Metabolomic Profiling of Long-Lived Individuals Reveals a Distinct Subgroup with Cardiovascular Disease and Elevated Butyric Acid Derivatives

Abstract

1. Introduction

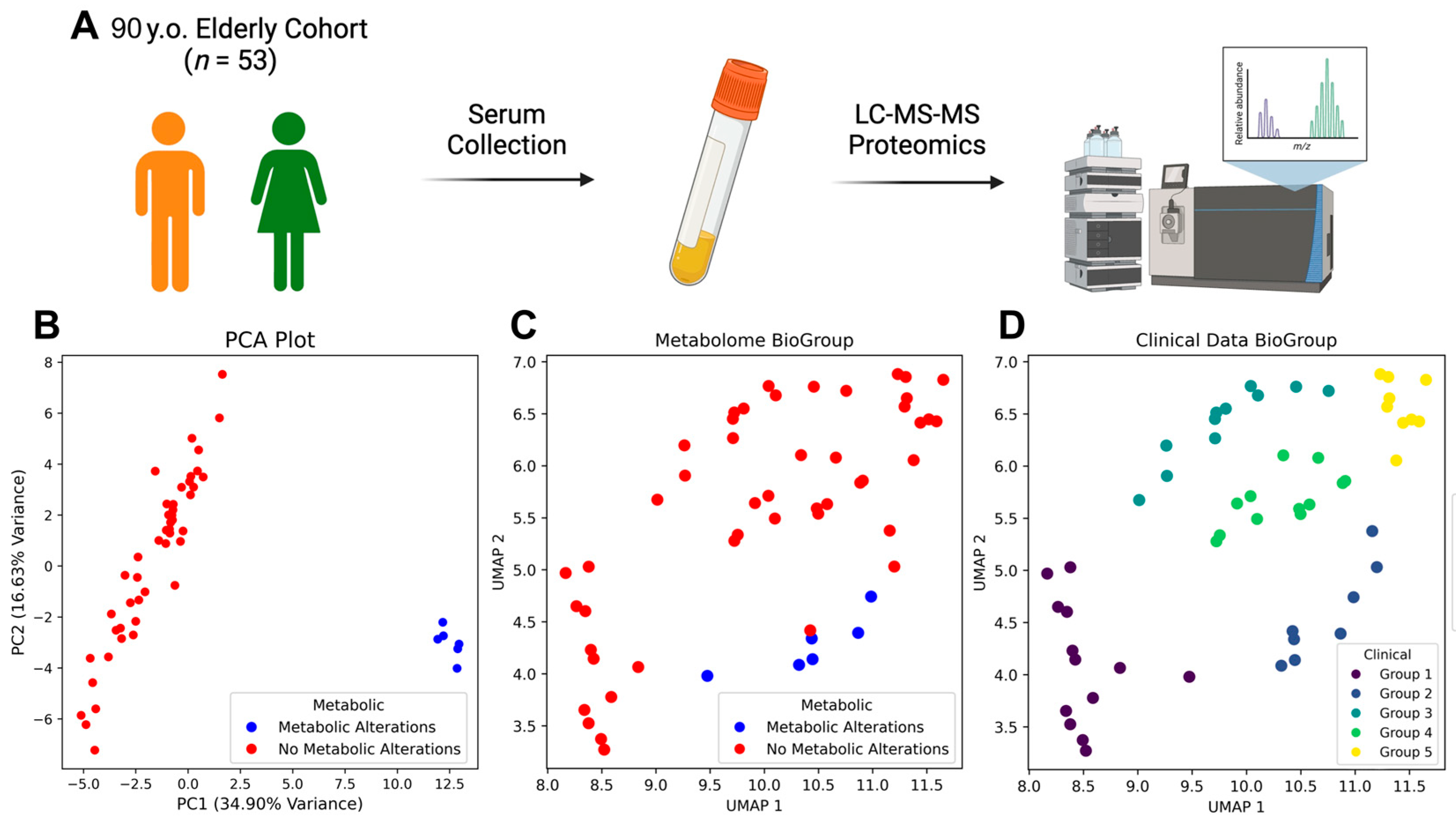

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Processing

2.2. Clinical Data Collection

2.2.1. Functional Assessments

2.2.2. Clinical Assessments and Equipment

2.2.3. Vascular Assessment Protocols

2.2.4. Comorbidity Definitions

2.2.5. Laboratory Analyses

2.2.6. Sample Collection and Processing

2.3. LC-MS/MS

2.3.1. Metabolite Extraction Protocol

2.3.2. Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography Parameters

2.3.3. Mass Spectrometry Detection Parameters

2.4. LC-MS/MS Data Analysis

2.4.1. Data Pre-Processing

- Quality Control

- Data Processing and Peak Detection

- Normalization and Transformation

- Feature Filtering

- Missing Value Handling

- Group Assignment

Dimensionality Reduction

2.4.2. Statistical Analysis

2.4.3. Assumptions and Validation

2.4.4. Pathway Enrichment Analysis

2.5. Individual Clinical Data Analysis and Integration with Metabolomic Data

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of Study Population

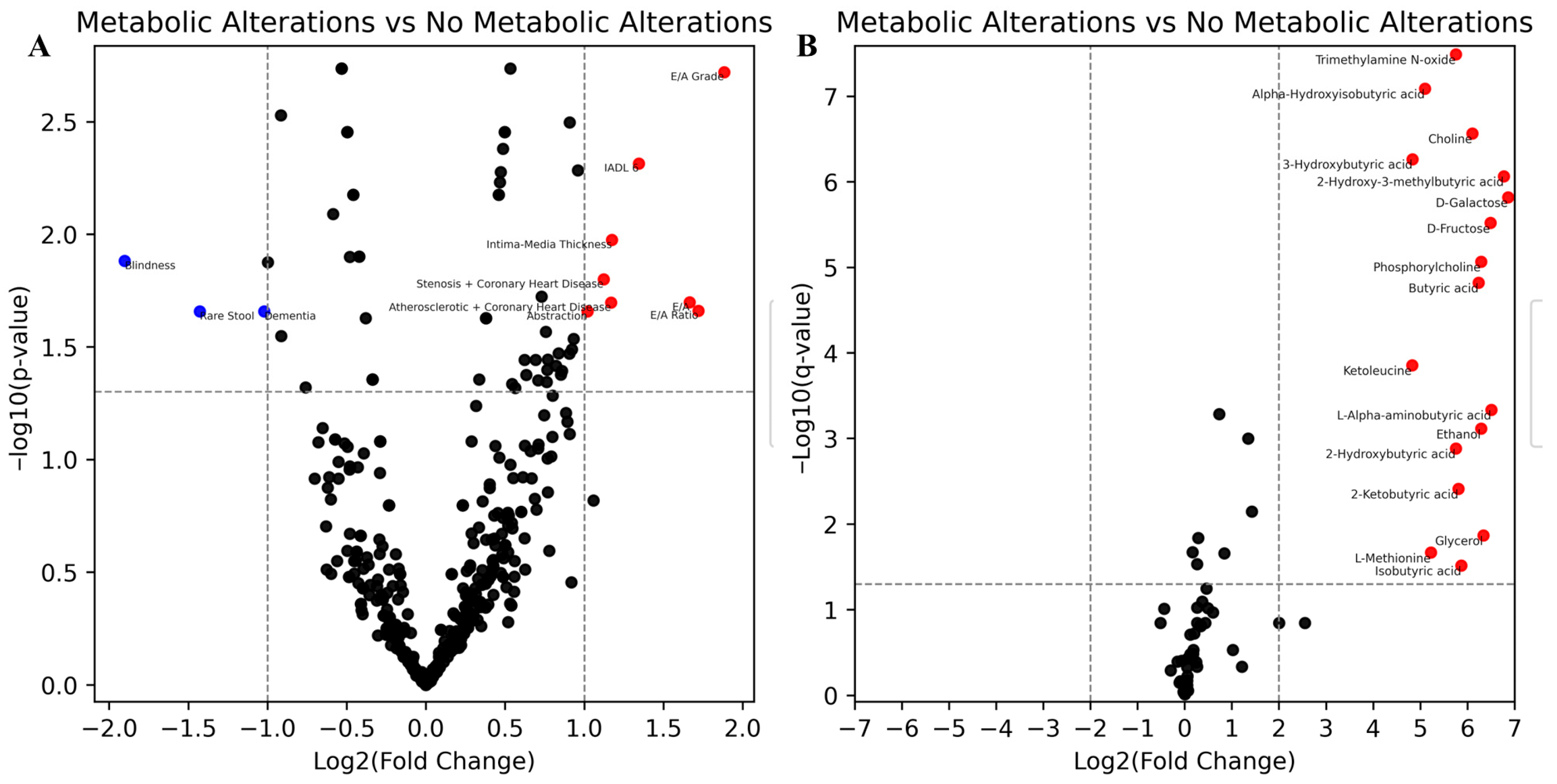

3.2. Differentially Abundant Metabolites Between Groups

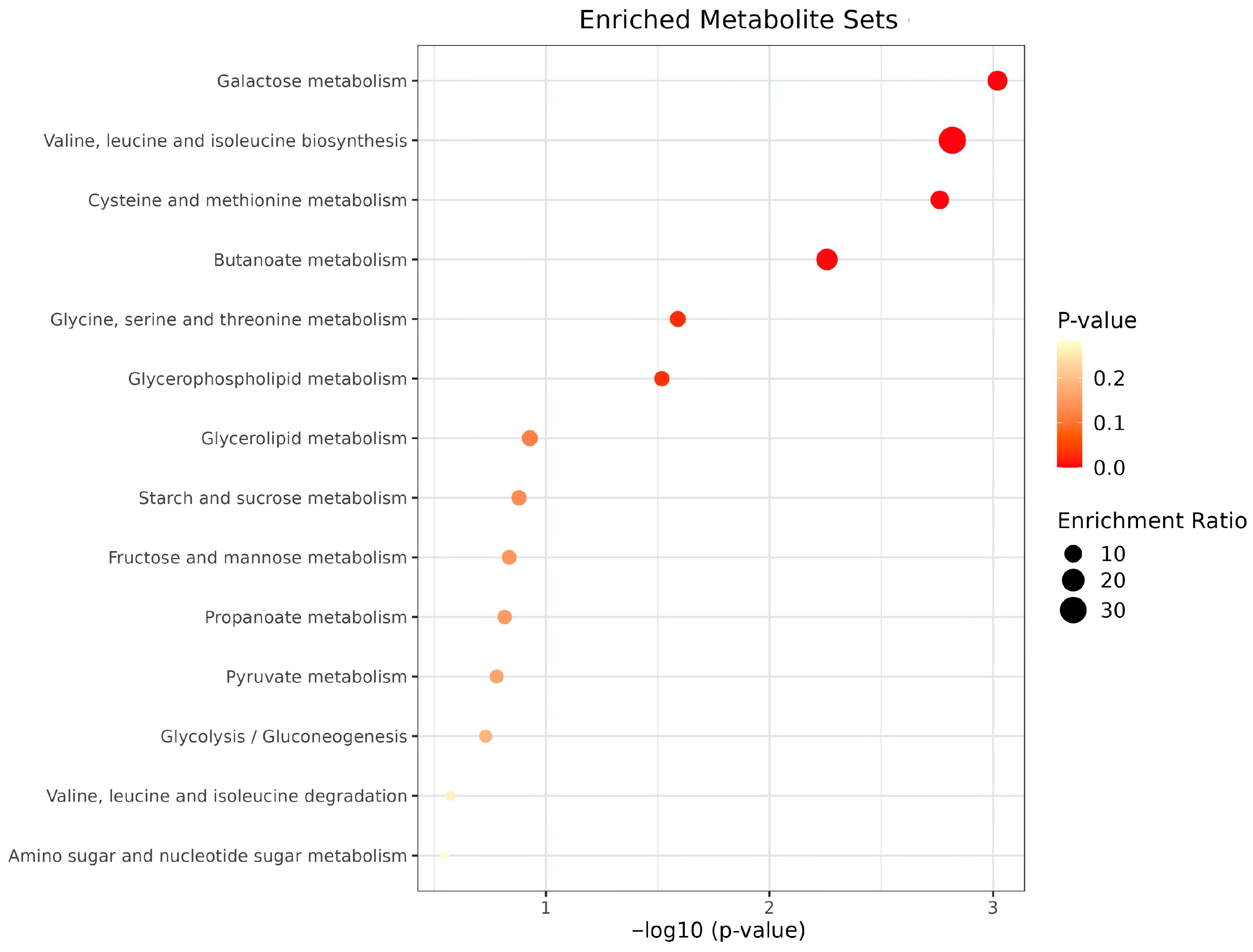

3.3. Pathway Enrichment Analysis

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rodríguez-Rodero, S.; Fernández-Morera, J.L.; Menéndez-Torre, E.; Calvanese, V.; Fernández, A.F.; Fraga, M.F. Aging genetics and aging. Aging Dis. 2011, 2, 186–195. [Google Scholar]

- Gianfredi, V.; Nucci, D.; Pennisi, F.; Maggi, S.; Veronese, N.; Soysal, P. Aging, longevity, and healthy aging: The public health approach. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2025, 37, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, C.; Sun, L.; Wang, W.; Gong, W. Biomarkers of Aging and Relevant Evaluation Techniques: A Comprehensive Review. Aging Dis. 2024, 15, 977–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, A.; Imran, M.; Ahsan, H. Biomarkers as Biomedical Bioindicators: Approaches and Techniques for the Detection, Analysis, and Validation of Novel Biomarkers of Diseases. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizo-Roca, D.; Henderson, J.D.; Zierath, J.R. Metabolomics in cardiometabolic diseases: Key biomarkers and therapeutic implications for insulin resistance and diabetes. J. Intern. Med. 2025, 297, 584–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barajas-Martínez, A.; Easton, J.F.; Rivera, A.L.; Martínez-Tapia, R.; de la Cruz, L.; Robles-Cabrera, A.; Stephens, C.R. Metabolic Physiological Networks: The Impact of Age. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 587994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Murata, S.; Schmidt-Mende, K.; Ebeling, M.; Modig, K. Do people reach 100 by surviving, delaying, or avoiding diseases? A life course comparison of centenarians and non-centenarians from the same birth cohorts. Geroscience 2025, 47, 3539–3549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Lu, Y.; Mu, C.; Tang, P.; Liu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Luo, H.; Liu, J.Y.; Li, X. The Biomarkers in Extreme Longevity: Insights Gained from Metabolomics and Proteomics. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2024, 21, 2725–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stec-Martyna, E.; Wojtczak, K.; Nowak, D.; Stawski, R. Battle of the Biomarkers of Systemic Inflammation. Biology 2025, 14, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hai, P.C.; Yao, D.X.; Zhao, R.; Dong, C.; Saymuah, S.; Pan, Y.S.; Gu, Z.F.; Wang, Y.L.; Wang, C.; Gao, J.L. BMI, Blood Pressure, and Plasma Lipids among Centenarians and Their Offspring. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2022, 2022, 3836247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, D.K.; Trinh, K.T.L. Emerging Biomarkers in Metabolomics: Advancements in Precision Health and Disease Diagnosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebastiani, P.; Monti, S.; Lustgarten, M.S.; Song, Z.; Ellis, D.; Tian, Q.; Schwaiger-Haber, M.; Stancliffe, E.; Leshchyk, A.; Short, M.I.; et al. Metabolite signatures of chronological age, aging, survival, and longevity. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 114913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moqri, M.; Herzog, C.; Poganik, J.R.; Justice, J.; Belsky, D.W.; Higgins-Chen, A.; Moskalev, A.; Fuellen, G.; Cohen, A.A.; Bautmans, I.; et al. Biomarkers of aging for the identification and evaluation of longevity interventions. Cell 2023, 186, 3758–3775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragonnaud, E.; Biragyn, A. Gut microbiota as the key controllers of “healthy” aging of elderly people. Immun. Ageing 2021, 18, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yi, Y.; Yan, R.; Hu, R.; Sun, W.; Zhou, W.; Zhou, H.; Si, X.; Ye, Y.; Li, W.; et al. Impact of age-related gut microbiota dysbiosis and reduced short-chain fatty acids on the autonomic nervous system and atrial fibrillation in rats. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11, 1394929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.-H.; Xie, R.-Y.; Liu, X.-L.; Chen, S.-D.; Tang, H.-D. Mechanisms of Short-Chain Fatty Acids Derived from Gut Microbiota in Alzheimer’s Disease. Aging Dis. 2022, 13, 1252–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perik-Zavodskii, R.; Perik-Zavodskaia, O. BulkOmicsTools (1.0.0); Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Psychogios, N.; Young, N.; Wishart, D.S. MetaboAnalyst: A web server for metabolomic data analysis and interpretation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, W652–W660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnes, L.; Healy, J.; Melville, J. Umap: Uniform manifold approximation and projection for dimension reduction. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1802.03426. [Google Scholar]

- McInnes, L.; Healy, J.; Astels, S. hdbscan: Hierarchical density-based clustering. J. Open-Source Softw. 2017, 2, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perik-Zavodskaia, O.; Perik-Zavodskii, R.; Alrhmoun, S.; Nazarov, K.; Shevchenko, J.; Zaitsev, K.; Sennikov, S. Multi-omic analysis identifies erythroid cells as the major population in mouse placentas expressing genes for antigen presentation in MHC class II, chemokines, and antibacterial immune response. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1644983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onyszkiewicz, M.; Gawrys-Kopczynska, M.; Konopelski, P.; Aleksandrowicz, M.; Sawicka, A.; Koźniewska, E.; Samborowska, E.; Ufnal, M. Butyric acid, a gut bacteria metabolite, lowers arterial blood pressure via colon-vagus nerve signaling and GPR41/43 receptors. Pflugers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 2019, 471, 1441–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashtanova, D.; Tkacheva, O.N.; Kotovskaya, Y.U.; Dudinskaya, E.N.; Brailova, N.V.; Plokhova, E.V.; Onuchina, Y.U.; Sharashkina, N.V.; Eruslanova, K.A. P2251 Association between low-grade inflammation, metabolic factors, vascular biomarkers and gut microbiota in different age groups. Eur. Heart J. 2019, 40, ehz748.0729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Total (n = 53) | Metabolic Alterations (n = 6) | No Metabolic Alterations (n = 47) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, years | 98.0 [97.0–99.0] | 97.5 [97.0–98.0] | 98.0 [97.0–99.0] | 0.26 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 7 (13.2) | 2 (33.3) | 5 (10.6) | 0.17 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.6 [21.8–27.6] | 25.4 [21.1–27.4] | 24.6 [22.0–27.7] | 0.79 |

| Centenarians (age ≥ 100 years), n (%) | 8 (15.1) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (17.0) | 0.57 |

| Functional and Social Status | ||||

| Disability, n (%) | 46 (86.8) | 6 (100.0) | 40 (85.1) | 0.58 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 42 (79.2) | 5 (83.3) | 37 (78.7) | 1.00 |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 32 (60.4) | 5 (83.3) | 27 (57.4) | 0.38 |

| Chronic heart failure, n (%) | 19 (35.8) | 4 (66.7) | 15 (31.9) | 0.17 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 4 (7.5) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (8.5) | 1.00 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.2) | 1.00 |

| COPD, n (%) | 7 (13.2) | 1 (16.7) | 6 (12.8) | 1.00 |

| Laboratory Parameters | ||||

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 123.0 [112.5–130.5] | 129.5 [120.8–131.5] | 122.0 [112.0–130.0] | 0.30 |

| Leukocytes, ×109/L | 6.4 [5.2–7.8] | 6.3 [5.9–6.5] | 6.6 [5.1–7.8] | 0.94 |

| Platelets, ×109/L | 233.0 [180.5–261.5] | 163.0 [140.2–228.5] | 234.0 [187.0–269.0] | 0.07 |

| Albumin, g/L | 38.3 [35.9–40.1] | 39.0 [38.1–39.6] | 38.1 [35.3–40.5] | 0.73 |

| Creatinine, µmol/L | 92.3 [79.4–106.4] | 96.3 [88.1–124.4] | 92.3 [78.9–105.2] | 0.39 |

| AST, U/L | 20.1 [17.5–25.2] | 23.4 [19.5–27.3] | 19.4 [17.1–25.0] | 0.19 |

| ALT, U/L | 8.9 [7.5–12.1] | 12.4 [9.8–18.0] | 8.7 [7.2–11.7] | 0.06 |

| Rank | Metabolite | Log2(Fold Change) | p-Value | Q-Value | Metabolic Alterations (log2) | No Metabolic Alterations (log2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | D-Galactose | 6.86 | 1.09 × 10−7 | 8.87 × 10−7 | 7.64 | 0.78 |

| 2 | 2-Hydroxy-3-methylbutyric acid | 6.77 | 7.97 × 10−8 | 8.63 × 10−7 | 7.54 | 0.77 |

| 3 | L-Alpha-aminobutyric acid | 6.51 | 8.58 × 10−5 | 4.65 × 10−4 | 7.25 | 0.74 |

| 4 | D-Fructose | 6.49 | 9.77 × 10−8 | 8.87 × 10−7 | 7.23 | 0.73 |

| 5 | Ethanol | 6.29 | 6.12 × 10−4 | 1.63 × 10−3 | 6.99 | 0.70 |

| 6 | Phosphorylcholine | 6.29 | 8.60 × 10−6 | 6.51 × 10−5 | 6.98 | 0.69 |

| 7 | Butyric acid | 6.24 | 1.51 × 10−5 | 9.79 × 10−5 | 6.93 | 0.69 |

| 8 | Choline | 6.11 | 3.62 × 10−8 | 5.45 × 10−7 | 6.79 | 0.69 |

| 9 | 2-Ketobutyric acid | 5.81 | 3.88 × 10−3 | 8.39 × 10−3 | 6.46 | 0.65 |

| 10 | Trimethylamine N-oxide | 5.75 | 1.89 × 10−9 | 4.09 × 10−8 | 6.40 | 0.65 |

| 11 | 2-Hydroxybutyric acid | 5.75 | 1.30 × 10−3 | 2.81 × 10−3 | 6.39 | 0.64 |

| 12 | Alpha-Hydroxyisobutyric acid | 5.10 | 1.42 × 10−9 | 4.09 × 10−8 | 5.67 | 0.58 |

| 13 | 3-Hydroxybutyric acid | 4.84 | 4.19 × 10−8 | 5.45 × 10−7 | 5.38 | 0.55 |

| 14 | Ketoleucine | 4.83 | 1.00 × 10−4 | 4.87 × 10−4 | 5.37 | 0.54 |

| № | Pathway ID | Pathway Name | Category | Metabolites | Fold Enrichment (95% CI) | p-Value | FDR | Sig. | Metabolite IDs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | map05231 | Choline metabolism in cancer | Human Diseases | 2 | 85.6 (72.8–98.4) | 2.28 × 10−4 | 0.0008 | *** | C00588/C00114 |

| 2 | map00552 | Teichoic acid biosynthesis | Metabolism | 2 | 78.5 (66.2–90.7) | 2.73 × 10−4 | 0.0008 | *** | C00588/C00114 |

| 3 | map02030 | Bacterial chemotaxis | Cellular Processes | 1 | 78.5 (61.1–95.8) | 1.27 × 10−2 | 0.0127 | * | C00124 |

| 4 | map04973 | Carbohydrate digestion and absorption | Organismal Systems | 3 | 52.3 (44.2–60.5) | 2.17 × 10−5 | 0.0003 | *** | C00124/C00095/C00246 |

| 5 | map00670 | One carbon pool by folate | Metabolism | 2 | 36.2 (27.9–44.5) | 1.32 × 10−3 | 0.0028 | ** | C00065/C00114 |

| 6 | map04978 | Mineral absorption | Organismal Systems | 2 | 32.5 (24.6–40.3) | 1.65 × 10−3 | 0.0031 | ** | C00065/C00124 |

| 7 | map00260 | Glycine, serine and threonine metabolism | Metabolism | 3 | 29.4 (23.3–35.5) | 1.25 × 10−4 | 0.0008 | *** | C00065/C00114/C00109 |

| 8 | map00564 | Glycerophospholipid metabolism | Metabolism | 3 | 25.2 (19.6–30.9) | 1.98 × 10−4 | 0.0008 | *** | C00065/C00588/C00114 |

| 9 | map00640 | Propanoate metabolism | Metabolism | 2 | 22.4 (15.9–29.0) | 3.44 × 10−3 | 0.0049 | ** | C00109/C05984 |

| 10 | map00270 | Cysteine and methionine metabolism | Metabolism | 3 | 20.8 (15.6–25.9) | 3.52 × 10−4 | 0.0009 | *** | C00065/C02356/C00109 |

| 11 | map00052 | Galactose metabolism | Metabolism | 2 | 20.5 (14.2–26.7) | 4.11 × 10−3 | 0.0049 | ** | C00124/C00095 |

| 12 | map00650 | Butanoate metabolism | Metabolism | 2 | 20.0 (13.9–26.2) | 4.29 × 10−3 | 0.0049 | ** | C00246/C01089 |

| 13 | map04974 | Protein digestion and absorption | Organismal Systems | 2 | 20.0 (13.9–26.2) | 4.29 × 10−3 | 0.0049 | ** | C00065/C00246 |

| 14 | map02060 | Phosphotransferase system (PTS) | Environmental Information Processing | 2 | 16.5 (10.9–22.1) | 6.25 × 10−3 | 0.0067 | ** | C00124/C00095 |

| 15 | map02010 | ABC transporters | Environmental Information Processing | 3 | 10.2 (6.7–13.8) | 2.76 × 10−3 | 0.0046 | ** | C00065/C00095/C00114 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arbatskiy, M.S.; Eruslanova, K.A.; Balandin, D.E.; Churov, A.V.; Gudkov, D.A.; Tkacheva, O.N. Metabolomic Profiling of Long-Lived Individuals Reveals a Distinct Subgroup with Cardiovascular Disease and Elevated Butyric Acid Derivatives. Metabolites 2025, 15, 803. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15120803

Arbatskiy MS, Eruslanova KA, Balandin DE, Churov AV, Gudkov DA, Tkacheva ON. Metabolomic Profiling of Long-Lived Individuals Reveals a Distinct Subgroup with Cardiovascular Disease and Elevated Butyric Acid Derivatives. Metabolites. 2025; 15(12):803. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15120803

Chicago/Turabian StyleArbatskiy, Mikhail S., Kseniia A. Eruslanova, Dmitriy E. Balandin, Alexey V. Churov, Denis A. Gudkov, and Olga N. Tkacheva. 2025. "Metabolomic Profiling of Long-Lived Individuals Reveals a Distinct Subgroup with Cardiovascular Disease and Elevated Butyric Acid Derivatives" Metabolites 15, no. 12: 803. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15120803

APA StyleArbatskiy, M. S., Eruslanova, K. A., Balandin, D. E., Churov, A. V., Gudkov, D. A., & Tkacheva, O. N. (2025). Metabolomic Profiling of Long-Lived Individuals Reveals a Distinct Subgroup with Cardiovascular Disease and Elevated Butyric Acid Derivatives. Metabolites, 15(12), 803. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15120803