Effects of Physiologically Relevant Species of Organic Mercury on Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Neural Precursor Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

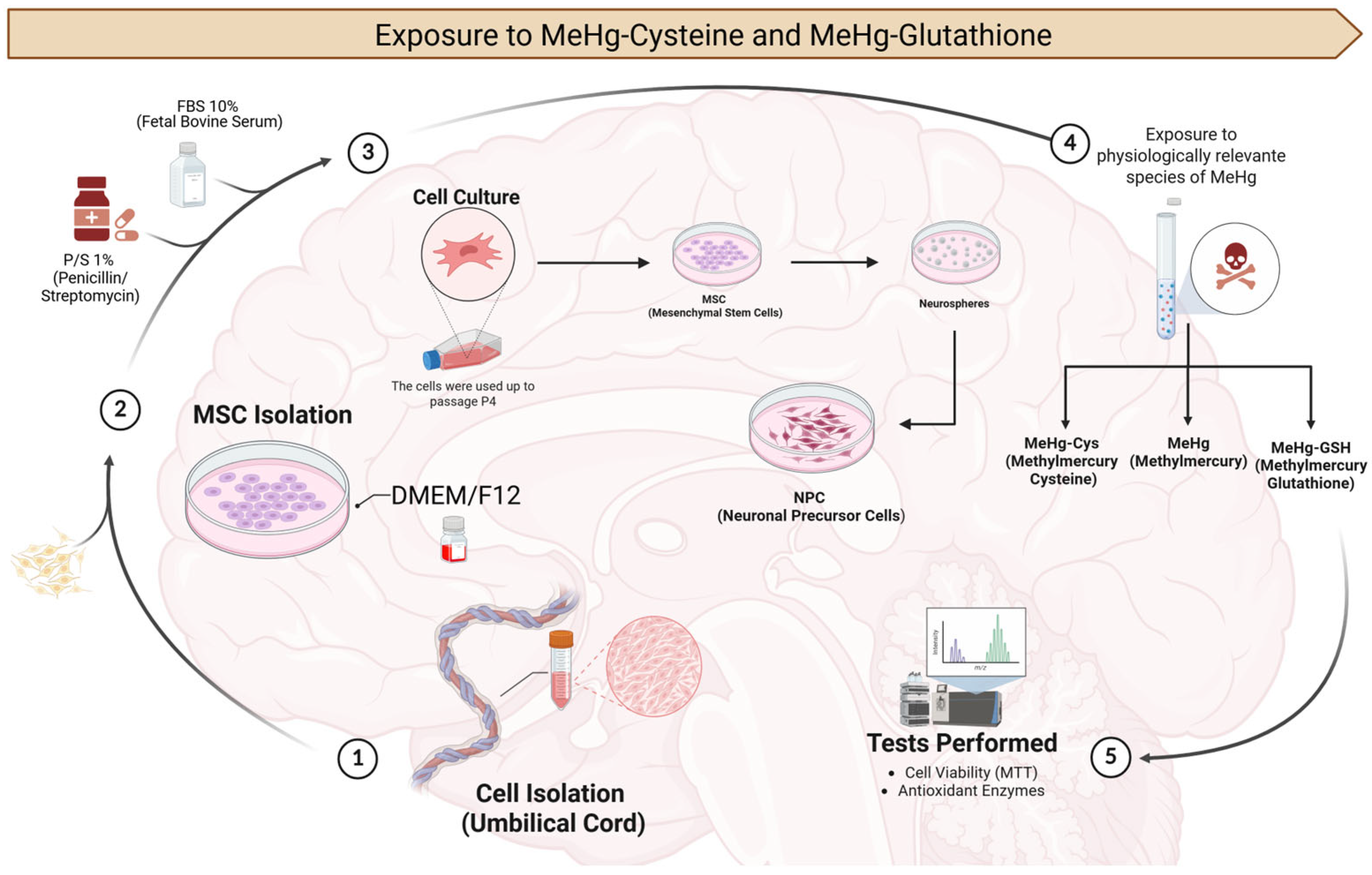

2.1. Experimental Design

2.1.1. MSCs and NPCs

2.1.2. Exposure to the Physiologically Relevant Species of MeHg (MeHg–cysteine and MeHg–glutathione)

2.2. Cell Viability Assay

2.3. Biochemical Analyses

2.3.1. MSCs and NPCs Preparation

2.3.2. SOD Activity

2.3.3. GPx Activity

2.3.4. GST Activity

2.3.5. AChE Activity

2.3.6. GSH Levels

2.3.7. NAG Activity

2.3.8. Total Protein Levels

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. MSCs and NPCs Characterization

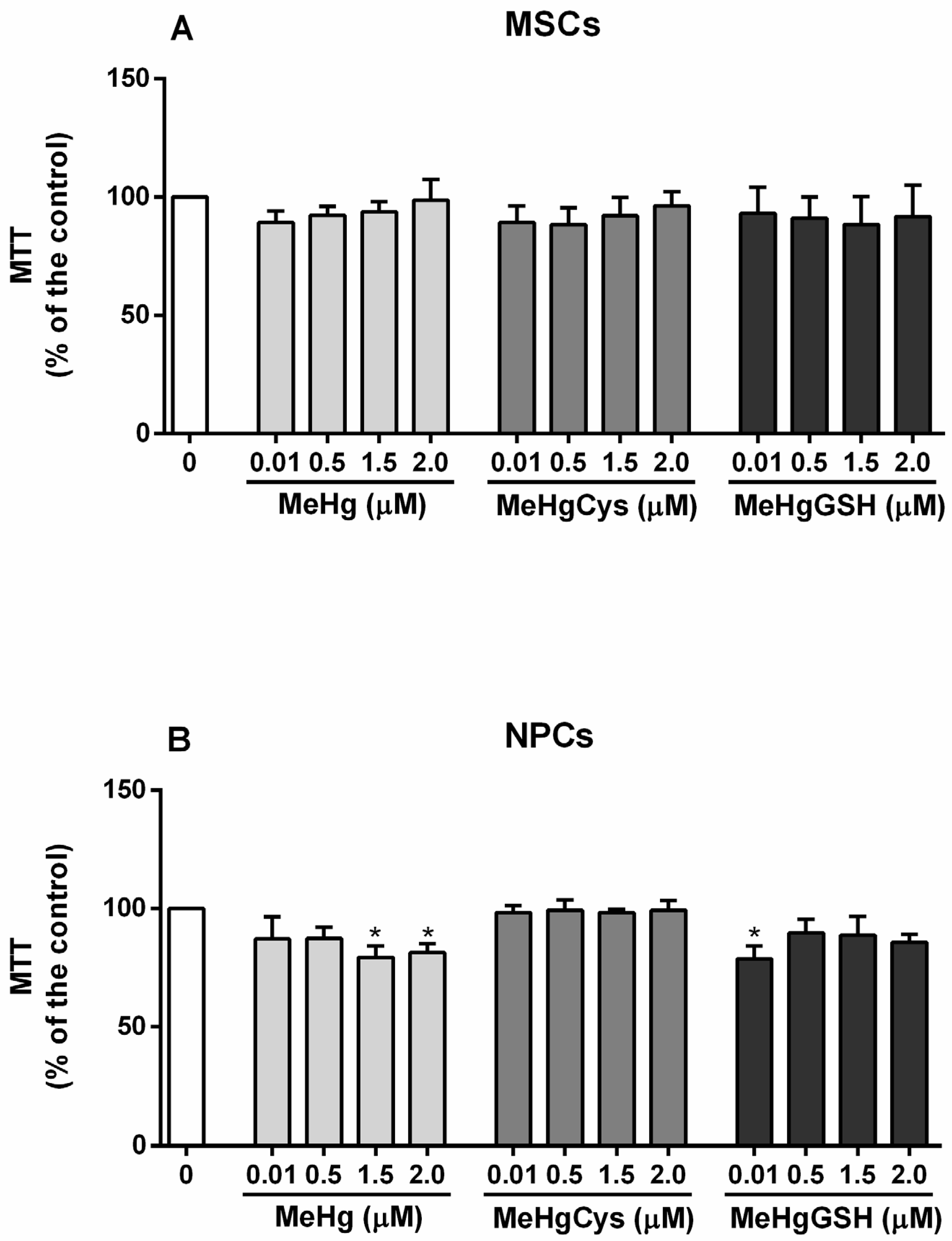

3.2. Cell Viability

3.3. Biochemical Analyses

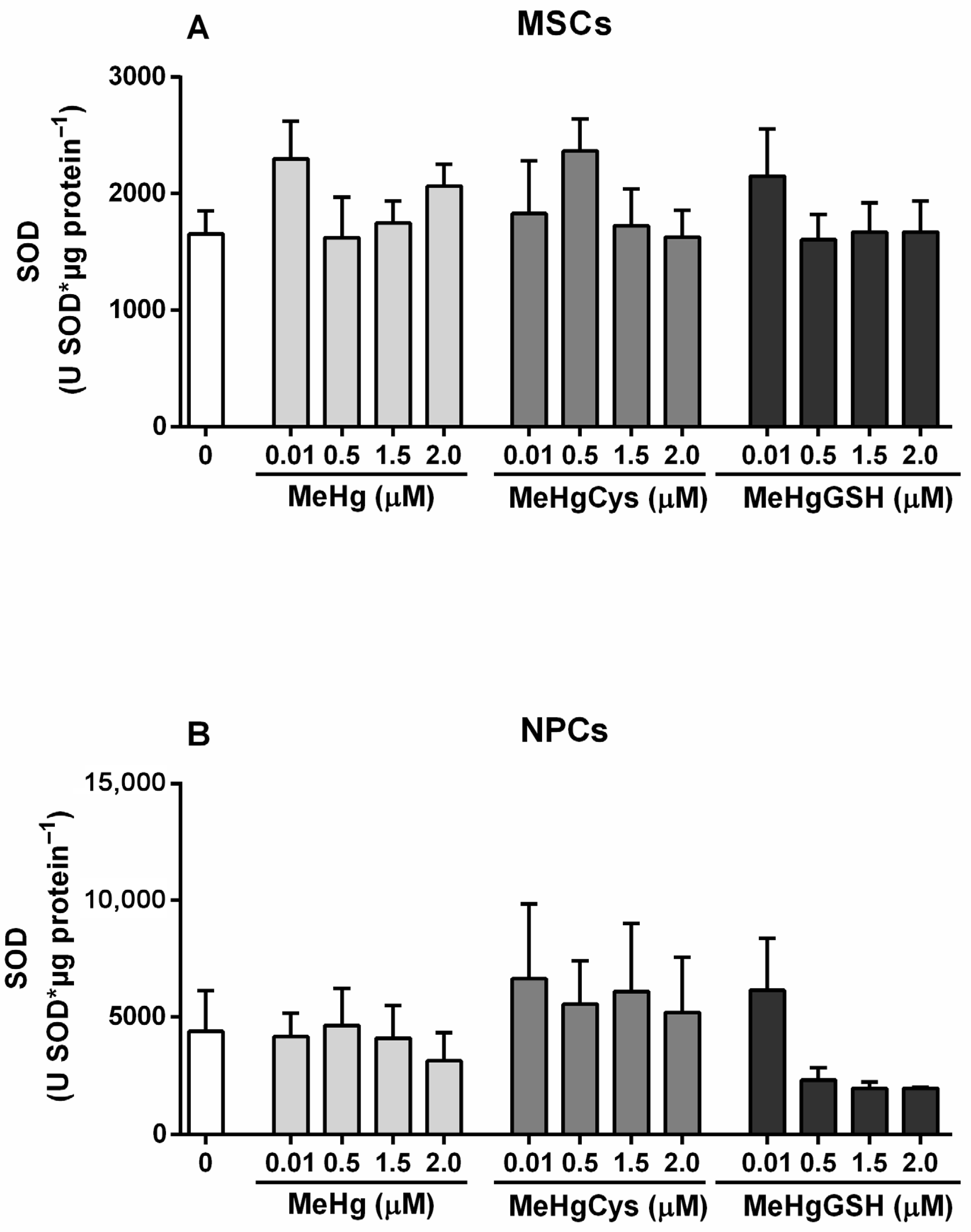

3.3.1. SOD Activity

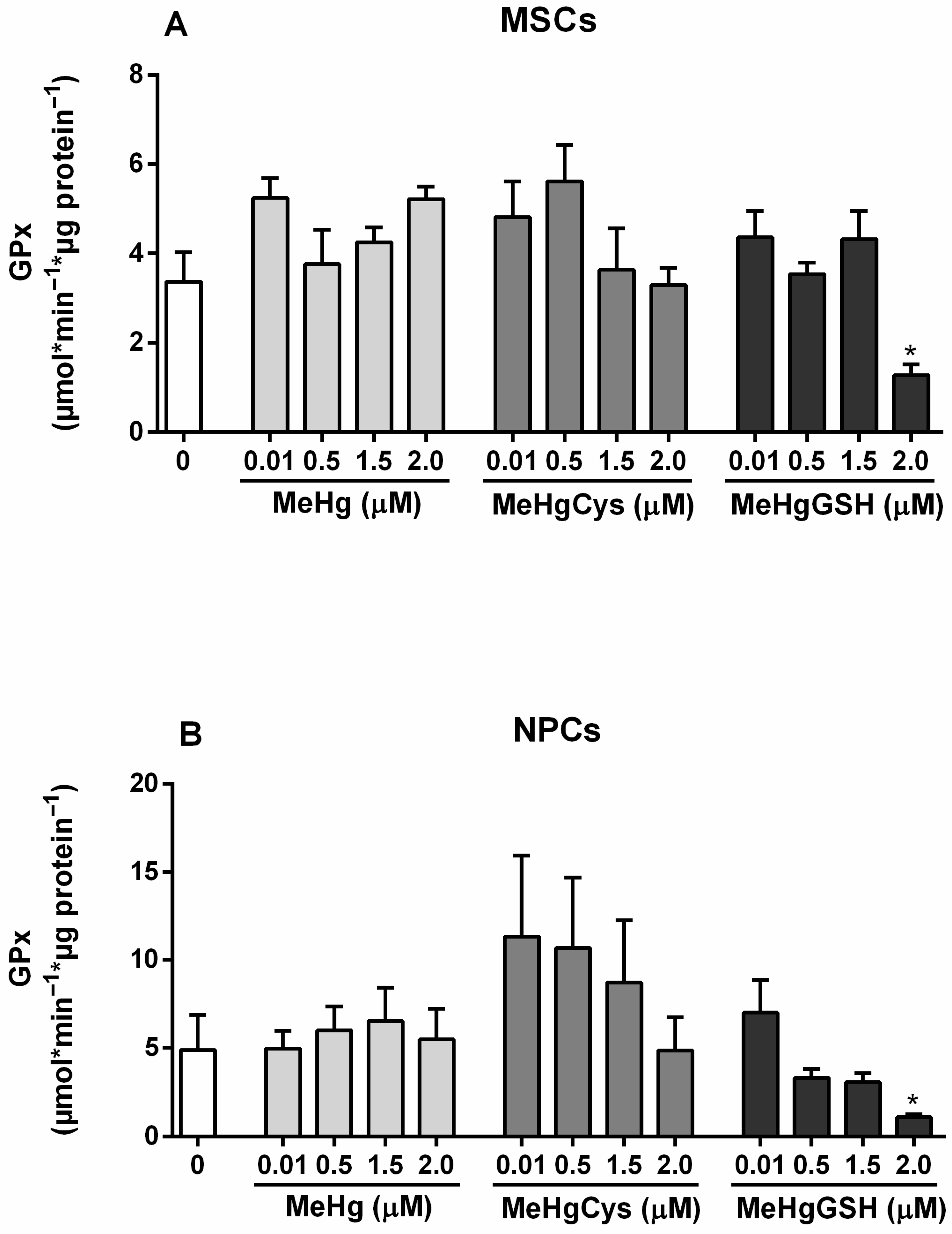

3.3.2. GPx Activity

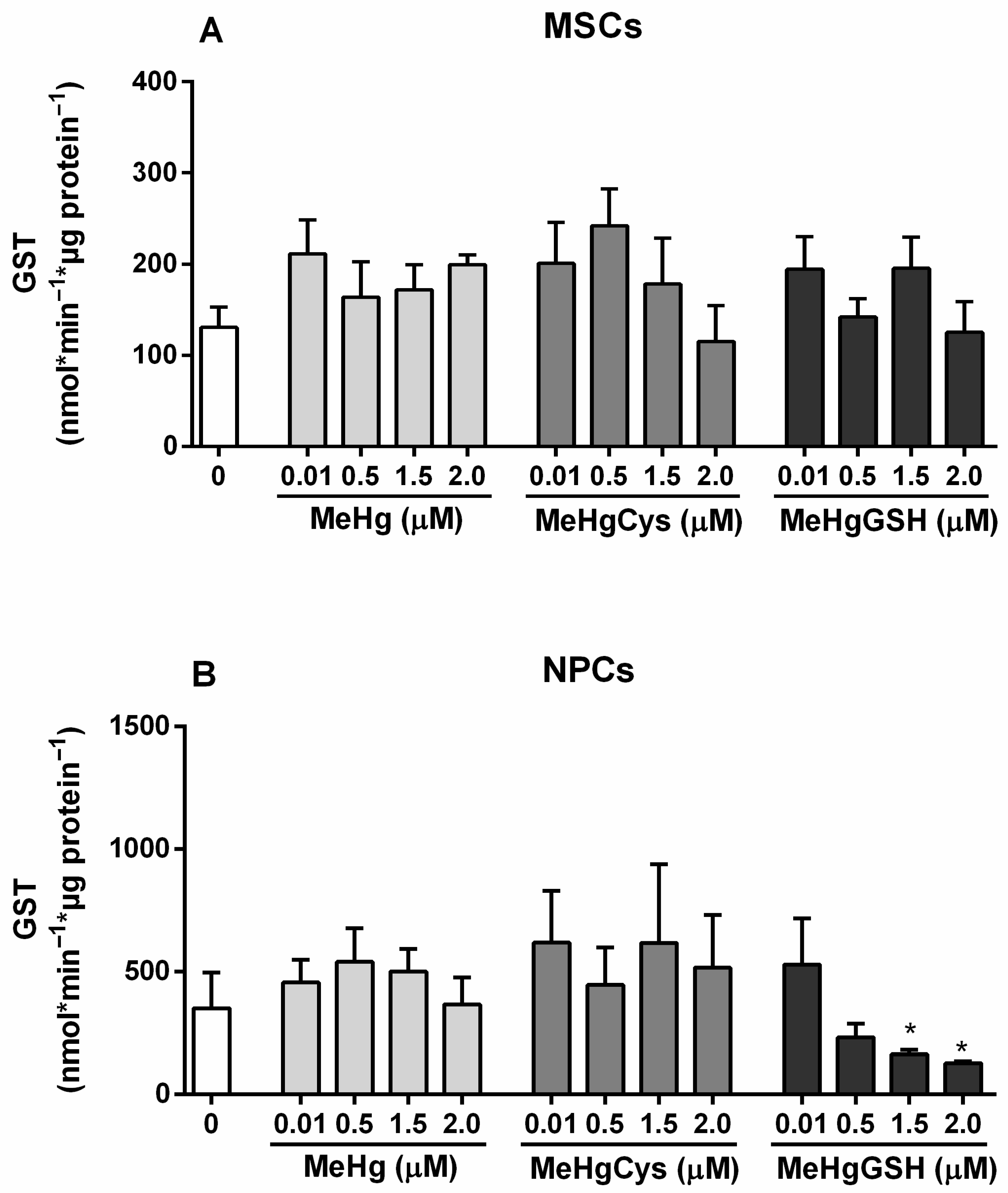

3.3.3. GST Activity

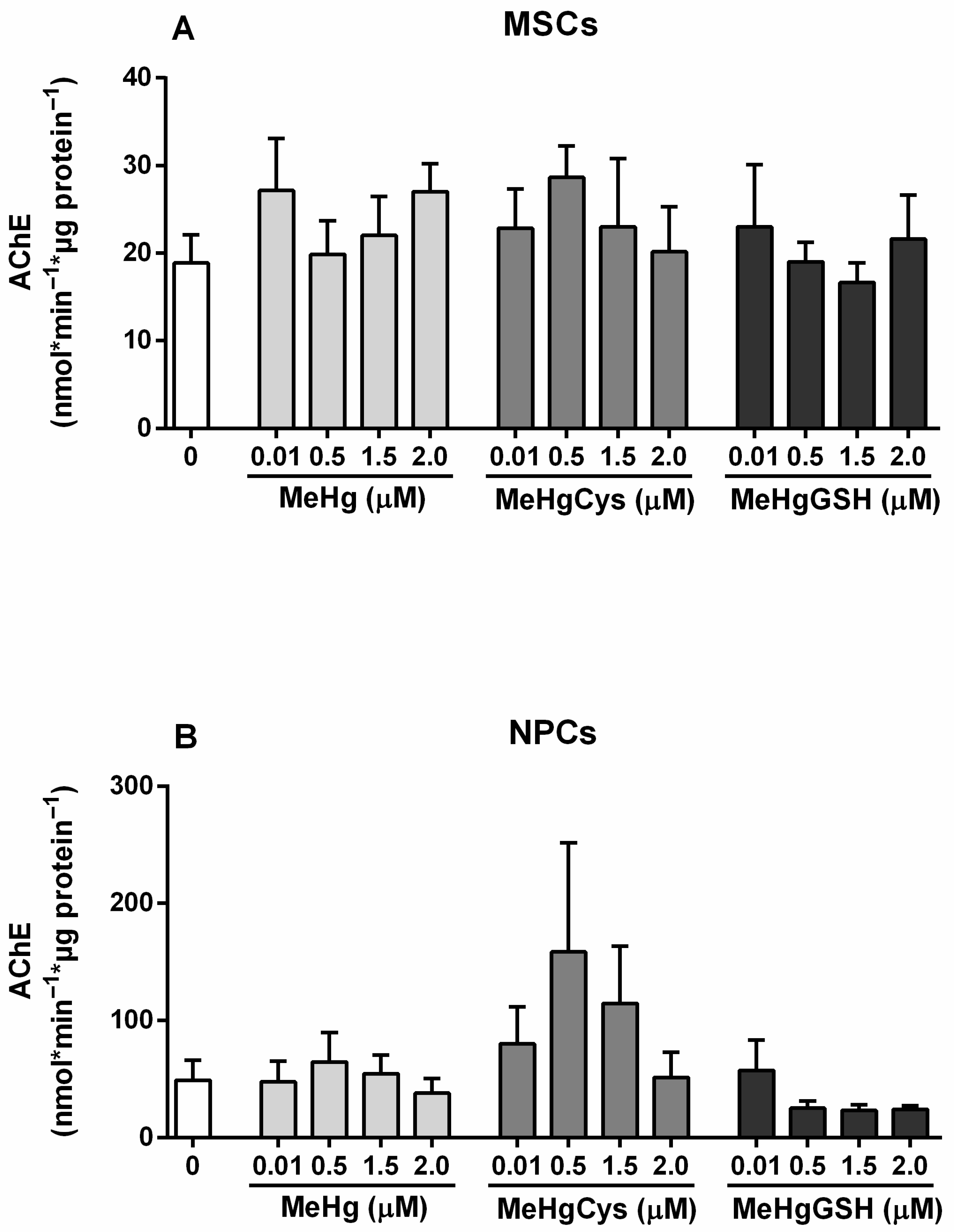

3.3.4. AChE Activity

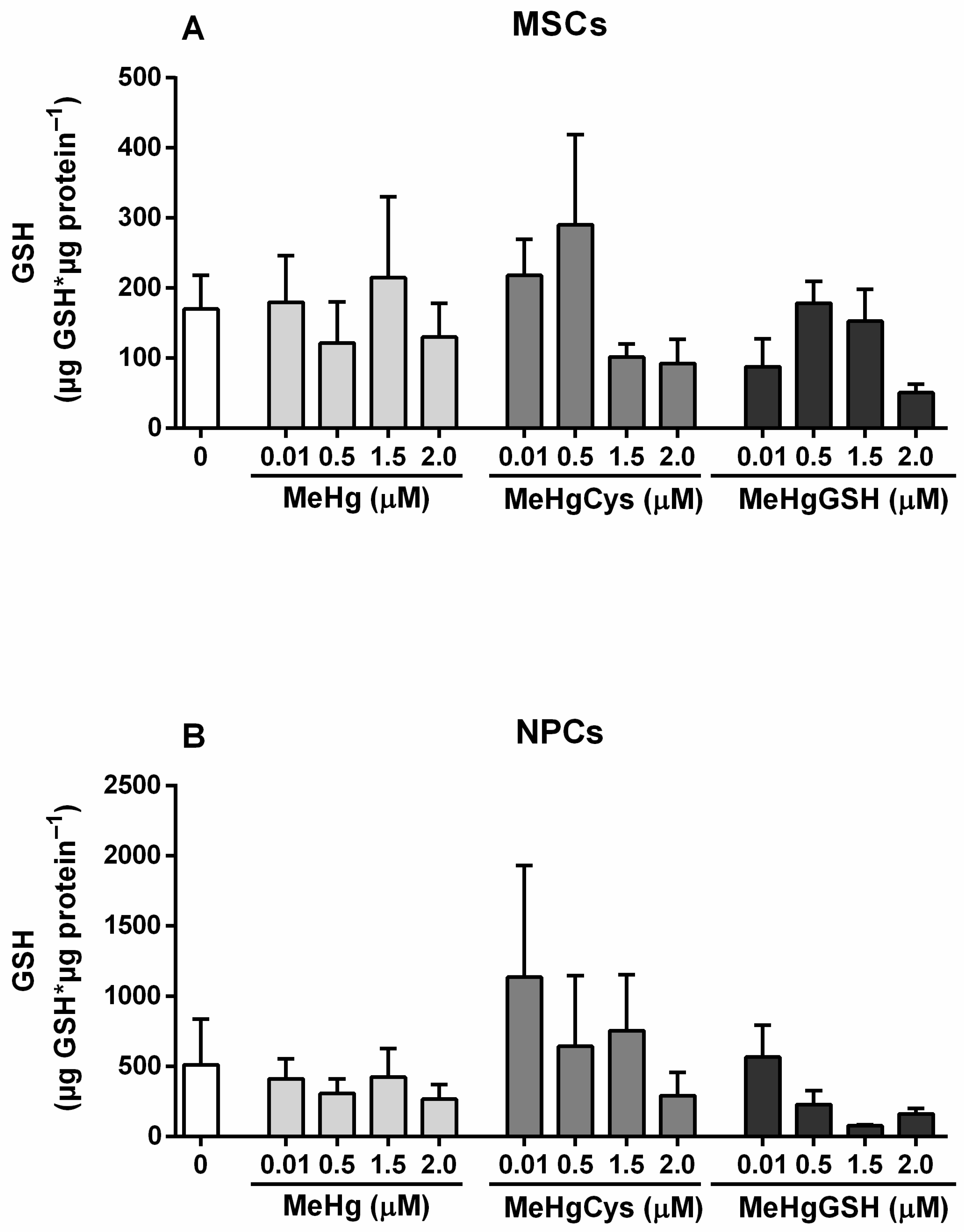

3.3.5. GSH Levels

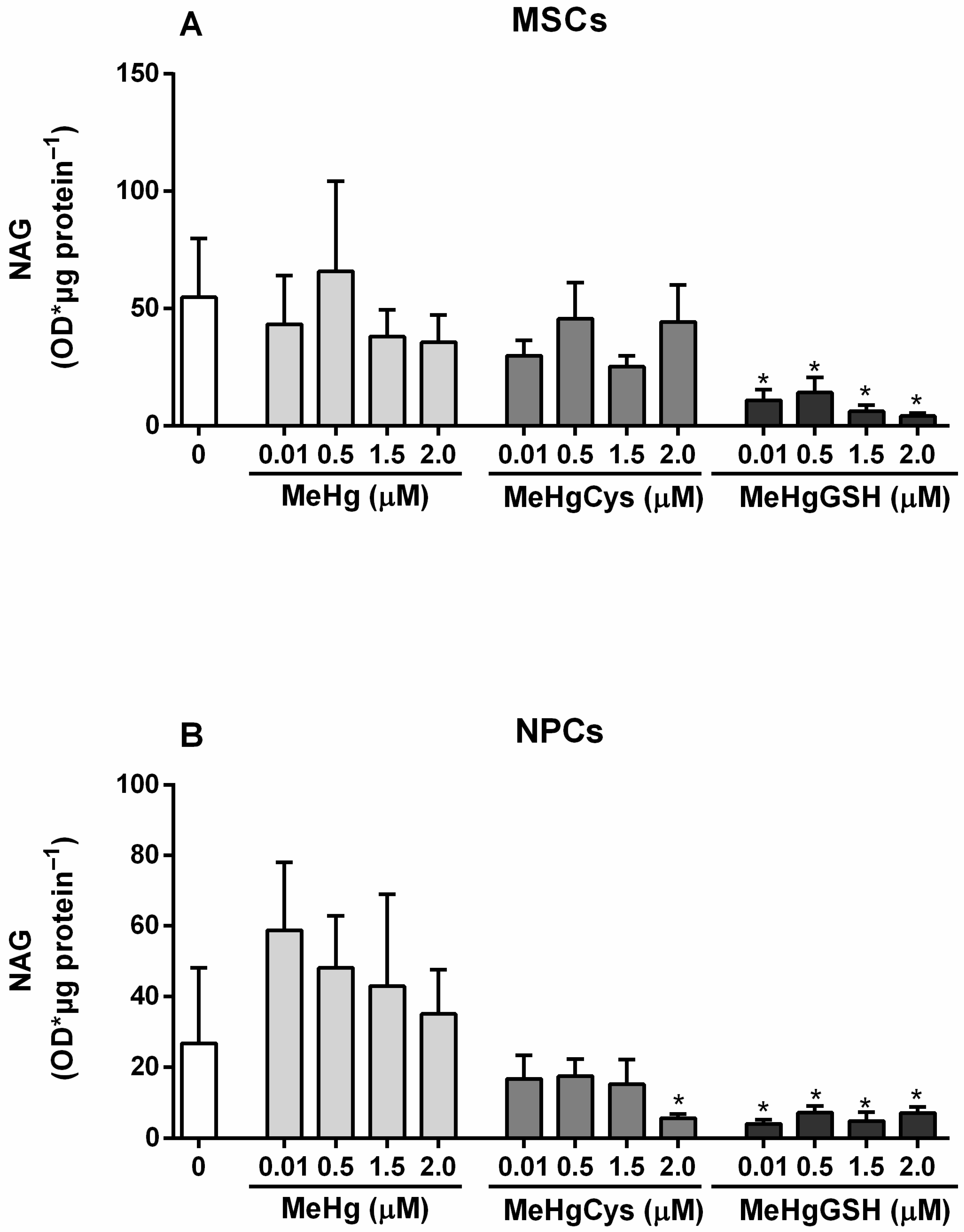

3.3.6. NAG Activity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Health Effects of Exposures to Mercury. 2025. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/mercury/health-effects-exposures-mercury (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Hostert, J.; Galiciolli, M.E.A.; Lima, L.S.; Souza, J.V.; Oliveira, C.S. Mercury toxicity: A brief overview. In Toxicology of Essential and Xenobiotic Metals, 1st ed.; Rocha, J.B.T., Aschner, M., Nogara, P.A., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; Volume 1, pp. 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- Nogara, P.A.; Oliveira, C.S.; Schmitz, G.L.; Piquini, P.C.; Farina, M.; Aschner, M.; Rocha, J.B.T. Methylmercury’s chemistry: From the environment to the mammalian brain. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2019, 1863, 129284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, C.S.; Nogara, P.A.; Ardisson-Araújo, D.M.P.; Aschner, M.; Rocha, J.B.T.; Dórea, J.G. Neurodevelopmental effects of mercury. In Linking Environmental Exposure to Neurodevelopmental Disorders; Aschner, M., Costa, L., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 2, pp. 27–86. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, C.S.; Piccoli, B.C.; Aschner, M.; Rocha, J.B.T. Chemical speciation of selenium and mercury as determinant of their neurotoxicity. In Neurotoxicity of Metals; Aschner, M., Costa, L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 18, pp. 53–83. [Google Scholar]

- Bridges, C.C.; Zalups, R.K. Mechanisms involved in the transport of mercuric ions in target tissues. Arch. Toxicol. 2017, 91, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridges, C.C.; Zalups, R.K. Transport of inorganic mercury and methylmercury in target tissues. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health B Crit. Rev. 2010, 13, 385–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganapathy, S.; Farrell, E.R.; Vaghela, S.; Joshee, L.; Ford, E.G., 4th; Uchakina, O.; McKallip, R.J.; Barkin, J.L.; Bridges, C.C. Transport and toxicity of methylmercury-cysteine in cultured BeWo cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 23, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silbereis, J.C.; Pochareddy, S.; Zhu, Y.; Li, M.; Sestan, N. The cellular and molecular landscapes of the developing human central nervous system. Neuron 2016, 89, 248–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landgrave-Gómez, J.; Mercado-Gómez, O.; Guevara-Guzmán, R. Epigenetic mechanisms in neurological and neurodegenerative diseases. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 58. [Google Scholar]

- Okar, S.V.; Fagiani, F.; Absinta, M.; Reich, D.S. Imaging of brain barrier inflammation and brain fluid drainage in human neurological diseases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2024, 81, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Wang, B.; Wang, R.; Gong, S.; Chen, G.; Xu, W. The shift in the balance between osteoblastogenesis and adipogenesis of mesenchymal stem cells mediated by glucocorticoid receptor. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2019, 10, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.N.; Wu, J.F. TGF-β/SMAD signaling regulation of mesenchymal stem cells in adipocyte commitment. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 11, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, Y.S.; Xu, Q. Neuronal differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells using exosomes derived from differentiating neuronal cells. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0135111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, S.; Hamblin, M.R.; Abrahamse, H. Differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells to neuroglia: In the context of cell signalling. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2019, 15, 814–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnaik, R.; Padhy, R.N. Human umbilical cord blood-derived neural stem cell line as a screening model for toxicity. Neurotox. Res. 2017, 31, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Li, Y.; Wu, K.; Hao, S.; Cai, Q.; Zhou, Z.J.; Yang, H.F. Effects of environmental chemicals on the proliferation and differentiation of neural stem cells. Environ. Toxicol. 2019, 34, 1285–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza-Rodrigues, R.D.; Puty, B.; Bonfim, L.; Nogueira, L.S.; Nascimento, P.C.; Bittencourt, L.O.; Couto, R.S.D.; Barboza, C.A.G.; de Oliveira, E.H.C.; Marques, M.M.; et al. Methylmercury-induced cytotoxicity and oxidative biochemistry impairment in dental pulp stem cells: The first toxicological findings. PeerJ 2021, 9, e11114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Ruiz, M.; de Alba Gonzalez, M.; Cañas Portilla, A.I.; Coronel, R.; Liste, I.; González-Caballero, M.C. Effects of nanomolar methylmercury on developing human neural stem cells and zebrafish Embryo. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2024, 188, 114684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Jiang, H.; Syversen, T.; Rocha, J.B.T.; Farina, M.; Aschner, M. The methylmercury-L-cysteine conjugate is a substrate for the L-type large neutral amino acid transporter. J. Neurochem. 2008, 107, 1083–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, L.T.; Santos, D.B.; Naime, A.A.; Leal, R.B.; Dórea, J.G.; Barbosa, F., Jr.; Aschner, M.; Rocha, J.B.T.; Farina, M. Comparative study on methyl- and ethylmercury-induced toxicity in C6 glioma cells and the potential role of LAT-1 in mediating mercurial-thiol complexes uptake. Neurotoxicology 2013, 38, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stricker, P.E.F.; de Souza Dobuchak, D.; Irioda, A.C.; Mogharbel, B.F.; Franco, C.R.C.; de Souza Almeida Leite, J.R.; de Araújo, A.R.; Borges, F.A.; Herculano, R.D.; de Oliveira Graeff, C.F.; et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells seeded on the natural membrane to neurospheres for cholinergic-like neurons. Membranes 2021, 11, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobuchak, D.S.; Stricker, P.E.F.; de Oliveira, N.B.; Mogharbel, B.F.; da Rosa, N.N.; Dziedzic, D.S.M.; Irioda, A.C.; Carvalho, K.A.T. The neural multilineage differentiation capacity of human neural precursors from the umbilical cord-ready to bench for clinical trials. Membranes 2022, 12, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, N.B.; Irioda, A.C.; Stricker, P.E.F.; Mogharbel, B.F.; da Rosa, N.N.; Dziedzic, D.S.M.; Carvalho, K.A.T. Natural membrane differentiates human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells to neurospheres by mechanotransduction related to YAP and AMOT proteins. Membranes 2021, 11, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa, N.N.; Appel, J.M.; Irioda, A.C.; Mogharbel, B.F.; de Oliveira, N.B.; Perussolo, M.C.; Stricker, P.E.F.; Rosa-Fernandes, L.; Marinho, C.R.F.; Carvalho, K.A.T. Three-dimensional bioprinting of an in vitro lung model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perussolo, M.C.; Mogharbel, B.F.; Saçaki, C.S.; Rosa, N.N.D.; Irioda, A.C.; Oliveira, N.B.; Appel, J.M.; Lührs, L.; Meira, L.F.; Guarita-Souza, L.C.; et al. Cellular therapy in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis as an adjuvant treatment to translate for multiple sclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irioda, A.C.; Cassilha, R.; Zocche, L.; Francisco, J.C.; Cunha, R.C.; Ferreira, P.E.; Guarita-Souza, L.C.; Ferreira, R.J.; Mogharbel, B.F.; Garikipati, V.N.; et al. Human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells cryopreservation and thawing decrease α4-integrin expression. Stem Cells Int. 2016, 2016, 2562718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bridges, C.C.; Zalups, R.K. System b0,+ and the transport of thiol-s-conjugates of methylmercury. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006, 319, 948–956. [Google Scholar]

- Mosmann, T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: Application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods 1983, 65, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Yuan, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Gao, X. Mechanism of pyrogallol autoxidation and determination of superoxide dismutase enzyme activity. Bioelectroch Bioener 1998, 45, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paglia, D.E.; Valentine, W.N. Studies on the quantitative and qualitative characterization of erythrocyte glutathione peroxidase. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1967, 70, 158–169. [Google Scholar]

- Keen, J.H.; Habig, W.H.; Jakoby, W.B. Mechanism for the several activities of the glutathione S-transferases. J. Biol. Chem. 1976, 251, 6183–6188. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ellman, G.L.; Courtney, K.D.; Andres, V., Jr.; Feather-Stone, R.M. A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1961, 7, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedlak, J.; Lindsay, R.H. Estimation of total, protein-bound, and nonprotein sulfhydryl groups in tissue with Ellman’s reagent. Anal. Biochem. 1968, 25, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, P.J. Sponge implants as models. Methods Enzymol. 1988, 162, 327–334. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farina, M.; Aschner, M.; Rocha, J.B.T. Oxidative stress in MeHg-induced neurotoxicity. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2011, 256, 405–417. [Google Scholar]

- Valle-Prieto, A.; Conget, P.A. Human mesenchymal stem cells efficiently manage oxidative stress. Stem Cells Dev. 2010, 19, 1885–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Gómez-Sintes, R.; Boya, P. Lysosomal membrane permeabilization and cell death. Traffic 2018, 19, 918–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, H.R.; Tuan, R.S. Secreted trophic factors of mesenchymal stem cells support neurovascular and musculoskeletal therapies. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2016, 7, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, N.; Scholtemeijer, M.; Shah, K. Mesenchymal stem cell immunomodulation: Mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 41, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zachar, L.; Bačenková, D.; Rosocha, J. Activation, homing, and role of the mesenchymal stem cells in the inflammatory environment. J. Inflamm. Res. 2016, 9, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, D.M.; Shah, J.; Srivastava, A.S. Therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells in regenerative medicine. Stem Cells Int. 2013, 2013, 496218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boda, E.; Rigamonti, A.E.; Bollati, V. Understanding the effects of air pollution on neurogenesis and gliogenesis in the growing and adult brain. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2020, 50, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzola, P.; Melzer, T.; Pavesi, E.; Gil-Mohapel, J.; Brocardo, P.S. Exploring the role of neuroplasticity in development, aging, and neurodegeneration. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, T.; Gonçalves, F.M.; Gonçalves, C.L.; Dos Santos, A.A.; Rocha, J.B.T.; Farina, M.; Skalny, A.; Tsatsakis, A.; Bowman, A.B.; Aschner, M. Post-translational modifications in MeHg-induced neurotoxicity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2019, 1865, 2068–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, M.; Li, X.; Rocha, J.B.T.; Farina, M.; Aschner, M. Glia and methylmercury neurotoxicity. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A 2012, 75, 1091–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hostert, J.; Kirsten, N.; Lührs, L.; Irioda, A.C.; Guiloski, I.C.; de Carvalho, K.A.T.; Oliveira, C.S. Effects of Physiologically Relevant Species of Organic Mercury on Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Neural Precursor Cells. Metabolites 2025, 15, 794. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15120794

Hostert J, Kirsten N, Lührs L, Irioda AC, Guiloski IC, de Carvalho KAT, Oliveira CS. Effects of Physiologically Relevant Species of Organic Mercury on Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Neural Precursor Cells. Metabolites. 2025; 15(12):794. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15120794

Chicago/Turabian StyleHostert, Juliane, Nathalia Kirsten, Larissa Lührs, Ana Carolina Irioda, Izonete Cristina Guiloski, Katherine Athayde Teixeira de Carvalho, and Cláudia Sirlene Oliveira. 2025. "Effects of Physiologically Relevant Species of Organic Mercury on Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Neural Precursor Cells" Metabolites 15, no. 12: 794. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15120794

APA StyleHostert, J., Kirsten, N., Lührs, L., Irioda, A. C., Guiloski, I. C., de Carvalho, K. A. T., & Oliveira, C. S. (2025). Effects of Physiologically Relevant Species of Organic Mercury on Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Neural Precursor Cells. Metabolites, 15(12), 794. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo15120794