Abstract

Background: Lonicerae japonicae flos (LJF), a traditional food and medicine with a history spanning thousands of years, undergoes drying as a critical processing step in modern applications after regular processing. While the by-products of this process are typically discarded as waste, the potential value of LJF condensate water (JYHC) remains largely unexplored. To address this gap and investigate its potential utilization, this study conducted widely targeted metabolome and volatile metabolomics profiling analyses of ‘JYHC’. Methods: This study analyzed the differential metabolites of ‘JYHC’ and dried Lonicerae japonicae flos (JYHG) based on widely targeted metabolomics using UPLC-MS/MS. Additionally, the metabolic differences between fresh Lonicerae japonicae flos (JYHX) and ‘JYHC’ based on GC-MS volatile metabolomics were comprehensively analyzed. Results: A total of 1651 secondary metabolites and 909 volatile metabolites were identified in this study. Among these, flavonoids and terpenoids were the predominant secondary metabolites, while esters and terpenoids dominated the volatile fraction. Further comparison of the ‘JYHC’ and ‘JYHG’ groups revealed that 58 differential metabolites with potential biological activities were significantly up-regulated, with the types being terpenoids, phenolic acids, and alkaloids, which included nootkatone, mandelic acid, sochlorogenic acid B, allantoin, etc. Notably, a total of 186 novel compounds were detected in ‘JYHC’ that had not been previously reported in LJF such as isoborneol, hinokitiol, agarospirol, 5-hydroxymethylfurfural, α-cadinol, etc. Conclusions: This study’s findings highlight the metabolic diversity of ‘JYHC’, offering new theoretical insights into the study of LJF and its by-products. Moreover, this research provides valuable evidence supporting the potential utilization of drying by-products from LJF processing, paving the way for further exploration of their pharmaceutical and industrial applications.

1. Introduction

Lonicerae japonicae flos (LJF), which originates from the dried buds of Lonicera japonica Thunb., is a member of the Caprifoliaceae family and is native to East Asia, including China, Korea, and Japan. This plant is sun-preferring and cold-hardy, and is now widely distributed across temperate to subtropical regions. Lonicera japonica Thunb. is a semi-evergreen climber; its branchlets, petioles, and peduncles are covered with yellowish-brown stiff hairs or soft pubescence. Its leaves are papery and predominantly ovate or lanceolate in shape. Its fragrant flowers are paired and form axillary structures at branchlet apices. LJF has been extensively utilized in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) for thousands of years [1,2]. In China, it is used as healthy food, as well as in cosmetics and soft drinks, due to its pleasant fragrance and high safety profile [3]. Recent research has indicated that LJF is composed of essential oils, organic acids, flavonoids, and triterpenoids, which demonstrate various effects such as antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antiviral, and immune-regulatory properties. Its clinical applications are widely recognized [4,5,6,7].

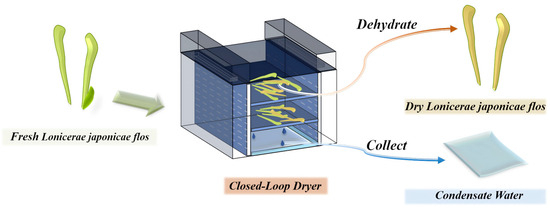

Drying is considered a crucial step in the processing of LJF (Figure 1). Drying effectively extends the shelf life of LJF and improves the stability and concentration of its active ingredients. However, its aromatic components are often lost or chemically transformed during the drying process [8,9]. At the same time, condensate water (JYHC) is usually generated. It is still unclear whether this by-product contains bioactive compounds. It is typically discarded as waste, leading to significant environmental pollution and a substantial waste of resources.

Figure 1.

Lonicerae japonicae flos drying process flowchart.

In recent years, the valorization of food industry by-products and agricultural wastes has been the focus of research worldwide [10,11]. Efforts have been made to explore the potential applications of these by-products for energy and resource conservation [12,13,14,15]. Metabolomics has been identified as a qualitative and quantitative analysis of all metabolites from different organisms, samples, or tissues. It is widely used in biomedical, botanical, and food science research [16,17,18,19,20,21]. A widely targeted metabolomics analysis is an innovative method that merges the benefits of both non-targeted and targeted metabolomics. This technique has been extensively applied in the analysis of plant metabolites across different species, including Zingiberis rhizoma and its processed forms, as well as citronella before and after drying [22,23].

This research utilized UPLC-ESI-MS/MS-based broad-spectrum metabolome profiling to identify differential metabolites in ‘JYHC’ and ‘JYHG’ (dry Lonicerae japonicae flos). In addition, a comprehensive analysis of the metabolic differences between ‘JYHX’ (Fresh Lonicerae japonicae flos) and ‘JYHC’ was conducted using GC-MS-based volatile metabolomics. The differential metabolites were analyzed by utilizing multivariate methods for statistical analysis. The findings of this study can be used as a new theoretical reference for the study of LJF and its by-products. Meanwhile, it also provides valuable insights into the potential utilization of the by-products generated during the drying process of LJF.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

In this study, fresh Lonicerae japonicae flos (JYHX) was collected on 27 June 2024 in Dakuang Town, Laiyang City, Yantai, Shandong Province, China, and samples were annotated as JYHX (JYH-202406) by Professor Fengzhong Wang of the Institute of Food Science and Technology, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, China. The drying process of LJF was carried out at Yantai Riga Energy Saving Technology Co., Ltd. (Yantai, China), which mainly produces drying equipment; JYHC is considered a by-product of this process. The drying process used the whole fresh LJF plant (Figure 1).

2.2. Sample Preparation for Metabolite Extraction

2.2.1. Preparation of ‘JYHC’ Test Material

We removed the ‘JYHC’ sample from an −80 °C freezer, and thawed it on ice. We vortexed the sample for 30 s. Then, 18 mL of the sample was transferred into a designated centrifuge tube, which was frozen at −80 °C overnight in a refrigerator, before proceeding with vacuum freeze-drying. After freeze-drying, 300 μL of 70% methanol extract containing an internal standard (2-chlorophenylalanine, ≥98% purity, J&K Scientific, Shanghai, China) was added at a concentration ratio of 60 times. The mixture was vortexed for 15 min, and then subjected to ultrasound in an ice water bath (KQ5200E, Beijing, China) for 10 min. The solution was centrifuged at 12,000 r/min and 4 °C (5424R, Eppendorf, Shanghai, China) for 3 min. The supernatant was collected, filtered through a microporous membrane (0.22 μm), and stored in an injection bottle.

2.2.2. Preparation of ‘JYHG’ Test Material

The ‘JYHG’ sample was vacuum freeze-dried and subsequently ground into a fine powder. An amount of 50 mg of the powdered sample was weighed and added to 1200 μL of 70% methanol extract containing the internal standard. The mixture was vortexed for 15 min, and then left in a refrigerator at 20 °C for 30 min. The solution was centrifuged at 12,000 r/min and 4 °C for 3 min. The supernatant was collected, filtered through a microporous membrane (0.22 μm), and stored in an injection bottle.

2.2.3. Preparation of ‘JYHX’ Test Material

The collected ‘JYHX’ was pulverized into a fine powder using liquid nitrogen. A total of 500 mg of the powder was added to a 20 mL headspace vial containing a saturated NaCl solution (Agilent, Waltham, MA, USA) for headspace solid-phase microextraction (HS-SPME).

2.3. Secondary Metabolites Analysis by UPLC-ESI-MS/MS

An ultra-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) system equipped with a triple quadrupole-linear ion trap (QTRAP) mass analyzer was employed for the analysis of secondary metabolites. Chromatographic separation was achieved using an Agilent SB-C18 column (1.8 μm, 2.1 mm × 100 mm) at 40 °C with a flow rate of 0.35 mL/min and an injection volume of 2 μL. The mobile phases consisted of 0.1% formic acid in water (A) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (B), and the gradient program was set as follows: linear decrease from 95% A to 5% A within 0–9 min and maintained for 1 min; followed by recovery to the initial ratio (95% A) within 1.1 min and equilibration for 2.9 min. Mass detection was performed using electrospray ionization (ESI) operated in both positive and negative modes.

Mass spectrometry was performed using an electrospray ionization (ESI) source with the following parameter settings: ion source temperature of 500 °C, spray voltage of +5500 V/−4500 V (positive/negative ion mode), nebulizing gas (GSI), auxiliary gas (GSII) and curtain gas (CUR) pressures were set to 50, 60 and 25 psi, respectively. Collision-induced dissociation (CAD) was operated in high-sensitivity mode. Multi-reaction monitoring (MRM) was employed for the detection of target metabolites. The dissociation potential (DP) and collision energy (CE) were individually optimized for each transition. All MRM transitions were dynamically scheduled according to the expected retention time of each analyte to maximize detection sensitivity.

2.4. Volatile Analysis by GC-MS

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) were analyzed using an Agilent 8890 gas chromatography system coupled to a 7000D mass spectrometry (GC-MS, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Sample injection was performed in splitless mode at an inlet temperature of 250 °C. After a 5 min solvent delay, the separation was carried out on a DB-5MS capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm, 5% phenyl-polymethylsiloxane stationary phase) using helium as the carrier gas at a constant flow rate of 1.2 mL/min.

The chromatographic separation was carried out using the following temperature program: initial temperature held at 40 °C for 3.5 min, and then increased at 10 °C/min. The chromatographic separation was performed with a programmed temperature ramp: initial temperature of 40 °C for 3.5 min, ramp to 100 °C at 10 °C/min, ramp to 180 °C at 7 °C/min, and finally, ramp to 280 °C at 25 °C/min and held for 5 min. Mass spectrometric detection was conducted in electron bombardment ionization (EI) mode at 70 eV. The temperatures of the ion source, quadrupole, and transmission line were set at 230 °C, 150 °C, and 280 °C, respectively. Data acquisition was performed in selective ion monitoring (SIM) mode to enhance the detection accuracy of the target compounds.

2.5. Multivariate Statistical Analysis

To investigate the accumulation patterns of germplasm-specific metabolites, multivariate statistical analysis was applied to the metabolomic dataset. PCA and OPLS-DA were employed for metabolic profiling and pattern recognition. The distinct accumulation patterns of metabolites were visualized through heatmaps. All these analyses were performed in the Metware Cloud online platform. Differential metabolites were screened using the following criteria: FC ≥ 2 or ≤0.5, VIP ≥ 1, and t-test p-value ≤ 0.05 (MetaboAnalyst 5.0 platform).

2.6. KEGG Pathway Analysis

The KEGG pathway database was utilized to identify and show differential metabolites.

3. Results

3.1. Overview of the Metabolites in ‘JYHC’

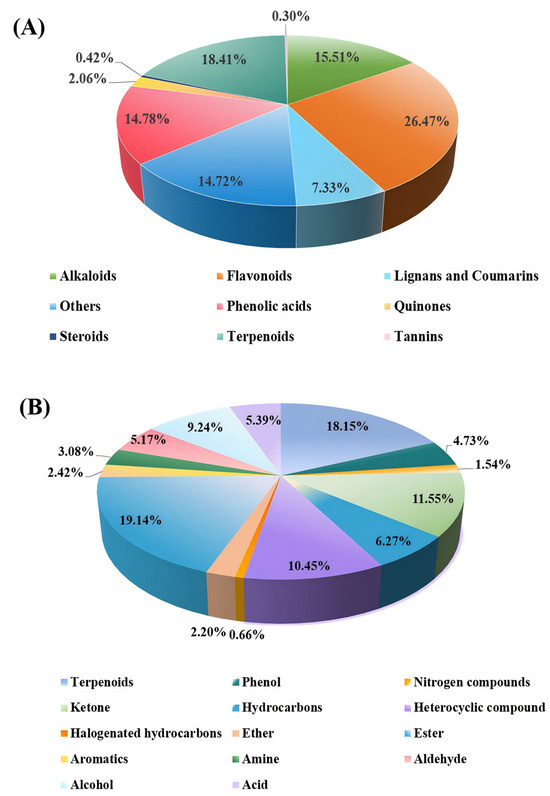

This study integrated targeted and volatile metabolomics to comprehensively profile the secondary metabolites in ‘JYHC’. A total of 1651 metabolites were detected by comprehensive targeted metabolomics and further classified into eight categories (Figure 2A). Flavonoids represented the most abundant class, with a content that is 1.4 times that of terpenoids, 1.7–1.8 times that of alkaloids/phenolic acids, and 3.6 times that of lignans/coumarins. As secondary dominant components, terpenoids have an advantage of 1.2–1.3 times over alkaloids and phenolic acids. Collectively, flavonoids and terpenoids constituted the dominant secondary metabolites in ‘JYHC’, accounting for 44.88% of the total detected metabolites.

Figure 2.

Classification of the metabolic profiles in ‘JYHC’. (A): the major secondary metabolites in ‘JYHC’ (B): volatile metabolomics in ‘JYHC’.

Volatile metabolomics profiling identified 909 metabolites, which were categorized into 14 categories (Figure 2B). It can be seen that the main volatile components in ‘JYHC’ are esters and terpenoids, collectively accounting for 37.29% of the total. Their relative abundances were approximately 1.7- and 1.6- fold higher than that of ketones, 1.8- and 1.7-fold greater than heterocyclic compounds, and 2.1- and 2.0-fold above those of alcohols, respectively. Compared to hydrocarbons, esters and terpenoids were 3.0 and 2.9 times more abundant, whereas trace components such as halogenated hydrocarbons and nitrogenous compounds exhibited substantially lower levels—only 1/26 to 1/138 of the abundance of esters.

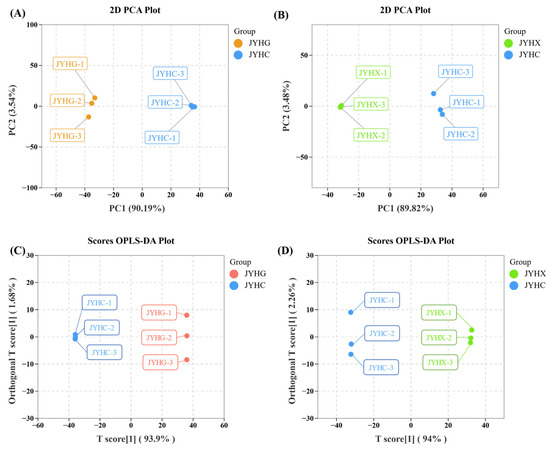

3.2. PCA and OPLS-DA Analysis

PCA analysis was performed on the secondary metabolites of ‘JYHG’ versus (vs.) ‘JYHC’ (Figure 3A) and the volatile metabolites of ‘JYHX’ vs. ‘JYHC’ (Figure 3B), respectively. The ‘JYHG’ vs. ‘JYHC’ and ‘JYHX’ vs. ‘JYHC’ groups exhibited distinct separation on both PC1 and PC2, indicating significant differences in metabolite composition between ‘JYHC’ and ‘JYHG’, as well as between ‘JYHC’ and ‘JYHX’.

Figure 3.

Principal component analysis (PCA) and score plots generated from orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) of ‘JYHC’ compared with ‘JYHX’/‘JYHG’ (A): PCA score plot in ‘JYHC’ vs. ‘JYHG’ (B): PCA score plot in ‘JYHC’ vs. ‘JYHX’ (C): OPLS-DA score plot in ‘JYHC’ vs. ‘JYHG’ (D): OPLS-DA score plot in ‘JYHC’ vs. ‘JYHX’.

Pairwise comparative OPLS-DA revealed significant metabolic differences between ‘JYHC’ and ‘JYHG’ (R2X = 0.956), as well as between ‘JYHC’ and ‘JYHX’ (R2X = 0.962). The R2Y and Q2 values of all models were close to 1 (Q2 > 0.9), demonstrating that the models had excellent stability and predictive ability. As shown in Figure 3C,D, the scoring plots clearly showed the apparent separation of ‘JYHC’ from the other two sample groups, supporting the robustness of the model and providing a solid basis for subsequent screening of differential metabolites using variable importance in projection (VIP) analysis.

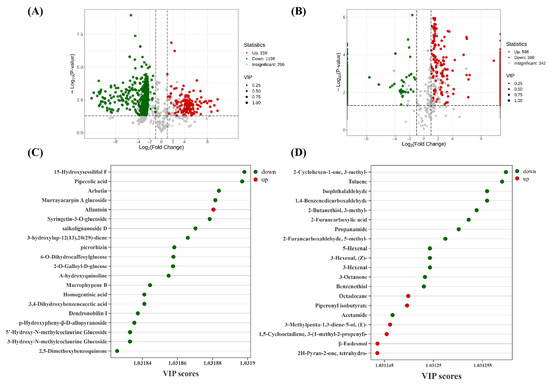

3.3. Differential Metabolites Screening

Differential metabolites were selected based on a variable importance in projection (VIP) value ≥ 1 from the OPLS-DA model, combined with univariate statistical criteria including a fold change ≥ 2 or ≤0.5 and a p-value ≤ 0.05. The results of this multi-criteria screening are visually summarized in volcano plots, which highlight metabolites meeting all these thresholds. In total, 1355 metabolites showed significant differences between ‘JYHC’ and ‘JYHG’, with 159 being upregulated and 1196 downregulated (Figure 4A); 984 volatile metabolites were significantly altered ‘JYHC’ and ‘JYHX’ (Figure 4B, 586 upregulated, 398 downregulated). Focusing on of the top 20 differential metabolites (VIP ≥ 1) between ‘JYHC’ and ‘JYHG’ groups, allantoin was the only metabolite showing significant accumulation, while the other 19 secondary metabolites showed pronounced downregulation. These downregulated metabolites primarily consisted of phenolic acids, terpenoids, and alkaloids (Figure 4C). Among the top 20 differential volatile metabolites between the ‘JYHC’ and ‘JYHX’, six metabolites (octadecane, piperonyl isobutyrate, (E)-3-methylpenta-1,3-diene-5-ol, 3-(1-methyl-2-propenyl)-1,5-cyclooctadiene, β-eudesmol, and tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-one) showed significant increases, while the remaining 14 compounds exhibited significant decreases (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

Differential metabolite results of ‘JYHC’ compared with ‘JYHX’/‘JYHG’ (A): Volcano plots showing the levels of the differential metabolites in ‘JYHC’ vs. ‘JYHG’ (B): Volcano plots showing the levels of the differential metabolites in ‘JYHC’ vs. ‘JYHX’ (C): Variable importance in the project (VIP) plot of the top 20 differential secondary metabolites identified by OPLS-DA in ‘JYHC’ vs. ‘JYHG’ (D): Variable importance in the project (VIP) plot of the top 20 differential volatile secondary metabolites identified by OPLS-DA in ‘JYHC’ vs. ‘JYHX’.

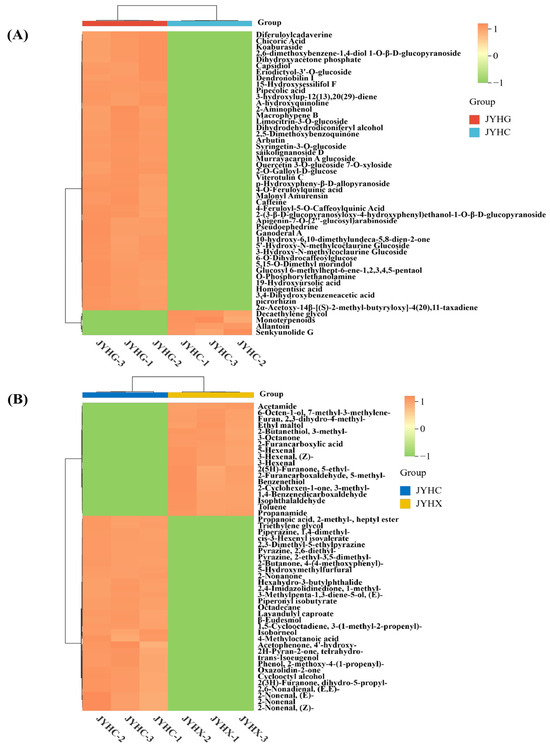

Based on the VIP values, the top 50 differential secondary metabolites and volatile differential metabolites were selected and visualized by a heat map (Figure 5A,B). Heat map analysis results indicated that there was a significant difference in the abundance of these compounds between the ‘JYHC’ vs. ‘JYHG’ and ‘JYHC’ vs. ‘JYHX’ groups.

Figure 5.

A heat map of top 50 differential metabolites. (A): Heatmap is based on relative abundance of differential metabolites in ‘JYHC’ vs. ‘JYHG’ (B): Heatmap is based on relative abundance of differential metabolites in ‘JYHC’ vs. ‘JYHX’.

The results demonstrated that the metabolite profiles of the two sample groups formed two main clusters of metabolites, indicating significant differences in the metabolites between the groups. Combined with a literature search, 58 potentially biologically active up-regulated differential metabolites were screened in the ‘JYHC’ and ‘JYHG’ group (Table 1). Terpenoids, phenolic acids, and alkaloids were identified as the predominant classes of upregulated metabolites in ‘JYHC’.

Table 1.

The information on differential metabolites in ‘JYHC’ and ‘JYHG’ groups.

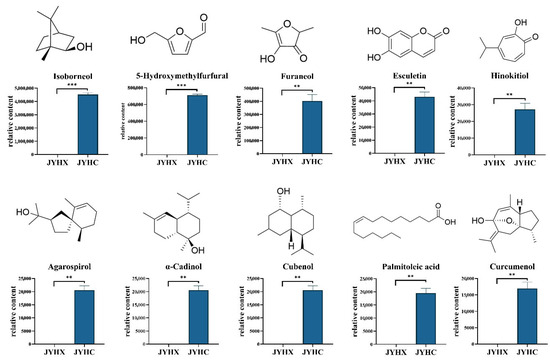

Furthermore, volatile metabolomic analysis revealed the presence of 186 different components in ‘JYHC’ that were absent in ‘JYHX’ and have not been previously reported in LJF (Table 2). These metabolites may be produced under the specific conditions or processing of ‘JYHC’ and could have potential functional significance. The newly identified volatile components are mainly terpenoids, esters, and alcohols. Among them, terpenoids account for the highest proportion (25.27%). The 10 volatile metabolites with putative bioactivities were selected for further comparison analysis (Figure 6).

Table 2.

The information on differential metabolites in ‘JYHC’ and ‘JYHX’ groups.

Figure 6.

Chemical structures and quantities of 10 significant differential volatile metabolites in ‘JYHX’ and ‘JYHC’. The value bars with asterisks denote statistically significant differences: ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

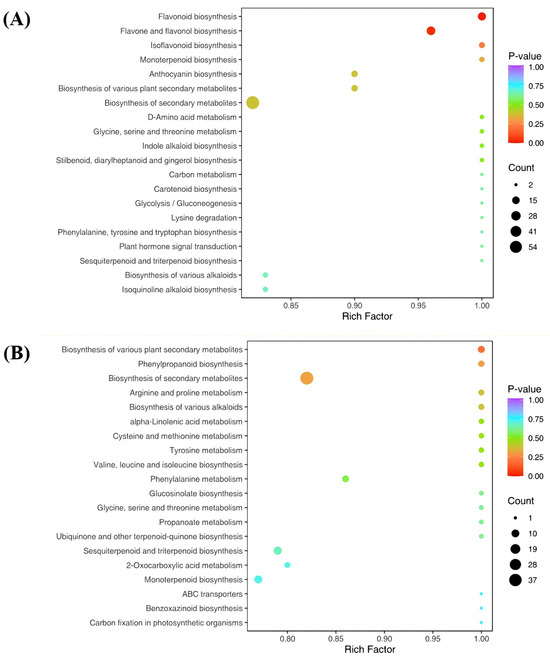

3.4. KEGG Pathway Analysis

To systematically investigate the biological implications of the observed metabolic changes, KEGG pathway enrichment analysis was performed to integrate the differential metabolites into functional pathways. In the ‘JYHC’ vs. ‘JYHG’ comparison, differential metabolites were annotated and enriched in 56 KEGG pathways. Among these, “flavonoid biosynthesis” and “flavone and flavonol biosynthesis” were significantly enriched (p < 0.05) (Figure 7A). In contrast, no pathways showed significant enrichment in the ‘JYHC’ vs. ‘JYHX’ comparison. Nevertheless, several pathways, including “biosynthesis of various plant secondary metabolites” and “biosynthesis of secondary metabolites”, exhibited relatively high enrichment factors, suggesting potential biological relevance.

Figure 7.

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) annotations and enrichment results. (A): ‘JYHC’ vs. ‘JYHG’ (B): ‘‘JYHC’’ vs. ‘JYHX’.

4. Discussion

Thermal drying is a conventional step in the processing of LJF, which may lead to the loss of bioactive constituents through condensation. To evaluate whether the condensate ‘JYHC’ possesses potential utility, this study analyzed the secondary metabolites and volatile components in ‘JYHC’ using metabolomics approaches.

In this study, the UPLC-MS/MS-based widely targeted metabolome was employed to profile the metabolites of ‘JYHC’ and ‘JYHG’. A total of 1651 secondary metabolites were detected, including flavonoids, terpenoids, alkaloids, phenolic acids, lignans, coumarins, quinones, tannins, etc. Flavonoids and terpenoids were identified as the predominant secondary metabolites in ‘JYHC’ (Figure 2A). Flavonoids and terpenoids are widely involved in biological defence and have important pharmacological roles in human health, including anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and antioxidant properties [24,25,26,27,28,29,30].

A comprehensive comparative analysis and identification of metabolic differences between ‘JYHC’ and ‘JYHX’ were performed using GC-MS. A total of 909 metabolites, including esters, terpenoids, ketones, heterocyclic compounds, alcohols, hydrocarbons, etc. (Figure 2B). Esters and terpenoids were established as the dominant volatile metabolites in ‘JYHC’. Terpenes are widely found in plant essential oils and have anthelmintic, antibacterial, and anti-inflammatory activities [31,32]. Esters are closely related to the plant aromas and are widely used in the food, cosmetic, and flavor industries [33,34]. The composition and content of volatile metabolites are significantly affected by drying methods. Sun drying is a traditional method of drying LJF. Research has found that, while sun-dried Lonicerae Flos exhibits a greater variety of volatile compounds, its overall content is lower and it primarily contains hydrocarbons [35]. This outcome may be attributed to prolonged exposure to sunlight and air, which increases susceptibility to oxidative and photolytic degradation. Currently, convective drying methods are the most widely used in the industrial production of LJF, including programmed temperature oven drying, heat-pump drying, and hot-air drying [36]. Research indicates that Lonicerae flos dried via programmed temperature oven drying contains higher levels of esters and terpenes compared to other high-temperature drying methods [35]. Heat-pump drying is an advanced drying technology characterized by low temperature, mild conditions, and stable operation. This method is particularly suitable for preserving temperature-sensitive volatile components, such as short-chain fatty acids and terpenes [37].

To elucidate the functional significance of the altered metabolome, this study focused on the upregulated metabolites. Based on extensive literature and database mining, 58 potentially biologically active upregulated differential metabolites were screened in the ‘JYHC’ and ‘JYHG’ group (Table 1). Terpenoids, phenolic acids, and alkaloids are the main upregulated differential metabolites in ‘JYHC’. Terpenoids include nootkatone, catalpol, and isosteviol, etc. Nootkatone is an aromatic sesquiterpenoid with insecticidal and anti-inflammatory activities [38,39,40]. It is often used as a natural insecticide [41]. Isosteviol has been served as a cardiomyocyte protector [42,43,44]. Catalpol exhibits cardiovascular protective, neuroprotective, and hepatoprotective effects that were linked to NF-κB/NLRP3, PI3K/Akt, VEGF-A/KDR, and Jak-Stat pathways [45,46,47,48,49]. Among them, phenolic acid components include mandelic acid, vanillic acid, aloesone, isochlorogenic acid B, etc. Studies have shown that they possess biological activities such as anti-inflammatory and antibacterial effects [50,51,52]. Mandelic acid is widely used as a vital component in antiseptics and cosmetics due to its excellent antibacterial and anti-inflammatory activities [53]. Isochlorogenic acid B is recognized as a key active component in LJF. It exhibits significant blood sugar-lowering effects [54]. The alkaloids mainly include allantoin, betaine, solavetivone, aurantiamide, and stachydrine. Allantoin has activities such as antibacterial effects and skin damage repair, making it used in the development of cosmetic products [55,56,57,58]. Evidence has shown that betaine has beneficial actions in several human diseases and has anti-inflammatory functions in many diseases [59,60,61]. Stachydrine is a compound with anti-inflammatory activity, reducing inflammation through the P65, JAK2/STAT3, and NF-κB signaling pathways [62,63,64].

Additionally, 186 previously unreported compounds were identified in ‘JYHC’ that have not been documented in LJF, many of which demonstrate insecticidal, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory activities (Table 2). Terpenoids accounted for the highest percentage of newly identified volatile components. Terpenoids generally have some antibacterial and anti-inflammatory activity; for example, isoborneol and hinokitiol have good antimicrobial activity and are used in the application and development of natural antimicrobial materials [65,66,67]. Agarospirol, α-cadinol have been proven to be the main anti-inflammatory active ingredient in natural plant essential oils [68,69,70]. Curcumin has significant anti-inflammatory activity and can treat osteoarthritis by inhibiting NF-κB and MAPK pathways [71]. Moreover, 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural is a common reaction product during heat processing with good anti-inflammatory activity [72,73]. Esculetin is a natural dihydroxy coumarin, which has been shown to prevent cell growth in a variety of cancers [74,75,76]. Palmitoleic acid has been shown to regulate the gut microbiota and promote intestinal homeostasis [77]. However, it should be noted that this study is limited by the lack of absolute quantification for some differential metabolites. Future work will focus on validating these results through the construction of a more comprehensive standard compound library.

5. Conclusions

This research utilized UPLC-ESI-MS/MS-based widely targeted metabolomics method and GC-MS-based volatile metabolomics to comprehensively profile the metabolites in ‘JYHC’. The results shown that ‘JYHC’ is abundant in diverse secondary and volatile metabolites. Flavonoids and terpenoids were identified as the predominant secondary metabolites, whereas esters and terpenoids dominated the volatile fraction. Comparative metabolomic analysis revealed 58 upregulated differential secondary metabolites, primarily consisting of terpenoids, phenolic acids, and alkaloids. Additionally, 186 previously unreported compounds were identified in LJF, including isoborneol, hi-nokitiol, Agarospirol, and α-cadinol, etc. These metabolites are suggested to possess potential biological activities, such as anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial effects.

In the future, ‘JYHC’ shows potential for application as a functional additive with antibacterial and anti-inflammatory properties in cosmetics, or as a plant-derived biopesticide in green agriculture. The comprehensive utilization of ‘JYHC’ could enhance the economic value of LJF, while simultaneously reducing resource waste and wastewater pollution associated with its traditional processing. This approach aligns closely with the principles of green and sustainable development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.S.; methodology, J.S., H.W. and C.Y.; software, J.Z.; validation, Y.S. and C.C.; formal analysis, L.L.; investigation, F.W.; resources, J.S.; data curation, B.F.; writing—original draft preparation, D.L.; writing—review and editing, D.L. and J.Z.; visualization, J.Z. and S.G.; supervision, J.S.; project administration, J.S., H.W. and C.Y.; funding acquisition, J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the 2024 Beijing City University fund, grant number KYTD202401. The 2024–2026 Young Talent Lifting Program of Beijing City University, grant number TJ202402. The Beijing City University Graduate Student Research and Innovation Programme, grant number Yjscx202438. The Key R&D Program of Shandong Province, grant number 2024SFGC0401. The Mount Taishan Scholar Young Expert. The Hebei Province major scientific and technological achievements transformation project, grant number 22287101Z.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Wuhan Metavir Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China) for their help with metabolomics analysis. In addition, the authors would like to thank Yantai Ruiga Energy Saving Technology Co., Ltd. (Shandong, China) for providing the LJF drying and recycling equipment, along with their staff, for their valuable technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LJF | Lonicerae japonicae flos |

| JYHC | Condensate water during the drying of Lonicerae japonicae flos |

| JYHX | Fresh Lonicerae japonicae flos |

| JYHG | Dry Lonicerae japonicae flos |

| UPLC-MS/MS | Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography-Electrospray Ionization-Tandem Mass Spectrometry |

| GC-MS | Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| OPLS-DA | Orthogonal partial least-squares discrimination analysis |

| VIP | Variable importance in projection |

| FC | Fold Change |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

References

- Ma, P.; Yuan, L.; Jia, S.; Zhou, Z.; Xu, D.; Huang, S.; Meng, F.; Zhang, Z.; Nan, Y. Lonicerae japonicae flos With the Homology of Medicine and Food: A Review of Active Ingredients, Anticancer Mechanisms, Pharmacokinetics, Quality Control, Toxicity and Applications. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1446328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Liu, S.; Hou, A.; Wang, S.; Na, Y.; Hu, J.; Jiang, H.; Yang, L. Systematic Review of Lonicerae japonicae Flos: A Significant Food and Traditional Chinese Medicine. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1013992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, B.; Hu, X.; Dong, S.; Hong, M.; Wang, J.; Chen, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Li, X.; et al. Deciphering the Formulation Secret Underlying Chinese Huo-Clearing Herbal Drink. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 654699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Jiang, Q.; Hu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J. Research Progress on Chemical Constituents of Lonicerae japonicae Flos. Biomed. Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 8968940. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Li, W.; Fu, C.; Song, Y.; Fu, Q. Lonicerae japonicae flos and Lonicerae flos: A Systematic Review of Ethnopharmacology, Phytochemistry, and Pharmacology. Phytochem. Rev. 2020, 19, 1–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Cai, W.; Weng, X.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yang, Q.; Guo, Y.; Zhu, X.; et al. Lonicerae japonicae flos and Lonicerae flos: A Systematic Pharmacology Review. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2015, 2015, 905063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Zeng, S.; Chen, L.; Sun, Q.; Liu, M.; Yang, H.; Ren, S.; Ming, T.; Meng, X.; Xu, H. Updated Pharmacological Effects of Lonicerae japonicae flos, With a Focus on Its Potential Efficacy on Coronavirus Disease-2019 (COVID-19). Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2021, 60, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmanpour Kalalagh, K.; Mohebodini, M.; Fattahi, R.; Beyraghdar Kashkooli, A.; Davarpanah Dizaj, S.; Salehifar, F.; Mokhtari, A.M. Drying Temperatures Affect the Qualitative-Quantitative Variation of Aromatic Profiling in Anethum graveolens L. Ecotypes as an Industrial-Medicinal-Vegetable Plant. Front. Plant. Sci. 2023, 14, 1137840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazrati, S.; Lotfi, K.; Govahi, M.; Ebadi, M.T. A Comparative Study: Influence of Various Drying Methods on Essential Oil Components and Biological Properties of Stachys lavandulifolia. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 9, 2612–2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiocchio, I.; Mandrone, M.; Tacchini, M.; Guerrini, A.; Poli, F. Phytochemical Profile and In Vitro Bioactivities of Plant-Based By-Products in View of a Potential Reuse and Valorization. Plants 2023, 12, 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Panesar, P.S.; Chopra, H.K. Citrus Processing By-Products: An Overlooked Repository of Bioactive Compounds. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asma, U.; Morozova, K.; Ferrentino, G.; Scampicchio, M. Apples and Apple By-Products: Antioxidant Properties and Food Applications. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-Gallego, R.; Silva, P. The Wine Industry By-Products: Applications for Food Industry and Health Benefits. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Fernández-Sobrino, R.; Torres-Fuentes, C.; Bravo, F.I.; Muguerza, B. Winery By-Products as a Valuable Source for Natural Antihypertensive Agents. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 7708–7721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reguengo, L.M.; Salgaço, M.K.; Sivieri, K.; Maróstica Júnior, M.R. Agro-Industrial By-Products: Valuable Sources of Bioactive Compounds. Food Res. Int. 2022, 152, 110871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santorelli, L.; Caterino, M.; Costanzo, M. Proteomics and Metabolomics in Biomedicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P.R.; Carrageta, D.F.; Oliveira, P.F.; Rodrigues, A.; Alves, M.G.; Monteiro, M.P. Metabolomics as a Tool for the Early Diagnosis and Prognosis of Diabetic Kidney Disease. Med. Res. Rev. 2022, 42, 1518–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Zhang, D. Plant Metabolomics and Metabolic Biology. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2014, 56, 814–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, M.; Kumar Patel, M.; Kumar, N.; Bajpai, A.B.; Siddique, K.H.M. Metabolomics and Molecular Approaches Reveal Drought Stress Tolerance in Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga-Corral, M.; Carpena, M.; Garcia-Oliveira, P.; Pereira, A.G.; Prieto, M.A.; Simal-Gandara, J. Analytical Metabolomics and Applications in Health, Environmental and Food Science. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2022, 52, 712–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Y.J. MS based foodomics: An Edge Tool Integrated Metabolomics and Proteomics for Food Science. Food Chem. 2024, 446, 138852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Ma, P.; Yan, Y.; Huang, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, X. Widely Targeted Metabolomics Analysis Reveals the Differences in Nonvolatile Compounds of Citronella Before and After Drying. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2023, 37, e5620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, G.; Su, S.; Yan, P.; Shang, J.; Wang, J.; Yan, C.; Li, J.; Wang, Q.; Xiong, X.; Xu, H. Integrative Analyses of Widely Targeted Metabolomic Profiling and Derivatization-Based LC-MS/MS Reveals Metabolic Changes of Zingiberis Rhizoma and Its Processed Products. Food Chem. 2022, 389, 133068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, X.J.; Chen, J.B.; Cao, J.P.; Li, X.; Sun, C.D. Citrus Flavonoids and Their Antioxidant Evaluation. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 3833–3854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, M.C.; Pinto, D.; Silva, A.M.S. Plant Flavonoids: Chemical Characteristics and Biological Activity. Molecules 2021, 26, 5377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rakha, A.; Umar, N.; Rabail, R.; Butt, M.S.; Kieliszek, M.; Hassoun, A.; Aadil, R.M. Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Allergic Potential of Dietary Flavonoids: A Review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 156, 113945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Jiang, L.; Ran, W.; Zhong, K.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, H. Antimicrobial Activities of Natural Flavonoids Against Foodborne Pathogens and Their Application in Food Industry. Food Chem. 2024, 460, 140476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Biharee, A.; Kumar, A.; Jaitak, V. Antimicrobial Terpenoids as a Potential Substitute in Overcoming Antimicrobial Resistance. Curr. Drug Targets 2020, 21, 1476–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhong, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhuo, X.; Li, J.; Jiang, X.; Ye, X.Y.; Xie, T.; Bai, R. Natural Terpenoids with Anti-Inflammatory Activities: Potential Leads for Anti-Inflammatory Drug Discovery. Bioorg. Chem. 2022, 124, 105817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grassmann, J. Terpenoids as Plant Antioxidants. Vitam. Horm. 2005, 72, 505–535. [Google Scholar]

- Solórzano-Santos, F.; Miranda-Novales, M.G. Essential Oils from Aromatic Herbs as Antimicrobial Agents. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2012, 23, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falleh, H.; Ben Jemaa, M.; Saada, M.; Ksouri, R. Essential Oils: A Promising Eco-Friendly Food Preservative. Food Chem. 2020, 330, 127268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; He, L.; Song, Y.; Zhang, P.; Chen, D.; Guan, L.; Liu, S. Comprehensive Study of Volatile Compounds and Transcriptome Data Providing Genes for Grape Aroma. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, Y.; Zhao, W.; Xiao, Z.; Zhu, J.; Xiong, W.; Chen, F. Characterization of Aroma Compounds and Effects of Amino Acids on the Release of Esters in Laimao Baijiu. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2023, 103, 1784–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Wang, F.; Liu, J.; Zou, Y.; Chen, X. A comparison of volatile fractions obtained from Lonicera macranthoides via different extraction processes: Ultrasound, microwave, Soxhlet extraction, hydrodistillation, and cold maceration. Integr. Med. Res. 2015, 4, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.-F.; Guo, X.-M.; Hao, X.-F.; Feng, S.-H.; Hu, Y.-J.; Yang, Y.-Q.; Wang, H.-F.; Yu, Y.-J. Untargeted metabolomics study of Lonicerae japonicae flos processed with different drying methods via GC-MS and UHPLC-HRMS in combination with chemometrics. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 186, 115179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Han, J.; Fu, L.; Shang, H.; Yang, L. Assessment of characteristics aroma of heat pump drying (HPD) jujube based on HS-SPME/GC–MS and e-nose. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2022, 110, 104402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra Rodrigues Dantas, L.; Silva, A.L.M.; da Silva Júnior, C.P.; Alcântara, I.S.; Correia de Oliveira, M.R.; Oliveira Brito Pereira Bezerra Martins, A.; Ribeiro-Filho, J.; Coutinho, H.D.M.; Rocha Santos Passos, F.; Quintans-Junior, L.J.; et al. Nootkatone Inhibits Acute and Chronic Inflammatory Responses in Mice. Molecules 2020, 25, 2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galisteo Pretel, A.; Pérez del Pulgar, H.; Olmeda, A.S.; Gonzalez-Coloma, A.; Barrero, A.F.; Quílez del Moral, J.F. Novel Insect Antifeedant and Ixodicidal Nootkatone Derivatives. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, Z.; Zibao, H.; Zhi, Z.; Ning, M.; Ruiqi, W.; Mimi, C.; Xiaowen, H.; Lin, D.; Zhixuan, X.; Qiang, L.; et al. Nootkatone, a Sesquiterpene Ketone From Alpiniae oxyphyllae Fructus, Ameliorates Metabolic-Associated Fatty Liver by Regulating AMPK and MAPK Signaling. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 909280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, E.J.; Chen, R.; Li, Z.; Geldenhuys, W.; Bloomquist, J.R.; Swale, D.R. Mode of Action and Toxicological Effects of the Sesquiterpenoid, Nootkatone, in Insects. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2022, 183, 105085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Beng, H.; Su, H.; Han, F.; Fan, Z.; Lv, N.; Jovanović, A.; Tan, W. Isosteviol Prevents the Development of Isoprenaline-Induced Myocardial Hypertrophy. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2019, 44, 1932–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Song, L.; Lu, Z.; Sun, T.; Lun, J.; Zhou, C.; Sun, X.; Tan, W.; Zhao, H. Isosteviol Improves Cardiac Function and Promotes Angiogenesis After Myocardial Infarction in Rats. Cell Tissue Res. 2022, 387, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, B.; Xu, G.; Xu, C.; Ou, E.; Liu, J.; Sun, X.; Zhao, Y. Synthesis and In Vivo Screening of Isosteviol Derivatives as New Cardioprotective Agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 219, 113396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.Y.; Feng, J.T.; Zhou, Z.Y.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Ma, S.Z.; Wang, X.Q.; Zhang, B. Catalpol Alleviates Heat Stroke-Induced Liver Injury in Mice by Downregulating the JAK/STAT Signaling Pathway. Phytomedicine 2024, 132, 155853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, H.; Rui, Q.; Kan, X.; Gao, R.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, B. Catalpol Ameliorates Oxidative Stress and Neuroinflammation after Traumatic Brain Injury in Rats. Neurochem. Res. 2023, 48, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savova, M.S.; Mihaylova, L.V.; Tews, D.; Wabitsch, M.; Georgiev, M.I. Targeting PI3K/AKT Signaling Pathway in Obesity. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 159, 114244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, Y.; Shao, C.Y.; Liu, Y.F.; Huang, Y.; Yang, J.; Wan, H.T. Catalpol Reduces LPS-Induced BV2 Immunoreactivity Through NF-κB/NLRP3 Pathways: An In Vitro and In Silico Study. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1415445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Xu, Y.; Yu, N.; Zhang, M.; Wang, J.; Wan, D.; Tian, Z.; Zhu, H. Catalpol Alleviates Ischemic Stroke Through Promoting Angiogenesis and Facilitating Proliferation and Differentiation of Neural Stem Cells via the VEGF-A/KDR Pathway. Mol. Neurobiol. 2023, 60, 6227–6247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magiera, A.; Kołodziejczyk-Czepas, J.; Olszewska, M.A. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Vanillic Acid in Human Plasma, Human Neutrophils, and Non-Cellular Models In Vitro. Molecules 2025, 30, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziadlou, R.; Barbero, A.; Martin, I.; Wang, X.; Qin, L.; Alini, M.; Grad, S. Anti-Inflammatory and Chondroprotective Effects of Vanillic Acid and Epimedin C in Human Osteoarthritic Chondrocytes. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xiong, Z.; Li, C.; Liu, D.; Li, X.; Xu, J.; Chen, N.; Wang, X.; Li, Q.; Li, Y. Multiple Beneficial Effects of Aloesone from Aloe vera on LPS-Induced RAW264.7 Cells, Including the Inhibition of Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, M1 Polarization, and Apoptosis. Molecules 2023, 28, 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egner, P.; Pavlačková, J.; Sedlaříková, J.; Pleva, P.; Mokrejš, P.; Janalíková, M. Non-Alcohol Hand Sanitiser Gels with Mandelic Acid and Essential Oils. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Zhao, D.; Leng, Y.; Chen, C.; Xiao, K.; Wu, Z.; Chen, F. Identification of the Hypoglycemic Active Components of Lonicera japonica Thunb. and Lonicera hypoglauca Miq. by UPLC-Q-TOF-MS. Molecules 2024, 29, 4848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manca, M.L.; Matricardi, P.; Cencetti, C.; Peris, J.E.; Melis, V.; Carbone, C.; Escribano, E.; Zaru, M.; Fadda, A.M.; Manconi, M. Combination of Argan Oil and Phospholipids for the Development of an Effective Liposome-Like Formulation Able to Improve Skin Hydration and Allantoin Dermal Delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2016, 505, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nokoorani, Y.D.; Shamloo, A.; Bahadoran, M.; Moravvej, H. Fabrication and Characterization of Scaffolds Containing Different Amounts of Allantoin for Skin Tissue Engineering. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saucedo-Acuña, R.A.; Meza-Valle, K.Z.; Cuevas-González, J.C.; Ordoñez-Casanova, E.G.; Castellanos-García, M.I.; Zaragoza-Contreras, E.A.; Tamayo-Pérez, G.F. Characterization and In Vivo Assay of Allantoin-Enriched Pectin Hydrogel for the Treatment of Skin Wounds. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaqoob, N.; Imtiaz, F.; Shafiq, N.; Rehman, S.; Munir, H.; Bourhia, M.; Almaary, K.S.; Nafidi, H.A. Oleogels for the Promotion of Healthy Skin Care Products: Synthesis and Characterization of Allantoin-Containing Moringa-Based Oleogel. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2024, 25, 2326–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhu, G.; Huang, R.; Yin, Y.; Ren, W. Betaine Inhibits Interleukin-1β Production and Release: Potential Mechanisms. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; He, F.; Wu, C.; Li, P.; Li, N.; Deng, J.; Zhu, G.; Ren, W.; Peng, Y. Betaine in Inflammation: Mechanistic Aspects and Applications. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Yang, Y.; Chen, C.; Jing, T.; Hu, Y.; Xu, H.; Wang, S.; He, Y.; Liu, E.; Cui, J. Betaine Supplementation Alleviates Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Colitis via Regulating the Inflammatory Response, Enhancing the Intestinal Barrier, and Altering Gut Microbiota. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 12814–12826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Sun, L.; Qiu, Y.; Zhu, W.; Hu, K.; Mao, J. Protective Effect of Stachydrine Against Cerebral Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury by Reducing Inflammation and Apoptosis Through P65 and JAK2/STAT3 Signaling Pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Zhang, M.; Li, W.; Zhu, S.; Zhang, D. Stachydrine Attenuates IL-1β-Induced Inflammatory Response in Osteoarthritis Chondrocytes Through the NF-κB Signaling Pathway. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2020, 326, 109136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, A.; Wu, Y.; Guan, W.; Xiong, B.; Peng, X.; Wei, X.; Chen, C.; Liu, Z. Stachydrine Ameliorates Carbon Tetrachloride-Induced Hepatic Fibrosis by Inhibiting Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Regulating MMPs/TIMPs System in Rats. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 97, 1586–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado Querido, M.; Paulo, I.; Hariharakrishnan, S.; Rocha, D.; Pereira, C.C.; Barbosa, N.; Bordado, J.M.; Teixeira, J.P.; Galhano Dos Santos, R. Auto-Disinfectant Acrylic Paints Functionalised with Triclosan and Isoborneol-Antibacterial Assessment. Polymers 2021, 13, 2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhao, X.; Luo, Y.; Zheng, K.; Wu, M. Highly Effective Antibacterial AgNPs@Hinokitiol Grafted Chitosan for Construction of Durable Antibacterial Fabrics. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 209, 963–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebia, R.A.; Binti Sadon, N.S.; Tanaka, T. Natural Antibacterial Reagents (Centella, Propolis, and Hinokitiol) Loaded into Poly[(R)-3-hydroxybutyrate-co-(R)-3-hydroxyhexanoate] Composite Nanofibers for Biomedical Applications. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Nascimento, A.L.; Guedes, J.B.; Costa, W.K.; de Veras, B.O.; de Aguiar, J.; Navarro, D.; Correia, M.; Napoleão, T.H.; de Oliveira, A.M.; da Silva, M.V. Essential Oil from the Leaves of Eugenia pohliana DC. (Myrtaceae) Alleviates Nociception and Acute Inflammation in Mice. Inflammopharmacology 2022, 30, 2273–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos de Moraes, P.G.; da Silva Santos, I.B.; Silva, V.B.G.; Dede Oliveira FariasAguiar, J.C.R.; do Amaral Ferraz Navarro, D.M.; de Oliveira, A.M.; Dos Santos Correia, M.T.; Costa, W.K.; da Silva, M.V. Essential Oil from Leaves of Myrciaria floribunda (H. West ex Willd.) O. Berg Has Antinociceptive and Anti-Inflammatory Potential. Inflammopharmacology 2023, 31, 3143–3151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasni, M.; Belboukhari, N.; Sekkoum, K.; Stefan-van Staden, R.I.; Alothman, Z.A.; Demir, E.; Ali, I. Heliotropium bacciferum Essential Oil Extraction: Composition Determination by GC-MS and Anti-Inflammatory and Antibacterial Activities Evaluation. Anal. Biochem. 2023, 683, 115366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Z.; Chen, C.; Han, C.; Li, X.; Tian, H.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, K.; Zhou, T.; et al. Curcumenol Mitigates Chondrocyte Inflammation by Inhibiting the NF-κB and MAPK Pathways and Ameliorates DMM-Induced OA in Mice. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2021, 48, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Han, X.; Ma, J.; Zhang, R.; Zou, K.; Wang, X.; Yuan, W.; Qiu, M.; Chen, J.; Yang, Y.; et al. 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural Attenuates Osteoarthritis by Upregulating Glucose Metabolism in Chondrocytes. Phytomedicine 2025, 139, 156499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Jiang, Z.; Shen, C.; Zou, H.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, K.; Bai, R.; Kang, Y.; Ye, X.Y.; Xie, T. 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural Alleviates Inflammatory Lung Injury by Inhibiting Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 782427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, R.; Sawney, S.; Saini, V.; Steffi, C.; Tiwari, M.; Saluja, D. Esculetin Induces Antiproliferative and Apoptotic Responses in Pancreatic Cancer Cells by Directly Binding to KEAP1. Mol. Cancer 2016, 15, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.; Su, G.; Chen, X.; Chen, S.; Li, Q.; Xie, B.; Zhao, Y. Esculetin Inhibits Endometrial Cancer Proliferation and Promotes Apoptosis via hnRNPA1 to Downregulate BCLXL and XIAP. Cancer Lett. 2021, 521, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.T.; Liu, B.; Ai, Z.Z.; Hong, Z.C.; You, P.T.; Wu, H.Z.; Yang, Y.F. Esculetin Inhibits Cancer Cell Glycolysis by Binding Tumor PGK2, GPD2, and GPI. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Mai, Q.; Chen, Z.; Lin, T.; Cai, Y.; Han, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Tan, S.; Wu, Z.; et al. Dietary Palmitoleic Acid Reprograms Gut Microbiota and Improves Biological Therapy Against Colitis. Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2211501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).