Associations Between Systemic Inflammatory Markers, Metabolic Dysfunction, and Liver Fibrosis Scores in Patients with MASLD

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Framework and Ethics Protocol

2.2. Participant Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Clinical and Anthropometric Evaluation

Medication and Comorbidity Controls

2.4. Laboratory Investigations

2.4.1. Blood Sample Collection and Processing

2.4.2. Routine Biochemical Parameters

2.4.3. Inflammatory Marker Quantification

2.5. Hepatic Steatosis and Fibrosis Assessment

2.5.1. Abdominal Ultrasonography

2.5.2. Transient Elastography (FibroScan®)

2.6. Non-Invasive Fibrosis Score Calculations: Multiple Validated Non-Invasive Scoring Systems Were Calculated for Each Patient

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

3.2. Assessment of MASLD Severity Using Non-Invasive Parameters

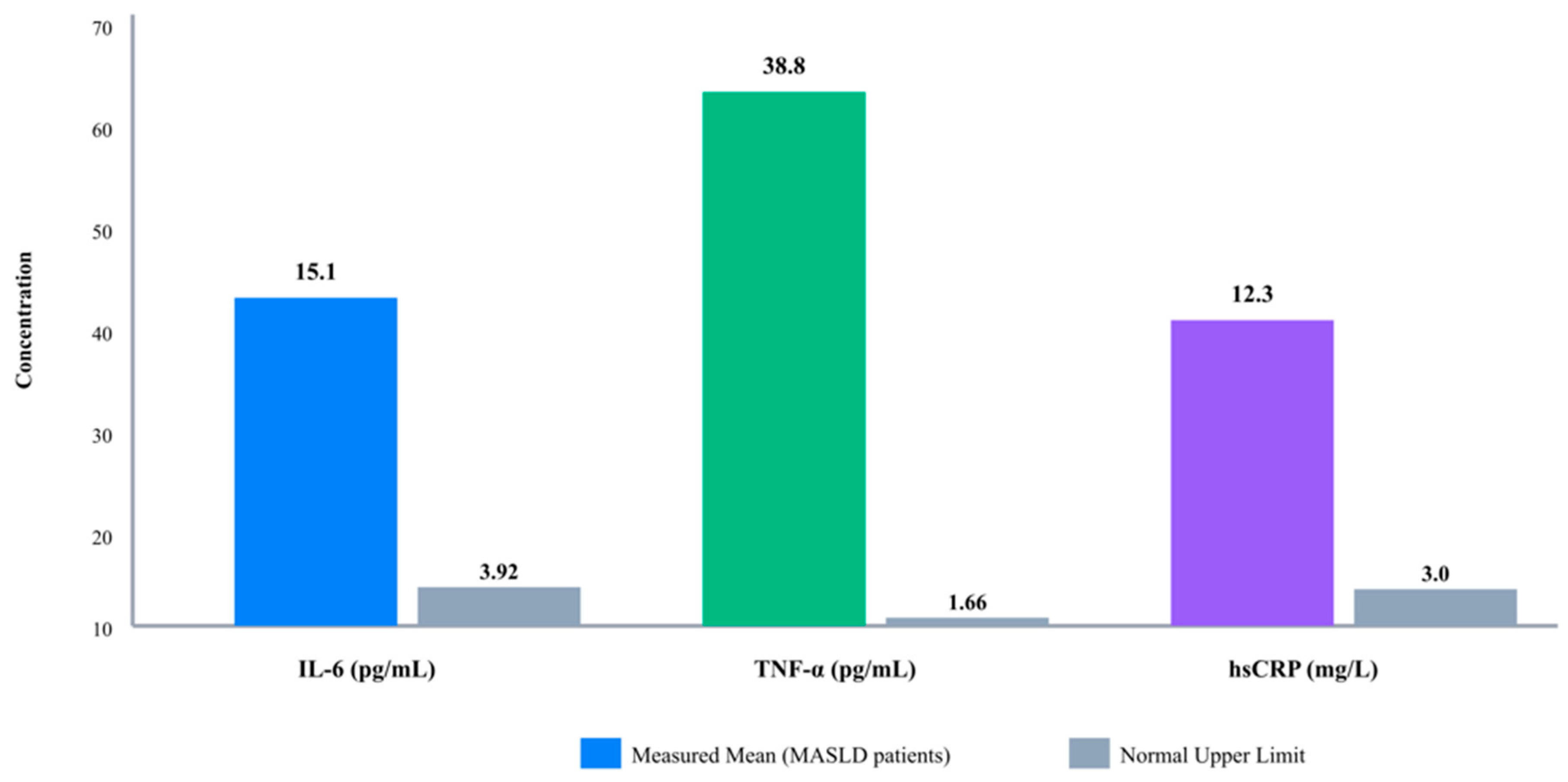

3.3. Inflammatory Marker Profiles in MASLD Patients

3.4. Relationship Between IL-6 and Hepatic Fibrosis Severity

3.5. Relationship Between hsCRP and Hepatic Fibrosis Severity

3.6. Relationship Between TNF-α and Hepatic Fibrosis Severity

3.7. Comprehensive Summary of Inflammatory Markers and Fibrosis Severity

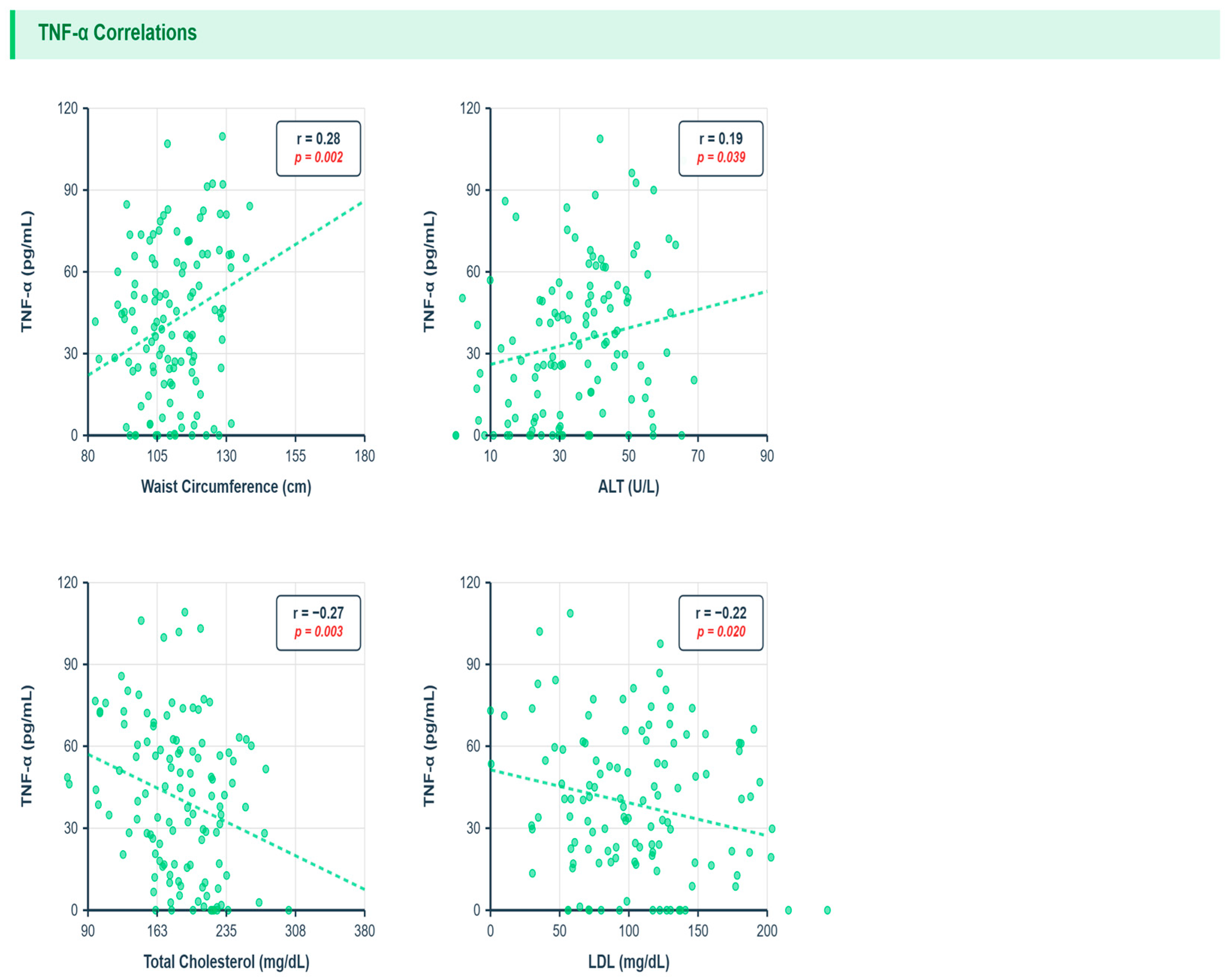

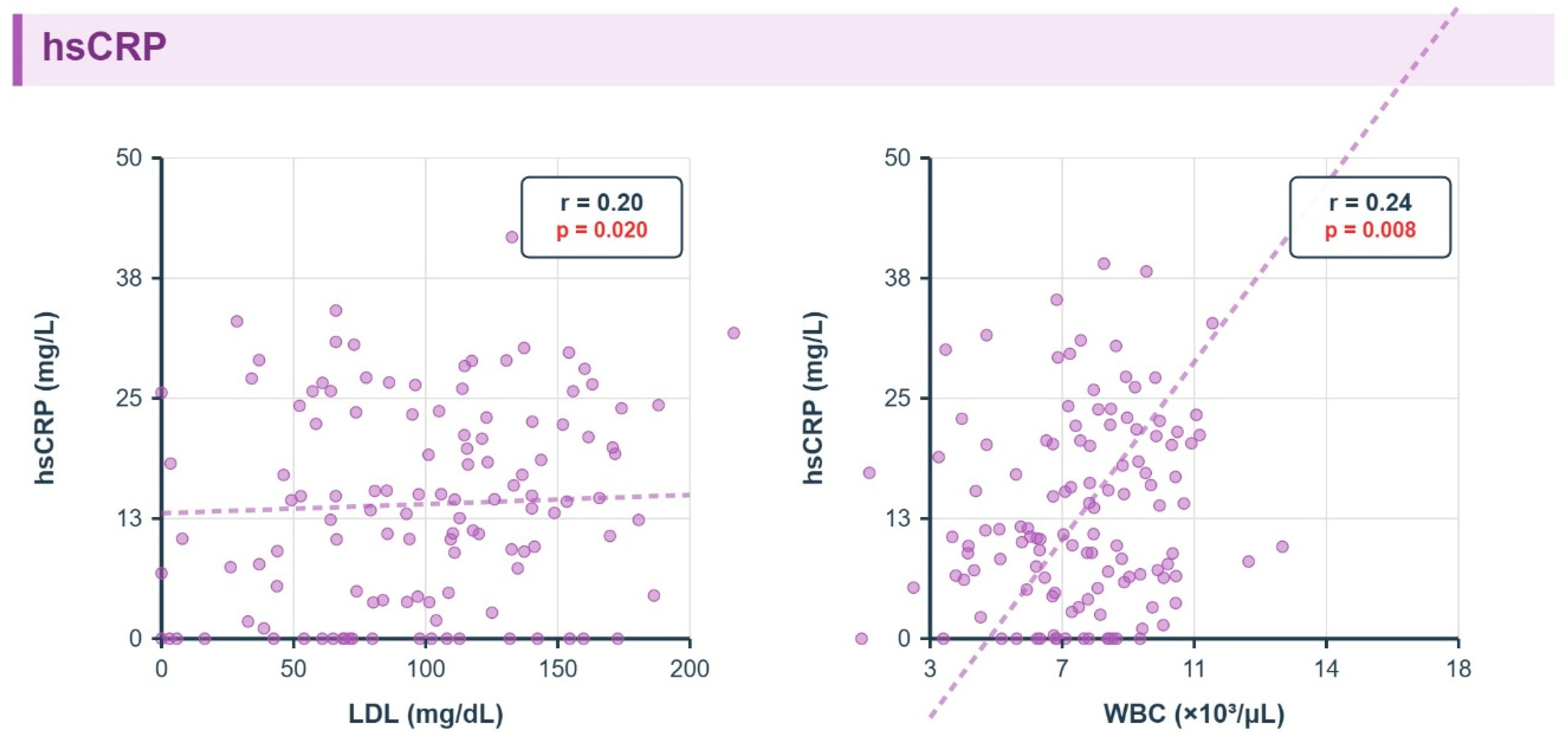

3.8. Correlations Between Inflammatory Markers and Metabolic Parameters

3.9. Metabolic and Multivariate Associations

- TNF-α: waist circumference r = 0.28 q = 0.01, ALT r = 0.19 q = 0.04; inverse total cholesterol r = −0.27 q = 0.03, LDL r = −0.22 q = 0.04, triglycerides r = −0.13 q = 0.045 (corrected).

- hsCRP: LDL r = 0.20 q = 0.02, WBC r = 0.24 q = 0.01.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Younossi, Z.M.; Kalligeros, M.; Henry, L. Epidemiology of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2024, 31, S32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youssif, M.; Eid, R.A.; Rabea, H.; Madney, Y.M.; Khaled, A.; Orayj, K.; Attia, D.; Wahsh, E.A. Evaluation of the Potential Benefits of Trimetazidine in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eid, R.A.; Soliman, A.S.; Attia, D.; Nabil, T.; Abd Elmaogod, E.A. IDDF2024-ABS-0333 Prevalence of dysplasia in the liver tissues of non-cirrhotic patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Clin. Hepatol. 2024, 73, A264–A265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, R.A.; Attia, D.; Soliman, A.S.; Abd Elmaogod, E.A.; AbdelSalam, E.M.; Rashad, A.M.; Sayed, A.S.A.; Nabil, T.M. Impact of sleeve gastrectomy on the course of metabolic associated fatty liver disease. Indian J. Gastroenterol. 2025, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.A.; Friedman, S.L. Inflammatory and fibrotic mechanisms in NAFLD—Implications for new treatment strategies. J. Intern. Med. 2022, 291, 11–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Pan, X.; Luo, J.; Xiao, X.; Li, J.; Bestman, P.L.; Luo, M. Association of inflammatory cytokines with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 880298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tylutka, A.; Walas, Ł.; Zembron-Lacny, A. Level of IL-6, TNF, and IL-1β and age-related diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1330386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, Y.; Xie, F.; Fan, J. Associations between composite systemic inflammation indicators (CAR, CLR, SII, AISI, SIRI, and CALLY) and metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD): Evidence from a two-stage study in China. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1702567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, A.; Rockey, D.C. The utility of liver biopsy in 2020. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2020, 36, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, R.A.; Abdel Fattah, A.M.; Haseeb, A.F.; Hamed, A.M.; Shaker, M.A. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation for stage B1 of modified Bolondi’s subclassification for intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Egypt. Liver J. 2024, 14, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabry, R.M.; Hamad, O.; Khalil, H.E.; Mohammed, S.I.; Eid, R.A.; Hosny, H. The role of multifocal visual evoked potential in detection of minimal hepatic encephalopathy in patients with compensated liver cirrhosis. BMC Neurol. 2025, 25, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Vali, Y.; Boursier, J.; Spijker, R.; Anstee, Q.M.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Zafarmand, M.H. Prognostic accuracy of FIB-4, NAFLD fibrosis score and APRI for NAFLD-related events: A systematic review. Liver Int. 2021, 41, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichez, J.; Mouillot, T.; Vonghia, L.; Costentin, C.; Moreau, C.; Roux, M.; Delamarre, A.; Francque, S.; Zheng, M.H.; Boursier, J. Non-invasive tests for fibrotic MASH for reducing screen failure in therapeutic trials. JHEP Rep. 2025, 7, 101351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Shen, S.; Jiang, N.; Feng, Y.; Yang, G.; Lu, D. Associations between systemic inflammatory biomarkers and metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease: A cross-sectional study of NHANES 2017–2020. BMC Gastroenterol. 2025, 25, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelhameed, F.; Kite, C.; Lagojda, L.; Dallaway, A.; Chatha, K.K.; Chaggar, S.S.; Dalamaga, M.; Kassi, E.; Kyrou, I.; Randeva, H.S. Non-invasive scores and serum biomarkers for fatty liver in the era of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD): A comprehensive review from NAFLD to MAFLD and MASLD. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2024, 13, 510–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL); European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD); European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO). EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). Obes. Facts 2024, 17, 374–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelkader, N.A.; Fouad, Y.; Shamkh, M.A.; Elnabawy, O.M.; Eid, R.A.; Attia, D.; Abdeltawab, D.; Khalil, N.O.; Abdallah, M.; Abdelhalim, S.M. Prevalence of spontaneous fungal peritonitis in Egyptian cirrhotic patients with ascites. Egypt. Liver J. 2025, 15, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaira, L.; Armandi, A.; Rosso, C.; Caviglia, G.P.; Marano, M.; Amato, F.; Gjini, K.; Guariglia, M.; Dileo, E.; Goitre, I.; et al. The use of Controlled Attenuation Parameter for the assessment of treatment response in patients with Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease undergoing a lifestyle intervention program. Dig. Liver Dis. 2025, 57, S44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkholy, M.M.; Eid, R.A. Quantitative motor unit potential analysis and nerve conduction studies for detection of subclinical peripheral nerve dysfunction in patients with compensated liver cirrhosis. Egypt. J. Neurol. Psychiatry Neurosurg. 2021, 57, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Ito, T.; Arai, T.; Atsukawa, M.; Kawanaka, M.; Toyoda, H.; Honda, T.; Yu, M.L.; Yoon, E.L.; Jun, D.W.; et al. Modified FIB-4 index in type 2 diabetes mellitus with steatosis: A non-linear predictive model for advanced hepatic fibrosis. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bołdys, A.; Borówka, M.; Bułdak, Ł.; Okopień, B. Impact of Short-Term Liraglutide Therapy on Non-Invasive Markers of Liver Fibrosis in Patients with MASLD. Metabolites 2025, 15, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S.; Iino, C.; Chinda, D.; Sasada, T.; Tateda, T.; Kaizuka, M.; Nomiya, H.; Igarashi, G.; Sawada, K.; Mikami, T.; et al. Effect of Liver Fibrosis on Oral and Gut Microbiota in the Japanese General Population Determined by Evaluating the FibroScan–Aspartate Aminotransferase Score. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zisis, M.; Chondrogianni, M.E.; Androutsakos, T.; Rantos, I.; Oikonomou, E.; Chatzigeorgiou, A.; Kassi, E. Linking cardiovascular disease and metabolic Dysfunction-Associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD): The role of cardiometabolic drugs in MASLD treatment. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Lv, J.; Chen, X.; Shi, Y.; Chao, G.; Zhang, S. From gut to liver: Exploring the crosstalk between gut-liver axis and oxidative stress in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Ann. Hepatol. 2025, 30, 101777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vachliotis, I.D.; Polyzos, S.A. The Intriguing Roles of Cytokines in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: A Narrative Review. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2025, 14, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Prakash, S.; Chhabra, S.; Singla, V.; Madan, K.; Gupta, S.D.; Panda, S.K.; Khanal, S.; Acharya, S.K. Association of pro-inflammatory cytokines, adipokines & oxidative stress with insulin resistance & non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Indian J. Med. Res. 2012, 136, 229–236. [Google Scholar]

- Mogahed, E.A.; Soliman, H.M.; Morgan, D.S.; Elaal, H.M.; Khattab, R.A.; Eid, R.A.; Hodeib, M. Prevalence of autoimmune thyroiditis among children with autoimmune hepatitis. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2024, 50, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farag, M.H.; Shaaban, M.H.; Abdelkader, H.; Al Fatease, A.; Elgendy, S.O.; Okasha, H.H. Predictors of Complications in Radiofrequency Ablation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Comprehensive Analysis of 1000 Cases. Medicina 2025, 61, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González Hernández, M.A.; Verschuren, L.; Caspers, M.P.; Morrison, M.C.; Venhorst, J.; van den Berg, J.T.; Coornaert, B.; Hanemaaijer, R.; van Westen, G.J. Identifying patient subgroups in MASLD and MASH-associated fibrosis: Molecular profiles and implications for drug development. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, K.; Asrani, S.K.; Fiel, M.I.; Levine, D.; Leung, D.H.; Duarte-Rojo, A.; Dranoff, J.A.; Nayfeh, T.; Hasan, B.; Taddei, T.H.; et al. Accuracy of blood-based biomarkers for staging liver fibrosis in chronic liver disease: A systematic review supporting the AASLD Practice Guideline. Hepatology 2025, 81, 358–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilar-Gomez, E.; Yates, K.P.; Kleiner, D.E.; Behling, C.; Cummings, O.W.; Wilson, L.A.; Liang, T.; Jarasvaraparn, C.; Loomba, R.; Schwimmer, J.B.; et al. Genetic and non-genetic drivers of histological progression and regression in MASLD. J. Hepatol. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raverdy, V.; Tavaglione, F.; Chatelain, E.; Lassailly, G.; De Vincentis, A.; Vespasiani-Gentilucci, U.; Qadri, S.F.; Caiazzo, R.; Verkindt, H.; Saponaro, C.; et al. Data-driven cluster analysis identifies distinct types of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 3624–3633. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, G.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Li, M.; Li, H.; Chen, C. High levels of serum hypersensitive C-reactive protein are associated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in non-obese people: A cross-sectional study. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2024, 29, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Porwal, Y.C.; Dev, N.; Kumar, P.; Chakravarthy, S.; Kumawat, A. Association of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in Asian Indians: A cross-sectional study. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2020, 9, 390–394. [Google Scholar]

- Verschuren, L.; Mak, A.L.; van Koppen, A.; Özsezen, S.; Difrancesco, S.; Caspers, M.P.; Snabel, J.; van der Meer, D.; van Dijk, A.M.; Rashu, E.B.; et al. Development of a novel non-invasive biomarker panel for hepatic fibrosis in MASLD. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes-Turrubiarte, G.; González-Chávez, A.; Pérez-Tamayo, R.; Salazar-Vázquez, B.Y.; Hernández, V.S.; Garibay-Nieto, N.; Fragoso, J.M.; Escobedo, G. Severity of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with high systemic levels of tumor necrosis factor alpha and low serum interleukin 10 in morbidly obese patients. Clin. Exp. Med. 2016, 16, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musso, G.; Gambino, R.; Durazzo, M.; Biroli, G.; Carello, M.; Faga, E.; Pacini, G.; De Michieli, F.; Rabbione, L.; Premoli, A.; et al. Adipokines in NASH: Postprandial lipid metabolism as a link between adiponectin and liver disease. Hepatology 2005, 42, 1175–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abiru, S.; Migita, K.; Maeda, Y.; Daikoku, M.; Ito, M.; Ohata, K.; Nagaoka, S.; Matsumoto, T.; Takii, Y.; Kusumoto, K.; et al. Serum cytokine and soluble cytokine receptor levels in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Liver Int. 2006, 26, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, T.; Yoshio, S.; Kakazu, E.; Kanto, T. Active role of the immune system in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2024, 12, goae089. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Chen, Y.; Qian, S.; van Der Merwe, S.; Dhar, D.; Brenner, D.A.; Tacke, F. Immunopathogenic mechanisms and immunoregulatory therapies in MASLD. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2025, 22, 1159–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandireddy, R.; Sakthivel, S.; Gupta, P.; Behari, J.; Tripathi, M.; Singh, B.K. Systemic impacts of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) on heart, muscle, and kidney related diseases. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 12, 1433857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.S.; Park, J.Y.; Yu, R. Relationship of obesity and visceral adiposity with serum concentrations of CRP, TNF-α and IL-6. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2005, 69, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ackermann, D.; Jones, J.; Barona, J.; Calle, M.C.; Kim, J.E.; LaPia, B.; Volek, J.S.; McIntosh, M.; Kalynych, C.; Najm, W.; et al. Waist circumference is positively correlated with markers of inflammation and negatively with adiponectin in women with metabolic syndrome. Nutr. Res. 2011, 31, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valmorbida, A.; Longo, G.Z.; Nascimento, G.M.; de Oliveira, L.L.; de Moraes Trindade, E.B. Association between cytokine levels and anthropometric measurements: A population-based study. Br. J. Nutr. 2023, 129, 1119–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradham, C.A.; Plümpe, J.; Manns, M.P.; Brenner, D.A.; Trautwein, C.I. TNF-induced liver injury. Am. J. Physiol.-Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 1998, 275, G387–G392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vachliotis, I.D.; Polyzos, S.A. The role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in the pathogenesis and treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2023, 12, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, K.; Chung, H.; Softic, S.; Moreno-Fernandez, M.E.; Divanovic, S. The bidirectional immune crosstalk in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Cell Metab. 2023, 35, 1852–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, G.R.; Carpentier, A.C.; Wang, D. MASH: The nexus of metabolism, inflammation, and fibrosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2025, 135, e186420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoro, E.U. TNFα-induced LDL cholesterol accumulation involve elevated LDLR cell surface levels and SR-B1 downregulation in human arterial endothelial cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popa, C.; Netea, M.G.; Van Riel, P.L.; Van Der Meer, J.W.; Stalenhoef, A.F. The role of TNF-α in chronic inflammatory conditions, intermediary metabolism, and cardiovascular risk. J. Lipid Res. 2007, 48, 751–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, X.; Liang, Y.; Chang, H.; Cai, T.; Feng, B.; Gordon, K.; Zhu, Y.; Shi, H.; He, Y.; Xie, L. Targeting proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9): From bench to bedside. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegeye, M.M.; Nakka, S.S.; Andersson, J.S.; Söderberg, S.; Ljungberg, L.U.; Kumawat, A.K.; Sirsjö, A. Soluble LDL-receptor is induced by TNF-α and inhibits hepatocytic clearance of LDL-cholesterol. J. Mol. Med. 2023, 101, 1615–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, I.; Choi, N.; Shin, J.H.; Lee, S.; Nam, B.; Kim, T.H. Impact of anti-tumor necrosis factor treatment on lipid profiles in Korean patients with ankylosing spondylitis. J. Rheum. Dis. 2024, 31, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nafari, A.; Mohammadifard, N.; Haghighatdoost, F.; Nasirian, S.; Najafian, J.; Sadeghi, M.; Roohafza, H.; Sarrafzadegan, N. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol association with incident of cardiovascular events: Isfahan cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2022, 22, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bafei, S.E.; Zhao, X.; Chen, C.; Sun, J.; Zhuang, Q.; Lu, X.; Chen, Y.; Gu, X.; Liu, F.; Mu, J.; et al. Interactive effect of increased high sensitive C-reactive protein and dyslipidemia on cardiovascular diseases: A 12-year prospective cohort study. Lipids Health Dis. 2023, 22, 95. [Google Scholar]

- Ridker, P.M. Targeting residual inflammatory risk: The next frontier for atherosclerosis treatment and prevention. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2023, 153, 107238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M.; Moorthy, M.V.; Cook, N.R.; Rifai, N.; Lee, I.M.; Buring, J.E. Inflammation, cholesterol, lipoprotein (a) and 30-year cardiovascular outcomes in women. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa-Fotea, N.M.; Ferdoschi, C.E.; Micheu, M.M. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of inflammation in atherosclerosis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1200341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, A.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Gluckman, T.J.; Feldman, D.I.; Kohli, P. High-sensitivity C-reactive Protein in Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease: To Measure or Not to Measure? US Cardiol. Rev. 2025, 19, e06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yassin, A.; Eid, R.A.; Mohammad, M.F.; Elgendy, M.O.; Mohammed, Z.; Abdelrahim, M.E.; Abdel Hamied, A.M.; Binsuwaidan, R.; Saleh, A.; Hussein, M.; et al. Microbial Multidrug-Resistant Organism (MDRO) Mapping of Intensive Care Unit Infections. Medicina 2025, 61, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsabaawy, M.; Torkey, M.; Magdy, M.; Naguib, M. Stratified cardiovascular risk in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD): Impact of varying metabolic risk factor burden. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2025, 30, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakal, T.C.; Xiao, F.; Bhusal, C.K.; Sabapathy, P.C.; Segal, R.; Chen, J.; Bai, X. Lipids dysregulation in diseases: Core concepts, targets and treatment strategies. Lipids Health Dis. 2025, 24, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Gao, X.; Niu, W.; Yin, J.; He, K. Targeting Metabolism: Innovative Therapies for MASLD Unveiled. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Targher, G.; Byrne, C.D.; Tilg, H. MASLD: A systemic metabolic disorder with cardiovascular and malignant complications. Gut 2024, 73, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, C.D.; Armandi, A.; Pellegrinelli, V.; Vidal-Puig, A.; Bugianesi, E. Μetabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: A condition of heterogeneous metabolic risk factors, mechanisms and comorbidities requiring holistic treatment. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2025, 22, 314–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zibaeenejad, F.; Mohammadi, S.S.; Sayadi, M.; Safari, F.; Zibaeenezhad, M.J. Ten-year atherosclerosis cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk score and its components among an Iranian population: A cohort-based cross-sectional study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2022, 22, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adinolfi, L.E.; Marrone, A.; Rinaldi, L.; Nevola, R.; Izzi, A.; Sasso, F.C. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD): A systemic disease with a variable natural history and challenging management. Explor. Med. 2025, 6, 1001281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.W.; Lu, L.G. Current Status of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists in Metabolic Dysfunction-associated Steatotic Liver Disease: A Clinical Perspective. J. Clin. Transl. Hepatol. 2024, 13, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanyal, A.J.; Bedossa, P.; Fraessdorf, M.; Neff, G.W.; Lawitz, E.; Bugianesi, E.; Anstee, Q.M.; Hussain, S.A.; Newsome, P.N.; Ratziu, V.; et al. A phase 2 randomized trial of survodutide in MASH and fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, L.; Wang, G.; Zhuang, Y.; Luo, L.; Yan, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Xie, C.; He, Q.; Peng, Y.; et al. Safety and efficacy of GLP-1/FGF21 dual agonist HEC88473 in MASLD and T2DM: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J. Hepatol. 2025, 82, 967–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Number (n = 120) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Median (Range) | |

| Age (years) | 47.3 ± 7.9 | 47.5(29–66) |

| Sex | No. | % |

| Male | 52 | 43.3% |

| Female | 68 | 56.7% |

| Diabetes mellitus | ||

| No | 84 | 70% |

| Yes | 36 | 30% |

| Anthropometric measure | Mean ± SD | Median (Range) |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 111.4 ± 11.9 | 110 (84–176) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 35.2 ± 7.3 | 34 (24.4–61.8) |

| Laboratory investigations | Mean ± SD | Median (Range) |

| FBS | 120.02 ± 47.9 | 105 (60–372) |

| HOMA-IR | 2.2 ± 0.98 | 1.9 (0.86–6.4) |

| ALT | 33.1 ± 14.1 | 28 (16–85) |

| AST | 33.5 ± 11.2 | 31 (15–75) |

| GGT | 48.9 ± 38.9 | 38 (14–251) |

| Albumin | 4.02 ± 0.33 | 4 (3–4.7) |

| Total cholesterol | 191.1 ± 46.3 | 191 (99–376) |

| Triglyceride | 196.3 ± 101.2 | 172.5 (66–797) |

| LDL | 103.6 ± 47.7 | 101 (3.2–378) |

| HDL | 47.6 ± 9.9 | 47.5 (26–85) |

| Hemoglobin | 13.3 ± 1.5 | 13.3 (10–16.5) |

| PLT count | 271.4 ± 59.5 | 266.5 (151–422) |

| WBCs | 6.9 ± 2.3 | 6.1 (3.7–16.7) |

| Variables | MASLD Severity (n = 120) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Median (Range) | |||||

| CAP score | 325.7 ± 54.2 | 334 (100–400) | ||||

| TE score | 7.5 ± 4.3 | 6.1 (2.1–28) | ||||

| FAST score | 0.50 ± 1.6 | 0.33 (0.04–18) | ||||

| APRI score | 0.33 ± 0.15 | 0.30 (0.1–1.1) | ||||

| Fib 4 score | 1.09 ± 0.54 | 1.01 (0.43–3.96) | ||||

| NAFLD F score | −1.17 ± 1.24 | −1.17 (−3.86/2.15) | ||||

| ASCV score | 3.8 ± 5.02 | 2 (0.3–35.3) | ||||

| Severity grades | Mild | Moderate | Severe | |||

| TE score | 80 (66.7%) | 28 (23.3%) | 12 (10%) | |||

| FAST score | 119 (99.2%) | 1 (0.8%) | ---- | |||

| Fib 4 score | 86 (71.7%) | 31 (25.8%) | 3 (2.5%) | |||

| Low | Intermediate | High | ||||

| APRI score | 114 (95%) | 6 (5%) | ---- | |||

| NAFLD F score | 46 (38.3%) | 39 (32.5%) | 35 (29.2%) | |||

| S0 | S1 | S2 | S3 | |||

| CAP score | 8 (6.7%) | 4 (3.3%) | 8 (6.7%) | 100 (83.3%) | ||

| Low | Borderline | Intermediate | High | |||

| ASCV score | 96 (80%) | 11 (9.2%) | 10 (8.3%) | 3 (2.5%) | ||

| Marker | Parameter | r | p | q (FDR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNF-α | Waist (cm) | 0.28 | 0.002 | 0.01 |

| TNF-α | Triglycerides (mg/dL) | −0.13 | 0.015 | 0.045 |

| hsCRP | LDL (mg/dL) | 0.20 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| hsCRP | WBC (109/L) | 0.24 | 0.008 | 0.01 |

| Model | Dependent | Predictor | β | p | Adjusted R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | TNF-α (pg/mL) | Waist (cm) | 0.28 | <0.01 | 0.32 |

| Diabetes (yes) | 0.15 | 0.08 | |||

| TE (kPa) | 0.07 | 0.32 | |||

| 2 | hsCRP (mg/L) | LDL (mg/dL) | 0.18 | 0.03 | 0.25 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.12 | 0.15 | |||

| FIB-4 | 0.05 | 0.48 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Eid, R.A.; Hamed, A.M.; Elgendy, S.O.; Orayj, K.M.; Ibrahim, A.R.N.; Hamied, A.M.A.; Wahsh, E.A.; Youssif, M.; Rabea, H.; Madney, Y.M.; et al. Associations Between Systemic Inflammatory Markers, Metabolic Dysfunction, and Liver Fibrosis Scores in Patients with MASLD. Metabolites 2026, 16, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010025

Eid RA, Hamed AM, Elgendy SO, Orayj KM, Ibrahim ARN, Hamied AMA, Wahsh EA, Youssif M, Rabea H, Madney YM, et al. Associations Between Systemic Inflammatory Markers, Metabolic Dysfunction, and Liver Fibrosis Scores in Patients with MASLD. Metabolites. 2026; 16(1):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010025

Chicago/Turabian StyleEid, Ragaey Ahmad, Ahmed Moheyeldien Hamed, Sara O. Elgendy, Khalid M. Orayj, Ahmed R. N. Ibrahim, Ahmed M. Abdel Hamied, Engy A. Wahsh, Maha Youssif, Hoda Rabea, Yasmin M. Madney, and et al. 2026. "Associations Between Systemic Inflammatory Markers, Metabolic Dysfunction, and Liver Fibrosis Scores in Patients with MASLD" Metabolites 16, no. 1: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010025

APA StyleEid, R. A., Hamed, A. M., Elgendy, S. O., Orayj, K. M., Ibrahim, A. R. N., Hamied, A. M. A., Wahsh, E. A., Youssif, M., Rabea, H., Madney, Y. M., Attia, D., & Nafady, S. (2026). Associations Between Systemic Inflammatory Markers, Metabolic Dysfunction, and Liver Fibrosis Scores in Patients with MASLD. Metabolites, 16(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010025