicillium chrysogenum: Unveiling the secrets behind penicillin production. J. Proteom. 2019, 198, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrone, G.; Susca, A. Penicillium species and their associated mycotoxins. Mycotoxigenic Fungi Methods Protoc. 2016, 1542, 107–119. [Google Scholar]

- Alazemi, M.S.; Alshaikh, N.A.; Stephenson, S.L.; Ameen, F. Cost-effective biopesticide production from agro-industrial and shell wastes using endophytic Penicillium sp. SAUDI-F26 for the management of Agrotis ipsilon. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2025, 132, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, G.; Zhao, H.; Pennerman, K.K.; Jurick, W.M.; Fu, M.; Bu, L.; Guo, A.; Bennett, J.W. Genomic analyses of Penicillium species have revealed patulin and citrinin gene clusters and novel loci involved in oxylipin production. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlshøj, K.; Nielsen, P.V.; Larsen, T.O. Prediction of Penicillium expansum spoilage and patulin concentration in apples used for apple juice production by electronic nose analysis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 4289–4298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shan, T.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, C.; Yue, T. Evaluation of Penicillium expansum for growth, patulin accumulation, nonvolatile compounds and volatile profile in kiwi juices of different cultivars. Food Chem. 2017, 228, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chu, T.; Zhang, J.; Ma, D.; Hui, H.; Kurtovic, I.; Sheng, Q.; Yuan, Y.; Yue, T.; Feng, K. The dynamic and diverse volatile profiles provide new insight into the infective characteristics of Penicillium expansum in postharvest fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2025, 219, 113256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.W.; Lee, S.M.; Seo, J.-A.; Kim, Y.-S. Effects of pH and cultivation time on the formation of styrene and volatile compounds by Penicillium expansum. Molecules 2019, 24, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, G.; Jurick, W.M.; Zhao, G.; Bennett, J.W. New names for three Penicillium strains based on updated barcoding and phylogenetic analyses. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2021, 10, e00466-00421. [Google Scholar]

- Vasić, M. First report of Penicillium polonicum causing blue mold on stored onion (Allium cepa) in Serbia. Plant Dis. 2014, 98, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleman, I.; Rosberg, A.K.; Guzhva, O.; Karlsson, M.E.; Becher, P.G.; Mogren, L. Headspace volatile organic compounds as indicators of Fusarium basal plate rot and Penicillium rot in stored onion bulbs. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2025, 114, 102775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, M.J.; Bartholomew, H.P.; Lichtner, F.; Gaskins, V.L.; Jurick, W.M. First report of blue mold caused by Penicillium polonicum on apple in the United States. Plant Dis. 2022, 106, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, A.M.A.; Hashem, A.H.; Abdelaziz, A.M. Occurrence of toxigenic Penicillium polonicum in retail green table olives from the Saudi Arabia market. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2019, 21, 101314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lu, X.; He, C.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hu, L.; Qing, Q.; Zhu, M.; Liu, Z.; Xiao, Y. Characterizing and decoding the dynamic alterations of volatile organic compounds and non-volatile metabolites of dark tea by solid-state fermentation with Penicillium polonicum based on GC–MS, GC-IMS, HPLC, E-nose and E-tongue. Food Res. Int. 2025, 209, 116279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Lv, Y.; Hao, J.; Chen, H.; Huang, Y.; Liu, C.; Huang, H.; Ma, Y.; Yang, X. Two new compounds of Penicillium polonicum, an endophytic fungus from Camptotheca acuminata Decne. Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 34, 1879–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inamdar, A.A.; Morath, S.; Bennett, J.W. Fungal volatile organic compounds: More than just a funky smell? Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 74, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisskopf, L.; Schulz, S.; Garbeva, P. Microbial volatile organic compounds in intra-kingdom and inter-kingdom interactions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giorgio, A.; De Stradis, A.; Lo Cantore, P.; Iacobellis, N.S. Biocide effects of volatile organic compounds produced by potential biocontrol rhizobacteria on Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. Ebert, B.; Halbfeld, C.; M. Blank, L. Exploration and exploitation of the yeast volatilome. Curr. Metabolomics 2017, 5, 102–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.R.; Pinto, J.; Azevedo, A.I.; Barros-Silva, D.; Jerónimo, C.; Henrique, R.; de Lourdes Bastos, M.; Guedes de Pinho, P.; Carvalho, M. Identification of a biomarker panel for improvement of prostate cancer diagnosis by volatile metabolic profiling of urine. Br. J. Cancer 2019, 121, 857–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stead, Z.; Capuano, R.; Di Natale, C.; Pain, A. The volatilome signatures of Plasmodium falciparum parasites during the intraerythrocytic development cycle in vitro under exposure to artemisinin drug. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 20167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, G.; Moore, G.G.; Bennett, J.W. Diversity and functions of fungal VOCs with special reference to the multiple bioactivities of the mushroom alcohol. Mycology 2025, 16, 1011–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennerman, K.K.; Yin, G.; Bennett, J.W. Eight-carbon volatiles: Prominent fungal and plant interaction compounds. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Hung, R.; Bennett, J.W. An Overview of Fungal Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs). In Fungal Associations; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 83–111. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtner, F.J.; Gaskins, V.L.; Cox, K.D.; Jurick, W.M. Global transcriptomic responses orchestrate difenoconazole resistance in Penicillium spp. causing blue mold of stored apple fruit. BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Yin, G.; Inamdar, A.; Luo, J.; Zhang, N.; Yang, I.; Buckley, B.; Bennett, J. Volatile organic compounds emitted by filamentous fungi isolated from flooded homes after hurricane Sandy show toxicity in a Drosophila bioassay. Indoor Air 2017, 27, 518–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, T.O. Volatiles in Fungal Taxonomy. In Chemical Fungal Taxonomy; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; pp. 263–287. [Google Scholar]

- Scognamiglio, J.; Jones, L.; Letizia, C.; Api, A. Fragrance material review on phenylethyl alcohol. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2012, 50, S224–S239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, E.K.; Sung, C.K. Phenylethyl alcohol (PEA) application slows fungal growth and maintains aroma in strawberry. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2007, 45, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouissi, W.; Ugolin, L.; Martini, C.; Lazzeri, L.; Mari, M. Control of postharvest fungal pathogens by antifungal compounds from Penicillium expansum. J. Food Prot. 2013, 76, 1879–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Lancker, F.; Adams, A.; Delmulle, B.; De Saeger, S.; Moretti, A.; Van Peteghem, C.; De Kimpe, N. Use of headspace SPME-GC-MS for the analysis of the volatiles produced by indoor molds grown on different substrates. J. Environ. Monit. 2008, 10, 1127–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, N.A.; Lamb, J.C.; Brown, S.M.; Neal, B.H. A review of the developmental and reproductive toxicity of styrene. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2000, 32, 228–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niaz, K.; Mabqool, F.; Khan, F.; Ismail Hassan, F.; Baeeri, M.; Navaei-Nigjeh, M.; Hassani, S.; Gholami, M.; Abdollahi, M. Molecular mechanisms of action of styrene toxicity in blood plasma and liver. Environ. Toxicol. 2017, 32, 2256–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Soria, A.; Picciotti, U.; Lopez-Moya, F.; Lopez-Cepero, J.; Porcelli, F.; Lopez-Llorca, L.V. Volatile organic compounds from entomopathogenic and nematophagous fungi, repel banana black weevil (Cosmopolites sordidus). Insects 2020, 11, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, R.; Prabhu, G.; Prasad, M.; Mishra, M.; Chaudhary, M.; Srivastava, R. Penicillium. In Beneficial Microbes in Agro-Ecology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 651–667. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, L.; Frey, T.; Haag, F.; Frank, S.; Hoffmann, S.; Laska, M.; Steinhaus, M.; Neuhaus, K.; Krautwurst, D. Geosmin, a food-and water-deteriorating sesquiterpenoid and ambivalent semiochemical, activates evolutionary conserved receptor OR11A1. J. Agri Food Chem. 2024, 72, 15865–15874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaroubi, L.; Ozugergin, I.; Mastronardi, K.; Imfeld, A.; Law, C.; Gélinas, Y.; Piekny, A.; Findlay, B.L. The ubiquitous soil terpene geosmin acts as a warning chemical. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 88, e00093-00022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, A.M.; Angeloni, S.; Nzekoue, F.K.; Abouelenein, D.; Sagratini, G.; Caprioli, G.; Torregiani, E. An overview on truffle aroma and main volatile compounds. Molecules 2020, 25, 5948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeem, M.; Rajarao, G.K.; Nordenhem, H.; Nordlander, G.; Borg-Karlson, A.K. Penicillium expansum volatiles reduce pine weevil attraction to host plants. J. Chem. Ecol. 2013, 39, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicoletti, R.; Andolfi, A.; Becchimanzi, A.; Salvatore, M.M. Anti-insect properties of Penicillium secondary metabolites. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Splivallo, R.; Ottonello, S.; Mello, A.; Karlovsky, P. Truffle volatiles: From chemical ecology to aroma biosynthesis. New Phytol. 2011, 189, 688–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaimand, K.; Rezaee, M.-B.; Azimi, R.; Fekri-Qomi, S.; Yahyazadeh, M.; Karimi, S.; Hatami, F. A major loss of phenyl ethyl alcohol by the distillation procedure of Rosa damascene mill. J. Med. Plants By-Prod. 2023, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, J.K.; Dogara, A.M.; Khalaf, M.A.; Al-Taey, D.K.; Alsaffar, M.F. Study of The Chemical Composition of Syzygium Cumini (L.) Skeels. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2024; p. 052036. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E.-M.; Woo, H.M.; Tian, T.; Yilmaz, S.; Javidpour, P.; Keasling, J.D.; Lee, T.S. Autonomous control of metabolic state by a quorum sensing (QS)-mediated regulator for bisabolene production in engineered E. coli. Metab. Eng. 2017, 44, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.; Yang, S.; Jeon, B.B.; Song, E.; Lee, H. Terpene compound composition and antioxidant activity of essential oils from needles of Pinus densiflora, Pinus koraiensis, Abies holophylla, and Juniperus chinensis by harvest period. Forests 2024, 15, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R.; Jager, V.D.; Zühlke, D.; Wolff, C.; Bernhardt, J.; Cankar, K.; Beekwilder, J.; Ijcken, W.V.; Sleutels, F.; Boer, W.D. Fungal volatile compounds induce production of the secondary metabolite Sodorifen in Serratia plymuthica PRI-2C. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Mas, M.C.; Rambla, J.L.; López-Gresa, M.P.; Blázquez, M.A.; Granell, A. Volatile compounds in citrus essential oils: A comprehensive review. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasisht, R.; Yadav, J.; Agnihotri, S. Fungal Metabolites as Natural Flavor Enhancers. In Fungal Additives and Bioactives in Food Processing Industries: Challenges and Prospects; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 169–209. [Google Scholar]

- Jenis, J.; Kudaibergen, A.; Akzhigitova, Z.; Muzaffarova, N.; Karunakaran, T.; Shah, A.B.; Baiseitova, A.; Aisa, H.A. Exploring artemisia for skin diseases: A natural approach to dermatological therapy. 2025. preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Peak No. | Name | Relative Amount (%) * | CAS ID | Formula | Structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

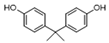

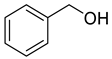

| Alcohols | 4 | 2-phenylethanol | 0.33 ± 0.04 | 000060-12-8 | C8H10O |  |

| 27 | 3,6,6-trimethyl-2-norpinanol | 0.54 ± 0.06 | 029548-09-2 | C10H18O |  | |

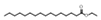

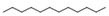

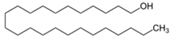

| 32 | 1-octadecanol | 0.27 ± 0.08 | 000112-92-5 | C18H38O |  | |

| Acids | 1 | acetic acid | 0.77 ± 0.06 | 0000064-19-7 | C2H4O2 |  |

| 3 | 2-amino-5-methyl-benzoic acid | 0.79 ± 0.07 | 002941-78-8 | C8H9NO2 |  | |

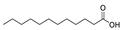

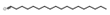

| 16 | dodecanoic acid | 0.49 ± 0.07 | 000143-07-7 | C12H24O2 |  | |

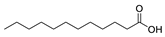

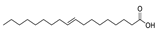

| 28 | (z, z)-9,12-octadecadienoic acid | 0.30 ± 0.04 | 000060-33-3 | C18H32O2 |  | |

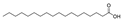

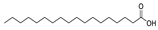

| 30 | octadecanoic acid | 0.31 ± 0.04 | 000057-11-4 | C18H36O2 |  | |

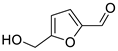

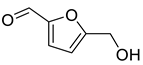

| Aldehydes | 7 | 5-(hydroxymethyl)-2-furancarboxaldehyde | 0.67 ± 0.06 | 000067-47-0 | C6H6O3 |  |

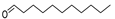

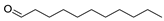

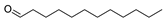

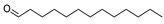

| 10 | tridecanal | 0.29 ± 0.04 | 010486-19-8 | C13H26O |  | |

| 14 | octadecanal | 0.35 ± 0.04 | 000638-66-4 | C18H36O |  | |

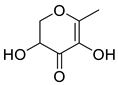

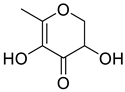

| Ketones | 5 | 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl-4H-pyran-4-one | 0.36 ± 0.06 | 028564-83-2 | C6H8O4 |  |

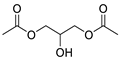

| Esters | 8 | diacetate-1,2,3-propanetriol | 0.24 ± 0.04 | 025395-31-7 | C7H12O5 |  |

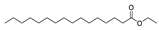

| 26 | hexadecanoic acid ethyl ester | 0.71 ± 0.05 | 000628-97-7 | C18H36O2 |  | |

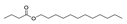

| 31 | butyric acid dodecyl ester | 0.44 ± 0.04 | 003724-61-6 | C16H32O2 |  | |

| Alkenes | 2 | styrene | 16.24 ± 0.67 a | 000100-42-5 | C8H8 |  |

| 29 | 1-eicosene | 0.79 ± 0.02 | 003452-07-1 | C20H4O |  | |

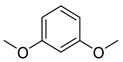

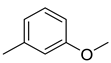

| Ethers | 6 | 1,3-dimethoxy-benzene | 5.47 ± 0.06 a | 000151-10-0 | C8H10O2 |  |

| Alkanes | 17 | 1,2,3-trimethyl-cyclohexane | 0.43 ± 0.06 | 001678-97-3 | C9H18 |  |

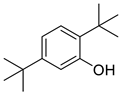

| Phenols | 15 | 2,5-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-phenol | 0.79 ± 0.08 | 005875-45-6 | C14H22O |  |

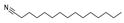

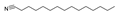

| Nitriles | 21 | pentadecanenitrile | 0.29 ± 0.02 | 018300-91-9 | C15H29N |  |

| Others | 11 | cis-1,4-dimethyl-cyclooctane | 0.36 ± 0.06 | 013151-99-0 | C10H20 |  |

| Category | Peak No. | Name | Relative Amount (%) * | CAS ID | Formula | Structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohols | 1 | ethyl alcohol | 5.64 ± 0.16 | 000064-17-5 | C2H6O |  |

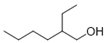

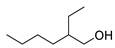

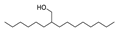

| 3 | 2-ethyl-1-hexanol | 0.69 ± 0.09 | 000104-76-7 | C8H18O |  | |

| 4 | 2-phenylethanol | 14.63 ± 0.85 | 000060-12-8 | C8H10O |  | |

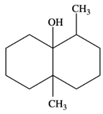

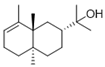

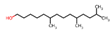

| 7 | geosmin (trans-1,10-dimethyl-trans-9-decalol) | 6.94 ± 0.70 | 1000121-76-3 | C12H22O |  | |

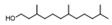

| 8 | 3,7,11-trimethyl-1-dodecanol | 0.41 ± 0.09 | 006750-34-1 | C15H32O |  | |

| 14 | [2R-(2α,4aα,8aβ)]-1,2,3,4,4a,5,6,8a-octahydro-α, α,4a,8-tetramethyl-2-naphthalenemethanol | 0.51 ± 0.07 | 000473-16-5 | C15H26O |  | |

| Aldehydes | 15 | octadecanal | 0.51 ± 0.05 | 000638-66-4 | C18H36O |  |

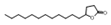

| Ketones | 24 | 5-dodecyldihydro-2(3H)-furanone | 0.54 ± 0.04 | 000730-46-1 | C16H30O2 |  |

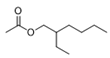

| Esters | 5 | acetic acid 2-ethylhexyl ester | 0.64 ± 0.06 | 000103-09-3 | C10H20O2 |  |

| 23 | hexadecanoic acid ethyl ester | 0.87 ± 0.08 | 000628-97-7 | C18H36O2 |  | |

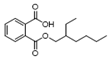

| 26 | 1,2-benzenedicarboxylic acid mono(2-ethylhexyl) ester | 0.57 ± 0.09 | 004376-20-9 | C16H22O4 |  | |

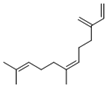

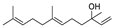

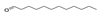

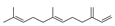

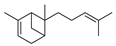

| Alkenes | 9 | (Z)-7,11-dimethyl-3-methylene-1,6,10-dodecatriene | 4.25 ± 0.15 | 028973-97-9 | C15H24 |  |

| 13 | (E)-2-tridecene | 0.82 ± 0.06 | 041446-58-6 | C13H26 |  | |

| 16 | 3,12-diethyl-2,5,9-tetradecatriene | 0.68 ± 0.08 | 074685-87-3 | C18H32 |  | |

| Alkanes | 2 | 4-methyl-2-pentanamine | 0.44 ± 0.06 | 000108-09-8 | C6H15N |  |

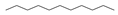

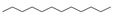

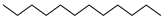

| 6 | dodecane | 0.48 ± 0.05 | 000112-40-3 | C12H26 |  | |

| Phenols | 25 | 4,4′-(1-methylethylidene)bis-phenol | 0.45 ± 0.05 | 000080-05-7 | C15H16O2 |  |

| Category | Peak No. | Name | Relative Amount (%) * | CAS ID | Formula | Structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohols | 1 | ethyl alcohol | 6.62 ± 0.21 | 000064-17-5 | C2H6O |  |

| 4 | 2-ethyl-1-hexanol | 0.88 ± 0.10 | 000104-76-7 | C8H18O |  | |

| 6 | 2-phenylethanol | 9.12 ± 0.53 | 000060-12-8 | C8H10O |  | |

| 16 | 6,10,13-trimethyltetradecanol | 0.49 ± 0.10 | 1000131-71-0 | C17H36O |  | |

| 24 | (E)-3,7,11-trimethyl-1,6,10-dodecatrien-3-ol | 2.96 ± 0.48 | 040716-66-3 | C15H26O |  | |

| 26 | 2-dodecen-1-ol | 0.64 ± 0.07 | 022104-81-0 | C12H24O |  | |

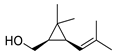

| 27 | chrysanthemyl alcohol | 2.18 ± 0.18 | 018383-59-0 | C10H18O |  | |

| 36 | 2-hexyl-1-decanol | 0.31 ± 0.06 | 002425-77-6 | C16H34O |  | |

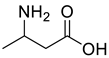

| Acids | 2 | dl-3-aminobutyric acid | 0.33 ± 0.04 | 002835-82-7 | C4H9NO2 |  |

| Aldehydes | 10 | undecanal | 0.73 ± 0.06 | 000112-44-7 | C11H22O |  |

| 14 | dodecanal | 0.75 ± 0.06 | 000112-54-9 | C12H24O |  | |

| Alkenes | 3 | styrene | 0.36 ± 0.13 | 000100-42-5 | C8H8 |  |

| 9 | 1-tridecene | 0.50 ± 0.15 | 002437-56-1 | C13H26 |  | |

| 11 | 1-tetradecene | 0.30 ± 0.05 | 001120-36-1 | C14H28 |  | |

| 15 | (E)-3-octadecene | 0.75 ± 0.07 | 007206-19-1 | C18H36 |  | |

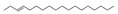

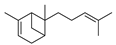

| 17 | 2,6-dimethyl-6-(4-methyl-3-pentenyl)-bicyclo [3.1.1]hept-2-ene | 0.59 ± 0.11 | 017699-05-7 | C15H24 |  | |

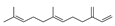

| 19 | (E)-7,11-dimethyl-3-methylene-1,6,10-dodecatriene | 8.83 ± 0.73 | 018794-84-8 | C15H24 |  | |

| 28 | (S)-1-methyl-4-(5-methyl-1-methylene-4-hexenyl)-cyclohexene | 0.37 ± 0.09 | 000495-61-4 | C15H24 |  | |

| Alkanes | 5 | undecane | 0.51 ± 0.07 | 001120-21-4 | C11H24 |  |

| 7 | dodecane | 0.93 ± 0.20 | 000112-40-3 | C12H26 |  | |

| Nitriles | 32 | pentadecanenitrile | 0.46 ± 0.07 | 018300-91-9 | C15H29N |  |

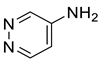

| Others | 8 | 4-pyridazinamine | 1.06 ± 0.09 | 020744-39-2 | C4H5N3 |  |

| Category | Peak No. | Name | Relative Amount (%) * | CAS ID | Formula | Structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohols | 1 | ethyl alcohol | 1.27 ± 0.07 | 000064-17-5 | C2H6O |  |

| 4 | 2-phenylethanol | 6.98 ± 0.26 | 000060-12-8 | C8H10O |  | |

| 12 | 1-tetracosanol | 0.33 ± 0.05 | 000506-51-4 | C24H50O |  | |

| 18 | trans-1-methyl-1,2-cyclohexanediol | 0.58 ± 0.08 | 019534-08-8 | C7H14O2 |  | |

| Acids | 17 | dodecanoic acid | 0.54 ± 0.06 | 000143-07-7 | C12H24O2 |  |

| 28 | (E)-9-octadecenoic acid | 0.56 ± 0.05 | 000112-79-8 | C18H34O2 |  | |

| 29 | octadecanoic acid | 0.36 ± 0.06 | 000057-11-4 | C18H36O2 |  | |

| Aldehydes | 7 | 5-(hydroxymethyl)-2-furancarboxaldehyde | 0.80 ± 0.05 | 000067-47-0 | C6H6O3 |  |

| 8 | undecanal | 0.64 ± 0.06 | 000112-44-7 | C11H22O |  | |

| 10 | dodecanal | 0.52 ± 0.04 | 000112-54-9 | C12H24O |  | |

| 19 | tridecanal | 0.73 ± 0.13 | 010486-19-8 | C13H26O |  | |

| Ketones | 5 | 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl-4H-pyran-4-one | 0.40 ± 0.06 | 028564-83-2 | C6H8O4 |  |

| Esters | 27 | hexadecanoic acid ethyl ester | 0.42 ± 0.05 | 000628-97-7 | C18H36O2 |  |

| Alkenes | 11 | 2,6-dimethyl-6-(4-methyl-3-pentenyl)-bicyclo[3.1.1]hept-2-ene | 0.52 ± 0.04 | 017699-05-7 | C15H24 |  |

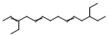

| 13 | 7,11-dimethyl-3-methylene-(E)-1,6,10-dodecatriene | 4.39 ± 0.16 | 018794-84-8 | C15H24 |  | |

| Alkanes | 6 | dodecane | 0.29 ± 0.06 | 000112-40-3 | C12H26 |  |

| Ethers | 2 | 1-methoxy-3-methyl-benzene | 0.51 ± 0.04 | 000100-84-5 | C8H10O |  |

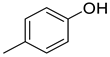

| Phenols | 3 | 4-methyl-phenol | 0.31 ± 0.04 | 000106-44-5 | C7H8O |  |

| Category | Peak No. | Name | Relative Amount (%) * | CAS ID | Formula | Structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohols | 4 | 2-phenylethanol | 0.71 ± 0.04 | 000060-12-8 | C8H10O |  |

| 23 | 3,4-dimethylbenzyl alcohol | 28.15 ± 1.00 | 006966-10-5 | C9H12O |  | |

| 30 | alpha-bisabolol | 0.27 ± 0.03 | 072691-24-8 | C15H26O |  | |

| Aldehydes | 7 | undecanal | 0.43 ± 0.07 | 000112-44-7 | C11H22O |  |

| 11 | dodecanal | 0.26 ± 0.05 | 000112-54-9 | C12H24O |  | |

| 38 | (z)-9-octadecenal | 0.28 ± 0.04 | 002423-10-1 | C18H34O |  | |

| Esters | 1 | ethyl acetate | 1.94 ± 0.14 | 000141-78-6 | C4H8O2 |  |

| 2 | 3-methyl-butanoic acid ethyl ester | 0.38 ± 0.04 | 000108-64-5 | C7H14O2 |  | |

| 6 | benzeneacetic acid ethyl ester | 1.64 ± 0.05 | 000101-97-3 | C10H12O2 |  | |

| Alkenes | 3 | styrene | 2.35 ± 0.05 | 000100-42-5 | C8H8 |  |

| 12 | (E)-9-octadecene | 0.35 ± 0.06 | 007206-25-9 | C18H36 |  | |

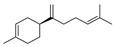

| 13 | gamma-elemene | 4.75 ± 0.08 | 030824-67-0 | C15H24 |  | |

| 14 | 1,2,4,5-tetramethyl-benzene | 1.08 ± 0.16 | 000095-93-2 | C10H14 |  | |

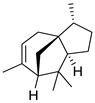

| 15 | [3R-(3α,3aβ,7β,8aα)]-2,3,4,7,8,8a-hexahydro-3,6,8,8-tetramethyl-1H-3a,7-methanoazulene | 4.34 ± 0.12 | 000469-61-4 | C15H24 |  | |

| 16 | 1-(1,5-dimethyl-4-hexenyl)-4-methyl-benzene | 0.69 ± 0.06 | 000644-30-4 | C15H22 |  | |

| 17 | 2,6-dimethyl-6-(4-methyl-3-pentenyl)-bicyclo[3.1.1]hept-2-ene | 0.96 ± 0.07 | 017699-05-7 | C15H24 |  | |

| 18 | 3,7,7-trimethyl-11-methylenespiro[5.5]undec-2-ene | 8.31 ± 0.07 | 018431-82-8 | C15H24 |  | |

| 19 | (R)-1-methyl-4-(1,2,2-trimethylcyclopentyl)-benzene | 0.31 ± 0.05 | 016982-00-6 | C15H22 |  | |

| 20 | (S)-1-methyl-4-(5-methyl-1-methylene-4-hexenyl)-cyclohexene | 3.52 ± 0.07 | 000495-61-4 | C15H24 |  | |

| 21 | (R)-2,4a,5,6,7,8-hexahydro-3,5,5,9-tetramethyl-1H-benzocycloheptene | 0.41 ± 0.05 | 001461-03-6 | C15H24 |  | |

| 22 | [S-(R*,S*)]-3-(1,5-dimethyl-4-hexenyl)-6-methylene-cyclohexene | 1.06 ± 0.12 | 020307-83-9 | C15H24 |  | |

| 24 | cis-alpha-bisabolene | 0.97 ± 0.12 | 029837-07-8 | C15H24 |  | |

| 26 | camphene | 0.62 ± 0.06 | 000079-92-5 | C10H16 |  | |

| 27 | himachala-2,4-diene | 1.25 ± 0.05 | 060909-27-5 | C15H24 |  | |

| 29 | [1R-(1α,7β,8aα)]-1,2,3,5,6,7,8,8a-octahydro-1,8a-dimethyl-7-(1-methylethenyl)-naphthalene | 0.31 ± 0.04 | 004630-07-3 | C15H24 |  | |

| Phenols | 33 | 2,3,6-trimethyl-phenol | 0.25 ± 0.05 | 002416-94-6 | C9H12O |  |

| Others | 5 | 1,3-dimethoxy-benzene | 0.32 ± 0.04 | 000151-10-0 | C8H10O2 |  |

| 8 | 1-isopropyl-3-tert-butylbenzene | 9.42 ± 0.12 | 020033-12-9 | C13H20 |  | |

| 9 | cis-octahydro-2-oxabicyclo[4.4.0]decane-2H-1-benzopyran | 0.44 ± 0.04 | 060416-19-5 | C9H16O |  | |

| 10 | 5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-2-naphthalenamine | 3.20 ± 0.21 | 002217-43-8 | C10H13N |  |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yin, G.; Pennerman, K.K.; Chen, W.; Wu, T.; Bennett, J.W. Characterization of Volatile Organic Compounds Released by Penicillium expansum and Penicillium polonicum. Metabolites 2026, 16, 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010037

Yin G, Pennerman KK, Chen W, Wu T, Bennett JW. Characterization of Volatile Organic Compounds Released by Penicillium expansum and Penicillium polonicum. Metabolites. 2026; 16(1):37. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010037

Chicago/Turabian StyleYin, Guohua, Kayla K. Pennerman, Wenpin Chen, Tao Wu, and Joan W. Bennett. 2026. "Characterization of Volatile Organic Compounds Released by Penicillium expansum and Penicillium polonicum" Metabolites 16, no. 1: 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010037

APA StyleYin, G., Pennerman, K. K., Chen, W., Wu, T., & Bennett, J. W. (2026). Characterization of Volatile Organic Compounds Released by Penicillium expansum and Penicillium polonicum. Metabolites, 16(1), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010037